User login

Limitations of Using Pediatric Respiratory Illness Readmissions to Compare Hospital Performance

Respiratory illnesses are the leading causes of pediatric hospitalizations in the United States.1 The 30-day hospital readmission rate for respiratory illnesses is being considered for implementation as a national hospital performance measure, as it may be an indicator of lower quality care (eg, poor hospital management of disease, inadequate patient/caretaker education prior to discharge). In adult populations, readmissions can be used to reliably identify variation in hospital performance and successfully drive efforts to improve the value of care.2, 3 In contrast, there are persistent concerns about using pediatric readmissions to identify variation in hospital performance, largely due to lower patient volumes.4-7 To increase the value of pediatric hospital care, it is important to develop ways to meaningfully measure quality of care and further, to better understand the relationship between measures of quality and healthcare costs.

In December 2016, the National Quality Forum (NQF) endorsed a Pediatric Lower Respiratory Infection (LRI) Readmission Measure.8 This measure was developed by the Pediatric Quality Measurement Program, through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The goal of this program was to “increase the portfolio of evidence-based, consensus pediatric quality measures available to public and private purchasers of children’s healthcare services, providers, and consumers.”9

In anticipation of the national implementation of pediatric readmission measures, we examined whether the Pediatric LRI Readmission Measure could meaningfully identify high and low performers across all types of hospitals admitting children (general hospitals and children’s hospitals) using an all-payer claims database. A recent analysis by Nakamura et al. identified high and low performers using this measure10 but limited the analysis to hospitals with >50 pediatric LRI admissions per year, an approach that excludes many general hospitals. Since general hospitals provide the majority of care for children hospitalized with respiratory infections,11 we aimed to evaluate the measure in a broadly inclusive analysis that included all hospital types. Because low patient volumes might limit use of the measure,4,6 we tested several broadened variations of the measure. We also examined the relationship between hospital performance in pediatric LRI readmissions and healthcare costs.

Our analysis is intended to inform utilizers of pediatric quality metrics and policy makers about the feasibility of using these metrics to publicly report hospital performance and/or identify exceptional hospitals for understanding best practices in pediatric inpatient care.12

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

We conducted an observational, retrospective cohort analysis using the 2012-2014 California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) nonpublic inpatient and emergency department databases.13 The OSHPD databases are compiled annually through mandatory reporting by all licensed nonfederal hospitals in California. The databases contain demographic (eg, age, gender) and utilization data (eg, charges) and can track readmissions to hospitals other than the index hospital. The databases capture administrative claims from approximately 450 hospitals, composed of 16 million inpatients, emergency department patients, and ambulatory surgery patients annually. Data quality is monitored through the California OSHPD.

Study Population

Our study included children aged ≤18 years with LRI, defined using the NQF Pediatric LRI Readmissions Measure: a primary diagnosis of bronchiolitis, influenza, or pneumonia, or a secondary diagnosis of bronchiolitis, influenza, or pneumonia, with a primary diagnosis of asthma, respiratory failure, sepsis, or bacteremia.8 International classification of Diseases, 9th edition (ICD-9) diagnostic codes used are in Appendix 1.

Per the NQF measure specifications,8 records were excluded if they were from hospitals with <80% of records complete with core elements (unique patient identifier, admission date, end-of-service date, and ICD-9 primary diagnosis code). In addition, records were excluded for the following reasons: (1) individual record missing core elements, (2) discharge disposition “death,” (3) 30-day follow-up data not available, (4) primary “newborn” or mental health diagnosis, or (5) primary ICD-9 procedure code for a planned procedure or chemotherapy.

Patient characteristics for hospital admissions with and without 30-day readmissions or 30-day emergency department (ED) revisits were summarized. For the continuous variable age, mean and standard deviation for each group were calculated. For categorical variables (sex, race, payer, and number of chronic conditions), numbers and proportions were determined. Univariate tests of comparison were carried out using the Student’s t test for age and chi-square tests for all categorical variables. Categories of payer with small values were combined for ease of description (categories combined into “other:” workers’ compensation, county indigent programs, other government, other indigent, self-pay, other payer). We identified chronic conditions using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Chronic Condition Indicator (CCI) system, which classifies ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes as chronic or acute and places each code into 1 of 18 mutually exclusive categories (organ systems, disease categories, or other categories). The case-mix adjustment model incorporates a binary variable for each CCI category (0-1, 2, 3, or >4 chronic conditions) per the NQF measure specifications.8 This study was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was the hospital-level rate of 30-day readmission after hospital discharge, consistent with the NQF measure.8 We identified outlier hospitals for 30-day readmission rate using the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) methodology, which defines outlier hospitals as those for whom adjusted readmission rate confidence intervals do not overlap with the overall group mean rate.5, 14

We also determined the hospital-level average cost per index hospitalization (not including costs of readmissions). Since costs of care often differ substantially from charges,15 costs were calculated using cost-to-charge ratios for each hospital (annual total operating expenses/total gross patient revenue, as reported to the OSHPD).16 Costs were subdivided into categories representing $5,000 increments and a top category of >$40,000. Outlier hospitals for costs were defined as those for whom the cost random effect was either greater than the third quartile of the distribution of values by more than 1.5 times the interquartile range or less than the first quartile of the distribution of values by more than 1.5 times the interquartile range.17

ANALYSIS

Primary Analysis

For our primary analysis of 30-day hospital readmission rates, we used hierarchical logistic regression models with hospitals as random effects, adjusting for patient age, sex, and the presence and number of body systems affected by chronic conditions.8 These 4 patient characteristics were selected by the NQF measure developers “because distributions of these characteristics vary across hospitals, and although they are associated with readmission risk, they are independent of hospital quality of care.”10

Because the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) are in the process of selecting pediatric quality measures for meaningful use reporting,18 we utilized CMS hospital readmissions methodology to calculate risk-adjusted rates and identify outlier hospitals. The CMS modeling strategy stabilizes performance estimates for low-volume hospitals and avoids penalizing these hospitals for high readmission rates that may be due to chance (random effects logistic model to obtain best linear unbiased predictions). This is particularly important in pediatrics, given the low pediatric volumes in many hospitals admitting children.4,19 We then identified outlier hospitals for the 30-day readmission rate using CMS methodology (hospital’s adjusted readmission rate confidence interval does not overlap the overall group mean rate).5, 4 CMS uses this approach for public reporting on HospitalCompare.20

Sensitivity Analyses

We tested several broadening variations of the NQF measure: (1) addition of children admitted with a primary diagnosis of asthma (without requiring LRI as a secondary diagnosis) or a secondary diagnosis of asthma exacerbation (LRIA), (2) inclusion of 30-day ED revisits as an outcome, and (3) merging of 3 years of data. These analyses were all performed using the same modeling strategy as in our primary analysis.

Secondary Outcome Analyses

Our analysis of hospital costs used costs for index admissions over 3 years (2012–2014) and included admissions for asthma. We used hierarchical regression models with hospitals as random effects, adjusting for age, gender, and the presence and number of chronic conditions. The distribution of cost values was highly skewed, so ordinal models were selected after several other modeling approaches failed (log transformation linear model, gamma model, Poisson model, zero-truncated Poisson model).

The relationship between hospital-level costs and hospital-level 30-day readmission or ED revisit rates was analyzed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute; Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Primary Analysis of 30-day Readmissions (per National Quality Forum Measure)

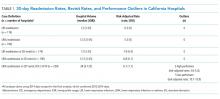

Our analysis of the 2014 OSHPD database using the specifications of the NQF Pediatric LRI Readmission Measure included a total of 5550 hospitalizations from 174 hospitals, with a mean of 12 eligible hospitalizations per hospital. The mean risk-adjusted readmission rate was 6.5% (362 readmissions). There were no hospitals that were considered outliers based on the risk-adjusted readmission rates (Table 1).

Sensitivity Analyses (Broadening Definitions of National Quality Forum Measure)

We report our testing of the broadened variations of the NQF measure in Table 1. Broadening the population to include children with asthma as a primary diagnosis and children with asthma exacerbations as a secondary diagnosis (LRIA) increased the size of our analysis to 8402 hospitalizations from 190 hospitals. The mean risk-adjusted readmission rate was 5.5%, and no outlier hospitals were identified.

Using the same inclusion criteria of the NQF measure but including 30-day ED revisits as an outcome, we analyzed a total of 5500 hospitalizations from 174 hospitals. The mean risk-adjusted event rate was higher at 7.9%, but there were still no outlier hospitals identified.

Using the broadened population definition (LRIA) and including 30-day ED revisits as an outcome, we analyzed a total of 8402 hospitalizations from 190 hospitals. The mean risk-adjusted event rate was 6.8%, but there were still no outlier hospitals identified.

In our final iteration, we merged 3 years of hospital data (2012-2014) using the broader population definition (LRIA) and including 30-day ED revisits as an outcome. This resulted in 27,873 admissions from 239 hospitals for this analysis, with a mean of 28 eligible hospitalizations per hospital. The mean risk-adjusted event rate was 6.7%, and this approach identified 2 high-performing (risk-adjusted rates: 3.6-5.3) and 7 low-performing hospitals (risk-adjusted rates: 10.1-15.9).

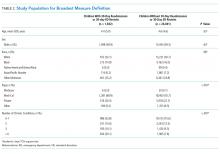

Table 2 presents the demographics of children included in this analysis. Children who had readmissions/revisits were younger, more likely to be white, less likely to have private insurance, and more likely to have a greater number of chronic conditions compared to children without readmissions/revisits.

Secondary Outcome: Hospital Costs

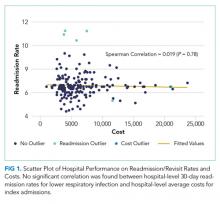

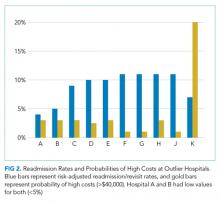

In the analysis of hospital-level costs, we found only 1 outlier high-cost hospital. There was a 20% probability of a hospital respiratory admission costing ≥$40,000 at this hospital. We found no overall relationship between hospital 30-day respiratory readmission rate and hospital costs (Figure 1). However, the hospitals that were outliers for low readmission rates also had low probabilities of excessive hospital costs (3% probability of costs >$40,000; Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

We used a nationally endorsed pediatric quality measure to evaluate hospital performance, defined as 30-day readmission rates for children with respiratory illness. We examined all-payer data from California, which is the most populous state in the country and home to 1 in 8 American children. In this large California dataset, we were unable to identify meaningful variation in hospital performance due to low hospital volumes and event rates. However, when we broadened the measure definition, we were able to identify performance variation. Our findings underscore the importance of testing and potentially modifying existing quality measures in order to more accurately capture the quality of care delivered at hospitals with lower volumes of pediatric patients.21

Our underlying assumption, in light of these prior studies, was that increasing the eligible sample in each hospital by combining respiratory diseases and by using an all-payer claims database rather than a Medicaid-only database would increase the number of detectable outlier hospitals. However, we found that these approaches did not ameliorate the limitations of small volumes. Only through aggregating data over 3 years was it possible to identify any outliers, and this approach identified only 3% of hospitals as outliers. Hence, our analysis reinforces concerns raised by several prior analyses4-7 regarding the limited ability of current pediatric readmission measures to detect meaningful, actionable differences in performance across all types of hospitals (including general/nonchildren’s hospitals). This issue is of particular concern for common pediatric conditions like respiratory illnesses, for which >70% of hospitalizations occur in general hospitals.11

Developers and utilizers of pediatric quality metrics should consider strategies for identifying meaningful, actionable variation in pediatric quality of care at general hospitals. These strategies might include our approach of combining several years of hospital data in order to reach adequate volumes for measuring performance. The potential downside to this approach is performance lag—specifically, hospitals implementing quality improvement readmissions programs may not see changes in their performance for a year or two on a measure aggregating 3 years of data. Alternatively, it is possible that the measure might be used more appropriately across a larger group of hospitals, either to assess performance for multihospital accountable care organization (ACO), or to assess performance for a service area or county. An aggregated group of hospitals would increase the eligible patient volume and, if there is an ACO relationship established, coordinated interventions could be implemented across the hospitals.

We examined the 30-day readmission rate because it is the current standard used by CMS and all NQF-endorsed readmission measures.22,23 Another potential approach is to analyze the 7- or 15-day readmission rate. However, these rates may be similarly limited in identifying hospital performance due to low volumes and event rates. An analysis by Wallace et al. of preventable readmissions to a tertiary children’s hospital found that, while many occurred within 7 days or 15 days, 27% occurred after 7 days and 22%, after 15.24 However, an analysis of several adult 30-day readmission measures used by CMS found that the contribution of hospital-level quality to the readmission rate (measured by intracluster correlation coefficient) reached a nadir at 7 days, which suggests that most readmissions after the seventh day postdischarge were explained by community- and household-level factors beyond hospitals’ control.22 Hence, though 7- or 15-day readmission rates may better represent preventable outcomes under the hospital’s control, the lower event rates and low hospital volumes likely similarly limit the feasibility of their use for performance measurement.

Pediatric quality measures are additionally intended to drive improvements in the value of pediatric care, defined as quality relative to costs.25 In order to better understand the relationship of hospital performance across both the domains of readmissions (quality) and costs, we examined hospital-level costs for care of pediatric respiratory illnesses. We found no overall relationship between hospital readmission rates and costs; however, we found 2 hospitals in California that had significantly lower readmission rates as well as low costs. Close examination of hospitals such as these, which demonstrate exceptional performance in quality and costs, may promote the discovery and dissemination of strategies to improve the value of pediatric care.12

Our study had several limitations. First, the OSHPD database lacked detailed clinical variables to correct for additional case-mix differences between hospitals. However, we used the approach of case-mix adjustment outlined by an NQF-endorsed national quality metric.8 Secondly, since our data were limited to a single state, analyses of other databases may have yielded different results. However, prior analyses using other multistate databases reported similar limitations,5,6 likely due to the limitations of patient volume that are generalizable to settings outside of California. In addition, our cost analysis was performed using cost-to-charge ratios that represent total annual expenses/revenue for the whole hospital.16 These ratios may not be reflective of the specific services provided for children in our analysis; however, service-specific costs were not available, and cost-to-charge ratios are commonly used to report costs.

CONCLUSION

The ability of a nationally-endorsed pediatric respiratory readmissions measure to meaningfully identify variation in hospital performance is limited. General hospitals, which provide the majority of pediatric care for common conditions such as LRI, likely cannot be accurately evaluated using national pediatric quality metrics as they are currently designed. Modifying measures in order to increase hospital-level pediatric patient volumes may facilitate more meaningful evaluation of the quality of pediatric care in general hospitals and identification of exceptional hospitals for understanding best practices in pediatric inpatient care.

Disclosures

Regina Lam consulted for Proximity Health doing market research during the course of developing this manuscript, but this work did not involve any content related to quality metrics, and this entity did not play any role in the development of this manuscript. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Funding

Supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K08 HS24592 to SVK and U18HS25297 to MDC and NSB) and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K23HD065836 to NSB). The funding agency played no role in the study design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Overview of hospital stays for children in the United States. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb187-Hospital-Stays-Children-2012.jsp. Accessed September 1, 2017; 2012. PubMed

2. Mendelson A, Kondo K, Damberg C, et al. The effects of pay-for-performance programs on health, health care use, and processes of care: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(5):341-353. doi: 10.7326/M16-1881. PubMed

3. Zuckerman RB, Sheingold SH, Orav EJ, Ruhter J, Epstein AM. Readmissions, observation, and the hospital readmissions reduction program. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1543-1551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1513024. PubMed

4. Bardach NS, Chien AT, Dudley RA. Small numbers limit the use of the inpatient pediatric quality indicators for hospital comparison. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(4):266-273. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.04.025. PubMed

5. Bardach NS, Vittinghoff E, Asteria-Peñaloza R, et al. Measuring hospital quality using pediatric readmission and revisit rates. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):429-436. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3527. PubMed

6. Berry JG, Zaslavsky AM, Toomey SL, et al. Recognizing differences in hospital quality performance for pediatric inpatient care. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):251-262. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3131. PubMed

7. Hain PD, Gay JC, Berutti TW, Whitney GM, Wang W, Saville BR. Preventability of early readmissions at a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e171-e181. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0820. PubMed

8. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Pediatric lower respiratory infection readmission measure. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/policymakers/chipra/factsheets/chipra_1415-p008-2-ef.pdf. Accessed September 3, 2017.

9. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. CHIPRA Pediatric Quality Measures Program. https://archive.ahrq.gov/policymakers/chipra/pqmpback.html. Accessed October 10, 2017.

10. Nakamura MM, Zaslavsky AM, Toomey SL, et al. Pediatric readmissions After hospitalizations for lower respiratory infections. Pediatrics. 2017;140(2). doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0938. PubMed

11. Leyenaar JK, Ralston SL, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Mangione-Smith R, Lindenauer PK. Epidemiology of pediatric hospitalizations at general hospitals and freestanding children’s hospitals in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(11):743-749. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2624. PubMed

12. Bradley EH, Curry LA, Ramanadhan S, Rowe L, Nembhard IM, Krumholz HM. Research in action: using positive deviance to improve quality of health care. Implement Sci. 2009;4:25. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-25. PubMed

13. California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. Data and reports. https://www.oshpd.ca.gov/HID/. Accessed September 3, 2017.

14. QualityNet. Measure methodology reports. https://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?c=Page&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier4&cid=1219069855841. Accessed October 10, 2017.

15. Riley GF. Administrative and claims records as sources of health care cost data. Med Care. 2009;47(7 Suppl 1):S51-S55. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819c95aa. PubMed

16. California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. Annual financial data. https://www.oshpd.ca.gov/HID/Hospital-Financial.asp. Accessed September 3, 2017.

17. Tukey J. Exploratory Data Analysis: Pearson; London, United Kingdom. 1977.

18. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Core measures. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityMeasures/Core-Measures.html. Accessed September 1, 2017.

19. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372-380. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.188351. PubMed

20. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. HospitalCompare. https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html. Accessed on October 10, 2017.

21. Mangione-Smith R. The challenges of addressing pediatric quality measurement gaps. Pediatrics. 2017;139(4). doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0174. PubMed

22. Chin DL, Bang H, Manickam RN, Romano PS. Rethinking thirty-day hospital readmissions: shorter intervals might be better indicators of quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(10):1867-1875. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0205. PubMed

23. National Quality Forum. Measures, reports, and tools. http://www.qualityforum.org/Measures_Reports_Tools.aspx. Accessed March 1, 2018.

24. Wallace SS, Keller SL, Falco CN, et al. An examination of physician-, caregiver-, and disease-related factors associated With readmission From a pediatric hospital medicine service. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(11):566-573. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2015-0015. PubMed

25. Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2477-2481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011024. PubMed

Respiratory illnesses are the leading causes of pediatric hospitalizations in the United States.1 The 30-day hospital readmission rate for respiratory illnesses is being considered for implementation as a national hospital performance measure, as it may be an indicator of lower quality care (eg, poor hospital management of disease, inadequate patient/caretaker education prior to discharge). In adult populations, readmissions can be used to reliably identify variation in hospital performance and successfully drive efforts to improve the value of care.2, 3 In contrast, there are persistent concerns about using pediatric readmissions to identify variation in hospital performance, largely due to lower patient volumes.4-7 To increase the value of pediatric hospital care, it is important to develop ways to meaningfully measure quality of care and further, to better understand the relationship between measures of quality and healthcare costs.

In December 2016, the National Quality Forum (NQF) endorsed a Pediatric Lower Respiratory Infection (LRI) Readmission Measure.8 This measure was developed by the Pediatric Quality Measurement Program, through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The goal of this program was to “increase the portfolio of evidence-based, consensus pediatric quality measures available to public and private purchasers of children’s healthcare services, providers, and consumers.”9

In anticipation of the national implementation of pediatric readmission measures, we examined whether the Pediatric LRI Readmission Measure could meaningfully identify high and low performers across all types of hospitals admitting children (general hospitals and children’s hospitals) using an all-payer claims database. A recent analysis by Nakamura et al. identified high and low performers using this measure10 but limited the analysis to hospitals with >50 pediatric LRI admissions per year, an approach that excludes many general hospitals. Since general hospitals provide the majority of care for children hospitalized with respiratory infections,11 we aimed to evaluate the measure in a broadly inclusive analysis that included all hospital types. Because low patient volumes might limit use of the measure,4,6 we tested several broadened variations of the measure. We also examined the relationship between hospital performance in pediatric LRI readmissions and healthcare costs.

Our analysis is intended to inform utilizers of pediatric quality metrics and policy makers about the feasibility of using these metrics to publicly report hospital performance and/or identify exceptional hospitals for understanding best practices in pediatric inpatient care.12

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

We conducted an observational, retrospective cohort analysis using the 2012-2014 California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) nonpublic inpatient and emergency department databases.13 The OSHPD databases are compiled annually through mandatory reporting by all licensed nonfederal hospitals in California. The databases contain demographic (eg, age, gender) and utilization data (eg, charges) and can track readmissions to hospitals other than the index hospital. The databases capture administrative claims from approximately 450 hospitals, composed of 16 million inpatients, emergency department patients, and ambulatory surgery patients annually. Data quality is monitored through the California OSHPD.

Study Population

Our study included children aged ≤18 years with LRI, defined using the NQF Pediatric LRI Readmissions Measure: a primary diagnosis of bronchiolitis, influenza, or pneumonia, or a secondary diagnosis of bronchiolitis, influenza, or pneumonia, with a primary diagnosis of asthma, respiratory failure, sepsis, or bacteremia.8 International classification of Diseases, 9th edition (ICD-9) diagnostic codes used are in Appendix 1.

Per the NQF measure specifications,8 records were excluded if they were from hospitals with <80% of records complete with core elements (unique patient identifier, admission date, end-of-service date, and ICD-9 primary diagnosis code). In addition, records were excluded for the following reasons: (1) individual record missing core elements, (2) discharge disposition “death,” (3) 30-day follow-up data not available, (4) primary “newborn” or mental health diagnosis, or (5) primary ICD-9 procedure code for a planned procedure or chemotherapy.

Patient characteristics for hospital admissions with and without 30-day readmissions or 30-day emergency department (ED) revisits were summarized. For the continuous variable age, mean and standard deviation for each group were calculated. For categorical variables (sex, race, payer, and number of chronic conditions), numbers and proportions were determined. Univariate tests of comparison were carried out using the Student’s t test for age and chi-square tests for all categorical variables. Categories of payer with small values were combined for ease of description (categories combined into “other:” workers’ compensation, county indigent programs, other government, other indigent, self-pay, other payer). We identified chronic conditions using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Chronic Condition Indicator (CCI) system, which classifies ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes as chronic or acute and places each code into 1 of 18 mutually exclusive categories (organ systems, disease categories, or other categories). The case-mix adjustment model incorporates a binary variable for each CCI category (0-1, 2, 3, or >4 chronic conditions) per the NQF measure specifications.8 This study was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was the hospital-level rate of 30-day readmission after hospital discharge, consistent with the NQF measure.8 We identified outlier hospitals for 30-day readmission rate using the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) methodology, which defines outlier hospitals as those for whom adjusted readmission rate confidence intervals do not overlap with the overall group mean rate.5, 14

We also determined the hospital-level average cost per index hospitalization (not including costs of readmissions). Since costs of care often differ substantially from charges,15 costs were calculated using cost-to-charge ratios for each hospital (annual total operating expenses/total gross patient revenue, as reported to the OSHPD).16 Costs were subdivided into categories representing $5,000 increments and a top category of >$40,000. Outlier hospitals for costs were defined as those for whom the cost random effect was either greater than the third quartile of the distribution of values by more than 1.5 times the interquartile range or less than the first quartile of the distribution of values by more than 1.5 times the interquartile range.17

ANALYSIS

Primary Analysis

For our primary analysis of 30-day hospital readmission rates, we used hierarchical logistic regression models with hospitals as random effects, adjusting for patient age, sex, and the presence and number of body systems affected by chronic conditions.8 These 4 patient characteristics were selected by the NQF measure developers “because distributions of these characteristics vary across hospitals, and although they are associated with readmission risk, they are independent of hospital quality of care.”10

Because the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) are in the process of selecting pediatric quality measures for meaningful use reporting,18 we utilized CMS hospital readmissions methodology to calculate risk-adjusted rates and identify outlier hospitals. The CMS modeling strategy stabilizes performance estimates for low-volume hospitals and avoids penalizing these hospitals for high readmission rates that may be due to chance (random effects logistic model to obtain best linear unbiased predictions). This is particularly important in pediatrics, given the low pediatric volumes in many hospitals admitting children.4,19 We then identified outlier hospitals for the 30-day readmission rate using CMS methodology (hospital’s adjusted readmission rate confidence interval does not overlap the overall group mean rate).5, 4 CMS uses this approach for public reporting on HospitalCompare.20

Sensitivity Analyses

We tested several broadening variations of the NQF measure: (1) addition of children admitted with a primary diagnosis of asthma (without requiring LRI as a secondary diagnosis) or a secondary diagnosis of asthma exacerbation (LRIA), (2) inclusion of 30-day ED revisits as an outcome, and (3) merging of 3 years of data. These analyses were all performed using the same modeling strategy as in our primary analysis.

Secondary Outcome Analyses

Our analysis of hospital costs used costs for index admissions over 3 years (2012–2014) and included admissions for asthma. We used hierarchical regression models with hospitals as random effects, adjusting for age, gender, and the presence and number of chronic conditions. The distribution of cost values was highly skewed, so ordinal models were selected after several other modeling approaches failed (log transformation linear model, gamma model, Poisson model, zero-truncated Poisson model).

The relationship between hospital-level costs and hospital-level 30-day readmission or ED revisit rates was analyzed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute; Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Primary Analysis of 30-day Readmissions (per National Quality Forum Measure)

Our analysis of the 2014 OSHPD database using the specifications of the NQF Pediatric LRI Readmission Measure included a total of 5550 hospitalizations from 174 hospitals, with a mean of 12 eligible hospitalizations per hospital. The mean risk-adjusted readmission rate was 6.5% (362 readmissions). There were no hospitals that were considered outliers based on the risk-adjusted readmission rates (Table 1).

Sensitivity Analyses (Broadening Definitions of National Quality Forum Measure)

We report our testing of the broadened variations of the NQF measure in Table 1. Broadening the population to include children with asthma as a primary diagnosis and children with asthma exacerbations as a secondary diagnosis (LRIA) increased the size of our analysis to 8402 hospitalizations from 190 hospitals. The mean risk-adjusted readmission rate was 5.5%, and no outlier hospitals were identified.

Using the same inclusion criteria of the NQF measure but including 30-day ED revisits as an outcome, we analyzed a total of 5500 hospitalizations from 174 hospitals. The mean risk-adjusted event rate was higher at 7.9%, but there were still no outlier hospitals identified.

Using the broadened population definition (LRIA) and including 30-day ED revisits as an outcome, we analyzed a total of 8402 hospitalizations from 190 hospitals. The mean risk-adjusted event rate was 6.8%, but there were still no outlier hospitals identified.

In our final iteration, we merged 3 years of hospital data (2012-2014) using the broader population definition (LRIA) and including 30-day ED revisits as an outcome. This resulted in 27,873 admissions from 239 hospitals for this analysis, with a mean of 28 eligible hospitalizations per hospital. The mean risk-adjusted event rate was 6.7%, and this approach identified 2 high-performing (risk-adjusted rates: 3.6-5.3) and 7 low-performing hospitals (risk-adjusted rates: 10.1-15.9).

Table 2 presents the demographics of children included in this analysis. Children who had readmissions/revisits were younger, more likely to be white, less likely to have private insurance, and more likely to have a greater number of chronic conditions compared to children without readmissions/revisits.

Secondary Outcome: Hospital Costs

In the analysis of hospital-level costs, we found only 1 outlier high-cost hospital. There was a 20% probability of a hospital respiratory admission costing ≥$40,000 at this hospital. We found no overall relationship between hospital 30-day respiratory readmission rate and hospital costs (Figure 1). However, the hospitals that were outliers for low readmission rates also had low probabilities of excessive hospital costs (3% probability of costs >$40,000; Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

We used a nationally endorsed pediatric quality measure to evaluate hospital performance, defined as 30-day readmission rates for children with respiratory illness. We examined all-payer data from California, which is the most populous state in the country and home to 1 in 8 American children. In this large California dataset, we were unable to identify meaningful variation in hospital performance due to low hospital volumes and event rates. However, when we broadened the measure definition, we were able to identify performance variation. Our findings underscore the importance of testing and potentially modifying existing quality measures in order to more accurately capture the quality of care delivered at hospitals with lower volumes of pediatric patients.21

Our underlying assumption, in light of these prior studies, was that increasing the eligible sample in each hospital by combining respiratory diseases and by using an all-payer claims database rather than a Medicaid-only database would increase the number of detectable outlier hospitals. However, we found that these approaches did not ameliorate the limitations of small volumes. Only through aggregating data over 3 years was it possible to identify any outliers, and this approach identified only 3% of hospitals as outliers. Hence, our analysis reinforces concerns raised by several prior analyses4-7 regarding the limited ability of current pediatric readmission measures to detect meaningful, actionable differences in performance across all types of hospitals (including general/nonchildren’s hospitals). This issue is of particular concern for common pediatric conditions like respiratory illnesses, for which >70% of hospitalizations occur in general hospitals.11

Developers and utilizers of pediatric quality metrics should consider strategies for identifying meaningful, actionable variation in pediatric quality of care at general hospitals. These strategies might include our approach of combining several years of hospital data in order to reach adequate volumes for measuring performance. The potential downside to this approach is performance lag—specifically, hospitals implementing quality improvement readmissions programs may not see changes in their performance for a year or two on a measure aggregating 3 years of data. Alternatively, it is possible that the measure might be used more appropriately across a larger group of hospitals, either to assess performance for multihospital accountable care organization (ACO), or to assess performance for a service area or county. An aggregated group of hospitals would increase the eligible patient volume and, if there is an ACO relationship established, coordinated interventions could be implemented across the hospitals.

We examined the 30-day readmission rate because it is the current standard used by CMS and all NQF-endorsed readmission measures.22,23 Another potential approach is to analyze the 7- or 15-day readmission rate. However, these rates may be similarly limited in identifying hospital performance due to low volumes and event rates. An analysis by Wallace et al. of preventable readmissions to a tertiary children’s hospital found that, while many occurred within 7 days or 15 days, 27% occurred after 7 days and 22%, after 15.24 However, an analysis of several adult 30-day readmission measures used by CMS found that the contribution of hospital-level quality to the readmission rate (measured by intracluster correlation coefficient) reached a nadir at 7 days, which suggests that most readmissions after the seventh day postdischarge were explained by community- and household-level factors beyond hospitals’ control.22 Hence, though 7- or 15-day readmission rates may better represent preventable outcomes under the hospital’s control, the lower event rates and low hospital volumes likely similarly limit the feasibility of their use for performance measurement.

Pediatric quality measures are additionally intended to drive improvements in the value of pediatric care, defined as quality relative to costs.25 In order to better understand the relationship of hospital performance across both the domains of readmissions (quality) and costs, we examined hospital-level costs for care of pediatric respiratory illnesses. We found no overall relationship between hospital readmission rates and costs; however, we found 2 hospitals in California that had significantly lower readmission rates as well as low costs. Close examination of hospitals such as these, which demonstrate exceptional performance in quality and costs, may promote the discovery and dissemination of strategies to improve the value of pediatric care.12

Our study had several limitations. First, the OSHPD database lacked detailed clinical variables to correct for additional case-mix differences between hospitals. However, we used the approach of case-mix adjustment outlined by an NQF-endorsed national quality metric.8 Secondly, since our data were limited to a single state, analyses of other databases may have yielded different results. However, prior analyses using other multistate databases reported similar limitations,5,6 likely due to the limitations of patient volume that are generalizable to settings outside of California. In addition, our cost analysis was performed using cost-to-charge ratios that represent total annual expenses/revenue for the whole hospital.16 These ratios may not be reflective of the specific services provided for children in our analysis; however, service-specific costs were not available, and cost-to-charge ratios are commonly used to report costs.

CONCLUSION

The ability of a nationally-endorsed pediatric respiratory readmissions measure to meaningfully identify variation in hospital performance is limited. General hospitals, which provide the majority of pediatric care for common conditions such as LRI, likely cannot be accurately evaluated using national pediatric quality metrics as they are currently designed. Modifying measures in order to increase hospital-level pediatric patient volumes may facilitate more meaningful evaluation of the quality of pediatric care in general hospitals and identification of exceptional hospitals for understanding best practices in pediatric inpatient care.

Disclosures

Regina Lam consulted for Proximity Health doing market research during the course of developing this manuscript, but this work did not involve any content related to quality metrics, and this entity did not play any role in the development of this manuscript. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Funding

Supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K08 HS24592 to SVK and U18HS25297 to MDC and NSB) and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K23HD065836 to NSB). The funding agency played no role in the study design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Respiratory illnesses are the leading causes of pediatric hospitalizations in the United States.1 The 30-day hospital readmission rate for respiratory illnesses is being considered for implementation as a national hospital performance measure, as it may be an indicator of lower quality care (eg, poor hospital management of disease, inadequate patient/caretaker education prior to discharge). In adult populations, readmissions can be used to reliably identify variation in hospital performance and successfully drive efforts to improve the value of care.2, 3 In contrast, there are persistent concerns about using pediatric readmissions to identify variation in hospital performance, largely due to lower patient volumes.4-7 To increase the value of pediatric hospital care, it is important to develop ways to meaningfully measure quality of care and further, to better understand the relationship between measures of quality and healthcare costs.

In December 2016, the National Quality Forum (NQF) endorsed a Pediatric Lower Respiratory Infection (LRI) Readmission Measure.8 This measure was developed by the Pediatric Quality Measurement Program, through the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. The goal of this program was to “increase the portfolio of evidence-based, consensus pediatric quality measures available to public and private purchasers of children’s healthcare services, providers, and consumers.”9

In anticipation of the national implementation of pediatric readmission measures, we examined whether the Pediatric LRI Readmission Measure could meaningfully identify high and low performers across all types of hospitals admitting children (general hospitals and children’s hospitals) using an all-payer claims database. A recent analysis by Nakamura et al. identified high and low performers using this measure10 but limited the analysis to hospitals with >50 pediatric LRI admissions per year, an approach that excludes many general hospitals. Since general hospitals provide the majority of care for children hospitalized with respiratory infections,11 we aimed to evaluate the measure in a broadly inclusive analysis that included all hospital types. Because low patient volumes might limit use of the measure,4,6 we tested several broadened variations of the measure. We also examined the relationship between hospital performance in pediatric LRI readmissions and healthcare costs.

Our analysis is intended to inform utilizers of pediatric quality metrics and policy makers about the feasibility of using these metrics to publicly report hospital performance and/or identify exceptional hospitals for understanding best practices in pediatric inpatient care.12

METHODS

Study Design and Data Source

We conducted an observational, retrospective cohort analysis using the 2012-2014 California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development (OSHPD) nonpublic inpatient and emergency department databases.13 The OSHPD databases are compiled annually through mandatory reporting by all licensed nonfederal hospitals in California. The databases contain demographic (eg, age, gender) and utilization data (eg, charges) and can track readmissions to hospitals other than the index hospital. The databases capture administrative claims from approximately 450 hospitals, composed of 16 million inpatients, emergency department patients, and ambulatory surgery patients annually. Data quality is monitored through the California OSHPD.

Study Population

Our study included children aged ≤18 years with LRI, defined using the NQF Pediatric LRI Readmissions Measure: a primary diagnosis of bronchiolitis, influenza, or pneumonia, or a secondary diagnosis of bronchiolitis, influenza, or pneumonia, with a primary diagnosis of asthma, respiratory failure, sepsis, or bacteremia.8 International classification of Diseases, 9th edition (ICD-9) diagnostic codes used are in Appendix 1.

Per the NQF measure specifications,8 records were excluded if they were from hospitals with <80% of records complete with core elements (unique patient identifier, admission date, end-of-service date, and ICD-9 primary diagnosis code). In addition, records were excluded for the following reasons: (1) individual record missing core elements, (2) discharge disposition “death,” (3) 30-day follow-up data not available, (4) primary “newborn” or mental health diagnosis, or (5) primary ICD-9 procedure code for a planned procedure or chemotherapy.

Patient characteristics for hospital admissions with and without 30-day readmissions or 30-day emergency department (ED) revisits were summarized. For the continuous variable age, mean and standard deviation for each group were calculated. For categorical variables (sex, race, payer, and number of chronic conditions), numbers and proportions were determined. Univariate tests of comparison were carried out using the Student’s t test for age and chi-square tests for all categorical variables. Categories of payer with small values were combined for ease of description (categories combined into “other:” workers’ compensation, county indigent programs, other government, other indigent, self-pay, other payer). We identified chronic conditions using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Chronic Condition Indicator (CCI) system, which classifies ICD-9-CM diagnosis codes as chronic or acute and places each code into 1 of 18 mutually exclusive categories (organ systems, disease categories, or other categories). The case-mix adjustment model incorporates a binary variable for each CCI category (0-1, 2, 3, or >4 chronic conditions) per the NQF measure specifications.8 This study was approved by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board.

Outcomes

Our primary outcome was the hospital-level rate of 30-day readmission after hospital discharge, consistent with the NQF measure.8 We identified outlier hospitals for 30-day readmission rate using the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) methodology, which defines outlier hospitals as those for whom adjusted readmission rate confidence intervals do not overlap with the overall group mean rate.5, 14

We also determined the hospital-level average cost per index hospitalization (not including costs of readmissions). Since costs of care often differ substantially from charges,15 costs were calculated using cost-to-charge ratios for each hospital (annual total operating expenses/total gross patient revenue, as reported to the OSHPD).16 Costs were subdivided into categories representing $5,000 increments and a top category of >$40,000. Outlier hospitals for costs were defined as those for whom the cost random effect was either greater than the third quartile of the distribution of values by more than 1.5 times the interquartile range or less than the first quartile of the distribution of values by more than 1.5 times the interquartile range.17

ANALYSIS

Primary Analysis

For our primary analysis of 30-day hospital readmission rates, we used hierarchical logistic regression models with hospitals as random effects, adjusting for patient age, sex, and the presence and number of body systems affected by chronic conditions.8 These 4 patient characteristics were selected by the NQF measure developers “because distributions of these characteristics vary across hospitals, and although they are associated with readmission risk, they are independent of hospital quality of care.”10

Because the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) are in the process of selecting pediatric quality measures for meaningful use reporting,18 we utilized CMS hospital readmissions methodology to calculate risk-adjusted rates and identify outlier hospitals. The CMS modeling strategy stabilizes performance estimates for low-volume hospitals and avoids penalizing these hospitals for high readmission rates that may be due to chance (random effects logistic model to obtain best linear unbiased predictions). This is particularly important in pediatrics, given the low pediatric volumes in many hospitals admitting children.4,19 We then identified outlier hospitals for the 30-day readmission rate using CMS methodology (hospital’s adjusted readmission rate confidence interval does not overlap the overall group mean rate).5, 4 CMS uses this approach for public reporting on HospitalCompare.20

Sensitivity Analyses

We tested several broadening variations of the NQF measure: (1) addition of children admitted with a primary diagnosis of asthma (without requiring LRI as a secondary diagnosis) or a secondary diagnosis of asthma exacerbation (LRIA), (2) inclusion of 30-day ED revisits as an outcome, and (3) merging of 3 years of data. These analyses were all performed using the same modeling strategy as in our primary analysis.

Secondary Outcome Analyses

Our analysis of hospital costs used costs for index admissions over 3 years (2012–2014) and included admissions for asthma. We used hierarchical regression models with hospitals as random effects, adjusting for age, gender, and the presence and number of chronic conditions. The distribution of cost values was highly skewed, so ordinal models were selected after several other modeling approaches failed (log transformation linear model, gamma model, Poisson model, zero-truncated Poisson model).

The relationship between hospital-level costs and hospital-level 30-day readmission or ED revisit rates was analyzed using Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient. Statistical analysis was performed using SAS version 9.4 software (SAS Institute; Cary, North Carolina).

RESULTS

Primary Analysis of 30-day Readmissions (per National Quality Forum Measure)

Our analysis of the 2014 OSHPD database using the specifications of the NQF Pediatric LRI Readmission Measure included a total of 5550 hospitalizations from 174 hospitals, with a mean of 12 eligible hospitalizations per hospital. The mean risk-adjusted readmission rate was 6.5% (362 readmissions). There were no hospitals that were considered outliers based on the risk-adjusted readmission rates (Table 1).

Sensitivity Analyses (Broadening Definitions of National Quality Forum Measure)

We report our testing of the broadened variations of the NQF measure in Table 1. Broadening the population to include children with asthma as a primary diagnosis and children with asthma exacerbations as a secondary diagnosis (LRIA) increased the size of our analysis to 8402 hospitalizations from 190 hospitals. The mean risk-adjusted readmission rate was 5.5%, and no outlier hospitals were identified.

Using the same inclusion criteria of the NQF measure but including 30-day ED revisits as an outcome, we analyzed a total of 5500 hospitalizations from 174 hospitals. The mean risk-adjusted event rate was higher at 7.9%, but there were still no outlier hospitals identified.

Using the broadened population definition (LRIA) and including 30-day ED revisits as an outcome, we analyzed a total of 8402 hospitalizations from 190 hospitals. The mean risk-adjusted event rate was 6.8%, but there were still no outlier hospitals identified.

In our final iteration, we merged 3 years of hospital data (2012-2014) using the broader population definition (LRIA) and including 30-day ED revisits as an outcome. This resulted in 27,873 admissions from 239 hospitals for this analysis, with a mean of 28 eligible hospitalizations per hospital. The mean risk-adjusted event rate was 6.7%, and this approach identified 2 high-performing (risk-adjusted rates: 3.6-5.3) and 7 low-performing hospitals (risk-adjusted rates: 10.1-15.9).

Table 2 presents the demographics of children included in this analysis. Children who had readmissions/revisits were younger, more likely to be white, less likely to have private insurance, and more likely to have a greater number of chronic conditions compared to children without readmissions/revisits.

Secondary Outcome: Hospital Costs

In the analysis of hospital-level costs, we found only 1 outlier high-cost hospital. There was a 20% probability of a hospital respiratory admission costing ≥$40,000 at this hospital. We found no overall relationship between hospital 30-day respiratory readmission rate and hospital costs (Figure 1). However, the hospitals that were outliers for low readmission rates also had low probabilities of excessive hospital costs (3% probability of costs >$40,000; Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

We used a nationally endorsed pediatric quality measure to evaluate hospital performance, defined as 30-day readmission rates for children with respiratory illness. We examined all-payer data from California, which is the most populous state in the country and home to 1 in 8 American children. In this large California dataset, we were unable to identify meaningful variation in hospital performance due to low hospital volumes and event rates. However, when we broadened the measure definition, we were able to identify performance variation. Our findings underscore the importance of testing and potentially modifying existing quality measures in order to more accurately capture the quality of care delivered at hospitals with lower volumes of pediatric patients.21

Our underlying assumption, in light of these prior studies, was that increasing the eligible sample in each hospital by combining respiratory diseases and by using an all-payer claims database rather than a Medicaid-only database would increase the number of detectable outlier hospitals. However, we found that these approaches did not ameliorate the limitations of small volumes. Only through aggregating data over 3 years was it possible to identify any outliers, and this approach identified only 3% of hospitals as outliers. Hence, our analysis reinforces concerns raised by several prior analyses4-7 regarding the limited ability of current pediatric readmission measures to detect meaningful, actionable differences in performance across all types of hospitals (including general/nonchildren’s hospitals). This issue is of particular concern for common pediatric conditions like respiratory illnesses, for which >70% of hospitalizations occur in general hospitals.11

Developers and utilizers of pediatric quality metrics should consider strategies for identifying meaningful, actionable variation in pediatric quality of care at general hospitals. These strategies might include our approach of combining several years of hospital data in order to reach adequate volumes for measuring performance. The potential downside to this approach is performance lag—specifically, hospitals implementing quality improvement readmissions programs may not see changes in their performance for a year or two on a measure aggregating 3 years of data. Alternatively, it is possible that the measure might be used more appropriately across a larger group of hospitals, either to assess performance for multihospital accountable care organization (ACO), or to assess performance for a service area or county. An aggregated group of hospitals would increase the eligible patient volume and, if there is an ACO relationship established, coordinated interventions could be implemented across the hospitals.

We examined the 30-day readmission rate because it is the current standard used by CMS and all NQF-endorsed readmission measures.22,23 Another potential approach is to analyze the 7- or 15-day readmission rate. However, these rates may be similarly limited in identifying hospital performance due to low volumes and event rates. An analysis by Wallace et al. of preventable readmissions to a tertiary children’s hospital found that, while many occurred within 7 days or 15 days, 27% occurred after 7 days and 22%, after 15.24 However, an analysis of several adult 30-day readmission measures used by CMS found that the contribution of hospital-level quality to the readmission rate (measured by intracluster correlation coefficient) reached a nadir at 7 days, which suggests that most readmissions after the seventh day postdischarge were explained by community- and household-level factors beyond hospitals’ control.22 Hence, though 7- or 15-day readmission rates may better represent preventable outcomes under the hospital’s control, the lower event rates and low hospital volumes likely similarly limit the feasibility of their use for performance measurement.

Pediatric quality measures are additionally intended to drive improvements in the value of pediatric care, defined as quality relative to costs.25 In order to better understand the relationship of hospital performance across both the domains of readmissions (quality) and costs, we examined hospital-level costs for care of pediatric respiratory illnesses. We found no overall relationship between hospital readmission rates and costs; however, we found 2 hospitals in California that had significantly lower readmission rates as well as low costs. Close examination of hospitals such as these, which demonstrate exceptional performance in quality and costs, may promote the discovery and dissemination of strategies to improve the value of pediatric care.12

Our study had several limitations. First, the OSHPD database lacked detailed clinical variables to correct for additional case-mix differences between hospitals. However, we used the approach of case-mix adjustment outlined by an NQF-endorsed national quality metric.8 Secondly, since our data were limited to a single state, analyses of other databases may have yielded different results. However, prior analyses using other multistate databases reported similar limitations,5,6 likely due to the limitations of patient volume that are generalizable to settings outside of California. In addition, our cost analysis was performed using cost-to-charge ratios that represent total annual expenses/revenue for the whole hospital.16 These ratios may not be reflective of the specific services provided for children in our analysis; however, service-specific costs were not available, and cost-to-charge ratios are commonly used to report costs.

CONCLUSION

The ability of a nationally-endorsed pediatric respiratory readmissions measure to meaningfully identify variation in hospital performance is limited. General hospitals, which provide the majority of pediatric care for common conditions such as LRI, likely cannot be accurately evaluated using national pediatric quality metrics as they are currently designed. Modifying measures in order to increase hospital-level pediatric patient volumes may facilitate more meaningful evaluation of the quality of pediatric care in general hospitals and identification of exceptional hospitals for understanding best practices in pediatric inpatient care.

Disclosures

Regina Lam consulted for Proximity Health doing market research during the course of developing this manuscript, but this work did not involve any content related to quality metrics, and this entity did not play any role in the development of this manuscript. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest relevant to this article to disclose.

Funding

Supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K08 HS24592 to SVK and U18HS25297 to MDC and NSB) and the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (K23HD065836 to NSB). The funding agency played no role in the study design; the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; the writing of the report; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Overview of hospital stays for children in the United States. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb187-Hospital-Stays-Children-2012.jsp. Accessed September 1, 2017; 2012. PubMed

2. Mendelson A, Kondo K, Damberg C, et al. The effects of pay-for-performance programs on health, health care use, and processes of care: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(5):341-353. doi: 10.7326/M16-1881. PubMed

3. Zuckerman RB, Sheingold SH, Orav EJ, Ruhter J, Epstein AM. Readmissions, observation, and the hospital readmissions reduction program. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1543-1551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1513024. PubMed

4. Bardach NS, Chien AT, Dudley RA. Small numbers limit the use of the inpatient pediatric quality indicators for hospital comparison. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(4):266-273. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.04.025. PubMed

5. Bardach NS, Vittinghoff E, Asteria-Peñaloza R, et al. Measuring hospital quality using pediatric readmission and revisit rates. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):429-436. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3527. PubMed

6. Berry JG, Zaslavsky AM, Toomey SL, et al. Recognizing differences in hospital quality performance for pediatric inpatient care. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):251-262. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3131. PubMed

7. Hain PD, Gay JC, Berutti TW, Whitney GM, Wang W, Saville BR. Preventability of early readmissions at a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e171-e181. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0820. PubMed

8. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Pediatric lower respiratory infection readmission measure. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/policymakers/chipra/factsheets/chipra_1415-p008-2-ef.pdf. Accessed September 3, 2017.

9. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. CHIPRA Pediatric Quality Measures Program. https://archive.ahrq.gov/policymakers/chipra/pqmpback.html. Accessed October 10, 2017.

10. Nakamura MM, Zaslavsky AM, Toomey SL, et al. Pediatric readmissions After hospitalizations for lower respiratory infections. Pediatrics. 2017;140(2). doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0938. PubMed

11. Leyenaar JK, Ralston SL, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Mangione-Smith R, Lindenauer PK. Epidemiology of pediatric hospitalizations at general hospitals and freestanding children’s hospitals in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(11):743-749. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2624. PubMed

12. Bradley EH, Curry LA, Ramanadhan S, Rowe L, Nembhard IM, Krumholz HM. Research in action: using positive deviance to improve quality of health care. Implement Sci. 2009;4:25. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-25. PubMed

13. California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. Data and reports. https://www.oshpd.ca.gov/HID/. Accessed September 3, 2017.

14. QualityNet. Measure methodology reports. https://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?c=Page&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier4&cid=1219069855841. Accessed October 10, 2017.

15. Riley GF. Administrative and claims records as sources of health care cost data. Med Care. 2009;47(7 Suppl 1):S51-S55. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819c95aa. PubMed

16. California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. Annual financial data. https://www.oshpd.ca.gov/HID/Hospital-Financial.asp. Accessed September 3, 2017.

17. Tukey J. Exploratory Data Analysis: Pearson; London, United Kingdom. 1977.

18. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Core measures. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityMeasures/Core-Measures.html. Accessed September 1, 2017.

19. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372-380. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.188351. PubMed

20. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. HospitalCompare. https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html. Accessed on October 10, 2017.

21. Mangione-Smith R. The challenges of addressing pediatric quality measurement gaps. Pediatrics. 2017;139(4). doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0174. PubMed

22. Chin DL, Bang H, Manickam RN, Romano PS. Rethinking thirty-day hospital readmissions: shorter intervals might be better indicators of quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(10):1867-1875. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0205. PubMed

23. National Quality Forum. Measures, reports, and tools. http://www.qualityforum.org/Measures_Reports_Tools.aspx. Accessed March 1, 2018.

24. Wallace SS, Keller SL, Falco CN, et al. An examination of physician-, caregiver-, and disease-related factors associated With readmission From a pediatric hospital medicine service. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(11):566-573. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2015-0015. PubMed

25. Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2477-2481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011024. PubMed

1. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Overview of hospital stays for children in the United States. https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/reports/statbriefs/sb187-Hospital-Stays-Children-2012.jsp. Accessed September 1, 2017; 2012. PubMed

2. Mendelson A, Kondo K, Damberg C, et al. The effects of pay-for-performance programs on health, health care use, and processes of care: A systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(5):341-353. doi: 10.7326/M16-1881. PubMed

3. Zuckerman RB, Sheingold SH, Orav EJ, Ruhter J, Epstein AM. Readmissions, observation, and the hospital readmissions reduction program. N Engl J Med. 2016;374(16):1543-1551. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1513024. PubMed

4. Bardach NS, Chien AT, Dudley RA. Small numbers limit the use of the inpatient pediatric quality indicators for hospital comparison. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(4):266-273. doi: 10.1016/j.acap.2010.04.025. PubMed

5. Bardach NS, Vittinghoff E, Asteria-Peñaloza R, et al. Measuring hospital quality using pediatric readmission and revisit rates. Pediatrics. 2013;132(3):429-436. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3527. PubMed

6. Berry JG, Zaslavsky AM, Toomey SL, et al. Recognizing differences in hospital quality performance for pediatric inpatient care. Pediatrics. 2015;136(2):251-262. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3131. PubMed

7. Hain PD, Gay JC, Berutti TW, Whitney GM, Wang W, Saville BR. Preventability of early readmissions at a children’s hospital. Pediatrics. 2013;131(1):e171-e181. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-0820. PubMed

8. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Pediatric lower respiratory infection readmission measure. https://www.ahrq.gov/sites/default/files/wysiwyg/policymakers/chipra/factsheets/chipra_1415-p008-2-ef.pdf. Accessed September 3, 2017.

9. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. CHIPRA Pediatric Quality Measures Program. https://archive.ahrq.gov/policymakers/chipra/pqmpback.html. Accessed October 10, 2017.

10. Nakamura MM, Zaslavsky AM, Toomey SL, et al. Pediatric readmissions After hospitalizations for lower respiratory infections. Pediatrics. 2017;140(2). doi: 10.1542/peds.2016-0938. PubMed

11. Leyenaar JK, Ralston SL, Shieh MS, Pekow PS, Mangione-Smith R, Lindenauer PK. Epidemiology of pediatric hospitalizations at general hospitals and freestanding children’s hospitals in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2016;11(11):743-749. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2624. PubMed

12. Bradley EH, Curry LA, Ramanadhan S, Rowe L, Nembhard IM, Krumholz HM. Research in action: using positive deviance to improve quality of health care. Implement Sci. 2009;4:25. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-25. PubMed

13. California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. Data and reports. https://www.oshpd.ca.gov/HID/. Accessed September 3, 2017.

14. QualityNet. Measure methodology reports. https://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?c=Page&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier4&cid=1219069855841. Accessed October 10, 2017.

15. Riley GF. Administrative and claims records as sources of health care cost data. Med Care. 2009;47(7 Suppl 1):S51-S55. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e31819c95aa. PubMed

16. California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development. Annual financial data. https://www.oshpd.ca.gov/HID/Hospital-Financial.asp. Accessed September 3, 2017.

17. Tukey J. Exploratory Data Analysis: Pearson; London, United Kingdom. 1977.

18. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Core measures. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/QualityMeasures/Core-Measures.html. Accessed September 1, 2017.

19. Berry JG, Toomey SL, Zaslavsky AM, et al. Pediatric readmission prevalence and variability across hospitals. JAMA. 2013;309(4):372-380. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.188351. PubMed

20. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. HospitalCompare. https://www.medicare.gov/hospitalcompare/search.html. Accessed on October 10, 2017.

21. Mangione-Smith R. The challenges of addressing pediatric quality measurement gaps. Pediatrics. 2017;139(4). doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-0174. PubMed

22. Chin DL, Bang H, Manickam RN, Romano PS. Rethinking thirty-day hospital readmissions: shorter intervals might be better indicators of quality of care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2016;35(10):1867-1875. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2016.0205. PubMed

23. National Quality Forum. Measures, reports, and tools. http://www.qualityforum.org/Measures_Reports_Tools.aspx. Accessed March 1, 2018.

24. Wallace SS, Keller SL, Falco CN, et al. An examination of physician-, caregiver-, and disease-related factors associated With readmission From a pediatric hospital medicine service. Hosp Pediatr. 2015;5(11):566-573. doi: 10.1542/hpeds.2015-0015. PubMed

25. Porter ME. What is value in health care? N Engl J Med. 2010;363(26):2477-2481. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1011024. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine

It’s time for a strategic approach to observation care

After patients have experienced an illness requiring a hospital stay, they are increasingly finding that despite having received treatment in a hospital bed, they were never actually admitted—at least not from the perspective of their insurers. Instead, these patients were kept under observation, an outpatient designation that allows a hospital to bill for observation services without formally admitting a patient.

Recent studies have recorded significant increases in hospitals’ use of observation stays among the Medicare population,1-3 raising concerns about the financial ramifications for patients. Under observation, patients are potentially responsible for a greater share of the cost and bear the financial consequences of inappropriate observation stays. Currently, around 6% of Medicare patients hospitalized as outpatients spend more than 48 hours (or two midnights) in observation, sometimes much longer, exposing them to significant out-of-pocket costs.3 In addition, liberal use of observation can lead to increased hospital stays, for example among lower-severity emergency department (ED) patients who could have been safely discharged but were instead kept for a costly observation stay.4 At the same time, hospitals do not necessarily benefit from this cost shifting; in fact, hospital margin is worse for patients under Medicare observation care.5 Yet hospitals are obligated to be compliant with CMS observation regulations and may try to avoid the consequences (eg, audits, non-payment) for inpatient stays that are deemed inappropriate by CMS.

While the nuances of how CMS finances observation stays have made the practice controversial, the use of observation care in other payer groups that may not have the same reimbursement policies, and its impact on patients, have not been well studied. In this issue of the Journal of Hospital Medicine, Nuckols et al.6 begins to address this gap by carefully exploring trends in observation stays in a multipayer data set.

The authors use data for four states (Georgia, Nebraska, South Carolina, and Tennessee) from the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project (Agency for Healthcare Quality and Research) and the American Community Survey (US Census Bureau) to calculate population based rates of ED visits, observation stays, and inpatient admissions. To date, this is the first study to examine and compare the use of observation stays in an all-payer data set. Similar to prior work that examined the Medicare population, the authors find increased rates of treat-and-release ED visits and observation stays over time with a corresponding decline in inpatient admissions. As this study clearly shows, observation stays are comprising a greater fraction of the total hospital care delivered to patients with acute illnesses.

In many ways, the findings of Nuckols et al.6 raise more questions than they answer. For example, does the rise in observation stays represent a fundamental shift in how hospitals deliver care, an alternative to costly inpatient admissions? Are changing payer incentives driving hospitals to be more prudent in their inpatient admission practices, or are similar services simply being delivered under a new billing designation? And, most important, does this shift have any repercussions for the quality and safety of patient care?

Ultimately, the answer to these questions is, “It depends.” As the authors mention, most US hospitals admit observation patients to general medical wards, where they receive care at the admitting provider’s discretion instead of utilizing specific care pathways or observation protocols.7 In some of these hospitals, there may be little to no difference in how the observation patient is treated compared with a similar patient who is hospitalized as an inpatient.

However, a minority of hospitals has been more strategic in their delivery of observation care and have developed observation units. While observation units vary in design, common features include a dedicated location in the hospital with dedicated staff, reliance on clear inclusion-exclusion criteria for admission to the unit, and the use of rapid diagnostic or treatment protocols for a limited number of conditions. About half of these observation units are ED-based, reducing transitions of care between services. Protocol-driven observation units have the potential to prevent unnecessary inpatient admissions, standardize evidence-based practice, and reduce practice variation and resource use, apparently without increasing adverse events.8 In addition, they may also lead to better experiences of care for many patients compared with inpatient admissions.

Medicare’s own policy on observation hospital care succinctly describes ED observation units: “Observation services are commonly ordered for patients who present to the emergency department and who then require a significant period of treatment in order to make a decision concerning their admission or discharge…usually in less than 24 hours.” Due to regulatory changes and auditing pressure, observation care has expanded beyond this definition in length of stay, scope, and practice such that much of observation care now occurs on general hospital wards. Ideally, observation policy must be realigned with its original intent and investment made in ED observation units.