User login

Unhealthy drug use: How to screen, when to intervene

› Implement screening and brief intervention (SBI) for unhealthy drug use among adults in primary care. C

› Consult the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s Screening for Drug Use in General Medical Settings Resource Guide for step-by-step recommendations for implementing a drug SBI. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Joe M, age 54, comes to your office for his annual physical examination. As part of your routine screening, you ask him, “In the past year, how often have you used alcohol, tobacco, prescription drugs for nonmedical reasons, or illegal drugs?” Mr. M replies that he does not use tobacco and has not used prescription drugs for nonmedical reasons, but drinks alcohol weekly and uses cannabis and cocaine monthly.

If Mr. M were your patient, what would your next steps be?

One promising approach to alleviate substance use problems is screening and brief intervention (SBI), and—when appropriate—referral to an addiction treatment program. With strong evidence of efficacy, alcohol and tobacco SBIs have become recommended “usual” care for adults in primary care settings.1,2 Strategies for applying SBI to unhealthy drug use (“drug” SBI) in primary care have been a natural extension of the evidence that supports alcohol and tobacco SBIs.

Screening for unhealthy drug use consists of a quick risk appraisal, typically via a brief questionnaire.3-5 Patients with a positive screen then receive a more detailed assessment to estimate the extent of their substance use and severity of its consequences. If appropriate, this is followed with a brief intervention (BI), which is a time-limited, patient-centered counseling session designed to reduce substance use and/or related harm.4-6

So how can you make use of a drug SBI in your office setting?

Drug screening: What the evidence says

Currently, evidence on drug SBI is limited. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against universal drug SBI.4,7,8 The scarcity of validated screening and assessment tools that are brief enough to be used in primary care, patients’ use of multiple drugs, and confidentiality concerns likely contribute to the relative lack of research in this area.3,6,9

To our knowledge, results of only 5 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of drug SBI that included universal screening have been published in English. Here is what these researchers found:

Bernstein et al10 investigated the efficacy of SBI for cocaine and heroin use among 23,699 adults in urgent care, women’s health, and homeless clinic settings. They randomized 1175 patients who screened positive on the Drug Abuse Screening Test11 to receive a single BI session or a handout. At 6 months, patients in the BI group were 1.5 times more likely than controls to be abstinent from cocaine (22% vs 17%; P=.045) and heroin (40% vs 31%; P=.050).

Zahradnik et al12 examined the efficacy of SBI in reducing the use of potentially addictive prescription drugs by hospitalized patients. After researchers screened 6000 inpatients, 126 patients who used, abused, or were dependent on prescription medications were randomized to receive 2 BI sessions or an information booklet. At 3 months, 52% of patients in the BI group had a ≥25% reduction in their daily doses of prescription drugs, compared to 30% in the control group (P=.017),12 However, this difference was not maintained at 12 months.13

Humeniuk et al14 evaluated the efficacy of SBI among primary care patients ages 16 to 62 years in Australia, Brazil, India, and the United States who used cannabis, cocaine, amphetamines, or opioids. Patients were screened and assessed using the World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST).15 Patients whose scores indicated they had a moderate risk for problem use (N=731) were randomly assigned to receive a BI or usual care. At 3 months, patients in the BI group reported a reduction in total score for “illicit substance involvement” compared to controls (P<.001). However, country-specific analyses found that BI did not have a statistically significant effect on drug use by those in the United States (N=218), possibly due to protocol differences and a greater exposure to previous substance use treatment among US patients.14

Saitz et al16 investigated the efficacy of drug SBI among primary care patients (N=528) who had been screened using the ASSIST. The most commonly used drugs were marijuana (63% of patients), cocaine (19%), and opioids (17%). Patients were randomly assigned to a 10- to 15-minute BI, a 30- to 45-minute intervention, or no intervention. BI did not show efficacy for decreasing drug use at 6-month follow-up.

Roy-Byrne et al17 screened 10,337 primary care patients of “safety net” clinics serving low-income populations. Of 1621 patients who screened positive for problem drug use, 868 were enrolled and randomly assigned to either a BI group (one-time BI using motivational interviewing, a telephone booster session, and a handout, which included relevant drug-use related information and a list of substance abuse resources) or enhanced care as usual (usual care plus a handout). Over 12 months of follow-up, there were no differences between groups in drug use or related consequences. However, a subgroup analysis suggested that compared to enhanced usual care, BI may help reduce emergency department use and increase admissions to specialized drug treatment programs among those with severe drug problems.

In addition to these 5 RCTs, a large, prospective, uncontrolled trial looked at the efficacy of drug BI among 459,599 patients from various medical settings, including primary care.18 Twenty-three percent of patients screened positive for illicit drug use and were recommended BI (16%), brief treatment (3%) or specialty treatment (4%). At a 6-month follow-up, drug use among these patients decreased by 68% and heavy alcohol use decreased by 39% (P<.001). In addition, general health, mental health, employment, housing status, and criminal behavior improved among patients recommended for brief or specialty treatments (P<.001). Although this trial lent support for the efficacy of drug SBI in primary care, it was limited by the lack of a control group and low follow-up rates at some sites.

A step-by-step approach to drug screening

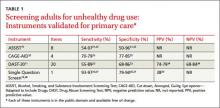

Although a variety of instruments can be used to screen and assess patients for unhealthy drug use, few have been validated in primary care (TABLE 1).11,15,19-27 Despite limited evidence, multiple professional organizations, including the American Academy of Family Physicians28 and the American Psychiatric Association,26 support routine implementation of drug SBI in primary care.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)’s Screening for Drug Use in General Medical Settings Resource Guide19 provides a step-by-step approach to drug SBI in primary care and other general medical settings. Primarily focused on drug SBI in adults, the NIDA guide details the use of the NIDA Quick Screen and the NIDA-Modified ASSIST (NM ASSIST). These tools are available as a PDF that you can print out and complete manually (http://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/ files/pdf/nmassist.pdf) or as a series of forms you can complete online (http://www.drugabuse.gov/nmassist). The NIDA guide also conveniently incorporates links to alcohol and tobacco SBI recommendations.

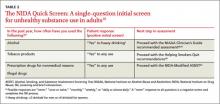

What to ask first. Following the NIDA algorithm, first screen patients with the Quick Screen, which consists of a single question about substance use: “In the past year, how often have you used alcohol, tobacco products, prescription drugs for nonmedical reasons, or illegal drugs?" (TABLE 2).19,29-32

A negative Quick Screen (a “never” response for all substances) completes the process. Patients with a negative screen should be praised and encouraged to continue their healthy lifestyle, then rescreened annually.

For patients who respond “Yes” to heavy drinking or any tobacco use, the NIDA guide recommends proceeding with an alcohol29 or tobacco30 SBI, respectively, and provides links to appropriate resources (TABLE 2).19,29-32 Those who screen positive for drugs (“Yes” to any drug use in the past year) should receive a detailed assessment using the NM ASSIST32 to determine their risk level for developing a substance use disorder. The NM ASSIST includes 8 questions about the patient’s desire for, use of, and problems related to the use of a wide range of drugs, including cannabis, cocaine, methamphetamine, hallucinogens, and other substances (eg, “In the past 3 months, how often have you used the following substances?” “How often have you had a strong desire or urge to use this substance?” “How often has your use of this substance led to health, social, legal or financial problems?”). The score on the NM ASSIST is used to calculate the patient’s risk level as low, moderate, or high.

For patients who use more than one drug, this risk level is scored separately for each drug and may differ from drug to drug. Multi-drug assessment can become time-consuming and may not be appropriate in some patients, especially if time is an issue (eg, the patient would like to focus on other concerns) or the patient is not interested in addressing certain drugs. In general, the decision about which substances to address should be clinically-driven, tailored to the needs of an individual patient. Focusing on the substance with the highest risk score or associated with the patient’s expressed greatest motivation to change may produce the best results.

CASE › Based on Mr. M’s response to your Quick Screen indicating he drinks alcohol and uses illicit drugs, you administer the NM ASSIST to perform a detailed assessment. His answer to a screening question for problematic alcohol use is negative (In the past year, he has not had >4 drinks in a day). Next, you calculate his NM ASSIST-based risk scores for cannabis and cocaine, and determine he is at moderate risk for developing problems due to cannabis use and at high risk for developing problems based on his use of cocaine. You also note Mr. M’s blood pressure (BP) is elevated (155/90 mm hg).

Conducting a brief intervention

Depending on the patient’s risk level for developing a substance use disorder, he or she should receive either brief advice (for those at low risk) or a BI (for those at moderate or high risk) and, if needed, a referral to treatment. Two popular approaches are FRAMES (Feedback, Responsibility, Advice, Menu of Strategies, Empathy, Self-efficacy) and the NIDA-recommended 5 As intervention. The latter approach entails Asking the patient about his drug use (via the Quick Screen); Advising the patient about his drug use by providing specific medical advice on why he should stop or cut down, and how; Assessing the patient’s readiness to quit or reduce use; Assisting the patient in making a change by creating a plan with specific goals; and Arranging a follow-up visit or specialty assessment and treatment by making referrals as appropriate.19

What about children and adolescents? Implementing a drug SBI in young patients often entails overcoming unique challenges and ethical dilemmas. Although the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends SBI for unhealthy drug and alcohol use among children and adolescents,33,34 the USPSTF did not find sufficient evidence to recommend the practice.1,8,35 Screening for drug use in minors often is complicated by questions about the age at which to start routine screening and issues related to confidentiality and parental involvement. The Center for Adolescent Health and the Law and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism provide useful resources related to youth SBI, including guidance on when to consider breeching a child’s confidentiality by engaging parents or guardians (TABLE 3).

TABLE 3

Resources

NIDA Resource Guide NIDA-Modified ASSIST Coding for SBI reimbursement SAMHSA’s Treatment Services Locator NIDA’s List of Community Treatment Programs SAMHSA Opioid Overdose Toolkit Buprenorphine training program Center for Adolescent Health and the Law NIAAA Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention for Youth |

Help is available for securing treatment, reimbursement

In addition to NIDA, many other organizations offer resources to assist clinicians in using drug SBI and helping patients obtain treatment (TABLE 3). For reimbursement, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has adopted billing codes for SBI services.36,37 The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)’s Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator and NIDA’s National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network List of Associated Community Treatment Programs can assist clinicians and patients in finding specialty treatment programs. Self-help groups such as Narcotics Anonymous, Alcoholic Anonymous, or Self-Managment and Recovery Training may help alleviate problems related to insurance coverage, location, and/or timing of services.

SAMHSA’s Opioid Overdose Toolkit provides guidance to clinicians and patients on ways to reduce the risk of overdose. Physicians also can complete a short training program in office-based buprenorphine maintenance therapy to provide evidence-based care to patients with opioid dependence; more details about this program are available from http://www.buppractice.com.

CASE › You decide to use the 5 as intervention with Mr. M. You explain to him that he is at high risk of developing a substance use disorder. You also discuss his elevated BP and the possible negative effects of drug use, especially cocaine, on BP. You advise him that medically it is in his best interest to stop using cocaine and stop or reduce using cannabis. When you ask Mr. M about his readiness to change his drug use, he expresses moderate interest in stopping cocaine but is not willing to reduce his cannabis use. At this time, he is not willing to discuss these issues further (“I’ll think about that”) or create a specific plan. You assure him of your ongoing support, provide him with resources on specialty treatment programs should he wish to consider those, and schedule a follow-up visit in 2 weeks to address BP and, if the patient agrees, drug use.

CORRESPONDENCE

Aleksandra Zgierska, MD, Phd, Department of Family Medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, 1100 Delaplaine Court, Madison, WI 53715-1896; [email protected]

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/ uspsdrin.htm. Accessed March 4, 2013.

2. US Preventive Services Task Force. Counseling and interventions to prevent tobacco use and tobacco-caused disease in adults and pregnant women. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspstbac2.htm. Accessed March 4, 2014.

3. Saitz R, Alford DP, Bernstein J, et al. Screening and brief intervention for unhealthy drug use in primary care settings: randomized clinical trials are needed. J Addict Med. 2010;4: 123-130.

4. Pilowsky DJ, Wu LT. Screening for alcohol and drug use disorders among adults in primary care: a review. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2012;3:25-34.

5. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Web site. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/ prevention/sbirt/. Accessed March 4, 2014.

6. Squires LE, Alford DP, Bernstein J, et al. Clinical case discussion: screening and brief intervention for drug use in primary care. J Addict Med. 2010;4:131-136.

7. Krupski A, Joesch JM, Dunn C, et al. Testing the effects of brief intervention in primary care for problem drug use in a randomized controlled trial: rationale, design, and methods. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2012;7:27.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for illicit drug use. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsdrug.htm. Accessed March 4, 2014.

9. Lanier D, Ko S. Screening in Primary Care Settings for Illicit Drug Use: Assessment of Screening Instruments—A Supplemental Evidence Update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. AHRQ Publication No. 08-05108-EF-2. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008.

10. Bernstein J, Bernstein E, Tassiopoulos K, et al. Brief motivational intervention at a clinic visit reduces cocaine and heroin use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:49-59.

11. Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addict Behav. 1982;7:363-371.

12. Zahradnik A, Otto C, Crackau B, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for problematic prescription drug use in non-treatment-seeking patients. Addiction. 2009;104:109-117.

13. Otto C, Crackau B, Löhrmann I, et al. Brief intervention in general hospital for problematic prescription drug use: 12-month outcome. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105:221-226.

14. Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor T, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for illicit drugs linked to the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) in clients recruited from primary health-care settings in four countries. Addiction. 2012;107:957-966.

15. WHO ASSIST Working Group. The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction. 2002;97:1183-1194.

16. Saitz R, Palfai TP, Cheng DM, et al. Screening and brief intervention for drug use in primary care: the Assessing Screening Plus brief Intervention’s Resulting Efficacy to stop drug use (ASPIRE) randomized trial. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2013;8(suppl 1):A61.

17. Roy-Byrne P, Bumgardner K, Krupski A, et al. Brief intervention for problem drug use in safety-net primary care settings: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(5):492-501.

18. Madras BK, Compton WM, Avula D, et al. Screening, brief interventions, referral to treatment (SBIRT) for illicit drug and alcohol use at multiple healthcare sites: comparison at intake and 6 months later. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:280-295.

19. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Resource guide: Screening for drug use in general medical settings. National Institute on Drug Abuse Web site. Available at: http://www.drugabuse. gov/publications/resource-guide. Accessed March 8, 2014.

20. Saitz R, Cheng DM, Allensworth-Davies D, et al. The ability of single screening questions for unhealthy alcohol and other drug use to identify substance dependence in primary care. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75:153-157.

21. Newcombe DA, Humeniuk RE, Ali R. Validation of the World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): report of results from the Australian site. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2005;24:217-226.

22. Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor TF, et al. Validation of the Alcohol, Smoking And Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST). Addiction. 2008;103:1039-1047.

23. Mdege ND, Lang J. Screening instruments for detecting illicit drug use/abuse that could be useful in general hospital wards: a systematic review. Addict Behav. 2011;36:1111-1119.

24. Cassidy CM, Schmitz N, Malla A. Validation of the alcohol use disorders identification test and the drug abuse screening test in first episode psychosis. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53:26-33.

25. Brown RL, Rounds LA. Conjoint screening questionnaires for alcohol and other drug abuse: criterion validity in a primary care practice. Wis Med J. 1995;94:135-140.

26. American Psychiatric Association. Position statement on substance use disorders. American Psychiatric Association Web site. Available at: http://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Advocacy%20and%20Newsroom/Position%20Statements/ps2012_Substance.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2014.

27. Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D, et al. A single-question screening test for drug use in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1155-1160.

28. American Academy of Family Physicians. Substance abuse and addiction. American Academy of Family Physicians Web site. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/substance-abuse.html. Accessed March 4, 2014.

29. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician’s guide. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Web site. Available at: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/clinicians_guide.htm. Accessed March 4, 2014.

30. US Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service. Helping smokers quit: A guide for clinicians. US Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service Web site. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/clinicians//clinhlpsmkqt/. Accessed March 4, 2014.

31. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. A Pocket Guide for Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Web site. Available at: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/pocketguide/pocket_guide.htm. Accessed July 30, 2014.

32. National Institute on Drug Abuse. NIDA-Quick Screen V1.0. National Institute on Drug Abuse Web site. Available at: http://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/nmassist.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2014.

33. Committee on Substance Abuse, Levy SJ, Kokotailo PK. Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e1330-e1340.

34. Kulig JW; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Substance Abuse. Tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs: the role of the pediatrician in prevention, identification, and management of substance abuse. Pediatrics. 2005;115:816-821.

35. US Preventive Services Task Force. Primary care behavioral interventions to reduce the nonmedical use of drugs in children and adolescents. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsnonmed.htm. Accessed March 4, 2014.

36. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) services. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/sbirt_factsheet_icn904084.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2014.

37. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Coding for screening and brief intervention reimbursement. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Web site. Available at: http://beta.samhsa.gov/sbirt/coding-reimbursement. Accessed August 4, 2014.

› Implement screening and brief intervention (SBI) for unhealthy drug use among adults in primary care. C

› Consult the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s Screening for Drug Use in General Medical Settings Resource Guide for step-by-step recommendations for implementing a drug SBI. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Joe M, age 54, comes to your office for his annual physical examination. As part of your routine screening, you ask him, “In the past year, how often have you used alcohol, tobacco, prescription drugs for nonmedical reasons, or illegal drugs?” Mr. M replies that he does not use tobacco and has not used prescription drugs for nonmedical reasons, but drinks alcohol weekly and uses cannabis and cocaine monthly.

If Mr. M were your patient, what would your next steps be?

One promising approach to alleviate substance use problems is screening and brief intervention (SBI), and—when appropriate—referral to an addiction treatment program. With strong evidence of efficacy, alcohol and tobacco SBIs have become recommended “usual” care for adults in primary care settings.1,2 Strategies for applying SBI to unhealthy drug use (“drug” SBI) in primary care have been a natural extension of the evidence that supports alcohol and tobacco SBIs.

Screening for unhealthy drug use consists of a quick risk appraisal, typically via a brief questionnaire.3-5 Patients with a positive screen then receive a more detailed assessment to estimate the extent of their substance use and severity of its consequences. If appropriate, this is followed with a brief intervention (BI), which is a time-limited, patient-centered counseling session designed to reduce substance use and/or related harm.4-6

So how can you make use of a drug SBI in your office setting?

Drug screening: What the evidence says

Currently, evidence on drug SBI is limited. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against universal drug SBI.4,7,8 The scarcity of validated screening and assessment tools that are brief enough to be used in primary care, patients’ use of multiple drugs, and confidentiality concerns likely contribute to the relative lack of research in this area.3,6,9

To our knowledge, results of only 5 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of drug SBI that included universal screening have been published in English. Here is what these researchers found:

Bernstein et al10 investigated the efficacy of SBI for cocaine and heroin use among 23,699 adults in urgent care, women’s health, and homeless clinic settings. They randomized 1175 patients who screened positive on the Drug Abuse Screening Test11 to receive a single BI session or a handout. At 6 months, patients in the BI group were 1.5 times more likely than controls to be abstinent from cocaine (22% vs 17%; P=.045) and heroin (40% vs 31%; P=.050).

Zahradnik et al12 examined the efficacy of SBI in reducing the use of potentially addictive prescription drugs by hospitalized patients. After researchers screened 6000 inpatients, 126 patients who used, abused, or were dependent on prescription medications were randomized to receive 2 BI sessions or an information booklet. At 3 months, 52% of patients in the BI group had a ≥25% reduction in their daily doses of prescription drugs, compared to 30% in the control group (P=.017),12 However, this difference was not maintained at 12 months.13

Humeniuk et al14 evaluated the efficacy of SBI among primary care patients ages 16 to 62 years in Australia, Brazil, India, and the United States who used cannabis, cocaine, amphetamines, or opioids. Patients were screened and assessed using the World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST).15 Patients whose scores indicated they had a moderate risk for problem use (N=731) were randomly assigned to receive a BI or usual care. At 3 months, patients in the BI group reported a reduction in total score for “illicit substance involvement” compared to controls (P<.001). However, country-specific analyses found that BI did not have a statistically significant effect on drug use by those in the United States (N=218), possibly due to protocol differences and a greater exposure to previous substance use treatment among US patients.14

Saitz et al16 investigated the efficacy of drug SBI among primary care patients (N=528) who had been screened using the ASSIST. The most commonly used drugs were marijuana (63% of patients), cocaine (19%), and opioids (17%). Patients were randomly assigned to a 10- to 15-minute BI, a 30- to 45-minute intervention, or no intervention. BI did not show efficacy for decreasing drug use at 6-month follow-up.

Roy-Byrne et al17 screened 10,337 primary care patients of “safety net” clinics serving low-income populations. Of 1621 patients who screened positive for problem drug use, 868 were enrolled and randomly assigned to either a BI group (one-time BI using motivational interviewing, a telephone booster session, and a handout, which included relevant drug-use related information and a list of substance abuse resources) or enhanced care as usual (usual care plus a handout). Over 12 months of follow-up, there were no differences between groups in drug use or related consequences. However, a subgroup analysis suggested that compared to enhanced usual care, BI may help reduce emergency department use and increase admissions to specialized drug treatment programs among those with severe drug problems.

In addition to these 5 RCTs, a large, prospective, uncontrolled trial looked at the efficacy of drug BI among 459,599 patients from various medical settings, including primary care.18 Twenty-three percent of patients screened positive for illicit drug use and were recommended BI (16%), brief treatment (3%) or specialty treatment (4%). At a 6-month follow-up, drug use among these patients decreased by 68% and heavy alcohol use decreased by 39% (P<.001). In addition, general health, mental health, employment, housing status, and criminal behavior improved among patients recommended for brief or specialty treatments (P<.001). Although this trial lent support for the efficacy of drug SBI in primary care, it was limited by the lack of a control group and low follow-up rates at some sites.

A step-by-step approach to drug screening

Although a variety of instruments can be used to screen and assess patients for unhealthy drug use, few have been validated in primary care (TABLE 1).11,15,19-27 Despite limited evidence, multiple professional organizations, including the American Academy of Family Physicians28 and the American Psychiatric Association,26 support routine implementation of drug SBI in primary care.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)’s Screening for Drug Use in General Medical Settings Resource Guide19 provides a step-by-step approach to drug SBI in primary care and other general medical settings. Primarily focused on drug SBI in adults, the NIDA guide details the use of the NIDA Quick Screen and the NIDA-Modified ASSIST (NM ASSIST). These tools are available as a PDF that you can print out and complete manually (http://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/ files/pdf/nmassist.pdf) or as a series of forms you can complete online (http://www.drugabuse.gov/nmassist). The NIDA guide also conveniently incorporates links to alcohol and tobacco SBI recommendations.

What to ask first. Following the NIDA algorithm, first screen patients with the Quick Screen, which consists of a single question about substance use: “In the past year, how often have you used alcohol, tobacco products, prescription drugs for nonmedical reasons, or illegal drugs?" (TABLE 2).19,29-32

A negative Quick Screen (a “never” response for all substances) completes the process. Patients with a negative screen should be praised and encouraged to continue their healthy lifestyle, then rescreened annually.

For patients who respond “Yes” to heavy drinking or any tobacco use, the NIDA guide recommends proceeding with an alcohol29 or tobacco30 SBI, respectively, and provides links to appropriate resources (TABLE 2).19,29-32 Those who screen positive for drugs (“Yes” to any drug use in the past year) should receive a detailed assessment using the NM ASSIST32 to determine their risk level for developing a substance use disorder. The NM ASSIST includes 8 questions about the patient’s desire for, use of, and problems related to the use of a wide range of drugs, including cannabis, cocaine, methamphetamine, hallucinogens, and other substances (eg, “In the past 3 months, how often have you used the following substances?” “How often have you had a strong desire or urge to use this substance?” “How often has your use of this substance led to health, social, legal or financial problems?”). The score on the NM ASSIST is used to calculate the patient’s risk level as low, moderate, or high.

For patients who use more than one drug, this risk level is scored separately for each drug and may differ from drug to drug. Multi-drug assessment can become time-consuming and may not be appropriate in some patients, especially if time is an issue (eg, the patient would like to focus on other concerns) or the patient is not interested in addressing certain drugs. In general, the decision about which substances to address should be clinically-driven, tailored to the needs of an individual patient. Focusing on the substance with the highest risk score or associated with the patient’s expressed greatest motivation to change may produce the best results.

CASE › Based on Mr. M’s response to your Quick Screen indicating he drinks alcohol and uses illicit drugs, you administer the NM ASSIST to perform a detailed assessment. His answer to a screening question for problematic alcohol use is negative (In the past year, he has not had >4 drinks in a day). Next, you calculate his NM ASSIST-based risk scores for cannabis and cocaine, and determine he is at moderate risk for developing problems due to cannabis use and at high risk for developing problems based on his use of cocaine. You also note Mr. M’s blood pressure (BP) is elevated (155/90 mm hg).

Conducting a brief intervention

Depending on the patient’s risk level for developing a substance use disorder, he or she should receive either brief advice (for those at low risk) or a BI (for those at moderate or high risk) and, if needed, a referral to treatment. Two popular approaches are FRAMES (Feedback, Responsibility, Advice, Menu of Strategies, Empathy, Self-efficacy) and the NIDA-recommended 5 As intervention. The latter approach entails Asking the patient about his drug use (via the Quick Screen); Advising the patient about his drug use by providing specific medical advice on why he should stop or cut down, and how; Assessing the patient’s readiness to quit or reduce use; Assisting the patient in making a change by creating a plan with specific goals; and Arranging a follow-up visit or specialty assessment and treatment by making referrals as appropriate.19

What about children and adolescents? Implementing a drug SBI in young patients often entails overcoming unique challenges and ethical dilemmas. Although the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends SBI for unhealthy drug and alcohol use among children and adolescents,33,34 the USPSTF did not find sufficient evidence to recommend the practice.1,8,35 Screening for drug use in minors often is complicated by questions about the age at which to start routine screening and issues related to confidentiality and parental involvement. The Center for Adolescent Health and the Law and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism provide useful resources related to youth SBI, including guidance on when to consider breeching a child’s confidentiality by engaging parents or guardians (TABLE 3).

TABLE 3

Resources

NIDA Resource Guide NIDA-Modified ASSIST Coding for SBI reimbursement SAMHSA’s Treatment Services Locator NIDA’s List of Community Treatment Programs SAMHSA Opioid Overdose Toolkit Buprenorphine training program Center for Adolescent Health and the Law NIAAA Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention for Youth |

Help is available for securing treatment, reimbursement

In addition to NIDA, many other organizations offer resources to assist clinicians in using drug SBI and helping patients obtain treatment (TABLE 3). For reimbursement, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has adopted billing codes for SBI services.36,37 The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)’s Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator and NIDA’s National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network List of Associated Community Treatment Programs can assist clinicians and patients in finding specialty treatment programs. Self-help groups such as Narcotics Anonymous, Alcoholic Anonymous, or Self-Managment and Recovery Training may help alleviate problems related to insurance coverage, location, and/or timing of services.

SAMHSA’s Opioid Overdose Toolkit provides guidance to clinicians and patients on ways to reduce the risk of overdose. Physicians also can complete a short training program in office-based buprenorphine maintenance therapy to provide evidence-based care to patients with opioid dependence; more details about this program are available from http://www.buppractice.com.

CASE › You decide to use the 5 as intervention with Mr. M. You explain to him that he is at high risk of developing a substance use disorder. You also discuss his elevated BP and the possible negative effects of drug use, especially cocaine, on BP. You advise him that medically it is in his best interest to stop using cocaine and stop or reduce using cannabis. When you ask Mr. M about his readiness to change his drug use, he expresses moderate interest in stopping cocaine but is not willing to reduce his cannabis use. At this time, he is not willing to discuss these issues further (“I’ll think about that”) or create a specific plan. You assure him of your ongoing support, provide him with resources on specialty treatment programs should he wish to consider those, and schedule a follow-up visit in 2 weeks to address BP and, if the patient agrees, drug use.

CORRESPONDENCE

Aleksandra Zgierska, MD, Phd, Department of Family Medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, 1100 Delaplaine Court, Madison, WI 53715-1896; [email protected]

› Implement screening and brief intervention (SBI) for unhealthy drug use among adults in primary care. C

› Consult the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s Screening for Drug Use in General Medical Settings Resource Guide for step-by-step recommendations for implementing a drug SBI. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE › Joe M, age 54, comes to your office for his annual physical examination. As part of your routine screening, you ask him, “In the past year, how often have you used alcohol, tobacco, prescription drugs for nonmedical reasons, or illegal drugs?” Mr. M replies that he does not use tobacco and has not used prescription drugs for nonmedical reasons, but drinks alcohol weekly and uses cannabis and cocaine monthly.

If Mr. M were your patient, what would your next steps be?

One promising approach to alleviate substance use problems is screening and brief intervention (SBI), and—when appropriate—referral to an addiction treatment program. With strong evidence of efficacy, alcohol and tobacco SBIs have become recommended “usual” care for adults in primary care settings.1,2 Strategies for applying SBI to unhealthy drug use (“drug” SBI) in primary care have been a natural extension of the evidence that supports alcohol and tobacco SBIs.

Screening for unhealthy drug use consists of a quick risk appraisal, typically via a brief questionnaire.3-5 Patients with a positive screen then receive a more detailed assessment to estimate the extent of their substance use and severity of its consequences. If appropriate, this is followed with a brief intervention (BI), which is a time-limited, patient-centered counseling session designed to reduce substance use and/or related harm.4-6

So how can you make use of a drug SBI in your office setting?

Drug screening: What the evidence says

Currently, evidence on drug SBI is limited. The US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) found insufficient evidence to recommend for or against universal drug SBI.4,7,8 The scarcity of validated screening and assessment tools that are brief enough to be used in primary care, patients’ use of multiple drugs, and confidentiality concerns likely contribute to the relative lack of research in this area.3,6,9

To our knowledge, results of only 5 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of drug SBI that included universal screening have been published in English. Here is what these researchers found:

Bernstein et al10 investigated the efficacy of SBI for cocaine and heroin use among 23,699 adults in urgent care, women’s health, and homeless clinic settings. They randomized 1175 patients who screened positive on the Drug Abuse Screening Test11 to receive a single BI session or a handout. At 6 months, patients in the BI group were 1.5 times more likely than controls to be abstinent from cocaine (22% vs 17%; P=.045) and heroin (40% vs 31%; P=.050).

Zahradnik et al12 examined the efficacy of SBI in reducing the use of potentially addictive prescription drugs by hospitalized patients. After researchers screened 6000 inpatients, 126 patients who used, abused, or were dependent on prescription medications were randomized to receive 2 BI sessions or an information booklet. At 3 months, 52% of patients in the BI group had a ≥25% reduction in their daily doses of prescription drugs, compared to 30% in the control group (P=.017),12 However, this difference was not maintained at 12 months.13

Humeniuk et al14 evaluated the efficacy of SBI among primary care patients ages 16 to 62 years in Australia, Brazil, India, and the United States who used cannabis, cocaine, amphetamines, or opioids. Patients were screened and assessed using the World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking, and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST).15 Patients whose scores indicated they had a moderate risk for problem use (N=731) were randomly assigned to receive a BI or usual care. At 3 months, patients in the BI group reported a reduction in total score for “illicit substance involvement” compared to controls (P<.001). However, country-specific analyses found that BI did not have a statistically significant effect on drug use by those in the United States (N=218), possibly due to protocol differences and a greater exposure to previous substance use treatment among US patients.14

Saitz et al16 investigated the efficacy of drug SBI among primary care patients (N=528) who had been screened using the ASSIST. The most commonly used drugs were marijuana (63% of patients), cocaine (19%), and opioids (17%). Patients were randomly assigned to a 10- to 15-minute BI, a 30- to 45-minute intervention, or no intervention. BI did not show efficacy for decreasing drug use at 6-month follow-up.

Roy-Byrne et al17 screened 10,337 primary care patients of “safety net” clinics serving low-income populations. Of 1621 patients who screened positive for problem drug use, 868 were enrolled and randomly assigned to either a BI group (one-time BI using motivational interviewing, a telephone booster session, and a handout, which included relevant drug-use related information and a list of substance abuse resources) or enhanced care as usual (usual care plus a handout). Over 12 months of follow-up, there were no differences between groups in drug use or related consequences. However, a subgroup analysis suggested that compared to enhanced usual care, BI may help reduce emergency department use and increase admissions to specialized drug treatment programs among those with severe drug problems.

In addition to these 5 RCTs, a large, prospective, uncontrolled trial looked at the efficacy of drug BI among 459,599 patients from various medical settings, including primary care.18 Twenty-three percent of patients screened positive for illicit drug use and were recommended BI (16%), brief treatment (3%) or specialty treatment (4%). At a 6-month follow-up, drug use among these patients decreased by 68% and heavy alcohol use decreased by 39% (P<.001). In addition, general health, mental health, employment, housing status, and criminal behavior improved among patients recommended for brief or specialty treatments (P<.001). Although this trial lent support for the efficacy of drug SBI in primary care, it was limited by the lack of a control group and low follow-up rates at some sites.

A step-by-step approach to drug screening

Although a variety of instruments can be used to screen and assess patients for unhealthy drug use, few have been validated in primary care (TABLE 1).11,15,19-27 Despite limited evidence, multiple professional organizations, including the American Academy of Family Physicians28 and the American Psychiatric Association,26 support routine implementation of drug SBI in primary care.

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA)’s Screening for Drug Use in General Medical Settings Resource Guide19 provides a step-by-step approach to drug SBI in primary care and other general medical settings. Primarily focused on drug SBI in adults, the NIDA guide details the use of the NIDA Quick Screen and the NIDA-Modified ASSIST (NM ASSIST). These tools are available as a PDF that you can print out and complete manually (http://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/ files/pdf/nmassist.pdf) or as a series of forms you can complete online (http://www.drugabuse.gov/nmassist). The NIDA guide also conveniently incorporates links to alcohol and tobacco SBI recommendations.

What to ask first. Following the NIDA algorithm, first screen patients with the Quick Screen, which consists of a single question about substance use: “In the past year, how often have you used alcohol, tobacco products, prescription drugs for nonmedical reasons, or illegal drugs?" (TABLE 2).19,29-32

A negative Quick Screen (a “never” response for all substances) completes the process. Patients with a negative screen should be praised and encouraged to continue their healthy lifestyle, then rescreened annually.

For patients who respond “Yes” to heavy drinking or any tobacco use, the NIDA guide recommends proceeding with an alcohol29 or tobacco30 SBI, respectively, and provides links to appropriate resources (TABLE 2).19,29-32 Those who screen positive for drugs (“Yes” to any drug use in the past year) should receive a detailed assessment using the NM ASSIST32 to determine their risk level for developing a substance use disorder. The NM ASSIST includes 8 questions about the patient’s desire for, use of, and problems related to the use of a wide range of drugs, including cannabis, cocaine, methamphetamine, hallucinogens, and other substances (eg, “In the past 3 months, how often have you used the following substances?” “How often have you had a strong desire or urge to use this substance?” “How often has your use of this substance led to health, social, legal or financial problems?”). The score on the NM ASSIST is used to calculate the patient’s risk level as low, moderate, or high.

For patients who use more than one drug, this risk level is scored separately for each drug and may differ from drug to drug. Multi-drug assessment can become time-consuming and may not be appropriate in some patients, especially if time is an issue (eg, the patient would like to focus on other concerns) or the patient is not interested in addressing certain drugs. In general, the decision about which substances to address should be clinically-driven, tailored to the needs of an individual patient. Focusing on the substance with the highest risk score or associated with the patient’s expressed greatest motivation to change may produce the best results.

CASE › Based on Mr. M’s response to your Quick Screen indicating he drinks alcohol and uses illicit drugs, you administer the NM ASSIST to perform a detailed assessment. His answer to a screening question for problematic alcohol use is negative (In the past year, he has not had >4 drinks in a day). Next, you calculate his NM ASSIST-based risk scores for cannabis and cocaine, and determine he is at moderate risk for developing problems due to cannabis use and at high risk for developing problems based on his use of cocaine. You also note Mr. M’s blood pressure (BP) is elevated (155/90 mm hg).

Conducting a brief intervention

Depending on the patient’s risk level for developing a substance use disorder, he or she should receive either brief advice (for those at low risk) or a BI (for those at moderate or high risk) and, if needed, a referral to treatment. Two popular approaches are FRAMES (Feedback, Responsibility, Advice, Menu of Strategies, Empathy, Self-efficacy) and the NIDA-recommended 5 As intervention. The latter approach entails Asking the patient about his drug use (via the Quick Screen); Advising the patient about his drug use by providing specific medical advice on why he should stop or cut down, and how; Assessing the patient’s readiness to quit or reduce use; Assisting the patient in making a change by creating a plan with specific goals; and Arranging a follow-up visit or specialty assessment and treatment by making referrals as appropriate.19

What about children and adolescents? Implementing a drug SBI in young patients often entails overcoming unique challenges and ethical dilemmas. Although the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends SBI for unhealthy drug and alcohol use among children and adolescents,33,34 the USPSTF did not find sufficient evidence to recommend the practice.1,8,35 Screening for drug use in minors often is complicated by questions about the age at which to start routine screening and issues related to confidentiality and parental involvement. The Center for Adolescent Health and the Law and the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism provide useful resources related to youth SBI, including guidance on when to consider breeching a child’s confidentiality by engaging parents or guardians (TABLE 3).

TABLE 3

Resources

NIDA Resource Guide NIDA-Modified ASSIST Coding for SBI reimbursement SAMHSA’s Treatment Services Locator NIDA’s List of Community Treatment Programs SAMHSA Opioid Overdose Toolkit Buprenorphine training program Center for Adolescent Health and the Law NIAAA Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention for Youth |

Help is available for securing treatment, reimbursement

In addition to NIDA, many other organizations offer resources to assist clinicians in using drug SBI and helping patients obtain treatment (TABLE 3). For reimbursement, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services has adopted billing codes for SBI services.36,37 The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)’s Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator and NIDA’s National Drug Abuse Treatment Clinical Trials Network List of Associated Community Treatment Programs can assist clinicians and patients in finding specialty treatment programs. Self-help groups such as Narcotics Anonymous, Alcoholic Anonymous, or Self-Managment and Recovery Training may help alleviate problems related to insurance coverage, location, and/or timing of services.

SAMHSA’s Opioid Overdose Toolkit provides guidance to clinicians and patients on ways to reduce the risk of overdose. Physicians also can complete a short training program in office-based buprenorphine maintenance therapy to provide evidence-based care to patients with opioid dependence; more details about this program are available from http://www.buppractice.com.

CASE › You decide to use the 5 as intervention with Mr. M. You explain to him that he is at high risk of developing a substance use disorder. You also discuss his elevated BP and the possible negative effects of drug use, especially cocaine, on BP. You advise him that medically it is in his best interest to stop using cocaine and stop or reduce using cannabis. When you ask Mr. M about his readiness to change his drug use, he expresses moderate interest in stopping cocaine but is not willing to reduce his cannabis use. At this time, he is not willing to discuss these issues further (“I’ll think about that”) or create a specific plan. You assure him of your ongoing support, provide him with resources on specialty treatment programs should he wish to consider those, and schedule a follow-up visit in 2 weeks to address BP and, if the patient agrees, drug use.

CORRESPONDENCE

Aleksandra Zgierska, MD, Phd, Department of Family Medicine, University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, 1100 Delaplaine Court, Madison, WI 53715-1896; [email protected]

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/ uspsdrin.htm. Accessed March 4, 2013.

2. US Preventive Services Task Force. Counseling and interventions to prevent tobacco use and tobacco-caused disease in adults and pregnant women. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspstbac2.htm. Accessed March 4, 2014.

3. Saitz R, Alford DP, Bernstein J, et al. Screening and brief intervention for unhealthy drug use in primary care settings: randomized clinical trials are needed. J Addict Med. 2010;4: 123-130.

4. Pilowsky DJ, Wu LT. Screening for alcohol and drug use disorders among adults in primary care: a review. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2012;3:25-34.

5. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Web site. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/ prevention/sbirt/. Accessed March 4, 2014.

6. Squires LE, Alford DP, Bernstein J, et al. Clinical case discussion: screening and brief intervention for drug use in primary care. J Addict Med. 2010;4:131-136.

7. Krupski A, Joesch JM, Dunn C, et al. Testing the effects of brief intervention in primary care for problem drug use in a randomized controlled trial: rationale, design, and methods. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2012;7:27.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for illicit drug use. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsdrug.htm. Accessed March 4, 2014.

9. Lanier D, Ko S. Screening in Primary Care Settings for Illicit Drug Use: Assessment of Screening Instruments—A Supplemental Evidence Update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. AHRQ Publication No. 08-05108-EF-2. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008.

10. Bernstein J, Bernstein E, Tassiopoulos K, et al. Brief motivational intervention at a clinic visit reduces cocaine and heroin use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:49-59.

11. Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addict Behav. 1982;7:363-371.

12. Zahradnik A, Otto C, Crackau B, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for problematic prescription drug use in non-treatment-seeking patients. Addiction. 2009;104:109-117.

13. Otto C, Crackau B, Löhrmann I, et al. Brief intervention in general hospital for problematic prescription drug use: 12-month outcome. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105:221-226.

14. Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor T, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for illicit drugs linked to the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) in clients recruited from primary health-care settings in four countries. Addiction. 2012;107:957-966.

15. WHO ASSIST Working Group. The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction. 2002;97:1183-1194.

16. Saitz R, Palfai TP, Cheng DM, et al. Screening and brief intervention for drug use in primary care: the Assessing Screening Plus brief Intervention’s Resulting Efficacy to stop drug use (ASPIRE) randomized trial. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2013;8(suppl 1):A61.

17. Roy-Byrne P, Bumgardner K, Krupski A, et al. Brief intervention for problem drug use in safety-net primary care settings: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(5):492-501.

18. Madras BK, Compton WM, Avula D, et al. Screening, brief interventions, referral to treatment (SBIRT) for illicit drug and alcohol use at multiple healthcare sites: comparison at intake and 6 months later. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:280-295.

19. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Resource guide: Screening for drug use in general medical settings. National Institute on Drug Abuse Web site. Available at: http://www.drugabuse. gov/publications/resource-guide. Accessed March 8, 2014.

20. Saitz R, Cheng DM, Allensworth-Davies D, et al. The ability of single screening questions for unhealthy alcohol and other drug use to identify substance dependence in primary care. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75:153-157.

21. Newcombe DA, Humeniuk RE, Ali R. Validation of the World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): report of results from the Australian site. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2005;24:217-226.

22. Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor TF, et al. Validation of the Alcohol, Smoking And Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST). Addiction. 2008;103:1039-1047.

23. Mdege ND, Lang J. Screening instruments for detecting illicit drug use/abuse that could be useful in general hospital wards: a systematic review. Addict Behav. 2011;36:1111-1119.

24. Cassidy CM, Schmitz N, Malla A. Validation of the alcohol use disorders identification test and the drug abuse screening test in first episode psychosis. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53:26-33.

25. Brown RL, Rounds LA. Conjoint screening questionnaires for alcohol and other drug abuse: criterion validity in a primary care practice. Wis Med J. 1995;94:135-140.

26. American Psychiatric Association. Position statement on substance use disorders. American Psychiatric Association Web site. Available at: http://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Advocacy%20and%20Newsroom/Position%20Statements/ps2012_Substance.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2014.

27. Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D, et al. A single-question screening test for drug use in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1155-1160.

28. American Academy of Family Physicians. Substance abuse and addiction. American Academy of Family Physicians Web site. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/substance-abuse.html. Accessed March 4, 2014.

29. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician’s guide. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Web site. Available at: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/clinicians_guide.htm. Accessed March 4, 2014.

30. US Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service. Helping smokers quit: A guide for clinicians. US Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service Web site. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/clinicians//clinhlpsmkqt/. Accessed March 4, 2014.

31. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. A Pocket Guide for Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Web site. Available at: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/pocketguide/pocket_guide.htm. Accessed July 30, 2014.

32. National Institute on Drug Abuse. NIDA-Quick Screen V1.0. National Institute on Drug Abuse Web site. Available at: http://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/nmassist.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2014.

33. Committee on Substance Abuse, Levy SJ, Kokotailo PK. Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e1330-e1340.

34. Kulig JW; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Substance Abuse. Tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs: the role of the pediatrician in prevention, identification, and management of substance abuse. Pediatrics. 2005;115:816-821.

35. US Preventive Services Task Force. Primary care behavioral interventions to reduce the nonmedical use of drugs in children and adolescents. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsnonmed.htm. Accessed March 4, 2014.

36. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) services. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/sbirt_factsheet_icn904084.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2014.

37. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Coding for screening and brief intervention reimbursement. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Web site. Available at: http://beta.samhsa.gov/sbirt/coding-reimbursement. Accessed August 4, 2014.

1. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening and behavioral counseling interventions in primary care to reduce alcohol misuse. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/ uspsdrin.htm. Accessed March 4, 2013.

2. US Preventive Services Task Force. Counseling and interventions to prevent tobacco use and tobacco-caused disease in adults and pregnant women. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspstbac2.htm. Accessed March 4, 2014.

3. Saitz R, Alford DP, Bernstein J, et al. Screening and brief intervention for unhealthy drug use in primary care settings: randomized clinical trials are needed. J Addict Med. 2010;4: 123-130.

4. Pilowsky DJ, Wu LT. Screening for alcohol and drug use disorders among adults in primary care: a review. Subst Abuse Rehabil. 2012;3:25-34.

5. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT). Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Web site. Available at: http://www.samhsa.gov/ prevention/sbirt/. Accessed March 4, 2014.

6. Squires LE, Alford DP, Bernstein J, et al. Clinical case discussion: screening and brief intervention for drug use in primary care. J Addict Med. 2010;4:131-136.

7. Krupski A, Joesch JM, Dunn C, et al. Testing the effects of brief intervention in primary care for problem drug use in a randomized controlled trial: rationale, design, and methods. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2012;7:27.

8. US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for illicit drug use. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsdrug.htm. Accessed March 4, 2014.

9. Lanier D, Ko S. Screening in Primary Care Settings for Illicit Drug Use: Assessment of Screening Instruments—A Supplemental Evidence Update for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. AHRQ Publication No. 08-05108-EF-2. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; 2008.

10. Bernstein J, Bernstein E, Tassiopoulos K, et al. Brief motivational intervention at a clinic visit reduces cocaine and heroin use. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;77:49-59.

11. Skinner HA. The drug abuse screening test. Addict Behav. 1982;7:363-371.

12. Zahradnik A, Otto C, Crackau B, et al. Randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for problematic prescription drug use in non-treatment-seeking patients. Addiction. 2009;104:109-117.

13. Otto C, Crackau B, Löhrmann I, et al. Brief intervention in general hospital for problematic prescription drug use: 12-month outcome. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;105:221-226.

14. Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor T, et al. A randomized controlled trial of a brief intervention for illicit drugs linked to the Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) in clients recruited from primary health-care settings in four countries. Addiction. 2012;107:957-966.

15. WHO ASSIST Working Group. The Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): development, reliability and feasibility. Addiction. 2002;97:1183-1194.

16. Saitz R, Palfai TP, Cheng DM, et al. Screening and brief intervention for drug use in primary care: the Assessing Screening Plus brief Intervention’s Resulting Efficacy to stop drug use (ASPIRE) randomized trial. Addict Sci Clin Pract. 2013;8(suppl 1):A61.

17. Roy-Byrne P, Bumgardner K, Krupski A, et al. Brief intervention for problem drug use in safety-net primary care settings: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2014;312(5):492-501.

18. Madras BK, Compton WM, Avula D, et al. Screening, brief interventions, referral to treatment (SBIRT) for illicit drug and alcohol use at multiple healthcare sites: comparison at intake and 6 months later. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2009;99:280-295.

19. National Institute on Drug Abuse. Resource guide: Screening for drug use in general medical settings. National Institute on Drug Abuse Web site. Available at: http://www.drugabuse. gov/publications/resource-guide. Accessed March 8, 2014.

20. Saitz R, Cheng DM, Allensworth-Davies D, et al. The ability of single screening questions for unhealthy alcohol and other drug use to identify substance dependence in primary care. J Stud Alcohol Drugs. 2014;75:153-157.

21. Newcombe DA, Humeniuk RE, Ali R. Validation of the World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST): report of results from the Australian site. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2005;24:217-226.

22. Humeniuk R, Ali R, Babor TF, et al. Validation of the Alcohol, Smoking And Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST). Addiction. 2008;103:1039-1047.

23. Mdege ND, Lang J. Screening instruments for detecting illicit drug use/abuse that could be useful in general hospital wards: a systematic review. Addict Behav. 2011;36:1111-1119.

24. Cassidy CM, Schmitz N, Malla A. Validation of the alcohol use disorders identification test and the drug abuse screening test in first episode psychosis. Can J Psychiatry. 2008;53:26-33.

25. Brown RL, Rounds LA. Conjoint screening questionnaires for alcohol and other drug abuse: criterion validity in a primary care practice. Wis Med J. 1995;94:135-140.

26. American Psychiatric Association. Position statement on substance use disorders. American Psychiatric Association Web site. Available at: http://www.psychiatry.org/File%20Library/Advocacy%20and%20Newsroom/Position%20Statements/ps2012_Substance.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2014.

27. Smith PC, Schmidt SM, Allensworth-Davies D, et al. A single-question screening test for drug use in primary care. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:1155-1160.

28. American Academy of Family Physicians. Substance abuse and addiction. American Academy of Family Physicians Web site. Available at: http://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/substance-abuse.html. Accessed March 4, 2014.

29. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Helping patients who drink too much: A clinician’s guide. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Web site. Available at: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/CliniciansGuide2005/clinicians_guide.htm. Accessed March 4, 2014.

30. US Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service. Helping smokers quit: A guide for clinicians. US Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service Web site. Available at: http://www.ahrq.gov/professionals/clinicians-providers/guidelines-recommendations/tobacco/clinicians//clinhlpsmkqt/. Accessed March 4, 2014.

31. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. A Pocket Guide for Alcohol Screening and Brief Intervention. National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism Web site. Available at: http://pubs.niaaa.nih.gov/publications/Practitioner/pocketguide/pocket_guide.htm. Accessed July 30, 2014.

32. National Institute on Drug Abuse. NIDA-Quick Screen V1.0. National Institute on Drug Abuse Web site. Available at: http://www.drugabuse.gov/sites/default/files/pdf/nmassist.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2014.

33. Committee on Substance Abuse, Levy SJ, Kokotailo PK. Substance use screening, brief intervention, and referral to treatment for pediatricians. Pediatrics. 2011;128:e1330-e1340.

34. Kulig JW; American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Substance Abuse. Tobacco, alcohol, and other drugs: the role of the pediatrician in prevention, identification, and management of substance abuse. Pediatrics. 2005;115:816-821.

35. US Preventive Services Task Force. Primary care behavioral interventions to reduce the nonmedical use of drugs in children and adolescents. US Preventive Services Task Force Web site. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/uspsnonmed.htm. Accessed March 4, 2014.

36. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) services. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services Web site. Available at: http://www.cms.gov/Outreach-and-Education/Medicare-Learning-Network-MLN/MLNProducts/downloads/sbirt_factsheet_icn904084.pdf. Accessed March 4, 2014.

37. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. Coding for screening and brief intervention reimbursement. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Web site. Available at: http://beta.samhsa.gov/sbirt/coding-reimbursement. Accessed August 4, 2014.

Remission Of Alcohol Disorders In Primary Care Patients

METHODS: A total of 119 eligible and randomly selected primary care patients with alcohol abuse or dependence in remission (as defined in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, third edition, revised) participated in a semistructured telephone interview.

RESULTS: Of the subjects, 59.7% were women; 50.4% had been alcohol dependent; 66.3% made a conscious decision to modify their drinking; and 62.1%, including 54.2% of the alcohol-dependent subjects, moderated their drinking without abstaining. Family, emotional, and medical issues most often prompted reduced drinking. Nearly one third of the subjects found specific strategies and rules helpful in reducing their drinking, and many cited circumstances that helped or hindered their efforts. Only 10.9% had formal alcohol treatment.

CONCLUSIONS: A significant proportion of patients with AUDs remitted without formal treatment. Abstinence may not be necessary for a subset of dependent patients. When counseling patients with active AUDs, primary care clinicians are advised to counsel patients about the psychosocial and medical reasons to control drinking, promote rule-setting about drinking, help patients avoid circumstances that trigger drinking, and support patients’ attempts at moderating drinking rather than abstaining. Motivational interviewing (motivational enhancement therapy) may provide a useful framework for such counseling.

Alcohol use disorders (AUDs) are prevalent in primary care settings.1,2 Research has shown that appropriately trained primary care clinicians can use screening and brief intervention to identify and assist many patients with risky and problematic drinking.3,4 Clinicians are advised to refer all alcohol-dependent patients for formal specialized treatment. The traditional teaching is that alcohol-dependent patients must receive formal treatment and must abstain.

Recent studies have suggested that some alcohol-dependent patients remit spontaneously.5-12 The generalizability of these findings to general populations is unknown, since most of the studies used convenience sampling. Also, the applicability of these findings is unclear with regard to specific AUDs, since many of these studies used screening questionnaires rather than diagnostic assessments to classify subjects.

Our goal was to describe the phenomenology of remission for a randomly selected sample of primary care patients who had been diagnosed with alcohol abuse or had alcohol dependence in remission for at least 1 year. Specifically, we assessed patients’ decisions and reasons for modifying their drinking, their decisions regarding whether to cut down or abstain from drinking, the strategies and circumstances that helped or hindered their efforts, and the roles played by professionals in their process of change. Our results are intended to guide the treatment of AUDs in primary care settings.

Methods

Subjects

A total of 702 English-speaking primary care patients aged 18 to 59 years who were not pregnant were randomly selected from 3 family practice clinics to participate in a previous study.13 For the earlier study, all participants responded to the Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Substance Abuse Module, which assesses current and lifetime alcohol and other drug disorders with excellent reliability and validity.14-17 The response rate was 90.4%.

Subjects were eligible to participate in our study if they met the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, third edition, revised (DSM-III-R) criteria for alcohol abuse or alcohol dependence in remission. In the previous study, 217 (30.9%) of the 702 participants had these DSM-III-R diagnoses. Of those patients, 196 expressed a willingness to participate in further studies, and 179 could be reached. Of those 179, 3 were pregnant, 1 had died, 14 had relapsed, and 6 could not respond to many of the questions because they did not remember reducing their alcohol consumption. Of the 155 remaining eligible individuals, 119 (76.8%) agreed to participate. Demographic information is presented in Table 1.

Eligible subjects were invited to participate with a letter and a follow-up telephone call. Participants received $10 after completing a 30-minute telephone interview. The protocol was approved by the University of Wisconsin Center for Health Sciences human subjects committee.

Data Collection

Four research assistants were trained to administer semistructured telephone interviews. To enhance interrater reliability, the interviewers were trained together and frequently monitored; they also often listened to each other’s interviews. The interview protocol consisted of a sequence of closed-ended and open-ended questions. Initial questions assessed the subjects’ current quantity and frequency of alcohol use and alcohol-related diagnoses. They were asked whether they consciously decided to either quit or cut down on their drinking or if their level of drinking decreased without intention. Subjects were asked open-ended, somewhat redundant questions designed to elicit their reasons for quitting or cutting down. The remainder of the questions focused on how the subjects moderated their alcohol use Table 2.

Analysis

We entered and analyzed data using custom programs written in Microsoft Access (Microsoft, Redmond, Washington), a relational database which enabled us to classify the content of open-ended responses and to determine the frequency of common themes across questions. Microsoft Excel was used to calculate chi-square values according to Siegel’s formula.18

Results

The subjects were well distributed among the third through sixth decades of life Table 1. Women outnumbered men 3 to 2. Most subjects had private insurance, were well educated, and were married or remarried. The demographic attributes of the study subjects and the nonresponders were similar (chi-square tests, P >.05).

The subjects’ AUDs had been active for an average of 11.3 years (standard deviation [SD] =9.0 years, range=1-40 years). The disorders were in remission for an average of 11.1 years (SD=7.8 years, range=0-32 years). Subjects experienced their first alcohol-related symptoms at an average age of 19.3 (SD=5.4, range=10-50 years). The average age for their first attempt at quitting or cutting down was 27.5 years (SD=8.5 years, range=16-53 years). The average age for their most recent attempt at quitting or cutting down was 31.8 years (SD=10 years, range=16-56 years). The majority of subjects (57.9%; N=69) made only one attempt to quit or cut down; 32.7% (39) made 2 to 5 attempts; and 4.2% (11) made 6 or more attempts. One subject reported 20 attempts at quitting or cutting down; another reported 100 attempts. More than two thirds (N=81) of the subjects drank in the past month, and 79.8% (95) drank in the past year. Subjects who continued to drink did so on an average of 3.0 days in the past month (SD=4.4 days, range=0-30 days). Nearly half of the subjects (N=54) drank on 1 to 4 occasions in the last 30 days, and 31.9% (38) did not drink at all. Approximately half of the subjects (N=60) had alcohol dependence in remission, and half (59) had alcohol abuse in remission.

Table 2 shows subjects’ responses to many of the closed-ended questions of the study. Approximately two thirds (N=79) made a conscious decision to quit or cut down; for the remainder, the reduction in drinking occurred without intent.

Table 3 shows the subjects’ specific answers grouped by the major themes that emerged from our analysis of their responses. Within each theme, there were responses reflecting both positive and negative reasons to modify drinking. For example, one subject mentioned that he changed his drinking pattern to be a better role model to children; another stated that she changed because of family disapproval.

Thirty-six subjects initially planned to cut down on their drinking; the others attempted abstinence. A total of 10.9% (13) of the subjects underwent formal alcohol treatment, and an additional 1.7% (2) received help from other professionals. A total of 15.1% (18) attended self-help groups, such as Alcoholics Anonymous.

Thirty-six subjects identified at least one specific strategy that helped them modify their drinking. Thirteen mentioned that it was helpful to avoid bars and people who drink. Others mentioned that it was helpful to change their social activities (N=9), follow the rules of Alcoholics Anonymous (7), keep busy (6), and keep no alcohol at home (5). A total of 12.6% (N=15) tried strategies that did not prove helpful, such as limiting the occasions they went out (5), quitting “cold turkey” (3), avoiding peer pressure (2), and going to Alcoholics Anonymous meetings (2).

Nearly one third (N=39) of the subjects made rules for themselves about their drinking. The most frequently mentioned rules involved limitation. Examples were limits on the amount of alcohol permissible to consume on a particular occasion and limits on the number of days per week or times of the day in which drinking was allowed. Three of those who made rules failed at attempts to quit “cold turkey” by using will power or by “taking control.” Two subjects felt that the 12 steps and other rules of Alcoholics Anonymous were not helpful, and 2 felt that avoiding drinkers was not helpful.