User login

Approach to Peripheral Neuropathies

Early diagnosis of peripheral neuropathies can lead to life‐saving or limb‐saving intervention. While infrequently a cause for concern in the hospital setting, peripheral neuropathies are commonoccurring in up to 10% of the general population.1 The hospitalist needs to expeditiously identify acute and life‐threatening or limb‐threatening causes among an immense set of differentials. Fortunately, with an informed and careful approach, most neuropathies in need of urgent intervention can be readily identified. A thorough history and examination, with the addition of electrodiagnostic testing, comprise the mainstays of this process. Inpatient neurology consultation should be sought for any rapidly progressing or acute onset neuropathy. The aim of this review is to equip the general hospitalist with a solid framework for efficiently evaluating peripheral neuropathies in urgent cases.

Literature Review

Search Strategy

A PubMed search was conducted using the title word peripheral, the medical subject heading major topic peripheral nervous system diseases/diagnosis, and algorithm or diagnosis, differential or diagnostic techniques, neurological or neurologic examination or evaluation or evaluating. The search was limited to English language review articles published between January 2002 and November 2007. Articles were included in this review if they provided an overview of an approach to the diagnosis of peripheral neuropathies. References listed in these articles were cross‐checked and additional articles meeting these criteria were included. Articles specific to subtypes of neuropathies or diagnostic tools were excluded.

Search Results

No single guideline or algorithm has been widely endorsed for the approach to diagnosing peripheral neuropathies. Several are suggested in the literature, but none are directed at the hospitalist. In general, acute and multifocal neuropathies are characterized as neurologic emergencies requiring immediate evaluation.2, 3

Several articles underscore the importance of pattern recognition in diagnosing peripheral neuropathies.2, 4, 5 Many articles present essential questions in evaluating peripheral neuropathy; some suggest an ordered approach.13, 511 The nature of these questions and recommended order of inquiry varies among authors (Table 1). Three essentials common to all articles include: 1) noting the onset of symptoms; 2) determining the distribution of nerve involvement; and 3) identifying the pathology as axonal, demyelinating, or mixed. All articles underscore the importance of the physical examination in determining and confirming distribution and nerve type. A thorough examination evaluating for systemic signs of etiologic possibilities is strongly recommended. Electrodiagnostic testing provides confirmation of the distribution of nerve involvement and further characterizes a neuropathy as demyelinating, axonal, or mixed.

| Article (Publication Year) | Essentials of Recommended Approach |

|---|---|

| Lunn3 (2007) | Details 6 essential questions in the history, highlighting: 1. Temporal evolution; 2. Autonomic involvement; 3. Nerve involvement (sensory/motor); 4. Cranial nerve involvement; 5. Family history; and 6. Coexistent disease |

| Examination should confirm findings expected from history | |

| Acute and multifocal neuropathies merit urgent evaluation | |

| Electrodiagnostic testing and neurology consultation should ensue if no diagnosis identified from above | |

| Burns et al.6 (2006) | Focuses on evaluation of polyneuropathy |

| Poses 4 questions: 1. Nerve involvement (sensory/motor); 2. Distribution; 3. Onset; 4. Associated factors (family history, exposures, associated systemic symptoms) | |

| Recommends electrodiagnostic testing | |

| Laboratory testing as indicated | |

| Scott and Kothari5 (2005) | Highlights importance of pattern recognition in the history and on examination |

| Ordered approach: 1. Localize site of neuropathic lesion, 2. Perform electrodiagnostic testing to determine pathology | |

| Bromberg1 (2005) | Proposes 7 layers to consider in investigation: 1. Localizing to peripheral nervous system; 2. Distribution; 3. Onset; 4. Nerve involvement (sensory/motor); 5. Pathology (axonal/demyelinating); 6. Other associated features; and 7. Epidemiologic features |

| Kelly4 (2004) | Highlights pattern recognition and features distribution, onset, and pathology in developing the differential diagnosis |

| Younger10 (2004) | Several key elements, including: timing, nerve involvement (sensory/motor/autonomic), distribution, and pathology (axonal/demyelinating) |

| England and Asbury7 (2004) | Details to determine: 1. Distribution; 2. Pathology (axonal/demyelinating); and 3. Timing |

| Smith and Bromberg9 (2003) | Suggest an algorithm: 1. Confirm the localization (history, examination and electrodiagnostic testing); 2. Identify atypical patterns; and 3. Recognize prototypic neuropathy and perform focused laboratory testing |

| Bromberg and Smith11 (2002) | 4 basic steps: 1. Nerve involvement (sensory/motor); 2. Distribution; 3. Timing; and 4. Pathology (axonal/demyelinating) |

| Hughes2 (2002) | Pattern recognition |

| Suggests staged investigation: 1. Basic laboratory tests; 2. Electrodiagnostic testing and further laboratory tests; and 3. Additional laboratory tests, imaging, and specialized testing | |

| Pourmand8 (2002) | Offers 7 key questions/steps highlighting: 1. Onset; 2. Course; 3. Distribution; 4. Nerve involvement (sensory/motor); 5. Nerve fiber type (large/small); 6. Autonomic involvement; and 7. Pathology (axonal/demyelinating) |

A General Approach for the Hospitalist

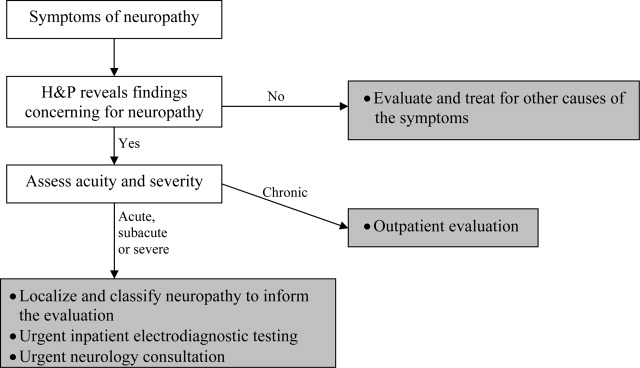

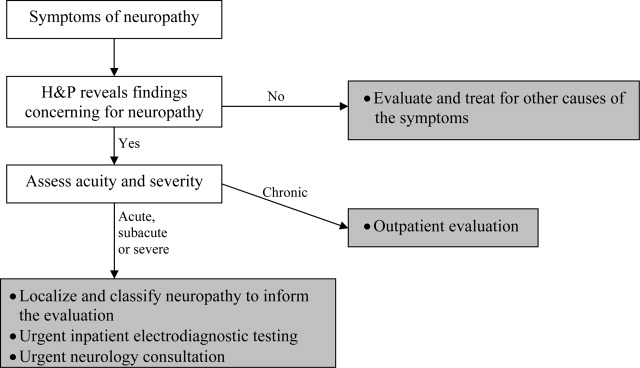

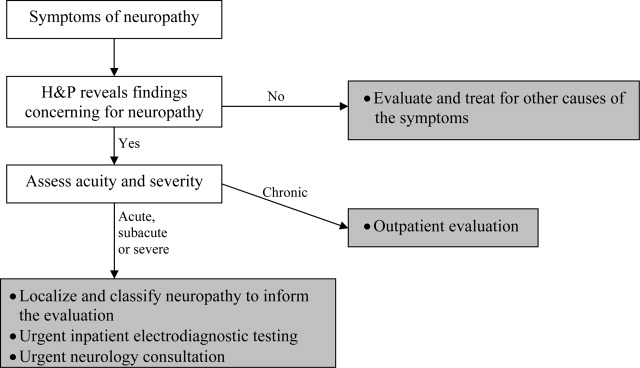

Pattern recognition and employing the essentials outlined above are key tools in the hospitalist's evaluation of peripheral neuropathy. Pattern recognition relies on a familiarity with the more common acute and severe neuropathies. For circumstances in which the diagnosis is not immediately recognizable, a systematic approach expedites evaluation. Figure 1 presents an algorithm for evaluating peripheral neuropathies in the acutely ill patient.

Pattern Recognition

In general, most acute or subacute and rapidly progressive neuropathies merit urgent neurology consultation. Patterns to be aware of in the acutely ill patient include Guillan‐Barr syndrome, vasculitis, ischemia, toxins, medication exposures, paraneoplastic syndromes, acute intermittent porphyria, diphtheria, and critical illness neuropathy. Any neuropathy presenting with associated respiratory symptoms or signs, such as shortness of breath, rapid shallow breathing, or hypoxia or hypercarbia, should also trigger urgent neurology consultation. As timely diagnosis of concerning entities relies heavily on pattern recognition, the typical presentation of more common etiologies and clues to their diagnosis are reviewed in Table 2.

| Etiology | Typical Presentation | Onset | Distribution | Electrodiagnostic Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Traumatic neuropathy | Weakness and numbness in a limb following injury | Sudden | Asymmetric | Axonal |

| Guillan‐Barr syndrome | Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy is most common but several variants exist; often follows URI or GI illness by 1‐3 weeks | Days to weeks | Ascending, symmetric | Usually demyelinating, largely motor |

| Diphtheria | Tonsillopharyngeal pseudomembrane | Days to weeks | Bulbar, descending, symmetric | Mostly demyelinating |

| Vasculitis | Waxing and waning, painful | Days to weeks | Asymmetric | Axonal |

| Acute intermittent porphyria | Can be associated with seizures/encephalopathy, abdominal pain | Days to weeks | Ascending, symmetric | Axonal, largely motor |

| Ischemic neuropathy | May follow vascular procedure by days to months; can be associated with poor peripheral pulses | Days to weeks | Asymmetric | Axonal |

| Toxins/drugs | Temporal association with offending agent: heavy metals: arsenic, lead, thallium; biologic toxins: ciguatera and shellfish poisoning. Medications: chemotherapies (ie, vincristine), colchicine, statins, nitrofurantoin, chloroquine | Days to months | Symmetric | Axonal |

| Critical illness neuropathy | Quadriparesis in the setting of sepsis/corticosteroids/neuromuscular blockade | Weeks | Symmetric | Axonal, largely motor |

| Paraneoplastic | Sensory ataxia most common; symptoms may precede cancer diagnosis; frequently associated tumors: small cell carcinoma of the lung; breast, ovarian, stomach cancers | Weeks | Symmetric | Axonal, largely sensory |

| Proximal diabetic neuropathy | Also known as diabetic lumbosacral plexopathy or Bruns‐Garland; leg pain followed by weakness/wasting | Weeks to months | Asymmetric | Axonal, largely motor |

For example, neuropathy from acute intermittent porphyria classically presents with pain in the back and limbs and progressive limb weakness (often more pronounced in the upper extremities). Respiratory failure may follow. A key to this history is that symptoms frequently follow within days of the colicky abdominal pain and encephalopathy of an attack. Additionally, attacks typically follow a precipitating event or drug exposure. These patients do not have the skin changes seen in other forms of porphyria. Treatment of this condition requires recognition and removal of any offending drug, correction of associated metabolic abnormalities, and the administration of hematin.12

Another, though rare, diagnosis that relies on pattern recognition is Bruns‐Garland syndrome (also known as proximal diabetic neuropathy). This condition is usually self‐limited, yet patients can be referred for unnecessary spinal surgery due to the severity of its symptoms. The clinical triad of severe thigh pain, absent knee jerk, and weakness in the lumbar vertebrae L3‐L4 distribution in a patient with diabetes should raise concern for this syndrome. The contralateral lower extremity can become involved in the following weeks. This syndrome is typified by a combination of injuries to the nerve root, the lumbar plexus, and the peripheral nerve. Electrodiagnostic testing confirms the syndrome, thus avoiding an unwarranted surgery.13

A Systematic Evaluation

When the etiology is not immediately evident, the essential questions identified in the review above are useful, and can be simplified for the hospitalist. First, understand the onset and timing of symptoms. Second, localize the symptoms to and within the peripheral nervous system (including classifying the distribution of nerve involvement). For acute, rapidly progressing or multifocal neuropathies urgent inpatient electrodiagnostic testing and neurology consultation should be obtained. Further testing, including laboratory testing, should be directed by these first steps.

Step 1

Delineating onset, timing and progression is of tremendous utility in establishing the diagnosis. Abrupt onset is typical of trauma, compression, thermal injury, and ischemia (due to vasculitis or other circulatory compromise). Guillan‐Barr syndrome, porphyria, critical illness neuropathy, and diphtheria can also present acutely with profound weakness. Neuropathies developing suddenly or over days to weeks merit urgent inpatient evaluation. Metabolic, paraneoplastic, and toxic causes tend to present with progressive symptoms over weeks to months. Chronic, insidious onset is most characteristic of hereditary neuropathies and some metabolic diseases such as diabetes mellitus. Evaluation of chronic neuropathies can be deferred to the outpatient setting.

Nonneuropathy causes of acute generalized weakness to consider in the differential diagnosis include: 1) muscle disorders such as periodic paralyses, metabolic defects, and myopathies (including acute viral and Lyme disease); 2) disorders of the neuromuscular junction such as myasthenia gravis, Eaton‐Lambert syndrome, organophosphate poisoning, and botulism; 3) central nervous system disorders such as brainstem ischemia, global ischemia, or multiple sclerosis; and 4) electrolyte disturbances such as hyperkalemia or hypercalcemia.14

Step 2

It is important to localize symptoms to the peripheral nervous system. Cortical lesions are unlikely to cause focal or positive sensory symptoms (ie, pain), and more frequently involve the face or upper and lower unilateral limb (ie, in the case of a stroke). Hyperreflexia can accompany cortical lesions. Conversely, peripheral nerve lesions often localize to a discrete region of a single limb or involve the contralateral limb in a symmetric fashion (ie, a stocking‐glove distribution or the ascending symmetric pattern seen in Guillan‐Barr syndrome).

With a thorough history and neurological examination the clinician can localize and classify the neuropathic lesion. Noting a motor or sensory predominance can narrow the diagnosis; for example, motor predominance is seen in Guillan‐Barr syndrome, critical illness neuropathy, and acute intermittent porphyria. Associated symptoms and signs discovered in a thorough review and physical examination of all systems can indicate the specific diagnosis. For example, a careful skin examination may find signs of vasculitis or Mees' lines (transverse white lines across the nails that can indicate heavy metal poisoning).12 Helpful tips for this evaluation are included in Table 3.

| History | Examination |

|---|---|

| |

| Ask the patient to outline the region involved | General findings |

| Dermatome radiculopathy | Screening for malignancy |

| Stocking‐glove polyneuropathy | Evaluate for vascular sufficiency |

| Single peripheral nerve mononeuropathy | Pes cavus suggests inherited disease |

| Asymmetry vasculitic neuropathy or other mononeuropathy multiplex | Skin exam for signs of vasculitis, Mees' lines |

| Associated symptoms | Neurologic findings: For each of the following, noting the distribution of abnormality will help classify the neuropathic lesion |

| Constitutional neoplasm | Decreased sensation (often the earliest sign) |

| Recent respiratory or GI illness GBS | Weakness without atrophy indicates recent axonal neuropathy or isolated demyelinating disease |

| Respiratory difficulties GBS | Marked atrophy indicates severe axonal damage |

| Autonomic symptoms GBS, porphyria | Decreased reflexes often present (except when only small sensory fibers are involved) |

| Colicky abdominal pain, encephalopathy | |

| Porphyria | |

The hospitalist should be able to classify the distribution as a mononeuropathy (involving a single nerve), a polyneuropathy (symmetric involvement of multiple nerves), or a mononeuropathy multiplex (asymmetric involvement of multiple nerves). Multifocal and proximal symmetric neuropathies commonly merit urgent evaluation.

The most devastating polyneuropathy is Guillan‐Barr syndrome, which can be fatal but is often reversible with early plasmapheresis. Vasculitis is another potentially treatable diagnosis that is critical to establish early; it most often presents as a mononeuropathy multiplex. Ischemic and traumatic mononeuropathies may be overshadowed by other illnesses and injuries, but finding these early can result in dramatically improved patient outcomes.

Step 3

Inpatient electrodiagnostic testing and neurology consultation should be ordered for any neuropathy with rapid onset, progression or severe symptoms or any neuropathy following one of the patterns described above. Electrodiagnostic testing characterizes the pathologic cause of the neuropathy as axonal, demyelinating, or mixed. It also assesses severity, chronicity, location, and symmetry of the neuropathy.15 It is imperative to have localized the neuropathy by history and examination prior to electrodiagnostic evaluation to ensure that the involved nerves are tested.

Step 4

Focused, further testing may be ordered more efficiently subsequent to the above data collection. Directed laboratory examination should be performed when indicated rather than cast as an initial broad diagnostic net. Ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomographypositron emission tomography (CT‐PET), and nerve biopsy are diagnostic modalities available to the clinician. In general, nerve biopsy should be reserved for suspected vasculitis, sarcoidosis, lymphoma, leprosy, or amyloidosis.

In summary, symptoms and signs of multifocal or proximal nerve involvement, acute onset, or rapid progression demand immediate diagnostic attention. Pattern recognition and a systematic approach expedite the diagnostic process, focusing necessary testing and decreasing overall cost. Focused steps in a systematic approach include: (1) delineating timing and onset of symptoms; (2) localizing and classifying the neuropathy; (3) obtaining electrodiagnostic testing and neurology consultation; and (4) further testing as directed by the preceding steps. Early diagnosis of acute peripheral neuropathies can lead to life‐saving or limb‐saving therapy.

- .An approach to the evaluation of peripheral neuropathies.Semin Neurol.2005;25:153–159.

- .Peripheral neuropathy.BMJ.2002;324:466–469.

- .Pinpointing peripheral neuropathies.Practitioner.2007;251:67–68,71–74,6–7 passim.

- .The evaluation of peripheral neuropathy. Part I: Clinical and laboratory evidence.Rev Neurol Dis.2004;1:133–140.

- ,.Evaluating the patient with peripheral nervous system complaints.J Am Osteopath Assoc.2005;105:71–83.

- ,,.An easy approach to evaluating peripheral neuropathy.J Fam Pract.2006;55:853–861.

- ,.Peripheral neuropathy.Lancet.2004;363:2151–2161.

- .Evaluating patients with suspected peripheral neuropathy: do the right thing, not everything.Muscle Nerve.2002;26:288–290.

- ,.A rational diagnostic approach to peripheral neuropathy.J Clin Neuromuscul Dis.2003;4:190–198.

- .Peripheral nerve disorders.Prim Care.2004;31:67–83.

- ,.Toward an efficient method to evaluate peripheral neuropathies.J Clin Neuromuscul Dis.2002;3:172–182.

- .Peripheral neuropathies in clinical practice.Med Clin North Am.2003;87:697–724.

- .The evaluation of peripheral neuropathy. Part II: Identifying common clinical syndromes.Rev Neurol Dis.2004;1:190–201.

- .Acute generalized weakness due to thyrotoxic periodic paralysis.CMAJ.2005;172:471–472.

- ,.Electrodiagnostic testing of nerves and muscles: when, why, and how to order.Cleve Clin J Med.2005;72:37–48.

Early diagnosis of peripheral neuropathies can lead to life‐saving or limb‐saving intervention. While infrequently a cause for concern in the hospital setting, peripheral neuropathies are commonoccurring in up to 10% of the general population.1 The hospitalist needs to expeditiously identify acute and life‐threatening or limb‐threatening causes among an immense set of differentials. Fortunately, with an informed and careful approach, most neuropathies in need of urgent intervention can be readily identified. A thorough history and examination, with the addition of electrodiagnostic testing, comprise the mainstays of this process. Inpatient neurology consultation should be sought for any rapidly progressing or acute onset neuropathy. The aim of this review is to equip the general hospitalist with a solid framework for efficiently evaluating peripheral neuropathies in urgent cases.

Literature Review

Search Strategy

A PubMed search was conducted using the title word peripheral, the medical subject heading major topic peripheral nervous system diseases/diagnosis, and algorithm or diagnosis, differential or diagnostic techniques, neurological or neurologic examination or evaluation or evaluating. The search was limited to English language review articles published between January 2002 and November 2007. Articles were included in this review if they provided an overview of an approach to the diagnosis of peripheral neuropathies. References listed in these articles were cross‐checked and additional articles meeting these criteria were included. Articles specific to subtypes of neuropathies or diagnostic tools were excluded.

Search Results

No single guideline or algorithm has been widely endorsed for the approach to diagnosing peripheral neuropathies. Several are suggested in the literature, but none are directed at the hospitalist. In general, acute and multifocal neuropathies are characterized as neurologic emergencies requiring immediate evaluation.2, 3

Several articles underscore the importance of pattern recognition in diagnosing peripheral neuropathies.2, 4, 5 Many articles present essential questions in evaluating peripheral neuropathy; some suggest an ordered approach.13, 511 The nature of these questions and recommended order of inquiry varies among authors (Table 1). Three essentials common to all articles include: 1) noting the onset of symptoms; 2) determining the distribution of nerve involvement; and 3) identifying the pathology as axonal, demyelinating, or mixed. All articles underscore the importance of the physical examination in determining and confirming distribution and nerve type. A thorough examination evaluating for systemic signs of etiologic possibilities is strongly recommended. Electrodiagnostic testing provides confirmation of the distribution of nerve involvement and further characterizes a neuropathy as demyelinating, axonal, or mixed.

| Article (Publication Year) | Essentials of Recommended Approach |

|---|---|

| Lunn3 (2007) | Details 6 essential questions in the history, highlighting: 1. Temporal evolution; 2. Autonomic involvement; 3. Nerve involvement (sensory/motor); 4. Cranial nerve involvement; 5. Family history; and 6. Coexistent disease |

| Examination should confirm findings expected from history | |

| Acute and multifocal neuropathies merit urgent evaluation | |

| Electrodiagnostic testing and neurology consultation should ensue if no diagnosis identified from above | |

| Burns et al.6 (2006) | Focuses on evaluation of polyneuropathy |

| Poses 4 questions: 1. Nerve involvement (sensory/motor); 2. Distribution; 3. Onset; 4. Associated factors (family history, exposures, associated systemic symptoms) | |

| Recommends electrodiagnostic testing | |

| Laboratory testing as indicated | |

| Scott and Kothari5 (2005) | Highlights importance of pattern recognition in the history and on examination |

| Ordered approach: 1. Localize site of neuropathic lesion, 2. Perform electrodiagnostic testing to determine pathology | |

| Bromberg1 (2005) | Proposes 7 layers to consider in investigation: 1. Localizing to peripheral nervous system; 2. Distribution; 3. Onset; 4. Nerve involvement (sensory/motor); 5. Pathology (axonal/demyelinating); 6. Other associated features; and 7. Epidemiologic features |

| Kelly4 (2004) | Highlights pattern recognition and features distribution, onset, and pathology in developing the differential diagnosis |

| Younger10 (2004) | Several key elements, including: timing, nerve involvement (sensory/motor/autonomic), distribution, and pathology (axonal/demyelinating) |

| England and Asbury7 (2004) | Details to determine: 1. Distribution; 2. Pathology (axonal/demyelinating); and 3. Timing |

| Smith and Bromberg9 (2003) | Suggest an algorithm: 1. Confirm the localization (history, examination and electrodiagnostic testing); 2. Identify atypical patterns; and 3. Recognize prototypic neuropathy and perform focused laboratory testing |

| Bromberg and Smith11 (2002) | 4 basic steps: 1. Nerve involvement (sensory/motor); 2. Distribution; 3. Timing; and 4. Pathology (axonal/demyelinating) |

| Hughes2 (2002) | Pattern recognition |

| Suggests staged investigation: 1. Basic laboratory tests; 2. Electrodiagnostic testing and further laboratory tests; and 3. Additional laboratory tests, imaging, and specialized testing | |

| Pourmand8 (2002) | Offers 7 key questions/steps highlighting: 1. Onset; 2. Course; 3. Distribution; 4. Nerve involvement (sensory/motor); 5. Nerve fiber type (large/small); 6. Autonomic involvement; and 7. Pathology (axonal/demyelinating) |

A General Approach for the Hospitalist

Pattern recognition and employing the essentials outlined above are key tools in the hospitalist's evaluation of peripheral neuropathy. Pattern recognition relies on a familiarity with the more common acute and severe neuropathies. For circumstances in which the diagnosis is not immediately recognizable, a systematic approach expedites evaluation. Figure 1 presents an algorithm for evaluating peripheral neuropathies in the acutely ill patient.

Pattern Recognition

In general, most acute or subacute and rapidly progressive neuropathies merit urgent neurology consultation. Patterns to be aware of in the acutely ill patient include Guillan‐Barr syndrome, vasculitis, ischemia, toxins, medication exposures, paraneoplastic syndromes, acute intermittent porphyria, diphtheria, and critical illness neuropathy. Any neuropathy presenting with associated respiratory symptoms or signs, such as shortness of breath, rapid shallow breathing, or hypoxia or hypercarbia, should also trigger urgent neurology consultation. As timely diagnosis of concerning entities relies heavily on pattern recognition, the typical presentation of more common etiologies and clues to their diagnosis are reviewed in Table 2.

| Etiology | Typical Presentation | Onset | Distribution | Electrodiagnostic Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Traumatic neuropathy | Weakness and numbness in a limb following injury | Sudden | Asymmetric | Axonal |

| Guillan‐Barr syndrome | Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy is most common but several variants exist; often follows URI or GI illness by 1‐3 weeks | Days to weeks | Ascending, symmetric | Usually demyelinating, largely motor |

| Diphtheria | Tonsillopharyngeal pseudomembrane | Days to weeks | Bulbar, descending, symmetric | Mostly demyelinating |

| Vasculitis | Waxing and waning, painful | Days to weeks | Asymmetric | Axonal |

| Acute intermittent porphyria | Can be associated with seizures/encephalopathy, abdominal pain | Days to weeks | Ascending, symmetric | Axonal, largely motor |

| Ischemic neuropathy | May follow vascular procedure by days to months; can be associated with poor peripheral pulses | Days to weeks | Asymmetric | Axonal |

| Toxins/drugs | Temporal association with offending agent: heavy metals: arsenic, lead, thallium; biologic toxins: ciguatera and shellfish poisoning. Medications: chemotherapies (ie, vincristine), colchicine, statins, nitrofurantoin, chloroquine | Days to months | Symmetric | Axonal |

| Critical illness neuropathy | Quadriparesis in the setting of sepsis/corticosteroids/neuromuscular blockade | Weeks | Symmetric | Axonal, largely motor |

| Paraneoplastic | Sensory ataxia most common; symptoms may precede cancer diagnosis; frequently associated tumors: small cell carcinoma of the lung; breast, ovarian, stomach cancers | Weeks | Symmetric | Axonal, largely sensory |

| Proximal diabetic neuropathy | Also known as diabetic lumbosacral plexopathy or Bruns‐Garland; leg pain followed by weakness/wasting | Weeks to months | Asymmetric | Axonal, largely motor |

For example, neuropathy from acute intermittent porphyria classically presents with pain in the back and limbs and progressive limb weakness (often more pronounced in the upper extremities). Respiratory failure may follow. A key to this history is that symptoms frequently follow within days of the colicky abdominal pain and encephalopathy of an attack. Additionally, attacks typically follow a precipitating event or drug exposure. These patients do not have the skin changes seen in other forms of porphyria. Treatment of this condition requires recognition and removal of any offending drug, correction of associated metabolic abnormalities, and the administration of hematin.12

Another, though rare, diagnosis that relies on pattern recognition is Bruns‐Garland syndrome (also known as proximal diabetic neuropathy). This condition is usually self‐limited, yet patients can be referred for unnecessary spinal surgery due to the severity of its symptoms. The clinical triad of severe thigh pain, absent knee jerk, and weakness in the lumbar vertebrae L3‐L4 distribution in a patient with diabetes should raise concern for this syndrome. The contralateral lower extremity can become involved in the following weeks. This syndrome is typified by a combination of injuries to the nerve root, the lumbar plexus, and the peripheral nerve. Electrodiagnostic testing confirms the syndrome, thus avoiding an unwarranted surgery.13

A Systematic Evaluation

When the etiology is not immediately evident, the essential questions identified in the review above are useful, and can be simplified for the hospitalist. First, understand the onset and timing of symptoms. Second, localize the symptoms to and within the peripheral nervous system (including classifying the distribution of nerve involvement). For acute, rapidly progressing or multifocal neuropathies urgent inpatient electrodiagnostic testing and neurology consultation should be obtained. Further testing, including laboratory testing, should be directed by these first steps.

Step 1

Delineating onset, timing and progression is of tremendous utility in establishing the diagnosis. Abrupt onset is typical of trauma, compression, thermal injury, and ischemia (due to vasculitis or other circulatory compromise). Guillan‐Barr syndrome, porphyria, critical illness neuropathy, and diphtheria can also present acutely with profound weakness. Neuropathies developing suddenly or over days to weeks merit urgent inpatient evaluation. Metabolic, paraneoplastic, and toxic causes tend to present with progressive symptoms over weeks to months. Chronic, insidious onset is most characteristic of hereditary neuropathies and some metabolic diseases such as diabetes mellitus. Evaluation of chronic neuropathies can be deferred to the outpatient setting.

Nonneuropathy causes of acute generalized weakness to consider in the differential diagnosis include: 1) muscle disorders such as periodic paralyses, metabolic defects, and myopathies (including acute viral and Lyme disease); 2) disorders of the neuromuscular junction such as myasthenia gravis, Eaton‐Lambert syndrome, organophosphate poisoning, and botulism; 3) central nervous system disorders such as brainstem ischemia, global ischemia, or multiple sclerosis; and 4) electrolyte disturbances such as hyperkalemia or hypercalcemia.14

Step 2

It is important to localize symptoms to the peripheral nervous system. Cortical lesions are unlikely to cause focal or positive sensory symptoms (ie, pain), and more frequently involve the face or upper and lower unilateral limb (ie, in the case of a stroke). Hyperreflexia can accompany cortical lesions. Conversely, peripheral nerve lesions often localize to a discrete region of a single limb or involve the contralateral limb in a symmetric fashion (ie, a stocking‐glove distribution or the ascending symmetric pattern seen in Guillan‐Barr syndrome).

With a thorough history and neurological examination the clinician can localize and classify the neuropathic lesion. Noting a motor or sensory predominance can narrow the diagnosis; for example, motor predominance is seen in Guillan‐Barr syndrome, critical illness neuropathy, and acute intermittent porphyria. Associated symptoms and signs discovered in a thorough review and physical examination of all systems can indicate the specific diagnosis. For example, a careful skin examination may find signs of vasculitis or Mees' lines (transverse white lines across the nails that can indicate heavy metal poisoning).12 Helpful tips for this evaluation are included in Table 3.

| History | Examination |

|---|---|

| |

| Ask the patient to outline the region involved | General findings |

| Dermatome radiculopathy | Screening for malignancy |

| Stocking‐glove polyneuropathy | Evaluate for vascular sufficiency |

| Single peripheral nerve mononeuropathy | Pes cavus suggests inherited disease |

| Asymmetry vasculitic neuropathy or other mononeuropathy multiplex | Skin exam for signs of vasculitis, Mees' lines |

| Associated symptoms | Neurologic findings: For each of the following, noting the distribution of abnormality will help classify the neuropathic lesion |

| Constitutional neoplasm | Decreased sensation (often the earliest sign) |

| Recent respiratory or GI illness GBS | Weakness without atrophy indicates recent axonal neuropathy or isolated demyelinating disease |

| Respiratory difficulties GBS | Marked atrophy indicates severe axonal damage |

| Autonomic symptoms GBS, porphyria | Decreased reflexes often present (except when only small sensory fibers are involved) |

| Colicky abdominal pain, encephalopathy | |

| Porphyria | |

The hospitalist should be able to classify the distribution as a mononeuropathy (involving a single nerve), a polyneuropathy (symmetric involvement of multiple nerves), or a mononeuropathy multiplex (asymmetric involvement of multiple nerves). Multifocal and proximal symmetric neuropathies commonly merit urgent evaluation.

The most devastating polyneuropathy is Guillan‐Barr syndrome, which can be fatal but is often reversible with early plasmapheresis. Vasculitis is another potentially treatable diagnosis that is critical to establish early; it most often presents as a mononeuropathy multiplex. Ischemic and traumatic mononeuropathies may be overshadowed by other illnesses and injuries, but finding these early can result in dramatically improved patient outcomes.

Step 3

Inpatient electrodiagnostic testing and neurology consultation should be ordered for any neuropathy with rapid onset, progression or severe symptoms or any neuropathy following one of the patterns described above. Electrodiagnostic testing characterizes the pathologic cause of the neuropathy as axonal, demyelinating, or mixed. It also assesses severity, chronicity, location, and symmetry of the neuropathy.15 It is imperative to have localized the neuropathy by history and examination prior to electrodiagnostic evaluation to ensure that the involved nerves are tested.

Step 4

Focused, further testing may be ordered more efficiently subsequent to the above data collection. Directed laboratory examination should be performed when indicated rather than cast as an initial broad diagnostic net. Ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomographypositron emission tomography (CT‐PET), and nerve biopsy are diagnostic modalities available to the clinician. In general, nerve biopsy should be reserved for suspected vasculitis, sarcoidosis, lymphoma, leprosy, or amyloidosis.

In summary, symptoms and signs of multifocal or proximal nerve involvement, acute onset, or rapid progression demand immediate diagnostic attention. Pattern recognition and a systematic approach expedite the diagnostic process, focusing necessary testing and decreasing overall cost. Focused steps in a systematic approach include: (1) delineating timing and onset of symptoms; (2) localizing and classifying the neuropathy; (3) obtaining electrodiagnostic testing and neurology consultation; and (4) further testing as directed by the preceding steps. Early diagnosis of acute peripheral neuropathies can lead to life‐saving or limb‐saving therapy.

Early diagnosis of peripheral neuropathies can lead to life‐saving or limb‐saving intervention. While infrequently a cause for concern in the hospital setting, peripheral neuropathies are commonoccurring in up to 10% of the general population.1 The hospitalist needs to expeditiously identify acute and life‐threatening or limb‐threatening causes among an immense set of differentials. Fortunately, with an informed and careful approach, most neuropathies in need of urgent intervention can be readily identified. A thorough history and examination, with the addition of electrodiagnostic testing, comprise the mainstays of this process. Inpatient neurology consultation should be sought for any rapidly progressing or acute onset neuropathy. The aim of this review is to equip the general hospitalist with a solid framework for efficiently evaluating peripheral neuropathies in urgent cases.

Literature Review

Search Strategy

A PubMed search was conducted using the title word peripheral, the medical subject heading major topic peripheral nervous system diseases/diagnosis, and algorithm or diagnosis, differential or diagnostic techniques, neurological or neurologic examination or evaluation or evaluating. The search was limited to English language review articles published between January 2002 and November 2007. Articles were included in this review if they provided an overview of an approach to the diagnosis of peripheral neuropathies. References listed in these articles were cross‐checked and additional articles meeting these criteria were included. Articles specific to subtypes of neuropathies or diagnostic tools were excluded.

Search Results

No single guideline or algorithm has been widely endorsed for the approach to diagnosing peripheral neuropathies. Several are suggested in the literature, but none are directed at the hospitalist. In general, acute and multifocal neuropathies are characterized as neurologic emergencies requiring immediate evaluation.2, 3

Several articles underscore the importance of pattern recognition in diagnosing peripheral neuropathies.2, 4, 5 Many articles present essential questions in evaluating peripheral neuropathy; some suggest an ordered approach.13, 511 The nature of these questions and recommended order of inquiry varies among authors (Table 1). Three essentials common to all articles include: 1) noting the onset of symptoms; 2) determining the distribution of nerve involvement; and 3) identifying the pathology as axonal, demyelinating, or mixed. All articles underscore the importance of the physical examination in determining and confirming distribution and nerve type. A thorough examination evaluating for systemic signs of etiologic possibilities is strongly recommended. Electrodiagnostic testing provides confirmation of the distribution of nerve involvement and further characterizes a neuropathy as demyelinating, axonal, or mixed.

| Article (Publication Year) | Essentials of Recommended Approach |

|---|---|

| Lunn3 (2007) | Details 6 essential questions in the history, highlighting: 1. Temporal evolution; 2. Autonomic involvement; 3. Nerve involvement (sensory/motor); 4. Cranial nerve involvement; 5. Family history; and 6. Coexistent disease |

| Examination should confirm findings expected from history | |

| Acute and multifocal neuropathies merit urgent evaluation | |

| Electrodiagnostic testing and neurology consultation should ensue if no diagnosis identified from above | |

| Burns et al.6 (2006) | Focuses on evaluation of polyneuropathy |

| Poses 4 questions: 1. Nerve involvement (sensory/motor); 2. Distribution; 3. Onset; 4. Associated factors (family history, exposures, associated systemic symptoms) | |

| Recommends electrodiagnostic testing | |

| Laboratory testing as indicated | |

| Scott and Kothari5 (2005) | Highlights importance of pattern recognition in the history and on examination |

| Ordered approach: 1. Localize site of neuropathic lesion, 2. Perform electrodiagnostic testing to determine pathology | |

| Bromberg1 (2005) | Proposes 7 layers to consider in investigation: 1. Localizing to peripheral nervous system; 2. Distribution; 3. Onset; 4. Nerve involvement (sensory/motor); 5. Pathology (axonal/demyelinating); 6. Other associated features; and 7. Epidemiologic features |

| Kelly4 (2004) | Highlights pattern recognition and features distribution, onset, and pathology in developing the differential diagnosis |

| Younger10 (2004) | Several key elements, including: timing, nerve involvement (sensory/motor/autonomic), distribution, and pathology (axonal/demyelinating) |

| England and Asbury7 (2004) | Details to determine: 1. Distribution; 2. Pathology (axonal/demyelinating); and 3. Timing |

| Smith and Bromberg9 (2003) | Suggest an algorithm: 1. Confirm the localization (history, examination and electrodiagnostic testing); 2. Identify atypical patterns; and 3. Recognize prototypic neuropathy and perform focused laboratory testing |

| Bromberg and Smith11 (2002) | 4 basic steps: 1. Nerve involvement (sensory/motor); 2. Distribution; 3. Timing; and 4. Pathology (axonal/demyelinating) |

| Hughes2 (2002) | Pattern recognition |

| Suggests staged investigation: 1. Basic laboratory tests; 2. Electrodiagnostic testing and further laboratory tests; and 3. Additional laboratory tests, imaging, and specialized testing | |

| Pourmand8 (2002) | Offers 7 key questions/steps highlighting: 1. Onset; 2. Course; 3. Distribution; 4. Nerve involvement (sensory/motor); 5. Nerve fiber type (large/small); 6. Autonomic involvement; and 7. Pathology (axonal/demyelinating) |

A General Approach for the Hospitalist

Pattern recognition and employing the essentials outlined above are key tools in the hospitalist's evaluation of peripheral neuropathy. Pattern recognition relies on a familiarity with the more common acute and severe neuropathies. For circumstances in which the diagnosis is not immediately recognizable, a systematic approach expedites evaluation. Figure 1 presents an algorithm for evaluating peripheral neuropathies in the acutely ill patient.

Pattern Recognition

In general, most acute or subacute and rapidly progressive neuropathies merit urgent neurology consultation. Patterns to be aware of in the acutely ill patient include Guillan‐Barr syndrome, vasculitis, ischemia, toxins, medication exposures, paraneoplastic syndromes, acute intermittent porphyria, diphtheria, and critical illness neuropathy. Any neuropathy presenting with associated respiratory symptoms or signs, such as shortness of breath, rapid shallow breathing, or hypoxia or hypercarbia, should also trigger urgent neurology consultation. As timely diagnosis of concerning entities relies heavily on pattern recognition, the typical presentation of more common etiologies and clues to their diagnosis are reviewed in Table 2.

| Etiology | Typical Presentation | Onset | Distribution | Electrodiagnostic Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Traumatic neuropathy | Weakness and numbness in a limb following injury | Sudden | Asymmetric | Axonal |

| Guillan‐Barr syndrome | Acute inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy is most common but several variants exist; often follows URI or GI illness by 1‐3 weeks | Days to weeks | Ascending, symmetric | Usually demyelinating, largely motor |

| Diphtheria | Tonsillopharyngeal pseudomembrane | Days to weeks | Bulbar, descending, symmetric | Mostly demyelinating |

| Vasculitis | Waxing and waning, painful | Days to weeks | Asymmetric | Axonal |

| Acute intermittent porphyria | Can be associated with seizures/encephalopathy, abdominal pain | Days to weeks | Ascending, symmetric | Axonal, largely motor |

| Ischemic neuropathy | May follow vascular procedure by days to months; can be associated with poor peripheral pulses | Days to weeks | Asymmetric | Axonal |

| Toxins/drugs | Temporal association with offending agent: heavy metals: arsenic, lead, thallium; biologic toxins: ciguatera and shellfish poisoning. Medications: chemotherapies (ie, vincristine), colchicine, statins, nitrofurantoin, chloroquine | Days to months | Symmetric | Axonal |

| Critical illness neuropathy | Quadriparesis in the setting of sepsis/corticosteroids/neuromuscular blockade | Weeks | Symmetric | Axonal, largely motor |

| Paraneoplastic | Sensory ataxia most common; symptoms may precede cancer diagnosis; frequently associated tumors: small cell carcinoma of the lung; breast, ovarian, stomach cancers | Weeks | Symmetric | Axonal, largely sensory |

| Proximal diabetic neuropathy | Also known as diabetic lumbosacral plexopathy or Bruns‐Garland; leg pain followed by weakness/wasting | Weeks to months | Asymmetric | Axonal, largely motor |

For example, neuropathy from acute intermittent porphyria classically presents with pain in the back and limbs and progressive limb weakness (often more pronounced in the upper extremities). Respiratory failure may follow. A key to this history is that symptoms frequently follow within days of the colicky abdominal pain and encephalopathy of an attack. Additionally, attacks typically follow a precipitating event or drug exposure. These patients do not have the skin changes seen in other forms of porphyria. Treatment of this condition requires recognition and removal of any offending drug, correction of associated metabolic abnormalities, and the administration of hematin.12

Another, though rare, diagnosis that relies on pattern recognition is Bruns‐Garland syndrome (also known as proximal diabetic neuropathy). This condition is usually self‐limited, yet patients can be referred for unnecessary spinal surgery due to the severity of its symptoms. The clinical triad of severe thigh pain, absent knee jerk, and weakness in the lumbar vertebrae L3‐L4 distribution in a patient with diabetes should raise concern for this syndrome. The contralateral lower extremity can become involved in the following weeks. This syndrome is typified by a combination of injuries to the nerve root, the lumbar plexus, and the peripheral nerve. Electrodiagnostic testing confirms the syndrome, thus avoiding an unwarranted surgery.13

A Systematic Evaluation

When the etiology is not immediately evident, the essential questions identified in the review above are useful, and can be simplified for the hospitalist. First, understand the onset and timing of symptoms. Second, localize the symptoms to and within the peripheral nervous system (including classifying the distribution of nerve involvement). For acute, rapidly progressing or multifocal neuropathies urgent inpatient electrodiagnostic testing and neurology consultation should be obtained. Further testing, including laboratory testing, should be directed by these first steps.

Step 1

Delineating onset, timing and progression is of tremendous utility in establishing the diagnosis. Abrupt onset is typical of trauma, compression, thermal injury, and ischemia (due to vasculitis or other circulatory compromise). Guillan‐Barr syndrome, porphyria, critical illness neuropathy, and diphtheria can also present acutely with profound weakness. Neuropathies developing suddenly or over days to weeks merit urgent inpatient evaluation. Metabolic, paraneoplastic, and toxic causes tend to present with progressive symptoms over weeks to months. Chronic, insidious onset is most characteristic of hereditary neuropathies and some metabolic diseases such as diabetes mellitus. Evaluation of chronic neuropathies can be deferred to the outpatient setting.

Nonneuropathy causes of acute generalized weakness to consider in the differential diagnosis include: 1) muscle disorders such as periodic paralyses, metabolic defects, and myopathies (including acute viral and Lyme disease); 2) disorders of the neuromuscular junction such as myasthenia gravis, Eaton‐Lambert syndrome, organophosphate poisoning, and botulism; 3) central nervous system disorders such as brainstem ischemia, global ischemia, or multiple sclerosis; and 4) electrolyte disturbances such as hyperkalemia or hypercalcemia.14

Step 2

It is important to localize symptoms to the peripheral nervous system. Cortical lesions are unlikely to cause focal or positive sensory symptoms (ie, pain), and more frequently involve the face or upper and lower unilateral limb (ie, in the case of a stroke). Hyperreflexia can accompany cortical lesions. Conversely, peripheral nerve lesions often localize to a discrete region of a single limb or involve the contralateral limb in a symmetric fashion (ie, a stocking‐glove distribution or the ascending symmetric pattern seen in Guillan‐Barr syndrome).

With a thorough history and neurological examination the clinician can localize and classify the neuropathic lesion. Noting a motor or sensory predominance can narrow the diagnosis; for example, motor predominance is seen in Guillan‐Barr syndrome, critical illness neuropathy, and acute intermittent porphyria. Associated symptoms and signs discovered in a thorough review and physical examination of all systems can indicate the specific diagnosis. For example, a careful skin examination may find signs of vasculitis or Mees' lines (transverse white lines across the nails that can indicate heavy metal poisoning).12 Helpful tips for this evaluation are included in Table 3.

| History | Examination |

|---|---|

| |

| Ask the patient to outline the region involved | General findings |

| Dermatome radiculopathy | Screening for malignancy |

| Stocking‐glove polyneuropathy | Evaluate for vascular sufficiency |

| Single peripheral nerve mononeuropathy | Pes cavus suggests inherited disease |

| Asymmetry vasculitic neuropathy or other mononeuropathy multiplex | Skin exam for signs of vasculitis, Mees' lines |

| Associated symptoms | Neurologic findings: For each of the following, noting the distribution of abnormality will help classify the neuropathic lesion |

| Constitutional neoplasm | Decreased sensation (often the earliest sign) |

| Recent respiratory or GI illness GBS | Weakness without atrophy indicates recent axonal neuropathy or isolated demyelinating disease |

| Respiratory difficulties GBS | Marked atrophy indicates severe axonal damage |

| Autonomic symptoms GBS, porphyria | Decreased reflexes often present (except when only small sensory fibers are involved) |

| Colicky abdominal pain, encephalopathy | |

| Porphyria | |

The hospitalist should be able to classify the distribution as a mononeuropathy (involving a single nerve), a polyneuropathy (symmetric involvement of multiple nerves), or a mononeuropathy multiplex (asymmetric involvement of multiple nerves). Multifocal and proximal symmetric neuropathies commonly merit urgent evaluation.

The most devastating polyneuropathy is Guillan‐Barr syndrome, which can be fatal but is often reversible with early plasmapheresis. Vasculitis is another potentially treatable diagnosis that is critical to establish early; it most often presents as a mononeuropathy multiplex. Ischemic and traumatic mononeuropathies may be overshadowed by other illnesses and injuries, but finding these early can result in dramatically improved patient outcomes.

Step 3

Inpatient electrodiagnostic testing and neurology consultation should be ordered for any neuropathy with rapid onset, progression or severe symptoms or any neuropathy following one of the patterns described above. Electrodiagnostic testing characterizes the pathologic cause of the neuropathy as axonal, demyelinating, or mixed. It also assesses severity, chronicity, location, and symmetry of the neuropathy.15 It is imperative to have localized the neuropathy by history and examination prior to electrodiagnostic evaluation to ensure that the involved nerves are tested.

Step 4

Focused, further testing may be ordered more efficiently subsequent to the above data collection. Directed laboratory examination should be performed when indicated rather than cast as an initial broad diagnostic net. Ultrasound, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), computed tomographypositron emission tomography (CT‐PET), and nerve biopsy are diagnostic modalities available to the clinician. In general, nerve biopsy should be reserved for suspected vasculitis, sarcoidosis, lymphoma, leprosy, or amyloidosis.

In summary, symptoms and signs of multifocal or proximal nerve involvement, acute onset, or rapid progression demand immediate diagnostic attention. Pattern recognition and a systematic approach expedite the diagnostic process, focusing necessary testing and decreasing overall cost. Focused steps in a systematic approach include: (1) delineating timing and onset of symptoms; (2) localizing and classifying the neuropathy; (3) obtaining electrodiagnostic testing and neurology consultation; and (4) further testing as directed by the preceding steps. Early diagnosis of acute peripheral neuropathies can lead to life‐saving or limb‐saving therapy.

- .An approach to the evaluation of peripheral neuropathies.Semin Neurol.2005;25:153–159.

- .Peripheral neuropathy.BMJ.2002;324:466–469.

- .Pinpointing peripheral neuropathies.Practitioner.2007;251:67–68,71–74,6–7 passim.

- .The evaluation of peripheral neuropathy. Part I: Clinical and laboratory evidence.Rev Neurol Dis.2004;1:133–140.

- ,.Evaluating the patient with peripheral nervous system complaints.J Am Osteopath Assoc.2005;105:71–83.

- ,,.An easy approach to evaluating peripheral neuropathy.J Fam Pract.2006;55:853–861.

- ,.Peripheral neuropathy.Lancet.2004;363:2151–2161.

- .Evaluating patients with suspected peripheral neuropathy: do the right thing, not everything.Muscle Nerve.2002;26:288–290.

- ,.A rational diagnostic approach to peripheral neuropathy.J Clin Neuromuscul Dis.2003;4:190–198.

- .Peripheral nerve disorders.Prim Care.2004;31:67–83.

- ,.Toward an efficient method to evaluate peripheral neuropathies.J Clin Neuromuscul Dis.2002;3:172–182.

- .Peripheral neuropathies in clinical practice.Med Clin North Am.2003;87:697–724.

- .The evaluation of peripheral neuropathy. Part II: Identifying common clinical syndromes.Rev Neurol Dis.2004;1:190–201.

- .Acute generalized weakness due to thyrotoxic periodic paralysis.CMAJ.2005;172:471–472.

- ,.Electrodiagnostic testing of nerves and muscles: when, why, and how to order.Cleve Clin J Med.2005;72:37–48.

- .An approach to the evaluation of peripheral neuropathies.Semin Neurol.2005;25:153–159.

- .Peripheral neuropathy.BMJ.2002;324:466–469.

- .Pinpointing peripheral neuropathies.Practitioner.2007;251:67–68,71–74,6–7 passim.

- .The evaluation of peripheral neuropathy. Part I: Clinical and laboratory evidence.Rev Neurol Dis.2004;1:133–140.

- ,.Evaluating the patient with peripheral nervous system complaints.J Am Osteopath Assoc.2005;105:71–83.

- ,,.An easy approach to evaluating peripheral neuropathy.J Fam Pract.2006;55:853–861.

- ,.Peripheral neuropathy.Lancet.2004;363:2151–2161.

- .Evaluating patients with suspected peripheral neuropathy: do the right thing, not everything.Muscle Nerve.2002;26:288–290.

- ,.A rational diagnostic approach to peripheral neuropathy.J Clin Neuromuscul Dis.2003;4:190–198.

- .Peripheral nerve disorders.Prim Care.2004;31:67–83.

- ,.Toward an efficient method to evaluate peripheral neuropathies.J Clin Neuromuscul Dis.2002;3:172–182.

- .Peripheral neuropathies in clinical practice.Med Clin North Am.2003;87:697–724.

- .The evaluation of peripheral neuropathy. Part II: Identifying common clinical syndromes.Rev Neurol Dis.2004;1:190–201.

- .Acute generalized weakness due to thyrotoxic periodic paralysis.CMAJ.2005;172:471–472.

- ,.Electrodiagnostic testing of nerves and muscles: when, why, and how to order.Cleve Clin J Med.2005;72:37–48.