User login

37-year-old man • cough • increasing shortness of breath • pleuritic chest pain • Dx?

THE CASE

A 37-year-old man with a history of asthma, schizoaffective disorder, and tobacco use (36 packs per year) presented to the clinic after 5 days of worsening cough, reproducible left-sided chest pain, and increasing shortness of breath. He also experienced chills, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting but was afebrile. The patient had not travelled recently nor had direct contact with anyone sick. He also denied intravenous (IV) drug use, alcohol use, and bloody sputum. Recently, he had intentionally lost weight, as recommended by his psychiatrist.

Medication review revealed that he was taking many central-acting agents for schizoaffective disorder, including alprazolam, aripiprazole, desvenlafaxine, and quetiapine. Due to his intermittent asthma since childhood, he used an albuterol inhaler as needed, which currently offered only minimal relief. He denied any history of hospitalization or intubation for asthma.

During the clinic visit, his blood pressure was 90/60 mm Hg and his heart rate was normal. His pulse oximetry was 92% on room air. On physical examination, he had normal-appearing dentition. Auscultation revealed bilateral expiratory wheezes with decreased breath sounds at the left lower lobe.

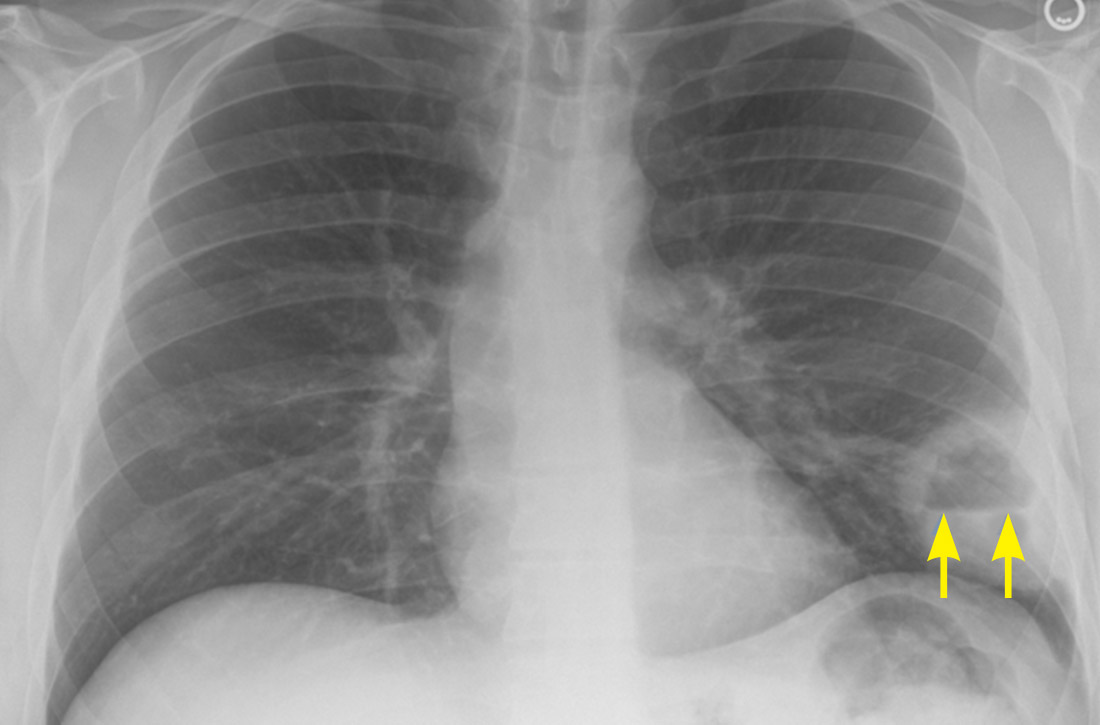

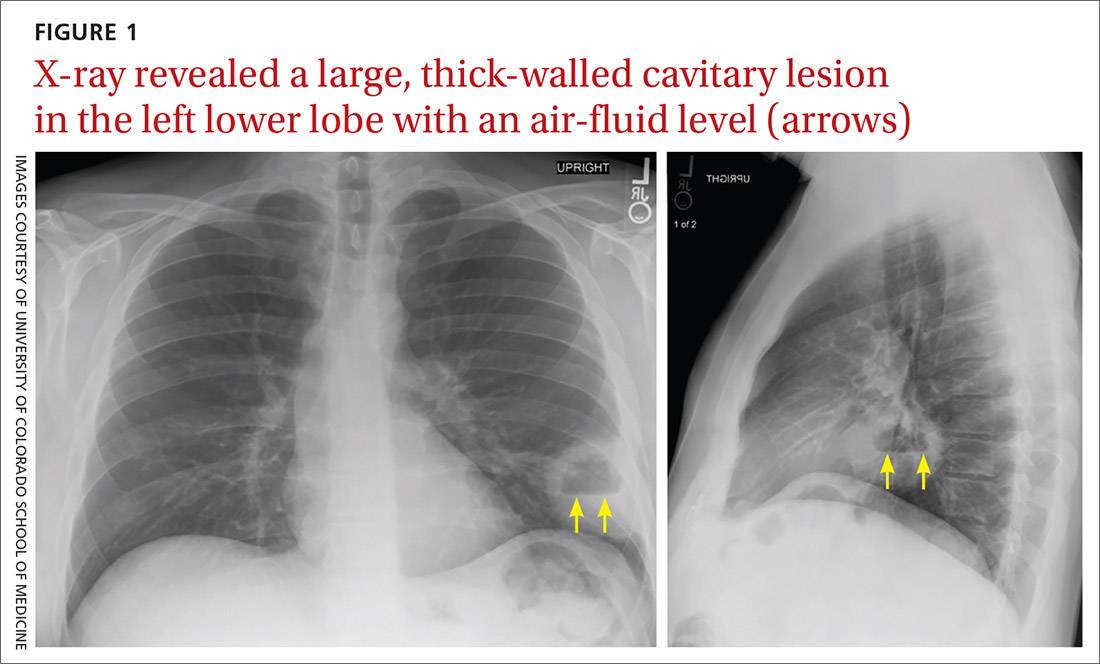

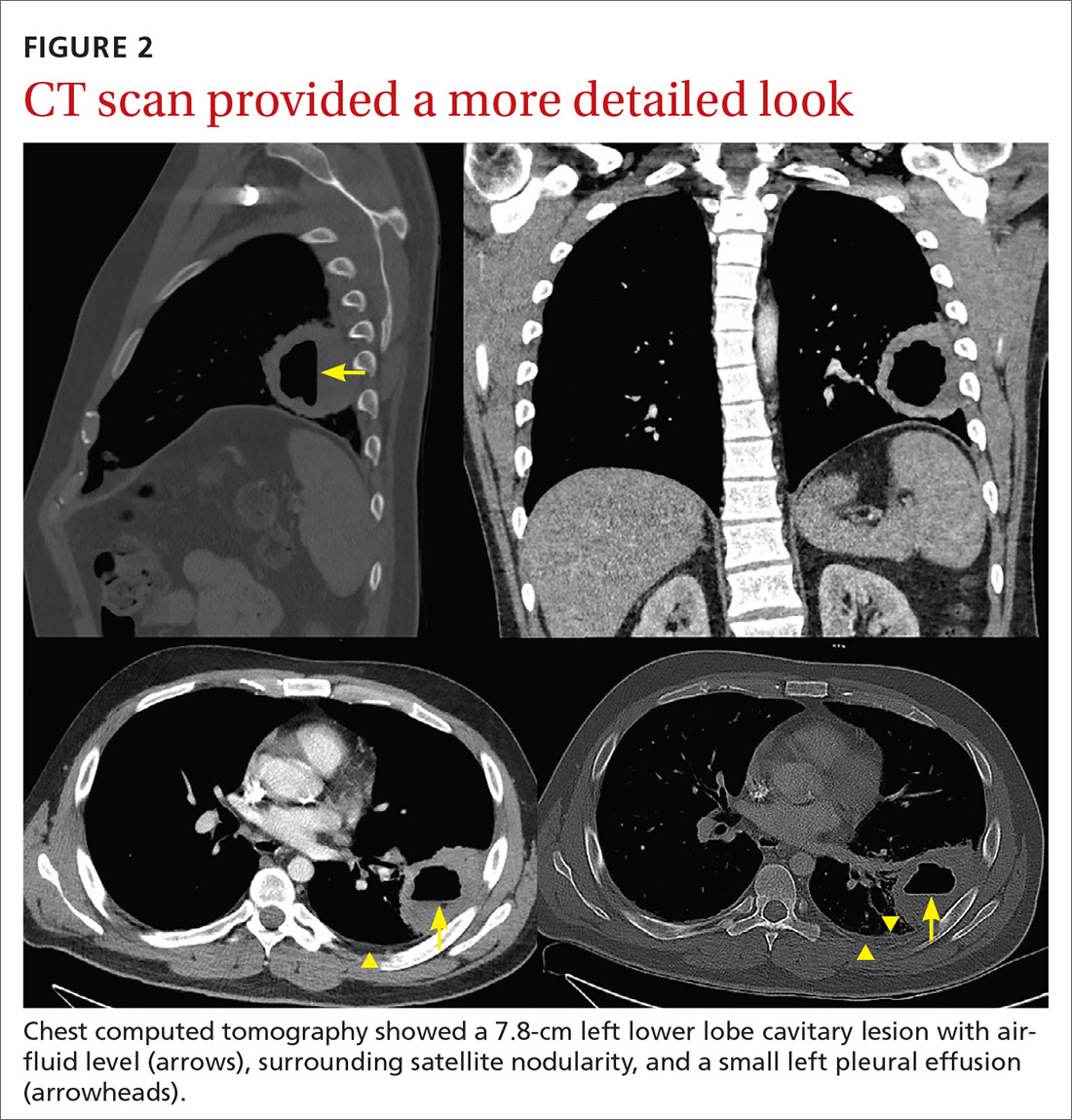

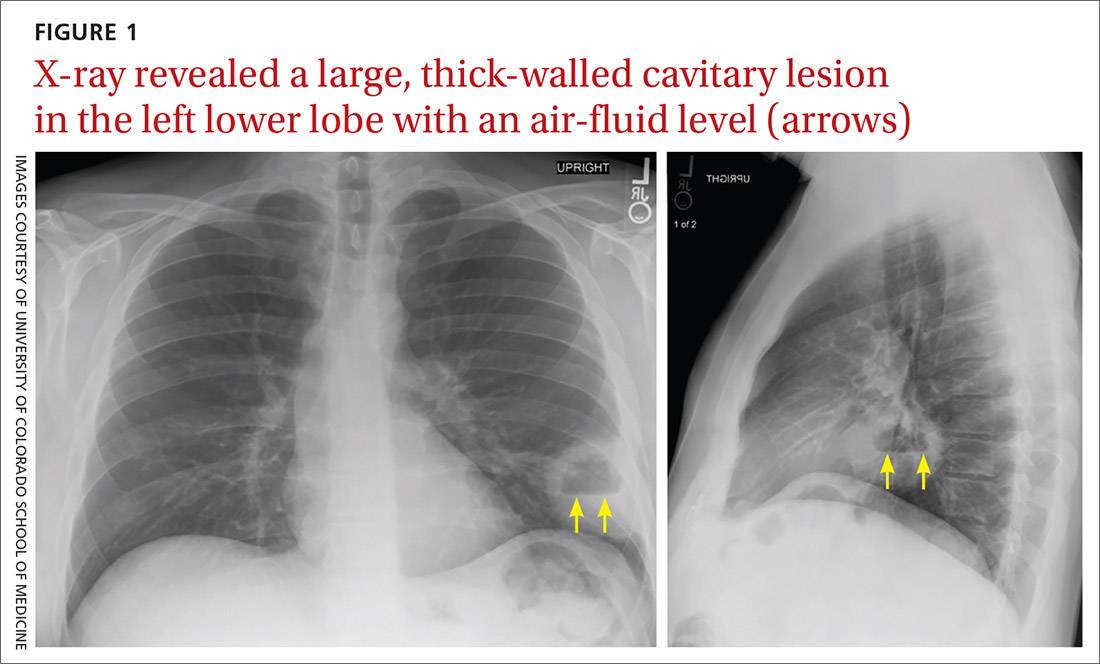

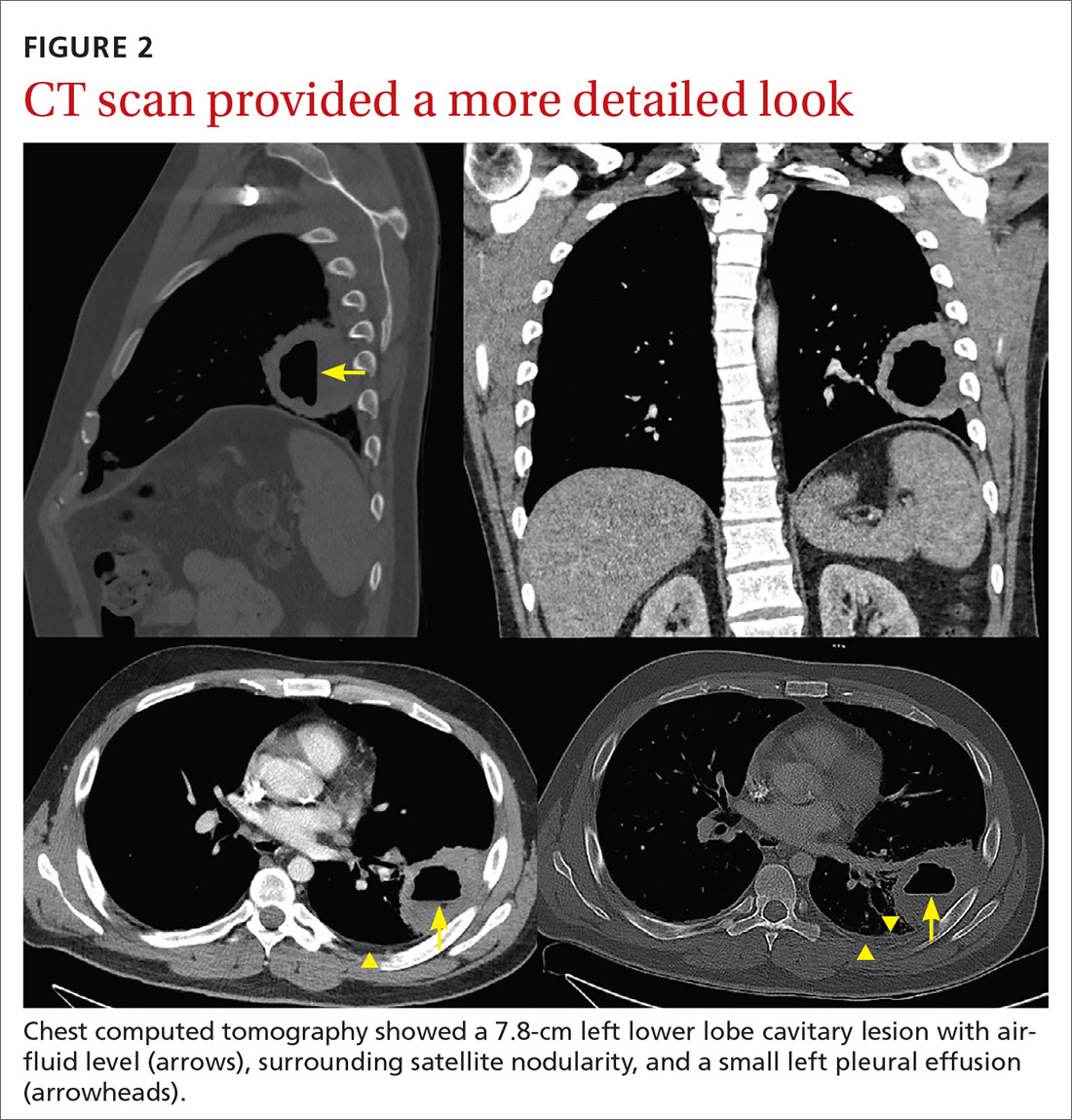

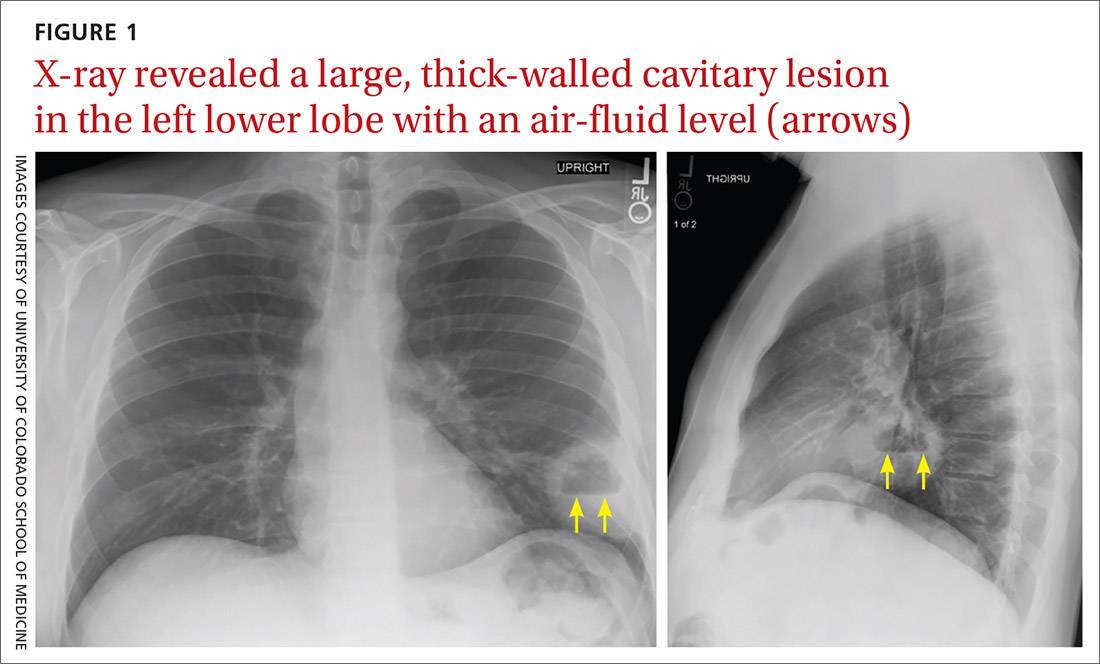

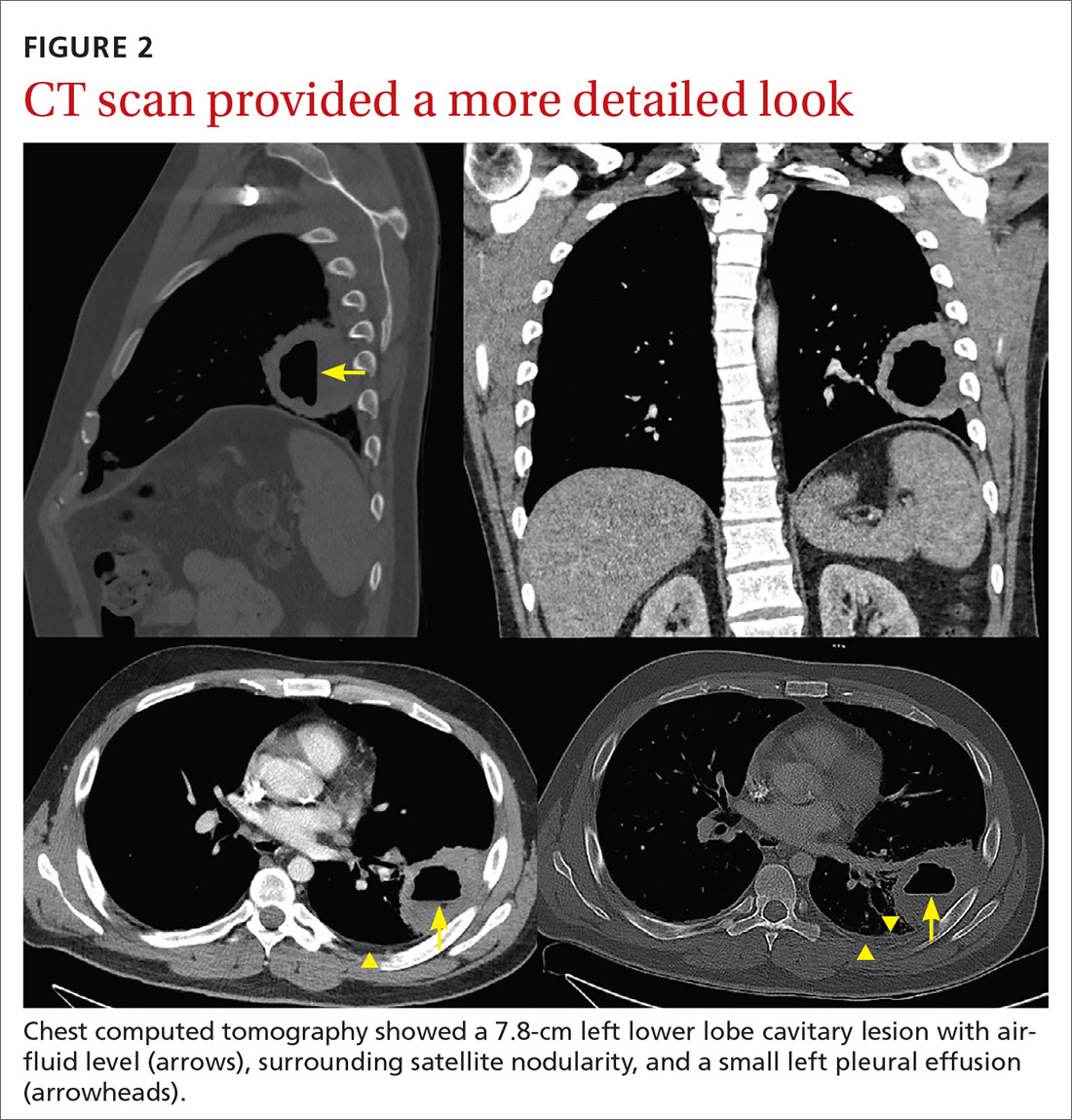

A plain chest radiograph (CXR) performed in the clinic (FIGURE 1) showed a large, thick-walled cavitary lesion with an air-fluid level in the left lower lobe. The patient was directly admitted to the Family Medicine Inpatient Service. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with contrast was ordered to rule out empyema or malignancy. The chest CT confirmed the previous findings while also revealing a surrounding satellite nodularity in the left lower lobe (FIGURE 2). QuantiFERON-TB Gold and HIV tests were both negative.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient was given a diagnosis of a lung abscess based on symptoms and imaging. An extensive smoking history, as well as multiple sedating medications, increased his likelihood of aspiration.

DISCUSSION

Lung abscess is the probable diagnosis in a patient with indolent infectious symptoms (cough, fever, night sweats) developing over days to weeks and a CXR finding of pulmonary opacity, often with an air-fluid level.1-4 A lung abscess is a circumscribed collection of pus in the lung parenchyma that develops as a result of microbial infection.4

Primary vs secondary abscess. Lung abscesses can be divided into 2 groups: primary and secondary abscesses. Primary abscesses (60%) occur without any other medical condition or in patients prone to aspiration.5 Secondary abscesses occur in the setting of a comorbid medical condition, such as lung disease, heart disease, bronchogenic neoplasm, or immunocompromised status.5

Continue to: With a primary lung abscess...

With a primary lung abscess, oropharyngeal contents are aspirated (generally while the patient is unconscious) and contain mixed flora.2 The aspirate typically migrates to the posterior segments of the upper lobes and to the superior segments of the lower lobes. These abscesses are usually singular and have an air-fluid level.1,2

Secondary lung abscesses occur in bronchial obstruction (by tumor, foreign body, or enlarged lymph nodes), with coexisting lung diseases (bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, infected pulmonary infarcts, lung contusion) or by direct spread (broncho-esophageal fistula, subphrenic abscess).6 Secondary abscesses are associated with a poorer prognosis, dependent on the patient’s general condition and underlying disease.7

What to rule out

The differential diagnosis of cavitary lung lesion includes tuberculosis, necrotizing pneumonia, bronchial carcinoma, pulmonary embolism, vasculitis (eg, Churg-Strauss syndrome), and localized pleural empyema.1,4 A CT scan is helpful to differentiate between a parenchymal lesion and pleural collection, which may not be as clear on CXR.1,4

Tuberculosis manifests with fatigue, weight loss, and night sweats; a chest CT will reveal a cavitating lesion (usually upper lobe) with a characteristic “rim sign” that includes caseous necrosis surrounded by a peripheral enhancing rim.8

Necrotizing pneumonia manifests as acute, fulminant infection. The most common causative organisms on sputum culture are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas species. Plain radiography will reveal multiple cavities and often associated pleural effusion and empyema.9

Continue to: Excavating bronchogenic carcinomas

Excavating bronchogenic carcinomas differ from a lung abscess in that a patient with the latter is typically, but not always, febrile and has purulent sputum. On imaging, a bronchogenic carcinoma has a thicker and more irregular wall than a lung abscess.10

Treatment

When antibiotics first became available, penicillin was used to treat lung abscess.11 Then IV clindamycin became the drug of choice after 2 trials demonstrated its superiority to IV penicillin.12,13 More recently, clindamycin alone has fallen out of favor due to growing anaerobic resistance.14

Current therapy includes beta-lactam with beta-lactamase inhibitors.14 Lung abscesses are typically polymicrobial and thus carry different degrees of antibiotic resistance.15,16 If culture data are available, targeted therapy is preferred, especially for secondary abscesses.7 Antibiotic therapy is usually continued until a CXR reveals a small lesion or is clear, which may require several months of outpatient oral antibiotic therapy.4

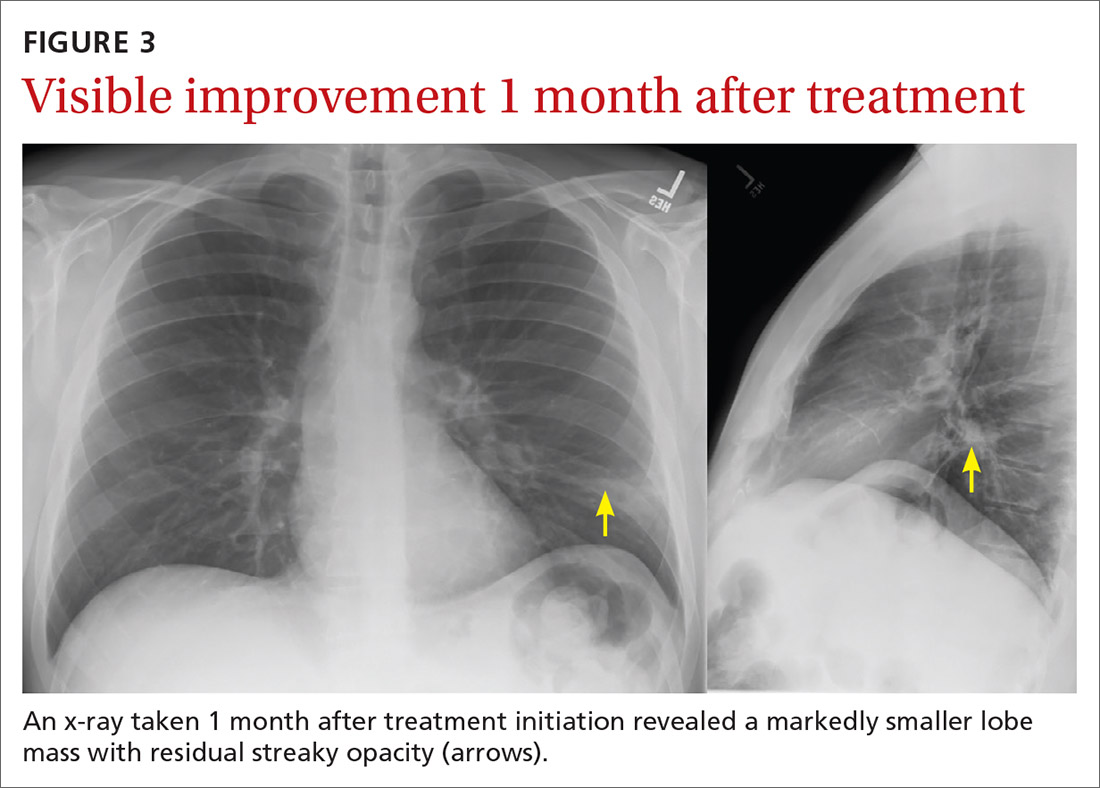

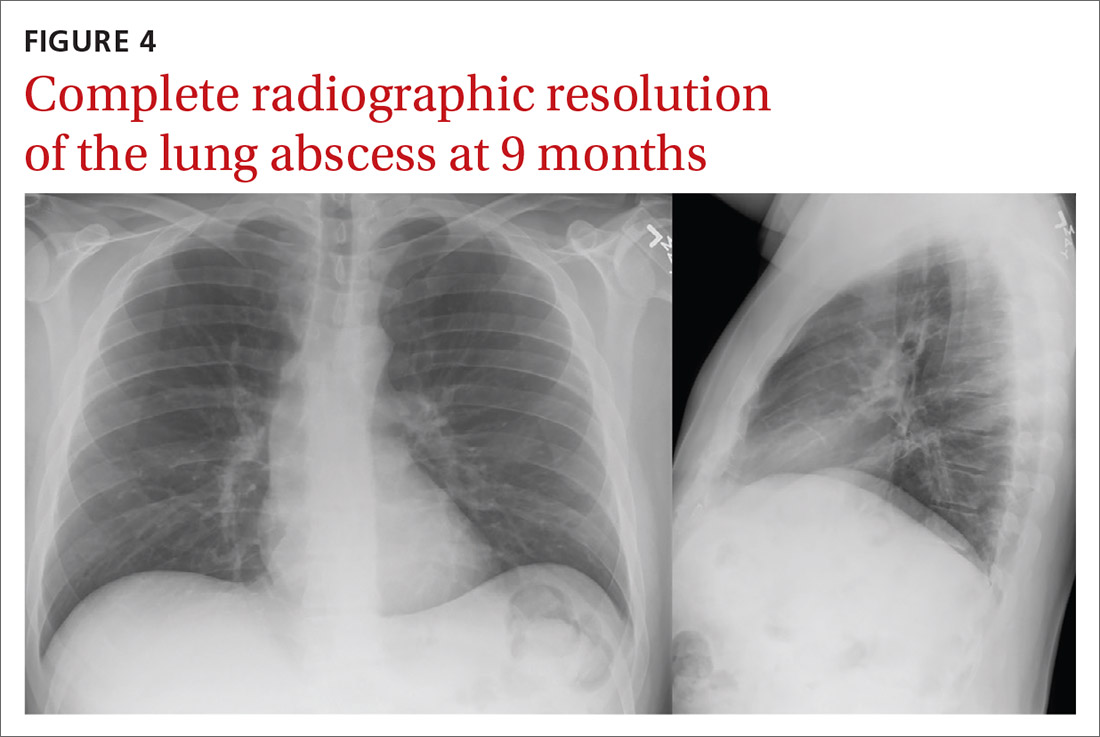

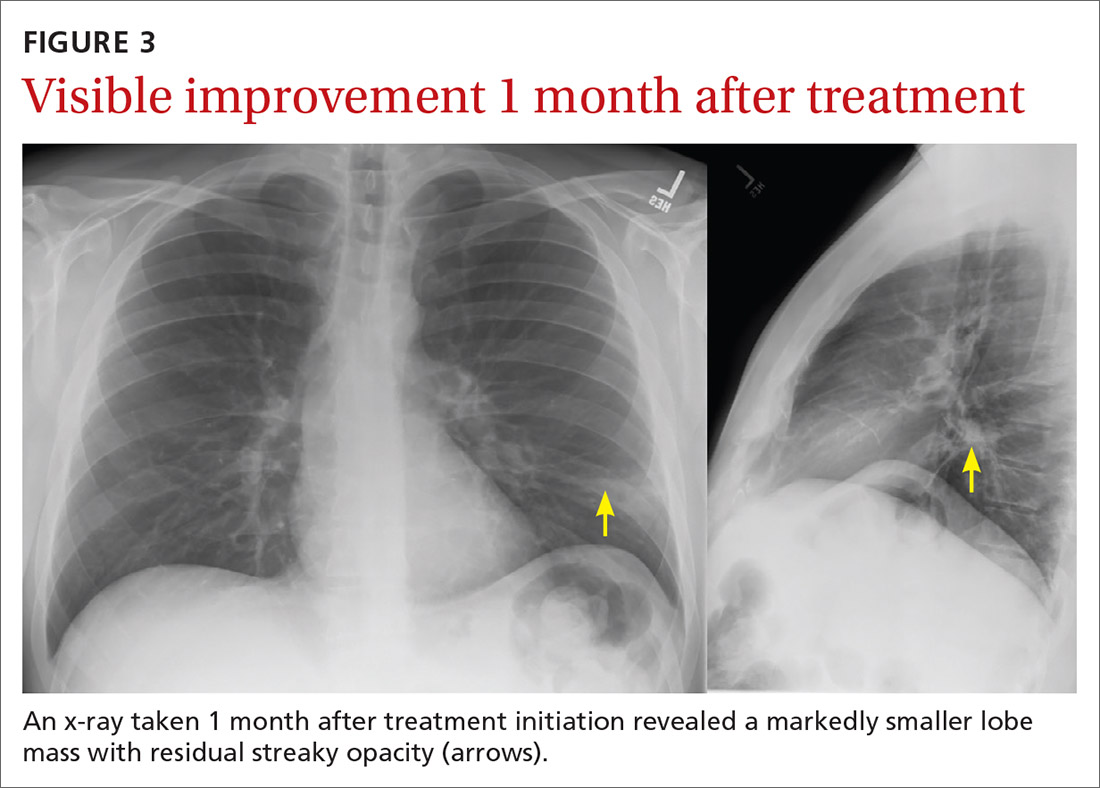

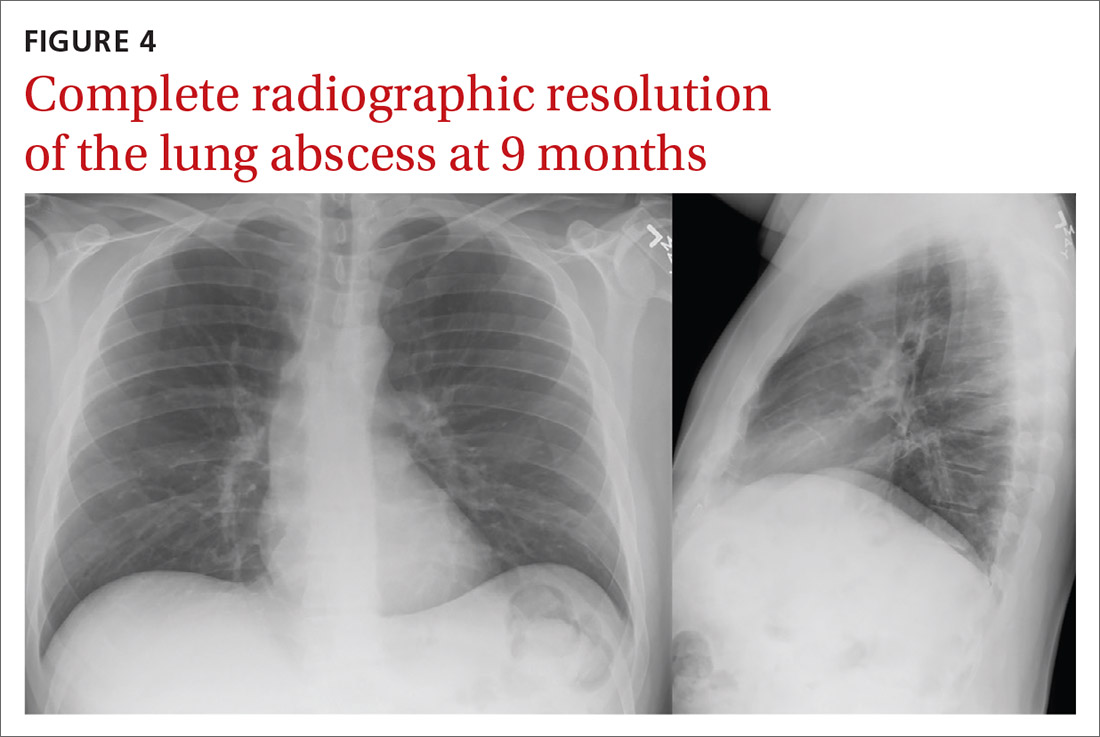

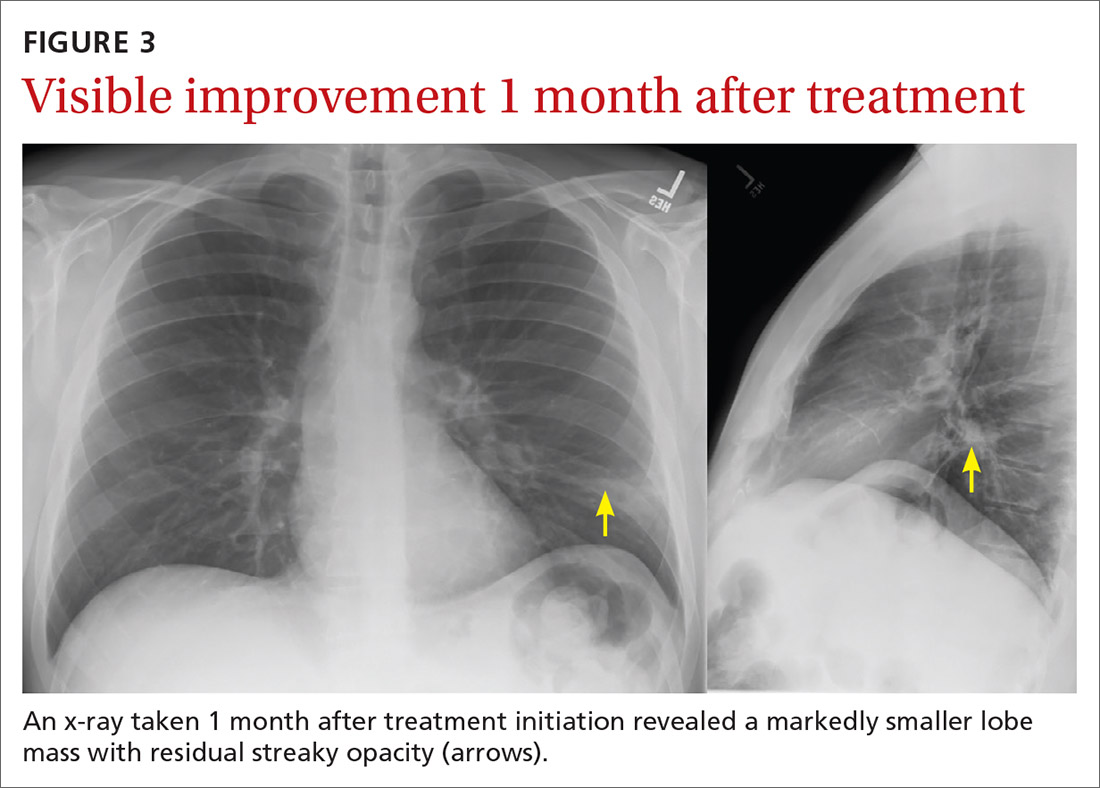

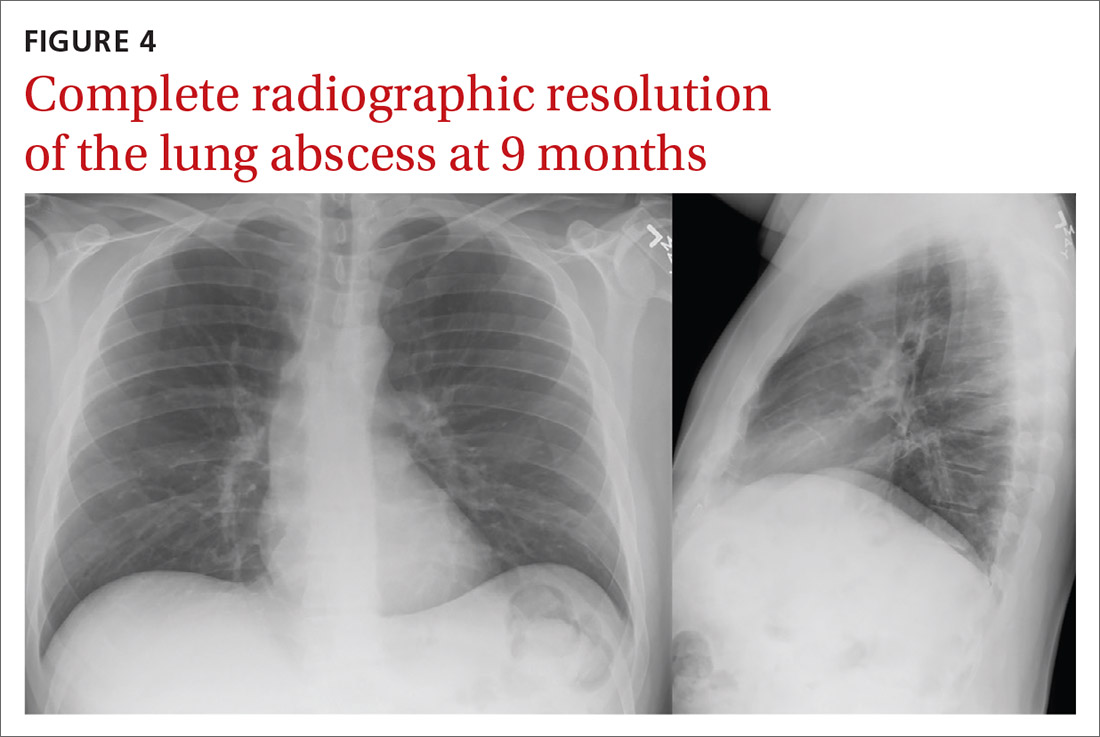

Our patient was treated with IV clindamycin for 3 days in the hospital. Clindamycin was chosen due to his penicillin allergy and started empirically without any culture data. He was transitioned to oral clindamycin and completed a total 3-week course as his CXR continued to show improvement (FIGURE 3). He did not undergo bronchoscopy. A follow-up CXR showed resolution of lung abscess at 9 months. (FIGURE 4).

THE TAKEAWAY

All patients with lung abscesses should have sputum culture with gram stain done—ideally prior to starting antibiotics.3,4 Bronchoscopy should be considered for patients with atypical presentations or those who fail standard therapy, but may be used in other cases, as well.3

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; [email protected]

1. Hassan M, Asciak R, Rizk R, et al. Lung abscess or empyema? Taking a closer look. Thorax. 2018;73:887-889. https://doi. org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211604

2. Moreira J da SM, Camargo J de JP, Felicetti JC, et al. Lung abscess: analysis of 252 consecutive cases diagnosed between 1968 and 2004. J Bras Pneumol. 2006;32:136-43. https://doi.org/10.1590/ s1806-37132006000200009

3. Schiza S, Siafakas NM. Clinical presentation and management of empyema, lung abscess and pleural effusion. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12:205-211. https://doi.org/10.1097/01. mcp.0000219270.73180.8b

4. Yazbeck MF, Dahdel M, Kalra A, et al. Lung abscess: update on microbiology and management. Am J Ther. 2014;21:217-221. https://doi.org/10.1097/MJT.0b013e3182383c9b

5. Nicolini A, Cilloniz C, Senarega R, et al. Lung abscess due to Streptococcus pneumoniae: a case series and brief review of the literature. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2014;82:276-285. https://doi. org/10.5603/PiAP.2014.0033

6. Puligandla PS, Laberge J-M. Respiratory infections: pneumonia, lung abscess, and empyema. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2008;17:42-52. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2007.10.007

7. Marra A, Hillejan L, Ukena D. [Management of Lung Abscess]. Zentralbl Chir. 2015;140 (suppl 1):S47-S53. https://doi. org/10.1055/s-0035-1557883

THE CASE

A 37-year-old man with a history of asthma, schizoaffective disorder, and tobacco use (36 packs per year) presented to the clinic after 5 days of worsening cough, reproducible left-sided chest pain, and increasing shortness of breath. He also experienced chills, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting but was afebrile. The patient had not travelled recently nor had direct contact with anyone sick. He also denied intravenous (IV) drug use, alcohol use, and bloody sputum. Recently, he had intentionally lost weight, as recommended by his psychiatrist.

Medication review revealed that he was taking many central-acting agents for schizoaffective disorder, including alprazolam, aripiprazole, desvenlafaxine, and quetiapine. Due to his intermittent asthma since childhood, he used an albuterol inhaler as needed, which currently offered only minimal relief. He denied any history of hospitalization or intubation for asthma.

During the clinic visit, his blood pressure was 90/60 mm Hg and his heart rate was normal. His pulse oximetry was 92% on room air. On physical examination, he had normal-appearing dentition. Auscultation revealed bilateral expiratory wheezes with decreased breath sounds at the left lower lobe.

A plain chest radiograph (CXR) performed in the clinic (FIGURE 1) showed a large, thick-walled cavitary lesion with an air-fluid level in the left lower lobe. The patient was directly admitted to the Family Medicine Inpatient Service. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with contrast was ordered to rule out empyema or malignancy. The chest CT confirmed the previous findings while also revealing a surrounding satellite nodularity in the left lower lobe (FIGURE 2). QuantiFERON-TB Gold and HIV tests were both negative.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient was given a diagnosis of a lung abscess based on symptoms and imaging. An extensive smoking history, as well as multiple sedating medications, increased his likelihood of aspiration.

DISCUSSION

Lung abscess is the probable diagnosis in a patient with indolent infectious symptoms (cough, fever, night sweats) developing over days to weeks and a CXR finding of pulmonary opacity, often with an air-fluid level.1-4 A lung abscess is a circumscribed collection of pus in the lung parenchyma that develops as a result of microbial infection.4

Primary vs secondary abscess. Lung abscesses can be divided into 2 groups: primary and secondary abscesses. Primary abscesses (60%) occur without any other medical condition or in patients prone to aspiration.5 Secondary abscesses occur in the setting of a comorbid medical condition, such as lung disease, heart disease, bronchogenic neoplasm, or immunocompromised status.5

Continue to: With a primary lung abscess...

With a primary lung abscess, oropharyngeal contents are aspirated (generally while the patient is unconscious) and contain mixed flora.2 The aspirate typically migrates to the posterior segments of the upper lobes and to the superior segments of the lower lobes. These abscesses are usually singular and have an air-fluid level.1,2

Secondary lung abscesses occur in bronchial obstruction (by tumor, foreign body, or enlarged lymph nodes), with coexisting lung diseases (bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, infected pulmonary infarcts, lung contusion) or by direct spread (broncho-esophageal fistula, subphrenic abscess).6 Secondary abscesses are associated with a poorer prognosis, dependent on the patient’s general condition and underlying disease.7

What to rule out

The differential diagnosis of cavitary lung lesion includes tuberculosis, necrotizing pneumonia, bronchial carcinoma, pulmonary embolism, vasculitis (eg, Churg-Strauss syndrome), and localized pleural empyema.1,4 A CT scan is helpful to differentiate between a parenchymal lesion and pleural collection, which may not be as clear on CXR.1,4

Tuberculosis manifests with fatigue, weight loss, and night sweats; a chest CT will reveal a cavitating lesion (usually upper lobe) with a characteristic “rim sign” that includes caseous necrosis surrounded by a peripheral enhancing rim.8

Necrotizing pneumonia manifests as acute, fulminant infection. The most common causative organisms on sputum culture are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas species. Plain radiography will reveal multiple cavities and often associated pleural effusion and empyema.9

Continue to: Excavating bronchogenic carcinomas

Excavating bronchogenic carcinomas differ from a lung abscess in that a patient with the latter is typically, but not always, febrile and has purulent sputum. On imaging, a bronchogenic carcinoma has a thicker and more irregular wall than a lung abscess.10

Treatment

When antibiotics first became available, penicillin was used to treat lung abscess.11 Then IV clindamycin became the drug of choice after 2 trials demonstrated its superiority to IV penicillin.12,13 More recently, clindamycin alone has fallen out of favor due to growing anaerobic resistance.14

Current therapy includes beta-lactam with beta-lactamase inhibitors.14 Lung abscesses are typically polymicrobial and thus carry different degrees of antibiotic resistance.15,16 If culture data are available, targeted therapy is preferred, especially for secondary abscesses.7 Antibiotic therapy is usually continued until a CXR reveals a small lesion or is clear, which may require several months of outpatient oral antibiotic therapy.4

Our patient was treated with IV clindamycin for 3 days in the hospital. Clindamycin was chosen due to his penicillin allergy and started empirically without any culture data. He was transitioned to oral clindamycin and completed a total 3-week course as his CXR continued to show improvement (FIGURE 3). He did not undergo bronchoscopy. A follow-up CXR showed resolution of lung abscess at 9 months. (FIGURE 4).

THE TAKEAWAY

All patients with lung abscesses should have sputum culture with gram stain done—ideally prior to starting antibiotics.3,4 Bronchoscopy should be considered for patients with atypical presentations or those who fail standard therapy, but may be used in other cases, as well.3

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; [email protected]

THE CASE

A 37-year-old man with a history of asthma, schizoaffective disorder, and tobacco use (36 packs per year) presented to the clinic after 5 days of worsening cough, reproducible left-sided chest pain, and increasing shortness of breath. He also experienced chills, fatigue, nausea, and vomiting but was afebrile. The patient had not travelled recently nor had direct contact with anyone sick. He also denied intravenous (IV) drug use, alcohol use, and bloody sputum. Recently, he had intentionally lost weight, as recommended by his psychiatrist.

Medication review revealed that he was taking many central-acting agents for schizoaffective disorder, including alprazolam, aripiprazole, desvenlafaxine, and quetiapine. Due to his intermittent asthma since childhood, he used an albuterol inhaler as needed, which currently offered only minimal relief. He denied any history of hospitalization or intubation for asthma.

During the clinic visit, his blood pressure was 90/60 mm Hg and his heart rate was normal. His pulse oximetry was 92% on room air. On physical examination, he had normal-appearing dentition. Auscultation revealed bilateral expiratory wheezes with decreased breath sounds at the left lower lobe.

A plain chest radiograph (CXR) performed in the clinic (FIGURE 1) showed a large, thick-walled cavitary lesion with an air-fluid level in the left lower lobe. The patient was directly admitted to the Family Medicine Inpatient Service. Computed tomography (CT) of the chest with contrast was ordered to rule out empyema or malignancy. The chest CT confirmed the previous findings while also revealing a surrounding satellite nodularity in the left lower lobe (FIGURE 2). QuantiFERON-TB Gold and HIV tests were both negative.

THE DIAGNOSIS

The patient was given a diagnosis of a lung abscess based on symptoms and imaging. An extensive smoking history, as well as multiple sedating medications, increased his likelihood of aspiration.

DISCUSSION

Lung abscess is the probable diagnosis in a patient with indolent infectious symptoms (cough, fever, night sweats) developing over days to weeks and a CXR finding of pulmonary opacity, often with an air-fluid level.1-4 A lung abscess is a circumscribed collection of pus in the lung parenchyma that develops as a result of microbial infection.4

Primary vs secondary abscess. Lung abscesses can be divided into 2 groups: primary and secondary abscesses. Primary abscesses (60%) occur without any other medical condition or in patients prone to aspiration.5 Secondary abscesses occur in the setting of a comorbid medical condition, such as lung disease, heart disease, bronchogenic neoplasm, or immunocompromised status.5

Continue to: With a primary lung abscess...

With a primary lung abscess, oropharyngeal contents are aspirated (generally while the patient is unconscious) and contain mixed flora.2 The aspirate typically migrates to the posterior segments of the upper lobes and to the superior segments of the lower lobes. These abscesses are usually singular and have an air-fluid level.1,2

Secondary lung abscesses occur in bronchial obstruction (by tumor, foreign body, or enlarged lymph nodes), with coexisting lung diseases (bronchiectasis, cystic fibrosis, infected pulmonary infarcts, lung contusion) or by direct spread (broncho-esophageal fistula, subphrenic abscess).6 Secondary abscesses are associated with a poorer prognosis, dependent on the patient’s general condition and underlying disease.7

What to rule out

The differential diagnosis of cavitary lung lesion includes tuberculosis, necrotizing pneumonia, bronchial carcinoma, pulmonary embolism, vasculitis (eg, Churg-Strauss syndrome), and localized pleural empyema.1,4 A CT scan is helpful to differentiate between a parenchymal lesion and pleural collection, which may not be as clear on CXR.1,4

Tuberculosis manifests with fatigue, weight loss, and night sweats; a chest CT will reveal a cavitating lesion (usually upper lobe) with a characteristic “rim sign” that includes caseous necrosis surrounded by a peripheral enhancing rim.8

Necrotizing pneumonia manifests as acute, fulminant infection. The most common causative organisms on sputum culture are Streptococcus pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Pseudomonas species. Plain radiography will reveal multiple cavities and often associated pleural effusion and empyema.9

Continue to: Excavating bronchogenic carcinomas

Excavating bronchogenic carcinomas differ from a lung abscess in that a patient with the latter is typically, but not always, febrile and has purulent sputum. On imaging, a bronchogenic carcinoma has a thicker and more irregular wall than a lung abscess.10

Treatment

When antibiotics first became available, penicillin was used to treat lung abscess.11 Then IV clindamycin became the drug of choice after 2 trials demonstrated its superiority to IV penicillin.12,13 More recently, clindamycin alone has fallen out of favor due to growing anaerobic resistance.14

Current therapy includes beta-lactam with beta-lactamase inhibitors.14 Lung abscesses are typically polymicrobial and thus carry different degrees of antibiotic resistance.15,16 If culture data are available, targeted therapy is preferred, especially for secondary abscesses.7 Antibiotic therapy is usually continued until a CXR reveals a small lesion or is clear, which may require several months of outpatient oral antibiotic therapy.4

Our patient was treated with IV clindamycin for 3 days in the hospital. Clindamycin was chosen due to his penicillin allergy and started empirically without any culture data. He was transitioned to oral clindamycin and completed a total 3-week course as his CXR continued to show improvement (FIGURE 3). He did not undergo bronchoscopy. A follow-up CXR showed resolution of lung abscess at 9 months. (FIGURE 4).

THE TAKEAWAY

All patients with lung abscesses should have sputum culture with gram stain done—ideally prior to starting antibiotics.3,4 Bronchoscopy should be considered for patients with atypical presentations or those who fail standard therapy, but may be used in other cases, as well.3

CORRESPONDENCE

Morteza Khodaee, MD, MPH, AFW Clinic, 3055 Roslyn Street, Denver, CO 80238; [email protected]

1. Hassan M, Asciak R, Rizk R, et al. Lung abscess or empyema? Taking a closer look. Thorax. 2018;73:887-889. https://doi. org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211604

2. Moreira J da SM, Camargo J de JP, Felicetti JC, et al. Lung abscess: analysis of 252 consecutive cases diagnosed between 1968 and 2004. J Bras Pneumol. 2006;32:136-43. https://doi.org/10.1590/ s1806-37132006000200009

3. Schiza S, Siafakas NM. Clinical presentation and management of empyema, lung abscess and pleural effusion. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12:205-211. https://doi.org/10.1097/01. mcp.0000219270.73180.8b

4. Yazbeck MF, Dahdel M, Kalra A, et al. Lung abscess: update on microbiology and management. Am J Ther. 2014;21:217-221. https://doi.org/10.1097/MJT.0b013e3182383c9b

5. Nicolini A, Cilloniz C, Senarega R, et al. Lung abscess due to Streptococcus pneumoniae: a case series and brief review of the literature. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2014;82:276-285. https://doi. org/10.5603/PiAP.2014.0033

6. Puligandla PS, Laberge J-M. Respiratory infections: pneumonia, lung abscess, and empyema. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2008;17:42-52. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2007.10.007

7. Marra A, Hillejan L, Ukena D. [Management of Lung Abscess]. Zentralbl Chir. 2015;140 (suppl 1):S47-S53. https://doi. org/10.1055/s-0035-1557883

1. Hassan M, Asciak R, Rizk R, et al. Lung abscess or empyema? Taking a closer look. Thorax. 2018;73:887-889. https://doi. org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-211604

2. Moreira J da SM, Camargo J de JP, Felicetti JC, et al. Lung abscess: analysis of 252 consecutive cases diagnosed between 1968 and 2004. J Bras Pneumol. 2006;32:136-43. https://doi.org/10.1590/ s1806-37132006000200009

3. Schiza S, Siafakas NM. Clinical presentation and management of empyema, lung abscess and pleural effusion. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2006;12:205-211. https://doi.org/10.1097/01. mcp.0000219270.73180.8b

4. Yazbeck MF, Dahdel M, Kalra A, et al. Lung abscess: update on microbiology and management. Am J Ther. 2014;21:217-221. https://doi.org/10.1097/MJT.0b013e3182383c9b

5. Nicolini A, Cilloniz C, Senarega R, et al. Lung abscess due to Streptococcus pneumoniae: a case series and brief review of the literature. Pneumonol Alergol Pol. 2014;82:276-285. https://doi. org/10.5603/PiAP.2014.0033

6. Puligandla PS, Laberge J-M. Respiratory infections: pneumonia, lung abscess, and empyema. Semin Pediatr Surg. 2008;17:42-52. https://doi.org/10.1053/j.sempedsurg.2007.10.007

7. Marra A, Hillejan L, Ukena D. [Management of Lung Abscess]. Zentralbl Chir. 2015;140 (suppl 1):S47-S53. https://doi. org/10.1055/s-0035-1557883

Painful facial blisters, fever, and conjunctivitis

A 58-year-old woman with a history of hepatitis C, liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, hypothyroidism, and peripheral neuropathy presented to our clinic with left ear pain and blisters on her lips, nose, and mouth. On exam, the patient’s left tympanic membrane was opaque, and she had multiple 3- to 5-mm irregularly shaped ulcers on her right buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips. She was given a diagnosis of acute otitis media and prescribed a course of amoxicillin. The physician, who was uncertain about the cause of her gingivostomatitis, took a “shotgun approach” and prescribed a nystatin/diphenhydramine/lidocaine mouthwash.

Three weeks later, the patient returned complaining of cloudy urine, dysuria, fever, vomiting, and “pink eye.” On exam, her right eye was mildly injected with no drainage. She had normal eye movements and no ophthalmoplegia. We diagnosed viral (vs allergic) conjunctivitis and pyelonephritis in this patient and advised her to use lubricant eyedrops and an oral antihistamine for the eye. We also started her on cefpodoxime (200 mg bid for 10 days) for pyelonephritis.

Three days later, the patient called our clinic and said that her right eye was not improving. We prescribed ofloxacin ophthalmic drops, 1 to 2 drops every 6 hours, for presumed bacterial conjunctivitis.

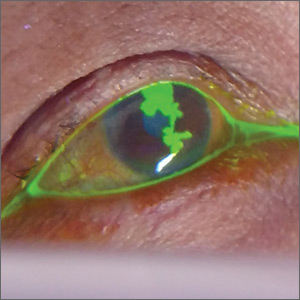

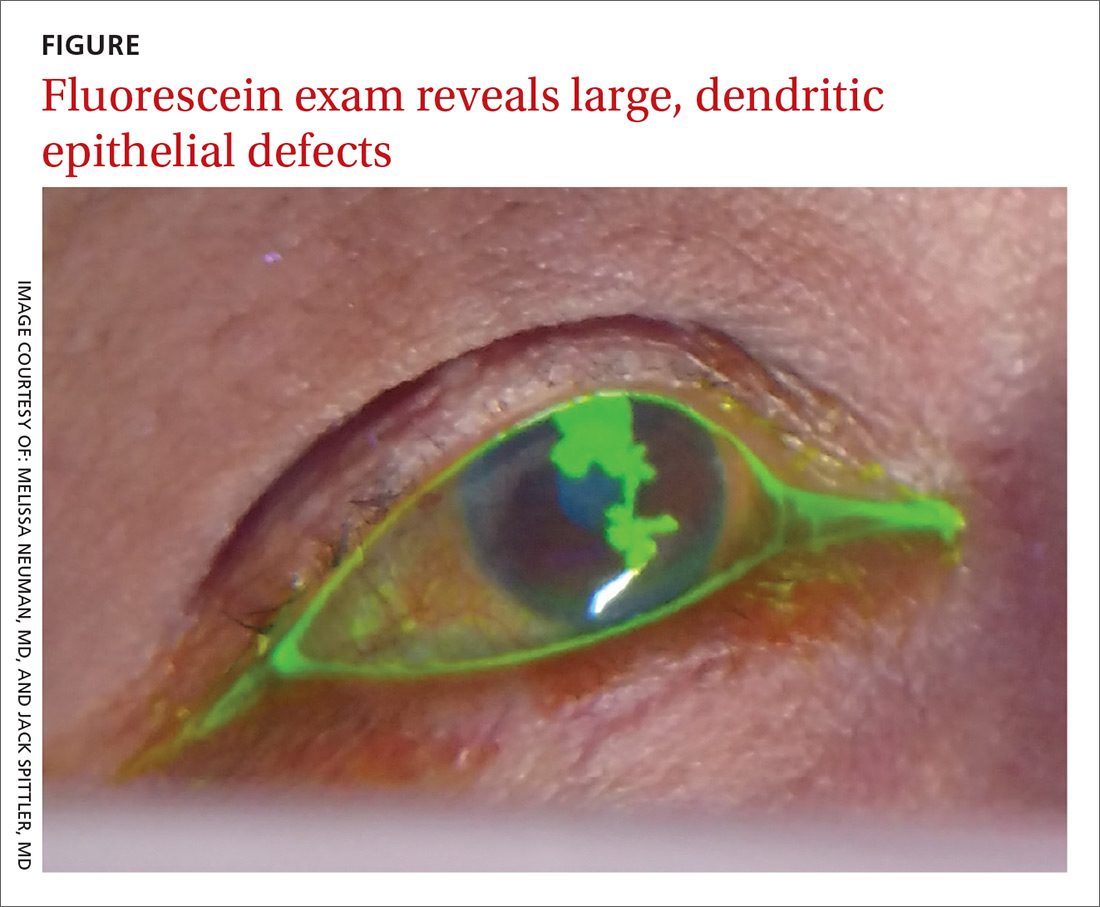

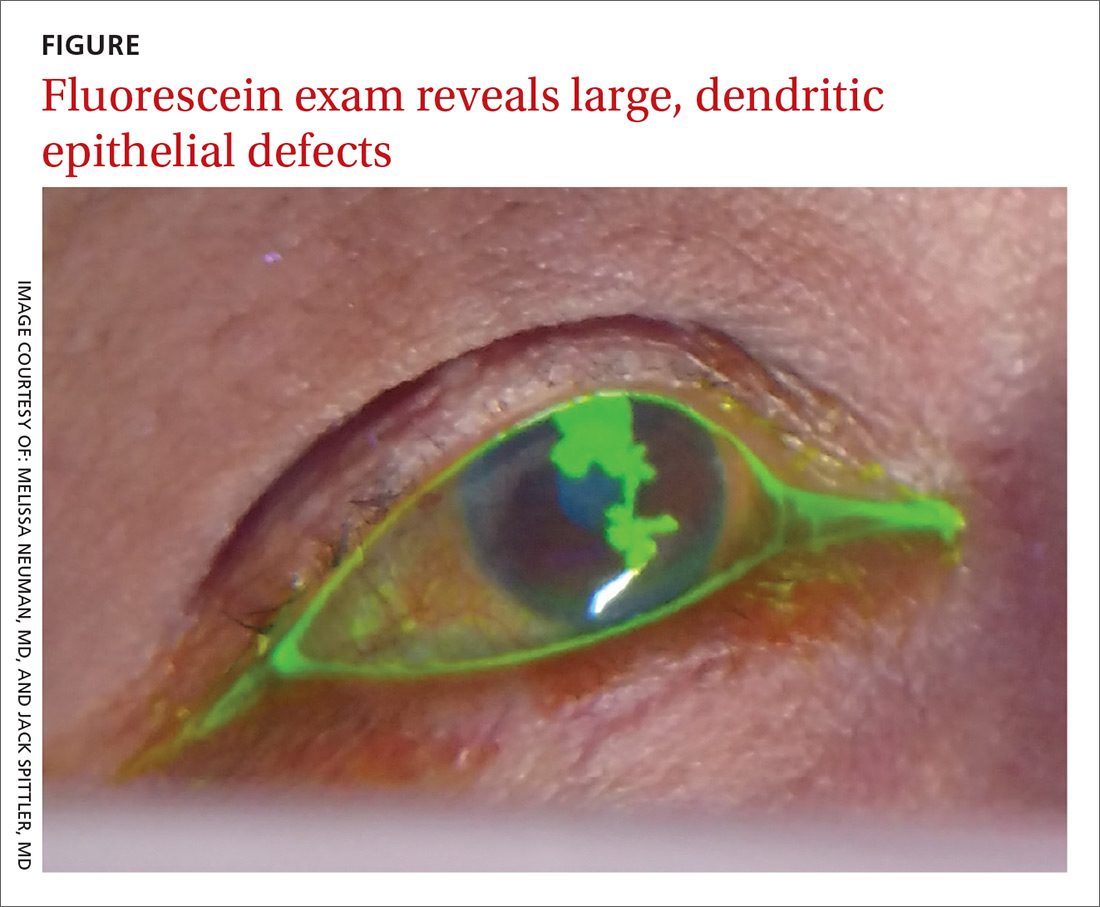

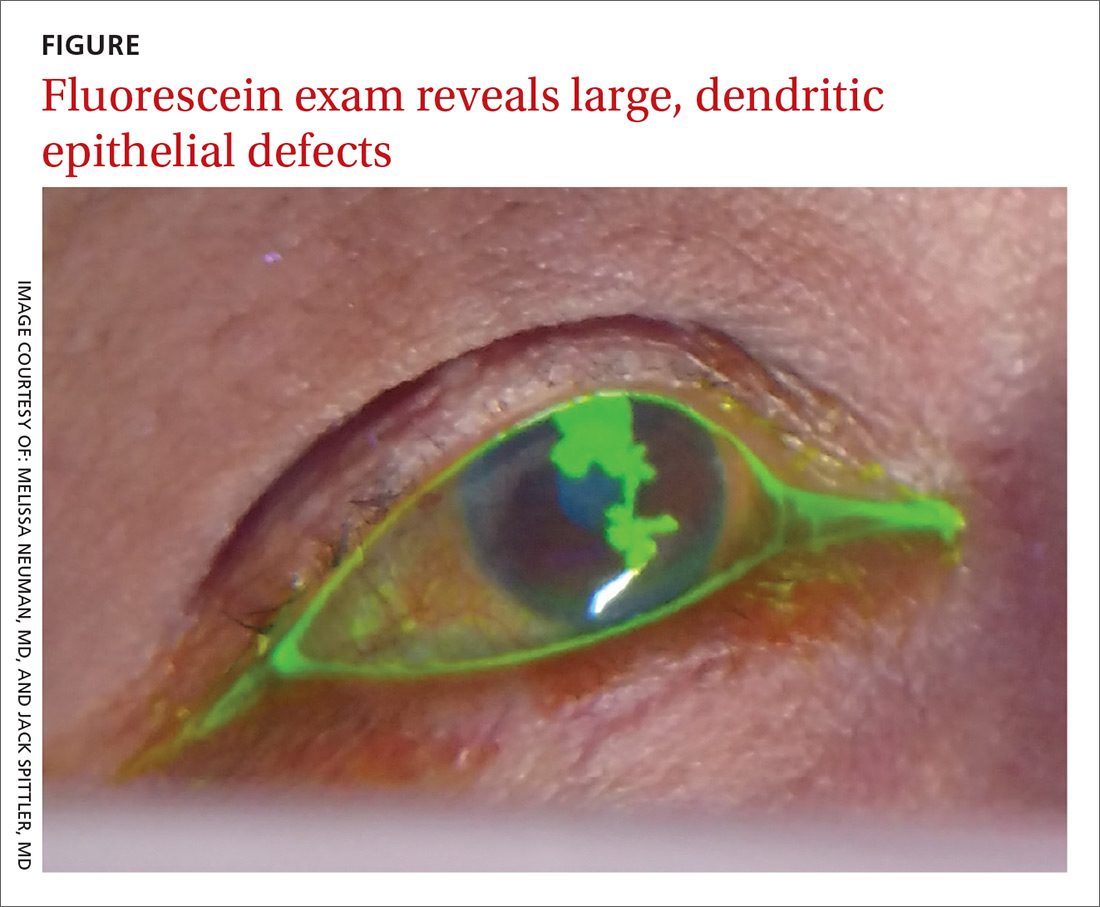

Four days later, she returned to our clinic; she had been using the ofloxacin drops and antihistamine but was experiencing worsening symptoms, including itching of her right eye, associated blurriness, and decreased vision. She had been using a warm compress on the eye and found that it was getting sticky and crusted. A gray corneal opacity was seen on physical exam, and a fluorescein exam was performed (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Herpes simplex virus keratitis

The patient was sent to the ophthalmology clinic, where a slit-lamp examination of the right eye showed 3+ injection, large dendritic epithelial defects spanning the majority of the cornea (with 10% haze), and trace nuclear sclerosis of the lens. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis, with a likely neurotrophic component (decreased sensation of the affected eye compared with that of the other eye). There was no evidence of secondary infection.

Discussion

The global incidence of HSV keratitis is approximately 1.5 million, including 40,000 new cases of monocular visual impairment or blindness each year.1 Primary infection with HSV-1 occurs following direct contact with infected mucosa or skin surfaces and inoculation. (Our patient likely transferred the infection by touching her eyes after touching her nose or mouth.) The virus remains in sensory ganglia for the lifetime of the host. Most ocular disease is thought to represent recurrent HSV (rather than a primary ocular infection).2 It has been proposed that HSV-1 latency may also occur in the cornea.

The symptoms of HSV keratitis include eye pain, redness, blurred vision, tearing, discharge, and sensitivity to light.

The 4 diagnostic categories

There are 4 categories of HSV keratitis, based on the location of the infection: epithelial, stromal, endotheliitis, and neurotrophic keratopathy.

Epithelial. The most common form, epithelial HSV manifests as dendritic or geographic lesions of the cornea.3 Geographic lesions occur when a dendrite widens and assumes an amoeboid shape.

Continue to: Stromal

Stromal. Stromal involvement accounts for 20% to 25% of presentations4 and may cause significant anterior chamber inflammation. Vision loss can result from permanent stromal scarring.5

Endotheliitis. Keratic precipitates (on top of stromal and epithelial edema) and a mild-to-moderate iritis are signs of endotheliitis.5

Neurotrophic keratopathy. This form of HSV keratitis is associated with corneal hypoesthesia or complete anesthesia secondary to damage of the corneal nerves, which can occur in any form of ocular HSV. Anesthesia may lead to nonhealing corneal epithelial defects.6 These defects, which are generally oval lesions, do not represent active viral disease and are made worse by antiviral drops. These lesions may cause stromal scarring, corneal perforation, or secondary bacterial infection.

Treatment consists of supportive care using artificial tears and prophylactic antibiotic eye drops, if appropriate; more advanced ophthalmologic treatments may be needed for advanced disease.7

Continue to: Other conditions, including conjunctivitis, have similar symptoms

Other conditions, including conjunctivitis, have similar symptoms

The differential for redness of the eye includes conditions such as conjunctivitis, glaucoma, and keratitis.

Conjunctivitis of any form—bacterial, viral, allergic, or toxic—involves injection of both the palpebral and bulbar conjunctiva.

Acute angle closure glaucoma can involve symptoms of headache, malaise, nausea, and vomiting. In addition, the pupil is fixed in mid-dilation, and the cornea becomes hazy.

Anterior uveitis/iritis causes sensitivity to light in both the affected and unaffected eyes, as well as ciliary flush (a red ring around the iris). Typically, there is no eye discharge.

Bacterial keratitis causes foreign body sensation and purulent discharge. This form of keratitis usually occurs due to improper wear of contact lenses.

Continue to: Viral keratitis...

Viral keratitis is characterized by photophobia, foreign body sensation, and watery discharge. A faint branching grey opacity may be seen on penlight exam, and dendrites may be seen with fluorescein.

Scleritis involves severe, boring pain of the eye in addition to photophobia and headache. It is usually associated with systemic inflammatory disorders.

Subconjunctival hemorrhage is asymptomatic and occurs following trauma.

Cellulitis manifests following trauma with a deep violet color and marked edema.

Continue to: Standard Tx

Standard Tx: Antiviral medications

Topical antiviral therapy is the standard treatment for epithelial HSV keratitis, although oral antiviral medications are equally effective. A randomized trial found that using an oral agent in addition to a topical antiviral did not improve outcomes.8 A 2015 systematic review found that topical antivirals acyclovir, ganciclovir, brivudine, trifluridine were equally effective in treatment outcome; 90% of patients healed within 2 weeks.9

Recurrent ocular HSV-1 infections are treated in the same way as the initial infection. Recurrent infection can be prevented with daily suppressive therapy. In one study, patients who took suppressive therapy (acyclovir 400 mg bid) for 1 year had 19% recurrence of ocular infection vs 32% in the placebo group.10

Prompt Tx is key. If the infection is superficial—involving only the outer layer of the cornea (epithelium)—the eye should heal without scarring with proper treatment. However, if the infection is not promptly treated or if deeper layers are involved, scarring of the cornea may occur. This can lead to vision loss or blindness.

Continue to: A missed opportunity for an earlier diagnosis

A missed opportunity for an earlier diagnosis

This case highlights the importance of conducting a thorough exam to identify findings that could shift the diagnosis from a simple allergic, viral, or bacterial conjunctivitis. It is always better to consider primary oral HSV infection than resort to a “shotgun approach” of treating candida and pain with an oral mixture. In this case, the ulcers and vesicles on the buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips were a missed sign of primary HSV infection. Making this diagnosis might have prevented the ocular disease, as the treatment would have been an oral antiviral.

If conjunctivitis is refractory to usual management, the patient must be seen to rule out dangerous eye diagnoses such as HSV keratitis, preseptal or orbital cellulitis, or in the worst case, acute angle closure glaucoma. If there is uncertainty regarding diagnosis, a fluorescein exam is helpful. This simple in-office exam can facilitate a referral to Ophthalmology or the emergency department for a slit-lamp exam and appropriate therapy.

Our patient was started on valacyclovir 1 g bid, trifluridine eyedrops (5×/d), and erythromycin ophthalmic ointment (3×/d), with Ophthalmology follow-up in 1 week.

CORRESPONDENCE

John Spittler, MD, 3055 Roslyn St, Suite 100, Denver, CO 80238; [email protected]

1. Farooq AV, Shukla D. Herpes simplex epithelial and stromal keratitis: an epidemiologic update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57:448-462.

2. Holland EJ, Mahanti RL, Belongia EA, et al. Ocular involvement in an outbreak of herpes gladiatorum. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;114:680-684.

3. Cook SD. Herpes simplex virus in the eye. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76:365-366.

4. Liesegang TJ. Herpes simplex virus epidemiology and ocular importance. Cornea. 2001;20:1-13.

5. Sekar Babu M, Balammal G, Sangeetha G, et al. A review on viral keratitis caused by herpes simplex virus. J Sci. 2011;1:1-10.

6. Hamrah P, Cruzat A, Dastjerdi MH, et al. Corneal sensation and subbasal nerve alterations in patients with herpes simplex keratitis: an in vivo confocal microscopy study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1930-1936.

7. Bonini S, Rama P, Olzi D, et al. Neurotrophic keratitis. Eye. 2003;17:989-995.

8. Szentmáry N, Módis L, Imre L, et al. Diagnostics and treatment of infectious keratitis. Orv Hetil. 2017;158:1203-1212.

9. Wilhelmus KR. Antiviral treatment and other therapeutic interventions for herpes simplex virus epithelial keratitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(1):CD002898.

10. Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. Acyclovir for the prevention of recurrent herpes simplex virus eye disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:300-306.

A 58-year-old woman with a history of hepatitis C, liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, hypothyroidism, and peripheral neuropathy presented to our clinic with left ear pain and blisters on her lips, nose, and mouth. On exam, the patient’s left tympanic membrane was opaque, and she had multiple 3- to 5-mm irregularly shaped ulcers on her right buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips. She was given a diagnosis of acute otitis media and prescribed a course of amoxicillin. The physician, who was uncertain about the cause of her gingivostomatitis, took a “shotgun approach” and prescribed a nystatin/diphenhydramine/lidocaine mouthwash.

Three weeks later, the patient returned complaining of cloudy urine, dysuria, fever, vomiting, and “pink eye.” On exam, her right eye was mildly injected with no drainage. She had normal eye movements and no ophthalmoplegia. We diagnosed viral (vs allergic) conjunctivitis and pyelonephritis in this patient and advised her to use lubricant eyedrops and an oral antihistamine for the eye. We also started her on cefpodoxime (200 mg bid for 10 days) for pyelonephritis.

Three days later, the patient called our clinic and said that her right eye was not improving. We prescribed ofloxacin ophthalmic drops, 1 to 2 drops every 6 hours, for presumed bacterial conjunctivitis.

Four days later, she returned to our clinic; she had been using the ofloxacin drops and antihistamine but was experiencing worsening symptoms, including itching of her right eye, associated blurriness, and decreased vision. She had been using a warm compress on the eye and found that it was getting sticky and crusted. A gray corneal opacity was seen on physical exam, and a fluorescein exam was performed (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Herpes simplex virus keratitis

The patient was sent to the ophthalmology clinic, where a slit-lamp examination of the right eye showed 3+ injection, large dendritic epithelial defects spanning the majority of the cornea (with 10% haze), and trace nuclear sclerosis of the lens. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis, with a likely neurotrophic component (decreased sensation of the affected eye compared with that of the other eye). There was no evidence of secondary infection.

Discussion

The global incidence of HSV keratitis is approximately 1.5 million, including 40,000 new cases of monocular visual impairment or blindness each year.1 Primary infection with HSV-1 occurs following direct contact with infected mucosa or skin surfaces and inoculation. (Our patient likely transferred the infection by touching her eyes after touching her nose or mouth.) The virus remains in sensory ganglia for the lifetime of the host. Most ocular disease is thought to represent recurrent HSV (rather than a primary ocular infection).2 It has been proposed that HSV-1 latency may also occur in the cornea.

The symptoms of HSV keratitis include eye pain, redness, blurred vision, tearing, discharge, and sensitivity to light.

The 4 diagnostic categories

There are 4 categories of HSV keratitis, based on the location of the infection: epithelial, stromal, endotheliitis, and neurotrophic keratopathy.

Epithelial. The most common form, epithelial HSV manifests as dendritic or geographic lesions of the cornea.3 Geographic lesions occur when a dendrite widens and assumes an amoeboid shape.

Continue to: Stromal

Stromal. Stromal involvement accounts for 20% to 25% of presentations4 and may cause significant anterior chamber inflammation. Vision loss can result from permanent stromal scarring.5

Endotheliitis. Keratic precipitates (on top of stromal and epithelial edema) and a mild-to-moderate iritis are signs of endotheliitis.5

Neurotrophic keratopathy. This form of HSV keratitis is associated with corneal hypoesthesia or complete anesthesia secondary to damage of the corneal nerves, which can occur in any form of ocular HSV. Anesthesia may lead to nonhealing corneal epithelial defects.6 These defects, which are generally oval lesions, do not represent active viral disease and are made worse by antiviral drops. These lesions may cause stromal scarring, corneal perforation, or secondary bacterial infection.

Treatment consists of supportive care using artificial tears and prophylactic antibiotic eye drops, if appropriate; more advanced ophthalmologic treatments may be needed for advanced disease.7

Continue to: Other conditions, including conjunctivitis, have similar symptoms

Other conditions, including conjunctivitis, have similar symptoms

The differential for redness of the eye includes conditions such as conjunctivitis, glaucoma, and keratitis.

Conjunctivitis of any form—bacterial, viral, allergic, or toxic—involves injection of both the palpebral and bulbar conjunctiva.

Acute angle closure glaucoma can involve symptoms of headache, malaise, nausea, and vomiting. In addition, the pupil is fixed in mid-dilation, and the cornea becomes hazy.

Anterior uveitis/iritis causes sensitivity to light in both the affected and unaffected eyes, as well as ciliary flush (a red ring around the iris). Typically, there is no eye discharge.

Bacterial keratitis causes foreign body sensation and purulent discharge. This form of keratitis usually occurs due to improper wear of contact lenses.

Continue to: Viral keratitis...

Viral keratitis is characterized by photophobia, foreign body sensation, and watery discharge. A faint branching grey opacity may be seen on penlight exam, and dendrites may be seen with fluorescein.

Scleritis involves severe, boring pain of the eye in addition to photophobia and headache. It is usually associated with systemic inflammatory disorders.

Subconjunctival hemorrhage is asymptomatic and occurs following trauma.

Cellulitis manifests following trauma with a deep violet color and marked edema.

Continue to: Standard Tx

Standard Tx: Antiviral medications

Topical antiviral therapy is the standard treatment for epithelial HSV keratitis, although oral antiviral medications are equally effective. A randomized trial found that using an oral agent in addition to a topical antiviral did not improve outcomes.8 A 2015 systematic review found that topical antivirals acyclovir, ganciclovir, brivudine, trifluridine were equally effective in treatment outcome; 90% of patients healed within 2 weeks.9

Recurrent ocular HSV-1 infections are treated in the same way as the initial infection. Recurrent infection can be prevented with daily suppressive therapy. In one study, patients who took suppressive therapy (acyclovir 400 mg bid) for 1 year had 19% recurrence of ocular infection vs 32% in the placebo group.10

Prompt Tx is key. If the infection is superficial—involving only the outer layer of the cornea (epithelium)—the eye should heal without scarring with proper treatment. However, if the infection is not promptly treated or if deeper layers are involved, scarring of the cornea may occur. This can lead to vision loss or blindness.

Continue to: A missed opportunity for an earlier diagnosis

A missed opportunity for an earlier diagnosis

This case highlights the importance of conducting a thorough exam to identify findings that could shift the diagnosis from a simple allergic, viral, or bacterial conjunctivitis. It is always better to consider primary oral HSV infection than resort to a “shotgun approach” of treating candida and pain with an oral mixture. In this case, the ulcers and vesicles on the buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips were a missed sign of primary HSV infection. Making this diagnosis might have prevented the ocular disease, as the treatment would have been an oral antiviral.

If conjunctivitis is refractory to usual management, the patient must be seen to rule out dangerous eye diagnoses such as HSV keratitis, preseptal or orbital cellulitis, or in the worst case, acute angle closure glaucoma. If there is uncertainty regarding diagnosis, a fluorescein exam is helpful. This simple in-office exam can facilitate a referral to Ophthalmology or the emergency department for a slit-lamp exam and appropriate therapy.

Our patient was started on valacyclovir 1 g bid, trifluridine eyedrops (5×/d), and erythromycin ophthalmic ointment (3×/d), with Ophthalmology follow-up in 1 week.

CORRESPONDENCE

John Spittler, MD, 3055 Roslyn St, Suite 100, Denver, CO 80238; [email protected]

A 58-year-old woman with a history of hepatitis C, liver cirrhosis, hepatocellular carcinoma, hypothyroidism, and peripheral neuropathy presented to our clinic with left ear pain and blisters on her lips, nose, and mouth. On exam, the patient’s left tympanic membrane was opaque, and she had multiple 3- to 5-mm irregularly shaped ulcers on her right buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips. She was given a diagnosis of acute otitis media and prescribed a course of amoxicillin. The physician, who was uncertain about the cause of her gingivostomatitis, took a “shotgun approach” and prescribed a nystatin/diphenhydramine/lidocaine mouthwash.

Three weeks later, the patient returned complaining of cloudy urine, dysuria, fever, vomiting, and “pink eye.” On exam, her right eye was mildly injected with no drainage. She had normal eye movements and no ophthalmoplegia. We diagnosed viral (vs allergic) conjunctivitis and pyelonephritis in this patient and advised her to use lubricant eyedrops and an oral antihistamine for the eye. We also started her on cefpodoxime (200 mg bid for 10 days) for pyelonephritis.

Three days later, the patient called our clinic and said that her right eye was not improving. We prescribed ofloxacin ophthalmic drops, 1 to 2 drops every 6 hours, for presumed bacterial conjunctivitis.

Four days later, she returned to our clinic; she had been using the ofloxacin drops and antihistamine but was experiencing worsening symptoms, including itching of her right eye, associated blurriness, and decreased vision. She had been using a warm compress on the eye and found that it was getting sticky and crusted. A gray corneal opacity was seen on physical exam, and a fluorescein exam was performed (FIGURE).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Herpes simplex virus keratitis

The patient was sent to the ophthalmology clinic, where a slit-lamp examination of the right eye showed 3+ injection, large dendritic epithelial defects spanning the majority of the cornea (with 10% haze), and trace nuclear sclerosis of the lens. These findings were consistent with a diagnosis of herpes simplex virus (HSV) keratitis, with a likely neurotrophic component (decreased sensation of the affected eye compared with that of the other eye). There was no evidence of secondary infection.

Discussion

The global incidence of HSV keratitis is approximately 1.5 million, including 40,000 new cases of monocular visual impairment or blindness each year.1 Primary infection with HSV-1 occurs following direct contact with infected mucosa or skin surfaces and inoculation. (Our patient likely transferred the infection by touching her eyes after touching her nose or mouth.) The virus remains in sensory ganglia for the lifetime of the host. Most ocular disease is thought to represent recurrent HSV (rather than a primary ocular infection).2 It has been proposed that HSV-1 latency may also occur in the cornea.

The symptoms of HSV keratitis include eye pain, redness, blurred vision, tearing, discharge, and sensitivity to light.

The 4 diagnostic categories

There are 4 categories of HSV keratitis, based on the location of the infection: epithelial, stromal, endotheliitis, and neurotrophic keratopathy.

Epithelial. The most common form, epithelial HSV manifests as dendritic or geographic lesions of the cornea.3 Geographic lesions occur when a dendrite widens and assumes an amoeboid shape.

Continue to: Stromal

Stromal. Stromal involvement accounts for 20% to 25% of presentations4 and may cause significant anterior chamber inflammation. Vision loss can result from permanent stromal scarring.5

Endotheliitis. Keratic precipitates (on top of stromal and epithelial edema) and a mild-to-moderate iritis are signs of endotheliitis.5

Neurotrophic keratopathy. This form of HSV keratitis is associated with corneal hypoesthesia or complete anesthesia secondary to damage of the corneal nerves, which can occur in any form of ocular HSV. Anesthesia may lead to nonhealing corneal epithelial defects.6 These defects, which are generally oval lesions, do not represent active viral disease and are made worse by antiviral drops. These lesions may cause stromal scarring, corneal perforation, or secondary bacterial infection.

Treatment consists of supportive care using artificial tears and prophylactic antibiotic eye drops, if appropriate; more advanced ophthalmologic treatments may be needed for advanced disease.7

Continue to: Other conditions, including conjunctivitis, have similar symptoms

Other conditions, including conjunctivitis, have similar symptoms

The differential for redness of the eye includes conditions such as conjunctivitis, glaucoma, and keratitis.

Conjunctivitis of any form—bacterial, viral, allergic, or toxic—involves injection of both the palpebral and bulbar conjunctiva.

Acute angle closure glaucoma can involve symptoms of headache, malaise, nausea, and vomiting. In addition, the pupil is fixed in mid-dilation, and the cornea becomes hazy.

Anterior uveitis/iritis causes sensitivity to light in both the affected and unaffected eyes, as well as ciliary flush (a red ring around the iris). Typically, there is no eye discharge.

Bacterial keratitis causes foreign body sensation and purulent discharge. This form of keratitis usually occurs due to improper wear of contact lenses.

Continue to: Viral keratitis...

Viral keratitis is characterized by photophobia, foreign body sensation, and watery discharge. A faint branching grey opacity may be seen on penlight exam, and dendrites may be seen with fluorescein.

Scleritis involves severe, boring pain of the eye in addition to photophobia and headache. It is usually associated with systemic inflammatory disorders.

Subconjunctival hemorrhage is asymptomatic and occurs following trauma.

Cellulitis manifests following trauma with a deep violet color and marked edema.

Continue to: Standard Tx

Standard Tx: Antiviral medications

Topical antiviral therapy is the standard treatment for epithelial HSV keratitis, although oral antiviral medications are equally effective. A randomized trial found that using an oral agent in addition to a topical antiviral did not improve outcomes.8 A 2015 systematic review found that topical antivirals acyclovir, ganciclovir, brivudine, trifluridine were equally effective in treatment outcome; 90% of patients healed within 2 weeks.9

Recurrent ocular HSV-1 infections are treated in the same way as the initial infection. Recurrent infection can be prevented with daily suppressive therapy. In one study, patients who took suppressive therapy (acyclovir 400 mg bid) for 1 year had 19% recurrence of ocular infection vs 32% in the placebo group.10

Prompt Tx is key. If the infection is superficial—involving only the outer layer of the cornea (epithelium)—the eye should heal without scarring with proper treatment. However, if the infection is not promptly treated or if deeper layers are involved, scarring of the cornea may occur. This can lead to vision loss or blindness.

Continue to: A missed opportunity for an earlier diagnosis

A missed opportunity for an earlier diagnosis

This case highlights the importance of conducting a thorough exam to identify findings that could shift the diagnosis from a simple allergic, viral, or bacterial conjunctivitis. It is always better to consider primary oral HSV infection than resort to a “shotgun approach” of treating candida and pain with an oral mixture. In this case, the ulcers and vesicles on the buccal mucosa, gingiva, and lips were a missed sign of primary HSV infection. Making this diagnosis might have prevented the ocular disease, as the treatment would have been an oral antiviral.

If conjunctivitis is refractory to usual management, the patient must be seen to rule out dangerous eye diagnoses such as HSV keratitis, preseptal or orbital cellulitis, or in the worst case, acute angle closure glaucoma. If there is uncertainty regarding diagnosis, a fluorescein exam is helpful. This simple in-office exam can facilitate a referral to Ophthalmology or the emergency department for a slit-lamp exam and appropriate therapy.

Our patient was started on valacyclovir 1 g bid, trifluridine eyedrops (5×/d), and erythromycin ophthalmic ointment (3×/d), with Ophthalmology follow-up in 1 week.

CORRESPONDENCE

John Spittler, MD, 3055 Roslyn St, Suite 100, Denver, CO 80238; [email protected]

1. Farooq AV, Shukla D. Herpes simplex epithelial and stromal keratitis: an epidemiologic update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57:448-462.

2. Holland EJ, Mahanti RL, Belongia EA, et al. Ocular involvement in an outbreak of herpes gladiatorum. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;114:680-684.

3. Cook SD. Herpes simplex virus in the eye. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76:365-366.

4. Liesegang TJ. Herpes simplex virus epidemiology and ocular importance. Cornea. 2001;20:1-13.

5. Sekar Babu M, Balammal G, Sangeetha G, et al. A review on viral keratitis caused by herpes simplex virus. J Sci. 2011;1:1-10.

6. Hamrah P, Cruzat A, Dastjerdi MH, et al. Corneal sensation and subbasal nerve alterations in patients with herpes simplex keratitis: an in vivo confocal microscopy study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1930-1936.

7. Bonini S, Rama P, Olzi D, et al. Neurotrophic keratitis. Eye. 2003;17:989-995.

8. Szentmáry N, Módis L, Imre L, et al. Diagnostics and treatment of infectious keratitis. Orv Hetil. 2017;158:1203-1212.

9. Wilhelmus KR. Antiviral treatment and other therapeutic interventions for herpes simplex virus epithelial keratitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(1):CD002898.

10. Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. Acyclovir for the prevention of recurrent herpes simplex virus eye disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:300-306.

1. Farooq AV, Shukla D. Herpes simplex epithelial and stromal keratitis: an epidemiologic update. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57:448-462.

2. Holland EJ, Mahanti RL, Belongia EA, et al. Ocular involvement in an outbreak of herpes gladiatorum. Am J Ophthalmol. 1992;114:680-684.

3. Cook SD. Herpes simplex virus in the eye. Br J Ophthalmol. 1992;76:365-366.

4. Liesegang TJ. Herpes simplex virus epidemiology and ocular importance. Cornea. 2001;20:1-13.

5. Sekar Babu M, Balammal G, Sangeetha G, et al. A review on viral keratitis caused by herpes simplex virus. J Sci. 2011;1:1-10.

6. Hamrah P, Cruzat A, Dastjerdi MH, et al. Corneal sensation and subbasal nerve alterations in patients with herpes simplex keratitis: an in vivo confocal microscopy study. Ophthalmology. 2010;117:1930-1936.

7. Bonini S, Rama P, Olzi D, et al. Neurotrophic keratitis. Eye. 2003;17:989-995.

8. Szentmáry N, Módis L, Imre L, et al. Diagnostics and treatment of infectious keratitis. Orv Hetil. 2017;158:1203-1212.

9. Wilhelmus KR. Antiviral treatment and other therapeutic interventions for herpes simplex virus epithelial keratitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(1):CD002898.

10. Herpetic Eye Disease Study Group. Acyclovir for the prevention of recurrent herpes simplex virus eye disease. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:300-306.