User login

Transabdominal cerclage for managing recurrent pregnancy loss

CASE A woman with recurrent pregnancy loss

A 38-year-old woman (G4P0221) presents to your office for preconception counseling. Her history is significant for the following: a spontaneous pregnancy loss at 15 weeks’ gestation; a pregnancy loss at 17 weeks secondary to preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM); a cesarean delivery at 30 weeks and 6 days’ gestation after placement of a transvaginal cerclage at 20 weeks for cervical dilation noted on physical exam (the child now has developmental delays); and most recently a delivery at 24 weeks and 4 days due to preterm labor with subsequent neonatal demise (this followed a transvaginal cerclage placed at 13 weeks and 6 days).

How would you counsel this patient?

Cervical insufficiency describes the inability of the cervix to retain a pregnancy in the absence of the signs and symptoms of clinical contractions, labor, or both in the second trimester.1 This condition affects an estimated 1% of obstetric patients and 8% of women with recurrent losses who have experienced a second-trimester loss.2

Diagnosis of cervical insufficiency is based on a history of painless cervical dilation after the first trimester with expulsion of the pregnancy in the second trimester before 24 weeks of gestation without contractions and in the absence of other pathology, such as bleeding, infection, or ruptured membranes.1 Diagnosis also can be made by noting cervical dilation on physical exam during the second trimester; more recently, short cervical length on transvaginal ultrasonography in the second trimester has been used to try to predict when a cervical cerclage may be indicated, although sonographic cervical length is more a marker for risk of preterm birth than for cervical insufficiency specifically.1,3

Given the considerable emotional and physical distress that patients experience with recurrent second-trimester losses and the significant neonatal morbidity and mortality that can occur with preterm delivery, substantial efforts are made to prevent these outcomes by treating patients with cervical insufficiency and those at risk for preterm delivery.

Transvaginal cerclage: A treatment mainstay

Standard treatment options for cervical insufficiency depend on the patient’s history. One of the treatment mainstays for women with prior second-trimester losses or preterm deliveries is transvaginal cervical cerclage. A transvaginal cerclage can be placed using either a Shirodkar technique, in which the vesicocervical mucosa is dissected and a suture is placed as close to the internal cervical os as possible, or a McDonald technique, in which a purse-string suture is placed around the cervicovaginal junction. No randomized trials have compared the effectiveness of these 2 methods, but most observational studies show no difference, and one suggests that the Shirodkar technique may be more effective in obese women specifically.4-6

Indications for transvaginal cerclage. The indication for transvaginal cerclage is based on history, physical exam, or ultrasonography.

A physical-exam indication is the most straightforward of the 3. Transvaginal cerclage placement is indicated if on physical exam in the second trimester a patient has cervical dilation without contractions or infection.1,7

A history-indicated cerclage (typically placed between 12 and 14 weeks’ gestation) is based on a cerclage having been placed in a prior pregnancy due to painless cervical dilation in the second trimester (either ultrasonography- or physical-exam indicated), and it also can be considered in the case of a history of 1 or more second-trimester pregnancy losses related to painless cervical dilation.1

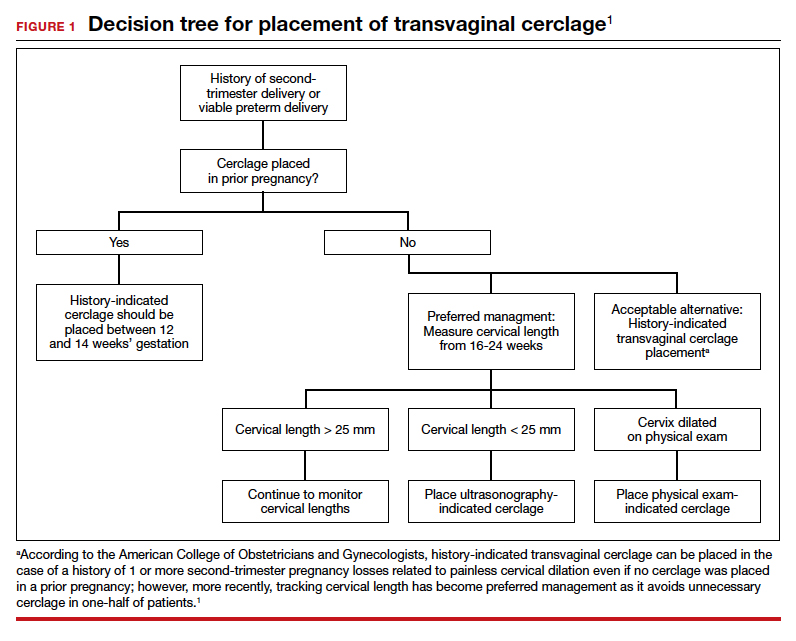

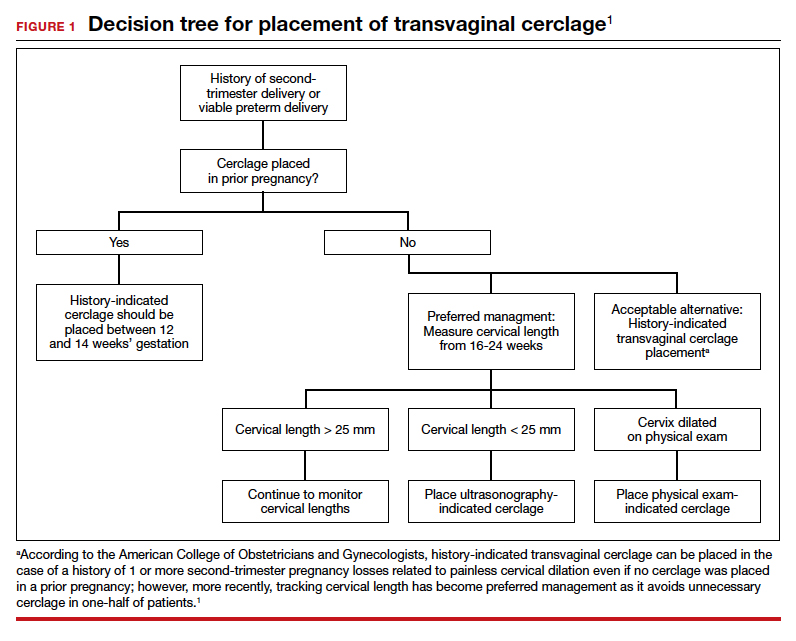

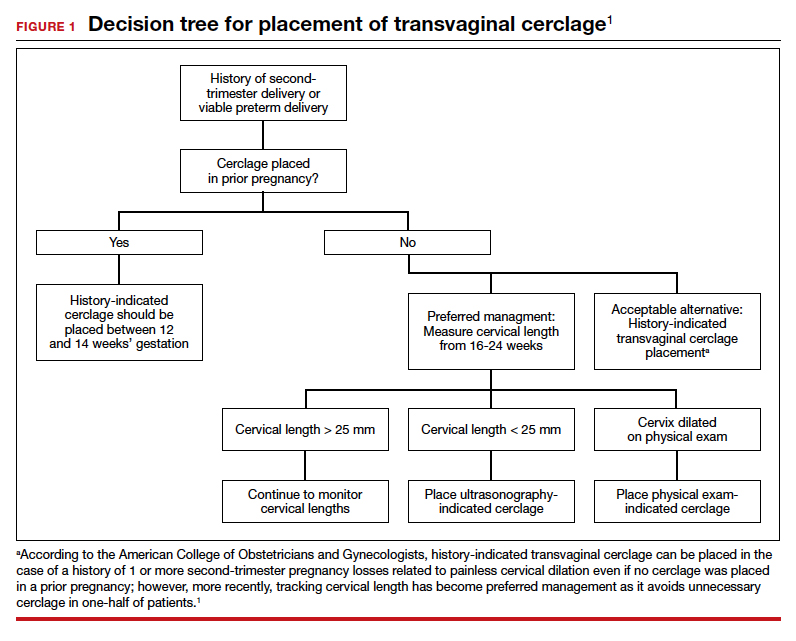

More recent evidence suggests that in patients with 1 prior second-trimester loss or preterm delivery, serial sonographic cervical length can be measured safely from 16 to 24 weeks, with a cerclage being placed only if cervical length decreases to less than 25 mm. By using the ultrasonography-based indication, unnecessary history-indicated cerclages for 1 prior second-trimester or preterm birth can be avoided in more than one-half of patients (FIGURE 1).1,7

Efficacy. The effectiveness of transvaginal cerclage varies by the indication. Authors of a 2017 Cochrane review found an overall reduced risk of giving birth before 34 weeks’ gestation for any indication, with an average relative risk of 0.77.2 Other recent studies showed the following8-10:

- a 63% delivery rate after 28 weeks’ gestation for physical-exam indicated cerclages in the presence of bulging amniotic membranes

- an 86.2% delivery rate after 32 weeks’ gestation for ultrasonography-indicated cerclages

- an 86% delivery rate after 32 weeks’ gestation for a history-indicated cerclage in patients with 2 or more prior second-trimester losses.

Success rates, especially for ultrasonography- and history-indicated cerclage, are thus high. For the 14% who still fail these methods, however, a different management strategy is needed, which is where transabdominal cerclage comes into play.

Continue to: Transabdominal cerclage is an option for certain patients...

Transabdominal cerclage is an option for certain patients

In transabdominal cerclage, an abdominal approach is used to place a stitch at the cervicouterine junction. With this approach, the cerclage can reach a closer proximity to the internal os compared with the vaginal approach, providing better support of the cervical tissue (FIGURE 2).11 Whether performed via laparotomy or laparoscopy, the transabdominal cerclage procedure likely carries higher morbidity than a transvaginal approach, and cesarean delivery is required after placement.

Since transvaginal cerclage often is successful, in most cases the transabdominal approach should not be viewed as the first-line treatment for cervical insufficiency if a history-indicated transvaginal cerclage has not been attempted. For women who fail a history-indicated transvaginal cerclage, however, a transabdominal cerclage has been proven to decrease the rate of preterm delivery and PPROM compared with attempting another history-indicated transvaginal cerclage.11,12

A recent systematic review of pregnancy outcomes after transabdominal cerclage placement reported neonatal survival of 96.5% and an 83% delivery rate after 34 weeks’ gestation.13 Thus, even among a population that failed transvaginal cerclage, a transabdominal cerclage has a high success rate in providing a good pregnancy outcome (TABLE). Transabdominal cerclage also can be considered as first-line treatment in patients who had prior cervical surgery or cervical deformities that might preclude the ability to place a cerclage transvaginally.

CASE Continued: A candidate for transabdominal cerclage

Given the patient’s poor obstetric history, which includes a preterm delivery and neonatal loss despite a history-indicated cerclage, you recommend that the patient have a transabdominal cerclage placed as the procedure has been proven to increase the chances of neonatal survival and delivery after 34 weeks in women with a similar obstetric history. The patient is interested in this option and asks about how this cerclage is placed and when it would need to be placed during her next pregnancy.

Surgical technique for transabdominal cerclage placement

A transabdominal cerclage can be placed via laparotomy, laparoscopy, or robot-assisted laparoscopy. No differences in obstetric outcomes have been shown between the laparotomy and laparoscopic approaches.14,15 Given the benefits of minimally invasive surgery, a laparoscopic or robot-assisted approach is preferred when feasible.

Additionally, for ease of placement, transabdominal cerclage can be placed prior to conception—known as interval placement—or during pregnancy between 10 and 14 weeks (preferably closer to 10 weeks). Because of the increased difficulty in placing a cerclage in the gravid uterus, interval transabdominal cerclage placement is recommended when possible.13,16 Authors of one observational study noted that improved obstetric outcomes occurred with interval placement compared with cerclage placement between 9 and 10 weeks’ gestation, with a delivery rate at more than 34 weeks’ gestation in 90% versus 74% of patients, respectively.16

Continue to: Steps for interval cerclage and during pregnancy...

Steps for interval cerclage and during pregnancy

Our practice is to place transabdominal cerclage via conventional laparoscopy as an interval procedure when possible. We find no benefit in using robotic assistance.

For an interval procedure, the patient is placed in a dorsal lithotomy position, and we place a 10-mm umbilical port, 2 lateral 5-mm ports, 1 suprapubic 5-mm port, and a uterine manipulator. We use a flexible laparoscope to provide optimal visualization of the pelvis from any angle.

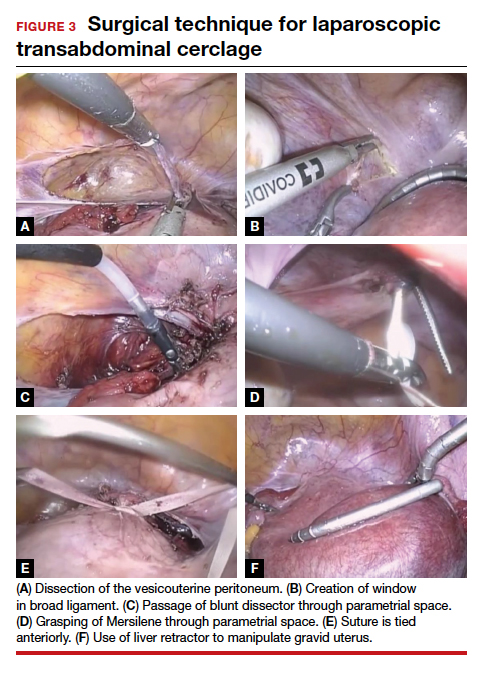

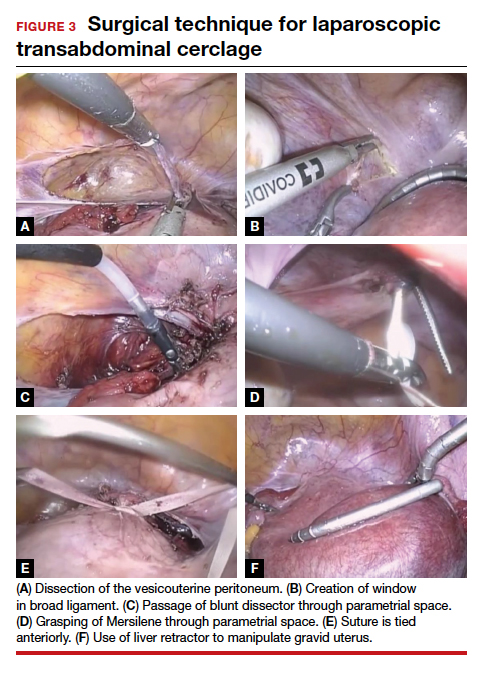

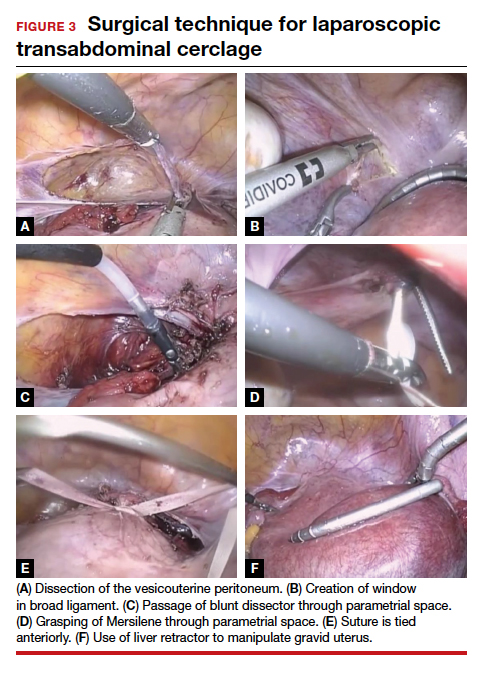

The first step of the surgery involves dissecting the vesicouterine peritoneum in order to move the bladder inferiorly (FIGURE 3A). Uterine arteries are then identified lateral to the cervix as part of this dissection, and a window is created in the inferior aspect of the broad ligament just anterior and lateral to the insertion of the uterosacral ligaments onto the uterus, with care taken to avoid the uterine vessels superiorly (FIGURE 3B). Two 5-mm Mersilene tape sutures are then tied together to create 1 suture with a needle at each end. This is then passed into the abdomen, and 1 needle is passed through the parametrial space at the level of the internal os inferior to the uterine vessels on 1 side of the uterus while the other needle is passed through the parametrial space on the opposite side.

Alternatively, rather than using the suture needles, a blunt dissector can be passed through this same space bilaterally (FIGURE 3C) via the suprapubic port and can pull the Mersilene tape through the parametrial space (FIGURE 3D). The suture is then tied anterior at the level of the internal os intracorporally (FIGURE 3E), and the needles are cut off the suture and removed from the abdomen.

To perform transabdominal cerclage when the patient is pregnant, a few modifications are needed to help with placement. First, the patient may be placed in supine position since a uterine manipulator cannot be used. Second, use of a flexible laparoscope becomes even more imperative in order to properly see around the gravid uterus. Lastly, a 5-mm laparoscopic liver retractor can be used to aid in blunt manipulation of the gravid uterus (FIGURE 3F). (The surgical video below highlights the steps to transabdominal cerclage placement in a pregnant patient.) All other port placements and steps to dissection and suture placement are the same as in interval placement.

CASE Continued: Patient pursues transabdominal cerclage

You explain to your patient that ideally the cerclage should be placed now in a laparoscopic fashion before she becomes pregnant. You then refer her to a local gynecologic surgeon who places many laparoscopic transabdominal cerclages. She undergoes the procedure, becomes pregnant, and after presenting in labor at 35 weeks’ gestation has a cesarean delivery. Her baby is born without any neonatal complications, and the patient is overjoyed with the outcome.

Management during and after pregnancy

Pregnant patients with a transabdominal cerclage are precluded from having a vaginal delivery and must deliver via cesarean. During the antepartum period, patients are managed in the same manner as those who have a transvaginal cerclage. Delivery via cesarean at the onset of regular contractions is recommended to reduce the risk of uterine rupture. In the absence of labor, scheduled cesarean is performed at term.

Our practice is to schedule cesarean delivery at 38 weeks’ gestation, although there are no data or consensus to support a specific gestational age between 37 and 39 weeks. Unlike a transvaginal cerclage, a transabdominal cerclage can be left in place for use in subsequent pregnancies. Data are limited on whether the transabdominal cerclage should be removed in women who no longer desire childbearing and whether there are long-term sequelae if the suture is left in situ.17

Continue to: Complications and risks of abdominal cerclage...

Complications and risks of abdominal cerclage

As the data suggest and our experience confirms, transabdominal cerclage is highly successful in patients who have failed a history-indicated transvaginal cerclage; however, the transabdominal approach carries a higher surgical risk. Risks include intraoperative hemorrhage, conversion to laparotomy, and a range of rare surgical and obstetric complications, such as bladder injury and PPROM.13,18

If a patient experiences a fetal loss in the first trimester, a dilation and curettage (D&C) can be performed, with good obstetric outcomes in subsequent pregnancies.19 If the patient experiences an early-to-mid second-trimester loss, some studies suggest that a dilation and evacuation (D&E) of the uterus can be done with sufficient dilation of the cervix to accommodate up to a 15-mm cannula and Sopher forceps.19 Laminaria also may be used in this process. However, no data exist regarding success of future pregnancies and transabdominal cerclage integrity after a D&E.20 If the cerclage prevents successful dilation of the cervix, the cerclage must be removed laparoscopically prior to performing the D&E.

In late second-trimester and third-trimester loss, the cerclage must be removed to allow passage of the fetus and placenta prior to a D&E or an induction of labor.20

For patients with PPROM or preterm labor, data are limited regarding management recommendations. However, in these complex cases, we strongly recommend an individualized approach and co-management with maternal-fetal medicine specialists.

CASE Resolved

The cerclage is left in place during the patient’s cesarean delivery, and her postpartum course is uneventful. She continued without complications for the next year, at which time she sees you in the office with plans to have another pregnancy later in the year. You counsel her that her abdominal cerclage will still be effective and that she can get pregnant with expectations of similar outcomes as her previous pregnancy. She thanks you for everything and reports that she hopes to return later in the year for her first prenatal visit. ●

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 142: Cerclage for the management of cervical insufficiency. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(2 pt 1): 372-379.

- Alfirevic Z, Stampalija T, Medley N. Cervical stitch (cerclage) for preventing preterm birth in singleton pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6(6):CD008991.

- Brown R, Gagnon R, Delisle M-F. No. 373—cervical insufficiency and cervical cerclage. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2019;41:233-247.

- Odibo AO, Berghella V, To MS, et al. Shirodkar versus McDonald cerclage for the prevention of preterm birth in women with short cervical length. Am J Perinatol. 2007;24: 55-60.

- Basbug A, Bayrak M, Dogan O, et al. McDonald versus modified Shirodkar rescue cerclage in women with prolapsed fetal membranes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33: 1075-1097.

- Figueroa R, Crowell R, Martinez A, et al. McDonald versus Shirodkar cervical cerclage for the prevention of preterm birth: impact of body mass index. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:3408-3414.

- Suhag A, Berghella V. Cervical cerclage. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2014;57:557-567.

- Bayrak M, Gul A, Goynumer G. Rescue cerclage when foetal membranes prolapse into the vagina. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;37:471-475.

- Drassinower D, Coviello E, Landy HJ, et al. Outcomes after periviable ultrasound-indicated cerclage. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:932-938.

- Lee KN, Whang EJ, Chang KH, et al. History-indicated cerclage: the association between previous preterm history and cerclage outcome. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2018;61:23-29. doi:10.5468/ogs.2018.61.1.23.

- Sneider K, Christiansen OB, Sundtoft IB, et al. Recurrence rates after abdominal and vaginal cerclages in women with cervical insufficiency: a validated cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295:859-866.

- Davis G, Berghella V, Talucci M, et al. Patients with a prior failed transvaginal cerclage: a comparison of obstetric outcomes with either transabdominal or transvaginal cerclage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:836-839.

- Moawad GN, Tyan P, Bracke T, et al. Systematic review of transabdominal cerclage placed via laparoscopy for the prevention of preterm birth. J Mimim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:277-286.

- Burger NB, Brölmann HAM, Einarsson JI, et al. Effectiveness of abdominal cerclage placed via laparotomy or laparoscopy: systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:696-704.

- Kim S, Hill A, Menderes G, et al. Minimally invasive abdominal cerclage compared to laparotomy: a comparison of surgical and obstetric outcomes. J Robot Surg. 2018;12:295-301.

- Dawood F, Farquharson RG. Transabdominal cerclage: preconceptual versus first trimester insertion. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;199:27-31.

- Hawkins E, Nimaroff M. Vaginal erosion of an abdominal cerclage 7 years after laparoscopic placement. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(2 pt 2 suppl 2):420-423.

- Foster TL, Moore ES, Sumners JE. Operative complications and fetal morbidity encountered in 300 prophylactic transabdominal cervical cerclage procedures by one obstetric surgeon. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;31:713-717.

- Dethier D, Lassey SC, Pilliod R, et al. Uterine evacuation in the setting of transabdominal cerclage. Contraception. 2020;101:174-177.

- Martin A, Lathrop E. Controversies in family planning: management of second-trimester losses in the setting of an abdominal cerclage. Contraception. 2013;87:728-731.

CASE A woman with recurrent pregnancy loss

A 38-year-old woman (G4P0221) presents to your office for preconception counseling. Her history is significant for the following: a spontaneous pregnancy loss at 15 weeks’ gestation; a pregnancy loss at 17 weeks secondary to preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM); a cesarean delivery at 30 weeks and 6 days’ gestation after placement of a transvaginal cerclage at 20 weeks for cervical dilation noted on physical exam (the child now has developmental delays); and most recently a delivery at 24 weeks and 4 days due to preterm labor with subsequent neonatal demise (this followed a transvaginal cerclage placed at 13 weeks and 6 days).

How would you counsel this patient?

Cervical insufficiency describes the inability of the cervix to retain a pregnancy in the absence of the signs and symptoms of clinical contractions, labor, or both in the second trimester.1 This condition affects an estimated 1% of obstetric patients and 8% of women with recurrent losses who have experienced a second-trimester loss.2

Diagnosis of cervical insufficiency is based on a history of painless cervical dilation after the first trimester with expulsion of the pregnancy in the second trimester before 24 weeks of gestation without contractions and in the absence of other pathology, such as bleeding, infection, or ruptured membranes.1 Diagnosis also can be made by noting cervical dilation on physical exam during the second trimester; more recently, short cervical length on transvaginal ultrasonography in the second trimester has been used to try to predict when a cervical cerclage may be indicated, although sonographic cervical length is more a marker for risk of preterm birth than for cervical insufficiency specifically.1,3

Given the considerable emotional and physical distress that patients experience with recurrent second-trimester losses and the significant neonatal morbidity and mortality that can occur with preterm delivery, substantial efforts are made to prevent these outcomes by treating patients with cervical insufficiency and those at risk for preterm delivery.

Transvaginal cerclage: A treatment mainstay

Standard treatment options for cervical insufficiency depend on the patient’s history. One of the treatment mainstays for women with prior second-trimester losses or preterm deliveries is transvaginal cervical cerclage. A transvaginal cerclage can be placed using either a Shirodkar technique, in which the vesicocervical mucosa is dissected and a suture is placed as close to the internal cervical os as possible, or a McDonald technique, in which a purse-string suture is placed around the cervicovaginal junction. No randomized trials have compared the effectiveness of these 2 methods, but most observational studies show no difference, and one suggests that the Shirodkar technique may be more effective in obese women specifically.4-6

Indications for transvaginal cerclage. The indication for transvaginal cerclage is based on history, physical exam, or ultrasonography.

A physical-exam indication is the most straightforward of the 3. Transvaginal cerclage placement is indicated if on physical exam in the second trimester a patient has cervical dilation without contractions or infection.1,7

A history-indicated cerclage (typically placed between 12 and 14 weeks’ gestation) is based on a cerclage having been placed in a prior pregnancy due to painless cervical dilation in the second trimester (either ultrasonography- or physical-exam indicated), and it also can be considered in the case of a history of 1 or more second-trimester pregnancy losses related to painless cervical dilation.1

More recent evidence suggests that in patients with 1 prior second-trimester loss or preterm delivery, serial sonographic cervical length can be measured safely from 16 to 24 weeks, with a cerclage being placed only if cervical length decreases to less than 25 mm. By using the ultrasonography-based indication, unnecessary history-indicated cerclages for 1 prior second-trimester or preterm birth can be avoided in more than one-half of patients (FIGURE 1).1,7

Efficacy. The effectiveness of transvaginal cerclage varies by the indication. Authors of a 2017 Cochrane review found an overall reduced risk of giving birth before 34 weeks’ gestation for any indication, with an average relative risk of 0.77.2 Other recent studies showed the following8-10:

- a 63% delivery rate after 28 weeks’ gestation for physical-exam indicated cerclages in the presence of bulging amniotic membranes

- an 86.2% delivery rate after 32 weeks’ gestation for ultrasonography-indicated cerclages

- an 86% delivery rate after 32 weeks’ gestation for a history-indicated cerclage in patients with 2 or more prior second-trimester losses.

Success rates, especially for ultrasonography- and history-indicated cerclage, are thus high. For the 14% who still fail these methods, however, a different management strategy is needed, which is where transabdominal cerclage comes into play.

Continue to: Transabdominal cerclage is an option for certain patients...

Transabdominal cerclage is an option for certain patients

In transabdominal cerclage, an abdominal approach is used to place a stitch at the cervicouterine junction. With this approach, the cerclage can reach a closer proximity to the internal os compared with the vaginal approach, providing better support of the cervical tissue (FIGURE 2).11 Whether performed via laparotomy or laparoscopy, the transabdominal cerclage procedure likely carries higher morbidity than a transvaginal approach, and cesarean delivery is required after placement.

Since transvaginal cerclage often is successful, in most cases the transabdominal approach should not be viewed as the first-line treatment for cervical insufficiency if a history-indicated transvaginal cerclage has not been attempted. For women who fail a history-indicated transvaginal cerclage, however, a transabdominal cerclage has been proven to decrease the rate of preterm delivery and PPROM compared with attempting another history-indicated transvaginal cerclage.11,12

A recent systematic review of pregnancy outcomes after transabdominal cerclage placement reported neonatal survival of 96.5% and an 83% delivery rate after 34 weeks’ gestation.13 Thus, even among a population that failed transvaginal cerclage, a transabdominal cerclage has a high success rate in providing a good pregnancy outcome (TABLE). Transabdominal cerclage also can be considered as first-line treatment in patients who had prior cervical surgery or cervical deformities that might preclude the ability to place a cerclage transvaginally.

CASE Continued: A candidate for transabdominal cerclage

Given the patient’s poor obstetric history, which includes a preterm delivery and neonatal loss despite a history-indicated cerclage, you recommend that the patient have a transabdominal cerclage placed as the procedure has been proven to increase the chances of neonatal survival and delivery after 34 weeks in women with a similar obstetric history. The patient is interested in this option and asks about how this cerclage is placed and when it would need to be placed during her next pregnancy.

Surgical technique for transabdominal cerclage placement

A transabdominal cerclage can be placed via laparotomy, laparoscopy, or robot-assisted laparoscopy. No differences in obstetric outcomes have been shown between the laparotomy and laparoscopic approaches.14,15 Given the benefits of minimally invasive surgery, a laparoscopic or robot-assisted approach is preferred when feasible.

Additionally, for ease of placement, transabdominal cerclage can be placed prior to conception—known as interval placement—or during pregnancy between 10 and 14 weeks (preferably closer to 10 weeks). Because of the increased difficulty in placing a cerclage in the gravid uterus, interval transabdominal cerclage placement is recommended when possible.13,16 Authors of one observational study noted that improved obstetric outcomes occurred with interval placement compared with cerclage placement between 9 and 10 weeks’ gestation, with a delivery rate at more than 34 weeks’ gestation in 90% versus 74% of patients, respectively.16

Continue to: Steps for interval cerclage and during pregnancy...

Steps for interval cerclage and during pregnancy

Our practice is to place transabdominal cerclage via conventional laparoscopy as an interval procedure when possible. We find no benefit in using robotic assistance.

For an interval procedure, the patient is placed in a dorsal lithotomy position, and we place a 10-mm umbilical port, 2 lateral 5-mm ports, 1 suprapubic 5-mm port, and a uterine manipulator. We use a flexible laparoscope to provide optimal visualization of the pelvis from any angle.

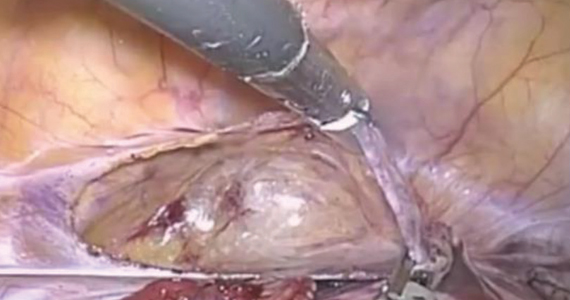

The first step of the surgery involves dissecting the vesicouterine peritoneum in order to move the bladder inferiorly (FIGURE 3A). Uterine arteries are then identified lateral to the cervix as part of this dissection, and a window is created in the inferior aspect of the broad ligament just anterior and lateral to the insertion of the uterosacral ligaments onto the uterus, with care taken to avoid the uterine vessels superiorly (FIGURE 3B). Two 5-mm Mersilene tape sutures are then tied together to create 1 suture with a needle at each end. This is then passed into the abdomen, and 1 needle is passed through the parametrial space at the level of the internal os inferior to the uterine vessels on 1 side of the uterus while the other needle is passed through the parametrial space on the opposite side.

Alternatively, rather than using the suture needles, a blunt dissector can be passed through this same space bilaterally (FIGURE 3C) via the suprapubic port and can pull the Mersilene tape through the parametrial space (FIGURE 3D). The suture is then tied anterior at the level of the internal os intracorporally (FIGURE 3E), and the needles are cut off the suture and removed from the abdomen.

To perform transabdominal cerclage when the patient is pregnant, a few modifications are needed to help with placement. First, the patient may be placed in supine position since a uterine manipulator cannot be used. Second, use of a flexible laparoscope becomes even more imperative in order to properly see around the gravid uterus. Lastly, a 5-mm laparoscopic liver retractor can be used to aid in blunt manipulation of the gravid uterus (FIGURE 3F). (The surgical video below highlights the steps to transabdominal cerclage placement in a pregnant patient.) All other port placements and steps to dissection and suture placement are the same as in interval placement.

CASE Continued: Patient pursues transabdominal cerclage

You explain to your patient that ideally the cerclage should be placed now in a laparoscopic fashion before she becomes pregnant. You then refer her to a local gynecologic surgeon who places many laparoscopic transabdominal cerclages. She undergoes the procedure, becomes pregnant, and after presenting in labor at 35 weeks’ gestation has a cesarean delivery. Her baby is born without any neonatal complications, and the patient is overjoyed with the outcome.

Management during and after pregnancy

Pregnant patients with a transabdominal cerclage are precluded from having a vaginal delivery and must deliver via cesarean. During the antepartum period, patients are managed in the same manner as those who have a transvaginal cerclage. Delivery via cesarean at the onset of regular contractions is recommended to reduce the risk of uterine rupture. In the absence of labor, scheduled cesarean is performed at term.

Our practice is to schedule cesarean delivery at 38 weeks’ gestation, although there are no data or consensus to support a specific gestational age between 37 and 39 weeks. Unlike a transvaginal cerclage, a transabdominal cerclage can be left in place for use in subsequent pregnancies. Data are limited on whether the transabdominal cerclage should be removed in women who no longer desire childbearing and whether there are long-term sequelae if the suture is left in situ.17

Continue to: Complications and risks of abdominal cerclage...

Complications and risks of abdominal cerclage

As the data suggest and our experience confirms, transabdominal cerclage is highly successful in patients who have failed a history-indicated transvaginal cerclage; however, the transabdominal approach carries a higher surgical risk. Risks include intraoperative hemorrhage, conversion to laparotomy, and a range of rare surgical and obstetric complications, such as bladder injury and PPROM.13,18

If a patient experiences a fetal loss in the first trimester, a dilation and curettage (D&C) can be performed, with good obstetric outcomes in subsequent pregnancies.19 If the patient experiences an early-to-mid second-trimester loss, some studies suggest that a dilation and evacuation (D&E) of the uterus can be done with sufficient dilation of the cervix to accommodate up to a 15-mm cannula and Sopher forceps.19 Laminaria also may be used in this process. However, no data exist regarding success of future pregnancies and transabdominal cerclage integrity after a D&E.20 If the cerclage prevents successful dilation of the cervix, the cerclage must be removed laparoscopically prior to performing the D&E.

In late second-trimester and third-trimester loss, the cerclage must be removed to allow passage of the fetus and placenta prior to a D&E or an induction of labor.20

For patients with PPROM or preterm labor, data are limited regarding management recommendations. However, in these complex cases, we strongly recommend an individualized approach and co-management with maternal-fetal medicine specialists.

CASE Resolved

The cerclage is left in place during the patient’s cesarean delivery, and her postpartum course is uneventful. She continued without complications for the next year, at which time she sees you in the office with plans to have another pregnancy later in the year. You counsel her that her abdominal cerclage will still be effective and that she can get pregnant with expectations of similar outcomes as her previous pregnancy. She thanks you for everything and reports that she hopes to return later in the year for her first prenatal visit. ●

CASE A woman with recurrent pregnancy loss

A 38-year-old woman (G4P0221) presents to your office for preconception counseling. Her history is significant for the following: a spontaneous pregnancy loss at 15 weeks’ gestation; a pregnancy loss at 17 weeks secondary to preterm premature rupture of membranes (PPROM); a cesarean delivery at 30 weeks and 6 days’ gestation after placement of a transvaginal cerclage at 20 weeks for cervical dilation noted on physical exam (the child now has developmental delays); and most recently a delivery at 24 weeks and 4 days due to preterm labor with subsequent neonatal demise (this followed a transvaginal cerclage placed at 13 weeks and 6 days).

How would you counsel this patient?

Cervical insufficiency describes the inability of the cervix to retain a pregnancy in the absence of the signs and symptoms of clinical contractions, labor, or both in the second trimester.1 This condition affects an estimated 1% of obstetric patients and 8% of women with recurrent losses who have experienced a second-trimester loss.2

Diagnosis of cervical insufficiency is based on a history of painless cervical dilation after the first trimester with expulsion of the pregnancy in the second trimester before 24 weeks of gestation without contractions and in the absence of other pathology, such as bleeding, infection, or ruptured membranes.1 Diagnosis also can be made by noting cervical dilation on physical exam during the second trimester; more recently, short cervical length on transvaginal ultrasonography in the second trimester has been used to try to predict when a cervical cerclage may be indicated, although sonographic cervical length is more a marker for risk of preterm birth than for cervical insufficiency specifically.1,3

Given the considerable emotional and physical distress that patients experience with recurrent second-trimester losses and the significant neonatal morbidity and mortality that can occur with preterm delivery, substantial efforts are made to prevent these outcomes by treating patients with cervical insufficiency and those at risk for preterm delivery.

Transvaginal cerclage: A treatment mainstay

Standard treatment options for cervical insufficiency depend on the patient’s history. One of the treatment mainstays for women with prior second-trimester losses or preterm deliveries is transvaginal cervical cerclage. A transvaginal cerclage can be placed using either a Shirodkar technique, in which the vesicocervical mucosa is dissected and a suture is placed as close to the internal cervical os as possible, or a McDonald technique, in which a purse-string suture is placed around the cervicovaginal junction. No randomized trials have compared the effectiveness of these 2 methods, but most observational studies show no difference, and one suggests that the Shirodkar technique may be more effective in obese women specifically.4-6

Indications for transvaginal cerclage. The indication for transvaginal cerclage is based on history, physical exam, or ultrasonography.

A physical-exam indication is the most straightforward of the 3. Transvaginal cerclage placement is indicated if on physical exam in the second trimester a patient has cervical dilation without contractions or infection.1,7

A history-indicated cerclage (typically placed between 12 and 14 weeks’ gestation) is based on a cerclage having been placed in a prior pregnancy due to painless cervical dilation in the second trimester (either ultrasonography- or physical-exam indicated), and it also can be considered in the case of a history of 1 or more second-trimester pregnancy losses related to painless cervical dilation.1

More recent evidence suggests that in patients with 1 prior second-trimester loss or preterm delivery, serial sonographic cervical length can be measured safely from 16 to 24 weeks, with a cerclage being placed only if cervical length decreases to less than 25 mm. By using the ultrasonography-based indication, unnecessary history-indicated cerclages for 1 prior second-trimester or preterm birth can be avoided in more than one-half of patients (FIGURE 1).1,7

Efficacy. The effectiveness of transvaginal cerclage varies by the indication. Authors of a 2017 Cochrane review found an overall reduced risk of giving birth before 34 weeks’ gestation for any indication, with an average relative risk of 0.77.2 Other recent studies showed the following8-10:

- a 63% delivery rate after 28 weeks’ gestation for physical-exam indicated cerclages in the presence of bulging amniotic membranes

- an 86.2% delivery rate after 32 weeks’ gestation for ultrasonography-indicated cerclages

- an 86% delivery rate after 32 weeks’ gestation for a history-indicated cerclage in patients with 2 or more prior second-trimester losses.

Success rates, especially for ultrasonography- and history-indicated cerclage, are thus high. For the 14% who still fail these methods, however, a different management strategy is needed, which is where transabdominal cerclage comes into play.

Continue to: Transabdominal cerclage is an option for certain patients...

Transabdominal cerclage is an option for certain patients

In transabdominal cerclage, an abdominal approach is used to place a stitch at the cervicouterine junction. With this approach, the cerclage can reach a closer proximity to the internal os compared with the vaginal approach, providing better support of the cervical tissue (FIGURE 2).11 Whether performed via laparotomy or laparoscopy, the transabdominal cerclage procedure likely carries higher morbidity than a transvaginal approach, and cesarean delivery is required after placement.

Since transvaginal cerclage often is successful, in most cases the transabdominal approach should not be viewed as the first-line treatment for cervical insufficiency if a history-indicated transvaginal cerclage has not been attempted. For women who fail a history-indicated transvaginal cerclage, however, a transabdominal cerclage has been proven to decrease the rate of preterm delivery and PPROM compared with attempting another history-indicated transvaginal cerclage.11,12

A recent systematic review of pregnancy outcomes after transabdominal cerclage placement reported neonatal survival of 96.5% and an 83% delivery rate after 34 weeks’ gestation.13 Thus, even among a population that failed transvaginal cerclage, a transabdominal cerclage has a high success rate in providing a good pregnancy outcome (TABLE). Transabdominal cerclage also can be considered as first-line treatment in patients who had prior cervical surgery or cervical deformities that might preclude the ability to place a cerclage transvaginally.

CASE Continued: A candidate for transabdominal cerclage

Given the patient’s poor obstetric history, which includes a preterm delivery and neonatal loss despite a history-indicated cerclage, you recommend that the patient have a transabdominal cerclage placed as the procedure has been proven to increase the chances of neonatal survival and delivery after 34 weeks in women with a similar obstetric history. The patient is interested in this option and asks about how this cerclage is placed and when it would need to be placed during her next pregnancy.

Surgical technique for transabdominal cerclage placement

A transabdominal cerclage can be placed via laparotomy, laparoscopy, or robot-assisted laparoscopy. No differences in obstetric outcomes have been shown between the laparotomy and laparoscopic approaches.14,15 Given the benefits of minimally invasive surgery, a laparoscopic or robot-assisted approach is preferred when feasible.

Additionally, for ease of placement, transabdominal cerclage can be placed prior to conception—known as interval placement—or during pregnancy between 10 and 14 weeks (preferably closer to 10 weeks). Because of the increased difficulty in placing a cerclage in the gravid uterus, interval transabdominal cerclage placement is recommended when possible.13,16 Authors of one observational study noted that improved obstetric outcomes occurred with interval placement compared with cerclage placement between 9 and 10 weeks’ gestation, with a delivery rate at more than 34 weeks’ gestation in 90% versus 74% of patients, respectively.16

Continue to: Steps for interval cerclage and during pregnancy...

Steps for interval cerclage and during pregnancy

Our practice is to place transabdominal cerclage via conventional laparoscopy as an interval procedure when possible. We find no benefit in using robotic assistance.

For an interval procedure, the patient is placed in a dorsal lithotomy position, and we place a 10-mm umbilical port, 2 lateral 5-mm ports, 1 suprapubic 5-mm port, and a uterine manipulator. We use a flexible laparoscope to provide optimal visualization of the pelvis from any angle.

The first step of the surgery involves dissecting the vesicouterine peritoneum in order to move the bladder inferiorly (FIGURE 3A). Uterine arteries are then identified lateral to the cervix as part of this dissection, and a window is created in the inferior aspect of the broad ligament just anterior and lateral to the insertion of the uterosacral ligaments onto the uterus, with care taken to avoid the uterine vessels superiorly (FIGURE 3B). Two 5-mm Mersilene tape sutures are then tied together to create 1 suture with a needle at each end. This is then passed into the abdomen, and 1 needle is passed through the parametrial space at the level of the internal os inferior to the uterine vessels on 1 side of the uterus while the other needle is passed through the parametrial space on the opposite side.

Alternatively, rather than using the suture needles, a blunt dissector can be passed through this same space bilaterally (FIGURE 3C) via the suprapubic port and can pull the Mersilene tape through the parametrial space (FIGURE 3D). The suture is then tied anterior at the level of the internal os intracorporally (FIGURE 3E), and the needles are cut off the suture and removed from the abdomen.

To perform transabdominal cerclage when the patient is pregnant, a few modifications are needed to help with placement. First, the patient may be placed in supine position since a uterine manipulator cannot be used. Second, use of a flexible laparoscope becomes even more imperative in order to properly see around the gravid uterus. Lastly, a 5-mm laparoscopic liver retractor can be used to aid in blunt manipulation of the gravid uterus (FIGURE 3F). (The surgical video below highlights the steps to transabdominal cerclage placement in a pregnant patient.) All other port placements and steps to dissection and suture placement are the same as in interval placement.

CASE Continued: Patient pursues transabdominal cerclage

You explain to your patient that ideally the cerclage should be placed now in a laparoscopic fashion before she becomes pregnant. You then refer her to a local gynecologic surgeon who places many laparoscopic transabdominal cerclages. She undergoes the procedure, becomes pregnant, and after presenting in labor at 35 weeks’ gestation has a cesarean delivery. Her baby is born without any neonatal complications, and the patient is overjoyed with the outcome.

Management during and after pregnancy

Pregnant patients with a transabdominal cerclage are precluded from having a vaginal delivery and must deliver via cesarean. During the antepartum period, patients are managed in the same manner as those who have a transvaginal cerclage. Delivery via cesarean at the onset of regular contractions is recommended to reduce the risk of uterine rupture. In the absence of labor, scheduled cesarean is performed at term.

Our practice is to schedule cesarean delivery at 38 weeks’ gestation, although there are no data or consensus to support a specific gestational age between 37 and 39 weeks. Unlike a transvaginal cerclage, a transabdominal cerclage can be left in place for use in subsequent pregnancies. Data are limited on whether the transabdominal cerclage should be removed in women who no longer desire childbearing and whether there are long-term sequelae if the suture is left in situ.17

Continue to: Complications and risks of abdominal cerclage...

Complications and risks of abdominal cerclage

As the data suggest and our experience confirms, transabdominal cerclage is highly successful in patients who have failed a history-indicated transvaginal cerclage; however, the transabdominal approach carries a higher surgical risk. Risks include intraoperative hemorrhage, conversion to laparotomy, and a range of rare surgical and obstetric complications, such as bladder injury and PPROM.13,18

If a patient experiences a fetal loss in the first trimester, a dilation and curettage (D&C) can be performed, with good obstetric outcomes in subsequent pregnancies.19 If the patient experiences an early-to-mid second-trimester loss, some studies suggest that a dilation and evacuation (D&E) of the uterus can be done with sufficient dilation of the cervix to accommodate up to a 15-mm cannula and Sopher forceps.19 Laminaria also may be used in this process. However, no data exist regarding success of future pregnancies and transabdominal cerclage integrity after a D&E.20 If the cerclage prevents successful dilation of the cervix, the cerclage must be removed laparoscopically prior to performing the D&E.

In late second-trimester and third-trimester loss, the cerclage must be removed to allow passage of the fetus and placenta prior to a D&E or an induction of labor.20

For patients with PPROM or preterm labor, data are limited regarding management recommendations. However, in these complex cases, we strongly recommend an individualized approach and co-management with maternal-fetal medicine specialists.

CASE Resolved

The cerclage is left in place during the patient’s cesarean delivery, and her postpartum course is uneventful. She continued without complications for the next year, at which time she sees you in the office with plans to have another pregnancy later in the year. You counsel her that her abdominal cerclage will still be effective and that she can get pregnant with expectations of similar outcomes as her previous pregnancy. She thanks you for everything and reports that she hopes to return later in the year for her first prenatal visit. ●

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 142: Cerclage for the management of cervical insufficiency. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(2 pt 1): 372-379.

- Alfirevic Z, Stampalija T, Medley N. Cervical stitch (cerclage) for preventing preterm birth in singleton pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6(6):CD008991.

- Brown R, Gagnon R, Delisle M-F. No. 373—cervical insufficiency and cervical cerclage. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2019;41:233-247.

- Odibo AO, Berghella V, To MS, et al. Shirodkar versus McDonald cerclage for the prevention of preterm birth in women with short cervical length. Am J Perinatol. 2007;24: 55-60.

- Basbug A, Bayrak M, Dogan O, et al. McDonald versus modified Shirodkar rescue cerclage in women with prolapsed fetal membranes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33: 1075-1097.

- Figueroa R, Crowell R, Martinez A, et al. McDonald versus Shirodkar cervical cerclage for the prevention of preterm birth: impact of body mass index. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:3408-3414.

- Suhag A, Berghella V. Cervical cerclage. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2014;57:557-567.

- Bayrak M, Gul A, Goynumer G. Rescue cerclage when foetal membranes prolapse into the vagina. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;37:471-475.

- Drassinower D, Coviello E, Landy HJ, et al. Outcomes after periviable ultrasound-indicated cerclage. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:932-938.

- Lee KN, Whang EJ, Chang KH, et al. History-indicated cerclage: the association between previous preterm history and cerclage outcome. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2018;61:23-29. doi:10.5468/ogs.2018.61.1.23.

- Sneider K, Christiansen OB, Sundtoft IB, et al. Recurrence rates after abdominal and vaginal cerclages in women with cervical insufficiency: a validated cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295:859-866.

- Davis G, Berghella V, Talucci M, et al. Patients with a prior failed transvaginal cerclage: a comparison of obstetric outcomes with either transabdominal or transvaginal cerclage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:836-839.

- Moawad GN, Tyan P, Bracke T, et al. Systematic review of transabdominal cerclage placed via laparoscopy for the prevention of preterm birth. J Mimim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:277-286.

- Burger NB, Brölmann HAM, Einarsson JI, et al. Effectiveness of abdominal cerclage placed via laparotomy or laparoscopy: systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:696-704.

- Kim S, Hill A, Menderes G, et al. Minimally invasive abdominal cerclage compared to laparotomy: a comparison of surgical and obstetric outcomes. J Robot Surg. 2018;12:295-301.

- Dawood F, Farquharson RG. Transabdominal cerclage: preconceptual versus first trimester insertion. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;199:27-31.

- Hawkins E, Nimaroff M. Vaginal erosion of an abdominal cerclage 7 years after laparoscopic placement. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(2 pt 2 suppl 2):420-423.

- Foster TL, Moore ES, Sumners JE. Operative complications and fetal morbidity encountered in 300 prophylactic transabdominal cervical cerclage procedures by one obstetric surgeon. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;31:713-717.

- Dethier D, Lassey SC, Pilliod R, et al. Uterine evacuation in the setting of transabdominal cerclage. Contraception. 2020;101:174-177.

- Martin A, Lathrop E. Controversies in family planning: management of second-trimester losses in the setting of an abdominal cerclage. Contraception. 2013;87:728-731.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG practice bulletin no. 142: Cerclage for the management of cervical insufficiency. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(2 pt 1): 372-379.

- Alfirevic Z, Stampalija T, Medley N. Cervical stitch (cerclage) for preventing preterm birth in singleton pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6(6):CD008991.

- Brown R, Gagnon R, Delisle M-F. No. 373—cervical insufficiency and cervical cerclage. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2019;41:233-247.

- Odibo AO, Berghella V, To MS, et al. Shirodkar versus McDonald cerclage for the prevention of preterm birth in women with short cervical length. Am J Perinatol. 2007;24: 55-60.

- Basbug A, Bayrak M, Dogan O, et al. McDonald versus modified Shirodkar rescue cerclage in women with prolapsed fetal membranes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020;33: 1075-1097.

- Figueroa R, Crowell R, Martinez A, et al. McDonald versus Shirodkar cervical cerclage for the prevention of preterm birth: impact of body mass index. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:3408-3414.

- Suhag A, Berghella V. Cervical cerclage. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2014;57:557-567.

- Bayrak M, Gul A, Goynumer G. Rescue cerclage when foetal membranes prolapse into the vagina. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2017;37:471-475.

- Drassinower D, Coviello E, Landy HJ, et al. Outcomes after periviable ultrasound-indicated cerclage. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019;32:932-938.

- Lee KN, Whang EJ, Chang KH, et al. History-indicated cerclage: the association between previous preterm history and cerclage outcome. Obstet Gynecol Sci. 2018;61:23-29. doi:10.5468/ogs.2018.61.1.23.

- Sneider K, Christiansen OB, Sundtoft IB, et al. Recurrence rates after abdominal and vaginal cerclages in women with cervical insufficiency: a validated cohort study. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2017;295:859-866.

- Davis G, Berghella V, Talucci M, et al. Patients with a prior failed transvaginal cerclage: a comparison of obstetric outcomes with either transabdominal or transvaginal cerclage. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:836-839.

- Moawad GN, Tyan P, Bracke T, et al. Systematic review of transabdominal cerclage placed via laparoscopy for the prevention of preterm birth. J Mimim Invasive Gynecol. 2018;25:277-286.

- Burger NB, Brölmann HAM, Einarsson JI, et al. Effectiveness of abdominal cerclage placed via laparotomy or laparoscopy: systematic review. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2011;18:696-704.

- Kim S, Hill A, Menderes G, et al. Minimally invasive abdominal cerclage compared to laparotomy: a comparison of surgical and obstetric outcomes. J Robot Surg. 2018;12:295-301.

- Dawood F, Farquharson RG. Transabdominal cerclage: preconceptual versus first trimester insertion. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2016;199:27-31.

- Hawkins E, Nimaroff M. Vaginal erosion of an abdominal cerclage 7 years after laparoscopic placement. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;123(2 pt 2 suppl 2):420-423.

- Foster TL, Moore ES, Sumners JE. Operative complications and fetal morbidity encountered in 300 prophylactic transabdominal cervical cerclage procedures by one obstetric surgeon. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2011;31:713-717.

- Dethier D, Lassey SC, Pilliod R, et al. Uterine evacuation in the setting of transabdominal cerclage. Contraception. 2020;101:174-177.

- Martin A, Lathrop E. Controversies in family planning: management of second-trimester losses in the setting of an abdominal cerclage. Contraception. 2013;87:728-731.

Applying single-incision laparoscopic surgery to gyn practice: What’s involved

- Update on minimally invasive surgery

Amy Garcia, MD (April 2011) - 10 practical, evidence-based suggestions to improve your minimally invasive surgical skills now

Catherine A. Matthews, MD (April 2011)

The benefits of minimally invasive surgery—including less pain, faster recovery, and improved cosmesis—are well known.1,2 Standard laparotomy has been replaced by multiple-port operative laparoscopy for a great array of procedures, and advances in medical technology allow for a minimally invasive surgical approach even when a surgeon is faced with complex pathology.

Single-port laparoscopic surgery (SPLS) represents the latest advance in minimally invasive surgery. Using flexible endoscopes and articulating instruments, the surgeon can complete complex procedures through a single 2-cm incision in the abdomen. The incision is usually placed in the umbilicus, where it is easily hidden.3-8

Since the first laparoscopic hysterectomy through a single incision was performed 20 years ago, SPLS has been used successfully to perform nephrectomy, prostatectomy, hemicolectomy, cholecystectomy, splenectomy, intussusception reduction, gastrostomy tube placement, thoracoscopic lung biopsy, thoracoscopic decortication, and appendectomy.4-7

In gynecology, SPLS has been used to perform oophorectomy, salpingectomy, bilateral tubal ligation, ovarian cystectomy, surgical treatment of ectopic pregnancy, and both total and partial hysterectomy.7-11 At least two recent studies have concluded that SPLS is an acceptable way to treat many benign and malignant gynecologic conditions that are currently treated using multiport laparoscopy.3,11

This article outlines our approach to SPLS in the gynecologic patient and provides an overview of instrumentation, with the aim of allowing you to consider whether this approach might be feasible in your surgical practice, at your institution.

Unique setup required

When SPLS is performed through the umbilicus, the instruments must be held closer to the midline and more cephalad than during conventional laparoscopy to permit adequate visualization and manipulation. For this reason, the surgeon needs to assume a position higher over the torso and thorax of the patient, and both of the patient’s arms need to be tucked. Place the patient in a dorsal lithotomy position with a uterine manipulator in place to facilitate surgery—even when the uterus will be preserved and surgery involves only the adnexae.

With appropriate equipment and positioning, visualization and manipulation of anatomy are comparable to those of standard multiport laparoscopy.

New instruments simplify SPLS

Innovative surgical instruments allow for appropriate hand positioning outside the abdomen and minimize the internal collision of instruments brought through a single midline incision (FIGURE 1). A variety of single-port options are available, each with a unique patented design and method of insertion. In fact, the development of ports with multiple instrument channels has revolutionized SPLS.

FIGURE 1 Setup

Desired triangulation of instruments in SPLS setup.Before true single ports became available, it was necessary to place three 5-mm low-profile trocars in the fascia at three separate sites through a single skin incision. Pneumoperitoneum was established with a Veress needle, but the fascial incisions gradually merged with repeated cannula manipulation, producing air leaks.

Today, multiple-channel ports are placed using an open technique into a single skin and fascial incision. Trocars and instruments of varying size can be exchanged with ease without jeopardizing pneumoperitoneum.

Among the options:

- the SILS Port (Covidien) – a soft, flexible, three-channel port that allows for placement of blunt trocars ranging in size from 5 mm to 12 mm (FIGURE 2)

- the TriPort (Olympus America) – two flexible rings joined by a sleeve and multiple-channel port (FIGURE 3)

- GelPOINT Advanced Access Platform (Applied Medical) – a system constructed of synthetic gel material and consisting of a “GelSeal” cap, cannulas, and seals to accommodate 5-mm to 10-mm instrumentation (FIGURE 4).

We have found that all three devices allow for good range of motion while maintaining pneumoperitoneum.

(A recent article from Korea reports an inventive technique to perform single-incision laparoscopy using standard instrumentation: The authors fitted a self-retaining ring retractor with a surgical glove that had three of the fingers cut off and replaced by trocars.12)

FIGURE 2 SILS Port

The SILS Port is a soft, flexible, three-channel port that allows for placement of blunt trocars ranging in size from 5 mm to 12 mm.

FIGURE 3 TriPort

The TriPort system comprises two flexible rings joined by a sleeve and multiple-channel port.

FIGURE 4 GelPOINT

The GelPOINT Advanced Access Platform is constructed of synthetic gel material and accommodates 5-mm to 10-mm instrumentation.

A flexible laparoscope improves visualization

The ability to visualize the operative field is vital to any surgery, including SPLS. Use of a flexible laparoscope facilitates uncompromised visualization of the entire pelvis (FIGURE 5). Outside the abdomen, the flexible camera can be held laterally and away from the midline to help reduce the clashing of instruments and hands.

FIGURE 5 Flexible-tip laparoscope

A flexible-tip laparoscope ensures good visualization of the surgical field.If a flexible laparoscope is not available, a rigid 30-degree or 45-degree angled scope can be used, although visualization may be limited and adequate triangulation of instruments may be difficult to achieve.

When using a rigid laparoscope, a light cord that inserts into the back of the camera is necessary; otherwise, a 90-degree light cord adapter can be purchased.

Design enhancements facilitate coordination of instruments

One of the disadvantages of SPLS has been the restriction of movement that arises because of the close proximity of instruments and instrument handles. The latest designs have made articulation possible for tissue graspers, scissors, vessel sealers, and scopes.9,10 The value of articulation is apparent inside the abdomen, where it allows perfect positioning of the area of dissection. Outside the abdomen, the handles can be arranged in an angled pattern to allow the surgeon and assistant to operate comfortably (FIGURE 1).

In a four-handed procedure, one hand is on the camera, one on the uterine manipulator, and the remaining two hands operate the articulating grasper, vessel sealer, or needle driver, depending on the task.

Standard straight instruments can also be used for portions of the procedure.

Dissection and hemostasis are achieved in a manner similar to that of conventional laparoscopy. Our instrument of choice is an enhanced bipolar instrument, although harmonic and traditional biopolar energy can be used as well, depending on the preference of the surgeon.

The latest instruments are designed to dissect, cauterize, and cut, thereby decreasing the number of instrument exchanges necessary.

With the right aids, suturing can be simplified

Suturing through a single port can be a challenge. When possible, closure of the vaginal cuff following a total laparoscopic or laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy should be performed from below. When endoscopic suturing is required, standard suturing using both intracorporeal and extracorporeal methods is possible.

Suturing aids such as the Endo Stitch (Covidien) or Lapra-Ty (Ethicon) are helpful. One author recommends Quill bidirectional, self-retaining suture with barbs (Angiotech) to avoid the need for knot-tying.6 (For more on self-retaining suture, see “Barbed suture, now in the toolbox of minimally invasive gyn surgery,” by Jon I. Einarsson, MD, MPH, and James A. Greenberg, MD, in the September 2009 issue at obgmanagement.com.)

The MiniLap (Stryker) is a 2.3-mm grasper that is inserted percutaneously directly through the abdominal wall without an incision. It can be used to set the needle on the needle driver or manipulate tissue while suturing. The resulting skin incision is barely visible and does not require closure.

Options are varied for specimen removal

Small specimens can be removed directly through a single-port system that has been opened, or they can be extracted after the system is removed, with rapid desufflation (FIGURE 6).

FIGURE 6 Single-incision oophorectomy

An ovary and tube removed through a single incision using the A) TriPort and B) SILS Port systems.Compared with conventional laparoscopy, the larger incision associated with single-port surgery facilitates specimen removal. Larger or potentially malignant specimens can be placed into an EndoCatch bag (Covidien) inserted through the single-incision 10-mm cannula (FIGURE 7).

FIGURE 7 Specimen removal

In this case, the specimen was placed in a 10-mm EndoCatch bag and removed through the 10-mm cannula of the SILS Port.In total laparoscopic hysterectomy or laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy, the uterus is removed through the vagina. In supracervical hysterectomy, a small uterus can be removed through the cul-de-sac or directly through the single incision after placement in a bag.

When morcellation is required, the instrument can be placed through the cul-desac, cervix, or a single port. The morcellator can be placed directly through the SPLS port while utilizing the flexible scope in an angled direction (looking back toward the morcellator) for complete visualization (note: Covidien does not recommend this usage).

Transcervical tissue morcellation has also been described. In this approach, the cervix is dilated once the uterine body has been amputated, and the tissue morcellator is inserted through the cervix while the surgeon maintains visualization from above.6,13

How to master the technique

Many patients desire SPLS for its superior cosmetic outcome, but the approach may not always be appropriate. Depending on the procedure and characteristics of the patient (TABLE), multiple-port laparoscopy may be a better option. When a surgeon first attempts SPLS, we recommend that it be limited to the treatment of adnexal pathology only.

In your early SPlS cases, look for these patient characteristics

|

By using the techniques described in this article and selecting patients carefully, the surgeon can develop expertise in SPLS.11,14 During the learning process, the use of additional ports or Mini-Lap instruments (Stryker) can reduce the challenges of more difficult procedures and should be considered without reservation, as should the use of articulating accessory instruments and flexible or angled laparoscopes.

Although the clinical benefits of SPLS have yet to be determined, the cosmetic advantage of a single, hidden, umbilical incision likely increases patient satisfaction.

Clearly, the goal of SPLS is to use technology in a way that offers all of the benefits of traditional multiport laparoscopy without any of the limitations. Further study is required to determine whether SPLS meets this standard and, more important, whether it has any advantages over conventional techniques.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

1. Medeiros LR, Rosa DD, Bozzerri MC, et al. Laparoscopy versus laparotomy for benign ovarian tumour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;(2):CD004751.-

2. Chapron C, Fauconnier A, Goffinet F, Breart G, Dubuisson JB. Laparoscopic surgery is not inherently dangerous for patients presenting with benign gynecological pathology. Results of a metaanalysis. Hum Reprod. 2002;17(5):1334-1342.

3. Fader AN, Escobar PF. Laparoendoscopic single-site surgery (LESS) in gynecologic oncology: technique and initial report. Gynecol Oncol. 2009;114(2):157-161.

4. Pelosi MA, Pelosi MA 3rd. Laparoscopic hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy using a single umbilical puncture. N J Med. 1991;88(1):721-726.

5. Curcillo PG, King SA, Podolsky ER, Rottman SJ. Single port access (SPA) minimal access surgery through a single incision. Surg Technol Int. 2009;18:19-25.

6. Romanelli JR, Earle DB. Single-port laparoscopic surgery: an overview. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(7):1419-1427.

7. Ponsky TA. Single port laparoscopic cholecystectomy in adults and children: tools and techniques. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;209(5):e1-6.

8. Kim YW. Single port transumbilical myomectomy and ovarian cystectomy. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2009;16(6 suppl):S74.-

9. Ghezzi F, Cromi A, Fasola M, Bolis P. One-trocar salpingectomy for the treatment of tubal pregnancy: a “marionette-like” technique. BJOG. 2005;112(10):1417-1419.

10. Lim MC, Kim TJ, Kang S, Bae DS, Park SY, Seo SS. Embryonic natural orifice transumbilical endoscopic surgery (E-NOTES) for adnexal tumors. Surg Endosc. 2009;23(11):2445-2449.

11. Escobar PF, Starks DC, Fader AN, et al. Single-port risk-reducing salpingo-oophorectomy with and without hysterectomy: surgical outcomes and learning curve analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119(1):43-47.

12. Jeon HG, Jeong W, Oh CK. Initial experience with 50 laparoendoscopic single site surgeries using a homemade, single port device at a single center. J Urol. 2010;183(5):1866-1871.

13. Yoon G, Kim TJ, Lee YY, et al. Single port access subtotal hysterectomy with transcervical morcellation: a pilot study. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2010;17(1):78-81.

14. Ghomi A, Littman P, Prasad A, et al. Assessing the learning curve for laparoscopic supracervical hysterectomy. JSLS. 2007;11(2):190-194.

- Update on minimally invasive surgery

Amy Garcia, MD (April 2011) - 10 practical, evidence-based suggestions to improve your minimally invasive surgical skills now

Catherine A. Matthews, MD (April 2011)

The benefits of minimally invasive surgery—including less pain, faster recovery, and improved cosmesis—are well known.1,2 Standard laparotomy has been replaced by multiple-port operative laparoscopy for a great array of procedures, and advances in medical technology allow for a minimally invasive surgical approach even when a surgeon is faced with complex pathology.

Single-port laparoscopic surgery (SPLS) represents the latest advance in minimally invasive surgery. Using flexible endoscopes and articulating instruments, the surgeon can complete complex procedures through a single 2-cm incision in the abdomen. The incision is usually placed in the umbilicus, where it is easily hidden.3-8

Since the first laparoscopic hysterectomy through a single incision was performed 20 years ago, SPLS has been used successfully to perform nephrectomy, prostatectomy, hemicolectomy, cholecystectomy, splenectomy, intussusception reduction, gastrostomy tube placement, thoracoscopic lung biopsy, thoracoscopic decortication, and appendectomy.4-7

In gynecology, SPLS has been used to perform oophorectomy, salpingectomy, bilateral tubal ligation, ovarian cystectomy, surgical treatment of ectopic pregnancy, and both total and partial hysterectomy.7-11 At least two recent studies have concluded that SPLS is an acceptable way to treat many benign and malignant gynecologic conditions that are currently treated using multiport laparoscopy.3,11

This article outlines our approach to SPLS in the gynecologic patient and provides an overview of instrumentation, with the aim of allowing you to consider whether this approach might be feasible in your surgical practice, at your institution.

Unique setup required

When SPLS is performed through the umbilicus, the instruments must be held closer to the midline and more cephalad than during conventional laparoscopy to permit adequate visualization and manipulation. For this reason, the surgeon needs to assume a position higher over the torso and thorax of the patient, and both of the patient’s arms need to be tucked. Place the patient in a dorsal lithotomy position with a uterine manipulator in place to facilitate surgery—even when the uterus will be preserved and surgery involves only the adnexae.

With appropriate equipment and positioning, visualization and manipulation of anatomy are comparable to those of standard multiport laparoscopy.

New instruments simplify SPLS

Innovative surgical instruments allow for appropriate hand positioning outside the abdomen and minimize the internal collision of instruments brought through a single midline incision (FIGURE 1). A variety of single-port options are available, each with a unique patented design and method of insertion. In fact, the development of ports with multiple instrument channels has revolutionized SPLS.

FIGURE 1 Setup

Desired triangulation of instruments in SPLS setup.Before true single ports became available, it was necessary to place three 5-mm low-profile trocars in the fascia at three separate sites through a single skin incision. Pneumoperitoneum was established with a Veress needle, but the fascial incisions gradually merged with repeated cannula manipulation, producing air leaks.

Today, multiple-channel ports are placed using an open technique into a single skin and fascial incision. Trocars and instruments of varying size can be exchanged with ease without jeopardizing pneumoperitoneum.

Among the options:

- the SILS Port (Covidien) – a soft, flexible, three-channel port that allows for placement of blunt trocars ranging in size from 5 mm to 12 mm (FIGURE 2)

- the TriPort (Olympus America) – two flexible rings joined by a sleeve and multiple-channel port (FIGURE 3)

- GelPOINT Advanced Access Platform (Applied Medical) – a system constructed of synthetic gel material and consisting of a “GelSeal” cap, cannulas, and seals to accommodate 5-mm to 10-mm instrumentation (FIGURE 4).

We have found that all three devices allow for good range of motion while maintaining pneumoperitoneum.

(A recent article from Korea reports an inventive technique to perform single-incision laparoscopy using standard instrumentation: The authors fitted a self-retaining ring retractor with a surgical glove that had three of the fingers cut off and replaced by trocars.12)

FIGURE 2 SILS Port

The SILS Port is a soft, flexible, three-channel port that allows for placement of blunt trocars ranging in size from 5 mm to 12 mm.

FIGURE 3 TriPort

The TriPort system comprises two flexible rings joined by a sleeve and multiple-channel port.

FIGURE 4 GelPOINT

The GelPOINT Advanced Access Platform is constructed of synthetic gel material and accommodates 5-mm to 10-mm instrumentation.

A flexible laparoscope improves visualization

The ability to visualize the operative field is vital to any surgery, including SPLS. Use of a flexible laparoscope facilitates uncompromised visualization of the entire pelvis (FIGURE 5). Outside the abdomen, the flexible camera can be held laterally and away from the midline to help reduce the clashing of instruments and hands.

FIGURE 5 Flexible-tip laparoscope

A flexible-tip laparoscope ensures good visualization of the surgical field.If a flexible laparoscope is not available, a rigid 30-degree or 45-degree angled scope can be used, although visualization may be limited and adequate triangulation of instruments may be difficult to achieve.

When using a rigid laparoscope, a light cord that inserts into the back of the camera is necessary; otherwise, a 90-degree light cord adapter can be purchased.

Design enhancements facilitate coordination of instruments

One of the disadvantages of SPLS has been the restriction of movement that arises because of the close proximity of instruments and instrument handles. The latest designs have made articulation possible for tissue graspers, scissors, vessel sealers, and scopes.9,10 The value of articulation is apparent inside the abdomen, where it allows perfect positioning of the area of dissection. Outside the abdomen, the handles can be arranged in an angled pattern to allow the surgeon and assistant to operate comfortably (FIGURE 1).

In a four-handed procedure, one hand is on the camera, one on the uterine manipulator, and the remaining two hands operate the articulating grasper, vessel sealer, or needle driver, depending on the task.

Standard straight instruments can also be used for portions of the procedure.

Dissection and hemostasis are achieved in a manner similar to that of conventional laparoscopy. Our instrument of choice is an enhanced bipolar instrument, although harmonic and traditional biopolar energy can be used as well, depending on the preference of the surgeon.

The latest instruments are designed to dissect, cauterize, and cut, thereby decreasing the number of instrument exchanges necessary.

With the right aids, suturing can be simplified

Suturing through a single port can be a challenge. When possible, closure of the vaginal cuff following a total laparoscopic or laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy should be performed from below. When endoscopic suturing is required, standard suturing using both intracorporeal and extracorporeal methods is possible.

Suturing aids such as the Endo Stitch (Covidien) or Lapra-Ty (Ethicon) are helpful. One author recommends Quill bidirectional, self-retaining suture with barbs (Angiotech) to avoid the need for knot-tying.6 (For more on self-retaining suture, see “Barbed suture, now in the toolbox of minimally invasive gyn surgery,” by Jon I. Einarsson, MD, MPH, and James A. Greenberg, MD, in the September 2009 issue at obgmanagement.com.)

The MiniLap (Stryker) is a 2.3-mm grasper that is inserted percutaneously directly through the abdominal wall without an incision. It can be used to set the needle on the needle driver or manipulate tissue while suturing. The resulting skin incision is barely visible and does not require closure.

Options are varied for specimen removal

Small specimens can be removed directly through a single-port system that has been opened, or they can be extracted after the system is removed, with rapid desufflation (FIGURE 6).

FIGURE 6 Single-incision oophorectomy

An ovary and tube removed through a single incision using the A) TriPort and B) SILS Port systems.Compared with conventional laparoscopy, the larger incision associated with single-port surgery facilitates specimen removal. Larger or potentially malignant specimens can be placed into an EndoCatch bag (Covidien) inserted through the single-incision 10-mm cannula (FIGURE 7).

FIGURE 7 Specimen removal

In this case, the specimen was placed in a 10-mm EndoCatch bag and removed through the 10-mm cannula of the SILS Port.In total laparoscopic hysterectomy or laparoscopic-assisted vaginal hysterectomy, the uterus is removed through the vagina. In supracervical hysterectomy, a small uterus can be removed through the cul-de-sac or directly through the single incision after placement in a bag.

When morcellation is required, the instrument can be placed through the cul-desac, cervix, or a single port. The morcellator can be placed directly through the SPLS port while utilizing the flexible scope in an angled direction (looking back toward the morcellator) for complete visualization (note: Covidien does not recommend this usage).

Transcervical tissue morcellation has also been described. In this approach, the cervix is dilated once the uterine body has been amputated, and the tissue morcellator is inserted through the cervix while the surgeon maintains visualization from above.6,13

How to master the technique

Many patients desire SPLS for its superior cosmetic outcome, but the approach may not always be appropriate. Depending on the procedure and characteristics of the patient (TABLE), multiple-port laparoscopy may be a better option. When a surgeon first attempts SPLS, we recommend that it be limited to the treatment of adnexal pathology only.

In your early SPlS cases, look for these patient characteristics

|

By using the techniques described in this article and selecting patients carefully, the surgeon can develop expertise in SPLS.11,14 During the learning process, the use of additional ports or Mini-Lap instruments (Stryker) can reduce the challenges of more difficult procedures and should be considered without reservation, as should the use of articulating accessory instruments and flexible or angled laparoscopes.

Although the clinical benefits of SPLS have yet to be determined, the cosmetic advantage of a single, hidden, umbilical incision likely increases patient satisfaction.

Clearly, the goal of SPLS is to use technology in a way that offers all of the benefits of traditional multiport laparoscopy without any of the limitations. Further study is required to determine whether SPLS meets this standard and, more important, whether it has any advantages over conventional techniques.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

- Update on minimally invasive surgery