User login

Suicide by cop: What motivates those who choose this method?

CASE Unresponsive and suicidal

Mr. Z, age 25, an unemployed immigrant from Eastern Europe, is found unresponsive at a subway station. Workup in the emergency room reveals a positive urine toxicology for benzodiazepines and a blood alcohol level of 101.6 mg/dL. When Mr. Z regains consciousness the next day, he says that he is suicidal. He recently broke up with his girlfriend and feels worthless, hopeless, and depressed. As a suicide attempt, he took quetiapine and diazepam chased with vodka.

Mr. Z reports a history of suicide attempts. He says he has been suffering from depression most of his life and has been diagnosed with bipolar I disorder and borderline personality disorder. His medication regimen consists of quetiapine, 200 mg/d, and duloxetine, 20 mg/d.

Before immigrating to the United States 5 years ago, he attempted to overdose on his mother’s prescribed diazepam and was in a coma for 2 days. Recently, he stole a bicycle with the intent of provoking the police to kill him. When caught, he deliberately disobeyed the officer’s order and advanced toward the officer in an aggressive manner. However, the officer stopped Mr. Z using a stun gun. Mr. Z reports that he still feels angry that his suicide attempt failed. He is an Orthodox Christian and says he is “very religious.”

[polldaddy:9731423]

The authors’ observations

The means of suicide differ among individuals. Some attempt suicide by themselves; others through the involuntary participation of others, such as the police. This is known as SBC. Other terms include “suicide by means of victim-precipitated homicide,”1 “hetero-suicide,”2 “suicide by proxy,”3 “copicide,”4 and “law enforcement-forced-assisted suicide.”5,6 SBC accounts for 10%7 to 36%6 of police shootings and can cause serious stress for the officers involved and creates a strain between the police and the community.8

SBC was first mentioned as “suicide by means of victim-precipitated homicide.” Wolfgang5 reported 588 cases of police officer-involved shooting in Philadelphia between January 1948 and December 31, 1952, and, concluded that 150 of these cases (26%) fit criteria for what the author termed “victim-precipitated homicide” because the victims involved were the direct precipitants of the situation leading to their death. Wolfgang stated:

Instead of a murderer performing the act of suicide by killing another person who represents the murder’s unconscious, and instead of a suicide representing the desire to kill turned on [the] self, the victim in these victim-precipitated homicide cases is considered to be a suicide prone [individual] who manifests his desire to destroy [him]self by engaging another person to perform the act.

The term “SBC” was coined in 1983 by Karl Harris, a Los Angeles County medical examiner.8 The social repercussions of this modality attracts media attention because of its negative social consequences.

Characteristics of SBC

SBC has characteristics similar to other means of suicide; it is more prevalent among men with psychiatric disorders, including major depression, bipolar disorders, schizophrenia, substance use disorders,9 poor stress response skills, recent stressors, and adverse life events,10 and history of suicide attempts.

Psychosocial characteristics include:

- mean age 31.8 years1

- male sex (98%)

- white (52%)

- approximately 40% involve some form of relationship conflict.6

In psychological autopsy studies, an estimated 70.5% of those involved in a SBC incident had ≥1 stressful life events,1 including terminal illness, loss of a job, a lawsuit, or domestic issues. However, the reason is unknown for the remaining 28% cases.2 Thirty-five percent of those involved in SBC incidents were married, 13.5% divorced, and 46.7% single.1 Seventy-seven percent had low socioeconomic status,11 with 49.3% unemployed at the time of the SBC incident.1

Pathological characteristics of SBC and other suicide means are similar. Among SBC cases, 39% had previously attempted suicide6; 56% have a psychiatric or chronic medical comorbidity. Alcohol and drug abuse were reported among 56% of individuals, and 66% had a criminal history.6 Additionally, comorbid psychiatric disorders, especially those of the impulsive and emotionally unstable types, such as borderline and antisocial personality disorder, have been found to play a major role in SBC incidents.12

Individual suicide vs SBC

Religious beliefs. The term “religiosity” is used to define an individual’s idiosyncratic religious belief or personal religious philosophy reconciling the concept of death by suicide and the afterlife. Although there are no studies that specifically reference the relationship between SBC and religiosity, religious belief and affiliation appear to be strong motivating factors. SBC victims might have an idiosyncratic view of religion related death by suicide. Whether suicide is performed while under delusional belief about God, the devil, or being possessed by demons,13 or to avoid the moral prohibition of most religious faiths in regard to suicide,6 the degree of religiosity in SBC is an important area for future research.

Mr. Z stated that his strong religious faith as an Orthodox Christian motivated the attempted SBC. He tried to provoke the officer to kill him, because as a devout Orthodox Christian, it is against his religious beliefs to kill himself. He reasoned that, because his beliefs preclude him from performing the suicidal act on his own,6,14 having an officer pull the trigger would relieve him from committing what he perceived as a sin.6

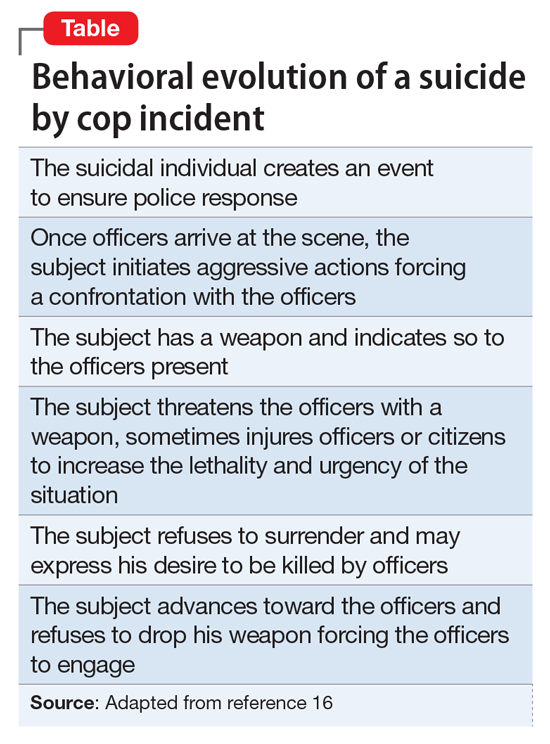

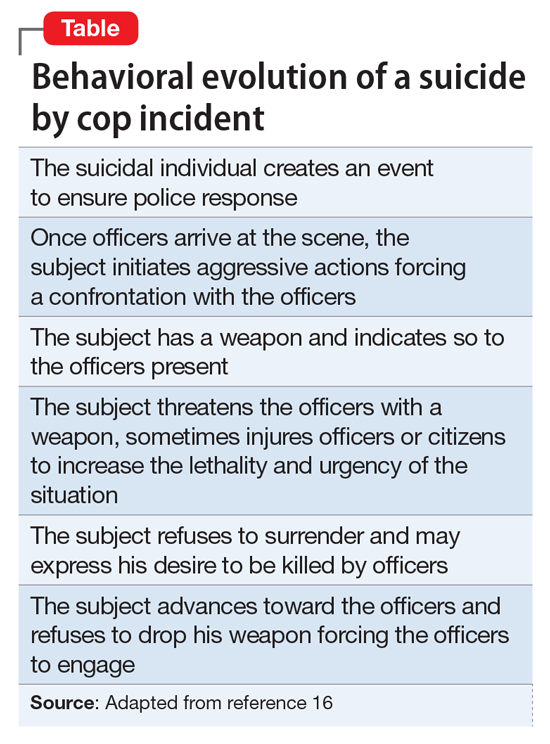

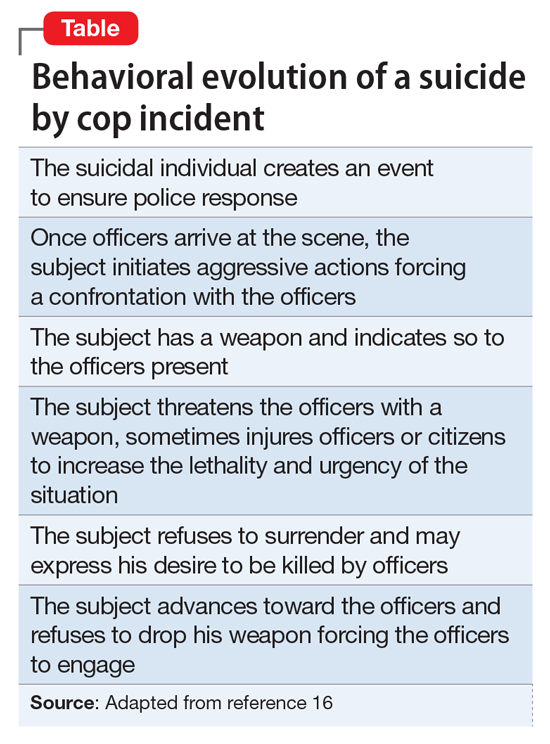

Lethal vs danger. Another difference is the level of urgency that individuals create around them when attempting SBC. Homant and Kennedy15 see this in terms of 2 ideas: lethal and danger. Lethal refers to the degree of harm posed toward the suicidal individual. Danger is the degree of harm posed by the suicidal individual toward others (ie, police officers, bystanders, hostages, family members, a spouse, etc.). SBC often is more dangerous and more lethal than other methods of suicide. SBC individuals might threaten the lives of others to provoke the police into using deadly force, such as aiming or brandishing a gun or weapon at police officers or bystanders, increasing the lethality and dangerousness of the situation. Individuals engaging in SBC might shoot or kill others to create a confrontation with the police in order to be killed in the process (Table16).

Instrumental vs expressive goals

Mohandie and Meloy6 identified 2 primary goals of those involved in SBC events: instrumental and expressive. Individuals in the instrumental category are:

- attempting to escape or avoid the consequences of criminal or shameful actions

- using the forced confrontation with police to reconcile a failed relationship

- hoping to avoid the exclusion clauses of life insurance policies

- rationalizing that while it may be morally wrong to commit suicide, being killed resolves the spiritual problem of suicide

- seeking what they believe to be a very effective and lethal means of accomplishing death.

An expressive goal is more personal and includes individuals who use the confrontation with the police to communicate:

- hopelessness, depression, and desperation

- a statement about their ultimate identification as victims

- their need to “save face” by dying or being forcibly overwhelmed rather than surrendering

- their intense power needs, rage, and revenge

- their need to draw attention to an important personal issue.

Mr. Z chose what he believed to be an efficiently lethal way of dying in accord with his religious faith, knowing that a confrontation with the police could have a fatal ending. This case represents an instrumental motivation to die by SBC that was religiously motivated.

[polldaddy:9731428]

The authors’ observations

SBC presents a specific and serious challenge for law enforcement personnel, and should be approached in a manner different than other crisis situations. Because many individuals engaging in SBC have a history of mental illness, officers with training in handling individuals with psychiatric disorders—known as Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) in many areas—should be deployed as first responders. CITs have been shown to:

- reduce arrest rates of individuals with psychiatric disorders

- increase referral rates to appropriate treatment

- decrease police injuries when responding to calls

- decrease the need for escalation with specialized tactical response teams, such as Special Weapons And Tactics.17

Identification of SBC behavior is crucial during police response. Indicators of a SBC include:

- refusal to comply with police order

- refusal to surrender

- lack of interest in getting out of a barricade or hostage situation alive.18

In approaching a SBC incident, responding officers should be non-confrontational and try to talk to the suicidal individual.8 If force is needed to resolve the crisis, non-lethal measures should be used first.8 Law enforcement and mental health professionals should suspect a SBC situation in individuals who have had prior police contact and are exhibiting behaviors outlined in the Table.16

Once suicidality is identified, it should be treated promptly. Patients who are at imminent risk to themselves or others should be hospitalized to maintain their safety. Similar to other suicide modalities, the primary risk factor for SBC is untreated or inadequately treated psychiatric illness. Therefore, the crux of managing SBC involves identifying and treating the underlying mental disorder.

Pharmacological treatment should be guided by the patient’s symptoms and psychiatric diagnosis. For suicidal behavior associated with bipolar depression and other affective disorders, lithium has evidence of reducing suicidality. Studies have shown a 5.5-fold reduction in suicide risk and a >13-fold reduction in completed suicides with lithium treatment.19 In patients with schizophrenia, clozapine has been shown to reduce suicide risk and is the only FDA-approved agent for this indication.19 Although antidepressants can effectively treat depression, there are no studies that show that 1 antidepressant is more effective than others in reducing suicidality. This might be because of the long latency period between treatment initiation and symptom relief. Ketamine, an N-methyl-

OUTCOME Medication adjustment

After Mr. Z is medically stable, he is voluntarily transferred to the inpatient psychiatric unit where he is stabilized on quetiapine, 200 mg/d, and duloxetine, 60 mg/d, and attends daily group activity, milieu, and individual therapy. Because of Mr. Z’s chronic affective instability and suicidality, we consider lithium for its anti-suicide effects, but decide against it because of lithium’s high lethality in an overdose and Mr. Z’s history of poor compliance and alcohol use.

Because of Mr. Z’s socioeconomic challenges, it is necessary to contact his extended family and social support system to be part of treatment and safety planning. After a week on the psychiatric unit, his mood symptoms stabilize and he is discharged to his family and friends in the area, with a short supply of quetiapine and duloxetine, and free follow-up care within 3 days of discharge. His mood is euthymic; his affect is broad range; his thought process is coherent and logical; he denies suicidal ideation; and can verbalize a logical and concrete safety plan. His support system assures us that Mr. Z will follow up with his appointments.

His DSM-522 discharge diagnoses are borderline personality disorder, bipolar I disorder, and suicidal behavior disorder, current.

The authors’ observations

SBC increases friction and mistrust between the police and the public, traumatizes officers who are forced to use deadly measures, and results in the death of the suicidal individual. As mental health professionals, we need to be aware of this form of suicide in our screening assessment. Training police to differentiate violent offenders from psychiatric patients could reduce the number of SBCs.9 As shown by the CIT model, educating officers on behaviors indicating a mental illness could lead to more psychiatric admissions rather than incarceration17 or death. We advocate for continuous collaborative work and cross training between the police and mental health professionals and for more research on the link between religiosity and the motivation to die by SBC, because there appears to be a not-yet quantified but strong link between them.

1. Hutson HR, Anglin D, Yarbrough J, et al. Suicide by cop. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;32(6):665-669.

2. Foote WE. Victim-precipitated homicide. In: Hall HV, ed. Lethal violence: a sourcebook on fatal domestic, acquaintance and stranger violence. London, United Kingdom: CRC Press; 1999:175-199.

3. Keram EA, Farrell BJ. Suicide by cop: issues in outcome and analysis. In: Sheehan DC, Warren JI, eds. Suicide and law enforcement. Quantico, VA: FBI Academy; 2001:587-597.

4. Violanti JM, Drylie JJ. Copicide: concepts, cases, and controversies of suicide by cop. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher, LTD; 2008.

5. Wolfgang ME. Suicide by means of victim-precipitated homicide. J Clin Exp Psychopathol Q Rev Psychiatry Neurol. 1959;20:335-349.

6. Mohandie K, Meloy JR. Clinical and forensic indicators of “suicide by cop.” J Forensic Sci. 2000;45(2):384-389.

7. Wright RK, Davis JH. Studies in the epidemiology of murder a proposed classification system. J Forensic Sci. 1977;22(2):464-470.

8. Miller L. Suicide by cop: causes, reactions, and practical intervention strategies. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2006;8(3):165-174.

9. Dewey L, Allwood M, Fava J, et al. Suicide by cop: clinical risks and subtypes. Arch Suicide Res. 2013;17(4):448-461.

10. Foster T, Gillespie K, McClelland R, et al. Risk factors for suicide independent of DSM-III-R Axis I disorder. Case-control psychological autopsy study in Northern Ireland. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:175-179.

11. Lindsay M, Lester D. Criteria for suicide-by-cop incidents. Psychol Rep. 2008;102(2):603-605.

12. Cheng AT, Mann AH, Chan KA. Personality disorder and suicide. A case-control study. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:441-446.

13. Mohandie K, Meloy JR, Collins PI. Suicide by cop among officer‐involved shooting cases. J Forensic Sci. 2009;54(2):456-462.

14. Falk J, Riepert T, Rothschild MA. A case of suicide-by-cop. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2004;6(3):194-196.

15. Homant RJ, Kennedy DB. Suicide by police: a proposed typology of law enforcement officer-assisted suicide. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management. 2000;23(3):339-355.

16. Lester D. Suicide as a staged performance. Comprehensive Psychology. 2015:4(1):1-6.

17. SpringerBriefs in psychology. Best practices for those with psychiatric disorder in the criminal justice system. In: Walker LE, Pann JM, Shapiro DL, et al. Best practices in law enforcement crisis Interventions with those with psychiatric disorder. 2015;11-18.

18. Homant RJ, Kennedy DB, Hupp R. Real and perceived danger in police officer assisted suicide. J Crim Justice. 2000;28(1):43-52.

19. Ernst CL, Goldberg JF. Antisuicide properties of psychotropic drugs: a critical review. Harv Review Psychiatry. 2004;12(1):14-41.

20. Al Jurdi RK, Swann A, Mathew SJ. Psychopharmacological agents and suicide risk reduction: ketamine and other approaches. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(10):81.

21. Fink M, Kellner CH, McCall WV. The role of ECT in suicide prevention. Journal ECT. 2014;30(1):5-9.

22. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

CASE Unresponsive and suicidal

Mr. Z, age 25, an unemployed immigrant from Eastern Europe, is found unresponsive at a subway station. Workup in the emergency room reveals a positive urine toxicology for benzodiazepines and a blood alcohol level of 101.6 mg/dL. When Mr. Z regains consciousness the next day, he says that he is suicidal. He recently broke up with his girlfriend and feels worthless, hopeless, and depressed. As a suicide attempt, he took quetiapine and diazepam chased with vodka.

Mr. Z reports a history of suicide attempts. He says he has been suffering from depression most of his life and has been diagnosed with bipolar I disorder and borderline personality disorder. His medication regimen consists of quetiapine, 200 mg/d, and duloxetine, 20 mg/d.

Before immigrating to the United States 5 years ago, he attempted to overdose on his mother’s prescribed diazepam and was in a coma for 2 days. Recently, he stole a bicycle with the intent of provoking the police to kill him. When caught, he deliberately disobeyed the officer’s order and advanced toward the officer in an aggressive manner. However, the officer stopped Mr. Z using a stun gun. Mr. Z reports that he still feels angry that his suicide attempt failed. He is an Orthodox Christian and says he is “very religious.”

[polldaddy:9731423]

The authors’ observations

The means of suicide differ among individuals. Some attempt suicide by themselves; others through the involuntary participation of others, such as the police. This is known as SBC. Other terms include “suicide by means of victim-precipitated homicide,”1 “hetero-suicide,”2 “suicide by proxy,”3 “copicide,”4 and “law enforcement-forced-assisted suicide.”5,6 SBC accounts for 10%7 to 36%6 of police shootings and can cause serious stress for the officers involved and creates a strain between the police and the community.8

SBC was first mentioned as “suicide by means of victim-precipitated homicide.” Wolfgang5 reported 588 cases of police officer-involved shooting in Philadelphia between January 1948 and December 31, 1952, and, concluded that 150 of these cases (26%) fit criteria for what the author termed “victim-precipitated homicide” because the victims involved were the direct precipitants of the situation leading to their death. Wolfgang stated:

Instead of a murderer performing the act of suicide by killing another person who represents the murder’s unconscious, and instead of a suicide representing the desire to kill turned on [the] self, the victim in these victim-precipitated homicide cases is considered to be a suicide prone [individual] who manifests his desire to destroy [him]self by engaging another person to perform the act.

The term “SBC” was coined in 1983 by Karl Harris, a Los Angeles County medical examiner.8 The social repercussions of this modality attracts media attention because of its negative social consequences.

Characteristics of SBC

SBC has characteristics similar to other means of suicide; it is more prevalent among men with psychiatric disorders, including major depression, bipolar disorders, schizophrenia, substance use disorders,9 poor stress response skills, recent stressors, and adverse life events,10 and history of suicide attempts.

Psychosocial characteristics include:

- mean age 31.8 years1

- male sex (98%)

- white (52%)

- approximately 40% involve some form of relationship conflict.6

In psychological autopsy studies, an estimated 70.5% of those involved in a SBC incident had ≥1 stressful life events,1 including terminal illness, loss of a job, a lawsuit, or domestic issues. However, the reason is unknown for the remaining 28% cases.2 Thirty-five percent of those involved in SBC incidents were married, 13.5% divorced, and 46.7% single.1 Seventy-seven percent had low socioeconomic status,11 with 49.3% unemployed at the time of the SBC incident.1

Pathological characteristics of SBC and other suicide means are similar. Among SBC cases, 39% had previously attempted suicide6; 56% have a psychiatric or chronic medical comorbidity. Alcohol and drug abuse were reported among 56% of individuals, and 66% had a criminal history.6 Additionally, comorbid psychiatric disorders, especially those of the impulsive and emotionally unstable types, such as borderline and antisocial personality disorder, have been found to play a major role in SBC incidents.12

Individual suicide vs SBC

Religious beliefs. The term “religiosity” is used to define an individual’s idiosyncratic religious belief or personal religious philosophy reconciling the concept of death by suicide and the afterlife. Although there are no studies that specifically reference the relationship between SBC and religiosity, religious belief and affiliation appear to be strong motivating factors. SBC victims might have an idiosyncratic view of religion related death by suicide. Whether suicide is performed while under delusional belief about God, the devil, or being possessed by demons,13 or to avoid the moral prohibition of most religious faiths in regard to suicide,6 the degree of religiosity in SBC is an important area for future research.

Mr. Z stated that his strong religious faith as an Orthodox Christian motivated the attempted SBC. He tried to provoke the officer to kill him, because as a devout Orthodox Christian, it is against his religious beliefs to kill himself. He reasoned that, because his beliefs preclude him from performing the suicidal act on his own,6,14 having an officer pull the trigger would relieve him from committing what he perceived as a sin.6

Lethal vs danger. Another difference is the level of urgency that individuals create around them when attempting SBC. Homant and Kennedy15 see this in terms of 2 ideas: lethal and danger. Lethal refers to the degree of harm posed toward the suicidal individual. Danger is the degree of harm posed by the suicidal individual toward others (ie, police officers, bystanders, hostages, family members, a spouse, etc.). SBC often is more dangerous and more lethal than other methods of suicide. SBC individuals might threaten the lives of others to provoke the police into using deadly force, such as aiming or brandishing a gun or weapon at police officers or bystanders, increasing the lethality and dangerousness of the situation. Individuals engaging in SBC might shoot or kill others to create a confrontation with the police in order to be killed in the process (Table16).

Instrumental vs expressive goals

Mohandie and Meloy6 identified 2 primary goals of those involved in SBC events: instrumental and expressive. Individuals in the instrumental category are:

- attempting to escape or avoid the consequences of criminal or shameful actions

- using the forced confrontation with police to reconcile a failed relationship

- hoping to avoid the exclusion clauses of life insurance policies

- rationalizing that while it may be morally wrong to commit suicide, being killed resolves the spiritual problem of suicide

- seeking what they believe to be a very effective and lethal means of accomplishing death.

An expressive goal is more personal and includes individuals who use the confrontation with the police to communicate:

- hopelessness, depression, and desperation

- a statement about their ultimate identification as victims

- their need to “save face” by dying or being forcibly overwhelmed rather than surrendering

- their intense power needs, rage, and revenge

- their need to draw attention to an important personal issue.

Mr. Z chose what he believed to be an efficiently lethal way of dying in accord with his religious faith, knowing that a confrontation with the police could have a fatal ending. This case represents an instrumental motivation to die by SBC that was religiously motivated.

[polldaddy:9731428]

The authors’ observations

SBC presents a specific and serious challenge for law enforcement personnel, and should be approached in a manner different than other crisis situations. Because many individuals engaging in SBC have a history of mental illness, officers with training in handling individuals with psychiatric disorders—known as Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) in many areas—should be deployed as first responders. CITs have been shown to:

- reduce arrest rates of individuals with psychiatric disorders

- increase referral rates to appropriate treatment

- decrease police injuries when responding to calls

- decrease the need for escalation with specialized tactical response teams, such as Special Weapons And Tactics.17

Identification of SBC behavior is crucial during police response. Indicators of a SBC include:

- refusal to comply with police order

- refusal to surrender

- lack of interest in getting out of a barricade or hostage situation alive.18

In approaching a SBC incident, responding officers should be non-confrontational and try to talk to the suicidal individual.8 If force is needed to resolve the crisis, non-lethal measures should be used first.8 Law enforcement and mental health professionals should suspect a SBC situation in individuals who have had prior police contact and are exhibiting behaviors outlined in the Table.16

Once suicidality is identified, it should be treated promptly. Patients who are at imminent risk to themselves or others should be hospitalized to maintain their safety. Similar to other suicide modalities, the primary risk factor for SBC is untreated or inadequately treated psychiatric illness. Therefore, the crux of managing SBC involves identifying and treating the underlying mental disorder.

Pharmacological treatment should be guided by the patient’s symptoms and psychiatric diagnosis. For suicidal behavior associated with bipolar depression and other affective disorders, lithium has evidence of reducing suicidality. Studies have shown a 5.5-fold reduction in suicide risk and a >13-fold reduction in completed suicides with lithium treatment.19 In patients with schizophrenia, clozapine has been shown to reduce suicide risk and is the only FDA-approved agent for this indication.19 Although antidepressants can effectively treat depression, there are no studies that show that 1 antidepressant is more effective than others in reducing suicidality. This might be because of the long latency period between treatment initiation and symptom relief. Ketamine, an N-methyl-

OUTCOME Medication adjustment

After Mr. Z is medically stable, he is voluntarily transferred to the inpatient psychiatric unit where he is stabilized on quetiapine, 200 mg/d, and duloxetine, 60 mg/d, and attends daily group activity, milieu, and individual therapy. Because of Mr. Z’s chronic affective instability and suicidality, we consider lithium for its anti-suicide effects, but decide against it because of lithium’s high lethality in an overdose and Mr. Z’s history of poor compliance and alcohol use.

Because of Mr. Z’s socioeconomic challenges, it is necessary to contact his extended family and social support system to be part of treatment and safety planning. After a week on the psychiatric unit, his mood symptoms stabilize and he is discharged to his family and friends in the area, with a short supply of quetiapine and duloxetine, and free follow-up care within 3 days of discharge. His mood is euthymic; his affect is broad range; his thought process is coherent and logical; he denies suicidal ideation; and can verbalize a logical and concrete safety plan. His support system assures us that Mr. Z will follow up with his appointments.

His DSM-522 discharge diagnoses are borderline personality disorder, bipolar I disorder, and suicidal behavior disorder, current.

The authors’ observations

SBC increases friction and mistrust between the police and the public, traumatizes officers who are forced to use deadly measures, and results in the death of the suicidal individual. As mental health professionals, we need to be aware of this form of suicide in our screening assessment. Training police to differentiate violent offenders from psychiatric patients could reduce the number of SBCs.9 As shown by the CIT model, educating officers on behaviors indicating a mental illness could lead to more psychiatric admissions rather than incarceration17 or death. We advocate for continuous collaborative work and cross training between the police and mental health professionals and for more research on the link between religiosity and the motivation to die by SBC, because there appears to be a not-yet quantified but strong link between them.

CASE Unresponsive and suicidal

Mr. Z, age 25, an unemployed immigrant from Eastern Europe, is found unresponsive at a subway station. Workup in the emergency room reveals a positive urine toxicology for benzodiazepines and a blood alcohol level of 101.6 mg/dL. When Mr. Z regains consciousness the next day, he says that he is suicidal. He recently broke up with his girlfriend and feels worthless, hopeless, and depressed. As a suicide attempt, he took quetiapine and diazepam chased with vodka.

Mr. Z reports a history of suicide attempts. He says he has been suffering from depression most of his life and has been diagnosed with bipolar I disorder and borderline personality disorder. His medication regimen consists of quetiapine, 200 mg/d, and duloxetine, 20 mg/d.

Before immigrating to the United States 5 years ago, he attempted to overdose on his mother’s prescribed diazepam and was in a coma for 2 days. Recently, he stole a bicycle with the intent of provoking the police to kill him. When caught, he deliberately disobeyed the officer’s order and advanced toward the officer in an aggressive manner. However, the officer stopped Mr. Z using a stun gun. Mr. Z reports that he still feels angry that his suicide attempt failed. He is an Orthodox Christian and says he is “very religious.”

[polldaddy:9731423]

The authors’ observations

The means of suicide differ among individuals. Some attempt suicide by themselves; others through the involuntary participation of others, such as the police. This is known as SBC. Other terms include “suicide by means of victim-precipitated homicide,”1 “hetero-suicide,”2 “suicide by proxy,”3 “copicide,”4 and “law enforcement-forced-assisted suicide.”5,6 SBC accounts for 10%7 to 36%6 of police shootings and can cause serious stress for the officers involved and creates a strain between the police and the community.8

SBC was first mentioned as “suicide by means of victim-precipitated homicide.” Wolfgang5 reported 588 cases of police officer-involved shooting in Philadelphia between January 1948 and December 31, 1952, and, concluded that 150 of these cases (26%) fit criteria for what the author termed “victim-precipitated homicide” because the victims involved were the direct precipitants of the situation leading to their death. Wolfgang stated:

Instead of a murderer performing the act of suicide by killing another person who represents the murder’s unconscious, and instead of a suicide representing the desire to kill turned on [the] self, the victim in these victim-precipitated homicide cases is considered to be a suicide prone [individual] who manifests his desire to destroy [him]self by engaging another person to perform the act.

The term “SBC” was coined in 1983 by Karl Harris, a Los Angeles County medical examiner.8 The social repercussions of this modality attracts media attention because of its negative social consequences.

Characteristics of SBC

SBC has characteristics similar to other means of suicide; it is more prevalent among men with psychiatric disorders, including major depression, bipolar disorders, schizophrenia, substance use disorders,9 poor stress response skills, recent stressors, and adverse life events,10 and history of suicide attempts.

Psychosocial characteristics include:

- mean age 31.8 years1

- male sex (98%)

- white (52%)

- approximately 40% involve some form of relationship conflict.6

In psychological autopsy studies, an estimated 70.5% of those involved in a SBC incident had ≥1 stressful life events,1 including terminal illness, loss of a job, a lawsuit, or domestic issues. However, the reason is unknown for the remaining 28% cases.2 Thirty-five percent of those involved in SBC incidents were married, 13.5% divorced, and 46.7% single.1 Seventy-seven percent had low socioeconomic status,11 with 49.3% unemployed at the time of the SBC incident.1

Pathological characteristics of SBC and other suicide means are similar. Among SBC cases, 39% had previously attempted suicide6; 56% have a psychiatric or chronic medical comorbidity. Alcohol and drug abuse were reported among 56% of individuals, and 66% had a criminal history.6 Additionally, comorbid psychiatric disorders, especially those of the impulsive and emotionally unstable types, such as borderline and antisocial personality disorder, have been found to play a major role in SBC incidents.12

Individual suicide vs SBC

Religious beliefs. The term “religiosity” is used to define an individual’s idiosyncratic religious belief or personal religious philosophy reconciling the concept of death by suicide and the afterlife. Although there are no studies that specifically reference the relationship between SBC and religiosity, religious belief and affiliation appear to be strong motivating factors. SBC victims might have an idiosyncratic view of religion related death by suicide. Whether suicide is performed while under delusional belief about God, the devil, or being possessed by demons,13 or to avoid the moral prohibition of most religious faiths in regard to suicide,6 the degree of religiosity in SBC is an important area for future research.

Mr. Z stated that his strong religious faith as an Orthodox Christian motivated the attempted SBC. He tried to provoke the officer to kill him, because as a devout Orthodox Christian, it is against his religious beliefs to kill himself. He reasoned that, because his beliefs preclude him from performing the suicidal act on his own,6,14 having an officer pull the trigger would relieve him from committing what he perceived as a sin.6

Lethal vs danger. Another difference is the level of urgency that individuals create around them when attempting SBC. Homant and Kennedy15 see this in terms of 2 ideas: lethal and danger. Lethal refers to the degree of harm posed toward the suicidal individual. Danger is the degree of harm posed by the suicidal individual toward others (ie, police officers, bystanders, hostages, family members, a spouse, etc.). SBC often is more dangerous and more lethal than other methods of suicide. SBC individuals might threaten the lives of others to provoke the police into using deadly force, such as aiming or brandishing a gun or weapon at police officers or bystanders, increasing the lethality and dangerousness of the situation. Individuals engaging in SBC might shoot or kill others to create a confrontation with the police in order to be killed in the process (Table16).

Instrumental vs expressive goals

Mohandie and Meloy6 identified 2 primary goals of those involved in SBC events: instrumental and expressive. Individuals in the instrumental category are:

- attempting to escape or avoid the consequences of criminal or shameful actions

- using the forced confrontation with police to reconcile a failed relationship

- hoping to avoid the exclusion clauses of life insurance policies

- rationalizing that while it may be morally wrong to commit suicide, being killed resolves the spiritual problem of suicide

- seeking what they believe to be a very effective and lethal means of accomplishing death.

An expressive goal is more personal and includes individuals who use the confrontation with the police to communicate:

- hopelessness, depression, and desperation

- a statement about their ultimate identification as victims

- their need to “save face” by dying or being forcibly overwhelmed rather than surrendering

- their intense power needs, rage, and revenge

- their need to draw attention to an important personal issue.

Mr. Z chose what he believed to be an efficiently lethal way of dying in accord with his religious faith, knowing that a confrontation with the police could have a fatal ending. This case represents an instrumental motivation to die by SBC that was religiously motivated.

[polldaddy:9731428]

The authors’ observations

SBC presents a specific and serious challenge for law enforcement personnel, and should be approached in a manner different than other crisis situations. Because many individuals engaging in SBC have a history of mental illness, officers with training in handling individuals with psychiatric disorders—known as Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) in many areas—should be deployed as first responders. CITs have been shown to:

- reduce arrest rates of individuals with psychiatric disorders

- increase referral rates to appropriate treatment

- decrease police injuries when responding to calls

- decrease the need for escalation with specialized tactical response teams, such as Special Weapons And Tactics.17

Identification of SBC behavior is crucial during police response. Indicators of a SBC include:

- refusal to comply with police order

- refusal to surrender

- lack of interest in getting out of a barricade or hostage situation alive.18

In approaching a SBC incident, responding officers should be non-confrontational and try to talk to the suicidal individual.8 If force is needed to resolve the crisis, non-lethal measures should be used first.8 Law enforcement and mental health professionals should suspect a SBC situation in individuals who have had prior police contact and are exhibiting behaviors outlined in the Table.16

Once suicidality is identified, it should be treated promptly. Patients who are at imminent risk to themselves or others should be hospitalized to maintain their safety. Similar to other suicide modalities, the primary risk factor for SBC is untreated or inadequately treated psychiatric illness. Therefore, the crux of managing SBC involves identifying and treating the underlying mental disorder.

Pharmacological treatment should be guided by the patient’s symptoms and psychiatric diagnosis. For suicidal behavior associated with bipolar depression and other affective disorders, lithium has evidence of reducing suicidality. Studies have shown a 5.5-fold reduction in suicide risk and a >13-fold reduction in completed suicides with lithium treatment.19 In patients with schizophrenia, clozapine has been shown to reduce suicide risk and is the only FDA-approved agent for this indication.19 Although antidepressants can effectively treat depression, there are no studies that show that 1 antidepressant is more effective than others in reducing suicidality. This might be because of the long latency period between treatment initiation and symptom relief. Ketamine, an N-methyl-

OUTCOME Medication adjustment

After Mr. Z is medically stable, he is voluntarily transferred to the inpatient psychiatric unit where he is stabilized on quetiapine, 200 mg/d, and duloxetine, 60 mg/d, and attends daily group activity, milieu, and individual therapy. Because of Mr. Z’s chronic affective instability and suicidality, we consider lithium for its anti-suicide effects, but decide against it because of lithium’s high lethality in an overdose and Mr. Z’s history of poor compliance and alcohol use.

Because of Mr. Z’s socioeconomic challenges, it is necessary to contact his extended family and social support system to be part of treatment and safety planning. After a week on the psychiatric unit, his mood symptoms stabilize and he is discharged to his family and friends in the area, with a short supply of quetiapine and duloxetine, and free follow-up care within 3 days of discharge. His mood is euthymic; his affect is broad range; his thought process is coherent and logical; he denies suicidal ideation; and can verbalize a logical and concrete safety plan. His support system assures us that Mr. Z will follow up with his appointments.

His DSM-522 discharge diagnoses are borderline personality disorder, bipolar I disorder, and suicidal behavior disorder, current.

The authors’ observations

SBC increases friction and mistrust between the police and the public, traumatizes officers who are forced to use deadly measures, and results in the death of the suicidal individual. As mental health professionals, we need to be aware of this form of suicide in our screening assessment. Training police to differentiate violent offenders from psychiatric patients could reduce the number of SBCs.9 As shown by the CIT model, educating officers on behaviors indicating a mental illness could lead to more psychiatric admissions rather than incarceration17 or death. We advocate for continuous collaborative work and cross training between the police and mental health professionals and for more research on the link between religiosity and the motivation to die by SBC, because there appears to be a not-yet quantified but strong link between them.

1. Hutson HR, Anglin D, Yarbrough J, et al. Suicide by cop. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;32(6):665-669.

2. Foote WE. Victim-precipitated homicide. In: Hall HV, ed. Lethal violence: a sourcebook on fatal domestic, acquaintance and stranger violence. London, United Kingdom: CRC Press; 1999:175-199.

3. Keram EA, Farrell BJ. Suicide by cop: issues in outcome and analysis. In: Sheehan DC, Warren JI, eds. Suicide and law enforcement. Quantico, VA: FBI Academy; 2001:587-597.

4. Violanti JM, Drylie JJ. Copicide: concepts, cases, and controversies of suicide by cop. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher, LTD; 2008.

5. Wolfgang ME. Suicide by means of victim-precipitated homicide. J Clin Exp Psychopathol Q Rev Psychiatry Neurol. 1959;20:335-349.

6. Mohandie K, Meloy JR. Clinical and forensic indicators of “suicide by cop.” J Forensic Sci. 2000;45(2):384-389.

7. Wright RK, Davis JH. Studies in the epidemiology of murder a proposed classification system. J Forensic Sci. 1977;22(2):464-470.

8. Miller L. Suicide by cop: causes, reactions, and practical intervention strategies. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2006;8(3):165-174.

9. Dewey L, Allwood M, Fava J, et al. Suicide by cop: clinical risks and subtypes. Arch Suicide Res. 2013;17(4):448-461.

10. Foster T, Gillespie K, McClelland R, et al. Risk factors for suicide independent of DSM-III-R Axis I disorder. Case-control psychological autopsy study in Northern Ireland. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:175-179.

11. Lindsay M, Lester D. Criteria for suicide-by-cop incidents. Psychol Rep. 2008;102(2):603-605.

12. Cheng AT, Mann AH, Chan KA. Personality disorder and suicide. A case-control study. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:441-446.

13. Mohandie K, Meloy JR, Collins PI. Suicide by cop among officer‐involved shooting cases. J Forensic Sci. 2009;54(2):456-462.

14. Falk J, Riepert T, Rothschild MA. A case of suicide-by-cop. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2004;6(3):194-196.

15. Homant RJ, Kennedy DB. Suicide by police: a proposed typology of law enforcement officer-assisted suicide. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management. 2000;23(3):339-355.

16. Lester D. Suicide as a staged performance. Comprehensive Psychology. 2015:4(1):1-6.

17. SpringerBriefs in psychology. Best practices for those with psychiatric disorder in the criminal justice system. In: Walker LE, Pann JM, Shapiro DL, et al. Best practices in law enforcement crisis Interventions with those with psychiatric disorder. 2015;11-18.

18. Homant RJ, Kennedy DB, Hupp R. Real and perceived danger in police officer assisted suicide. J Crim Justice. 2000;28(1):43-52.

19. Ernst CL, Goldberg JF. Antisuicide properties of psychotropic drugs: a critical review. Harv Review Psychiatry. 2004;12(1):14-41.

20. Al Jurdi RK, Swann A, Mathew SJ. Psychopharmacological agents and suicide risk reduction: ketamine and other approaches. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(10):81.

21. Fink M, Kellner CH, McCall WV. The role of ECT in suicide prevention. Journal ECT. 2014;30(1):5-9.

22. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

1. Hutson HR, Anglin D, Yarbrough J, et al. Suicide by cop. Ann Emerg Med. 1998;32(6):665-669.

2. Foote WE. Victim-precipitated homicide. In: Hall HV, ed. Lethal violence: a sourcebook on fatal domestic, acquaintance and stranger violence. London, United Kingdom: CRC Press; 1999:175-199.

3. Keram EA, Farrell BJ. Suicide by cop: issues in outcome and analysis. In: Sheehan DC, Warren JI, eds. Suicide and law enforcement. Quantico, VA: FBI Academy; 2001:587-597.

4. Violanti JM, Drylie JJ. Copicide: concepts, cases, and controversies of suicide by cop. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas Publisher, LTD; 2008.

5. Wolfgang ME. Suicide by means of victim-precipitated homicide. J Clin Exp Psychopathol Q Rev Psychiatry Neurol. 1959;20:335-349.

6. Mohandie K, Meloy JR. Clinical and forensic indicators of “suicide by cop.” J Forensic Sci. 2000;45(2):384-389.

7. Wright RK, Davis JH. Studies in the epidemiology of murder a proposed classification system. J Forensic Sci. 1977;22(2):464-470.

8. Miller L. Suicide by cop: causes, reactions, and practical intervention strategies. Int J Emerg Ment Health. 2006;8(3):165-174.

9. Dewey L, Allwood M, Fava J, et al. Suicide by cop: clinical risks and subtypes. Arch Suicide Res. 2013;17(4):448-461.

10. Foster T, Gillespie K, McClelland R, et al. Risk factors for suicide independent of DSM-III-R Axis I disorder. Case-control psychological autopsy study in Northern Ireland. Br J Psychiatry. 1999;175:175-179.

11. Lindsay M, Lester D. Criteria for suicide-by-cop incidents. Psychol Rep. 2008;102(2):603-605.

12. Cheng AT, Mann AH, Chan KA. Personality disorder and suicide. A case-control study. Br J Psychiatry. 1997;170:441-446.

13. Mohandie K, Meloy JR, Collins PI. Suicide by cop among officer‐involved shooting cases. J Forensic Sci. 2009;54(2):456-462.

14. Falk J, Riepert T, Rothschild MA. A case of suicide-by-cop. Leg Med (Tokyo). 2004;6(3):194-196.

15. Homant RJ, Kennedy DB. Suicide by police: a proposed typology of law enforcement officer-assisted suicide. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management. 2000;23(3):339-355.

16. Lester D. Suicide as a staged performance. Comprehensive Psychology. 2015:4(1):1-6.

17. SpringerBriefs in psychology. Best practices for those with psychiatric disorder in the criminal justice system. In: Walker LE, Pann JM, Shapiro DL, et al. Best practices in law enforcement crisis Interventions with those with psychiatric disorder. 2015;11-18.

18. Homant RJ, Kennedy DB, Hupp R. Real and perceived danger in police officer assisted suicide. J Crim Justice. 2000;28(1):43-52.

19. Ernst CL, Goldberg JF. Antisuicide properties of psychotropic drugs: a critical review. Harv Review Psychiatry. 2004;12(1):14-41.

20. Al Jurdi RK, Swann A, Mathew SJ. Psychopharmacological agents and suicide risk reduction: ketamine and other approaches. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2015;17(10):81.

21. Fink M, Kellner CH, McCall WV. The role of ECT in suicide prevention. Journal ECT. 2014;30(1):5-9.

22. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

The importance of ‘delivery factors’ and ‘patient factors’ in the therapeutic alliance

The therapeutic alliance (interchangeably, the therapeutic relationship) is a subjective measure of the relationship between a clinician and a patient. It is an indicator of clinical trustworthiness: what a patient is referring to when she (he) expresses trust in her provider. The therapeutic alliance also is known as the working alliance, the therapeutic bond, and the helping alliance,1 and it is an important factor in patient satisfaction ratings—the gauging parameter through which clinicians and institutions measure the quality of care they provide.2

A therapeutic alliance is essential to the delivery of psychiatric care. Itself, it can be a healing factor3 and has been linked to patients’ adherence to treatment and continuation of care.4 For example, psychiatric patients who perceive the therapeutic alliance more positively have:

- a better long-term health outcome after discharge

- a significantly better psychological quality of life5

- a better follow-up record of outpatient care after inpatient discharge4,6

- better adherence to prescribed treatment7

- a reduced likelihood of relapse and readmission.6

Patient satisfaction is an indirect measure of the therapeutic alliance; many variables of the therapeutic relationship can affect that satisfaction. In this article, we call those variables patient factors and delivery factors; our aim, using the example of 2 hypothetical cases, is to highlight their importance in patients’ perception of the therapeutic alliance they have with providers.

CASE Paranoid delusions lead to termination of care

Mr. D, age 21, unmarried, unemployed, and with no medical or psychiatric history, is transferred from the medical floor to the inpatient psychiatric unit after coming to the hospital’s emergency room (ER) with a report of chest pain. Workup on the medical floor was negative for a serious cardiac event.

On questioning, Mr. D tells the team that his chest pain is caused by National Security Agency (NSA) satellites “locking” onto his heart and causing veins in his heart to “pop.”

Mr. D agrees to be transferred to the psychiatric unit. Once there, however, he refuses to take the psychotropic medications that have been prescribed or to comply with the balance of the treatment protocol. He is adamant about the influence of NSA satellites, and requests daily imaging to locate evidence of the path of the satellite tracking device that he claims is inside his body.

The treatment team repeatedly refuses to comply with Mr. D’s demand for imaging. He becomes angry and says that he does not think he is getting proper care because the nature of his problem is medical, not psychiatric.

Mr. D repeatedly asserts that he will not take any of the psychotropic medications that have been prescribed for him and will not attend follow-up appointments with the psychiatry team because he does not need treatment. He accuses the treatment team of conspiring with the NSA and causing his chest pain.

Mr. D asks to be discharged.

Patient factors: Unmodifiable and static

As Mr. D’s case exemplifies, patient factors are a set of elements, intrinsic to a given patient, that affect that patient’s perceptions independent of the quality of the care delivered. Included among patient factors are personal sociodemographic and psychopathological characteristics. These patient factors influence the therapeutic relationship in many ways.

Sociodemographics. It has been reported that patients of minority heritage and those who are male, young, and unmarried tend to be less satisfied with medical treatment in general and with psychiatric inpatient treatment in particular.8,9 Females and older patients, on the other hand, are more likely to be satisfied with the perceived delivery of care and the therapeutic alliance.8-10

Psychopathology affects patients’ perception of the delivery of care and the therapeutic alliance. Patients who are highly distressed psychologically and those who suffer chronic psychiatric illness, for example, tend to perceive themselves as having benefitted less from treatment than healthier counterparts.9,11 Such patients also tend to see their therapeutic outcome in a much less favorable light.11,12 Patients with borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder12-14 and those hospitalized involuntarily8 tend to (1) be less satisfied with their therapeutic outcome and (2) see the therapeutic alliance less favorably compared with those who do not have these psychopathologies.

CASE Denied a blanket, she feels like a 'burden'

Ms. X, age 34, married and a homemaker, has a history of bipolar I disorder. She brings herself to the ER complaining of depression and suicidal ideation.

After Ms. X is seen by the psychiatry consult service in the ER, she reports that she feels frustrated and angry and thinks that the hospital’s physicians do not really want to help her. She states that she felt that the ER staff “dismissed” her, in part because she spent 4 hours in the ER waiting room before she was given a bed.

Ms. X says that, once she was placed in a room, she felt that the nursing staff and medical assistants ignored her because they did not give her the extra blanket she requested. She said she was cold as a result, while she waited to see the psychiatrist and the ER physician.

Ms. X states that she came to the ER seeking help because she felt depressed and thought that no one cared about her. Coming to the hospital made her feel worse, after all, she said, because there she has been treated like she is a burden, much like she is treated at home.

Delivery factors: Amenable to change

These mutable elements of the therapeutic alliance are dependent on the quality of the care, as they were in Ms. X’s case; they can be changed. Included among delivery factors is the quality of the relationship between provider and patient—that is, how the psychiatrist and the nursing staff relate to the patient.

Perceptions are key. Delivery factors rank as one of the most important elements that influence the patient’s perception of the therapeutic alliance.15,16 Given the objectives of psychiatric treatment—to relieve psychiatric symptoms, improve patient functioning, and alleviate psychological distress—it is no wonder that delivery factors play an important role in the perception of the therapeutic alliance: The quality of the provider−patient relationship is the axis around which treatment takes place. This relationship constantly ranks high on surveys of what is important to patients15—especially in an inpatient psychiatric setting.

Attitudes are modifiable. From the treating psychiatrist to nursing and ancillary staffs, all team members need to express attitudes and behaviors that reflect positively on the patient.17 Behaviors such as involving the patient fully in therapeutic decision-making; exuding an attitude of caring, equanimity, empathy, sincerity, and respect; and listening to the patient’s concerns can go a long way to improving the therapeutic relationship. Displaying such attitudes and behaviors also help improve the larger vision of psychiatric intervention: to bring about positive therapeutic changes.

Summing up

Ratings of the therapeutic alliance are the currency of patient satisfaction. The value of this therapeutic currency is affected by delivery factors, which are adjustable, and patient factors, which are not. Taken together, however, both types of factors are the foundation of patient satisfaction and the therapeutic alliance.

1. Martin DJ, Garske JP, Davis MK. Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(3):438-450.

2. Chue P. The relationship between patient satisfaction and treatment outcomes in schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(suppl 6):38-56.

3. Priebe S, McCabe R. The therapeutic relationship in psychiatric settings. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Suppl. 2006;113(429):69-72.

4. Bowersox NW, Bohnert AS, Ganoczy D, et al. Inpatient psychiatric care experience and its relationship to posthospitalization treatment participation. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(6):554-562.

5. Zendjidjian XY, Baumstarck K, Auquier P, et al. Satisfaction of hospitalized psychiatry patients: why should clinicians care? Patient Preference Adherence. 2014;8:575-583.

6. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Stolar M. Patient satisfaction and administrative measures as indicators of the quality of mental health care. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50(8):1053-1058.

7. Sapra M, Weiden PJ, Schooler NR, et al. Reasons for adherence and nonadherence: a pilot study comparing first- and multi-episode schizophrenia patients. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2014;7(4):199-206.

8. Rosenheck R, Wilson NJ, Meterko M. Influence of patient and hospital factors on consumer satisfaction with inpatient mental health treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48(12):1553-1561.

9. Hoff RA, Rosenheck RA, Meterko M, et al. Mental illness as a predictor of satisfaction with inpatient care at Veterans Affairs hospitals. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50(5):680-685.

10. Bjørngaard JH, Ruud T, Friis S. The impact of mental illness on patient satisfaction with the therapeutic relationship: a multilevel analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42(10):803-809.

11. Greenley JR, Young TB, Schoenherr RA. Psychological distress and patient satisfaction. Med Care. 1982;20(4):373-385.

12. Svensson B, Hansson L. Patient satisfaction with inpatient psychiatric care. The influence of personality traits, diagnosis and perceived coercion. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;90(5):379-384.

13. Köhler S, Unger T, Hoffmann S, et al. Patient satisfaction with inpatient psychiatric treatment and its relation to treatment outcome in unipolar depression and schizophrenia. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2015;19(2):119-123.

14. Holcomb WR, Parker JC, Leong GB, et al. Customer satisfaction and self-reported treatment outcomes among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(7):929-934.

15. Hansson L, Björkman T, Berglund I. What is important in psychiatric inpatient care? Quality of care from the patient’s perspective. Qual Assur Health Care. 1993;5(1):41-48.

16. Remnik Y, Melamed Y, Swartz M, et al. Patients’ satisfaction with psychiatric inpatient care. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2003;41(3):208-212.

17. Norcross JC, ed. Psychotherapy relationships that work: therapist contributions and responsiveness to patients. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2002.

The therapeutic alliance (interchangeably, the therapeutic relationship) is a subjective measure of the relationship between a clinician and a patient. It is an indicator of clinical trustworthiness: what a patient is referring to when she (he) expresses trust in her provider. The therapeutic alliance also is known as the working alliance, the therapeutic bond, and the helping alliance,1 and it is an important factor in patient satisfaction ratings—the gauging parameter through which clinicians and institutions measure the quality of care they provide.2

A therapeutic alliance is essential to the delivery of psychiatric care. Itself, it can be a healing factor3 and has been linked to patients’ adherence to treatment and continuation of care.4 For example, psychiatric patients who perceive the therapeutic alliance more positively have:

- a better long-term health outcome after discharge

- a significantly better psychological quality of life5

- a better follow-up record of outpatient care after inpatient discharge4,6

- better adherence to prescribed treatment7

- a reduced likelihood of relapse and readmission.6

Patient satisfaction is an indirect measure of the therapeutic alliance; many variables of the therapeutic relationship can affect that satisfaction. In this article, we call those variables patient factors and delivery factors; our aim, using the example of 2 hypothetical cases, is to highlight their importance in patients’ perception of the therapeutic alliance they have with providers.

CASE Paranoid delusions lead to termination of care

Mr. D, age 21, unmarried, unemployed, and with no medical or psychiatric history, is transferred from the medical floor to the inpatient psychiatric unit after coming to the hospital’s emergency room (ER) with a report of chest pain. Workup on the medical floor was negative for a serious cardiac event.

On questioning, Mr. D tells the team that his chest pain is caused by National Security Agency (NSA) satellites “locking” onto his heart and causing veins in his heart to “pop.”

Mr. D agrees to be transferred to the psychiatric unit. Once there, however, he refuses to take the psychotropic medications that have been prescribed or to comply with the balance of the treatment protocol. He is adamant about the influence of NSA satellites, and requests daily imaging to locate evidence of the path of the satellite tracking device that he claims is inside his body.

The treatment team repeatedly refuses to comply with Mr. D’s demand for imaging. He becomes angry and says that he does not think he is getting proper care because the nature of his problem is medical, not psychiatric.

Mr. D repeatedly asserts that he will not take any of the psychotropic medications that have been prescribed for him and will not attend follow-up appointments with the psychiatry team because he does not need treatment. He accuses the treatment team of conspiring with the NSA and causing his chest pain.

Mr. D asks to be discharged.

Patient factors: Unmodifiable and static

As Mr. D’s case exemplifies, patient factors are a set of elements, intrinsic to a given patient, that affect that patient’s perceptions independent of the quality of the care delivered. Included among patient factors are personal sociodemographic and psychopathological characteristics. These patient factors influence the therapeutic relationship in many ways.

Sociodemographics. It has been reported that patients of minority heritage and those who are male, young, and unmarried tend to be less satisfied with medical treatment in general and with psychiatric inpatient treatment in particular.8,9 Females and older patients, on the other hand, are more likely to be satisfied with the perceived delivery of care and the therapeutic alliance.8-10

Psychopathology affects patients’ perception of the delivery of care and the therapeutic alliance. Patients who are highly distressed psychologically and those who suffer chronic psychiatric illness, for example, tend to perceive themselves as having benefitted less from treatment than healthier counterparts.9,11 Such patients also tend to see their therapeutic outcome in a much less favorable light.11,12 Patients with borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder12-14 and those hospitalized involuntarily8 tend to (1) be less satisfied with their therapeutic outcome and (2) see the therapeutic alliance less favorably compared with those who do not have these psychopathologies.

CASE Denied a blanket, she feels like a 'burden'

Ms. X, age 34, married and a homemaker, has a history of bipolar I disorder. She brings herself to the ER complaining of depression and suicidal ideation.

After Ms. X is seen by the psychiatry consult service in the ER, she reports that she feels frustrated and angry and thinks that the hospital’s physicians do not really want to help her. She states that she felt that the ER staff “dismissed” her, in part because she spent 4 hours in the ER waiting room before she was given a bed.

Ms. X says that, once she was placed in a room, she felt that the nursing staff and medical assistants ignored her because they did not give her the extra blanket she requested. She said she was cold as a result, while she waited to see the psychiatrist and the ER physician.

Ms. X states that she came to the ER seeking help because she felt depressed and thought that no one cared about her. Coming to the hospital made her feel worse, after all, she said, because there she has been treated like she is a burden, much like she is treated at home.

Delivery factors: Amenable to change

These mutable elements of the therapeutic alliance are dependent on the quality of the care, as they were in Ms. X’s case; they can be changed. Included among delivery factors is the quality of the relationship between provider and patient—that is, how the psychiatrist and the nursing staff relate to the patient.

Perceptions are key. Delivery factors rank as one of the most important elements that influence the patient’s perception of the therapeutic alliance.15,16 Given the objectives of psychiatric treatment—to relieve psychiatric symptoms, improve patient functioning, and alleviate psychological distress—it is no wonder that delivery factors play an important role in the perception of the therapeutic alliance: The quality of the provider−patient relationship is the axis around which treatment takes place. This relationship constantly ranks high on surveys of what is important to patients15—especially in an inpatient psychiatric setting.

Attitudes are modifiable. From the treating psychiatrist to nursing and ancillary staffs, all team members need to express attitudes and behaviors that reflect positively on the patient.17 Behaviors such as involving the patient fully in therapeutic decision-making; exuding an attitude of caring, equanimity, empathy, sincerity, and respect; and listening to the patient’s concerns can go a long way to improving the therapeutic relationship. Displaying such attitudes and behaviors also help improve the larger vision of psychiatric intervention: to bring about positive therapeutic changes.

Summing up

Ratings of the therapeutic alliance are the currency of patient satisfaction. The value of this therapeutic currency is affected by delivery factors, which are adjustable, and patient factors, which are not. Taken together, however, both types of factors are the foundation of patient satisfaction and the therapeutic alliance.

The therapeutic alliance (interchangeably, the therapeutic relationship) is a subjective measure of the relationship between a clinician and a patient. It is an indicator of clinical trustworthiness: what a patient is referring to when she (he) expresses trust in her provider. The therapeutic alliance also is known as the working alliance, the therapeutic bond, and the helping alliance,1 and it is an important factor in patient satisfaction ratings—the gauging parameter through which clinicians and institutions measure the quality of care they provide.2

A therapeutic alliance is essential to the delivery of psychiatric care. Itself, it can be a healing factor3 and has been linked to patients’ adherence to treatment and continuation of care.4 For example, psychiatric patients who perceive the therapeutic alliance more positively have:

- a better long-term health outcome after discharge

- a significantly better psychological quality of life5

- a better follow-up record of outpatient care after inpatient discharge4,6

- better adherence to prescribed treatment7

- a reduced likelihood of relapse and readmission.6

Patient satisfaction is an indirect measure of the therapeutic alliance; many variables of the therapeutic relationship can affect that satisfaction. In this article, we call those variables patient factors and delivery factors; our aim, using the example of 2 hypothetical cases, is to highlight their importance in patients’ perception of the therapeutic alliance they have with providers.

CASE Paranoid delusions lead to termination of care

Mr. D, age 21, unmarried, unemployed, and with no medical or psychiatric history, is transferred from the medical floor to the inpatient psychiatric unit after coming to the hospital’s emergency room (ER) with a report of chest pain. Workup on the medical floor was negative for a serious cardiac event.

On questioning, Mr. D tells the team that his chest pain is caused by National Security Agency (NSA) satellites “locking” onto his heart and causing veins in his heart to “pop.”

Mr. D agrees to be transferred to the psychiatric unit. Once there, however, he refuses to take the psychotropic medications that have been prescribed or to comply with the balance of the treatment protocol. He is adamant about the influence of NSA satellites, and requests daily imaging to locate evidence of the path of the satellite tracking device that he claims is inside his body.

The treatment team repeatedly refuses to comply with Mr. D’s demand for imaging. He becomes angry and says that he does not think he is getting proper care because the nature of his problem is medical, not psychiatric.

Mr. D repeatedly asserts that he will not take any of the psychotropic medications that have been prescribed for him and will not attend follow-up appointments with the psychiatry team because he does not need treatment. He accuses the treatment team of conspiring with the NSA and causing his chest pain.

Mr. D asks to be discharged.

Patient factors: Unmodifiable and static

As Mr. D’s case exemplifies, patient factors are a set of elements, intrinsic to a given patient, that affect that patient’s perceptions independent of the quality of the care delivered. Included among patient factors are personal sociodemographic and psychopathological characteristics. These patient factors influence the therapeutic relationship in many ways.

Sociodemographics. It has been reported that patients of minority heritage and those who are male, young, and unmarried tend to be less satisfied with medical treatment in general and with psychiatric inpatient treatment in particular.8,9 Females and older patients, on the other hand, are more likely to be satisfied with the perceived delivery of care and the therapeutic alliance.8-10

Psychopathology affects patients’ perception of the delivery of care and the therapeutic alliance. Patients who are highly distressed psychologically and those who suffer chronic psychiatric illness, for example, tend to perceive themselves as having benefitted less from treatment than healthier counterparts.9,11 Such patients also tend to see their therapeutic outcome in a much less favorable light.11,12 Patients with borderline personality disorder and antisocial personality disorder12-14 and those hospitalized involuntarily8 tend to (1) be less satisfied with their therapeutic outcome and (2) see the therapeutic alliance less favorably compared with those who do not have these psychopathologies.

CASE Denied a blanket, she feels like a 'burden'

Ms. X, age 34, married and a homemaker, has a history of bipolar I disorder. She brings herself to the ER complaining of depression and suicidal ideation.

After Ms. X is seen by the psychiatry consult service in the ER, she reports that she feels frustrated and angry and thinks that the hospital’s physicians do not really want to help her. She states that she felt that the ER staff “dismissed” her, in part because she spent 4 hours in the ER waiting room before she was given a bed.

Ms. X says that, once she was placed in a room, she felt that the nursing staff and medical assistants ignored her because they did not give her the extra blanket she requested. She said she was cold as a result, while she waited to see the psychiatrist and the ER physician.

Ms. X states that she came to the ER seeking help because she felt depressed and thought that no one cared about her. Coming to the hospital made her feel worse, after all, she said, because there she has been treated like she is a burden, much like she is treated at home.

Delivery factors: Amenable to change

These mutable elements of the therapeutic alliance are dependent on the quality of the care, as they were in Ms. X’s case; they can be changed. Included among delivery factors is the quality of the relationship between provider and patient—that is, how the psychiatrist and the nursing staff relate to the patient.

Perceptions are key. Delivery factors rank as one of the most important elements that influence the patient’s perception of the therapeutic alliance.15,16 Given the objectives of psychiatric treatment—to relieve psychiatric symptoms, improve patient functioning, and alleviate psychological distress—it is no wonder that delivery factors play an important role in the perception of the therapeutic alliance: The quality of the provider−patient relationship is the axis around which treatment takes place. This relationship constantly ranks high on surveys of what is important to patients15—especially in an inpatient psychiatric setting.

Attitudes are modifiable. From the treating psychiatrist to nursing and ancillary staffs, all team members need to express attitudes and behaviors that reflect positively on the patient.17 Behaviors such as involving the patient fully in therapeutic decision-making; exuding an attitude of caring, equanimity, empathy, sincerity, and respect; and listening to the patient’s concerns can go a long way to improving the therapeutic relationship. Displaying such attitudes and behaviors also help improve the larger vision of psychiatric intervention: to bring about positive therapeutic changes.

Summing up

Ratings of the therapeutic alliance are the currency of patient satisfaction. The value of this therapeutic currency is affected by delivery factors, which are adjustable, and patient factors, which are not. Taken together, however, both types of factors are the foundation of patient satisfaction and the therapeutic alliance.

1. Martin DJ, Garske JP, Davis MK. Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(3):438-450.

2. Chue P. The relationship between patient satisfaction and treatment outcomes in schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(suppl 6):38-56.

3. Priebe S, McCabe R. The therapeutic relationship in psychiatric settings. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Suppl. 2006;113(429):69-72.

4. Bowersox NW, Bohnert AS, Ganoczy D, et al. Inpatient psychiatric care experience and its relationship to posthospitalization treatment participation. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(6):554-562.

5. Zendjidjian XY, Baumstarck K, Auquier P, et al. Satisfaction of hospitalized psychiatry patients: why should clinicians care? Patient Preference Adherence. 2014;8:575-583.

6. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Stolar M. Patient satisfaction and administrative measures as indicators of the quality of mental health care. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50(8):1053-1058.

7. Sapra M, Weiden PJ, Schooler NR, et al. Reasons for adherence and nonadherence: a pilot study comparing first- and multi-episode schizophrenia patients. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2014;7(4):199-206.

8. Rosenheck R, Wilson NJ, Meterko M. Influence of patient and hospital factors on consumer satisfaction with inpatient mental health treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48(12):1553-1561.

9. Hoff RA, Rosenheck RA, Meterko M, et al. Mental illness as a predictor of satisfaction with inpatient care at Veterans Affairs hospitals. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50(5):680-685.

10. Bjørngaard JH, Ruud T, Friis S. The impact of mental illness on patient satisfaction with the therapeutic relationship: a multilevel analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42(10):803-809.

11. Greenley JR, Young TB, Schoenherr RA. Psychological distress and patient satisfaction. Med Care. 1982;20(4):373-385.

12. Svensson B, Hansson L. Patient satisfaction with inpatient psychiatric care. The influence of personality traits, diagnosis and perceived coercion. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;90(5):379-384.

13. Köhler S, Unger T, Hoffmann S, et al. Patient satisfaction with inpatient psychiatric treatment and its relation to treatment outcome in unipolar depression and schizophrenia. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2015;19(2):119-123.

14. Holcomb WR, Parker JC, Leong GB, et al. Customer satisfaction and self-reported treatment outcomes among psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatr Serv. 1998;49(7):929-934.

15. Hansson L, Björkman T, Berglund I. What is important in psychiatric inpatient care? Quality of care from the patient’s perspective. Qual Assur Health Care. 1993;5(1):41-48.

16. Remnik Y, Melamed Y, Swartz M, et al. Patients’ satisfaction with psychiatric inpatient care. Isr J Psychiatry Relat Sci. 2003;41(3):208-212.

17. Norcross JC, ed. Psychotherapy relationships that work: therapist contributions and responsiveness to patients. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 2002.

1. Martin DJ, Garske JP, Davis MK. Relation of the therapeutic alliance with outcome and other variables: a meta-analytic review. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2000;68(3):438-450.

2. Chue P. The relationship between patient satisfaction and treatment outcomes in schizophrenia. J Psychopharmacol. 2006;20(suppl 6):38-56.

3. Priebe S, McCabe R. The therapeutic relationship in psychiatric settings. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica Suppl. 2006;113(429):69-72.

4. Bowersox NW, Bohnert AS, Ganoczy D, et al. Inpatient psychiatric care experience and its relationship to posthospitalization treatment participation. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(6):554-562.

5. Zendjidjian XY, Baumstarck K, Auquier P, et al. Satisfaction of hospitalized psychiatry patients: why should clinicians care? Patient Preference Adherence. 2014;8:575-583.

6. Druss BG, Rosenheck RA, Stolar M. Patient satisfaction and administrative measures as indicators of the quality of mental health care. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50(8):1053-1058.

7. Sapra M, Weiden PJ, Schooler NR, et al. Reasons for adherence and nonadherence: a pilot study comparing first- and multi-episode schizophrenia patients. Clin Schizophr Relat Psychoses. 2014;7(4):199-206.

8. Rosenheck R, Wilson NJ, Meterko M. Influence of patient and hospital factors on consumer satisfaction with inpatient mental health treatment. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48(12):1553-1561.

9. Hoff RA, Rosenheck RA, Meterko M, et al. Mental illness as a predictor of satisfaction with inpatient care at Veterans Affairs hospitals. Psychiatr Serv. 1999;50(5):680-685.

10. Bjørngaard JH, Ruud T, Friis S. The impact of mental illness on patient satisfaction with the therapeutic relationship: a multilevel analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2007;42(10):803-809.

11. Greenley JR, Young TB, Schoenherr RA. Psychological distress and patient satisfaction. Med Care. 1982;20(4):373-385.

12. Svensson B, Hansson L. Patient satisfaction with inpatient psychiatric care. The influence of personality traits, diagnosis and perceived coercion. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1994;90(5):379-384.

13. Köhler S, Unger T, Hoffmann S, et al. Patient satisfaction with inpatient psychiatric treatment and its relation to treatment outcome in unipolar depression and schizophrenia. Int J Psychiatry Clin Pract. 2015;19(2):119-123.