User login

Postdeployment Respiratory Health: The Roles of the Airborne Hazards and Open Burn Pit Registry and the Post-Deployment Cardiopulmonary Evaluation Network

Case Example

A 37-year-old female never smoker presents to your clinic with progressive dyspnea over the past 15 years. She reports dyspnea on exertion, wheezing, chronic nasal congestion, and difficulty sleeping that started a year after she returned from military deployment to Iraq. She has been unable to exercise, even at low intensity, for the past 5 years, despite being previously active. She has experienced some symptom improvement by taking an albuterol inhaler as needed, loratadine (10 mg), and fluticasone nasal spray (50 mcg). She occasionally uses famotidine for reflux (40 mg). She deployed to Southwest Asia for 12 months (2002-2003) and was primarily stationed in Qayyarah West, an Air Force base in the Mosul district in northern Iraq. She reports exposure during deployment to the fire in the Al-Mishraq sulfur mine, located approximately 25 km north of Qayyarah West, as well as dust storms and burn pits. She currently works as a medical assistant. Her examination is remarkable for normal bronchovesicular breath sounds without any wheezing or crackles on pulmonary evaluation. Her body mass index is 31. You obtain a chest radiograph and spirometry, which are both normal.

The veteran reports feeling frustrated as she has had multiple specialty evaluations in community clinics without receiving a diagnosis, despite worsening symptoms. She reports that she added her information to the Airborne Hazards and Open Burn Pit Registry (AHOBPR). She recently received a letter from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Post-Deployment Cardiopulmonary Evaluation Network (PDCEN) and is asking you whether she should participate in the PDCEN specialty evaluation. You are not familiar with the military experiences she has described or the programs she asks you about; however, you would like to know more to best care for your patient.

Background

The year 2021 marked the 20th anniversary of the September 11 attacks and the launch of the Global War on Terrorism. Almost 3 million US military personnel have been deployed in support of these operations along with about 300,000 US civilian contractors and thousands of troops from more than 40 nations.1-3

Respiratory hazards associated with deployment to Southwest Asia and Afghanistan are unique and varied. These exposures include blast injuries and a variety of particulate matter sources, such as burn pit combustion byproducts, aeroallergens, and dust storms.7,8,15,16 One air sampling study conducted at 15 deployment sites in Southwest Asia and Afghanistan found mean fine particulate matter (PM2.5) levels were as much as 10 times greater than sampling sites in both rural and urban cities in the United States; all sites sampled exceeded military exposure guidelines (65 µg/m3 for 1 year).17,18 Long-term exposure to PM2.5 has been associated with the development of chronic respiratory and cardiovascular disease; therefore, there has been considerable attention to the respiratory (and nonrespiratory) health of deployed military personnel.19

Concerns regarding the association between deployment and lung disease led to the creation of the national VA Airborne Hazards and Open Burn Pit Registry (AHOBPR) in 2014 and consists of (1) an online questionnaire to document deployment and medical history, exposure concerns, and symptoms; and (2) an optional in-person or virtual clinical health evaluation at the individual’s local VA medical center or military treatment facility (MTF). As of March 2022, more than 300,000 individuals have completed the online questionnaire of which about 30% declined the optional clinical health evaluation.

The clinical evaluation available to AHOBPR participants has not yet been described in the literature. Therefore, our objectives are to examine AHOBPR clinical evaluation data and review its application throughout the VA. In addition, we will also describe a parallel effort by the VA PDCEN, which is to provide comprehensive multiday clinical evaluations for unique AHOBPR participants with unexplained dyspnea and self-reported respiratory disease. A secondary aim of this publication is to disseminate information to health care professionals (HCPs) within and outside of the VA to aid in the referral and evaluation of previously deployed veterans who experience unexplained dyspnea.

AHOBPR Overview

The AHOBPR is an online questionnaire and optional in-person health evaluation that includes 7 major categories targeting deployment history, symptoms, medical history, health concerns, residential history, nonmilitary occupational history, nonmilitary environmental exposures, and health care utilization. The VA Defense Information Repository is used to obtain service dates for the service member/veteran, conflict involvement, and primary location during deployment. The questionnaire portion of the AHOBPR is administered online. It currently is open to all veterans who served in the Southwest Asia theater of operations (including Iraq, Kuwait, and Egypt) any time after August 2, 1990, or Afghanistan, Djibouti, Syria, or Uzbekistan after September 11, 2001. Veterans are eligible for completing the AHOBPR and optional health evaluation at no cost to the veteran regardless of VA benefits or whether they are currently enrolled in VA health care. Though the focus of the present manuscript is to profile a VA program, it is important to note that the US Department of Defense (DoD) is an active partner with the VA in the promotion of the AHOBPR to service members and similarly provides health evaluations for active-duty service members (including activating Reserve and Guard) through their local MTF.

We reviewed and analyzed AHOBPR operations and VA data from 2014 to 2020. Our analyses were limited to veterans seeking evaluation as well as their corresponding symptoms and HCP’s clinical impression from the electronic health record. As of September 20, 2021, 267,125 individuals completed the AHOBPR. The mean age was 43 years (range, 19-84), and the majority were male (86%) and served in the Army (58%). Open-air burn pits (91%), engine maintenance (38.8%), and convoy operations (71.7%) were the most common deployment-related exposures.

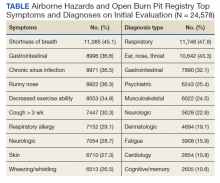

The optional in-person AHOBPR health evaluation may be requested by the veteran after completing the online questionnaire and is performed at the veteran’s local VA facility. The evaluation is most often completed by an environmental health clinician or primary care practitioner (PCP). A variety of resources are available to providers for training on this topic, including fact sheets, webinars, monthly calls, conferences, and accredited e-learning.20 As part of the clinical evaluation, the veteran’s chief concerns are assessed and evaluated. At the time of our analysis, 24,578 clinical examinations were performed across 126 VA medical facilities, with considerable geographic variation. Veterans receiving evaluations were predominantly male (89%) with a median age of 46.0 years (IQR, 15). Veterans’ major respiratory concerns included dyspnea (45.1%), decreased exercise ability (34.8%), and cough > 3 weeks (30.3%) (Table). After clinical evaluation by a VA or MTF HCP, 47.8% were found to have a respiratory diagnosis, including asthma (30.1%), COPD (12.8%), and bronchitis (11.9%).

Registry participants who opt to receive the clinical evaluation may benefit directly by undergoing a detailed clinical history and physical examination as well as having the opportunity to document their health concerns. For some, clinicians may need to refer veterans for additional specialty testing beyond this standard AHOBPR clinical evaluation. Although these evaluations can help address some of the veterans’ concerns, a substantial number may have unexplained respiratory symptoms that warrant further investigation.

Post-Deployment Cardiopulmonary Evaluation Network Clinical Evaluation

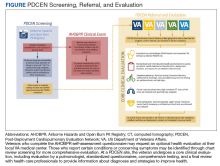

In May 2019, the VA established the Airborne Hazards and Burn Pits Center of Excellence (AHBPCE). One of the AHBPCE’s objectives is to deliver specialized care and consultation for veterans with concerns about their postdeployment health, including, but not limited to, unexplained dyspnea. To meet this objective, the AHBPCE developed the PDCEN, a national network consisting of specialty HCPs from 5 VA medical centers—located in San Francisco, California; Denver, Colorado; Baltimore, Maryland; Ann Arbor, Michigan; and East Orange, New Jersey. Collectively, the PDCEN has developed a standardized approach for the comprehensive clinical evaluation of unexplained dyspnea that is implemented uniformly across sites. Staff at the PDCEN screen the AHOBPR to identify veterans with features of respiratory disease and invite them to participate in an in-person evaluation at the nearest PDCEN site. Given the specialty expertise (detailed below) within the Network, the PDCEN focuses on complex cases that are resource intensive. To address complex cases of unexplained dyspnea, the PDCEN has developed a core clinical evaluation approach (Figure).

The first step in a veteran’s PDCEN evaluation entails a set of detailed questionnaires that request information about the veteran’s current respiratory, sleep, and mental health symptoms and any associated medical diagnoses. Questionnaires also identify potential exposures to military burn pits, sulfur mine and oil field fires, diesel exhaust fumes, dust storms, urban pollution, explosions/blasts, and chemical weapons. In addition, the questionnaires include deployment geographic location, which may inform future estimates of particulate matter exposure.21 Prior VA and non-VA evaluations and testing of their respiratory concerns are obtained for review. Exposure and health records from the DoD are also reviewed when available.

The next step in the PDCEN evaluation comprises comprehensive testing, including complete pulmonary function testing, methacholine challenge, cardiopulmonary exercise testing, forced oscillometry and exhaled nitric oxide testing, paired high-resolution inspiratory and expiratory chest computed tomography (CT) imaging, sinus CT imaging, direct flexible laryngoscopy, echocardiography, polysomnography, and laboratory blood testing. The testing process is managed by local site coordinators and varies by institution based on availability of each testing modality and subspecialist appointments.

Once testing is completed, the veteran is evaluated by a team of HCPs, including physicians from the disciplines of pulmonary medicine, environmental and occupational health, sleep medicine, otolaryngology and speech pathology, and mental health (when appropriate). After the clinical evaluation has been completed, this team of expert HCPs at each site convenes to provide a final summary review visit intended to be a comprehensive assessment of the veteran’s primary health concerns. The 3 primary objectives of this final review are to inform the veteran of (1) what respiratory and related conditions they have; (2) whether the conditions is/are deployment related; and (3) what treatments and/or follow-up care may enhance their current state of health in partnership with their local HCPs. The PDCEN does not provide ongoing management of any conditions identified during the veteran’s evaluation but communicates findings and recommendations to the veteran and their PCP for long-term care.

Discussion

The AHOBPR was established in response to mounting concerns that service members and veterans were experiencing adverse health effects that might be attributable to deployment-related exposures. Nearly half of all patients currently enrolled in the AHOBPR report dyspnea, and about one-third have decreased exercise tolerance and/or cough. Of those who completed the questionnaire and the subsequent in-person and generalized AHOBPR examination, our interim analysis showed that about half were assigned a respiratory diagnosis. Yet for many veterans, their breathing symptoms remained unexplained or did not respond to treatment.

While the AHOBPR and related examinations address the needs of many veterans, others may require more comprehensive examination. The PDCEN attends to the latter by providing more detailed and comprehensive clinical evaluations of veterans with deployment-related respiratory health concerns and seeks to learn from these evaluations by analyzing data obtained from veterans across sites. As such, the PDCEN hopes not only to improve the health of individual veterans, but also create standard practices for both VA and non-VA community evaluation of veterans exposed to respiratory hazards during deployment.

One of the major challenges in the field of postdeployment respiratory health is the lack of clear universal language or case definitions that encompass the veteran’s clinical concerns. In an influential case series published in 2011, 38 (77%) of 49 soldiers with history of airborne hazard exposure and unexplained exercise intolerance were reported to have histopathology consistent with constrictive bronchiolitis on surgical lung biopsy.14 Subsequent publications have described other histopathologic features in deployed military personnel, including granulomatous inflammation, interstitial lung disease, emphysema, and pleuritis.12-14 Reconciling these findings from surgical lung biopsy with the clinical presentation and noninvasive studies has proved difficult. Therefore, several groups of investigators have proposed terms, including postdeployment respiratory syndrome, deployment-related distal lung disease, and Iraq/Afghanistan War lung injury to describe the increased respiratory symptoms and variety of histopathologic and imaging findings in this population.9,12,22 At present, there remains a lack of consensus on terminology and case definitions as well as the role of military environmental exposures in exacerbating and/or causing these conditions. As HCPs, it is important to appreciate and acknowledge that the ambiguity and controversy pertaining to terminology, causation, and service connections are a common source of frustration experienced by veterans, which are increasingly reflected among reports in popular media and lay press.

A second and related challenge in the field of postdeployment respiratory health that contributes to veteran and HCP frustration is that many of the aforementioned abnormalities described on surgical lung biopsy are not readily identifiable on noninvasive tests, including traditional interpretation of pulmonary function tests or chest CT imaging.12-14,22 Thus, underlying conditions could be overlooked and veterans’ concerns and symptoms may be dismissed or misattributed to other comorbid conditions. While surgical lung biopsies may offer diagnostic clarity in identifying lung disease, there are significant procedural risks of surgical and anesthetic complications. Furthermore, a definitive diagnosis does not necessarily guarantee a clear treatment plan. For example, there are no current therapies approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of constrictive bronchiolitis.

Research efforts are underway, including within the PDCEN, to evaluate a more sensitive and noninvasive assessment of the small airways that may even reduce or eliminate the need for surgical lung biopsy. In contrast to traditional pulmonary function testing, which is helpful for evaluation of the larger airways, forced oscillation technique can be used noninvasively, using pressure oscillations to evaluate for diseases of the smaller airways and has been used in the veteran population and in those exposed to dust from the World Trade Center disaster.23-25 Multiple breath washout technique provides a lung clearance index that is determined by the number of lung turnovers it takes to clear the lungs of an inert gas (eg, sulfur hexafluoride, nitrogen). Elevated lung clearance index values suggest ventilation heterogeneity and have been shown to be higher among deployed veterans with dyspnea.26,27 Finally, advanced CT analytic techniques may help identify functional small airways disease and are higher in deployed service members with constrictive bronchiolitis on surgical lung biopsy.28 These innovative noninvasive techniques are experimental but promising, especially as part of a broader evaluation of small airways disease.

AHOBPR clinical evaluations represent an initial step to better understand postdeployment health conditions available to all AHOBPR participants. The PDCEN clinical evaluation extends the AHOBPR evaluation by providing specialty care for certain veterans requiring more comprehensive evaluation while systematically collecting and analyzing clinical data to advance the field. The VA is committed to leveraging these data and all available expertise to provide a clear description of the spectrum of disease in this population and improve our ability to diagnose, follow, and treat respiratory health conditions occurring after deployment to Southwest Asia and Afghanistan.

Case Conclusion

The veteran was referred to a PDCEN site and underwent a comprehensive multidisciplinary evaluation. Pulmonary function testing showed lung volumes and vital capacity within the predicted normal range, mild air trapping, and a low diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide. Methacholine challenge testing was normal; however, forced oscillometry suggested small airways obstruction. A high-resolution CT showed air trapping without parenchymal changes. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing demonstrated a peak exercise capacity within the predicted normal range but low breathing reserve. Otolaryngology evaluation including laryngoscopy suggested chronic nonallergic rhinitis.

At the end of the veteran’s evaluation, a summary review reported nonallergic rhinitis and distal airway obstruction consistent with small airways disease. Both were reported as most likely related to deployment given her significant environmental exposures and the temporal relationship with her deployment and symptom onset as well as lack of other identifiable causes. A more precise histopathologic diagnosis could be firmly established with a surgical lung biopsy, but after shared decision making with a PDCEN HCP, the patient declined to undergo this invasive procedure. After you review the summary review and recommendations from the PDCEN group, you start the veteran on intranasal steroids and a combined inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting β agonist inhaler as well as refer the veteran to pulmonary rehabilitation. After several weeks, she reports an improvement in sleep and nasal symptoms but continues to experience residual exercise intolerance.

This case serves as an example of the significant limitations that a previously active and healthy patient can develop after deployment to Southwest Asia and Afghanistan. Encouraging this veteran to complete the AHOBPR allowed her to be considered for a PDCEN evaluation that provided the opportunity to undergo a comprehensive noninvasive evaluation of her chronic dyspnea. In doing so, she obtained 2 important diagnoses and data from her evaluation will help establish best practices for standardized evaluations of respiratory concerns following deployment. Through the AHOBPR and PDCEN, the VA seeks to better understand postdeployment health conditions, their relationship to military and environmental exposures, and how best to diagnose and treat these conditions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Airborne Hazards and Burn Pits Center of Excellence (Public Law 115-929). The authors acknowledge support and contributions from Dr. Eric Shuping and leadership at VA’s Health Outcomes Military Exposures office as well as the New Jersey War Related Illness and Injury Study Center. In addition, we thank Erin McRoberts and Rajeev Swarup for their contributions to the Post-Deployment Cardiopulmonary Evaluation Network. Post-Deployment Cardiopulmonary Evaluation Network members:

Mehrdad Arjomandi, Caroline Davis, Michelle DeLuca, Nancy Eager, Courtney A. Eberhardt, Michael J. Falvo, Timothy Foley, Fiona A.S. Graff, Deborah Heaney, Stella E. Hines, Rachel E. Howard, Nisha Jani, Sheena Kamineni, Silpa Krefft, Mary L. Langlois, Helen Lozier, Simran K. Matharu, Anisa Moore, Lydia Patrick-DeLuca, Edward Pickering, Alexander Rabin, Michelle Robertson, Samantha L. Rogers, Aaron H. Schneider, Anand Shah, Anays Sotolongo, Jennifer H. Therkorn, Rebecca I. Toczylowski, Matthew Watson, Alison D. Wilczynski, Ian W. Wilson, Romi A. Yount.

1. Wenger J, O’Connell C, Cottrell L. Examination of recent deployment experience across the services and components. Exam. RAND Corporation; 2018. Accessed June 27, 2022. doi:10.7249/rr1928

2. Torreon BS. U.S. periods of war and dates of recent conflicts, RS21405. Congressional Research Service; 2017. June 5, 2020. Accessed June 27, 2022. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/details?prodcode=RS21405

3. Dunigan M, Farmer CM, Burns RM, Hawks A, Setodji CM. Out of the shadows: the health and well-being of private contractors working in conflict environments. RAND Corporation; 2013. Accessed June 27, 2022. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR420.html

4. Szema AM, Peters MC, Weissinger KM, Gagliano CA, Chen JJ. New-onset asthma among soldiers serving in Iraq and Afghanistan. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31(5):67-71. doi:10.2500/aap.2010.31.3383

5. Pugh MJ, Jaramillo CA, Leung KW, et al. Increasing prevalence of chronic lung disease in veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Mil Med. 2016;181(5):476-481. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00035

6. Falvo MJ, Osinubi OY, Sotolongo AM, Helmer DA. Airborne hazards exposure and respiratory health of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Epidemiol Rev. 2015;37:116-130. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxu009

7. McAndrew LM, Teichman RF, Osinubi OY, Jasien JV, Quigley KS. Environmental exposure and health of Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54(6):665-669. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e318255ba1b

8. Smith B, Wong CA, Smith TC, Boyko EJ, Gackstetter GD; Margaret A. K. Ryan for the Millennium Cohort Study Team. Newly reported respiratory symptoms and conditions among military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: a prospective population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(11):1433-1442. doi:10.1093/aje/kwp287

9. Szema AM, Salihi W, Savary K, Chen JJ. Respiratory symptoms necessitating spirometry among soldiers with Iraq/Afghanistan war lung injury. J Occup Environ Med. 2011;53(9):961-965. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e31822c9f05

10. Committee on the Long-Term Health Consequences of Exposure to Burn Pits in Iraq and Afghanistan; Institute of Medicine. Long-Term Health Consequences of Exposure to Burn Pits in Iraq and Afghanistan. The National Academies Press; 2011. Accessed June 27, 2022. doi:10.17226/1320911. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Respiratory Health Effects of Airborne Hazards Exposures in the Southwest Asia Theater of Military Operations. The National Academies Press; 2020. Accessed June 27, 2022. doi:10.17226/25837

12. Krefft SD, Wolff J, Zell-Baran L, et al. Respiratory diseases in post-9/11 military personnel following Southwest Asia deployment. J Occup Environ Med. 2020;62(5):337-343. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001817

13. Gordetsky J, Kim C, Miller RF, Mehrad M. Non-necrotizing granulomatous pneumonitis and chronic pleuritis in soldiers deployed to Southwest Asia. Histopathology. 2020;77(3):453-459. doi:10.1111/his.14135

14. King MS, Eisenberg R, Newman JH, et al. Constrictive bronchiolitis in soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(3):222-230. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1101388

15. Helmer DA, Rossignol M, Blatt M, Agarwal R, Teichman R, Lange G. Health and exposure concerns of veterans deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49(5):475-480. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e318042d682

16. Kim YH, Warren SH, Kooter I, et al. Chemistry, lung toxicity and mutagenicity of burn pit smoke-related particulate matter. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2021;18(1):45. Published 2021 Dec 16. doi:10.1186/s12989-021-00435-w

17. Engelbrecht JP, McDonald EV, Gillies JA, Jayanty RK, Casuccio G, Gertler AW. Characterizing mineral dusts and other aerosols from the Middle East—Part 1: ambient sampling. Inhal Toxicol. 2009;21(4):297-326. doi:10.1080/08958370802464273

18. US Army Public Health Command. Technical guide 230: environmental health risk assessment and chemical exposure guidelines for deployed military personnel, 2013 revision. Accessed June 27, 2022. https://phc.amedd.army.mil/PHC%20Resource%20Library/TG230-DeploymentEHRA-and-MEGs-2013-Revision.pdf

19. Anderson JO, Thundiyil JG, Stolbach A. Clearing the air: a review of the effects of particulate matter air pollution on human health. J Med Toxicol. 2012;8(2):166-175. doi:10.1007/s13181-011-0203-1

20. Shuping E, Schneiderman A. Resources on environmental exposures for military veterans. Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(12):709-710.

21. Masri S, Garshick E, Coull BA, Koutrakis P. A novel calibration approach using satellite and visibility observations to estimate fine particulate matter exposures in Southwest Asia and Afghanistan. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2017;67(1):86-95. doi:10.1080/10962247.2016.1230079

22. Gutor SS, Richmond BW, Du RH, et al. Postdeployment respiratory syndrome in soldiers with chronic exertional dyspnea. Am J Surg Pathol. 2021;45(12):1587-1596. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000001757

23. Goldman MD, Saadeh C, Ross D. Clinical applications of forced oscillation to assess peripheral airway function. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2005;148(1-2):179-194. doi:10.1016/j.resp.2005.05.026

24. Butzko RP, Sotolongo AM, Helmer DA, et al. Forced oscillation technique in veterans with preserved spirometry and chronic respiratory symptoms. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2019;260:8-16. doi:10.1016/j.resp.2018.11.012

25. Oppenheimer BW, Goldring RM, Herberg ME, et al. Distal airway function in symptomatic subjects with normal spirometry following World Trade Center dust exposure. Chest. 2007;132(4):1275-1282. doi:10.1378/chest.07-0913

26. Zell-Baran LM, Krefft SD, Moore CM, Wolff J, Meehan R, Rose CS. Multiple breath washout: a noninvasive tool for identifying lung disease in symptomatic military deployers. Respir Med. 2021;176:106281. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106281

27. Krefft SD, Strand M, Smith J, Stroup C, Meehan R, Rose C. Utility of lung clearance index testing as a noninvasive marker of deployment-related lung disease. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(8):707-711. doi:10.1097/JOM.000000000000105828. Davis CW, Lopez CL, Bell AJ, et al. The severity of functional small airways disease in military personnel with constrictive bronchiolitis as measured by quantitative CT [published online ahead of print, 2022 May 24]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;10.1164/rccm.202201-0153LE. doi:10.1164/rccm.202201-0153LE

Case Example

A 37-year-old female never smoker presents to your clinic with progressive dyspnea over the past 15 years. She reports dyspnea on exertion, wheezing, chronic nasal congestion, and difficulty sleeping that started a year after she returned from military deployment to Iraq. She has been unable to exercise, even at low intensity, for the past 5 years, despite being previously active. She has experienced some symptom improvement by taking an albuterol inhaler as needed, loratadine (10 mg), and fluticasone nasal spray (50 mcg). She occasionally uses famotidine for reflux (40 mg). She deployed to Southwest Asia for 12 months (2002-2003) and was primarily stationed in Qayyarah West, an Air Force base in the Mosul district in northern Iraq. She reports exposure during deployment to the fire in the Al-Mishraq sulfur mine, located approximately 25 km north of Qayyarah West, as well as dust storms and burn pits. She currently works as a medical assistant. Her examination is remarkable for normal bronchovesicular breath sounds without any wheezing or crackles on pulmonary evaluation. Her body mass index is 31. You obtain a chest radiograph and spirometry, which are both normal.

The veteran reports feeling frustrated as she has had multiple specialty evaluations in community clinics without receiving a diagnosis, despite worsening symptoms. She reports that she added her information to the Airborne Hazards and Open Burn Pit Registry (AHOBPR). She recently received a letter from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Post-Deployment Cardiopulmonary Evaluation Network (PDCEN) and is asking you whether she should participate in the PDCEN specialty evaluation. You are not familiar with the military experiences she has described or the programs she asks you about; however, you would like to know more to best care for your patient.

Background

The year 2021 marked the 20th anniversary of the September 11 attacks and the launch of the Global War on Terrorism. Almost 3 million US military personnel have been deployed in support of these operations along with about 300,000 US civilian contractors and thousands of troops from more than 40 nations.1-3

Respiratory hazards associated with deployment to Southwest Asia and Afghanistan are unique and varied. These exposures include blast injuries and a variety of particulate matter sources, such as burn pit combustion byproducts, aeroallergens, and dust storms.7,8,15,16 One air sampling study conducted at 15 deployment sites in Southwest Asia and Afghanistan found mean fine particulate matter (PM2.5) levels were as much as 10 times greater than sampling sites in both rural and urban cities in the United States; all sites sampled exceeded military exposure guidelines (65 µg/m3 for 1 year).17,18 Long-term exposure to PM2.5 has been associated with the development of chronic respiratory and cardiovascular disease; therefore, there has been considerable attention to the respiratory (and nonrespiratory) health of deployed military personnel.19

Concerns regarding the association between deployment and lung disease led to the creation of the national VA Airborne Hazards and Open Burn Pit Registry (AHOBPR) in 2014 and consists of (1) an online questionnaire to document deployment and medical history, exposure concerns, and symptoms; and (2) an optional in-person or virtual clinical health evaluation at the individual’s local VA medical center or military treatment facility (MTF). As of March 2022, more than 300,000 individuals have completed the online questionnaire of which about 30% declined the optional clinical health evaluation.

The clinical evaluation available to AHOBPR participants has not yet been described in the literature. Therefore, our objectives are to examine AHOBPR clinical evaluation data and review its application throughout the VA. In addition, we will also describe a parallel effort by the VA PDCEN, which is to provide comprehensive multiday clinical evaluations for unique AHOBPR participants with unexplained dyspnea and self-reported respiratory disease. A secondary aim of this publication is to disseminate information to health care professionals (HCPs) within and outside of the VA to aid in the referral and evaluation of previously deployed veterans who experience unexplained dyspnea.

AHOBPR Overview

The AHOBPR is an online questionnaire and optional in-person health evaluation that includes 7 major categories targeting deployment history, symptoms, medical history, health concerns, residential history, nonmilitary occupational history, nonmilitary environmental exposures, and health care utilization. The VA Defense Information Repository is used to obtain service dates for the service member/veteran, conflict involvement, and primary location during deployment. The questionnaire portion of the AHOBPR is administered online. It currently is open to all veterans who served in the Southwest Asia theater of operations (including Iraq, Kuwait, and Egypt) any time after August 2, 1990, or Afghanistan, Djibouti, Syria, or Uzbekistan after September 11, 2001. Veterans are eligible for completing the AHOBPR and optional health evaluation at no cost to the veteran regardless of VA benefits or whether they are currently enrolled in VA health care. Though the focus of the present manuscript is to profile a VA program, it is important to note that the US Department of Defense (DoD) is an active partner with the VA in the promotion of the AHOBPR to service members and similarly provides health evaluations for active-duty service members (including activating Reserve and Guard) through their local MTF.

We reviewed and analyzed AHOBPR operations and VA data from 2014 to 2020. Our analyses were limited to veterans seeking evaluation as well as their corresponding symptoms and HCP’s clinical impression from the electronic health record. As of September 20, 2021, 267,125 individuals completed the AHOBPR. The mean age was 43 years (range, 19-84), and the majority were male (86%) and served in the Army (58%). Open-air burn pits (91%), engine maintenance (38.8%), and convoy operations (71.7%) were the most common deployment-related exposures.

The optional in-person AHOBPR health evaluation may be requested by the veteran after completing the online questionnaire and is performed at the veteran’s local VA facility. The evaluation is most often completed by an environmental health clinician or primary care practitioner (PCP). A variety of resources are available to providers for training on this topic, including fact sheets, webinars, monthly calls, conferences, and accredited e-learning.20 As part of the clinical evaluation, the veteran’s chief concerns are assessed and evaluated. At the time of our analysis, 24,578 clinical examinations were performed across 126 VA medical facilities, with considerable geographic variation. Veterans receiving evaluations were predominantly male (89%) with a median age of 46.0 years (IQR, 15). Veterans’ major respiratory concerns included dyspnea (45.1%), decreased exercise ability (34.8%), and cough > 3 weeks (30.3%) (Table). After clinical evaluation by a VA or MTF HCP, 47.8% were found to have a respiratory diagnosis, including asthma (30.1%), COPD (12.8%), and bronchitis (11.9%).

Registry participants who opt to receive the clinical evaluation may benefit directly by undergoing a detailed clinical history and physical examination as well as having the opportunity to document their health concerns. For some, clinicians may need to refer veterans for additional specialty testing beyond this standard AHOBPR clinical evaluation. Although these evaluations can help address some of the veterans’ concerns, a substantial number may have unexplained respiratory symptoms that warrant further investigation.

Post-Deployment Cardiopulmonary Evaluation Network Clinical Evaluation

In May 2019, the VA established the Airborne Hazards and Burn Pits Center of Excellence (AHBPCE). One of the AHBPCE’s objectives is to deliver specialized care and consultation for veterans with concerns about their postdeployment health, including, but not limited to, unexplained dyspnea. To meet this objective, the AHBPCE developed the PDCEN, a national network consisting of specialty HCPs from 5 VA medical centers—located in San Francisco, California; Denver, Colorado; Baltimore, Maryland; Ann Arbor, Michigan; and East Orange, New Jersey. Collectively, the PDCEN has developed a standardized approach for the comprehensive clinical evaluation of unexplained dyspnea that is implemented uniformly across sites. Staff at the PDCEN screen the AHOBPR to identify veterans with features of respiratory disease and invite them to participate in an in-person evaluation at the nearest PDCEN site. Given the specialty expertise (detailed below) within the Network, the PDCEN focuses on complex cases that are resource intensive. To address complex cases of unexplained dyspnea, the PDCEN has developed a core clinical evaluation approach (Figure).

The first step in a veteran’s PDCEN evaluation entails a set of detailed questionnaires that request information about the veteran’s current respiratory, sleep, and mental health symptoms and any associated medical diagnoses. Questionnaires also identify potential exposures to military burn pits, sulfur mine and oil field fires, diesel exhaust fumes, dust storms, urban pollution, explosions/blasts, and chemical weapons. In addition, the questionnaires include deployment geographic location, which may inform future estimates of particulate matter exposure.21 Prior VA and non-VA evaluations and testing of their respiratory concerns are obtained for review. Exposure and health records from the DoD are also reviewed when available.

The next step in the PDCEN evaluation comprises comprehensive testing, including complete pulmonary function testing, methacholine challenge, cardiopulmonary exercise testing, forced oscillometry and exhaled nitric oxide testing, paired high-resolution inspiratory and expiratory chest computed tomography (CT) imaging, sinus CT imaging, direct flexible laryngoscopy, echocardiography, polysomnography, and laboratory blood testing. The testing process is managed by local site coordinators and varies by institution based on availability of each testing modality and subspecialist appointments.

Once testing is completed, the veteran is evaluated by a team of HCPs, including physicians from the disciplines of pulmonary medicine, environmental and occupational health, sleep medicine, otolaryngology and speech pathology, and mental health (when appropriate). After the clinical evaluation has been completed, this team of expert HCPs at each site convenes to provide a final summary review visit intended to be a comprehensive assessment of the veteran’s primary health concerns. The 3 primary objectives of this final review are to inform the veteran of (1) what respiratory and related conditions they have; (2) whether the conditions is/are deployment related; and (3) what treatments and/or follow-up care may enhance their current state of health in partnership with their local HCPs. The PDCEN does not provide ongoing management of any conditions identified during the veteran’s evaluation but communicates findings and recommendations to the veteran and their PCP for long-term care.

Discussion

The AHOBPR was established in response to mounting concerns that service members and veterans were experiencing adverse health effects that might be attributable to deployment-related exposures. Nearly half of all patients currently enrolled in the AHOBPR report dyspnea, and about one-third have decreased exercise tolerance and/or cough. Of those who completed the questionnaire and the subsequent in-person and generalized AHOBPR examination, our interim analysis showed that about half were assigned a respiratory diagnosis. Yet for many veterans, their breathing symptoms remained unexplained or did not respond to treatment.

While the AHOBPR and related examinations address the needs of many veterans, others may require more comprehensive examination. The PDCEN attends to the latter by providing more detailed and comprehensive clinical evaluations of veterans with deployment-related respiratory health concerns and seeks to learn from these evaluations by analyzing data obtained from veterans across sites. As such, the PDCEN hopes not only to improve the health of individual veterans, but also create standard practices for both VA and non-VA community evaluation of veterans exposed to respiratory hazards during deployment.

One of the major challenges in the field of postdeployment respiratory health is the lack of clear universal language or case definitions that encompass the veteran’s clinical concerns. In an influential case series published in 2011, 38 (77%) of 49 soldiers with history of airborne hazard exposure and unexplained exercise intolerance were reported to have histopathology consistent with constrictive bronchiolitis on surgical lung biopsy.14 Subsequent publications have described other histopathologic features in deployed military personnel, including granulomatous inflammation, interstitial lung disease, emphysema, and pleuritis.12-14 Reconciling these findings from surgical lung biopsy with the clinical presentation and noninvasive studies has proved difficult. Therefore, several groups of investigators have proposed terms, including postdeployment respiratory syndrome, deployment-related distal lung disease, and Iraq/Afghanistan War lung injury to describe the increased respiratory symptoms and variety of histopathologic and imaging findings in this population.9,12,22 At present, there remains a lack of consensus on terminology and case definitions as well as the role of military environmental exposures in exacerbating and/or causing these conditions. As HCPs, it is important to appreciate and acknowledge that the ambiguity and controversy pertaining to terminology, causation, and service connections are a common source of frustration experienced by veterans, which are increasingly reflected among reports in popular media and lay press.

A second and related challenge in the field of postdeployment respiratory health that contributes to veteran and HCP frustration is that many of the aforementioned abnormalities described on surgical lung biopsy are not readily identifiable on noninvasive tests, including traditional interpretation of pulmonary function tests or chest CT imaging.12-14,22 Thus, underlying conditions could be overlooked and veterans’ concerns and symptoms may be dismissed or misattributed to other comorbid conditions. While surgical lung biopsies may offer diagnostic clarity in identifying lung disease, there are significant procedural risks of surgical and anesthetic complications. Furthermore, a definitive diagnosis does not necessarily guarantee a clear treatment plan. For example, there are no current therapies approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of constrictive bronchiolitis.

Research efforts are underway, including within the PDCEN, to evaluate a more sensitive and noninvasive assessment of the small airways that may even reduce or eliminate the need for surgical lung biopsy. In contrast to traditional pulmonary function testing, which is helpful for evaluation of the larger airways, forced oscillation technique can be used noninvasively, using pressure oscillations to evaluate for diseases of the smaller airways and has been used in the veteran population and in those exposed to dust from the World Trade Center disaster.23-25 Multiple breath washout technique provides a lung clearance index that is determined by the number of lung turnovers it takes to clear the lungs of an inert gas (eg, sulfur hexafluoride, nitrogen). Elevated lung clearance index values suggest ventilation heterogeneity and have been shown to be higher among deployed veterans with dyspnea.26,27 Finally, advanced CT analytic techniques may help identify functional small airways disease and are higher in deployed service members with constrictive bronchiolitis on surgical lung biopsy.28 These innovative noninvasive techniques are experimental but promising, especially as part of a broader evaluation of small airways disease.

AHOBPR clinical evaluations represent an initial step to better understand postdeployment health conditions available to all AHOBPR participants. The PDCEN clinical evaluation extends the AHOBPR evaluation by providing specialty care for certain veterans requiring more comprehensive evaluation while systematically collecting and analyzing clinical data to advance the field. The VA is committed to leveraging these data and all available expertise to provide a clear description of the spectrum of disease in this population and improve our ability to diagnose, follow, and treat respiratory health conditions occurring after deployment to Southwest Asia and Afghanistan.

Case Conclusion

The veteran was referred to a PDCEN site and underwent a comprehensive multidisciplinary evaluation. Pulmonary function testing showed lung volumes and vital capacity within the predicted normal range, mild air trapping, and a low diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide. Methacholine challenge testing was normal; however, forced oscillometry suggested small airways obstruction. A high-resolution CT showed air trapping without parenchymal changes. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing demonstrated a peak exercise capacity within the predicted normal range but low breathing reserve. Otolaryngology evaluation including laryngoscopy suggested chronic nonallergic rhinitis.

At the end of the veteran’s evaluation, a summary review reported nonallergic rhinitis and distal airway obstruction consistent with small airways disease. Both were reported as most likely related to deployment given her significant environmental exposures and the temporal relationship with her deployment and symptom onset as well as lack of other identifiable causes. A more precise histopathologic diagnosis could be firmly established with a surgical lung biopsy, but after shared decision making with a PDCEN HCP, the patient declined to undergo this invasive procedure. After you review the summary review and recommendations from the PDCEN group, you start the veteran on intranasal steroids and a combined inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting β agonist inhaler as well as refer the veteran to pulmonary rehabilitation. After several weeks, she reports an improvement in sleep and nasal symptoms but continues to experience residual exercise intolerance.

This case serves as an example of the significant limitations that a previously active and healthy patient can develop after deployment to Southwest Asia and Afghanistan. Encouraging this veteran to complete the AHOBPR allowed her to be considered for a PDCEN evaluation that provided the opportunity to undergo a comprehensive noninvasive evaluation of her chronic dyspnea. In doing so, she obtained 2 important diagnoses and data from her evaluation will help establish best practices for standardized evaluations of respiratory concerns following deployment. Through the AHOBPR and PDCEN, the VA seeks to better understand postdeployment health conditions, their relationship to military and environmental exposures, and how best to diagnose and treat these conditions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Airborne Hazards and Burn Pits Center of Excellence (Public Law 115-929). The authors acknowledge support and contributions from Dr. Eric Shuping and leadership at VA’s Health Outcomes Military Exposures office as well as the New Jersey War Related Illness and Injury Study Center. In addition, we thank Erin McRoberts and Rajeev Swarup for their contributions to the Post-Deployment Cardiopulmonary Evaluation Network. Post-Deployment Cardiopulmonary Evaluation Network members:

Mehrdad Arjomandi, Caroline Davis, Michelle DeLuca, Nancy Eager, Courtney A. Eberhardt, Michael J. Falvo, Timothy Foley, Fiona A.S. Graff, Deborah Heaney, Stella E. Hines, Rachel E. Howard, Nisha Jani, Sheena Kamineni, Silpa Krefft, Mary L. Langlois, Helen Lozier, Simran K. Matharu, Anisa Moore, Lydia Patrick-DeLuca, Edward Pickering, Alexander Rabin, Michelle Robertson, Samantha L. Rogers, Aaron H. Schneider, Anand Shah, Anays Sotolongo, Jennifer H. Therkorn, Rebecca I. Toczylowski, Matthew Watson, Alison D. Wilczynski, Ian W. Wilson, Romi A. Yount.

Case Example

A 37-year-old female never smoker presents to your clinic with progressive dyspnea over the past 15 years. She reports dyspnea on exertion, wheezing, chronic nasal congestion, and difficulty sleeping that started a year after she returned from military deployment to Iraq. She has been unable to exercise, even at low intensity, for the past 5 years, despite being previously active. She has experienced some symptom improvement by taking an albuterol inhaler as needed, loratadine (10 mg), and fluticasone nasal spray (50 mcg). She occasionally uses famotidine for reflux (40 mg). She deployed to Southwest Asia for 12 months (2002-2003) and was primarily stationed in Qayyarah West, an Air Force base in the Mosul district in northern Iraq. She reports exposure during deployment to the fire in the Al-Mishraq sulfur mine, located approximately 25 km north of Qayyarah West, as well as dust storms and burn pits. She currently works as a medical assistant. Her examination is remarkable for normal bronchovesicular breath sounds without any wheezing or crackles on pulmonary evaluation. Her body mass index is 31. You obtain a chest radiograph and spirometry, which are both normal.

The veteran reports feeling frustrated as she has had multiple specialty evaluations in community clinics without receiving a diagnosis, despite worsening symptoms. She reports that she added her information to the Airborne Hazards and Open Burn Pit Registry (AHOBPR). She recently received a letter from the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Post-Deployment Cardiopulmonary Evaluation Network (PDCEN) and is asking you whether she should participate in the PDCEN specialty evaluation. You are not familiar with the military experiences she has described or the programs she asks you about; however, you would like to know more to best care for your patient.

Background

The year 2021 marked the 20th anniversary of the September 11 attacks and the launch of the Global War on Terrorism. Almost 3 million US military personnel have been deployed in support of these operations along with about 300,000 US civilian contractors and thousands of troops from more than 40 nations.1-3

Respiratory hazards associated with deployment to Southwest Asia and Afghanistan are unique and varied. These exposures include blast injuries and a variety of particulate matter sources, such as burn pit combustion byproducts, aeroallergens, and dust storms.7,8,15,16 One air sampling study conducted at 15 deployment sites in Southwest Asia and Afghanistan found mean fine particulate matter (PM2.5) levels were as much as 10 times greater than sampling sites in both rural and urban cities in the United States; all sites sampled exceeded military exposure guidelines (65 µg/m3 for 1 year).17,18 Long-term exposure to PM2.5 has been associated with the development of chronic respiratory and cardiovascular disease; therefore, there has been considerable attention to the respiratory (and nonrespiratory) health of deployed military personnel.19

Concerns regarding the association between deployment and lung disease led to the creation of the national VA Airborne Hazards and Open Burn Pit Registry (AHOBPR) in 2014 and consists of (1) an online questionnaire to document deployment and medical history, exposure concerns, and symptoms; and (2) an optional in-person or virtual clinical health evaluation at the individual’s local VA medical center or military treatment facility (MTF). As of March 2022, more than 300,000 individuals have completed the online questionnaire of which about 30% declined the optional clinical health evaluation.

The clinical evaluation available to AHOBPR participants has not yet been described in the literature. Therefore, our objectives are to examine AHOBPR clinical evaluation data and review its application throughout the VA. In addition, we will also describe a parallel effort by the VA PDCEN, which is to provide comprehensive multiday clinical evaluations for unique AHOBPR participants with unexplained dyspnea and self-reported respiratory disease. A secondary aim of this publication is to disseminate information to health care professionals (HCPs) within and outside of the VA to aid in the referral and evaluation of previously deployed veterans who experience unexplained dyspnea.

AHOBPR Overview

The AHOBPR is an online questionnaire and optional in-person health evaluation that includes 7 major categories targeting deployment history, symptoms, medical history, health concerns, residential history, nonmilitary occupational history, nonmilitary environmental exposures, and health care utilization. The VA Defense Information Repository is used to obtain service dates for the service member/veteran, conflict involvement, and primary location during deployment. The questionnaire portion of the AHOBPR is administered online. It currently is open to all veterans who served in the Southwest Asia theater of operations (including Iraq, Kuwait, and Egypt) any time after August 2, 1990, or Afghanistan, Djibouti, Syria, or Uzbekistan after September 11, 2001. Veterans are eligible for completing the AHOBPR and optional health evaluation at no cost to the veteran regardless of VA benefits or whether they are currently enrolled in VA health care. Though the focus of the present manuscript is to profile a VA program, it is important to note that the US Department of Defense (DoD) is an active partner with the VA in the promotion of the AHOBPR to service members and similarly provides health evaluations for active-duty service members (including activating Reserve and Guard) through their local MTF.

We reviewed and analyzed AHOBPR operations and VA data from 2014 to 2020. Our analyses were limited to veterans seeking evaluation as well as their corresponding symptoms and HCP’s clinical impression from the electronic health record. As of September 20, 2021, 267,125 individuals completed the AHOBPR. The mean age was 43 years (range, 19-84), and the majority were male (86%) and served in the Army (58%). Open-air burn pits (91%), engine maintenance (38.8%), and convoy operations (71.7%) were the most common deployment-related exposures.

The optional in-person AHOBPR health evaluation may be requested by the veteran after completing the online questionnaire and is performed at the veteran’s local VA facility. The evaluation is most often completed by an environmental health clinician or primary care practitioner (PCP). A variety of resources are available to providers for training on this topic, including fact sheets, webinars, monthly calls, conferences, and accredited e-learning.20 As part of the clinical evaluation, the veteran’s chief concerns are assessed and evaluated. At the time of our analysis, 24,578 clinical examinations were performed across 126 VA medical facilities, with considerable geographic variation. Veterans receiving evaluations were predominantly male (89%) with a median age of 46.0 years (IQR, 15). Veterans’ major respiratory concerns included dyspnea (45.1%), decreased exercise ability (34.8%), and cough > 3 weeks (30.3%) (Table). After clinical evaluation by a VA or MTF HCP, 47.8% were found to have a respiratory diagnosis, including asthma (30.1%), COPD (12.8%), and bronchitis (11.9%).

Registry participants who opt to receive the clinical evaluation may benefit directly by undergoing a detailed clinical history and physical examination as well as having the opportunity to document their health concerns. For some, clinicians may need to refer veterans for additional specialty testing beyond this standard AHOBPR clinical evaluation. Although these evaluations can help address some of the veterans’ concerns, a substantial number may have unexplained respiratory symptoms that warrant further investigation.

Post-Deployment Cardiopulmonary Evaluation Network Clinical Evaluation

In May 2019, the VA established the Airborne Hazards and Burn Pits Center of Excellence (AHBPCE). One of the AHBPCE’s objectives is to deliver specialized care and consultation for veterans with concerns about their postdeployment health, including, but not limited to, unexplained dyspnea. To meet this objective, the AHBPCE developed the PDCEN, a national network consisting of specialty HCPs from 5 VA medical centers—located in San Francisco, California; Denver, Colorado; Baltimore, Maryland; Ann Arbor, Michigan; and East Orange, New Jersey. Collectively, the PDCEN has developed a standardized approach for the comprehensive clinical evaluation of unexplained dyspnea that is implemented uniformly across sites. Staff at the PDCEN screen the AHOBPR to identify veterans with features of respiratory disease and invite them to participate in an in-person evaluation at the nearest PDCEN site. Given the specialty expertise (detailed below) within the Network, the PDCEN focuses on complex cases that are resource intensive. To address complex cases of unexplained dyspnea, the PDCEN has developed a core clinical evaluation approach (Figure).

The first step in a veteran’s PDCEN evaluation entails a set of detailed questionnaires that request information about the veteran’s current respiratory, sleep, and mental health symptoms and any associated medical diagnoses. Questionnaires also identify potential exposures to military burn pits, sulfur mine and oil field fires, diesel exhaust fumes, dust storms, urban pollution, explosions/blasts, and chemical weapons. In addition, the questionnaires include deployment geographic location, which may inform future estimates of particulate matter exposure.21 Prior VA and non-VA evaluations and testing of their respiratory concerns are obtained for review. Exposure and health records from the DoD are also reviewed when available.

The next step in the PDCEN evaluation comprises comprehensive testing, including complete pulmonary function testing, methacholine challenge, cardiopulmonary exercise testing, forced oscillometry and exhaled nitric oxide testing, paired high-resolution inspiratory and expiratory chest computed tomography (CT) imaging, sinus CT imaging, direct flexible laryngoscopy, echocardiography, polysomnography, and laboratory blood testing. The testing process is managed by local site coordinators and varies by institution based on availability of each testing modality and subspecialist appointments.

Once testing is completed, the veteran is evaluated by a team of HCPs, including physicians from the disciplines of pulmonary medicine, environmental and occupational health, sleep medicine, otolaryngology and speech pathology, and mental health (when appropriate). After the clinical evaluation has been completed, this team of expert HCPs at each site convenes to provide a final summary review visit intended to be a comprehensive assessment of the veteran’s primary health concerns. The 3 primary objectives of this final review are to inform the veteran of (1) what respiratory and related conditions they have; (2) whether the conditions is/are deployment related; and (3) what treatments and/or follow-up care may enhance their current state of health in partnership with their local HCPs. The PDCEN does not provide ongoing management of any conditions identified during the veteran’s evaluation but communicates findings and recommendations to the veteran and their PCP for long-term care.

Discussion

The AHOBPR was established in response to mounting concerns that service members and veterans were experiencing adverse health effects that might be attributable to deployment-related exposures. Nearly half of all patients currently enrolled in the AHOBPR report dyspnea, and about one-third have decreased exercise tolerance and/or cough. Of those who completed the questionnaire and the subsequent in-person and generalized AHOBPR examination, our interim analysis showed that about half were assigned a respiratory diagnosis. Yet for many veterans, their breathing symptoms remained unexplained or did not respond to treatment.

While the AHOBPR and related examinations address the needs of many veterans, others may require more comprehensive examination. The PDCEN attends to the latter by providing more detailed and comprehensive clinical evaluations of veterans with deployment-related respiratory health concerns and seeks to learn from these evaluations by analyzing data obtained from veterans across sites. As such, the PDCEN hopes not only to improve the health of individual veterans, but also create standard practices for both VA and non-VA community evaluation of veterans exposed to respiratory hazards during deployment.

One of the major challenges in the field of postdeployment respiratory health is the lack of clear universal language or case definitions that encompass the veteran’s clinical concerns. In an influential case series published in 2011, 38 (77%) of 49 soldiers with history of airborne hazard exposure and unexplained exercise intolerance were reported to have histopathology consistent with constrictive bronchiolitis on surgical lung biopsy.14 Subsequent publications have described other histopathologic features in deployed military personnel, including granulomatous inflammation, interstitial lung disease, emphysema, and pleuritis.12-14 Reconciling these findings from surgical lung biopsy with the clinical presentation and noninvasive studies has proved difficult. Therefore, several groups of investigators have proposed terms, including postdeployment respiratory syndrome, deployment-related distal lung disease, and Iraq/Afghanistan War lung injury to describe the increased respiratory symptoms and variety of histopathologic and imaging findings in this population.9,12,22 At present, there remains a lack of consensus on terminology and case definitions as well as the role of military environmental exposures in exacerbating and/or causing these conditions. As HCPs, it is important to appreciate and acknowledge that the ambiguity and controversy pertaining to terminology, causation, and service connections are a common source of frustration experienced by veterans, which are increasingly reflected among reports in popular media and lay press.

A second and related challenge in the field of postdeployment respiratory health that contributes to veteran and HCP frustration is that many of the aforementioned abnormalities described on surgical lung biopsy are not readily identifiable on noninvasive tests, including traditional interpretation of pulmonary function tests or chest CT imaging.12-14,22 Thus, underlying conditions could be overlooked and veterans’ concerns and symptoms may be dismissed or misattributed to other comorbid conditions. While surgical lung biopsies may offer diagnostic clarity in identifying lung disease, there are significant procedural risks of surgical and anesthetic complications. Furthermore, a definitive diagnosis does not necessarily guarantee a clear treatment plan. For example, there are no current therapies approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of constrictive bronchiolitis.

Research efforts are underway, including within the PDCEN, to evaluate a more sensitive and noninvasive assessment of the small airways that may even reduce or eliminate the need for surgical lung biopsy. In contrast to traditional pulmonary function testing, which is helpful for evaluation of the larger airways, forced oscillation technique can be used noninvasively, using pressure oscillations to evaluate for diseases of the smaller airways and has been used in the veteran population and in those exposed to dust from the World Trade Center disaster.23-25 Multiple breath washout technique provides a lung clearance index that is determined by the number of lung turnovers it takes to clear the lungs of an inert gas (eg, sulfur hexafluoride, nitrogen). Elevated lung clearance index values suggest ventilation heterogeneity and have been shown to be higher among deployed veterans with dyspnea.26,27 Finally, advanced CT analytic techniques may help identify functional small airways disease and are higher in deployed service members with constrictive bronchiolitis on surgical lung biopsy.28 These innovative noninvasive techniques are experimental but promising, especially as part of a broader evaluation of small airways disease.

AHOBPR clinical evaluations represent an initial step to better understand postdeployment health conditions available to all AHOBPR participants. The PDCEN clinical evaluation extends the AHOBPR evaluation by providing specialty care for certain veterans requiring more comprehensive evaluation while systematically collecting and analyzing clinical data to advance the field. The VA is committed to leveraging these data and all available expertise to provide a clear description of the spectrum of disease in this population and improve our ability to diagnose, follow, and treat respiratory health conditions occurring after deployment to Southwest Asia and Afghanistan.

Case Conclusion

The veteran was referred to a PDCEN site and underwent a comprehensive multidisciplinary evaluation. Pulmonary function testing showed lung volumes and vital capacity within the predicted normal range, mild air trapping, and a low diffusion capacity for carbon monoxide. Methacholine challenge testing was normal; however, forced oscillometry suggested small airways obstruction. A high-resolution CT showed air trapping without parenchymal changes. Cardiopulmonary exercise testing demonstrated a peak exercise capacity within the predicted normal range but low breathing reserve. Otolaryngology evaluation including laryngoscopy suggested chronic nonallergic rhinitis.

At the end of the veteran’s evaluation, a summary review reported nonallergic rhinitis and distal airway obstruction consistent with small airways disease. Both were reported as most likely related to deployment given her significant environmental exposures and the temporal relationship with her deployment and symptom onset as well as lack of other identifiable causes. A more precise histopathologic diagnosis could be firmly established with a surgical lung biopsy, but after shared decision making with a PDCEN HCP, the patient declined to undergo this invasive procedure. After you review the summary review and recommendations from the PDCEN group, you start the veteran on intranasal steroids and a combined inhaled corticosteroid/long-acting β agonist inhaler as well as refer the veteran to pulmonary rehabilitation. After several weeks, she reports an improvement in sleep and nasal symptoms but continues to experience residual exercise intolerance.

This case serves as an example of the significant limitations that a previously active and healthy patient can develop after deployment to Southwest Asia and Afghanistan. Encouraging this veteran to complete the AHOBPR allowed her to be considered for a PDCEN evaluation that provided the opportunity to undergo a comprehensive noninvasive evaluation of her chronic dyspnea. In doing so, she obtained 2 important diagnoses and data from her evaluation will help establish best practices for standardized evaluations of respiratory concerns following deployment. Through the AHOBPR and PDCEN, the VA seeks to better understand postdeployment health conditions, their relationship to military and environmental exposures, and how best to diagnose and treat these conditions.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) Airborne Hazards and Burn Pits Center of Excellence (Public Law 115-929). The authors acknowledge support and contributions from Dr. Eric Shuping and leadership at VA’s Health Outcomes Military Exposures office as well as the New Jersey War Related Illness and Injury Study Center. In addition, we thank Erin McRoberts and Rajeev Swarup for their contributions to the Post-Deployment Cardiopulmonary Evaluation Network. Post-Deployment Cardiopulmonary Evaluation Network members:

Mehrdad Arjomandi, Caroline Davis, Michelle DeLuca, Nancy Eager, Courtney A. Eberhardt, Michael J. Falvo, Timothy Foley, Fiona A.S. Graff, Deborah Heaney, Stella E. Hines, Rachel E. Howard, Nisha Jani, Sheena Kamineni, Silpa Krefft, Mary L. Langlois, Helen Lozier, Simran K. Matharu, Anisa Moore, Lydia Patrick-DeLuca, Edward Pickering, Alexander Rabin, Michelle Robertson, Samantha L. Rogers, Aaron H. Schneider, Anand Shah, Anays Sotolongo, Jennifer H. Therkorn, Rebecca I. Toczylowski, Matthew Watson, Alison D. Wilczynski, Ian W. Wilson, Romi A. Yount.

1. Wenger J, O’Connell C, Cottrell L. Examination of recent deployment experience across the services and components. Exam. RAND Corporation; 2018. Accessed June 27, 2022. doi:10.7249/rr1928

2. Torreon BS. U.S. periods of war and dates of recent conflicts, RS21405. Congressional Research Service; 2017. June 5, 2020. Accessed June 27, 2022. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/details?prodcode=RS21405

3. Dunigan M, Farmer CM, Burns RM, Hawks A, Setodji CM. Out of the shadows: the health and well-being of private contractors working in conflict environments. RAND Corporation; 2013. Accessed June 27, 2022. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR420.html

4. Szema AM, Peters MC, Weissinger KM, Gagliano CA, Chen JJ. New-onset asthma among soldiers serving in Iraq and Afghanistan. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31(5):67-71. doi:10.2500/aap.2010.31.3383

5. Pugh MJ, Jaramillo CA, Leung KW, et al. Increasing prevalence of chronic lung disease in veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Mil Med. 2016;181(5):476-481. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00035

6. Falvo MJ, Osinubi OY, Sotolongo AM, Helmer DA. Airborne hazards exposure and respiratory health of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Epidemiol Rev. 2015;37:116-130. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxu009

7. McAndrew LM, Teichman RF, Osinubi OY, Jasien JV, Quigley KS. Environmental exposure and health of Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54(6):665-669. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e318255ba1b

8. Smith B, Wong CA, Smith TC, Boyko EJ, Gackstetter GD; Margaret A. K. Ryan for the Millennium Cohort Study Team. Newly reported respiratory symptoms and conditions among military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: a prospective population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(11):1433-1442. doi:10.1093/aje/kwp287

9. Szema AM, Salihi W, Savary K, Chen JJ. Respiratory symptoms necessitating spirometry among soldiers with Iraq/Afghanistan war lung injury. J Occup Environ Med. 2011;53(9):961-965. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e31822c9f05

10. Committee on the Long-Term Health Consequences of Exposure to Burn Pits in Iraq and Afghanistan; Institute of Medicine. Long-Term Health Consequences of Exposure to Burn Pits in Iraq and Afghanistan. The National Academies Press; 2011. Accessed June 27, 2022. doi:10.17226/1320911. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Respiratory Health Effects of Airborne Hazards Exposures in the Southwest Asia Theater of Military Operations. The National Academies Press; 2020. Accessed June 27, 2022. doi:10.17226/25837

12. Krefft SD, Wolff J, Zell-Baran L, et al. Respiratory diseases in post-9/11 military personnel following Southwest Asia deployment. J Occup Environ Med. 2020;62(5):337-343. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001817

13. Gordetsky J, Kim C, Miller RF, Mehrad M. Non-necrotizing granulomatous pneumonitis and chronic pleuritis in soldiers deployed to Southwest Asia. Histopathology. 2020;77(3):453-459. doi:10.1111/his.14135

14. King MS, Eisenberg R, Newman JH, et al. Constrictive bronchiolitis in soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(3):222-230. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1101388

15. Helmer DA, Rossignol M, Blatt M, Agarwal R, Teichman R, Lange G. Health and exposure concerns of veterans deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49(5):475-480. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e318042d682

16. Kim YH, Warren SH, Kooter I, et al. Chemistry, lung toxicity and mutagenicity of burn pit smoke-related particulate matter. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2021;18(1):45. Published 2021 Dec 16. doi:10.1186/s12989-021-00435-w

17. Engelbrecht JP, McDonald EV, Gillies JA, Jayanty RK, Casuccio G, Gertler AW. Characterizing mineral dusts and other aerosols from the Middle East—Part 1: ambient sampling. Inhal Toxicol. 2009;21(4):297-326. doi:10.1080/08958370802464273

18. US Army Public Health Command. Technical guide 230: environmental health risk assessment and chemical exposure guidelines for deployed military personnel, 2013 revision. Accessed June 27, 2022. https://phc.amedd.army.mil/PHC%20Resource%20Library/TG230-DeploymentEHRA-and-MEGs-2013-Revision.pdf

19. Anderson JO, Thundiyil JG, Stolbach A. Clearing the air: a review of the effects of particulate matter air pollution on human health. J Med Toxicol. 2012;8(2):166-175. doi:10.1007/s13181-011-0203-1

20. Shuping E, Schneiderman A. Resources on environmental exposures for military veterans. Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(12):709-710.

21. Masri S, Garshick E, Coull BA, Koutrakis P. A novel calibration approach using satellite and visibility observations to estimate fine particulate matter exposures in Southwest Asia and Afghanistan. J Air Waste Manag Assoc. 2017;67(1):86-95. doi:10.1080/10962247.2016.1230079

22. Gutor SS, Richmond BW, Du RH, et al. Postdeployment respiratory syndrome in soldiers with chronic exertional dyspnea. Am J Surg Pathol. 2021;45(12):1587-1596. doi:10.1097/PAS.0000000000001757

23. Goldman MD, Saadeh C, Ross D. Clinical applications of forced oscillation to assess peripheral airway function. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2005;148(1-2):179-194. doi:10.1016/j.resp.2005.05.026

24. Butzko RP, Sotolongo AM, Helmer DA, et al. Forced oscillation technique in veterans with preserved spirometry and chronic respiratory symptoms. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2019;260:8-16. doi:10.1016/j.resp.2018.11.012

25. Oppenheimer BW, Goldring RM, Herberg ME, et al. Distal airway function in symptomatic subjects with normal spirometry following World Trade Center dust exposure. Chest. 2007;132(4):1275-1282. doi:10.1378/chest.07-0913

26. Zell-Baran LM, Krefft SD, Moore CM, Wolff J, Meehan R, Rose CS. Multiple breath washout: a noninvasive tool for identifying lung disease in symptomatic military deployers. Respir Med. 2021;176:106281. doi:10.1016/j.rmed.2020.106281

27. Krefft SD, Strand M, Smith J, Stroup C, Meehan R, Rose C. Utility of lung clearance index testing as a noninvasive marker of deployment-related lung disease. J Occup Environ Med. 2017;59(8):707-711. doi:10.1097/JOM.000000000000105828. Davis CW, Lopez CL, Bell AJ, et al. The severity of functional small airways disease in military personnel with constrictive bronchiolitis as measured by quantitative CT [published online ahead of print, 2022 May 24]. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022;10.1164/rccm.202201-0153LE. doi:10.1164/rccm.202201-0153LE

1. Wenger J, O’Connell C, Cottrell L. Examination of recent deployment experience across the services and components. Exam. RAND Corporation; 2018. Accessed June 27, 2022. doi:10.7249/rr1928

2. Torreon BS. U.S. periods of war and dates of recent conflicts, RS21405. Congressional Research Service; 2017. June 5, 2020. Accessed June 27, 2022. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/details?prodcode=RS21405

3. Dunigan M, Farmer CM, Burns RM, Hawks A, Setodji CM. Out of the shadows: the health and well-being of private contractors working in conflict environments. RAND Corporation; 2013. Accessed June 27, 2022. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR420.html

4. Szema AM, Peters MC, Weissinger KM, Gagliano CA, Chen JJ. New-onset asthma among soldiers serving in Iraq and Afghanistan. Allergy Asthma Proc. 2010;31(5):67-71. doi:10.2500/aap.2010.31.3383

5. Pugh MJ, Jaramillo CA, Leung KW, et al. Increasing prevalence of chronic lung disease in veterans of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. Mil Med. 2016;181(5):476-481. doi:10.7205/MILMED-D-15-00035

6. Falvo MJ, Osinubi OY, Sotolongo AM, Helmer DA. Airborne hazards exposure and respiratory health of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans. Epidemiol Rev. 2015;37:116-130. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxu009

7. McAndrew LM, Teichman RF, Osinubi OY, Jasien JV, Quigley KS. Environmental exposure and health of Operation Enduring Freedom/Operation Iraqi Freedom veterans. J Occup Environ Med. 2012;54(6):665-669. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e318255ba1b

8. Smith B, Wong CA, Smith TC, Boyko EJ, Gackstetter GD; Margaret A. K. Ryan for the Millennium Cohort Study Team. Newly reported respiratory symptoms and conditions among military personnel deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan: a prospective population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;170(11):1433-1442. doi:10.1093/aje/kwp287

9. Szema AM, Salihi W, Savary K, Chen JJ. Respiratory symptoms necessitating spirometry among soldiers with Iraq/Afghanistan war lung injury. J Occup Environ Med. 2011;53(9):961-965. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e31822c9f05

10. Committee on the Long-Term Health Consequences of Exposure to Burn Pits in Iraq and Afghanistan; Institute of Medicine. Long-Term Health Consequences of Exposure to Burn Pits in Iraq and Afghanistan. The National Academies Press; 2011. Accessed June 27, 2022. doi:10.17226/1320911. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Respiratory Health Effects of Airborne Hazards Exposures in the Southwest Asia Theater of Military Operations. The National Academies Press; 2020. Accessed June 27, 2022. doi:10.17226/25837

12. Krefft SD, Wolff J, Zell-Baran L, et al. Respiratory diseases in post-9/11 military personnel following Southwest Asia deployment. J Occup Environ Med. 2020;62(5):337-343. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000001817

13. Gordetsky J, Kim C, Miller RF, Mehrad M. Non-necrotizing granulomatous pneumonitis and chronic pleuritis in soldiers deployed to Southwest Asia. Histopathology. 2020;77(3):453-459. doi:10.1111/his.14135

14. King MS, Eisenberg R, Newman JH, et al. Constrictive bronchiolitis in soldiers returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(3):222-230. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1101388

15. Helmer DA, Rossignol M, Blatt M, Agarwal R, Teichman R, Lange G. Health and exposure concerns of veterans deployed to Iraq and Afghanistan. J Occup Environ Med. 2007;49(5):475-480. doi:10.1097/JOM.0b013e318042d682

16. Kim YH, Warren SH, Kooter I, et al. Chemistry, lung toxicity and mutagenicity of burn pit smoke-related particulate matter. Part Fibre Toxicol. 2021;18(1):45. Published 2021 Dec 16. doi:10.1186/s12989-021-00435-w

17. Engelbrecht JP, McDonald EV, Gillies JA, Jayanty RK, Casuccio G, Gertler AW. Characterizing mineral dusts and other aerosols from the Middle East—Part 1: ambient sampling. Inhal Toxicol. 2009;21(4):297-326. doi:10.1080/08958370802464273

18. US Army Public Health Command. Technical guide 230: environmental health risk assessment and chemical exposure guidelines for deployed military personnel, 2013 revision. Accessed June 27, 2022. https://phc.amedd.army.mil/PHC%20Resource%20Library/TG230-DeploymentEHRA-and-MEGs-2013-Revision.pdf

19. Anderson JO, Thundiyil JG, Stolbach A. Clearing the air: a review of the effects of particulate matter air pollution on human health. J Med Toxicol. 2012;8(2):166-175. doi:10.1007/s13181-011-0203-1

20. Shuping E, Schneiderman A. Resources on environmental exposures for military veterans. Am Fam Physician. 2020;101(12):709-710.