User login

How should asymptomatic hypertension be managed in the hospital?

Case

A 62-year-old man with diabetes mellitus and hypertension presents with painful erythema of the left lower extremity and is admitted for purulent cellulitis. During the first evening of admission, he has increased left lower extremity pain and nursing reports a blood pressure of 188/96 mm Hg. He denies dyspnea, chest pain, visual changes, confusion, or severe headache.

Background

The prevalence of hypertension in the outpatient setting in the United States is estimated at 29% by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.1 Hypertension generally is defined in the outpatient setting as an average blood pressure reading greater than or equal to140/90 mm Hg on two or more separate occasions.2 There is no consensus on the definition of hypertension in the inpatient setting; however, hypertensive urgency often is defined as a sustained blood pressure above the range of 180-200 mm Hg systolic and/or 110-120 mm Hg diastolic without target organ damage, and hypertensive emergency has a similar blood pressure range, but with evidence of target organ damage.3

The evidence

There are several clinical trials to suggest that the ambulatory treatment of chronic hypertension reduces the incidence of myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), and heart failure7,8; however, these trials are difficult to extrapolate to acutely hospitalized patients.6 Overall, evidence on the appropriate management of asymptomatic hypertension in the inpatient setting is lacking.

Some evidence suggests we often are overly aggressive with intravenous antihypertensives without clinical indications in the inpatient setting.3,9,10 For example, Campbell et al. prospectively examined the use of intravenous hydralazine for the treatment of asymptomatic hypertension in 94 hospitalized patients.10 It was determined that in 90 of those patients, there was no clinical indication to use intravenous hydralazine and 17 patients experienced adverse events from hypotension, which included dizziness/light-headedness, syncope, and chest pain.10 They recommend against the use of intravenous hydralazine in the setting of asymptomatic hypertension because of its risk of adverse events with the rapid lowering of blood pressure.10

Weder and Erickson performed a retrospective review on the use of intravenous hydralazine and labetalol administration in 2,189 hospitalized patients.3 They found that only 3% of those patients had symptoms indicating the need for IV antihypertensives and that the length of stay was several days longer in those who had received IV antihypertensives.3

Other studies have examined the role of oral antihypertensives for management of asymptomatic hypertension in the inpatient setting. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Souza et al. assessed the use of oral pharmacotherapy for hypertensive urgency.11 Sixteen randomized clinical trials were reviewed and it was determined that angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) had a superior effect in treating hypertensive urgencies.11 The most common side effect of using an ACE-I was a bad taste in patient’s mouths, and researchers did not observe side effects that were similar as those seen with the use of IV antihypertensives.11

Further, Jaker et al. performed a randomized, double-blind prospective study comparing a single dose of oral nifedipine with oral clonidine for the treatment of hypertensive urgency in 51 patients.12 Both the oral nifedipine and oral clonidine were extremely effective in reducing blood pressure fairly safely.12 However, the rapid lowering of blood pressure with oral nifedipine was concerning to Grossman et al.13 In their literature review of the side effects of oral and sublingual nifedipine, they found that it was one of the most common therapeutic interventions for hypertensive urgency or emergency.13 However, it was potentially dangerous because of the inconsistent blood pressure response after nifedipine administration, particularly with the sublingual form.13 CVAs, acute MIs, and even death were the reported adverse events with the use of oral and sublingual nifedipine.13 Because of that, the investigators recommend against the use of oral or sublingual nifedipine in hypertensive urgency or emergency and suggest using other oral antihypertensive agents instead.13

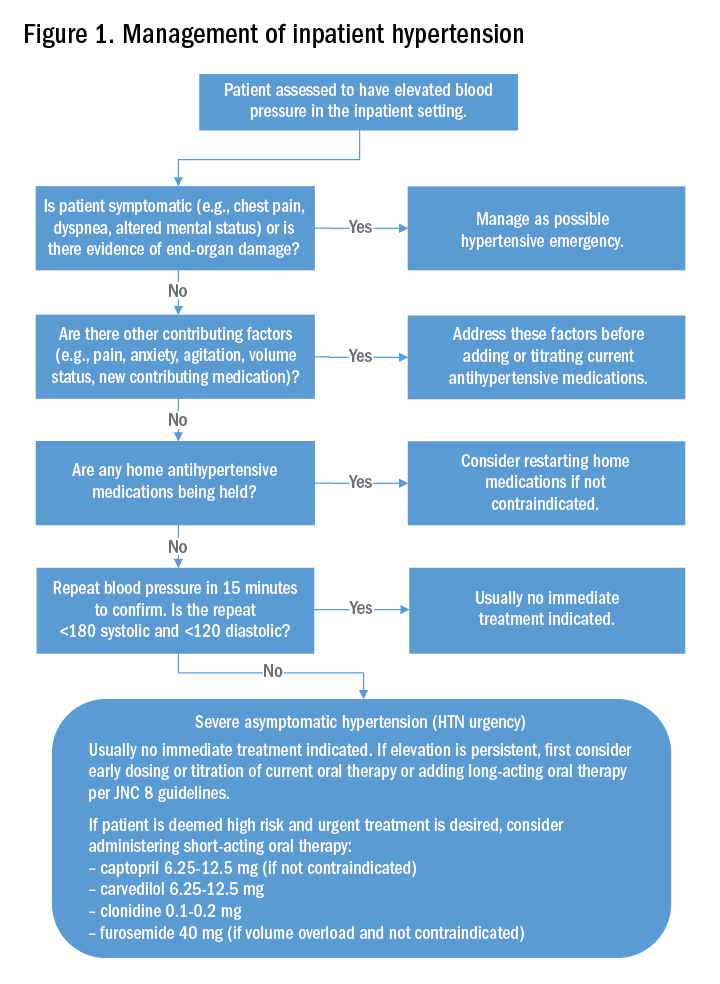

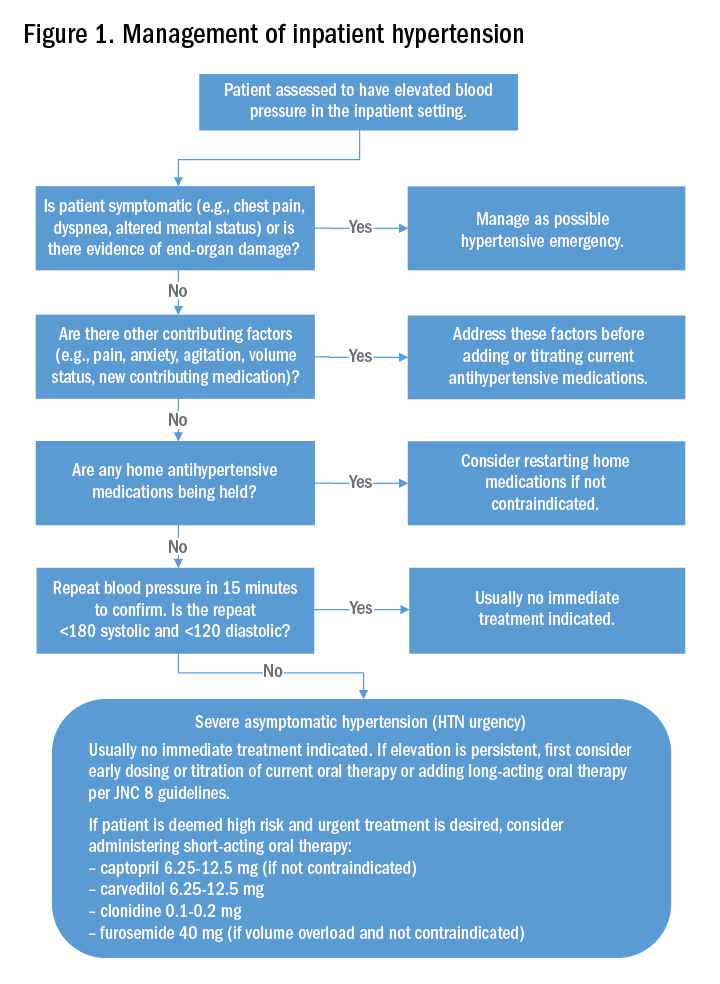

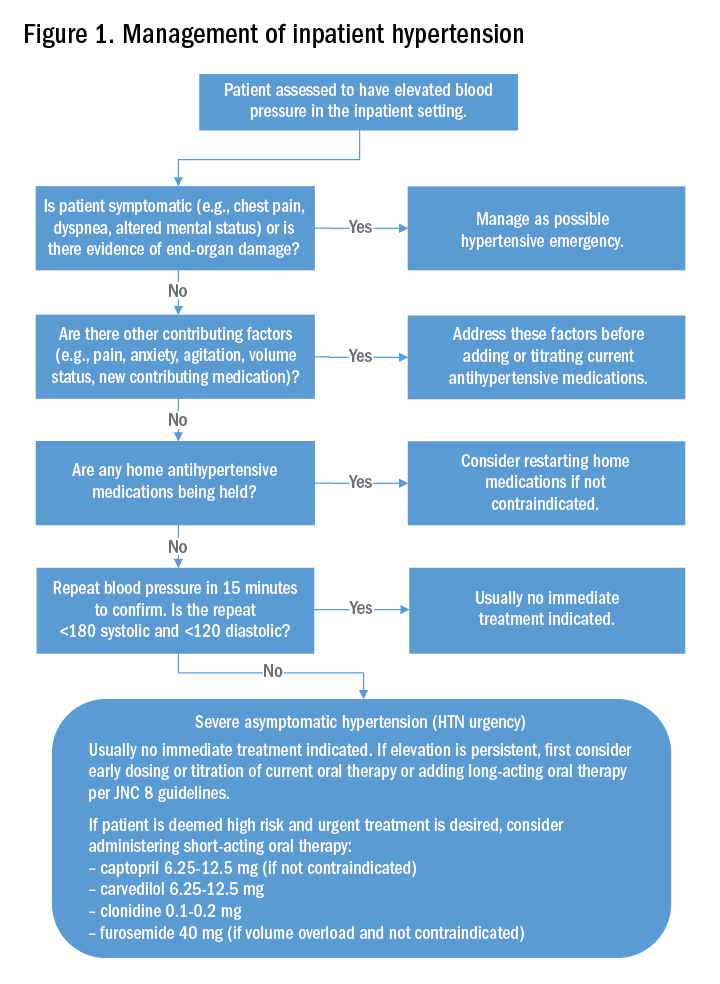

Typically, if the patient’s blood pressure remains elevated despite these efforts, no urgent treatment is indicated and we recommend close monitoring of the patient’s blood pressure during the hospitalization. If hypertension persists, the next best step would be to titrate a patient’s current oral antihypertensive therapy or to start a long-acting antihypertensive therapy per the JNC 8 (Eighth Joint National Committee) guidelines. It should be noted that, in those patients that are high risk, such as those with known coronary artery disease, heart failure, or prior hemorrhagic CVA, a short-acting oral antihypertensive such as captopril, carvedilol, clonidine, or furosemide should be considered.

Back to the case

The patient’s pain was treated with oral oxycodone. He received no oral or intravenous antihypertensive therapy, and the following morning, his blood pressure improved to 145/95 mm Hg. Based on our suggested approach in Fig. 1, the patient would require no acute treatment despite an improved but elevated blood pressure. We continued to monitor his blood pressure and despite adequate pain control, his blood pressure remain persistently elevated. Thus, per the JNC 8 guidelines, we started him on a long-acting antihypertensive, which improved his blood pressure to 123/78 at the time of discharge.

Bottom line

Management of asymptomatic hypertension in the hospital begins with addressing contributing factors, reviewing held home medications – and rarely – urgent oral pharmacotherapy.

Dr. Lippert is PGY-3 in the department of internal medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Bailey is associate professor of medicine at the University of Kentucky. Dr. Gray is associate professor of medicine at the University of Kentucky.

References

1. Yoon S, Fryar C, Carroll M. Hypertension prevalence and control among adults: United States, 2011-2014. 2015. Accessed Oct 2, 2017.

2. Poulter NR, Prabhakaran D, Caulfield M. Hypertension. Lancet. 2015;386(9995):801-12.

3. Weder AB, Erickson S. Treatment of hypertension in the inpatient setting: Use of intravenous labetalol and hydralazine. J Clin Hypertens. 2010;12(1):29-33.

4. Axon RN, Cousineau L, Egan BM. Prevalence and management of hypertension in the inpatient setting: A systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(7):417-22.

5. Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of hospital stays in the United States, 2012. Statistical brief; 2014 Oct. Accessed Oct 2, 2017.

6. Weder AB. Treating acute hypertension in the hospital: a Lacuna in the guidelines. Hypertension. 2011;57(1):18-20.

7. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension and of the European Society of Cardiology. J Hypertens. 2013 Jul;31(7):1281-357.

8. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-20.

9. Lipari M, Moser LR, Petrovitch EA, et al. As-needed intravenous antihypertensive therapy and blood pressure control. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(3):193-8.

10. Campbell P, Baker WL, Bendel SD, et al. Intravenous hydralazine for blood pressure management in the hospitalized patient: Its use is often unjustified. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2011;5(6):473-7.

11. Souza LM, Riera R, Saconato H, et al. Oral drugs for hypertensive urgencies: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Sao Paulo Med J. 2009;127(6):366-72.

12. Jaker M, Atkin S, Soto M, et al. Oral nifedipine vs. oral clonidine in the treatment of urgent hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149(2):260-5.

13. Grossman E, Messerli FH, Grodzicki T, et al. Should a moratorium be placed on sublingual nifedipine capsules given for hypertensive emergencies and pseudoemergencies? JAMA. 1996;276(16):1328-31.

14. Axon RN, Turner M, Buckley R. An update on inpatient hypertension management. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015;17(11):94.

Additional Reading

1. Axon RN, Turner M, Buckley R. An update on inpatient hypertension management. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015 Nov;17(11):94.

2. Herzog E, Frankenberger O, Aziz E, et al. A novel pathway for the management of hypertension for hospitalized patients. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2007;6(4):150-60.

3. Sharma P, Shrestha A. Inpatient hypertension management. ACP Hospitalist. Aug 2014.

Quiz

Asymptomatic hypertension in the hospital

Hypertension is a common focus in the ambulatory setting because of its increased risk for cardiovascular events. Evidence for management in the inpatient setting is limited but does suggest a more conservative approach.

Question: A 75-year-old woman is hospitalized after sustaining a mechanical fall and subsequent right femoral neck fracture. She has a history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia for which she takes amlodipine and atorvastatin. Her blood pressure initially on admission is 170/102 mm Hg, and she is asymptomatic other than severe right hip pain. Her amlodipine and atorvastatin are resumed. Repeat blood pressures after resuming her amlodipine are still elevated with an average blood pressure reading of 168/98 mm Hg. Which of the following would be the next best step in treating this patient?

A. A one-time dose of intravenous hydralazine at 10 mg to reduce blood pressure by 25% over next several hours.

B. A one-time dose of oral clonidine at 0.1 mg to reduce blood pressure by 25% over next several hours.

C. Start a second daily antihypertensive with lisinopril 5 mg daily.

D. Address the patient’s pain.

The best answer is choice D. The patient’s hypertension is likely aggravated by her hip pain. Thus, the best course of action would be to address her pain.

Choice A is not the best answer as an intravenous antihypertensive is not indicated in this patient as she is asymptomatic and exhibiting no signs/symptoms of end-organ damage.

Choice B is not the best answer as by addressing her pain it is likely her blood pressure will improve. Urgent use of oral antihypertensives would not be indicated.

Choice C is not the best answer as patient has acute elevation of blood pressure in setting of a right femoral neck fracture and pain. Her blood pressure will likely improve after addressing her pain. However, if there is persistent blood pressure elevation, starting long-acting antihypertensive would be appropriate per JNC 8 guidelines.

Key Points

- Evidence for treatment of inpatient asymptomatic hypertension is lacking.

- The use of intravenous antihypertensives in the setting of inpatient asymptomatic hypertension is inappropriate and may be harmful.

- A conservative approach for inpatient asymptomatic hypertension should be employed by addressing contributing factors and reviewing held home antihypertensive medications prior to administering any oral antihypertensive pharmacotherapy.

Case

A 62-year-old man with diabetes mellitus and hypertension presents with painful erythema of the left lower extremity and is admitted for purulent cellulitis. During the first evening of admission, he has increased left lower extremity pain and nursing reports a blood pressure of 188/96 mm Hg. He denies dyspnea, chest pain, visual changes, confusion, or severe headache.

Background

The prevalence of hypertension in the outpatient setting in the United States is estimated at 29% by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.1 Hypertension generally is defined in the outpatient setting as an average blood pressure reading greater than or equal to140/90 mm Hg on two or more separate occasions.2 There is no consensus on the definition of hypertension in the inpatient setting; however, hypertensive urgency often is defined as a sustained blood pressure above the range of 180-200 mm Hg systolic and/or 110-120 mm Hg diastolic without target organ damage, and hypertensive emergency has a similar blood pressure range, but with evidence of target organ damage.3

The evidence

There are several clinical trials to suggest that the ambulatory treatment of chronic hypertension reduces the incidence of myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), and heart failure7,8; however, these trials are difficult to extrapolate to acutely hospitalized patients.6 Overall, evidence on the appropriate management of asymptomatic hypertension in the inpatient setting is lacking.

Some evidence suggests we often are overly aggressive with intravenous antihypertensives without clinical indications in the inpatient setting.3,9,10 For example, Campbell et al. prospectively examined the use of intravenous hydralazine for the treatment of asymptomatic hypertension in 94 hospitalized patients.10 It was determined that in 90 of those patients, there was no clinical indication to use intravenous hydralazine and 17 patients experienced adverse events from hypotension, which included dizziness/light-headedness, syncope, and chest pain.10 They recommend against the use of intravenous hydralazine in the setting of asymptomatic hypertension because of its risk of adverse events with the rapid lowering of blood pressure.10

Weder and Erickson performed a retrospective review on the use of intravenous hydralazine and labetalol administration in 2,189 hospitalized patients.3 They found that only 3% of those patients had symptoms indicating the need for IV antihypertensives and that the length of stay was several days longer in those who had received IV antihypertensives.3

Other studies have examined the role of oral antihypertensives for management of asymptomatic hypertension in the inpatient setting. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Souza et al. assessed the use of oral pharmacotherapy for hypertensive urgency.11 Sixteen randomized clinical trials were reviewed and it was determined that angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) had a superior effect in treating hypertensive urgencies.11 The most common side effect of using an ACE-I was a bad taste in patient’s mouths, and researchers did not observe side effects that were similar as those seen with the use of IV antihypertensives.11

Further, Jaker et al. performed a randomized, double-blind prospective study comparing a single dose of oral nifedipine with oral clonidine for the treatment of hypertensive urgency in 51 patients.12 Both the oral nifedipine and oral clonidine were extremely effective in reducing blood pressure fairly safely.12 However, the rapid lowering of blood pressure with oral nifedipine was concerning to Grossman et al.13 In their literature review of the side effects of oral and sublingual nifedipine, they found that it was one of the most common therapeutic interventions for hypertensive urgency or emergency.13 However, it was potentially dangerous because of the inconsistent blood pressure response after nifedipine administration, particularly with the sublingual form.13 CVAs, acute MIs, and even death were the reported adverse events with the use of oral and sublingual nifedipine.13 Because of that, the investigators recommend against the use of oral or sublingual nifedipine in hypertensive urgency or emergency and suggest using other oral antihypertensive agents instead.13

Typically, if the patient’s blood pressure remains elevated despite these efforts, no urgent treatment is indicated and we recommend close monitoring of the patient’s blood pressure during the hospitalization. If hypertension persists, the next best step would be to titrate a patient’s current oral antihypertensive therapy or to start a long-acting antihypertensive therapy per the JNC 8 (Eighth Joint National Committee) guidelines. It should be noted that, in those patients that are high risk, such as those with known coronary artery disease, heart failure, or prior hemorrhagic CVA, a short-acting oral antihypertensive such as captopril, carvedilol, clonidine, or furosemide should be considered.

Back to the case

The patient’s pain was treated with oral oxycodone. He received no oral or intravenous antihypertensive therapy, and the following morning, his blood pressure improved to 145/95 mm Hg. Based on our suggested approach in Fig. 1, the patient would require no acute treatment despite an improved but elevated blood pressure. We continued to monitor his blood pressure and despite adequate pain control, his blood pressure remain persistently elevated. Thus, per the JNC 8 guidelines, we started him on a long-acting antihypertensive, which improved his blood pressure to 123/78 at the time of discharge.

Bottom line

Management of asymptomatic hypertension in the hospital begins with addressing contributing factors, reviewing held home medications – and rarely – urgent oral pharmacotherapy.

Dr. Lippert is PGY-3 in the department of internal medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Bailey is associate professor of medicine at the University of Kentucky. Dr. Gray is associate professor of medicine at the University of Kentucky.

References

1. Yoon S, Fryar C, Carroll M. Hypertension prevalence and control among adults: United States, 2011-2014. 2015. Accessed Oct 2, 2017.

2. Poulter NR, Prabhakaran D, Caulfield M. Hypertension. Lancet. 2015;386(9995):801-12.

3. Weder AB, Erickson S. Treatment of hypertension in the inpatient setting: Use of intravenous labetalol and hydralazine. J Clin Hypertens. 2010;12(1):29-33.

4. Axon RN, Cousineau L, Egan BM. Prevalence and management of hypertension in the inpatient setting: A systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(7):417-22.

5. Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of hospital stays in the United States, 2012. Statistical brief; 2014 Oct. Accessed Oct 2, 2017.

6. Weder AB. Treating acute hypertension in the hospital: a Lacuna in the guidelines. Hypertension. 2011;57(1):18-20.

7. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension and of the European Society of Cardiology. J Hypertens. 2013 Jul;31(7):1281-357.

8. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-20.

9. Lipari M, Moser LR, Petrovitch EA, et al. As-needed intravenous antihypertensive therapy and blood pressure control. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(3):193-8.

10. Campbell P, Baker WL, Bendel SD, et al. Intravenous hydralazine for blood pressure management in the hospitalized patient: Its use is often unjustified. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2011;5(6):473-7.

11. Souza LM, Riera R, Saconato H, et al. Oral drugs for hypertensive urgencies: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Sao Paulo Med J. 2009;127(6):366-72.

12. Jaker M, Atkin S, Soto M, et al. Oral nifedipine vs. oral clonidine in the treatment of urgent hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149(2):260-5.

13. Grossman E, Messerli FH, Grodzicki T, et al. Should a moratorium be placed on sublingual nifedipine capsules given for hypertensive emergencies and pseudoemergencies? JAMA. 1996;276(16):1328-31.

14. Axon RN, Turner M, Buckley R. An update on inpatient hypertension management. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015;17(11):94.

Additional Reading

1. Axon RN, Turner M, Buckley R. An update on inpatient hypertension management. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015 Nov;17(11):94.

2. Herzog E, Frankenberger O, Aziz E, et al. A novel pathway for the management of hypertension for hospitalized patients. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2007;6(4):150-60.

3. Sharma P, Shrestha A. Inpatient hypertension management. ACP Hospitalist. Aug 2014.

Quiz

Asymptomatic hypertension in the hospital

Hypertension is a common focus in the ambulatory setting because of its increased risk for cardiovascular events. Evidence for management in the inpatient setting is limited but does suggest a more conservative approach.

Question: A 75-year-old woman is hospitalized after sustaining a mechanical fall and subsequent right femoral neck fracture. She has a history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia for which she takes amlodipine and atorvastatin. Her blood pressure initially on admission is 170/102 mm Hg, and she is asymptomatic other than severe right hip pain. Her amlodipine and atorvastatin are resumed. Repeat blood pressures after resuming her amlodipine are still elevated with an average blood pressure reading of 168/98 mm Hg. Which of the following would be the next best step in treating this patient?

A. A one-time dose of intravenous hydralazine at 10 mg to reduce blood pressure by 25% over next several hours.

B. A one-time dose of oral clonidine at 0.1 mg to reduce blood pressure by 25% over next several hours.

C. Start a second daily antihypertensive with lisinopril 5 mg daily.

D. Address the patient’s pain.

The best answer is choice D. The patient’s hypertension is likely aggravated by her hip pain. Thus, the best course of action would be to address her pain.

Choice A is not the best answer as an intravenous antihypertensive is not indicated in this patient as she is asymptomatic and exhibiting no signs/symptoms of end-organ damage.

Choice B is not the best answer as by addressing her pain it is likely her blood pressure will improve. Urgent use of oral antihypertensives would not be indicated.

Choice C is not the best answer as patient has acute elevation of blood pressure in setting of a right femoral neck fracture and pain. Her blood pressure will likely improve after addressing her pain. However, if there is persistent blood pressure elevation, starting long-acting antihypertensive would be appropriate per JNC 8 guidelines.

Key Points

- Evidence for treatment of inpatient asymptomatic hypertension is lacking.

- The use of intravenous antihypertensives in the setting of inpatient asymptomatic hypertension is inappropriate and may be harmful.

- A conservative approach for inpatient asymptomatic hypertension should be employed by addressing contributing factors and reviewing held home antihypertensive medications prior to administering any oral antihypertensive pharmacotherapy.

Case

A 62-year-old man with diabetes mellitus and hypertension presents with painful erythema of the left lower extremity and is admitted for purulent cellulitis. During the first evening of admission, he has increased left lower extremity pain and nursing reports a blood pressure of 188/96 mm Hg. He denies dyspnea, chest pain, visual changes, confusion, or severe headache.

Background

The prevalence of hypertension in the outpatient setting in the United States is estimated at 29% by the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey.1 Hypertension generally is defined in the outpatient setting as an average blood pressure reading greater than or equal to140/90 mm Hg on two or more separate occasions.2 There is no consensus on the definition of hypertension in the inpatient setting; however, hypertensive urgency often is defined as a sustained blood pressure above the range of 180-200 mm Hg systolic and/or 110-120 mm Hg diastolic without target organ damage, and hypertensive emergency has a similar blood pressure range, but with evidence of target organ damage.3

The evidence

There are several clinical trials to suggest that the ambulatory treatment of chronic hypertension reduces the incidence of myocardial infarction, cerebrovascular accident (CVA), and heart failure7,8; however, these trials are difficult to extrapolate to acutely hospitalized patients.6 Overall, evidence on the appropriate management of asymptomatic hypertension in the inpatient setting is lacking.

Some evidence suggests we often are overly aggressive with intravenous antihypertensives without clinical indications in the inpatient setting.3,9,10 For example, Campbell et al. prospectively examined the use of intravenous hydralazine for the treatment of asymptomatic hypertension in 94 hospitalized patients.10 It was determined that in 90 of those patients, there was no clinical indication to use intravenous hydralazine and 17 patients experienced adverse events from hypotension, which included dizziness/light-headedness, syncope, and chest pain.10 They recommend against the use of intravenous hydralazine in the setting of asymptomatic hypertension because of its risk of adverse events with the rapid lowering of blood pressure.10

Weder and Erickson performed a retrospective review on the use of intravenous hydralazine and labetalol administration in 2,189 hospitalized patients.3 They found that only 3% of those patients had symptoms indicating the need for IV antihypertensives and that the length of stay was several days longer in those who had received IV antihypertensives.3

Other studies have examined the role of oral antihypertensives for management of asymptomatic hypertension in the inpatient setting. A systematic review and meta-analysis by Souza et al. assessed the use of oral pharmacotherapy for hypertensive urgency.11 Sixteen randomized clinical trials were reviewed and it was determined that angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACE-I) had a superior effect in treating hypertensive urgencies.11 The most common side effect of using an ACE-I was a bad taste in patient’s mouths, and researchers did not observe side effects that were similar as those seen with the use of IV antihypertensives.11

Further, Jaker et al. performed a randomized, double-blind prospective study comparing a single dose of oral nifedipine with oral clonidine for the treatment of hypertensive urgency in 51 patients.12 Both the oral nifedipine and oral clonidine were extremely effective in reducing blood pressure fairly safely.12 However, the rapid lowering of blood pressure with oral nifedipine was concerning to Grossman et al.13 In their literature review of the side effects of oral and sublingual nifedipine, they found that it was one of the most common therapeutic interventions for hypertensive urgency or emergency.13 However, it was potentially dangerous because of the inconsistent blood pressure response after nifedipine administration, particularly with the sublingual form.13 CVAs, acute MIs, and even death were the reported adverse events with the use of oral and sublingual nifedipine.13 Because of that, the investigators recommend against the use of oral or sublingual nifedipine in hypertensive urgency or emergency and suggest using other oral antihypertensive agents instead.13

Typically, if the patient’s blood pressure remains elevated despite these efforts, no urgent treatment is indicated and we recommend close monitoring of the patient’s blood pressure during the hospitalization. If hypertension persists, the next best step would be to titrate a patient’s current oral antihypertensive therapy or to start a long-acting antihypertensive therapy per the JNC 8 (Eighth Joint National Committee) guidelines. It should be noted that, in those patients that are high risk, such as those with known coronary artery disease, heart failure, or prior hemorrhagic CVA, a short-acting oral antihypertensive such as captopril, carvedilol, clonidine, or furosemide should be considered.

Back to the case

The patient’s pain was treated with oral oxycodone. He received no oral or intravenous antihypertensive therapy, and the following morning, his blood pressure improved to 145/95 mm Hg. Based on our suggested approach in Fig. 1, the patient would require no acute treatment despite an improved but elevated blood pressure. We continued to monitor his blood pressure and despite adequate pain control, his blood pressure remain persistently elevated. Thus, per the JNC 8 guidelines, we started him on a long-acting antihypertensive, which improved his blood pressure to 123/78 at the time of discharge.

Bottom line

Management of asymptomatic hypertension in the hospital begins with addressing contributing factors, reviewing held home medications – and rarely – urgent oral pharmacotherapy.

Dr. Lippert is PGY-3 in the department of internal medicine at the University of Kentucky, Lexington. Dr. Bailey is associate professor of medicine at the University of Kentucky. Dr. Gray is associate professor of medicine at the University of Kentucky.

References

1. Yoon S, Fryar C, Carroll M. Hypertension prevalence and control among adults: United States, 2011-2014. 2015. Accessed Oct 2, 2017.

2. Poulter NR, Prabhakaran D, Caulfield M. Hypertension. Lancet. 2015;386(9995):801-12.

3. Weder AB, Erickson S. Treatment of hypertension in the inpatient setting: Use of intravenous labetalol and hydralazine. J Clin Hypertens. 2010;12(1):29-33.

4. Axon RN, Cousineau L, Egan BM. Prevalence and management of hypertension in the inpatient setting: A systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2011;6(7):417-22.

5. Weiss AJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of hospital stays in the United States, 2012. Statistical brief; 2014 Oct. Accessed Oct 2, 2017.

6. Weder AB. Treating acute hypertension in the hospital: a Lacuna in the guidelines. Hypertension. 2011;57(1):18-20.

7. Mancia G, Fagard R, Narkiewicz K, et al. 2013 ESH/ESC guidelines for the management of arterial hypertension: The Task Force for the management of arterial hypertension of the European Society of Hypertension and of the European Society of Cardiology. J Hypertens. 2013 Jul;31(7):1281-357.

8. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 Evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults: Report from the panel members appointed to the Eighth Joint National Committee (JNC 8). JAMA. 2014;311(5):507-20.

9. Lipari M, Moser LR, Petrovitch EA, et al. As-needed intravenous antihypertensive therapy and blood pressure control. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(3):193-8.

10. Campbell P, Baker WL, Bendel SD, et al. Intravenous hydralazine for blood pressure management in the hospitalized patient: Its use is often unjustified. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2011;5(6):473-7.

11. Souza LM, Riera R, Saconato H, et al. Oral drugs for hypertensive urgencies: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Sao Paulo Med J. 2009;127(6):366-72.

12. Jaker M, Atkin S, Soto M, et al. Oral nifedipine vs. oral clonidine in the treatment of urgent hypertension. Arch Intern Med. 1989;149(2):260-5.

13. Grossman E, Messerli FH, Grodzicki T, et al. Should a moratorium be placed on sublingual nifedipine capsules given for hypertensive emergencies and pseudoemergencies? JAMA. 1996;276(16):1328-31.

14. Axon RN, Turner M, Buckley R. An update on inpatient hypertension management. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015;17(11):94.

Additional Reading

1. Axon RN, Turner M, Buckley R. An update on inpatient hypertension management. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2015 Nov;17(11):94.

2. Herzog E, Frankenberger O, Aziz E, et al. A novel pathway for the management of hypertension for hospitalized patients. Crit Pathw Cardiol. 2007;6(4):150-60.

3. Sharma P, Shrestha A. Inpatient hypertension management. ACP Hospitalist. Aug 2014.

Quiz

Asymptomatic hypertension in the hospital

Hypertension is a common focus in the ambulatory setting because of its increased risk for cardiovascular events. Evidence for management in the inpatient setting is limited but does suggest a more conservative approach.

Question: A 75-year-old woman is hospitalized after sustaining a mechanical fall and subsequent right femoral neck fracture. She has a history of hypertension and hyperlipidemia for which she takes amlodipine and atorvastatin. Her blood pressure initially on admission is 170/102 mm Hg, and she is asymptomatic other than severe right hip pain. Her amlodipine and atorvastatin are resumed. Repeat blood pressures after resuming her amlodipine are still elevated with an average blood pressure reading of 168/98 mm Hg. Which of the following would be the next best step in treating this patient?

A. A one-time dose of intravenous hydralazine at 10 mg to reduce blood pressure by 25% over next several hours.

B. A one-time dose of oral clonidine at 0.1 mg to reduce blood pressure by 25% over next several hours.

C. Start a second daily antihypertensive with lisinopril 5 mg daily.

D. Address the patient’s pain.

The best answer is choice D. The patient’s hypertension is likely aggravated by her hip pain. Thus, the best course of action would be to address her pain.

Choice A is not the best answer as an intravenous antihypertensive is not indicated in this patient as she is asymptomatic and exhibiting no signs/symptoms of end-organ damage.

Choice B is not the best answer as by addressing her pain it is likely her blood pressure will improve. Urgent use of oral antihypertensives would not be indicated.

Choice C is not the best answer as patient has acute elevation of blood pressure in setting of a right femoral neck fracture and pain. Her blood pressure will likely improve after addressing her pain. However, if there is persistent blood pressure elevation, starting long-acting antihypertensive would be appropriate per JNC 8 guidelines.

Key Points

- Evidence for treatment of inpatient asymptomatic hypertension is lacking.

- The use of intravenous antihypertensives in the setting of inpatient asymptomatic hypertension is inappropriate and may be harmful.

- A conservative approach for inpatient asymptomatic hypertension should be employed by addressing contributing factors and reviewing held home antihypertensive medications prior to administering any oral antihypertensive pharmacotherapy.