User login

Current Approaches to Measuring Functional Status Among Older Adults in VA Primary Care Clinics

The ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs), commonly called functional status, is central to older adults’ quality of life (QOL) and independence.1,2 Understanding functional status is key to improving outcomes for older adults. In community-dwelling older adults with difficulty performing basic ADLs, practical interventions, including physical and occupational therapy, can improve functioning and prevent functional decline.3,4 Understanding function also is important for delivering patient-centered care, including individualizing cancer screening,5 evaluating how patients will tolerate interventions,6-9 and helping patients and families determine the need for long-term services and supports.

For these reasons, assessing functional status is a cornerstone of geriatrics practice. However, most older adults are cared for in primary care settings where routine measurement of functional status is uncommon.10,11 Although policy leaders have long noted this gap and the obstacle it poses to improving the quality and outcomes of care for older adults, many health care systems have been slow to incorporate measurement of functional status into routine patient care.12-14

Over the past several years, the VA has been a leader in the efforts to address this barrier by implementing routine, standardized measurement of functional status in primary care clinics. Initially, the VA encouraged, but did not require, measurement of functional status among older adults, but the implementation barriers and facilitators were not formally assessed.15 In a postimplementation evaluation, the authors found that a relatively small number of medical centers implemented functional measures. Moreover, the level of implementation seemed to vary across sites. Some sites were collecting complete measures on all eligible older patients, while other sites were collecting measures less consistently.15

As part of a national VA initiative to learn how best to implement standardized functional status measurement, the authors are conducting a qualitative study, including a formal assessment of barriers and facilitators to implementing functional assessments in VA primary care clinics. In the current project, which serves as formative work for this larger ongoing study, the authors identified and described current processes for measuring functional status in VA primary care patient aligned care team (PACT) and Geriatric (GeriPACT) clinics.

Methods

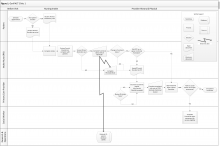

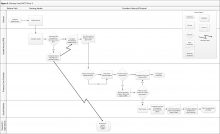

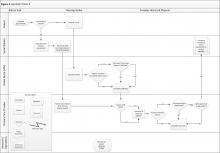

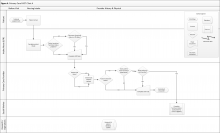

A rapid qualitative analysis approach was used, which included semistructured interviews with primary care stakeholders and rapid data analysis to summarize each clinic’s approach to measuring functional status and develop process maps for each clinic (eFigures 1, 2, 3, and 4 ). Interviews and analyses were conducted by a team consisting of a geriatrician clinician-researcher, a medical anthropologist, and a research coordinator. The institutional review boards of the San Francisco VAMC and the University of California, San Francisco approved the study.

Sampling Strategy

In order to identify VAMCs with varying approaches to assessing functional status in older patients who attended primary care appointments, the study used a criterion sampling approach.16,17 First, national “health factors” data were extracted from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). Health factors are patient data collected through screening tools called clinical reminders, which prompt clinic staff and providers to enter data into checkbox-formatted templates. The study then identified medical centers that collected health factors data from patients aged ≥ 65 years (157 of 165 medical centers). A keyword search identified health factors related to the Katz ADL (bathing, dressing, transferring, toileting, and eating), and Lawton Instrumental ADL (IADL) Scale (using the telephone, shopping, preparing food, housekeeping, doing laundry, using transportation, managing medications, and managing finances).18,19 Health factors that were not collected during a primary care appointment were excluded.

Of the original 157 medical centers, 139 met these initial inclusion criteria. Among these 139 medical centers, 66 centers did not collect complete data on these 5 ADLs and 8 IADLs (eg, only ADLs or only IADLs, or only certain ADLs or IADLs).

Two medical centers were selected in each of the following 3 categories: (1) routinely used clinical reminders to collect standardized data on the Katz ADL and the Lawton IADL Scale; (2) routinely used clinical reminders to collect functional status data but collected partial information; and (3) did not use a clinical reminder to collect functional status data. To ensure that these 6 medical centers were geographically representative, the sample included at least 1 site from each of the 5 VA regions: 1 North Atlantic, 1 Southeast, 1 Midwest, 2 Continental (1 from the northern Continental region and 1 from the southern), and 1 Pacific. Three sites that included GeriPACTs also were sampled.

Primary care PACT and GeriPACT members from these 6 medical centers were recruited to participate. These PACT members included individuals who can assess function or use functional status information to inform patient care, including front-line nursing staff (licensed practical nurses [LPNs], and registered nurses [RNs]), primary care providers (medical doctors [MDs] and nurse practitioners [NPs]), and social workers (SWs).

Local bargaining units, nurse managers, and clinic directors provided lists of all clinic staff. All members of each group then received recruitment e-mails. Phone interviews were scheduled with interested participants. In several cases, a snowball sampling approach was used to increase enrollment numbers by asking interview participants to recommend colleagues who might be interested in participating.17

Data Collection

Telephone interviews were conducted between March 2016 and October 2016 using semistructured guides developed from the project aims and from related literature in implementation science.20,21 Interview domains included clinic structure, team member roles and responsibilities, current practices for collecting functional status data, and opinions on barriers and facilitators to assessing and recording functional status (Appendix:

Data Analysis

Rapid analysis, a team-based qualitative approach was used to engage efficiently and systematically with the data.22,23 This approach allowed results to be analyzed more quickly than in traditional qualitative analysis in order to inform intervention design and develop implementation strategies.23 Rapid analysis typically includes organization of interview data into summary templates, followed by a matrix analysis, which was used to create process maps.24

Summary Templates

Summary templates were developed from the interview guides by shortening each question into a representative code. The project team then read the transcripts and summarized key points in the appropriate section of the template. This process, known as data reduction, is used to organize and highlight material so conclusions can be drawn from the data easily.22 In order to maintain rigor and trustworthiness, one team member conducted the interview, and a different team member created the interview summary. All team members reviewed each summary and met regularly to discuss results.

The summary templates were converted into matrix analyses, a method of displaying data to identify relationships, including commonalities and differences.24 The matrixes were organized by stakeholder group and clinic in order to compare functional status assessment and documentation workflows across clinics.

Process Maps

Finally, the team used the matrix data to create process maps for each clinic of when, where, and by whom functional status information was assessed and documented. These maps were created using Microsoft Visio (Redmond, WA). The maps integrated perspectives from all participants to give an overview of the process for collecting functional status data in each clinic setting. To ensure accuracy, participants at each site received process maps to solicit feedback and validation.

Results

Forty-six participants at 6 medical centers (20 MDs and NPs, 19 RNs and LPNs, and 7 SWs) from 9 primary care clinics provided samples and interviews. The study team identified 3 general approaches to functional status assessment: (1) Routine collection of functional status data via a standardized clinical reminder; (2) Routine collection of functional status data via methods other than a clinical reminder (eg, a previsit telephone screen or electronic note template); and (3) Ad hoc approaches to measuring functional status (ie, no standard or routine approach to assessing or documenting functional status). The study team selected 4 clinics (2 PACTs and 2 GeriPACTs) clinics to serve as examples of the 3 identified approaches.

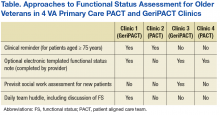

The processes for functional status assessment in each of 4 clinics are summarized in the following detailed descriptions (Table).

Clinic 1

Clinic 1 is a GeriPACT clinic that routinely assesses and documents functional status for all patients (efigure 1, available at feprac.com). The clinic’s current process includes 4 elements: (1) a patient questionnaire; (2) an annual clinical reminder administered by an RN; (3) a primary care provider (PCP) assessment; and (4) a postvisit SW assessment if referred by the PCP.

All newly referred patients are mailed a paper questionnaire that includes questions about their medical history and functional status. The patient is asked to bring the completed questionnaire to the first appointment. The clinic RN completes this form for returning patients at every visit during patient intake.

Second, the clinic uses an annual functional status clinical reminder for patients aged ≥ 75 years. The reminder includes questions about a patient’s ability to perform ADLs and IADLs with 3 to 4 response options for each question. If the clinical reminder is due at the time of a patient appointment, the RN fills out the reminder using information from the paper questionnaire. The RN also records this functional status in the nursing intake note. The RN may elect to designate the PCP as a cosigner for the nursing intake note especially if there are concerns about or changes in the patient’s functional status.

Third, the RN brings the paper form to the PCP, who often uses the questionnaire to guide the patient history. The PCP then uses the questionnaire and patient history to complete a functional status template within their visit note. The PCP also may use this information to inform patient care (eg, to make referrals to physical or occupational therapy).

Finally, the PCP might refer the patient to SW. The SW may be able to see the patient immediately after the PCP appointment, but if not, the SW follows up with a phone call to complete further functional status assessment and eligibility forms.

In addition to the above assessments by individual team members, the PACT has an interdisciplinary team huddle at the end of each clinic to discuss any issues or concerns about specific patients. The huddles often focus on issues related to functional status.

Clinic 2

Clinic 2 is a primary care PACT clinic that routinely assesses and documents functional status (eFigure 2, available at fedprac.com). The clinic process includes 3 steps: an annual clinical reminder for patients aged ≥ 75 years; a PCP assessment; and a postvisit SW assessment if referred by the PCP.

First, patients see an LPN for the intake process. During intake, the LPN records vitals and completes relevant clinical reminders. Similar to Clinic 1, Clinic 2 requires an annual functional status clinical reminder that includes ADLs and IADLs for patients aged ≥ 75 years. Patient information from the intake and clinical reminders are recorded by the LPN in a preventative medicine note in the electronic health record. This note is printed and handed to the PCP.

The PCP may review the preventative medicine note prior to completing the patient history and physical, including the functional status clinical reminder when applicable. If the PCP follows up on any functional issues identified by the LPN or completes further assessment of patient function, he or she may use this information to refer the patient to services or to place a SW consult; the PCP’s functional assessment is documented in a free-form visit note.

When the SW receives a consult, a chart review for social history, demographic information, and previous functional status assessments is conducted. The SW then calls the patient to administer functional and cognitive assessments over the phone and refers the patient to appropriate services based on eligibility.

Clinic 3

Clinic 3 is a GeriPACT clinic where functional status information is routinely collected for all new patients but may or may not be collected for returning patients (eFigure 3, available at fedprac.com). The process for new patients includes a previsit SW assessment; an informal LPN screening (ie, not based on a standardized clinical reminder); a PCP assessment; and a postvisit SW assessment if referred by the provider. The process for returning patients is similar but omits the previsit social work assessment. New patients complete a comprehensive questionnaire with a SW before their first clinic visit. The questionnaire is completed by phone and involves an extensive social and medical history, including an assessment of ADLs and IADLs. This assessment is recorded in a free-form social work note.

Next, both new and returning patients see an LPN who completes the intake process, including vitals and clinical reminders. Clinic 3 does not have a clinical reminder for functional status. However, the LPN could elect to ask about ADLs or IADLs if the patient brings up a functional issue related to the chief symptom or if the LPN observes something that indicates possible functional impairment, such as difficulty walking or a disheveled appearance. If discussed, this information is recorded in the LPN intake note, and the LPN also could verbally inform the PCP of the patient’s functional status. The RN is not formally involved in intake or functional status assessment in this clinic.

Finally, the patient sees the PCP, who may or may not have reviewed the LPN note. The PCP may assess functional status at his or her discretion, but there was no required assessment. The PCP could complete an optional functional status assessment template included in the PCP visit note. The PCP can refer the patient to services or to SW for further evaluation.

Clinic 4

Clinic 4 is a primary care PACT clinic that does not routinely measure functional status (eFigure 4, available at fedprac.com). The approach includes an informal LPN screening (ie, not based on a standardized clinical reminder); a PCP assessment; and a postvisit social worker assessment if referred by the provider. These steps are very similar to those of clinic 3, but they do not include a previsit SW assessment for new patients.

Although not represented within the 4 clinics described in this article, the content of functional status clinical reminders differed across the 9 clinics in the larger sample. Clinical reminders differed across several domains, including the type of question stems (scripted questions for each ADL vs categories for each activity); response options (eg, dichotomous vs ≥ 3 options), and the presence of free-text boxes to allow staff to enter any additional notes.

Discussion

Approaches to assessing and documenting functional status varied widely. Whereas some clinics primarily used informal approaches to assessing and documenting functional status (ie, neither routine nor standardized), others used a routine, standardized clinical reminder, and some combined several standardized approaches to measuring function. The study team identified variability across several domains of the functional status assessment process, including documentation, workflow, and clinical reminder content.

Approaches to functional assessment differed between GeriPACT and PACT clinics. Consistent with the central role that functional status assessment plays in geriatrics practice, GeriPACTs tended to employ a routine, multidisciplinary approach to measuring functional status. This approach included standardized functional assessments by multiple primary care team members, including LPNs, SWs, and PCPs. In contrast, when PACTs completed standardized functional status assessment, it was generally carried out by a single team member (typically an LPN). The PCPs in PACTs used a nonroutine approach to assess functional status in which they performed detailed functional assessments for certain high-risk patients and referred a subset for further SW evaluation.

These processes are consistent with research showing that standardized functional status data are seldom collected routinely in nongeriatric primary care settings.11 Reports by PCPs that they did not always assess functional status also are consistent with previous research demonstrating that clinicians are not always aware of their patients’ functional ability.10

In addition to highlighting differences between GeriPACT and PACTs, the identified processes illustrate the variability in documentation, clinic workflow, and clinical reminder content across all clinics. Approaches to documentation included checkbox-formatted clinical reminders with and without associated nursing notes, patient questionnaires, and templated PCP and SW notes. Clinics employed varying approaches to collect functional status information and to ensure that those data were shared with the team. Clinic staff assessed functional status at different times during the clinical encounter. Clinics used several approaches to share this information with team members, including warm handoffs from LPNs to PCPs, interdisciplinary team huddles, and electronic signoffs. Finally, clinical reminder content varied between clinics, with differences in the wording of ADL and IADL questions as well as in the number and type of response options.

This variability highlights the challenges inherent in developing a routine, standardized approach to measuring functional status that can be adapted across primary care settings. Such an approach must be both flexible enough to accommodate variation in workflow and structured enough to capture accurate data that can be used to guide clinical decisions. Capturing accurate, standardized data in CDW also will inform efforts to improve population health by allowing VHA leaders to understand the scope of disability among older veterans and plan for service needs and interventions.

Whereas the larger qualitative study will identify the specific barriers and facilitators to developing and implementing such an approach, current clinic processes present here offer hints as to which features may be important. For example, several clinics collected functional status information before the visit by telephone or questionnaire. Therefore, it will be important to choose a functional status assessment instrument that is validated for both telephone and in-person use. Similarly, some clinics had structured clinical reminders with categoric response options, whereas others included free-text boxes. Incorporating both categoric responses (to ensure accurate data) as well as free-text (to allow for additional notes about a patient’s specific circumstances that may influence service needs) may be one approach.

Limitations

This study’s approach to identifying clinic processes had several limitations. First, the authors did not send process maps to clinic directors for verification. However, speaking with PACT members who carry out clinic processes is likely the most accurate way to identify practice. Second, the results may not be generalizable to all VA primary care settings. Due to resource limitations and project scope, community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs) were not included. Compared with clinics based in medical centers, CBOCs may have different staffing levels, practice models, and needs regarding implementation of functional status assessment.

Although 46 participants from 9 clinics were interviewed, there are likely additional approaches to measuring functional status that are not represented within this sample. In addition, 3 of the 4 clinics included are affiliated with academic institutions, and all 4 are located in large cities. Efforts to include rural VAMCs were not successful. Finally, clinic-level characteristics were not reported, which may impact clinic processes. Although study participants were asked about clinic characteristics, they were often unsure or only able to provide rough estimates. In the ongoing qualitative study, the authors will attempt to collect more reliable data about these clinic-level characteristics and to examine the potential role these characteristics may play as barriers or facilitators to implementing routine assessment of functional status in primary care settings.

Conclusion

VA primary care clinics had widely varying approaches for assessing and documenting functional status. This work along with a larger ongoing qualitative study that includes interviews with veterans will directly inform the design and implementation of a standardized, patient-centered approach to functional assessment that can be adapted across varied primary care settings. Implementing standardized functional status measurement will allow the VA to serve veterans better by using functional status information to refer patients to appropriate services and to deliver patient-centered care with the potential to improve patient function and quality of life.

1.Covinsky KE, Wu AW, Landefeld CS, et al. Health status versus quality of life in older patients: does the distinction matter? Am J Med. 1999;106(4):435-440.

2. Fried TR, McGraw S, Agostini JV, Tinetti ME. Views of older persons with multiple morbidities on competing outcomes and clinical decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(10):1839-1844.

3. Beswick AD, Rees K, Dieppe P, et al. Complex interventions to improve physical function and maintain independent living in elderly people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2008;371(9614):725-735.

4. Szanton SL, Leff B, Wolff JL, Roberts L, Gitlin LN. Home-based care program reduces disability and promotes aging in place. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(9):1558-1563.

5. Walter LC, Covinsky KE. Cancer screening in elderly patients: a framework for individualized decision making. JAMA. 2001;285(21):2750-2756.

6. Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, Yaffe K, Landefeld CS, McCulloch CE. Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1539-1547.

7. Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, et al. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(25):3457-3465.

8. Crawford RS, Cambria RP, Abularrage CJ, et al. Preoperative functional status predicts perioperative outcomes after infrainguinal bypass surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51(2):351-358; discussion 358-359.

9. Arnold SV, Reynolds MR, Lei Y, et al; PARTNER Investigators. Predictors of poor outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: results from the PARTNER (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valve) trial. Circulation. 2014;129(25):2682-2690.

10. Calkins DR, Rubenstein LV, Cleary PD, et al. Failure of physicians to recognize functional disability in ambulatory patients. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114(6):451-454.

11. Bogardus ST Jr, Towle V, Williams CS, Desai MM, Inouye SK. What does the medical record reveal about functional status? A comparison of medical record and interview data. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(11):728-736.

12. Bierman AS. Functional status: the six vital sign. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(11):785-786.

13. Iezzoni LI, Greenberg MS. Capturing and classifying functional status information in administrative databases. Health Care Financ Rev. 2003;24(3):61-76.

14. Clauser SB, Bierman AS. Significance of functional status data for payment and quality. Health Care Financ Rev. 2003;24(3):1-12.

15. Brown RT, Komaiko KD, Shi Y, et al. Bringing functional status into a big data world: validation of national Veterans Affairs functional status data. PloS One. 2017;12(6):e0178726.

16. Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(5):533-544.

17. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research Evaluation and Methods. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2015.

18. Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185(12):914-919.

19. Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179-186.

20. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50.

21. Saleem JJ, Patterson ES, Militello L, Render ML, Orshansky G, Asch SM. Exploring barriers and facilitators to the use of computerized clinical reminders. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12(4):438-447.

22. Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2014.

23. Hamilton AB. Qualitative methods in rapid turn-around health services research. https://www.hsrd .research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars /archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=780. Published December 11, 2013. Accessed August 9, 2017.

24. Averill JB. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2002;12(6):855-866.

The ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs), commonly called functional status, is central to older adults’ quality of life (QOL) and independence.1,2 Understanding functional status is key to improving outcomes for older adults. In community-dwelling older adults with difficulty performing basic ADLs, practical interventions, including physical and occupational therapy, can improve functioning and prevent functional decline.3,4 Understanding function also is important for delivering patient-centered care, including individualizing cancer screening,5 evaluating how patients will tolerate interventions,6-9 and helping patients and families determine the need for long-term services and supports.

For these reasons, assessing functional status is a cornerstone of geriatrics practice. However, most older adults are cared for in primary care settings where routine measurement of functional status is uncommon.10,11 Although policy leaders have long noted this gap and the obstacle it poses to improving the quality and outcomes of care for older adults, many health care systems have been slow to incorporate measurement of functional status into routine patient care.12-14

Over the past several years, the VA has been a leader in the efforts to address this barrier by implementing routine, standardized measurement of functional status in primary care clinics. Initially, the VA encouraged, but did not require, measurement of functional status among older adults, but the implementation barriers and facilitators were not formally assessed.15 In a postimplementation evaluation, the authors found that a relatively small number of medical centers implemented functional measures. Moreover, the level of implementation seemed to vary across sites. Some sites were collecting complete measures on all eligible older patients, while other sites were collecting measures less consistently.15

As part of a national VA initiative to learn how best to implement standardized functional status measurement, the authors are conducting a qualitative study, including a formal assessment of barriers and facilitators to implementing functional assessments in VA primary care clinics. In the current project, which serves as formative work for this larger ongoing study, the authors identified and described current processes for measuring functional status in VA primary care patient aligned care team (PACT) and Geriatric (GeriPACT) clinics.

Methods

A rapid qualitative analysis approach was used, which included semistructured interviews with primary care stakeholders and rapid data analysis to summarize each clinic’s approach to measuring functional status and develop process maps for each clinic (eFigures 1, 2, 3, and 4 ). Interviews and analyses were conducted by a team consisting of a geriatrician clinician-researcher, a medical anthropologist, and a research coordinator. The institutional review boards of the San Francisco VAMC and the University of California, San Francisco approved the study.

Sampling Strategy

In order to identify VAMCs with varying approaches to assessing functional status in older patients who attended primary care appointments, the study used a criterion sampling approach.16,17 First, national “health factors” data were extracted from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). Health factors are patient data collected through screening tools called clinical reminders, which prompt clinic staff and providers to enter data into checkbox-formatted templates. The study then identified medical centers that collected health factors data from patients aged ≥ 65 years (157 of 165 medical centers). A keyword search identified health factors related to the Katz ADL (bathing, dressing, transferring, toileting, and eating), and Lawton Instrumental ADL (IADL) Scale (using the telephone, shopping, preparing food, housekeeping, doing laundry, using transportation, managing medications, and managing finances).18,19 Health factors that were not collected during a primary care appointment were excluded.

Of the original 157 medical centers, 139 met these initial inclusion criteria. Among these 139 medical centers, 66 centers did not collect complete data on these 5 ADLs and 8 IADLs (eg, only ADLs or only IADLs, or only certain ADLs or IADLs).

Two medical centers were selected in each of the following 3 categories: (1) routinely used clinical reminders to collect standardized data on the Katz ADL and the Lawton IADL Scale; (2) routinely used clinical reminders to collect functional status data but collected partial information; and (3) did not use a clinical reminder to collect functional status data. To ensure that these 6 medical centers were geographically representative, the sample included at least 1 site from each of the 5 VA regions: 1 North Atlantic, 1 Southeast, 1 Midwest, 2 Continental (1 from the northern Continental region and 1 from the southern), and 1 Pacific. Three sites that included GeriPACTs also were sampled.

Primary care PACT and GeriPACT members from these 6 medical centers were recruited to participate. These PACT members included individuals who can assess function or use functional status information to inform patient care, including front-line nursing staff (licensed practical nurses [LPNs], and registered nurses [RNs]), primary care providers (medical doctors [MDs] and nurse practitioners [NPs]), and social workers (SWs).

Local bargaining units, nurse managers, and clinic directors provided lists of all clinic staff. All members of each group then received recruitment e-mails. Phone interviews were scheduled with interested participants. In several cases, a snowball sampling approach was used to increase enrollment numbers by asking interview participants to recommend colleagues who might be interested in participating.17

Data Collection

Telephone interviews were conducted between March 2016 and October 2016 using semistructured guides developed from the project aims and from related literature in implementation science.20,21 Interview domains included clinic structure, team member roles and responsibilities, current practices for collecting functional status data, and opinions on barriers and facilitators to assessing and recording functional status (Appendix:

Data Analysis

Rapid analysis, a team-based qualitative approach was used to engage efficiently and systematically with the data.22,23 This approach allowed results to be analyzed more quickly than in traditional qualitative analysis in order to inform intervention design and develop implementation strategies.23 Rapid analysis typically includes organization of interview data into summary templates, followed by a matrix analysis, which was used to create process maps.24

Summary Templates

Summary templates were developed from the interview guides by shortening each question into a representative code. The project team then read the transcripts and summarized key points in the appropriate section of the template. This process, known as data reduction, is used to organize and highlight material so conclusions can be drawn from the data easily.22 In order to maintain rigor and trustworthiness, one team member conducted the interview, and a different team member created the interview summary. All team members reviewed each summary and met regularly to discuss results.

The summary templates were converted into matrix analyses, a method of displaying data to identify relationships, including commonalities and differences.24 The matrixes were organized by stakeholder group and clinic in order to compare functional status assessment and documentation workflows across clinics.

Process Maps

Finally, the team used the matrix data to create process maps for each clinic of when, where, and by whom functional status information was assessed and documented. These maps were created using Microsoft Visio (Redmond, WA). The maps integrated perspectives from all participants to give an overview of the process for collecting functional status data in each clinic setting. To ensure accuracy, participants at each site received process maps to solicit feedback and validation.

Results

Forty-six participants at 6 medical centers (20 MDs and NPs, 19 RNs and LPNs, and 7 SWs) from 9 primary care clinics provided samples and interviews. The study team identified 3 general approaches to functional status assessment: (1) Routine collection of functional status data via a standardized clinical reminder; (2) Routine collection of functional status data via methods other than a clinical reminder (eg, a previsit telephone screen or electronic note template); and (3) Ad hoc approaches to measuring functional status (ie, no standard or routine approach to assessing or documenting functional status). The study team selected 4 clinics (2 PACTs and 2 GeriPACTs) clinics to serve as examples of the 3 identified approaches.

The processes for functional status assessment in each of 4 clinics are summarized in the following detailed descriptions (Table).

Clinic 1

Clinic 1 is a GeriPACT clinic that routinely assesses and documents functional status for all patients (efigure 1, available at feprac.com). The clinic’s current process includes 4 elements: (1) a patient questionnaire; (2) an annual clinical reminder administered by an RN; (3) a primary care provider (PCP) assessment; and (4) a postvisit SW assessment if referred by the PCP.

All newly referred patients are mailed a paper questionnaire that includes questions about their medical history and functional status. The patient is asked to bring the completed questionnaire to the first appointment. The clinic RN completes this form for returning patients at every visit during patient intake.

Second, the clinic uses an annual functional status clinical reminder for patients aged ≥ 75 years. The reminder includes questions about a patient’s ability to perform ADLs and IADLs with 3 to 4 response options for each question. If the clinical reminder is due at the time of a patient appointment, the RN fills out the reminder using information from the paper questionnaire. The RN also records this functional status in the nursing intake note. The RN may elect to designate the PCP as a cosigner for the nursing intake note especially if there are concerns about or changes in the patient’s functional status.

Third, the RN brings the paper form to the PCP, who often uses the questionnaire to guide the patient history. The PCP then uses the questionnaire and patient history to complete a functional status template within their visit note. The PCP also may use this information to inform patient care (eg, to make referrals to physical or occupational therapy).

Finally, the PCP might refer the patient to SW. The SW may be able to see the patient immediately after the PCP appointment, but if not, the SW follows up with a phone call to complete further functional status assessment and eligibility forms.

In addition to the above assessments by individual team members, the PACT has an interdisciplinary team huddle at the end of each clinic to discuss any issues or concerns about specific patients. The huddles often focus on issues related to functional status.

Clinic 2

Clinic 2 is a primary care PACT clinic that routinely assesses and documents functional status (eFigure 2, available at fedprac.com). The clinic process includes 3 steps: an annual clinical reminder for patients aged ≥ 75 years; a PCP assessment; and a postvisit SW assessment if referred by the PCP.

First, patients see an LPN for the intake process. During intake, the LPN records vitals and completes relevant clinical reminders. Similar to Clinic 1, Clinic 2 requires an annual functional status clinical reminder that includes ADLs and IADLs for patients aged ≥ 75 years. Patient information from the intake and clinical reminders are recorded by the LPN in a preventative medicine note in the electronic health record. This note is printed and handed to the PCP.

The PCP may review the preventative medicine note prior to completing the patient history and physical, including the functional status clinical reminder when applicable. If the PCP follows up on any functional issues identified by the LPN or completes further assessment of patient function, he or she may use this information to refer the patient to services or to place a SW consult; the PCP’s functional assessment is documented in a free-form visit note.

When the SW receives a consult, a chart review for social history, demographic information, and previous functional status assessments is conducted. The SW then calls the patient to administer functional and cognitive assessments over the phone and refers the patient to appropriate services based on eligibility.

Clinic 3

Clinic 3 is a GeriPACT clinic where functional status information is routinely collected for all new patients but may or may not be collected for returning patients (eFigure 3, available at fedprac.com). The process for new patients includes a previsit SW assessment; an informal LPN screening (ie, not based on a standardized clinical reminder); a PCP assessment; and a postvisit SW assessment if referred by the provider. The process for returning patients is similar but omits the previsit social work assessment. New patients complete a comprehensive questionnaire with a SW before their first clinic visit. The questionnaire is completed by phone and involves an extensive social and medical history, including an assessment of ADLs and IADLs. This assessment is recorded in a free-form social work note.

Next, both new and returning patients see an LPN who completes the intake process, including vitals and clinical reminders. Clinic 3 does not have a clinical reminder for functional status. However, the LPN could elect to ask about ADLs or IADLs if the patient brings up a functional issue related to the chief symptom or if the LPN observes something that indicates possible functional impairment, such as difficulty walking or a disheveled appearance. If discussed, this information is recorded in the LPN intake note, and the LPN also could verbally inform the PCP of the patient’s functional status. The RN is not formally involved in intake or functional status assessment in this clinic.

Finally, the patient sees the PCP, who may or may not have reviewed the LPN note. The PCP may assess functional status at his or her discretion, but there was no required assessment. The PCP could complete an optional functional status assessment template included in the PCP visit note. The PCP can refer the patient to services or to SW for further evaluation.

Clinic 4

Clinic 4 is a primary care PACT clinic that does not routinely measure functional status (eFigure 4, available at fedprac.com). The approach includes an informal LPN screening (ie, not based on a standardized clinical reminder); a PCP assessment; and a postvisit social worker assessment if referred by the provider. These steps are very similar to those of clinic 3, but they do not include a previsit SW assessment for new patients.

Although not represented within the 4 clinics described in this article, the content of functional status clinical reminders differed across the 9 clinics in the larger sample. Clinical reminders differed across several domains, including the type of question stems (scripted questions for each ADL vs categories for each activity); response options (eg, dichotomous vs ≥ 3 options), and the presence of free-text boxes to allow staff to enter any additional notes.

Discussion

Approaches to assessing and documenting functional status varied widely. Whereas some clinics primarily used informal approaches to assessing and documenting functional status (ie, neither routine nor standardized), others used a routine, standardized clinical reminder, and some combined several standardized approaches to measuring function. The study team identified variability across several domains of the functional status assessment process, including documentation, workflow, and clinical reminder content.

Approaches to functional assessment differed between GeriPACT and PACT clinics. Consistent with the central role that functional status assessment plays in geriatrics practice, GeriPACTs tended to employ a routine, multidisciplinary approach to measuring functional status. This approach included standardized functional assessments by multiple primary care team members, including LPNs, SWs, and PCPs. In contrast, when PACTs completed standardized functional status assessment, it was generally carried out by a single team member (typically an LPN). The PCPs in PACTs used a nonroutine approach to assess functional status in which they performed detailed functional assessments for certain high-risk patients and referred a subset for further SW evaluation.

These processes are consistent with research showing that standardized functional status data are seldom collected routinely in nongeriatric primary care settings.11 Reports by PCPs that they did not always assess functional status also are consistent with previous research demonstrating that clinicians are not always aware of their patients’ functional ability.10

In addition to highlighting differences between GeriPACT and PACTs, the identified processes illustrate the variability in documentation, clinic workflow, and clinical reminder content across all clinics. Approaches to documentation included checkbox-formatted clinical reminders with and without associated nursing notes, patient questionnaires, and templated PCP and SW notes. Clinics employed varying approaches to collect functional status information and to ensure that those data were shared with the team. Clinic staff assessed functional status at different times during the clinical encounter. Clinics used several approaches to share this information with team members, including warm handoffs from LPNs to PCPs, interdisciplinary team huddles, and electronic signoffs. Finally, clinical reminder content varied between clinics, with differences in the wording of ADL and IADL questions as well as in the number and type of response options.

This variability highlights the challenges inherent in developing a routine, standardized approach to measuring functional status that can be adapted across primary care settings. Such an approach must be both flexible enough to accommodate variation in workflow and structured enough to capture accurate data that can be used to guide clinical decisions. Capturing accurate, standardized data in CDW also will inform efforts to improve population health by allowing VHA leaders to understand the scope of disability among older veterans and plan for service needs and interventions.

Whereas the larger qualitative study will identify the specific barriers and facilitators to developing and implementing such an approach, current clinic processes present here offer hints as to which features may be important. For example, several clinics collected functional status information before the visit by telephone or questionnaire. Therefore, it will be important to choose a functional status assessment instrument that is validated for both telephone and in-person use. Similarly, some clinics had structured clinical reminders with categoric response options, whereas others included free-text boxes. Incorporating both categoric responses (to ensure accurate data) as well as free-text (to allow for additional notes about a patient’s specific circumstances that may influence service needs) may be one approach.

Limitations

This study’s approach to identifying clinic processes had several limitations. First, the authors did not send process maps to clinic directors for verification. However, speaking with PACT members who carry out clinic processes is likely the most accurate way to identify practice. Second, the results may not be generalizable to all VA primary care settings. Due to resource limitations and project scope, community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs) were not included. Compared with clinics based in medical centers, CBOCs may have different staffing levels, practice models, and needs regarding implementation of functional status assessment.

Although 46 participants from 9 clinics were interviewed, there are likely additional approaches to measuring functional status that are not represented within this sample. In addition, 3 of the 4 clinics included are affiliated with academic institutions, and all 4 are located in large cities. Efforts to include rural VAMCs were not successful. Finally, clinic-level characteristics were not reported, which may impact clinic processes. Although study participants were asked about clinic characteristics, they were often unsure or only able to provide rough estimates. In the ongoing qualitative study, the authors will attempt to collect more reliable data about these clinic-level characteristics and to examine the potential role these characteristics may play as barriers or facilitators to implementing routine assessment of functional status in primary care settings.

Conclusion

VA primary care clinics had widely varying approaches for assessing and documenting functional status. This work along with a larger ongoing qualitative study that includes interviews with veterans will directly inform the design and implementation of a standardized, patient-centered approach to functional assessment that can be adapted across varied primary care settings. Implementing standardized functional status measurement will allow the VA to serve veterans better by using functional status information to refer patients to appropriate services and to deliver patient-centered care with the potential to improve patient function and quality of life.

The ability to perform activities of daily living (ADLs), commonly called functional status, is central to older adults’ quality of life (QOL) and independence.1,2 Understanding functional status is key to improving outcomes for older adults. In community-dwelling older adults with difficulty performing basic ADLs, practical interventions, including physical and occupational therapy, can improve functioning and prevent functional decline.3,4 Understanding function also is important for delivering patient-centered care, including individualizing cancer screening,5 evaluating how patients will tolerate interventions,6-9 and helping patients and families determine the need for long-term services and supports.

For these reasons, assessing functional status is a cornerstone of geriatrics practice. However, most older adults are cared for in primary care settings where routine measurement of functional status is uncommon.10,11 Although policy leaders have long noted this gap and the obstacle it poses to improving the quality and outcomes of care for older adults, many health care systems have been slow to incorporate measurement of functional status into routine patient care.12-14

Over the past several years, the VA has been a leader in the efforts to address this barrier by implementing routine, standardized measurement of functional status in primary care clinics. Initially, the VA encouraged, but did not require, measurement of functional status among older adults, but the implementation barriers and facilitators were not formally assessed.15 In a postimplementation evaluation, the authors found that a relatively small number of medical centers implemented functional measures. Moreover, the level of implementation seemed to vary across sites. Some sites were collecting complete measures on all eligible older patients, while other sites were collecting measures less consistently.15

As part of a national VA initiative to learn how best to implement standardized functional status measurement, the authors are conducting a qualitative study, including a formal assessment of barriers and facilitators to implementing functional assessments in VA primary care clinics. In the current project, which serves as formative work for this larger ongoing study, the authors identified and described current processes for measuring functional status in VA primary care patient aligned care team (PACT) and Geriatric (GeriPACT) clinics.

Methods

A rapid qualitative analysis approach was used, which included semistructured interviews with primary care stakeholders and rapid data analysis to summarize each clinic’s approach to measuring functional status and develop process maps for each clinic (eFigures 1, 2, 3, and 4 ). Interviews and analyses were conducted by a team consisting of a geriatrician clinician-researcher, a medical anthropologist, and a research coordinator. The institutional review boards of the San Francisco VAMC and the University of California, San Francisco approved the study.

Sampling Strategy

In order to identify VAMCs with varying approaches to assessing functional status in older patients who attended primary care appointments, the study used a criterion sampling approach.16,17 First, national “health factors” data were extracted from the VA Corporate Data Warehouse (CDW). Health factors are patient data collected through screening tools called clinical reminders, which prompt clinic staff and providers to enter data into checkbox-formatted templates. The study then identified medical centers that collected health factors data from patients aged ≥ 65 years (157 of 165 medical centers). A keyword search identified health factors related to the Katz ADL (bathing, dressing, transferring, toileting, and eating), and Lawton Instrumental ADL (IADL) Scale (using the telephone, shopping, preparing food, housekeeping, doing laundry, using transportation, managing medications, and managing finances).18,19 Health factors that were not collected during a primary care appointment were excluded.

Of the original 157 medical centers, 139 met these initial inclusion criteria. Among these 139 medical centers, 66 centers did not collect complete data on these 5 ADLs and 8 IADLs (eg, only ADLs or only IADLs, or only certain ADLs or IADLs).

Two medical centers were selected in each of the following 3 categories: (1) routinely used clinical reminders to collect standardized data on the Katz ADL and the Lawton IADL Scale; (2) routinely used clinical reminders to collect functional status data but collected partial information; and (3) did not use a clinical reminder to collect functional status data. To ensure that these 6 medical centers were geographically representative, the sample included at least 1 site from each of the 5 VA regions: 1 North Atlantic, 1 Southeast, 1 Midwest, 2 Continental (1 from the northern Continental region and 1 from the southern), and 1 Pacific. Three sites that included GeriPACTs also were sampled.

Primary care PACT and GeriPACT members from these 6 medical centers were recruited to participate. These PACT members included individuals who can assess function or use functional status information to inform patient care, including front-line nursing staff (licensed practical nurses [LPNs], and registered nurses [RNs]), primary care providers (medical doctors [MDs] and nurse practitioners [NPs]), and social workers (SWs).

Local bargaining units, nurse managers, and clinic directors provided lists of all clinic staff. All members of each group then received recruitment e-mails. Phone interviews were scheduled with interested participants. In several cases, a snowball sampling approach was used to increase enrollment numbers by asking interview participants to recommend colleagues who might be interested in participating.17

Data Collection

Telephone interviews were conducted between March 2016 and October 2016 using semistructured guides developed from the project aims and from related literature in implementation science.20,21 Interview domains included clinic structure, team member roles and responsibilities, current practices for collecting functional status data, and opinions on barriers and facilitators to assessing and recording functional status (Appendix:

Data Analysis

Rapid analysis, a team-based qualitative approach was used to engage efficiently and systematically with the data.22,23 This approach allowed results to be analyzed more quickly than in traditional qualitative analysis in order to inform intervention design and develop implementation strategies.23 Rapid analysis typically includes organization of interview data into summary templates, followed by a matrix analysis, which was used to create process maps.24

Summary Templates

Summary templates were developed from the interview guides by shortening each question into a representative code. The project team then read the transcripts and summarized key points in the appropriate section of the template. This process, known as data reduction, is used to organize and highlight material so conclusions can be drawn from the data easily.22 In order to maintain rigor and trustworthiness, one team member conducted the interview, and a different team member created the interview summary. All team members reviewed each summary and met regularly to discuss results.

The summary templates were converted into matrix analyses, a method of displaying data to identify relationships, including commonalities and differences.24 The matrixes were organized by stakeholder group and clinic in order to compare functional status assessment and documentation workflows across clinics.

Process Maps

Finally, the team used the matrix data to create process maps for each clinic of when, where, and by whom functional status information was assessed and documented. These maps were created using Microsoft Visio (Redmond, WA). The maps integrated perspectives from all participants to give an overview of the process for collecting functional status data in each clinic setting. To ensure accuracy, participants at each site received process maps to solicit feedback and validation.

Results

Forty-six participants at 6 medical centers (20 MDs and NPs, 19 RNs and LPNs, and 7 SWs) from 9 primary care clinics provided samples and interviews. The study team identified 3 general approaches to functional status assessment: (1) Routine collection of functional status data via a standardized clinical reminder; (2) Routine collection of functional status data via methods other than a clinical reminder (eg, a previsit telephone screen or electronic note template); and (3) Ad hoc approaches to measuring functional status (ie, no standard or routine approach to assessing or documenting functional status). The study team selected 4 clinics (2 PACTs and 2 GeriPACTs) clinics to serve as examples of the 3 identified approaches.

The processes for functional status assessment in each of 4 clinics are summarized in the following detailed descriptions (Table).

Clinic 1

Clinic 1 is a GeriPACT clinic that routinely assesses and documents functional status for all patients (efigure 1, available at feprac.com). The clinic’s current process includes 4 elements: (1) a patient questionnaire; (2) an annual clinical reminder administered by an RN; (3) a primary care provider (PCP) assessment; and (4) a postvisit SW assessment if referred by the PCP.

All newly referred patients are mailed a paper questionnaire that includes questions about their medical history and functional status. The patient is asked to bring the completed questionnaire to the first appointment. The clinic RN completes this form for returning patients at every visit during patient intake.

Second, the clinic uses an annual functional status clinical reminder for patients aged ≥ 75 years. The reminder includes questions about a patient’s ability to perform ADLs and IADLs with 3 to 4 response options for each question. If the clinical reminder is due at the time of a patient appointment, the RN fills out the reminder using information from the paper questionnaire. The RN also records this functional status in the nursing intake note. The RN may elect to designate the PCP as a cosigner for the nursing intake note especially if there are concerns about or changes in the patient’s functional status.

Third, the RN brings the paper form to the PCP, who often uses the questionnaire to guide the patient history. The PCP then uses the questionnaire and patient history to complete a functional status template within their visit note. The PCP also may use this information to inform patient care (eg, to make referrals to physical or occupational therapy).

Finally, the PCP might refer the patient to SW. The SW may be able to see the patient immediately after the PCP appointment, but if not, the SW follows up with a phone call to complete further functional status assessment and eligibility forms.

In addition to the above assessments by individual team members, the PACT has an interdisciplinary team huddle at the end of each clinic to discuss any issues or concerns about specific patients. The huddles often focus on issues related to functional status.

Clinic 2

Clinic 2 is a primary care PACT clinic that routinely assesses and documents functional status (eFigure 2, available at fedprac.com). The clinic process includes 3 steps: an annual clinical reminder for patients aged ≥ 75 years; a PCP assessment; and a postvisit SW assessment if referred by the PCP.

First, patients see an LPN for the intake process. During intake, the LPN records vitals and completes relevant clinical reminders. Similar to Clinic 1, Clinic 2 requires an annual functional status clinical reminder that includes ADLs and IADLs for patients aged ≥ 75 years. Patient information from the intake and clinical reminders are recorded by the LPN in a preventative medicine note in the electronic health record. This note is printed and handed to the PCP.

The PCP may review the preventative medicine note prior to completing the patient history and physical, including the functional status clinical reminder when applicable. If the PCP follows up on any functional issues identified by the LPN or completes further assessment of patient function, he or she may use this information to refer the patient to services or to place a SW consult; the PCP’s functional assessment is documented in a free-form visit note.

When the SW receives a consult, a chart review for social history, demographic information, and previous functional status assessments is conducted. The SW then calls the patient to administer functional and cognitive assessments over the phone and refers the patient to appropriate services based on eligibility.

Clinic 3

Clinic 3 is a GeriPACT clinic where functional status information is routinely collected for all new patients but may or may not be collected for returning patients (eFigure 3, available at fedprac.com). The process for new patients includes a previsit SW assessment; an informal LPN screening (ie, not based on a standardized clinical reminder); a PCP assessment; and a postvisit SW assessment if referred by the provider. The process for returning patients is similar but omits the previsit social work assessment. New patients complete a comprehensive questionnaire with a SW before their first clinic visit. The questionnaire is completed by phone and involves an extensive social and medical history, including an assessment of ADLs and IADLs. This assessment is recorded in a free-form social work note.

Next, both new and returning patients see an LPN who completes the intake process, including vitals and clinical reminders. Clinic 3 does not have a clinical reminder for functional status. However, the LPN could elect to ask about ADLs or IADLs if the patient brings up a functional issue related to the chief symptom or if the LPN observes something that indicates possible functional impairment, such as difficulty walking or a disheveled appearance. If discussed, this information is recorded in the LPN intake note, and the LPN also could verbally inform the PCP of the patient’s functional status. The RN is not formally involved in intake or functional status assessment in this clinic.

Finally, the patient sees the PCP, who may or may not have reviewed the LPN note. The PCP may assess functional status at his or her discretion, but there was no required assessment. The PCP could complete an optional functional status assessment template included in the PCP visit note. The PCP can refer the patient to services or to SW for further evaluation.

Clinic 4

Clinic 4 is a primary care PACT clinic that does not routinely measure functional status (eFigure 4, available at fedprac.com). The approach includes an informal LPN screening (ie, not based on a standardized clinical reminder); a PCP assessment; and a postvisit social worker assessment if referred by the provider. These steps are very similar to those of clinic 3, but they do not include a previsit SW assessment for new patients.

Although not represented within the 4 clinics described in this article, the content of functional status clinical reminders differed across the 9 clinics in the larger sample. Clinical reminders differed across several domains, including the type of question stems (scripted questions for each ADL vs categories for each activity); response options (eg, dichotomous vs ≥ 3 options), and the presence of free-text boxes to allow staff to enter any additional notes.

Discussion

Approaches to assessing and documenting functional status varied widely. Whereas some clinics primarily used informal approaches to assessing and documenting functional status (ie, neither routine nor standardized), others used a routine, standardized clinical reminder, and some combined several standardized approaches to measuring function. The study team identified variability across several domains of the functional status assessment process, including documentation, workflow, and clinical reminder content.

Approaches to functional assessment differed between GeriPACT and PACT clinics. Consistent with the central role that functional status assessment plays in geriatrics practice, GeriPACTs tended to employ a routine, multidisciplinary approach to measuring functional status. This approach included standardized functional assessments by multiple primary care team members, including LPNs, SWs, and PCPs. In contrast, when PACTs completed standardized functional status assessment, it was generally carried out by a single team member (typically an LPN). The PCPs in PACTs used a nonroutine approach to assess functional status in which they performed detailed functional assessments for certain high-risk patients and referred a subset for further SW evaluation.

These processes are consistent with research showing that standardized functional status data are seldom collected routinely in nongeriatric primary care settings.11 Reports by PCPs that they did not always assess functional status also are consistent with previous research demonstrating that clinicians are not always aware of their patients’ functional ability.10

In addition to highlighting differences between GeriPACT and PACTs, the identified processes illustrate the variability in documentation, clinic workflow, and clinical reminder content across all clinics. Approaches to documentation included checkbox-formatted clinical reminders with and without associated nursing notes, patient questionnaires, and templated PCP and SW notes. Clinics employed varying approaches to collect functional status information and to ensure that those data were shared with the team. Clinic staff assessed functional status at different times during the clinical encounter. Clinics used several approaches to share this information with team members, including warm handoffs from LPNs to PCPs, interdisciplinary team huddles, and electronic signoffs. Finally, clinical reminder content varied between clinics, with differences in the wording of ADL and IADL questions as well as in the number and type of response options.

This variability highlights the challenges inherent in developing a routine, standardized approach to measuring functional status that can be adapted across primary care settings. Such an approach must be both flexible enough to accommodate variation in workflow and structured enough to capture accurate data that can be used to guide clinical decisions. Capturing accurate, standardized data in CDW also will inform efforts to improve population health by allowing VHA leaders to understand the scope of disability among older veterans and plan for service needs and interventions.

Whereas the larger qualitative study will identify the specific barriers and facilitators to developing and implementing such an approach, current clinic processes present here offer hints as to which features may be important. For example, several clinics collected functional status information before the visit by telephone or questionnaire. Therefore, it will be important to choose a functional status assessment instrument that is validated for both telephone and in-person use. Similarly, some clinics had structured clinical reminders with categoric response options, whereas others included free-text boxes. Incorporating both categoric responses (to ensure accurate data) as well as free-text (to allow for additional notes about a patient’s specific circumstances that may influence service needs) may be one approach.

Limitations

This study’s approach to identifying clinic processes had several limitations. First, the authors did not send process maps to clinic directors for verification. However, speaking with PACT members who carry out clinic processes is likely the most accurate way to identify practice. Second, the results may not be generalizable to all VA primary care settings. Due to resource limitations and project scope, community-based outpatient clinics (CBOCs) were not included. Compared with clinics based in medical centers, CBOCs may have different staffing levels, practice models, and needs regarding implementation of functional status assessment.

Although 46 participants from 9 clinics were interviewed, there are likely additional approaches to measuring functional status that are not represented within this sample. In addition, 3 of the 4 clinics included are affiliated with academic institutions, and all 4 are located in large cities. Efforts to include rural VAMCs were not successful. Finally, clinic-level characteristics were not reported, which may impact clinic processes. Although study participants were asked about clinic characteristics, they were often unsure or only able to provide rough estimates. In the ongoing qualitative study, the authors will attempt to collect more reliable data about these clinic-level characteristics and to examine the potential role these characteristics may play as barriers or facilitators to implementing routine assessment of functional status in primary care settings.

Conclusion

VA primary care clinics had widely varying approaches for assessing and documenting functional status. This work along with a larger ongoing qualitative study that includes interviews with veterans will directly inform the design and implementation of a standardized, patient-centered approach to functional assessment that can be adapted across varied primary care settings. Implementing standardized functional status measurement will allow the VA to serve veterans better by using functional status information to refer patients to appropriate services and to deliver patient-centered care with the potential to improve patient function and quality of life.

1.Covinsky KE, Wu AW, Landefeld CS, et al. Health status versus quality of life in older patients: does the distinction matter? Am J Med. 1999;106(4):435-440.

2. Fried TR, McGraw S, Agostini JV, Tinetti ME. Views of older persons with multiple morbidities on competing outcomes and clinical decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(10):1839-1844.

3. Beswick AD, Rees K, Dieppe P, et al. Complex interventions to improve physical function and maintain independent living in elderly people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2008;371(9614):725-735.

4. Szanton SL, Leff B, Wolff JL, Roberts L, Gitlin LN. Home-based care program reduces disability and promotes aging in place. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(9):1558-1563.

5. Walter LC, Covinsky KE. Cancer screening in elderly patients: a framework for individualized decision making. JAMA. 2001;285(21):2750-2756.

6. Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, Yaffe K, Landefeld CS, McCulloch CE. Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1539-1547.

7. Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, et al. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(25):3457-3465.

8. Crawford RS, Cambria RP, Abularrage CJ, et al. Preoperative functional status predicts perioperative outcomes after infrainguinal bypass surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51(2):351-358; discussion 358-359.

9. Arnold SV, Reynolds MR, Lei Y, et al; PARTNER Investigators. Predictors of poor outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: results from the PARTNER (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valve) trial. Circulation. 2014;129(25):2682-2690.

10. Calkins DR, Rubenstein LV, Cleary PD, et al. Failure of physicians to recognize functional disability in ambulatory patients. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114(6):451-454.

11. Bogardus ST Jr, Towle V, Williams CS, Desai MM, Inouye SK. What does the medical record reveal about functional status? A comparison of medical record and interview data. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(11):728-736.

12. Bierman AS. Functional status: the six vital sign. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(11):785-786.

13. Iezzoni LI, Greenberg MS. Capturing and classifying functional status information in administrative databases. Health Care Financ Rev. 2003;24(3):61-76.

14. Clauser SB, Bierman AS. Significance of functional status data for payment and quality. Health Care Financ Rev. 2003;24(3):1-12.

15. Brown RT, Komaiko KD, Shi Y, et al. Bringing functional status into a big data world: validation of national Veterans Affairs functional status data. PloS One. 2017;12(6):e0178726.

16. Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(5):533-544.

17. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research Evaluation and Methods. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2015.

18. Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185(12):914-919.

19. Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179-186.

20. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50.

21. Saleem JJ, Patterson ES, Militello L, Render ML, Orshansky G, Asch SM. Exploring barriers and facilitators to the use of computerized clinical reminders. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12(4):438-447.

22. Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2014.

23. Hamilton AB. Qualitative methods in rapid turn-around health services research. https://www.hsrd .research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars /archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=780. Published December 11, 2013. Accessed August 9, 2017.

24. Averill JB. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2002;12(6):855-866.

1.Covinsky KE, Wu AW, Landefeld CS, et al. Health status versus quality of life in older patients: does the distinction matter? Am J Med. 1999;106(4):435-440.

2. Fried TR, McGraw S, Agostini JV, Tinetti ME. Views of older persons with multiple morbidities on competing outcomes and clinical decision-making. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(10):1839-1844.

3. Beswick AD, Rees K, Dieppe P, et al. Complex interventions to improve physical function and maintain independent living in elderly people: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2008;371(9614):725-735.

4. Szanton SL, Leff B, Wolff JL, Roberts L, Gitlin LN. Home-based care program reduces disability and promotes aging in place. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(9):1558-1563.

5. Walter LC, Covinsky KE. Cancer screening in elderly patients: a framework for individualized decision making. JAMA. 2001;285(21):2750-2756.

6. Kurella Tamura M, Covinsky KE, Chertow GM, Yaffe K, Landefeld CS, McCulloch CE. Functional status of elderly adults before and after initiation of dialysis. N Engl J Med. 2009;361(16):1539-1547.

7. Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, et al. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29(25):3457-3465.

8. Crawford RS, Cambria RP, Abularrage CJ, et al. Preoperative functional status predicts perioperative outcomes after infrainguinal bypass surgery. J Vasc Surg. 2010;51(2):351-358; discussion 358-359.

9. Arnold SV, Reynolds MR, Lei Y, et al; PARTNER Investigators. Predictors of poor outcomes after transcatheter aortic valve replacement: results from the PARTNER (Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valve) trial. Circulation. 2014;129(25):2682-2690.

10. Calkins DR, Rubenstein LV, Cleary PD, et al. Failure of physicians to recognize functional disability in ambulatory patients. Ann Intern Med. 1991;114(6):451-454.

11. Bogardus ST Jr, Towle V, Williams CS, Desai MM, Inouye SK. What does the medical record reveal about functional status? A comparison of medical record and interview data. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(11):728-736.

12. Bierman AS. Functional status: the six vital sign. J Gen Intern Med. 2001;16(11):785-786.

13. Iezzoni LI, Greenberg MS. Capturing and classifying functional status information in administrative databases. Health Care Financ Rev. 2003;24(3):61-76.

14. Clauser SB, Bierman AS. Significance of functional status data for payment and quality. Health Care Financ Rev. 2003;24(3):1-12.

15. Brown RT, Komaiko KD, Shi Y, et al. Bringing functional status into a big data world: validation of national Veterans Affairs functional status data. PloS One. 2017;12(6):e0178726.

16. Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2015;42(5):533-544.

17. Patton MQ. Qualitative Research Evaluation and Methods. 4th ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2015.

18. Katz S, Ford AB, Moskowitz RW, Jackson BA, Jaffe MW. Studies of illness in the aged. The index of ADL: a standardized measure of biological and psychosocial function. JAMA. 1963;185(12):914-919.

19. Lawton MP, Brody EM. Assessment of older people: self-maintaining and instrumental activities of daily living. Gerontologist. 1969;9(3):179-186.

20. Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4(1):50.

21. Saleem JJ, Patterson ES, Militello L, Render ML, Orshansky G, Asch SM. Exploring barriers and facilitators to the use of computerized clinical reminders. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2005;12(4):438-447.

22. Miles MB, Huberman AM, Saldana J. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 3rd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2014.

23. Hamilton AB. Qualitative methods in rapid turn-around health services research. https://www.hsrd .research.va.gov/for_researchers/cyber_seminars /archives/video_archive.cfm?SessionID=780. Published December 11, 2013. Accessed August 9, 2017.

24. Averill JB. Matrix analysis as a complementary analytic strategy in qualitative inquiry. Qual Health Res. 2002;12(6):855-866.

Blood Cultures in Nonpneumonia Illness