User login

The new anterior repair

For more than 100 years, gynecologic surgeons have been taught that the vaginal defects causing anterior and posterior vaginal prolapse result either from generalized midline stretching or thinning of the pubocervical fascia, or from lateral or paravaginal injuries.

The pubocervical fascia is a common surgical term for the fibromuscular coat of the vaginal epithelium. Histologically, it is indistinguishable from the deep vaginal wall and does not look like a distinct fascial layer. Clinically, however, it can be identified both abdominally and vaginally, and surgically, it can be dissected from the underlying fibromuscular tissue of the vagina in the vesicovaginal space via the vaginal approach.

A trapezoid-shaped structure of pubocervical fascia serves as a kind of hammock on which the bladder is believed to passively rest. Some believe that visceral bladder connective tissue is the supportive tissue for the bladder, but most refer to this connective tissue as pubocervical fascia – even though usage of the term is not quite anatomically correct and is not used consistently in the literature.

The true pubocervical fascia extends from the pubic bone anteriorly and laterally to the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis. Its proximal posterior edge is attached to the pericervical ring. This supportive fascia is where the defects responsible for anterior-wall prolapse have traditionally been believed to occur.

Midline plication, as well as paravaginal repair involving lateral attachment of the vagina to the arcus, have thus been the surgical approaches of choice for anterior-wall prolapse and cystocele. We have relied on these approaches despite recurrence rates of 40%-60% with traditional colporrhaphy and up to 50% with paravaginal repairs.

For many years, these two theories about the etiology of anterior vaginal-wall prolapse and cystoceles seemed to me to be in disagreement with each other when it comes to inherent mechanisms of bladder prolapse and anterior vaginal-wall prolapse. I have wondered, what really causes bladder prolapse and why has recurrence of cystocele been the Achilles’ heel of pelvic reconstructive surgery?

In the past several decades, Dr. A.C. Richardson described several defects in the pubocervical fascia that he believed were associated with cystoceles. Later on in his career and life, he taught that bladder prolapse was the result of distinct detachments or site-specific defects in the support structures from the pericervical ring.

Reconstructing the pericervical ring and its attachments, he reasoned, would restore normal anatomy and repair bladder prolapse. Dr. Richardson’s later conclusions were never published, however, and midline plication and paravaginal repairs have remained the mainstays of bladder prolapse and anterior vaginal wall prolapse.

In the meantime, a firm understanding of exactly how vaginal birth affects the supportive structure of the bladder eluded us. It has long been believed that vaginal birth trauma contributes to the likelihood of symptomatic prolapse occurring, yet there was never any proof as to how and when the stress of vaginal birth causes pubocervical fascial injury. Nor was there any proof as to the location and direction of tears. Without accurately identifying specific damage patterns, one cannot recognize true defects that need to be repaired.

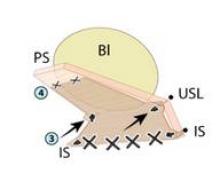

With the help of biomechanical engineers and biomechanical modeling, my colleagues at Atlanta’s Emory University and I found that the superior-to-inferior direction of the sheer stress and strain caused by both fetal descent and internal rotation of the fetal head causes tears in the pubocervical fascia that run in the transverse direction at the level of and from the pericervical ring – not vertically in the midline or laterally (paravaginally) as many had theorized.

Then, during cadaver dissections and surgical repairs of bladder prolapse, we identified the bladder protruding/herniating through the separation of the pubocervical fascia from the pericervical ring.

A true cystocele, we now know, is the result of a transverse defect that separates the pubocervical fascia from the pericervical ring. A paravaginal defect, on the other hand, can cause the anterior vaginal wall to prolapse, but it is not the cause of bladder prolapse. There is an important distinction to be made between these two entities.

Our approach to bladder prolapse, therefore, requires a transverse defect repair. We have developed a surgical technique that appears to successfully correct the defect by reattaching the pubocervical fascia to its original supportive structures, the pericervical ring, and the retroperitoneal uterosacral ligaments as they insert into the sacral peritoneum.

Surgical Technique

Our vaginal surgical procedure was developed to 1) correctly identify the defect causing a cystocele and to identify the bladder protruding through the defect, and 2) repair the defect by reattaching the pubocervical fascia to its original supportive structures.

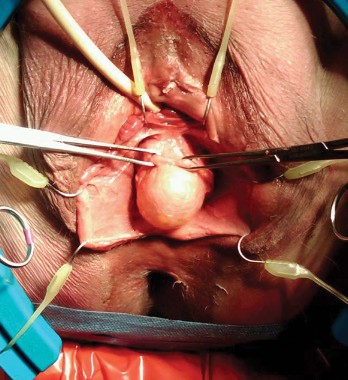

A full-thickness midline incision of the anterior vaginal epithelium is performed to enter the vesicovaginal space. The incision is carried up to the posterior urethral fold, and the vaginal epithelium is retracted laterally using a self-retaining ring retractor with hooks; this fully exposes the vesicovaginal space and the pubocervical fascia. The hooks attached to the retractor provide a level of traction and counter retraction for dissection and continual exposure of the surgical field that is hard to achieve with Allis clamps held by assistants. (We use a Lone Star ring retractor made by CooperSurgical, Trumbull, Conn.)

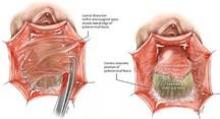

The pubocervical fascia is dissected and separated from the underside of the vaginal epithelium without splitting the vagina, as is done using traditional methods for midline plication. (See figure 8A.) The scissors are spread apart in the avascular lateral retroperitoneal space beneath the pubocervical fascia, and used to separate the fascia from the undersurface of the vagina to the pubic ramus. This is repeated on the other side of the dissection.

The surgeon can recognize the pubocervical fascia by its trapezoidal shape. Once the entire trapezoidal pubocervical fascia is identified, the presence of midline, paravaginal, or transverse defects can be identified and confirmed. (See figure 8B.)

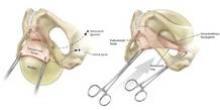

In the absence of any midline or paravaginal defects with bladder protrusion or herniation, the possibility of a transverse defect can be evaluated by identifying the base of the pubocervical fascia. At this point, connective tissue adhesions are often seen between the pubocervical fascia and the prolapsed bladder and vagina. (See figure 9A.) We believe this is adhesive scar tissue that forms naturally after the trauma and mechanical damage of vaginal birth; its existence has not been truly recognized and/or well appreciated in the past.

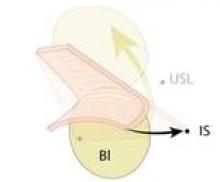

When the adhesive scar is excised, the pubocervical fascia is freed up and can be easily separated from the bladder and vagina. (See figure 9B.) Allis clamps are placed on the lateral aspects of the pubocervical fascia and are lifted superiorly to expose the prolapsed bladder. (See figure 9C.) It is apparent at this point where the pubocervical fascia was originally attached to the pericervical ring. Correction of the bladder herniation can be demonstrated if the pubocervical fascia is elevated apically toward the pericervical ring (its previous attachment) and the retroperitoneal uterosacral ligaments. (See figure 9D.)

Permanent sutures of #0 Ethibond (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, Somerville, N.J.) are placed into each iliococcygeus fascia, or prespinous fascia, inferior to the ischial spine.

A suture of # 2-0 Ethibond is placed into each retroperitoneal uterosacral ligament as it attaches to the sacral periosteum at the level of S-2 or S-3 – a retroperitoneal uterosacral colpopexy. To do this, we use a pelvic reconstructive rectal pouch (American Medical Systems, Minnetonka, Minn.) that enables the index finger to be placed into the rectum for examination and palpation without contamination. The retroperitoneal uterosacral ligament is palpated at the level of the sacrum, where it attaches to the sacral periosteum, and a long Allis clamp is used to grasp the ligament. Each suture is placed from lateral to medial either through or around the ligament to avoid any entrapment of the ureter.

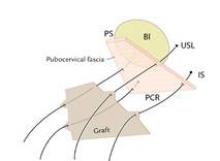

These sutures are held for placement into a piece of Surgisis Biodesign graft for anterior repair (Cook Medical, Bloomington, Ind.) that has been precut into a trapezoidal shape to fit the trapezoidal dissection of the pubocervical fascia.

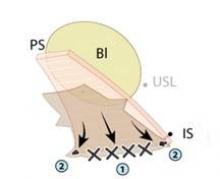

The uterosacral sutures are placed into the superior nubbins on the lateral side of the graft and are held, and the prespinous (iliococcygeus) sutures of #0 Ethibond are placed through the graft’s lower nubbins and held. (See figure 11A.). We then place several sutures of #2-0 Ethibond into the base of the graft, then through the pubocervical fascia, and then the pericervical ring; tying these sutures repairs the transverse defect. (See figure 11B.) The lateral sutures are then tied, beginning with the prespinous sutures.

The graft is attached distally to the periurethral connective tissue with #2-0 Vicryl so that the graft lays flat against the pubocervical fascia. The bladder is now back in its normal anatomic position. (See figures 11C and 11D.)

Excess vaginal mucosa is then excised, and the vagina is closed in a running fashion with #2-0 Vicryl (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, Somerville, N.J.). An intraoperative cystoscopy is performed to document ureteral patency.

The Surgisis graft material is a biologic, recently Food and Drug Administration–approved graft that promotes tissue remodeling. I like using it because it safely provides more strength to the pubocervical fascia before it dissolves in 3-6 months, but the repair can be done alternatively without the graft – with sutures alone.

In our patient population of more than 500 patients followed for 24 months, we have had excellent results with 92% cure rate with sutures and 95% cure rates with Surgisis Biodesign. Some of these patients had previously failed midline plication and paravaginal repairs; the others had stage III or stage IV prolapse and had not undergone prior surgical repairs.

Surgeons who have been taught this new anterior repair have been excited and have found the technique easy to learn. However, only multicenter studies, currently in progress, and time will tell if this new technique will replace traditional anterior colporrhaphy.

Dr. Kovac is emeritus distinguished professor of gynecologic surgery at Emory University, Atlanta. He said he has no disclosures. To view a video of the surgery, visit SurgeryU at www.aagl.org/obgyn-news.

For more than 100 years, gynecologic surgeons have been taught that the vaginal defects causing anterior and posterior vaginal prolapse result either from generalized midline stretching or thinning of the pubocervical fascia, or from lateral or paravaginal injuries.

The pubocervical fascia is a common surgical term for the fibromuscular coat of the vaginal epithelium. Histologically, it is indistinguishable from the deep vaginal wall and does not look like a distinct fascial layer. Clinically, however, it can be identified both abdominally and vaginally, and surgically, it can be dissected from the underlying fibromuscular tissue of the vagina in the vesicovaginal space via the vaginal approach.

A trapezoid-shaped structure of pubocervical fascia serves as a kind of hammock on which the bladder is believed to passively rest. Some believe that visceral bladder connective tissue is the supportive tissue for the bladder, but most refer to this connective tissue as pubocervical fascia – even though usage of the term is not quite anatomically correct and is not used consistently in the literature.

The true pubocervical fascia extends from the pubic bone anteriorly and laterally to the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis. Its proximal posterior edge is attached to the pericervical ring. This supportive fascia is where the defects responsible for anterior-wall prolapse have traditionally been believed to occur.

Midline plication, as well as paravaginal repair involving lateral attachment of the vagina to the arcus, have thus been the surgical approaches of choice for anterior-wall prolapse and cystocele. We have relied on these approaches despite recurrence rates of 40%-60% with traditional colporrhaphy and up to 50% with paravaginal repairs.

For many years, these two theories about the etiology of anterior vaginal-wall prolapse and cystoceles seemed to me to be in disagreement with each other when it comes to inherent mechanisms of bladder prolapse and anterior vaginal-wall prolapse. I have wondered, what really causes bladder prolapse and why has recurrence of cystocele been the Achilles’ heel of pelvic reconstructive surgery?

In the past several decades, Dr. A.C. Richardson described several defects in the pubocervical fascia that he believed were associated with cystoceles. Later on in his career and life, he taught that bladder prolapse was the result of distinct detachments or site-specific defects in the support structures from the pericervical ring.

Reconstructing the pericervical ring and its attachments, he reasoned, would restore normal anatomy and repair bladder prolapse. Dr. Richardson’s later conclusions were never published, however, and midline plication and paravaginal repairs have remained the mainstays of bladder prolapse and anterior vaginal wall prolapse.

In the meantime, a firm understanding of exactly how vaginal birth affects the supportive structure of the bladder eluded us. It has long been believed that vaginal birth trauma contributes to the likelihood of symptomatic prolapse occurring, yet there was never any proof as to how and when the stress of vaginal birth causes pubocervical fascial injury. Nor was there any proof as to the location and direction of tears. Without accurately identifying specific damage patterns, one cannot recognize true defects that need to be repaired.

With the help of biomechanical engineers and biomechanical modeling, my colleagues at Atlanta’s Emory University and I found that the superior-to-inferior direction of the sheer stress and strain caused by both fetal descent and internal rotation of the fetal head causes tears in the pubocervical fascia that run in the transverse direction at the level of and from the pericervical ring – not vertically in the midline or laterally (paravaginally) as many had theorized.

Then, during cadaver dissections and surgical repairs of bladder prolapse, we identified the bladder protruding/herniating through the separation of the pubocervical fascia from the pericervical ring.

A true cystocele, we now know, is the result of a transverse defect that separates the pubocervical fascia from the pericervical ring. A paravaginal defect, on the other hand, can cause the anterior vaginal wall to prolapse, but it is not the cause of bladder prolapse. There is an important distinction to be made between these two entities.

Our approach to bladder prolapse, therefore, requires a transverse defect repair. We have developed a surgical technique that appears to successfully correct the defect by reattaching the pubocervical fascia to its original supportive structures, the pericervical ring, and the retroperitoneal uterosacral ligaments as they insert into the sacral peritoneum.

Surgical Technique

Our vaginal surgical procedure was developed to 1) correctly identify the defect causing a cystocele and to identify the bladder protruding through the defect, and 2) repair the defect by reattaching the pubocervical fascia to its original supportive structures.

A full-thickness midline incision of the anterior vaginal epithelium is performed to enter the vesicovaginal space. The incision is carried up to the posterior urethral fold, and the vaginal epithelium is retracted laterally using a self-retaining ring retractor with hooks; this fully exposes the vesicovaginal space and the pubocervical fascia. The hooks attached to the retractor provide a level of traction and counter retraction for dissection and continual exposure of the surgical field that is hard to achieve with Allis clamps held by assistants. (We use a Lone Star ring retractor made by CooperSurgical, Trumbull, Conn.)

The pubocervical fascia is dissected and separated from the underside of the vaginal epithelium without splitting the vagina, as is done using traditional methods for midline plication. (See figure 8A.) The scissors are spread apart in the avascular lateral retroperitoneal space beneath the pubocervical fascia, and used to separate the fascia from the undersurface of the vagina to the pubic ramus. This is repeated on the other side of the dissection.

The surgeon can recognize the pubocervical fascia by its trapezoidal shape. Once the entire trapezoidal pubocervical fascia is identified, the presence of midline, paravaginal, or transverse defects can be identified and confirmed. (See figure 8B.)

In the absence of any midline or paravaginal defects with bladder protrusion or herniation, the possibility of a transverse defect can be evaluated by identifying the base of the pubocervical fascia. At this point, connective tissue adhesions are often seen between the pubocervical fascia and the prolapsed bladder and vagina. (See figure 9A.) We believe this is adhesive scar tissue that forms naturally after the trauma and mechanical damage of vaginal birth; its existence has not been truly recognized and/or well appreciated in the past.

When the adhesive scar is excised, the pubocervical fascia is freed up and can be easily separated from the bladder and vagina. (See figure 9B.) Allis clamps are placed on the lateral aspects of the pubocervical fascia and are lifted superiorly to expose the prolapsed bladder. (See figure 9C.) It is apparent at this point where the pubocervical fascia was originally attached to the pericervical ring. Correction of the bladder herniation can be demonstrated if the pubocervical fascia is elevated apically toward the pericervical ring (its previous attachment) and the retroperitoneal uterosacral ligaments. (See figure 9D.)

Permanent sutures of #0 Ethibond (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, Somerville, N.J.) are placed into each iliococcygeus fascia, or prespinous fascia, inferior to the ischial spine.

A suture of # 2-0 Ethibond is placed into each retroperitoneal uterosacral ligament as it attaches to the sacral periosteum at the level of S-2 or S-3 – a retroperitoneal uterosacral colpopexy. To do this, we use a pelvic reconstructive rectal pouch (American Medical Systems, Minnetonka, Minn.) that enables the index finger to be placed into the rectum for examination and palpation without contamination. The retroperitoneal uterosacral ligament is palpated at the level of the sacrum, where it attaches to the sacral periosteum, and a long Allis clamp is used to grasp the ligament. Each suture is placed from lateral to medial either through or around the ligament to avoid any entrapment of the ureter.

These sutures are held for placement into a piece of Surgisis Biodesign graft for anterior repair (Cook Medical, Bloomington, Ind.) that has been precut into a trapezoidal shape to fit the trapezoidal dissection of the pubocervical fascia.

The uterosacral sutures are placed into the superior nubbins on the lateral side of the graft and are held, and the prespinous (iliococcygeus) sutures of #0 Ethibond are placed through the graft’s lower nubbins and held. (See figure 11A.). We then place several sutures of #2-0 Ethibond into the base of the graft, then through the pubocervical fascia, and then the pericervical ring; tying these sutures repairs the transverse defect. (See figure 11B.) The lateral sutures are then tied, beginning with the prespinous sutures.

The graft is attached distally to the periurethral connective tissue with #2-0 Vicryl so that the graft lays flat against the pubocervical fascia. The bladder is now back in its normal anatomic position. (See figures 11C and 11D.)

Excess vaginal mucosa is then excised, and the vagina is closed in a running fashion with #2-0 Vicryl (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, Somerville, N.J.). An intraoperative cystoscopy is performed to document ureteral patency.

The Surgisis graft material is a biologic, recently Food and Drug Administration–approved graft that promotes tissue remodeling. I like using it because it safely provides more strength to the pubocervical fascia before it dissolves in 3-6 months, but the repair can be done alternatively without the graft – with sutures alone.

In our patient population of more than 500 patients followed for 24 months, we have had excellent results with 92% cure rate with sutures and 95% cure rates with Surgisis Biodesign. Some of these patients had previously failed midline plication and paravaginal repairs; the others had stage III or stage IV prolapse and had not undergone prior surgical repairs.

Surgeons who have been taught this new anterior repair have been excited and have found the technique easy to learn. However, only multicenter studies, currently in progress, and time will tell if this new technique will replace traditional anterior colporrhaphy.

Dr. Kovac is emeritus distinguished professor of gynecologic surgery at Emory University, Atlanta. He said he has no disclosures. To view a video of the surgery, visit SurgeryU at www.aagl.org/obgyn-news.

For more than 100 years, gynecologic surgeons have been taught that the vaginal defects causing anterior and posterior vaginal prolapse result either from generalized midline stretching or thinning of the pubocervical fascia, or from lateral or paravaginal injuries.

The pubocervical fascia is a common surgical term for the fibromuscular coat of the vaginal epithelium. Histologically, it is indistinguishable from the deep vaginal wall and does not look like a distinct fascial layer. Clinically, however, it can be identified both abdominally and vaginally, and surgically, it can be dissected from the underlying fibromuscular tissue of the vagina in the vesicovaginal space via the vaginal approach.

A trapezoid-shaped structure of pubocervical fascia serves as a kind of hammock on which the bladder is believed to passively rest. Some believe that visceral bladder connective tissue is the supportive tissue for the bladder, but most refer to this connective tissue as pubocervical fascia – even though usage of the term is not quite anatomically correct and is not used consistently in the literature.

The true pubocervical fascia extends from the pubic bone anteriorly and laterally to the arcus tendineus fascia pelvis. Its proximal posterior edge is attached to the pericervical ring. This supportive fascia is where the defects responsible for anterior-wall prolapse have traditionally been believed to occur.

Midline plication, as well as paravaginal repair involving lateral attachment of the vagina to the arcus, have thus been the surgical approaches of choice for anterior-wall prolapse and cystocele. We have relied on these approaches despite recurrence rates of 40%-60% with traditional colporrhaphy and up to 50% with paravaginal repairs.

For many years, these two theories about the etiology of anterior vaginal-wall prolapse and cystoceles seemed to me to be in disagreement with each other when it comes to inherent mechanisms of bladder prolapse and anterior vaginal-wall prolapse. I have wondered, what really causes bladder prolapse and why has recurrence of cystocele been the Achilles’ heel of pelvic reconstructive surgery?

In the past several decades, Dr. A.C. Richardson described several defects in the pubocervical fascia that he believed were associated with cystoceles. Later on in his career and life, he taught that bladder prolapse was the result of distinct detachments or site-specific defects in the support structures from the pericervical ring.

Reconstructing the pericervical ring and its attachments, he reasoned, would restore normal anatomy and repair bladder prolapse. Dr. Richardson’s later conclusions were never published, however, and midline plication and paravaginal repairs have remained the mainstays of bladder prolapse and anterior vaginal wall prolapse.

In the meantime, a firm understanding of exactly how vaginal birth affects the supportive structure of the bladder eluded us. It has long been believed that vaginal birth trauma contributes to the likelihood of symptomatic prolapse occurring, yet there was never any proof as to how and when the stress of vaginal birth causes pubocervical fascial injury. Nor was there any proof as to the location and direction of tears. Without accurately identifying specific damage patterns, one cannot recognize true defects that need to be repaired.

With the help of biomechanical engineers and biomechanical modeling, my colleagues at Atlanta’s Emory University and I found that the superior-to-inferior direction of the sheer stress and strain caused by both fetal descent and internal rotation of the fetal head causes tears in the pubocervical fascia that run in the transverse direction at the level of and from the pericervical ring – not vertically in the midline or laterally (paravaginally) as many had theorized.

Then, during cadaver dissections and surgical repairs of bladder prolapse, we identified the bladder protruding/herniating through the separation of the pubocervical fascia from the pericervical ring.

A true cystocele, we now know, is the result of a transverse defect that separates the pubocervical fascia from the pericervical ring. A paravaginal defect, on the other hand, can cause the anterior vaginal wall to prolapse, but it is not the cause of bladder prolapse. There is an important distinction to be made between these two entities.

Our approach to bladder prolapse, therefore, requires a transverse defect repair. We have developed a surgical technique that appears to successfully correct the defect by reattaching the pubocervical fascia to its original supportive structures, the pericervical ring, and the retroperitoneal uterosacral ligaments as they insert into the sacral peritoneum.

Surgical Technique

Our vaginal surgical procedure was developed to 1) correctly identify the defect causing a cystocele and to identify the bladder protruding through the defect, and 2) repair the defect by reattaching the pubocervical fascia to its original supportive structures.

A full-thickness midline incision of the anterior vaginal epithelium is performed to enter the vesicovaginal space. The incision is carried up to the posterior urethral fold, and the vaginal epithelium is retracted laterally using a self-retaining ring retractor with hooks; this fully exposes the vesicovaginal space and the pubocervical fascia. The hooks attached to the retractor provide a level of traction and counter retraction for dissection and continual exposure of the surgical field that is hard to achieve with Allis clamps held by assistants. (We use a Lone Star ring retractor made by CooperSurgical, Trumbull, Conn.)

The pubocervical fascia is dissected and separated from the underside of the vaginal epithelium without splitting the vagina, as is done using traditional methods for midline plication. (See figure 8A.) The scissors are spread apart in the avascular lateral retroperitoneal space beneath the pubocervical fascia, and used to separate the fascia from the undersurface of the vagina to the pubic ramus. This is repeated on the other side of the dissection.

The surgeon can recognize the pubocervical fascia by its trapezoidal shape. Once the entire trapezoidal pubocervical fascia is identified, the presence of midline, paravaginal, or transverse defects can be identified and confirmed. (See figure 8B.)

In the absence of any midline or paravaginal defects with bladder protrusion or herniation, the possibility of a transverse defect can be evaluated by identifying the base of the pubocervical fascia. At this point, connective tissue adhesions are often seen between the pubocervical fascia and the prolapsed bladder and vagina. (See figure 9A.) We believe this is adhesive scar tissue that forms naturally after the trauma and mechanical damage of vaginal birth; its existence has not been truly recognized and/or well appreciated in the past.

When the adhesive scar is excised, the pubocervical fascia is freed up and can be easily separated from the bladder and vagina. (See figure 9B.) Allis clamps are placed on the lateral aspects of the pubocervical fascia and are lifted superiorly to expose the prolapsed bladder. (See figure 9C.) It is apparent at this point where the pubocervical fascia was originally attached to the pericervical ring. Correction of the bladder herniation can be demonstrated if the pubocervical fascia is elevated apically toward the pericervical ring (its previous attachment) and the retroperitoneal uterosacral ligaments. (See figure 9D.)

Permanent sutures of #0 Ethibond (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, Somerville, N.J.) are placed into each iliococcygeus fascia, or prespinous fascia, inferior to the ischial spine.

A suture of # 2-0 Ethibond is placed into each retroperitoneal uterosacral ligament as it attaches to the sacral periosteum at the level of S-2 or S-3 – a retroperitoneal uterosacral colpopexy. To do this, we use a pelvic reconstructive rectal pouch (American Medical Systems, Minnetonka, Minn.) that enables the index finger to be placed into the rectum for examination and palpation without contamination. The retroperitoneal uterosacral ligament is palpated at the level of the sacrum, where it attaches to the sacral periosteum, and a long Allis clamp is used to grasp the ligament. Each suture is placed from lateral to medial either through or around the ligament to avoid any entrapment of the ureter.

These sutures are held for placement into a piece of Surgisis Biodesign graft for anterior repair (Cook Medical, Bloomington, Ind.) that has been precut into a trapezoidal shape to fit the trapezoidal dissection of the pubocervical fascia.

The uterosacral sutures are placed into the superior nubbins on the lateral side of the graft and are held, and the prespinous (iliococcygeus) sutures of #0 Ethibond are placed through the graft’s lower nubbins and held. (See figure 11A.). We then place several sutures of #2-0 Ethibond into the base of the graft, then through the pubocervical fascia, and then the pericervical ring; tying these sutures repairs the transverse defect. (See figure 11B.) The lateral sutures are then tied, beginning with the prespinous sutures.

The graft is attached distally to the periurethral connective tissue with #2-0 Vicryl so that the graft lays flat against the pubocervical fascia. The bladder is now back in its normal anatomic position. (See figures 11C and 11D.)

Excess vaginal mucosa is then excised, and the vagina is closed in a running fashion with #2-0 Vicryl (Ethicon, Johnson & Johnson, Somerville, N.J.). An intraoperative cystoscopy is performed to document ureteral patency.

The Surgisis graft material is a biologic, recently Food and Drug Administration–approved graft that promotes tissue remodeling. I like using it because it safely provides more strength to the pubocervical fascia before it dissolves in 3-6 months, but the repair can be done alternatively without the graft – with sutures alone.

In our patient population of more than 500 patients followed for 24 months, we have had excellent results with 92% cure rate with sutures and 95% cure rates with Surgisis Biodesign. Some of these patients had previously failed midline plication and paravaginal repairs; the others had stage III or stage IV prolapse and had not undergone prior surgical repairs.

Surgeons who have been taught this new anterior repair have been excited and have found the technique easy to learn. However, only multicenter studies, currently in progress, and time will tell if this new technique will replace traditional anterior colporrhaphy.

Dr. Kovac is emeritus distinguished professor of gynecologic surgery at Emory University, Atlanta. He said he has no disclosures. To view a video of the surgery, visit SurgeryU at www.aagl.org/obgyn-news.