User login

Diagnosis and Treatment of Migraine

From the Department of Neurology, Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC.

Abstract

- Objective: To review the epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of migraine.

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: Migraine is a common disorder associated with significant morbidity. Diagnosis of migraine is performed according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders. Comorbidities are commonly seen with migraine and include mood disorders (depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder), musculoskeletal disorders (neck pain, fibromyalgia, Ehlors-Danlos syndrome), sleep disorders, asthma, allergies, thyroid dysfunction, obesity, irritable bowel syndrome, epilepsy, stroke, and heart disease. Comorbid conditions can increase migraine disability. Management of migraine with lifestyle modifications, trigger management, and acute and preventive medications can help reduce the frequency, duration, and severity of attacks. Overuse of medications such as opiates, barbiturates, and caffeine-containing medications can increase headache frequency. Educating patients about limiting use of these medications is important.

- Conclusion: Migraine is a common neurologic disease that can be very disabling. Recognizing the condition, making an accurate diagnosis, and starting patients on migraine-specific treatments can help improve patient outcomes.

Migraine is a common neurologic disease that affects 1 in 10 people worldwide [1]. It is 2 to 3 times more prevalent in women than in men [2]. The prevalence of migraine peaks in both sexes during the most productive years of adulthood (age 25 to 55 years) [3]. The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study considers it to be the 7th most disabling disease in the world [4]. Over 36 million people in the United States have migraine [5]. However, just 56% of migraineurs have ever been diagnosed [6].

Migraine is associated with a high rate of years lived with disability [7] and the rate has been steadily increasing since 1990. At least 50% of migraine sufferers are severely disabled, many requiring bed rest, during individual migraine attacks lasting hours to days [8]. The total U.S. annual economic costs from headache disorders, including the indirect costs from lost productivity and workplace performance, has been estimated at $31 billion [9,10].

Despite the profound impact of migraine on patients and society, there are numerous barriers to migraine care. Lipton et al [11] identified 3 steps that were minimally necessary to achieve guideline-defined appropriate acute pharmacologic therapy: (1) consulting a prescribing health care professional; (2) receiving a migraine diagnosis; and (3) using migraine-specific or other appropriate acute treatments. In a study they conducted in patients with episodic migraine, 45.5% had consulted health care professional for headache in the preceding year; of these, 86.7% reported receiving a medical diagnosis of migraine, and among the diagnosed consulters, 66.7% currently used acute migraine-specific treatments, resulting in only 26.3% individuals successfully completing all 3 steps. In the recent CaMEO study [12], the proportion patients with chronic migraine that overcame all 3 barriers was less than 5%.

The stigma of migraine often makes it difficult for people to discuss symptoms with their health care providers and family members [13]. When they do discuss their headaches with their provider, often they are not given a diagnosis [14] or do not understand what their diagnosis means [15]. It is important for health care providers to be vigilant about the diagnosis of migraine, discuss treatment goals and strategies, and prescribe appropriate migraine treatment. Migraine is often comorbid with a number of medical, neurological, and psychiatric conditions, and identifying and managing comorbidities is necessary to reduce headache burden and disability. In this article, we provide a review of the diagnosis and treatment of migraine, using a case illustration to highlight key points.

Case Study

Initial Presentation

A 24-year-old woman presents for an evaluation of her headaches.

History and Physical Examination

She initially noted headaches at age 19, which were not memorable and did not cause disability. Her current headaches are a severe throbbing pain over her right forehead. They are associated with light and sound sensitivity and stomach upset. Headaches last 6 to 7 hours without medications and occur 4 to 8 days per month.

She denies vomiting and autonomic symptoms such as runny nose or eye tearing. She also denies preceding aura. She reports headache relief with intake of tablets that contain acetaminophen/aspirin/caffeine and states that she takes between 4 to 15 tablets/month depending on headache frequency. She reports having tried acetaminophen and naproxen with no significant benefit. Aggravating factors include bright lights, strong smells, and soy/ high-sodium foods.

She had no significant past medical problems and denied a history of depression or anxiety. Family history was significant for both her father and sister having a history of headaches. The patient lived alone and denied any major life stressors. She exercises 2 times a week and denies smoking or alcohol use. Review of systems was positive for trouble sleeping, which she described as difficulty falling asleep.

On physical examination, vitals were within normal limits. BMI was 23. Chest, cardiac, abdomen, and general physical examination were all within normal limits. Neurological examination revealed no evidence of papilledema or focal neurological deficits.

What is the pathophysiology of migraine?

Migraine was thought to be a primary vascular disorder of the brain, with the origins of the vascular theory of migraine dating back to 1684 [16]. Trials performed by Wolff concluded that migraine is of vascular origin [17], and this remained the predominant theory over several decades. Current evidence suggests that migraine is unlikely to be a pure vascular disorder and instead may be related to changes in the central or peripheral nervous system [18,19].

Migraine is complex brain network disorder with a strong genetic basis [19]. The trigemino-vascular system, along with neurogenically induced inflammation of the dura mater, mast cell degranulation and release of histamine, are the likely causes of migraine pain. Trigeminal fibers arise from neurons in the trigeminal ganglion that contain substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) [20]. CGRP is a neuropeptide widely expressed in both peripheral and central neurons. Elevation of CGRP in migraine is linked to diminution of the inhibitory pathways which in turn leads to migraine susceptibility [21]. These findings have led to the development of new drugs that target the CGRP pathway.

In the brainstem, periaqueductal grey matter and the dorsolateral pons have been found to be “migraine generators,” or the driver of changes of cortical activity during migraine [22]. Brainstem nuclei are involved in modulating trigemino-vascular pain transmission and autonomic responses in migraine [23].

The hypothalamus has also been implicated in migraine pathogenesis, particularly its role in nociceptive and autonomic modulation in migraine patients. Schulte and May hypothesized that there is a network change between the hypothalamus and the areas of the brainstem generator leading to the migraine attacks [24].

The thalamus plays a central role for the processing and integration of pain stimuli from the dura mater and cutaneous regions. It maintains complex connections with the somatosensory, motor, visual, auditory, olfactory and limbic regions [25]. The structural and functional alterations in the system play a role in the development of migraine attacks, and also in the sensory hypersensitivity to visual stimuli and mechanical allodynia [26].

Experimental studies in rats show that cortical spreading depression can trigger neurogenic meningeal inflammation and subsequently activate the trigemino-vascular system [27]. It has been observed that between migraine episodes a time-dependent amplitude increase of scalp-evoked potentials to repeated stereotyped stimuli, such as visual, auditory, and somaticstimuli, occurs. This phenomenon is described as “deficient habituation.” In episodic migraine, studies show 2 characteristic changes: a deficient habituation between attacks and sensitization during the attack [28]. Genetic studies have hypothesized an involvement of glutamatergic neurotransmitters and synaptic dysplasticity in causing abnormal cortical excitability in migraine [27].

What are diagnostic criteria for migraine?

Diagnosis of migraine is performed according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) [29]. Based on the number of headache days that the patient reports, migraine is classified into episodic or chronic migraine. Migraines that occur on fewer than 15 days/month are categorized as episodic migraines.

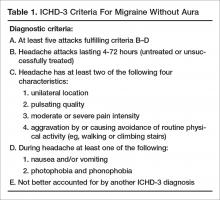

Episodic migraine is divided into 2 categories: migraine with aura (Table 1) and migraine without aura. Migraine without aura is described as recurrent headaches consisting of at least 5 attacks, each lasting 4 to 72 hours if left untreated. At least 2 of the following 4 characteristics must be present: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe pain intensity, with aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity. During headache, at least 1 of nausea and/or vomiting or photophobia and phonophobia should be present.

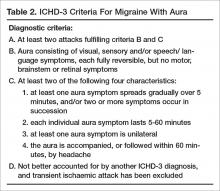

In migraine with aura (Table 2), headache characteristics are the same, but in addition there are at least 2 lifetime attacks with fully reversible aura symptoms (visual, sensory, speech/language). In addition, these auras have at least 2 of the following 4 characteristics: at least 1 aura symptom spreads gradually over 5 minutes, and/or 2 or more symptoms occur in succession; each individual aura symptom lasts 5 to 60 minutes; aura symptom is unilateral; and aura is accompanied, or followed within 60 minutes, by headache. Migraine with aura is uncommon, occurring in 20% of patients with migraine [30]. Visual aura is the most common type of aura, occurring in up to 90% of patients [31]. There is also aura without migraine, called typical aura without headache. Patients can present with non-migraine headache with aura, categorized as typical aura with headache [29].

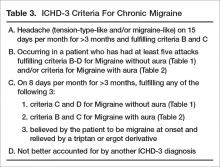

Headache occurring on 15 or more days per month for more than 3 months, which has the features of migraine headache on at least 8 days per month, is classified as chronic migraine (Table 3). Evidence indicates that 2.5% of episodic migraine progresses to chronic migraine over 1-year follow-up [32]. There are several risk factors for chronification of migraine. Nonmodifiable factors include female sex, white European heritage, head/neck injury, low education/socioeconomic status, and stressful life events (divorce, moving, work changes, problems with children). Modifiable risk factors are headache frequency, acute medication overuse, caffeine overuse, obesity, comorbid mood disorders, and allodynia. Acute medication use and headache frequency are independent risk factors for development of chronic migraine [33]. The risk of chronic migraine increases exponentially with increased attack frequency, usually when the frequency is ≥ 3 headaches/month. Repetitive episodes of pain may increase central sensitization and result in anatomical changes in the brain and brainstem [34].

What information should be elicited during the history?

Specific questions about the headaches can help with making an accurate diagnosis. These include:

- Length of attacks and their frequency

- Pain characteristics (location, quality, intensity)

- Actions that trigger or aggravate headaches (eg, stress, movement, bright lights, menses, certain foods and smells)

- Associated symptoms that accompany headaches (eg, nausea, vomiting)

- How the headaches impact their life (eg, missed days at work or school, missed life events, avoidance of social activities, emergency room visits due to headache)

To assess headache frequency, it is helpful to ask about the number of headache-free days in a month, eg, “how many days a month do you NOT have a headache.” To assist with headache assessment, patients can be asked to keep a calendar in which they mark days of use of medications, including over the counter medications, menses, and headache days. The calendar can be used to assess for migraine patterns, headache frequency, and response to treatment.

When asking about headache history, it is important for patients to describe their untreated headaches. Patients taking medications may have pain that is less severe or disabling or have reduced associated symptoms. Understanding what the headaches were like when they did not treat is important in making a diagnosis.

Other important questions include when was the first time they recall ever experiencing a headache. Migraine is often present early in life, and understanding the change in headache over time is important. Also ask patients about what they want to do when they have a headache. Often patients want to lie down in a cool dark room. Ask what they would prefer to do if they didn’t have any pending responsibilities.

Comorbidities

Comorbidities are commonly seen with migraine. Common comorbidities are mood disorders (depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder), musculoskeletal disorders (neck pain, fibromyalgia, Ehlors-Danlos syndrome), sleep disorders, asthma, allergies, thyroid dysfunction, obesity, irritable bowel syndrome, epilepsy, stroke, and heart disease.

Comorbid conditions can increase migraine disability and also can provide information about the pathophysiology of migraine and guide treatment. Management of the underlying comorbidity often leads to improved migraine outcomes. For example, serotonergic dysfunction is a possible pathway involved in both migraine and mood disorders. Treatment with medications that alter the serotonin system may help both migraine and coexisting mood disorders. Bigal et al proposed that activation of the HPA axis with reduced serotonin synthesis is a main pathway involved in affective disorders, migraine, and obesity [35].

In the early 1950s, Wolff conceptualized migraine as a psychophysiologic disorder [36]. The relationship between migraine and psychiatric conditions is complex, and comorbid psychiatric disorders are risk factors for headache progression and chronicity. Psychiatric conditions also play a role in nonadherence to headache medication, which contributes to poor outcome in these patients. Hence, there is a need for assessment and treatment of psychiatric disorders in people with migraine. A study by Guidetti et al found that headache patients with multiple psychiatric conditions have poor outcomes, with 86 % of these headache patients having no improvement and even deterioration in their headache [37]. Another study by Mongini et al concluded that psychiatric disorder appears to influence the result of treatment on a long-term basis [38].

In addition, migraine has been shown to impact mood disorders. Worsening headache was found to be associated with poorer prognosis for depression. Patients with active migraine not on medications with comorbid major depressive disorder (MDD) had more severe anxiety and somatic symptoms as compared with MDD patients without migraine [39].

Case Continued

Our patient has a normal neurologic examination and classic migraine headache history and stable frequency. The physician tells her she meets criteria for episodic migraine without aura. The patient asks if she needs a “brain scan” to see if something more serious may be causing her symptoms.

What workup is recommended for patients with migraine?

If patient symptoms fit the criteria for migraine and there is a normal neurologic examination, the differential is often limited. When there are neurologic abnormalities on examination (eg, papilledema), or if the patient has concerning signs or symptoms (see below), then neuroimaging should be obtained to rule out secondary causes of headache.

In 2014, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) published practice parameters on the evaluation of adults with recurrent headache based on guidelines published by the US Headache Consortium [40]. As per AAN guidelines, routine laboratory studies, lumbar puncture, and electroencephalogram are not recommended in the evaluation of non-acute migraines. Neuroimaging is not warranted in patients with migraine and a normal neurologic examination (grade B recommendation). Imaging may need to be considered in patients with non-acute headache and an unexplained abnormal finding on the neurologic examination (grade B recommendation).

When patients exhibit particular warning signs, or headache “red flags,” it is recommended that neuroimaging be considered. Red flags include patients with recurrent headaches and systemic symptoms (fever, weight loss), neurologic symptoms or abnormal signs (confusion, impaired alertness or consciousness), sudden onset, abrupt, or split second in nature, patients age > 50 with new onset or progressive headache, previous headache history with new or different headache (change in frequency, severity, or clinical features) and if there are secondary risk factors (HIV, cancer) [41].

Case Continued

Our patient has no red flags and can be reassured that given her normal physical examination and history suggestive of a migraine, a secondary cause of her headache is unlikely. The physician describes the treatments available, including implementing lifestyles changes and preventive and abortive medications. The patient expresses apprehension about being on prescription medications. She is concerned about side effects as well as the need to take daily medication over a long period of time. She reports that these were the main reasons she did not take the rizatriptan and propranolol that was prescribed by her previous doctor.

How is migraine treated?

Migraine is managed with a combination of lifestyle changes and pharmacologic therapy. Pharmacologic management targets treating an attack when it occurs (abortive medication), as well as reducing the frequency and severity of future attacks (preventive medication).

Lifestyle Changes

Patients should be advised that making healthy lifestyle choices, eg, regular sleep, balanced meals, proper hydration, and regular exercise, can mitigate migraine [42–44]. Other lifestyle changes that can be helpful include weight loss in the obese population, as weight loss appears to result in migraine improvement. People who are obese also are at higher risk for the progression to chronic migraine.

Acute Therapy

There are varieties of abortive therapies [45] (Table 4) that are commonly used in clinical practice. Abortive therapy can be taken as needed and is most effective if used within the first 2 hours of headache. For patients with daily or frequent headache, these medications need to be restricted to 8 to 12 days a month of use and their use should be restricted to when headache is worsening. This usually works well in patients with moderate level pain, and especially in patients with no associated nausea. Selective migraine treatments, like triptans and ergots, are used when nonspecific treatments fail, or when headache is more severe. It is preferable that patients avoid opioids, butalbital, and caffeine-containing medications. In the real world, it is difficult to convince patient to stop these medications; it is more realistic to discuss use limitation with patients, who often run out their weekly limit for triptans.

Triptans are effective medications for acute management of migraine but headache recurrence rate is high, occurring in 15% to 40 % of patients taking oral triptans. It is difficult to predict the response to a triptan [46]. The choice of an abortive agent is often directed partially by patient preference (side effect profile, cost, non-sedating vs. prefers to sleep, long vs short half-life), comorbid conditions (avoid triptans and ergots in uncontrolled hypertension, cardiovascular disease, or peripheral vascular disease or stroke/aneurysm; avoid NSAIDS in patients with cardiovascular disease), and migraine-associated symptoms (nausea and/or vomiting). Consider non-oral formulations via subcutaneous or nasal routes in patients who have nausea or vomiting with their migraine attacks. Some patients may require more than one type of abortive medication. The high recurrence rate is similar across different triptans and so switching from one triptan to another has not been found to be useful. Adding NSAIDS to triptans has been found to be more useful than switching between triptans.Overuse of acute medications has been associated with transformation of headache from episodic to chronic (medication overuse headache or rebound headache). The risk of transformation appears to be greatest with medications containing caffeine, opiates, or barbiturates [47]. Use of acute medications should be limited based on the type of medication. Patients should take triptans for no more than 10 days a month. Combined medications and opioids should be used fewer than 8 days a month, and butalbital-containing medications should be avoided or used fewer than 5 days a month [48]. Use of acute therapy should be monitored with headache calendars. It is unclear if and to what degree NSAIDS and acetaminophen cause overuse headaches.

Medication overuse headache can be difficult to treat as patients have to stop using the medication causing rebound. Further, headaches often resemble migraine and it can be difficult to differentiate them from the patients’ routine headache. Vigilance with medication use in patients with frequent headache is an essential part of migraine management, and patients should receive clear instructions regarding how to use acute medications.

Prevention

Patients presenting with more than 4 headaches per month, or headaches that last longer than 12 hours, require preventive therapy. The goals of preventive therapy is to reduce attack frequency, severity, and duration, to improve responsiveness to treatment of acute attacks, to improve function and reduce disability, and to prevent progression or transformation of episodic migraine to chronic migraine. Preventive medications usually need to be taken daily to reduce frequency or severity of the headache. The goal in this approach is 50% reduction of headache frequency and severity. Migraine preventive medications usually belong to 1 of 3 categories of drugs: antihypertensives, antiepileptics, and antidepressants. At present there are many medications for migraine prevention with different levels of evidence [49] (Table 5). Onabotulinuma toxin is the only approved medication for chronic migraine based on promising results of the PREEMPT trial [50].

Other Considerations

A multidisciplinary approach to treatment may be warranted. Psychiatric evaluation and management of underlying depression and mood disorders can help reduce headache frequency and severity. Physical therapy should be prescribed for neck and shoulder pain. Sleep specialists should be consulted if ongoing sleep issues continue despite behavioral management.

How common is nonadherence with migraine medication?

One third of patients who are prescribed triptans discontinue the medication within a year. Lack of efficacy and concerns over medication side effects are 2 of the most common reasons for poor adherence [51]. In addition, age plays a significant role in discontinuing medication, with the elderly population more likely to stop taking triptans [52]. Seng et al reported that among patients with migraine, being male, being single, having frequent headache, and having mild pain are all associated with medication nonadherence [53]. Formulary restrictions and type of insurance coverage also were associated with nonadherence. Among adherent patients, some individuals were found to be hoarding their tablets and waiting until they were sure it was a migraine. Delaying administration of abortive medications increases the chance of incomplete treatment response, leading to patients taking more medication and in turn have more side effects [53].

Educating patients about their medications and how they need to be taken (preventive vs. abortive, when to administer) can help with adherence (Table 6). Monitoring medication use and headache frequency is an essential part of continued care for migraine patients. Maintain follow up with patients to review how they are doing with the medication and avoid providing refills without visits. The patient may not be taking medication consistently or may be using more medication than prescribed.

What is the role of nonpharmacologic therapy?

Most patients respond to pharmacologic treatment, but some patients with mood disorder, anxiety, difficulties or disability associated with headache, and patients with difficulty managing stress or other triggers may benefit from the addition of behavioral treatments (eg, relaxation, biofeedback, cognitive behavioral therapy, stress management) [54].

Cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness are techniques that have been found to be effective in decreasing intensity of pain and associated disability. The goal of these techniques is to manage the cognitive, affective, and behavioral precipitants of headache. In this process, patients are helped to identify the thoughts and behavior that play a role in generating headache. These techniques have been found to improve many headache-related outcomes like pain intensity, headache-related disability, measures of quality of life, mood and medication consumption [55]. A multidisciplinary intervention that included group exercise, stress management and relaxation lectures, and massage therapy was found to reduce self-perceived pain intensity, frequency, and duration of the headache, and improve functional status and quality of life in migraineurs [56]. A randomized controlled trial of yoga therapy compared with self care showed that yoga led to significant reduction in migraine headache frequency and improved overall outcome [57].

Overall, results from studies of nonpharmacologic techniques have been mixed [58,59]. A systematic review by Sullivan et al found a large range in the efficacy of psychological interventions for migraine [60]. A 2015 systematic review that examined if cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can reduce the physical symptoms of chronic headache and migraines obtained mixed results [58]. Holryod et al’s study [61] found that behavioral management combined with a ß blocker is useful in improving outcomes, but neither the ß blocker alone or behavioral migraine management alone was. Also, a trial by Penzien et al showed that nonpharmacological management helped reduce migraines by 40% to 50% and this was similar to results seen with preventive drugs [62].

Patient education may be helpful in improving outcomes. Smith et al reported a 50% reduction in headache frequency at 12 months in 46% of patients who received migraine education [63]. A randomized controlled trial by Rothrock et al involving 100 migraine patients found that patients who attended a “headache school” consisting of three 90-minute educational sessions focused on topics such as acute treatment and prevention of migraine had a significant reduction in mean migraine disability assessment score (MIDAS) than the group randomized to routine medical management only. The patients also experienced a reduction in functionally incapacitating headache days per month, less need for abortive therapy and were more compliant with prophylactic therapy [64].

Case Conclusion

Our patient is a young woman with a history of headaches suggestive of migraine without aura. Since her headache frequency ranges from 4-8 headaches month, she has episodic migraines. She also has a strong family history of headaches. She denies any other medical or psychiatric comorbidity. She reports an intake of a caffeine-containing medication of 4 to 15 tablets per month.

The physician recommended that she limit her intake of the caffeine-containing medication to 5 days or less per month given the risk of migraine transformation. The physician also recommended maintaining a good sleep schedule, limiting excessive caffeine intake, a stress reduction program, regular cardiovascular exercise, and avoiding skipping or delaying meals. The patient was educated about migraine and its underlying mechanisms and the benefits of taking medications, and her fears regarding medication use and side effects were allayed. Sumatriptan 100 mg oral tablets were prescribed to be taken at headache onset. She was hesitant to be started on an antihypertensive or antiseizure medication, so she was prescribed amitriptyline 30 mg at night for headache prevention. She was also asked to maintain a headache diary. The patient was agreeable with this plan.

Summary

Migraine is often underdiagnosed and undertreated. Primary care providers are often the first point of contact for these patients. Identifying the type and frequency of migraine and comorbidities is necessary to guide appropriate management in terms of medications and lifestyle modifications. Often no testing or imaging is required. Educating patients about this chronic disease, treatment expectations, and limiting intake of medication is essential.

Corresponding author: Pooja Mohan Rao, MBBS, MD, Georgetown University Hospital, 3800 Reservoir Rd. NW, 7 PHC, Washington, DC 20007, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: Dr. Ailani reports receiving honoraria for speaking and consulting for Allergan, Avanir, and Eli Lilly.

1. Woldeamanuel YW, Cowan RP. Migraine affects 1 in 10 people worldwide featuring recent rise: A systematic review and meta-analysis of community-based studies involving 6 million participants, J Neurol Sci 2017;372:307–15.

2. Vetvik KG, MacGregor EA. Sex differences in the epidemiology, clinical features, and pathophysiology of migraine. Lancet Neurol 2017;16:76–87.

3. Lipton RB, Bigal ME. Migraine: epidemiology, impact, and risk factors for progression. Headache 2005;45 Suppl 1:S3–S13.

4. GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016;388:1545–602.

5. Lipton RB, Silberstein SD. Episodic and chronic migraine headache: breaking down barriers to optimal treatment and prevention Headache 2015;55 Suppl 2:103–22.

6. Diamond S, Bigal ME, Silberstein S, et al. Patterns of diagnosis and acute and preventive treatment for migraine in the United States: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention study. Headache 2007;47:355–63.

7. Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, et al. Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study. Lancet 2012;380:2163–96.

8. Lipton RB, Stewart WF, Diamond S, et al. Prevalence and burden of migraine in the United States: data from the American Migraine Study II. Headache 2001;41:646–57.

9. Stewart WF, Ricci JA, Chee E, et al. Lost productive time and cost due to common pain in the US workforce. JAMA 2003;290:2443–54.

10. Hawkins K, Wang S, Rupnow M. Direct cost burden among insured US employees with migraine. Headache 2008;48:553–63.

11. Lipton RB, Serrano D, Holland S, et al. Barriers to the diagnosis and treatment of migraine: Effects of sex, income, and headache features. Headache 2013;53:81–92.

12. Dodick DW, Loder EW, Manack Adams A, et al. Assessing barriers to chronic migraine consultation, diagnosis, and treatment: Results from the chronic migraine epidemiology and outcomes (CaMEO) study. Headache 2016;56:821–34.

13. Young WB, Park JE, Tian IX, Kempner J. The stigma of migraine. PLoS One 2013;8(1):e54074.

14. Mia M, Ashna S, Audrey H. A migraine management training program for primary care providers: an overview of a survey and pilot study findings, lessons learned, and considerations for further research. Headache 2016;56:725–40.

15. Lipton RB, Amatniek JC, Ferrari MD, Gross M. Migraine: identifying and removing barriers to care. Neurology 1994;44(6 Suppl 4):S63–8.

16. Knapp RD Jr. Reports from the past 2. Headache 1963;3:112–22.

17. Levine M, Wolff HG. Cerebral circulation: afferent impulses from the blood vessels of the pia. Arch Neurol Psychiat 1932;28:140.

18. Amin FM, Asghar MS, Hougaard A, et al. Magnetic resonance angiography of intracranial and extracranial arteries in patients with spontaneous migraine without aura: a cross sectional study. Lancet Neurol 2013;12:454–61.

19. Goadsby PJ, Holland PR, Martins-Oliveira M, et al. Pathophysiology of migraine—a disorder of sensory processing. Physiol Rev 2017;97:553–622.

20. Goadsby PJ. Pathophysiology of migraine. Ann Indian Acad Neurol 2012;15(Suppl 1):S15–S22.

21. Puledda F, Messina R, Goadsby PJ, et al. An update on migraine: current understanding and future J Neurol 2017 Mar 20.

22. Vinogradova LV. Comparative potency of sensory-induced brainstem activation to trigger spreading depression and seizures in the cortex of awake rats: implications for the pathophysiology of migraine aura. Cephalalgia 2015;35:979–86.

23. Bahra A, Matharu MS, Buchel C, et al. Brainstem activation specific to migraine headache. Lancet 2001;357:1016–7.

24. Schulte LH, May A. The migraine generator revisited: continuous scanning of the migraine cycle over 30 days and three spontaneous attacks. Brain 2016;139:1987–93.

25. Noseda R, Jakubowski M, Kainz V, et al. Cortical projections of functionally identified thalamic trigeminovascular neurons: implications for migraine headache and its associated symptoms. J Neurosci 2011;31:14204–17.

26. Noseda R, Kainz V, Jakubowski M, et al. A neural mechanism for exacerbation of headache by light. Nat Neurosci 2010;13:239–45.

27. Puledda F, Messina R, Goadsby PJ. An update on migraine: current understanding and future directions. J Neurol 2017 Mar 20.

28. Coppola G, Di Lorenzo C, Schoenen J, Pierelli F. Habituation and sensitization in primary headaches. J Headache Pain 2013;14:65.

29. The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (beta version). Cephalalgia 2013;33:629–808.

30. Yusheng H, Y Li. Typical aura without headache: a case report and review of the literature J Med Case Rep 2015;9:40.

31. Buture A, Khalil M, Ahmed F. Iatrogenic visual aura: a case report and a brief review of the literature Ther Clin Risk Manag 2017;13:643–6.

32. Lipton RB. Tracing transformation: Chronic migraine classification, progression, and epidemiology. Neurology 2009;72:S3–7.

33. Lipton RB. Headache 2011;51;S2:77–83.

34. Scher AI, Stewart WF, et al. Factors associated with the onset and remission of chronic daily headache in a population-based study. Pain 2003;106:81–9.

35. Bigal ME, Lipton RB, Holland PR, Goadsby PJ. Obesity, migraine, and chronic migraine: possible mechanisms of interaction. Neurology 2007;68:1851–61.

36. Wolff HG. Stress and disease. Springfield, IL: Charles C. Thomas; 1953.

37. Guidetti V, Galli F, Fabrizi P, et al. Headache and psychiatric comorbidity: clinical aspects and outcome in an 8-year follow-up study. Cephalalgia 1998;18:455–62.

38. Mongini F, Keller R, Deregibus A, et al. Personality traits, depression and migraine in women: a longitudinal study. Cephalalgia 2003;23:186–92.

39. Hung CI, Liu CY, Yang CH, Wang SJ. The impacts of migraine among outpatients with major depressive disorder at a two-year follow-up. PLoS One 2015;10:e0128087.

40. Frishberg BM, Rosenberg JH, Matchar DB, et al. Evidence-based guidelines in the primary care setting: neuroimaging in patients with nonacute headache. St Paul: US Headache Consortium; 2000.

41. Headache Measurement Set 2014 Revised. American Academy of Neurology. Accessed at www.aan.com/uploadedFiles/Website_Library_Assets/Documents/3.Practice_Management/2.Quality_Improvement/1.Quality_Measures/1.All_Measures/2014.

42. Taylor FR. Lifestyle changes, dietary restrictions, and nutraceuticals in migraine prevention. Techn Reg Anesth Pain Manage 2009;13:28–37.

43. Varkey E, Cider A, Carlsson J, Linde M. Exercise as migraine prophylaxis: A randomized study using relaxation and topiramate as controls. Cephalalgia 2011;14:1428–38.

44. Ahn AH. Why does increased exercise decrease migraine? Curr Pain Headache Rep 2013;17:379.

45. Marmura MJ, Silberstein SD, Schwedt TJ. The acute treatment of migraine in adults: The American Headache Society evidence assessment of migraine pharmacotherapies. Headache 2015;55:3–20.

46. Belvis R, Mas N, Aceituno A. Migraine attack treatment : a tailor-made suit, not one size fits all. Recent Pat CNS Drug Discov 2014;9:26–40.

47. Bigal ME, Serrano D, Buse D, et al. Acute migraine medications and evolution from episodic to chronic migraine: A longitudinal population-based study. Headache 2008;48:1157–68.

48. Bigal ME, Rapoport AM, Sheftell FD, et al. Transformed migraine and medication overuse in a tertiary headache centre--clinical characteristics and treatment outcomes Cephalalgia 2004;24:483–90.

49. Silberstein SD, Holland S, Freitag F, et al; Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Evidence-based guideline update: pharmacologic treatment for episodic migraine prevention in adults: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology and the American Headache Society. Neurology 2012;78:1337–45.

50. Diener HC, Dodick DW, Aurora SK, et al. OnabotulinumtoxinA for treatment of chronic migraine: Results from the double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled phase of the PREEMPT 2 trial Cephalagia year;30:804–14.

51. Wells RE, Markowitz SY, Baron EP, et al. Identifying the factors underlying discontinuation of triptans. Headache 2014;54:278–89.

52. Holland S, Fanning KM, Serrano D, et al. Rates and reasons for discontinuation of triptans and opioids in episodic migraine: results from the American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study. J Neurol Sci 2013;326:10–7.

53. Seng EK, Rains JA, Nicholson RA, Lipton RB. Improving medication adherence in migraine treatment. Curr Pain Headache Rep 2015;19:24.

54. Nicholson RA, Buse DC, Andrasik F, Lipton RB. Nonpharmacologic treatments for migraine and tension-type headache: how to choose and when to use. Curr Treatment Opt Neurol 2011;13:28–40.

55. Probyn K, Bowers H, Mistry D, et al. Non-pharmacological self-management for people living with migraine or tension-type headache: a systematic review including analysis of intervention components BMJ Open 2017;7:e016670.

56. Lemstra M, Stewart B, Olszynski WP. Effectiveness of multidisciplinary intervention in the treatment of migraine: a randomized clinical trial. Headache 2002;42:845–54.

57. John PJ, Sharma N, Sharma CM, Kankane A. Effectiveness of yoga therapy in the treatment of migraine without aura: a randomized controlled trial. Headache 2007;47:654–61.

58. Harris P, Loveman E, Clegg A, et al. Systematic review of cognitive behavioural therapy for the management of headaches and migraines in adults Br J Pain 2015;9:213–24.

59. Kropp P, Meyer B, Meyer W, Dresler T. An update on behavioral treatments in migraine - current knowledge and future options. Expert Rev Neurother 2017:1–10.

60. Sullivan A, Cousins S, Ridsdale L. Psychological interventions for migraine: a systematic review. J Neurol 2016;263:2369–77.

61. Holroyd KA, Cottrell CK, O’Donnell FJ, et al. Effect of preventive (beta blocker) treatment, behavioural migraine management, or their combination on outcomes of optimised acute treatment in frequent migraine: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 2010;341:c4871.

62. Penzien DB, Rains JC, Andrasik F. Behavioral management of recurrent headache: three decades of experience and empiricism. Appl Psychophysiol Biofeedback 2002;27:163–81.

63. Smith TR, Nicholson RA, Banks JW. A primary care migraine education program has benefit on headache impact and quality of life: results from the mercy migraine management program. Headache 2010;50:600–12.

64. Rothrock JF, Parada VA, Sims C, et al.The impact of intensive patient education on clinical outcome in a clinic-based migraine population. Headache 2006;46:726–31.

From the Department of Neurology, Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC.

Abstract

- Objective: To review the epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of migraine.

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: Migraine is a common disorder associated with significant morbidity. Diagnosis of migraine is performed according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders. Comorbidities are commonly seen with migraine and include mood disorders (depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder), musculoskeletal disorders (neck pain, fibromyalgia, Ehlors-Danlos syndrome), sleep disorders, asthma, allergies, thyroid dysfunction, obesity, irritable bowel syndrome, epilepsy, stroke, and heart disease. Comorbid conditions can increase migraine disability. Management of migraine with lifestyle modifications, trigger management, and acute and preventive medications can help reduce the frequency, duration, and severity of attacks. Overuse of medications such as opiates, barbiturates, and caffeine-containing medications can increase headache frequency. Educating patients about limiting use of these medications is important.

- Conclusion: Migraine is a common neurologic disease that can be very disabling. Recognizing the condition, making an accurate diagnosis, and starting patients on migraine-specific treatments can help improve patient outcomes.

Migraine is a common neurologic disease that affects 1 in 10 people worldwide [1]. It is 2 to 3 times more prevalent in women than in men [2]. The prevalence of migraine peaks in both sexes during the most productive years of adulthood (age 25 to 55 years) [3]. The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study considers it to be the 7th most disabling disease in the world [4]. Over 36 million people in the United States have migraine [5]. However, just 56% of migraineurs have ever been diagnosed [6].

Migraine is associated with a high rate of years lived with disability [7] and the rate has been steadily increasing since 1990. At least 50% of migraine sufferers are severely disabled, many requiring bed rest, during individual migraine attacks lasting hours to days [8]. The total U.S. annual economic costs from headache disorders, including the indirect costs from lost productivity and workplace performance, has been estimated at $31 billion [9,10].

Despite the profound impact of migraine on patients and society, there are numerous barriers to migraine care. Lipton et al [11] identified 3 steps that were minimally necessary to achieve guideline-defined appropriate acute pharmacologic therapy: (1) consulting a prescribing health care professional; (2) receiving a migraine diagnosis; and (3) using migraine-specific or other appropriate acute treatments. In a study they conducted in patients with episodic migraine, 45.5% had consulted health care professional for headache in the preceding year; of these, 86.7% reported receiving a medical diagnosis of migraine, and among the diagnosed consulters, 66.7% currently used acute migraine-specific treatments, resulting in only 26.3% individuals successfully completing all 3 steps. In the recent CaMEO study [12], the proportion patients with chronic migraine that overcame all 3 barriers was less than 5%.

The stigma of migraine often makes it difficult for people to discuss symptoms with their health care providers and family members [13]. When they do discuss their headaches with their provider, often they are not given a diagnosis [14] or do not understand what their diagnosis means [15]. It is important for health care providers to be vigilant about the diagnosis of migraine, discuss treatment goals and strategies, and prescribe appropriate migraine treatment. Migraine is often comorbid with a number of medical, neurological, and psychiatric conditions, and identifying and managing comorbidities is necessary to reduce headache burden and disability. In this article, we provide a review of the diagnosis and treatment of migraine, using a case illustration to highlight key points.

Case Study

Initial Presentation

A 24-year-old woman presents for an evaluation of her headaches.

History and Physical Examination

She initially noted headaches at age 19, which were not memorable and did not cause disability. Her current headaches are a severe throbbing pain over her right forehead. They are associated with light and sound sensitivity and stomach upset. Headaches last 6 to 7 hours without medications and occur 4 to 8 days per month.

She denies vomiting and autonomic symptoms such as runny nose or eye tearing. She also denies preceding aura. She reports headache relief with intake of tablets that contain acetaminophen/aspirin/caffeine and states that she takes between 4 to 15 tablets/month depending on headache frequency. She reports having tried acetaminophen and naproxen with no significant benefit. Aggravating factors include bright lights, strong smells, and soy/ high-sodium foods.

She had no significant past medical problems and denied a history of depression or anxiety. Family history was significant for both her father and sister having a history of headaches. The patient lived alone and denied any major life stressors. She exercises 2 times a week and denies smoking or alcohol use. Review of systems was positive for trouble sleeping, which she described as difficulty falling asleep.

On physical examination, vitals were within normal limits. BMI was 23. Chest, cardiac, abdomen, and general physical examination were all within normal limits. Neurological examination revealed no evidence of papilledema or focal neurological deficits.

What is the pathophysiology of migraine?

Migraine was thought to be a primary vascular disorder of the brain, with the origins of the vascular theory of migraine dating back to 1684 [16]. Trials performed by Wolff concluded that migraine is of vascular origin [17], and this remained the predominant theory over several decades. Current evidence suggests that migraine is unlikely to be a pure vascular disorder and instead may be related to changes in the central or peripheral nervous system [18,19].

Migraine is complex brain network disorder with a strong genetic basis [19]. The trigemino-vascular system, along with neurogenically induced inflammation of the dura mater, mast cell degranulation and release of histamine, are the likely causes of migraine pain. Trigeminal fibers arise from neurons in the trigeminal ganglion that contain substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) [20]. CGRP is a neuropeptide widely expressed in both peripheral and central neurons. Elevation of CGRP in migraine is linked to diminution of the inhibitory pathways which in turn leads to migraine susceptibility [21]. These findings have led to the development of new drugs that target the CGRP pathway.

In the brainstem, periaqueductal grey matter and the dorsolateral pons have been found to be “migraine generators,” or the driver of changes of cortical activity during migraine [22]. Brainstem nuclei are involved in modulating trigemino-vascular pain transmission and autonomic responses in migraine [23].

The hypothalamus has also been implicated in migraine pathogenesis, particularly its role in nociceptive and autonomic modulation in migraine patients. Schulte and May hypothesized that there is a network change between the hypothalamus and the areas of the brainstem generator leading to the migraine attacks [24].

The thalamus plays a central role for the processing and integration of pain stimuli from the dura mater and cutaneous regions. It maintains complex connections with the somatosensory, motor, visual, auditory, olfactory and limbic regions [25]. The structural and functional alterations in the system play a role in the development of migraine attacks, and also in the sensory hypersensitivity to visual stimuli and mechanical allodynia [26].

Experimental studies in rats show that cortical spreading depression can trigger neurogenic meningeal inflammation and subsequently activate the trigemino-vascular system [27]. It has been observed that between migraine episodes a time-dependent amplitude increase of scalp-evoked potentials to repeated stereotyped stimuli, such as visual, auditory, and somaticstimuli, occurs. This phenomenon is described as “deficient habituation.” In episodic migraine, studies show 2 characteristic changes: a deficient habituation between attacks and sensitization during the attack [28]. Genetic studies have hypothesized an involvement of glutamatergic neurotransmitters and synaptic dysplasticity in causing abnormal cortical excitability in migraine [27].

What are diagnostic criteria for migraine?

Diagnosis of migraine is performed according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders (ICHD) [29]. Based on the number of headache days that the patient reports, migraine is classified into episodic or chronic migraine. Migraines that occur on fewer than 15 days/month are categorized as episodic migraines.

Episodic migraine is divided into 2 categories: migraine with aura (Table 1) and migraine without aura. Migraine without aura is described as recurrent headaches consisting of at least 5 attacks, each lasting 4 to 72 hours if left untreated. At least 2 of the following 4 characteristics must be present: unilateral location, pulsating quality, moderate or severe pain intensity, with aggravation by or causing avoidance of routine physical activity. During headache, at least 1 of nausea and/or vomiting or photophobia and phonophobia should be present.

In migraine with aura (Table 2), headache characteristics are the same, but in addition there are at least 2 lifetime attacks with fully reversible aura symptoms (visual, sensory, speech/language). In addition, these auras have at least 2 of the following 4 characteristics: at least 1 aura symptom spreads gradually over 5 minutes, and/or 2 or more symptoms occur in succession; each individual aura symptom lasts 5 to 60 minutes; aura symptom is unilateral; and aura is accompanied, or followed within 60 minutes, by headache. Migraine with aura is uncommon, occurring in 20% of patients with migraine [30]. Visual aura is the most common type of aura, occurring in up to 90% of patients [31]. There is also aura without migraine, called typical aura without headache. Patients can present with non-migraine headache with aura, categorized as typical aura with headache [29].

Headache occurring on 15 or more days per month for more than 3 months, which has the features of migraine headache on at least 8 days per month, is classified as chronic migraine (Table 3). Evidence indicates that 2.5% of episodic migraine progresses to chronic migraine over 1-year follow-up [32]. There are several risk factors for chronification of migraine. Nonmodifiable factors include female sex, white European heritage, head/neck injury, low education/socioeconomic status, and stressful life events (divorce, moving, work changes, problems with children). Modifiable risk factors are headache frequency, acute medication overuse, caffeine overuse, obesity, comorbid mood disorders, and allodynia. Acute medication use and headache frequency are independent risk factors for development of chronic migraine [33]. The risk of chronic migraine increases exponentially with increased attack frequency, usually when the frequency is ≥ 3 headaches/month. Repetitive episodes of pain may increase central sensitization and result in anatomical changes in the brain and brainstem [34].

What information should be elicited during the history?

Specific questions about the headaches can help with making an accurate diagnosis. These include:

- Length of attacks and their frequency

- Pain characteristics (location, quality, intensity)

- Actions that trigger or aggravate headaches (eg, stress, movement, bright lights, menses, certain foods and smells)

- Associated symptoms that accompany headaches (eg, nausea, vomiting)

- How the headaches impact their life (eg, missed days at work or school, missed life events, avoidance of social activities, emergency room visits due to headache)

To assess headache frequency, it is helpful to ask about the number of headache-free days in a month, eg, “how many days a month do you NOT have a headache.” To assist with headache assessment, patients can be asked to keep a calendar in which they mark days of use of medications, including over the counter medications, menses, and headache days. The calendar can be used to assess for migraine patterns, headache frequency, and response to treatment.

When asking about headache history, it is important for patients to describe their untreated headaches. Patients taking medications may have pain that is less severe or disabling or have reduced associated symptoms. Understanding what the headaches were like when they did not treat is important in making a diagnosis.

Other important questions include when was the first time they recall ever experiencing a headache. Migraine is often present early in life, and understanding the change in headache over time is important. Also ask patients about what they want to do when they have a headache. Often patients want to lie down in a cool dark room. Ask what they would prefer to do if they didn’t have any pending responsibilities.

Comorbidities

Comorbidities are commonly seen with migraine. Common comorbidities are mood disorders (depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder), musculoskeletal disorders (neck pain, fibromyalgia, Ehlors-Danlos syndrome), sleep disorders, asthma, allergies, thyroid dysfunction, obesity, irritable bowel syndrome, epilepsy, stroke, and heart disease.

Comorbid conditions can increase migraine disability and also can provide information about the pathophysiology of migraine and guide treatment. Management of the underlying comorbidity often leads to improved migraine outcomes. For example, serotonergic dysfunction is a possible pathway involved in both migraine and mood disorders. Treatment with medications that alter the serotonin system may help both migraine and coexisting mood disorders. Bigal et al proposed that activation of the HPA axis with reduced serotonin synthesis is a main pathway involved in affective disorders, migraine, and obesity [35].

In the early 1950s, Wolff conceptualized migraine as a psychophysiologic disorder [36]. The relationship between migraine and psychiatric conditions is complex, and comorbid psychiatric disorders are risk factors for headache progression and chronicity. Psychiatric conditions also play a role in nonadherence to headache medication, which contributes to poor outcome in these patients. Hence, there is a need for assessment and treatment of psychiatric disorders in people with migraine. A study by Guidetti et al found that headache patients with multiple psychiatric conditions have poor outcomes, with 86 % of these headache patients having no improvement and even deterioration in their headache [37]. Another study by Mongini et al concluded that psychiatric disorder appears to influence the result of treatment on a long-term basis [38].

In addition, migraine has been shown to impact mood disorders. Worsening headache was found to be associated with poorer prognosis for depression. Patients with active migraine not on medications with comorbid major depressive disorder (MDD) had more severe anxiety and somatic symptoms as compared with MDD patients without migraine [39].

Case Continued

Our patient has a normal neurologic examination and classic migraine headache history and stable frequency. The physician tells her she meets criteria for episodic migraine without aura. The patient asks if she needs a “brain scan” to see if something more serious may be causing her symptoms.

What workup is recommended for patients with migraine?

If patient symptoms fit the criteria for migraine and there is a normal neurologic examination, the differential is often limited. When there are neurologic abnormalities on examination (eg, papilledema), or if the patient has concerning signs or symptoms (see below), then neuroimaging should be obtained to rule out secondary causes of headache.

In 2014, the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) published practice parameters on the evaluation of adults with recurrent headache based on guidelines published by the US Headache Consortium [40]. As per AAN guidelines, routine laboratory studies, lumbar puncture, and electroencephalogram are not recommended in the evaluation of non-acute migraines. Neuroimaging is not warranted in patients with migraine and a normal neurologic examination (grade B recommendation). Imaging may need to be considered in patients with non-acute headache and an unexplained abnormal finding on the neurologic examination (grade B recommendation).

When patients exhibit particular warning signs, or headache “red flags,” it is recommended that neuroimaging be considered. Red flags include patients with recurrent headaches and systemic symptoms (fever, weight loss), neurologic symptoms or abnormal signs (confusion, impaired alertness or consciousness), sudden onset, abrupt, or split second in nature, patients age > 50 with new onset or progressive headache, previous headache history with new or different headache (change in frequency, severity, or clinical features) and if there are secondary risk factors (HIV, cancer) [41].

Case Continued

Our patient has no red flags and can be reassured that given her normal physical examination and history suggestive of a migraine, a secondary cause of her headache is unlikely. The physician describes the treatments available, including implementing lifestyles changes and preventive and abortive medications. The patient expresses apprehension about being on prescription medications. She is concerned about side effects as well as the need to take daily medication over a long period of time. She reports that these were the main reasons she did not take the rizatriptan and propranolol that was prescribed by her previous doctor.

How is migraine treated?

Migraine is managed with a combination of lifestyle changes and pharmacologic therapy. Pharmacologic management targets treating an attack when it occurs (abortive medication), as well as reducing the frequency and severity of future attacks (preventive medication).

Lifestyle Changes

Patients should be advised that making healthy lifestyle choices, eg, regular sleep, balanced meals, proper hydration, and regular exercise, can mitigate migraine [42–44]. Other lifestyle changes that can be helpful include weight loss in the obese population, as weight loss appears to result in migraine improvement. People who are obese also are at higher risk for the progression to chronic migraine.

Acute Therapy

There are varieties of abortive therapies [45] (Table 4) that are commonly used in clinical practice. Abortive therapy can be taken as needed and is most effective if used within the first 2 hours of headache. For patients with daily or frequent headache, these medications need to be restricted to 8 to 12 days a month of use and their use should be restricted to when headache is worsening. This usually works well in patients with moderate level pain, and especially in patients with no associated nausea. Selective migraine treatments, like triptans and ergots, are used when nonspecific treatments fail, or when headache is more severe. It is preferable that patients avoid opioids, butalbital, and caffeine-containing medications. In the real world, it is difficult to convince patient to stop these medications; it is more realistic to discuss use limitation with patients, who often run out their weekly limit for triptans.

Triptans are effective medications for acute management of migraine but headache recurrence rate is high, occurring in 15% to 40 % of patients taking oral triptans. It is difficult to predict the response to a triptan [46]. The choice of an abortive agent is often directed partially by patient preference (side effect profile, cost, non-sedating vs. prefers to sleep, long vs short half-life), comorbid conditions (avoid triptans and ergots in uncontrolled hypertension, cardiovascular disease, or peripheral vascular disease or stroke/aneurysm; avoid NSAIDS in patients with cardiovascular disease), and migraine-associated symptoms (nausea and/or vomiting). Consider non-oral formulations via subcutaneous or nasal routes in patients who have nausea or vomiting with their migraine attacks. Some patients may require more than one type of abortive medication. The high recurrence rate is similar across different triptans and so switching from one triptan to another has not been found to be useful. Adding NSAIDS to triptans has been found to be more useful than switching between triptans.Overuse of acute medications has been associated with transformation of headache from episodic to chronic (medication overuse headache or rebound headache). The risk of transformation appears to be greatest with medications containing caffeine, opiates, or barbiturates [47]. Use of acute medications should be limited based on the type of medication. Patients should take triptans for no more than 10 days a month. Combined medications and opioids should be used fewer than 8 days a month, and butalbital-containing medications should be avoided or used fewer than 5 days a month [48]. Use of acute therapy should be monitored with headache calendars. It is unclear if and to what degree NSAIDS and acetaminophen cause overuse headaches.

Medication overuse headache can be difficult to treat as patients have to stop using the medication causing rebound. Further, headaches often resemble migraine and it can be difficult to differentiate them from the patients’ routine headache. Vigilance with medication use in patients with frequent headache is an essential part of migraine management, and patients should receive clear instructions regarding how to use acute medications.

Prevention

Patients presenting with more than 4 headaches per month, or headaches that last longer than 12 hours, require preventive therapy. The goals of preventive therapy is to reduce attack frequency, severity, and duration, to improve responsiveness to treatment of acute attacks, to improve function and reduce disability, and to prevent progression or transformation of episodic migraine to chronic migraine. Preventive medications usually need to be taken daily to reduce frequency or severity of the headache. The goal in this approach is 50% reduction of headache frequency and severity. Migraine preventive medications usually belong to 1 of 3 categories of drugs: antihypertensives, antiepileptics, and antidepressants. At present there are many medications for migraine prevention with different levels of evidence [49] (Table 5). Onabotulinuma toxin is the only approved medication for chronic migraine based on promising results of the PREEMPT trial [50].

Other Considerations

A multidisciplinary approach to treatment may be warranted. Psychiatric evaluation and management of underlying depression and mood disorders can help reduce headache frequency and severity. Physical therapy should be prescribed for neck and shoulder pain. Sleep specialists should be consulted if ongoing sleep issues continue despite behavioral management.

How common is nonadherence with migraine medication?

One third of patients who are prescribed triptans discontinue the medication within a year. Lack of efficacy and concerns over medication side effects are 2 of the most common reasons for poor adherence [51]. In addition, age plays a significant role in discontinuing medication, with the elderly population more likely to stop taking triptans [52]. Seng et al reported that among patients with migraine, being male, being single, having frequent headache, and having mild pain are all associated with medication nonadherence [53]. Formulary restrictions and type of insurance coverage also were associated with nonadherence. Among adherent patients, some individuals were found to be hoarding their tablets and waiting until they were sure it was a migraine. Delaying administration of abortive medications increases the chance of incomplete treatment response, leading to patients taking more medication and in turn have more side effects [53].

Educating patients about their medications and how they need to be taken (preventive vs. abortive, when to administer) can help with adherence (Table 6). Monitoring medication use and headache frequency is an essential part of continued care for migraine patients. Maintain follow up with patients to review how they are doing with the medication and avoid providing refills without visits. The patient may not be taking medication consistently or may be using more medication than prescribed.

What is the role of nonpharmacologic therapy?

Most patients respond to pharmacologic treatment, but some patients with mood disorder, anxiety, difficulties or disability associated with headache, and patients with difficulty managing stress or other triggers may benefit from the addition of behavioral treatments (eg, relaxation, biofeedback, cognitive behavioral therapy, stress management) [54].

Cognitive behavioral therapy and mindfulness are techniques that have been found to be effective in decreasing intensity of pain and associated disability. The goal of these techniques is to manage the cognitive, affective, and behavioral precipitants of headache. In this process, patients are helped to identify the thoughts and behavior that play a role in generating headache. These techniques have been found to improve many headache-related outcomes like pain intensity, headache-related disability, measures of quality of life, mood and medication consumption [55]. A multidisciplinary intervention that included group exercise, stress management and relaxation lectures, and massage therapy was found to reduce self-perceived pain intensity, frequency, and duration of the headache, and improve functional status and quality of life in migraineurs [56]. A randomized controlled trial of yoga therapy compared with self care showed that yoga led to significant reduction in migraine headache frequency and improved overall outcome [57].

Overall, results from studies of nonpharmacologic techniques have been mixed [58,59]. A systematic review by Sullivan et al found a large range in the efficacy of psychological interventions for migraine [60]. A 2015 systematic review that examined if cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) can reduce the physical symptoms of chronic headache and migraines obtained mixed results [58]. Holryod et al’s study [61] found that behavioral management combined with a ß blocker is useful in improving outcomes, but neither the ß blocker alone or behavioral migraine management alone was. Also, a trial by Penzien et al showed that nonpharmacological management helped reduce migraines by 40% to 50% and this was similar to results seen with preventive drugs [62].

Patient education may be helpful in improving outcomes. Smith et al reported a 50% reduction in headache frequency at 12 months in 46% of patients who received migraine education [63]. A randomized controlled trial by Rothrock et al involving 100 migraine patients found that patients who attended a “headache school” consisting of three 90-minute educational sessions focused on topics such as acute treatment and prevention of migraine had a significant reduction in mean migraine disability assessment score (MIDAS) than the group randomized to routine medical management only. The patients also experienced a reduction in functionally incapacitating headache days per month, less need for abortive therapy and were more compliant with prophylactic therapy [64].

Case Conclusion

Our patient is a young woman with a history of headaches suggestive of migraine without aura. Since her headache frequency ranges from 4-8 headaches month, she has episodic migraines. She also has a strong family history of headaches. She denies any other medical or psychiatric comorbidity. She reports an intake of a caffeine-containing medication of 4 to 15 tablets per month.

The physician recommended that she limit her intake of the caffeine-containing medication to 5 days or less per month given the risk of migraine transformation. The physician also recommended maintaining a good sleep schedule, limiting excessive caffeine intake, a stress reduction program, regular cardiovascular exercise, and avoiding skipping or delaying meals. The patient was educated about migraine and its underlying mechanisms and the benefits of taking medications, and her fears regarding medication use and side effects were allayed. Sumatriptan 100 mg oral tablets were prescribed to be taken at headache onset. She was hesitant to be started on an antihypertensive or antiseizure medication, so she was prescribed amitriptyline 30 mg at night for headache prevention. She was also asked to maintain a headache diary. The patient was agreeable with this plan.

Summary

Migraine is often underdiagnosed and undertreated. Primary care providers are often the first point of contact for these patients. Identifying the type and frequency of migraine and comorbidities is necessary to guide appropriate management in terms of medications and lifestyle modifications. Often no testing or imaging is required. Educating patients about this chronic disease, treatment expectations, and limiting intake of medication is essential.

Corresponding author: Pooja Mohan Rao, MBBS, MD, Georgetown University Hospital, 3800 Reservoir Rd. NW, 7 PHC, Washington, DC 20007, [email protected].

Financial disclosures: Dr. Ailani reports receiving honoraria for speaking and consulting for Allergan, Avanir, and Eli Lilly.

From the Department of Neurology, Medstar Georgetown University Hospital, Washington, DC.

Abstract

- Objective: To review the epidemiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment of migraine.

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: Migraine is a common disorder associated with significant morbidity. Diagnosis of migraine is performed according to the International Classification of Headache Disorders. Comorbidities are commonly seen with migraine and include mood disorders (depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder), musculoskeletal disorders (neck pain, fibromyalgia, Ehlors-Danlos syndrome), sleep disorders, asthma, allergies, thyroid dysfunction, obesity, irritable bowel syndrome, epilepsy, stroke, and heart disease. Comorbid conditions can increase migraine disability. Management of migraine with lifestyle modifications, trigger management, and acute and preventive medications can help reduce the frequency, duration, and severity of attacks. Overuse of medications such as opiates, barbiturates, and caffeine-containing medications can increase headache frequency. Educating patients about limiting use of these medications is important.

- Conclusion: Migraine is a common neurologic disease that can be very disabling. Recognizing the condition, making an accurate diagnosis, and starting patients on migraine-specific treatments can help improve patient outcomes.

Migraine is a common neurologic disease that affects 1 in 10 people worldwide [1]. It is 2 to 3 times more prevalent in women than in men [2]. The prevalence of migraine peaks in both sexes during the most productive years of adulthood (age 25 to 55 years) [3]. The Global Burden of Diseases, Injuries, and Risk Factors Study considers it to be the 7th most disabling disease in the world [4]. Over 36 million people in the United States have migraine [5]. However, just 56% of migraineurs have ever been diagnosed [6].

Migraine is associated with a high rate of years lived with disability [7] and the rate has been steadily increasing since 1990. At least 50% of migraine sufferers are severely disabled, many requiring bed rest, during individual migraine attacks lasting hours to days [8]. The total U.S. annual economic costs from headache disorders, including the indirect costs from lost productivity and workplace performance, has been estimated at $31 billion [9,10].

Despite the profound impact of migraine on patients and society, there are numerous barriers to migraine care. Lipton et al [11] identified 3 steps that were minimally necessary to achieve guideline-defined appropriate acute pharmacologic therapy: (1) consulting a prescribing health care professional; (2) receiving a migraine diagnosis; and (3) using migraine-specific or other appropriate acute treatments. In a study they conducted in patients with episodic migraine, 45.5% had consulted health care professional for headache in the preceding year; of these, 86.7% reported receiving a medical diagnosis of migraine, and among the diagnosed consulters, 66.7% currently used acute migraine-specific treatments, resulting in only 26.3% individuals successfully completing all 3 steps. In the recent CaMEO study [12], the proportion patients with chronic migraine that overcame all 3 barriers was less than 5%.

The stigma of migraine often makes it difficult for people to discuss symptoms with their health care providers and family members [13]. When they do discuss their headaches with their provider, often they are not given a diagnosis [14] or do not understand what their diagnosis means [15]. It is important for health care providers to be vigilant about the diagnosis of migraine, discuss treatment goals and strategies, and prescribe appropriate migraine treatment. Migraine is often comorbid with a number of medical, neurological, and psychiatric conditions, and identifying and managing comorbidities is necessary to reduce headache burden and disability. In this article, we provide a review of the diagnosis and treatment of migraine, using a case illustration to highlight key points.

Case Study

Initial Presentation

A 24-year-old woman presents for an evaluation of her headaches.

History and Physical Examination

She initially noted headaches at age 19, which were not memorable and did not cause disability. Her current headaches are a severe throbbing pain over her right forehead. They are associated with light and sound sensitivity and stomach upset. Headaches last 6 to 7 hours without medications and occur 4 to 8 days per month.

She denies vomiting and autonomic symptoms such as runny nose or eye tearing. She also denies preceding aura. She reports headache relief with intake of tablets that contain acetaminophen/aspirin/caffeine and states that she takes between 4 to 15 tablets/month depending on headache frequency. She reports having tried acetaminophen and naproxen with no significant benefit. Aggravating factors include bright lights, strong smells, and soy/ high-sodium foods.

She had no significant past medical problems and denied a history of depression or anxiety. Family history was significant for both her father and sister having a history of headaches. The patient lived alone and denied any major life stressors. She exercises 2 times a week and denies smoking or alcohol use. Review of systems was positive for trouble sleeping, which she described as difficulty falling asleep.

On physical examination, vitals were within normal limits. BMI was 23. Chest, cardiac, abdomen, and general physical examination were all within normal limits. Neurological examination revealed no evidence of papilledema or focal neurological deficits.

What is the pathophysiology of migraine?

Migraine was thought to be a primary vascular disorder of the brain, with the origins of the vascular theory of migraine dating back to 1684 [16]. Trials performed by Wolff concluded that migraine is of vascular origin [17], and this remained the predominant theory over several decades. Current evidence suggests that migraine is unlikely to be a pure vascular disorder and instead may be related to changes in the central or peripheral nervous system [18,19].

Migraine is complex brain network disorder with a strong genetic basis [19]. The trigemino-vascular system, along with neurogenically induced inflammation of the dura mater, mast cell degranulation and release of histamine, are the likely causes of migraine pain. Trigeminal fibers arise from neurons in the trigeminal ganglion that contain substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) [20]. CGRP is a neuropeptide widely expressed in both peripheral and central neurons. Elevation of CGRP in migraine is linked to diminution of the inhibitory pathways which in turn leads to migraine susceptibility [21]. These findings have led to the development of new drugs that target the CGRP pathway.

In the brainstem, periaqueductal grey matter and the dorsolateral pons have been found to be “migraine generators,” or the driver of changes of cortical activity during migraine [22]. Brainstem nuclei are involved in modulating trigemino-vascular pain transmission and autonomic responses in migraine [23].

The hypothalamus has also been implicated in migraine pathogenesis, particularly its role in nociceptive and autonomic modulation in migraine patients. Schulte and May hypothesized that there is a network change between the hypothalamus and the areas of the brainstem generator leading to the migraine attacks [24].

The thalamus plays a central role for the processing and integration of pain stimuli from the dura mater and cutaneous regions. It maintains complex connections with the somatosensory, motor, visual, auditory, olfactory and limbic regions [25]. The structural and functional alterations in the system play a role in the development of migraine attacks, and also in the sensory hypersensitivity to visual stimuli and mechanical allodynia [26].