User login

Inpatient Portals for Hospitalized Patients and Caregivers: A Systematic Review

Engaging patients and their caregivers in care improves health outcomes1-3 and is endorsed by leading healthcare organizations as essential to improving care quality and safety.4-6 Patient engagement emphasizes that patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers work together to “promote and support active patient and public involvement in health and healthcare and to strengthen their influence on healthcare decisions.”7 Patient portals, web-based personal health records linked to electronic health record (EHR) data, are intended to promote engagement by providing patients and their caregivers with timely electronic access to their healthcare information and supporting communication through secure messaging with their healthcare team.8 The use of patient portals has also been suggested as a way for patients and/or caregivers to identify and intercept medical errors, thus having the potential to also improve patient safety.8,9

As a requirement for meaningful use, access to health information through patient portals in the ambulatory setting has increased dramatically.10 Studies evaluating the use of these patient portals to promote patient-centered care are growing, but evidence supporting their impact on improved health outcomes is currently insufficient.11-15 Although research and policy focus on the use of patient portals in the ambulatory setting, recent literature suggests that patient portals may be used to share inpatient clinical information to engage patients and their caregivers during their hospitalization.16-18 Before the widespread use of patient portals in the inpatient setting is endorsed, systematic research is needed to understand optimal portal design requirements, if and how these portals are used, and whether their use provides value to the hospitalized patient and/or caregiver.8

Prior literature summarized early findings regarding the use of various technologies designed to engage hospitalized patients.17,19,20 In this systematic review, we describe the emerging literature examining the design, use, and impact of inpatient portals for hospitalized patients and/or caregivers over the last 10 years. Inpatient portals are defined here as electronic patient portals tethered to EHRs that are designed to provide hospitalized patients and/or caregivers secure access to personalized, inpatient clinical information with the intent of engaging them in their hospital care. After analyzing and summarizing these data, we then identify knowledge gaps and potential future research directions.

METHODS

Search Strategy, Study Selection, and Analysis

This systematic review included available, peer-reviewed, and grey literature published from January 1, 2006, to August 8, 2017, in PubMed, Web of Science (including the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Xplore), Cochrane, CINAHLPlus, and Scopus databases. Terms and phrases, including those found in the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) index, were used to identify studies evaluating (1) patient portals (“health record, personal [MeSH],” “personal health record,” “patient portal,” “inpatient portal,” “ipad,” “tablet,” or “bedside information technology”), (2) engagement (“engagement,” “empowerment,” “participation,” “activation,” or “self-efficacy”), and (3) in the hospital (“inpatient [MeSH],” “hospital [MeSH],” “hospitalized patient [MeSH],” or “unit”). MeSH terms were used when applicable. Based on previous literature, free-text terms were also used when subject headings were not applied consistently, such as with terms related to engagement.17,21 Studies were excluded if they were not written in English, if they evaluated portals exclusively in the emergency department or ambulatory setting, and/or if they described future study protocols. Studies describing general inpatient technology or evaluating portals used in the hospital but not tethered to inpatient EHR clinical data were also excluded.

By using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines,22 2 researchers (M.K. and P.H.) completed the literature search and potential article screening. Results were aggregated and studies were screened and excluded from full review based on title and abstract information. Additional studies were included after reference list review. During a full review of included studies, 2 researchers independently extracted data, including the study objective, design, setting, sample, data collection instruments, outcomes, and a description of results. Guided by our study objective, findings were reconciled by consensus and analyzed and described according to the following 3 themes: (1) inpatient portal design, (2) inpatient portal use and usability, and (3) the impact of inpatient portal use on patient or caregiver and healthcare team outcomes as defined by retrieved studies.

The quality of studies was evaluated by the same 2 researchers independently by using the Downs and Black checklist for assessing the methodological quality of randomized and nonrandomized healthcare interventions.23 Qualitative studies describing the development of portal prototypes and/or portal redesign efforts were excluded from these analyses. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.Because of the wide variability in study designs, populations, and outcomes, a meta-analysis of pooled data was not performed.

RESULTS

Of the 731 studies identified through database searching and reference review, 36 were included for full-text review and 17 met inclusion criteria (Figure; Table 1). Studies excluded after full-text review described portal use outside of the inpatient setting, portals not linked to hospital EHR clinical data, portals not designed for inpatients, and/or inpatient technology in general. The inpatient portal platforms, hardware used, and functionalities varied within included studies (Table 2). The majority of studies used custom, web-based inpatient portal applications on tablet computers. Most provided information about the patients’ hospital medications, healthcare team, and education about their condition and/or a medical glossary. Many included the patient’s schedule, hospital problem list, discharge information, and a way to keep notes.

There has been a recent increase in inpatient portal study publication, with 9 studies published during or after 2016. Five were conducted in the pediatric setting and all but 130 with English-speaking participants. Twelve studies were qualitative, many of which were conducted in multiple phases by using semi-structured interviews and/or focus groups to develop or redesign inpatient portals. Of the remaining studies, 3 used a cross-sectional design, 1 used a before and after design without a control group, and 1 was a nonrandomized trial. Studies were rated as having medium-to-high risk of bias because of design flaws (Table 1 in supplementary Appendix). Because many studies were small pilot studies and all were single-centered studies, the generalizability of findings to different healthcare settings or patient populations is limited.

Inpatient Portal Design

Most included studies evaluated patient and/or caregiver information needs to design and/or enhance inpatient portals.16,24-37 In 1 study, patients described an overall lack of information provided in the hospital and insufficient time to understand and remember information, which, when shared, was often presented by using medical terminology.30 They wanted information to help them understand their daily hospital routine, confirm and compare medications and test results, learn about care, and prepare for discharge. Participants in multiple studies echoed these results, indicating the need for a schedule of upcoming clinical events (eg, medication administration, procedures, imaging), secure and timely clinical information (eg, list of diagnoses and medications, test results), personalized education, a medical glossary, discharge information, and a way to take notes and recognize and communicate with providers.

Patients also requested further information transparency,34,37 including physicians’ notes, radiology results, operative reports, and billing information, along with general hospital information,16 meal ordering,33 and video conferencing.27 ln designing and refining an inpatient medication-tracking tool, participants identified the need for information about medication dosage, frequency, timing, administration method, criticality, alternative medications or forms, and education.26,36 Patients and/or caregivers also indicated interest in communicating with inpatient providers by using the portal.16,27,28,30-37 In 1 study, patients highlighted the need to be involved in care plan development,27 which led to portal refinement to allow for patient-generated data entry, including care goals and a way to communicate real-time concerns and feedback.28

Studies also considered healthcare team perspectives to inform portal design.25,26,28,30,35,37 Although information needs usually overlapped, patient and healthcare team priorities differed in some areas. Although patients wanted to “know what was going to happen to them,” nurses in 1 study were more concerned about providing information to protect patients, such as safety and precaution materials.25 Similarly, when designing a medication-tracking tool, patients sought information that helped them understand what to expect, while pharmacists focused on medication safety and providing information that fit their workflow (eg, abstract medication schedules).36

Identified study data raised important portal interface design considerations. Results suggested clinical data should be presented by using simple displays,28 accommodating real-time information. Participants recommended links16,29 to personalized patient-friendly37 education accessed with minimal steps.26 Interfaces may be personalized for target users, such as patient or proxy and younger or older individuals. For example, older patients reported less familiarity with touch screens, internal keyboards, and handwriting recognition, favoring voice recognition for recording notes.27 This raised questions about how portals can be designed to best maintain patient privacy.25 Interface design, such as navigation, also relied heavily on hardware choice, such as tablet versus mobile phone.28

Inpatient Portal Use and Usability

Most patient and/or caregiver participants in included studies were interested in using an inpatient portal, used it when offered, found it easy to use, useful, and/or were satisfied with it.16,18,24-37 Most used and liked functionalities that provided healthcare team, test result, and medication information.22,33,37 In the 1 identified controlled trial,18 researchers evaluated an inpatient portal given to adult inpatients that included a problem list, schedule, medication list, and healthcare team information. Of the intervention unit patients, 80% used the portal, 76% indicated it was easy to use, and 71% thought it provided useful information. When a portal was given to 239 adult patients and caregivers in another study, 66% sent a total of 291 messages to the healthcare team.31 Of these, 153 provided feedback, 76 expressed preferences, and 16 communicated concerns. In a pediatric study, an inpatient portal was given to 296 parents who sent a total of 36 messages and 176 requests.33 Messages sent included information regarding caregiver needs, questions, updates, and/or positive endorsements of the healthcare team and/or care.

Impact of Inpatient Portal Use

Multiple studies evaluated the impact of inpatient portal use on patient and/or caregiver engagement, empowerment, activation, and/or knowledge, which had mixed results. Most adult patients interviewed in one study had positive experiences using a portal to answer their questions between physician visits and learn about, remember, and engage in care.37 A majority of adult inpatient portal users in another study agreed that portal use helped them feel in control and understand their condition; however, they did not report having improved discharge timing knowledge.29 In a pediatric study, most parent inpatient portal users agreed use improved their ability to monitor, understand, and make decisions about their child’s care.33 In the controlled trial,18 a higher percentage of portal intervention patients could identify their physician or role; however, patient activation was not statistically different between intervention and control patients.

Results from included studies also evaluated the impact of portal use on communication. Some suggest inpatient portal use may replace and/or facilitate verbal communication between patients, caregivers, and providers.35 In a pediatric study, 51% of parent portal users reported it gave them the information they needed, reducing the amount of questions they had for their healthcare team.33 Similarly 43% of 14 adult inpatient portal users in another study thought the portal could replace at least some face-to-face communication.37 Some providers indicated portal use enhanced rounding discussion quality.35 Another study suggested that patient-provider communication via electronic messaging may provide benefits for some patients and not others.37

Multiple studies evaluated patient, caregiver, and/or healthcare team perceptions of the impact of inpatient portal use on detection of errors and patient safety.29,31,33,35 In adult inpatients, 6% agreed portal use could help them find errors.29 In a pediatric study, 8% reported finding at least 1 medication error by using the portal, and 89% thought use reduced errors in their child’s care.33 One patient in a qualitative study of adult inpatients cited an example of a dosing error discovered by using the portal.37 Healthcare providers in another study also reported that use facilitated patient error identification.35

Included studies evaluated the potential impact of portal use on patient anxiety, confusion, and/or worry, and the work of healthcare teams. In 1 study, nurses voiced concerns about giving information subject to change or that couldn’t always be achieved because of competing hospital priorities, such as discharge timing.25 They also worried about giving medical information that would create cognitive overload for patients and/or require professional interpretation. Although providers in another study perceived little negative impact on their workflow after portal implementation, they worried about the potential of adding other information to the portal.35 For example, they were concerned that the future release of abnormal test results or sensitive data would lead to confusion and more time spent answering patient questions. Physicians also worried that secure messaging could be overused by patients, would be used to inappropriately express acute concerns, or might adversely affect verbal communication. Providers in 2 studies expressed concerns about potential negative implications of portal use on their work before implementation, which were subsequently reduced after portal implementation.29,38 Conversely, no parent portal users in another study thought portal information was confusing.33 One parent participant noted portal use may actually decrease anxiety: “Access to their medical information gives patients and their caregivers perspective and insight into their hospital care and empowers them with knowledge about [what is going on], which reduces anxiety.”37

DISCUSSION

We identified multiple studies evaluating the design, use, and impact of inpatient patient portals for hospitalized patients and caregivers. Based on the information needs identified by patients and healthcare team participants, multiple key content and design recommendations are suggested, including presenting (1) timely, personalized clinical and educational information in lay terms, (2) the care trajectory, including care plan and patient schedule, and (3) a way to recognize and communicate with the inpatient healthcare team. Design challenges still exist, such as translating medical terminology from EHRs into patient-friendly language, proxy access, and portal integration across transitions. Data from identified studies suggest hospitalized patients and caregivers are interested in and willing to use inpatient portals, but there is less information about the use of each functionality. Evidence supporting the role of inpatient portal use in improving patient and/or caregiver engagement, knowledge, communication, and the quality and safety of care is currently limited. Included studies indicate that healthcare team members had concerns about using portals to share clinical information and communicate electronically in the hospital. The extent to which these concerns translate to demonstrable problems remains to be seen.

Early studies focus on patient and caregiver information needs and portal interface design. Although the necessity for certain core functionalities and design requirements are becoming clear,20 best practices regarding the amount and timing of information released (eg, physician notes, lab results), optimal hardware decisions (eg, large-screen displays, hospital-owned tablets, bring-your-own-device model), and details around secure-messaging implementation in the acute hospital setting are still lacking. Future work is needed to understand optimal patient-provider communication architectures that support improved synchronous and asynchronous messaging and privacy-preserving approaches to the design of these systems to handle patient-generated data as it becomes more commonplace. Although patient participants in these studies were generally satisfied using inpatient portals, many indicated the need for even more transparency, such as the release of results in real time and inclusion of physician notes (even if they could not be fully comprehended).37 As the movement of sharing notes with patients in the ambulatory setting grows,39 it will inevitably extend to the inpatient setting.40 Further research is needed to understand the impact of increased transparency on health outcomes, patient anxiety, and inpatient healthcare team workload. Although the majority of studies described the design and/or use of custom portal platforms, EHR vendors are now developing inpatient portals that integrate into preexisting systems (eg, MyChart Bedside, Epic Systems). This will increase the likelihood of broad inpatient portal adoption and may facilitate multicenter trials evaluating the impact of their use.

The next steps will need to focus on the evaluation of specific inpatient portal functionalities and the impact of their use on objective process and outcome measures by using rigorous, experimental study designs. Akin to ambulatory portal research, measures of interest will include patient activation,41,42 patient and/or caregiver satisfaction,43 care processes (eg, length of stay, readmissions), and patient safety (eg, safety perceptions, adverse drug events, hospital-acquired conditions, and diagnostic errors). More than a mechanism for unidirectional sharing information from providers to the patient, inpatient portals will also provide a platform for the reciprocal exchange of information from the patient to the provider through patient-generated data, such as goal setting and feedback. Patients may play a larger role in reporting hospital satisfaction in real time, reconciling medications, contributing to the treatment plan, and identifying medical errors. As portals are integrated across the care continuum,20 our understanding of their impact may become more clear.

In this review, only 5 studies were conducted in the pediatric hospital setting.24,32-34,38 With hospitalized children experiencing 3 times more harm from medical errors than adults,44 engaging parents in inpatient care to improve safety has become a national priority.45 Giving patient portals, or “parent portals,” to parents of hospitalized children may provide a unique opportunity to share healthcare information and promote engagement, a direction for future study. There is also a research gap in evaluating adolescent inpatient portal use. Future portals may be designed to incentivize young children to learn about their hospitalization through games linked to health-related education.

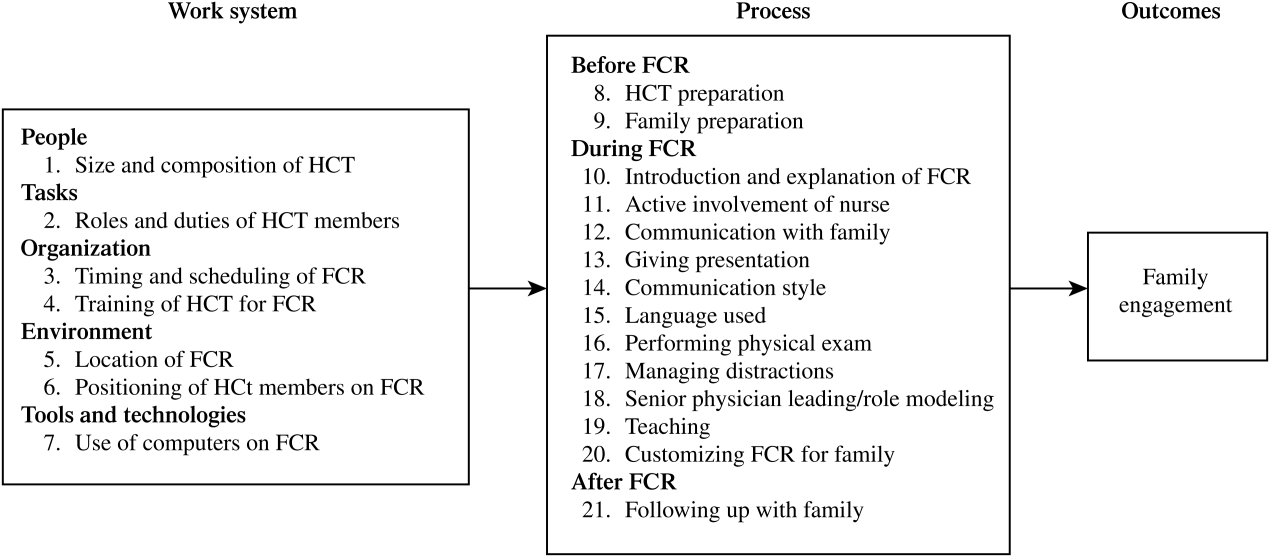

Finally, as patients and caregivers begin using inpatient portals, there will almost certainly be consequences for healthcare teams. Understanding and anticipating human and work system factors influencing inpatient portal adoption and use from the perspectives of both patients and healthcare teams are needed.46,47 Engaging healthcare team members as valuable stakeholders during implementation and measuring the impact of portal use on their workload is necessary, especially as portal use spreads beyond pilot units. The success of inpatient portals is dependent upon both the positive benefits for patients and their acceptance by healthcare teams.48

Limitations exist in conducting a systematic literature review.49 The conceptual definition of a portal for hospitalized patients and patient/caregiver engagement is evolving; therefore, our definition may not have captured all relevant studies. We intentionally did not include all inpatient technology, as we were interested in a narrow definition of portals designed for inpatients that provided clinical information from the inpatient EHR. Because of rapid technology changes, we also limited our search to studies published within the last 10 years; prior literature has been described elsewhere.17 We excluded non-English language studies, limiting our ability to capture the full scope of inpatient portal research. These patients already experience healthcare delivery disparities, widened by the inaccessibility of innovative health information technologies.50 Future studies would be enhanced with the inclusion of these participants.

Inpatient portal research is in its infancy but growing rapidly. Studies to date are primarily focused on portal design and have small sample sizes. Early findings suggest that patients and caregivers are, in general, enthusiastic about using inpatient portals. Further research is needed, however, to determine the impact of inpatient portal use on patient engagement and hospital-care quality, safety, and cost.

Disclosure

This work was supported by a Department of Pediatrics Research and Development Grant at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. This publication was also supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award program through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant UL1TR000427. Dr. Hoonakker’s involvement was also partially supported by the National Science Foundation, grant CMMI 1536987. Funding sources had no involvement in study design, analysis, or interpretation of data. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

1. Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796-804. PubMed

2. Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al. Observational study of effect of patient centredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice consultations. BMJ. 2001;323(7318):908-911. PubMed

3. Maeng DD, Graf TR, Davis DE, Tomcavage J, Bloom FJ, Jr. Can a patient-centered medical home lead to better patient outcomes? The Quality Implications of Geisinger’s ProvenHealth Navigator. Am J Med Qual. 2012;27(3):210-216. PubMed

4. Joint Commision on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations. Speak up: Prevent errors in your child’s care. http://www.jointcommission.org/Speak_Up_Prevent_Errors_in_Your_Childs_Care/. Accessed June 10, 2017.

5. Committee on Hospital Care and Institute for Patient and Family-centered Care. Patient- and family-centered care and the pediatrician’s role. Pediatrics. 2012;129(2):394-404. PubMed

6. Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001. PubMed

7. Coulter A. Engaging Patients in Healthcare. New York: McGraw-Hill Education; 2011. PubMed

8. Tang PC, Ash JS, Bates DW, Overhage JM, Sands DZ. Personal health records: definitions, benefits, and strategies for overcoming barriers to adoption. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13(2):121-126. PubMed

9. Schnipper JL, Gandhi TK, Wald JS, et al. Design and implementation of a web-based patient portal linked to an electronic health record designed to improve medication safety: the Patient Gateway medications module. Inform Prim Care. 2008;16(2):147-155. PubMed

10. Blumenthal D, Tavenner M. The “meaningful use” regulation for electronic health records. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(6):501-504. PubMed

11. Ammenwerth E, Schnell-Inderst P, Hoerbst A. The impact of electronic patient portals on patient care: a systematic review of controlled trials. J Med Internet Res. 2012;14(6):e162. PubMed

12. Goldzweig CL, Orshansky G, Paige NM, et al. Electronic patient portals: evidence on health utcomes, satisfaction, efficiency, and attitudes: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2013;159(10):677-687. PubMed

13. Davis Giardina T, Menon S, Parrish DE, Sittig DF, Singh H. Patient access to medical records and healthcare outcomes: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(4):737-741. PubMed

14. Kalra D, Fernando B. A review of the empirical evidence of the healthcare benefits of personal health records. Yearb Med Inform. 2013;8(1):93-102. PubMed

15. Kruse CS, Bolton K, Freriks G. The effect of patient portals on quality outcomes and its implications to meaningful use: a systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2015;17(2):e44. PubMed

16. Vawdrey DK, Wilcox LG, Collins SA, et al. A tablet computer application for patients to participate in their hospital care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2011:1428-1435. PubMed

17. Prey JE, Woollen J, Wilcox L, et al. Patient engagement in the inpatient setting: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2014;21(4):742-750. PubMed

18. O’Leary KJ, Lohman ME, Culver E, et al. The effect of tablet computers with a mobile patient portal application on hospitalized patients’ knowledge and activation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(1):159-165. PubMed

19. Skeels M, Tan DS. Identifying opportunities for inpatient-centric technology. Proceedings of the 1st ACM International Health Informatics Symposium. Arlington: ACM; 2010:580-589.

20. Collins SA, Rozenblum R, Leung WY, et al. Acute care patient portals: a qualitative study of stakeholder perspectives on current practices. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(e1):e9-e17. PubMed

21. Morris D, Karlson A. Dynamic Accessibility Requirements for Hospital Patients. SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. Vancouver, BC, Canada: ACM; 2011.

22. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009;339:b2535. PubMed

23. Downs SH, Black N. The feasibility of creating a checklist for the assessment of the methodological quality both of randomised and non-randomised studies of health care interventions. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52(6):377-384. PubMed

24. Weyand SA, Frize M, Bariciak E, Dunn S. Development and usability testing of a parent decision support tool for the neonatal intensive care unit. Conf Proc IEEE Eng Med Biol Soc. 2011:6430-6433. PubMed

25. Caligtan CA, Carroll DL, Hurley AC, Gersh-Zaremski R, Dykes PC. Bedside information technology to support patient-centered care. Int J Med Inform. 2012;81(7):442-451. PubMed

26. Wilcox L, Feiner S, Liu A, Restaino S, Collins S, Vawdrey D. Designing inpatient technology to meet the medication information needs of cardiology patients. Proceedings of the 2nd ACM SIGHIT International Health Informatics Symposium. Miami: ACM; 2012:831-836. PubMed

27. Dykes PC, Carroll DL, Hurley AC, et al. Building and testing a patient-centric electronic bedside communication center. J Gerontol Nurs. 2013;39(1):15-19. PubMed

28. Dykes PC, Stade D, Chang F, et al. Participatory design and development of a patient-centered toolkit to engage hospitalized patients and care partners in their plan of care. AMIA Annu Symp Proc. 2014:486-495. PubMed

29. Pell JM, Mancuso M, Limon S, Oman K, Lin CT. Patient access to electronic health records during hospitalization. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(5):856-858. PubMed

30. Yoo S, Lee KH, Baek H, et al. Development and user research of a smart bedside station system toward patient-centered healthcare system. J Med Syst. 2015;39(9):86. PubMed

31. Dalal AK, Dykes PC, Collins S, et al. A web-based, patient-centered toolkit to engage patients and caregivers in the acute care setting: a preliminary evaluation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(1):80-87. PubMed

32. Kaziunas E, Hanauer DA, Ackerman MS, Choi SW. Identifying unmet informational needs in the inpatient setting to increase patient and caregiver engagement in the context of pediatric hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(1):94-104. PubMed

33. Kelly MM, Hoonakker PLT, Dean SM. Using an inpatient portal to engage families in pediatric hospital care. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;24(1):153-161. PubMed

34. Maher M, Kaziunas E, Ackerman M, et al. User-centered design groups to engage patients and caregivers with a personalized health information technology tool. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016;22(2):349-358. PubMed

35. O’Leary KJ, Sharma RK, Killarney A, et al. Patients’ and healthcare providers’ perceptions of a mobile portal application for hospitalized patients. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16(1):123-130. PubMed

36. Wilcox L, Woollen J, Prey J, et al. Interactive tools for inpatient medication tracking: a multi-phase study with cardiothoracic surgery patients. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(1):144-158. PubMed

37. Woollen J, Prey J, Wilcox L, et al. Patient experiences using an inpatient personal health record. Appl Clin Inform. 2016;7(2):446-460. PubMed

38. Kelly MM, Dean SM, Carayon P, Wetterneck TB, Hoonakker PLT. Healthcare team perceptions of a portal for parents of hospitalized children before and after implementation. Appl Clin Inform. 2017;8(1):265-278. PubMed

39. Wolff JL, Darer JD, Berger A, et al. Inviting patients and care partners to read doctors’ notes: OpenNotes and shared access to electronic medical records. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2017;24(e1):e166-e172. PubMed

40. Feldman HJ, Walker J, Li J, Delbanco T. OpenNotes:hospitalists’ challenge and opportunity. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(7):414-417. PubMed

41. Hibbard JH, Stockard J, Mahoney ER, Tusler M. Development of the Patient Activation Measure (PAM): conceptualizing and measuring activation in patients and consumers. Health Serv Res. 2004;39(4 Pt 1):1005-1026. PubMed

42. Prey JE, Qian M, Restaino S, et al. Reliability and validity of the patient activation measure in hospitalized patients. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(12):2026-2033. PubMed

43. Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, Elliott MN, et al. The development of a pediatric inpatient experience of care measure: Child HCAHPS. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):360-369. PubMed

44. Kaushal R, Bates DW, Landrigan C, et al. Medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients. JAMA. 2001;285(16):2114-2120. PubMed

45. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. 20 Tips to help prevent medical errors in children. Secondary 20 Tips to help prevent medical errors in children. http://www.ahrq.gov/patients-consumers/care-planning/errors/20tips/index.html. Accessed on June 10, 2017.

46. Thompson MJ, Reilly JD, Valdez RS. Work system barriers to patient, provider, and caregiver use of personal health records: A systematic review. Appl Ergon. 2016;54:218-242. PubMed

47. Holden RJ, Carayon P, Gurses AP, et al. SEIPS 2.0: a human factors framework for studying and improving the work of healthcare professionals and patients. Ergonomics. 2013;56(11):1669-1686. PubMed

48. Gagnon MP, Ngangue P, Payne-Gagnon J, Desmartis M. m-Health adoption by healthcare professionals: a systematic review. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016;23(1):212-220. PubMed

49. Russell CL. An overview of the integrative research review. Prog Transplant. 2005;15(1):8-13. PubMed

50. Yamin CK, Emani S, Williams DH, et al. The digital divide in adoption and use of a personal health record. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(6):568-574. PubMed

Engaging patients and their caregivers in care improves health outcomes1-3 and is endorsed by leading healthcare organizations as essential to improving care quality and safety.4-6 Patient engagement emphasizes that patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers work together to “promote and support active patient and public involvement in health and healthcare and to strengthen their influence on healthcare decisions.”7 Patient portals, web-based personal health records linked to electronic health record (EHR) data, are intended to promote engagement by providing patients and their caregivers with timely electronic access to their healthcare information and supporting communication through secure messaging with their healthcare team.8 The use of patient portals has also been suggested as a way for patients and/or caregivers to identify and intercept medical errors, thus having the potential to also improve patient safety.8,9

As a requirement for meaningful use, access to health information through patient portals in the ambulatory setting has increased dramatically.10 Studies evaluating the use of these patient portals to promote patient-centered care are growing, but evidence supporting their impact on improved health outcomes is currently insufficient.11-15 Although research and policy focus on the use of patient portals in the ambulatory setting, recent literature suggests that patient portals may be used to share inpatient clinical information to engage patients and their caregivers during their hospitalization.16-18 Before the widespread use of patient portals in the inpatient setting is endorsed, systematic research is needed to understand optimal portal design requirements, if and how these portals are used, and whether their use provides value to the hospitalized patient and/or caregiver.8

Prior literature summarized early findings regarding the use of various technologies designed to engage hospitalized patients.17,19,20 In this systematic review, we describe the emerging literature examining the design, use, and impact of inpatient portals for hospitalized patients and/or caregivers over the last 10 years. Inpatient portals are defined here as electronic patient portals tethered to EHRs that are designed to provide hospitalized patients and/or caregivers secure access to personalized, inpatient clinical information with the intent of engaging them in their hospital care. After analyzing and summarizing these data, we then identify knowledge gaps and potential future research directions.

METHODS

Search Strategy, Study Selection, and Analysis

This systematic review included available, peer-reviewed, and grey literature published from January 1, 2006, to August 8, 2017, in PubMed, Web of Science (including the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Xplore), Cochrane, CINAHLPlus, and Scopus databases. Terms and phrases, including those found in the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) index, were used to identify studies evaluating (1) patient portals (“health record, personal [MeSH],” “personal health record,” “patient portal,” “inpatient portal,” “ipad,” “tablet,” or “bedside information technology”), (2) engagement (“engagement,” “empowerment,” “participation,” “activation,” or “self-efficacy”), and (3) in the hospital (“inpatient [MeSH],” “hospital [MeSH],” “hospitalized patient [MeSH],” or “unit”). MeSH terms were used when applicable. Based on previous literature, free-text terms were also used when subject headings were not applied consistently, such as with terms related to engagement.17,21 Studies were excluded if they were not written in English, if they evaluated portals exclusively in the emergency department or ambulatory setting, and/or if they described future study protocols. Studies describing general inpatient technology or evaluating portals used in the hospital but not tethered to inpatient EHR clinical data were also excluded.

By using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines,22 2 researchers (M.K. and P.H.) completed the literature search and potential article screening. Results were aggregated and studies were screened and excluded from full review based on title and abstract information. Additional studies were included after reference list review. During a full review of included studies, 2 researchers independently extracted data, including the study objective, design, setting, sample, data collection instruments, outcomes, and a description of results. Guided by our study objective, findings were reconciled by consensus and analyzed and described according to the following 3 themes: (1) inpatient portal design, (2) inpatient portal use and usability, and (3) the impact of inpatient portal use on patient or caregiver and healthcare team outcomes as defined by retrieved studies.

The quality of studies was evaluated by the same 2 researchers independently by using the Downs and Black checklist for assessing the methodological quality of randomized and nonrandomized healthcare interventions.23 Qualitative studies describing the development of portal prototypes and/or portal redesign efforts were excluded from these analyses. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.Because of the wide variability in study designs, populations, and outcomes, a meta-analysis of pooled data was not performed.

RESULTS

Of the 731 studies identified through database searching and reference review, 36 were included for full-text review and 17 met inclusion criteria (Figure; Table 1). Studies excluded after full-text review described portal use outside of the inpatient setting, portals not linked to hospital EHR clinical data, portals not designed for inpatients, and/or inpatient technology in general. The inpatient portal platforms, hardware used, and functionalities varied within included studies (Table 2). The majority of studies used custom, web-based inpatient portal applications on tablet computers. Most provided information about the patients’ hospital medications, healthcare team, and education about their condition and/or a medical glossary. Many included the patient’s schedule, hospital problem list, discharge information, and a way to keep notes.

There has been a recent increase in inpatient portal study publication, with 9 studies published during or after 2016. Five were conducted in the pediatric setting and all but 130 with English-speaking participants. Twelve studies were qualitative, many of which were conducted in multiple phases by using semi-structured interviews and/or focus groups to develop or redesign inpatient portals. Of the remaining studies, 3 used a cross-sectional design, 1 used a before and after design without a control group, and 1 was a nonrandomized trial. Studies were rated as having medium-to-high risk of bias because of design flaws (Table 1 in supplementary Appendix). Because many studies were small pilot studies and all were single-centered studies, the generalizability of findings to different healthcare settings or patient populations is limited.

Inpatient Portal Design

Most included studies evaluated patient and/or caregiver information needs to design and/or enhance inpatient portals.16,24-37 In 1 study, patients described an overall lack of information provided in the hospital and insufficient time to understand and remember information, which, when shared, was often presented by using medical terminology.30 They wanted information to help them understand their daily hospital routine, confirm and compare medications and test results, learn about care, and prepare for discharge. Participants in multiple studies echoed these results, indicating the need for a schedule of upcoming clinical events (eg, medication administration, procedures, imaging), secure and timely clinical information (eg, list of diagnoses and medications, test results), personalized education, a medical glossary, discharge information, and a way to take notes and recognize and communicate with providers.

Patients also requested further information transparency,34,37 including physicians’ notes, radiology results, operative reports, and billing information, along with general hospital information,16 meal ordering,33 and video conferencing.27 ln designing and refining an inpatient medication-tracking tool, participants identified the need for information about medication dosage, frequency, timing, administration method, criticality, alternative medications or forms, and education.26,36 Patients and/or caregivers also indicated interest in communicating with inpatient providers by using the portal.16,27,28,30-37 In 1 study, patients highlighted the need to be involved in care plan development,27 which led to portal refinement to allow for patient-generated data entry, including care goals and a way to communicate real-time concerns and feedback.28

Studies also considered healthcare team perspectives to inform portal design.25,26,28,30,35,37 Although information needs usually overlapped, patient and healthcare team priorities differed in some areas. Although patients wanted to “know what was going to happen to them,” nurses in 1 study were more concerned about providing information to protect patients, such as safety and precaution materials.25 Similarly, when designing a medication-tracking tool, patients sought information that helped them understand what to expect, while pharmacists focused on medication safety and providing information that fit their workflow (eg, abstract medication schedules).36

Identified study data raised important portal interface design considerations. Results suggested clinical data should be presented by using simple displays,28 accommodating real-time information. Participants recommended links16,29 to personalized patient-friendly37 education accessed with minimal steps.26 Interfaces may be personalized for target users, such as patient or proxy and younger or older individuals. For example, older patients reported less familiarity with touch screens, internal keyboards, and handwriting recognition, favoring voice recognition for recording notes.27 This raised questions about how portals can be designed to best maintain patient privacy.25 Interface design, such as navigation, also relied heavily on hardware choice, such as tablet versus mobile phone.28

Inpatient Portal Use and Usability

Most patient and/or caregiver participants in included studies were interested in using an inpatient portal, used it when offered, found it easy to use, useful, and/or were satisfied with it.16,18,24-37 Most used and liked functionalities that provided healthcare team, test result, and medication information.22,33,37 In the 1 identified controlled trial,18 researchers evaluated an inpatient portal given to adult inpatients that included a problem list, schedule, medication list, and healthcare team information. Of the intervention unit patients, 80% used the portal, 76% indicated it was easy to use, and 71% thought it provided useful information. When a portal was given to 239 adult patients and caregivers in another study, 66% sent a total of 291 messages to the healthcare team.31 Of these, 153 provided feedback, 76 expressed preferences, and 16 communicated concerns. In a pediatric study, an inpatient portal was given to 296 parents who sent a total of 36 messages and 176 requests.33 Messages sent included information regarding caregiver needs, questions, updates, and/or positive endorsements of the healthcare team and/or care.

Impact of Inpatient Portal Use

Multiple studies evaluated the impact of inpatient portal use on patient and/or caregiver engagement, empowerment, activation, and/or knowledge, which had mixed results. Most adult patients interviewed in one study had positive experiences using a portal to answer their questions between physician visits and learn about, remember, and engage in care.37 A majority of adult inpatient portal users in another study agreed that portal use helped them feel in control and understand their condition; however, they did not report having improved discharge timing knowledge.29 In a pediatric study, most parent inpatient portal users agreed use improved their ability to monitor, understand, and make decisions about their child’s care.33 In the controlled trial,18 a higher percentage of portal intervention patients could identify their physician or role; however, patient activation was not statistically different between intervention and control patients.

Results from included studies also evaluated the impact of portal use on communication. Some suggest inpatient portal use may replace and/or facilitate verbal communication between patients, caregivers, and providers.35 In a pediatric study, 51% of parent portal users reported it gave them the information they needed, reducing the amount of questions they had for their healthcare team.33 Similarly 43% of 14 adult inpatient portal users in another study thought the portal could replace at least some face-to-face communication.37 Some providers indicated portal use enhanced rounding discussion quality.35 Another study suggested that patient-provider communication via electronic messaging may provide benefits for some patients and not others.37

Multiple studies evaluated patient, caregiver, and/or healthcare team perceptions of the impact of inpatient portal use on detection of errors and patient safety.29,31,33,35 In adult inpatients, 6% agreed portal use could help them find errors.29 In a pediatric study, 8% reported finding at least 1 medication error by using the portal, and 89% thought use reduced errors in their child’s care.33 One patient in a qualitative study of adult inpatients cited an example of a dosing error discovered by using the portal.37 Healthcare providers in another study also reported that use facilitated patient error identification.35

Included studies evaluated the potential impact of portal use on patient anxiety, confusion, and/or worry, and the work of healthcare teams. In 1 study, nurses voiced concerns about giving information subject to change or that couldn’t always be achieved because of competing hospital priorities, such as discharge timing.25 They also worried about giving medical information that would create cognitive overload for patients and/or require professional interpretation. Although providers in another study perceived little negative impact on their workflow after portal implementation, they worried about the potential of adding other information to the portal.35 For example, they were concerned that the future release of abnormal test results or sensitive data would lead to confusion and more time spent answering patient questions. Physicians also worried that secure messaging could be overused by patients, would be used to inappropriately express acute concerns, or might adversely affect verbal communication. Providers in 2 studies expressed concerns about potential negative implications of portal use on their work before implementation, which were subsequently reduced after portal implementation.29,38 Conversely, no parent portal users in another study thought portal information was confusing.33 One parent participant noted portal use may actually decrease anxiety: “Access to their medical information gives patients and their caregivers perspective and insight into their hospital care and empowers them with knowledge about [what is going on], which reduces anxiety.”37

DISCUSSION

We identified multiple studies evaluating the design, use, and impact of inpatient patient portals for hospitalized patients and caregivers. Based on the information needs identified by patients and healthcare team participants, multiple key content and design recommendations are suggested, including presenting (1) timely, personalized clinical and educational information in lay terms, (2) the care trajectory, including care plan and patient schedule, and (3) a way to recognize and communicate with the inpatient healthcare team. Design challenges still exist, such as translating medical terminology from EHRs into patient-friendly language, proxy access, and portal integration across transitions. Data from identified studies suggest hospitalized patients and caregivers are interested in and willing to use inpatient portals, but there is less information about the use of each functionality. Evidence supporting the role of inpatient portal use in improving patient and/or caregiver engagement, knowledge, communication, and the quality and safety of care is currently limited. Included studies indicate that healthcare team members had concerns about using portals to share clinical information and communicate electronically in the hospital. The extent to which these concerns translate to demonstrable problems remains to be seen.

Early studies focus on patient and caregiver information needs and portal interface design. Although the necessity for certain core functionalities and design requirements are becoming clear,20 best practices regarding the amount and timing of information released (eg, physician notes, lab results), optimal hardware decisions (eg, large-screen displays, hospital-owned tablets, bring-your-own-device model), and details around secure-messaging implementation in the acute hospital setting are still lacking. Future work is needed to understand optimal patient-provider communication architectures that support improved synchronous and asynchronous messaging and privacy-preserving approaches to the design of these systems to handle patient-generated data as it becomes more commonplace. Although patient participants in these studies were generally satisfied using inpatient portals, many indicated the need for even more transparency, such as the release of results in real time and inclusion of physician notes (even if they could not be fully comprehended).37 As the movement of sharing notes with patients in the ambulatory setting grows,39 it will inevitably extend to the inpatient setting.40 Further research is needed to understand the impact of increased transparency on health outcomes, patient anxiety, and inpatient healthcare team workload. Although the majority of studies described the design and/or use of custom portal platforms, EHR vendors are now developing inpatient portals that integrate into preexisting systems (eg, MyChart Bedside, Epic Systems). This will increase the likelihood of broad inpatient portal adoption and may facilitate multicenter trials evaluating the impact of their use.

The next steps will need to focus on the evaluation of specific inpatient portal functionalities and the impact of their use on objective process and outcome measures by using rigorous, experimental study designs. Akin to ambulatory portal research, measures of interest will include patient activation,41,42 patient and/or caregiver satisfaction,43 care processes (eg, length of stay, readmissions), and patient safety (eg, safety perceptions, adverse drug events, hospital-acquired conditions, and diagnostic errors). More than a mechanism for unidirectional sharing information from providers to the patient, inpatient portals will also provide a platform for the reciprocal exchange of information from the patient to the provider through patient-generated data, such as goal setting and feedback. Patients may play a larger role in reporting hospital satisfaction in real time, reconciling medications, contributing to the treatment plan, and identifying medical errors. As portals are integrated across the care continuum,20 our understanding of their impact may become more clear.

In this review, only 5 studies were conducted in the pediatric hospital setting.24,32-34,38 With hospitalized children experiencing 3 times more harm from medical errors than adults,44 engaging parents in inpatient care to improve safety has become a national priority.45 Giving patient portals, or “parent portals,” to parents of hospitalized children may provide a unique opportunity to share healthcare information and promote engagement, a direction for future study. There is also a research gap in evaluating adolescent inpatient portal use. Future portals may be designed to incentivize young children to learn about their hospitalization through games linked to health-related education.

Finally, as patients and caregivers begin using inpatient portals, there will almost certainly be consequences for healthcare teams. Understanding and anticipating human and work system factors influencing inpatient portal adoption and use from the perspectives of both patients and healthcare teams are needed.46,47 Engaging healthcare team members as valuable stakeholders during implementation and measuring the impact of portal use on their workload is necessary, especially as portal use spreads beyond pilot units. The success of inpatient portals is dependent upon both the positive benefits for patients and their acceptance by healthcare teams.48

Limitations exist in conducting a systematic literature review.49 The conceptual definition of a portal for hospitalized patients and patient/caregiver engagement is evolving; therefore, our definition may not have captured all relevant studies. We intentionally did not include all inpatient technology, as we were interested in a narrow definition of portals designed for inpatients that provided clinical information from the inpatient EHR. Because of rapid technology changes, we also limited our search to studies published within the last 10 years; prior literature has been described elsewhere.17 We excluded non-English language studies, limiting our ability to capture the full scope of inpatient portal research. These patients already experience healthcare delivery disparities, widened by the inaccessibility of innovative health information technologies.50 Future studies would be enhanced with the inclusion of these participants.

Inpatient portal research is in its infancy but growing rapidly. Studies to date are primarily focused on portal design and have small sample sizes. Early findings suggest that patients and caregivers are, in general, enthusiastic about using inpatient portals. Further research is needed, however, to determine the impact of inpatient portal use on patient engagement and hospital-care quality, safety, and cost.

Disclosure

This work was supported by a Department of Pediatrics Research and Development Grant at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. This publication was also supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award program through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant UL1TR000427. Dr. Hoonakker’s involvement was also partially supported by the National Science Foundation, grant CMMI 1536987. Funding sources had no involvement in study design, analysis, or interpretation of data. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Engaging patients and their caregivers in care improves health outcomes1-3 and is endorsed by leading healthcare organizations as essential to improving care quality and safety.4-6 Patient engagement emphasizes that patients, caregivers, and healthcare providers work together to “promote and support active patient and public involvement in health and healthcare and to strengthen their influence on healthcare decisions.”7 Patient portals, web-based personal health records linked to electronic health record (EHR) data, are intended to promote engagement by providing patients and their caregivers with timely electronic access to their healthcare information and supporting communication through secure messaging with their healthcare team.8 The use of patient portals has also been suggested as a way for patients and/or caregivers to identify and intercept medical errors, thus having the potential to also improve patient safety.8,9

As a requirement for meaningful use, access to health information through patient portals in the ambulatory setting has increased dramatically.10 Studies evaluating the use of these patient portals to promote patient-centered care are growing, but evidence supporting their impact on improved health outcomes is currently insufficient.11-15 Although research and policy focus on the use of patient portals in the ambulatory setting, recent literature suggests that patient portals may be used to share inpatient clinical information to engage patients and their caregivers during their hospitalization.16-18 Before the widespread use of patient portals in the inpatient setting is endorsed, systematic research is needed to understand optimal portal design requirements, if and how these portals are used, and whether their use provides value to the hospitalized patient and/or caregiver.8

Prior literature summarized early findings regarding the use of various technologies designed to engage hospitalized patients.17,19,20 In this systematic review, we describe the emerging literature examining the design, use, and impact of inpatient portals for hospitalized patients and/or caregivers over the last 10 years. Inpatient portals are defined here as electronic patient portals tethered to EHRs that are designed to provide hospitalized patients and/or caregivers secure access to personalized, inpatient clinical information with the intent of engaging them in their hospital care. After analyzing and summarizing these data, we then identify knowledge gaps and potential future research directions.

METHODS

Search Strategy, Study Selection, and Analysis

This systematic review included available, peer-reviewed, and grey literature published from January 1, 2006, to August 8, 2017, in PubMed, Web of Science (including the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Xplore), Cochrane, CINAHLPlus, and Scopus databases. Terms and phrases, including those found in the Medical Subject Heading (MeSH) index, were used to identify studies evaluating (1) patient portals (“health record, personal [MeSH],” “personal health record,” “patient portal,” “inpatient portal,” “ipad,” “tablet,” or “bedside information technology”), (2) engagement (“engagement,” “empowerment,” “participation,” “activation,” or “self-efficacy”), and (3) in the hospital (“inpatient [MeSH],” “hospital [MeSH],” “hospitalized patient [MeSH],” or “unit”). MeSH terms were used when applicable. Based on previous literature, free-text terms were also used when subject headings were not applied consistently, such as with terms related to engagement.17,21 Studies were excluded if they were not written in English, if they evaluated portals exclusively in the emergency department or ambulatory setting, and/or if they described future study protocols. Studies describing general inpatient technology or evaluating portals used in the hospital but not tethered to inpatient EHR clinical data were also excluded.

By using the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses guidelines,22 2 researchers (M.K. and P.H.) completed the literature search and potential article screening. Results were aggregated and studies were screened and excluded from full review based on title and abstract information. Additional studies were included after reference list review. During a full review of included studies, 2 researchers independently extracted data, including the study objective, design, setting, sample, data collection instruments, outcomes, and a description of results. Guided by our study objective, findings were reconciled by consensus and analyzed and described according to the following 3 themes: (1) inpatient portal design, (2) inpatient portal use and usability, and (3) the impact of inpatient portal use on patient or caregiver and healthcare team outcomes as defined by retrieved studies.

The quality of studies was evaluated by the same 2 researchers independently by using the Downs and Black checklist for assessing the methodological quality of randomized and nonrandomized healthcare interventions.23 Qualitative studies describing the development of portal prototypes and/or portal redesign efforts were excluded from these analyses. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus.Because of the wide variability in study designs, populations, and outcomes, a meta-analysis of pooled data was not performed.

RESULTS

Of the 731 studies identified through database searching and reference review, 36 were included for full-text review and 17 met inclusion criteria (Figure; Table 1). Studies excluded after full-text review described portal use outside of the inpatient setting, portals not linked to hospital EHR clinical data, portals not designed for inpatients, and/or inpatient technology in general. The inpatient portal platforms, hardware used, and functionalities varied within included studies (Table 2). The majority of studies used custom, web-based inpatient portal applications on tablet computers. Most provided information about the patients’ hospital medications, healthcare team, and education about their condition and/or a medical glossary. Many included the patient’s schedule, hospital problem list, discharge information, and a way to keep notes.

There has been a recent increase in inpatient portal study publication, with 9 studies published during or after 2016. Five were conducted in the pediatric setting and all but 130 with English-speaking participants. Twelve studies were qualitative, many of which were conducted in multiple phases by using semi-structured interviews and/or focus groups to develop or redesign inpatient portals. Of the remaining studies, 3 used a cross-sectional design, 1 used a before and after design without a control group, and 1 was a nonrandomized trial. Studies were rated as having medium-to-high risk of bias because of design flaws (Table 1 in supplementary Appendix). Because many studies were small pilot studies and all were single-centered studies, the generalizability of findings to different healthcare settings or patient populations is limited.

Inpatient Portal Design

Most included studies evaluated patient and/or caregiver information needs to design and/or enhance inpatient portals.16,24-37 In 1 study, patients described an overall lack of information provided in the hospital and insufficient time to understand and remember information, which, when shared, was often presented by using medical terminology.30 They wanted information to help them understand their daily hospital routine, confirm and compare medications and test results, learn about care, and prepare for discharge. Participants in multiple studies echoed these results, indicating the need for a schedule of upcoming clinical events (eg, medication administration, procedures, imaging), secure and timely clinical information (eg, list of diagnoses and medications, test results), personalized education, a medical glossary, discharge information, and a way to take notes and recognize and communicate with providers.

Patients also requested further information transparency,34,37 including physicians’ notes, radiology results, operative reports, and billing information, along with general hospital information,16 meal ordering,33 and video conferencing.27 ln designing and refining an inpatient medication-tracking tool, participants identified the need for information about medication dosage, frequency, timing, administration method, criticality, alternative medications or forms, and education.26,36 Patients and/or caregivers also indicated interest in communicating with inpatient providers by using the portal.16,27,28,30-37 In 1 study, patients highlighted the need to be involved in care plan development,27 which led to portal refinement to allow for patient-generated data entry, including care goals and a way to communicate real-time concerns and feedback.28

Studies also considered healthcare team perspectives to inform portal design.25,26,28,30,35,37 Although information needs usually overlapped, patient and healthcare team priorities differed in some areas. Although patients wanted to “know what was going to happen to them,” nurses in 1 study were more concerned about providing information to protect patients, such as safety and precaution materials.25 Similarly, when designing a medication-tracking tool, patients sought information that helped them understand what to expect, while pharmacists focused on medication safety and providing information that fit their workflow (eg, abstract medication schedules).36

Identified study data raised important portal interface design considerations. Results suggested clinical data should be presented by using simple displays,28 accommodating real-time information. Participants recommended links16,29 to personalized patient-friendly37 education accessed with minimal steps.26 Interfaces may be personalized for target users, such as patient or proxy and younger or older individuals. For example, older patients reported less familiarity with touch screens, internal keyboards, and handwriting recognition, favoring voice recognition for recording notes.27 This raised questions about how portals can be designed to best maintain patient privacy.25 Interface design, such as navigation, also relied heavily on hardware choice, such as tablet versus mobile phone.28

Inpatient Portal Use and Usability

Most patient and/or caregiver participants in included studies were interested in using an inpatient portal, used it when offered, found it easy to use, useful, and/or were satisfied with it.16,18,24-37 Most used and liked functionalities that provided healthcare team, test result, and medication information.22,33,37 In the 1 identified controlled trial,18 researchers evaluated an inpatient portal given to adult inpatients that included a problem list, schedule, medication list, and healthcare team information. Of the intervention unit patients, 80% used the portal, 76% indicated it was easy to use, and 71% thought it provided useful information. When a portal was given to 239 adult patients and caregivers in another study, 66% sent a total of 291 messages to the healthcare team.31 Of these, 153 provided feedback, 76 expressed preferences, and 16 communicated concerns. In a pediatric study, an inpatient portal was given to 296 parents who sent a total of 36 messages and 176 requests.33 Messages sent included information regarding caregiver needs, questions, updates, and/or positive endorsements of the healthcare team and/or care.

Impact of Inpatient Portal Use

Multiple studies evaluated the impact of inpatient portal use on patient and/or caregiver engagement, empowerment, activation, and/or knowledge, which had mixed results. Most adult patients interviewed in one study had positive experiences using a portal to answer their questions between physician visits and learn about, remember, and engage in care.37 A majority of adult inpatient portal users in another study agreed that portal use helped them feel in control and understand their condition; however, they did not report having improved discharge timing knowledge.29 In a pediatric study, most parent inpatient portal users agreed use improved their ability to monitor, understand, and make decisions about their child’s care.33 In the controlled trial,18 a higher percentage of portal intervention patients could identify their physician or role; however, patient activation was not statistically different between intervention and control patients.

Results from included studies also evaluated the impact of portal use on communication. Some suggest inpatient portal use may replace and/or facilitate verbal communication between patients, caregivers, and providers.35 In a pediatric study, 51% of parent portal users reported it gave them the information they needed, reducing the amount of questions they had for their healthcare team.33 Similarly 43% of 14 adult inpatient portal users in another study thought the portal could replace at least some face-to-face communication.37 Some providers indicated portal use enhanced rounding discussion quality.35 Another study suggested that patient-provider communication via electronic messaging may provide benefits for some patients and not others.37

Multiple studies evaluated patient, caregiver, and/or healthcare team perceptions of the impact of inpatient portal use on detection of errors and patient safety.29,31,33,35 In adult inpatients, 6% agreed portal use could help them find errors.29 In a pediatric study, 8% reported finding at least 1 medication error by using the portal, and 89% thought use reduced errors in their child’s care.33 One patient in a qualitative study of adult inpatients cited an example of a dosing error discovered by using the portal.37 Healthcare providers in another study also reported that use facilitated patient error identification.35

Included studies evaluated the potential impact of portal use on patient anxiety, confusion, and/or worry, and the work of healthcare teams. In 1 study, nurses voiced concerns about giving information subject to change or that couldn’t always be achieved because of competing hospital priorities, such as discharge timing.25 They also worried about giving medical information that would create cognitive overload for patients and/or require professional interpretation. Although providers in another study perceived little negative impact on their workflow after portal implementation, they worried about the potential of adding other information to the portal.35 For example, they were concerned that the future release of abnormal test results or sensitive data would lead to confusion and more time spent answering patient questions. Physicians also worried that secure messaging could be overused by patients, would be used to inappropriately express acute concerns, or might adversely affect verbal communication. Providers in 2 studies expressed concerns about potential negative implications of portal use on their work before implementation, which were subsequently reduced after portal implementation.29,38 Conversely, no parent portal users in another study thought portal information was confusing.33 One parent participant noted portal use may actually decrease anxiety: “Access to their medical information gives patients and their caregivers perspective and insight into their hospital care and empowers them with knowledge about [what is going on], which reduces anxiety.”37

DISCUSSION

We identified multiple studies evaluating the design, use, and impact of inpatient patient portals for hospitalized patients and caregivers. Based on the information needs identified by patients and healthcare team participants, multiple key content and design recommendations are suggested, including presenting (1) timely, personalized clinical and educational information in lay terms, (2) the care trajectory, including care plan and patient schedule, and (3) a way to recognize and communicate with the inpatient healthcare team. Design challenges still exist, such as translating medical terminology from EHRs into patient-friendly language, proxy access, and portal integration across transitions. Data from identified studies suggest hospitalized patients and caregivers are interested in and willing to use inpatient portals, but there is less information about the use of each functionality. Evidence supporting the role of inpatient portal use in improving patient and/or caregiver engagement, knowledge, communication, and the quality and safety of care is currently limited. Included studies indicate that healthcare team members had concerns about using portals to share clinical information and communicate electronically in the hospital. The extent to which these concerns translate to demonstrable problems remains to be seen.

Early studies focus on patient and caregiver information needs and portal interface design. Although the necessity for certain core functionalities and design requirements are becoming clear,20 best practices regarding the amount and timing of information released (eg, physician notes, lab results), optimal hardware decisions (eg, large-screen displays, hospital-owned tablets, bring-your-own-device model), and details around secure-messaging implementation in the acute hospital setting are still lacking. Future work is needed to understand optimal patient-provider communication architectures that support improved synchronous and asynchronous messaging and privacy-preserving approaches to the design of these systems to handle patient-generated data as it becomes more commonplace. Although patient participants in these studies were generally satisfied using inpatient portals, many indicated the need for even more transparency, such as the release of results in real time and inclusion of physician notes (even if they could not be fully comprehended).37 As the movement of sharing notes with patients in the ambulatory setting grows,39 it will inevitably extend to the inpatient setting.40 Further research is needed to understand the impact of increased transparency on health outcomes, patient anxiety, and inpatient healthcare team workload. Although the majority of studies described the design and/or use of custom portal platforms, EHR vendors are now developing inpatient portals that integrate into preexisting systems (eg, MyChart Bedside, Epic Systems). This will increase the likelihood of broad inpatient portal adoption and may facilitate multicenter trials evaluating the impact of their use.

The next steps will need to focus on the evaluation of specific inpatient portal functionalities and the impact of their use on objective process and outcome measures by using rigorous, experimental study designs. Akin to ambulatory portal research, measures of interest will include patient activation,41,42 patient and/or caregiver satisfaction,43 care processes (eg, length of stay, readmissions), and patient safety (eg, safety perceptions, adverse drug events, hospital-acquired conditions, and diagnostic errors). More than a mechanism for unidirectional sharing information from providers to the patient, inpatient portals will also provide a platform for the reciprocal exchange of information from the patient to the provider through patient-generated data, such as goal setting and feedback. Patients may play a larger role in reporting hospital satisfaction in real time, reconciling medications, contributing to the treatment plan, and identifying medical errors. As portals are integrated across the care continuum,20 our understanding of their impact may become more clear.

In this review, only 5 studies were conducted in the pediatric hospital setting.24,32-34,38 With hospitalized children experiencing 3 times more harm from medical errors than adults,44 engaging parents in inpatient care to improve safety has become a national priority.45 Giving patient portals, or “parent portals,” to parents of hospitalized children may provide a unique opportunity to share healthcare information and promote engagement, a direction for future study. There is also a research gap in evaluating adolescent inpatient portal use. Future portals may be designed to incentivize young children to learn about their hospitalization through games linked to health-related education.

Finally, as patients and caregivers begin using inpatient portals, there will almost certainly be consequences for healthcare teams. Understanding and anticipating human and work system factors influencing inpatient portal adoption and use from the perspectives of both patients and healthcare teams are needed.46,47 Engaging healthcare team members as valuable stakeholders during implementation and measuring the impact of portal use on their workload is necessary, especially as portal use spreads beyond pilot units. The success of inpatient portals is dependent upon both the positive benefits for patients and their acceptance by healthcare teams.48

Limitations exist in conducting a systematic literature review.49 The conceptual definition of a portal for hospitalized patients and patient/caregiver engagement is evolving; therefore, our definition may not have captured all relevant studies. We intentionally did not include all inpatient technology, as we were interested in a narrow definition of portals designed for inpatients that provided clinical information from the inpatient EHR. Because of rapid technology changes, we also limited our search to studies published within the last 10 years; prior literature has been described elsewhere.17 We excluded non-English language studies, limiting our ability to capture the full scope of inpatient portal research. These patients already experience healthcare delivery disparities, widened by the inaccessibility of innovative health information technologies.50 Future studies would be enhanced with the inclusion of these participants.

Inpatient portal research is in its infancy but growing rapidly. Studies to date are primarily focused on portal design and have small sample sizes. Early findings suggest that patients and caregivers are, in general, enthusiastic about using inpatient portals. Further research is needed, however, to determine the impact of inpatient portal use on patient engagement and hospital-care quality, safety, and cost.

Disclosure

This work was supported by a Department of Pediatrics Research and Development Grant at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health. This publication was also supported by the Clinical and Translational Science Award program through the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, grant UL1TR000427. Dr. Hoonakker’s involvement was also partially supported by the National Science Foundation, grant CMMI 1536987. Funding sources had no involvement in study design, analysis, or interpretation of data. The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

1. Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796-804. PubMed

2. Little P, Everitt H, Williamson I, et al. Observational study of effect of patient centredness and positive approach on outcomes of general practice consultations. BMJ. 2001;323(7318):908-911. PubMed

3. Maeng DD, Graf TR, Davis DE, Tomcavage J, Bloom FJ, Jr. Can a patient-centered medical home lead to better patient outcomes? The Quality Implications of Geisinger’s ProvenHealth Navigator. Am J Med Qual. 2012;27(3):210-216. PubMed