User login

Caregivers of Dementia Patients: Mental Health Screening & Support

CE/CME No: CR-1606

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Describe the adverse consequences that caregivers of persons with Alzheimer disease or other dementias commonly experience.

• Identify reliable and validated tools in the public domain available for use in primary care settings to assess a caregiver's well-being.

• List interventions that are known to support and improve the lives of caregivers seeking care.

• Discuss the impact of support groups on depression and burden of care experienced by caregivers.

• Define the role of primary care providers in reducing the negative aspects of caregiving.

FACULTY

Nancy Langman is a mental health and public health nurse practitioner on Martha’s Vineyard and an Adjunct Clinical Instructor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

The author has no financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid for one year from the issue date of June 2016.

Article begins on next page >>

Caregivers, mostly family and friends, play an important role in the complex care of persons with Alzheimer disease and other dementias. Primary care providers are uniquely positioned to assess for the negative consequences of caregiving, including depression, anxiety, and caregivers' failure to care for their own health needs. This article provides you with reliable, valid screening tools and recommendations for evidence-based interventions to increase the caregiver’s and patient’s quality of life and care.

Henry, a retired health care administrator, received a diagnosis of Alzheimer disease in his early 80s. Given his career experience, he knew where this disease might take him. His wife, Joann, worked in admissions in a nursing home prior to retirement and was equally informed of the course of the disease. They were among the more fortunate ones struggling with this life-changing diagnosis, in that they had a great primary care provider, access to some of the best neuropsychologists and neurologists in the country, financial stability, and adult children nearby.

Caregivers are a rapidly growing segment of the system of care in the United States, with more than 15 million providing care for those with Alzheimer disease (AD) and other dementias, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.1 Lack of training and support puts caregivers at risk for depression, anxiety, and failure to take care of their own health.2

The incidence and prevalence of dementia continue to increase as the population ages, placing an enormous emotional, physical, and economic burden on caregivers as well as families and society. Given our rapidly growing elderly population and the important role caregivers play, providing evidence-based care and support for caregivers of dementia patients should be a priority for primary care providers.3 Progress in this area requires primary care practitioners to take a lead role in addressing the complex issues that adversely affect caregivers and their loved ones.3 Nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) are in a pivotal position to implement caregiver screening and provide referrals to evidence-based interventions.

Who are the caregivers?

Caregivers in the US are predominantly women, and they provide 75% to 80% of long-term care in the community.4 They are largely untrained, unsupervised, unpaid, and undersupported in our society. There are many faces of caregivers: elderly spouses who themselves have health care challenges; adult children, often referred to as the “sandwich generation” as they care for their own families as well as their aging parents; nieces, nephews, and other relatives who find themselves in the position of being the only family left to care for a loved one; and paid caregivers, who also experience the stress of caregiving. Caregivers face many challenges that create both psychological and physical stress, as they are increasingly expected to provide more demanding and complex care, including medication management.4

The MetLife Mature Market Institute reports that 20% of working female caregivers older than 50 experience depression, compared to 8% of peers who are not caregivers.5 Depression among caregivers is well documented, with evidence showing that clinically significant symptoms of depression occur in 40% to 70% of caregivers and that 25% to 50% of these caregivers meet criteria for major depression.6

Continue for assessment tools >>

Assessment Tools

Assessment tools are commonly used to screen for known negative effects of caregiving and to monitor these effects following targeted interventions. Many caregiver assessment tools exist. According to the Family Caregiver Alliance’s Selected Caregiver Assessment Measures, recent efforts have focused on revising available tools to make them shorter and easier to use.7 Newer assessment models attempted to blend content areas (depression, burden, health behaviors, and quality of life) to establish a single screening instrument, in contrast to the stand-alone tools that measure only one domain.8

It is important to select an assessment tool that is easy to administer, reliable and valid, and in the public domain.9-17 In its 2002 consensus project, the Family Caregiver Alliance recommended that assessments be multidimensional in approach, periodically updated, and reflective of culturally competent practice.18 In addition, they believe that those doing the assessments should have relevant training on the role of caregivers and the impact of caregiving.

The Caregiver Assessment Grid was developed by the Michigan Dementia Coalition following a review of 19 scales that measure caregiver burden, stress, quality of life, memory, behavior, and perceptions of caregiving tasks (among others).19 Tools range from simple to complex, with some having Yes or No answers and others using four- or five-point Likert scales. Tools listed in the Caregiver Assessment Grid that meet the criteria for brevity and are in the public domain are discussed here.

The Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) was initially a 29-item tool that was reduced first to 22 items and then further to 12 items, with a brief screening version containing only four items.10,20 Correlations between the reduced-length versions were .92 to .97 for the short version and .83 to .93 for the screening version.7 The Zarit screening version has a sensitivity of 98.5% and a specificity of 94.7%.10 The ZBI is frequently applied to assess burden, has been cited in many studies, and has been validated for use in other languages.21 This interview tool measures subjective burden, distress, perceptions of social and physical health, financial and emotional burden, and relationship with care recipient. The ZBI has been embedded in other blended assessment tools; for example, it is part of the California Caregiver Resource Centers Uniform Assessment Tool.19

The Pearlin Caregivers’ Stress Scales are based on a conceptual model of the Alzheimer’s Caregiver Stress tool, an eight-item scale developed by the Alzheimer’s Association that links “yes” answers to helpful websites.22 This 15-item instrument addresses cognitive status, problem behaviors, overload, relational deprivation, family conflict, job/caregiving conflict, and economic strain, among others.22

The American Medical Association (AMA) published an 18-item caregiver assessment tool for health care professionals in 2002, encouraging them to identify the needs of caregivers. This tool includes 16 Yes or No questions and two global scale items.19,23

The Risk Appraisal Measure (RAM) developed by Czaja et al is a 16-item assessment that takes 5 to 7 minutes to administer and identifies risk areas for caregivers. This instrument explores six domains of caregiver risk that are potentially amenable to intervention: depression, burden, self-care and health behaviors, social support, safety, and patient problem behaviors. The RAM was developed and validated using data from REACH II (Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health)11 in a study involving 642 participants (219 white; 211 black; 212 Hispanic).11 The authors reported acceptable concurrent validity and internal consistency for the entire scale for the overall sample (Cronbach alpha = .65) and across racial and ethnic groups.11 The authors acknowledge that the Cronbach alpha (a measure of internal consistency, or how closely related a set of items are as a group) is relatively low but explain that this is expected due to the six distinct domains the instrument attempts to measure. The findings from this study highlight the challenge of maintaining reliability and validity in blended screening tools.

The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) is a broadly used, well-known tool that has been used extensively with the elderly population.24 The GDS has both a long (30 questions) and short (15 questions) version. In the shorter version, five of the Yes or No questions indicate depression if answered negatively and 10 indicate depression if answered positively. The long and short forms were compared in a validation study and found to be successful in differentiating depressed from nondepressed adults (r = .84, P < .001).25

The Center for Epidemiology Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) is a 20-item self-report scale that takes 5 minutes to administer and measures depressive feelings and behaviors over the previous week.16 It is commonly used to assess depression in caregivers.26 Matschinger and colleagues have expressed concerns about the CES-D being administered to caregivers, many of whom are elderly, because the questions in this instrument are oppositely worded: One part asserts and the other denies the content to avoid a tendency for respondents to give positive answers to questions (known as acquiescence).27 These researchers raise the concern that opposite wording may affect the reliability of the scale and recommend against its use in elderly persons.

The Caregiver Burden Scale, adapted version from the Family Practice Notebook, is a 22-item version of the Caregiver Burden Interview.28 A 12-item version was developed by Bèdard et al, along with a four-question screening version.10

There are several easily accessible online self-assessment tools. The AMA Caregiver Self-Assessment is self-scored and offers help interpreting the scores, suggestions for next steps, and resource information.23 The Caregiver Stress Self-assessment offered by Mass.gov is a modified version of Dr. Steven Zarit’s work and is also self-scored.29 The Veterans Administration (VA) has a more complex Self-Assessment Worksheet that focuses on roles and responsibilities as well as stress; a list of “next step” actions is offered, along with information about VA resources.30 While these tools allow users to assess their well-being in privacy, they do not offer the support and interventions that face-to-face screening can include.

Following Henry’s confirmed diagnosis of AD, his NP screened him for depression using the Geriatric Depression Scale and prescribed an antidepressant. She recommended that he take donepezil in the hope of slowing the progression of memory loss in the early to middle stages of the disease. She also screened his wife for her level of caregiver stress using the Zarit Burden Interview, shortened version, and referred her to a caregiver support group, informing her of respite services, including a supportive day program offered at the local Council on Aging. She also referred Henry to a memory loss support group in the community. Despite the available support, the stress in their life was palpable.

Continue for interventions >>

Interventions

Assessing caregiver challenges is only half the task of seeking to improve their lives. The next step is to provide advice and referral for supportive services including structured, valid, and reliable interventions. Structured support groups have been studied locally, nationally, and internationally.26,31,32 Burns and colleagues developed a study to test two 24-month primary care interventions for caregivers of those with AD, focused on alleviating caregivers' distress.33 In this randomized clinical trial, subjects were assigned to one of two groups: one received behavior management alone and the other added stress coping to the behavior management. Those who received only behavior management had worse outcomes for general well-being and depression. The researchers concluded that “brief primary care interventions may be effective in reducing caregiver distress and burden in the long-term.” This study underscores the need for a multifaceted approach to supporting caregivers in their complex and demanding role.

For depression

Depression is a common caregiver complaint; however, measuring incidence and prevalence of mental health issues is a challenge. Studies evaluating the effectiveness of interventions have had mixed results. The REACH II study showed that although caregivers do not usually meet criteria for clinical depression, they nonetheless experience depressive symptoms.34 But, although depression is the most widely studied health consequence of being a caregiver for someone with AD,35 experts report that there is little consistent evidence about the effectiveness of caregiver interventions.

A prospective single-blind randomized controlled trial with a three-month follow-up evaluated whether a cognitive–behavioral family intervention, consisting of education, stress management, and coping skills training, was effective in reducing the burden of care among caregivers of persons with AD.36 Caregiver burden was assessed at pretreatment, posttreatment (nine months after trial entry), and three-month follow-up (12 months after trial entry), using measures of psychological distress and depression and general health. The results showed that the intervention resulted in a significant reduction in distress and depression for caregivers and had a positive effect on modifying patient behaviors. Unfortunately, the intervention is lengthy and requires special training for the interventionist.

A study by Chu and colleagues explored providing a 12-week structured support group to Taiwanese caregivers of those with dementia and found that the support group reduced caregivers’ depression but did not have an effect on burden of care.37 Two other studies showed that support groups have a significant effect on depression and decrease caregiver burden and bother.38,39 Another study of spouses of persons with AD (n = 406) randomly assigned them to either a support and counseling intervention (comprised of six counseling sessions followed by a support group) or to a control group that received routine care.40 The authors assessed all participants before and after the intervention using the Geriatric Depression Scale and found significantly fewer symptoms of depression in the intervention group; these effects were sustained for 3.1 years postintervention. They also found that only group interventions based on psychoeducational theory had a positive effect on depression of caregivers. In a subsequent analysis, the researchers concluded that additional studies of psychosocial interventions for caregivers are warranted and should incorporate biological measures of physical health outcomes.41

Lavretsky, Siddarth, and Irwin conducted the first randomized placebo-controlled double-blind trial of the use of an antidepressant to reduce depression and improve resilience and quality of life among caregivers of persons with dementia.42 Their study demonstrated the efficacy of antidepressant therapy for caregiver depression: 86% of caregivers in the intervention group achieved remission, compared to 44% in the placebo group. Caregivers treated with antidepressants reported reduced anxiety, improved resilience, and decreased burden and stress. The authors also found that the level of depression and burden correlate to the severity of the care recipient’s dementia, related disability, and behavioral problems.42 However, these findings are limited due to the study’s small sample size (n = 28).

Elliott and colleagues report that depression serves a mediating function between the health of caregivers and their experience of burden.38Mediating variables play an important role in governing the relationship between caregiver burden and the health of the caregiver, while moderating variables change the effect between them when increased or decreased. In the first case, caregiver education would likely mediate burden of care; in the second, caregiver sleep (or lack thereof) would moderate the impact of caregiving on depression.

For caregiver burden

Three areas that cause burden for caregivers are activities of daily living, such as eating, bathing, and toileting; instrumental activities of daily living, encompassing shopping, food preparation, and financial management; and behavior and safety, including falls, fires, and driving.43 Caregivers experience physical symptoms, depression, and feelings of burden when faced with a greater number of tasks, more problematic behaviors, and/or more family disagreements.44

The concept of caregiver burden is the focus of many studies, all of them seeking answers for how best to support caregivers caring for a loved one with AD.37,43,45,46 In a multicenter prospective randomized study conducted in 11 hospital and nonhospital psychiatric outpatient clinics in southern Europe (N = 115), the intervention group participated in eight individual sessions over four months that focused on learning strategies for managing AD patient care.46 Data were collected on caregiver stress, quality of life, and perceived health to determine the impact on caregiver burden. The intervention was found to minimize caregiver burden as measured by the ZBI.

Lai and Thomson evaluated a random sample of family caregivers (n = 340) and concluded that providing tangible services and resources should be the first step in reducing burden of care. They report that caregivers’ perceived adequacy of support services predicts caregiver burden. They noted that emotional support results in only marginal benefits.45 Other studies have concurred with the finding that support groups provide emotional support, information, and problem-solving skills to caregivers but do not reduce caregiver burden.31

For caregivers of those with dementia, the strongest predictor of distress is care recipients’ problem behaviors.26 Some theorize that the distress that caregivers experience has multiple components, including belligerence, lack of cooperation, oppositional behaviors, and disruption of sleep patterns of the care recipient.13 Support groups should address behavioral interventions that caregivers can use when faced with the challenging behaviors that often concur with neurocognitive disorders, including confusion, wandering, agitation, crying, swearing, and combativeness.

Caregivers may experience increased stress as their loved one’s dementia progresses. The New York University (NYU) Caregiver Intervention is a long-running randomized controlled study of counseling and support interventions for caregivers of spouses with dementia, conducted by the NYU School of Medicine. Among the array of published analyses of data from this study was a trial reporting that counseling and support interventions reduced the rate of nursing home placement by 28.3%, compared with usual care, and delayed nursing home placement; 61.2% of this delay was attributed to social support, response to patient behaviors, and reduced depression.47 Comprehensive counseling and support provided during the progression of AD patients transitioning to institutionalization can be beneficial to spouses and may translate more broadly to caregivers in general.48

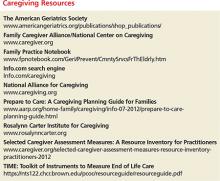

Equipping caregivers to manage the most difficult aspect of their role should be a priority. Many towns and cities offer day programs for those with memory disorders, allowing for respite for caregivers. Councils on aging are a great resource for service information and specialized programs. For those who meet the income guidelines, there may even be financial support for family caregivers. To seek out services, contact the national Alzheimer’s Association (Alz.org) or a local branch. For information on behavioral interventions, Caregiver.org has many available resources on a variety of topics. (Additional resources are listed in “Caregiving Resources.”)

Continue for caregiver stress and self-care >>

Caregiver stress and SELF-CARE

Primary care providers can be instrumental in not only offering referral to services to reduce caregiver stress but also encouraging self-care behaviors for caregivers. They have the opportunity, early on, to anticipate the stresses that caregivers may experience as their loved one’s disease progresses and to provide helpful referral for services (including psychotherapy and support groups), information, and support to preventively address functional ability and self-care behaviors.

The relationship between caregiver stress and self-care behavior has been widely studied. Using the Caregiving Hassles Scale, Kinney and Stephens examined the mediating function of the relationship between caregiving stress and self-care behavior. They found caregiver stress to correlate to self-rated health at a statistically significant level (r = .30, P = .003).13 On a positive note, the investigators also found that the more symptoms family members reported (depression, poor health), the more self-care behaviors they used.

Lu and Wykle also used the Caregiving Hassles Scale in their correlational crossfunctional study. Caregivers (n = 99) were assessed for the mediating function of the relationship between caregiving stress and self-care behavior in response to symptoms.49 Those who reported higher levels of caregiving stress also reported poorer self-rated health, poorer physical function, high levels of depressed mood, and more self-care behaviors at a statistically significant level (r =.30, P = .003, Cronbach’s alpha = .95). The researchers determined that depressed mood was a strong mediator between caregiver stress and response to the symptoms with self-care behaviors.

Unsteady on his feet, Henry became a fall risk. His growing confusion and cognitive decline led to increased depression and agitation, which reduced his socialization and physical activity. Over time, this resulted in a disturbing chain of events, including urinary tract infections, hospitalization, and behavior changes that were upsetting to his wife and children as well as to Henry. Joann was not sleeping well and contracted a cold that turned into pneumonia, leading to a hospitalization. Through all of this, Joann knew that she could call Henry’s NP for advice and support. She found solace in knowing that the caregiver support group she attended regularly would always be there to encourage and inform her and that Henry’s support group would not only give her respite as a caregiver but also provide Henry with cognitive stimulation shown to enhance the well-being of those experiencing memory loss. These groups soon became her lifeline. Without vital early screenings, this family would not have adequately managed the difficulties brought on by Henry’s unexpected diagnosis.

Continue for summary and conclusions >>

Summary and conclusions

Extensive research on caregivers has focused on depression, burden of care, and self-care issues, with mixed findings. Gottlieb and colleagues report that caregivers struggle with the “apparent sadness, listlessness, and vegetative behavior” of their loved one struggling with AD.35 Primary care providers are in a pivotal position to improve caregivers’ health status using reliable and valid assessment tools and offerring referral to services that have been shown to help caregivers in their complex and challenging role.

Support groups, assistance with behavioral interventions, information about the disease process and effective interventions, medication for clinical depression, respite and day programs for persons with neurocognitive disorders, and encouragement of self-care all reduce caregiver stress. Offering effective interventions can improve the physical and mental health of burdened caregivers and positively impact the lives of their loved ones.

Given the growing number of caregivers and the significant effect of caregiving on their health, staying alert should be a priority in all practices. Simply adding two questions to those we regularly ask—Do you care for a loved one struggling with memory loss? How many hours a week do you provide care?—can illuminate the challenges caregivers face, so we can monitor their health status appropriately.

1. 2015 Alzheimer’s Disease Facts and Figures. Chicago: Alzheimer’s Association; 2015. www.alz.org/facts/downloads/facts_figures_2015.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2016.

2. Wallis L. Reach VA helps family caregivers of dementia patients. Am J Nurs. 2011;111(6):18.

3. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. 2020 Topics and objectives—objectives A–Z. Healthy People 2020. www.healthypeople.gov/2020/topics-objectives. Accessed May 20, 2016.

4. Levine C, Halper D, Peist A, Gould D. Bridging troubled waters: family caregivers, transitions, and long-term care. Health Aff. 2010;29(1):116-124.

5. MetLife Mature Market Institute, National Alliance for Caregiving, and the University of Pittsburgh Institute on Aging. The MetLife Study of Working Caregivers and Employer Health Care Costs. February 2010. www.metlife.com/assets/cao/mmi/publications/studies/2010/mmi-working-caregivers-employers-health-care-costs.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2016.

6. Zarit SH. Assessment of family caregivers: A research perspective. In: Family Caregiver Alliance. Caregiver Assessment: Voices and Views From the Field. Report from a National Consensus Development Conference. Volume II. San Francisco: Family Caregiver Alliance; 2006:14. https://caregiver.org/sites/caregiver.org/files/pdfs/v2_consensus.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2016.

7. Family Caregiver Alliance National Center on Caregiving. (2012). Selected Caregiver Assessment Measures: A Resource Inventory for Practitioners. 2nd ed. https://www.caregiver.org/selected-caregiver-assessment-measures-resource-inventory-practitioners-2012. Accessed May 20, 2016.

8. Family Caregiver Alliance. Caregivers Count Too! A Toolkit to Help Practitioners Assess the Needs of Family Caregivers. San Francisco: Family Caregiver Alliance; 2006. www.caregiver.org/sites/caregiver.org/files/pdfs/Assessment_Toolkit_20060802.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2016.

9. Antonovsky A. The structure and properties of the Sense of Coherence Scale. Soc Sci Med. 1993;36(6):725-733.

10. Bédard M, Molloy DW, Squire L, et al. The Zarit Burden Interview: a new short version and screening version. Gerontologist. 2001;41(5):652-657.

11. Czaja SJ, Gitlin LN, Schulz R, et al. Development of the Risk Appraisal Measure (RAM): a brief screen to identify risk areas and guide interventions for dementia caregivers. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57(6):1064-1072.

12. Gort AM, Mingot M, March J, et al. Short Zarit scale in dementias. Med Clin (Barc). 2010;35(10):447-449.

13. Kinney JM, Stephens MA. Caregiving Hassles Scale: assessing the daily hassles of caring for a family member with dementia. Gerontologist. 1989;29(3):328-332.

14. Locke DEC, Dassel KB, Hall G, et al. Assessment of patient and caregiver experiences of dementia-related symptoms: development of the Multidimensional Assessment of Neurodegenerative Symptoms Questionnaire. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2009;27:260-272.

15. Picot SJ, Youngblut J, Zeller R. Development and testing of a measure of perceived caregiver rewards in adults. J Nurs Meas. 1997;5(1):33-52.

16. Radloff LS, Teri L. Use of the Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression Scale with older adults. Clin Gerontol. 1986;5:119-136.

17. Seng BK, Luo N, Ng WY, et al. Validity and reliability of the Zarit Burden Interview in assessing caregiving burden. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2010;39(10):758-763.

18. Family Caregiver Alliance. Caregiver Assessment: Principles, Guidelines and Strategies for Change. Report from a National Consensus Development Conference (Vol. I). San Francisco: Family Caregiver Alliance; 2006:12. https://www.caregiver.org/sites/caregiver.org/files/pdfs/v1_consensus.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2016.

19. Michigan Dementia Coalition. Caregiver Assessment Tool Grid. The Rosalynn Carter Institute. www.rosalynncarter.org/UserFiles/Michigan%20Assessment%20Grid.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2016.

20. Zarit SH, Reever KE, Bach-Peterson J. Relatives of impaired elderly: correlates of feelings of burden. Gerontologist. 1980;20(6):649-655.

21. Miyamoto Y, Tachimo H, Ito H. Formal caregiver burden in dementia: impact of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia and activities of daily living. Geriatr Nurs. 2010;31(4):246-253.

22. Pearlin LI, Mullan JT, Semple SJ, Skaff MM. Caregiving and the stress process: an overview of concepts and their measures. Gerontologist. 1990;30(5):583-594.

23. American Medical Association. Caregiver Self-Assessment Questionnaire. National Caregivers Library. www.caregiverslibrary.org/Portals/0/CaringforYourself_CaregiverSelfAssessmentQuestionaire.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2016.

24. Greenberg SA. The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS). In: Try This: Best Practices in Nursing Care to Older Adults. Issue 4. New York, NY: Hartford Institute for Geriatric Nursing, NYU College of Nursing; 2012. https://consultgeri.org/try-this/general-assessment/issue-4. Accessed May 20, 2016.

25. Sheikh JI, Yesavage JA. Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS): recent evidence and development of a shorter version. In: Brink TL, ed. Clinical Gerontology: A Guide to Assessment and Intervention. New York, NY: The Haworth Press; 1986:165-173.

26. Pinquart M, Sörensen S. Helping caregivers of persons with dementia: which interventions work and how large are their effects? Int Psychogeriatr. 2006;18(4):577-595.

27. Matschinger H, Schork A, Riedel-Heller S, Angemeyer M. On the application of the CES-D with the elderly: dimensional structure and artifacts resulting from oppositely worded items. Int J Methods Psychiatr Res. 2006;9(4):199-209.

28. Caregiver Burden Scale. Family Practice Notebook. www.fpnotebook.com/Geri/Exam/CrgvrBrdnScl.htm. Accessed May 20, 2016.

29. Caregiver Stress Self-Assessment. www.mass.gov/elders/docs/caregiver-stress-self-assessment.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2016.

30. US Department of Veterans Affairs. Caregiver Self-Assessment Worksheet. http://www.va.gov/GERIATRICS/guide/longtermcare/Caregiver_Self_Assessment.pdf. Accessed May 20, 2016.

31. Thompson CA, Spilsbury K, Hall J, et al. Systematic review of information and support interventions for caregivers of people with dementia. BMC Geriatr. 2007;7:18-29.

32. Chien LY, Chu H, Guo JL, et al. Caregiver support groups in patients with dementia: a meta-analysis. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2011;26:1089-1098.

33. Burns R, Nichols LO, Martindale-Adams J, et al. Primary care interventions for dementia caregivers: 2-year outcomes for the REACH study. Gerontologist. 2003;43(4):547-555.

34. Schulz R, Burgio L, Burns R, et al. Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregivers Health (REACH): overview, site-specific outcomes, and future directions. Gerontologist. 2003;43(4):514-520.

35. Gottlieb BH, Thompson LW, Bourgeois M. Monitoring and evaluating interventions. In: Coon DW, Gallagher-Thompson D, Thompson LW, eds. Innovative Interventions to Reduce Dementia Caregiver Distress: A Clinical Guide. New York, NY: Springer; 2003:28-49.

36. Marriott A, Donaldson C, Tarrier N, Burns A. Effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral family intervention in reducing the burden of care in carers of patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Br J Psychiatry. 2000;176:557-562.

37. Chu H, Yang CY, Liao YH, et al. The effects of a support group on dementia caregivers’ burden and depression. J Aging Health. 2011;23(2): 228-241.

38. Elliott AF, Burgio LD, DeCoster J. Enhancing caregiver health: findings from the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s disease Health II intervention. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58:30-37.

39. Sörensen S, Pinquart M, Duberstein P. How effective are interventions with caregivers? An updated meta-analysis. Gerontologist. 2002;42(3): 356-372.

40. Mittelman MS, Roth DL, Coon DW, Haley WE. Sustained benefit of supportive intervention for depressive symptoms of caregivers in patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(5):850-856.

41. Mittelman M, Roth D, Clay O, Haley W. Preserving health of Alzheimer caregivers: impact of a spouse caregiver intervention. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2007;15(9):780-789.

42. Lavretsky H, Siddarth P, Irwin MR. Improving depression and enhancing resilience in family dementia caregivers: a pilot randomized placebo-controlled trial of escitalopram. Am J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2010;18(2):154-164.

43. Wimo A, von Strauss E, Nordberg G, et al. Time spent on informal and formal caregiving for persons with dementia in Sweden. Health Policy. 2002;61(3):255-268.

44. Koerner SS, Shirai Y, Kenyon DB. Sociocontextual circumstances in daily stress reactivity among caregivers for elder relatives. J Gerontol B Psychol Sci Soc Sci. 2010;65(5):561-572.

45. Lai DW, Thomson C. The impact of perceived adequacy of social support on caregiving burden of family caregivers. Fam in Soc: J Contemp Social Serv. 2011;92(1):99-106.

46. Martin-Carrasco M, Martin M, Valero C, et al. Effectiveness of a psychoeducational intervention program in the reduction of caregiver burden in Alzheimer’s disease patients’ caregivers. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2009;24:489-499.

47. Mittelman MS, Haley WE, Clay OJ, Roth RL. Improving caregiver well-being delays nursing home placement of patients with Alzheimer disease. Neurology. 2006;67(9):1592-1599.

48. Gaugler JE, Roth DL, Haley WE, Mittelman MS. Can counseling and support reduce burden and depressive symptoms in caregivers of people with Alzheimer’s disease during the transition to institutionalization? Results from the New York University caregiver intervention study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56(3):421-428.

49. Lu YFY, Wykle M. Relationships between caregiver stress and self-care behaviors in response to symptoms. Clin Nurs Res. 2007;16:29-43.

CE/CME No: CR-1606

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Describe the adverse consequences that caregivers of persons with Alzheimer disease or other dementias commonly experience.

• Identify reliable and validated tools in the public domain available for use in primary care settings to assess a caregiver's well-being.

• List interventions that are known to support and improve the lives of caregivers seeking care.

• Discuss the impact of support groups on depression and burden of care experienced by caregivers.

• Define the role of primary care providers in reducing the negative aspects of caregiving.

FACULTY

Nancy Langman is a mental health and public health nurse practitioner on Martha’s Vineyard and an Adjunct Clinical Instructor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

The author has no financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid for one year from the issue date of June 2016.

Article begins on next page >>

Caregivers, mostly family and friends, play an important role in the complex care of persons with Alzheimer disease and other dementias. Primary care providers are uniquely positioned to assess for the negative consequences of caregiving, including depression, anxiety, and caregivers' failure to care for their own health needs. This article provides you with reliable, valid screening tools and recommendations for evidence-based interventions to increase the caregiver’s and patient’s quality of life and care.

Henry, a retired health care administrator, received a diagnosis of Alzheimer disease in his early 80s. Given his career experience, he knew where this disease might take him. His wife, Joann, worked in admissions in a nursing home prior to retirement and was equally informed of the course of the disease. They were among the more fortunate ones struggling with this life-changing diagnosis, in that they had a great primary care provider, access to some of the best neuropsychologists and neurologists in the country, financial stability, and adult children nearby.

Caregivers are a rapidly growing segment of the system of care in the United States, with more than 15 million providing care for those with Alzheimer disease (AD) and other dementias, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.1 Lack of training and support puts caregivers at risk for depression, anxiety, and failure to take care of their own health.2

The incidence and prevalence of dementia continue to increase as the population ages, placing an enormous emotional, physical, and economic burden on caregivers as well as families and society. Given our rapidly growing elderly population and the important role caregivers play, providing evidence-based care and support for caregivers of dementia patients should be a priority for primary care providers.3 Progress in this area requires primary care practitioners to take a lead role in addressing the complex issues that adversely affect caregivers and their loved ones.3 Nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) are in a pivotal position to implement caregiver screening and provide referrals to evidence-based interventions.

Who are the caregivers?

Caregivers in the US are predominantly women, and they provide 75% to 80% of long-term care in the community.4 They are largely untrained, unsupervised, unpaid, and undersupported in our society. There are many faces of caregivers: elderly spouses who themselves have health care challenges; adult children, often referred to as the “sandwich generation” as they care for their own families as well as their aging parents; nieces, nephews, and other relatives who find themselves in the position of being the only family left to care for a loved one; and paid caregivers, who also experience the stress of caregiving. Caregivers face many challenges that create both psychological and physical stress, as they are increasingly expected to provide more demanding and complex care, including medication management.4

The MetLife Mature Market Institute reports that 20% of working female caregivers older than 50 experience depression, compared to 8% of peers who are not caregivers.5 Depression among caregivers is well documented, with evidence showing that clinically significant symptoms of depression occur in 40% to 70% of caregivers and that 25% to 50% of these caregivers meet criteria for major depression.6

Continue for assessment tools >>

Assessment Tools

Assessment tools are commonly used to screen for known negative effects of caregiving and to monitor these effects following targeted interventions. Many caregiver assessment tools exist. According to the Family Caregiver Alliance’s Selected Caregiver Assessment Measures, recent efforts have focused on revising available tools to make them shorter and easier to use.7 Newer assessment models attempted to blend content areas (depression, burden, health behaviors, and quality of life) to establish a single screening instrument, in contrast to the stand-alone tools that measure only one domain.8

It is important to select an assessment tool that is easy to administer, reliable and valid, and in the public domain.9-17 In its 2002 consensus project, the Family Caregiver Alliance recommended that assessments be multidimensional in approach, periodically updated, and reflective of culturally competent practice.18 In addition, they believe that those doing the assessments should have relevant training on the role of caregivers and the impact of caregiving.

The Caregiver Assessment Grid was developed by the Michigan Dementia Coalition following a review of 19 scales that measure caregiver burden, stress, quality of life, memory, behavior, and perceptions of caregiving tasks (among others).19 Tools range from simple to complex, with some having Yes or No answers and others using four- or five-point Likert scales. Tools listed in the Caregiver Assessment Grid that meet the criteria for brevity and are in the public domain are discussed here.

The Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) was initially a 29-item tool that was reduced first to 22 items and then further to 12 items, with a brief screening version containing only four items.10,20 Correlations between the reduced-length versions were .92 to .97 for the short version and .83 to .93 for the screening version.7 The Zarit screening version has a sensitivity of 98.5% and a specificity of 94.7%.10 The ZBI is frequently applied to assess burden, has been cited in many studies, and has been validated for use in other languages.21 This interview tool measures subjective burden, distress, perceptions of social and physical health, financial and emotional burden, and relationship with care recipient. The ZBI has been embedded in other blended assessment tools; for example, it is part of the California Caregiver Resource Centers Uniform Assessment Tool.19

The Pearlin Caregivers’ Stress Scales are based on a conceptual model of the Alzheimer’s Caregiver Stress tool, an eight-item scale developed by the Alzheimer’s Association that links “yes” answers to helpful websites.22 This 15-item instrument addresses cognitive status, problem behaviors, overload, relational deprivation, family conflict, job/caregiving conflict, and economic strain, among others.22

The American Medical Association (AMA) published an 18-item caregiver assessment tool for health care professionals in 2002, encouraging them to identify the needs of caregivers. This tool includes 16 Yes or No questions and two global scale items.19,23

The Risk Appraisal Measure (RAM) developed by Czaja et al is a 16-item assessment that takes 5 to 7 minutes to administer and identifies risk areas for caregivers. This instrument explores six domains of caregiver risk that are potentially amenable to intervention: depression, burden, self-care and health behaviors, social support, safety, and patient problem behaviors. The RAM was developed and validated using data from REACH II (Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health)11 in a study involving 642 participants (219 white; 211 black; 212 Hispanic).11 The authors reported acceptable concurrent validity and internal consistency for the entire scale for the overall sample (Cronbach alpha = .65) and across racial and ethnic groups.11 The authors acknowledge that the Cronbach alpha (a measure of internal consistency, or how closely related a set of items are as a group) is relatively low but explain that this is expected due to the six distinct domains the instrument attempts to measure. The findings from this study highlight the challenge of maintaining reliability and validity in blended screening tools.

The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) is a broadly used, well-known tool that has been used extensively with the elderly population.24 The GDS has both a long (30 questions) and short (15 questions) version. In the shorter version, five of the Yes or No questions indicate depression if answered negatively and 10 indicate depression if answered positively. The long and short forms were compared in a validation study and found to be successful in differentiating depressed from nondepressed adults (r = .84, P < .001).25

The Center for Epidemiology Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) is a 20-item self-report scale that takes 5 minutes to administer and measures depressive feelings and behaviors over the previous week.16 It is commonly used to assess depression in caregivers.26 Matschinger and colleagues have expressed concerns about the CES-D being administered to caregivers, many of whom are elderly, because the questions in this instrument are oppositely worded: One part asserts and the other denies the content to avoid a tendency for respondents to give positive answers to questions (known as acquiescence).27 These researchers raise the concern that opposite wording may affect the reliability of the scale and recommend against its use in elderly persons.

The Caregiver Burden Scale, adapted version from the Family Practice Notebook, is a 22-item version of the Caregiver Burden Interview.28 A 12-item version was developed by Bèdard et al, along with a four-question screening version.10

There are several easily accessible online self-assessment tools. The AMA Caregiver Self-Assessment is self-scored and offers help interpreting the scores, suggestions for next steps, and resource information.23 The Caregiver Stress Self-assessment offered by Mass.gov is a modified version of Dr. Steven Zarit’s work and is also self-scored.29 The Veterans Administration (VA) has a more complex Self-Assessment Worksheet that focuses on roles and responsibilities as well as stress; a list of “next step” actions is offered, along with information about VA resources.30 While these tools allow users to assess their well-being in privacy, they do not offer the support and interventions that face-to-face screening can include.

Following Henry’s confirmed diagnosis of AD, his NP screened him for depression using the Geriatric Depression Scale and prescribed an antidepressant. She recommended that he take donepezil in the hope of slowing the progression of memory loss in the early to middle stages of the disease. She also screened his wife for her level of caregiver stress using the Zarit Burden Interview, shortened version, and referred her to a caregiver support group, informing her of respite services, including a supportive day program offered at the local Council on Aging. She also referred Henry to a memory loss support group in the community. Despite the available support, the stress in their life was palpable.

Continue for interventions >>

Interventions

Assessing caregiver challenges is only half the task of seeking to improve their lives. The next step is to provide advice and referral for supportive services including structured, valid, and reliable interventions. Structured support groups have been studied locally, nationally, and internationally.26,31,32 Burns and colleagues developed a study to test two 24-month primary care interventions for caregivers of those with AD, focused on alleviating caregivers' distress.33 In this randomized clinical trial, subjects were assigned to one of two groups: one received behavior management alone and the other added stress coping to the behavior management. Those who received only behavior management had worse outcomes for general well-being and depression. The researchers concluded that “brief primary care interventions may be effective in reducing caregiver distress and burden in the long-term.” This study underscores the need for a multifaceted approach to supporting caregivers in their complex and demanding role.

For depression

Depression is a common caregiver complaint; however, measuring incidence and prevalence of mental health issues is a challenge. Studies evaluating the effectiveness of interventions have had mixed results. The REACH II study showed that although caregivers do not usually meet criteria for clinical depression, they nonetheless experience depressive symptoms.34 But, although depression is the most widely studied health consequence of being a caregiver for someone with AD,35 experts report that there is little consistent evidence about the effectiveness of caregiver interventions.

A prospective single-blind randomized controlled trial with a three-month follow-up evaluated whether a cognitive–behavioral family intervention, consisting of education, stress management, and coping skills training, was effective in reducing the burden of care among caregivers of persons with AD.36 Caregiver burden was assessed at pretreatment, posttreatment (nine months after trial entry), and three-month follow-up (12 months after trial entry), using measures of psychological distress and depression and general health. The results showed that the intervention resulted in a significant reduction in distress and depression for caregivers and had a positive effect on modifying patient behaviors. Unfortunately, the intervention is lengthy and requires special training for the interventionist.

A study by Chu and colleagues explored providing a 12-week structured support group to Taiwanese caregivers of those with dementia and found that the support group reduced caregivers’ depression but did not have an effect on burden of care.37 Two other studies showed that support groups have a significant effect on depression and decrease caregiver burden and bother.38,39 Another study of spouses of persons with AD (n = 406) randomly assigned them to either a support and counseling intervention (comprised of six counseling sessions followed by a support group) or to a control group that received routine care.40 The authors assessed all participants before and after the intervention using the Geriatric Depression Scale and found significantly fewer symptoms of depression in the intervention group; these effects were sustained for 3.1 years postintervention. They also found that only group interventions based on psychoeducational theory had a positive effect on depression of caregivers. In a subsequent analysis, the researchers concluded that additional studies of psychosocial interventions for caregivers are warranted and should incorporate biological measures of physical health outcomes.41

Lavretsky, Siddarth, and Irwin conducted the first randomized placebo-controlled double-blind trial of the use of an antidepressant to reduce depression and improve resilience and quality of life among caregivers of persons with dementia.42 Their study demonstrated the efficacy of antidepressant therapy for caregiver depression: 86% of caregivers in the intervention group achieved remission, compared to 44% in the placebo group. Caregivers treated with antidepressants reported reduced anxiety, improved resilience, and decreased burden and stress. The authors also found that the level of depression and burden correlate to the severity of the care recipient’s dementia, related disability, and behavioral problems.42 However, these findings are limited due to the study’s small sample size (n = 28).

Elliott and colleagues report that depression serves a mediating function between the health of caregivers and their experience of burden.38Mediating variables play an important role in governing the relationship between caregiver burden and the health of the caregiver, while moderating variables change the effect between them when increased or decreased. In the first case, caregiver education would likely mediate burden of care; in the second, caregiver sleep (or lack thereof) would moderate the impact of caregiving on depression.

For caregiver burden

Three areas that cause burden for caregivers are activities of daily living, such as eating, bathing, and toileting; instrumental activities of daily living, encompassing shopping, food preparation, and financial management; and behavior and safety, including falls, fires, and driving.43 Caregivers experience physical symptoms, depression, and feelings of burden when faced with a greater number of tasks, more problematic behaviors, and/or more family disagreements.44

The concept of caregiver burden is the focus of many studies, all of them seeking answers for how best to support caregivers caring for a loved one with AD.37,43,45,46 In a multicenter prospective randomized study conducted in 11 hospital and nonhospital psychiatric outpatient clinics in southern Europe (N = 115), the intervention group participated in eight individual sessions over four months that focused on learning strategies for managing AD patient care.46 Data were collected on caregiver stress, quality of life, and perceived health to determine the impact on caregiver burden. The intervention was found to minimize caregiver burden as measured by the ZBI.

Lai and Thomson evaluated a random sample of family caregivers (n = 340) and concluded that providing tangible services and resources should be the first step in reducing burden of care. They report that caregivers’ perceived adequacy of support services predicts caregiver burden. They noted that emotional support results in only marginal benefits.45 Other studies have concurred with the finding that support groups provide emotional support, information, and problem-solving skills to caregivers but do not reduce caregiver burden.31

For caregivers of those with dementia, the strongest predictor of distress is care recipients’ problem behaviors.26 Some theorize that the distress that caregivers experience has multiple components, including belligerence, lack of cooperation, oppositional behaviors, and disruption of sleep patterns of the care recipient.13 Support groups should address behavioral interventions that caregivers can use when faced with the challenging behaviors that often concur with neurocognitive disorders, including confusion, wandering, agitation, crying, swearing, and combativeness.

Caregivers may experience increased stress as their loved one’s dementia progresses. The New York University (NYU) Caregiver Intervention is a long-running randomized controlled study of counseling and support interventions for caregivers of spouses with dementia, conducted by the NYU School of Medicine. Among the array of published analyses of data from this study was a trial reporting that counseling and support interventions reduced the rate of nursing home placement by 28.3%, compared with usual care, and delayed nursing home placement; 61.2% of this delay was attributed to social support, response to patient behaviors, and reduced depression.47 Comprehensive counseling and support provided during the progression of AD patients transitioning to institutionalization can be beneficial to spouses and may translate more broadly to caregivers in general.48

Equipping caregivers to manage the most difficult aspect of their role should be a priority. Many towns and cities offer day programs for those with memory disorders, allowing for respite for caregivers. Councils on aging are a great resource for service information and specialized programs. For those who meet the income guidelines, there may even be financial support for family caregivers. To seek out services, contact the national Alzheimer’s Association (Alz.org) or a local branch. For information on behavioral interventions, Caregiver.org has many available resources on a variety of topics. (Additional resources are listed in “Caregiving Resources.”)

Continue for caregiver stress and self-care >>

Caregiver stress and SELF-CARE

Primary care providers can be instrumental in not only offering referral to services to reduce caregiver stress but also encouraging self-care behaviors for caregivers. They have the opportunity, early on, to anticipate the stresses that caregivers may experience as their loved one’s disease progresses and to provide helpful referral for services (including psychotherapy and support groups), information, and support to preventively address functional ability and self-care behaviors.

The relationship between caregiver stress and self-care behavior has been widely studied. Using the Caregiving Hassles Scale, Kinney and Stephens examined the mediating function of the relationship between caregiving stress and self-care behavior. They found caregiver stress to correlate to self-rated health at a statistically significant level (r = .30, P = .003).13 On a positive note, the investigators also found that the more symptoms family members reported (depression, poor health), the more self-care behaviors they used.

Lu and Wykle also used the Caregiving Hassles Scale in their correlational crossfunctional study. Caregivers (n = 99) were assessed for the mediating function of the relationship between caregiving stress and self-care behavior in response to symptoms.49 Those who reported higher levels of caregiving stress also reported poorer self-rated health, poorer physical function, high levels of depressed mood, and more self-care behaviors at a statistically significant level (r =.30, P = .003, Cronbach’s alpha = .95). The researchers determined that depressed mood was a strong mediator between caregiver stress and response to the symptoms with self-care behaviors.

Unsteady on his feet, Henry became a fall risk. His growing confusion and cognitive decline led to increased depression and agitation, which reduced his socialization and physical activity. Over time, this resulted in a disturbing chain of events, including urinary tract infections, hospitalization, and behavior changes that were upsetting to his wife and children as well as to Henry. Joann was not sleeping well and contracted a cold that turned into pneumonia, leading to a hospitalization. Through all of this, Joann knew that she could call Henry’s NP for advice and support. She found solace in knowing that the caregiver support group she attended regularly would always be there to encourage and inform her and that Henry’s support group would not only give her respite as a caregiver but also provide Henry with cognitive stimulation shown to enhance the well-being of those experiencing memory loss. These groups soon became her lifeline. Without vital early screenings, this family would not have adequately managed the difficulties brought on by Henry’s unexpected diagnosis.

Continue for summary and conclusions >>

Summary and conclusions

Extensive research on caregivers has focused on depression, burden of care, and self-care issues, with mixed findings. Gottlieb and colleagues report that caregivers struggle with the “apparent sadness, listlessness, and vegetative behavior” of their loved one struggling with AD.35 Primary care providers are in a pivotal position to improve caregivers’ health status using reliable and valid assessment tools and offerring referral to services that have been shown to help caregivers in their complex and challenging role.

Support groups, assistance with behavioral interventions, information about the disease process and effective interventions, medication for clinical depression, respite and day programs for persons with neurocognitive disorders, and encouragement of self-care all reduce caregiver stress. Offering effective interventions can improve the physical and mental health of burdened caregivers and positively impact the lives of their loved ones.

Given the growing number of caregivers and the significant effect of caregiving on their health, staying alert should be a priority in all practices. Simply adding two questions to those we regularly ask—Do you care for a loved one struggling with memory loss? How many hours a week do you provide care?—can illuminate the challenges caregivers face, so we can monitor their health status appropriately.

CE/CME No: CR-1606

PROGRAM OVERVIEW

Earn credit by reading this article and successfully completing the posttest and evaluation. Successful completion is defined as a cumulative score of at least 70% correct.

EDUCATIONAL OBJECTIVES

• Describe the adverse consequences that caregivers of persons with Alzheimer disease or other dementias commonly experience.

• Identify reliable and validated tools in the public domain available for use in primary care settings to assess a caregiver's well-being.

• List interventions that are known to support and improve the lives of caregivers seeking care.

• Discuss the impact of support groups on depression and burden of care experienced by caregivers.

• Define the role of primary care providers in reducing the negative aspects of caregiving.

FACULTY

Nancy Langman is a mental health and public health nurse practitioner on Martha’s Vineyard and an Adjunct Clinical Instructor at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

The author has no financial relationships to disclose.

ACCREDITATION STATEMENT

This program has been reviewed and is approved for a maximum of 1.0 hour of American Academy of Physician Assistants (AAPA) Category 1 CME credit by the Physician Assistant Review Panel. [NPs: Both ANCC and the AANP Certification Program recognize AAPA as an approved provider of Category 1 credit.] Approval is valid for one year from the issue date of June 2016.

Article begins on next page >>

Caregivers, mostly family and friends, play an important role in the complex care of persons with Alzheimer disease and other dementias. Primary care providers are uniquely positioned to assess for the negative consequences of caregiving, including depression, anxiety, and caregivers' failure to care for their own health needs. This article provides you with reliable, valid screening tools and recommendations for evidence-based interventions to increase the caregiver’s and patient’s quality of life and care.

Henry, a retired health care administrator, received a diagnosis of Alzheimer disease in his early 80s. Given his career experience, he knew where this disease might take him. His wife, Joann, worked in admissions in a nursing home prior to retirement and was equally informed of the course of the disease. They were among the more fortunate ones struggling with this life-changing diagnosis, in that they had a great primary care provider, access to some of the best neuropsychologists and neurologists in the country, financial stability, and adult children nearby.

Caregivers are a rapidly growing segment of the system of care in the United States, with more than 15 million providing care for those with Alzheimer disease (AD) and other dementias, according to the Alzheimer’s Association.1 Lack of training and support puts caregivers at risk for depression, anxiety, and failure to take care of their own health.2

The incidence and prevalence of dementia continue to increase as the population ages, placing an enormous emotional, physical, and economic burden on caregivers as well as families and society. Given our rapidly growing elderly population and the important role caregivers play, providing evidence-based care and support for caregivers of dementia patients should be a priority for primary care providers.3 Progress in this area requires primary care practitioners to take a lead role in addressing the complex issues that adversely affect caregivers and their loved ones.3 Nurse practitioners (NPs) and physician assistants (PAs) are in a pivotal position to implement caregiver screening and provide referrals to evidence-based interventions.

Who are the caregivers?

Caregivers in the US are predominantly women, and they provide 75% to 80% of long-term care in the community.4 They are largely untrained, unsupervised, unpaid, and undersupported in our society. There are many faces of caregivers: elderly spouses who themselves have health care challenges; adult children, often referred to as the “sandwich generation” as they care for their own families as well as their aging parents; nieces, nephews, and other relatives who find themselves in the position of being the only family left to care for a loved one; and paid caregivers, who also experience the stress of caregiving. Caregivers face many challenges that create both psychological and physical stress, as they are increasingly expected to provide more demanding and complex care, including medication management.4

The MetLife Mature Market Institute reports that 20% of working female caregivers older than 50 experience depression, compared to 8% of peers who are not caregivers.5 Depression among caregivers is well documented, with evidence showing that clinically significant symptoms of depression occur in 40% to 70% of caregivers and that 25% to 50% of these caregivers meet criteria for major depression.6

Continue for assessment tools >>

Assessment Tools

Assessment tools are commonly used to screen for known negative effects of caregiving and to monitor these effects following targeted interventions. Many caregiver assessment tools exist. According to the Family Caregiver Alliance’s Selected Caregiver Assessment Measures, recent efforts have focused on revising available tools to make them shorter and easier to use.7 Newer assessment models attempted to blend content areas (depression, burden, health behaviors, and quality of life) to establish a single screening instrument, in contrast to the stand-alone tools that measure only one domain.8

It is important to select an assessment tool that is easy to administer, reliable and valid, and in the public domain.9-17 In its 2002 consensus project, the Family Caregiver Alliance recommended that assessments be multidimensional in approach, periodically updated, and reflective of culturally competent practice.18 In addition, they believe that those doing the assessments should have relevant training on the role of caregivers and the impact of caregiving.

The Caregiver Assessment Grid was developed by the Michigan Dementia Coalition following a review of 19 scales that measure caregiver burden, stress, quality of life, memory, behavior, and perceptions of caregiving tasks (among others).19 Tools range from simple to complex, with some having Yes or No answers and others using four- or five-point Likert scales. Tools listed in the Caregiver Assessment Grid that meet the criteria for brevity and are in the public domain are discussed here.

The Zarit Burden Interview (ZBI) was initially a 29-item tool that was reduced first to 22 items and then further to 12 items, with a brief screening version containing only four items.10,20 Correlations between the reduced-length versions were .92 to .97 for the short version and .83 to .93 for the screening version.7 The Zarit screening version has a sensitivity of 98.5% and a specificity of 94.7%.10 The ZBI is frequently applied to assess burden, has been cited in many studies, and has been validated for use in other languages.21 This interview tool measures subjective burden, distress, perceptions of social and physical health, financial and emotional burden, and relationship with care recipient. The ZBI has been embedded in other blended assessment tools; for example, it is part of the California Caregiver Resource Centers Uniform Assessment Tool.19

The Pearlin Caregivers’ Stress Scales are based on a conceptual model of the Alzheimer’s Caregiver Stress tool, an eight-item scale developed by the Alzheimer’s Association that links “yes” answers to helpful websites.22 This 15-item instrument addresses cognitive status, problem behaviors, overload, relational deprivation, family conflict, job/caregiving conflict, and economic strain, among others.22

The American Medical Association (AMA) published an 18-item caregiver assessment tool for health care professionals in 2002, encouraging them to identify the needs of caregivers. This tool includes 16 Yes or No questions and two global scale items.19,23

The Risk Appraisal Measure (RAM) developed by Czaja et al is a 16-item assessment that takes 5 to 7 minutes to administer and identifies risk areas for caregivers. This instrument explores six domains of caregiver risk that are potentially amenable to intervention: depression, burden, self-care and health behaviors, social support, safety, and patient problem behaviors. The RAM was developed and validated using data from REACH II (Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health)11 in a study involving 642 participants (219 white; 211 black; 212 Hispanic).11 The authors reported acceptable concurrent validity and internal consistency for the entire scale for the overall sample (Cronbach alpha = .65) and across racial and ethnic groups.11 The authors acknowledge that the Cronbach alpha (a measure of internal consistency, or how closely related a set of items are as a group) is relatively low but explain that this is expected due to the six distinct domains the instrument attempts to measure. The findings from this study highlight the challenge of maintaining reliability and validity in blended screening tools.

The Geriatric Depression Scale (GDS) is a broadly used, well-known tool that has been used extensively with the elderly population.24 The GDS has both a long (30 questions) and short (15 questions) version. In the shorter version, five of the Yes or No questions indicate depression if answered negatively and 10 indicate depression if answered positively. The long and short forms were compared in a validation study and found to be successful in differentiating depressed from nondepressed adults (r = .84, P < .001).25

The Center for Epidemiology Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) is a 20-item self-report scale that takes 5 minutes to administer and measures depressive feelings and behaviors over the previous week.16 It is commonly used to assess depression in caregivers.26 Matschinger and colleagues have expressed concerns about the CES-D being administered to caregivers, many of whom are elderly, because the questions in this instrument are oppositely worded: One part asserts and the other denies the content to avoid a tendency for respondents to give positive answers to questions (known as acquiescence).27 These researchers raise the concern that opposite wording may affect the reliability of the scale and recommend against its use in elderly persons.

The Caregiver Burden Scale, adapted version from the Family Practice Notebook, is a 22-item version of the Caregiver Burden Interview.28 A 12-item version was developed by Bèdard et al, along with a four-question screening version.10

There are several easily accessible online self-assessment tools. The AMA Caregiver Self-Assessment is self-scored and offers help interpreting the scores, suggestions for next steps, and resource information.23 The Caregiver Stress Self-assessment offered by Mass.gov is a modified version of Dr. Steven Zarit’s work and is also self-scored.29 The Veterans Administration (VA) has a more complex Self-Assessment Worksheet that focuses on roles and responsibilities as well as stress; a list of “next step” actions is offered, along with information about VA resources.30 While these tools allow users to assess their well-being in privacy, they do not offer the support and interventions that face-to-face screening can include.

Following Henry’s confirmed diagnosis of AD, his NP screened him for depression using the Geriatric Depression Scale and prescribed an antidepressant. She recommended that he take donepezil in the hope of slowing the progression of memory loss in the early to middle stages of the disease. She also screened his wife for her level of caregiver stress using the Zarit Burden Interview, shortened version, and referred her to a caregiver support group, informing her of respite services, including a supportive day program offered at the local Council on Aging. She also referred Henry to a memory loss support group in the community. Despite the available support, the stress in their life was palpable.

Continue for interventions >>

Interventions

Assessing caregiver challenges is only half the task of seeking to improve their lives. The next step is to provide advice and referral for supportive services including structured, valid, and reliable interventions. Structured support groups have been studied locally, nationally, and internationally.26,31,32 Burns and colleagues developed a study to test two 24-month primary care interventions for caregivers of those with AD, focused on alleviating caregivers' distress.33 In this randomized clinical trial, subjects were assigned to one of two groups: one received behavior management alone and the other added stress coping to the behavior management. Those who received only behavior management had worse outcomes for general well-being and depression. The researchers concluded that “brief primary care interventions may be effective in reducing caregiver distress and burden in the long-term.” This study underscores the need for a multifaceted approach to supporting caregivers in their complex and demanding role.

For depression

Depression is a common caregiver complaint; however, measuring incidence and prevalence of mental health issues is a challenge. Studies evaluating the effectiveness of interventions have had mixed results. The REACH II study showed that although caregivers do not usually meet criteria for clinical depression, they nonetheless experience depressive symptoms.34 But, although depression is the most widely studied health consequence of being a caregiver for someone with AD,35 experts report that there is little consistent evidence about the effectiveness of caregiver interventions.

A prospective single-blind randomized controlled trial with a three-month follow-up evaluated whether a cognitive–behavioral family intervention, consisting of education, stress management, and coping skills training, was effective in reducing the burden of care among caregivers of persons with AD.36 Caregiver burden was assessed at pretreatment, posttreatment (nine months after trial entry), and three-month follow-up (12 months after trial entry), using measures of psychological distress and depression and general health. The results showed that the intervention resulted in a significant reduction in distress and depression for caregivers and had a positive effect on modifying patient behaviors. Unfortunately, the intervention is lengthy and requires special training for the interventionist.

A study by Chu and colleagues explored providing a 12-week structured support group to Taiwanese caregivers of those with dementia and found that the support group reduced caregivers’ depression but did not have an effect on burden of care.37 Two other studies showed that support groups have a significant effect on depression and decrease caregiver burden and bother.38,39 Another study of spouses of persons with AD (n = 406) randomly assigned them to either a support and counseling intervention (comprised of six counseling sessions followed by a support group) or to a control group that received routine care.40 The authors assessed all participants before and after the intervention using the Geriatric Depression Scale and found significantly fewer symptoms of depression in the intervention group; these effects were sustained for 3.1 years postintervention. They also found that only group interventions based on psychoeducational theory had a positive effect on depression of caregivers. In a subsequent analysis, the researchers concluded that additional studies of psychosocial interventions for caregivers are warranted and should incorporate biological measures of physical health outcomes.41

Lavretsky, Siddarth, and Irwin conducted the first randomized placebo-controlled double-blind trial of the use of an antidepressant to reduce depression and improve resilience and quality of life among caregivers of persons with dementia.42 Their study demonstrated the efficacy of antidepressant therapy for caregiver depression: 86% of caregivers in the intervention group achieved remission, compared to 44% in the placebo group. Caregivers treated with antidepressants reported reduced anxiety, improved resilience, and decreased burden and stress. The authors also found that the level of depression and burden correlate to the severity of the care recipient’s dementia, related disability, and behavioral problems.42 However, these findings are limited due to the study’s small sample size (n = 28).

Elliott and colleagues report that depression serves a mediating function between the health of caregivers and their experience of burden.38Mediating variables play an important role in governing the relationship between caregiver burden and the health of the caregiver, while moderating variables change the effect between them when increased or decreased. In the first case, caregiver education would likely mediate burden of care; in the second, caregiver sleep (or lack thereof) would moderate the impact of caregiving on depression.

For caregiver burden

Three areas that cause burden for caregivers are activities of daily living, such as eating, bathing, and toileting; instrumental activities of daily living, encompassing shopping, food preparation, and financial management; and behavior and safety, including falls, fires, and driving.43 Caregivers experience physical symptoms, depression, and feelings of burden when faced with a greater number of tasks, more problematic behaviors, and/or more family disagreements.44

The concept of caregiver burden is the focus of many studies, all of them seeking answers for how best to support caregivers caring for a loved one with AD.37,43,45,46 In a multicenter prospective randomized study conducted in 11 hospital and nonhospital psychiatric outpatient clinics in southern Europe (N = 115), the intervention group participated in eight individual sessions over four months that focused on learning strategies for managing AD patient care.46 Data were collected on caregiver stress, quality of life, and perceived health to determine the impact on caregiver burden. The intervention was found to minimize caregiver burden as measured by the ZBI.