User login

Emergency Imaging

Case

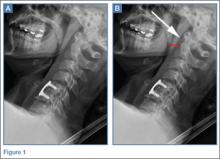

A 41-year-old woman presented to the ED with a 3-day history of posterior neck pain that radiated to the occipital region. The patient stated that the day prior to presentation, the pain had worsened to what she rated as a “9” on a pain scale of 0 to 10. The patient’s surgical history included a remote prior cervical fusion at C5-C6. A lateral radiograph of the cervical spine is shown above (Figure 1a).

What is the diagnosis? Is additional imaging necessary? If so, why?

Answer

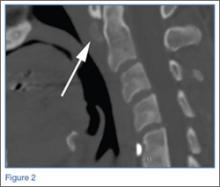

The lateral view of the cervical spine demonstrated soft tissue swelling in the upper prevertebral region (red arrowheads, Figure 1b). (The soft tissues at this level in an adult normally measure less than 3 mm between the airway and the vertebral body.) The radiograph also showed an area of calcification within the prevertebral soft tissues (white arrow, Figure 1b).

The patient denied fevers, chills, dysphagia, visual changes, and nasal congestion. Physical examination demonstrated tenderness to palpation of the posterior neck, but there was no evidence of palpable mass or lymphadenopathy. Neck extension and lateral movement to the left were severely limited due to pain; neck flexion and lateral movement range of motion to the right were mildly decreased due to pain. The physical examination was otherwise normal.

Longus colli (prevertebral) calcific tendinitis is a self-limiting condition that typically lasts 1 to 3 weeks, though it can be very painful during the acute phase.1,2 Treatment is typically conservative, and the patient in this case received a course of oral corticosteroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to help alleviate the associated inflammation.

Dr Bartolotta is an assistant professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City and assistant attending radiologist at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Dr Baradaran is a resident in the department of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center; and associate editor, imaging, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Coulier B, Macsim M, Desgain O. Retropharyngeal calcific tendinitis--longus colli tendinitis--an unusual cause of acute dysphagia. Emerg Radiol. 2011;18(5):449-451.

- Silva CF, Soffia PS, Pruzzo E. Acute prevertebral calcific tendinitis: a source of non-surgical acute cervical pain. Acta Radiologica. 2014;55(1):91-94.

- Zibis AH, Giannis D, Malizos KN, Kitsioulis P, Arvanitis DL. Acute calcific tendinitis of the longus colli muscle: case report and review of the literature. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(Suppl 3):S434-S438.

Case

A 41-year-old woman presented to the ED with a 3-day history of posterior neck pain that radiated to the occipital region. The patient stated that the day prior to presentation, the pain had worsened to what she rated as a “9” on a pain scale of 0 to 10. The patient’s surgical history included a remote prior cervical fusion at C5-C6. A lateral radiograph of the cervical spine is shown above (Figure 1a).

What is the diagnosis? Is additional imaging necessary? If so, why?

Answer

The lateral view of the cervical spine demonstrated soft tissue swelling in the upper prevertebral region (red arrowheads, Figure 1b). (The soft tissues at this level in an adult normally measure less than 3 mm between the airway and the vertebral body.) The radiograph also showed an area of calcification within the prevertebral soft tissues (white arrow, Figure 1b).

The patient denied fevers, chills, dysphagia, visual changes, and nasal congestion. Physical examination demonstrated tenderness to palpation of the posterior neck, but there was no evidence of palpable mass or lymphadenopathy. Neck extension and lateral movement to the left were severely limited due to pain; neck flexion and lateral movement range of motion to the right were mildly decreased due to pain. The physical examination was otherwise normal.

Longus colli (prevertebral) calcific tendinitis is a self-limiting condition that typically lasts 1 to 3 weeks, though it can be very painful during the acute phase.1,2 Treatment is typically conservative, and the patient in this case received a course of oral corticosteroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to help alleviate the associated inflammation.

Dr Bartolotta is an assistant professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City and assistant attending radiologist at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Dr Baradaran is a resident in the department of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center; and associate editor, imaging, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

Case

A 41-year-old woman presented to the ED with a 3-day history of posterior neck pain that radiated to the occipital region. The patient stated that the day prior to presentation, the pain had worsened to what she rated as a “9” on a pain scale of 0 to 10. The patient’s surgical history included a remote prior cervical fusion at C5-C6. A lateral radiograph of the cervical spine is shown above (Figure 1a).

What is the diagnosis? Is additional imaging necessary? If so, why?

Answer

The lateral view of the cervical spine demonstrated soft tissue swelling in the upper prevertebral region (red arrowheads, Figure 1b). (The soft tissues at this level in an adult normally measure less than 3 mm between the airway and the vertebral body.) The radiograph also showed an area of calcification within the prevertebral soft tissues (white arrow, Figure 1b).

The patient denied fevers, chills, dysphagia, visual changes, and nasal congestion. Physical examination demonstrated tenderness to palpation of the posterior neck, but there was no evidence of palpable mass or lymphadenopathy. Neck extension and lateral movement to the left were severely limited due to pain; neck flexion and lateral movement range of motion to the right were mildly decreased due to pain. The physical examination was otherwise normal.

Longus colli (prevertebral) calcific tendinitis is a self-limiting condition that typically lasts 1 to 3 weeks, though it can be very painful during the acute phase.1,2 Treatment is typically conservative, and the patient in this case received a course of oral corticosteroids and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs to help alleviate the associated inflammation.

Dr Bartolotta is an assistant professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City and assistant attending radiologist at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Dr Baradaran is a resident in the department of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center; and associate editor, imaging, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Coulier B, Macsim M, Desgain O. Retropharyngeal calcific tendinitis--longus colli tendinitis--an unusual cause of acute dysphagia. Emerg Radiol. 2011;18(5):449-451.

- Silva CF, Soffia PS, Pruzzo E. Acute prevertebral calcific tendinitis: a source of non-surgical acute cervical pain. Acta Radiologica. 2014;55(1):91-94.

- Zibis AH, Giannis D, Malizos KN, Kitsioulis P, Arvanitis DL. Acute calcific tendinitis of the longus colli muscle: case report and review of the literature. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(Suppl 3):S434-S438.

- Coulier B, Macsim M, Desgain O. Retropharyngeal calcific tendinitis--longus colli tendinitis--an unusual cause of acute dysphagia. Emerg Radiol. 2011;18(5):449-451.

- Silva CF, Soffia PS, Pruzzo E. Acute prevertebral calcific tendinitis: a source of non-surgical acute cervical pain. Acta Radiologica. 2014;55(1):91-94.

- Zibis AH, Giannis D, Malizos KN, Kitsioulis P, Arvanitis DL. Acute calcific tendinitis of the longus colli muscle: case report and review of the literature. Eur Spine J. 2013;22(Suppl 3):S434-S438.

Emergency Imaging

Case

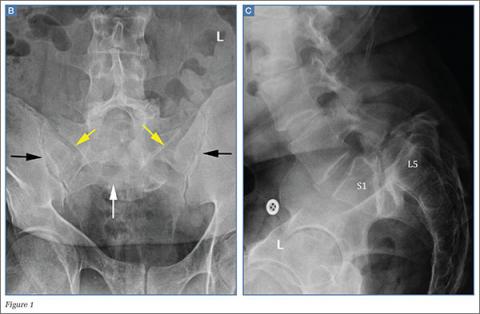

A 49-year-old man presented to the ED with low-back pain. Radiographs of the lumbosacral spine were obtained; a coned-down frontal representative radiograph of the lower lumbar spine and sacrum is presented (Figure 1a).

What is the diagnosis? Is additional imaging necessary? If so, why?

Answer

The frontal radiograph (Figure 1b) shows an “inverted Napoleon hat” sign,1 indicating high-grade anterolisthesis of L5 on S1 (less frequently, this sign also may be indicative of severe lumbar lordosis at the lumbosacral junction).

Anterolisthesis refers to anterior displacement of a vertebral body with respect to the vertebral body immediately below it. The dome of the “inverted hat” is formed by the anteroinferior endplate of the L5 vertebral body (white arrow, Figure 1b), and the tapered edges of the inverted hat are formed by the anteroinferiorly displaced/rotated L5 transverse processes (yellow arrows, Figure 1b). The contours of the L5 transverse processes project medial to the normal sacroiliac joints (black arrows, Figure 1b).

If the inverted Napoleon hat sign is identified on a single frontal view (eg, anteroposterior abdomen or pelvis radiograph), a lateral radiograph of the lumbosacral spine should be obtained to further evaluate the degree of L5-S1 anterolisthesis.

There are five grades of anterolisthesis, each based on quartiles of anterior displacement. Grade 1 anterolisthesis refers to less than 25% anterior displacement; grade 2 refers to 25% to 50% anterior displacement; grade 3 refers to 50% to 75% anterior displacement; and grade 4 refers to greater than 75% anterior displacement. In grade 5 anterolisthesis (also referred to as spondyloptosis), there is 100% anterior displacement with resultant anteroinferior slippage of the displaced vertebral body, which consequently lies anterior to the vertebral body below it. In this patient, the lateral radiograph of the lumbosacral spine (Figure 1c) demonstrates 100% anterior displacement of the L5 vertebral body with respect to S1, compatible with grade 5 anterolisthesis (spondyloptosis).

Spondylolisthesis is the more generalized term that includes all sagittal misalignments of the spine—more specifically, anterolisthesis for anterior displacement or retrolisthesis for posterior displacement. By convention, the displacement is named by the directional displacement of the more superior vertebral body in relation to the vertebral body immediately below it. Spondylolisthesis can be further delineated into one of six etiologic categories according to the modified Newman classification: congenital/dysplastic, spondylolytic, degenerative, traumatic, pathologic, or postsurgical.1,2 Of these six etiologies, spondylolysis (ie, defect of the pars interarticularis) and degenerative change (ie, disc degeneration and facet arthrosis) are the two most common causes of spondylolisthesis. High-grade spondylolisthesis (grade 3 or 4) typically requires bilateral spondylolysis (pars defects), while lower grade spondylolisthesis (particularly grade 1) can occur with any of the above etiologies. As seen in this case, anterolisthesis of L5 on S1 has the greatest effect on the exiting L5 nerve roots, and patients may present with low-back pain and/or hamstring tightness.1

With respect to imaging modalities, noncontrast computed tomography (CT) is of low utility in the workup of high-grade anterolisthesis, since it only serves to demonstrate the bilateral pars defects that are already presumed to be present—even if not seen radiographically. Conversely, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or CT myelography in patients in whom MRI is contraindicated, allows evaluation of the exiting nerve roots at the level of the spondylolisthesis. In addition to the spondylolisthesis, MRI can also reveal nerve impingement at other levels that might not be radiographically apparent (eg, neural foraminal stenosis that occurs due to disc herniation, facet arthrosis, and/or ligamentum flavum hypertrophy).

Management of high-grade spondylolisthesis remains controversial.3,4 Surgical treatment options include instrumented fusion, noninstrumented fusion, and L5 corpectomy with L4-S1 fusion. Fusion is generally recommended for patients with radicular symptoms, chronic incapacitating low-back pain, or risk of progression to spondyloptosis.4

Dr Bartolotta is an assistant professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City, and an assistant attending radiologist at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center; and associate editor, imaging, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Talangbayan LE. The inverted Napoleon’s hat sign. Radiology. 2007;243(2): 603-604.

- Wiltse LL, Newman PH, Macnab I. Classification of spondylolisis and spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;117:23–29.

- Hart RA, Domes CM, Goodwin B, et al. High-grade spondylolisthesis treated using a modified Bohlman technique: results among multiple surgeons. J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;20(5):523-530.

- Lengert R, Charles YP, Walter A, Schuller S, Godet J, Steib JP. Posterior surgery in high-grade spondylolisthesis. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2014;100(5):481-484.

Case

A 49-year-old man presented to the ED with low-back pain. Radiographs of the lumbosacral spine were obtained; a coned-down frontal representative radiograph of the lower lumbar spine and sacrum is presented (Figure 1a).

What is the diagnosis? Is additional imaging necessary? If so, why?

Answer

The frontal radiograph (Figure 1b) shows an “inverted Napoleon hat” sign,1 indicating high-grade anterolisthesis of L5 on S1 (less frequently, this sign also may be indicative of severe lumbar lordosis at the lumbosacral junction).

Anterolisthesis refers to anterior displacement of a vertebral body with respect to the vertebral body immediately below it. The dome of the “inverted hat” is formed by the anteroinferior endplate of the L5 vertebral body (white arrow, Figure 1b), and the tapered edges of the inverted hat are formed by the anteroinferiorly displaced/rotated L5 transverse processes (yellow arrows, Figure 1b). The contours of the L5 transverse processes project medial to the normal sacroiliac joints (black arrows, Figure 1b).

If the inverted Napoleon hat sign is identified on a single frontal view (eg, anteroposterior abdomen or pelvis radiograph), a lateral radiograph of the lumbosacral spine should be obtained to further evaluate the degree of L5-S1 anterolisthesis.

There are five grades of anterolisthesis, each based on quartiles of anterior displacement. Grade 1 anterolisthesis refers to less than 25% anterior displacement; grade 2 refers to 25% to 50% anterior displacement; grade 3 refers to 50% to 75% anterior displacement; and grade 4 refers to greater than 75% anterior displacement. In grade 5 anterolisthesis (also referred to as spondyloptosis), there is 100% anterior displacement with resultant anteroinferior slippage of the displaced vertebral body, which consequently lies anterior to the vertebral body below it. In this patient, the lateral radiograph of the lumbosacral spine (Figure 1c) demonstrates 100% anterior displacement of the L5 vertebral body with respect to S1, compatible with grade 5 anterolisthesis (spondyloptosis).

Spondylolisthesis is the more generalized term that includes all sagittal misalignments of the spine—more specifically, anterolisthesis for anterior displacement or retrolisthesis for posterior displacement. By convention, the displacement is named by the directional displacement of the more superior vertebral body in relation to the vertebral body immediately below it. Spondylolisthesis can be further delineated into one of six etiologic categories according to the modified Newman classification: congenital/dysplastic, spondylolytic, degenerative, traumatic, pathologic, or postsurgical.1,2 Of these six etiologies, spondylolysis (ie, defect of the pars interarticularis) and degenerative change (ie, disc degeneration and facet arthrosis) are the two most common causes of spondylolisthesis. High-grade spondylolisthesis (grade 3 or 4) typically requires bilateral spondylolysis (pars defects), while lower grade spondylolisthesis (particularly grade 1) can occur with any of the above etiologies. As seen in this case, anterolisthesis of L5 on S1 has the greatest effect on the exiting L5 nerve roots, and patients may present with low-back pain and/or hamstring tightness.1

With respect to imaging modalities, noncontrast computed tomography (CT) is of low utility in the workup of high-grade anterolisthesis, since it only serves to demonstrate the bilateral pars defects that are already presumed to be present—even if not seen radiographically. Conversely, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or CT myelography in patients in whom MRI is contraindicated, allows evaluation of the exiting nerve roots at the level of the spondylolisthesis. In addition to the spondylolisthesis, MRI can also reveal nerve impingement at other levels that might not be radiographically apparent (eg, neural foraminal stenosis that occurs due to disc herniation, facet arthrosis, and/or ligamentum flavum hypertrophy).

Management of high-grade spondylolisthesis remains controversial.3,4 Surgical treatment options include instrumented fusion, noninstrumented fusion, and L5 corpectomy with L4-S1 fusion. Fusion is generally recommended for patients with radicular symptoms, chronic incapacitating low-back pain, or risk of progression to spondyloptosis.4

Dr Bartolotta is an assistant professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City, and an assistant attending radiologist at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center; and associate editor, imaging, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

Case

A 49-year-old man presented to the ED with low-back pain. Radiographs of the lumbosacral spine were obtained; a coned-down frontal representative radiograph of the lower lumbar spine and sacrum is presented (Figure 1a).

What is the diagnosis? Is additional imaging necessary? If so, why?

Answer

The frontal radiograph (Figure 1b) shows an “inverted Napoleon hat” sign,1 indicating high-grade anterolisthesis of L5 on S1 (less frequently, this sign also may be indicative of severe lumbar lordosis at the lumbosacral junction).

Anterolisthesis refers to anterior displacement of a vertebral body with respect to the vertebral body immediately below it. The dome of the “inverted hat” is formed by the anteroinferior endplate of the L5 vertebral body (white arrow, Figure 1b), and the tapered edges of the inverted hat are formed by the anteroinferiorly displaced/rotated L5 transverse processes (yellow arrows, Figure 1b). The contours of the L5 transverse processes project medial to the normal sacroiliac joints (black arrows, Figure 1b).

If the inverted Napoleon hat sign is identified on a single frontal view (eg, anteroposterior abdomen or pelvis radiograph), a lateral radiograph of the lumbosacral spine should be obtained to further evaluate the degree of L5-S1 anterolisthesis.

There are five grades of anterolisthesis, each based on quartiles of anterior displacement. Grade 1 anterolisthesis refers to less than 25% anterior displacement; grade 2 refers to 25% to 50% anterior displacement; grade 3 refers to 50% to 75% anterior displacement; and grade 4 refers to greater than 75% anterior displacement. In grade 5 anterolisthesis (also referred to as spondyloptosis), there is 100% anterior displacement with resultant anteroinferior slippage of the displaced vertebral body, which consequently lies anterior to the vertebral body below it. In this patient, the lateral radiograph of the lumbosacral spine (Figure 1c) demonstrates 100% anterior displacement of the L5 vertebral body with respect to S1, compatible with grade 5 anterolisthesis (spondyloptosis).

Spondylolisthesis is the more generalized term that includes all sagittal misalignments of the spine—more specifically, anterolisthesis for anterior displacement or retrolisthesis for posterior displacement. By convention, the displacement is named by the directional displacement of the more superior vertebral body in relation to the vertebral body immediately below it. Spondylolisthesis can be further delineated into one of six etiologic categories according to the modified Newman classification: congenital/dysplastic, spondylolytic, degenerative, traumatic, pathologic, or postsurgical.1,2 Of these six etiologies, spondylolysis (ie, defect of the pars interarticularis) and degenerative change (ie, disc degeneration and facet arthrosis) are the two most common causes of spondylolisthesis. High-grade spondylolisthesis (grade 3 or 4) typically requires bilateral spondylolysis (pars defects), while lower grade spondylolisthesis (particularly grade 1) can occur with any of the above etiologies. As seen in this case, anterolisthesis of L5 on S1 has the greatest effect on the exiting L5 nerve roots, and patients may present with low-back pain and/or hamstring tightness.1

With respect to imaging modalities, noncontrast computed tomography (CT) is of low utility in the workup of high-grade anterolisthesis, since it only serves to demonstrate the bilateral pars defects that are already presumed to be present—even if not seen radiographically. Conversely, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), or CT myelography in patients in whom MRI is contraindicated, allows evaluation of the exiting nerve roots at the level of the spondylolisthesis. In addition to the spondylolisthesis, MRI can also reveal nerve impingement at other levels that might not be radiographically apparent (eg, neural foraminal stenosis that occurs due to disc herniation, facet arthrosis, and/or ligamentum flavum hypertrophy).

Management of high-grade spondylolisthesis remains controversial.3,4 Surgical treatment options include instrumented fusion, noninstrumented fusion, and L5 corpectomy with L4-S1 fusion. Fusion is generally recommended for patients with radicular symptoms, chronic incapacitating low-back pain, or risk of progression to spondyloptosis.4

Dr Bartolotta is an assistant professor of radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College in New York City, and an assistant attending radiologist at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center. Dr Hentel is an associate professor of clinical radiology at Weill Cornell Medical College, New York. He is also chief of emergency/musculoskeletal imaging and executive vice-chairman for the department of radiology at New York-Presbyterian Hospital/Weill Cornell Medical Center; and associate editor, imaging, of the EMERGENCY MEDICINE editorial board.

- Talangbayan LE. The inverted Napoleon’s hat sign. Radiology. 2007;243(2): 603-604.

- Wiltse LL, Newman PH, Macnab I. Classification of spondylolisis and spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;117:23–29.

- Hart RA, Domes CM, Goodwin B, et al. High-grade spondylolisthesis treated using a modified Bohlman technique: results among multiple surgeons. J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;20(5):523-530.

- Lengert R, Charles YP, Walter A, Schuller S, Godet J, Steib JP. Posterior surgery in high-grade spondylolisthesis. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2014;100(5):481-484.

- Talangbayan LE. The inverted Napoleon’s hat sign. Radiology. 2007;243(2): 603-604.

- Wiltse LL, Newman PH, Macnab I. Classification of spondylolisis and spondylolisthesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1976;117:23–29.

- Hart RA, Domes CM, Goodwin B, et al. High-grade spondylolisthesis treated using a modified Bohlman technique: results among multiple surgeons. J Neurosurg Spine. 2014;20(5):523-530.

- Lengert R, Charles YP, Walter A, Schuller S, Godet J, Steib JP. Posterior surgery in high-grade spondylolisthesis. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res. 2014;100(5):481-484.