User login

Letter to the Editor

We acknowledge that our inability to measure in‐person interruptions is a limitation of our study. We maintain that while in‐person interruptions may increase in geographically localized patient care units, this form of direct face‐to‐face communication is more effective, efficient and decreases the latent errors inherent in alphanumeric paging.

Dr. Gandiga cites a study conducted in an emergency department where the vast majority of interruptions to attending physicians were in person from nurses or medical staff. We feel that this study cannot be extrapolated to medical floors, as the workflow and patient flow in an emergency department is very different than on a medical floor. The continuous throughput of patients in an emergency department would require ongoing and frequent communication between the different members of the care team. In addition, the physicians in that study were receiving an average of 1 page in 12 hours, compared to greater than 25 in 12 hours for our interns on a localized service, which illustrates the problem with comparing the emergency department to a localized medical floor.[1, 2]

We believe that the benefits of geographically localized care models, which include dramatic decreases in paging, improved efficiency, and greater agreement on the plan of care, outweigh the probable increases in in‐person interruptions. Additional study is indeed warranted to further clarify this discussion.

- , , . A study of emergency physician work and communication: a human factors approach. Isr J Em Med. 2005;5(3):35–42.

- , , . (Re)turning the pages of residency: the impact of localizing resident physicians to hospital units on paging frequency. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):120–122.

We acknowledge that our inability to measure in‐person interruptions is a limitation of our study. We maintain that while in‐person interruptions may increase in geographically localized patient care units, this form of direct face‐to‐face communication is more effective, efficient and decreases the latent errors inherent in alphanumeric paging.

Dr. Gandiga cites a study conducted in an emergency department where the vast majority of interruptions to attending physicians were in person from nurses or medical staff. We feel that this study cannot be extrapolated to medical floors, as the workflow and patient flow in an emergency department is very different than on a medical floor. The continuous throughput of patients in an emergency department would require ongoing and frequent communication between the different members of the care team. In addition, the physicians in that study were receiving an average of 1 page in 12 hours, compared to greater than 25 in 12 hours for our interns on a localized service, which illustrates the problem with comparing the emergency department to a localized medical floor.[1, 2]

We believe that the benefits of geographically localized care models, which include dramatic decreases in paging, improved efficiency, and greater agreement on the plan of care, outweigh the probable increases in in‐person interruptions. Additional study is indeed warranted to further clarify this discussion.

We acknowledge that our inability to measure in‐person interruptions is a limitation of our study. We maintain that while in‐person interruptions may increase in geographically localized patient care units, this form of direct face‐to‐face communication is more effective, efficient and decreases the latent errors inherent in alphanumeric paging.

Dr. Gandiga cites a study conducted in an emergency department where the vast majority of interruptions to attending physicians were in person from nurses or medical staff. We feel that this study cannot be extrapolated to medical floors, as the workflow and patient flow in an emergency department is very different than on a medical floor. The continuous throughput of patients in an emergency department would require ongoing and frequent communication between the different members of the care team. In addition, the physicians in that study were receiving an average of 1 page in 12 hours, compared to greater than 25 in 12 hours for our interns on a localized service, which illustrates the problem with comparing the emergency department to a localized medical floor.[1, 2]

We believe that the benefits of geographically localized care models, which include dramatic decreases in paging, improved efficiency, and greater agreement on the plan of care, outweigh the probable increases in in‐person interruptions. Additional study is indeed warranted to further clarify this discussion.

- , , . A study of emergency physician work and communication: a human factors approach. Isr J Em Med. 2005;5(3):35–42.

- , , . (Re)turning the pages of residency: the impact of localizing resident physicians to hospital units on paging frequency. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):120–122.

- , , . A study of emergency physician work and communication: a human factors approach. Isr J Em Med. 2005;5(3):35–42.

- , , . (Re)turning the pages of residency: the impact of localizing resident physicians to hospital units on paging frequency. J Hosp Med. 2014;9(2):120–122.

(Re)turning the Pages of Residency

It's hard to imagine a busy urban hospital without its chorus of beepers.[1] This statement, the first sentence of an article published in 1988, rings (or beeps or buzzes) true to any resident physician today. At that time, pagers had replaced overhead paging, and provided a rapid method to contact physicians who were often scattered throughout the hospital. Still, it was an imperfect solution as the ubiquitous pager constantly interrupted patient care and other tasks, failed to prioritize information, and added to an already stressful working environment. Notably, interns were paged on average once per hour, and occasionally 5 or more times per hour, a frequency that was felt to be detrimental to patient care and to the working environment of resident physicians.[1]

Little has changed. Despite the instant, multidirectional communication platforms available today, alphanumeric paging remains a mainstay of communication between physicians and other members of the care team. Importantly, paging contributes to communication errors (eg, by failing to convey urgency, having incomplete information, or being missed entirely by coverage gaps),[2, 3] and interrupts resident workflow, thereby negatively affecting work efficiency and educational activities, and adding to perceived workload.[4, 5]

In this era of duty hour restrictions, there has been concern that residents experience increased workload due to having fewer hours to do the same amount of work.[6, 7] As such, the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education emphasizes the quality of those hours, with a focus on several aspects of the resident working environment as key to improved educational and patient safety outcomes.[8, 9, 10]

Geographic localization of physicians to patient care units has been proposed as a means to improve communication and agreement on plans of care,[11, 12] and also to reduce resident workload by decreasing inefficiencies attributable to traveling throughout the hospital.[13] O'Leary, et al. (2009) found that when physicians were localized to 1 hospital unit, there was greater agreement between physicians and nurses on various aspects of care, such as planned tests and anticipated length of stay. In addition, members of the patient care team were better able to identify one another, and there was a perceived increase in face‐to‐face communication, and a perceived decrease in text paging.[11]

In consideration of these factors, in July 2011, at New YorkPresbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell (NYPH/WC), an 800‐bed tertiary care teaching hospital in New York, New York, we geographically localized 2 internal medicine resident teams, and partially localized 2 additional teams. We investigated whether interns on teams that were geographically localized received fewer pages than interns on teams that were not localized. This study was reviewed by the institutional review board of Weill Cornell Medical College and met the requirements for exemption.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective analysis of the number of pages received by interns during the day (7:00 am to 7:00 pm) on 5 general internal medicine teams during a 1‐month ward rotation between October 17, 2011 and November 13, 2011 at NYPH/WC. The general medicine teams were composed of 1 attending, 1 resident, and 2 interns each. Two teams were geographically localized to a 32‐bed unit (geographic localization model [GLM]). Two teams were partially localized to a 26‐bed unit, which included a respiratory care step‐down unit (partial localization model [PLM]). A fifth and final team admitted patients irrespective of their assigned bed location (standard model [SM]). Both the GLM and the PLM occasionally carried patients on other units to allow for overall census management and patient throughput. The total number of pages received by each intern over the study period was collected by retrospective analysis of electronic paging logs. Night pages (7 pm7 am) were excluded because of night float coverage. Weekend pages were excluded because data were inaccurate due to coverage for days off.

The daily number of admissions and daily census per team were recorded by physician assistants, who also assigned new patients to appropriate teams according to an admissions algorithm (see Supporting Figure 1 in the online version of this article). The percent of geographically localized patients on each team was estimated from the percentage of localized patients on the day of discharge averaged over the study period. For the SM team, percent localization was defined as the number of patients on the patient care unit that contained the team's work area.

Standard multivariate linear regression techniques were used to analyze the relationship between the number of pages received per intern and the type of team, controlling for the potential effect of total census and number of admissions. The regression model was used to determine adjusted marginal point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the average number of pages per intern per hour for each type of team. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Over the 28‐day study period, a total of 6652 pages were received by 10 interns on 5 general internal medicine teams from 7 am to 7 pm Monday through Friday. The average daily census, average daily admissions, and percent of patients localized to patient care units for the individual teams are shown in Table 1. In univariate analysis, the mean daily pages per intern were not significantly different between the 2 teams within the GLM, nor between the 2 teams in the PLM, allowing them to be combined in multivariate analysis (data not shown). The number of pages received per intern per hour, adjusted for team census and number of admissions, was 2.2 (95% CI: 2.02.4) in the GLM, 2.8 (95% CI: 2.6‐3.0) in the PLM, and 3.9 (95% CI: 3.6‐4.2) in the SM (Table 1). All of these differences were statistically significant (P0.001).

| Standard Model* | Partial Localization Model | Geographically Localized Model | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Percent of patients localized | 37% | 45% | 85% |

| Team census, mean (range per day) | 16.1 (1320) | 15.9 (1120) | 15.6 (1119) |

| Team admissions, mean (range per day) | 2.7 (15) | 2.9 (06) | 3.5 (07) |

| Pages per hour per intern, unadjusted, mean (95% CI) | 3.9 (3.6‐4.1) | 2.8 (2.6‐3.0) | 2.2 (2.02.4) |

| Pages per hour per intern, adjusted for census and admissions, mean (95% CI) | 3.9 (3.6‐4.2) | 2.8 (2.6‐3.0) | 2.2 (2.02.4) |

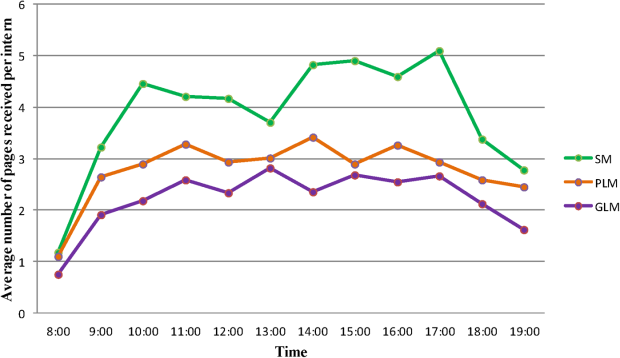

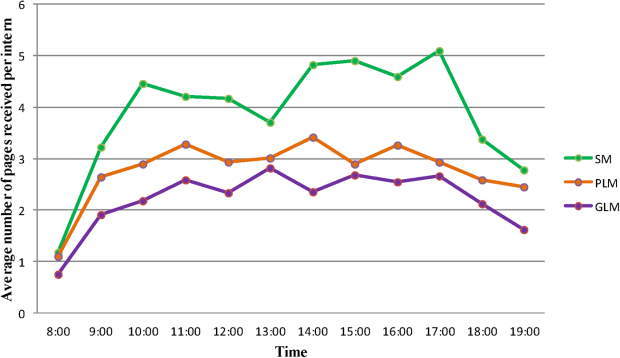

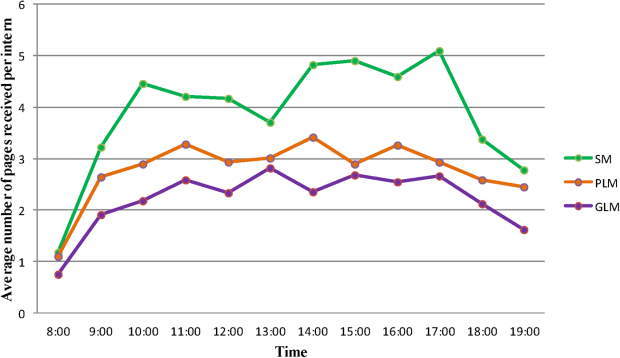

Figure 1 shows the pattern of daytime paging for each model. The GLM and PLM had a similar pattern, with an initial ramp up in the first 2 hours of the day, holding steady until approximately 4 pm, and then decrease until 7 pm. The SM had a steeper initial rise, and then continued to increase slowly until a peak at 4 pm.

DISCUSSION

This study corroborates that of Singh et al. (2012), who found that geographic localization led to significantly fewer pages.[14] Our results strengthen the evidence by demonstrating that even modest differences between the percent of patients localized to a care unit led to a significant decrease in the number of pages, indicating a dose‐response effect. The paging frequency we measured is higher than described in Singh et al. (1.4 pages per hour for localized teams), yet our average census appears to be 4 patients higher, which may account for some of that difference. We also show that interns on teams whose patients are more widely scattered throughout the hospital may experience upward of 5 pages per hour, an interruption by pager every 12 minutes, all day long.

A pager interruption is not solely limited to a disruption by noxious sound or vibration. The page recipient must then read the page and respond accordingly, which may involve a phone call, placing an order, walking to another location, or other work tasks. Although some of these interruptions must be handled immediately, such as a clinically deteriorating patient, many are not urgent, and could wait until the physician's current task or thought process is complete. There is also the potentially risky assumption on the part of the sender that the message has been received and will be acted upon. Furthermore, frequent paging is a common interruption to physician workflow; interruptions contribute to increased perceived physician workload[4, 5] and are likely detrimental to patient safety.[15, 16]

The most common metrics used to measure resident workload are patient census and number of admissions,[13] but these metrics have provided a mixed and likely incomplete picture. Recent research suggests that other factors, such as work efficiency (including interruptions, time spent obtaining test results, and time in transit) and work intensity (such as the acuity and complexity of patients), contribute significantly to actual and perceived resident workload.[13]

Our analysis was a single‐site, retrospective study, which occurred over 1 month and was limited to internal medicine teams. Additionally, geographic localization logically should lead to increased face‐to‐face interruptions, which we were unable to measure with this project, but direct communication is more efficient and less prone to error, which would likely lead to fewer overall interruptions. Although we anticipate that our findings are applicable to geographically localized patient care units in other hospitals, further investigation is warranted.

The paging chorus has only grown louder over the last 25 years, with likely downstream effects on patient safety and resident education. To mitigate these effects, it is incumbent upon us to approach our training and patient care environments with a critical and creative lens, and to explore opportunities to decrease interruptions and streamline our communication systems.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the assistance with data analysis of Arthur Evans, MD, MPH, and review of the manuscript by Brendan Reilly, MD.

Disclosures: Dr. Fanucchi and Ms. Unterbrink have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Logio reports receiving royalties from McGraw‐Hill for Core Concepts in Patient Safety online modules.

- , . The sounds of the hospital. Paging patterns in three teaching hospitals. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(24):1585–1589.

- , , . Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):186–194.

- , , . Alphanumeric paging: a potential source of problems in patient care and communication. J Surg Educ. 2011;68(6):447–451.

- , , , , . Hospital doctors' workflow interruptions and activities: an observation study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(6):491–497.

- , , , , . The association of workflow interruptions and hospital doctors' workload: a prospective observational study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(5):399–407.

- , . Resident workload—let's treat the disease, not just the symptom. Comment on: Effect of the 2011 vs 2003 duty hour regulation‐compliant models on sleep duration, trainee education, and continuity of patient care among internal medicine house staff. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):655–656.

- , , , et al. Effect of the 2011 vs 2003 duty hour regulation‐compliant models on sleep duration, trainee education, and continuity of patient care among internal medicine house staff: a randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):649–655.

- , . The ACGME 2011 Duty Hour Standards: Enhancing Quality of Care, Supervision, and Resident Professional Development. Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2011.

- , , , . Institute of Medicine Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009.

- , , , , , . Perspective: beyond counting hours: the importance of supervision, professionalism, transitions of care, and workload in residency training. Acad Med. 2012;87(7):883–888.

- , , , et al. Impact of localizing physicians to hospital units on nurse‐physician communication and agreement on the plan of care. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(11):1223–1227.

- , , , et al. Unit‐based care teams and the frequency and quality of physician‐nurse communications. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(5):424–428.

- , , , et al. Service census caps and unit‐based admissions: resident workload, conference attendance, duty hour compliance, and patient safety. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(4):320–327.

- , , , et al. Impact of localizing general medical teams to a single nursing unit. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(7):551–556.

- . The science of interruption. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(5):357–360.

- , , , et al. The impact of interruptions on clinical task completion. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(4):284–289.

It's hard to imagine a busy urban hospital without its chorus of beepers.[1] This statement, the first sentence of an article published in 1988, rings (or beeps or buzzes) true to any resident physician today. At that time, pagers had replaced overhead paging, and provided a rapid method to contact physicians who were often scattered throughout the hospital. Still, it was an imperfect solution as the ubiquitous pager constantly interrupted patient care and other tasks, failed to prioritize information, and added to an already stressful working environment. Notably, interns were paged on average once per hour, and occasionally 5 or more times per hour, a frequency that was felt to be detrimental to patient care and to the working environment of resident physicians.[1]

Little has changed. Despite the instant, multidirectional communication platforms available today, alphanumeric paging remains a mainstay of communication between physicians and other members of the care team. Importantly, paging contributes to communication errors (eg, by failing to convey urgency, having incomplete information, or being missed entirely by coverage gaps),[2, 3] and interrupts resident workflow, thereby negatively affecting work efficiency and educational activities, and adding to perceived workload.[4, 5]

In this era of duty hour restrictions, there has been concern that residents experience increased workload due to having fewer hours to do the same amount of work.[6, 7] As such, the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education emphasizes the quality of those hours, with a focus on several aspects of the resident working environment as key to improved educational and patient safety outcomes.[8, 9, 10]

Geographic localization of physicians to patient care units has been proposed as a means to improve communication and agreement on plans of care,[11, 12] and also to reduce resident workload by decreasing inefficiencies attributable to traveling throughout the hospital.[13] O'Leary, et al. (2009) found that when physicians were localized to 1 hospital unit, there was greater agreement between physicians and nurses on various aspects of care, such as planned tests and anticipated length of stay. In addition, members of the patient care team were better able to identify one another, and there was a perceived increase in face‐to‐face communication, and a perceived decrease in text paging.[11]

In consideration of these factors, in July 2011, at New YorkPresbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell (NYPH/WC), an 800‐bed tertiary care teaching hospital in New York, New York, we geographically localized 2 internal medicine resident teams, and partially localized 2 additional teams. We investigated whether interns on teams that were geographically localized received fewer pages than interns on teams that were not localized. This study was reviewed by the institutional review board of Weill Cornell Medical College and met the requirements for exemption.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective analysis of the number of pages received by interns during the day (7:00 am to 7:00 pm) on 5 general internal medicine teams during a 1‐month ward rotation between October 17, 2011 and November 13, 2011 at NYPH/WC. The general medicine teams were composed of 1 attending, 1 resident, and 2 interns each. Two teams were geographically localized to a 32‐bed unit (geographic localization model [GLM]). Two teams were partially localized to a 26‐bed unit, which included a respiratory care step‐down unit (partial localization model [PLM]). A fifth and final team admitted patients irrespective of their assigned bed location (standard model [SM]). Both the GLM and the PLM occasionally carried patients on other units to allow for overall census management and patient throughput. The total number of pages received by each intern over the study period was collected by retrospective analysis of electronic paging logs. Night pages (7 pm7 am) were excluded because of night float coverage. Weekend pages were excluded because data were inaccurate due to coverage for days off.

The daily number of admissions and daily census per team were recorded by physician assistants, who also assigned new patients to appropriate teams according to an admissions algorithm (see Supporting Figure 1 in the online version of this article). The percent of geographically localized patients on each team was estimated from the percentage of localized patients on the day of discharge averaged over the study period. For the SM team, percent localization was defined as the number of patients on the patient care unit that contained the team's work area.

Standard multivariate linear regression techniques were used to analyze the relationship between the number of pages received per intern and the type of team, controlling for the potential effect of total census and number of admissions. The regression model was used to determine adjusted marginal point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the average number of pages per intern per hour for each type of team. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Over the 28‐day study period, a total of 6652 pages were received by 10 interns on 5 general internal medicine teams from 7 am to 7 pm Monday through Friday. The average daily census, average daily admissions, and percent of patients localized to patient care units for the individual teams are shown in Table 1. In univariate analysis, the mean daily pages per intern were not significantly different between the 2 teams within the GLM, nor between the 2 teams in the PLM, allowing them to be combined in multivariate analysis (data not shown). The number of pages received per intern per hour, adjusted for team census and number of admissions, was 2.2 (95% CI: 2.02.4) in the GLM, 2.8 (95% CI: 2.6‐3.0) in the PLM, and 3.9 (95% CI: 3.6‐4.2) in the SM (Table 1). All of these differences were statistically significant (P0.001).

| Standard Model* | Partial Localization Model | Geographically Localized Model | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Percent of patients localized | 37% | 45% | 85% |

| Team census, mean (range per day) | 16.1 (1320) | 15.9 (1120) | 15.6 (1119) |

| Team admissions, mean (range per day) | 2.7 (15) | 2.9 (06) | 3.5 (07) |

| Pages per hour per intern, unadjusted, mean (95% CI) | 3.9 (3.6‐4.1) | 2.8 (2.6‐3.0) | 2.2 (2.02.4) |

| Pages per hour per intern, adjusted for census and admissions, mean (95% CI) | 3.9 (3.6‐4.2) | 2.8 (2.6‐3.0) | 2.2 (2.02.4) |

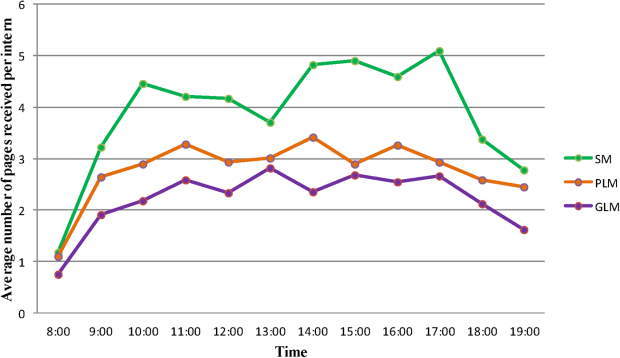

Figure 1 shows the pattern of daytime paging for each model. The GLM and PLM had a similar pattern, with an initial ramp up in the first 2 hours of the day, holding steady until approximately 4 pm, and then decrease until 7 pm. The SM had a steeper initial rise, and then continued to increase slowly until a peak at 4 pm.

DISCUSSION

This study corroborates that of Singh et al. (2012), who found that geographic localization led to significantly fewer pages.[14] Our results strengthen the evidence by demonstrating that even modest differences between the percent of patients localized to a care unit led to a significant decrease in the number of pages, indicating a dose‐response effect. The paging frequency we measured is higher than described in Singh et al. (1.4 pages per hour for localized teams), yet our average census appears to be 4 patients higher, which may account for some of that difference. We also show that interns on teams whose patients are more widely scattered throughout the hospital may experience upward of 5 pages per hour, an interruption by pager every 12 minutes, all day long.

A pager interruption is not solely limited to a disruption by noxious sound or vibration. The page recipient must then read the page and respond accordingly, which may involve a phone call, placing an order, walking to another location, or other work tasks. Although some of these interruptions must be handled immediately, such as a clinically deteriorating patient, many are not urgent, and could wait until the physician's current task or thought process is complete. There is also the potentially risky assumption on the part of the sender that the message has been received and will be acted upon. Furthermore, frequent paging is a common interruption to physician workflow; interruptions contribute to increased perceived physician workload[4, 5] and are likely detrimental to patient safety.[15, 16]

The most common metrics used to measure resident workload are patient census and number of admissions,[13] but these metrics have provided a mixed and likely incomplete picture. Recent research suggests that other factors, such as work efficiency (including interruptions, time spent obtaining test results, and time in transit) and work intensity (such as the acuity and complexity of patients), contribute significantly to actual and perceived resident workload.[13]

Our analysis was a single‐site, retrospective study, which occurred over 1 month and was limited to internal medicine teams. Additionally, geographic localization logically should lead to increased face‐to‐face interruptions, which we were unable to measure with this project, but direct communication is more efficient and less prone to error, which would likely lead to fewer overall interruptions. Although we anticipate that our findings are applicable to geographically localized patient care units in other hospitals, further investigation is warranted.

The paging chorus has only grown louder over the last 25 years, with likely downstream effects on patient safety and resident education. To mitigate these effects, it is incumbent upon us to approach our training and patient care environments with a critical and creative lens, and to explore opportunities to decrease interruptions and streamline our communication systems.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the assistance with data analysis of Arthur Evans, MD, MPH, and review of the manuscript by Brendan Reilly, MD.

Disclosures: Dr. Fanucchi and Ms. Unterbrink have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Logio reports receiving royalties from McGraw‐Hill for Core Concepts in Patient Safety online modules.

It's hard to imagine a busy urban hospital without its chorus of beepers.[1] This statement, the first sentence of an article published in 1988, rings (or beeps or buzzes) true to any resident physician today. At that time, pagers had replaced overhead paging, and provided a rapid method to contact physicians who were often scattered throughout the hospital. Still, it was an imperfect solution as the ubiquitous pager constantly interrupted patient care and other tasks, failed to prioritize information, and added to an already stressful working environment. Notably, interns were paged on average once per hour, and occasionally 5 or more times per hour, a frequency that was felt to be detrimental to patient care and to the working environment of resident physicians.[1]

Little has changed. Despite the instant, multidirectional communication platforms available today, alphanumeric paging remains a mainstay of communication between physicians and other members of the care team. Importantly, paging contributes to communication errors (eg, by failing to convey urgency, having incomplete information, or being missed entirely by coverage gaps),[2, 3] and interrupts resident workflow, thereby negatively affecting work efficiency and educational activities, and adding to perceived workload.[4, 5]

In this era of duty hour restrictions, there has been concern that residents experience increased workload due to having fewer hours to do the same amount of work.[6, 7] As such, the Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education emphasizes the quality of those hours, with a focus on several aspects of the resident working environment as key to improved educational and patient safety outcomes.[8, 9, 10]

Geographic localization of physicians to patient care units has been proposed as a means to improve communication and agreement on plans of care,[11, 12] and also to reduce resident workload by decreasing inefficiencies attributable to traveling throughout the hospital.[13] O'Leary, et al. (2009) found that when physicians were localized to 1 hospital unit, there was greater agreement between physicians and nurses on various aspects of care, such as planned tests and anticipated length of stay. In addition, members of the patient care team were better able to identify one another, and there was a perceived increase in face‐to‐face communication, and a perceived decrease in text paging.[11]

In consideration of these factors, in July 2011, at New YorkPresbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell (NYPH/WC), an 800‐bed tertiary care teaching hospital in New York, New York, we geographically localized 2 internal medicine resident teams, and partially localized 2 additional teams. We investigated whether interns on teams that were geographically localized received fewer pages than interns on teams that were not localized. This study was reviewed by the institutional review board of Weill Cornell Medical College and met the requirements for exemption.

METHODS

We conducted a retrospective analysis of the number of pages received by interns during the day (7:00 am to 7:00 pm) on 5 general internal medicine teams during a 1‐month ward rotation between October 17, 2011 and November 13, 2011 at NYPH/WC. The general medicine teams were composed of 1 attending, 1 resident, and 2 interns each. Two teams were geographically localized to a 32‐bed unit (geographic localization model [GLM]). Two teams were partially localized to a 26‐bed unit, which included a respiratory care step‐down unit (partial localization model [PLM]). A fifth and final team admitted patients irrespective of their assigned bed location (standard model [SM]). Both the GLM and the PLM occasionally carried patients on other units to allow for overall census management and patient throughput. The total number of pages received by each intern over the study period was collected by retrospective analysis of electronic paging logs. Night pages (7 pm7 am) were excluded because of night float coverage. Weekend pages were excluded because data were inaccurate due to coverage for days off.

The daily number of admissions and daily census per team were recorded by physician assistants, who also assigned new patients to appropriate teams according to an admissions algorithm (see Supporting Figure 1 in the online version of this article). The percent of geographically localized patients on each team was estimated from the percentage of localized patients on the day of discharge averaged over the study period. For the SM team, percent localization was defined as the number of patients on the patient care unit that contained the team's work area.

Standard multivariate linear regression techniques were used to analyze the relationship between the number of pages received per intern and the type of team, controlling for the potential effect of total census and number of admissions. The regression model was used to determine adjusted marginal point estimates and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for the average number of pages per intern per hour for each type of team. All statistical analyses were conducted using Stata version 12 (StataCorp, College Station, TX).

RESULTS

Over the 28‐day study period, a total of 6652 pages were received by 10 interns on 5 general internal medicine teams from 7 am to 7 pm Monday through Friday. The average daily census, average daily admissions, and percent of patients localized to patient care units for the individual teams are shown in Table 1. In univariate analysis, the mean daily pages per intern were not significantly different between the 2 teams within the GLM, nor between the 2 teams in the PLM, allowing them to be combined in multivariate analysis (data not shown). The number of pages received per intern per hour, adjusted for team census and number of admissions, was 2.2 (95% CI: 2.02.4) in the GLM, 2.8 (95% CI: 2.6‐3.0) in the PLM, and 3.9 (95% CI: 3.6‐4.2) in the SM (Table 1). All of these differences were statistically significant (P0.001).

| Standard Model* | Partial Localization Model | Geographically Localized Model | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Percent of patients localized | 37% | 45% | 85% |

| Team census, mean (range per day) | 16.1 (1320) | 15.9 (1120) | 15.6 (1119) |

| Team admissions, mean (range per day) | 2.7 (15) | 2.9 (06) | 3.5 (07) |

| Pages per hour per intern, unadjusted, mean (95% CI) | 3.9 (3.6‐4.1) | 2.8 (2.6‐3.0) | 2.2 (2.02.4) |

| Pages per hour per intern, adjusted for census and admissions, mean (95% CI) | 3.9 (3.6‐4.2) | 2.8 (2.6‐3.0) | 2.2 (2.02.4) |

Figure 1 shows the pattern of daytime paging for each model. The GLM and PLM had a similar pattern, with an initial ramp up in the first 2 hours of the day, holding steady until approximately 4 pm, and then decrease until 7 pm. The SM had a steeper initial rise, and then continued to increase slowly until a peak at 4 pm.

DISCUSSION

This study corroborates that of Singh et al. (2012), who found that geographic localization led to significantly fewer pages.[14] Our results strengthen the evidence by demonstrating that even modest differences between the percent of patients localized to a care unit led to a significant decrease in the number of pages, indicating a dose‐response effect. The paging frequency we measured is higher than described in Singh et al. (1.4 pages per hour for localized teams), yet our average census appears to be 4 patients higher, which may account for some of that difference. We also show that interns on teams whose patients are more widely scattered throughout the hospital may experience upward of 5 pages per hour, an interruption by pager every 12 minutes, all day long.

A pager interruption is not solely limited to a disruption by noxious sound or vibration. The page recipient must then read the page and respond accordingly, which may involve a phone call, placing an order, walking to another location, or other work tasks. Although some of these interruptions must be handled immediately, such as a clinically deteriorating patient, many are not urgent, and could wait until the physician's current task or thought process is complete. There is also the potentially risky assumption on the part of the sender that the message has been received and will be acted upon. Furthermore, frequent paging is a common interruption to physician workflow; interruptions contribute to increased perceived physician workload[4, 5] and are likely detrimental to patient safety.[15, 16]

The most common metrics used to measure resident workload are patient census and number of admissions,[13] but these metrics have provided a mixed and likely incomplete picture. Recent research suggests that other factors, such as work efficiency (including interruptions, time spent obtaining test results, and time in transit) and work intensity (such as the acuity and complexity of patients), contribute significantly to actual and perceived resident workload.[13]

Our analysis was a single‐site, retrospective study, which occurred over 1 month and was limited to internal medicine teams. Additionally, geographic localization logically should lead to increased face‐to‐face interruptions, which we were unable to measure with this project, but direct communication is more efficient and less prone to error, which would likely lead to fewer overall interruptions. Although we anticipate that our findings are applicable to geographically localized patient care units in other hospitals, further investigation is warranted.

The paging chorus has only grown louder over the last 25 years, with likely downstream effects on patient safety and resident education. To mitigate these effects, it is incumbent upon us to approach our training and patient care environments with a critical and creative lens, and to explore opportunities to decrease interruptions and streamline our communication systems.

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the assistance with data analysis of Arthur Evans, MD, MPH, and review of the manuscript by Brendan Reilly, MD.

Disclosures: Dr. Fanucchi and Ms. Unterbrink have no conflicts of interest to disclose. Dr. Logio reports receiving royalties from McGraw‐Hill for Core Concepts in Patient Safety online modules.

- , . The sounds of the hospital. Paging patterns in three teaching hospitals. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(24):1585–1589.

- , , . Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):186–194.

- , , . Alphanumeric paging: a potential source of problems in patient care and communication. J Surg Educ. 2011;68(6):447–451.

- , , , , . Hospital doctors' workflow interruptions and activities: an observation study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(6):491–497.

- , , , , . The association of workflow interruptions and hospital doctors' workload: a prospective observational study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(5):399–407.

- , . Resident workload—let's treat the disease, not just the symptom. Comment on: Effect of the 2011 vs 2003 duty hour regulation‐compliant models on sleep duration, trainee education, and continuity of patient care among internal medicine house staff. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):655–656.

- , , , et al. Effect of the 2011 vs 2003 duty hour regulation‐compliant models on sleep duration, trainee education, and continuity of patient care among internal medicine house staff: a randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):649–655.

- , . The ACGME 2011 Duty Hour Standards: Enhancing Quality of Care, Supervision, and Resident Professional Development. Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2011.

- , , , . Institute of Medicine Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009.

- , , , , , . Perspective: beyond counting hours: the importance of supervision, professionalism, transitions of care, and workload in residency training. Acad Med. 2012;87(7):883–888.

- , , , et al. Impact of localizing physicians to hospital units on nurse‐physician communication and agreement on the plan of care. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(11):1223–1227.

- , , , et al. Unit‐based care teams and the frequency and quality of physician‐nurse communications. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(5):424–428.

- , , , et al. Service census caps and unit‐based admissions: resident workload, conference attendance, duty hour compliance, and patient safety. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(4):320–327.

- , , , et al. Impact of localizing general medical teams to a single nursing unit. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(7):551–556.

- . The science of interruption. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(5):357–360.

- , , , et al. The impact of interruptions on clinical task completion. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(4):284–289.

- , . The sounds of the hospital. Paging patterns in three teaching hospitals. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(24):1585–1589.

- , , . Communication failures: an insidious contributor to medical mishaps. Acad Med. 2004;79(2):186–194.

- , , . Alphanumeric paging: a potential source of problems in patient care and communication. J Surg Educ. 2011;68(6):447–451.

- , , , , . Hospital doctors' workflow interruptions and activities: an observation study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(6):491–497.

- , , , , . The association of workflow interruptions and hospital doctors' workload: a prospective observational study. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(5):399–407.

- , . Resident workload—let's treat the disease, not just the symptom. Comment on: Effect of the 2011 vs 2003 duty hour regulation‐compliant models on sleep duration, trainee education, and continuity of patient care among internal medicine house staff. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):655–656.

- , , , et al. Effect of the 2011 vs 2003 duty hour regulation‐compliant models on sleep duration, trainee education, and continuity of patient care among internal medicine house staff: a randomized trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(8):649–655.

- , . The ACGME 2011 Duty Hour Standards: Enhancing Quality of Care, Supervision, and Resident Professional Development. Chicago, IL: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2011.

- , , , . Institute of Medicine Resident Duty Hours: Enhancing Sleep, Supervision, and Safety. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2009.

- , , , , , . Perspective: beyond counting hours: the importance of supervision, professionalism, transitions of care, and workload in residency training. Acad Med. 2012;87(7):883–888.

- , , , et al. Impact of localizing physicians to hospital units on nurse‐physician communication and agreement on the plan of care. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(11):1223–1227.

- , , , et al. Unit‐based care teams and the frequency and quality of physician‐nurse communications. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2011;165(5):424–428.

- , , , et al. Service census caps and unit‐based admissions: resident workload, conference attendance, duty hour compliance, and patient safety. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(4):320–327.

- , , , et al. Impact of localizing general medical teams to a single nursing unit. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(7):551–556.

- . The science of interruption. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(5):357–360.

- , , , et al. The impact of interruptions on clinical task completion. Qual Saf Health Care. 2010;19(4):284–289.

Patient Care Circle and Care Transitions

The focus on care transitions and readmissions is expanding beyond the development of risk scores based on objective clinical data to quality improvement interventions involving the key stakeholders in the process, namely the patients and their multidisciplinary providers.[1, 2] The Institute for Healthcare Improvement's State Action on Avoidable Rehospitalizations initiative promotes formulating a specific transition plan and developing multidisciplinary management strategies for all patients.[3] The Transition of Care Consensus Policy Statement developed by a coalition including the American College of Physicians and Society of Hospital Medicine emphasizes accountability, communication, and involvement of the patient and family members in plans of care.[4] Yet, interventions to reduce readmissions and improve the quality and safety of care transitions remain only modestly and inconsistently effective.

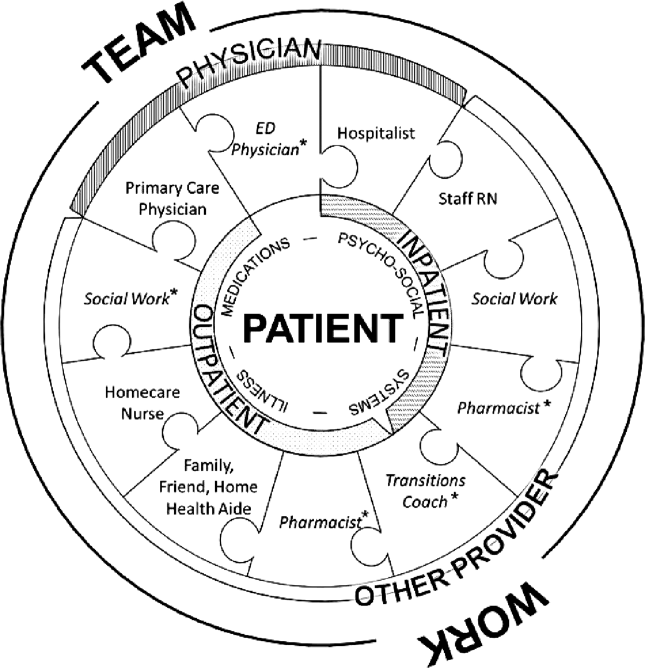

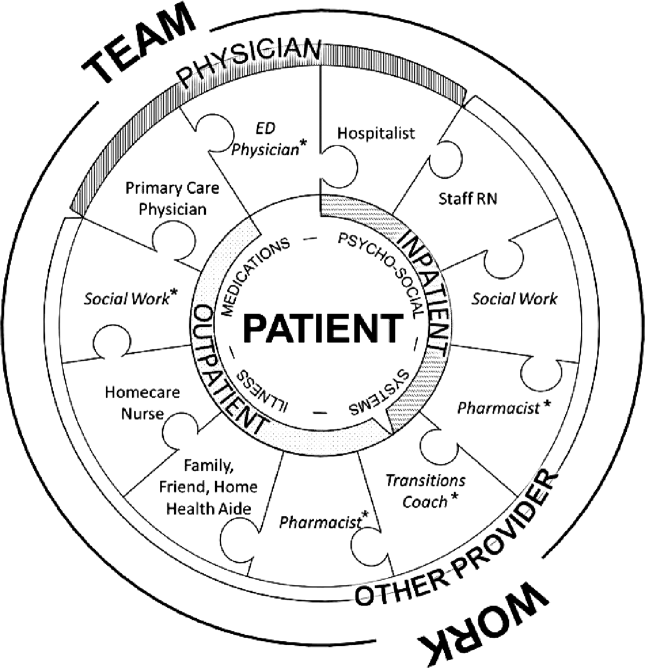

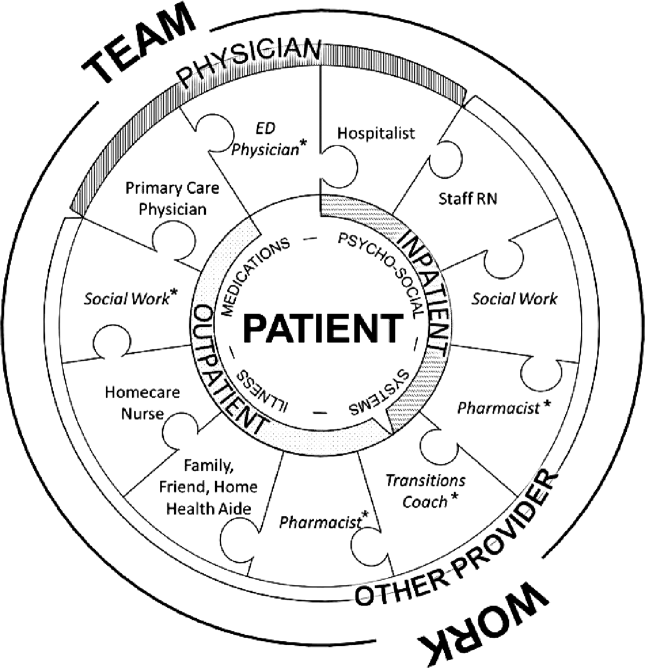

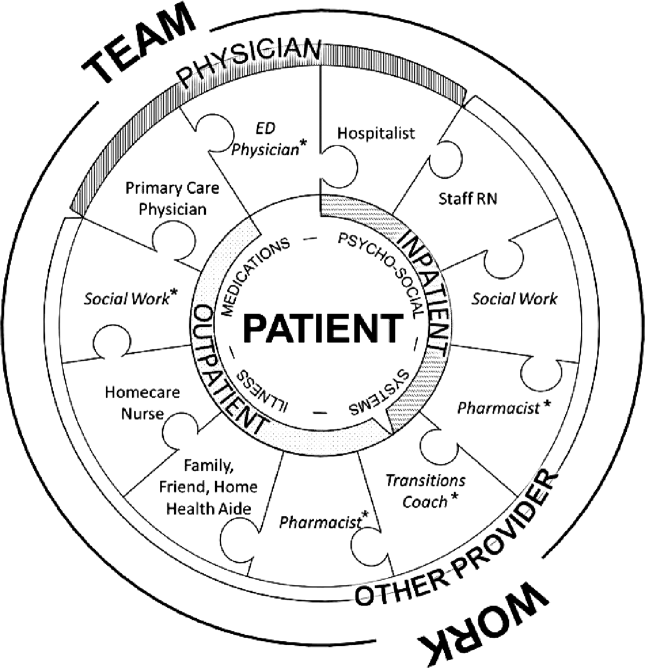

Successful interventions are those that are combined and coordinated, and shared across the hospital and community settings.[5] In this study, we sought to understand the issues leading to readmissions and barriers as perceived by patients, family members, physicians, nurses, and social workers. We compared and contrasted the perspectives by discipline and used this information to design a descriptive framework of a multidisciplinary, collaborative, and coordinated support network integral to effective care transitions, which we term a Patient Care Circle (PCC) (Figure 1).

METHODS

Study Design

We recruited a purposive sample of general medicine patients with same‐site 30‐day readmissions, and those directly involved in their care, to participate in interviews and focus groups to investigate explanations for unplanned readmissions (Table 1). We sought subjects' perspectives based on extrapolations from previous research that identified multiple stakeholders involved in the care transitions process,[1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8] and our own professional experience with patient readmissions.

| Role | No. (%) | No. Interviewed | No. in Focus Group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Patient | 12 | NA | ||

| Male | 10 (90.9) | |||

| Average age, y, range | 3172 | |||

| Insurance | ||||

| Medicare | 5 (41.7) | |||

| Medicaid | 1 (8.3) | |||

| Medicare/Medicaid | 2 (16.7) | |||

| Private | 4 (33.3) | |||

| Race | ||||

| White | 8 (66.7) | |||

| Black | 2 (16.7) | |||

| Other | 2 (16.7) | |||

| Has PMD | 9 (75.0) | |||

| Has home caregiver (family or aide) | 10 (90.9) | |||

| Physician | ||||

| Hospitalista | 9b | |||

| Index | 10 | |||

| Readmit | 9 | |||

| Primary care physician | 5 | NA | ||

| Other provider | ||||

| RN | ||||

| Inpatient staff | 5 | 7 | ||

| Visiting home | NA | 6 | ||

| Social work | NA | 6 | ||

| Other caregivers | ||||

| Family | 2 | NA | ||

| Home aides | 0 | NA | ||

| Total | 43 | 28 | ||

Site Selection

All interviews and focus groups were conducted at New YorkPresbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center (NYP/WC), a large urban academic medical center in New York City serving a racially and socioeconomically diverse population. The institutional review boards at Weill Cornell Medical College and Hunter College approved this study.

Data Collection Tools

We developed semistructured interview and focus group guides (see Supporting Information, Appendixes 17, in the online version of this article) by reviewing published literature[8, 9, 10, 11, 12] and readmission pilot data that identified challenges associated with hospital discharges. Interviews were patient specific, and providers involved directly in their care were asked to consider reasons for the patients' readmissions and whether they could have been prevented. Provider interview guides were modified from the patient interview script and tailored toward their role in the patient's care.

One focus group guide was used for all sessions, allowing us to compare and contrast emerging themes across disciplines. Participants were asked to discuss perceived causes for readmissions and barriers to improvement.

All questions were open‐ended to gain insight into participants' beliefs regarding the causes of readmissions and to limit researcher bias. We iteratively reviewed and modified the guides to ensure the questions were effectively worded.

Recruiting

Using a centralized clinical database, we identified patients aged 18 years and older for interviews, who were readmitted within 30 days to NYP/WC between May 2011 and May 2012, and had an attending hospitalist during the initial and readmission visits. We confirmed patients' English fluency and cognitive ability by contacting their attending physician. Patients provided written consent prior to interview.

For interviews, we asked patients to identify their outpatient physicians and providers; inpatient hospitalists and providers were identified from the patients' charts. For focus groups, we recruited volunteers among all division hospitalists and solicited volunteer inpatient nursing, social work, and homecare nursing participants through organizational liaisons (Table 1).

Data Collection

We interviewed patients in person at their bedside. We interviewed physicians and other caregivers in person or by telephone during the course of the patient's readmission. We conducted 4 discipline‐specific 90‐minute focus groups for hospitalists, inpatient staff nurses, homecare nurses, and hospital social workers. Patient interviews and focus groups were audio‐recorded and transcribed using a professional service.

Data Analysis

We analyzed 47 transcripts (43 interviews, 4 focus groups) during research group meetings using grounded theory[13] to generate overarching themes felt to influence readmissions through iterative reviewing of transcripts. We attributed codes to salient text and documented recurring topics that emerged. Two researchers independently assessed responses from the patient‐specific interviews for variability among the various disciplines. We ended our data collection after we ceased to find new topics from participants (thematic saturation).[14]

Three researchers, in consultation with the larger team, coded the 4 focus group transcripts to generate a codebook with definitions and examples of recurring concepts. They then coded the 43 interview transcripts using the codebook. The entire team met regularly to address questions and potential discrepancies.

We achieved greater trustworthiness of the analysis by using multiple modes of triangulation, a qualitative method that relies on points of comparison and contrast.[15] We achieved methodological triangulation by using both interviews and focus groups, and achieved internal triangulation by having researchers in the clinical, social, and behavioral sciences routinely critique the evolving codebook.

RESULTS

We recruited 43 interview and 28 focus group participants (Table 1). From our transcript analysis, we generated 22 codes and categorized them into 5 themes embodying the issues pertinent to readmissions from the perspective of the stakeholders: (1) teamwork, (2) health systems navigation and management, (3) illness severity and health needs, (4) psychosocial stability; and (5) medications (Table 2).

We applied these codes and themes to build a descriptive framework depicting what we believed is the essential foundation for successful care transitions, a collaborative unified patient‐centered network to address complex healthcare‐related issues across disciplines and across settings (Figure 1). Our model illustrates the interplay between the various physician and care‐provider roles as well as the relationship of the structure of the care circle to each theme.

Care Circle Theme

Teamwork

Comprehensive, effective collaboration and communication among members of the PCC were required for the circle to function successfully and establish safe ongoing patient care across settings. Teamwork required a shared purpose and aligned incentives among all stakeholders to work as a unified patient‐centered network.

Dysfunctional teamwork led to fragmented care. Hospitalists and patients cited difficulties coordinating in‐hospital management plans with multiple consulting subspecialists. Social workers ascribed 1 potential cause for unplanned readmissions to insufficient feedback from homecare agencies regarding patients following hospital discharge:

I wouldn't mind hearing [from the home agencies][the patient] won't let me in the door' patient's doing well' or patient's still not compliant.' If we don't knowthen we can't address it [until] they come back in [to the hospital].

Meanwhile, accurate handoff of information affected the care provided by homecare nurses:

We go into assess [the patient at home] and we see something totally different than what wason a piece of paper.

Patient‐Centered Themes

Four patient‐centered themes were identified that posed challenges in the transitions process and required the support and teamwork of the PCC to deal with effectually.

Health Systems Navigation and Management

The complexities of the healthcare system in the hospital and in the community presented challenges for patients with greater needs. Meeting higher levels of patient care needs was difficult in a system where prioritizing competing responsibilities was a recurrent issue. Inpatient nurses shared:

Educat[ing] people and empower[ing] them about their health. [I]t's kind of lostwhen we have so many [tasks] that we're responsible for, the patient gets lost in all of these things. For patients requiring ongoing sub‐acute care, limited weekend and holiday hospital and skilled nursing facility personnel added to the difficulty of arranging discharges and executing care plans.

Social workers noted:

[S]ometimes people are ready for discharge and there's noprimary care physician [willing to follow them].

Obtaining additional support following discharge was another concern for patients with homecare needs:

With the Medicaid changeshomecare is going to be less [than] what's provided [now]. So they're going into a lesssafe environment. [Social worker]

Illness Severity and Health Needs

The ability to cope with disease and related stressors depended on complexity of illness, level of health literacy, and underlying psychiatric issues overlapping with the theme of psychosocial stability. Early identification and mitigation of potential postdischarge complications required PCC collaboration.

All groups agreed that patients with chronic complex comorbidities often warranted frequent access to the inpatient setting regardless of outpatient medical care:

I'm not surprised [my patient was readmitted] becausealmost anything that goes wrong leads her to the hospital. Her readmission is not avoidable because of the severity of her illness. [Primary care physician]

With patients living longer with terminal illness, several groups voiced concern regarding the frequency of hospitalizations:

People [go] into hospice in the last week of their life as opposed to in the last six months of their life.The doctor has to bring this up [I] can't do it. [Homecare nurse]

Another prevalent issue was the emotional stress that accompanies acute or exacerbations of illness. One patient shared,

I also have a four‐year‐old son. Obviously, I'm not able to care for him as much as I was. My wifehas been diagnosed with leukemia.

Psychosocial Stability

Discharge from the hospital often requires psychosocial adjustment, which may be overlooked, underestimated, or dismissed by patients and providers.

[One patient] was very visually impaired. Lives by himself. But he's youngso he wanted to go home [not] a nursing home. He got home. He got up in the middle of the night. [P]ut the wound vac[uum] on the counter [and it] fell. It broke. It started beeping. He panicked, couldn't get in touch with any of the visiting nurses because it was 2:00 a.m. And he [was readmitted], and now is saying he wants to go to sub‐acute, because he can't handle it at home. [Social worker]

Engaging patients who seemed capable of participating in their own care was often frustrating for providers:

It's depressing because you're trying to help somebody [but] they don't want to help themselves and you know you'll see them right back [in the hospital] again. [Inpatient nurse]

Social support and socioeconomic factors also impacted patients' and families' ability to cope and adjust to the community after discharge. One family member commented that he and his wife have always cared for the patient together but now he cares for her alone and must hire a private duty aide to assist.

Medications

The degree to which obtaining, understanding, and taking medications exists as an impediment to safe transitions was patient specific and dependent on all of the patient‐centered themes above. Recognition and effective intervention required a multitiered, multidisciplinary approach. Homecare nurses reflected:

Discharge planning doesn't ensure that there is someone that can go to the pharmacy to get [medications] until the [visiting] nurse comes in and sets something up.

Methods used for medication education were not always effective in reaching the patient:

I shouldn't really say that they didn't [discuss medication side effects] because I was in a lot of pain. I really don't recall somebody giving me specific [information on] side effects on the medication. [Patient]

DISCUSSION

We categorized our findings into5 principle themes that influence care transitions: teamwork, systems navigation and management, illness severity, and health needs, psychosocial stability, and medications. Many of these themes have been targeted in the literature for interventions to reduce readmissions and improve care transitions. An overarching theme of our study was the importance of the Patient Care Circle, a support system required to implement and execute comprehensive patient‐centered plans for safe and effective transitions across all settings.

Collectively, our themes emphasized that communication and comprehensive planning between all members of the PCC were instrumental to the circle's ability to address issues pertaining to the patient‐centered themes: systems navigation and management, illness severity and health needs, psychosocial stability, and medications. The strength of the bonds and collaboration within the PCC were directly dependent on the success of teamwork.

The interplay between the 4 patient‐centered themes and the degree to which they affect readmissions were variable and patient dependent. Complexities of the healthcare system and issues surrounding medications became more apparent with worsening disease severity and psychosocial instability. Complicated patients requiring more multidisciplinary interaction highlighted limitations of dispersed teams and staffing ratios. Patients faced with insurance restrictions, difficulties attending appointments, and obtaining medications required pooling the efforts of multiple PCC members to help them. Thus, these themes emphasized not only the importance of teamwork required for care coordination, but also guided the membership of the PCC to meet the patient's specific needs across the inpatient and outpatient settings.

When participants were asked to identify modifiable reasons for readmissions, the overwhelming collective response was inadequate communication and collaboration among PCC members. Clear role assignments and delegation of responsibility were also necessary to avoid gaps in care. Significant barriers to improvement included limited resources and inability to maintain the integrity of the support network needed for safe transitions.

Finally, we compared and contrasted the perceptions of the different disciplines on the factors contributing to each patient's readmission. Over all, there was substantial overlap. However, each perspective added additional layers of information allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of the problem. This demonstrated the utility of multidisciplinary patient‐centered interviews to examine readmissions and elucidate areas for intervention.

Several disciplines were not included in interviews or focus groups but were identified by our study participants as integral to a comprehensive Patient Care Circle. These include emergency medicine physicians, inpatient and outpatient pharmacists, and outpatient social workers. Some disciplines were not included due to challenges identifying discrete providers and with arranging interviews or focus groups. As their roles were mentioned several times in multiple forums, we have included them in our descriptive framework.

We designed this study with the hope of completing a full complement of patient‐specific interviews that included all stakeholders for 4 male and 4 female patients. For several reasons, we were unable to do so including challenges contacting providers and family members, and coordinating the timing of interviews with patient visits. Further, our focus on English‐speaking patients admitted to general medicine teams may limit generalizability to other vulnerable patient groups. Nevertheless, we believe we succeeded in interviewing a representative sample and obtained thematic saturation with the information obtained from our interviews and focus groups.

Last, the focus of this project was to obtain the perspectives of a full spectrum of stakeholders in the care transitions process to gain a better understanding of the reasons for readmissions. Although we did ask study participants to identify areas that may have been modifiable, we did not expand the discussion to include potential interventions, which will be the next step in our study.

CONCLUSION

Our article describes 5 main themes derived from the perspectives of multiple stakeholders involved in the care transitions process. An overarching theme was the importance of a multidisciplinary, coordinated collaborative care circle to ensure safe patient‐centered care in all settings.

The results of this study can be used by researchers and applied by care providers to improve the care transitions process. Researchers can build on our model by studying methods and interventions to improve the function of the care circle and design guidelines to create a more effective and integrated network. Institutions can adapt our methodology and tools to identify the needs of their own patient population and optimize membership in the PCC accordingly.

We feel that improving the structure and function of the care circle is necessary prior to designing interventions targeting the patient‐centered themes. Strengthening the teamwork of the PCC is fundamental to improving the quality of care transitions and reducing preventable readmissions.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patients, family members, social workers, nurses, and physicians who participated in their study. The authors are grateful to their research assistants for their assistance with conducting interviews, focus groups, and data collection.

Disclosures: This study was supported by the Weill Cornell Clinical and Translational Science Center: UL1 RR024996. Dr. Press is supported in part through funds provided to him as a Nanette Laitman Clinical Scholar in Public Health at the Weill Cornell Medical College. An earlier version of the article was presented as a poster at the Society of Hospital Medicine annual conference in San Diego, California in 2012.

- , , , et al. Factors contributing to all‐cause 30‐day readmissions: a structured case series across 18 hospitals. Med Care. 2012;50:599–605.

- , , , , , . Perceptions of readmitted patients on the transition from hospital to home. J Hosp Med. 2012;7(9):709–712.

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement.State Action on Avoidable Rehospitalizations (STAAR) initiative. Available at: http://www.ihi.org/offerings/Initiatives/STAAR/Pages/Improvement.aspx. Accessed January 28, 2013.

- , , , et al. Transition of Care Consensus Policy Statement, American College of Physicians–Society of General Internal Medicine–Society of Hospital Medicine–American Geriatric Society–American College of Emergency Physicians–Society of Academic Emergency Medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(8):971–976.

- , , , . Moving beyond readmission penalties: creating an ideal process to improve transitional care. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(2):102–109.

- , , , , . Interventions to reduce 30‐day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:520–528.

- , , , . Promoting effective transitions of care at hospital discharge: a review of key issues for hospitalists. J Hosp Med. 2008;2:314–323.

- , , , , . How‐to guide: improving transitions from the hospital to community settings to reduce avoidable rehospitalizations. Cambridge, MA: Institute for Healthcare Improvement; June 2012. Available at: www.IHI.org. Accessed December 31, 2012.

- BOOSTing care transitions. Philadelphia, PA: Society of Hospital Medicine; 2008. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/ResourceRoomRedesign/RR_CareTransitions/CT_Home.cfm. Accessed October 20, 2012.

- , , . Predictive validity of a questionnaire that identifies older persons at risk for hospital admission. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1995;43(4):374–377.

- . The care transitions program: healthcare services for improving quality and safety during care hand‐offs. Denver, CO: Care Transitions Program; 2007. Available at: http://www.caretransitions.org. Accessed October 22, 2012.

- , , , , . Did I do as best as the system would let me? Healthcare professional views on hospital to home care transitions. J Gen Intern Med. 2012;27(12):1649–1656.

- , . The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Chicago, IL: Aldine; 1967.

- . The significance of saturation. Qual Health Res. 1995;5(2):147–149.

- . Understanding reliability and validity in qualitative research. Qual Rep. 2003;8(4):597–607.

The focus on care transitions and readmissions is expanding beyond the development of risk scores based on objective clinical data to quality improvement interventions involving the key stakeholders in the process, namely the patients and their multidisciplinary providers.[1, 2] The Institute for Healthcare Improvement's State Action on Avoidable Rehospitalizations initiative promotes formulating a specific transition plan and developing multidisciplinary management strategies for all patients.[3] The Transition of Care Consensus Policy Statement developed by a coalition including the American College of Physicians and Society of Hospital Medicine emphasizes accountability, communication, and involvement of the patient and family members in plans of care.[4] Yet, interventions to reduce readmissions and improve the quality and safety of care transitions remain only modestly and inconsistently effective.

Successful interventions are those that are combined and coordinated, and shared across the hospital and community settings.[5] In this study, we sought to understand the issues leading to readmissions and barriers as perceived by patients, family members, physicians, nurses, and social workers. We compared and contrasted the perspectives by discipline and used this information to design a descriptive framework of a multidisciplinary, collaborative, and coordinated support network integral to effective care transitions, which we term a Patient Care Circle (PCC) (Figure 1).

METHODS

Study Design

We recruited a purposive sample of general medicine patients with same‐site 30‐day readmissions, and those directly involved in their care, to participate in interviews and focus groups to investigate explanations for unplanned readmissions (Table 1). We sought subjects' perspectives based on extrapolations from previous research that identified multiple stakeholders involved in the care transitions process,[1, 2, 5, 6, 7, 8] and our own professional experience with patient readmissions.

| Role | No. (%) | No. Interviewed | No. in Focus Group | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Patient | 12 | NA | ||

| Male | 10 (90.9) | |||

| Average age, y, range | 3172 | |||

| Insurance | ||||

| Medicare | 5 (41.7) | |||

| Medicaid | 1 (8.3) | |||

| Medicare/Medicaid | 2 (16.7) | |||

| Private | 4 (33.3) | |||

| Race | ||||

| White | 8 (66.7) | |||

| Black | 2 (16.7) | |||

| Other | 2 (16.7) | |||

| Has PMD | 9 (75.0) | |||

| Has home caregiver (family or aide) | 10 (90.9) | |||

| Physician | ||||

| Hospitalista | 9b | |||

| Index | 10 | |||

| Readmit | 9 | |||

| Primary care physician | 5 | NA | ||

| Other provider | ||||

| RN | ||||

| Inpatient staff | 5 | 7 | ||

| Visiting home | NA | 6 | ||

| Social work | NA | 6 | ||

| Other caregivers | ||||

| Family | 2 | NA | ||

| Home aides | 0 | NA | ||

| Total | 43 | 28 | ||

Site Selection

All interviews and focus groups were conducted at New YorkPresbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center (NYP/WC), a large urban academic medical center in New York City serving a racially and socioeconomically diverse population. The institutional review boards at Weill Cornell Medical College and Hunter College approved this study.

Data Collection Tools

We developed semistructured interview and focus group guides (see Supporting Information, Appendixes 17, in the online version of this article) by reviewing published literature[8, 9, 10, 11, 12] and readmission pilot data that identified challenges associated with hospital discharges. Interviews were patient specific, and providers involved directly in their care were asked to consider reasons for the patients' readmissions and whether they could have been prevented. Provider interview guides were modified from the patient interview script and tailored toward their role in the patient's care.

One focus group guide was used for all sessions, allowing us to compare and contrast emerging themes across disciplines. Participants were asked to discuss perceived causes for readmissions and barriers to improvement.

All questions were open‐ended to gain insight into participants' beliefs regarding the causes of readmissions and to limit researcher bias. We iteratively reviewed and modified the guides to ensure the questions were effectively worded.

Recruiting

Using a centralized clinical database, we identified patients aged 18 years and older for interviews, who were readmitted within 30 days to NYP/WC between May 2011 and May 2012, and had an attending hospitalist during the initial and readmission visits. We confirmed patients' English fluency and cognitive ability by contacting their attending physician. Patients provided written consent prior to interview.

For interviews, we asked patients to identify their outpatient physicians and providers; inpatient hospitalists and providers were identified from the patients' charts. For focus groups, we recruited volunteers among all division hospitalists and solicited volunteer inpatient nursing, social work, and homecare nursing participants through organizational liaisons (Table 1).

Data Collection

We interviewed patients in person at their bedside. We interviewed physicians and other caregivers in person or by telephone during the course of the patient's readmission. We conducted 4 discipline‐specific 90‐minute focus groups for hospitalists, inpatient staff nurses, homecare nurses, and hospital social workers. Patient interviews and focus groups were audio‐recorded and transcribed using a professional service.

Data Analysis

We analyzed 47 transcripts (43 interviews, 4 focus groups) during research group meetings using grounded theory[13] to generate overarching themes felt to influence readmissions through iterative reviewing of transcripts. We attributed codes to salient text and documented recurring topics that emerged. Two researchers independently assessed responses from the patient‐specific interviews for variability among the various disciplines. We ended our data collection after we ceased to find new topics from participants (thematic saturation).[14]

Three researchers, in consultation with the larger team, coded the 4 focus group transcripts to generate a codebook with definitions and examples of recurring concepts. They then coded the 43 interview transcripts using the codebook. The entire team met regularly to address questions and potential discrepancies.

We achieved greater trustworthiness of the analysis by using multiple modes of triangulation, a qualitative method that relies on points of comparison and contrast.[15] We achieved methodological triangulation by using both interviews and focus groups, and achieved internal triangulation by having researchers in the clinical, social, and behavioral sciences routinely critique the evolving codebook.

RESULTS

We recruited 43 interview and 28 focus group participants (Table 1). From our transcript analysis, we generated 22 codes and categorized them into 5 themes embodying the issues pertinent to readmissions from the perspective of the stakeholders: (1) teamwork, (2) health systems navigation and management, (3) illness severity and health needs, (4) psychosocial stability; and (5) medications (Table 2).

We applied these codes and themes to build a descriptive framework depicting what we believed is the essential foundation for successful care transitions, a collaborative unified patient‐centered network to address complex healthcare‐related issues across disciplines and across settings (Figure 1). Our model illustrates the interplay between the various physician and care‐provider roles as well as the relationship of the structure of the care circle to each theme.

Care Circle Theme

Teamwork

Comprehensive, effective collaboration and communication among members of the PCC were required for the circle to function successfully and establish safe ongoing patient care across settings. Teamwork required a shared purpose and aligned incentives among all stakeholders to work as a unified patient‐centered network.

Dysfunctional teamwork led to fragmented care. Hospitalists and patients cited difficulties coordinating in‐hospital management plans with multiple consulting subspecialists. Social workers ascribed 1 potential cause for unplanned readmissions to insufficient feedback from homecare agencies regarding patients following hospital discharge:

I wouldn't mind hearing [from the home agencies][the patient] won't let me in the door' patient's doing well' or patient's still not compliant.' If we don't knowthen we can't address it [until] they come back in [to the hospital].

Meanwhile, accurate handoff of information affected the care provided by homecare nurses:

We go into assess [the patient at home] and we see something totally different than what wason a piece of paper.

Patient‐Centered Themes

Four patient‐centered themes were identified that posed challenges in the transitions process and required the support and teamwork of the PCC to deal with effectually.

Health Systems Navigation and Management

The complexities of the healthcare system in the hospital and in the community presented challenges for patients with greater needs. Meeting higher levels of patient care needs was difficult in a system where prioritizing competing responsibilities was a recurrent issue. Inpatient nurses shared:

Educat[ing] people and empower[ing] them about their health. [I]t's kind of lostwhen we have so many [tasks] that we're responsible for, the patient gets lost in all of these things. For patients requiring ongoing sub‐acute care, limited weekend and holiday hospital and skilled nursing facility personnel added to the difficulty of arranging discharges and executing care plans.

Social workers noted:

[S]ometimes people are ready for discharge and there's noprimary care physician [willing to follow them].

Obtaining additional support following discharge was another concern for patients with homecare needs:

With the Medicaid changeshomecare is going to be less [than] what's provided [now]. So they're going into a lesssafe environment. [Social worker]

Illness Severity and Health Needs

The ability to cope with disease and related stressors depended on complexity of illness, level of health literacy, and underlying psychiatric issues overlapping with the theme of psychosocial stability. Early identification and mitigation of potential postdischarge complications required PCC collaboration.

All groups agreed that patients with chronic complex comorbidities often warranted frequent access to the inpatient setting regardless of outpatient medical care:

I'm not surprised [my patient was readmitted] becausealmost anything that goes wrong leads her to the hospital. Her readmission is not avoidable because of the severity of her illness. [Primary care physician]

With patients living longer with terminal illness, several groups voiced concern regarding the frequency of hospitalizations:

People [go] into hospice in the last week of their life as opposed to in the last six months of their life.The doctor has to bring this up [I] can't do it. [Homecare nurse]

Another prevalent issue was the emotional stress that accompanies acute or exacerbations of illness. One patient shared,

I also have a four‐year‐old son. Obviously, I'm not able to care for him as much as I was. My wifehas been diagnosed with leukemia.

Psychosocial Stability

Discharge from the hospital often requires psychosocial adjustment, which may be overlooked, underestimated, or dismissed by patients and providers.

[One patient] was very visually impaired. Lives by himself. But he's youngso he wanted to go home [not] a nursing home. He got home. He got up in the middle of the night. [P]ut the wound vac[uum] on the counter [and it] fell. It broke. It started beeping. He panicked, couldn't get in touch with any of the visiting nurses because it was 2:00 a.m. And he [was readmitted], and now is saying he wants to go to sub‐acute, because he can't handle it at home. [Social worker]

Engaging patients who seemed capable of participating in their own care was often frustrating for providers:

It's depressing because you're trying to help somebody [but] they don't want to help themselves and you know you'll see them right back [in the hospital] again. [Inpatient nurse]

Social support and socioeconomic factors also impacted patients' and families' ability to cope and adjust to the community after discharge. One family member commented that he and his wife have always cared for the patient together but now he cares for her alone and must hire a private duty aide to assist.

Medications