User login

Cannabinoid-based medications for pain

Against the backdrop of an increasing opioid use epidemic and a marked acceleration of prescription opioid–related deaths,1,2 there has been an impetus to explore the usefulness of alternative and co-analgesic agents to assist patients with chronic pain. Preclinical studies employing animal-based models of human pain syndromes have demonstrated that cannabis and chemicals derived from cannabis extracts may mitigate several pain conditions.3

Because there are significant comorbidities between psychiatric disorders and chronic pain, psychiatrists are likely to care for patients with chronic pain. As the availability of and interest in cannabinoid-based medications (CBM) increases, psychiatrists will need to be apprised of the utility, adverse effects, and potential drug interactions of these agents.

The endocannabinoid system and cannabis receptors

The endogenous cannabinoid (endocannabinoid) system is abundantly present within the peripheral and central nervous systems. The first identified, and best studied, endocannabinoids are N-arachidonoyl-ethanolamine (AEA; anandamide) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG).4 Unlike typical neurotransmitters, AEA and 2-AG are not stored within vesicles within presynaptic neuron axons. Instead, they are lipophilic molecules produced on demand, synthesized from phospholipids (ie, arachidonic acid derivatives) at the membranes of post-synaptic neurons, and released into the synapse directly.5

Acting as retrograde messengers, the endocannabinoids traverse the synapse, binding to receptors located on the axons of the presynaptic neuron. Two receptors—CB1 and CB2—have been most extensively studied and characterized.6,7 These receptors couple to Gi/o-proteins to inhibit adenylate cyclase, decreasing Ca2+ conductance and increasing K+ conductance.8 Once activated, cannabinoid receptors modulate neurotransmitter release from presynaptic axon terminals. Evidence points to a similar retrograde signaling between neurons and glial cells. Shortly after receptor activation, the endocannabinoids are deactivated by the actions of a transporter mechanism and enzyme degradation.9,10

The endocannabinoid system and pain transmission

Cannabinoid receptors are present in pain transmission circuits spanning from the peripheral sensory nerve endings (from which pain signals originate) to the spinal cord and supraspinal regions within the brain.11-14 CB1 receptors are abundantly present within the CNS, including regions involved in pain transmission. Binding to CB1 receptors, endocannabinoids modulate neurotransmission that impacts pain transmission centrally. Endocannabinoids can also indirectly modulate opiate and N-methyl-

By contrast, CB2 receptors are predominantly localized to peripheral tissues and immune cells, although there has been some discovery of their presence within the CNS (eg, on microglia). Endocannabinoid activation of CB2 receptors is thought to modulate the activity of peripheral afferent pain fibers and immune-mediated neuroinflammatory processes—such as inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis and mast cell degranulation—that can precipitate and maintain chronic pain states.16-18

Evidence garnered from preclinical (animal) studies points to the role of the endocannabinoid system in modulating normal pain transmission (see Manzanares et al3 for details). These studies offer a putative basis for understanding how exogenous cannabinoid congeners might serve to ameliorate pain transmission in pathophysiologic states, including chronic pain.

Continue to: Cannabinoid-based medications

Cannabinoid-based medications

Marijuana contains multiple components (cannabinoids). The most extensively studied are delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). Because it predominantly binds CB1 receptors centrally, THC is the major psychoactive component of cannabis; it promotes sleep and appetite, influences anxiety, and produces the “high” associated with cannabis use. By contrast, CBD weakly binds CB1 and thus exerts minimal or no psychoactive effects.19

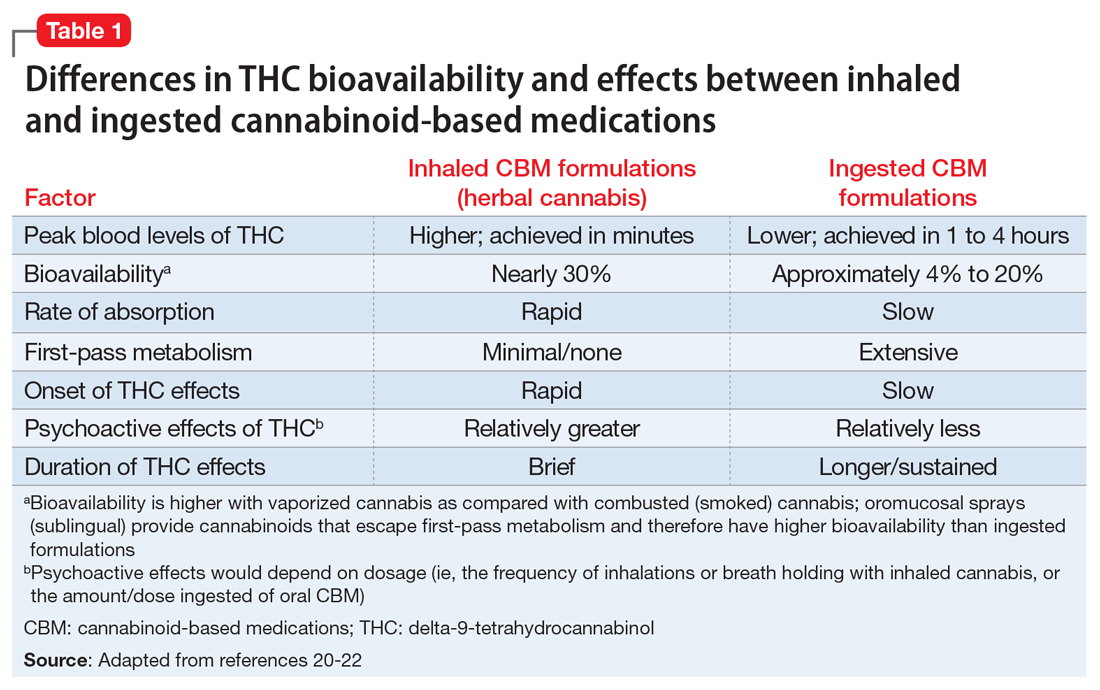

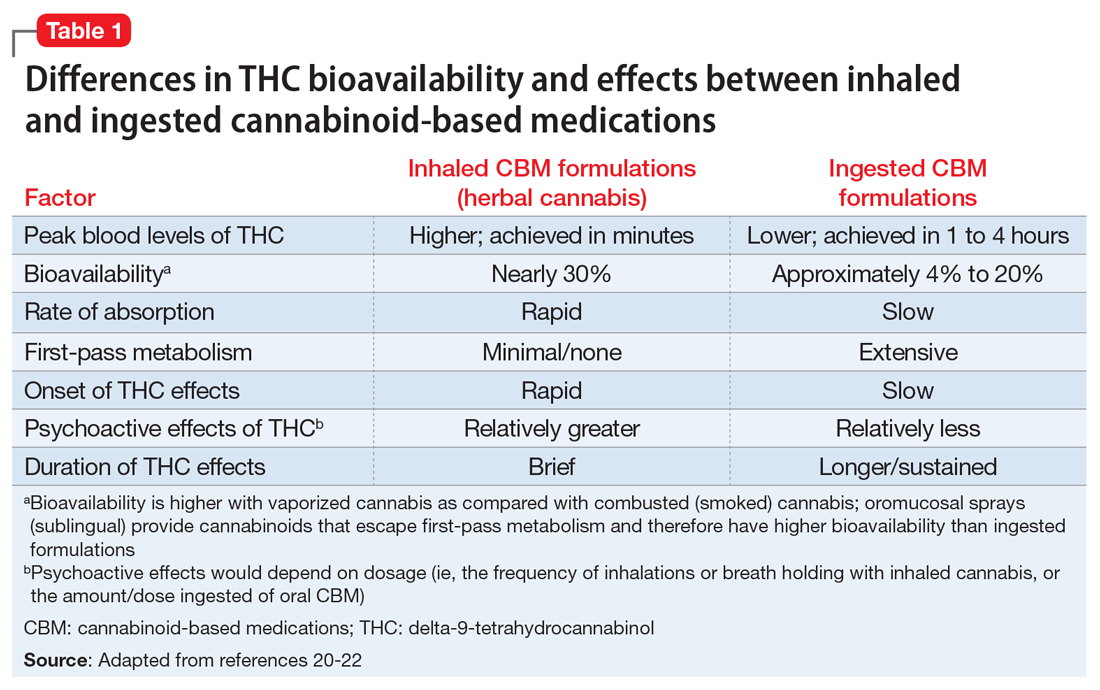

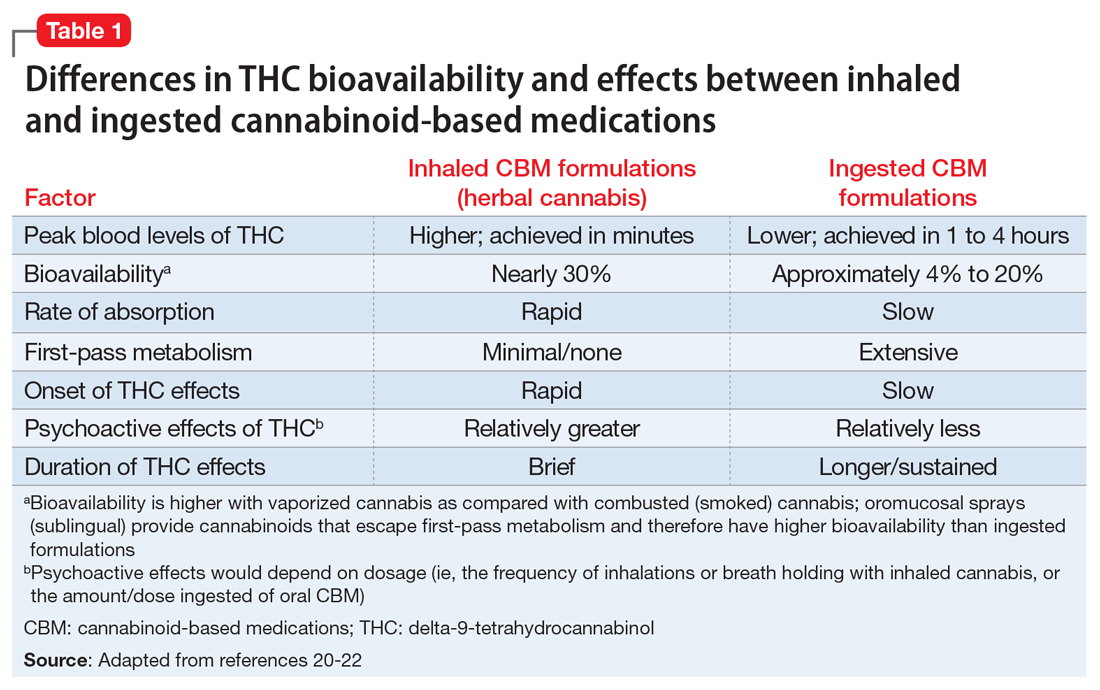

Cannabinoid absorption, metabolism, bioavailability, and clinical effects vary depending on the formulation and method of administration (Table 1).20-22 THC and CBD content and potency in inhaled cannabis can vary significantly depending on the strains of the cannabis plant and manner of cultivation.23 To standardize approaches for administering cannabinoids in clinical trials and for clinical use, researchers have developed pharmaceutical analogs that contain extracted chemicals or synthetic chemicals similar to THC and/or CBD.

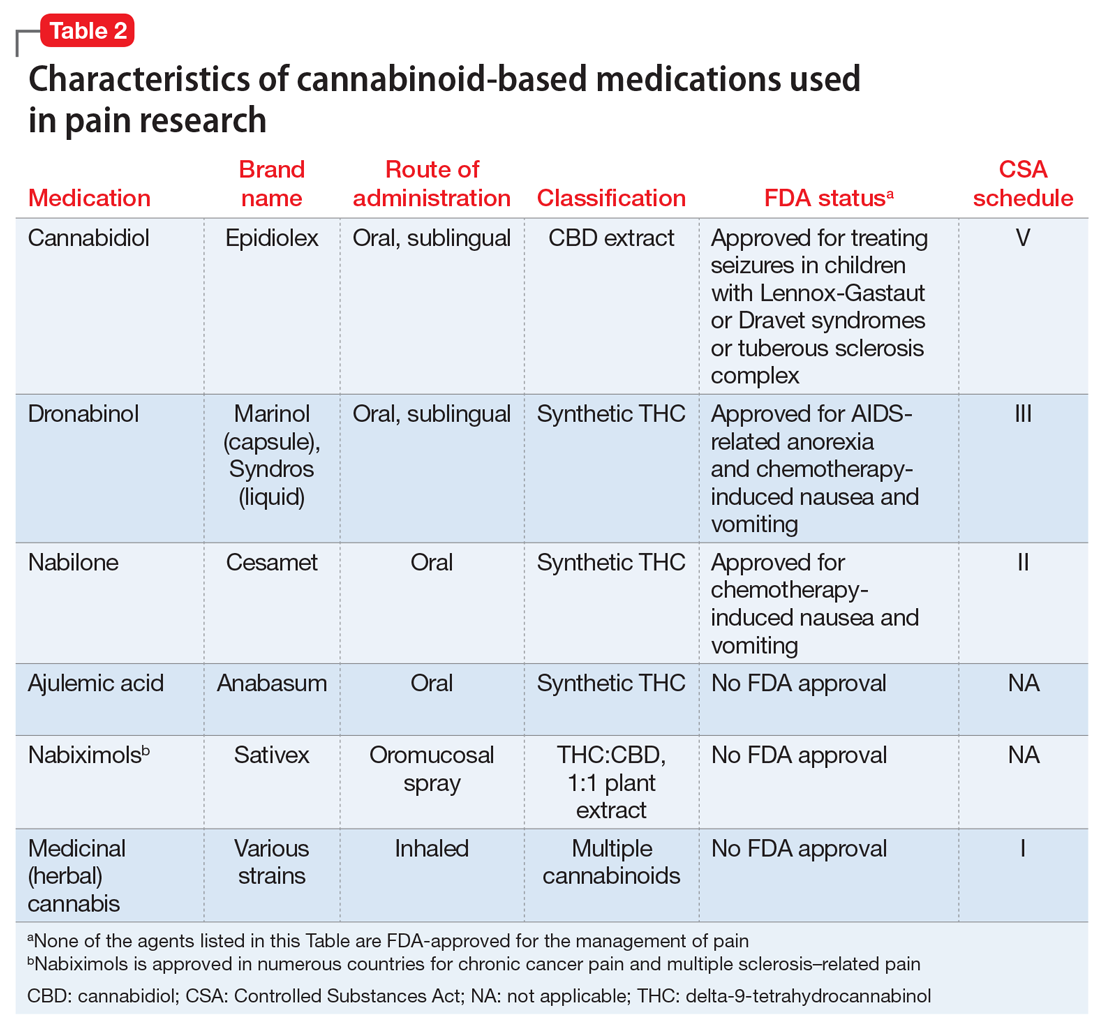

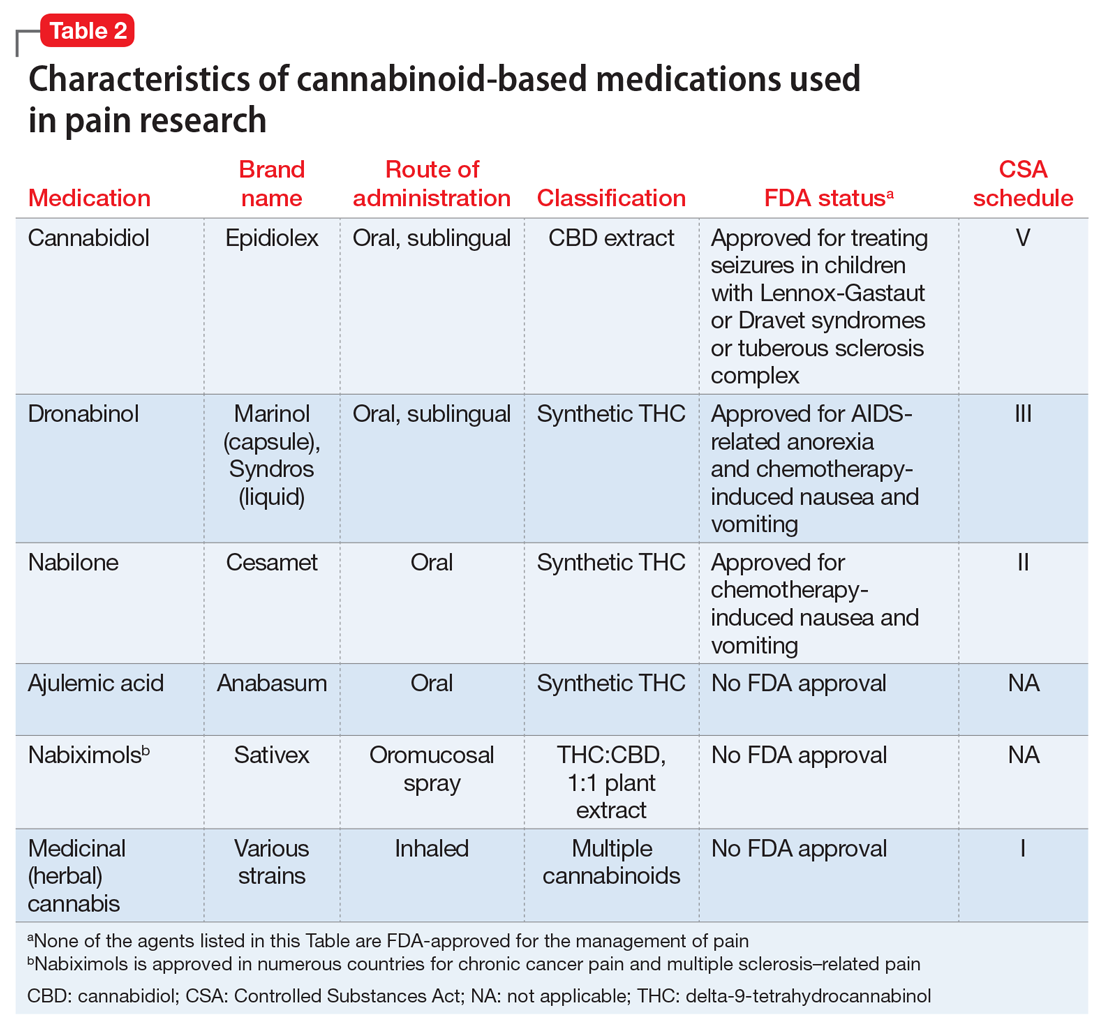

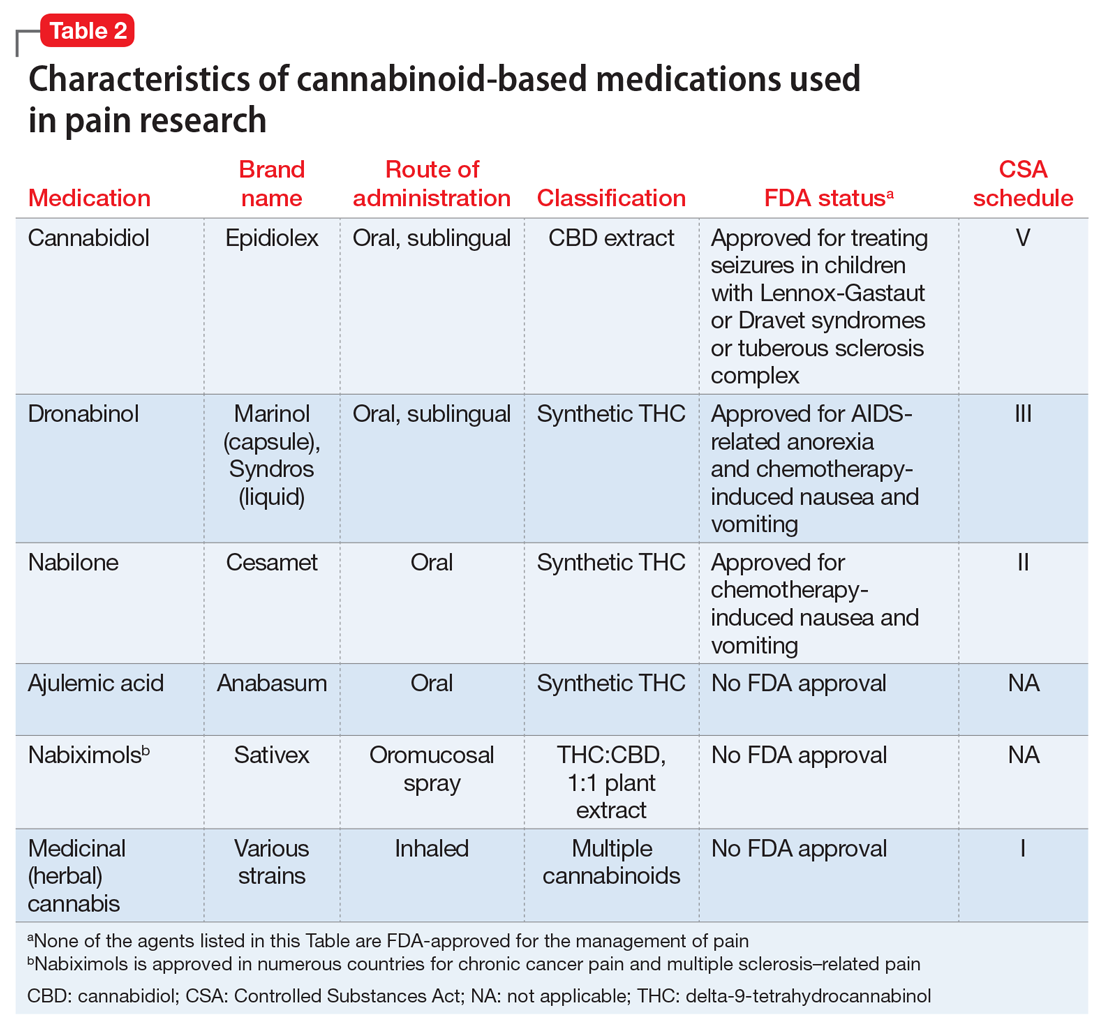

In this article, CBM refers to smoked/vaporized herbal cannabis as well as pharmaceutical cannabis analogs. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of CBM commonly used in studies investigating their use for managing pain conditions.

CBM for chronic pain

The literature base examining the role of CBM for managing chronic nonmalignant and malignant pain of varying etiologies is rapidly expanding. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have focused on inhaled/smoked products and related cannabinoid medications, some of which are FDA-approved (Table 2).

A multitude of other cannabinoid-based products are currently commercially available to consumers, including tincture and oil-based products; over-the-counter CBD products; and several other formulations of CBM (eg, edible and suppository products). Because such products are not standardized or quality-controlled,24 RCTs have not assessed their efficacy for mitigating pain. Consequently, the findings summarized in this article do not address the utility of these agents.

Continue to: CBM for non-cancer pain

CBM for non-cancer pain

Neuropathic pain. Randomized controlled trials have assessed the pain-mitigating effects of various CBM, including inhaled cannabis, synthetic THC, plant-extracted CBD, and a THC/CBD spray. Studies have shown that inhaled/vaporized cannabis can produce short-term pain reduction in patients with chronic neuropathic pain of diverse etiologies, including diabetes mellitus-, HIV-, trauma-, and medication-induced neuropathies.22,25,26 Similar beneficial effects have been observed with the use of cannabis analogues (eg, nabiximols).25,26-29

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews have determined that most of these RCTs were of low-to-moderate quality.26,30 Meta-analyses have revealed divergent and conflicting results because of differences in the inclusion and exclusion criteria used to select RCTs for analysis and differences in the standards with which the quality of evidence were determined.25,30

Overall, the benefit of CBM for mitigating neuropathic pain is promising, but the effectiveness may not be robust.30,31 Several noteworthy caveats limit the interpretation of the results of these RCTs:

- due to the small sample sizes and brief durations of study, questions remain regarding the extent to which effects are generalizable, whether the benefits are sustained, and whether adverse effects emerge over time with continued use

- most RCTs evaluated inhaled (herbal) cannabis and nabiximols; there is little data on the effectiveness of other CBM formulations25,26,30

- the pain-mitigating effects of CBM were usually compared with those of placebo; the comparative efficacy against agents commonly used to treat neuropathic pain remains largely unexamined

- these RCTs typically compared mean pain severity score differences between cannabis-treated and placebo groups using standard subjective rating scales of pain intensity, such as the Numerical Rating Scale or Visual Analogue Scale. Customarily, the pain literature has used a 30% or 50% reduction in pain severity from baseline as an indicator of significant clinical improvement.32,33 The RCTs of CBM for neuropathic pain rarely used this standard, which makes it unclear whether CBM results in clinically significant pain reductions30

- indirect measures of effectiveness (ie, whether using CBM reduces the need for opioids or other analgesics to manage pain) were seldom reported in these RCTs.

Due to these limitations, clinical guidelines and systematic reviews consider CBM as a third- or fourth-line therapy for patients experiencing chronic neuropathic pain for whom conventional agents such as anticonvulsants and antidepressants have failed.34,35

Spasticity in multiple sclerosis (MS). Several RCTs have assessed the use of CBM for MS-related spasticity, although few were deemed to be high quality. Nabiximols and synthetic THC were effective in managing spasticity and reducing pain severity associated with muscle spasms.36 Generally, investigations revealed that CBM were associated with improvements in subjective measures of spasticity, but these were not born out in clinical, objective measures.26,37 The efficacy of smoked cannabis was uncertain.37 The existing literature on CBM for MS-related spasticity does not address dosing, duration of effects, tolerability, or comparative effectiveness against conventional anti-spasm medications.36,37

Continue to: Other chronic pain conditions

Other chronic pain conditions. CBM have also been studied for their usefulness in several other noncancer chronic conditions, including Crohn’s disease, inflammatory bowel disease, fibromyalgia, and other rheumatologic pain conditions.22,31,38-40 However, a solid foundation of empirical work to inform their utility for managing pain in these conditions is lacking.

CBM for cancer pain

Anecdotal evidence suggests that inhaled cannabis has promising pain-mitigating effects in patients with advanced cancer.41-43 There is a dearth of high-quality RCTs assessing the utility of CBM in patients with cancer pain.43-45 The types of CBM used and dosing strategies varied across RCTs, which makes it difficult to infer how best to treat patients with cancer pain. The agents studied included nabiximols, THC spray, and synthetic THC capsules.43-45 Although some studies have demonstrated that synthetic THC and nabiximols have potential for reducing subjective pain ratings compared with placebo,46,47 these results were inconsistent.46,48 Oromucosal nabiximols did not appear to confer any additional analgesic benefit in patients who were already prescribed opioids.31,45

The benefit of CBM for mitigating cancer pain is promising, but it remains difficult to know how to position the use of CBM in managing cancer pain. Limitations in the cancer literature include:

- the RCTs addressing CBM use for cancer pain were often brief, which raises questions about the long-term effectiveness and adverse effects of these agents

- tolerability and dosing limits encountered due to adverse effects were seldom reported43,45

- the types of cancer pain that patients had were often quite diverse. The small sample sizes and the heterogeneity of conditions included in these RCTs limit the ability to determine whether pain-mitigating effects might vary according to type of cancer-related pain.31,45

Despite these limitations, some clinical guidelines and systematic reviews have suggested that CBM have some role in addressing refractory malignant pain conditions.49

Psychiatric considerations related to CBM

As of November 2020, 36 states had legalized the use of cannabis for medical purposes, typically for painful conditions, despite the fact that empirical evidence to support their efficacy is mixed.50 In light of recent changes in both the legal and popular attitudes regarding cannabis, the implications of legalizing CBM remains to be seen. For example, some research suggests that adults with pain are vulnerable to frequent nonmedical cannabis use and/or cannabis use disorder.51 Although well-intended, the legalization of CBM use might represent society’s next misstep in the quest to address the suffering of patients with chronic pain. Some evidence shows that cannabis use and cannabis use disorders increase in states that have legalized medical marijuana.52,53 Psychiatrists will be on the front lines of addressing any potential consequences arising from the use of CBM for treating pain.

Continue to: Psychiatric disorders and CBM

Psychiatric disorders and CBM. The psychological impact of CBM use among patients enduring chronic pain can include sedation, cognitive/attention disturbance, and fatigue. These adverse effects can limit the utility of such agents.22,29,45

Contraindications for CBM use, and conditions for which CBM ought to be used with caution, are listed in Table 354,55.The safety of CBM, particularly in patients with chronic pain and psychiatric disorders, has not been examined. Patients with psychiatric disorders may be poor candidates for medical cannabis. Epidemiologic data suggest that recreational cannabis use is positively associated both cross-sectionally and prospectively with psychotic spectrum disorders, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms, including panic disorder.56 Psychotic reactions have also been associated with CBM (dronabinol and nabilone).57 Cannabis use also has been associated with an earlier onset of, and lower remission rates of, symptoms associated with bipolar disorder.58,59 Consequently, patients who have been diagnosed with or are at risk for developing any of the aforementioned conditions may not be suitable candidates for CBM. If CBM are used, patients should be closely monitored for the emergence/exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms. The frequency and extent of follow-up is not clear, however. Because of its reduced propensity to produce psychoactive effects, CBD may be safer than THC for managing pain in individuals who have or are vulnerable to developing psychiatric disorders.

There is a lack of evidence to support the use of CBM for treating primary depressive disorders, general anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, or psychosis.60,61 Very low-quality evidence suggests that CBM could lead to a small improvement in anxiety among individuals with noncancer pain and MS.60 However, interpreting causality is complicated. It is plausible that, for some patients, subjective improvement in pain severity may be related to reduced anxiety.62 Conversely, it is equally plausible that reductions in emotional distress may reduce the propensity to attend to, and thus magnify, pain severity. In the latter case, the indirect impact of reducing pain by modifying emotional distress can be impacted by the type and dose of CBM used. For example, low concentrations of THC produce anxiolytic effects, but high concentrations may be anxiety-provoking.63,64

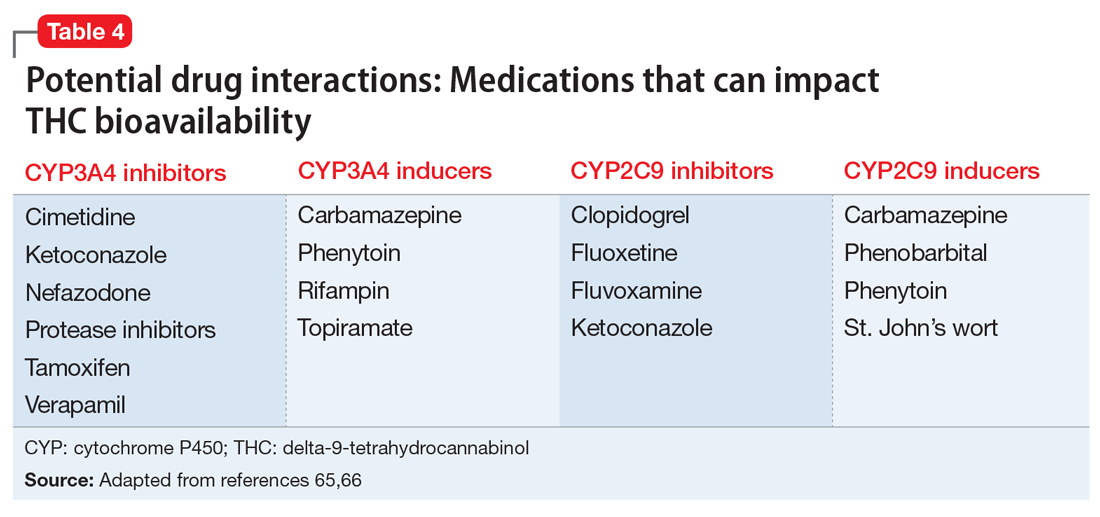

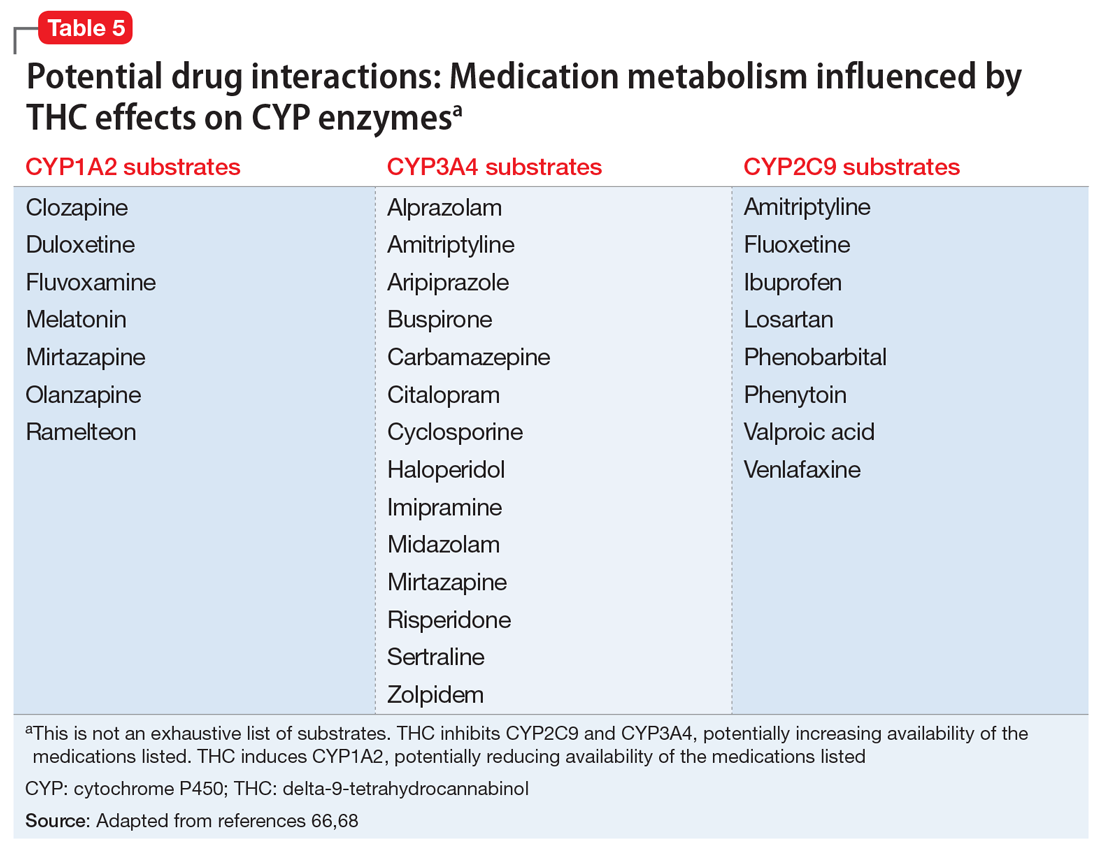

Several potential pharmacokinetic drug interactions may arise between herbal cannabis or CBM and other medications (Table 465,66). THC and CBD are both metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2C19 and 3A4.65,66 In addition, THC is also metabolized by CYP2C9. Medications that inhibit or induce these enzymes can increase or decrease the bioavailability of THC and CBD.67

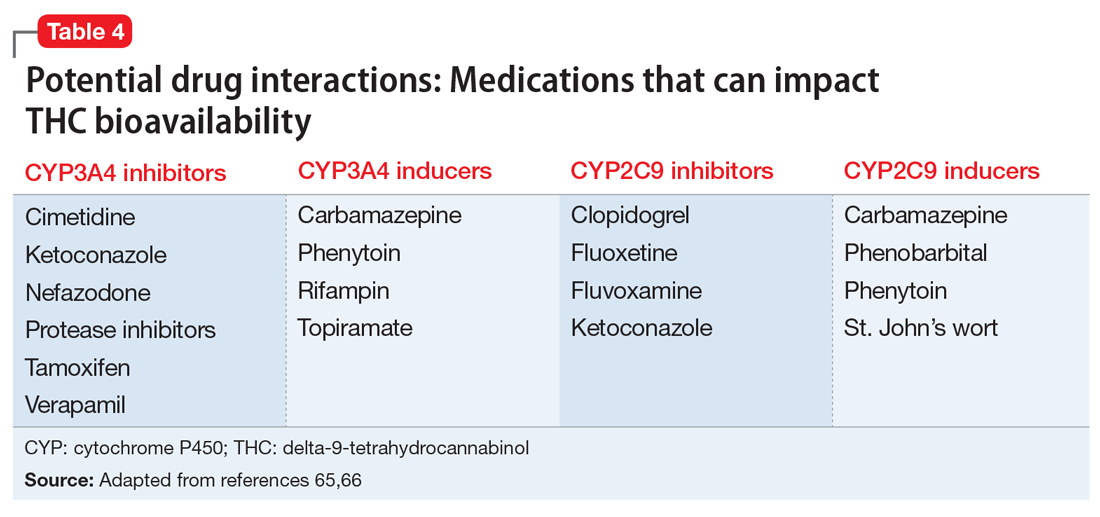

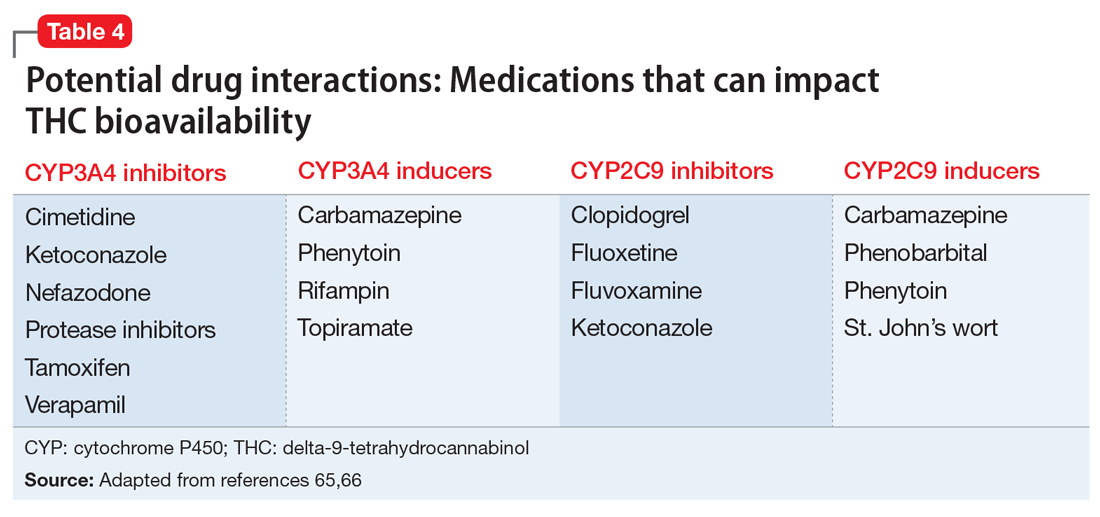

Simultaneously, cannabinoids can impact the bioavailability of co-prescribed medications (Table 566,68). Although such CYP enzyme interactions remain a theoretical possibility, it is uncertain whether significant perturbations in plasma concentrations (and clinical effects) have been encountered with prescription medications when co-administered with CBM.69 Nonetheless, patients receiving CBM should be closely monitored for their response to prescribed medications.70

Continue to: Potential CYP enzyme interactions...

Potential CYP enzyme interactions aside, clinicians need to consider the additive effects that may occur when CBM are combined with sympathomimetic agents (eg, tachycardia, hypertension); CNS depressants such as alcohol, benzodiazepines, and opioids (eg, drowsiness, ataxia); or anticholinergics (eg, tachycardia, confusion).71 Inhaled herbal cannabis contains mutagens and can result in lung damage, exacerbations of chronic bronchitis, and certain types of cancer.54,72 Co-prescribing benzodiazepines may be contraindicated in light of their effects on respiratory rate and effort.

The THC contained in CBM produces hormonal effects (ie, significantly increases plasma levels of ghrelin and leptin and decreases peptide YY levels)73 that affect appetite and can produce weight gain. This may be problematic for patients receiving psychoactive medications associated with increased risk of weight gain and dyslipidemia. Because of the association between cannabis use and motor vehicle accidents, patients whose jobs require them to drive or operate industrial equipment may not be ideal candidates for CBM, especially if such patients also consume alcohol or are prescribed benzodiazepines and/or sedative hypnotics.74 Lastly, due to their lipophilicity, cannabinoids cross the placental barrier and can be found in breast milk75 and therefore can affect pregnancy outcomes and neurodevelopment.

Bottom Line

The popularity of cannabinoid-based medications (CBM) for the treatment of chronic pain conditions is growing, but the interest in their use may be outpacing the evidence supporting their analgesic benefits. High-quality, well-controlled randomized controlled trials are needed to decipher whether, and to what extent, these agents can be positioned in chronic pain management. Because psychiatrists are likely to encounter patients considering, or receiving, CBM, they must be aware of the potential benefits, risks, and adverse effects of such treatments.

Related Resources

- Joshi KG. Cannabis-derived compounds: what you need to know. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(10):64-65. doi:10.12788/ cp.0050

- Gupta S, Phalen T, Gupta S. Medical marijuana: do the benefits outweigh the risks? Current Psychiatry. 2018; 17(1):34-41.

Drug Brand Names

Ajulemic acid • Anabasum

Alprazolam • Xanax

Amitriptyline • Elavil

Aripiprazole • Abilify, Abilify Maintena

Buspirone • BuSpar

Cannabidiol • Epidiolex

Carbamazepine • Tegretol, Equetro

Cimetidine • Tagamet HB

Citalopram • Celexa

Clopidogrel • Plavix

Clozapine • Clozaril

Cyclosporine • Neoral, Sandimmune

Dronabinol • Marinol, Syndros

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Haloperidol • Haldol

Imipramine • Tofranil

Ketoconazole • Nizoral AD

Losartan • Cozaar

Midazolam • Versed

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Nabilone • Cesamet

Nabiximols • Sativex

Nefazodone • Serzone

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Phenobarbital • Solfoton

Phenytoin • Dilantin

Ramelteon • Rozerem

Rifampin • Rifadin

Risperidone • Risperdal

Sertraline • Zoloft

Tamoxifen • Nolvadex

Topiramate • Topamax

Valproic acid • Depakote, Depakene

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Verapamil • Verelan

Zolpidem • Ambien

1. Okie S. A floor of opioids, a rising tide of deaths. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(21):1981-1985. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1011512

2. Powell D, Pacula RL, Taylor E. How increasing medical access to opioids contributes to the opioid epidemic: evidence from Medicare Part D. J Health Econ. 2020;71:102286. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2019.102286

3. Manzanares J, Julian MD, Carrascosa A. Role of the cannabinoid system in pain control and therapeutic implications for the management of acute and chronic pain episodes. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2006;4(3):239-257. doi: 10.2174/157015906778019527

4. Zou S, Kumar U. Cannabinoid receptors and the endocannabinoid system: signaling and function in the central nervous system. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(3):833. doi: 10.3390/ijms19030833

5. Huang WJ, Chen WW, Zhang X. Endocannabinoid system: role in depression, reward and pain control (Review). Mol Med Rep. 2016;14(4):2899-2903. doi:10.3892/mmr.2016.5585

6. Mechoulam R, Ben-Shabat S, Hanus L, et al. Identification of an endogenous 2-monoglyceride, present in canine gut, that binds to cannabinoid receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;50(1):83-90. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(95)00109-d

7. Walker JM, Krey JF, Chu CJ, et al. Endocannabinoids and related fatty acid derivatives in pain modulation. Chem Phys Lipids. 2002;121(1-2):159-172. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(02)00152-4

8. Howlett AC. Efficacy in CB1 receptor-mediated signal transduction. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142(8):1209-1218. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705881

9. Giuffrida A, Beltramo M, Piomelli D. Mechanisms of endocannabinoid inactivation, biochemistry and pharmacology. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:7-14.

10. Piomelli D, Beltramo M, Giuffrida A, et al. Endogenous cannabinoid signaling. Neurobiol Dis. 1998;5(6 Pt B):462-473. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0221

11. Eggan SM, Lewis DA. Immunocytochemical distribution of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor in the primate neocortex: a regional and laminar analysis. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17(1):175-191. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj136

12. Jennings EA, Vaughan CW, Christie MJ. Cannabinoid actions on rat superficial medullary dorsal horn neurons in vitro. J Physiol. 2001;534(Pt 3):805-812. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00805.x

13. Vaughan CW, Connor M, Bagley EE, et al. Actions of cannabinoids on membrane properties and synaptic transmission in rat periaqueductal gray neurons in vitro. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57(2):288-295.

14. Vaughan CW, McGregor IS, Christie MJ. Cannabinoid receptor activation inhibits GABAergic neurotransmission in rostral ventromedial medulla neurons in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127(4):935-940. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702636

15. Raichlen DA, Foster AD, Gerdeman GI, et al. Wired to run: exercise-induced endocannabinoid signaling in humans and cursorial mammals with implications for the “runner’s high.” J Exp Biol. 2012;215(Pt 8):1331-1336. doi: 10.1242/jeb.063677

16. Beltrano M. Cannabinoid type 2 receptor as a target for chronic pain. Mini Rev Chem. 2009;234:253-254.

17. Ibrahim MM, Deng H, Zvonok A, et al. Activation of CB2 cannabinoid receptors by AM1241 inhibits experimental neuropathic pain: pain inhibition by receptors not present in the CNS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(18):10529-10533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834309100

18. Valenzano KJ, Tafessem L, Lee G, et al. Pharmacological and pharmacokinetic characterization of the cannabinoid receptor 2 agonist, GW405833, utilizing rodent models of acute and chronic pain, anxiety, ataxia and catalepsy. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:658-672.

19. Pertwee RG, Howlett AC, Abood ME, et al. International union of basic and clinical pharmacology. LXXIX. Cannabinoid receptors and their ligands: beyond CB1 and CB2. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62(4):588-631. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003004

20. Carter GT, Weydt P, Kyashna-Tocha M, et al. Medicinal cannabis: rational guidelines for dosing. Drugs. 2004;7(5):464-470.

21. Huestis MA. Human cannabinoid pharmacokinetics. Chem Biodivers. 2007;4(8):1770-1804.

22. Johal H, Devji T, Chang Y, et al. cannabinoids in chronic non-cancer pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;13:1179544120906461. doi: 10.1177/1179544120906461

23. Hillig KW, Mahlberg PG. A chemotaxonomic analysis of cannabinoid variation in Cannabis (Cannabaceae). Am J Bot. 2004;91(6):966-975. doi: 10.3732/ajb.91.6.966

24. Hazekamp A, Ware MA, Muller-Vahl KR, et al. The medicinal use of cannabis and cannabinoids--an international cross-sectional survey on administration forms. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2013;45(3):199-210. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2013.805976

25. Andreae MH, Carter GM, Shaparin N, et al. inhaled cannabis for chronic neuropathic pain: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. J Pain. 2015;16(12):1221-1232. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.07.009

26. Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(24):2456-2473. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6358

27. Boychuk DG, Goddard G, Mauro G, et al. The effectiveness of cannabinoids in the management of chronic nonmalignant neuropathic pain: a systematic review. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2015;29(1):7-14. doi: 10.11607/ofph.1274

28. Lynch ME, Campbell F. Cannabinoids for treatment of chronic non-cancer pain; a systematic review of randomized trials. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;72(5):735-744. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03970.x

29. Stockings E, Campbell G, Hall WD, et al. Cannabis and cannabinoids for the treatment of people with chronic noncancer pain conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled and observational studies. Pain. 2018;159(10):1932-1954. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001293

30. Mücke M, Phillips T, Radbruch L, et al. Cannabis-based medicines for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;3(3):CD012182. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012182.pub2

31. Häuser W, Fitzcharles MA, Radbruch L, et al. Cannabinoids in pain management and palliative medicine. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114(38):627-634. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0627

32. Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9(2):105-121. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005

33. Farrar JT, Troxel AB, Stott C, et al. Validity, reliability, and clinical importance of change in a 0-10 numeric rating scale measure of spasticity: a post hoc analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Ther. 2008;30(5):974-985. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.05.011

34. Moulin D, Boulanger A, Clark AJ, et al. Pharmacological management of chronic neuropathic pain: revised consensus statement from the Canadian Pain Society. Pain Res Manag. 2014;19(6):328-335. doi: 10.1155/2014/754693

35. Petzke F, Enax-Krumova EK, Häuser W. Efficacy, tolerability and safety of cannabinoids for chronic neuropathic pain: a systematic review of randomized controlled studies. Schmerz. 2016;30(1):62-88. doi: 10.1007/s00482-015-0089-y

36. Rice J, Cameron M. Cannabinoids for treatment of MS symptoms: state of the evidence. Curr Neurol Neurosci Rep. 2018;18(8):50. doi: 10.1007/s11910-018-0859-x

37. Koppel BS, Brust JCM, Fife T, et al. Systematic review: efficacy and safety of medical marijuana in selected neurologic disorders. Report of the Guideline Development Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2014;82(17):1556-1563. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000000363

38. Kafil TS, Nguyen TM, MacDonald JK, et al. Cannabis for the treatment of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis: evidence from Cochrane Reviews. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2020;26(4):502-509. doi: 10.1093/ibd/izz233

39. Katz-Talmor D, Katz I, Porat-Katz BS, et al. Cannabinoids for the treatment of rheumatic diseases - where do we stand? Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2018;14(8):488-498. doi: 10.1038/s41584-018-0025-5

40. Walitt B, Klose P, Fitzcharles MA, et al. Cannabinoids for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;7(7):CD011694. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD011694.pub2

41. Bar-Lev Schleider L, Mechoulam R, Lederman V, et al. Prospective analysis of safety and efficacy of medical cannabis in large unselected population of patients with cancer. Eur J Intern Med. 2018;49:37‐43. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2018.01.023

42. Bennett M, Paice JA, Wallace M. Pain and opioids in cancer care: benefits, risks, and alternatives. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:705‐713. doi:10.1200/EDBK_180469

43. Blake A, Wan BA, Malek L, et al. A selective review of medical cannabis in cancer pain management. Ann Palliat Med. 2017;6(Suppl 2):5215-5222. doi: 10.21037/apm.2017.08.05

44. Aviram J, Samuelly-Lechtag G. Efficacy of cannabis-based medicines for pain management: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pain Physician. 2017;20(6):E755-E796.

45. Häuser W, Welsch P, Klose P, et al. Efficacy, tolerability and safety of cannabis-based medicines for cancer pain: a systematic review with meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Schmerz. 2019;33(5):424-436. doi: 10.1007/s00482-019-0373-3

46. Johnson JR, Burnell-Nugent M, Lossignol D, et al. Multicenter, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study of the efficacy, safety, and tolerability of THC:CBD extract and THC extract in patients with intractable cancer-related pain. J Pain Symptom Manage 2010; 39:167-179.

47. Portenoy RK, Ganae-Motan ED, Allende S, et al. Nabiximols for opioid-treated cancer patients with poorly-controlled chronic pain: a randomized, placebo-controlled, graded-dose trial. J Pain. 2012;13(5):438-449. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2012.01.003

48. Lynch ME, Cesar-Rittenberg P, Hohmann AG. A double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover pilot trial with extension using an oral mucosal cannabinoid extract for treatment of chemotherapy-induced neuropathic pain. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;47(1):166-173. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.02.018

49. Kleckner AS, Kleckner IR, Kamen CS, et al. Opportunities for cannabis in supportive care in cancer. Ther Adv Med Oncol. 2019;11:1758835919866362. doi: 10.1177/1758835919866362

50. National Conference of State Legislatures (ncsl.org). State Medical Marijuana Laws. Accessed April 5, 2021. https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/state-medical-marijuana-laws.aspx

51. Hasin DS, Shmulewitz D, Cerda M, et al. US adults with pain, a group increasingly vulnerable to nonmedical cannabis use and cannabis use disorder: 2001-2002 and 2012-2013. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(7):611-618. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2019.19030284

52. Hasin DS, Sarvet AL, Cerdá M, et al. US adult illicit cannabis use, cannabis use disorder, and medical marijuana laws: 1991-1992 to 2012-2013. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74(6):579-588. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0724

53. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Illicit cannabis use and use disorders increase in states with medical marijuana laws. April 26, 2017. Accessed October 24, 2020. https://archives.drugabuse.gov/news-events/news-releases/2017/04/illicit-cannabis-use-use-disorders-increase-in-states-medical-marijuana-laws

54. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. The health effects of cannabis and cannabinoids: the current state of evidence and recommendations for research. The National Academies Press; 2017. https://doi.org/10.17226/24625

55. Stanford M. Physician recommended marijuana: contraindications & standards of care. A review of the literature. Accessed July 7, 2020. http://drneurosci.com/MedicalMarijuanaStandardsofCare.pdf

56. Repp K, Raich A. Marijuana and health: a comprehensive review of 20 years of research. Washington County Oregon Department of Health and Human Services. 2014. Accessed April 8, 2021. https://www.co.washington.or.us/CAO/upload/HHSmarijuana-review.pdf

57. Parmar JR, Forrest BD, Freeman RA. Medical marijuana patient counseling points for health care professionals based on trends in the medical uses, efficacy, and adverse effects of cannabis-based pharmaceutical drugs. Res Social Adm Pharm. 2016;12(4):638-654. doi: 10.1016/j.sapharm.2015.09.002.

58. Leite RT, Nogueira Sde O, do Nascimento JP, et al. The use of cannabis as a predictor of early onset of bipolar disorder and suicide attempts. Neural Plast. 2015;2015:434127. doi: 10.1155/2015/43412

59. Kim SW, Dodd S, Berk L, et al. Impact of cannabis use on long-term remission in bipolar I and schizoaffective disorder. Psychiatry Investig. 2015;12(3):349-355. doi: 10.4306/pi.2015.12.3.349

60. Black N, Stockings E, Campbell G, et al. Cannabinoids for the treatment of mental disorders and symptoms of mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry. 2019;6(12):995-1010.

61. Wilkinson ST, Radhakrishnan R, D’Souza DC. A systematic review of the evidence for medical marijuana in psychiatric indications. J Clin Psychiatry. 2016;77(8):1050-1064. doi: 10.4088/JCP.15r10036.

62. Woolf CJ, American College of Physicians. American Physiological Society Pain: moving from symptom control toward mechanism-specific pharmacologic management. Ann Intern Med. 2004;140(6):441-451.

63. Crippa JA, Zuardi AW, Martín-Santos R, et al. Cannabis and anxiety: a critical review of the evidence. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2009;24(7):515‐523. doi: 10.1002/hup.1048

64. Sachs J, McGlade E, Yurgelun-Todd D. Safety and toxicology of cannabinoids. Neurotherapeutics. 2015;12(4):735‐746. doi: 10.1007/s13311-015-0380-8

65. Antoniou T, Bodkin J, Ho JMW. Drug interactions with cannabinoids. CMAJ. 2020;2;192:E206. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.191097

66. Brown JD. Potential adverse drug events with tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) due to drug-drug interactions. J Clin Med. 2020;9(4):919. doi: 10.3390/jcm9040919.

67. Maida V, Daeninck P. A user’s guide to cannabinoid therapy in oncology. Curr Oncol. 2016;23(6):398-406. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.3747/co.23.3487

68. Stout SM, Cimino NM. Exogenous cannabinoids as substrates, inhibitors, and inducers of human drug metabolizing enzymes: a systematic review. Drug Metab Rev. 2014;46(1):86-95. doi: 10.3109/03602532.2013.849268

69. Abrams DI. Integrating cannabis into clinical cancer care. Curr Oncol. 2016;23(52):S8-S14.

70. Alsherbiny MA, Li CG. Medicinal cannabis—potential drug interactions. Medicines. 2018;6(1):3. doi: 10.3390/medicines6010003

71. Lucas CJ, Galettis P, Schneider J. The pharmacokinetics and the pharmacodynamics of cannabinoids. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2018;84:2477-2482.

72. Ghasemiesfe M, Barrow B, Leonard S, et al. Association between marijuana use and risk of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(11):e1916318. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.16318

73. Riggs PK, Vaida F, Rossi SS, et al. A pilot study of the effects of cannabis on appetite hormones in HIV-infected adult men. Brain Res. 2012;1431:46-52. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.11.001

74. Asbridge M, Hayden JA, Cartwright JL. Acute cannabis consumption and motor vehicle collision risk: systematic review of observational studies and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2012;344:e536. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e536

75. Carlier J, Huestis MA, Zaami S, et al. Monitoring perinatal exposure to cannabis and synthetic cannabinoids. Ther Drug Monit. 2020;42(2):194-204.

Against the backdrop of an increasing opioid use epidemic and a marked acceleration of prescription opioid–related deaths,1,2 there has been an impetus to explore the usefulness of alternative and co-analgesic agents to assist patients with chronic pain. Preclinical studies employing animal-based models of human pain syndromes have demonstrated that cannabis and chemicals derived from cannabis extracts may mitigate several pain conditions.3

Because there are significant comorbidities between psychiatric disorders and chronic pain, psychiatrists are likely to care for patients with chronic pain. As the availability of and interest in cannabinoid-based medications (CBM) increases, psychiatrists will need to be apprised of the utility, adverse effects, and potential drug interactions of these agents.

The endocannabinoid system and cannabis receptors

The endogenous cannabinoid (endocannabinoid) system is abundantly present within the peripheral and central nervous systems. The first identified, and best studied, endocannabinoids are N-arachidonoyl-ethanolamine (AEA; anandamide) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG).4 Unlike typical neurotransmitters, AEA and 2-AG are not stored within vesicles within presynaptic neuron axons. Instead, they are lipophilic molecules produced on demand, synthesized from phospholipids (ie, arachidonic acid derivatives) at the membranes of post-synaptic neurons, and released into the synapse directly.5

Acting as retrograde messengers, the endocannabinoids traverse the synapse, binding to receptors located on the axons of the presynaptic neuron. Two receptors—CB1 and CB2—have been most extensively studied and characterized.6,7 These receptors couple to Gi/o-proteins to inhibit adenylate cyclase, decreasing Ca2+ conductance and increasing K+ conductance.8 Once activated, cannabinoid receptors modulate neurotransmitter release from presynaptic axon terminals. Evidence points to a similar retrograde signaling between neurons and glial cells. Shortly after receptor activation, the endocannabinoids are deactivated by the actions of a transporter mechanism and enzyme degradation.9,10

The endocannabinoid system and pain transmission

Cannabinoid receptors are present in pain transmission circuits spanning from the peripheral sensory nerve endings (from which pain signals originate) to the spinal cord and supraspinal regions within the brain.11-14 CB1 receptors are abundantly present within the CNS, including regions involved in pain transmission. Binding to CB1 receptors, endocannabinoids modulate neurotransmission that impacts pain transmission centrally. Endocannabinoids can also indirectly modulate opiate and N-methyl-

By contrast, CB2 receptors are predominantly localized to peripheral tissues and immune cells, although there has been some discovery of their presence within the CNS (eg, on microglia). Endocannabinoid activation of CB2 receptors is thought to modulate the activity of peripheral afferent pain fibers and immune-mediated neuroinflammatory processes—such as inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis and mast cell degranulation—that can precipitate and maintain chronic pain states.16-18

Evidence garnered from preclinical (animal) studies points to the role of the endocannabinoid system in modulating normal pain transmission (see Manzanares et al3 for details). These studies offer a putative basis for understanding how exogenous cannabinoid congeners might serve to ameliorate pain transmission in pathophysiologic states, including chronic pain.

Continue to: Cannabinoid-based medications

Cannabinoid-based medications

Marijuana contains multiple components (cannabinoids). The most extensively studied are delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). Because it predominantly binds CB1 receptors centrally, THC is the major psychoactive component of cannabis; it promotes sleep and appetite, influences anxiety, and produces the “high” associated with cannabis use. By contrast, CBD weakly binds CB1 and thus exerts minimal or no psychoactive effects.19

Cannabinoid absorption, metabolism, bioavailability, and clinical effects vary depending on the formulation and method of administration (Table 1).20-22 THC and CBD content and potency in inhaled cannabis can vary significantly depending on the strains of the cannabis plant and manner of cultivation.23 To standardize approaches for administering cannabinoids in clinical trials and for clinical use, researchers have developed pharmaceutical analogs that contain extracted chemicals or synthetic chemicals similar to THC and/or CBD.

In this article, CBM refers to smoked/vaporized herbal cannabis as well as pharmaceutical cannabis analogs. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of CBM commonly used in studies investigating their use for managing pain conditions.

CBM for chronic pain

The literature base examining the role of CBM for managing chronic nonmalignant and malignant pain of varying etiologies is rapidly expanding. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have focused on inhaled/smoked products and related cannabinoid medications, some of which are FDA-approved (Table 2).

A multitude of other cannabinoid-based products are currently commercially available to consumers, including tincture and oil-based products; over-the-counter CBD products; and several other formulations of CBM (eg, edible and suppository products). Because such products are not standardized or quality-controlled,24 RCTs have not assessed their efficacy for mitigating pain. Consequently, the findings summarized in this article do not address the utility of these agents.

Continue to: CBM for non-cancer pain

CBM for non-cancer pain

Neuropathic pain. Randomized controlled trials have assessed the pain-mitigating effects of various CBM, including inhaled cannabis, synthetic THC, plant-extracted CBD, and a THC/CBD spray. Studies have shown that inhaled/vaporized cannabis can produce short-term pain reduction in patients with chronic neuropathic pain of diverse etiologies, including diabetes mellitus-, HIV-, trauma-, and medication-induced neuropathies.22,25,26 Similar beneficial effects have been observed with the use of cannabis analogues (eg, nabiximols).25,26-29

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews have determined that most of these RCTs were of low-to-moderate quality.26,30 Meta-analyses have revealed divergent and conflicting results because of differences in the inclusion and exclusion criteria used to select RCTs for analysis and differences in the standards with which the quality of evidence were determined.25,30

Overall, the benefit of CBM for mitigating neuropathic pain is promising, but the effectiveness may not be robust.30,31 Several noteworthy caveats limit the interpretation of the results of these RCTs:

- due to the small sample sizes and brief durations of study, questions remain regarding the extent to which effects are generalizable, whether the benefits are sustained, and whether adverse effects emerge over time with continued use

- most RCTs evaluated inhaled (herbal) cannabis and nabiximols; there is little data on the effectiveness of other CBM formulations25,26,30

- the pain-mitigating effects of CBM were usually compared with those of placebo; the comparative efficacy against agents commonly used to treat neuropathic pain remains largely unexamined

- these RCTs typically compared mean pain severity score differences between cannabis-treated and placebo groups using standard subjective rating scales of pain intensity, such as the Numerical Rating Scale or Visual Analogue Scale. Customarily, the pain literature has used a 30% or 50% reduction in pain severity from baseline as an indicator of significant clinical improvement.32,33 The RCTs of CBM for neuropathic pain rarely used this standard, which makes it unclear whether CBM results in clinically significant pain reductions30

- indirect measures of effectiveness (ie, whether using CBM reduces the need for opioids or other analgesics to manage pain) were seldom reported in these RCTs.

Due to these limitations, clinical guidelines and systematic reviews consider CBM as a third- or fourth-line therapy for patients experiencing chronic neuropathic pain for whom conventional agents such as anticonvulsants and antidepressants have failed.34,35

Spasticity in multiple sclerosis (MS). Several RCTs have assessed the use of CBM for MS-related spasticity, although few were deemed to be high quality. Nabiximols and synthetic THC were effective in managing spasticity and reducing pain severity associated with muscle spasms.36 Generally, investigations revealed that CBM were associated with improvements in subjective measures of spasticity, but these were not born out in clinical, objective measures.26,37 The efficacy of smoked cannabis was uncertain.37 The existing literature on CBM for MS-related spasticity does not address dosing, duration of effects, tolerability, or comparative effectiveness against conventional anti-spasm medications.36,37

Continue to: Other chronic pain conditions

Other chronic pain conditions. CBM have also been studied for their usefulness in several other noncancer chronic conditions, including Crohn’s disease, inflammatory bowel disease, fibromyalgia, and other rheumatologic pain conditions.22,31,38-40 However, a solid foundation of empirical work to inform their utility for managing pain in these conditions is lacking.

CBM for cancer pain

Anecdotal evidence suggests that inhaled cannabis has promising pain-mitigating effects in patients with advanced cancer.41-43 There is a dearth of high-quality RCTs assessing the utility of CBM in patients with cancer pain.43-45 The types of CBM used and dosing strategies varied across RCTs, which makes it difficult to infer how best to treat patients with cancer pain. The agents studied included nabiximols, THC spray, and synthetic THC capsules.43-45 Although some studies have demonstrated that synthetic THC and nabiximols have potential for reducing subjective pain ratings compared with placebo,46,47 these results were inconsistent.46,48 Oromucosal nabiximols did not appear to confer any additional analgesic benefit in patients who were already prescribed opioids.31,45

The benefit of CBM for mitigating cancer pain is promising, but it remains difficult to know how to position the use of CBM in managing cancer pain. Limitations in the cancer literature include:

- the RCTs addressing CBM use for cancer pain were often brief, which raises questions about the long-term effectiveness and adverse effects of these agents

- tolerability and dosing limits encountered due to adverse effects were seldom reported43,45

- the types of cancer pain that patients had were often quite diverse. The small sample sizes and the heterogeneity of conditions included in these RCTs limit the ability to determine whether pain-mitigating effects might vary according to type of cancer-related pain.31,45

Despite these limitations, some clinical guidelines and systematic reviews have suggested that CBM have some role in addressing refractory malignant pain conditions.49

Psychiatric considerations related to CBM

As of November 2020, 36 states had legalized the use of cannabis for medical purposes, typically for painful conditions, despite the fact that empirical evidence to support their efficacy is mixed.50 In light of recent changes in both the legal and popular attitudes regarding cannabis, the implications of legalizing CBM remains to be seen. For example, some research suggests that adults with pain are vulnerable to frequent nonmedical cannabis use and/or cannabis use disorder.51 Although well-intended, the legalization of CBM use might represent society’s next misstep in the quest to address the suffering of patients with chronic pain. Some evidence shows that cannabis use and cannabis use disorders increase in states that have legalized medical marijuana.52,53 Psychiatrists will be on the front lines of addressing any potential consequences arising from the use of CBM for treating pain.

Continue to: Psychiatric disorders and CBM

Psychiatric disorders and CBM. The psychological impact of CBM use among patients enduring chronic pain can include sedation, cognitive/attention disturbance, and fatigue. These adverse effects can limit the utility of such agents.22,29,45

Contraindications for CBM use, and conditions for which CBM ought to be used with caution, are listed in Table 354,55.The safety of CBM, particularly in patients with chronic pain and psychiatric disorders, has not been examined. Patients with psychiatric disorders may be poor candidates for medical cannabis. Epidemiologic data suggest that recreational cannabis use is positively associated both cross-sectionally and prospectively with psychotic spectrum disorders, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms, including panic disorder.56 Psychotic reactions have also been associated with CBM (dronabinol and nabilone).57 Cannabis use also has been associated with an earlier onset of, and lower remission rates of, symptoms associated with bipolar disorder.58,59 Consequently, patients who have been diagnosed with or are at risk for developing any of the aforementioned conditions may not be suitable candidates for CBM. If CBM are used, patients should be closely monitored for the emergence/exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms. The frequency and extent of follow-up is not clear, however. Because of its reduced propensity to produce psychoactive effects, CBD may be safer than THC for managing pain in individuals who have or are vulnerable to developing psychiatric disorders.

There is a lack of evidence to support the use of CBM for treating primary depressive disorders, general anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, or psychosis.60,61 Very low-quality evidence suggests that CBM could lead to a small improvement in anxiety among individuals with noncancer pain and MS.60 However, interpreting causality is complicated. It is plausible that, for some patients, subjective improvement in pain severity may be related to reduced anxiety.62 Conversely, it is equally plausible that reductions in emotional distress may reduce the propensity to attend to, and thus magnify, pain severity. In the latter case, the indirect impact of reducing pain by modifying emotional distress can be impacted by the type and dose of CBM used. For example, low concentrations of THC produce anxiolytic effects, but high concentrations may be anxiety-provoking.63,64

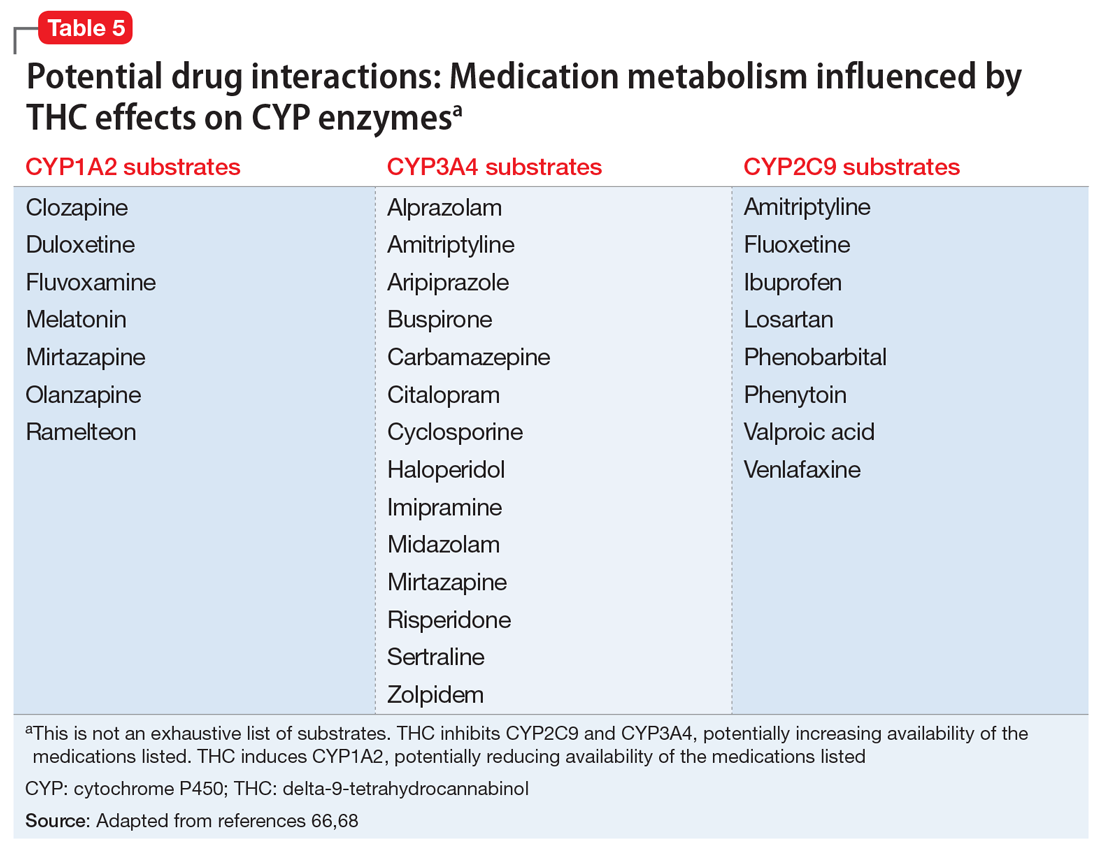

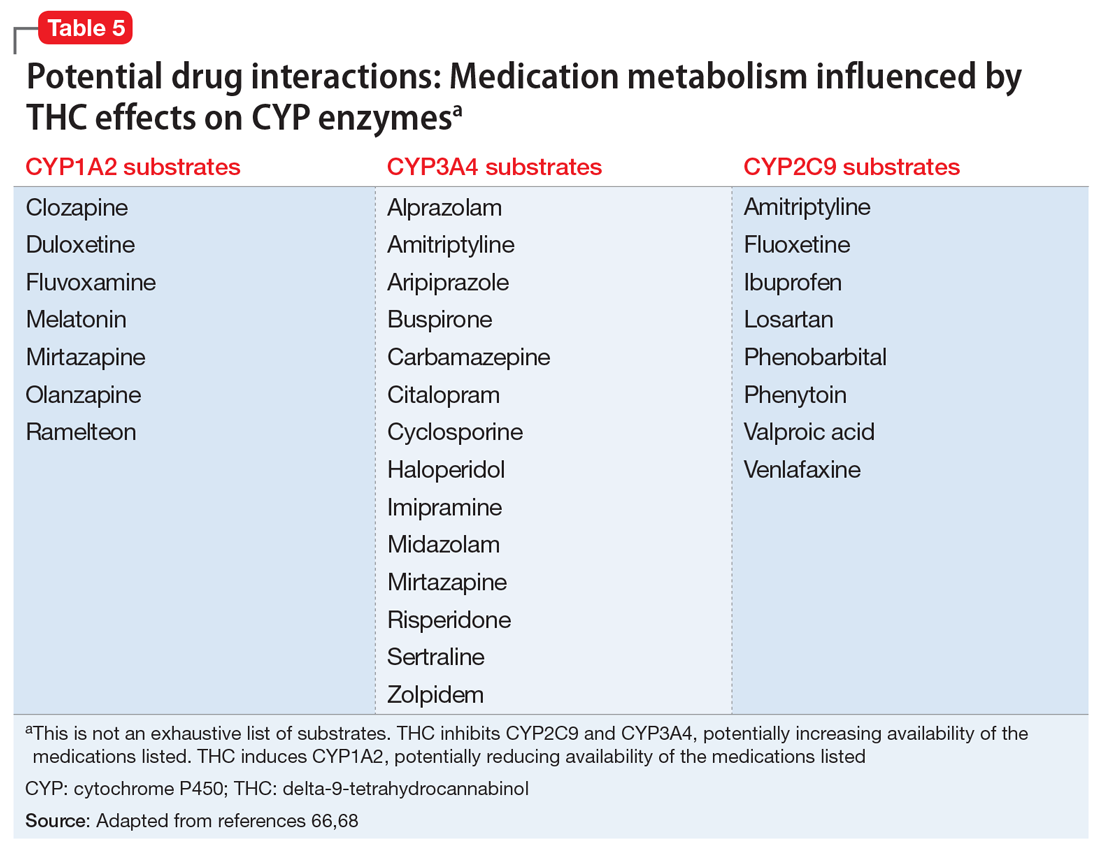

Several potential pharmacokinetic drug interactions may arise between herbal cannabis or CBM and other medications (Table 465,66). THC and CBD are both metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2C19 and 3A4.65,66 In addition, THC is also metabolized by CYP2C9. Medications that inhibit or induce these enzymes can increase or decrease the bioavailability of THC and CBD.67

Simultaneously, cannabinoids can impact the bioavailability of co-prescribed medications (Table 566,68). Although such CYP enzyme interactions remain a theoretical possibility, it is uncertain whether significant perturbations in plasma concentrations (and clinical effects) have been encountered with prescription medications when co-administered with CBM.69 Nonetheless, patients receiving CBM should be closely monitored for their response to prescribed medications.70

Continue to: Potential CYP enzyme interactions...

Potential CYP enzyme interactions aside, clinicians need to consider the additive effects that may occur when CBM are combined with sympathomimetic agents (eg, tachycardia, hypertension); CNS depressants such as alcohol, benzodiazepines, and opioids (eg, drowsiness, ataxia); or anticholinergics (eg, tachycardia, confusion).71 Inhaled herbal cannabis contains mutagens and can result in lung damage, exacerbations of chronic bronchitis, and certain types of cancer.54,72 Co-prescribing benzodiazepines may be contraindicated in light of their effects on respiratory rate and effort.

The THC contained in CBM produces hormonal effects (ie, significantly increases plasma levels of ghrelin and leptin and decreases peptide YY levels)73 that affect appetite and can produce weight gain. This may be problematic for patients receiving psychoactive medications associated with increased risk of weight gain and dyslipidemia. Because of the association between cannabis use and motor vehicle accidents, patients whose jobs require them to drive or operate industrial equipment may not be ideal candidates for CBM, especially if such patients also consume alcohol or are prescribed benzodiazepines and/or sedative hypnotics.74 Lastly, due to their lipophilicity, cannabinoids cross the placental barrier and can be found in breast milk75 and therefore can affect pregnancy outcomes and neurodevelopment.

Bottom Line

The popularity of cannabinoid-based medications (CBM) for the treatment of chronic pain conditions is growing, but the interest in their use may be outpacing the evidence supporting their analgesic benefits. High-quality, well-controlled randomized controlled trials are needed to decipher whether, and to what extent, these agents can be positioned in chronic pain management. Because psychiatrists are likely to encounter patients considering, or receiving, CBM, they must be aware of the potential benefits, risks, and adverse effects of such treatments.

Related Resources

- Joshi KG. Cannabis-derived compounds: what you need to know. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(10):64-65. doi:10.12788/ cp.0050

- Gupta S, Phalen T, Gupta S. Medical marijuana: do the benefits outweigh the risks? Current Psychiatry. 2018; 17(1):34-41.

Drug Brand Names

Ajulemic acid • Anabasum

Alprazolam • Xanax

Amitriptyline • Elavil

Aripiprazole • Abilify, Abilify Maintena

Buspirone • BuSpar

Cannabidiol • Epidiolex

Carbamazepine • Tegretol, Equetro

Cimetidine • Tagamet HB

Citalopram • Celexa

Clopidogrel • Plavix

Clozapine • Clozaril

Cyclosporine • Neoral, Sandimmune

Dronabinol • Marinol, Syndros

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Haloperidol • Haldol

Imipramine • Tofranil

Ketoconazole • Nizoral AD

Losartan • Cozaar

Midazolam • Versed

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Nabilone • Cesamet

Nabiximols • Sativex

Nefazodone • Serzone

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Phenobarbital • Solfoton

Phenytoin • Dilantin

Ramelteon • Rozerem

Rifampin • Rifadin

Risperidone • Risperdal

Sertraline • Zoloft

Tamoxifen • Nolvadex

Topiramate • Topamax

Valproic acid • Depakote, Depakene

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Verapamil • Verelan

Zolpidem • Ambien

Against the backdrop of an increasing opioid use epidemic and a marked acceleration of prescription opioid–related deaths,1,2 there has been an impetus to explore the usefulness of alternative and co-analgesic agents to assist patients with chronic pain. Preclinical studies employing animal-based models of human pain syndromes have demonstrated that cannabis and chemicals derived from cannabis extracts may mitigate several pain conditions.3

Because there are significant comorbidities between psychiatric disorders and chronic pain, psychiatrists are likely to care for patients with chronic pain. As the availability of and interest in cannabinoid-based medications (CBM) increases, psychiatrists will need to be apprised of the utility, adverse effects, and potential drug interactions of these agents.

The endocannabinoid system and cannabis receptors

The endogenous cannabinoid (endocannabinoid) system is abundantly present within the peripheral and central nervous systems. The first identified, and best studied, endocannabinoids are N-arachidonoyl-ethanolamine (AEA; anandamide) and 2-arachidonoylglycerol (2-AG).4 Unlike typical neurotransmitters, AEA and 2-AG are not stored within vesicles within presynaptic neuron axons. Instead, they are lipophilic molecules produced on demand, synthesized from phospholipids (ie, arachidonic acid derivatives) at the membranes of post-synaptic neurons, and released into the synapse directly.5

Acting as retrograde messengers, the endocannabinoids traverse the synapse, binding to receptors located on the axons of the presynaptic neuron. Two receptors—CB1 and CB2—have been most extensively studied and characterized.6,7 These receptors couple to Gi/o-proteins to inhibit adenylate cyclase, decreasing Ca2+ conductance and increasing K+ conductance.8 Once activated, cannabinoid receptors modulate neurotransmitter release from presynaptic axon terminals. Evidence points to a similar retrograde signaling between neurons and glial cells. Shortly after receptor activation, the endocannabinoids are deactivated by the actions of a transporter mechanism and enzyme degradation.9,10

The endocannabinoid system and pain transmission

Cannabinoid receptors are present in pain transmission circuits spanning from the peripheral sensory nerve endings (from which pain signals originate) to the spinal cord and supraspinal regions within the brain.11-14 CB1 receptors are abundantly present within the CNS, including regions involved in pain transmission. Binding to CB1 receptors, endocannabinoids modulate neurotransmission that impacts pain transmission centrally. Endocannabinoids can also indirectly modulate opiate and N-methyl-

By contrast, CB2 receptors are predominantly localized to peripheral tissues and immune cells, although there has been some discovery of their presence within the CNS (eg, on microglia). Endocannabinoid activation of CB2 receptors is thought to modulate the activity of peripheral afferent pain fibers and immune-mediated neuroinflammatory processes—such as inhibition of prostaglandin synthesis and mast cell degranulation—that can precipitate and maintain chronic pain states.16-18

Evidence garnered from preclinical (animal) studies points to the role of the endocannabinoid system in modulating normal pain transmission (see Manzanares et al3 for details). These studies offer a putative basis for understanding how exogenous cannabinoid congeners might serve to ameliorate pain transmission in pathophysiologic states, including chronic pain.

Continue to: Cannabinoid-based medications

Cannabinoid-based medications

Marijuana contains multiple components (cannabinoids). The most extensively studied are delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) and cannabidiol (CBD). Because it predominantly binds CB1 receptors centrally, THC is the major psychoactive component of cannabis; it promotes sleep and appetite, influences anxiety, and produces the “high” associated with cannabis use. By contrast, CBD weakly binds CB1 and thus exerts minimal or no psychoactive effects.19

Cannabinoid absorption, metabolism, bioavailability, and clinical effects vary depending on the formulation and method of administration (Table 1).20-22 THC and CBD content and potency in inhaled cannabis can vary significantly depending on the strains of the cannabis plant and manner of cultivation.23 To standardize approaches for administering cannabinoids in clinical trials and for clinical use, researchers have developed pharmaceutical analogs that contain extracted chemicals or synthetic chemicals similar to THC and/or CBD.

In this article, CBM refers to smoked/vaporized herbal cannabis as well as pharmaceutical cannabis analogs. Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of CBM commonly used in studies investigating their use for managing pain conditions.

CBM for chronic pain

The literature base examining the role of CBM for managing chronic nonmalignant and malignant pain of varying etiologies is rapidly expanding. Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have focused on inhaled/smoked products and related cannabinoid medications, some of which are FDA-approved (Table 2).

A multitude of other cannabinoid-based products are currently commercially available to consumers, including tincture and oil-based products; over-the-counter CBD products; and several other formulations of CBM (eg, edible and suppository products). Because such products are not standardized or quality-controlled,24 RCTs have not assessed their efficacy for mitigating pain. Consequently, the findings summarized in this article do not address the utility of these agents.

Continue to: CBM for non-cancer pain

CBM for non-cancer pain

Neuropathic pain. Randomized controlled trials have assessed the pain-mitigating effects of various CBM, including inhaled cannabis, synthetic THC, plant-extracted CBD, and a THC/CBD spray. Studies have shown that inhaled/vaporized cannabis can produce short-term pain reduction in patients with chronic neuropathic pain of diverse etiologies, including diabetes mellitus-, HIV-, trauma-, and medication-induced neuropathies.22,25,26 Similar beneficial effects have been observed with the use of cannabis analogues (eg, nabiximols).25,26-29

Meta-analyses and systematic reviews have determined that most of these RCTs were of low-to-moderate quality.26,30 Meta-analyses have revealed divergent and conflicting results because of differences in the inclusion and exclusion criteria used to select RCTs for analysis and differences in the standards with which the quality of evidence were determined.25,30

Overall, the benefit of CBM for mitigating neuropathic pain is promising, but the effectiveness may not be robust.30,31 Several noteworthy caveats limit the interpretation of the results of these RCTs:

- due to the small sample sizes and brief durations of study, questions remain regarding the extent to which effects are generalizable, whether the benefits are sustained, and whether adverse effects emerge over time with continued use

- most RCTs evaluated inhaled (herbal) cannabis and nabiximols; there is little data on the effectiveness of other CBM formulations25,26,30

- the pain-mitigating effects of CBM were usually compared with those of placebo; the comparative efficacy against agents commonly used to treat neuropathic pain remains largely unexamined

- these RCTs typically compared mean pain severity score differences between cannabis-treated and placebo groups using standard subjective rating scales of pain intensity, such as the Numerical Rating Scale or Visual Analogue Scale. Customarily, the pain literature has used a 30% or 50% reduction in pain severity from baseline as an indicator of significant clinical improvement.32,33 The RCTs of CBM for neuropathic pain rarely used this standard, which makes it unclear whether CBM results in clinically significant pain reductions30

- indirect measures of effectiveness (ie, whether using CBM reduces the need for opioids or other analgesics to manage pain) were seldom reported in these RCTs.

Due to these limitations, clinical guidelines and systematic reviews consider CBM as a third- or fourth-line therapy for patients experiencing chronic neuropathic pain for whom conventional agents such as anticonvulsants and antidepressants have failed.34,35

Spasticity in multiple sclerosis (MS). Several RCTs have assessed the use of CBM for MS-related spasticity, although few were deemed to be high quality. Nabiximols and synthetic THC were effective in managing spasticity and reducing pain severity associated with muscle spasms.36 Generally, investigations revealed that CBM were associated with improvements in subjective measures of spasticity, but these were not born out in clinical, objective measures.26,37 The efficacy of smoked cannabis was uncertain.37 The existing literature on CBM for MS-related spasticity does not address dosing, duration of effects, tolerability, or comparative effectiveness against conventional anti-spasm medications.36,37

Continue to: Other chronic pain conditions

Other chronic pain conditions. CBM have also been studied for their usefulness in several other noncancer chronic conditions, including Crohn’s disease, inflammatory bowel disease, fibromyalgia, and other rheumatologic pain conditions.22,31,38-40 However, a solid foundation of empirical work to inform their utility for managing pain in these conditions is lacking.

CBM for cancer pain

Anecdotal evidence suggests that inhaled cannabis has promising pain-mitigating effects in patients with advanced cancer.41-43 There is a dearth of high-quality RCTs assessing the utility of CBM in patients with cancer pain.43-45 The types of CBM used and dosing strategies varied across RCTs, which makes it difficult to infer how best to treat patients with cancer pain. The agents studied included nabiximols, THC spray, and synthetic THC capsules.43-45 Although some studies have demonstrated that synthetic THC and nabiximols have potential for reducing subjective pain ratings compared with placebo,46,47 these results were inconsistent.46,48 Oromucosal nabiximols did not appear to confer any additional analgesic benefit in patients who were already prescribed opioids.31,45

The benefit of CBM for mitigating cancer pain is promising, but it remains difficult to know how to position the use of CBM in managing cancer pain. Limitations in the cancer literature include:

- the RCTs addressing CBM use for cancer pain were often brief, which raises questions about the long-term effectiveness and adverse effects of these agents

- tolerability and dosing limits encountered due to adverse effects were seldom reported43,45

- the types of cancer pain that patients had were often quite diverse. The small sample sizes and the heterogeneity of conditions included in these RCTs limit the ability to determine whether pain-mitigating effects might vary according to type of cancer-related pain.31,45

Despite these limitations, some clinical guidelines and systematic reviews have suggested that CBM have some role in addressing refractory malignant pain conditions.49

Psychiatric considerations related to CBM

As of November 2020, 36 states had legalized the use of cannabis for medical purposes, typically for painful conditions, despite the fact that empirical evidence to support their efficacy is mixed.50 In light of recent changes in both the legal and popular attitudes regarding cannabis, the implications of legalizing CBM remains to be seen. For example, some research suggests that adults with pain are vulnerable to frequent nonmedical cannabis use and/or cannabis use disorder.51 Although well-intended, the legalization of CBM use might represent society’s next misstep in the quest to address the suffering of patients with chronic pain. Some evidence shows that cannabis use and cannabis use disorders increase in states that have legalized medical marijuana.52,53 Psychiatrists will be on the front lines of addressing any potential consequences arising from the use of CBM for treating pain.

Continue to: Psychiatric disorders and CBM

Psychiatric disorders and CBM. The psychological impact of CBM use among patients enduring chronic pain can include sedation, cognitive/attention disturbance, and fatigue. These adverse effects can limit the utility of such agents.22,29,45

Contraindications for CBM use, and conditions for which CBM ought to be used with caution, are listed in Table 354,55.The safety of CBM, particularly in patients with chronic pain and psychiatric disorders, has not been examined. Patients with psychiatric disorders may be poor candidates for medical cannabis. Epidemiologic data suggest that recreational cannabis use is positively associated both cross-sectionally and prospectively with psychotic spectrum disorders, depressive symptoms, and anxiety symptoms, including panic disorder.56 Psychotic reactions have also been associated with CBM (dronabinol and nabilone).57 Cannabis use also has been associated with an earlier onset of, and lower remission rates of, symptoms associated with bipolar disorder.58,59 Consequently, patients who have been diagnosed with or are at risk for developing any of the aforementioned conditions may not be suitable candidates for CBM. If CBM are used, patients should be closely monitored for the emergence/exacerbation of psychiatric symptoms. The frequency and extent of follow-up is not clear, however. Because of its reduced propensity to produce psychoactive effects, CBD may be safer than THC for managing pain in individuals who have or are vulnerable to developing psychiatric disorders.

There is a lack of evidence to support the use of CBM for treating primary depressive disorders, general anxiety disorder, posttraumatic stress disorder, or psychosis.60,61 Very low-quality evidence suggests that CBM could lead to a small improvement in anxiety among individuals with noncancer pain and MS.60 However, interpreting causality is complicated. It is plausible that, for some patients, subjective improvement in pain severity may be related to reduced anxiety.62 Conversely, it is equally plausible that reductions in emotional distress may reduce the propensity to attend to, and thus magnify, pain severity. In the latter case, the indirect impact of reducing pain by modifying emotional distress can be impacted by the type and dose of CBM used. For example, low concentrations of THC produce anxiolytic effects, but high concentrations may be anxiety-provoking.63,64

Several potential pharmacokinetic drug interactions may arise between herbal cannabis or CBM and other medications (Table 465,66). THC and CBD are both metabolized by cytochrome P450 (CYP) 2C19 and 3A4.65,66 In addition, THC is also metabolized by CYP2C9. Medications that inhibit or induce these enzymes can increase or decrease the bioavailability of THC and CBD.67

Simultaneously, cannabinoids can impact the bioavailability of co-prescribed medications (Table 566,68). Although such CYP enzyme interactions remain a theoretical possibility, it is uncertain whether significant perturbations in plasma concentrations (and clinical effects) have been encountered with prescription medications when co-administered with CBM.69 Nonetheless, patients receiving CBM should be closely monitored for their response to prescribed medications.70

Continue to: Potential CYP enzyme interactions...

Potential CYP enzyme interactions aside, clinicians need to consider the additive effects that may occur when CBM are combined with sympathomimetic agents (eg, tachycardia, hypertension); CNS depressants such as alcohol, benzodiazepines, and opioids (eg, drowsiness, ataxia); or anticholinergics (eg, tachycardia, confusion).71 Inhaled herbal cannabis contains mutagens and can result in lung damage, exacerbations of chronic bronchitis, and certain types of cancer.54,72 Co-prescribing benzodiazepines may be contraindicated in light of their effects on respiratory rate and effort.

The THC contained in CBM produces hormonal effects (ie, significantly increases plasma levels of ghrelin and leptin and decreases peptide YY levels)73 that affect appetite and can produce weight gain. This may be problematic for patients receiving psychoactive medications associated with increased risk of weight gain and dyslipidemia. Because of the association between cannabis use and motor vehicle accidents, patients whose jobs require them to drive or operate industrial equipment may not be ideal candidates for CBM, especially if such patients also consume alcohol or are prescribed benzodiazepines and/or sedative hypnotics.74 Lastly, due to their lipophilicity, cannabinoids cross the placental barrier and can be found in breast milk75 and therefore can affect pregnancy outcomes and neurodevelopment.

Bottom Line

The popularity of cannabinoid-based medications (CBM) for the treatment of chronic pain conditions is growing, but the interest in their use may be outpacing the evidence supporting their analgesic benefits. High-quality, well-controlled randomized controlled trials are needed to decipher whether, and to what extent, these agents can be positioned in chronic pain management. Because psychiatrists are likely to encounter patients considering, or receiving, CBM, they must be aware of the potential benefits, risks, and adverse effects of such treatments.

Related Resources

- Joshi KG. Cannabis-derived compounds: what you need to know. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(10):64-65. doi:10.12788/ cp.0050

- Gupta S, Phalen T, Gupta S. Medical marijuana: do the benefits outweigh the risks? Current Psychiatry. 2018; 17(1):34-41.

Drug Brand Names

Ajulemic acid • Anabasum

Alprazolam • Xanax

Amitriptyline • Elavil

Aripiprazole • Abilify, Abilify Maintena

Buspirone • BuSpar

Cannabidiol • Epidiolex

Carbamazepine • Tegretol, Equetro

Cimetidine • Tagamet HB

Citalopram • Celexa

Clopidogrel • Plavix

Clozapine • Clozaril

Cyclosporine • Neoral, Sandimmune

Dronabinol • Marinol, Syndros

Duloxetine • Cymbalta

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Haloperidol • Haldol

Imipramine • Tofranil

Ketoconazole • Nizoral AD

Losartan • Cozaar

Midazolam • Versed

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Nabilone • Cesamet

Nabiximols • Sativex

Nefazodone • Serzone

Olanzapine • Zyprexa

Phenobarbital • Solfoton

Phenytoin • Dilantin

Ramelteon • Rozerem

Rifampin • Rifadin

Risperidone • Risperdal

Sertraline • Zoloft

Tamoxifen • Nolvadex

Topiramate • Topamax

Valproic acid • Depakote, Depakene

Venlafaxine • Effexor

Verapamil • Verelan

Zolpidem • Ambien

1. Okie S. A floor of opioids, a rising tide of deaths. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(21):1981-1985. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1011512

2. Powell D, Pacula RL, Taylor E. How increasing medical access to opioids contributes to the opioid epidemic: evidence from Medicare Part D. J Health Econ. 2020;71:102286. doi: 10.1016/j.jhealeco.2019.102286

3. Manzanares J, Julian MD, Carrascosa A. Role of the cannabinoid system in pain control and therapeutic implications for the management of acute and chronic pain episodes. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2006;4(3):239-257. doi: 10.2174/157015906778019527

4. Zou S, Kumar U. Cannabinoid receptors and the endocannabinoid system: signaling and function in the central nervous system. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(3):833. doi: 10.3390/ijms19030833

5. Huang WJ, Chen WW, Zhang X. Endocannabinoid system: role in depression, reward and pain control (Review). Mol Med Rep. 2016;14(4):2899-2903. doi:10.3892/mmr.2016.5585

6. Mechoulam R, Ben-Shabat S, Hanus L, et al. Identification of an endogenous 2-monoglyceride, present in canine gut, that binds to cannabinoid receptors. Biochem Pharmacol. 1995;50(1):83-90. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(95)00109-d

7. Walker JM, Krey JF, Chu CJ, et al. Endocannabinoids and related fatty acid derivatives in pain modulation. Chem Phys Lipids. 2002;121(1-2):159-172. doi: 10.1016/s0009-3084(02)00152-4

8. Howlett AC. Efficacy in CB1 receptor-mediated signal transduction. Br J Pharmacol. 2004;142(8):1209-1218. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0705881

9. Giuffrida A, Beltramo M, Piomelli D. Mechanisms of endocannabinoid inactivation, biochemistry and pharmacology. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2001;298:7-14.

10. Piomelli D, Beltramo M, Giuffrida A, et al. Endogenous cannabinoid signaling. Neurobiol Dis. 1998;5(6 Pt B):462-473. doi: 10.1006/nbdi.1998.0221

11. Eggan SM, Lewis DA. Immunocytochemical distribution of the cannabinoid CB1 receptor in the primate neocortex: a regional and laminar analysis. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17(1):175-191. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhj136

12. Jennings EA, Vaughan CW, Christie MJ. Cannabinoid actions on rat superficial medullary dorsal horn neurons in vitro. J Physiol. 2001;534(Pt 3):805-812. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.00805.x

13. Vaughan CW, Connor M, Bagley EE, et al. Actions of cannabinoids on membrane properties and synaptic transmission in rat periaqueductal gray neurons in vitro. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;57(2):288-295.

14. Vaughan CW, McGregor IS, Christie MJ. Cannabinoid receptor activation inhibits GABAergic neurotransmission in rostral ventromedial medulla neurons in vitro. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;127(4):935-940. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702636

15. Raichlen DA, Foster AD, Gerdeman GI, et al. Wired to run: exercise-induced endocannabinoid signaling in humans and cursorial mammals with implications for the “runner’s high.” J Exp Biol. 2012;215(Pt 8):1331-1336. doi: 10.1242/jeb.063677

16. Beltrano M. Cannabinoid type 2 receptor as a target for chronic pain. Mini Rev Chem. 2009;234:253-254.

17. Ibrahim MM, Deng H, Zvonok A, et al. Activation of CB2 cannabinoid receptors by AM1241 inhibits experimental neuropathic pain: pain inhibition by receptors not present in the CNS. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(18):10529-10533. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1834309100

18. Valenzano KJ, Tafessem L, Lee G, et al. Pharmacological and pharmacokinetic characterization of the cannabinoid receptor 2 agonist, GW405833, utilizing rodent models of acute and chronic pain, anxiety, ataxia and catalepsy. Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:658-672.

19. Pertwee RG, Howlett AC, Abood ME, et al. International union of basic and clinical pharmacology. LXXIX. Cannabinoid receptors and their ligands: beyond CB1 and CB2. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62(4):588-631. doi: 10.1124/pr.110.003004

20. Carter GT, Weydt P, Kyashna-Tocha M, et al. Medicinal cannabis: rational guidelines for dosing. Drugs. 2004;7(5):464-470.

21. Huestis MA. Human cannabinoid pharmacokinetics. Chem Biodivers. 2007;4(8):1770-1804.

22. Johal H, Devji T, Chang Y, et al. cannabinoids in chronic non-cancer pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Med Insights Arthritis Musculoskelet Disord. 2020;13:1179544120906461. doi: 10.1177/1179544120906461

23. Hillig KW, Mahlberg PG. A chemotaxonomic analysis of cannabinoid variation in Cannabis (Cannabaceae). Am J Bot. 2004;91(6):966-975. doi: 10.3732/ajb.91.6.966

24. Hazekamp A, Ware MA, Muller-Vahl KR, et al. The medicinal use of cannabis and cannabinoids--an international cross-sectional survey on administration forms. J Psychoactive Drugs. 2013;45(3):199-210. doi: 10.1080/02791072.2013.805976

25. Andreae MH, Carter GM, Shaparin N, et al. inhaled cannabis for chronic neuropathic pain: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. J Pain. 2015;16(12):1221-1232. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2015.07.009

26. Whiting PF, Wolff RF, Deshpande S, et al. Cannabinoids for medical use: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(24):2456-2473. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.6358

27. Boychuk DG, Goddard G, Mauro G, et al. The effectiveness of cannabinoids in the management of chronic nonmalignant neuropathic pain: a systematic review. J Oral Facial Pain Headache. 2015;29(1):7-14. doi: 10.11607/ofph.1274

28. Lynch ME, Campbell F. Cannabinoids for treatment of chronic non-cancer pain; a systematic review of randomized trials. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2011;72(5):735-744. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2011.03970.x

29. Stockings E, Campbell G, Hall WD, et al. Cannabis and cannabinoids for the treatment of people with chronic noncancer pain conditions: a systematic review and meta-analysis of controlled and observational studies. Pain. 2018;159(10):1932-1954. doi: 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000001293

30. Mücke M, Phillips T, Radbruch L, et al. Cannabis-based medicines for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;3(3):CD012182. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD012182.pub2

31. Häuser W, Fitzcharles MA, Radbruch L, et al. Cannabinoids in pain management and palliative medicine. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2017;114(38):627-634. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2017.0627

32. Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9(2):105-121. doi: 10.1016/j.jpain.2007.09.005

33. Farrar JT, Troxel AB, Stott C, et al. Validity, reliability, and clinical importance of change in a 0-10 numeric rating scale measure of spasticity: a post hoc analysis of a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Clin Ther. 2008;30(5):974-985. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2008.05.011

34. Moulin D, Boulanger A, Clark AJ, et al. Pharmacological management of chronic neuropathic pain: revised consensus statement from the Canadian Pain Society. Pain Res Manag. 2014;19(6):328-335. doi: 10.1155/2014/754693

35. Petzke F, Enax-Krumova EK, Häuser W. Efficacy, tolerability and safety of cannabinoids for chronic neuropathic pain: a systematic review of randomized controlled studies. Schmerz. 2016;30(1):62-88. doi: 10.1007/s00482-015-0089-y