User login

Nonpharmacologic treatment of chronic pain: What works?

In 2017, the American College of Physicians (ACP) published a clinical practice guideline on the management of low back pain (LBP) that states: “For patients with chronic low back pain, clinicians and patients should initially select nonpharmacologic treatment…”1

This represents a significant shift in clinical practice, as treatment of pain syndromes often starts with analgesics and other medication therapy. This recommendation highlights the need for physicians to place nonpharmacologic therapies front and center in the management of chronic pain syndromes. But recommending nonpharmacologic therapies often represents a daunting task for physicians, as this category encompasses a broad range of treatments, some of which are considered “alternative” and others that are less familiar to physicians.

This article discusses 3 categories of nonpharmacologic therapies in detail: exercise-based therapies, mind-body therapies, and complementary modalities, and answers the question: Which nonpharmacologic treatments should you recommend for specific pain conditions?

In answering the question, we will provide a brief synopsis of several treatments within these 3 broad categories to allow a framework to discuss them with your patients, and we will summarize the evidence for these therapies when used for 3 common pain conditions: chronic LBP, osteoarthritis (OA), and fibromyalgia. Finally, we will offer suggestions on how to utilize these therapies within the context of a patient’s treatment plan.

This review is not without limitations. The quality of evidence is sometimes difficult to evaluate when considering nonpharmacologic therapies and can vary significantly among modalities. We sought to include the highest quality systematic reviews available to best reflect the current state of the evidence. We included Cochrane-based reviews when possible and provided evidence ratings using the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT) system2 in the hope of helping you best counsel your patients on the appropriate use of available options.

Exercise-based therapies: Options to get patients moving

Therapeutic exercise is broadly defined as physical activity that contributes to enhanced aerobic capacity, strength, and/or flexibility, although health benefits are derived from lower-intensity physical activity even when these parameters do not change. Therapeutic exercise has well-documented salubrious effects including decreased all-cause mortality, improved physical fitness, and improvement in a variety of chronic pain conditions. In a 2017 Cochrane review of aerobic exercise for fibromyalgia, pain scores improved by 18%, compared with controls, although the quality of evidence was low (6 trials; n=351).3

Yoga is a system of physical postures and breathing and meditation practices based in Hindu philosophy. Most yoga classes and research protocols involve some combination of these elements.

Continue to: There is a growing body of research demonstrating...

There is a growing body of research demonstrating the benefits and safety of yoga for the treatment of chronic pain. Multiple reviews have evaluated the effectiveness of yoga in the treatment of chronic LBP with fairly consistent results. A 2017 Cochrane review (12 trials; n=1080) found moderate evidence of improvement in functional outcomes, although the magnitude of benefit was small.4 Chou et al found low-quality evidence of improvement in pain and function with yoga compared with usual care, education, and other exercise therapy (14 trials; n=1431).5

Tai chi is a centuries-old system of slow, deliberate, flowing movements based in the Chinese martial arts. The gentle movements make this a particularly appealing treatment for those who may have difficulty with other forms of exercise, such as the elderly and patients with OA. Tai chi is effective for treating a variety of conditions such as back pain, knee pain, and fibromyalgia. Multiple reviews have shown effectiveness in the treatment of OA.6,7

A 2016 randomized controlled trial (RCT) compared a 12-week course of tai chi to standard physical therapy (PT) for knee OA (n=204).8 The authors found that both strategies yielded similar improvement in pain and function, but that the tai chi group had better outcomes in secondary measures of depression and quality of life.8 Chou et al also found tai chi effective for chronic LBP (2 trials; n=480)5 (TABLE 13-5,7,9-13).

Counsel patients seeking to learn tai chi that it takes time to learn all the postures. Beginner classes typically offer the most detailed instruction and are best suited to patients new to the activity.

Mind-body/behavioral therapies: Taking on a greater role

Mind-body therapies are becoming increasingly important in the management of chronic pain syndromes because of an improved understanding of chronic pain pathophysiology. Studies have shown chronic pain can induce changes in the cortex, which can affect pain processing and perpetuate the experience of pain. Mind-body therapies have the potential to directly address brain centers affected by chronic pain.14 In addition, mind-body therapies can improve coexisting psychological symptoms and coping skills.

Continue to: Psychological therapies

Psychological therapies for the treatment of chronic pain are generally based on a cognitive-behavioral theoretical platform. Cognitive processes surrounding the experience (or avoidance) of pain are thought to exacerbate pain symptoms. Patients are encouraged to shift their mental framework away from a pain-oriented focus and toward a personal goal-oriented focus.15

Overall, research has found cognitive behavioral therapies (CBT) to be effective in the management of chronic pain. A 2012 Cochrane review of psychological therapies used in the treatment of nonspecific chronic pain found CBT particularly effective at pain reduction and improvement in disability and pain-related coping skills (35 trials; n=4788).15

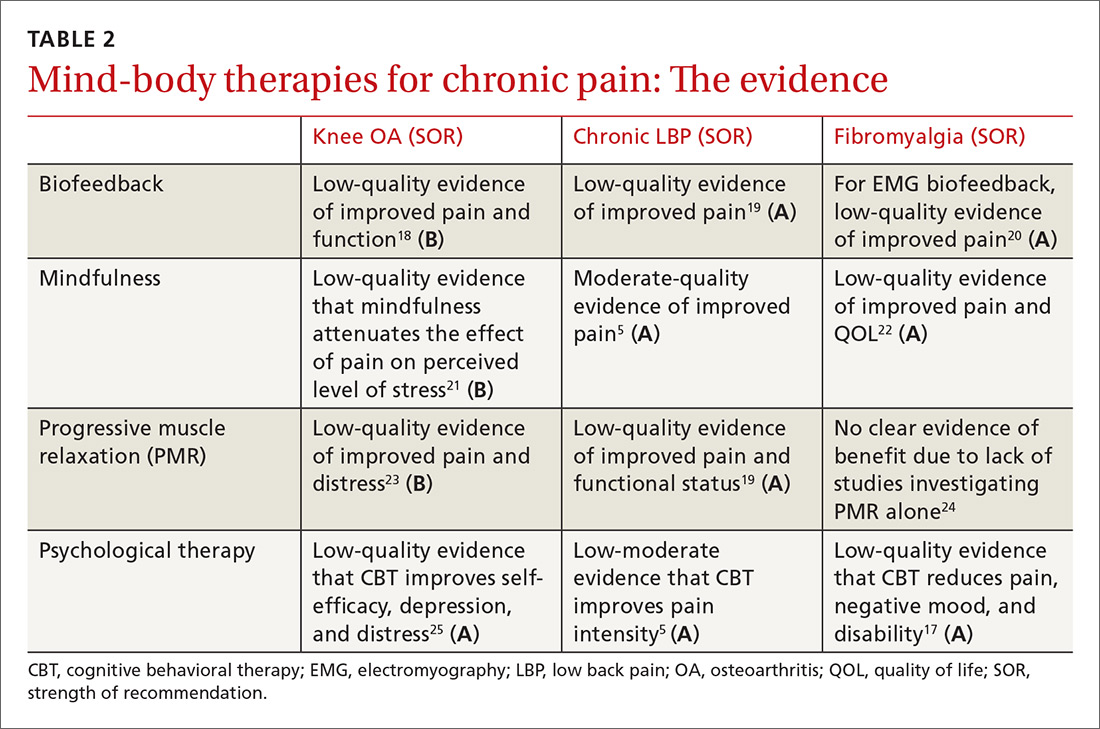

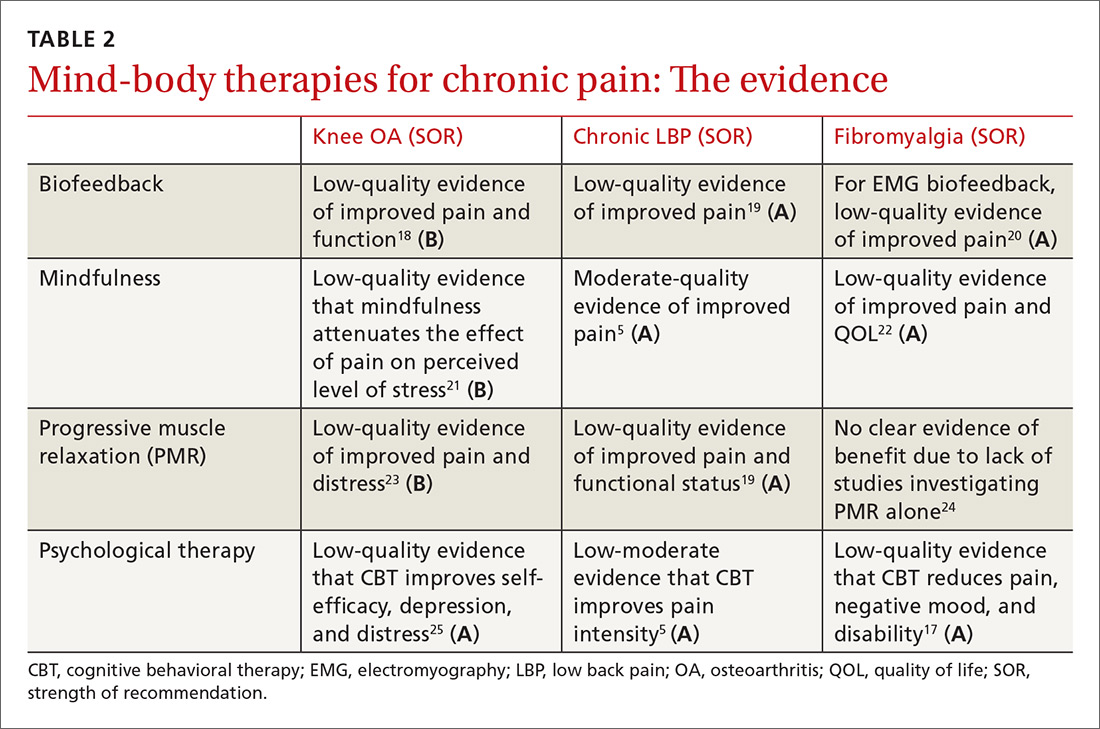

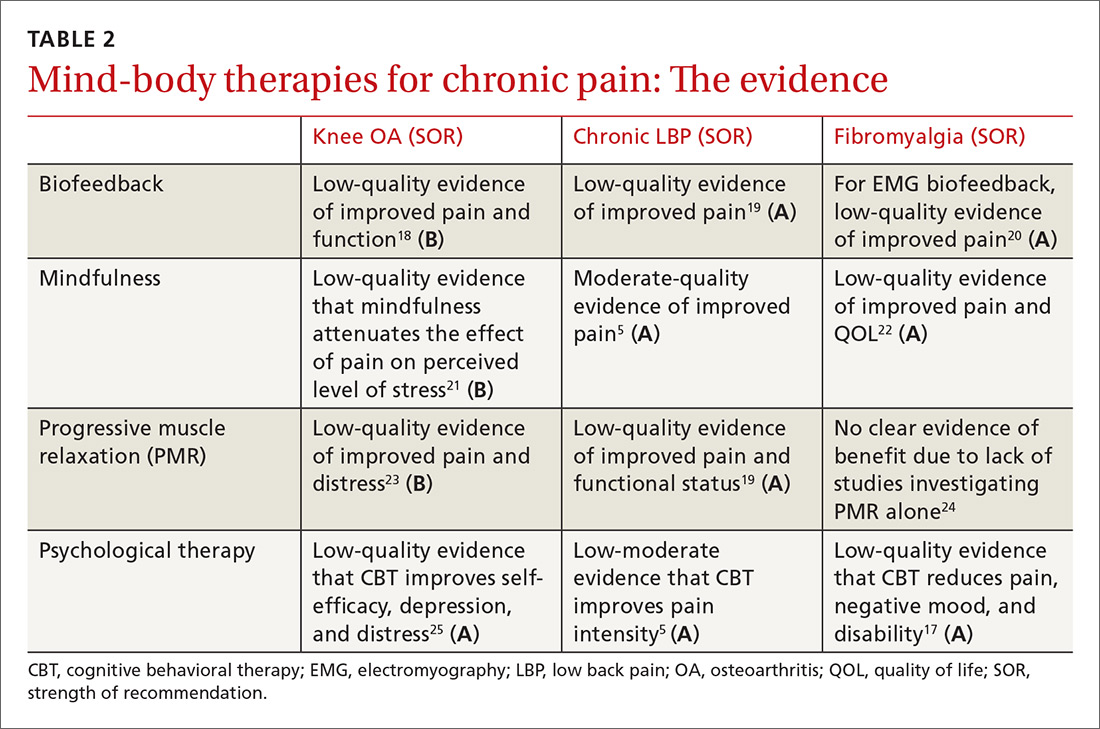

Psychological therapy is generally delivered in a face-to-face encounter, either individually or in a group setting; however, a 2014 Cochrane review suggests that Web-based interventions are efficacious as well.16 Low-quality evidence in a 2013 Cochrane review of CBT for fibromyalgia demonstrated a medium-sized effect of CBT on pain at long-term follow-up (23 trials; n=2031)17 (TABLE 25,17-25).

Biofeedback therapy gives patients real-time information about body processes to help bring those processes under voluntary control. Biofeedback devices measure parameters such as heart rate, blood pressure, and muscle tension and give patients visual or auditory cues to help bring those parameters into desired ranges. There is evidence of benefit in a variety of pain conditions including fibromyalgia, arthritis, LBP, and headache.18,19,26

Many psychologists are trained in biofeedback. A trained therapist usually guides biofeedback interventions initially, but patients can then utilize the skills independently. Devices can be purchased for home use. Phone-based applications are available and can be used, as well.

Continue to: Mindfulness

Mindfulness. Based on Eastern meditative traditions, mindfulness interventions focus on breathing and other body sensations as a means of bringing attention to the felt experience of the present moment. Mindfulness encourages a practice of detached observation with openness and curiosity, which allows for a reframing of experience. The growing body of mindfulness literature points to its effectiveness in a variety of pain conditions. A 2017 meta-analysis of mindfulness for pain conditions found a medium-sized effect on pain based on low-quality evidence (30 trials; n=2292).27

Participants can be taught in a series of group sessions (instruct interested patients to look for classes in their geographic area) or individually through a number of resources such as online audios, books, and smartphone applications.

Progressive muscle relaxation is a relaxation technique consisting of serially tightening and releasing different muscle groups to induce relaxation. Careful attention is paid to the somatic experience of tensing and releasing. Researchers have studied this technique for a variety of pain conditions, with the strongest effects observed in those with arthritis and those with LBP.19,28A variety of health care professionals can administer this therapy in office-based settings, and Internet-based audio recordings are available for home practice.

Complementary modalities for chronic pain

Complementary modalities are frequent additions to pain treatment plans. Spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) and massage therapy are regarded as biomechanical interventions, while acupuncture is categorized as a bio-energetic intervention. As a group, these treatments can address structural issues that may be contributing to pain conditions.

SMT is practiced by chiropractors, osteopathic physicians, and physical therapists. SMT improves function through the use of thrust techniques—quick, high-velocity, low-amplitude force applied to a joint, as well as other manual non-thrust techniques sometimes referred to as “mobilization” techniques. Experts have proposed multiple mechanisms of action for spinal manipulation and mobilization techniques, but ultimately SMT attempts to improve joint range of motion.

Continue to: SMT is most often studied for...

SMT is most often studied for the management of spinal pain. The authors of a 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 RCTs (n=1711) found moderate-quality evidence that SMT improves pain and function in chronic LBP at up to 6 weeks of follow-up.29 A 2017 systematic review performed for an ACP clinical practice guideline on the management of LBP found low-quality evidence of improvement in pain with SMT compared with an inactive treatment, although the magnitude of benefit was small.5 The authors also noted moderate-quality evidence that the benefits of SMT are comparable to other active treatments.5

Massage therapy is commonly used for a variety of pain conditions, but is most studied for LBP. A 2017 systematic review found low-quality evidence of short-term pain relief with massage therapy compared with other active interventions, although the effects were small.5 A 2015 Cochrane review of 25 RCTs (n=3096) found low-quality evidence of benefit for massage in chronic LBP when compared with both active and inactive controls.30

There was a small functional difference when compared with inactive controls. This review highlights the likely short-lived benefit of massage therapy. Although some studies have hinted at longer-term relief with massage therapy, the majority of the literature suggests the benefit is limited to immediate and short-term relief. Massage therapy is safe, although patients with central sensitization should be cautioned that more aggressive massage treatments may cause a flare of myofascial pain.

Acupuncture is one element of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). And while the holistic system of TCM also includes herbal medicine, nutrition, meditative practices, and movement, acupuncture is often practiced as an independent therapy. In the United States, licensed acupuncturists and physicians provide the therapy. Training and licensing laws vary by state, as does insurance coverage.

Pain is the most common reason that people in the United States seek acupuncture therapy. It is not surprising then that the majority of research surrounding acupuncture involves its use for pain conditions. Chou et al reviewed acupuncture for chronic LBP in 2017 (32 trials; n=5931).5 Acupuncture improved both pain and function compared to inactive controls. In addition, 3 trials compared acupuncture to standard medications and found acupuncture to be superior at providing pain relief.

Continue to: In the management of headache pain...

In the management of headache pain, the literature has consistently found acupuncture to be beneficial in the prevention of migraine headaches. A 2016 Cochrane review found acupuncture beneficial compared to no treatment (4 trials; n=2199) or sham acupuncture (10 trials; n=1534), with benefit similar to prophylactic medications but with fewer adverse effects (3 trials; n=744).31

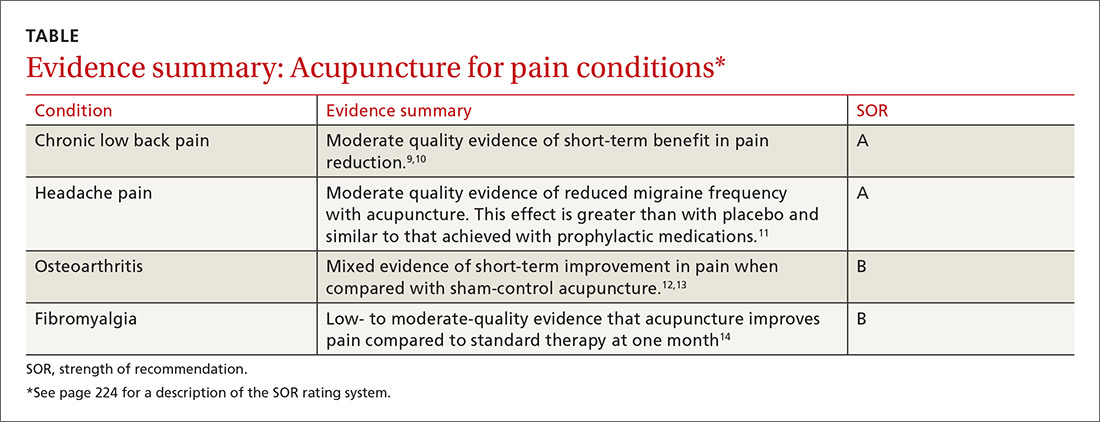

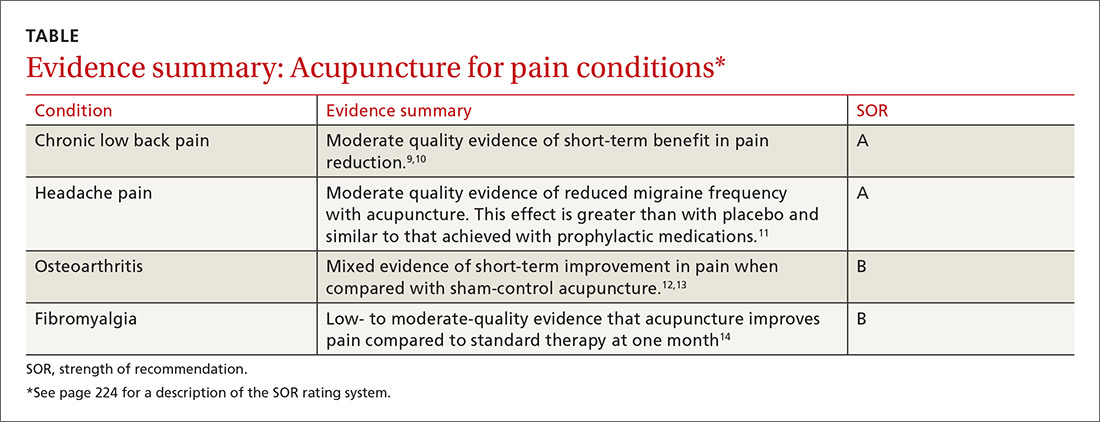

Evidence for benefit in OA pain has been mixed, but a 2016 meta-analysis evaluating 10 trials (n=2007) found acupuncture improved both short-term pain and functional outcome measures when compared with either no treatment or a sham control.32 There have also been reviews showing short-term benefit in fibromyalgia pain (TABLE 35,33-38).33

Building an effective treatment plan

When creating a treatment plan for chronic pain, it’s helpful to keep the following points in mind:

- Emphasize active treatments. Most traditional medical treatments and many complementary therapies are passive, meaning a patient receives a treatment with little agency in its implementation. Active therapies, such as exercise or relaxation practices, engage patients and improve pain-related coping skills. Active treatments promote self-efficacy, which is associated with improved outcomes in chronic pain.39

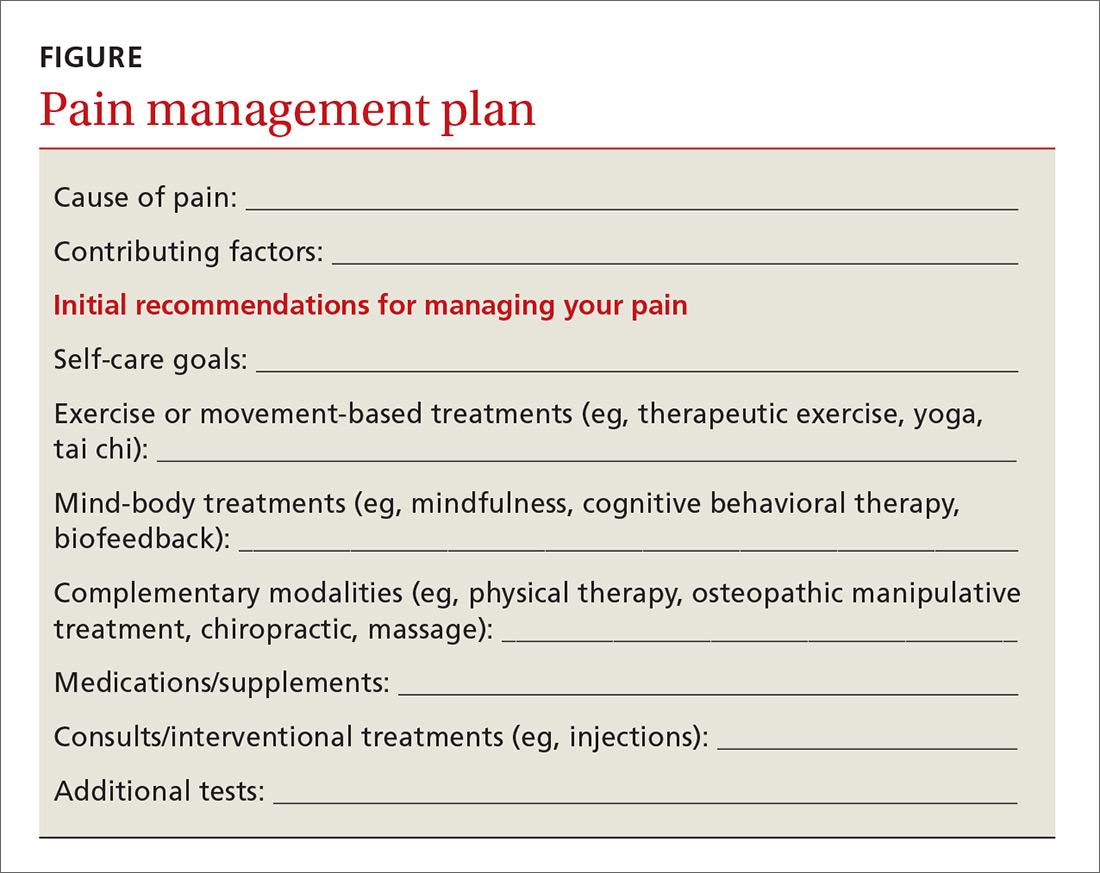

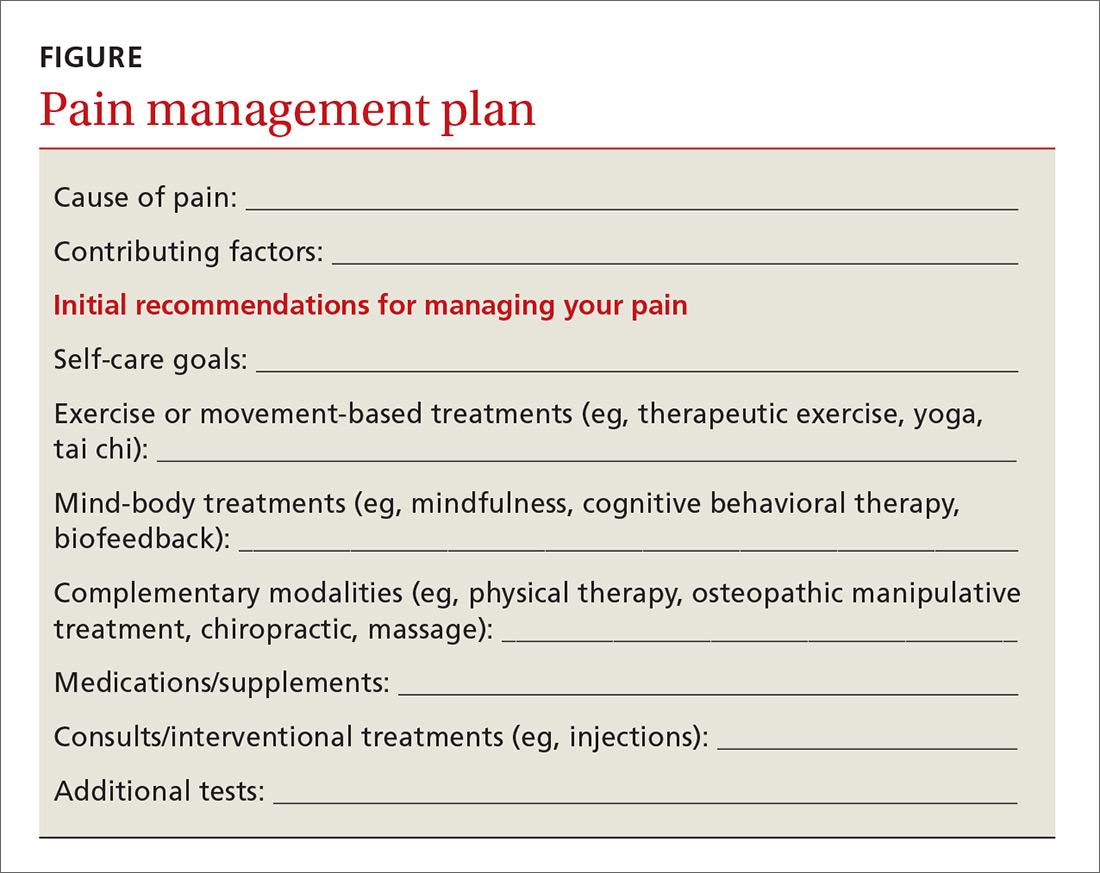

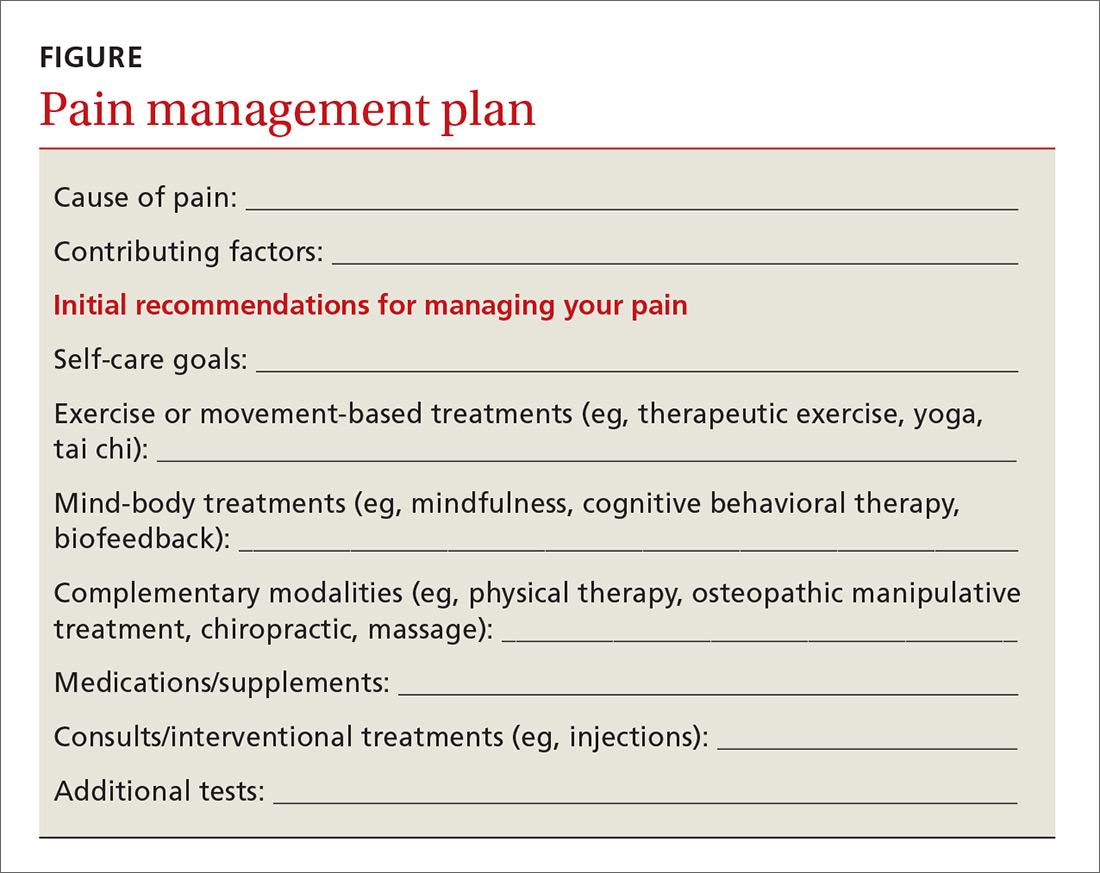

- Use treatments from different categories. Just as it is uncommon to choose multiple medications from the same pharmaceutical class, avoid recommending more than one nonpharmacologic treatment from each category. For example, adding chiropractic therapy to a treatment plan of PT, osteopathic manipulation, and massage isn’t likely to add significant benefit because all of these are structural therapies. Addition of a mind-body therapy would likely be a better choice. Consider the template provided when putting together a pain management plan (FIGURE).

Continue to: Good plan, but how did the office visit go?

Good plan, but how did the office visit go?

A 2006 study by Laerum et al provided unique insights into the best ways to manage chronic pain.40 The authors asked patients a simple question: “What makes a good back consult?” The answers were deceptively simple, but serve as an excellent resource when working with patients to address their pain.

Patients indicated that taking their pain seriously was key to a good back consult. Other factors that were important to patients included: receiving an explanation of what is causing the pain, addressing psychosocial factors, and discussing what could be done.40 The following tips can help you address these patient priorities:

- Explain the underlying cause of the pain. Explaining the complex interplay of factors affecting pain helps patients understand why nonpharmacologic therapies are important. As an example, patients may accept mindfulness meditation as a treatment option if they understand that their chronic LBP is modulated in the brain.

- Address lifestyle and psychosocial issues. Pain syndromes cause far-reaching problems ranging from sleep dysfunction and weight gain to disrupted relationships and loss of employment. Explicitly addressing these issues helps patients cope better with these realities and gives clinicians more therapeutic targets.

The Veterans Affairs Health System offers a self-administered personal health inventory that can facilitate a patient-driven discussion about self-care. (See the Personal Health Inventory form available at: https://www.va.gov/PATIENTCENTEREDCARE/docs/PHI_Short_508.pdf.) In addition to identifying areas for growth, the inventory can highlight what is going well for a patient, adding an element of optimism that is often lacking in office visits for pain problems.

- Discuss what can be done in a way that empowers patients. Moving past medications when discussing pain treatment plans can be challenging. The goal of such discussions is to be as comprehensive as possible by including self-management aspects and nonpharmacologic approaches, in addition to appropriate medications. But this doesn’t all have to be done at once. Help patients set realistic goals for lifestyle-related change, and start with 1 or 2 nonpharmacologic therapies first. This approach both empowers patients and provides them with new treatment options that offer the hope of improved function.

CORRESPONDENCE

Russell Lemmon, DO, 1100 Delaplaine Court, Madison, WI 53715; [email protected].

1. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al, for the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Int Med. 2017;166:514-530.

2. Ebell MH, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): a patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:548-556.

3. Bidonde J, Busch AJ, Schachter CL, et al. Aerobic exercise training for adults with fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(6):CD012700.

4. Wieland LS, Skoetz N, Pilkington K, et al. Yoga treatment for chronic non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev: 2017;(1):CD010671.

5. Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain: a systematic review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:493-505.

6. Hall A, Copsey B, Richmond H, et al. Effectiveness of tai chi for chronic musculoskeletal pain conditions: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther. 2017;97:227-238.

7. Ye J, Cai S, Zhong W, et al. Effects of tai chi for patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. J Phys Ther Sci. 2014;26:1133-1137.

8. Wang C, Schmid CH, Iversen MD, et al. Comparative effectiveness of tai chi versus physical therapy for knee osteoarthritis. Ann Int Med. 2016;165:77-86.

9. Brosseau L, Taki J, Desjardins B, et al. The Ottawa panel clinical practice guidelines for the management of knee osteoarthritis. Part two: strengthening exercise programs. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31:596-611.

10. Busch AJ, Webber SC, Richards RS, et al. Resistance exercise training for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(12):CD010884.

11. Bidonde J, Busch AJ, Webber SC, et al. Aquatic exercise training for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(10):CD011336.

12. Kan L, Zhang J, Yang Y, et al. The effects of yoga on pain, mobility, and quality of life in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:6016532.

13. Langhorst J, Klose P, Dobos GJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of meditative movement therapies in fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:193-207.

14. Flor H. Cortical reorganisation and chronic pain: implications for rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med. 2003;(41 Suppl):66-72.

15. Williams AC, Eccleston C, Morley S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(11):CD007407.

16. Eccleston C, Fisher E, Craig L, et al. Psychological therapies (internet-delivered) for the management of chronic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(2):CD010152.

17. Bernardy K, Klose P, Busch AJ, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapies for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(9):CD009796.

18. Shull PB, Silder A, Shultz R, et al. Six-week gait retraining program reduces knee adduction moment, reduces pain, and improves function for individuals with medial compartment knee osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. 2013;31:1020-1025.

19. Henschke N, Ostelo RW, van Tulder MW, et al. Behavioural treatment for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(7):CD002014.

20. Glombiewski JA, Sawyer AT, Gutermann J, et al. Psychological treatments for fibromyalgia: a meta-analysis. Pain. 2010;151:280-295.

21. Lee AC, Harvey WF, Price LL, et al. Mindfulness is associated with psychological health and moderates pain in knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25:824-831.

22. Lauche R, Cramer H, Dobos G, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of mindfulness-based stress reduction for the fibromyalgia syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75:500-510.

23. Gay MC, Philippot P, Luminet O. Differential effectiveness of psychological interventions for reducing osteoarthritis pain: a comparison of Erickson hypnosis and Jacobson relaxation. Eur J Pain. 2002;6:1-16.

24. Meeus M, Nijs J, Vanderheiden T, et al. The effect of relaxation therapy on autonomic functioning, symptoms and daily functioning, in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome or fibromyalgia: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2015;29:221-233.

25. Briani RV, Ferreira AS, Pazzinatto MF, et al. What interventions can improve quality of life or psychosocial factors of individuals with knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review with meta-analysis of primary outcomes from randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. 2018. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098099.

26. Glombiewski JA, Bernardy K, Häuser W. Efficacy of EMG- and EEG-biofeedback in fibromyalgia syndrome: a meta-analysis and a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:962741.

27. Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, et al. Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51:199-213.

28. Kwekkeboom KL, Gretarsdottir E. Systematic review of relaxation interventions for pain. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2006;38:269-277.

29. Paige NM, Miake-Lye IM, Booth MS, et al. Association of spinal manipulative therapy with clinical benefit and harm for acute low back pain. Systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2017;317:1451-1460.

30. Furlan AD, Giraldo M, Baskwill A, et al. Massage for low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9):CD001929.

31. Linde K, Allais G, Brinkhaus B, et al. Acupuncture for the prevention of episodic migraine. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(6):CD001218.

32. Lin X, Huang K, Zhu G, et al. The effects of acupuncture on chronic knee pain due to osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98:1578-1585.

33. Deare JC, Zheng Z, Xue CC, et al. Acupuncture for treating fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(5):CD007070.

34. Salamh P, Cook C, Reiman MP, et al. Treatment effectiveness and fidelity of manual therapy to the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Musculoskeletal Care. 2017;15:238-248.

35. Posadzki P. Is spinal manipulation effective for pain? An overview of systematic reviews. Pain Med. 2012;13:754-761.

36. Perlman AI, Ali A, Njike VY, et al. Massage therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized dose-finding trial. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30248.

37. Kalichman L. Massage therapy for fibromyalgia symptoms. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1151-1157.

38. Manheimer E, Cheng K, Linde K, et al. Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD001977.

39. Somers TJ, Wren AA, Shelby RA. The context of pain in arthritis: self-efficacy for managing pain and other symptoms. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16:502-508.

40. Laerum E, Indahl A, Skouen JS. What is “the good back-consultation”? A combined qualitative and quantitative study of chronic low back pain patients’ interaction with and perceptions of consultations with specialists. J Rehabil Med. 2006;38:255-262.

In 2017, the American College of Physicians (ACP) published a clinical practice guideline on the management of low back pain (LBP) that states: “For patients with chronic low back pain, clinicians and patients should initially select nonpharmacologic treatment…”1

This represents a significant shift in clinical practice, as treatment of pain syndromes often starts with analgesics and other medication therapy. This recommendation highlights the need for physicians to place nonpharmacologic therapies front and center in the management of chronic pain syndromes. But recommending nonpharmacologic therapies often represents a daunting task for physicians, as this category encompasses a broad range of treatments, some of which are considered “alternative” and others that are less familiar to physicians.

This article discusses 3 categories of nonpharmacologic therapies in detail: exercise-based therapies, mind-body therapies, and complementary modalities, and answers the question: Which nonpharmacologic treatments should you recommend for specific pain conditions?

In answering the question, we will provide a brief synopsis of several treatments within these 3 broad categories to allow a framework to discuss them with your patients, and we will summarize the evidence for these therapies when used for 3 common pain conditions: chronic LBP, osteoarthritis (OA), and fibromyalgia. Finally, we will offer suggestions on how to utilize these therapies within the context of a patient’s treatment plan.

This review is not without limitations. The quality of evidence is sometimes difficult to evaluate when considering nonpharmacologic therapies and can vary significantly among modalities. We sought to include the highest quality systematic reviews available to best reflect the current state of the evidence. We included Cochrane-based reviews when possible and provided evidence ratings using the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT) system2 in the hope of helping you best counsel your patients on the appropriate use of available options.

Exercise-based therapies: Options to get patients moving

Therapeutic exercise is broadly defined as physical activity that contributes to enhanced aerobic capacity, strength, and/or flexibility, although health benefits are derived from lower-intensity physical activity even when these parameters do not change. Therapeutic exercise has well-documented salubrious effects including decreased all-cause mortality, improved physical fitness, and improvement in a variety of chronic pain conditions. In a 2017 Cochrane review of aerobic exercise for fibromyalgia, pain scores improved by 18%, compared with controls, although the quality of evidence was low (6 trials; n=351).3

Yoga is a system of physical postures and breathing and meditation practices based in Hindu philosophy. Most yoga classes and research protocols involve some combination of these elements.

Continue to: There is a growing body of research demonstrating...

There is a growing body of research demonstrating the benefits and safety of yoga for the treatment of chronic pain. Multiple reviews have evaluated the effectiveness of yoga in the treatment of chronic LBP with fairly consistent results. A 2017 Cochrane review (12 trials; n=1080) found moderate evidence of improvement in functional outcomes, although the magnitude of benefit was small.4 Chou et al found low-quality evidence of improvement in pain and function with yoga compared with usual care, education, and other exercise therapy (14 trials; n=1431).5

Tai chi is a centuries-old system of slow, deliberate, flowing movements based in the Chinese martial arts. The gentle movements make this a particularly appealing treatment for those who may have difficulty with other forms of exercise, such as the elderly and patients with OA. Tai chi is effective for treating a variety of conditions such as back pain, knee pain, and fibromyalgia. Multiple reviews have shown effectiveness in the treatment of OA.6,7

A 2016 randomized controlled trial (RCT) compared a 12-week course of tai chi to standard physical therapy (PT) for knee OA (n=204).8 The authors found that both strategies yielded similar improvement in pain and function, but that the tai chi group had better outcomes in secondary measures of depression and quality of life.8 Chou et al also found tai chi effective for chronic LBP (2 trials; n=480)5 (TABLE 13-5,7,9-13).

Counsel patients seeking to learn tai chi that it takes time to learn all the postures. Beginner classes typically offer the most detailed instruction and are best suited to patients new to the activity.

Mind-body/behavioral therapies: Taking on a greater role

Mind-body therapies are becoming increasingly important in the management of chronic pain syndromes because of an improved understanding of chronic pain pathophysiology. Studies have shown chronic pain can induce changes in the cortex, which can affect pain processing and perpetuate the experience of pain. Mind-body therapies have the potential to directly address brain centers affected by chronic pain.14 In addition, mind-body therapies can improve coexisting psychological symptoms and coping skills.

Continue to: Psychological therapies

Psychological therapies for the treatment of chronic pain are generally based on a cognitive-behavioral theoretical platform. Cognitive processes surrounding the experience (or avoidance) of pain are thought to exacerbate pain symptoms. Patients are encouraged to shift their mental framework away from a pain-oriented focus and toward a personal goal-oriented focus.15

Overall, research has found cognitive behavioral therapies (CBT) to be effective in the management of chronic pain. A 2012 Cochrane review of psychological therapies used in the treatment of nonspecific chronic pain found CBT particularly effective at pain reduction and improvement in disability and pain-related coping skills (35 trials; n=4788).15

Psychological therapy is generally delivered in a face-to-face encounter, either individually or in a group setting; however, a 2014 Cochrane review suggests that Web-based interventions are efficacious as well.16 Low-quality evidence in a 2013 Cochrane review of CBT for fibromyalgia demonstrated a medium-sized effect of CBT on pain at long-term follow-up (23 trials; n=2031)17 (TABLE 25,17-25).

Biofeedback therapy gives patients real-time information about body processes to help bring those processes under voluntary control. Biofeedback devices measure parameters such as heart rate, blood pressure, and muscle tension and give patients visual or auditory cues to help bring those parameters into desired ranges. There is evidence of benefit in a variety of pain conditions including fibromyalgia, arthritis, LBP, and headache.18,19,26

Many psychologists are trained in biofeedback. A trained therapist usually guides biofeedback interventions initially, but patients can then utilize the skills independently. Devices can be purchased for home use. Phone-based applications are available and can be used, as well.

Continue to: Mindfulness

Mindfulness. Based on Eastern meditative traditions, mindfulness interventions focus on breathing and other body sensations as a means of bringing attention to the felt experience of the present moment. Mindfulness encourages a practice of detached observation with openness and curiosity, which allows for a reframing of experience. The growing body of mindfulness literature points to its effectiveness in a variety of pain conditions. A 2017 meta-analysis of mindfulness for pain conditions found a medium-sized effect on pain based on low-quality evidence (30 trials; n=2292).27

Participants can be taught in a series of group sessions (instruct interested patients to look for classes in their geographic area) or individually through a number of resources such as online audios, books, and smartphone applications.

Progressive muscle relaxation is a relaxation technique consisting of serially tightening and releasing different muscle groups to induce relaxation. Careful attention is paid to the somatic experience of tensing and releasing. Researchers have studied this technique for a variety of pain conditions, with the strongest effects observed in those with arthritis and those with LBP.19,28A variety of health care professionals can administer this therapy in office-based settings, and Internet-based audio recordings are available for home practice.

Complementary modalities for chronic pain

Complementary modalities are frequent additions to pain treatment plans. Spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) and massage therapy are regarded as biomechanical interventions, while acupuncture is categorized as a bio-energetic intervention. As a group, these treatments can address structural issues that may be contributing to pain conditions.

SMT is practiced by chiropractors, osteopathic physicians, and physical therapists. SMT improves function through the use of thrust techniques—quick, high-velocity, low-amplitude force applied to a joint, as well as other manual non-thrust techniques sometimes referred to as “mobilization” techniques. Experts have proposed multiple mechanisms of action for spinal manipulation and mobilization techniques, but ultimately SMT attempts to improve joint range of motion.

Continue to: SMT is most often studied for...

SMT is most often studied for the management of spinal pain. The authors of a 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 RCTs (n=1711) found moderate-quality evidence that SMT improves pain and function in chronic LBP at up to 6 weeks of follow-up.29 A 2017 systematic review performed for an ACP clinical practice guideline on the management of LBP found low-quality evidence of improvement in pain with SMT compared with an inactive treatment, although the magnitude of benefit was small.5 The authors also noted moderate-quality evidence that the benefits of SMT are comparable to other active treatments.5

Massage therapy is commonly used for a variety of pain conditions, but is most studied for LBP. A 2017 systematic review found low-quality evidence of short-term pain relief with massage therapy compared with other active interventions, although the effects were small.5 A 2015 Cochrane review of 25 RCTs (n=3096) found low-quality evidence of benefit for massage in chronic LBP when compared with both active and inactive controls.30

There was a small functional difference when compared with inactive controls. This review highlights the likely short-lived benefit of massage therapy. Although some studies have hinted at longer-term relief with massage therapy, the majority of the literature suggests the benefit is limited to immediate and short-term relief. Massage therapy is safe, although patients with central sensitization should be cautioned that more aggressive massage treatments may cause a flare of myofascial pain.

Acupuncture is one element of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). And while the holistic system of TCM also includes herbal medicine, nutrition, meditative practices, and movement, acupuncture is often practiced as an independent therapy. In the United States, licensed acupuncturists and physicians provide the therapy. Training and licensing laws vary by state, as does insurance coverage.

Pain is the most common reason that people in the United States seek acupuncture therapy. It is not surprising then that the majority of research surrounding acupuncture involves its use for pain conditions. Chou et al reviewed acupuncture for chronic LBP in 2017 (32 trials; n=5931).5 Acupuncture improved both pain and function compared to inactive controls. In addition, 3 trials compared acupuncture to standard medications and found acupuncture to be superior at providing pain relief.

Continue to: In the management of headache pain...

In the management of headache pain, the literature has consistently found acupuncture to be beneficial in the prevention of migraine headaches. A 2016 Cochrane review found acupuncture beneficial compared to no treatment (4 trials; n=2199) or sham acupuncture (10 trials; n=1534), with benefit similar to prophylactic medications but with fewer adverse effects (3 trials; n=744).31

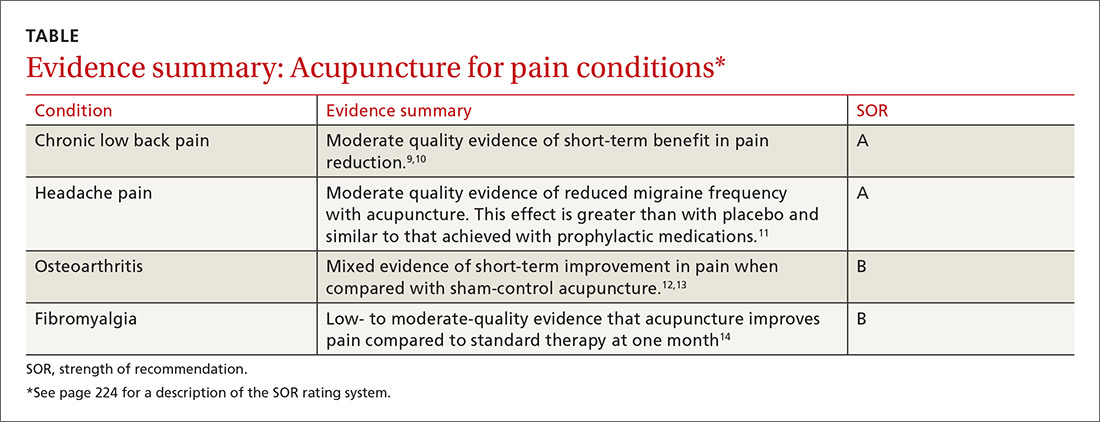

Evidence for benefit in OA pain has been mixed, but a 2016 meta-analysis evaluating 10 trials (n=2007) found acupuncture improved both short-term pain and functional outcome measures when compared with either no treatment or a sham control.32 There have also been reviews showing short-term benefit in fibromyalgia pain (TABLE 35,33-38).33

Building an effective treatment plan

When creating a treatment plan for chronic pain, it’s helpful to keep the following points in mind:

- Emphasize active treatments. Most traditional medical treatments and many complementary therapies are passive, meaning a patient receives a treatment with little agency in its implementation. Active therapies, such as exercise or relaxation practices, engage patients and improve pain-related coping skills. Active treatments promote self-efficacy, which is associated with improved outcomes in chronic pain.39

- Use treatments from different categories. Just as it is uncommon to choose multiple medications from the same pharmaceutical class, avoid recommending more than one nonpharmacologic treatment from each category. For example, adding chiropractic therapy to a treatment plan of PT, osteopathic manipulation, and massage isn’t likely to add significant benefit because all of these are structural therapies. Addition of a mind-body therapy would likely be a better choice. Consider the template provided when putting together a pain management plan (FIGURE).

Continue to: Good plan, but how did the office visit go?

Good plan, but how did the office visit go?

A 2006 study by Laerum et al provided unique insights into the best ways to manage chronic pain.40 The authors asked patients a simple question: “What makes a good back consult?” The answers were deceptively simple, but serve as an excellent resource when working with patients to address their pain.

Patients indicated that taking their pain seriously was key to a good back consult. Other factors that were important to patients included: receiving an explanation of what is causing the pain, addressing psychosocial factors, and discussing what could be done.40 The following tips can help you address these patient priorities:

- Explain the underlying cause of the pain. Explaining the complex interplay of factors affecting pain helps patients understand why nonpharmacologic therapies are important. As an example, patients may accept mindfulness meditation as a treatment option if they understand that their chronic LBP is modulated in the brain.

- Address lifestyle and psychosocial issues. Pain syndromes cause far-reaching problems ranging from sleep dysfunction and weight gain to disrupted relationships and loss of employment. Explicitly addressing these issues helps patients cope better with these realities and gives clinicians more therapeutic targets.

The Veterans Affairs Health System offers a self-administered personal health inventory that can facilitate a patient-driven discussion about self-care. (See the Personal Health Inventory form available at: https://www.va.gov/PATIENTCENTEREDCARE/docs/PHI_Short_508.pdf.) In addition to identifying areas for growth, the inventory can highlight what is going well for a patient, adding an element of optimism that is often lacking in office visits for pain problems.

- Discuss what can be done in a way that empowers patients. Moving past medications when discussing pain treatment plans can be challenging. The goal of such discussions is to be as comprehensive as possible by including self-management aspects and nonpharmacologic approaches, in addition to appropriate medications. But this doesn’t all have to be done at once. Help patients set realistic goals for lifestyle-related change, and start with 1 or 2 nonpharmacologic therapies first. This approach both empowers patients and provides them with new treatment options that offer the hope of improved function.

CORRESPONDENCE

Russell Lemmon, DO, 1100 Delaplaine Court, Madison, WI 53715; [email protected].

In 2017, the American College of Physicians (ACP) published a clinical practice guideline on the management of low back pain (LBP) that states: “For patients with chronic low back pain, clinicians and patients should initially select nonpharmacologic treatment…”1

This represents a significant shift in clinical practice, as treatment of pain syndromes often starts with analgesics and other medication therapy. This recommendation highlights the need for physicians to place nonpharmacologic therapies front and center in the management of chronic pain syndromes. But recommending nonpharmacologic therapies often represents a daunting task for physicians, as this category encompasses a broad range of treatments, some of which are considered “alternative” and others that are less familiar to physicians.

This article discusses 3 categories of nonpharmacologic therapies in detail: exercise-based therapies, mind-body therapies, and complementary modalities, and answers the question: Which nonpharmacologic treatments should you recommend for specific pain conditions?

In answering the question, we will provide a brief synopsis of several treatments within these 3 broad categories to allow a framework to discuss them with your patients, and we will summarize the evidence for these therapies when used for 3 common pain conditions: chronic LBP, osteoarthritis (OA), and fibromyalgia. Finally, we will offer suggestions on how to utilize these therapies within the context of a patient’s treatment plan.

This review is not without limitations. The quality of evidence is sometimes difficult to evaluate when considering nonpharmacologic therapies and can vary significantly among modalities. We sought to include the highest quality systematic reviews available to best reflect the current state of the evidence. We included Cochrane-based reviews when possible and provided evidence ratings using the Strength of Recommendation Taxonomy (SORT) system2 in the hope of helping you best counsel your patients on the appropriate use of available options.

Exercise-based therapies: Options to get patients moving

Therapeutic exercise is broadly defined as physical activity that contributes to enhanced aerobic capacity, strength, and/or flexibility, although health benefits are derived from lower-intensity physical activity even when these parameters do not change. Therapeutic exercise has well-documented salubrious effects including decreased all-cause mortality, improved physical fitness, and improvement in a variety of chronic pain conditions. In a 2017 Cochrane review of aerobic exercise for fibromyalgia, pain scores improved by 18%, compared with controls, although the quality of evidence was low (6 trials; n=351).3

Yoga is a system of physical postures and breathing and meditation practices based in Hindu philosophy. Most yoga classes and research protocols involve some combination of these elements.

Continue to: There is a growing body of research demonstrating...

There is a growing body of research demonstrating the benefits and safety of yoga for the treatment of chronic pain. Multiple reviews have evaluated the effectiveness of yoga in the treatment of chronic LBP with fairly consistent results. A 2017 Cochrane review (12 trials; n=1080) found moderate evidence of improvement in functional outcomes, although the magnitude of benefit was small.4 Chou et al found low-quality evidence of improvement in pain and function with yoga compared with usual care, education, and other exercise therapy (14 trials; n=1431).5

Tai chi is a centuries-old system of slow, deliberate, flowing movements based in the Chinese martial arts. The gentle movements make this a particularly appealing treatment for those who may have difficulty with other forms of exercise, such as the elderly and patients with OA. Tai chi is effective for treating a variety of conditions such as back pain, knee pain, and fibromyalgia. Multiple reviews have shown effectiveness in the treatment of OA.6,7

A 2016 randomized controlled trial (RCT) compared a 12-week course of tai chi to standard physical therapy (PT) for knee OA (n=204).8 The authors found that both strategies yielded similar improvement in pain and function, but that the tai chi group had better outcomes in secondary measures of depression and quality of life.8 Chou et al also found tai chi effective for chronic LBP (2 trials; n=480)5 (TABLE 13-5,7,9-13).

Counsel patients seeking to learn tai chi that it takes time to learn all the postures. Beginner classes typically offer the most detailed instruction and are best suited to patients new to the activity.

Mind-body/behavioral therapies: Taking on a greater role

Mind-body therapies are becoming increasingly important in the management of chronic pain syndromes because of an improved understanding of chronic pain pathophysiology. Studies have shown chronic pain can induce changes in the cortex, which can affect pain processing and perpetuate the experience of pain. Mind-body therapies have the potential to directly address brain centers affected by chronic pain.14 In addition, mind-body therapies can improve coexisting psychological symptoms and coping skills.

Continue to: Psychological therapies

Psychological therapies for the treatment of chronic pain are generally based on a cognitive-behavioral theoretical platform. Cognitive processes surrounding the experience (or avoidance) of pain are thought to exacerbate pain symptoms. Patients are encouraged to shift their mental framework away from a pain-oriented focus and toward a personal goal-oriented focus.15

Overall, research has found cognitive behavioral therapies (CBT) to be effective in the management of chronic pain. A 2012 Cochrane review of psychological therapies used in the treatment of nonspecific chronic pain found CBT particularly effective at pain reduction and improvement in disability and pain-related coping skills (35 trials; n=4788).15

Psychological therapy is generally delivered in a face-to-face encounter, either individually or in a group setting; however, a 2014 Cochrane review suggests that Web-based interventions are efficacious as well.16 Low-quality evidence in a 2013 Cochrane review of CBT for fibromyalgia demonstrated a medium-sized effect of CBT on pain at long-term follow-up (23 trials; n=2031)17 (TABLE 25,17-25).

Biofeedback therapy gives patients real-time information about body processes to help bring those processes under voluntary control. Biofeedback devices measure parameters such as heart rate, blood pressure, and muscle tension and give patients visual or auditory cues to help bring those parameters into desired ranges. There is evidence of benefit in a variety of pain conditions including fibromyalgia, arthritis, LBP, and headache.18,19,26

Many psychologists are trained in biofeedback. A trained therapist usually guides biofeedback interventions initially, but patients can then utilize the skills independently. Devices can be purchased for home use. Phone-based applications are available and can be used, as well.

Continue to: Mindfulness

Mindfulness. Based on Eastern meditative traditions, mindfulness interventions focus on breathing and other body sensations as a means of bringing attention to the felt experience of the present moment. Mindfulness encourages a practice of detached observation with openness and curiosity, which allows for a reframing of experience. The growing body of mindfulness literature points to its effectiveness in a variety of pain conditions. A 2017 meta-analysis of mindfulness for pain conditions found a medium-sized effect on pain based on low-quality evidence (30 trials; n=2292).27

Participants can be taught in a series of group sessions (instruct interested patients to look for classes in their geographic area) or individually through a number of resources such as online audios, books, and smartphone applications.

Progressive muscle relaxation is a relaxation technique consisting of serially tightening and releasing different muscle groups to induce relaxation. Careful attention is paid to the somatic experience of tensing and releasing. Researchers have studied this technique for a variety of pain conditions, with the strongest effects observed in those with arthritis and those with LBP.19,28A variety of health care professionals can administer this therapy in office-based settings, and Internet-based audio recordings are available for home practice.

Complementary modalities for chronic pain

Complementary modalities are frequent additions to pain treatment plans. Spinal manipulative therapy (SMT) and massage therapy are regarded as biomechanical interventions, while acupuncture is categorized as a bio-energetic intervention. As a group, these treatments can address structural issues that may be contributing to pain conditions.

SMT is practiced by chiropractors, osteopathic physicians, and physical therapists. SMT improves function through the use of thrust techniques—quick, high-velocity, low-amplitude force applied to a joint, as well as other manual non-thrust techniques sometimes referred to as “mobilization” techniques. Experts have proposed multiple mechanisms of action for spinal manipulation and mobilization techniques, but ultimately SMT attempts to improve joint range of motion.

Continue to: SMT is most often studied for...

SMT is most often studied for the management of spinal pain. The authors of a 2017 systematic review and meta-analysis of 15 RCTs (n=1711) found moderate-quality evidence that SMT improves pain and function in chronic LBP at up to 6 weeks of follow-up.29 A 2017 systematic review performed for an ACP clinical practice guideline on the management of LBP found low-quality evidence of improvement in pain with SMT compared with an inactive treatment, although the magnitude of benefit was small.5 The authors also noted moderate-quality evidence that the benefits of SMT are comparable to other active treatments.5

Massage therapy is commonly used for a variety of pain conditions, but is most studied for LBP. A 2017 systematic review found low-quality evidence of short-term pain relief with massage therapy compared with other active interventions, although the effects were small.5 A 2015 Cochrane review of 25 RCTs (n=3096) found low-quality evidence of benefit for massage in chronic LBP when compared with both active and inactive controls.30

There was a small functional difference when compared with inactive controls. This review highlights the likely short-lived benefit of massage therapy. Although some studies have hinted at longer-term relief with massage therapy, the majority of the literature suggests the benefit is limited to immediate and short-term relief. Massage therapy is safe, although patients with central sensitization should be cautioned that more aggressive massage treatments may cause a flare of myofascial pain.

Acupuncture is one element of traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). And while the holistic system of TCM also includes herbal medicine, nutrition, meditative practices, and movement, acupuncture is often practiced as an independent therapy. In the United States, licensed acupuncturists and physicians provide the therapy. Training and licensing laws vary by state, as does insurance coverage.

Pain is the most common reason that people in the United States seek acupuncture therapy. It is not surprising then that the majority of research surrounding acupuncture involves its use for pain conditions. Chou et al reviewed acupuncture for chronic LBP in 2017 (32 trials; n=5931).5 Acupuncture improved both pain and function compared to inactive controls. In addition, 3 trials compared acupuncture to standard medications and found acupuncture to be superior at providing pain relief.

Continue to: In the management of headache pain...

In the management of headache pain, the literature has consistently found acupuncture to be beneficial in the prevention of migraine headaches. A 2016 Cochrane review found acupuncture beneficial compared to no treatment (4 trials; n=2199) or sham acupuncture (10 trials; n=1534), with benefit similar to prophylactic medications but with fewer adverse effects (3 trials; n=744).31

Evidence for benefit in OA pain has been mixed, but a 2016 meta-analysis evaluating 10 trials (n=2007) found acupuncture improved both short-term pain and functional outcome measures when compared with either no treatment or a sham control.32 There have also been reviews showing short-term benefit in fibromyalgia pain (TABLE 35,33-38).33

Building an effective treatment plan

When creating a treatment plan for chronic pain, it’s helpful to keep the following points in mind:

- Emphasize active treatments. Most traditional medical treatments and many complementary therapies are passive, meaning a patient receives a treatment with little agency in its implementation. Active therapies, such as exercise or relaxation practices, engage patients and improve pain-related coping skills. Active treatments promote self-efficacy, which is associated with improved outcomes in chronic pain.39

- Use treatments from different categories. Just as it is uncommon to choose multiple medications from the same pharmaceutical class, avoid recommending more than one nonpharmacologic treatment from each category. For example, adding chiropractic therapy to a treatment plan of PT, osteopathic manipulation, and massage isn’t likely to add significant benefit because all of these are structural therapies. Addition of a mind-body therapy would likely be a better choice. Consider the template provided when putting together a pain management plan (FIGURE).

Continue to: Good plan, but how did the office visit go?

Good plan, but how did the office visit go?

A 2006 study by Laerum et al provided unique insights into the best ways to manage chronic pain.40 The authors asked patients a simple question: “What makes a good back consult?” The answers were deceptively simple, but serve as an excellent resource when working with patients to address their pain.

Patients indicated that taking their pain seriously was key to a good back consult. Other factors that were important to patients included: receiving an explanation of what is causing the pain, addressing psychosocial factors, and discussing what could be done.40 The following tips can help you address these patient priorities:

- Explain the underlying cause of the pain. Explaining the complex interplay of factors affecting pain helps patients understand why nonpharmacologic therapies are important. As an example, patients may accept mindfulness meditation as a treatment option if they understand that their chronic LBP is modulated in the brain.

- Address lifestyle and psychosocial issues. Pain syndromes cause far-reaching problems ranging from sleep dysfunction and weight gain to disrupted relationships and loss of employment. Explicitly addressing these issues helps patients cope better with these realities and gives clinicians more therapeutic targets.

The Veterans Affairs Health System offers a self-administered personal health inventory that can facilitate a patient-driven discussion about self-care. (See the Personal Health Inventory form available at: https://www.va.gov/PATIENTCENTEREDCARE/docs/PHI_Short_508.pdf.) In addition to identifying areas for growth, the inventory can highlight what is going well for a patient, adding an element of optimism that is often lacking in office visits for pain problems.

- Discuss what can be done in a way that empowers patients. Moving past medications when discussing pain treatment plans can be challenging. The goal of such discussions is to be as comprehensive as possible by including self-management aspects and nonpharmacologic approaches, in addition to appropriate medications. But this doesn’t all have to be done at once. Help patients set realistic goals for lifestyle-related change, and start with 1 or 2 nonpharmacologic therapies first. This approach both empowers patients and provides them with new treatment options that offer the hope of improved function.

CORRESPONDENCE

Russell Lemmon, DO, 1100 Delaplaine Court, Madison, WI 53715; [email protected].

1. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al, for the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Int Med. 2017;166:514-530.

2. Ebell MH, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): a patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:548-556.

3. Bidonde J, Busch AJ, Schachter CL, et al. Aerobic exercise training for adults with fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(6):CD012700.

4. Wieland LS, Skoetz N, Pilkington K, et al. Yoga treatment for chronic non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev: 2017;(1):CD010671.

5. Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain: a systematic review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:493-505.

6. Hall A, Copsey B, Richmond H, et al. Effectiveness of tai chi for chronic musculoskeletal pain conditions: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther. 2017;97:227-238.

7. Ye J, Cai S, Zhong W, et al. Effects of tai chi for patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. J Phys Ther Sci. 2014;26:1133-1137.

8. Wang C, Schmid CH, Iversen MD, et al. Comparative effectiveness of tai chi versus physical therapy for knee osteoarthritis. Ann Int Med. 2016;165:77-86.

9. Brosseau L, Taki J, Desjardins B, et al. The Ottawa panel clinical practice guidelines for the management of knee osteoarthritis. Part two: strengthening exercise programs. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31:596-611.

10. Busch AJ, Webber SC, Richards RS, et al. Resistance exercise training for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(12):CD010884.

11. Bidonde J, Busch AJ, Webber SC, et al. Aquatic exercise training for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(10):CD011336.

12. Kan L, Zhang J, Yang Y, et al. The effects of yoga on pain, mobility, and quality of life in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:6016532.

13. Langhorst J, Klose P, Dobos GJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of meditative movement therapies in fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:193-207.

14. Flor H. Cortical reorganisation and chronic pain: implications for rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med. 2003;(41 Suppl):66-72.

15. Williams AC, Eccleston C, Morley S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(11):CD007407.

16. Eccleston C, Fisher E, Craig L, et al. Psychological therapies (internet-delivered) for the management of chronic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(2):CD010152.

17. Bernardy K, Klose P, Busch AJ, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapies for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(9):CD009796.

18. Shull PB, Silder A, Shultz R, et al. Six-week gait retraining program reduces knee adduction moment, reduces pain, and improves function for individuals with medial compartment knee osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. 2013;31:1020-1025.

19. Henschke N, Ostelo RW, van Tulder MW, et al. Behavioural treatment for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(7):CD002014.

20. Glombiewski JA, Sawyer AT, Gutermann J, et al. Psychological treatments for fibromyalgia: a meta-analysis. Pain. 2010;151:280-295.

21. Lee AC, Harvey WF, Price LL, et al. Mindfulness is associated with psychological health and moderates pain in knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25:824-831.

22. Lauche R, Cramer H, Dobos G, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of mindfulness-based stress reduction for the fibromyalgia syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75:500-510.

23. Gay MC, Philippot P, Luminet O. Differential effectiveness of psychological interventions for reducing osteoarthritis pain: a comparison of Erickson hypnosis and Jacobson relaxation. Eur J Pain. 2002;6:1-16.

24. Meeus M, Nijs J, Vanderheiden T, et al. The effect of relaxation therapy on autonomic functioning, symptoms and daily functioning, in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome or fibromyalgia: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2015;29:221-233.

25. Briani RV, Ferreira AS, Pazzinatto MF, et al. What interventions can improve quality of life or psychosocial factors of individuals with knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review with meta-analysis of primary outcomes from randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. 2018. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098099.

26. Glombiewski JA, Bernardy K, Häuser W. Efficacy of EMG- and EEG-biofeedback in fibromyalgia syndrome: a meta-analysis and a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:962741.

27. Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, et al. Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51:199-213.

28. Kwekkeboom KL, Gretarsdottir E. Systematic review of relaxation interventions for pain. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2006;38:269-277.

29. Paige NM, Miake-Lye IM, Booth MS, et al. Association of spinal manipulative therapy with clinical benefit and harm for acute low back pain. Systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2017;317:1451-1460.

30. Furlan AD, Giraldo M, Baskwill A, et al. Massage for low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9):CD001929.

31. Linde K, Allais G, Brinkhaus B, et al. Acupuncture for the prevention of episodic migraine. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(6):CD001218.

32. Lin X, Huang K, Zhu G, et al. The effects of acupuncture on chronic knee pain due to osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98:1578-1585.

33. Deare JC, Zheng Z, Xue CC, et al. Acupuncture for treating fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(5):CD007070.

34. Salamh P, Cook C, Reiman MP, et al. Treatment effectiveness and fidelity of manual therapy to the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Musculoskeletal Care. 2017;15:238-248.

35. Posadzki P. Is spinal manipulation effective for pain? An overview of systematic reviews. Pain Med. 2012;13:754-761.

36. Perlman AI, Ali A, Njike VY, et al. Massage therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized dose-finding trial. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30248.

37. Kalichman L. Massage therapy for fibromyalgia symptoms. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1151-1157.

38. Manheimer E, Cheng K, Linde K, et al. Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD001977.

39. Somers TJ, Wren AA, Shelby RA. The context of pain in arthritis: self-efficacy for managing pain and other symptoms. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16:502-508.

40. Laerum E, Indahl A, Skouen JS. What is “the good back-consultation”? A combined qualitative and quantitative study of chronic low back pain patients’ interaction with and perceptions of consultations with specialists. J Rehabil Med. 2006;38:255-262.

1. Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al, for the Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Int Med. 2017;166:514-530.

2. Ebell MH, Siwek J, Weiss BD, et al. Strength of recommendation taxonomy (SORT): a patient-centered approach to grading evidence in the medical literature. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:548-556.

3. Bidonde J, Busch AJ, Schachter CL, et al. Aerobic exercise training for adults with fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;(6):CD012700.

4. Wieland LS, Skoetz N, Pilkington K, et al. Yoga treatment for chronic non-specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev: 2017;(1):CD010671.

5. Chou R, Deyo R, Friedly J, et al. Nonpharmacologic therapies for low back pain: a systematic review for an American College of Physicians Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166:493-505.

6. Hall A, Copsey B, Richmond H, et al. Effectiveness of tai chi for chronic musculoskeletal pain conditions: updated systematic review and meta-analysis. Phys Ther. 2017;97:227-238.

7. Ye J, Cai S, Zhong W, et al. Effects of tai chi for patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. J Phys Ther Sci. 2014;26:1133-1137.

8. Wang C, Schmid CH, Iversen MD, et al. Comparative effectiveness of tai chi versus physical therapy for knee osteoarthritis. Ann Int Med. 2016;165:77-86.

9. Brosseau L, Taki J, Desjardins B, et al. The Ottawa panel clinical practice guidelines for the management of knee osteoarthritis. Part two: strengthening exercise programs. Clin Rehabil. 2017;31:596-611.

10. Busch AJ, Webber SC, Richards RS, et al. Resistance exercise training for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(12):CD010884.

11. Bidonde J, Busch AJ, Webber SC, et al. Aquatic exercise training for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(10):CD011336.

12. Kan L, Zhang J, Yang Y, et al. The effects of yoga on pain, mobility, and quality of life in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a systematic review. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2016;2016:6016532.

13. Langhorst J, Klose P, Dobos GJ, et al. Efficacy and safety of meditative movement therapies in fibromyalgia syndrome: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:193-207.

14. Flor H. Cortical reorganisation and chronic pain: implications for rehabilitation. J Rehabil Med. 2003;(41 Suppl):66-72.

15. Williams AC, Eccleston C, Morley S. Psychological therapies for the management of chronic pain (excluding headache) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;(11):CD007407.

16. Eccleston C, Fisher E, Craig L, et al. Psychological therapies (internet-delivered) for the management of chronic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(2):CD010152.

17. Bernardy K, Klose P, Busch AJ, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapies for fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(9):CD009796.

18. Shull PB, Silder A, Shultz R, et al. Six-week gait retraining program reduces knee adduction moment, reduces pain, and improves function for individuals with medial compartment knee osteoarthritis. J Orthop Res. 2013;31:1020-1025.

19. Henschke N, Ostelo RW, van Tulder MW, et al. Behavioural treatment for chronic low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(7):CD002014.

20. Glombiewski JA, Sawyer AT, Gutermann J, et al. Psychological treatments for fibromyalgia: a meta-analysis. Pain. 2010;151:280-295.

21. Lee AC, Harvey WF, Price LL, et al. Mindfulness is associated with psychological health and moderates pain in knee osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage. 2017;25:824-831.

22. Lauche R, Cramer H, Dobos G, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of mindfulness-based stress reduction for the fibromyalgia syndrome. J Psychosom Res. 2013;75:500-510.

23. Gay MC, Philippot P, Luminet O. Differential effectiveness of psychological interventions for reducing osteoarthritis pain: a comparison of Erickson hypnosis and Jacobson relaxation. Eur J Pain. 2002;6:1-16.

24. Meeus M, Nijs J, Vanderheiden T, et al. The effect of relaxation therapy on autonomic functioning, symptoms and daily functioning, in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome or fibromyalgia: a systematic review. Clin Rehabil. 2015;29:221-233.

25. Briani RV, Ferreira AS, Pazzinatto MF, et al. What interventions can improve quality of life or psychosocial factors of individuals with knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review with meta-analysis of primary outcomes from randomised controlled trials. Br J Sports Med. 2018. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2017-098099.

26. Glombiewski JA, Bernardy K, Häuser W. Efficacy of EMG- and EEG-biofeedback in fibromyalgia syndrome: a meta-analysis and a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:962741.

27. Hilton L, Hempel S, Ewing BA, et al. Mindfulness meditation for chronic pain: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Behav Med. 2017;51:199-213.

28. Kwekkeboom KL, Gretarsdottir E. Systematic review of relaxation interventions for pain. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2006;38:269-277.

29. Paige NM, Miake-Lye IM, Booth MS, et al. Association of spinal manipulative therapy with clinical benefit and harm for acute low back pain. Systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2017;317:1451-1460.

30. Furlan AD, Giraldo M, Baskwill A, et al. Massage for low-back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;(9):CD001929.

31. Linde K, Allais G, Brinkhaus B, et al. Acupuncture for the prevention of episodic migraine. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016;(6):CD001218.

32. Lin X, Huang K, Zhu G, et al. The effects of acupuncture on chronic knee pain due to osteoarthritis: a meta-analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2016;98:1578-1585.

33. Deare JC, Zheng Z, Xue CC, et al. Acupuncture for treating fibromyalgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(5):CD007070.

34. Salamh P, Cook C, Reiman MP, et al. Treatment effectiveness and fidelity of manual therapy to the knee: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Musculoskeletal Care. 2017;15:238-248.

35. Posadzki P. Is spinal manipulation effective for pain? An overview of systematic reviews. Pain Med. 2012;13:754-761.

36. Perlman AI, Ali A, Njike VY, et al. Massage therapy for osteoarthritis of the knee: a randomized dose-finding trial. PLoS One. 2012;7:e30248.

37. Kalichman L. Massage therapy for fibromyalgia symptoms. Rheumatol Int. 2010;30:1151-1157.

38. Manheimer E, Cheng K, Linde K, et al. Acupuncture for peripheral joint osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;(1):CD001977.

39. Somers TJ, Wren AA, Shelby RA. The context of pain in arthritis: self-efficacy for managing pain and other symptoms. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2012;16:502-508.

40. Laerum E, Indahl A, Skouen JS. What is “the good back-consultation”? A combined qualitative and quantitative study of chronic low back pain patients’ interaction with and perceptions of consultations with specialists. J Rehabil Med. 2006;38:255-262.

From The Journal of Family Practice | 2018;67(8):474-477,480-483.

PRACTICE RECOMMENDATIONS

› Recommend tai chi as an exercise modality for patients with osteoarthritis. A

› Recommend mindfulness training for patients with chronic low back pain (LBP). A

› Recommend a trial of either acupuncture or spinal manipulation for patients with chronic LBP. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Acupuncture for pain: 7 questions answered

An estimated 39.4 million US adults suffer from persistent pain,1 and the National Institutes of Health indicate that pain affects more Americans than diabetes, heart disease, and cancer combined.2

As physicians, we know that conventional options to manage chronic pain leave much to be desired and that more evidence-based treatment options are sorely needed. Patients know this, too, and turn to complementary therapies for pain more than for any other diagnosis.3

Case in point: The use of acupuncture is growing. Its use in the United States tripled between 1997 and 2007.4 In addition, the research base for acupuncture is rapidly expanding. From 1991 to 2009, nearly 4000 acupuncture research studies were published, with studies on pain accounting for 41% of the acupuncture literature.4

But acupuncture is not without controversy. This is due to a lack of a universally accepted biologic mechanism, theories of use and efficacy based in an alternative medical system (traditional Chinese medicine [TCM]), and conflicting views of the evidence.

This article will help make sense of this growing body of knowledge by summarizing the latest evidence and addressing 7 common questions about acupuncture for pain conditions. Applying this information will give you the confidence to counsel patients appropriately and decide if acupuncture fits within their pain management plan.

1. What is acupuncture and how does it work?

Acupuncture, which has a 2000-year history of use, involves inserting needles at various points throughout the body to promote healing and improve function. Although acupuncture represents one piece of TCM (which is a holistic system that also includes herbal medicine, nutrition, meditation, and movement), it is often offered as an independent therapy.

Acupuncture point locations are determined either by using an underlying theoretical framework, such as TCM, or by using anatomic structures, such as muscular trigger points. Providers today often employ a hybrid approach when delivering acupuncture treatment. That is, practitioners may choose point locations based on TCM, but they may combine the practice with local treatments that are based on current knowledge of anatomy. For example, a patient presenting with low back pain may be treated utilizing traditional points located near the ankle and knee, and also by needling active trigger points in the quadratus lumborum muscle.

The mechanism of action. One of the reasons for the continuing controversy surrounding acupuncture is the lack of a clear understanding of its underlying mechanism of action. For centuries the “how” of acupuncture has been explained in poetic terms such as yin, yang, and qi. Only in the past half-century have we begun investigating the potential biologic mechanisms responsible for the physiologic effects seen with acupuncture treatment.

While research has uncovered several interesting theories, how these mechanisms interact to produce therapeutic effects is still unclear. However, looking at various components of the nervous system helps to provide some insight.

Consider the nervous system. One way to conceptualize the mechanisms of acupuncture is to consider the various levels of the nervous system and how each level is affected. In the central nervous system, needling an acupuncture point stimulates the natural endorphin system, altering the pain sensation.5 This effect is reversible with naloxone in animal models, indicating that blocking the endorphin system interferes with the analgesic benefits of acupuncture.5

Serotonergic systems are also involved centrally. Functional magnetic resonance imaging studies have shown that needling specific acupuncture points modulates areas of the brain.

In the spinal cord, the gate control theory is believed to play a role. (The gate control theory puts forth that nonpainful input closes the “gates” to painful input, which prevents pain sensations from traveling to the central nervous system.) Modulation of sensory input occurs at the level of the dorsal horn of the spinal cord during an acupuncture treatment, which can affect the physiologic pain response.6 Opioid receptors are also affected at the spinal cord level.7

Lastly, multiple chemicals released peripherally, including interleukins, substance P, and adenosine, appear to contribute to acupuncture’s analgesia.6 We know this because a local anesthetic injected around a peripheral nerve at an acupoint blocks the analgesic effect of acupuncture.8 Taken together, acupuncture treatment produces physiologic changes in the brain, spinal cord, and at the periphery, making it a truly unique therapeutic modality.

2. Is acupuncture an effective treatment for pain?

Yes, but before we look at the individual studies, it is important to mention some of the shortcomings of the research to date. First, acupuncture trials lack a standard sham control intervention. Some sham treatments involve skin penetration, while others do not. This has led to controversy regarding whether the sham interventions themselves are physiologically active, thus lessening the magnitude of effect for acupuncture. This is a point of contention in the acupuncture literature and a factor to consider when deciding if results have clinical significance.

In addition, the acupuncturist providing treatment in a trial is typically unblinded. This is also true of trials measuring other physical modalities, but it contributes to the debate surrounding the magnitude of placebo response in acupuncture studies.

Finally, many randomized trials involving acupuncture have had low methodologic quality. Fortunately, there are now several high-quality systematic reviews that have attempted to filter out the lower-quality research and provide a better representation of the evidence (TABLE9-14). A discussion of them follows.

General chronic pain. A 2012 meta-analysis15 evaluated the effectiveness of acupuncture for the treatment of chronic pain with one of 4 etiologies: nonspecific back or neck pain, chronic headache, osteoarthritis, and shoulder pain. This analysis attempted to control for the high variability of study quality in the acupuncture literature by including only studies of high methodologic character. The final analysis included 29 randomized controlled trials (N=17,922). The authors concluded that acupuncture was superior to both no acupuncture and sham (placebo) acupuncture for all pain conditions in the study. The average effect size was 0.5 standard deviations on a 10-point scale. The authors considered this to be clinically relevant, although the magnitude of benefit was modest.15

Low back pain. A 2017 systematic review by Chou et al9 evaluated 32 trials (N=5931) reviewing acupuncture for the treatment of chronic low back pain. This review found acupuncture was associated with lower pain intensity and improved function in the short term when compared with no treatment. And while acupuncture was associated with lower pain intensity when compared with a sham control, there was no difference in function between the 2 groups. Of note, 3 of the included trials compared acupuncture to standard medications used in the treatment of low back pain and found acupuncture to be superior in terms of both pain reduction and improved function.9

The authors of a 2008 systematic review that evaluated 23 trials (N=6359)10 similarly concluded that there is moderate evidence for the use of acupuncture (compared to no treatment) for the treatment of nonspecific low back pain, but did not find evidence that acupuncture was superior to sham controls.10 The 2017 American College of Physicians clinical practice guidelines support the use of acupuncture for the treatment of chronic low back pain.16