User login

Introducing Point-Counterpoint Perspectives in the Journal of Hospital Medicine

Providing high-quality, efficient, and evidence-based healthcare is a complicated and complex process. The right approach or path forward is not always clear. In medicine, decision-making inherently involves uncertainty; evidence may be lacking, or values or context may differ, and thus, reasonable clinicians may choose to make different decisions based on the same data.

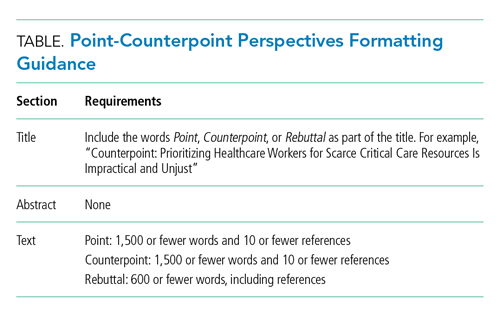

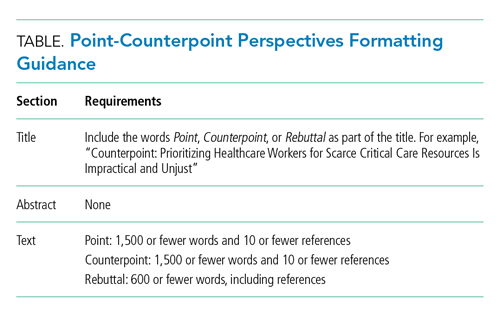

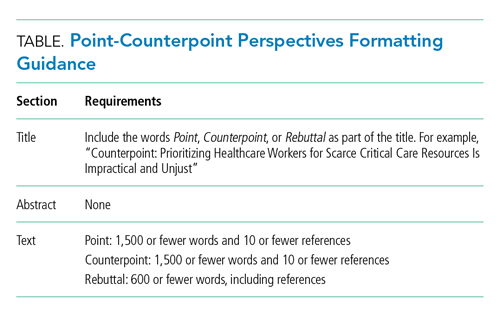

In this spirit of fostering education and healthy debate to improve understanding of challenges relevant to the field of hospital medicine, we are pleased to introduce our Point-Counterpoint series within the Perspectives in Hospital Medicine section of the journal. Point-Counterpoint Perspectives presents a debate by content experts. Each provides an interpretation of evidence regarding patient management or other controversial issues relating to hospital-based care. The format consists of an overview of the topic with an original point followed by a counterpoint response and, finally, a rebuttal (Table). We ask contributors to be as outspoken in their points and counterpoints as the evidence allows in order to fully elaborate the questions and uncertainties that may otherwise be familiar only to experts in the field or to those in other disciplines.

Our inaugural point-counterpoint articles address whether healthcare workers should receive priority for scarce drugs and therapies during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The intermittent shortage of medical supplies and protective equipment has made it not only difficult but also at times dangerous for healthcare workers to care for infected patients.1 The risks of developing COVID-19 and fear of transmitting it to loved ones has led to stress, fatigue, and burnout among healthcare workers, leading some to quit and even attempt suicide. The downstream effects of this stress may adversely affect patients and exacerbate staffing challenges in an already taxed healthcare system.2 Do we have a special obligation to those on the front lines? We are grateful to Drs Kirk R Daffner, Armand Antommaria, and Ndidi I Unaka, for addressing this controversial topic.3-5

1. Lagu T, Artenstein AW, Werner RM. Fool me twice: the role for hospitals and health systems in fixing the broken PPE supply chain. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):570-571. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3489

2. Ali SS. Why some nurses have quit during the coronavirus pandemic. NBC News. May,10, 2020. Accessed January 18, 2021. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/why-some-nurses-have-quit-during-coronavirus-pandemic-n1201796

3. Daffner KR. Point: healthcare providers should receive treatment priority during a pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):180-181. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3596

4. Antommaria A, Unaka NI. Counterpoint: prioritizing healthcare workers for scarce critical resources is impractical and unjust. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):182-183. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3597

5. Daffner KR. Rebuttal: accounting for the community’s reciprocal obligations during a pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):184. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3600

Providing high-quality, efficient, and evidence-based healthcare is a complicated and complex process. The right approach or path forward is not always clear. In medicine, decision-making inherently involves uncertainty; evidence may be lacking, or values or context may differ, and thus, reasonable clinicians may choose to make different decisions based on the same data.

In this spirit of fostering education and healthy debate to improve understanding of challenges relevant to the field of hospital medicine, we are pleased to introduce our Point-Counterpoint series within the Perspectives in Hospital Medicine section of the journal. Point-Counterpoint Perspectives presents a debate by content experts. Each provides an interpretation of evidence regarding patient management or other controversial issues relating to hospital-based care. The format consists of an overview of the topic with an original point followed by a counterpoint response and, finally, a rebuttal (Table). We ask contributors to be as outspoken in their points and counterpoints as the evidence allows in order to fully elaborate the questions and uncertainties that may otherwise be familiar only to experts in the field or to those in other disciplines.

Our inaugural point-counterpoint articles address whether healthcare workers should receive priority for scarce drugs and therapies during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The intermittent shortage of medical supplies and protective equipment has made it not only difficult but also at times dangerous for healthcare workers to care for infected patients.1 The risks of developing COVID-19 and fear of transmitting it to loved ones has led to stress, fatigue, and burnout among healthcare workers, leading some to quit and even attempt suicide. The downstream effects of this stress may adversely affect patients and exacerbate staffing challenges in an already taxed healthcare system.2 Do we have a special obligation to those on the front lines? We are grateful to Drs Kirk R Daffner, Armand Antommaria, and Ndidi I Unaka, for addressing this controversial topic.3-5

Providing high-quality, efficient, and evidence-based healthcare is a complicated and complex process. The right approach or path forward is not always clear. In medicine, decision-making inherently involves uncertainty; evidence may be lacking, or values or context may differ, and thus, reasonable clinicians may choose to make different decisions based on the same data.

In this spirit of fostering education and healthy debate to improve understanding of challenges relevant to the field of hospital medicine, we are pleased to introduce our Point-Counterpoint series within the Perspectives in Hospital Medicine section of the journal. Point-Counterpoint Perspectives presents a debate by content experts. Each provides an interpretation of evidence regarding patient management or other controversial issues relating to hospital-based care. The format consists of an overview of the topic with an original point followed by a counterpoint response and, finally, a rebuttal (Table). We ask contributors to be as outspoken in their points and counterpoints as the evidence allows in order to fully elaborate the questions and uncertainties that may otherwise be familiar only to experts in the field or to those in other disciplines.

Our inaugural point-counterpoint articles address whether healthcare workers should receive priority for scarce drugs and therapies during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. The intermittent shortage of medical supplies and protective equipment has made it not only difficult but also at times dangerous for healthcare workers to care for infected patients.1 The risks of developing COVID-19 and fear of transmitting it to loved ones has led to stress, fatigue, and burnout among healthcare workers, leading some to quit and even attempt suicide. The downstream effects of this stress may adversely affect patients and exacerbate staffing challenges in an already taxed healthcare system.2 Do we have a special obligation to those on the front lines? We are grateful to Drs Kirk R Daffner, Armand Antommaria, and Ndidi I Unaka, for addressing this controversial topic.3-5

1. Lagu T, Artenstein AW, Werner RM. Fool me twice: the role for hospitals and health systems in fixing the broken PPE supply chain. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):570-571. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3489

2. Ali SS. Why some nurses have quit during the coronavirus pandemic. NBC News. May,10, 2020. Accessed January 18, 2021. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/why-some-nurses-have-quit-during-coronavirus-pandemic-n1201796

3. Daffner KR. Point: healthcare providers should receive treatment priority during a pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):180-181. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3596

4. Antommaria A, Unaka NI. Counterpoint: prioritizing healthcare workers for scarce critical resources is impractical and unjust. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):182-183. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3597

5. Daffner KR. Rebuttal: accounting for the community’s reciprocal obligations during a pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):184. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3600

1. Lagu T, Artenstein AW, Werner RM. Fool me twice: the role for hospitals and health systems in fixing the broken PPE supply chain. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(9):570-571. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3489

2. Ali SS. Why some nurses have quit during the coronavirus pandemic. NBC News. May,10, 2020. Accessed January 18, 2021. https://www.nbcnews.com/news/us-news/why-some-nurses-have-quit-during-coronavirus-pandemic-n1201796

3. Daffner KR. Point: healthcare providers should receive treatment priority during a pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):180-181. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3596

4. Antommaria A, Unaka NI. Counterpoint: prioritizing healthcare workers for scarce critical resources is impractical and unjust. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):182-183. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3597

5. Daffner KR. Rebuttal: accounting for the community’s reciprocal obligations during a pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2021;16(3):184. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3600

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

The Light at the End of the Tunnel: Reflections on 2020 and Hopes for 2021

We enter the new year still in the midst of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and remain humbled by its impact. It is remarkable how much, and how little, has changed. Hospitalists in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic were struggling. We were caring for patients who were suffering and dying from a new and mysterious disease. There weren’t enough tests (or, if there were tests, there weren’t swabs).1 We were using protocols for managing respiratory failure that, we would learn later, may not have been the best for improving outcomes. Rumors of unproven therapies came from everywhere: our patients, our colleagues, and even the highest realms of the federal government. We also knew very little about how best to protect ourselves. In many cases, we did not have enough personal protective equipment (PPE). There were no face shields, or “zoom rounds,” or even awareness that we probably shouldn’t sit in the tiny conference room (maskless) discussing patients with the large team of doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists, and social workers.

Perhaps worst of all, we were haunted. We were alarmed by the large numbers of young patients who were ill, and our elderly patients, many of whom we knew and had cared for many times, had suddenly just stopped showing up.2 In our free moments, we worried about them; maybe they were afraid to come to the hospital, maybe they were home sick with COVID-19, or maybe they had died alone. And children, initially thought to be spared the most serious consequences of COVID-19, started coming to the hospital with a rare but severe new COVID-19-associated complication, termed multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). We had to learn to manage yet another manifestation of COVID-19, largely through trial and error.

And, of course, clinical care was only one of our many responsibilities. We were also busy hunting for ventilators, setting up makeshift medical wards and intensive care units, revamping medical education, and scouring the literature for any information to help guide patient care. We worried about getting sick ourselves and bringing the disease home to our families. Our impatience grew as day after day there was no (and still is no) coordinated federal response.

A glimmer of hope slowly emerged. Our colleagues designed and rapidly evaluated respiratory protocols and provided early evidence about the strategies (eg, proning) that were associated with improved outcomes.3 Researchers began to generate knowledge and move us beyond rumors regarding potential therapies. We cheered as our administrators concocted unusual strategies to remedy the PPE and testing shortages.4

At the Journal of Hospital Medicine, we were faced with another challenge: How would we describe the chaos and the challenges of being a physician during the COVID-19 era? How would we document the way our colleagues were rising to the challenge and identifying opportunities to rethink hospital care in the United States?

In April, we began to receive a deluge of personal essays from frontline physicians about their experiences with COVID-19. Generally, medical journals publish and disseminate original, high-impact research. Personal essays rarely fit this model. Given the unprecedented circumstances, however, we decided these essays could help chronicle an important moment in medical history. In our May 2020 issue, we published only these essays. We continue to publish them online almost daily.

Some of the essays described how the healthcare system—previously thought to be hyperspecialized, profit-driven, and resistant to change—pivoted within days, as hospitalist physicians trained other physicians to “unspecialize” and pediatricians began to care for adults in an otherwise overwhelmed hospital system.5,6 Another essay focused on the need to trust that medical students who had graduated early would be able to function as physicians.7 And yet another essay expressed concern about the widespread use of unproven therapies in hospitalized patients. “Even in times of global pandemic, we need to consider potential harms and adverse consequences of novel treatments,’’ the physicians wrote. “Sometimes inaction is preferable to action.”8

Several essays reflected on the impact of the pandemic on healthcare disparities, suggesting that the pandemic had made (the well-known but often ignored) differences in health outcomes between White patients and racial minorities more obvious. Still another essay reflected on the intersection between structural racism, poor access to care, and interpersonal racism, describing the grief caused by losses of Black lives to both police violence and COVID-19.9

There also were personal stories of hardship and survival. One hospitalist physician with asthma described coughing as ``the new leprosy.”10 She wrote, “This is a particularly unpropitious time in history to be a Chinese-American doctor who can’t stop coughing.”

There were drawbacks to our decision to focus on personal essays. Although it was clear even before the pandemic, COVID-19 has highlighted that a path for quick dissemination of original peer-reviewed research is needed. If existing medical journals do not fill that role, websites that publish and disseminate non–peer-reviewed work (aka, “preprints”) will become the preferred method for distribution of high-impact, timely original research.11 The journal’s pivot to reviewing and publishing personal essays may have kept us from improving our approach to rapid peer review and dissemination. In those early days, however, there was no peer-reviewed work to publish, but there was an intense desire (from our members and physicians generally) for information and stories from the front lines. In a way, the essays we published were early “case reports,” that hypothesized about how we might rethink healthcare delivery in pandemic conditions.

Furthermore, our decision to solicit and publish personal essays addressing shortcomings of the federal response and consequences of the pandemic meant that the Journal of Hospital Medicine became part of the pandemic’s political discourse. As editors, we have historically kept the journal away from political arguments or endorsements. In this case, however, we decided that even if some of the opinions were political, they were an appropriate response to the widespread anti-science rhetoric endorsed by the current administration. The resultant erosion of trust in public health has undoubtedly contributed to persistence of the pandemic.12 A stance against masks, for example, rejects the recommendations of nearly all scientists in favor of (a selfish and problematic idea of) “self-determination.” Those who proclaim that such a mandate infringes on their personal freedom reject evidence-based recommendations of scientists and disregard public health strategies meant to protect everyone.

As we reflect on the past year, our most important lesson may be that our previous emphasis on publishing high-impact original research likely missed important personal and professional insights, insights that could have changed practice, improved patient experience, and reduced physician burnout. Anecdotes are not scientific evidence, but we have discovered their incredible power to help us learn, empathize, commiserate, and survive. Hospitals learned that they must adapt in the moment, a notion that runs counter to the notoriously slow pace of change in paradigms of healthcare. Hospitalists learned to “find their battle buddies” to ward off isolation and to cherish their teams in the face of overwhelming trauma, an approach requiring empathy, humility, and compassion.13 We won’t soon forget that, when things were most dire, it was stories—not data—that gave us hope. We look forward to 2021 with great optimism. New vaccines and new federal leaders who value and respect science give us hope that the end of the pandemic is in sight. We are indebted to all frontline workers who have transformed care delivery and remained courageous in the face of great personal risk. As a journal, we will continue, as one scientist noted, to use our “platform for advocacy, unabashedly.”14

1. Shuren J, Stenzel T. Covid-19 molecular diagnostic testing - lessons learned. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:e97. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2023830

2. Rosenbaum L. The untold toll - the pandemic’s effects on patients without Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2368-2371. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMms2009984

3. Westafer LM, Elia T, Medarametla V, Lagu T. A transdisciplinary COVID-19 early respiratory intervention protocol: an implementation story. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:372-374. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3456

4. Lagu T, Artenstein AW, Werner RM. Fool me twice: the role for hospitals and health systems in fixing the broken PPE supply chain. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:570-571. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3489

5. Cram P, Anderson ML, Shaughnessy EE. All hands on deck: learning to “un-specialize” in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:314-315. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3426

6. Biala D, Siegel EJ, Silver L, Schindel B, Smith KM. Deployed: pediatric residents caring for adults during COVID-19’s first wave in New York City. J Hosp Med. 2020; Published ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3527

7. Kinnear B, Kelleher M, Olson AP, Sall D, Schumacher DJ. Developing trust with early medical school graduates during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:367-369. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3463

8. Canfield GS, Schultz JS, Windham S, et al. Empiric therapies for covid-19: destined to fail by ignoring the lessons of history. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:434-436. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3469

9. Manning KD. When grief and crises intersect: perspectives of a Black physician in the time of two pandemics. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:566-567. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3481

10. Chang T. Do I have coronavirus? J Hosp Med. 2020;15:277-278. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3430

11. Guterman EL, Braunstein LZ. Preprints during the COVID-19 pandemic: public health emergencies and medical literature. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:634-636. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3491

12. Udow-Phillips M, Lantz PM. Trust in public health is essential amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:431-433. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3474

13. Hertling M. Ten tips for a crisis: lessons from a soldier. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:275-276. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3424

14. O’Glasser A [@aoglasser]. #JHMChat I also need to readily admit that part of the reason I’m a loyal, enthusiastic @JHospMedicine reader is because [Tweet]. November 16, 2020. Accessed November 28, 2020. https://twitter.com/aoglasser/status/1328529564595720192

We enter the new year still in the midst of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and remain humbled by its impact. It is remarkable how much, and how little, has changed. Hospitalists in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic were struggling. We were caring for patients who were suffering and dying from a new and mysterious disease. There weren’t enough tests (or, if there were tests, there weren’t swabs).1 We were using protocols for managing respiratory failure that, we would learn later, may not have been the best for improving outcomes. Rumors of unproven therapies came from everywhere: our patients, our colleagues, and even the highest realms of the federal government. We also knew very little about how best to protect ourselves. In many cases, we did not have enough personal protective equipment (PPE). There were no face shields, or “zoom rounds,” or even awareness that we probably shouldn’t sit in the tiny conference room (maskless) discussing patients with the large team of doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists, and social workers.

Perhaps worst of all, we were haunted. We were alarmed by the large numbers of young patients who were ill, and our elderly patients, many of whom we knew and had cared for many times, had suddenly just stopped showing up.2 In our free moments, we worried about them; maybe they were afraid to come to the hospital, maybe they were home sick with COVID-19, or maybe they had died alone. And children, initially thought to be spared the most serious consequences of COVID-19, started coming to the hospital with a rare but severe new COVID-19-associated complication, termed multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). We had to learn to manage yet another manifestation of COVID-19, largely through trial and error.

And, of course, clinical care was only one of our many responsibilities. We were also busy hunting for ventilators, setting up makeshift medical wards and intensive care units, revamping medical education, and scouring the literature for any information to help guide patient care. We worried about getting sick ourselves and bringing the disease home to our families. Our impatience grew as day after day there was no (and still is no) coordinated federal response.

A glimmer of hope slowly emerged. Our colleagues designed and rapidly evaluated respiratory protocols and provided early evidence about the strategies (eg, proning) that were associated with improved outcomes.3 Researchers began to generate knowledge and move us beyond rumors regarding potential therapies. We cheered as our administrators concocted unusual strategies to remedy the PPE and testing shortages.4

At the Journal of Hospital Medicine, we were faced with another challenge: How would we describe the chaos and the challenges of being a physician during the COVID-19 era? How would we document the way our colleagues were rising to the challenge and identifying opportunities to rethink hospital care in the United States?

In April, we began to receive a deluge of personal essays from frontline physicians about their experiences with COVID-19. Generally, medical journals publish and disseminate original, high-impact research. Personal essays rarely fit this model. Given the unprecedented circumstances, however, we decided these essays could help chronicle an important moment in medical history. In our May 2020 issue, we published only these essays. We continue to publish them online almost daily.

Some of the essays described how the healthcare system—previously thought to be hyperspecialized, profit-driven, and resistant to change—pivoted within days, as hospitalist physicians trained other physicians to “unspecialize” and pediatricians began to care for adults in an otherwise overwhelmed hospital system.5,6 Another essay focused on the need to trust that medical students who had graduated early would be able to function as physicians.7 And yet another essay expressed concern about the widespread use of unproven therapies in hospitalized patients. “Even in times of global pandemic, we need to consider potential harms and adverse consequences of novel treatments,’’ the physicians wrote. “Sometimes inaction is preferable to action.”8

Several essays reflected on the impact of the pandemic on healthcare disparities, suggesting that the pandemic had made (the well-known but often ignored) differences in health outcomes between White patients and racial minorities more obvious. Still another essay reflected on the intersection between structural racism, poor access to care, and interpersonal racism, describing the grief caused by losses of Black lives to both police violence and COVID-19.9

There also were personal stories of hardship and survival. One hospitalist physician with asthma described coughing as ``the new leprosy.”10 She wrote, “This is a particularly unpropitious time in history to be a Chinese-American doctor who can’t stop coughing.”

There were drawbacks to our decision to focus on personal essays. Although it was clear even before the pandemic, COVID-19 has highlighted that a path for quick dissemination of original peer-reviewed research is needed. If existing medical journals do not fill that role, websites that publish and disseminate non–peer-reviewed work (aka, “preprints”) will become the preferred method for distribution of high-impact, timely original research.11 The journal’s pivot to reviewing and publishing personal essays may have kept us from improving our approach to rapid peer review and dissemination. In those early days, however, there was no peer-reviewed work to publish, but there was an intense desire (from our members and physicians generally) for information and stories from the front lines. In a way, the essays we published were early “case reports,” that hypothesized about how we might rethink healthcare delivery in pandemic conditions.

Furthermore, our decision to solicit and publish personal essays addressing shortcomings of the federal response and consequences of the pandemic meant that the Journal of Hospital Medicine became part of the pandemic’s political discourse. As editors, we have historically kept the journal away from political arguments or endorsements. In this case, however, we decided that even if some of the opinions were political, they were an appropriate response to the widespread anti-science rhetoric endorsed by the current administration. The resultant erosion of trust in public health has undoubtedly contributed to persistence of the pandemic.12 A stance against masks, for example, rejects the recommendations of nearly all scientists in favor of (a selfish and problematic idea of) “self-determination.” Those who proclaim that such a mandate infringes on their personal freedom reject evidence-based recommendations of scientists and disregard public health strategies meant to protect everyone.

As we reflect on the past year, our most important lesson may be that our previous emphasis on publishing high-impact original research likely missed important personal and professional insights, insights that could have changed practice, improved patient experience, and reduced physician burnout. Anecdotes are not scientific evidence, but we have discovered their incredible power to help us learn, empathize, commiserate, and survive. Hospitals learned that they must adapt in the moment, a notion that runs counter to the notoriously slow pace of change in paradigms of healthcare. Hospitalists learned to “find their battle buddies” to ward off isolation and to cherish their teams in the face of overwhelming trauma, an approach requiring empathy, humility, and compassion.13 We won’t soon forget that, when things were most dire, it was stories—not data—that gave us hope. We look forward to 2021 with great optimism. New vaccines and new federal leaders who value and respect science give us hope that the end of the pandemic is in sight. We are indebted to all frontline workers who have transformed care delivery and remained courageous in the face of great personal risk. As a journal, we will continue, as one scientist noted, to use our “platform for advocacy, unabashedly.”14

We enter the new year still in the midst of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and remain humbled by its impact. It is remarkable how much, and how little, has changed. Hospitalists in the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic were struggling. We were caring for patients who were suffering and dying from a new and mysterious disease. There weren’t enough tests (or, if there were tests, there weren’t swabs).1 We were using protocols for managing respiratory failure that, we would learn later, may not have been the best for improving outcomes. Rumors of unproven therapies came from everywhere: our patients, our colleagues, and even the highest realms of the federal government. We also knew very little about how best to protect ourselves. In many cases, we did not have enough personal protective equipment (PPE). There were no face shields, or “zoom rounds,” or even awareness that we probably shouldn’t sit in the tiny conference room (maskless) discussing patients with the large team of doctors, nurses, respiratory therapists, and social workers.

Perhaps worst of all, we were haunted. We were alarmed by the large numbers of young patients who were ill, and our elderly patients, many of whom we knew and had cared for many times, had suddenly just stopped showing up.2 In our free moments, we worried about them; maybe they were afraid to come to the hospital, maybe they were home sick with COVID-19, or maybe they had died alone. And children, initially thought to be spared the most serious consequences of COVID-19, started coming to the hospital with a rare but severe new COVID-19-associated complication, termed multisystem inflammatory syndrome in children (MIS-C). We had to learn to manage yet another manifestation of COVID-19, largely through trial and error.

And, of course, clinical care was only one of our many responsibilities. We were also busy hunting for ventilators, setting up makeshift medical wards and intensive care units, revamping medical education, and scouring the literature for any information to help guide patient care. We worried about getting sick ourselves and bringing the disease home to our families. Our impatience grew as day after day there was no (and still is no) coordinated federal response.

A glimmer of hope slowly emerged. Our colleagues designed and rapidly evaluated respiratory protocols and provided early evidence about the strategies (eg, proning) that were associated with improved outcomes.3 Researchers began to generate knowledge and move us beyond rumors regarding potential therapies. We cheered as our administrators concocted unusual strategies to remedy the PPE and testing shortages.4

At the Journal of Hospital Medicine, we were faced with another challenge: How would we describe the chaos and the challenges of being a physician during the COVID-19 era? How would we document the way our colleagues were rising to the challenge and identifying opportunities to rethink hospital care in the United States?

In April, we began to receive a deluge of personal essays from frontline physicians about their experiences with COVID-19. Generally, medical journals publish and disseminate original, high-impact research. Personal essays rarely fit this model. Given the unprecedented circumstances, however, we decided these essays could help chronicle an important moment in medical history. In our May 2020 issue, we published only these essays. We continue to publish them online almost daily.

Some of the essays described how the healthcare system—previously thought to be hyperspecialized, profit-driven, and resistant to change—pivoted within days, as hospitalist physicians trained other physicians to “unspecialize” and pediatricians began to care for adults in an otherwise overwhelmed hospital system.5,6 Another essay focused on the need to trust that medical students who had graduated early would be able to function as physicians.7 And yet another essay expressed concern about the widespread use of unproven therapies in hospitalized patients. “Even in times of global pandemic, we need to consider potential harms and adverse consequences of novel treatments,’’ the physicians wrote. “Sometimes inaction is preferable to action.”8

Several essays reflected on the impact of the pandemic on healthcare disparities, suggesting that the pandemic had made (the well-known but often ignored) differences in health outcomes between White patients and racial minorities more obvious. Still another essay reflected on the intersection between structural racism, poor access to care, and interpersonal racism, describing the grief caused by losses of Black lives to both police violence and COVID-19.9

There also were personal stories of hardship and survival. One hospitalist physician with asthma described coughing as ``the new leprosy.”10 She wrote, “This is a particularly unpropitious time in history to be a Chinese-American doctor who can’t stop coughing.”

There were drawbacks to our decision to focus on personal essays. Although it was clear even before the pandemic, COVID-19 has highlighted that a path for quick dissemination of original peer-reviewed research is needed. If existing medical journals do not fill that role, websites that publish and disseminate non–peer-reviewed work (aka, “preprints”) will become the preferred method for distribution of high-impact, timely original research.11 The journal’s pivot to reviewing and publishing personal essays may have kept us from improving our approach to rapid peer review and dissemination. In those early days, however, there was no peer-reviewed work to publish, but there was an intense desire (from our members and physicians generally) for information and stories from the front lines. In a way, the essays we published were early “case reports,” that hypothesized about how we might rethink healthcare delivery in pandemic conditions.

Furthermore, our decision to solicit and publish personal essays addressing shortcomings of the federal response and consequences of the pandemic meant that the Journal of Hospital Medicine became part of the pandemic’s political discourse. As editors, we have historically kept the journal away from political arguments or endorsements. In this case, however, we decided that even if some of the opinions were political, they were an appropriate response to the widespread anti-science rhetoric endorsed by the current administration. The resultant erosion of trust in public health has undoubtedly contributed to persistence of the pandemic.12 A stance against masks, for example, rejects the recommendations of nearly all scientists in favor of (a selfish and problematic idea of) “self-determination.” Those who proclaim that such a mandate infringes on their personal freedom reject evidence-based recommendations of scientists and disregard public health strategies meant to protect everyone.

As we reflect on the past year, our most important lesson may be that our previous emphasis on publishing high-impact original research likely missed important personal and professional insights, insights that could have changed practice, improved patient experience, and reduced physician burnout. Anecdotes are not scientific evidence, but we have discovered their incredible power to help us learn, empathize, commiserate, and survive. Hospitals learned that they must adapt in the moment, a notion that runs counter to the notoriously slow pace of change in paradigms of healthcare. Hospitalists learned to “find their battle buddies” to ward off isolation and to cherish their teams in the face of overwhelming trauma, an approach requiring empathy, humility, and compassion.13 We won’t soon forget that, when things were most dire, it was stories—not data—that gave us hope. We look forward to 2021 with great optimism. New vaccines and new federal leaders who value and respect science give us hope that the end of the pandemic is in sight. We are indebted to all frontline workers who have transformed care delivery and remained courageous in the face of great personal risk. As a journal, we will continue, as one scientist noted, to use our “platform for advocacy, unabashedly.”14

1. Shuren J, Stenzel T. Covid-19 molecular diagnostic testing - lessons learned. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:e97. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2023830

2. Rosenbaum L. The untold toll - the pandemic’s effects on patients without Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2368-2371. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMms2009984

3. Westafer LM, Elia T, Medarametla V, Lagu T. A transdisciplinary COVID-19 early respiratory intervention protocol: an implementation story. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:372-374. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3456

4. Lagu T, Artenstein AW, Werner RM. Fool me twice: the role for hospitals and health systems in fixing the broken PPE supply chain. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:570-571. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3489

5. Cram P, Anderson ML, Shaughnessy EE. All hands on deck: learning to “un-specialize” in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:314-315. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3426

6. Biala D, Siegel EJ, Silver L, Schindel B, Smith KM. Deployed: pediatric residents caring for adults during COVID-19’s first wave in New York City. J Hosp Med. 2020; Published ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3527

7. Kinnear B, Kelleher M, Olson AP, Sall D, Schumacher DJ. Developing trust with early medical school graduates during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:367-369. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3463

8. Canfield GS, Schultz JS, Windham S, et al. Empiric therapies for covid-19: destined to fail by ignoring the lessons of history. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:434-436. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3469

9. Manning KD. When grief and crises intersect: perspectives of a Black physician in the time of two pandemics. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:566-567. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3481

10. Chang T. Do I have coronavirus? J Hosp Med. 2020;15:277-278. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3430

11. Guterman EL, Braunstein LZ. Preprints during the COVID-19 pandemic: public health emergencies and medical literature. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:634-636. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3491

12. Udow-Phillips M, Lantz PM. Trust in public health is essential amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:431-433. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3474

13. Hertling M. Ten tips for a crisis: lessons from a soldier. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:275-276. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3424

14. O’Glasser A [@aoglasser]. #JHMChat I also need to readily admit that part of the reason I’m a loyal, enthusiastic @JHospMedicine reader is because [Tweet]. November 16, 2020. Accessed November 28, 2020. https://twitter.com/aoglasser/status/1328529564595720192

1. Shuren J, Stenzel T. Covid-19 molecular diagnostic testing - lessons learned. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:e97. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2023830

2. Rosenbaum L. The untold toll - the pandemic’s effects on patients without Covid-19. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:2368-2371. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMms2009984

3. Westafer LM, Elia T, Medarametla V, Lagu T. A transdisciplinary COVID-19 early respiratory intervention protocol: an implementation story. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:372-374. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3456

4. Lagu T, Artenstein AW, Werner RM. Fool me twice: the role for hospitals and health systems in fixing the broken PPE supply chain. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:570-571. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3489

5. Cram P, Anderson ML, Shaughnessy EE. All hands on deck: learning to “un-specialize” in the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:314-315. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3426

6. Biala D, Siegel EJ, Silver L, Schindel B, Smith KM. Deployed: pediatric residents caring for adults during COVID-19’s first wave in New York City. J Hosp Med. 2020; Published ahead of print. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3527

7. Kinnear B, Kelleher M, Olson AP, Sall D, Schumacher DJ. Developing trust with early medical school graduates during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:367-369. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3463

8. Canfield GS, Schultz JS, Windham S, et al. Empiric therapies for covid-19: destined to fail by ignoring the lessons of history. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:434-436. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3469

9. Manning KD. When grief and crises intersect: perspectives of a Black physician in the time of two pandemics. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:566-567. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3481

10. Chang T. Do I have coronavirus? J Hosp Med. 2020;15:277-278. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3430

11. Guterman EL, Braunstein LZ. Preprints during the COVID-19 pandemic: public health emergencies and medical literature. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:634-636. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3491

12. Udow-Phillips M, Lantz PM. Trust in public health is essential amid the COVID-19 pandemic. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:431-433. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3474

13. Hertling M. Ten tips for a crisis: lessons from a soldier. J Hosp Med. 2020;15:275-276. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3424

14. O’Glasser A [@aoglasser]. #JHMChat I also need to readily admit that part of the reason I’m a loyal, enthusiastic @JHospMedicine reader is because [Tweet]. November 16, 2020. Accessed November 28, 2020. https://twitter.com/aoglasser/status/1328529564595720192

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Email: [email protected]; Telephone: 513-636-6222; Twitter: @SamirShahMD.

Rapid Publication, Knowledge Sharing, and Our Responsibility During the COVID-19 Pandemic

The first case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States was identified in Washington state in late January 2020. As of mid-April 2020, the number of US cases has increased to more than 800,000 with over 40,000 deaths. The limited available knowledge to guide medical decision-making combined with rapid progression of the pandemic has resulted in an urgent need to better define clinical, radiologic, and laboratory features of the disease, predictors of disease progression, predominant modes of transmission, and effective treatments. This urgency has led to a flood of manuscript submissions, which strains the scientific vetting process and leads to the spread of medical misinformation and potential for serious harm. As an example, a small observational (noncontrolled) study that used an antimalarial drug to treat COVID-19 patients was touted by several national leaders as proof of its effectiveness, despite substantial methodologic limitations.1,2 While the article has not yet been retracted, the International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, the publishing journal’s society sponsor, subsequently issued a statement that “the article does not meet the Society’s expected standard.”3

With these concerns in mind, we recognize the importance of addressing the current pandemic and identifying areas where we can advance the field responsibly in the face of limited evidence in a rapidly evolving situation. Hospitalists throughout the world are facing unprecedented leadership challenges, navigating ethical stressors, and redesigning their care systems while learning rapidly and adapting nimbly. In this issue, we share leadership strategies, explore ethical challenges and controversies, describe successful practices, and provide personal reflections from a diverse group of hospitalists and leaders. As a journal, we have intentionally avoided rapid publication of articles with substantial methodologic limitations that are unlikely to advance our knowledge of COVID-19 even though such articles may generate substantial media coverage. Different regions of the country are at different stages of the pandemic; some hospitals are experiencing high patient volumes and struggling with shortages of equipment and supplies, while others are weeks away from peak disease activity or have avoided periods of high prevalence altogether. These varied experiences offer an opportunity to share our learnings and perspectives as we wait for more definitive evidence on best management practices. As part of our commitment to our colleagues in healthcare and to the broader scientific community, all Journal of Hospital Medicine articles related to COVID-19 and published during the pandemic will be open access (ie, freely accessible).

1. Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949.

2. Baker P, Rogers K, Enrich D, Haberman M. Trump’s aggressive advocacy of malaria drug for treating coronavirus divides medical community. New York Times. April 6, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/us/politics/coronavirus-trump-malaria-drug.html. Accessed April 13, 2020.

3. International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. Statement on International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents paper. https://www.isac.world/news-and-publications/official-isac-statement. Accessed April 13, 2020.

The first case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States was identified in Washington state in late January 2020. As of mid-April 2020, the number of US cases has increased to more than 800,000 with over 40,000 deaths. The limited available knowledge to guide medical decision-making combined with rapid progression of the pandemic has resulted in an urgent need to better define clinical, radiologic, and laboratory features of the disease, predictors of disease progression, predominant modes of transmission, and effective treatments. This urgency has led to a flood of manuscript submissions, which strains the scientific vetting process and leads to the spread of medical misinformation and potential for serious harm. As an example, a small observational (noncontrolled) study that used an antimalarial drug to treat COVID-19 patients was touted by several national leaders as proof of its effectiveness, despite substantial methodologic limitations.1,2 While the article has not yet been retracted, the International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, the publishing journal’s society sponsor, subsequently issued a statement that “the article does not meet the Society’s expected standard.”3

With these concerns in mind, we recognize the importance of addressing the current pandemic and identifying areas where we can advance the field responsibly in the face of limited evidence in a rapidly evolving situation. Hospitalists throughout the world are facing unprecedented leadership challenges, navigating ethical stressors, and redesigning their care systems while learning rapidly and adapting nimbly. In this issue, we share leadership strategies, explore ethical challenges and controversies, describe successful practices, and provide personal reflections from a diverse group of hospitalists and leaders. As a journal, we have intentionally avoided rapid publication of articles with substantial methodologic limitations that are unlikely to advance our knowledge of COVID-19 even though such articles may generate substantial media coverage. Different regions of the country are at different stages of the pandemic; some hospitals are experiencing high patient volumes and struggling with shortages of equipment and supplies, while others are weeks away from peak disease activity or have avoided periods of high prevalence altogether. These varied experiences offer an opportunity to share our learnings and perspectives as we wait for more definitive evidence on best management practices. As part of our commitment to our colleagues in healthcare and to the broader scientific community, all Journal of Hospital Medicine articles related to COVID-19 and published during the pandemic will be open access (ie, freely accessible).

The first case of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in the United States was identified in Washington state in late January 2020. As of mid-April 2020, the number of US cases has increased to more than 800,000 with over 40,000 deaths. The limited available knowledge to guide medical decision-making combined with rapid progression of the pandemic has resulted in an urgent need to better define clinical, radiologic, and laboratory features of the disease, predictors of disease progression, predominant modes of transmission, and effective treatments. This urgency has led to a flood of manuscript submissions, which strains the scientific vetting process and leads to the spread of medical misinformation and potential for serious harm. As an example, a small observational (noncontrolled) study that used an antimalarial drug to treat COVID-19 patients was touted by several national leaders as proof of its effectiveness, despite substantial methodologic limitations.1,2 While the article has not yet been retracted, the International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy, the publishing journal’s society sponsor, subsequently issued a statement that “the article does not meet the Society’s expected standard.”3

With these concerns in mind, we recognize the importance of addressing the current pandemic and identifying areas where we can advance the field responsibly in the face of limited evidence in a rapidly evolving situation. Hospitalists throughout the world are facing unprecedented leadership challenges, navigating ethical stressors, and redesigning their care systems while learning rapidly and adapting nimbly. In this issue, we share leadership strategies, explore ethical challenges and controversies, describe successful practices, and provide personal reflections from a diverse group of hospitalists and leaders. As a journal, we have intentionally avoided rapid publication of articles with substantial methodologic limitations that are unlikely to advance our knowledge of COVID-19 even though such articles may generate substantial media coverage. Different regions of the country are at different stages of the pandemic; some hospitals are experiencing high patient volumes and struggling with shortages of equipment and supplies, while others are weeks away from peak disease activity or have avoided periods of high prevalence altogether. These varied experiences offer an opportunity to share our learnings and perspectives as we wait for more definitive evidence on best management practices. As part of our commitment to our colleagues in healthcare and to the broader scientific community, all Journal of Hospital Medicine articles related to COVID-19 and published during the pandemic will be open access (ie, freely accessible).

1. Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949.

2. Baker P, Rogers K, Enrich D, Haberman M. Trump’s aggressive advocacy of malaria drug for treating coronavirus divides medical community. New York Times. April 6, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/us/politics/coronavirus-trump-malaria-drug.html. Accessed April 13, 2020.

3. International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. Statement on International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents paper. https://www.isac.world/news-and-publications/official-isac-statement. Accessed April 13, 2020.

1. Gautret P, Lagier JC, Parola P, et al. Hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin as a treatment of COVID-19: results of an open-label non-randomized clinical trial. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2020.105949.

2. Baker P, Rogers K, Enrich D, Haberman M. Trump’s aggressive advocacy of malaria drug for treating coronavirus divides medical community. New York Times. April 6, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/04/06/us/politics/coronavirus-trump-malaria-drug.html. Accessed April 13, 2020.

3. International Society of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy. Statement on International Journal of Antimicrobial Agents paper. https://www.isac.world/news-and-publications/official-isac-statement. Accessed April 13, 2020.

© 2020 Society of Hospital Medicine

Discharge Summary Improvement

Preventable or ameliorable adverse events have been reported to occur in 12% of patients in the period immediately following hospital discharge.1, 2 A potential contributor to this is the inadequate transfer of clinical information at hospital discharge. The discharge summary comprises a vital component of the information transfer between the inpatient and outpatient settings. Unfortunately, discharge summaries are often unavailable at the time of follow‐up care and often lack important content.37

A growing number of hospitals are implementing electronic medical records (EMR). This creates the opportunity to standardize the content of clinical documentation and creates the potential to assemble, immediately at the time of hospital discharge, major components of a discharge summary. With enhanced communication systems, this information can be delivered in a variety of ways with minimal delay. Previously, we reported the results of a survey of medicine faculty at an urban academic medical center evaluating the timeliness and quality of discharge summaries, the perceived incidence of preventable adverse events related to suboptimal information transfer at discharge, and a needs assessment for an electronically generated discharge summary that we planned to design.8 We now report the results of the follow‐up survey of outpatient physicians and an evaluation of the quality and timeliness of the electronic discharge summary we created.

Materials and Methods

Design

We conducted a pre‐post evaluation of the quality and timeliness of discharge summaries. In the initial phase of the study, we convened an advisory board comprised of 16 Department of Medicine physicians. The advisory board gave input on needs assessment and helped to create a survey to be administered to all medicine faculty with an outpatient practice. All respondents who had at least 1 patient admitted to the hospital within the 6 months prior to the survey were eligible. The results of the initial survey were reviewed with the advisory board and an electronic discharge summary was created with their input. To evaluate its impact, we conducted a repeat survey of all medicine faculty with an outpatient practice approximately 1 year after implementation of the electronic discharge summary.

To complement data received from the outpatient physician survey, a randomly selected sample of discharge summaries from general medical services during the same 3 month period before and after implementation of the electronic discharge summary were rated by 1 of 3 board‐certified internists (D.B.E., N.K., or M.P.L.).

Setting and Participants

The study was conducted at Northwestern Memorial Hospital, a 753‐bed hospital in Chicago, IL. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. General medical patients were admitted to 1 of 2 primary physician services during the study period: a teaching service or a nonteaching hospitalist service. Discharge summaries had traditionally been dictated by inpatient physicians and delivered to outpatient physicians by both mail and facsimile via the medical record department. A recommended template for dictated discharge summaries was provided in the paper paging directory distributed yearly to inpatient physicians.

The hospital implemented an EMR and computerized physician order entry (CPOE) system (PowerChart Millennium; Cerner Corporation, Kansas City, MO) in August 2004. Although all history and physicals and progress notes were documented in the EMR, the system did not provide a method for delivering discharge summaries performed within the EMR to outpatient physician offices. Because of this, inpatient physicians were instructed to continue to dictate discharge summaries during the initial phase of the study.

Approximately 65% of outpatient physicians at the study site used an EMR in their offices during the study. Approximately 10% of outpatient physicians used the same EMR the hospital uses, while approximately 55% used a different EMR (EPIC Hyperspace; EPIC Systems Corporation, Verona, WI). The remaining physicians did not use an EMR in their offices.

Intervention: The Electronic Discharge Summary

A draft electronic discharge summary template was created by including elements ranked as highly important by outpatient physicians in our initial survey8 and elements required by The Joint Commission.9 The draft electronic discharge summary template was reviewed by the advisory board and modifications were made with their input. We automated the insertion of specific patient data elements, such as listed allergies and home medications, into the discharge summary template. We also created an electronic reminder system to inpatient physicians for summaries not completed 24 hours after discharge.

Because the majority of physicians in our initial survey preferred discharge summaries to be delivered either by facsimile or via an EMR, we concentrated our efforts on creating reliable systems for delivery by those routes. We created logic that queried the primary care physician field within the EMR at the time the discharge summary was electronically signed. An automated process then sent the discharge summary via electronic fax to the physician listed in the primary care physician field. Because a large number of outpatient physicians used an EMR different from the hospital's, we also created a process that sent discharge summaries from the hospital EMR into patient charts within this separate EMR.

The draft electronic discharge summary template was available for use in the EMR beginning in July 2005. The final electronic discharge summary, including automated content, physician reminder for incomplete summaries, and delivery systems as described above was implemented in June 2006. Upon implementation, inpatient physicians were instructed via email announcements and group meetings to begin completing electronic discharge summaries using the EMR. Beyond these announcements, inpatient physicians did not receive any specific training with regard to the new discharge summary process. An example of the final electronic discharge summary product is available in the Appendix.

Outpatient Physician Survey

Satisfaction with timeliness and quality of discharge summaries was assessed using a 5‐point Likert scale, where 5 represented very satisfied and 1 represented very dissatisfied. We also asked respondents to estimate the number of their patients who had sustained a preventable adverse event or near miss related to suboptimal transfer of information at discharge. We defined a preventable adverse event as a preventable medical problem or worsening of an existing problem and near miss as an error that did not result in patient harm but easily could have.

The preimplementation survey, accompanied by a cover letter signed by the hospital's chief of staff, was sent out in March 2005. A postcard reminder was sent approximately 2 weeks after the initial mail survey. A second survey was sent to nonresponders 6 weeks after the initial survey. Simultaneously, the survey was also sent in web‐based format to nonresponders via email. The postimplementation survey was sent out in February 2007 using a similar survey process.

Discharge Summary Review

A random sample of discharge summaries completed before and after the implementation of the electronic discharge summary was selected for review. The sample universe consisted of all general medicine service discharges between August and November 2005, before the electronic discharge summary was implemented, and August to November 2006, after implementation. To provide a balanced comparison, the sample was further limited to only the first chronological (index) discharge of a unique patient to home self‐care or home health nursing, with length of stay between 3 and 14 days. A total of 2232 discharges in 2005 and 2570 discharges in 2006 met these criteria. The discharge summary review sample was designed to randomly select approximately 100 discharge summaries meeting the criteria above within each study year, to produce an approximate 200‐record analysis sample. Each of the 3 physician reviewers was assigned to complete an approximately equal number of the 200 primary reviews.

Physician reviewers recorded whether the discharge summary was dictated versus done electronically, the length of the discharge summary (in words), the number of days from discharge to discharge summary completion, the type of service the patient was discharged from, and the author type (medical student, intern, resident, or attending). Physicians reviewers also assessed the overall clarity of discharge summaries using a 5‐point ordinal scale (1 = unintelligible; 2 = hard to read; 3 = neutral; 4 = understandable; and 5 = lucid).

Prior studies have evaluated the quality of discharge summaries using scoring tools created by the investigators.10, 11 We created our own discharge summary scoring tool based on these prior studies, recommendations from the literature,12 and the findings from our initial survey.8 We pilot‐tested the scoring tool and made minor revisions prior to the study. The final scoring tool consisted of 16 essential elements. Reviewers assessed whether each of the 16 essential elements was present, absent, or not applicable. A Discharge Summary Completeness Score was calculated by the number of the 16 essential elements that were rated as present divided by the number of applicable elements for each discharge summary, multiplied by 100 to produce a completeness percentage.

To assess interrater reliability, reviewers were assigned to independently complete second, duplicate reviews of approximately 90 summaries (30 per reviewer). The duplicate review sample was designed to produce approximately 45 paired re‐reviews in each year for reliability assessment. A final sample of 196 available summaries was completed for the main analysis and 174 primary and duplicate reviews were used to establish interrater reliability across 87 reviewer pairs.

Data Analysis

Physician characteristics, including specialty, faculty appointment type, and year of medical school graduation were provided by the hospital's medical staff office. Physician characteristics from before and after the implementation of the electronic discharge summary were compared using chi‐square tests. Likert scale ratings of physician satisfaction with the timeliness and quality of discharge summaries were compared using t‐tests. The proportion of physicians reporting 1 or more preventable adverse event or near miss before the implementation of the electronic discharge summary was compared to postimplementation proportions using chi‐square tests. In addition, we performed multivariate logistic regression to examine the likelihood of physicians reporting any preventable adverse event or near miss related to suboptimal information transfer. The regression models tested the likelihood of 1 or more preventable adverse event or near miss before versus after the implementation of the electronic discharge summary, controlling for physician characteristics and their number of hospitalized patients in the previous 6 months.

The proportions of discharge summary elements found to be present, the proportion of discharge summaries completed within 3 days, and discharge summary readability ratings before and after the implementation of the electronic discharge summary were compared using chi‐square tests; length in words was compared using t‐tests. Preimplementation and postimplementation Discharge Summary Completeness Scores were compared using the Mann‐Whitney U test. Discharge summary score interrater reliability was assessed using the Brennan‐Prediger Kappa for individual elements.13

Results

Outpatient Physician Survey

Physician Characteristics

Two hundred and twenty‐six of 416 (54%) eligible outpatient physicians completed the baseline survey and 256 of 397 (64%) completed the postimplementation survey. As shown in Table 1, there were no significant differences in specialty, faculty appointment type, or number of patients hospitalized between respondents to the survey before compared to respondents after the implementation of the electronic discharge summary. The number of respondents graduating medical school in 1990 or later was higher after implementation of the electronic discharge summary; however, this result was of borderline statistical significance.

| Preelectronic Discharge Summary (n = 226) | Postelectronic Discharge Summary (n = 256) | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Practice Type | 0.23 | ||

| Generalist, n (%) | 127 (56.2) | 130 (50.8) | |

| Specialist, n (%) | 99 (43.8) | 126 (49.2) | |

| Faculty Appointment | 0.38 | ||

| Full‐time, n (%) | 104 (46.0) | 128 (50.0) | |

| Affiliated, n (%) | 122 (54.0) | 128 (50.0) | |

| Year of medical school graduation* | 0.06 | ||

| Before 1990, n (%) | 128 (57.4) | 124 (48.8) | |

| 1990 or later, n (%) | 95 (42.6) | 130 (51.2) | |

| Number of patients hospitalized (last 6 months) | 0.56 | ||

| 1‐4, n (%) | 15 (7.9) | 24 (12.0) | |

| 5‐10, n (%) | 62 (32.5) | 66 (33.0) | |

| 11‐19, n (%) | 35 (18.3) | 33 (16.5) | |

| 20 or more, n (%) | 79 (41.4) | 77 (38.5) | |

Timeliness and Content

Changes in outpatient physician satisfaction with the timeliness and quality of discharge summaries are summarized in Table 2. Satisfaction with the timeliness and quality of discharge summarizes improved significantly after the implementation of the electronic discharge summary (mean standard deviation [SD] timeliness rating, 2.59 1.02 versus 3.34 1.09; P < 0.001, mean quality rating 3.04 0.93 versus 3.64 0.99; P < 0.001).

| Likert Scale Mean Score (SD)* | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preelectronic Discharge Summary | Postelectronic Discharge Summary | P Value | |

| |||

| Timeliness of the discharge summary | 2.59 (1.02) | 3.34 (1.09) | <0.001 |

| Quality of the discharge summary | 3.04 (0.93) | 3.64 (0.99) | <0.001 |

Medical Error

The effect of the electronic discharge summary on perceived near misses and preventable adverse events is summarized in Table 3. Fewer outpatient physicians felt that 1 or more of their patients hospitalized in the preceding 6 months sustained a near miss due to suboptimal transfer of information after the implementation of the electronic discharge summary (65.7% vs. 52.9%, P = 0.008). Similarly, fewer outpatient physicians felt that 1 or more of their patients hospitalized in the preceding 6 months sustained a preventable adverse event due to suboptimal transfer of information after the implementation of the electronic discharge summary (40.7% vs. 30.2%, P = 0.02). In multivariate logistic regression analyses controlling for physician characteristics and their number of hospitalized patients in the previous 6 months, there was a statistically significant 40% reduction in the odds of a reported near miss (adjusted odds ratio [OR] = 0.60, P = 0.02). Although not quite statistically significant, there was a 33% reduction in the odds of a reported preventable adverse event (OR = 0.67, P = 0.08) after the implementation of the electronic discharge summary.

| Preelectronic Discharge Summary | Postelectronic Discharge Summary | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Near miss* | |||

| Number (%) reporting 1 | 142 (65.7) | 108 (52.9) | |

| Crude odds ratio | Ref. | 0.57 | 0.008 |

| Adjusted odds ratio | Ref. | 0.60 | 0.02 |

| Preventable adverse event | |||

| Number (%) reporting 1 | 88 (40.7) | 62 (30.2) | |

| Crude odds ratio | Ref. | 0.63 | 0.03 |

| Adjusted odds ratio | Ref. | 0.67 | 0.08 |

Discharge Summary Review

Discharge Summary Characteristics

One hundred and one discharge summaries before implementation of the electronic discharge summary were compared to 95 discharge summaries produced the following year. Characteristics of discharge summaries before and after the implementation of the electronic discharge summary are summarized in Table 4. A large number of discharge summaries (52.5%) were already being typed into the EMR in 2005, prior to the implementation of our final electronic discharge summary product. The number of dictated discharge summaries decreased from 47.5% to 10.5% after implementation of the final electronic discharge summary product (P < 0.001). Discharge summaries were similar in length before and after the implementation of the electronic discharge summary. A higher percentage of discharge summaries were completed within 3 days of discharge after implementation of the electronic discharge summary; however, this result was of borderline statistical significance (59.4% vs. 72.6%; P = 0.05). The type of service from which patients were discharged and the distribution of author types were similar after the implementation of the electronic discharge summary.

| Number (%) or MeanSD | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preelectronic Discharge Summary (n = 101) | Postelectronic Discharge Summary (n = 95) | ||

| Dictated, n (%) | 48 (47.5) | 10 (10.5) | <0.001 |

| Length in words, mean SD | 785 407 | 830 389 | 0.43 |

| Completed within 3 days, n (%) | 60 (59.4) | 69 (72.6) | 0.05 |

| Type of service, n (%) | 0.29 | ||

| Teaching service | 63 (62.4) | 66 (69.5) | |

| Nonteaching hospitalist service | 38 (37.6) | 29 (30.5) | |

| Author type, n (%) | 0.62 | ||

| Fourth year medical student | 13 (12.9) | 13 (13.7) | |

| Intern | 31 (30.7) | 37 (38.9) | |

| Resident | 19 (18.8) | 15 (15.8) | |

| Attending | 38 (37.6) | 30 (31.6) | |

Because a large percentage of discharge summaries were already being done electronically in 2005, we evaluated the timeliness of dictated discharge summaries compared to electronic discharge summaries across both periods combined (preimplementation and postimplementation of the electronic discharge summary). A higher percentage of electronic discharge summaries were completed within 3 days of discharge as compared to dictated discharge summaries (44.8% versus 74.1%; P < 0.001).

Discharge Summary Completeness Score

The presence or absence of discharge summary elements before and after the implementation of the electronic discharge summary is shown in Table 5. Several elements of the discharge summary were present more often after the implementation of the electronic discharge summary. Specific improvements included discussion of follow‐up issues (52.0% versus 75.8%; P = 0.001, = 0.78), pending test results (13.9% vs. 46.3%; P < 0.001, = 0.92), and information provided to the patient and/or family (85.1% vs. 95.8%; P = 0.01, = 0.91). Significant laboratory findings were present less often after implementation of the electronic discharge summary (66.0% versus 51.1%; P = 0.04, = 0.84). The Discharge Summary Completeness Score was higher after the implementation of the electronic discharge summary (mean 74.1 versus 80.3, P = 0.007). Dictated discharge summaries had a significantly lower Discharge Summary Completeness Score compared to discharge summaries done electronically (71.3 vs. 79.6, P = 0.002) across both periods combined.

| Number (%) of Content Items Present* | P Value | Brennan‐Prediger Kappa | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preelectronic Discharge Summary (n = 101) | Postelectronic Discharge Summary (n = 95) | |||

| ||||

| Dates of admission and discharge | 96 (95.0) | 94 (98.9) | 0.11 | 1.0 |

| Reason for hospitalization | 100 (99.0) | 94 (100) | 0.33 | 1.0 |

| Significant findings from history and exam | 78 (77.2) | 65 (68.4) | 0.16 | 0.26 |

| Significant laboratory findings | 64 (66.0) | 47 (51.1) | 0.04 | 0.84 |

| Significant radiological findings | 67 (75.3) | 71 (81.6) | 0.31 | 0.89 |

| Significant findings from other tests | 41 (63.1) | 40 (71.4) | 0.33 | 0.88 |

| List of procedures performed | 45 (81.8) | 35 (77.8) | 0.77 | 0.99 |

| Procedure report findings | 49 (80.3) | 43 (78.2) | 0.61 | 0.92 |

| Stress test report findings | 7 (100) | 3 (100) | N/A | 1.0 |

| Pathology report findings | 11 (39.3) | 3 (30.0) | 0.60 | 0.91 |

| Discharge diagnosis | 89 (88.1) | 86 (93.5) | 0.20 | 0.86 |

| Condition at discharge | 81 (81.0) | 80 (85.1) | 0.45 | 0.76 |

| Discharge medications | 88 (87.1) | 88 (93.6) | 0.13 | 0.79 |

| Follow‐up issues | 52 (52.0) | 72 (75.8) | 0.001 | 0.78 |

| Pending test results | 14 (13.9) | 44 (46.3) | <0.001 | 0.92 |

| Information provided to patient and/or family, as appropriate | 86 (85.1) | 91 (95.8) | 0.01 | 0.91 |

| Discharge Summary Completeness Score (percent present all applicable items) | 74.1 | 80.3 | 0.007 | |

Significantly more discharge summaries were rated as understandable or lucid after the implementation of the electronic discharge summary (41.6% vs. 59.0%; P = 0.02). In both periods combined, dictated discharge summaries were rated as understandable or lucid less often than electronic discharge summaries (34.5% vs. 56.5%; P < 0.001).

Discussion

Our study found that an electronic discharge summary was well accepted by inpatient physicians and significantly improved the quality and timeliness of discharge summaries. Prior studies have shown that the use of electronically entered discharge summaries improved the timeliness of discharge summaries.1416 However, the discharge summaries used in these studies required manual input of data into a computer system separate from the patient's medical record. To our knowledge, this is the first study to report the impact of discharge summaries generated from an EMR. Leveraging the EMR, we were able to automate the insertion of specific patient data elements, streamline delivery, and create an electronic reminder system to inpatient physicians for summaries not completed 24 hours after discharge.

Prior research has shown that the quality of discharges summaries is improved with the use of standardized content.10, 17 Using a standardized template for the electronic discharge summary, we likewise demonstrated improved quality of discharge summaries. Key discharge summary elements, specifically discussion of follow‐up issues, pending test results, and information provided to the patient and/or family, were present more reliably after the implementation of the electronic discharge summary. The importance of identifying pending test results is underscored by a recent study showing that many patients are discharged from hospitals with test results still pending, and that physicians are often unaware when results are abnormal.18 One discharge summary element, significant laboratory findings, was present less often after the implementation of the electronic discharge summary. Our template did not designate significant laboratory findings under a separate heading. Instead, we used a heading entitled Key Results (labs, imaging, pathology). Physicians completing the discharge summaries may have prioritized the report of imaging and pathology results in this section. A simple revision of our discharge summary template to include a separate heading for significant laboratory findings may result in improvement in this regard.

Timeliness of discharge summaries was improved in our study, but remained less than optimal. Although nearly three‐quarters of electronic discharge summaries were completed within 3 days of discharge, our ultimate goal is to have 100% of discharge summaries completed within 3 days. This is especially important for complicated patients requiring outpatient follow‐up soon after discharge. We are currently in the process of designing further modifications to the electronic discharge summary completion process. One modification that may be beneficial is the automation of additional patient specific data elements into the discharge summary. We also plan to link performance of medication reconciliation, completion of patient discharge instructions, and completion of the discharge summary into an integrated set of activities performed in the EMR prior to patient discharge.

We found that fewer outpatient physicians reported 1 or more of their patients having a preventable adverse event or near miss as a result of suboptimal transfer of information at discharge after the implementation of the electronic discharge summary. Although we did not measure preventable adverse events directly in our study, this is an important finding in light of the large number of patients who sustain preventable adverse events after hospital discharge1, 2 and prior research showing that the absence of discharge summaries at postdischarge follow‐up visits increased the risk for hospital readmission.19

We had wondered what effect the electronic discharge summary would have on the length and clarity of discharge summaries. A published commentary suggested that notes performed in EMRs were inordinately long and often difficult to read.20 We were pleased to discover that electronic discharge summaries were similar in length to previous discharge summaries and were rated higher with regard to clarity.

Our study has several limitations. First, many inpatient physicians began to use electronic discharge summaries prior to our creation of the final electronic discharge summary product. We had explicitly instructed physicians to continue to dictate discharge summaries in the first phase of our study. The fact that physicians quickly adopted the practice of completing discharge summaries electronically suggests that they preferred this method for completion and may help to explain the improvement in timeliness. A second limitation, as previously mentioned, is that our study did not measure adverse events directly. Instead, we asked outpatient physicians to estimate the number of their patients discharged in the last 6 months who had sustained a preventable adverse event or near miss related to suboptimal information transfer at discharge. We had limited space in the survey to define the meaning of a preventable adverse event; therefore, the description in the survey does not exactly match previous definitions.1, 2 Finally, the ordinal scale used to assess clarity of discharge summaries has not been previously validated.