User login

Striking While the Iron Is Hot: Using the Updated PHM Competencies in Time-Variable Training

In July 2020, the revision of The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies was published, bringing to fruition three years of meticulous work.1 The working group produced 66 chapters outlining the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed for competent pediatric hospitalist practice. The arrival of these competencies is especially prescient given pediatric hospital medicine’s (PHM’s) relatively new standing as an American Board of Medical Specialties certified subspecialty, as the competencies can serve as a guide for improvement of fellowship curricula, assessment systems, and faculty development. The competencies also represent an opportunity for PHM to take a bold step forward in the world of graduate medical education (GME) by realizing a key tenet of competency-based medical education (CBME)—competency-based, time-variable training (CBTVT), in which learners train until competence is achieved rather than for a predetermined duration.2,3 In this perspective, we describe how medical education in the United States adopted a time-based training paradigm (in which time-in-training is a surrogate for competence), how CBME has brought time-variable training to the fore, and how PHM has an opportunity to be on the leading edge of education innovation.

TIME-BASED TRAINING IN THE UNITED STATES

In the 1800s, during the time of the “Wild West,” medical education in the United States matched this moniker. There was little standardization across the multiple training pathways to become a practicing physician, including apprenticeships, lecture series, and university courses.4 Predictably, this led to significant heterogeneity in the quality of medical care that a patient of the day received. This problem became clearer as Americans traveled to Europe and witnessed more structured and rigorous training programs, only to return to the comparatively poor state of medical education back home.5 There was a clear need for curricular standardization.

In 1876, the American Medical College Association (which later became the Association of American Medical Colleges [AAMC]) was founded to meet this need, and in 1905 the Association adopted a set of minimum standards for medical training that included the now-familiar two years of basic sciences and two years of clinical training.6 Two subsequent national surveys in the United States were commissioned to evaluate whether medical schools met this new standard, with both surveys finding that roughly half of existing programs passed muster.7,8 As a result, nearly half of US medical schools had closed by 1920 in a crusade to standardize curricula and produce competent physicians. By the time the American Medical Association established initial standards for internship (an archetype of GME),4 time-based medical training was the dominant paradigm. This historical perspective highlights the rationale for standardization of education processes and curricula, particularly in terms of accountability to the American public. But heralded by the 1978 landmark paper by McGaghie et al,9 the paradigm began to shift in the late twentieth century from a focus on the process of physician training to outcomes.

CBME AND TIME VARIABILITY

In contrast to the process-focused model of the early 1900s, CBME starts by identifying patient and healthcare system needs, defining competencies required to meet those needs, and then designing curricular and assessment processes to help learners achieve those competencies.2 This outcomes-based approach grew as a response to calls for greater accountability to the public due to evidence that some graduates were unprepared for unsupervised practice, raising concerns that strictly time-based training was no longer defensible.10 CBME aims to mitigate these concerns by starting with desired outcomes of training and working backward to ensure those outcomes are met.

While many programs have attempted to implement CBME, most still rely heavily on time-in-training to determine competence. Learners participate in structured curricula and, unless they are extreme outliers, are deemed ready for unsupervised practice after a predetermined duration. This model presumes that competence and time are related in a fixed, predictable manner and that learners gain competence at a uniform rate. However, learners do not, in fact, progress uniformly. A study by Schumacher et al11 involving 23 pediatric residency programs showed significant interlearner variability in rates of entrustment (used as a surrogate for competence), leading the authors to call for time-variable training in GME. Significant interlearner variation in rates of competence attainment have been shown in other specialties as well.12 As more CBME studies on training outcomes emerge, the evidence is mounting that not all learners need the same duration of training to become competent providers. Time-in-training and competence attainment are not related in a fixed manner. As Dr Jason13 wrote in 1969, “By making time a constant, we make achievement a variable.” Variable achievement (competence, outcomes) was the very driver for medical education’s shift to a competency-based approach. If variable competence was not acceptable then, why should it be now? The goal of CBTVT is not shorter training, but rather flexible, individualized training both in terms of content and duration. While this also means some learners may need to extend their training, this should already be part of GME programs that are required to have remediation policies for learners who are not progressing as expected.

AN OPPORTUNITY FOR PHM

Time variability is an oft-cited tenet of CBME,2,3 but one that is being piloted by relatively few programs in the United States, mostly in undergraduate medical education (UME).14-16 The Education in Pediatrics Across the Continuum (EPAC), a consortium consisting of four institutions piloting CBTVT in UME,14 has shown early evidence of feasibility17 and that UME graduates from CBTVT programs enter residency with levels of competence similar to those of graduates of traditional time-based programs.18 We believe that PHM can take a step toward truly realizing CBME by implementing CBTVT in fellowship programs.

There are multiple reasons why this is an opportune time for PHM fellowships to consider CBTVT. First, PHM is a relatively new board-certified subspecialty with a recently revised set of core competencies1 that are likely to catalyze programmatic innovation. A key step in change management is building on previous efforts to generate more change.19 Programs can leverage the momentum from current and impending change initiatives to innovate and implement CBTVT. Second, the revised PHM competencies provide the first crucial step in implementing a CBME program by defining desired training outcomes necessary to deliver high-quality patient care. With PHM competencies now well defined, programs can focus on developing programs of assessment and corresponding faculty development, which can help deliver valid, defensible decisions about fellow competence.

Finally, PHM has a workforce that can support CBTVT. A major barrier to time-variable training in GME is the need for trainees-as-workforce. In many GME programs, residents and fellows provide a relatively inexpensive, renewable workforce. Trainees’ clinical rotations are often scheduled up to 1 year in advance to ensure care teams are fully staffed, particularly in the inpatient setting, creating a system where flexibility in training is impossible without creating gaps in clinical coverage. However, many PHM fellowships do not completely rely on fellows to cover clinical service lines. PHM fellows spend 32 weeks over 2 years in core clinical rotations with faculty supervision, in accordance with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education program requirements, both for 2- and 3-year programs. Some CBME experts estimate (based on previous and ongoing CBTVT pilots) that training duration is likely to vary by roughly 20% from current time-based practices when CBTVT is initially implemented.20 Thus, only a small number of clinical service weeks are likely to be affected. If a fellow were deemed ready for unsupervised practice before finishing 2 years of fellowship in a CBTVT program, the corresponding faculty supervisor could use the time previously assigned for supervision to pursue other priorities, such as education, scholarship, or quality improvement. Why provide supervision if a clinical competency committee has deemed a fellow ready for unsupervised practice? Some level of observation and formative feedback could continue, but full supervision would be redundant and unnecessary. CBTVT would allow for some fellows to experience the uncertainty that comes with unsupervised decision-making while still in an environment with trusted fellowship mentors and advisors.

STEPS TOWARD CHANGE

PHM fellowship programs likely cannot flip a switch to “turn on” CBTVT immediately, but they can take steps toward making the transition. Validity, or defensibility of decisions, will be crucial for assessment in CBTVT systems. Programs will need to develop robust assessment systems that collect myriad data to answer the question, “When is this learner competent to deliver high-quality care without supervision?” Programs can align assessment instruments, faculty-development initiatives, and clinical competency committee (CCC) processes with the 2020 PHM competencies to provide a defensible answer. Program leaders should then seek validity evidence, either in existing literature or through novel scholarly initiatives, to support these summative decisions. Engaging all fellowship stakeholders in transitions to CBTVT will be important and should include fellows, program directors, CCC members, clinical leadership, and members from accrediting and credentialing bodies.

CONCLUSION

As fellowship programs review and revise curricula and assessment systems around the updated PHM core competencies, they should also consider what changes are necessary to implement CBTVT. Time variability is not a novelty but, rather, is a corollary to the outcomes-based approach of CBME. PHM fellowships should strike while the iron is hot and build on current change initiatives prompted by the growth of our specialty to be leaders in CBTVT.

1. Maniscalco J, Gage S, Sofia Teferi M, Fisher ES. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies: 2020 Revision. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(7):389-394. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3391

2. Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):638-645. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.501190

3. Lucey CR, Thibault GE, Ten Cate O. Competency-based, tme-variable education in the health professions: crossroads. Acad Med. 2018;93(3S Competency-Based, Time-Variable Education in the Health Professions):S1-S5. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002080

4. Custers EJFM, Ten Cate O. The history of medical education in Europe and the United States, with respect to time and proficiency. Acad Med. 2018;93(3S Competency-Based, Time-Variable Education in the Health Professions):S49-S54. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002079

5. Barr DA. Revolution or evolution? Putting the Flexner Report in context. Med Educ. 2011;45(1):17-22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03850.x

6. Association of American Medical Colleges. Minutes of the Fifteenth Annual Meeting. April 10, 1905; Chicago, IL.

7. Bevan A. Council on Medical Education of the American Medical Association. JAMA. 1907;48(20):1701-1707.

8. Flexner A. Medical education in the United States and Canada. From the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, Bulletin Number Four, 1910. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80(7):594-602.

9. McGaghie WC, Sajid AW, Miller GE, et al. Competency-based curriculum development in medical education: an introduction. Public Health Pap. 1978;(68):11-91.

10. Frank JR, Snell L, Englander R, Holmboe ES, ICBME Collaborators. Implementing competency-based medical education: moving forward. Med Teach. 2017;39(6):568-573. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1315069

11. Schumacher DJ, West DC, Schwartz A, et al. Longitudinal assessment of resident performance using entrustable professional activities. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1):e1919316. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.19316

12. Warm EJ, Held J, Hellman M, et al. Entrusting observable practice activities and milestones over the 36 months of an internal medicine residency. Acad Med. 2016;91(10):1398-1405. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001292

13. Jason H. Effective medical instruction: requirements and possibilities. In: Proceedings of a 1969 International Symposium on Medical Education. Medica; 1970:5-8.

14. Andrews JS, Bale JF Jr, Soep JB, et al. Education in Pediatrics Across the Continuum (EPAC): first steps toward realizing the dream of competency-based education. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):414-420. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002020

15. Mejicano GC, Bumsted TN. Describing the journey and lessons learned implementing a competency-based, time-variable undergraduate medical education curriculum. Acad Med. 2018;93(3S Competency-Based, Time-Variable Education in the Health Professions):S42-S48. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002068

16. Goldhamer MEJ, Pusic MV, Co JPT, Weinstein DF. Can COVID catalyze an educational transformation? Competency-based advancement in a crisis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(11):1003-1005. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2018570

17. Murray KE, Lane JL, Carraccio C, et al. Crossing the gap: using competency-based assessment to determine whether learners are ready for the undergraduate-to-graduate transition. Acad Med. 2019;94(3):338-345. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002535

18. Schwartz A, Balmer DF, Borman-Shoap E, et al. Shared mental models among clinical competency committees in the context of time-variable, competency-based advancement to residency. Acad Med. 2020;95(11S Association of American Medical Colleges Learn Serve Lead: Proceedings of the 59th Annual Research in Medical Education Presentations):S95-S102. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003638

19. Kotter JP. Leading change: why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Business Review. May-June 1995. Accessed March 1, 2021. https://hbr.org/1995/05/leading-change-why-transformation-efforts-fail-2

20. Schumacher DJ, Caretta-Weyer H, Busari J, et al. Competency-based time-variable training internationally: ensuring practical next steps. Med Teach. Forthcoming.

In July 2020, the revision of The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies was published, bringing to fruition three years of meticulous work.1 The working group produced 66 chapters outlining the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed for competent pediatric hospitalist practice. The arrival of these competencies is especially prescient given pediatric hospital medicine’s (PHM’s) relatively new standing as an American Board of Medical Specialties certified subspecialty, as the competencies can serve as a guide for improvement of fellowship curricula, assessment systems, and faculty development. The competencies also represent an opportunity for PHM to take a bold step forward in the world of graduate medical education (GME) by realizing a key tenet of competency-based medical education (CBME)—competency-based, time-variable training (CBTVT), in which learners train until competence is achieved rather than for a predetermined duration.2,3 In this perspective, we describe how medical education in the United States adopted a time-based training paradigm (in which time-in-training is a surrogate for competence), how CBME has brought time-variable training to the fore, and how PHM has an opportunity to be on the leading edge of education innovation.

TIME-BASED TRAINING IN THE UNITED STATES

In the 1800s, during the time of the “Wild West,” medical education in the United States matched this moniker. There was little standardization across the multiple training pathways to become a practicing physician, including apprenticeships, lecture series, and university courses.4 Predictably, this led to significant heterogeneity in the quality of medical care that a patient of the day received. This problem became clearer as Americans traveled to Europe and witnessed more structured and rigorous training programs, only to return to the comparatively poor state of medical education back home.5 There was a clear need for curricular standardization.

In 1876, the American Medical College Association (which later became the Association of American Medical Colleges [AAMC]) was founded to meet this need, and in 1905 the Association adopted a set of minimum standards for medical training that included the now-familiar two years of basic sciences and two years of clinical training.6 Two subsequent national surveys in the United States were commissioned to evaluate whether medical schools met this new standard, with both surveys finding that roughly half of existing programs passed muster.7,8 As a result, nearly half of US medical schools had closed by 1920 in a crusade to standardize curricula and produce competent physicians. By the time the American Medical Association established initial standards for internship (an archetype of GME),4 time-based medical training was the dominant paradigm. This historical perspective highlights the rationale for standardization of education processes and curricula, particularly in terms of accountability to the American public. But heralded by the 1978 landmark paper by McGaghie et al,9 the paradigm began to shift in the late twentieth century from a focus on the process of physician training to outcomes.

CBME AND TIME VARIABILITY

In contrast to the process-focused model of the early 1900s, CBME starts by identifying patient and healthcare system needs, defining competencies required to meet those needs, and then designing curricular and assessment processes to help learners achieve those competencies.2 This outcomes-based approach grew as a response to calls for greater accountability to the public due to evidence that some graduates were unprepared for unsupervised practice, raising concerns that strictly time-based training was no longer defensible.10 CBME aims to mitigate these concerns by starting with desired outcomes of training and working backward to ensure those outcomes are met.

While many programs have attempted to implement CBME, most still rely heavily on time-in-training to determine competence. Learners participate in structured curricula and, unless they are extreme outliers, are deemed ready for unsupervised practice after a predetermined duration. This model presumes that competence and time are related in a fixed, predictable manner and that learners gain competence at a uniform rate. However, learners do not, in fact, progress uniformly. A study by Schumacher et al11 involving 23 pediatric residency programs showed significant interlearner variability in rates of entrustment (used as a surrogate for competence), leading the authors to call for time-variable training in GME. Significant interlearner variation in rates of competence attainment have been shown in other specialties as well.12 As more CBME studies on training outcomes emerge, the evidence is mounting that not all learners need the same duration of training to become competent providers. Time-in-training and competence attainment are not related in a fixed manner. As Dr Jason13 wrote in 1969, “By making time a constant, we make achievement a variable.” Variable achievement (competence, outcomes) was the very driver for medical education’s shift to a competency-based approach. If variable competence was not acceptable then, why should it be now? The goal of CBTVT is not shorter training, but rather flexible, individualized training both in terms of content and duration. While this also means some learners may need to extend their training, this should already be part of GME programs that are required to have remediation policies for learners who are not progressing as expected.

AN OPPORTUNITY FOR PHM

Time variability is an oft-cited tenet of CBME,2,3 but one that is being piloted by relatively few programs in the United States, mostly in undergraduate medical education (UME).14-16 The Education in Pediatrics Across the Continuum (EPAC), a consortium consisting of four institutions piloting CBTVT in UME,14 has shown early evidence of feasibility17 and that UME graduates from CBTVT programs enter residency with levels of competence similar to those of graduates of traditional time-based programs.18 We believe that PHM can take a step toward truly realizing CBME by implementing CBTVT in fellowship programs.

There are multiple reasons why this is an opportune time for PHM fellowships to consider CBTVT. First, PHM is a relatively new board-certified subspecialty with a recently revised set of core competencies1 that are likely to catalyze programmatic innovation. A key step in change management is building on previous efforts to generate more change.19 Programs can leverage the momentum from current and impending change initiatives to innovate and implement CBTVT. Second, the revised PHM competencies provide the first crucial step in implementing a CBME program by defining desired training outcomes necessary to deliver high-quality patient care. With PHM competencies now well defined, programs can focus on developing programs of assessment and corresponding faculty development, which can help deliver valid, defensible decisions about fellow competence.

Finally, PHM has a workforce that can support CBTVT. A major barrier to time-variable training in GME is the need for trainees-as-workforce. In many GME programs, residents and fellows provide a relatively inexpensive, renewable workforce. Trainees’ clinical rotations are often scheduled up to 1 year in advance to ensure care teams are fully staffed, particularly in the inpatient setting, creating a system where flexibility in training is impossible without creating gaps in clinical coverage. However, many PHM fellowships do not completely rely on fellows to cover clinical service lines. PHM fellows spend 32 weeks over 2 years in core clinical rotations with faculty supervision, in accordance with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education program requirements, both for 2- and 3-year programs. Some CBME experts estimate (based on previous and ongoing CBTVT pilots) that training duration is likely to vary by roughly 20% from current time-based practices when CBTVT is initially implemented.20 Thus, only a small number of clinical service weeks are likely to be affected. If a fellow were deemed ready for unsupervised practice before finishing 2 years of fellowship in a CBTVT program, the corresponding faculty supervisor could use the time previously assigned for supervision to pursue other priorities, such as education, scholarship, or quality improvement. Why provide supervision if a clinical competency committee has deemed a fellow ready for unsupervised practice? Some level of observation and formative feedback could continue, but full supervision would be redundant and unnecessary. CBTVT would allow for some fellows to experience the uncertainty that comes with unsupervised decision-making while still in an environment with trusted fellowship mentors and advisors.

STEPS TOWARD CHANGE

PHM fellowship programs likely cannot flip a switch to “turn on” CBTVT immediately, but they can take steps toward making the transition. Validity, or defensibility of decisions, will be crucial for assessment in CBTVT systems. Programs will need to develop robust assessment systems that collect myriad data to answer the question, “When is this learner competent to deliver high-quality care without supervision?” Programs can align assessment instruments, faculty-development initiatives, and clinical competency committee (CCC) processes with the 2020 PHM competencies to provide a defensible answer. Program leaders should then seek validity evidence, either in existing literature or through novel scholarly initiatives, to support these summative decisions. Engaging all fellowship stakeholders in transitions to CBTVT will be important and should include fellows, program directors, CCC members, clinical leadership, and members from accrediting and credentialing bodies.

CONCLUSION

As fellowship programs review and revise curricula and assessment systems around the updated PHM core competencies, they should also consider what changes are necessary to implement CBTVT. Time variability is not a novelty but, rather, is a corollary to the outcomes-based approach of CBME. PHM fellowships should strike while the iron is hot and build on current change initiatives prompted by the growth of our specialty to be leaders in CBTVT.

In July 2020, the revision of The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies was published, bringing to fruition three years of meticulous work.1 The working group produced 66 chapters outlining the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed for competent pediatric hospitalist practice. The arrival of these competencies is especially prescient given pediatric hospital medicine’s (PHM’s) relatively new standing as an American Board of Medical Specialties certified subspecialty, as the competencies can serve as a guide for improvement of fellowship curricula, assessment systems, and faculty development. The competencies also represent an opportunity for PHM to take a bold step forward in the world of graduate medical education (GME) by realizing a key tenet of competency-based medical education (CBME)—competency-based, time-variable training (CBTVT), in which learners train until competence is achieved rather than for a predetermined duration.2,3 In this perspective, we describe how medical education in the United States adopted a time-based training paradigm (in which time-in-training is a surrogate for competence), how CBME has brought time-variable training to the fore, and how PHM has an opportunity to be on the leading edge of education innovation.

TIME-BASED TRAINING IN THE UNITED STATES

In the 1800s, during the time of the “Wild West,” medical education in the United States matched this moniker. There was little standardization across the multiple training pathways to become a practicing physician, including apprenticeships, lecture series, and university courses.4 Predictably, this led to significant heterogeneity in the quality of medical care that a patient of the day received. This problem became clearer as Americans traveled to Europe and witnessed more structured and rigorous training programs, only to return to the comparatively poor state of medical education back home.5 There was a clear need for curricular standardization.

In 1876, the American Medical College Association (which later became the Association of American Medical Colleges [AAMC]) was founded to meet this need, and in 1905 the Association adopted a set of minimum standards for medical training that included the now-familiar two years of basic sciences and two years of clinical training.6 Two subsequent national surveys in the United States were commissioned to evaluate whether medical schools met this new standard, with both surveys finding that roughly half of existing programs passed muster.7,8 As a result, nearly half of US medical schools had closed by 1920 in a crusade to standardize curricula and produce competent physicians. By the time the American Medical Association established initial standards for internship (an archetype of GME),4 time-based medical training was the dominant paradigm. This historical perspective highlights the rationale for standardization of education processes and curricula, particularly in terms of accountability to the American public. But heralded by the 1978 landmark paper by McGaghie et al,9 the paradigm began to shift in the late twentieth century from a focus on the process of physician training to outcomes.

CBME AND TIME VARIABILITY

In contrast to the process-focused model of the early 1900s, CBME starts by identifying patient and healthcare system needs, defining competencies required to meet those needs, and then designing curricular and assessment processes to help learners achieve those competencies.2 This outcomes-based approach grew as a response to calls for greater accountability to the public due to evidence that some graduates were unprepared for unsupervised practice, raising concerns that strictly time-based training was no longer defensible.10 CBME aims to mitigate these concerns by starting with desired outcomes of training and working backward to ensure those outcomes are met.

While many programs have attempted to implement CBME, most still rely heavily on time-in-training to determine competence. Learners participate in structured curricula and, unless they are extreme outliers, are deemed ready for unsupervised practice after a predetermined duration. This model presumes that competence and time are related in a fixed, predictable manner and that learners gain competence at a uniform rate. However, learners do not, in fact, progress uniformly. A study by Schumacher et al11 involving 23 pediatric residency programs showed significant interlearner variability in rates of entrustment (used as a surrogate for competence), leading the authors to call for time-variable training in GME. Significant interlearner variation in rates of competence attainment have been shown in other specialties as well.12 As more CBME studies on training outcomes emerge, the evidence is mounting that not all learners need the same duration of training to become competent providers. Time-in-training and competence attainment are not related in a fixed manner. As Dr Jason13 wrote in 1969, “By making time a constant, we make achievement a variable.” Variable achievement (competence, outcomes) was the very driver for medical education’s shift to a competency-based approach. If variable competence was not acceptable then, why should it be now? The goal of CBTVT is not shorter training, but rather flexible, individualized training both in terms of content and duration. While this also means some learners may need to extend their training, this should already be part of GME programs that are required to have remediation policies for learners who are not progressing as expected.

AN OPPORTUNITY FOR PHM

Time variability is an oft-cited tenet of CBME,2,3 but one that is being piloted by relatively few programs in the United States, mostly in undergraduate medical education (UME).14-16 The Education in Pediatrics Across the Continuum (EPAC), a consortium consisting of four institutions piloting CBTVT in UME,14 has shown early evidence of feasibility17 and that UME graduates from CBTVT programs enter residency with levels of competence similar to those of graduates of traditional time-based programs.18 We believe that PHM can take a step toward truly realizing CBME by implementing CBTVT in fellowship programs.

There are multiple reasons why this is an opportune time for PHM fellowships to consider CBTVT. First, PHM is a relatively new board-certified subspecialty with a recently revised set of core competencies1 that are likely to catalyze programmatic innovation. A key step in change management is building on previous efforts to generate more change.19 Programs can leverage the momentum from current and impending change initiatives to innovate and implement CBTVT. Second, the revised PHM competencies provide the first crucial step in implementing a CBME program by defining desired training outcomes necessary to deliver high-quality patient care. With PHM competencies now well defined, programs can focus on developing programs of assessment and corresponding faculty development, which can help deliver valid, defensible decisions about fellow competence.

Finally, PHM has a workforce that can support CBTVT. A major barrier to time-variable training in GME is the need for trainees-as-workforce. In many GME programs, residents and fellows provide a relatively inexpensive, renewable workforce. Trainees’ clinical rotations are often scheduled up to 1 year in advance to ensure care teams are fully staffed, particularly in the inpatient setting, creating a system where flexibility in training is impossible without creating gaps in clinical coverage. However, many PHM fellowships do not completely rely on fellows to cover clinical service lines. PHM fellows spend 32 weeks over 2 years in core clinical rotations with faculty supervision, in accordance with the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education program requirements, both for 2- and 3-year programs. Some CBME experts estimate (based on previous and ongoing CBTVT pilots) that training duration is likely to vary by roughly 20% from current time-based practices when CBTVT is initially implemented.20 Thus, only a small number of clinical service weeks are likely to be affected. If a fellow were deemed ready for unsupervised practice before finishing 2 years of fellowship in a CBTVT program, the corresponding faculty supervisor could use the time previously assigned for supervision to pursue other priorities, such as education, scholarship, or quality improvement. Why provide supervision if a clinical competency committee has deemed a fellow ready for unsupervised practice? Some level of observation and formative feedback could continue, but full supervision would be redundant and unnecessary. CBTVT would allow for some fellows to experience the uncertainty that comes with unsupervised decision-making while still in an environment with trusted fellowship mentors and advisors.

STEPS TOWARD CHANGE

PHM fellowship programs likely cannot flip a switch to “turn on” CBTVT immediately, but they can take steps toward making the transition. Validity, or defensibility of decisions, will be crucial for assessment in CBTVT systems. Programs will need to develop robust assessment systems that collect myriad data to answer the question, “When is this learner competent to deliver high-quality care without supervision?” Programs can align assessment instruments, faculty-development initiatives, and clinical competency committee (CCC) processes with the 2020 PHM competencies to provide a defensible answer. Program leaders should then seek validity evidence, either in existing literature or through novel scholarly initiatives, to support these summative decisions. Engaging all fellowship stakeholders in transitions to CBTVT will be important and should include fellows, program directors, CCC members, clinical leadership, and members from accrediting and credentialing bodies.

CONCLUSION

As fellowship programs review and revise curricula and assessment systems around the updated PHM core competencies, they should also consider what changes are necessary to implement CBTVT. Time variability is not a novelty but, rather, is a corollary to the outcomes-based approach of CBME. PHM fellowships should strike while the iron is hot and build on current change initiatives prompted by the growth of our specialty to be leaders in CBTVT.

1. Maniscalco J, Gage S, Sofia Teferi M, Fisher ES. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies: 2020 Revision. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(7):389-394. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3391

2. Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):638-645. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.501190

3. Lucey CR, Thibault GE, Ten Cate O. Competency-based, tme-variable education in the health professions: crossroads. Acad Med. 2018;93(3S Competency-Based, Time-Variable Education in the Health Professions):S1-S5. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002080

4. Custers EJFM, Ten Cate O. The history of medical education in Europe and the United States, with respect to time and proficiency. Acad Med. 2018;93(3S Competency-Based, Time-Variable Education in the Health Professions):S49-S54. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002079

5. Barr DA. Revolution or evolution? Putting the Flexner Report in context. Med Educ. 2011;45(1):17-22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03850.x

6. Association of American Medical Colleges. Minutes of the Fifteenth Annual Meeting. April 10, 1905; Chicago, IL.

7. Bevan A. Council on Medical Education of the American Medical Association. JAMA. 1907;48(20):1701-1707.

8. Flexner A. Medical education in the United States and Canada. From the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, Bulletin Number Four, 1910. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80(7):594-602.

9. McGaghie WC, Sajid AW, Miller GE, et al. Competency-based curriculum development in medical education: an introduction. Public Health Pap. 1978;(68):11-91.

10. Frank JR, Snell L, Englander R, Holmboe ES, ICBME Collaborators. Implementing competency-based medical education: moving forward. Med Teach. 2017;39(6):568-573. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1315069

11. Schumacher DJ, West DC, Schwartz A, et al. Longitudinal assessment of resident performance using entrustable professional activities. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1):e1919316. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.19316

12. Warm EJ, Held J, Hellman M, et al. Entrusting observable practice activities and milestones over the 36 months of an internal medicine residency. Acad Med. 2016;91(10):1398-1405. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001292

13. Jason H. Effective medical instruction: requirements and possibilities. In: Proceedings of a 1969 International Symposium on Medical Education. Medica; 1970:5-8.

14. Andrews JS, Bale JF Jr, Soep JB, et al. Education in Pediatrics Across the Continuum (EPAC): first steps toward realizing the dream of competency-based education. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):414-420. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002020

15. Mejicano GC, Bumsted TN. Describing the journey and lessons learned implementing a competency-based, time-variable undergraduate medical education curriculum. Acad Med. 2018;93(3S Competency-Based, Time-Variable Education in the Health Professions):S42-S48. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002068

16. Goldhamer MEJ, Pusic MV, Co JPT, Weinstein DF. Can COVID catalyze an educational transformation? Competency-based advancement in a crisis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(11):1003-1005. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2018570

17. Murray KE, Lane JL, Carraccio C, et al. Crossing the gap: using competency-based assessment to determine whether learners are ready for the undergraduate-to-graduate transition. Acad Med. 2019;94(3):338-345. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002535

18. Schwartz A, Balmer DF, Borman-Shoap E, et al. Shared mental models among clinical competency committees in the context of time-variable, competency-based advancement to residency. Acad Med. 2020;95(11S Association of American Medical Colleges Learn Serve Lead: Proceedings of the 59th Annual Research in Medical Education Presentations):S95-S102. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003638

19. Kotter JP. Leading change: why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Business Review. May-June 1995. Accessed March 1, 2021. https://hbr.org/1995/05/leading-change-why-transformation-efforts-fail-2

20. Schumacher DJ, Caretta-Weyer H, Busari J, et al. Competency-based time-variable training internationally: ensuring practical next steps. Med Teach. Forthcoming.

1. Maniscalco J, Gage S, Sofia Teferi M, Fisher ES. The Pediatric Hospital Medicine Core Competencies: 2020 Revision. J Hosp Med. 2020;15(7):389-394. https://doi.org/10.12788/jhm.3391

2. Frank JR, Snell LS, Cate OT, et al. Competency-based medical education: theory to practice. Med Teach. 2010;32(8):638-645. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.501190

3. Lucey CR, Thibault GE, Ten Cate O. Competency-based, tme-variable education in the health professions: crossroads. Acad Med. 2018;93(3S Competency-Based, Time-Variable Education in the Health Professions):S1-S5. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002080

4. Custers EJFM, Ten Cate O. The history of medical education in Europe and the United States, with respect to time and proficiency. Acad Med. 2018;93(3S Competency-Based, Time-Variable Education in the Health Professions):S49-S54. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002079

5. Barr DA. Revolution or evolution? Putting the Flexner Report in context. Med Educ. 2011;45(1):17-22. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03850.x

6. Association of American Medical Colleges. Minutes of the Fifteenth Annual Meeting. April 10, 1905; Chicago, IL.

7. Bevan A. Council on Medical Education of the American Medical Association. JAMA. 1907;48(20):1701-1707.

8. Flexner A. Medical education in the United States and Canada. From the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, Bulletin Number Four, 1910. Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80(7):594-602.

9. McGaghie WC, Sajid AW, Miller GE, et al. Competency-based curriculum development in medical education: an introduction. Public Health Pap. 1978;(68):11-91.

10. Frank JR, Snell L, Englander R, Holmboe ES, ICBME Collaborators. Implementing competency-based medical education: moving forward. Med Teach. 2017;39(6):568-573. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1315069

11. Schumacher DJ, West DC, Schwartz A, et al. Longitudinal assessment of resident performance using entrustable professional activities. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(1):e1919316. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.19316

12. Warm EJ, Held J, Hellman M, et al. Entrusting observable practice activities and milestones over the 36 months of an internal medicine residency. Acad Med. 2016;91(10):1398-1405. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001292

13. Jason H. Effective medical instruction: requirements and possibilities. In: Proceedings of a 1969 International Symposium on Medical Education. Medica; 1970:5-8.

14. Andrews JS, Bale JF Jr, Soep JB, et al. Education in Pediatrics Across the Continuum (EPAC): first steps toward realizing the dream of competency-based education. Acad Med. 2018;93(3):414-420. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002020

15. Mejicano GC, Bumsted TN. Describing the journey and lessons learned implementing a competency-based, time-variable undergraduate medical education curriculum. Acad Med. 2018;93(3S Competency-Based, Time-Variable Education in the Health Professions):S42-S48. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002068

16. Goldhamer MEJ, Pusic MV, Co JPT, Weinstein DF. Can COVID catalyze an educational transformation? Competency-based advancement in a crisis. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(11):1003-1005. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2018570

17. Murray KE, Lane JL, Carraccio C, et al. Crossing the gap: using competency-based assessment to determine whether learners are ready for the undergraduate-to-graduate transition. Acad Med. 2019;94(3):338-345. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002535

18. Schwartz A, Balmer DF, Borman-Shoap E, et al. Shared mental models among clinical competency committees in the context of time-variable, competency-based advancement to residency. Acad Med. 2020;95(11S Association of American Medical Colleges Learn Serve Lead: Proceedings of the 59th Annual Research in Medical Education Presentations):S95-S102. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000003638

19. Kotter JP. Leading change: why transformation efforts fail. Harvard Business Review. May-June 1995. Accessed March 1, 2021. https://hbr.org/1995/05/leading-change-why-transformation-efforts-fail-2

20. Schumacher DJ, Caretta-Weyer H, Busari J, et al. Competency-based time-variable training internationally: ensuring practical next steps. Med Teach. Forthcoming.

© 2021 Society of Hospital Medicine

Clinical Progress Note: Procalcitonin in the Identification of Invasive Bacterial Infections in Febrile Young Infants

Febrile infants 60 days of age or younger pose a significant diagnostic challenge for clinicians. Most of these infants are well appearing and do not have localizing signs or symptoms of infection, yet they may have serious bacterial infections (SBI) such as urinary tract infection (UTI), bacteremia, and meningitis. While urinalysis is highly sensitive for predicting UTI,1 older clinical decision rules and biomarkers such as white blood cell (WBC) count, absolute neutrophil count (ANC), and C-reactive protein (CRP) lack both appropriate sensitivity and specificity for identifying bacteremia and meningitis (ie, invasive bacterial infection [IBI]),2,3 which affect approximately 2.4% and 0.9% of febrile infants during the first 2 months of life, respectively.4 The lack of accurate diagnostic markers can drive overuse of laboratory testing, antibiotics, and hospitalization despite the low rates of these infections. As a result, procalcitonin (PCT) has generated interest because of its potential to serve as a more accurate biomarker for bacterial infections. This review summarizes recent literature on the diagnostic utility of PCT in the identification of IBI in febrile young infants 60 days or younger.

MECHANISM OF PROCALCITONIN

Procalcitonin is undetectable in noninflammatory states but can be detected in the blood within 4 to 6 hours after initial bacterial infection.5 Its production is stimulated throughout various tissues of the body by cytokines such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor, which are produced in response to bacterial infections. Interferon-γ, which is produced in response to viral infections, attenuates PCT production. While these characteristics suggest promise for PCT as a more specific screening test for underlying bacterial infection, there are caveats. PCT levels are physiologically elevated in the first 48 hours of life and vary with gestational age, factors that should be considered when interpreting results.6 Additionally, PCT levels can rise in other inflammatory states such as autoimmune conditions and certain malignancies,5 though these states are unlikely to confound the evaluation of febrile young infants.

DIAGNOSTIC ACCURACY OF PROCALCITONIN

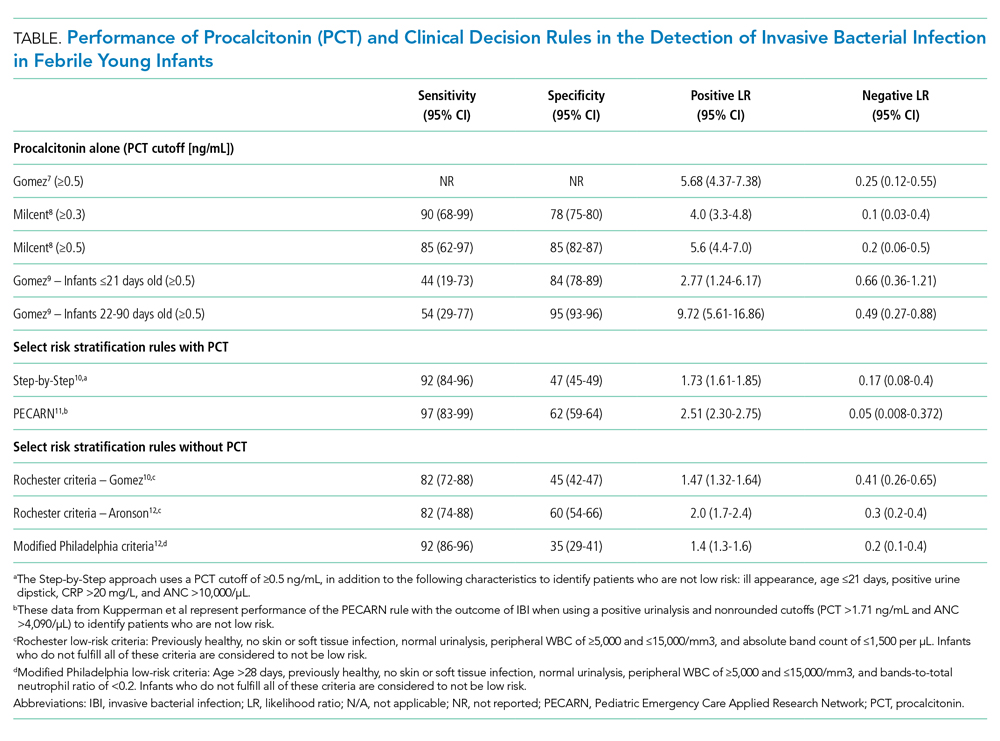

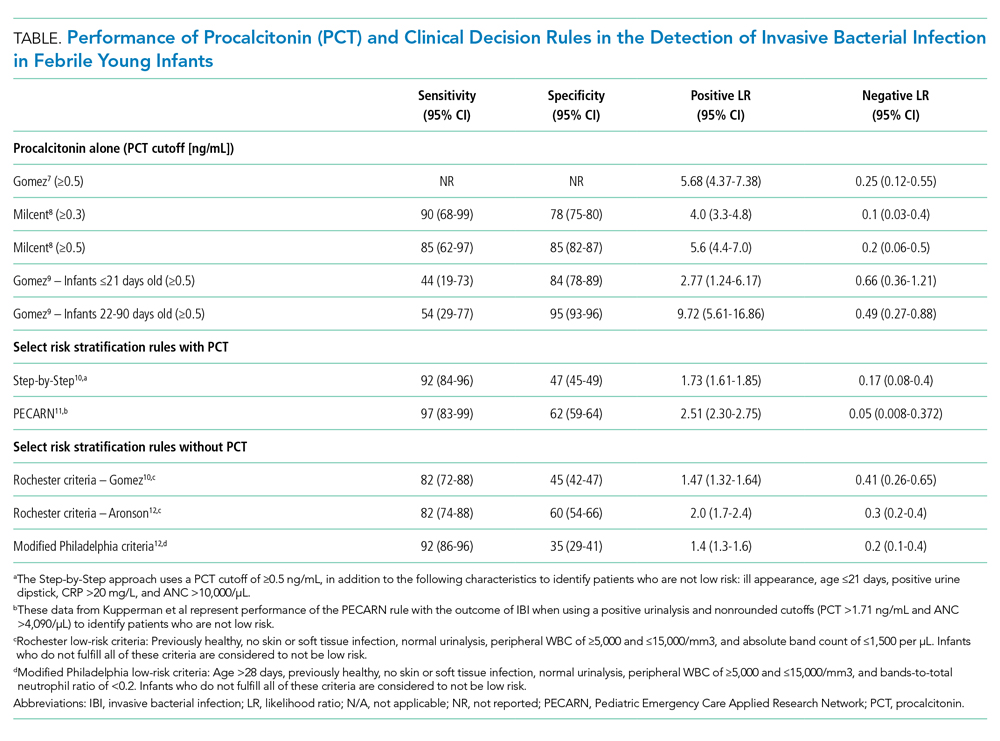

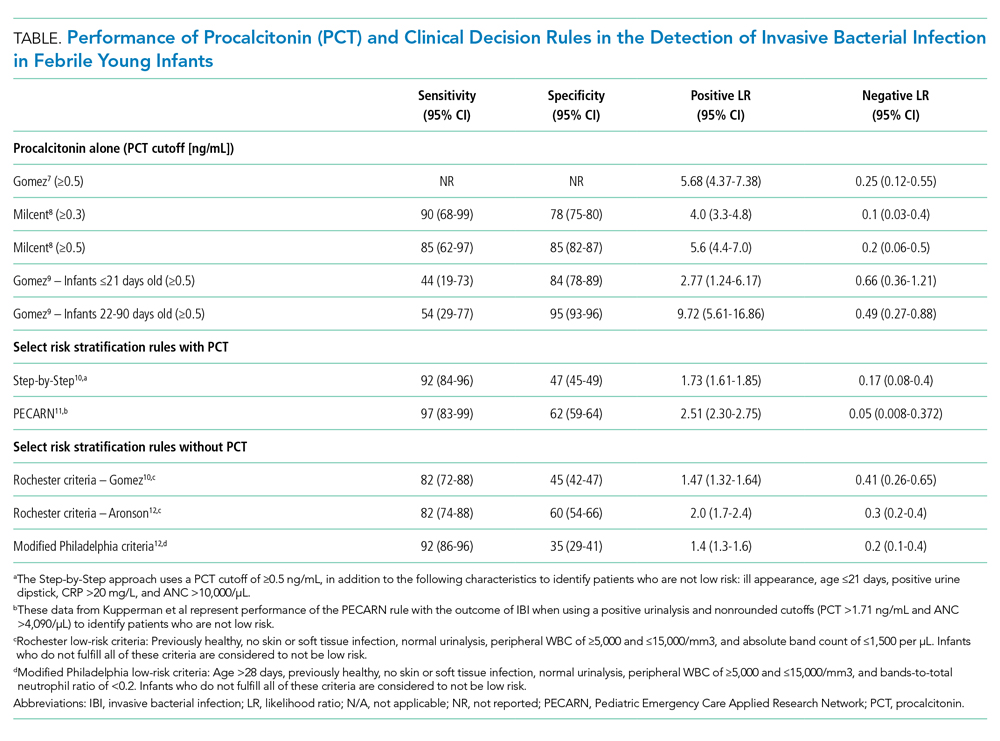

Because of PCT’s potential to be more specific than other commonly used biomarkers, multiple studies have evaluated its performance characteristics in febrile young infants. Gomez et al retrospectively evaluated 1,112 well-appearing infants younger than 3 months with fever without a source in seven European emergency departments (EDs).7 Overall, 23 infants (2.1%) had IBI (1 with meningitis). A PCT level of 0.5 ng/mL or greater was the only independent risk factor for IBI (adjusted odds ratio, 21.69; 95% CI, 7.93-59.28). Four infants with IBI had a PCT level less than 0.5 ng/mL, and none of these four had meningitis. PCT was superior to CRP, ANC, and WBC in detecting IBI (area under the curve [AUC], 0.825; 95% CI, 0.698-0.952). PCT was the also the best marker for identifying IBI among 451 infants with a normal urine dipstick and fever detected ≤6 hours before presentation (AUC, 0.819; 95% CI, 0.551-1.087).

In the largest prospective study to date evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of PCT in febrile young infants, Milcent et al studied 2,047 previously healthy infants aged 7-91 days admitted for fever from 15 French EDs.8 In total, 21 (1%) had an IBI (8 with meningitis). PCT performed better than CRP, ANC, and WBC for the detection of IBI with an AUC of 0.91 (95% CI, 0.83-0.99). In a multivariable model, a PCT level of 0.3 ng/mL or greater was the only independent risk factor for IBI with an adjusted odds ratio of 40.3 (95% CI, 5.0-332). Only one infant with IBI had a PCT level less than 0.3 ng/mL. This infant was 83 days old, had 4 hours of fever, and became afebrile spontaneously prior to the blood culture revealing Streptococcus pneumoniae. PCT also performed better than CRP in the detection of IBI in infants 7-30 days of age and those with fever for less than 6 hours, though both subgroups had small numbers of infants with IBI. The authors determined that a PCT level of 0.3 ng/mL was the optimal cutoff for ruling out IBI; this cutoff had a sensitivity of 90% and negative likelihood ratio (LR) of 0.1 (Table). In contrast, the more commonly studied PCT cutoff of 0.5 ng/mL increased the negative LR to 0.2. The authors suggested that PCT, when used in the context of history, exam, and tests such as urinalysis, could identify infants at low risk of IBI.

Gomez et al conducted a prospective, single-center study of well-appearing infants with fever without a source and negative urine dipsticks.9 They identified IBI in 9 of 196 infants (4.5%) 21 days or younger and 13 of 1,331 infants (1.0%) 22-90 days old. PCT was superior to CRP and ANC for IBI detection in both age groups. However, in infants 21 days or younger, both the positive and negative LRs for PCT levels of 0.5 ng/mL or greater were poor (Table). Differences in results from the prior two studies7,8 may be related to smaller sample size and differences in patient population because this study included infants younger than 7 days and a higher proportion of infants presenting within 6 hours of fever.

CLINICAL DECISION RULES

PCT has also been incorporated into clinical decision rules for febrile young infants, primarily to identify those at low risk of either IBI or SBI. The Step-by-Step approach10 classified well-appearing febrile infants 90 days or younger as having a high risk of IBI if they were ill appearing, younger than 21 days old, had a positive urine dipstick or a PCT level of 0.5 ng/mL or greater, and classified them as intermediate risk if they had a CRP level greater than 20 mg/L or ANC level greater than 10,000/µL. The remaining infants were classified as low risk and could be managed as outpatients without lumbar puncture or empiric antibiotics. Of note, derivation of this rule excluded patients with respiratory signs or symptoms. In a prospective validation study with 2,185 infants from 11 European EDs, 87 (4.0%) had an IBI (10 with bacterial meningitis). Sequentially identifying patients as high risk using general appearance, age, and urine dipstick alone identified 80% of infants with IBI and 90% of those with bacterial meningitis. The remaining case of meningitis would have been detected by an elevated PCT. A total of 7 of 991 infants (0.7%) classified as low risk had an IBI and none had meningitis. Six of these infants had a fever duration of less than 2 hours, which would not be enough time for PCT to rise. The Step-by-Step approach, with a sensitivity of 92% and negative LR of 0.17, performed well in the ability to rule out IBI.

A clinical prediction rule developed by the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) found that urinalysis, ANC, and PCT performed well in identifying infants 60 days or younger at low risk for SBI and IBI.11 This prospective observational study of 1,821 infants 60 days or younger in 26 US EDs found 170 (9.3%) with SBI and 30 (1.6%) with IBI; 10 had bacterial meningitis. Only one patient with IBI was classified as low risk, a 30-day-old whose blood culture grew Enterobacter cloacae and who had a negative repeat blood culture prior to antibiotic treatment. Together, a negative urinalysis, ANC of 4,090/µL or less, and PCT level of 1.71 ng/mL or less were excellent in predicting infants at low risk for both SBI and IBI, with a sensitivity of 97% and negative LR of 0.05 for the outcome of IBI. When applying these variables with “rounded cutoffs” of PCT levels less than 0.5 ng/mL (chosen by the authors because it is a more commonly used cutoff) and ANC of 4,000/µL or less to identify infants at low risk for SBI, their performance was similar to nonrounded cutoffs. Data for the rule with rounded cutoffs in identifying infants at low risk for IBI were not presented. The PECARN study was limited by the small numbers of infants with IBIs, and the authors recommended caution when applying the rule to infants 28 days or younger.

Older clinical decision rules without PCT, such as the Rochester and modified Philadelphia criteria, use clinical and laboratory features to assess risk of IBI.3 Recent studies have evaluated these criteria in cohorts with larger numbers of infants with IBI since the derivation studies included mostly infants with SBI and small numbers with IBI.3 Gomez et al demonstrated that the Rochester criteria had lower sensitivity and higher negative LR than the Step-by-Step approach in IBI detection.10 In a case-control study of 135 cases of IBI with 249 matched controls, Aronson et al reported that the modified Philadelphia criteria had higher sensitivity but lower specificity than the Rochester criteria for IBI detection.12 The ability of the Rochester and modified Philadelphia criteria to rule out IBI, as demonstrated by the negative LR (range 0.2-0.4), was inferior to the negative LRs documented by Milcent et al8 (PCT cutoff value of 0.3 ng/mL), the Step-by-Step approach,10 and the PECARN rule11 (range 0.05-0.17; Table). However, clinical decision rules with and without PCT suffer similar limitations in having poor specificity in identifying infants likely to have IBI.

GAPS IN THE LITERATURE

Several key knowledge gaps around PCT use for diagnosing neonatal infections exist. First, the optimal use of PCT in context with other biomarkers and clinical decision rules remains uncertain. A meta-analysis of 28 studies involving over 2,600 infants that compared PCT level (with and without CRP) with isolated CRP and presepsin levels found that PCT in combination with CRP had greater diagnostic accuracy than either PCT or CRP alone, which highlights a potential opportunity for prospective study.13 Second, more data are needed on the use of PCT in the ≤ 28-day age group given the increased risk of both IBI and neonatal herpes simplex virus infection (HSV), compared with that in the second month of life. Neonatal HSV poses diagnostic challenges because half of infants will initially present as afebrile,14 and delays in initiating antiviral treatment dramatically increase the risk of permanent disability or death.15 There have been no prospective studies evaluating PCT use as part of neonatal HSV evaluations.

CLINICAL APPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

In summary, PCT can play an important adjunctive diagnostic role in the evaluation of febrile young infants, especially during the second month of life when outpatient management is more likely to be considered. PCT is superior to other inflammatory markers in identifying IBI, though the optimal cutoffs to maximize sensitivity and specificity are uncertain. Its performance characteristics, both alone and within clinical decision rules, can help clinicians better identify children at low risk for IBI when compared with clinical decision rules without PCT. PCT measurement can help clinicians miss fewer infants with IBI and identify infants for whom safely doing less is an appropriate option, which can ultimately reduce costs and hospitalizations. PCT may be particularly helpful when the clinical history is difficult to assess or when other diagnostic test results are missing or give conflicting results. Centers that use PCT will need to ensure that results are available within a short turnaround time (a few hours) in order to meaningfully affect care. Future studies of PCT in febrile infant evaluations should focus on identifying optimal strategies for incorporating this biomarker into risk assessments that present information to parents in a way that enables them to understand their child’s risk of a serious infection.

1. Tzimenatos L, Mahajan P, Dayan PS, et al. Accuracy of the urinalysis for urinary tract infections in febrile infants 60 days and younger. Pediatrics. 2018;141(2):e20173068. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-3068

2. Cruz AT, Mahajan P, Bonsu BK, et al. Accuracy of complete blood cell counts to identify febrile infants 60 days or younger with invasive bacterial infections. JAMA Pediatr. 2017;171(11):e172927. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2017.2927

3. Hui C, Neto G, Tsertsvadze A, et al. Diagnosis and management of febrile infants (0-3 months). Evid Rep Technol Assess (Full Rep). 2012;(205):1-297.

4. Biondi EA, Lee B, Ralston SL, et al. Prevalence of bacteremia and bacterial meningitis in febrile neonates and infants in the second month of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(3):e190874. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.0874

5. Fontela PS, Lacroix J. Procalcitonin: is this the promised biomarker for critically ill patients? J Pediatr Intensive Care. 2016;5(4):162-171. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0036-1583279

6. Chiesa C, Natale F, Pascone R, et al. C reactive protein and procalcitonin: reference intervals for preterm and term newborns during the early neonatal period. Clin Chim Acta. 2011;412(11-12):1053-1059. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cca.2011.02.020

7. Gomez B, Bressan S, Mintegi S, et al. Diagnostic value of procalcitonin in well-appearing young febrile infants. Pediatrics. 2012;130(5):815-822. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2011-3575

8. Milcent K, Faesch S, Gras-Le Guen C, et al. Use of procalcitonin assays to predict serious bacterial infection in young febrile infants. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(1):62-69. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3210

9. Gomez B, Diaz H, Carro A, Benito J, Mintegi S. Performance of blood biomarkers to rule out invasive bacterial infection in febrile infants under 21 days old. Arch Dis Child. 2019;104(6):547-551. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2018-315397

10. Gomez B, Mintegi S, Bressan S, et al. Validation of the “step-by-step” approach in the management of young febrile infants. Pediatrics. 2016;138(2):e20154381. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-4381

11. Kuppermann N, Dayan PS, Levine DA, et al. A clinical prediction rule to identify febrile infants 60 days and younger at low risk for serious bacterial infections. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173(4):342-351. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapediatrics.2018.5501

12. Aronson PL, Wang ME, Shapiro ED, et al. Risk stratification of febrile infants ≤60 days old without routine lumbar puncture. Pediatrics. 2018;142(6):e20181879. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-1879

13. Ruan L, Chen GY, Liu Z, et al. The combination of procalcitonin and C-reactive protein or presepsin alone improves the accuracy of diagnosis of neonatal sepsis: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Crit Care. 2018;22(1):316. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13054-018-2236-1

14. Brower L, Schondelmeyer A, Wilson P, Shah SS. Testing and empiric treatment for neonatal herpes simplex virus: challenges and opportunities for improving the value of care. Hosp Pediatr. 2016;6(2):108-111. https://doi.org/10.1542/hpeds.2015-0166

15. Long SS. Delayed acyclovir therapy in neonates with herpes simplex virus infection is associated with an increased odds of death compared with early therapy. Evid Based Med. 2013;18(2):e20. https://doi.org/10.1136/eb-2012-100674

Febrile infants 60 days of age or younger pose a significant diagnostic challenge for clinicians. Most of these infants are well appearing and do not have localizing signs or symptoms of infection, yet they may have serious bacterial infections (SBI) such as urinary tract infection (UTI), bacteremia, and meningitis. While urinalysis is highly sensitive for predicting UTI,1 older clinical decision rules and biomarkers such as white blood cell (WBC) count, absolute neutrophil count (ANC), and C-reactive protein (CRP) lack both appropriate sensitivity and specificity for identifying bacteremia and meningitis (ie, invasive bacterial infection [IBI]),2,3 which affect approximately 2.4% and 0.9% of febrile infants during the first 2 months of life, respectively.4 The lack of accurate diagnostic markers can drive overuse of laboratory testing, antibiotics, and hospitalization despite the low rates of these infections. As a result, procalcitonin (PCT) has generated interest because of its potential to serve as a more accurate biomarker for bacterial infections. This review summarizes recent literature on the diagnostic utility of PCT in the identification of IBI in febrile young infants 60 days or younger.

MECHANISM OF PROCALCITONIN

Procalcitonin is undetectable in noninflammatory states but can be detected in the blood within 4 to 6 hours after initial bacterial infection.5 Its production is stimulated throughout various tissues of the body by cytokines such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor, which are produced in response to bacterial infections. Interferon-γ, which is produced in response to viral infections, attenuates PCT production. While these characteristics suggest promise for PCT as a more specific screening test for underlying bacterial infection, there are caveats. PCT levels are physiologically elevated in the first 48 hours of life and vary with gestational age, factors that should be considered when interpreting results.6 Additionally, PCT levels can rise in other inflammatory states such as autoimmune conditions and certain malignancies,5 though these states are unlikely to confound the evaluation of febrile young infants.

DIAGNOSTIC ACCURACY OF PROCALCITONIN

Because of PCT’s potential to be more specific than other commonly used biomarkers, multiple studies have evaluated its performance characteristics in febrile young infants. Gomez et al retrospectively evaluated 1,112 well-appearing infants younger than 3 months with fever without a source in seven European emergency departments (EDs).7 Overall, 23 infants (2.1%) had IBI (1 with meningitis). A PCT level of 0.5 ng/mL or greater was the only independent risk factor for IBI (adjusted odds ratio, 21.69; 95% CI, 7.93-59.28). Four infants with IBI had a PCT level less than 0.5 ng/mL, and none of these four had meningitis. PCT was superior to CRP, ANC, and WBC in detecting IBI (area under the curve [AUC], 0.825; 95% CI, 0.698-0.952). PCT was the also the best marker for identifying IBI among 451 infants with a normal urine dipstick and fever detected ≤6 hours before presentation (AUC, 0.819; 95% CI, 0.551-1.087).

In the largest prospective study to date evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of PCT in febrile young infants, Milcent et al studied 2,047 previously healthy infants aged 7-91 days admitted for fever from 15 French EDs.8 In total, 21 (1%) had an IBI (8 with meningitis). PCT performed better than CRP, ANC, and WBC for the detection of IBI with an AUC of 0.91 (95% CI, 0.83-0.99). In a multivariable model, a PCT level of 0.3 ng/mL or greater was the only independent risk factor for IBI with an adjusted odds ratio of 40.3 (95% CI, 5.0-332). Only one infant with IBI had a PCT level less than 0.3 ng/mL. This infant was 83 days old, had 4 hours of fever, and became afebrile spontaneously prior to the blood culture revealing Streptococcus pneumoniae. PCT also performed better than CRP in the detection of IBI in infants 7-30 days of age and those with fever for less than 6 hours, though both subgroups had small numbers of infants with IBI. The authors determined that a PCT level of 0.3 ng/mL was the optimal cutoff for ruling out IBI; this cutoff had a sensitivity of 90% and negative likelihood ratio (LR) of 0.1 (Table). In contrast, the more commonly studied PCT cutoff of 0.5 ng/mL increased the negative LR to 0.2. The authors suggested that PCT, when used in the context of history, exam, and tests such as urinalysis, could identify infants at low risk of IBI.

Gomez et al conducted a prospective, single-center study of well-appearing infants with fever without a source and negative urine dipsticks.9 They identified IBI in 9 of 196 infants (4.5%) 21 days or younger and 13 of 1,331 infants (1.0%) 22-90 days old. PCT was superior to CRP and ANC for IBI detection in both age groups. However, in infants 21 days or younger, both the positive and negative LRs for PCT levels of 0.5 ng/mL or greater were poor (Table). Differences in results from the prior two studies7,8 may be related to smaller sample size and differences in patient population because this study included infants younger than 7 days and a higher proportion of infants presenting within 6 hours of fever.

CLINICAL DECISION RULES

PCT has also been incorporated into clinical decision rules for febrile young infants, primarily to identify those at low risk of either IBI or SBI. The Step-by-Step approach10 classified well-appearing febrile infants 90 days or younger as having a high risk of IBI if they were ill appearing, younger than 21 days old, had a positive urine dipstick or a PCT level of 0.5 ng/mL or greater, and classified them as intermediate risk if they had a CRP level greater than 20 mg/L or ANC level greater than 10,000/µL. The remaining infants were classified as low risk and could be managed as outpatients without lumbar puncture or empiric antibiotics. Of note, derivation of this rule excluded patients with respiratory signs or symptoms. In a prospective validation study with 2,185 infants from 11 European EDs, 87 (4.0%) had an IBI (10 with bacterial meningitis). Sequentially identifying patients as high risk using general appearance, age, and urine dipstick alone identified 80% of infants with IBI and 90% of those with bacterial meningitis. The remaining case of meningitis would have been detected by an elevated PCT. A total of 7 of 991 infants (0.7%) classified as low risk had an IBI and none had meningitis. Six of these infants had a fever duration of less than 2 hours, which would not be enough time for PCT to rise. The Step-by-Step approach, with a sensitivity of 92% and negative LR of 0.17, performed well in the ability to rule out IBI.

A clinical prediction rule developed by the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) found that urinalysis, ANC, and PCT performed well in identifying infants 60 days or younger at low risk for SBI and IBI.11 This prospective observational study of 1,821 infants 60 days or younger in 26 US EDs found 170 (9.3%) with SBI and 30 (1.6%) with IBI; 10 had bacterial meningitis. Only one patient with IBI was classified as low risk, a 30-day-old whose blood culture grew Enterobacter cloacae and who had a negative repeat blood culture prior to antibiotic treatment. Together, a negative urinalysis, ANC of 4,090/µL or less, and PCT level of 1.71 ng/mL or less were excellent in predicting infants at low risk for both SBI and IBI, with a sensitivity of 97% and negative LR of 0.05 for the outcome of IBI. When applying these variables with “rounded cutoffs” of PCT levels less than 0.5 ng/mL (chosen by the authors because it is a more commonly used cutoff) and ANC of 4,000/µL or less to identify infants at low risk for SBI, their performance was similar to nonrounded cutoffs. Data for the rule with rounded cutoffs in identifying infants at low risk for IBI were not presented. The PECARN study was limited by the small numbers of infants with IBIs, and the authors recommended caution when applying the rule to infants 28 days or younger.

Older clinical decision rules without PCT, such as the Rochester and modified Philadelphia criteria, use clinical and laboratory features to assess risk of IBI.3 Recent studies have evaluated these criteria in cohorts with larger numbers of infants with IBI since the derivation studies included mostly infants with SBI and small numbers with IBI.3 Gomez et al demonstrated that the Rochester criteria had lower sensitivity and higher negative LR than the Step-by-Step approach in IBI detection.10 In a case-control study of 135 cases of IBI with 249 matched controls, Aronson et al reported that the modified Philadelphia criteria had higher sensitivity but lower specificity than the Rochester criteria for IBI detection.12 The ability of the Rochester and modified Philadelphia criteria to rule out IBI, as demonstrated by the negative LR (range 0.2-0.4), was inferior to the negative LRs documented by Milcent et al8 (PCT cutoff value of 0.3 ng/mL), the Step-by-Step approach,10 and the PECARN rule11 (range 0.05-0.17; Table). However, clinical decision rules with and without PCT suffer similar limitations in having poor specificity in identifying infants likely to have IBI.

GAPS IN THE LITERATURE

Several key knowledge gaps around PCT use for diagnosing neonatal infections exist. First, the optimal use of PCT in context with other biomarkers and clinical decision rules remains uncertain. A meta-analysis of 28 studies involving over 2,600 infants that compared PCT level (with and without CRP) with isolated CRP and presepsin levels found that PCT in combination with CRP had greater diagnostic accuracy than either PCT or CRP alone, which highlights a potential opportunity for prospective study.13 Second, more data are needed on the use of PCT in the ≤ 28-day age group given the increased risk of both IBI and neonatal herpes simplex virus infection (HSV), compared with that in the second month of life. Neonatal HSV poses diagnostic challenges because half of infants will initially present as afebrile,14 and delays in initiating antiviral treatment dramatically increase the risk of permanent disability or death.15 There have been no prospective studies evaluating PCT use as part of neonatal HSV evaluations.

CLINICAL APPLICATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

In summary, PCT can play an important adjunctive diagnostic role in the evaluation of febrile young infants, especially during the second month of life when outpatient management is more likely to be considered. PCT is superior to other inflammatory markers in identifying IBI, though the optimal cutoffs to maximize sensitivity and specificity are uncertain. Its performance characteristics, both alone and within clinical decision rules, can help clinicians better identify children at low risk for IBI when compared with clinical decision rules without PCT. PCT measurement can help clinicians miss fewer infants with IBI and identify infants for whom safely doing less is an appropriate option, which can ultimately reduce costs and hospitalizations. PCT may be particularly helpful when the clinical history is difficult to assess or when other diagnostic test results are missing or give conflicting results. Centers that use PCT will need to ensure that results are available within a short turnaround time (a few hours) in order to meaningfully affect care. Future studies of PCT in febrile infant evaluations should focus on identifying optimal strategies for incorporating this biomarker into risk assessments that present information to parents in a way that enables them to understand their child’s risk of a serious infection.

Febrile infants 60 days of age or younger pose a significant diagnostic challenge for clinicians. Most of these infants are well appearing and do not have localizing signs or symptoms of infection, yet they may have serious bacterial infections (SBI) such as urinary tract infection (UTI), bacteremia, and meningitis. While urinalysis is highly sensitive for predicting UTI,1 older clinical decision rules and biomarkers such as white blood cell (WBC) count, absolute neutrophil count (ANC), and C-reactive protein (CRP) lack both appropriate sensitivity and specificity for identifying bacteremia and meningitis (ie, invasive bacterial infection [IBI]),2,3 which affect approximately 2.4% and 0.9% of febrile infants during the first 2 months of life, respectively.4 The lack of accurate diagnostic markers can drive overuse of laboratory testing, antibiotics, and hospitalization despite the low rates of these infections. As a result, procalcitonin (PCT) has generated interest because of its potential to serve as a more accurate biomarker for bacterial infections. This review summarizes recent literature on the diagnostic utility of PCT in the identification of IBI in febrile young infants 60 days or younger.

MECHANISM OF PROCALCITONIN

Procalcitonin is undetectable in noninflammatory states but can be detected in the blood within 4 to 6 hours after initial bacterial infection.5 Its production is stimulated throughout various tissues of the body by cytokines such as interleukin-6 and tumor necrosis factor, which are produced in response to bacterial infections. Interferon-γ, which is produced in response to viral infections, attenuates PCT production. While these characteristics suggest promise for PCT as a more specific screening test for underlying bacterial infection, there are caveats. PCT levels are physiologically elevated in the first 48 hours of life and vary with gestational age, factors that should be considered when interpreting results.6 Additionally, PCT levels can rise in other inflammatory states such as autoimmune conditions and certain malignancies,5 though these states are unlikely to confound the evaluation of febrile young infants.

DIAGNOSTIC ACCURACY OF PROCALCITONIN

Because of PCT’s potential to be more specific than other commonly used biomarkers, multiple studies have evaluated its performance characteristics in febrile young infants. Gomez et al retrospectively evaluated 1,112 well-appearing infants younger than 3 months with fever without a source in seven European emergency departments (EDs).7 Overall, 23 infants (2.1%) had IBI (1 with meningitis). A PCT level of 0.5 ng/mL or greater was the only independent risk factor for IBI (adjusted odds ratio, 21.69; 95% CI, 7.93-59.28). Four infants with IBI had a PCT level less than 0.5 ng/mL, and none of these four had meningitis. PCT was superior to CRP, ANC, and WBC in detecting IBI (area under the curve [AUC], 0.825; 95% CI, 0.698-0.952). PCT was the also the best marker for identifying IBI among 451 infants with a normal urine dipstick and fever detected ≤6 hours before presentation (AUC, 0.819; 95% CI, 0.551-1.087).

In the largest prospective study to date evaluating the diagnostic accuracy of PCT in febrile young infants, Milcent et al studied 2,047 previously healthy infants aged 7-91 days admitted for fever from 15 French EDs.8 In total, 21 (1%) had an IBI (8 with meningitis). PCT performed better than CRP, ANC, and WBC for the detection of IBI with an AUC of 0.91 (95% CI, 0.83-0.99). In a multivariable model, a PCT level of 0.3 ng/mL or greater was the only independent risk factor for IBI with an adjusted odds ratio of 40.3 (95% CI, 5.0-332). Only one infant with IBI had a PCT level less than 0.3 ng/mL. This infant was 83 days old, had 4 hours of fever, and became afebrile spontaneously prior to the blood culture revealing Streptococcus pneumoniae. PCT also performed better than CRP in the detection of IBI in infants 7-30 days of age and those with fever for less than 6 hours, though both subgroups had small numbers of infants with IBI. The authors determined that a PCT level of 0.3 ng/mL was the optimal cutoff for ruling out IBI; this cutoff had a sensitivity of 90% and negative likelihood ratio (LR) of 0.1 (Table). In contrast, the more commonly studied PCT cutoff of 0.5 ng/mL increased the negative LR to 0.2. The authors suggested that PCT, when used in the context of history, exam, and tests such as urinalysis, could identify infants at low risk of IBI.

Gomez et al conducted a prospective, single-center study of well-appearing infants with fever without a source and negative urine dipsticks.9 They identified IBI in 9 of 196 infants (4.5%) 21 days or younger and 13 of 1,331 infants (1.0%) 22-90 days old. PCT was superior to CRP and ANC for IBI detection in both age groups. However, in infants 21 days or younger, both the positive and negative LRs for PCT levels of 0.5 ng/mL or greater were poor (Table). Differences in results from the prior two studies7,8 may be related to smaller sample size and differences in patient population because this study included infants younger than 7 days and a higher proportion of infants presenting within 6 hours of fever.

CLINICAL DECISION RULES

PCT has also been incorporated into clinical decision rules for febrile young infants, primarily to identify those at low risk of either IBI or SBI. The Step-by-Step approach10 classified well-appearing febrile infants 90 days or younger as having a high risk of IBI if they were ill appearing, younger than 21 days old, had a positive urine dipstick or a PCT level of 0.5 ng/mL or greater, and classified them as intermediate risk if they had a CRP level greater than 20 mg/L or ANC level greater than 10,000/µL. The remaining infants were classified as low risk and could be managed as outpatients without lumbar puncture or empiric antibiotics. Of note, derivation of this rule excluded patients with respiratory signs or symptoms. In a prospective validation study with 2,185 infants from 11 European EDs, 87 (4.0%) had an IBI (10 with bacterial meningitis). Sequentially identifying patients as high risk using general appearance, age, and urine dipstick alone identified 80% of infants with IBI and 90% of those with bacterial meningitis. The remaining case of meningitis would have been detected by an elevated PCT. A total of 7 of 991 infants (0.7%) classified as low risk had an IBI and none had meningitis. Six of these infants had a fever duration of less than 2 hours, which would not be enough time for PCT to rise. The Step-by-Step approach, with a sensitivity of 92% and negative LR of 0.17, performed well in the ability to rule out IBI.

A clinical prediction rule developed by the Pediatric Emergency Care Applied Research Network (PECARN) found that urinalysis, ANC, and PCT performed well in identifying infants 60 days or younger at low risk for SBI and IBI.11 This prospective observational study of 1,821 infants 60 days or younger in 26 US EDs found 170 (9.3%) with SBI and 30 (1.6%) with IBI; 10 had bacterial meningitis. Only one patient with IBI was classified as low risk, a 30-day-old whose blood culture grew Enterobacter cloacae and who had a negative repeat blood culture prior to antibiotic treatment. Together, a negative urinalysis, ANC of 4,090/µL or less, and PCT level of 1.71 ng/mL or less were excellent in predicting infants at low risk for both SBI and IBI, with a sensitivity of 97% and negative LR of 0.05 for the outcome of IBI. When applying these variables with “rounded cutoffs” of PCT levels less than 0.5 ng/mL (chosen by the authors because it is a more commonly used cutoff) and ANC of 4,000/µL or less to identify infants at low risk for SBI, their performance was similar to nonrounded cutoffs. Data for the rule with rounded cutoffs in identifying infants at low risk for IBI were not presented. The PECARN study was limited by the small numbers of infants with IBIs, and the authors recommended caution when applying the rule to infants 28 days or younger.