User login

How often should we check EKGs in patients starting antipsychotic medications?

Determining relative risk with available data

Case

An 88-year-old woman with history of osteoporosis, hyperlipidemia, and a remote myocardial infarction presents to the ED with altered mental status and agitation. The patient is admitted to the medicine service for further management. Her current medications include a thiazide and a statin. Psychiatry is consulted and recommends administering intravenous haloperidol. A baseline EKG shows a corrected QT interval (QTc) of 486 milliseconds (ms). How often should subsequent EKGs be ordered?

Overview of issue

A prolonged QT interval can predispose a patient to dangerous arrhythmias such as Torsades de pointes (TdP), which results in sudden cardiac death in about 10% of cases.1,2 A prolonged QTc interval can be caused by cardiac, renal, or hepatic dysfunction; congenital Long QT Syndrome (LQTS)2; electrolyte abnormalities; or as a result of many drugs, including most antipsychotic medications such as quetiapine, olanzapine, risperidone and haloperidol.

To diminish risk of TdP while taking these medications, it is necessary to monitor the QTc interval. Before commencing a QT-prolonging medication, it is recommended to get a baseline EKG, then perform EKG monitoring after administering the medication.

According to American Heart Association guidelines, a prolonged QT interval is considered more than 460 ms in women or above 450 ms in men.3 If an abnormal rhythm and/or prolonged QTc is detected via EKG monitoring, then the drug dosage can be changed or an alternative therapy selected.4 However, there are no current guidelines recommending how often EKG monitoring should be performed after a QT-prolonging antipsychotic medication is administered on an inpatient medicine unit. Without guidelines, there is potential for health care providers to under- or over-order EKG monitoring, possibly putting patients at risk of TdP or wasting hospital resources, respectively.

Overview of the data

There are currently no universally accepted guidelines regarding inpatient EKG monitoring for patients started on QTc prolonging antipsychotic medications. A 2018 review of the literature surrounding assessment and management of patients on QTc prolonging medications was performed to analyze the available data and make recommendations; notably the evidence was limited as none of the studies were randomized controlled trials.

The authors recommend assessing the drug for QTc prolonging potential, and if possible, choosing alternative treatment in patients with baseline prolonged QTc. If the QT prolonging medication is the best or only option, then the next step is assessing the patient’s risk for QTc prolongation based on that person’s current condition and medical history.5 They recommend using the QTc prolonging risk point system developed by Tisdale and colleagues, which identified patient risk factors for elevated QTc intervals based on EKG findings in cardiac care units at a large tertiary hospital center.6

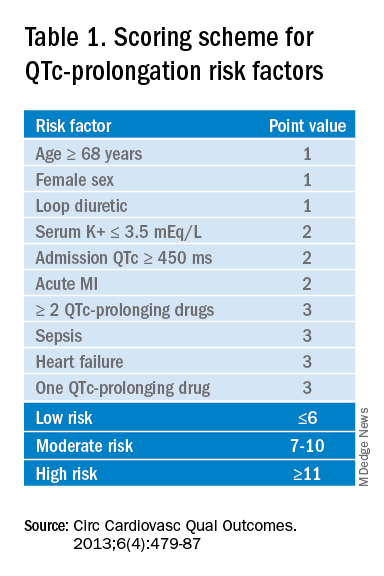

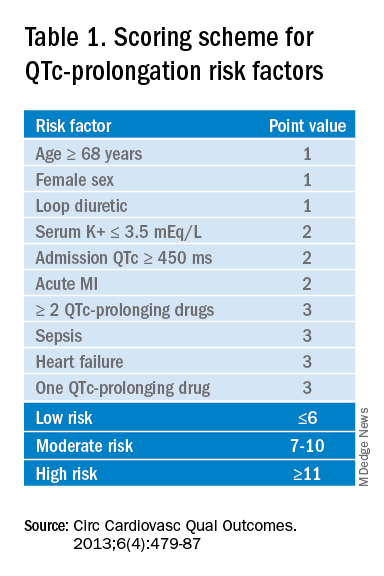

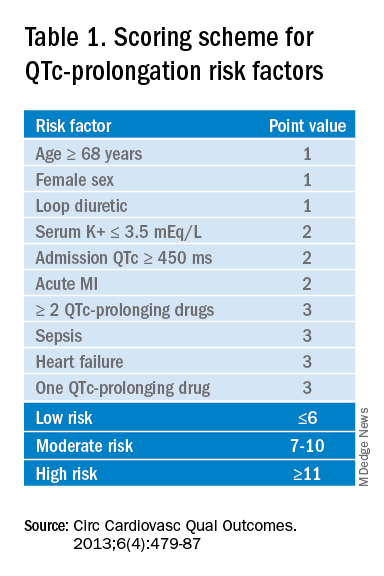

Based on the patient’s demographics, current condition, and medication list, the score can be used to stratify patients into low-, medium-, and high-risk categories (see Table 1).

Risk factors include age over 68 years, female sex, prior MI, concurrent use of other QTc prolonging medications, and sepsis, all of which have differing ability to cause QTc prolongation and thus are weighted differentially. This scoring system is helpful in identifying high risk patients; however, the review does not include recommendations for management of these patients beyond removing the offending drug or monitoring EKGs more aggressively in higher risk patients once identified.6

Low-risk patients can be managed expectantly. If the baseline QTc is < 500 ms, then the provider may administer the medication, but should obtain follow-up EKG monitoring to ensure the QTc does not rise above 500 ms; if it does, a management change is necessitated. For moderate- to high-risk patients with a baseline QTc > 500 ms, they recommend not administering the medication and consulting a cardiologist. The review does not provide a recommendation on how often EKG monitoring should be performed after prescribing an antipsychotic medication in an inpatient setting.5

A 2018 review article explored patient risk factors for a prolonged QTc in the setting of prescribing potentially QTc prolonging antipsychotics.7 The authors reiterate that QTc prolonging risk factors are important considerations when prescribing antipsychotics that can lead to adverse events, though they note that much of the literature associating antipsychotics with negative outcomes consists of case reports in which patients had independent risk factors for development of TdP, such as preexisting ventricular arrhythmias.

In addition, the data regarding the risk of each individual antipsychotic agent are not comprehensive. Some medications that have been deemed “QTc prolonging” were identified as such in only a handful of cases where patients had confounding comorbid risk factors. This raises concern that some medications are being unduly stigmatized in situations where there is little chance of TdP. If there is no equivalent or alternate treatment available, this may lead to an antipsychotic medication being held unnecessarily, which may exacerbate the psychiatric illness.

The authors note that the trend toward ordering baseline EKGs in the inpatient setting following administration of a new antipsychotic may be partly attributed to the ready availability of EKG testing in hospitals. They recommend a baseline EKG to assess the patient’s risk. For most agents, they recommend no further EKG monitoring unless there is a change in patient risk factors. Follow-up EKGs should be done in patients with multiple or significant risk factors to assess their QTc stability. In patients with a QTc > 500 ms on a follow-up EKG, daily monitoring is encouraged alongside reassessment of the current treatment regimen.7

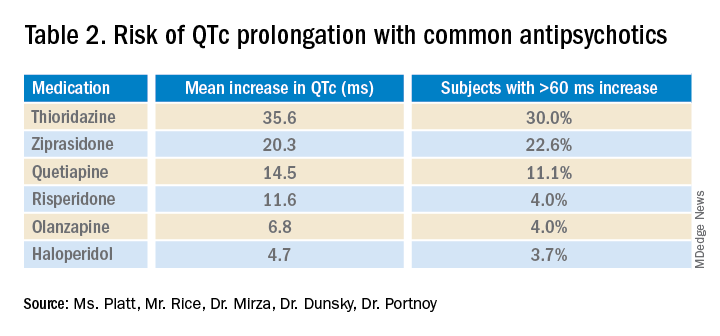

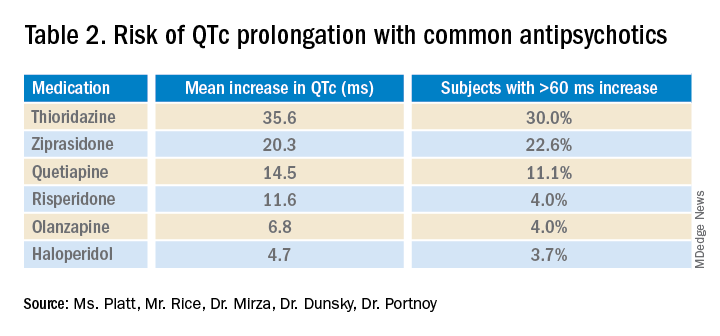

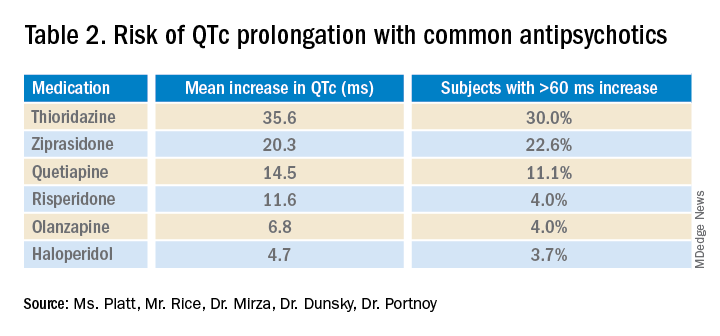

Overall, the current literature suggests that providers should know which antipsychotics carry a risk for QTc prolongation and what other treatment options are available. The risk of QTc prolongation for common antipsychotic agents is provided in Table 2.

Providers should assess their patients’ risk factors for QTc prolongation and order a baseline EKG to help quantify the cardiac risk associated with prescribing the drug. In patients with many risk factors or complicated medication regimens, a follow-up EKG should be performed to assess the new QTc baseline. If the subsequent QTc is > 500 ms, then an alternative medication should be strongly considered. The majority of patients, however, will not have a clinically significant increase in their QTc, in which case there is no need for a change in medication and monitoring frequency can be deescalated.

Application of data to the case

Our 88-year-old patient has multiple risk factors for a prolonged QTc, and according to the Tisdale scoring system is at moderate risk (7-10 points). Her risk of developing TdP increases with the addition of IV haloperidol to her regimen.

Because of her increased risk, it is reasonable to consider alternative management. If she can cooperate with PO medications, then olanzapine could be given, which has a lesser effect on the QTc interval. If unable to take oral medications, she could be given haloperidol intramuscularly, which causes less QTc prolongation than the IV formulation. If an antipsychotic is administered, she should receive EKG monitoring.

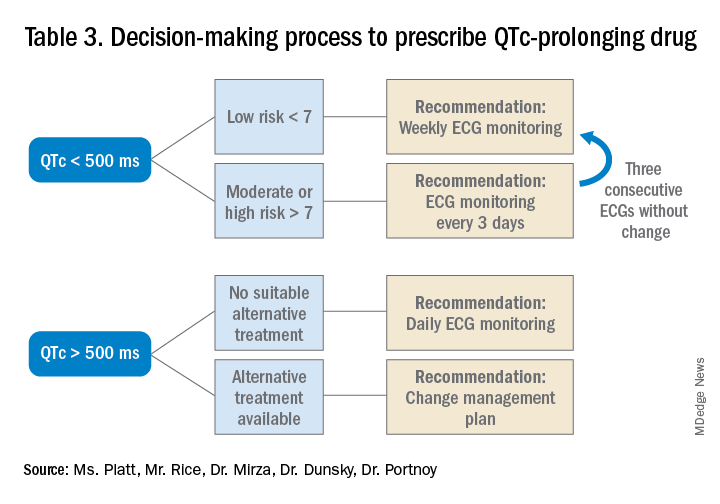

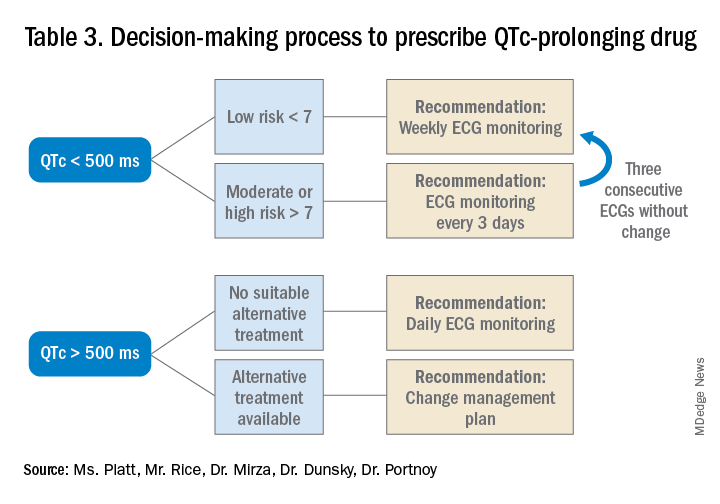

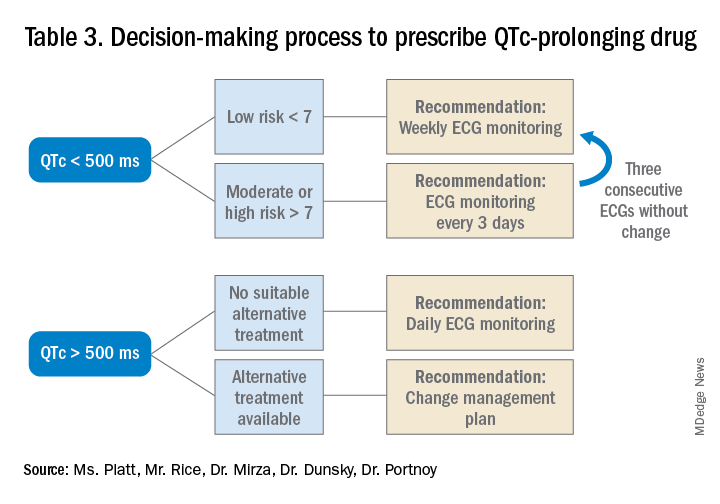

Given the lack of evidence on the optimal monitoring strategy, a protocol should be utilized that balances the ability to capture a clinically meaningful increase in the QTc with appropriate stewardship of resources. Our practice is to initially monitor the EKG every 3 days in moderate- to high-risk patients with baseline QTc < 500 ms. If the QTc remains below 500 ms over three EKGs, then treatment may continue with EKG monitoring weekly while the patient is hospitalized. If the QTc rises above 500 ms, then a management change would be indicated (either dose reduction or a change of agents). If antipsychotic medications are continued, we check the EKG daily while the QTc is >500 ms until there are three unchanged EKGS, and then consider deescalating monitoring to every 3 days.

Bottom line

Prior to prescribing, perform a baseline EKG and assess the patient’s risk of QTc prolongation. If the patient is at increased risk, avoid prescribing QTc prolonging medications where alternatives exist. If a QTc prolonging medication is used in a patient with a moderate- to high-risk score, check an EKG every 3 days or daily if the QTc increases to > 500 ms.

Ms. Platt is a medical student at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. Mr. Rice is a medical student at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Mirza is assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Dunsky is a cardiologist and assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Portnoy is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine.

References

1. Darpö B. Spectrum of drugs prolonging QT interval and the incidence of torsades de pointes. Eur Heart J Supplements. 2001;3(suppl_K):K70-K80. doi: 10.1016/S1520-765X(01)90009-4.

2. Schwartz PJ, Woosley RL. Predicting the unpredictable: Drug-induced QT prolongation and torsades de pointes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(13):1639-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.12.063.

3. Rautaharju PM et al. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram. Part IV: The ST Segment, T and U Waves, and the QT Interval A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Mar 17;53(11):982-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.014.

4. Drew BJ et al. Prevention of torsades de pointes in hospital settings: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2010;121(8):1047-60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192704.

5. Zolezzi M, Cheung L. A literature-based algorithm for the assessment, management, and monitoring of drug-induced QTc prolongation in the psychiatric population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:105-14. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S186474.

6. Tisdale JE et al. Development and validation of a risk score to predict QT interval prolongation in hospitalized patients. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(4):479-87. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000152.

7. Beach SR et al. QT prolongation, torsades de pointes, and psychotropic medications: A 5-year update. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(2):105-22. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.10.009.

Key points

- An increased QTc interval can lead to TdP, ventricular fibrillation and cardiac death.

- The relative risk of each antipsychotic medication should be determined based on available data and the Tisdale scoring system can provide a system to assess a patient’s risk of QTc prolongation.

- Low-risk patients with a baseline QTc <500 ms should receive a baseline EKG and inpatient EKG monitoring weekly while moderate- to high-risk patients should receive EKG monitoring every 3 days.

- A QTc > 500 ms suggests the need for a management change (drug discontinuation, dose reduction, or a switch to another agent). If the antipsychotic is absolutely necessary, perform daily EKG monitoring until there are three unchanged EKGs, and then consider deescalating monitoring to every 3 days.

Additional reading

Beach SR et al. QT Prolongation, torsades de pointes, and psychotropic medications: A 5-year update. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(2):105-22. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.10.009.

Drew BJ et al. Prevention of torsades de pointes in hospital settings: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2010;121(8):1047-60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192704.

Zolezzi M, Cheung L. A literature-based algorithm for the assessment, management, and monitoring of drug-induced QTc prolongation in the psychiatric population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:105-14. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S186474.

Quiz

A 70-year-old male inpatient on furosemide with last known potassium level of 3.3 is going to be started on olanzapine. His baseline EKG has a QTc of 470 ms.

How often should he receive EKG monitoring?

A. Daily

B. Every 3 days

C. Weekly

D. Monthly

Answer (C): He is a low risk patient (6 points: over 70 yrs, loop diuretic, K+< 3.5, QTc > 450 ms), so he should receive weekly EKG monitoring.

Determining relative risk with available data

Determining relative risk with available data

Case

An 88-year-old woman with history of osteoporosis, hyperlipidemia, and a remote myocardial infarction presents to the ED with altered mental status and agitation. The patient is admitted to the medicine service for further management. Her current medications include a thiazide and a statin. Psychiatry is consulted and recommends administering intravenous haloperidol. A baseline EKG shows a corrected QT interval (QTc) of 486 milliseconds (ms). How often should subsequent EKGs be ordered?

Overview of issue

A prolonged QT interval can predispose a patient to dangerous arrhythmias such as Torsades de pointes (TdP), which results in sudden cardiac death in about 10% of cases.1,2 A prolonged QTc interval can be caused by cardiac, renal, or hepatic dysfunction; congenital Long QT Syndrome (LQTS)2; electrolyte abnormalities; or as a result of many drugs, including most antipsychotic medications such as quetiapine, olanzapine, risperidone and haloperidol.

To diminish risk of TdP while taking these medications, it is necessary to monitor the QTc interval. Before commencing a QT-prolonging medication, it is recommended to get a baseline EKG, then perform EKG monitoring after administering the medication.

According to American Heart Association guidelines, a prolonged QT interval is considered more than 460 ms in women or above 450 ms in men.3 If an abnormal rhythm and/or prolonged QTc is detected via EKG monitoring, then the drug dosage can be changed or an alternative therapy selected.4 However, there are no current guidelines recommending how often EKG monitoring should be performed after a QT-prolonging antipsychotic medication is administered on an inpatient medicine unit. Without guidelines, there is potential for health care providers to under- or over-order EKG monitoring, possibly putting patients at risk of TdP or wasting hospital resources, respectively.

Overview of the data

There are currently no universally accepted guidelines regarding inpatient EKG monitoring for patients started on QTc prolonging antipsychotic medications. A 2018 review of the literature surrounding assessment and management of patients on QTc prolonging medications was performed to analyze the available data and make recommendations; notably the evidence was limited as none of the studies were randomized controlled trials.

The authors recommend assessing the drug for QTc prolonging potential, and if possible, choosing alternative treatment in patients with baseline prolonged QTc. If the QT prolonging medication is the best or only option, then the next step is assessing the patient’s risk for QTc prolongation based on that person’s current condition and medical history.5 They recommend using the QTc prolonging risk point system developed by Tisdale and colleagues, which identified patient risk factors for elevated QTc intervals based on EKG findings in cardiac care units at a large tertiary hospital center.6

Based on the patient’s demographics, current condition, and medication list, the score can be used to stratify patients into low-, medium-, and high-risk categories (see Table 1).

Risk factors include age over 68 years, female sex, prior MI, concurrent use of other QTc prolonging medications, and sepsis, all of which have differing ability to cause QTc prolongation and thus are weighted differentially. This scoring system is helpful in identifying high risk patients; however, the review does not include recommendations for management of these patients beyond removing the offending drug or monitoring EKGs more aggressively in higher risk patients once identified.6

Low-risk patients can be managed expectantly. If the baseline QTc is < 500 ms, then the provider may administer the medication, but should obtain follow-up EKG monitoring to ensure the QTc does not rise above 500 ms; if it does, a management change is necessitated. For moderate- to high-risk patients with a baseline QTc > 500 ms, they recommend not administering the medication and consulting a cardiologist. The review does not provide a recommendation on how often EKG monitoring should be performed after prescribing an antipsychotic medication in an inpatient setting.5

A 2018 review article explored patient risk factors for a prolonged QTc in the setting of prescribing potentially QTc prolonging antipsychotics.7 The authors reiterate that QTc prolonging risk factors are important considerations when prescribing antipsychotics that can lead to adverse events, though they note that much of the literature associating antipsychotics with negative outcomes consists of case reports in which patients had independent risk factors for development of TdP, such as preexisting ventricular arrhythmias.

In addition, the data regarding the risk of each individual antipsychotic agent are not comprehensive. Some medications that have been deemed “QTc prolonging” were identified as such in only a handful of cases where patients had confounding comorbid risk factors. This raises concern that some medications are being unduly stigmatized in situations where there is little chance of TdP. If there is no equivalent or alternate treatment available, this may lead to an antipsychotic medication being held unnecessarily, which may exacerbate the psychiatric illness.

The authors note that the trend toward ordering baseline EKGs in the inpatient setting following administration of a new antipsychotic may be partly attributed to the ready availability of EKG testing in hospitals. They recommend a baseline EKG to assess the patient’s risk. For most agents, they recommend no further EKG monitoring unless there is a change in patient risk factors. Follow-up EKGs should be done in patients with multiple or significant risk factors to assess their QTc stability. In patients with a QTc > 500 ms on a follow-up EKG, daily monitoring is encouraged alongside reassessment of the current treatment regimen.7

Overall, the current literature suggests that providers should know which antipsychotics carry a risk for QTc prolongation and what other treatment options are available. The risk of QTc prolongation for common antipsychotic agents is provided in Table 2.

Providers should assess their patients’ risk factors for QTc prolongation and order a baseline EKG to help quantify the cardiac risk associated with prescribing the drug. In patients with many risk factors or complicated medication regimens, a follow-up EKG should be performed to assess the new QTc baseline. If the subsequent QTc is > 500 ms, then an alternative medication should be strongly considered. The majority of patients, however, will not have a clinically significant increase in their QTc, in which case there is no need for a change in medication and monitoring frequency can be deescalated.

Application of data to the case

Our 88-year-old patient has multiple risk factors for a prolonged QTc, and according to the Tisdale scoring system is at moderate risk (7-10 points). Her risk of developing TdP increases with the addition of IV haloperidol to her regimen.

Because of her increased risk, it is reasonable to consider alternative management. If she can cooperate with PO medications, then olanzapine could be given, which has a lesser effect on the QTc interval. If unable to take oral medications, she could be given haloperidol intramuscularly, which causes less QTc prolongation than the IV formulation. If an antipsychotic is administered, she should receive EKG monitoring.

Given the lack of evidence on the optimal monitoring strategy, a protocol should be utilized that balances the ability to capture a clinically meaningful increase in the QTc with appropriate stewardship of resources. Our practice is to initially monitor the EKG every 3 days in moderate- to high-risk patients with baseline QTc < 500 ms. If the QTc remains below 500 ms over three EKGs, then treatment may continue with EKG monitoring weekly while the patient is hospitalized. If the QTc rises above 500 ms, then a management change would be indicated (either dose reduction or a change of agents). If antipsychotic medications are continued, we check the EKG daily while the QTc is >500 ms until there are three unchanged EKGS, and then consider deescalating monitoring to every 3 days.

Bottom line

Prior to prescribing, perform a baseline EKG and assess the patient’s risk of QTc prolongation. If the patient is at increased risk, avoid prescribing QTc prolonging medications where alternatives exist. If a QTc prolonging medication is used in a patient with a moderate- to high-risk score, check an EKG every 3 days or daily if the QTc increases to > 500 ms.

Ms. Platt is a medical student at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. Mr. Rice is a medical student at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Mirza is assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Dunsky is a cardiologist and assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Portnoy is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine.

References

1. Darpö B. Spectrum of drugs prolonging QT interval and the incidence of torsades de pointes. Eur Heart J Supplements. 2001;3(suppl_K):K70-K80. doi: 10.1016/S1520-765X(01)90009-4.

2. Schwartz PJ, Woosley RL. Predicting the unpredictable: Drug-induced QT prolongation and torsades de pointes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(13):1639-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.12.063.

3. Rautaharju PM et al. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram. Part IV: The ST Segment, T and U Waves, and the QT Interval A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Mar 17;53(11):982-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.014.

4. Drew BJ et al. Prevention of torsades de pointes in hospital settings: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2010;121(8):1047-60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192704.

5. Zolezzi M, Cheung L. A literature-based algorithm for the assessment, management, and monitoring of drug-induced QTc prolongation in the psychiatric population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:105-14. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S186474.

6. Tisdale JE et al. Development and validation of a risk score to predict QT interval prolongation in hospitalized patients. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(4):479-87. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000152.

7. Beach SR et al. QT prolongation, torsades de pointes, and psychotropic medications: A 5-year update. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(2):105-22. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.10.009.

Key points

- An increased QTc interval can lead to TdP, ventricular fibrillation and cardiac death.

- The relative risk of each antipsychotic medication should be determined based on available data and the Tisdale scoring system can provide a system to assess a patient’s risk of QTc prolongation.

- Low-risk patients with a baseline QTc <500 ms should receive a baseline EKG and inpatient EKG monitoring weekly while moderate- to high-risk patients should receive EKG monitoring every 3 days.

- A QTc > 500 ms suggests the need for a management change (drug discontinuation, dose reduction, or a switch to another agent). If the antipsychotic is absolutely necessary, perform daily EKG monitoring until there are three unchanged EKGs, and then consider deescalating monitoring to every 3 days.

Additional reading

Beach SR et al. QT Prolongation, torsades de pointes, and psychotropic medications: A 5-year update. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(2):105-22. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.10.009.

Drew BJ et al. Prevention of torsades de pointes in hospital settings: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2010;121(8):1047-60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192704.

Zolezzi M, Cheung L. A literature-based algorithm for the assessment, management, and monitoring of drug-induced QTc prolongation in the psychiatric population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:105-14. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S186474.

Quiz

A 70-year-old male inpatient on furosemide with last known potassium level of 3.3 is going to be started on olanzapine. His baseline EKG has a QTc of 470 ms.

How often should he receive EKG monitoring?

A. Daily

B. Every 3 days

C. Weekly

D. Monthly

Answer (C): He is a low risk patient (6 points: over 70 yrs, loop diuretic, K+< 3.5, QTc > 450 ms), so he should receive weekly EKG monitoring.

Case

An 88-year-old woman with history of osteoporosis, hyperlipidemia, and a remote myocardial infarction presents to the ED with altered mental status and agitation. The patient is admitted to the medicine service for further management. Her current medications include a thiazide and a statin. Psychiatry is consulted and recommends administering intravenous haloperidol. A baseline EKG shows a corrected QT interval (QTc) of 486 milliseconds (ms). How often should subsequent EKGs be ordered?

Overview of issue

A prolonged QT interval can predispose a patient to dangerous arrhythmias such as Torsades de pointes (TdP), which results in sudden cardiac death in about 10% of cases.1,2 A prolonged QTc interval can be caused by cardiac, renal, or hepatic dysfunction; congenital Long QT Syndrome (LQTS)2; electrolyte abnormalities; or as a result of many drugs, including most antipsychotic medications such as quetiapine, olanzapine, risperidone and haloperidol.

To diminish risk of TdP while taking these medications, it is necessary to monitor the QTc interval. Before commencing a QT-prolonging medication, it is recommended to get a baseline EKG, then perform EKG monitoring after administering the medication.

According to American Heart Association guidelines, a prolonged QT interval is considered more than 460 ms in women or above 450 ms in men.3 If an abnormal rhythm and/or prolonged QTc is detected via EKG monitoring, then the drug dosage can be changed or an alternative therapy selected.4 However, there are no current guidelines recommending how often EKG monitoring should be performed after a QT-prolonging antipsychotic medication is administered on an inpatient medicine unit. Without guidelines, there is potential for health care providers to under- or over-order EKG monitoring, possibly putting patients at risk of TdP or wasting hospital resources, respectively.

Overview of the data

There are currently no universally accepted guidelines regarding inpatient EKG monitoring for patients started on QTc prolonging antipsychotic medications. A 2018 review of the literature surrounding assessment and management of patients on QTc prolonging medications was performed to analyze the available data and make recommendations; notably the evidence was limited as none of the studies were randomized controlled trials.

The authors recommend assessing the drug for QTc prolonging potential, and if possible, choosing alternative treatment in patients with baseline prolonged QTc. If the QT prolonging medication is the best or only option, then the next step is assessing the patient’s risk for QTc prolongation based on that person’s current condition and medical history.5 They recommend using the QTc prolonging risk point system developed by Tisdale and colleagues, which identified patient risk factors for elevated QTc intervals based on EKG findings in cardiac care units at a large tertiary hospital center.6

Based on the patient’s demographics, current condition, and medication list, the score can be used to stratify patients into low-, medium-, and high-risk categories (see Table 1).

Risk factors include age over 68 years, female sex, prior MI, concurrent use of other QTc prolonging medications, and sepsis, all of which have differing ability to cause QTc prolongation and thus are weighted differentially. This scoring system is helpful in identifying high risk patients; however, the review does not include recommendations for management of these patients beyond removing the offending drug or monitoring EKGs more aggressively in higher risk patients once identified.6

Low-risk patients can be managed expectantly. If the baseline QTc is < 500 ms, then the provider may administer the medication, but should obtain follow-up EKG monitoring to ensure the QTc does not rise above 500 ms; if it does, a management change is necessitated. For moderate- to high-risk patients with a baseline QTc > 500 ms, they recommend not administering the medication and consulting a cardiologist. The review does not provide a recommendation on how often EKG monitoring should be performed after prescribing an antipsychotic medication in an inpatient setting.5

A 2018 review article explored patient risk factors for a prolonged QTc in the setting of prescribing potentially QTc prolonging antipsychotics.7 The authors reiterate that QTc prolonging risk factors are important considerations when prescribing antipsychotics that can lead to adverse events, though they note that much of the literature associating antipsychotics with negative outcomes consists of case reports in which patients had independent risk factors for development of TdP, such as preexisting ventricular arrhythmias.

In addition, the data regarding the risk of each individual antipsychotic agent are not comprehensive. Some medications that have been deemed “QTc prolonging” were identified as such in only a handful of cases where patients had confounding comorbid risk factors. This raises concern that some medications are being unduly stigmatized in situations where there is little chance of TdP. If there is no equivalent or alternate treatment available, this may lead to an antipsychotic medication being held unnecessarily, which may exacerbate the psychiatric illness.

The authors note that the trend toward ordering baseline EKGs in the inpatient setting following administration of a new antipsychotic may be partly attributed to the ready availability of EKG testing in hospitals. They recommend a baseline EKG to assess the patient’s risk. For most agents, they recommend no further EKG monitoring unless there is a change in patient risk factors. Follow-up EKGs should be done in patients with multiple or significant risk factors to assess their QTc stability. In patients with a QTc > 500 ms on a follow-up EKG, daily monitoring is encouraged alongside reassessment of the current treatment regimen.7

Overall, the current literature suggests that providers should know which antipsychotics carry a risk for QTc prolongation and what other treatment options are available. The risk of QTc prolongation for common antipsychotic agents is provided in Table 2.

Providers should assess their patients’ risk factors for QTc prolongation and order a baseline EKG to help quantify the cardiac risk associated with prescribing the drug. In patients with many risk factors or complicated medication regimens, a follow-up EKG should be performed to assess the new QTc baseline. If the subsequent QTc is > 500 ms, then an alternative medication should be strongly considered. The majority of patients, however, will not have a clinically significant increase in their QTc, in which case there is no need for a change in medication and monitoring frequency can be deescalated.

Application of data to the case

Our 88-year-old patient has multiple risk factors for a prolonged QTc, and according to the Tisdale scoring system is at moderate risk (7-10 points). Her risk of developing TdP increases with the addition of IV haloperidol to her regimen.

Because of her increased risk, it is reasonable to consider alternative management. If she can cooperate with PO medications, then olanzapine could be given, which has a lesser effect on the QTc interval. If unable to take oral medications, she could be given haloperidol intramuscularly, which causes less QTc prolongation than the IV formulation. If an antipsychotic is administered, she should receive EKG monitoring.

Given the lack of evidence on the optimal monitoring strategy, a protocol should be utilized that balances the ability to capture a clinically meaningful increase in the QTc with appropriate stewardship of resources. Our practice is to initially monitor the EKG every 3 days in moderate- to high-risk patients with baseline QTc < 500 ms. If the QTc remains below 500 ms over three EKGs, then treatment may continue with EKG monitoring weekly while the patient is hospitalized. If the QTc rises above 500 ms, then a management change would be indicated (either dose reduction or a change of agents). If antipsychotic medications are continued, we check the EKG daily while the QTc is >500 ms until there are three unchanged EKGS, and then consider deescalating monitoring to every 3 days.

Bottom line

Prior to prescribing, perform a baseline EKG and assess the patient’s risk of QTc prolongation. If the patient is at increased risk, avoid prescribing QTc prolonging medications where alternatives exist. If a QTc prolonging medication is used in a patient with a moderate- to high-risk score, check an EKG every 3 days or daily if the QTc increases to > 500 ms.

Ms. Platt is a medical student at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York. Mr. Rice is a medical student at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Mirza is assistant clinical professor of psychiatry at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Dunsky is a cardiologist and assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine. Dr. Portnoy is a hospitalist and assistant professor at the Icahn School of Medicine.

References

1. Darpö B. Spectrum of drugs prolonging QT interval and the incidence of torsades de pointes. Eur Heart J Supplements. 2001;3(suppl_K):K70-K80. doi: 10.1016/S1520-765X(01)90009-4.

2. Schwartz PJ, Woosley RL. Predicting the unpredictable: Drug-induced QT prolongation and torsades de pointes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2016;67(13):1639-50. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2015.12.063.

3. Rautaharju PM et al. AHA/ACCF/HRS recommendations for the standardization and interpretation of the electrocardiogram. Part IV: The ST Segment, T and U Waves, and the QT Interval A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association Electrocardiography and Arrhythmias Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology; the American College of Cardiology Foundation; and the Heart Rhythm Society Endorsed by the International Society for Computerized Electrocardiology. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009 Mar 17;53(11):982-91. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.12.014.

4. Drew BJ et al. Prevention of torsades de pointes in hospital settings: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2010;121(8):1047-60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192704.

5. Zolezzi M, Cheung L. A literature-based algorithm for the assessment, management, and monitoring of drug-induced QTc prolongation in the psychiatric population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:105-14. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S186474.

6. Tisdale JE et al. Development and validation of a risk score to predict QT interval prolongation in hospitalized patients. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2013;6(4):479-87. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.113.000152.

7. Beach SR et al. QT prolongation, torsades de pointes, and psychotropic medications: A 5-year update. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(2):105-22. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.10.009.

Key points

- An increased QTc interval can lead to TdP, ventricular fibrillation and cardiac death.

- The relative risk of each antipsychotic medication should be determined based on available data and the Tisdale scoring system can provide a system to assess a patient’s risk of QTc prolongation.

- Low-risk patients with a baseline QTc <500 ms should receive a baseline EKG and inpatient EKG monitoring weekly while moderate- to high-risk patients should receive EKG monitoring every 3 days.

- A QTc > 500 ms suggests the need for a management change (drug discontinuation, dose reduction, or a switch to another agent). If the antipsychotic is absolutely necessary, perform daily EKG monitoring until there are three unchanged EKGs, and then consider deescalating monitoring to every 3 days.

Additional reading

Beach SR et al. QT Prolongation, torsades de pointes, and psychotropic medications: A 5-year update. Psychosomatics. 2018;59(2):105-22. doi: 10.1016/j.psym.2017.10.009.

Drew BJ et al. Prevention of torsades de pointes in hospital settings: A scientific statement from the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2010;121(8):1047-60. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.192704.

Zolezzi M, Cheung L. A literature-based algorithm for the assessment, management, and monitoring of drug-induced QTc prolongation in the psychiatric population. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2019;15:105-14. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S186474.

Quiz

A 70-year-old male inpatient on furosemide with last known potassium level of 3.3 is going to be started on olanzapine. His baseline EKG has a QTc of 470 ms.

How often should he receive EKG monitoring?

A. Daily

B. Every 3 days

C. Weekly

D. Monthly

Answer (C): He is a low risk patient (6 points: over 70 yrs, loop diuretic, K+< 3.5, QTc > 450 ms), so he should receive weekly EKG monitoring.