User login

Sarcoidosis: An FP’s primer on an enigmatic disease

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disease of unclear etiology that primarily affects the lungs. It can occur at any age but usually develops before the age of 50 years, with an initial peak incidence at 20 to 29 years and a second peak incidence after 50 years of age, especially among women in Scandinavia and Japan.1 Sarcoidosis affects men and women of all racial and ethnic groups throughout the world, but differences based on race, sex, and geography are noted.1

The highest rates are reported in northern European and African-American individuals, particularly in women.1,2 The adjusted annual incidence of sarcoidosis among African Americans is approximately 3 times that among White Americans3 and is more likely to be chronic and fatal in African Americans.3 The disease can be familial with a possible recessive inheritance mode with incomplete penetrance.4 Risk of sarcoidosis in monozygotic twins appears to be 80 times greater than that in the general population, which supports genetic factors accounting for two-thirds of disease susceptibility.5

Likely factors in the development of sarcoidosis

The exact cause of sarcoidosis is unknown, but we have insights into its pathogenesis and potential triggers.1,6-9 Genes involved are being identified: class I and II human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules are most consistently associated with risk of sarcoidosis. Environmental exposures can activate the innate immune system and precondition a susceptible individual to react to potential causative antigens in a highly polarized, antigen-specific Th1 immune response. The epithelioid granulomatous response involves local proinflammatory cytokine production and enhanced T-cell immunity at sites of inflammation.10 Granulomas generally form to confine pathogens, restrict inflammation, and protect surrounding tissue.11-13

ACCESS (A Case Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis) identified several environmental exposures such as chemicals used in the agriculture industry, mold or mildew, and musty odors at work.14 Tobacco use was not associated with sarcoidosis.14 Recent studies have shown positive associations with service in the US Navy,15 metal working,16 firefighting,17 the handling of building supplies,18 and onsite exposure while assisting in rescue efforts at the World Trade Center disaster.19 Other data support the likelihood that specific environmental exposures associated with microbe-rich environments modestly increase the risk of sarcoidosis.14 Mycobacterial and propionibacterial DNA and RNA are potentially associated with sarcoidosis.20

Clinical manifestations are nonspecific

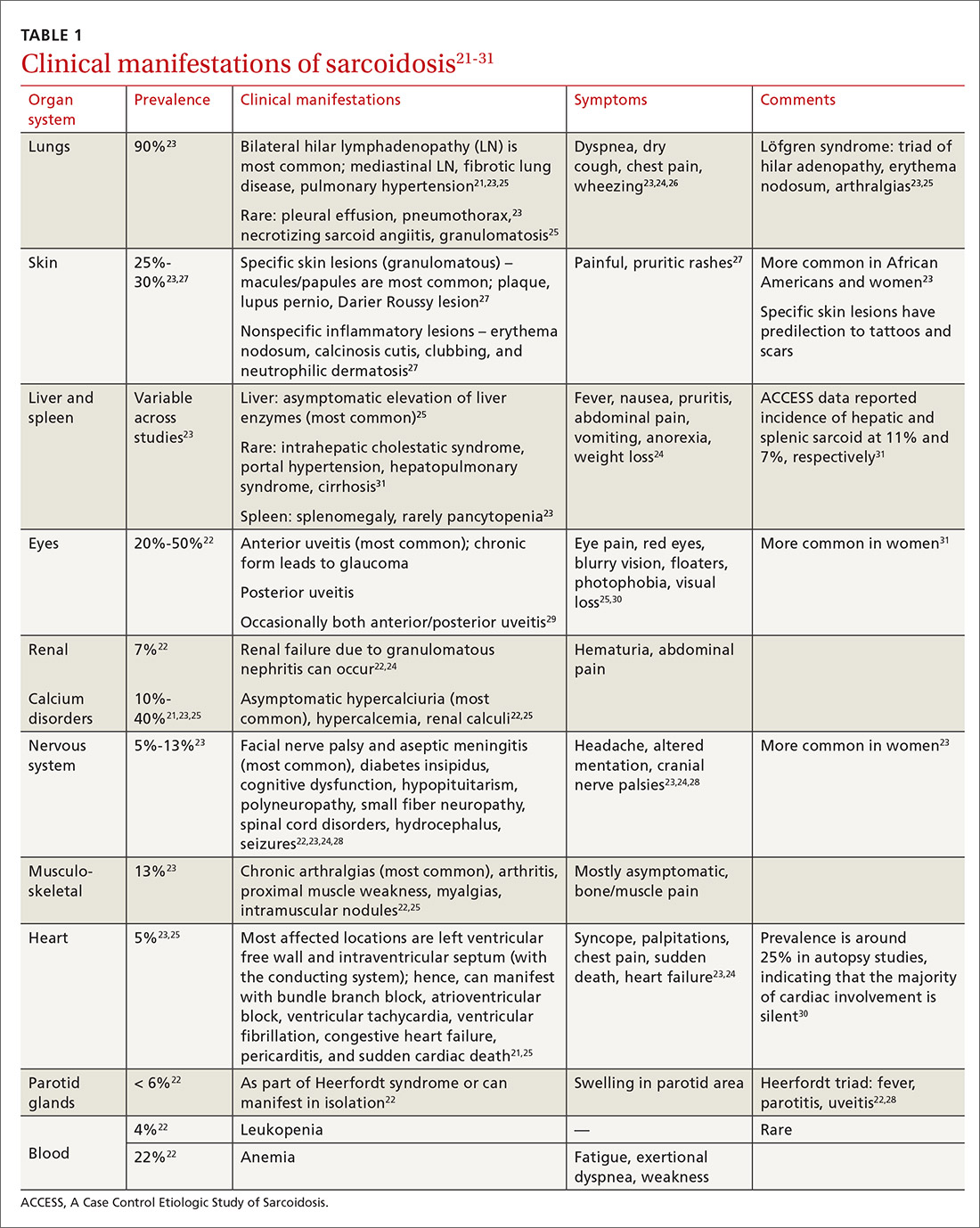

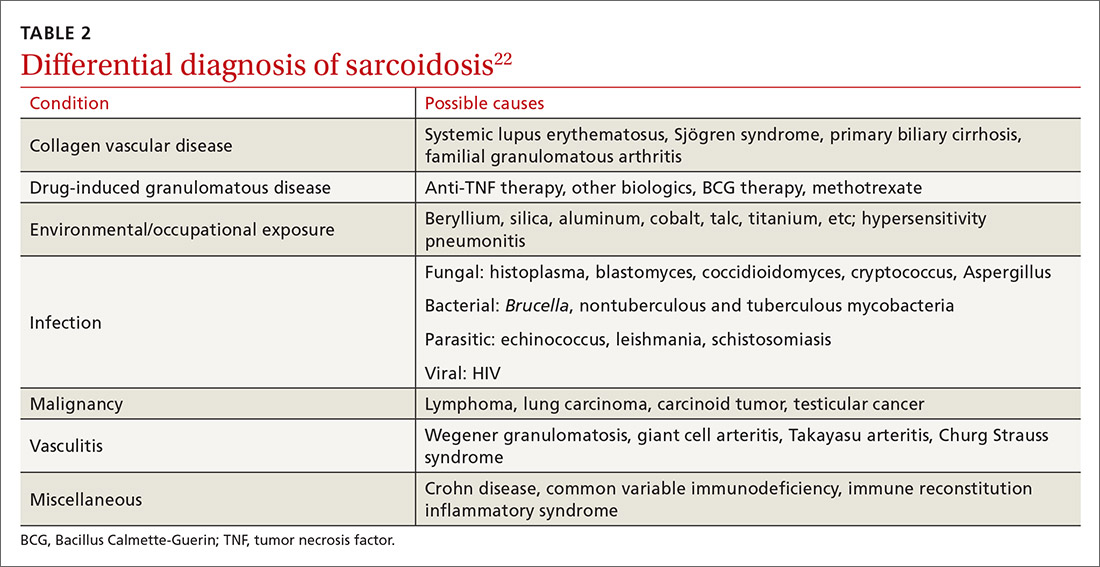

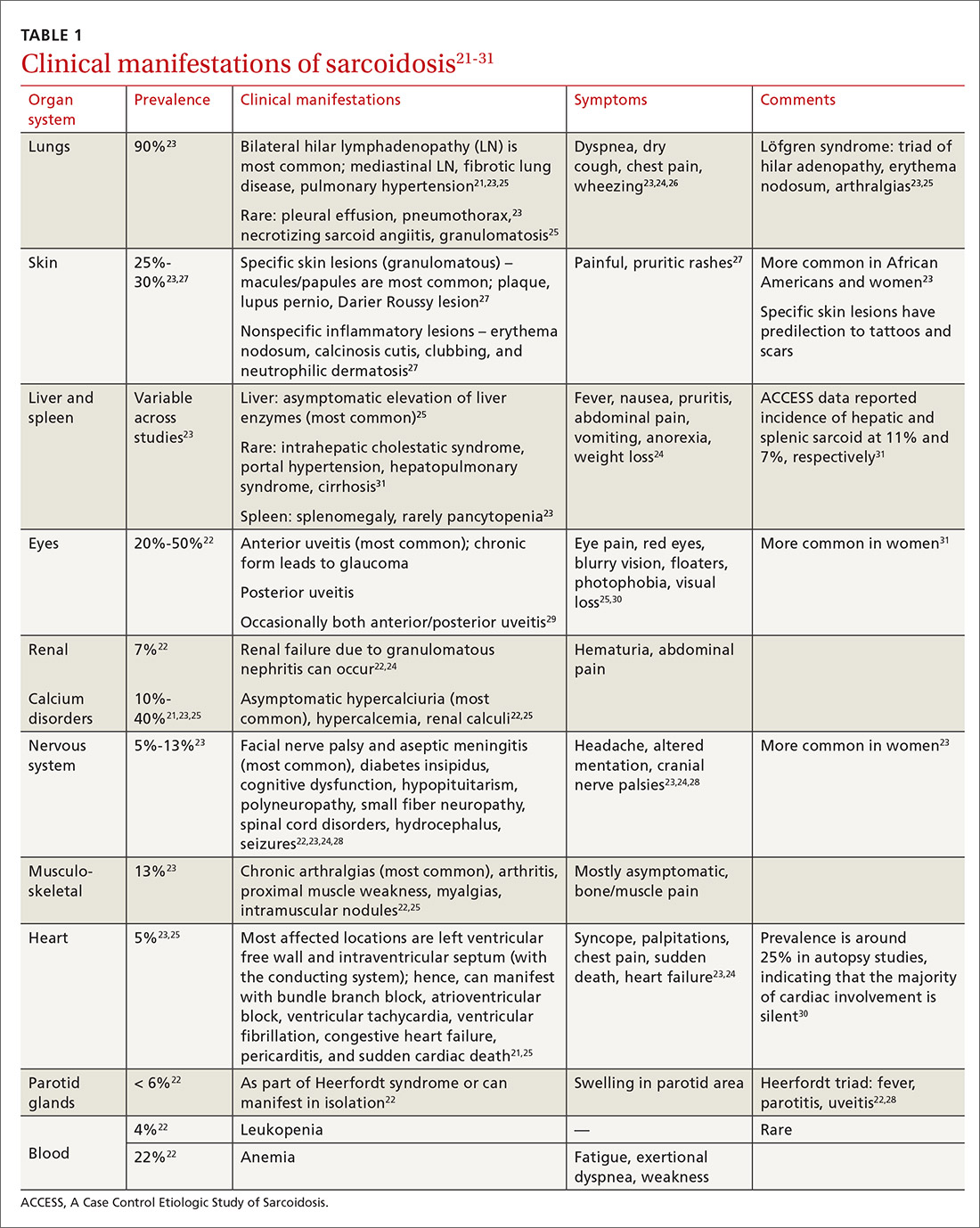

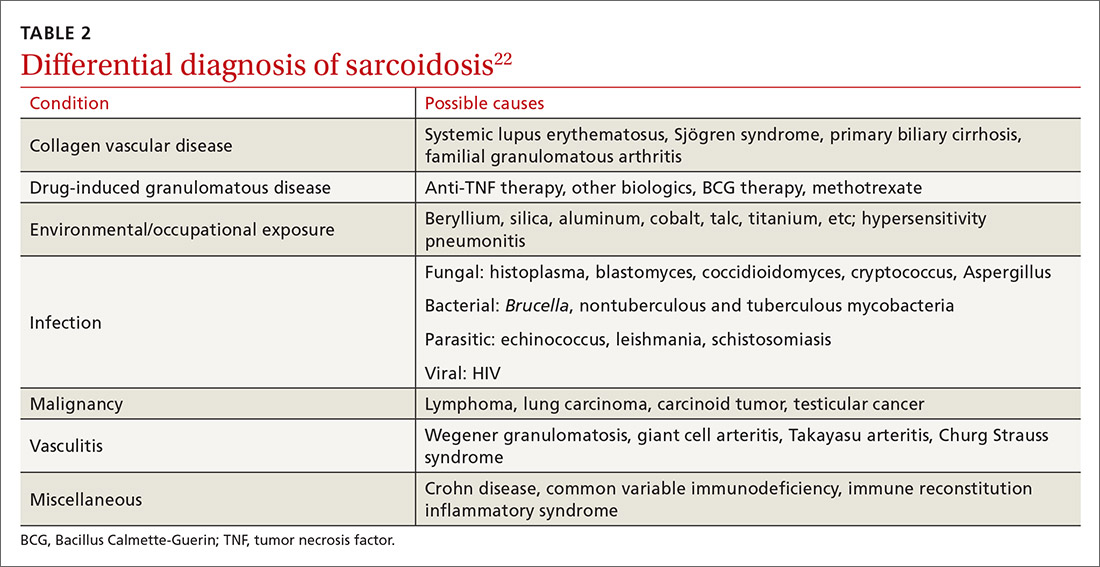

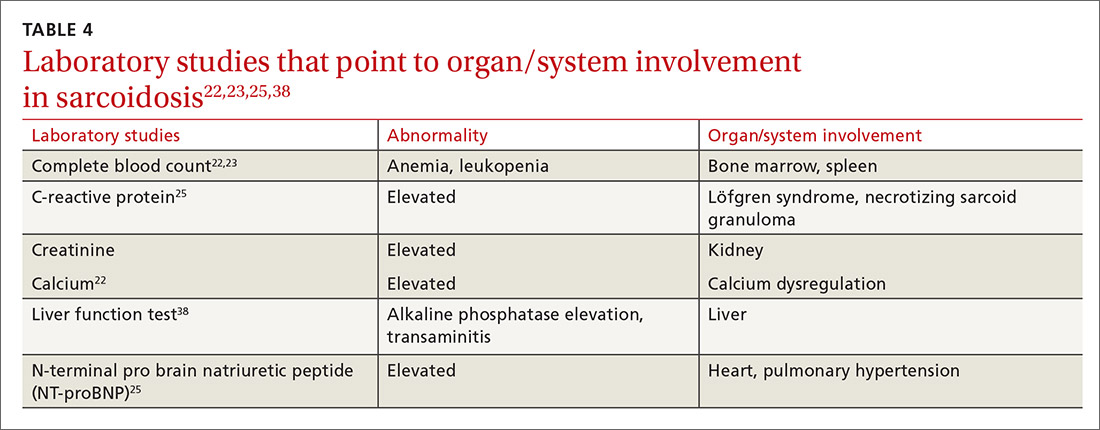

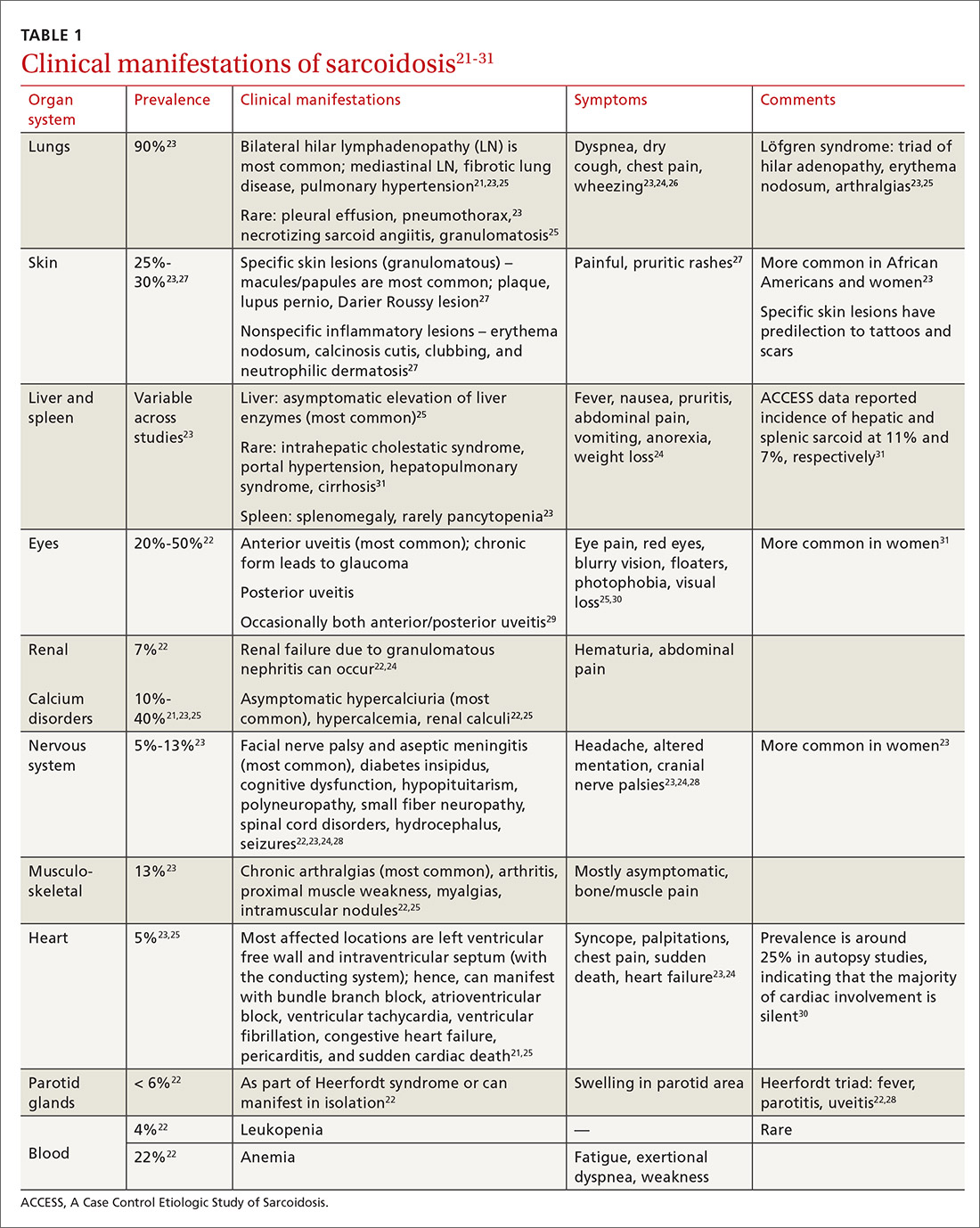

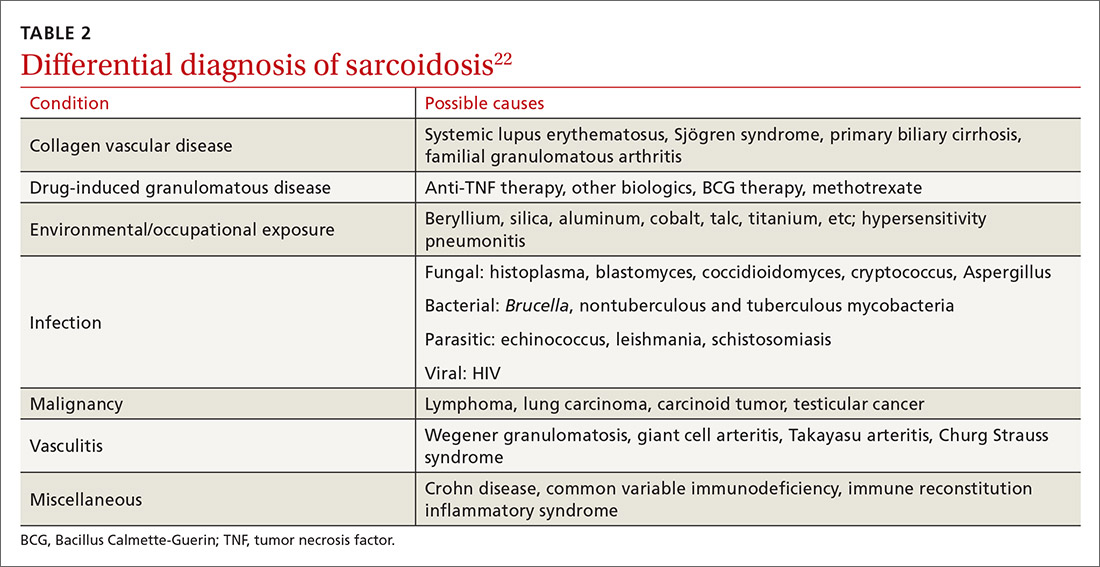

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis can be difficult and delayed due to diverse organ involvement and nonspecific presentations. TABLE 121-31 shows the diverse manifestations in a patient with suspected sarcoidosis. Around 50% of the patients are asymptomatic.23,24 Sarcoidosis is a diagnosis of exclusion, starting with a detailed history to rule out infections, occupational or environmental exposures, malignancies, and other possible disorders (TABLE 2).22

Diagnostic work-up

Radiologic studies

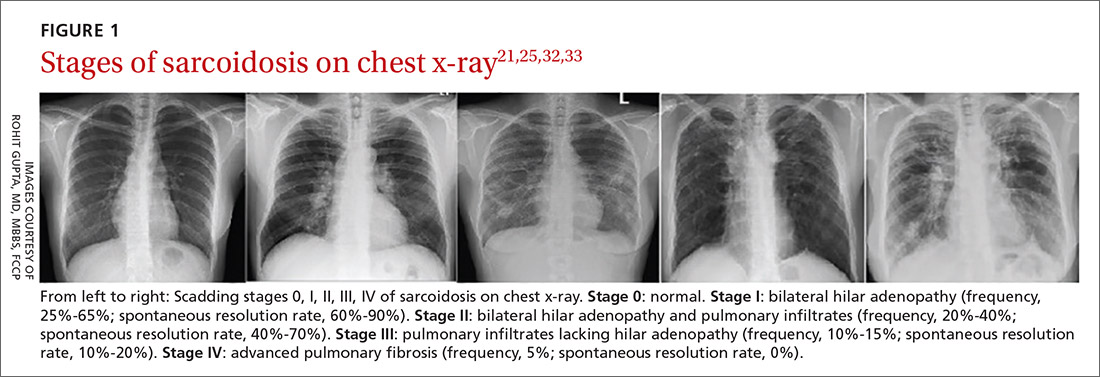

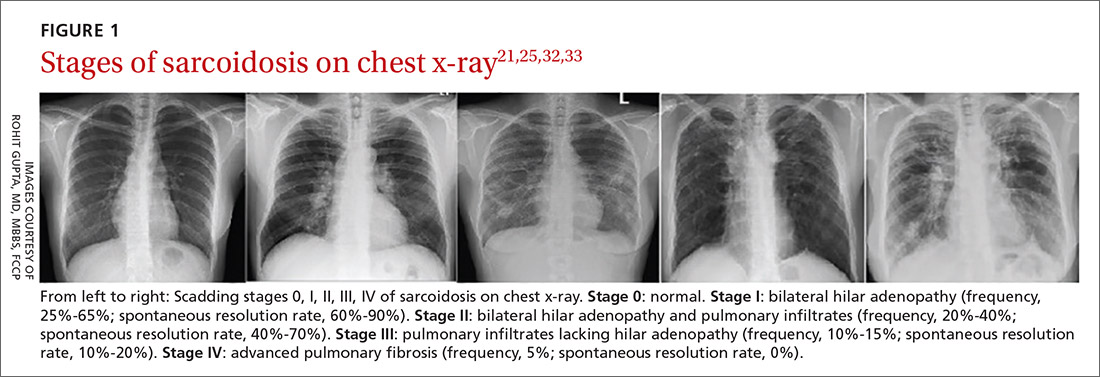

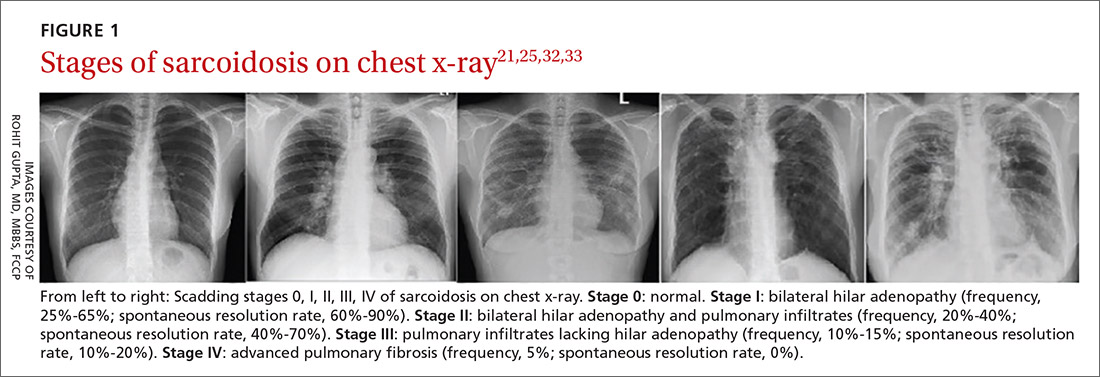

Chest x-ray (CXR) provides diagnostic and prognostic information in the evaluation of sarcoidosis using the Scadding classification system (FIGURE 1).21,25,32,33 Interobserver variability, especially between stages II and III and III and IV is the major limitation of this system.32 At presentation, radiographs are abnormal in approximately 90% of patients.34 Lymphadenopathy is the most common radiographic abnormality, occurring in more than two-thirds of cases, and pulmonary opacities (nodules and reticulation) with a middle to upper lobe predilection are present in 20% to 50% of patients.1,31,35 The nodules vary in size and can coalesce and cause alveolar collapse, thus producing consolidation.36 Linear opacities radiating laterally from the hilum into the middle and upper zones are characteristic in fibrotic disease.

Continue to: High-resoluton computed tomography

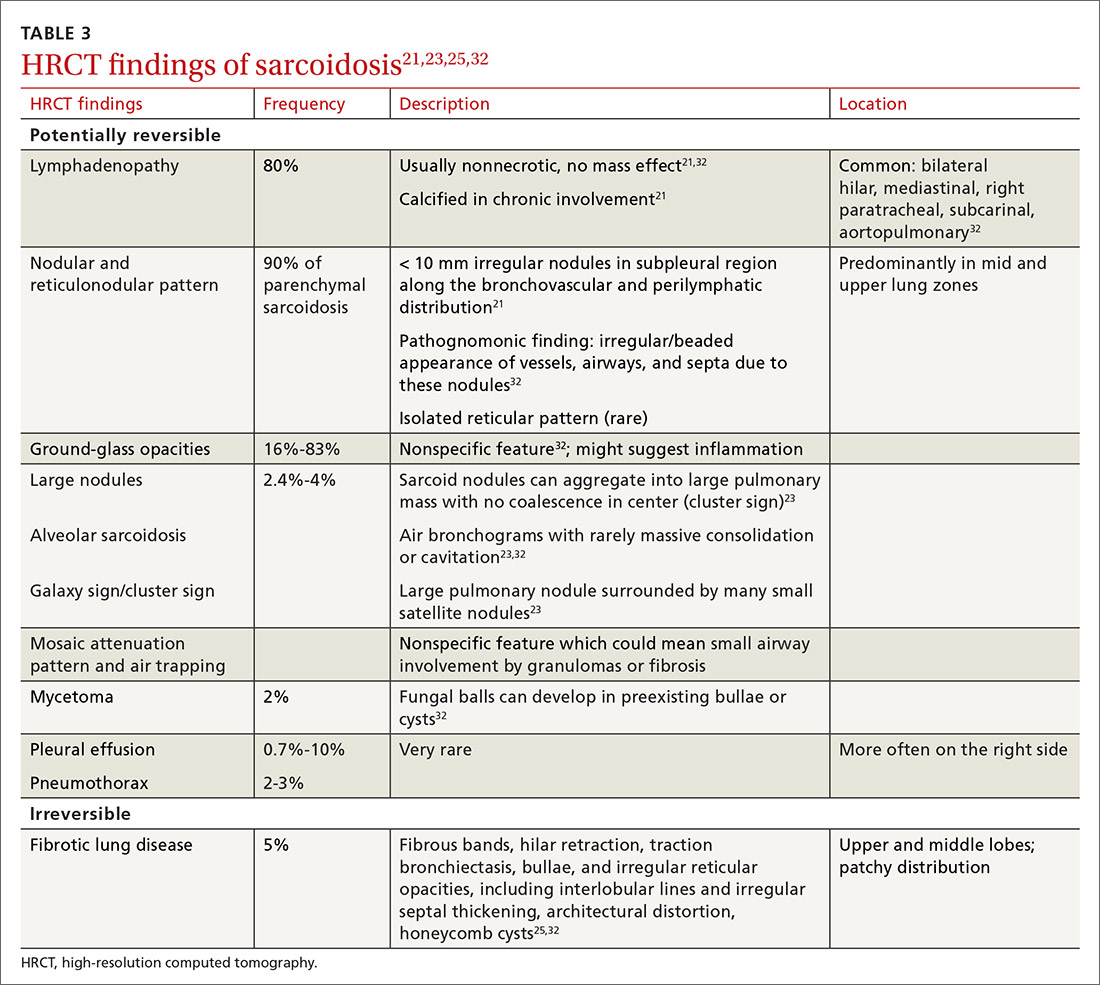

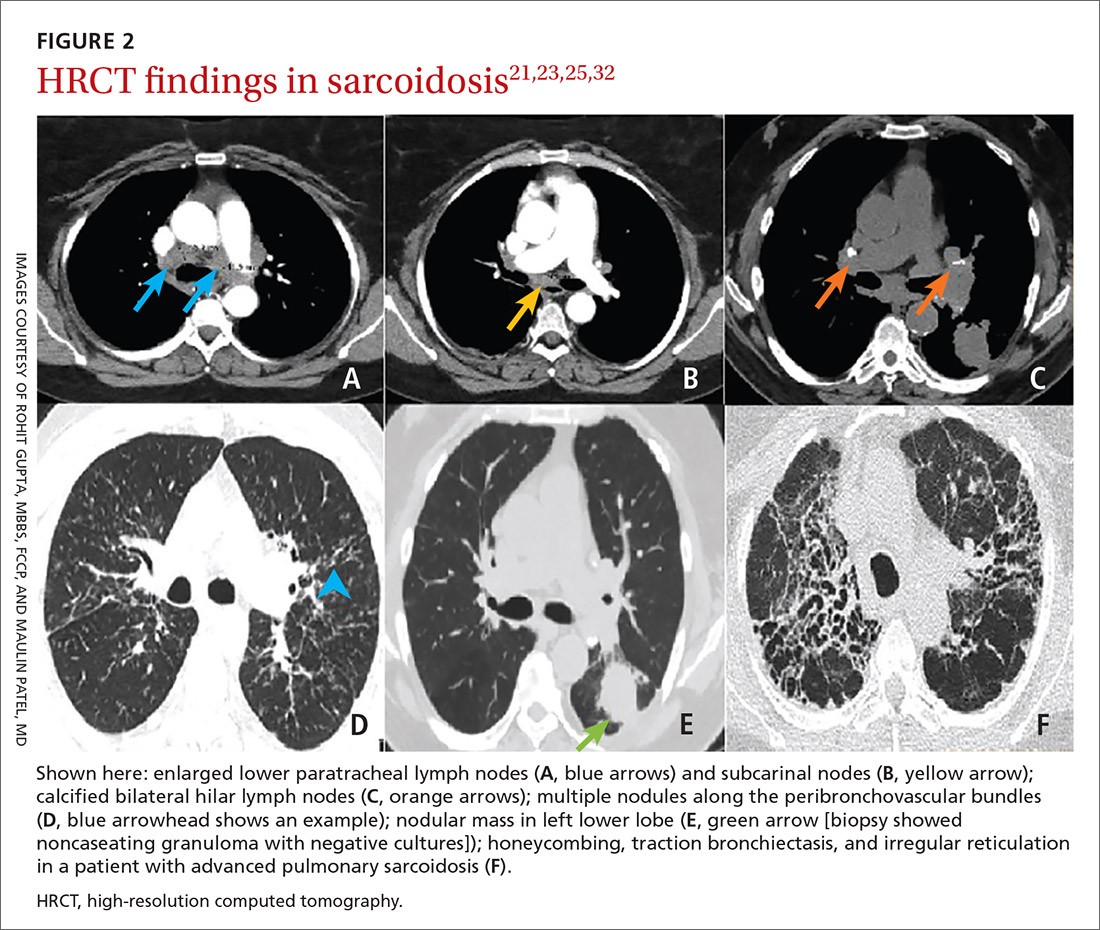

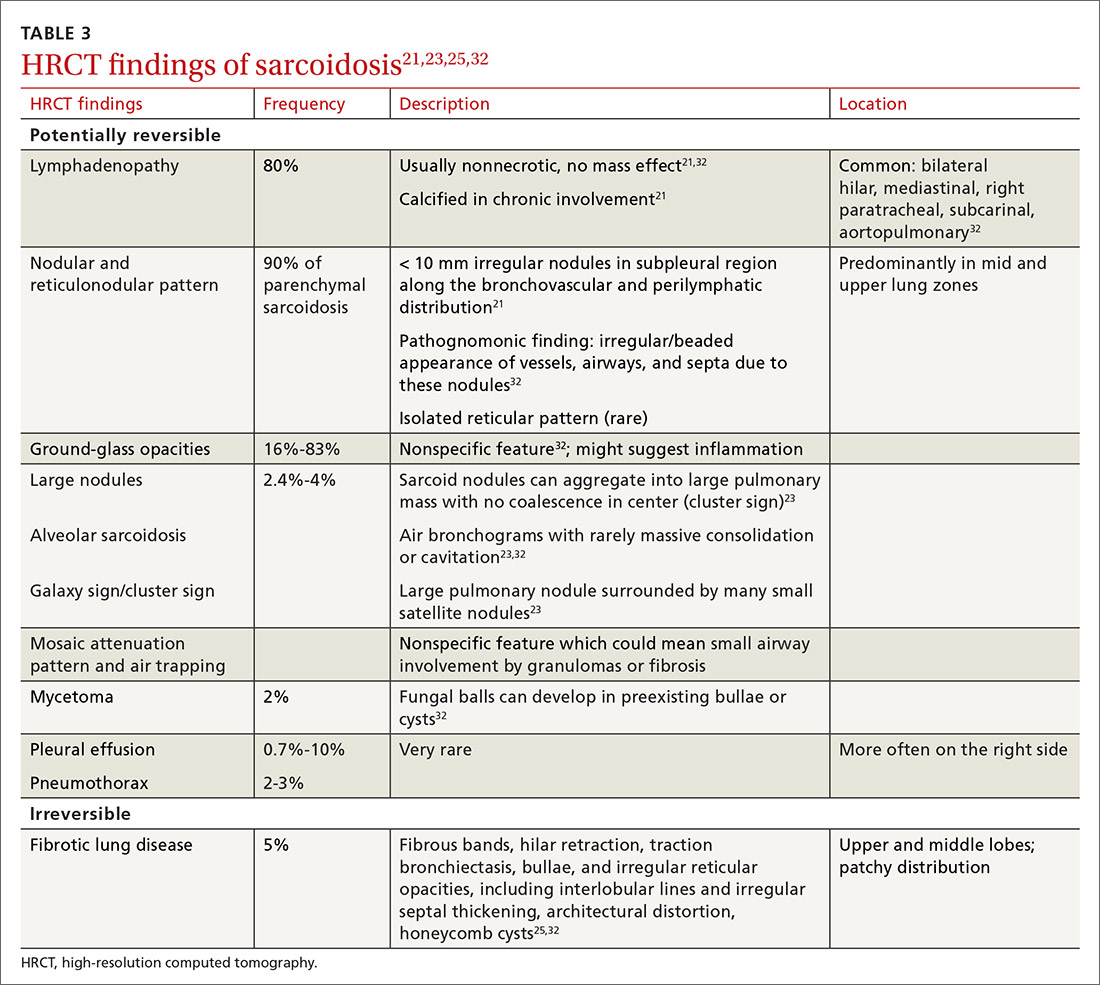

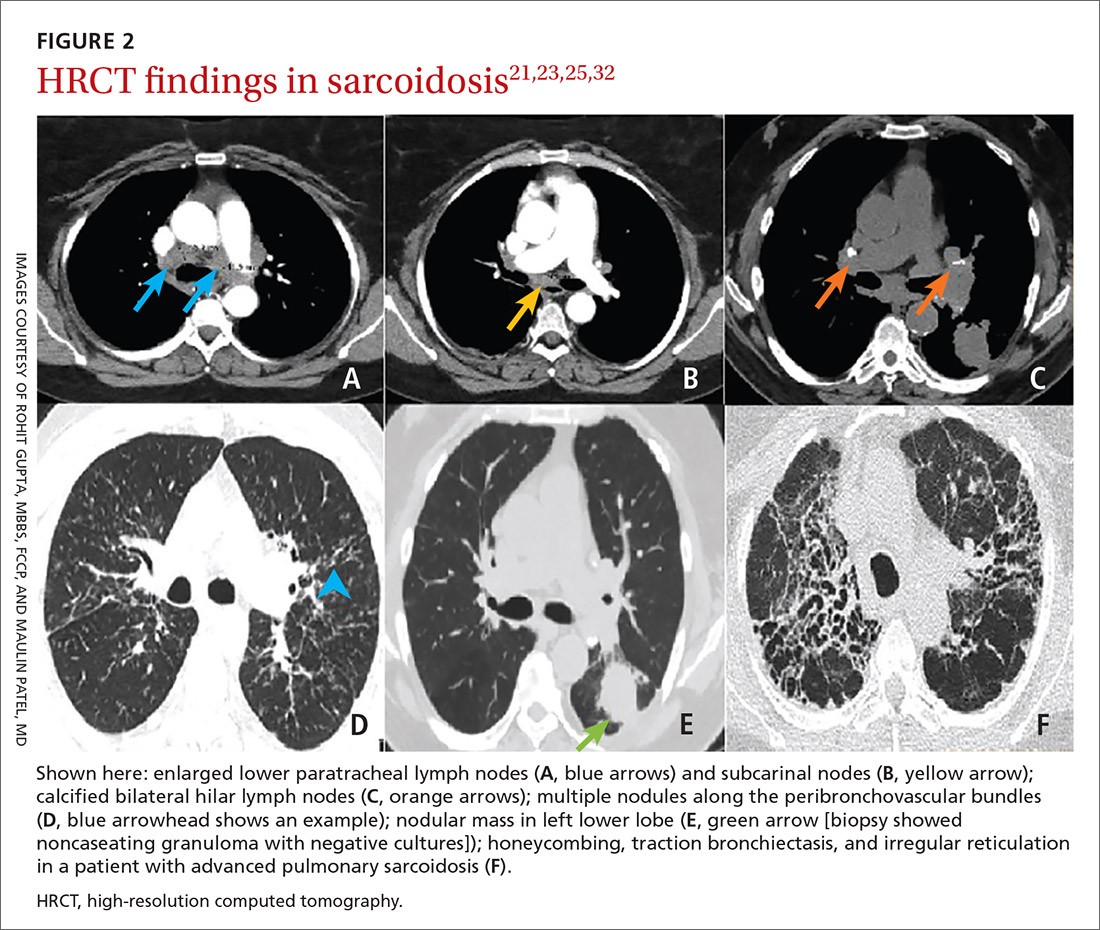

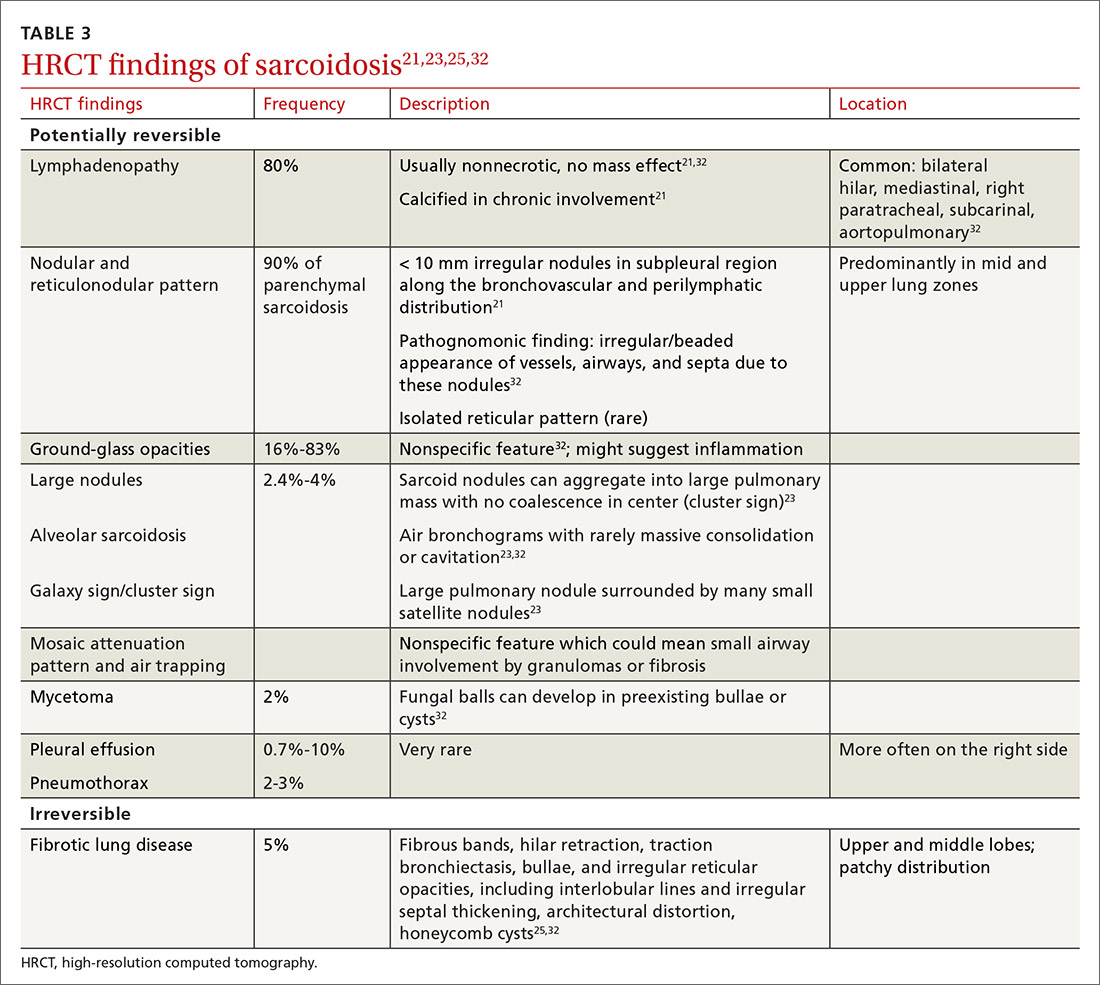

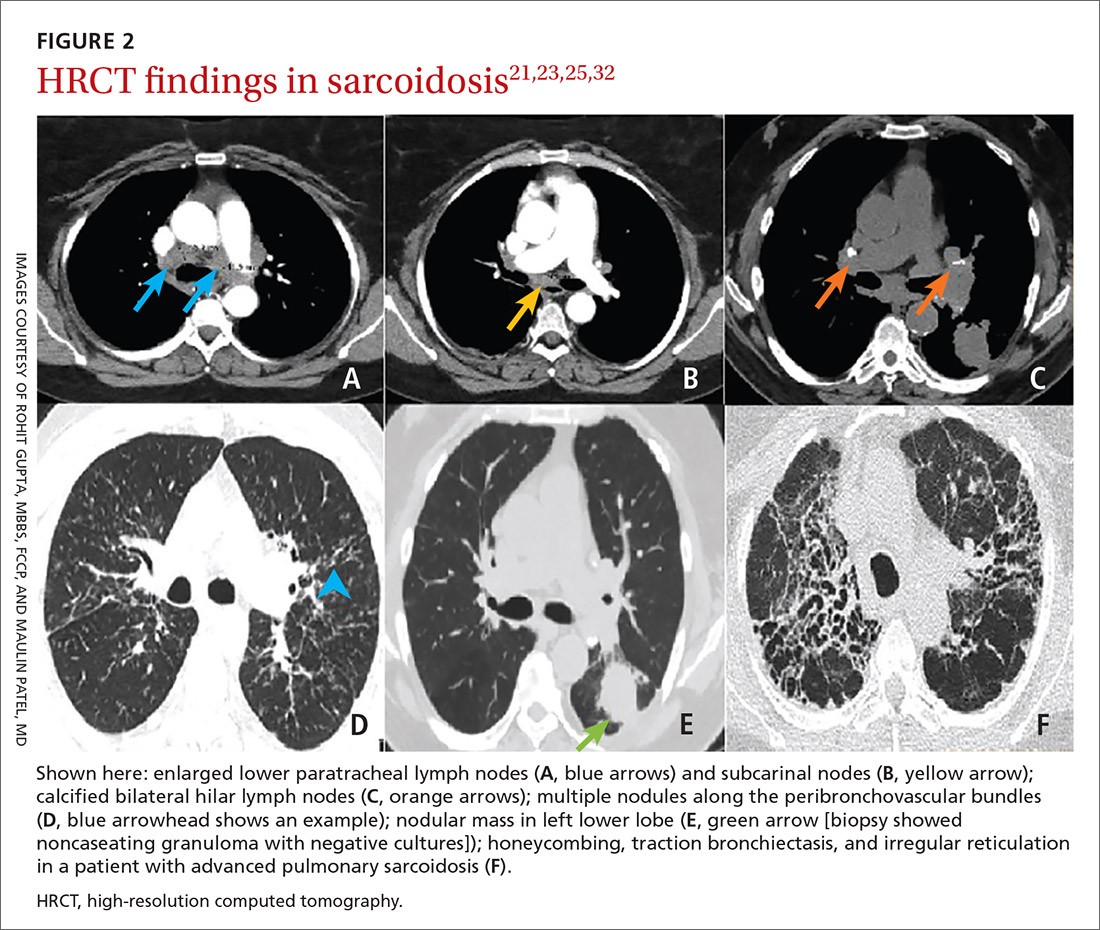

High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT). Micronodules in a perilymphatic distribution with upper lobe predominance combined with subcarinal and symmetrical hilar lymph node enlargement is practically diagnostic of sarcoidosis in the right clinical context. TABLE 321,23,25,32 and FIGURE 221,23,25,32 summarize the common CT chest findings of sarcoidosis.

Advanced imaging such as (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are used in specialized settings for advanced pulmonary, cardiac, or neurosarcoidosis.

Tissue biopsy

Skin lesions (other than erythema nodosum), eye lesions, and peripheral lymph nodes are considered the safest extrapulmonary locations for biopsy.21,25 If pulmonary infiltrates or lymphadenopathy are present, or if extrapulmonary biopsy sites are not available, then flexible bronchoscopy with biopsy is the mainstay for tissue sampling.25

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), transbronchial biopsy (TBB), endobronchial biopsy (EBB), and endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) are invaluable modalities that have reduced the need for open lung biopsy. BAL in sarcoidosis can show lymphocytosis > 15% (nonspecific) and a CD4:CD8 lymphocyte ratio > 3.5 (specificity > 90%).21,22 TBB is more sensitive than EBB; however, sensitivity overall is heightened when both of them are combined. The advent of EBUS has increased the safety and efficiency of needle aspiration of mediastinal lymph nodes. Diagnostic yield of EBUS (~80%) is superior to that with TBB and EBB (~50%), especially in stage I and II sarcoidosis.37 The combination of EBUS with TBB improves the diagnostic yield to ~90%.37

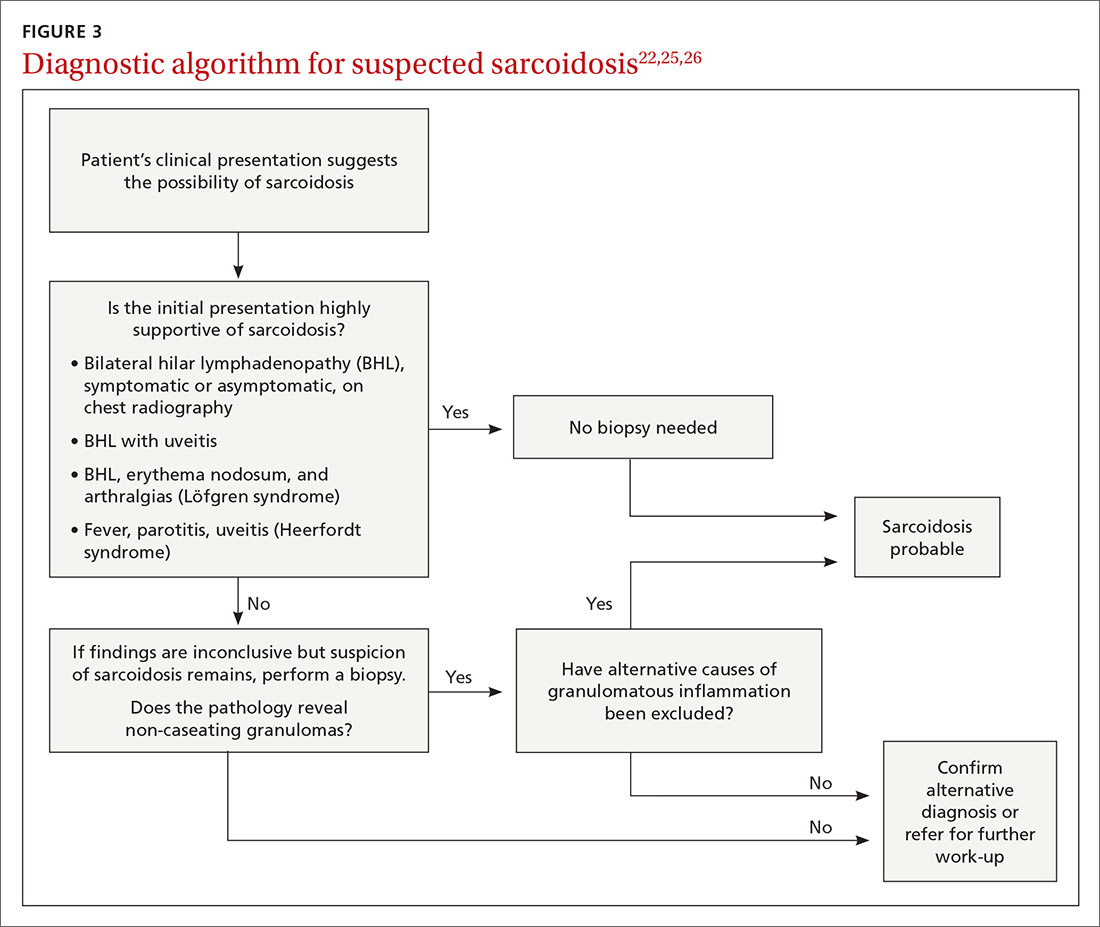

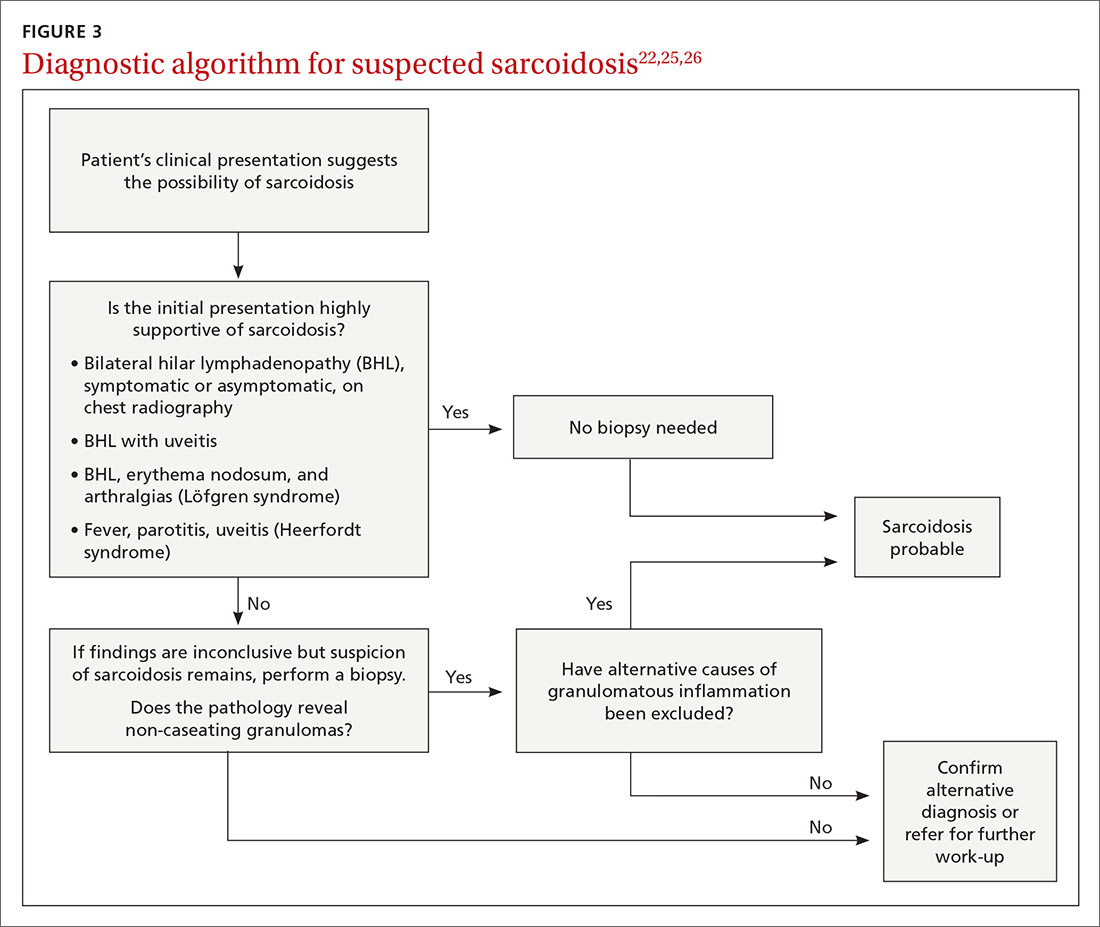

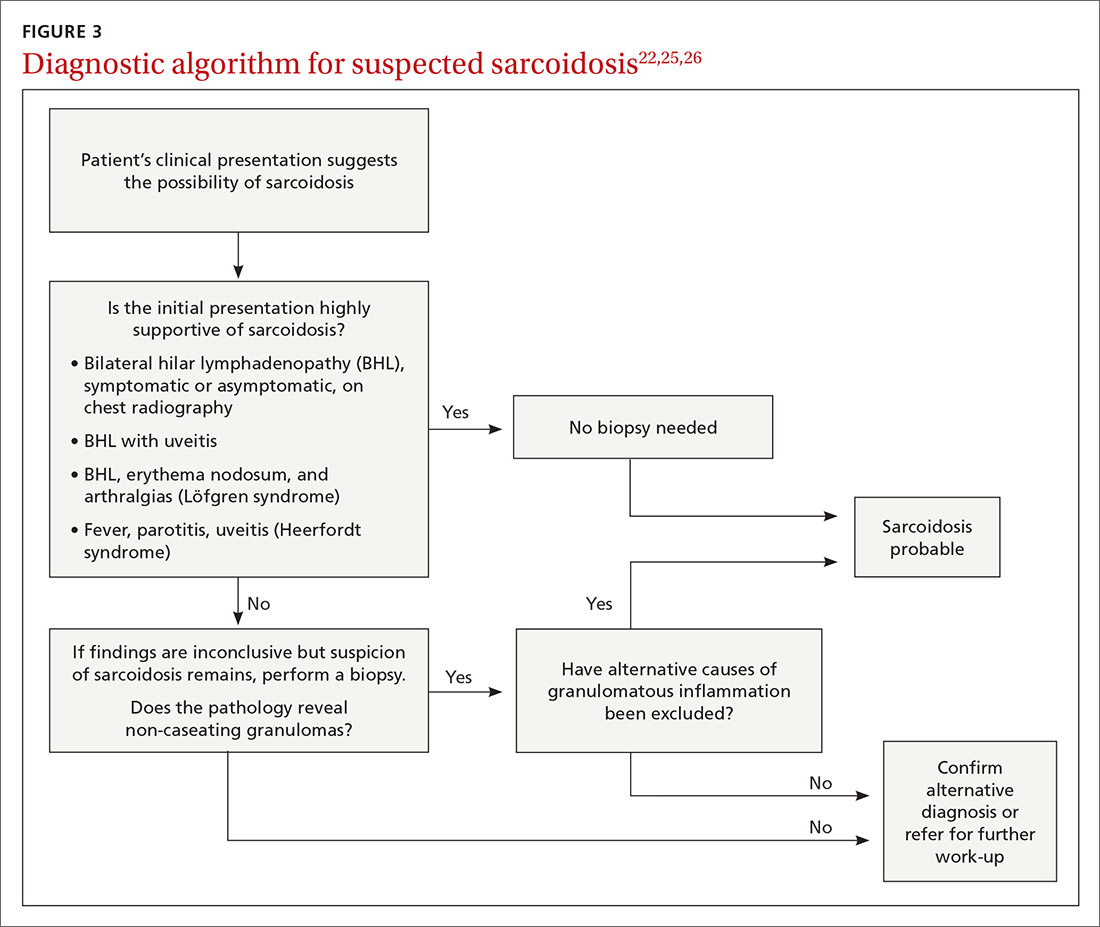

The decision to obtain biopsy samples hinges on the nature of clinical and radiologic findings (FIGURE 3).22,25,26

Continue to: Laboratory studies

Laboratory studies

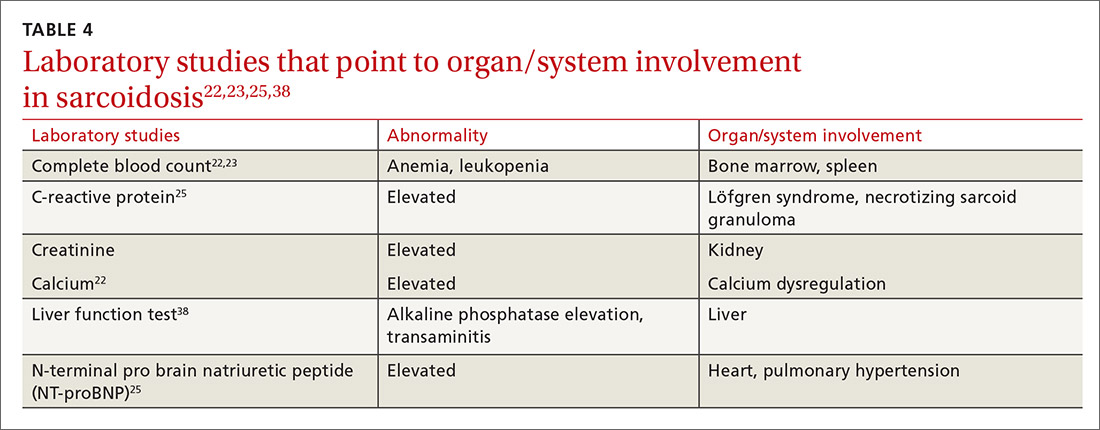

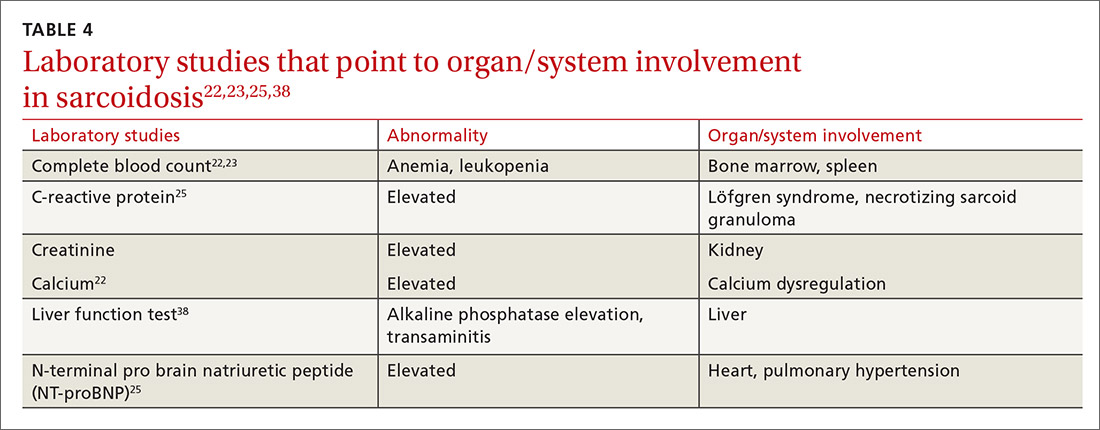

Multiple abnormalities may be seen in sarcoidosis, and specific lab tests may help support a diagnosis of sarcoidosis or detect organ-specific disease activity (TABLE 4).22,23,25,38 However, no consistently accurate biomarkers exist for use in clinical practice. An angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) level greater than 2 times the upper limit of normal may be helpful; however, sensitivity remains low, and genetic polymorphisms can influence the ACE level.25 Biomarkers sometimes used to assess disease activity are serum interleukin-2 receptor, neopterin, chitotriosidase, lysozyme, KL-6 glycoprotein, and amyloid A.21

Additional tests to assess specific features or organ involvement

Pulmonary function testing (PFT) is reviewed in detail below under “pulmonary sarcoidosis.”

Electrocardiogram (EKG)/transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE). EKG abnormalities—conduction disturbances, arrhythmias, or nonspecific ST segment and T-wave changes—are the most common nonspecific findings.30 TTE findings are also nonspecific but have value in assessing cardiac chamber size and function and myocardial involvement. TTE is indeed the most common screening modality for sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary hypertension (SAPH), which is definitively diagnosed by right heart catheterization (RHC). Further evaluation for cardiac sarcoidosis can be done with cardiac MRI or fluorodeoxyglucose PET in specialized settings.

Lumbar puncture (LP) may reveal lymphocytic infiltration in suspected neurosarcoidosis, but the finding is nonspecific and can reflect infection or malignancy. Oligoclonal bands may also be seen in about one-third of neurosarcoidosis cases, and it is imperative to rule out multiple sclerosis.28

Pulmonary sarcoidosis

Pulmonary sarcoidosis accounts for most of the morbidity, mortality, and health care use associated with sarcoidosis.39,40

Continue to: Pathology of early and advanced pulmonary sarcoidosis

Pathology of early and advanced pulmonary sarcoidosis

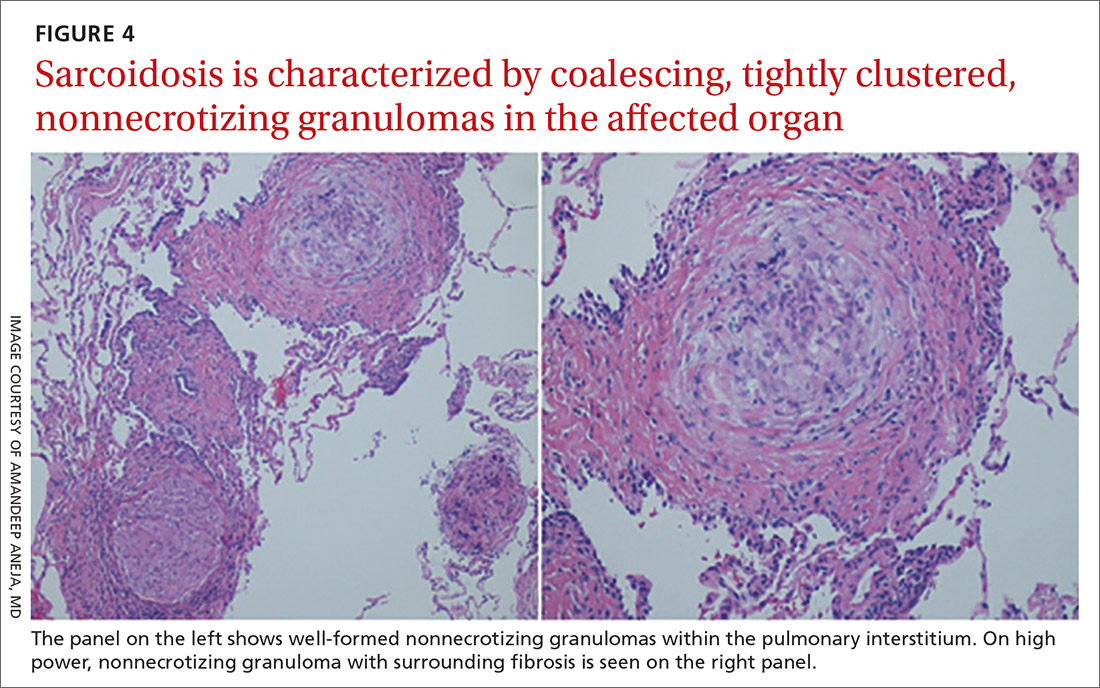

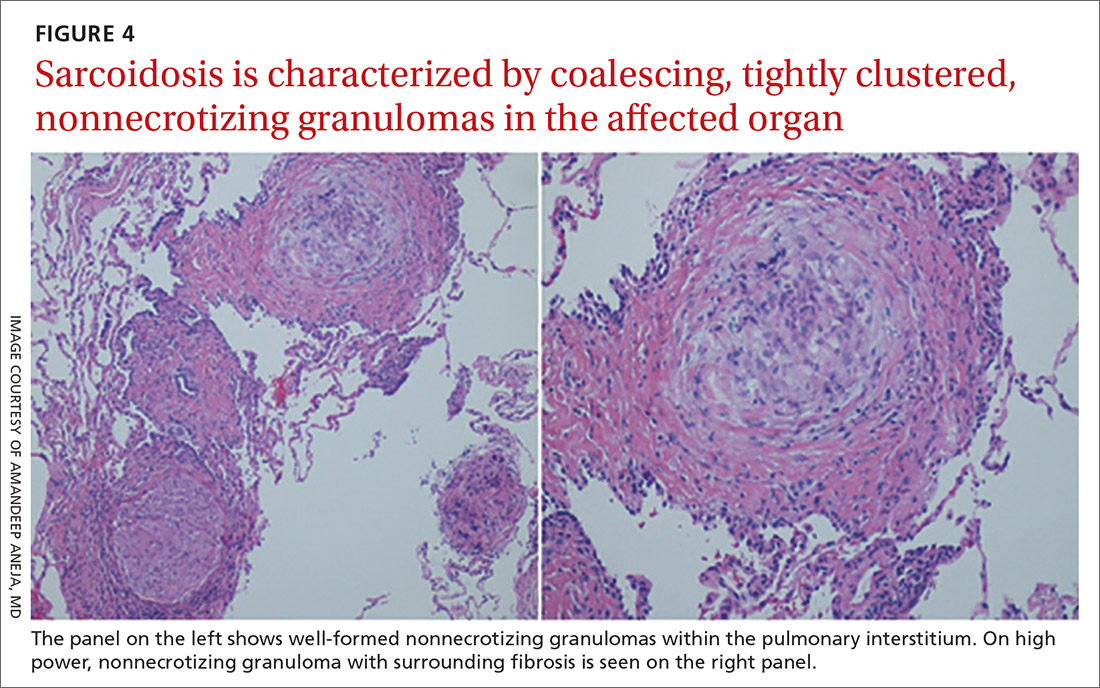

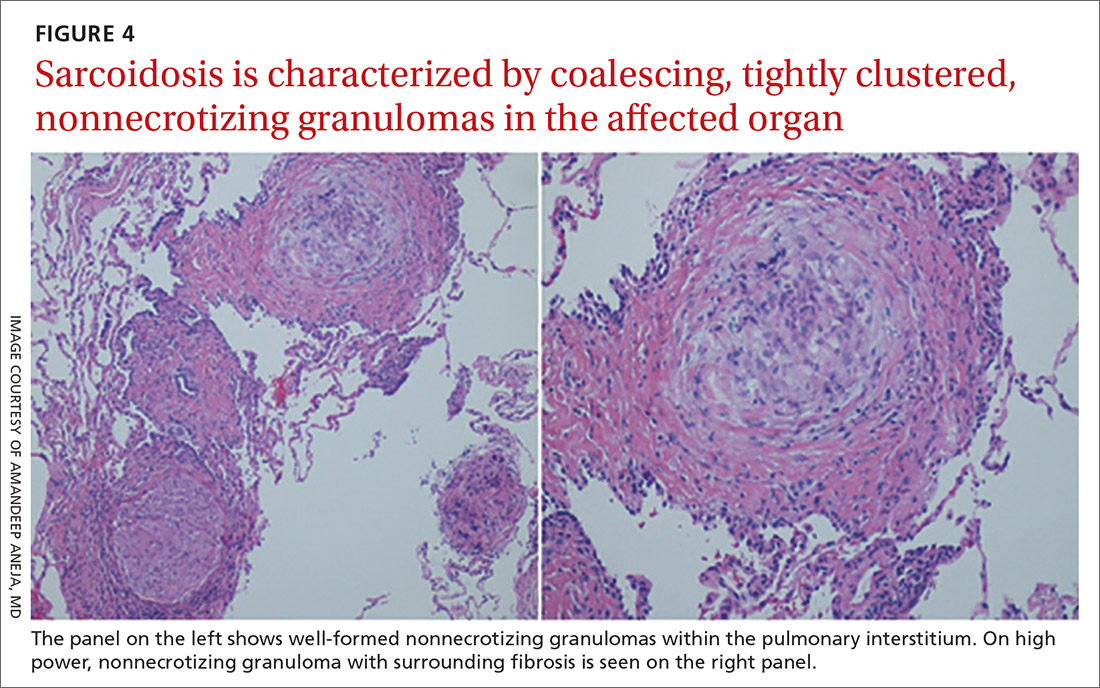

Sarcoidosis is characterized by coalescing, tightly clustered, nonnecrotizing granulomas in the lung (FIGURE 4), most often located along the lymphatic routes of the pleura, interlobular septa, and bronchovascular bundles.41 Granulomas contain epithelioid cells or multinucleated giant cells surrounded by a chronic lymphocytic infiltrate. Typically, intracytoplasmic inclusions, such as Schaumann bodies, asteroid bodies, and blue bodies of calcium oxalates are noted within giant cells.

In chronic disease, lymphocytic infiltrate vanishes and granulomas tend to become increasingly fibrotic and enlarge to form hyalinized nodules rich with densely eosinophilic collagen. In 10% to 30% of cases, the lungs undergo progressive fibrosis.40 Nonresolving inflammation appears to be the major cause of fibrosis and the peribronchovascular localization leading to marked bronchial distortion.

Clinical features, monitoring, and outcomes

Pulmonary involvement occurs in most patients with sarcoidosis, and subclinical pulmonary disease is generally present, even when extrathoracic manifestations predominate.23 Dry cough, dyspnea, and chest discomfort are the most common symptoms. Chest auscultation is usually unremarkable. Wheezing is more common in those with fibrosis and is attributed to airway-centric fibrosis.42 There is often a substantial delay between the onset of symptoms and the diagnosis of pulmonary sarcoidosis, as symptoms are nonspecific and might be mistaken for more common pulmonary diseases, such as asthma or chronic bronchitis.43

Since sarcoidosis can affect pulmonary parenchyma, interstitium, large and small airways, pulmonary vasculature, and respiratory muscles, the pattern of lung function impairment on PFT varies from normal to obstruction, restriction, isolated diffusion defect, or a combination of these. The typical physiologic abnormality is a restrictive ventilatory defect with a decreased diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO). Extent of disease seen on HRCT correlates with level of restriction.44 Airway obstruction can be multifactorial and due to airway distortion (more likely to occur in fibrotic lung disease) and luminal disease.45-48 The 6-minute walk test and DLCO can also aid in the diagnosis of SAPH and advanced parenchymal lung disease.

While monitoring is done clinically and with testing (PFT and imaging) as needed, the optimal approach is unclear. Nevertheless, longitudinal monitoring with testing may provide useful management and prognostic information.40 Pulmonary function can remain stable in fibrotic sarcoidosis over extended periods and actually can improve in some patients.49 Serial spirometry, particularly forced vital capacity, is the most reliable tool for monitoring; when a decline in measurement occurs, chest radiography can elucidate the mechanism.50,51

Continue to: Because sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease...

Because sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease, caution needs to be exercised when evaluating a patient’s new or worsening respiratory symptoms to accurately determine the cause of symptoms and direct therapy accordingly. In addition to refractory inflammatory pulmonary disease, airway disease, infection, fibrosis, and SAPH, one needs to consider extrapulmonary involvement or complications such as cardiac or neurologic disease, musculoskeletal disease, depression, or fatigue. Adverse medication effects, deconditioning, or unrelated (or possibly related) disorders (eg pulmonary embolism) may be to blame.

Determining prognosis

Prognosis of sarcoidosis varies and depends on epidemiologic factors, clinical presentation, and course, as well as specific organ involvement. Patients may develop life-threatening pulmonary, cardiac, or neurologic complications. End-stage disease may require organ transplantation for eligible patients.

Most patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis experience clinical remission with minimal residual organ impairment and a favorable long-term outcome. Advanced pulmonary disease (known as APS) occurs in a small proportion of patients with sarcoidosis but accounts for most of the poor outcomes in sarcoidosis.40 APS is variably defined, but it generally includes pulmonary fibrosis, SAPH, and respiratory infection.

One percent to 5% of patients with sarcoidosis die from complications, and mortality is higher in women and African Americans.52 Mortality and morbidity may be increasing.53 The reasons behind these trends are unclear but could include true increases in disease incidence, better detection rates, greater severity of disease, or an aging population. Increased hospitalizations and health care use might be due to organ damage from granulomatous inflammation (and resultant fibrosis), complications associated with treatment, and psychosocial effects of the disease/treatment.

Management

Management consists primarily of anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive therapies but can also include measures to address specific complications (such as fatigue) and organ transplant, as well as efforts to counter adverse medication effects. Other supportive and preventive measures may include, on a case-by-case basis, oxygen supplementation, vaccinations, or pulmonary rehabilitation. Details of these are found in other, more in-depth reviews on treatment; we will briefly review anti-inflammatory therapy, which forms the cornerstone of treatment in most patients with sarcoidosis.

Continue to: General approach to treatment decisions

General approach to treatment decisions. Anti-inflammatory therapy is used to reduce granulomatous inflammation, thereby preserving organ function and reducing symptoms. A decision to begin treatment is one shared with the patient and is based on symptoms and potential danger of organ system failure.54 Patients who are symptomatic or have progressive disease or physiologic impairment are generally candidates for treatment. Monitoring usually suffices for those who have minimal symptoms, stable disease, and preserved organ function.

Patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis at CXR stage 0 should not receive treatment, given that large, randomized trials have shown no meaningful benefit and that these patients have a high likelihood of spontaneous remission and excellent long-term prognosis.55-58 However, a subgroup of patients classified as stage 0/I on CXR may show parenchymal disease on HRCT,59 and, if more symptomatic, could be considered for treatment. For patients with stage II to IV pulmonary sarcoidosis with symptoms, there is good evidence that treatment may improve lung function and reduce dyspnea and fatigue.57,60-62

Corticosteroids are first-line treatment for most patients. Based on expert opinion, treatment of pulmonary sarcoidosis is generally started with oral prednisone (or an equivalent corticosteroid). A starting dose of 20 to 40 mg/d generally is sufficient for most patients. If the patient responds to initial treatment, prednisone dose is tapered over a period of months. If symptoms worsen during tapering, the minimum effective dose is maintained without further attempts at tapering. Treatment is continued for at least 3 to 6 months but it might be needed for longer durations; unfortunately, evidence-based guidelines are lacking.63 Once the patient goes into remission, close monitoring is done for possible relapses. Inhaled corticosteroids alone have not reduced symptoms or improved lung function in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis.64-66

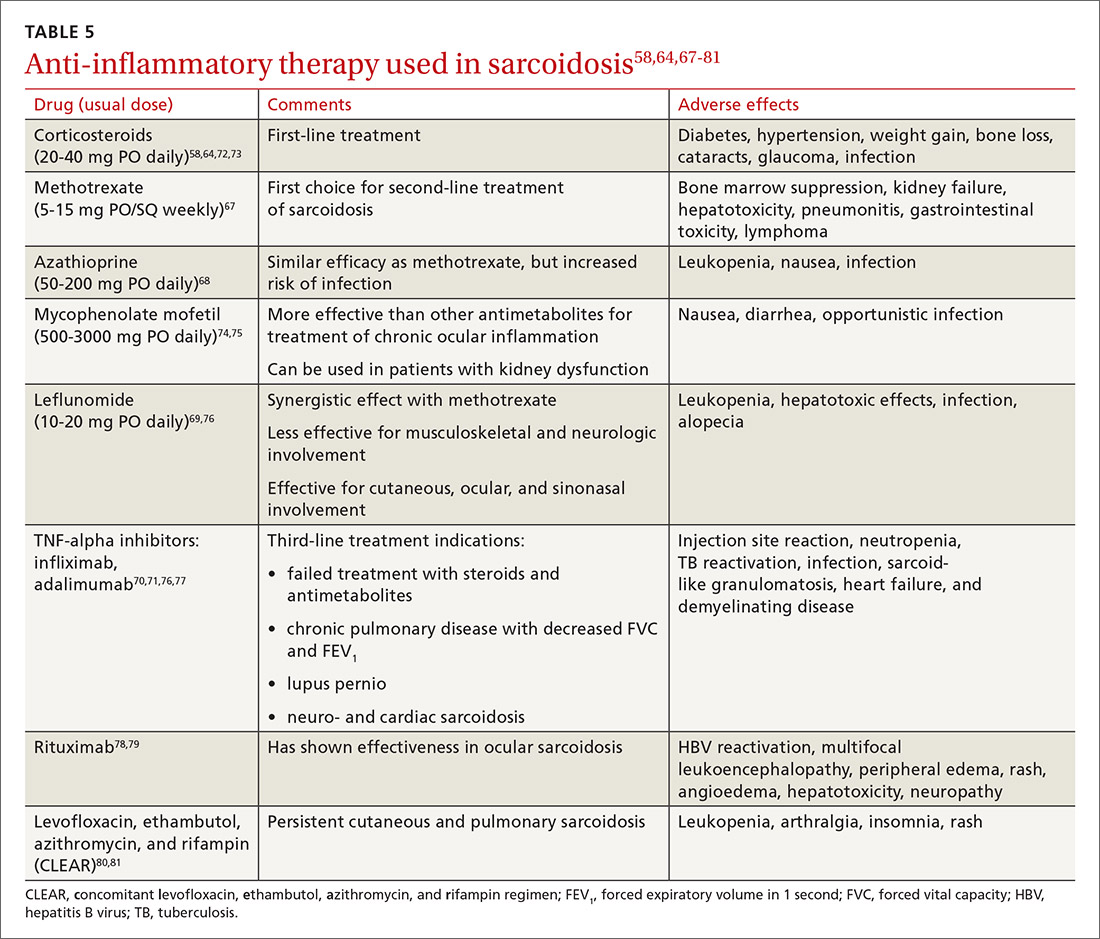

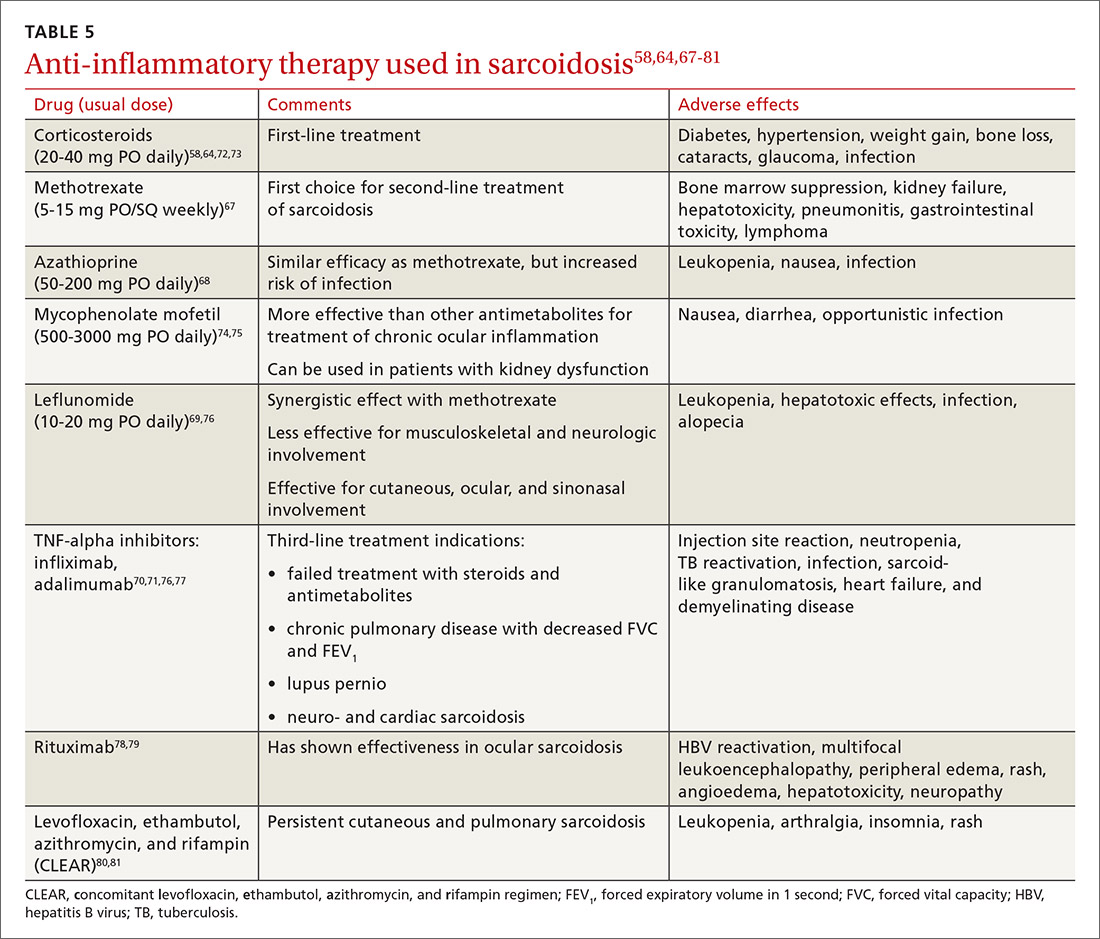

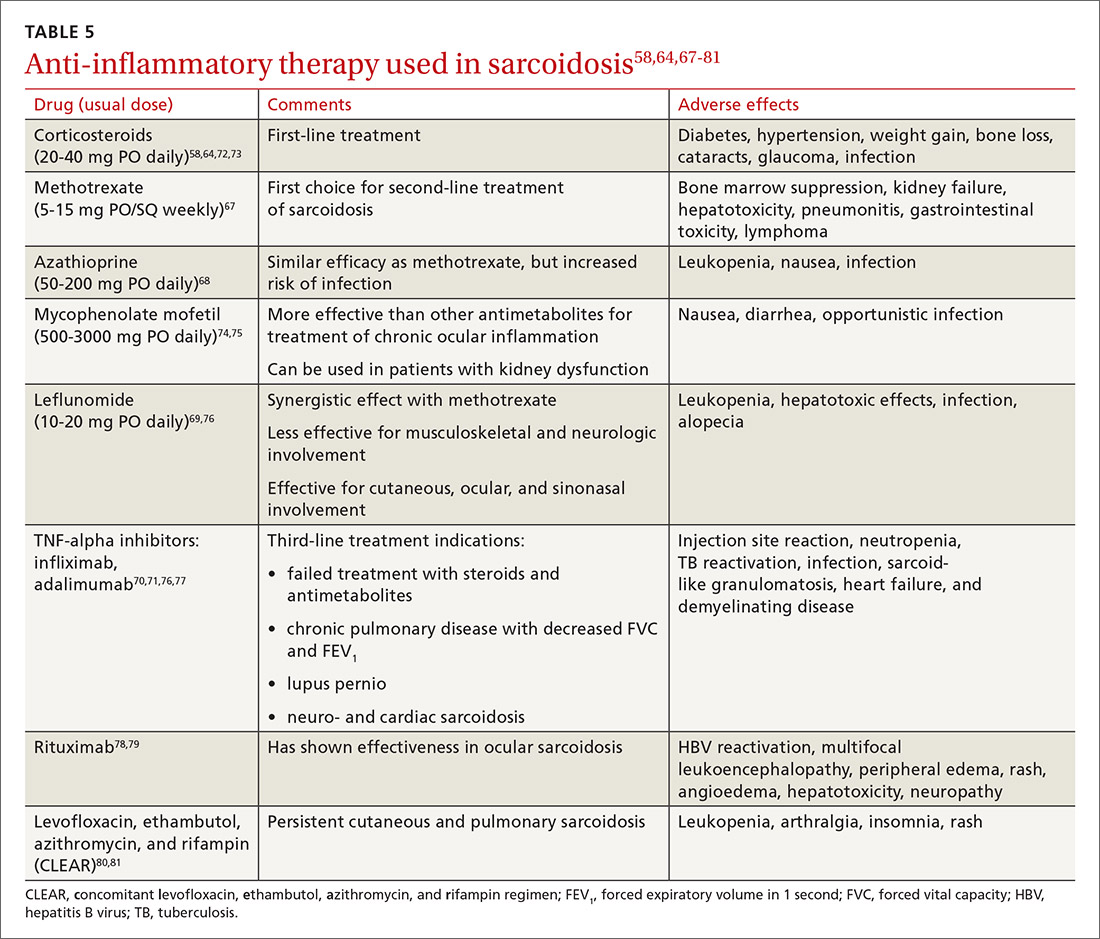

Steroid-sparing agents are added for many patients. For patients receiving chronic prednisone therapy (≥ 10 mg for > 6 months), steroid-sparing agents are considered to minimize the adverse effects of steroids or to better control the inflammatory activity of sarcoidosis. These agents must be carefully selected, and clinical and laboratory monitoring need to be done throughout therapy. TABLE 558,64,67-81

The management might be complicated for extrapulmonary, multi-organ, and advanced sarcoidosis (advanced pulmonary sarcoidosis, cardiac disease, neurosarcoidosis, lupus pernio, etc) when specialized testing, as well as a combination of corticosteroids and steroid-sparing agents (with higher doses or prolonged courses), might be needed. This should be performed at an expert sarcoidosis center, ideally in a multidisciplinary setting involving pulmonologists and/or rheumatologists, chest radiologists, and specialists as indicated, based on specific organ involvement.

Continue to: Research and future directions

Research and future directions

Key goals for research are identifying more accurate biomarkers of disease, improving diagnosis of multi-organ disease, determining validated endpoints of clinical trials in sarcoidosis, and developing treatments for refractory cases.

There is optimism and opportunity in the field of sarcoidosis overall. An example of an advancement is in the area of APS, as the severity and importance of this phenotype has been better understood. Worldwide registries and trials of pulmonary vasodilator therapy (bosentan, sildenafil, epoprostenol, and inhaled iloprost) in patients with SAPH without left ventricular dysfunction are promising.82-85 However, no benefit in survival has been shown.

RioSAPH is a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of Riociguat (a stimulator of soluble guanylate cyclase) for SAPH (NCT02625558) that is closed to enrollment and undergoing data review. Similarly, results of the phase IV study of pirfenidone, an antifibrotic agent that was shown to decrease disease progression and deaths in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis,86 are awaited in the near future.

Other potential directions being explored are multicenter patient registries and randomized controlled trials, analyses of existing databases, use of biobanking, and patient-centered outcome measures. Hopefully, the care of patients with sarcoidosis will become more evidence based with ongoing and upcoming research in this field.

CORRESPONDENCE

Rohit Gupta, MBBS, FCCP, 3401 North Broad Street, 7 Parkinson Pavilion, Philadelphia, PA 19140; [email protected]

1. Costabel U, Hunninghake G. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Statement Committee. American Thoracic Society. European Respiratory Society. World Association for Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:735-737.

2. Hillerdal G, Nöu E, Osterman K, et al. Sarcoidosis: epidemiology and prognosis. A 15-year European study. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;130:29-32.

3. Mirsaeidi M, Machado RF, Schraufnagel D, et al. Racial difference in sarcoidosis mortality in the United States. Chest. 2015;147:438-449.

4. Rybicki BA, Iannuzzi MC, Frederick MM, et al. Familial aggregation of sarcoidosis. A case-control etiologic study of sarcoidosis (ACCESS). Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2001;164:2085-2091.

5. Sverrild A, Backer V, Kyvik KO, et al. Heredity in sarcoidosis:a registry-based twin study. Thorax. 2008;63:894.

6. Vuyst P, Dumortier P, Schandené L, et al. Sarcoidlike lung granulomatosis induced by aluminum dusts. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;135:493-497.

7. Werfel U, Schneider J, Rödelsperger K, et al. Sarcoid granulomatosis after zirconium exposure with multiple organ involvement. European Respir J. 1998;12:750.

8. Newman KL, Newman LS. Occupational causes of sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:145-150.

9. Zissel G, Müller-Quernheim J. Specific antigen(s) in sarcoidosis:a link to autoimmunity? Eur Respir J. 2016;47:707-709.

10. Chen ES, Moller DR. Etiology of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2008;29:365-377.

11. Agostini C, Adami F, Semenzato G. New pathogenetic insights into the sarcoid granuloma. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2000;12:71-76.

12. Valentonyte R, Hampe J, Huse K, et al. Sarcoidosis is associated with a truncating splice site mutation in BTNL2. Nat Genet. 2005;37:357-364.

13. Rybicki BA, Walewski JL, Maliarik MJ, et al. The BTNL2 gene and sarcoidosis susceptibility in African Americans and Whites. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:491-499.

14. Newman LS, Rose CS, Bresnitz EA, et al. A case control etiologic study of sarcoidosis: environmental and occupational risk factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:1324-1330.

15. Gorham ED, Garland CF, Garland FC, et al. Trends and occupational associations in incidence of hospitalized pulmonary sarcoidosis and other lung diseases in Navy personnel: a 27-year historical prospective study, 1975-2001. Chest. 2004;126:1431-1438.

16. Kucera GP, Rybicki BA, Kirkey KL, et al. Occupational risk factors for sarcoidosis in African-American siblings. Chest. 2003;123:1527-1535.

17. Prezant DJ, Dhala A, Goldstein A, et al. The incidence, prevalence, and severity of sarcoidosis in New York City firefighters. Chest. 1999;116:1183-1193.

18. Barnard J, Rose C, Newman L, et al. Job and industry classifications associated with sarcoidosis in A Case–Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis (ACCESS). J Occup Environ Med. 2005;47:226-234.

19. Izbicki G, Chavko R, Banauch GI, et al. World Trade Center “sarcoid-like” granulomatous pulmonary disease in New York City Fire Department rescue workers. Chest. 2007;131:1414-1423.

20. Eishi Y, Suga M, Ishige I, et al. Quantitative analysis of mycobacterial and propionibacterial DNA in lymph nodes of Japanese and European patients with sarcoidosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:198-204.

21. Valeyre D, Prasse A, Nunes H, et al. Sarcoidosis. Lancet. 2014;383:1155-1167.

22. Crouser ED, Maier LA, Wilson KC, et al. Diagnosis and detection of sarcoidosis. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:e26-51.

23. Judson MA, ed. Pulmonary Sarcoidosis: A Guide for the Practicing Clinician. Springer; 2014.

24. Govender P, Berman JS. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:585-602.

25. Valeyre D, Bernaudin J-F, Uzunhan Y, et al. Clinical presentation of sarcoidosis and diagnostic work-up. Semin Resp Crit Care Med. 2014;35:336-351.

26. Judson MA. The clinical features of sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015;49:63-78.

27. Wanat KA, Rosenbach M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:685-702.

28. Culver DA, Neto ML, Moss BP, et al. Neurosarcoidosis. Semin Resp Crit Care Med. 2017;38:499-513.

29. Pasadhika S, Rosenbaum JT. Ocular sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:669-683.

30. Sayah DM, Bradfield JS, Moriarty JM, et al. Cardiac involvement in sarcoidosis: evolving concepts in diagnosis and treatment. Semin Resp Crit Care Med. 2017;38:477-498.

31. Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Resp Crit Care. 2012;164:1885-1889.

32. Keijsers RG, Veltkamp M, Grutters JC. Chest imaging. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:603-619.

33. Scadding J. Prognosis of intrathoracic sarcoidosis in England. A review of 136 cases after five years’ observation. Brit Med J. 1961;2:1165-1172.

34. Miller B, Putman C. The chest radiograph and sarcoidosis. Reevaluation of the chest radiograph in assessing activity of sarcoidosis: a preliminary communication. Sarcoidosis. 1985;2:85-90.

35. Loddenkemper R, Kloppenborg A, Schoenfeld N, et al. Clinical findings in 715 patients with newly detected pulmonary sarcoidosis--results of a cooperative study in former West Germany and Switzerland. WATL Study Group. Wissenschaftliche Arbeitsgemeinschaft für die Therapie von Lungenkrankheitan. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1998;15:178-182.

36. Calandriello L, Walsh SLF. Imaging for sarcoidosis. Semin Resp Crit Care Med. 2017;38:417-436.

37. Gupta D, Dadhwal DS, Agarwal R, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration vs conventional transbronchial needle aspiration in the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Chest. 2014;146:547-556.

38. Baydur A. Recent developments in the physiological assessment of sarcoidosis: clinical implications. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2012;18:499-505.

39. Jamilloux Y, Maucort-Boulch D, Kerever S, et al. Sarcoidosis-related mortality in France: a multiple-cause-of-death analysis. Eur Respir J. 2016;48:1700-1709.

40. Gupta R, Baughman RP. Advanced pulmonary sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41:700-715.

41. Rossi G, Cavazza A, Colby TV. Pathology of sarcoidosis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015;49:36-44.

42. Hansell D, Milne D, Wilsher M, et al. Pulmonary sarcoidosis: morphologic associations of airflow obstruction at thin-section CT. Radiology. 1998;209:697-704.

43. Judson MA, Thompson BW, Rabin DL, et al. The diagnostic pathway to sarcoidosis. Chest. 2003;123:406-412.

44. Müller NL, Mawson JB, Mathieson JR, et al. Sarcoidosis: correlation of extent of disease at CT with clinical, functional, and radiographic findings. Radiology. 1989;171:613-618.

45. Harrison BDW, Shaylor JM, Stokes TC, et al. Airflow limitation in sarcoidosis—a study of pulmonary function in 107 patients with newly diagnosed disease. Resp Med. 1991;85:59-64.

46. Polychronopoulos VS, Prakash UBS. Airway Involvement in sarcoidosis. Chest. 2009;136:1371-1380.

47. Chambellan A, Turbie P, Nunes H, et al. Endoluminal stenosis of proximal bronchi in sarcoidosis: bronchoscopy, function, and evolution. Chest. 2005;127:472-481.

48. Handa T, Nagai S, Fushimi Y, et al. Clinical and radiographic indices associated with airflow limitation in patients with sarcoidosis. Chest. 2006;130:1851-1856.

49. Nardi A, Brillet P-Y, Letoumelin P, et al. Stage IV sarcoidosis: comparison of survival with the general population and causes of death. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:1368-1373.

50. Zappala CJ, Desai SR, Copley SJ, et al. Accuracy of individual variables in the monitoring of long-term change in pulmonary sarcoidosis as judged by serial high-resolution CT scan data. Chest. 2014;145:101-107.

51. Gafà G, Sverzellati N, Bonati E, et al. Follow-up in pulmonary sarcoidosis: comparison between HRCT and pulmonary function tests. Radiol Med. 2012;117:968-978.

52. Gerke AK. Morbidity and mortality in sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2014;20:472-478.

53. Kearney GD, Obi ON, Maddipati V, et al. Sarcoidosis deaths in the United States: 1999–2016. Respir Med. 2019;149:30-35.

54. Baughman RP, Judson M, Wells A. The indications for the treatment of sarcoidosis: Wells Law. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2017;34:280-282.

55. Nagai S, Shigematsu M, Hamada K, et al. Clinical courses and prognoses of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 1999;5:293-298.

56. Neville E, Walker AN, James DG. Prognostic factors predicting the outcome of sarcoidosis: an analysis of 818 patients. Q J Med. 1983;52:525-533.

57. Bradley B, Branley HM, Egan JJ, et al. Interstitial lung disease guideline: the British Thoracic Society in collaboration with the Thoracic Society of Australia and the Irish Thoracic Society. Thorax. 2008;63(suppl 5):v1-v58.

58. Pietinalho A, Tukiainen P, Haahtela T, et al. Oral prednisolone followed by inhaled budesonide in newly diagnosed pulmonary sarcoidosis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study. Finnish Pulmonary Sarcoidosis Group. Chest. 1999;116:424-431.

59. Oberstein A, von Zitzewitz H, Schweden F, et al. Non invasive evaluation of the inflammatory activity in sarcoidosis with high-resolution computed tomography. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1997;14:65-72.

60. Gibson G, Prescott RJ, Muers MF, et al. British Thoracic Society Sarcoidosis study: effects of long term corticosteroid treatment. Thorax. 1996;51:238-247.

61. Baughman RP, Nunes H. Therapy for sarcoidosis: evidence-based recommendations. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2012;8:95-103.

62. Pietinalho A, Tukiainen P, Haahtela T, et al. Early treatment of stage II sarcoidosis improves 5-year pulmonary function. Chest. 2002;121:24-31.

63. Rahaghi FF, Baughman RP, Saketkoo LA, et al. Delphi consensus recommendations for a treatment algorithm in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Eur Respir Rev. 2020;29:190146.

64. Baughman RP, Iannuzzi MC, Lower EE, et al. Use of fluticasone in acute symptomatic pulmonary sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2002;19:198-204.

65. du Bois RM, Greenhalgh PM, Southcott AM, et al. Randomized trial of inhaled fluticasone propionate in chronic stable pulmonary sarcoidosis: a pilot study. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:1345-1350.

66. Milman N, Graudal N, Grode G, Munch E. No effect of high‐dose inhaled steroids in pulmonary sarcoidosis: a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. J Intern Med. 1994;236:285-290.

67. Baughman RP, Winget DB, Lower EE. Methotrexate is steroid sparing in acute sarcoidosis: results of a double blind, randomized trial. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2000;17:60-66.

68. Vorselaars ADM, Wuyts WA, Vorselaars VMM, et al. Methotrexate vs azathioprine in second-line therapy of sarcoidosis. Chest. 2013;144:805-812.

69. Sahoo D, Bandyopadhyay D, Xu M, et al. Effectiveness and safety of leflunomide for pulmonary and extrapulmonary sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:1145-1150.

70. Baughman RP, Drent M, Kavuru M, et al. Infliximab therapy in patients with chronic sarcoidosis and pulmonary involvement. Am J Resp Crit Care Med . 2006;174:795-802.

71. Rossman MD, Newman LS, Baughman RP, et al. A double-blinded, randomized, placebo-controlled trial of infliximab in subjects with active pulmonary sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis . 2006;23:201-208.

72. Selroos O, Sellergren T. Corticosteroid therapy of pulmonary sarcoidosis. A prospective evaluation of alternate day and daily dosage in stage II disease. Scand J Respir Dis . 1979;60:215-221.

73. Israel HL, Fouts DW, Beggs RA. A controlled trial of prednisone treatment of sarcoidosis. Am Rev Respir Dis . 1973;107:609-614.

74. Hamzeh N, Voelker A, Forssén A, et al. Efficacy of mycophenolate mofetil in sarcoidosis. Respir Med . 2014;108:1663-1669.

75. Brill A-K, Ott SR, Geiser T. Effect and safety of mycophenolate mofetil in chronic pulmonary sarcoidosis: a retrospective study. Respiration . 2013;86:376-383.

76. Baughman RP, Lower EE. Leflunomide for chronic sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis . 2004;21:43-48.

77. Sweiss NJ, Noth I, Mirsaeidi M, et al. Efficacy results of a 52-week trial of adalimumab in the treatment of refractory sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis . 2014;31:46-54.

78. Sweiss NJ, Lower EE, Mirsaeidi M, et al. Rituximab in the treatment of refractory pulmonary sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J . 2014;43:1525-1528.

79. Thatayatikom A, Thatayatikom S, White AJ. Infliximab treatment for severe granulomatous disease in common variable immunodeficiency: a case report and review of the literature. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol . 2005;95:293-300.

80. Drake WP, Oswald-Richter K, Richmond BW, et al. Oral antimycobacterial therapy in chronic cutaneous sarcoidosis: a randomized, single-masked, placebo-controlled study. Jama Dermatol . 2013;149:1040-1049.

81. Drake WP, Richmond BW, Oswald-Richter K, et al. Effects of broad-spectrum antimycobacterial therapy on chronic pulmonary sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis . 2013;30:201-211.

82. Baughman RP, Culver DA, Cordova FC, et al. Bosentan for sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary hypertension: a double-blind placebo controlled randomized trial. Chest . 2014;145:810-817.

83. Baughman RP, Shlobin OA, Wells AU, et al. Clinical features of sarcoidosis associated pulmonary hypertension: results of a multi-national registry. Respir Med . 2018;139:72-78.

84. Fisher KA, Serlin DM, Wilson KC, et al. Sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary hypertension outcome with long-term epoprostenol treatment. Chest . 2006;130:1481-1488.

85. Baughman RP, Judson MA, Lower EE, et al. Inhaled iloprost for sarcoidosis associated pulmonary hypertension. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis . 2009;26:110-120.

86. King TE, Bradford WZ, Castro-Bernardini S, et al. A phase 3 trial of pirfenidone in patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. N Engl J Med . 2014;370:2083-2092.

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disease of unclear etiology that primarily affects the lungs. It can occur at any age but usually develops before the age of 50 years, with an initial peak incidence at 20 to 29 years and a second peak incidence after 50 years of age, especially among women in Scandinavia and Japan.1 Sarcoidosis affects men and women of all racial and ethnic groups throughout the world, but differences based on race, sex, and geography are noted.1

The highest rates are reported in northern European and African-American individuals, particularly in women.1,2 The adjusted annual incidence of sarcoidosis among African Americans is approximately 3 times that among White Americans3 and is more likely to be chronic and fatal in African Americans.3 The disease can be familial with a possible recessive inheritance mode with incomplete penetrance.4 Risk of sarcoidosis in monozygotic twins appears to be 80 times greater than that in the general population, which supports genetic factors accounting for two-thirds of disease susceptibility.5

Likely factors in the development of sarcoidosis

The exact cause of sarcoidosis is unknown, but we have insights into its pathogenesis and potential triggers.1,6-9 Genes involved are being identified: class I and II human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules are most consistently associated with risk of sarcoidosis. Environmental exposures can activate the innate immune system and precondition a susceptible individual to react to potential causative antigens in a highly polarized, antigen-specific Th1 immune response. The epithelioid granulomatous response involves local proinflammatory cytokine production and enhanced T-cell immunity at sites of inflammation.10 Granulomas generally form to confine pathogens, restrict inflammation, and protect surrounding tissue.11-13

ACCESS (A Case Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis) identified several environmental exposures such as chemicals used in the agriculture industry, mold or mildew, and musty odors at work.14 Tobacco use was not associated with sarcoidosis.14 Recent studies have shown positive associations with service in the US Navy,15 metal working,16 firefighting,17 the handling of building supplies,18 and onsite exposure while assisting in rescue efforts at the World Trade Center disaster.19 Other data support the likelihood that specific environmental exposures associated with microbe-rich environments modestly increase the risk of sarcoidosis.14 Mycobacterial and propionibacterial DNA and RNA are potentially associated with sarcoidosis.20

Clinical manifestations are nonspecific

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis can be difficult and delayed due to diverse organ involvement and nonspecific presentations. TABLE 121-31 shows the diverse manifestations in a patient with suspected sarcoidosis. Around 50% of the patients are asymptomatic.23,24 Sarcoidosis is a diagnosis of exclusion, starting with a detailed history to rule out infections, occupational or environmental exposures, malignancies, and other possible disorders (TABLE 2).22

Diagnostic work-up

Radiologic studies

Chest x-ray (CXR) provides diagnostic and prognostic information in the evaluation of sarcoidosis using the Scadding classification system (FIGURE 1).21,25,32,33 Interobserver variability, especially between stages II and III and III and IV is the major limitation of this system.32 At presentation, radiographs are abnormal in approximately 90% of patients.34 Lymphadenopathy is the most common radiographic abnormality, occurring in more than two-thirds of cases, and pulmonary opacities (nodules and reticulation) with a middle to upper lobe predilection are present in 20% to 50% of patients.1,31,35 The nodules vary in size and can coalesce and cause alveolar collapse, thus producing consolidation.36 Linear opacities radiating laterally from the hilum into the middle and upper zones are characteristic in fibrotic disease.

Continue to: High-resoluton computed tomography

High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT). Micronodules in a perilymphatic distribution with upper lobe predominance combined with subcarinal and symmetrical hilar lymph node enlargement is practically diagnostic of sarcoidosis in the right clinical context. TABLE 321,23,25,32 and FIGURE 221,23,25,32 summarize the common CT chest findings of sarcoidosis.

Advanced imaging such as (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are used in specialized settings for advanced pulmonary, cardiac, or neurosarcoidosis.

Tissue biopsy

Skin lesions (other than erythema nodosum), eye lesions, and peripheral lymph nodes are considered the safest extrapulmonary locations for biopsy.21,25 If pulmonary infiltrates or lymphadenopathy are present, or if extrapulmonary biopsy sites are not available, then flexible bronchoscopy with biopsy is the mainstay for tissue sampling.25

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), transbronchial biopsy (TBB), endobronchial biopsy (EBB), and endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) are invaluable modalities that have reduced the need for open lung biopsy. BAL in sarcoidosis can show lymphocytosis > 15% (nonspecific) and a CD4:CD8 lymphocyte ratio > 3.5 (specificity > 90%).21,22 TBB is more sensitive than EBB; however, sensitivity overall is heightened when both of them are combined. The advent of EBUS has increased the safety and efficiency of needle aspiration of mediastinal lymph nodes. Diagnostic yield of EBUS (~80%) is superior to that with TBB and EBB (~50%), especially in stage I and II sarcoidosis.37 The combination of EBUS with TBB improves the diagnostic yield to ~90%.37

The decision to obtain biopsy samples hinges on the nature of clinical and radiologic findings (FIGURE 3).22,25,26

Continue to: Laboratory studies

Laboratory studies

Multiple abnormalities may be seen in sarcoidosis, and specific lab tests may help support a diagnosis of sarcoidosis or detect organ-specific disease activity (TABLE 4).22,23,25,38 However, no consistently accurate biomarkers exist for use in clinical practice. An angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) level greater than 2 times the upper limit of normal may be helpful; however, sensitivity remains low, and genetic polymorphisms can influence the ACE level.25 Biomarkers sometimes used to assess disease activity are serum interleukin-2 receptor, neopterin, chitotriosidase, lysozyme, KL-6 glycoprotein, and amyloid A.21

Additional tests to assess specific features or organ involvement

Pulmonary function testing (PFT) is reviewed in detail below under “pulmonary sarcoidosis.”

Electrocardiogram (EKG)/transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE). EKG abnormalities—conduction disturbances, arrhythmias, or nonspecific ST segment and T-wave changes—are the most common nonspecific findings.30 TTE findings are also nonspecific but have value in assessing cardiac chamber size and function and myocardial involvement. TTE is indeed the most common screening modality for sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary hypertension (SAPH), which is definitively diagnosed by right heart catheterization (RHC). Further evaluation for cardiac sarcoidosis can be done with cardiac MRI or fluorodeoxyglucose PET in specialized settings.

Lumbar puncture (LP) may reveal lymphocytic infiltration in suspected neurosarcoidosis, but the finding is nonspecific and can reflect infection or malignancy. Oligoclonal bands may also be seen in about one-third of neurosarcoidosis cases, and it is imperative to rule out multiple sclerosis.28

Pulmonary sarcoidosis

Pulmonary sarcoidosis accounts for most of the morbidity, mortality, and health care use associated with sarcoidosis.39,40

Continue to: Pathology of early and advanced pulmonary sarcoidosis

Pathology of early and advanced pulmonary sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is characterized by coalescing, tightly clustered, nonnecrotizing granulomas in the lung (FIGURE 4), most often located along the lymphatic routes of the pleura, interlobular septa, and bronchovascular bundles.41 Granulomas contain epithelioid cells or multinucleated giant cells surrounded by a chronic lymphocytic infiltrate. Typically, intracytoplasmic inclusions, such as Schaumann bodies, asteroid bodies, and blue bodies of calcium oxalates are noted within giant cells.

In chronic disease, lymphocytic infiltrate vanishes and granulomas tend to become increasingly fibrotic and enlarge to form hyalinized nodules rich with densely eosinophilic collagen. In 10% to 30% of cases, the lungs undergo progressive fibrosis.40 Nonresolving inflammation appears to be the major cause of fibrosis and the peribronchovascular localization leading to marked bronchial distortion.

Clinical features, monitoring, and outcomes

Pulmonary involvement occurs in most patients with sarcoidosis, and subclinical pulmonary disease is generally present, even when extrathoracic manifestations predominate.23 Dry cough, dyspnea, and chest discomfort are the most common symptoms. Chest auscultation is usually unremarkable. Wheezing is more common in those with fibrosis and is attributed to airway-centric fibrosis.42 There is often a substantial delay between the onset of symptoms and the diagnosis of pulmonary sarcoidosis, as symptoms are nonspecific and might be mistaken for more common pulmonary diseases, such as asthma or chronic bronchitis.43

Since sarcoidosis can affect pulmonary parenchyma, interstitium, large and small airways, pulmonary vasculature, and respiratory muscles, the pattern of lung function impairment on PFT varies from normal to obstruction, restriction, isolated diffusion defect, or a combination of these. The typical physiologic abnormality is a restrictive ventilatory defect with a decreased diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO). Extent of disease seen on HRCT correlates with level of restriction.44 Airway obstruction can be multifactorial and due to airway distortion (more likely to occur in fibrotic lung disease) and luminal disease.45-48 The 6-minute walk test and DLCO can also aid in the diagnosis of SAPH and advanced parenchymal lung disease.

While monitoring is done clinically and with testing (PFT and imaging) as needed, the optimal approach is unclear. Nevertheless, longitudinal monitoring with testing may provide useful management and prognostic information.40 Pulmonary function can remain stable in fibrotic sarcoidosis over extended periods and actually can improve in some patients.49 Serial spirometry, particularly forced vital capacity, is the most reliable tool for monitoring; when a decline in measurement occurs, chest radiography can elucidate the mechanism.50,51

Continue to: Because sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease...

Because sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease, caution needs to be exercised when evaluating a patient’s new or worsening respiratory symptoms to accurately determine the cause of symptoms and direct therapy accordingly. In addition to refractory inflammatory pulmonary disease, airway disease, infection, fibrosis, and SAPH, one needs to consider extrapulmonary involvement or complications such as cardiac or neurologic disease, musculoskeletal disease, depression, or fatigue. Adverse medication effects, deconditioning, or unrelated (or possibly related) disorders (eg pulmonary embolism) may be to blame.

Determining prognosis

Prognosis of sarcoidosis varies and depends on epidemiologic factors, clinical presentation, and course, as well as specific organ involvement. Patients may develop life-threatening pulmonary, cardiac, or neurologic complications. End-stage disease may require organ transplantation for eligible patients.

Most patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis experience clinical remission with minimal residual organ impairment and a favorable long-term outcome. Advanced pulmonary disease (known as APS) occurs in a small proportion of patients with sarcoidosis but accounts for most of the poor outcomes in sarcoidosis.40 APS is variably defined, but it generally includes pulmonary fibrosis, SAPH, and respiratory infection.

One percent to 5% of patients with sarcoidosis die from complications, and mortality is higher in women and African Americans.52 Mortality and morbidity may be increasing.53 The reasons behind these trends are unclear but could include true increases in disease incidence, better detection rates, greater severity of disease, or an aging population. Increased hospitalizations and health care use might be due to organ damage from granulomatous inflammation (and resultant fibrosis), complications associated with treatment, and psychosocial effects of the disease/treatment.

Management

Management consists primarily of anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive therapies but can also include measures to address specific complications (such as fatigue) and organ transplant, as well as efforts to counter adverse medication effects. Other supportive and preventive measures may include, on a case-by-case basis, oxygen supplementation, vaccinations, or pulmonary rehabilitation. Details of these are found in other, more in-depth reviews on treatment; we will briefly review anti-inflammatory therapy, which forms the cornerstone of treatment in most patients with sarcoidosis.

Continue to: General approach to treatment decisions

General approach to treatment decisions. Anti-inflammatory therapy is used to reduce granulomatous inflammation, thereby preserving organ function and reducing symptoms. A decision to begin treatment is one shared with the patient and is based on symptoms and potential danger of organ system failure.54 Patients who are symptomatic or have progressive disease or physiologic impairment are generally candidates for treatment. Monitoring usually suffices for those who have minimal symptoms, stable disease, and preserved organ function.

Patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis at CXR stage 0 should not receive treatment, given that large, randomized trials have shown no meaningful benefit and that these patients have a high likelihood of spontaneous remission and excellent long-term prognosis.55-58 However, a subgroup of patients classified as stage 0/I on CXR may show parenchymal disease on HRCT,59 and, if more symptomatic, could be considered for treatment. For patients with stage II to IV pulmonary sarcoidosis with symptoms, there is good evidence that treatment may improve lung function and reduce dyspnea and fatigue.57,60-62

Corticosteroids are first-line treatment for most patients. Based on expert opinion, treatment of pulmonary sarcoidosis is generally started with oral prednisone (or an equivalent corticosteroid). A starting dose of 20 to 40 mg/d generally is sufficient for most patients. If the patient responds to initial treatment, prednisone dose is tapered over a period of months. If symptoms worsen during tapering, the minimum effective dose is maintained without further attempts at tapering. Treatment is continued for at least 3 to 6 months but it might be needed for longer durations; unfortunately, evidence-based guidelines are lacking.63 Once the patient goes into remission, close monitoring is done for possible relapses. Inhaled corticosteroids alone have not reduced symptoms or improved lung function in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis.64-66

Steroid-sparing agents are added for many patients. For patients receiving chronic prednisone therapy (≥ 10 mg for > 6 months), steroid-sparing agents are considered to minimize the adverse effects of steroids or to better control the inflammatory activity of sarcoidosis. These agents must be carefully selected, and clinical and laboratory monitoring need to be done throughout therapy. TABLE 558,64,67-81

The management might be complicated for extrapulmonary, multi-organ, and advanced sarcoidosis (advanced pulmonary sarcoidosis, cardiac disease, neurosarcoidosis, lupus pernio, etc) when specialized testing, as well as a combination of corticosteroids and steroid-sparing agents (with higher doses or prolonged courses), might be needed. This should be performed at an expert sarcoidosis center, ideally in a multidisciplinary setting involving pulmonologists and/or rheumatologists, chest radiologists, and specialists as indicated, based on specific organ involvement.

Continue to: Research and future directions

Research and future directions

Key goals for research are identifying more accurate biomarkers of disease, improving diagnosis of multi-organ disease, determining validated endpoints of clinical trials in sarcoidosis, and developing treatments for refractory cases.

There is optimism and opportunity in the field of sarcoidosis overall. An example of an advancement is in the area of APS, as the severity and importance of this phenotype has been better understood. Worldwide registries and trials of pulmonary vasodilator therapy (bosentan, sildenafil, epoprostenol, and inhaled iloprost) in patients with SAPH without left ventricular dysfunction are promising.82-85 However, no benefit in survival has been shown.

RioSAPH is a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of Riociguat (a stimulator of soluble guanylate cyclase) for SAPH (NCT02625558) that is closed to enrollment and undergoing data review. Similarly, results of the phase IV study of pirfenidone, an antifibrotic agent that was shown to decrease disease progression and deaths in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis,86 are awaited in the near future.

Other potential directions being explored are multicenter patient registries and randomized controlled trials, analyses of existing databases, use of biobanking, and patient-centered outcome measures. Hopefully, the care of patients with sarcoidosis will become more evidence based with ongoing and upcoming research in this field.

CORRESPONDENCE

Rohit Gupta, MBBS, FCCP, 3401 North Broad Street, 7 Parkinson Pavilion, Philadelphia, PA 19140; [email protected]

Sarcoidosis is a multisystem inflammatory disease of unclear etiology that primarily affects the lungs. It can occur at any age but usually develops before the age of 50 years, with an initial peak incidence at 20 to 29 years and a second peak incidence after 50 years of age, especially among women in Scandinavia and Japan.1 Sarcoidosis affects men and women of all racial and ethnic groups throughout the world, but differences based on race, sex, and geography are noted.1

The highest rates are reported in northern European and African-American individuals, particularly in women.1,2 The adjusted annual incidence of sarcoidosis among African Americans is approximately 3 times that among White Americans3 and is more likely to be chronic and fatal in African Americans.3 The disease can be familial with a possible recessive inheritance mode with incomplete penetrance.4 Risk of sarcoidosis in monozygotic twins appears to be 80 times greater than that in the general population, which supports genetic factors accounting for two-thirds of disease susceptibility.5

Likely factors in the development of sarcoidosis

The exact cause of sarcoidosis is unknown, but we have insights into its pathogenesis and potential triggers.1,6-9 Genes involved are being identified: class I and II human leukocyte antigen (HLA) molecules are most consistently associated with risk of sarcoidosis. Environmental exposures can activate the innate immune system and precondition a susceptible individual to react to potential causative antigens in a highly polarized, antigen-specific Th1 immune response. The epithelioid granulomatous response involves local proinflammatory cytokine production and enhanced T-cell immunity at sites of inflammation.10 Granulomas generally form to confine pathogens, restrict inflammation, and protect surrounding tissue.11-13

ACCESS (A Case Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis) identified several environmental exposures such as chemicals used in the agriculture industry, mold or mildew, and musty odors at work.14 Tobacco use was not associated with sarcoidosis.14 Recent studies have shown positive associations with service in the US Navy,15 metal working,16 firefighting,17 the handling of building supplies,18 and onsite exposure while assisting in rescue efforts at the World Trade Center disaster.19 Other data support the likelihood that specific environmental exposures associated with microbe-rich environments modestly increase the risk of sarcoidosis.14 Mycobacterial and propionibacterial DNA and RNA are potentially associated with sarcoidosis.20

Clinical manifestations are nonspecific

The diagnosis of sarcoidosis can be difficult and delayed due to diverse organ involvement and nonspecific presentations. TABLE 121-31 shows the diverse manifestations in a patient with suspected sarcoidosis. Around 50% of the patients are asymptomatic.23,24 Sarcoidosis is a diagnosis of exclusion, starting with a detailed history to rule out infections, occupational or environmental exposures, malignancies, and other possible disorders (TABLE 2).22

Diagnostic work-up

Radiologic studies

Chest x-ray (CXR) provides diagnostic and prognostic information in the evaluation of sarcoidosis using the Scadding classification system (FIGURE 1).21,25,32,33 Interobserver variability, especially between stages II and III and III and IV is the major limitation of this system.32 At presentation, radiographs are abnormal in approximately 90% of patients.34 Lymphadenopathy is the most common radiographic abnormality, occurring in more than two-thirds of cases, and pulmonary opacities (nodules and reticulation) with a middle to upper lobe predilection are present in 20% to 50% of patients.1,31,35 The nodules vary in size and can coalesce and cause alveolar collapse, thus producing consolidation.36 Linear opacities radiating laterally from the hilum into the middle and upper zones are characteristic in fibrotic disease.

Continue to: High-resoluton computed tomography

High-resolution computed tomography (HRCT). Micronodules in a perilymphatic distribution with upper lobe predominance combined with subcarinal and symmetrical hilar lymph node enlargement is practically diagnostic of sarcoidosis in the right clinical context. TABLE 321,23,25,32 and FIGURE 221,23,25,32 summarize the common CT chest findings of sarcoidosis.

Advanced imaging such as (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (PET) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are used in specialized settings for advanced pulmonary, cardiac, or neurosarcoidosis.

Tissue biopsy

Skin lesions (other than erythema nodosum), eye lesions, and peripheral lymph nodes are considered the safest extrapulmonary locations for biopsy.21,25 If pulmonary infiltrates or lymphadenopathy are present, or if extrapulmonary biopsy sites are not available, then flexible bronchoscopy with biopsy is the mainstay for tissue sampling.25

Bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL), transbronchial biopsy (TBB), endobronchial biopsy (EBB), and endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) are invaluable modalities that have reduced the need for open lung biopsy. BAL in sarcoidosis can show lymphocytosis > 15% (nonspecific) and a CD4:CD8 lymphocyte ratio > 3.5 (specificity > 90%).21,22 TBB is more sensitive than EBB; however, sensitivity overall is heightened when both of them are combined. The advent of EBUS has increased the safety and efficiency of needle aspiration of mediastinal lymph nodes. Diagnostic yield of EBUS (~80%) is superior to that with TBB and EBB (~50%), especially in stage I and II sarcoidosis.37 The combination of EBUS with TBB improves the diagnostic yield to ~90%.37

The decision to obtain biopsy samples hinges on the nature of clinical and radiologic findings (FIGURE 3).22,25,26

Continue to: Laboratory studies

Laboratory studies

Multiple abnormalities may be seen in sarcoidosis, and specific lab tests may help support a diagnosis of sarcoidosis or detect organ-specific disease activity (TABLE 4).22,23,25,38 However, no consistently accurate biomarkers exist for use in clinical practice. An angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) level greater than 2 times the upper limit of normal may be helpful; however, sensitivity remains low, and genetic polymorphisms can influence the ACE level.25 Biomarkers sometimes used to assess disease activity are serum interleukin-2 receptor, neopterin, chitotriosidase, lysozyme, KL-6 glycoprotein, and amyloid A.21

Additional tests to assess specific features or organ involvement

Pulmonary function testing (PFT) is reviewed in detail below under “pulmonary sarcoidosis.”

Electrocardiogram (EKG)/transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE). EKG abnormalities—conduction disturbances, arrhythmias, or nonspecific ST segment and T-wave changes—are the most common nonspecific findings.30 TTE findings are also nonspecific but have value in assessing cardiac chamber size and function and myocardial involvement. TTE is indeed the most common screening modality for sarcoidosis-associated pulmonary hypertension (SAPH), which is definitively diagnosed by right heart catheterization (RHC). Further evaluation for cardiac sarcoidosis can be done with cardiac MRI or fluorodeoxyglucose PET in specialized settings.

Lumbar puncture (LP) may reveal lymphocytic infiltration in suspected neurosarcoidosis, but the finding is nonspecific and can reflect infection or malignancy. Oligoclonal bands may also be seen in about one-third of neurosarcoidosis cases, and it is imperative to rule out multiple sclerosis.28

Pulmonary sarcoidosis

Pulmonary sarcoidosis accounts for most of the morbidity, mortality, and health care use associated with sarcoidosis.39,40

Continue to: Pathology of early and advanced pulmonary sarcoidosis

Pathology of early and advanced pulmonary sarcoidosis

Sarcoidosis is characterized by coalescing, tightly clustered, nonnecrotizing granulomas in the lung (FIGURE 4), most often located along the lymphatic routes of the pleura, interlobular septa, and bronchovascular bundles.41 Granulomas contain epithelioid cells or multinucleated giant cells surrounded by a chronic lymphocytic infiltrate. Typically, intracytoplasmic inclusions, such as Schaumann bodies, asteroid bodies, and blue bodies of calcium oxalates are noted within giant cells.

In chronic disease, lymphocytic infiltrate vanishes and granulomas tend to become increasingly fibrotic and enlarge to form hyalinized nodules rich with densely eosinophilic collagen. In 10% to 30% of cases, the lungs undergo progressive fibrosis.40 Nonresolving inflammation appears to be the major cause of fibrosis and the peribronchovascular localization leading to marked bronchial distortion.

Clinical features, monitoring, and outcomes

Pulmonary involvement occurs in most patients with sarcoidosis, and subclinical pulmonary disease is generally present, even when extrathoracic manifestations predominate.23 Dry cough, dyspnea, and chest discomfort are the most common symptoms. Chest auscultation is usually unremarkable. Wheezing is more common in those with fibrosis and is attributed to airway-centric fibrosis.42 There is often a substantial delay between the onset of symptoms and the diagnosis of pulmonary sarcoidosis, as symptoms are nonspecific and might be mistaken for more common pulmonary diseases, such as asthma or chronic bronchitis.43

Since sarcoidosis can affect pulmonary parenchyma, interstitium, large and small airways, pulmonary vasculature, and respiratory muscles, the pattern of lung function impairment on PFT varies from normal to obstruction, restriction, isolated diffusion defect, or a combination of these. The typical physiologic abnormality is a restrictive ventilatory defect with a decreased diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO). Extent of disease seen on HRCT correlates with level of restriction.44 Airway obstruction can be multifactorial and due to airway distortion (more likely to occur in fibrotic lung disease) and luminal disease.45-48 The 6-minute walk test and DLCO can also aid in the diagnosis of SAPH and advanced parenchymal lung disease.

While monitoring is done clinically and with testing (PFT and imaging) as needed, the optimal approach is unclear. Nevertheless, longitudinal monitoring with testing may provide useful management and prognostic information.40 Pulmonary function can remain stable in fibrotic sarcoidosis over extended periods and actually can improve in some patients.49 Serial spirometry, particularly forced vital capacity, is the most reliable tool for monitoring; when a decline in measurement occurs, chest radiography can elucidate the mechanism.50,51

Continue to: Because sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease...

Because sarcoidosis is a multisystem disease, caution needs to be exercised when evaluating a patient’s new or worsening respiratory symptoms to accurately determine the cause of symptoms and direct therapy accordingly. In addition to refractory inflammatory pulmonary disease, airway disease, infection, fibrosis, and SAPH, one needs to consider extrapulmonary involvement or complications such as cardiac or neurologic disease, musculoskeletal disease, depression, or fatigue. Adverse medication effects, deconditioning, or unrelated (or possibly related) disorders (eg pulmonary embolism) may be to blame.

Determining prognosis

Prognosis of sarcoidosis varies and depends on epidemiologic factors, clinical presentation, and course, as well as specific organ involvement. Patients may develop life-threatening pulmonary, cardiac, or neurologic complications. End-stage disease may require organ transplantation for eligible patients.

Most patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis experience clinical remission with minimal residual organ impairment and a favorable long-term outcome. Advanced pulmonary disease (known as APS) occurs in a small proportion of patients with sarcoidosis but accounts for most of the poor outcomes in sarcoidosis.40 APS is variably defined, but it generally includes pulmonary fibrosis, SAPH, and respiratory infection.

One percent to 5% of patients with sarcoidosis die from complications, and mortality is higher in women and African Americans.52 Mortality and morbidity may be increasing.53 The reasons behind these trends are unclear but could include true increases in disease incidence, better detection rates, greater severity of disease, or an aging population. Increased hospitalizations and health care use might be due to organ damage from granulomatous inflammation (and resultant fibrosis), complications associated with treatment, and psychosocial effects of the disease/treatment.

Management

Management consists primarily of anti-inflammatory or immunosuppressive therapies but can also include measures to address specific complications (such as fatigue) and organ transplant, as well as efforts to counter adverse medication effects. Other supportive and preventive measures may include, on a case-by-case basis, oxygen supplementation, vaccinations, or pulmonary rehabilitation. Details of these are found in other, more in-depth reviews on treatment; we will briefly review anti-inflammatory therapy, which forms the cornerstone of treatment in most patients with sarcoidosis.

Continue to: General approach to treatment decisions

General approach to treatment decisions. Anti-inflammatory therapy is used to reduce granulomatous inflammation, thereby preserving organ function and reducing symptoms. A decision to begin treatment is one shared with the patient and is based on symptoms and potential danger of organ system failure.54 Patients who are symptomatic or have progressive disease or physiologic impairment are generally candidates for treatment. Monitoring usually suffices for those who have minimal symptoms, stable disease, and preserved organ function.

Patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis at CXR stage 0 should not receive treatment, given that large, randomized trials have shown no meaningful benefit and that these patients have a high likelihood of spontaneous remission and excellent long-term prognosis.55-58 However, a subgroup of patients classified as stage 0/I on CXR may show parenchymal disease on HRCT,59 and, if more symptomatic, could be considered for treatment. For patients with stage II to IV pulmonary sarcoidosis with symptoms, there is good evidence that treatment may improve lung function and reduce dyspnea and fatigue.57,60-62

Corticosteroids are first-line treatment for most patients. Based on expert opinion, treatment of pulmonary sarcoidosis is generally started with oral prednisone (or an equivalent corticosteroid). A starting dose of 20 to 40 mg/d generally is sufficient for most patients. If the patient responds to initial treatment, prednisone dose is tapered over a period of months. If symptoms worsen during tapering, the minimum effective dose is maintained without further attempts at tapering. Treatment is continued for at least 3 to 6 months but it might be needed for longer durations; unfortunately, evidence-based guidelines are lacking.63 Once the patient goes into remission, close monitoring is done for possible relapses. Inhaled corticosteroids alone have not reduced symptoms or improved lung function in patients with pulmonary sarcoidosis.64-66

Steroid-sparing agents are added for many patients. For patients receiving chronic prednisone therapy (≥ 10 mg for > 6 months), steroid-sparing agents are considered to minimize the adverse effects of steroids or to better control the inflammatory activity of sarcoidosis. These agents must be carefully selected, and clinical and laboratory monitoring need to be done throughout therapy. TABLE 558,64,67-81

The management might be complicated for extrapulmonary, multi-organ, and advanced sarcoidosis (advanced pulmonary sarcoidosis, cardiac disease, neurosarcoidosis, lupus pernio, etc) when specialized testing, as well as a combination of corticosteroids and steroid-sparing agents (with higher doses or prolonged courses), might be needed. This should be performed at an expert sarcoidosis center, ideally in a multidisciplinary setting involving pulmonologists and/or rheumatologists, chest radiologists, and specialists as indicated, based on specific organ involvement.

Continue to: Research and future directions

Research and future directions

Key goals for research are identifying more accurate biomarkers of disease, improving diagnosis of multi-organ disease, determining validated endpoints of clinical trials in sarcoidosis, and developing treatments for refractory cases.

There is optimism and opportunity in the field of sarcoidosis overall. An example of an advancement is in the area of APS, as the severity and importance of this phenotype has been better understood. Worldwide registries and trials of pulmonary vasodilator therapy (bosentan, sildenafil, epoprostenol, and inhaled iloprost) in patients with SAPH without left ventricular dysfunction are promising.82-85 However, no benefit in survival has been shown.

RioSAPH is a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of Riociguat (a stimulator of soluble guanylate cyclase) for SAPH (NCT02625558) that is closed to enrollment and undergoing data review. Similarly, results of the phase IV study of pirfenidone, an antifibrotic agent that was shown to decrease disease progression and deaths in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis,86 are awaited in the near future.

Other potential directions being explored are multicenter patient registries and randomized controlled trials, analyses of existing databases, use of biobanking, and patient-centered outcome measures. Hopefully, the care of patients with sarcoidosis will become more evidence based with ongoing and upcoming research in this field.

CORRESPONDENCE

Rohit Gupta, MBBS, FCCP, 3401 North Broad Street, 7 Parkinson Pavilion, Philadelphia, PA 19140; [email protected]

1. Costabel U, Hunninghake G. ATS/ERS/WASOG statement on sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Statement Committee. American Thoracic Society. European Respiratory Society. World Association for Sarcoidosis and Other Granulomatous Disorders. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:735-737.

2. Hillerdal G, Nöu E, Osterman K, et al. Sarcoidosis: epidemiology and prognosis. A 15-year European study. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1984;130:29-32.

3. Mirsaeidi M, Machado RF, Schraufnagel D, et al. Racial difference in sarcoidosis mortality in the United States. Chest. 2015;147:438-449.

4. Rybicki BA, Iannuzzi MC, Frederick MM, et al. Familial aggregation of sarcoidosis. A case-control etiologic study of sarcoidosis (ACCESS). Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 2001;164:2085-2091.

5. Sverrild A, Backer V, Kyvik KO, et al. Heredity in sarcoidosis:a registry-based twin study. Thorax. 2008;63:894.

6. Vuyst P, Dumortier P, Schandené L, et al. Sarcoidlike lung granulomatosis induced by aluminum dusts. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1987;135:493-497.

7. Werfel U, Schneider J, Rödelsperger K, et al. Sarcoid granulomatosis after zirconium exposure with multiple organ involvement. European Respir J. 1998;12:750.

8. Newman KL, Newman LS. Occupational causes of sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;12:145-150.

9. Zissel G, Müller-Quernheim J. Specific antigen(s) in sarcoidosis:a link to autoimmunity? Eur Respir J. 2016;47:707-709.

10. Chen ES, Moller DR. Etiology of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2008;29:365-377.

11. Agostini C, Adami F, Semenzato G. New pathogenetic insights into the sarcoid granuloma. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2000;12:71-76.

12. Valentonyte R, Hampe J, Huse K, et al. Sarcoidosis is associated with a truncating splice site mutation in BTNL2. Nat Genet. 2005;37:357-364.

13. Rybicki BA, Walewski JL, Maliarik MJ, et al. The BTNL2 gene and sarcoidosis susceptibility in African Americans and Whites. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;77:491-499.

14. Newman LS, Rose CS, Bresnitz EA, et al. A case control etiologic study of sarcoidosis: environmental and occupational risk factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:1324-1330.

15. Gorham ED, Garland CF, Garland FC, et al. Trends and occupational associations in incidence of hospitalized pulmonary sarcoidosis and other lung diseases in Navy personnel: a 27-year historical prospective study, 1975-2001. Chest. 2004;126:1431-1438.

16. Kucera GP, Rybicki BA, Kirkey KL, et al. Occupational risk factors for sarcoidosis in African-American siblings. Chest. 2003;123:1527-1535.

17. Prezant DJ, Dhala A, Goldstein A, et al. The incidence, prevalence, and severity of sarcoidosis in New York City firefighters. Chest. 1999;116:1183-1193.

18. Barnard J, Rose C, Newman L, et al. Job and industry classifications associated with sarcoidosis in A Case–Control Etiologic Study of Sarcoidosis (ACCESS). J Occup Environ Med. 2005;47:226-234.

19. Izbicki G, Chavko R, Banauch GI, et al. World Trade Center “sarcoid-like” granulomatous pulmonary disease in New York City Fire Department rescue workers. Chest. 2007;131:1414-1423.

20. Eishi Y, Suga M, Ishige I, et al. Quantitative analysis of mycobacterial and propionibacterial DNA in lymph nodes of Japanese and European patients with sarcoidosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2002;40:198-204.

21. Valeyre D, Prasse A, Nunes H, et al. Sarcoidosis. Lancet. 2014;383:1155-1167.

22. Crouser ED, Maier LA, Wilson KC, et al. Diagnosis and detection of sarcoidosis. An official American Thoracic Society clinical practice guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:e26-51.

23. Judson MA, ed. Pulmonary Sarcoidosis: A Guide for the Practicing Clinician. Springer; 2014.

24. Govender P, Berman JS. The diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:585-602.

25. Valeyre D, Bernaudin J-F, Uzunhan Y, et al. Clinical presentation of sarcoidosis and diagnostic work-up. Semin Resp Crit Care Med. 2014;35:336-351.

26. Judson MA. The clinical features of sarcoidosis: a comprehensive review. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015;49:63-78.

27. Wanat KA, Rosenbach M. Cutaneous sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:685-702.

28. Culver DA, Neto ML, Moss BP, et al. Neurosarcoidosis. Semin Resp Crit Care Med. 2017;38:499-513.

29. Pasadhika S, Rosenbaum JT. Ocular sarcoidosis. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:669-683.

30. Sayah DM, Bradfield JS, Moriarty JM, et al. Cardiac involvement in sarcoidosis: evolving concepts in diagnosis and treatment. Semin Resp Crit Care Med. 2017;38:477-498.

31. Baughman RP, Teirstein AS, Judson MA, et al. Clinical characteristics of patients in a case control study of sarcoidosis. Am J Resp Crit Care. 2012;164:1885-1889.

32. Keijsers RG, Veltkamp M, Grutters JC. Chest imaging. Clin Chest Med. 2015;36:603-619.

33. Scadding J. Prognosis of intrathoracic sarcoidosis in England. A review of 136 cases after five years’ observation. Brit Med J. 1961;2:1165-1172.

34. Miller B, Putman C. The chest radiograph and sarcoidosis. Reevaluation of the chest radiograph in assessing activity of sarcoidosis: a preliminary communication. Sarcoidosis. 1985;2:85-90.

35. Loddenkemper R, Kloppenborg A, Schoenfeld N, et al. Clinical findings in 715 patients with newly detected pulmonary sarcoidosis--results of a cooperative study in former West Germany and Switzerland. WATL Study Group. Wissenschaftliche Arbeitsgemeinschaft für die Therapie von Lungenkrankheitan. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1998;15:178-182.

36. Calandriello L, Walsh SLF. Imaging for sarcoidosis. Semin Resp Crit Care Med. 2017;38:417-436.

37. Gupta D, Dadhwal DS, Agarwal R, et al. Endobronchial ultrasound-guided transbronchial needle aspiration vs conventional transbronchial needle aspiration in the diagnosis of sarcoidosis. Chest. 2014;146:547-556.

38. Baydur A. Recent developments in the physiological assessment of sarcoidosis: clinical implications. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2012;18:499-505.

39. Jamilloux Y, Maucort-Boulch D, Kerever S, et al. Sarcoidosis-related mortality in France: a multiple-cause-of-death analysis. Eur Respir J. 2016;48:1700-1709.

40. Gupta R, Baughman RP. Advanced pulmonary sarcoidosis. Semin Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;41:700-715.

41. Rossi G, Cavazza A, Colby TV. Pathology of sarcoidosis. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2015;49:36-44.

42. Hansell D, Milne D, Wilsher M, et al. Pulmonary sarcoidosis: morphologic associations of airflow obstruction at thin-section CT. Radiology. 1998;209:697-704.

43. Judson MA, Thompson BW, Rabin DL, et al. The diagnostic pathway to sarcoidosis. Chest. 2003;123:406-412.

44. Müller NL, Mawson JB, Mathieson JR, et al. Sarcoidosis: correlation of extent of disease at CT with clinical, functional, and radiographic findings. Radiology. 1989;171:613-618.

45. Harrison BDW, Shaylor JM, Stokes TC, et al. Airflow limitation in sarcoidosis—a study of pulmonary function in 107 patients with newly diagnosed disease. Resp Med. 1991;85:59-64.

46. Polychronopoulos VS, Prakash UBS. Airway Involvement in sarcoidosis. Chest. 2009;136:1371-1380.

47. Chambellan A, Turbie P, Nunes H, et al. Endoluminal stenosis of proximal bronchi in sarcoidosis: bronchoscopy, function, and evolution. Chest. 2005;127:472-481.

48. Handa T, Nagai S, Fushimi Y, et al. Clinical and radiographic indices associated with airflow limitation in patients with sarcoidosis. Chest. 2006;130:1851-1856.

49. Nardi A, Brillet P-Y, Letoumelin P, et al. Stage IV sarcoidosis: comparison of survival with the general population and causes of death. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:1368-1373.

50. Zappala CJ, Desai SR, Copley SJ, et al. Accuracy of individual variables in the monitoring of long-term change in pulmonary sarcoidosis as judged by serial high-resolution CT scan data. Chest. 2014;145:101-107.

51. Gafà G, Sverzellati N, Bonati E, et al. Follow-up in pulmonary sarcoidosis: comparison between HRCT and pulmonary function tests. Radiol Med. 2012;117:968-978.

52. Gerke AK. Morbidity and mortality in sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2014;20:472-478.

53. Kearney GD, Obi ON, Maddipati V, et al. Sarcoidosis deaths in the United States: 1999–2016. Respir Med. 2019;149:30-35.

54. Baughman RP, Judson M, Wells A. The indications for the treatment of sarcoidosis: Wells Law. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2017;34:280-282.

55. Nagai S, Shigematsu M, Hamada K, et al. Clinical courses and prognoses of pulmonary sarcoidosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 1999;5:293-298.

56. Neville E, Walker AN, James DG. Prognostic factors predicting the outcome of sarcoidosis: an analysis of 818 patients. Q J Med. 1983;52:525-533.

57. Bradley B, Branley HM, Egan JJ, et al. Interstitial lung disease guideline: the British Thoracic Society in collaboration with the Thoracic Society of Australia and the Irish Thoracic Society. Thorax. 2008;63(suppl 5):v1-v58.

58. Pietinalho A, Tukiainen P, Haahtela T, et al. Oral prednisolone followed by inhaled budesonide in newly diagnosed pulmonary sarcoidosis: a double-blind, placebo-controlled multicenter study. Finnish Pulmonary Sarcoidosis Group. Chest. 1999;116:424-431.

59. Oberstein A, von Zitzewitz H, Schweden F, et al. Non invasive evaluation of the inflammatory activity in sarcoidosis with high-resolution computed tomography. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 1997;14:65-72.

60. Gibson G, Prescott RJ, Muers MF, et al. British Thoracic Society Sarcoidosis study: effects of long term corticosteroid treatment. Thorax. 1996;51:238-247.

61. Baughman RP, Nunes H. Therapy for sarcoidosis: evidence-based recommendations. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2012;8:95-103.

62. Pietinalho A, Tukiainen P, Haahtela T, et al. Early treatment of stage II sarcoidosis improves 5-year pulmonary function. Chest. 2002;121:24-31.

63. Rahaghi FF, Baughman RP, Saketkoo LA, et al. Delphi consensus recommendations for a treatment algorithm in pulmonary sarcoidosis. Eur Respir Rev. 2020;29:190146.

64. Baughman RP, Iannuzzi MC, Lower EE, et al. Use of fluticasone in acute symptomatic pulmonary sarcoidosis. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2002;19:198-204.

65. du Bois RM, Greenhalgh PM, Southcott AM, et al. Randomized trial of inhaled fluticasone propionate in chronic stable pulmonary sarcoidosis: a pilot study. Eur Respir J. 1999;13:1345-1350.

66. Milman N, Graudal N, Grode G, Munch E. No effect of high‐dose inhaled steroids in pulmonary sarcoidosis: a double‐blind, placebo‐controlled study. J Intern Med. 1994;236:285-290.

67. Baughman RP, Winget DB, Lower EE. Methotrexate is steroid sparing in acute sarcoidosis: results of a double blind, randomized trial. Sarcoidosis Vasc Diffuse Lung Dis. 2000;17:60-66.

68. Vorselaars ADM, Wuyts WA, Vorselaars VMM, et al. Methotrexate vs azathioprine in second-line therapy of sarcoidosis. Chest. 2013;144:805-812.

69. Sahoo D, Bandyopadhyay D, Xu M, et al. Effectiveness and safety of leflunomide for pulmonary and extrapulmonary sarcoidosis. Eur Respir J. 2011;38:1145-1150.