User login

Do patients on biologic drugs for rheumatic disease need PCP prophylaxis?

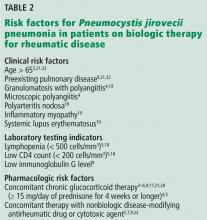

Pneumocystis jirovecii (previously carinii) pneumonia (PCP) is rare in patients taking biologic response modifiers for rheumatic disease.1–10 However, prophylaxis should be considered in patients who have granulomatosis with polyangiitis or underlying pulmonary disease, or who are concomitantly receiving glucocorticoids in high doses. There is some risk of adverse reactions to the prophylactic medicine.1,11–21 Until clear guidelines are available, the decision to initiate PCP prophylaxis and the choice of agent should be individualized.

THE BURDEN OF PCP

In a meta-analysis23 of 867 patients who developed PCP and did not have HIV infection, 20.1% had autoimmune or chronic inflammatory disease and the rest were transplant recipients or had malignancies. The mortality rate was 30.6%.

PHARMACOLOGIC RISK FACTORS FOR PCP

Treatment with glucocorticoids

Treatment with glucocorticoids is an important risk factor for PCP, independent of biologic therapy.

Calero-Bernal et al11 reported on 128 patients with non-HIV PCP, of whom 114 (89%) had received a glucocorticoid for more than 4 weeks, and 98 (76%) were currently receiving one. The mean daily dose was equivalent to 27.73 mg of prednisone per day in those on glucocorticoids only, and 21.34 mg in those receiving glucocorticoids in combination with other immunosuppressants.

Park et al,12 in a retrospective study of Korean patients treated for rheumatic disease with high-dose glucocorticoids (≥ 30 mg/day of prednisone or equivalent for more than 4 weeks), reported an incidence rate of PCP of 2.37 per 100 patient-years in those not on prophylaxis.

Other studies13,14 have also found a prednisone dose greater than 15 to 20 mg per day for more than 4 weeks or concomitant use of 2 or more disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs to be a significant risk factor.13,14

Tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonists

A US Food and Drug Administration review1 of voluntary reports of adverse drug events estimated the incidence of PCP to be 2.3 per 100,000 patient-years with infliximab and 1.6 per 100,000 patient-years with etanercept. In most cases, other immunosuppressants were used concomitantly.1

Postmarketing surveillance2 of 5,000 patients with rheumatoid arthritis showed an incidence of suspected PCP of 0.4% within the first 6 months of starting infliximab therapy.

Komano et al,15 in a case-control study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab, reported that all 21 patients with PCP were also on methotrexate (median dosage 8 mg per week) and prednisolone (median dosage 7.5 mg per day).

PCP has also been reported after adalimumab use in combination with prednisone, azathioprine, and methotrexate, as well as with certolizumab, golimumab, tocilizumab, abatacept, and rituximab.3–6,24–26

Rituximab

Calero-Bernal et al11 reported that 23% of patients with non-HIV PCP who were receiving immunosuppressant drugs were on rituximab.

Alexandre et al16 performed a retrospective review of 11 cases of PCP complicating rituximab therapy for autoimmune disease, in which 10 (91%) of the patients were also on corticosteroids, with a median dosage of 30 mg of prednisone daily. A literature review of an additional 18 cases revealed similar findings.

PATIENT RISK FACTORS FOR PCP

Pulmonary disease, age, other factors

Komano et al,15 in their study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab, found that 10 (48%) of 21 patients with PCP had preexisting pulmonary disease, compared with 11 (10.8%) of 102 patients without PCP (P < .001). Patients with PCP were older (mean age 64 vs 54, P < .001), were on higher median doses of prednisolone per day (7.5 vs 5 mg, P = .001), and had lower median serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels (944 vs 1,394 mg/dL, P < .001).15

Tadros et al13 performed a case-control study that also showed that patients with autoimmune disease who developed PCP had lower lymphocyte counts than controls on admission. Other risk factors included low CD4 counts and age older than 50.

Li et al17 found that patients with autoimmune or inflammatory disease with PCP were more likely to have low CD3, CD4, and CD8 cell counts, as well as albumin levels less than 28 g/L. They therefore suggested that lymphocyte subtyping may be a useful tool to guide PCP prophylaxis.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis have a significantly higher incidence of PCP than patients with other connective tissue diseases.

Ward and Donald18 reviewed 223 cases of PCP in patients with connective tissue disease. The highest frequency (89 cases per 10,000 hospitalizations per year) was in patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis, followed by 65 per 10,000 hospitalizations per year for patients with polyarteritis nodosa. The lowest frequency was in rheumatoid arthritis patients, at 2 per 10,000 hospitalizations per year. In decreasing order, diseases with significant associations with PCP were:

- Polyarteritis nodosa (odds ratio [OR] 10.20, 95% confidence interval [CI] 5.69–18.29)

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (OR 7.81, 95% CI 4.71–13.05)

- Inflammatory myopathy (OR 4.44, 95% CI 2.67–7.38)

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (OR 2.52, 95% CI 1.66–3.82).

Vallabhaneni and Chiller,26 in a meta-analysis including rheumatoid arthritis patients on biologics, did not find an increased risk of PCP (OR 1.77, 95% CI 0.42–7.47).

Park et al12 found that the highest incidences of PCP were in patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, and systemic sclerosis. For systemic sclerosis, the main reason for giving high-dose glucocorticoids was interstitial lung disease.

Other studies19,20,28 also found an association with coexisting pulmonary disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

CURRENT GUIDELINES

There are guidelines for primary and secondary prophylaxis of PCP in HIV-positive patients with CD4 counts less than 200/mm3 or a history of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining illness.27 Additionally, patients with a CD4 cell percentage less than 14% should be considered for prophylaxis.27

Unfortunately, there are no guidelines for prophylaxis in patients taking immunosuppressants for rheumatic disease.

The recommended regimen for PCP prophylaxis in HIV-infected patients is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 1 double-strength or 1 single-strength tablet daily. Alternative regimens include 1 double-strength tablet 3 times per week, dapsone, aerosolized pentamidine, and atovaquone.27

There are also guidelines for prophylaxis in kidney transplant recipients, as well as for patients with hematologic malignancies and solid-organ malignancies, particularly those on chemotherapeutic agents and the T-cell-depleting agent alemtuzumab.29–31

Italian clinical practice guidelines for the use of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in inflammatory bowel disease recommend consideration of PCP prophylaxis in patients who are also on other immunosuppressants, particularly high-dose glucocorticoids.32

Prophylaxis has been shown to increase life expectancy and quality-adjusted life-years and to reduce cost for patients on immunosuppressive therapy for granulomatosis with polyangiitis.21 The European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases recently produced consensus statements recommending PCP prophylaxis for patients on rituximab with other concomitant immunosuppressants such as the equivalent of prednisone 20 mg daily for more than 4 weeks.33 Prophylaxis was not recommended for other biologic therapies.34,35

THE RISKS OF PROPHYLAXIS

The risk of PCP should be weighed against the risk of prophylaxis in patients with rheumatic disease. Adverse reactions to sulfonamide antibiotics including disease flares have been reported in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.36,37 Other studies have found no increased risk of flares in patients taking trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for PCP prophylaxis.12,38 A retrospective analysis of patients with vasculitis found no increased risk of combining methotrexate and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.39

KEY POINTS

- PCP is an opportunistic infection with a high risk of death.

- PCP has been reported with biologics used as immunomodulators in rheumatic disease.

- PCP prophylaxis should be considered in patients at high risk of PCP, such as those who have granulomatosis with polyangiitis, underlying pulmonary disease or who are concomitantly taking glucocorticoids.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Safety update on TNF-alpha antagonists: infliximab and etanercept.https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20180127041103/https://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/01/briefing/3779b2_01_cber_safety_revision2.htm. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- Takeuchi T, Tatsuki Y, Nogami Y, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety profile of infliximab in 5000 Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2008; 67(2):189–194. doi:10.1136/ard.2007.072967

- Koike T, Harigai M, Ishiguro N, et al. Safety and effectiveness of adalimumab in Japanese rheumatoid arthritis patients: postmarketing surveillance report of the first 3,000 patients. Mod Rheumatol 2012; 22(4):498–508. doi:10.1007/s10165-011-0541-5

- Bykerk V, Cush J, Winthrop K, et al. Update on the safety profile of certolizumab pegol in rheumatoid arthritis: an integrated analysis from clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74(1):96–103. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203660

- Koike T, Harigai M, Inokuma S, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis in Japan: interim analysis of 3881 patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2011; 70(12):2148–2151. doi:10.1136/ard.2011.151092

- Harigai M, Ishiguro N, Inokuma S, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety and effectiveness of abatacept in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol 2016; 26(4):491–498. doi:10.3109/14397595.2015.1123211

- Koike T, Harigai M, Inokuma S, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety and effectiveness of etanercept in Japan. J Rheumatol 2009; 36(5):898–906. doi:10.3899/jrheum.080791

- Grubbs JA, Baddley JW. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients receiving tumor-necrosis-factor-inhibitor therapy: implications for chemoprophylaxis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2014; 16(10):445. doi:10.1007/s11926-014-0445-4

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS) public dashboard. www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Surveillance/AdverseDrugEffects/ucm070093.htm. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- Rutherford AI, Patarata E, Subesinghe S, Hyrich KL, Galloway JB. Opportunistic infections in rheumatoid arthritis patients exposed to biologic therapy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018; 57(6):997–1001. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/key023

- Calero-Bernal ML, Martin-Garrido I, Donazar-Ezcurra M, Limper AH, Carmona EM. Intermittent courses of corticosteroids also present a risk for Pneumocystis pneumonia in non-HIV patients. Can Respir J 2016; 2016:2464791. doi:10.1155/2016/2464791

- Park JW, Curtis JR, Moon J, Song YW, Kim S, Lee EB. Prophylactic effect of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with rheumatic diseases exposed to prolonged high-dose glucocorticoids. Ann Rheum Dis 2018; 77(5):644–649. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211796

- Tadros S, Teichtahl AJ, Ciciriello S, Wicks IP. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in systemic autoimmune rheumatic disease: a case-control study. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017; 46(6):804–809. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.09.009

- Demoruelle MK, Kahr A, Verilhac K, Deane K, Fischer A, West S. Recent-onset systemic lupus erythematosus complicated by acute respiratory failure. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013; 65(2):314–323. doi:10.1002/acr.21857

- Komano Y, Harigai M, Koike R, et al. Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab: a retrospective review and case-control study of 21 patients. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 61(3):305–312. doi:10.1002/art.24283

- Alexandre K, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Versini M, Sailler L, Benhamou Y. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients treated with rituximab for systemic diseases: report of 11 cases and review of the literature. Eur J Intern Med 2018; 50:e23–e24. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2017.11.014

- Li Y, Ghannoum M, Deng C, et al. Pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with inflammatory or autoimmune diseases: usefulness of lymphocyte subtyping. Int J Infect Dis 2017; 57:108–115. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2017.02.010

- Ward MM, Donald F. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with connective tissue diseases: the role of hospital experience in diagnosis and mortality. Arthritis Rheum 1999; 42(4):780–789. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(199904)42:4<780::AID-ANR23>3.0.CO;2-M

- Katsuyama T, Saito K, Kubo S, Nawata M, Tanaka Y. Prophylaxis for Pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologics, based on risk factors found in a retrospective study. Arthritis Res Ther 2014; 16(1):R43. doi:10.1186/ar4472

- Tanaka M, Sakai R, Koike R, et al. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia associated with etanercept treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective review of 15 cases and analysis of risk factors. Mod Rheumatol 2012; 22(6):849–858. doi:10.1007/s10165-012-0615-z

- Chung JB, Armstrong K, Schwartz JS, Albert D. Cost-effectiveness of prophylaxis against Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis undergoing immunosuppressive therapy. Arthritis Rheum 2000; 43(8):1841–1848. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(200008)43:8<1841::AID-ANR21>3.0.CO;2-Q

- Selmi C, Generali E, Massarotti M, Bianchi G, Scire CA. New treatments for inflammatory rheumatic disease. Immunol Res 2014; 60(2–3):277–288. doi:10.1007/s12026-014-8565-5

- Liu Y, Su L, Jiang SJ, Qu H. Risk factors for mortality from Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) in non-HIV patients: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017; 8(35):59729–59739. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.19927

- Desales AL, Mendez-Navarro J, Méndez-Tovar LJ, et al. Pneumocystosis in a patient with Crohn's disease treated with combination therapy with adalimumab. J Crohns Colitis 2012; 6(4):483–487. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2011.10.012

- Kalyoncu U, Karadag O, Akdogan A, et al. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in a rheumatoid arthritis patient treated with adalimumab. Scand J Infect Dis 2007; 39(5):475–478. doi:10.1080/00365540601071867

- Vallabhaneni S, Chiller TM. Fungal infections and new biologic therapies. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2016; 18(5):29. doi:10.1007/s11926-016-0572-1

- Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adult_oi.pdf. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- Kourbeti IS, Ziakas PD, Mylonakis E. Biologic therapies in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of opportunistic infections: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58(12):1649–1657. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu185

- Bia M, Adey DB, Bloom RD, Chan L, Kulkarni S, Tomlanovich S. KDOQI US commentary on the 2009 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am J Kidney Dis 2010; 56(2):189–218. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.04.010

- Baden LR, Swaminathan S, Angarone M, et al. Prevention and treatment of cancer-related infections, version 2.2016, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2016; 14(7):882–913. pmid:27407129

- Cooley L, Dendle C, Wolf J, et al. Consensus guidelines for diagnosis, prophylaxis and management of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with haematological and solid malignancies, 2014. Intern Med J 2014; 44(12b):1350–1363. doi:10.1111/imj.12599

- Orlando A, Armuzzi A, Papi C, et al; Italian Society of Gastroenterology; Italian Group for the study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. The Italian Society of Gastroenterology (SIGE) and the Italian Group for the study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IG-IBD) clinical practice guidelines: the use of tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonist therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis 2011; 43(1):1–20. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2010.07.010

- Mikulska M, Lanini S, Gudiol C, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) consensus document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (agents targeting lymphoid cells surface antigens [I]: CD19, CD20 and CD52). Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24(suppl 2):S71–S82. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2018.02.003

- Baddley J, Cantini F, Goletti D, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) consensus document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (soluble immune effector molecules [I]: anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha agents). Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24(suppl 2):S10–S20. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.12.025

- Winthrop K, Mariette X, Silva J, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) consensus document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (soluble immune effector molecules [II]: agents targeting interleukins, immunoglobulins and complement factors). Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24(suppl 2):S21–S40. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2018.02.002

- Petri M, Allbritton J. Antibiotic allergy in systemic lupus erythematosus: a case-control study. J Rheumatol 1992; 19(2):265–269. pmid:1629825

- Pope J, Jerome D, Fenlon D, Krizova A, Ouimet J. Frequency of adverse drug reactions in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2003; 30(3):480–484. pmid:12610805

- Vananuvat P, Suwannalai P, Sungkanuparph S, Limsuwan T, Ngamjanyaporn P, Janwityanujit S. Primary prophylaxis for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with connective tissue diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2011; 41(3):497–502. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.05.004

- Tamaki H, Butler R, Langford C. Abstract Number: 1755: Safety of methotrexate and low-dose trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis. www.acrabstracts.org/abstract/safety-of-methotrexate-and-low-dose-trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-in-patients-with-anca-associated-vasculitis. Accessed May 3, 2019.

Pneumocystis jirovecii (previously carinii) pneumonia (PCP) is rare in patients taking biologic response modifiers for rheumatic disease.1–10 However, prophylaxis should be considered in patients who have granulomatosis with polyangiitis or underlying pulmonary disease, or who are concomitantly receiving glucocorticoids in high doses. There is some risk of adverse reactions to the prophylactic medicine.1,11–21 Until clear guidelines are available, the decision to initiate PCP prophylaxis and the choice of agent should be individualized.

THE BURDEN OF PCP

In a meta-analysis23 of 867 patients who developed PCP and did not have HIV infection, 20.1% had autoimmune or chronic inflammatory disease and the rest were transplant recipients or had malignancies. The mortality rate was 30.6%.

PHARMACOLOGIC RISK FACTORS FOR PCP

Treatment with glucocorticoids

Treatment with glucocorticoids is an important risk factor for PCP, independent of biologic therapy.

Calero-Bernal et al11 reported on 128 patients with non-HIV PCP, of whom 114 (89%) had received a glucocorticoid for more than 4 weeks, and 98 (76%) were currently receiving one. The mean daily dose was equivalent to 27.73 mg of prednisone per day in those on glucocorticoids only, and 21.34 mg in those receiving glucocorticoids in combination with other immunosuppressants.

Park et al,12 in a retrospective study of Korean patients treated for rheumatic disease with high-dose glucocorticoids (≥ 30 mg/day of prednisone or equivalent for more than 4 weeks), reported an incidence rate of PCP of 2.37 per 100 patient-years in those not on prophylaxis.

Other studies13,14 have also found a prednisone dose greater than 15 to 20 mg per day for more than 4 weeks or concomitant use of 2 or more disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs to be a significant risk factor.13,14

Tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonists

A US Food and Drug Administration review1 of voluntary reports of adverse drug events estimated the incidence of PCP to be 2.3 per 100,000 patient-years with infliximab and 1.6 per 100,000 patient-years with etanercept. In most cases, other immunosuppressants were used concomitantly.1

Postmarketing surveillance2 of 5,000 patients with rheumatoid arthritis showed an incidence of suspected PCP of 0.4% within the first 6 months of starting infliximab therapy.

Komano et al,15 in a case-control study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab, reported that all 21 patients with PCP were also on methotrexate (median dosage 8 mg per week) and prednisolone (median dosage 7.5 mg per day).

PCP has also been reported after adalimumab use in combination with prednisone, azathioprine, and methotrexate, as well as with certolizumab, golimumab, tocilizumab, abatacept, and rituximab.3–6,24–26

Rituximab

Calero-Bernal et al11 reported that 23% of patients with non-HIV PCP who were receiving immunosuppressant drugs were on rituximab.

Alexandre et al16 performed a retrospective review of 11 cases of PCP complicating rituximab therapy for autoimmune disease, in which 10 (91%) of the patients were also on corticosteroids, with a median dosage of 30 mg of prednisone daily. A literature review of an additional 18 cases revealed similar findings.

PATIENT RISK FACTORS FOR PCP

Pulmonary disease, age, other factors

Komano et al,15 in their study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab, found that 10 (48%) of 21 patients with PCP had preexisting pulmonary disease, compared with 11 (10.8%) of 102 patients without PCP (P < .001). Patients with PCP were older (mean age 64 vs 54, P < .001), were on higher median doses of prednisolone per day (7.5 vs 5 mg, P = .001), and had lower median serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels (944 vs 1,394 mg/dL, P < .001).15

Tadros et al13 performed a case-control study that also showed that patients with autoimmune disease who developed PCP had lower lymphocyte counts than controls on admission. Other risk factors included low CD4 counts and age older than 50.

Li et al17 found that patients with autoimmune or inflammatory disease with PCP were more likely to have low CD3, CD4, and CD8 cell counts, as well as albumin levels less than 28 g/L. They therefore suggested that lymphocyte subtyping may be a useful tool to guide PCP prophylaxis.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis have a significantly higher incidence of PCP than patients with other connective tissue diseases.

Ward and Donald18 reviewed 223 cases of PCP in patients with connective tissue disease. The highest frequency (89 cases per 10,000 hospitalizations per year) was in patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis, followed by 65 per 10,000 hospitalizations per year for patients with polyarteritis nodosa. The lowest frequency was in rheumatoid arthritis patients, at 2 per 10,000 hospitalizations per year. In decreasing order, diseases with significant associations with PCP were:

- Polyarteritis nodosa (odds ratio [OR] 10.20, 95% confidence interval [CI] 5.69–18.29)

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (OR 7.81, 95% CI 4.71–13.05)

- Inflammatory myopathy (OR 4.44, 95% CI 2.67–7.38)

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (OR 2.52, 95% CI 1.66–3.82).

Vallabhaneni and Chiller,26 in a meta-analysis including rheumatoid arthritis patients on biologics, did not find an increased risk of PCP (OR 1.77, 95% CI 0.42–7.47).

Park et al12 found that the highest incidences of PCP were in patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, and systemic sclerosis. For systemic sclerosis, the main reason for giving high-dose glucocorticoids was interstitial lung disease.

Other studies19,20,28 also found an association with coexisting pulmonary disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

CURRENT GUIDELINES

There are guidelines for primary and secondary prophylaxis of PCP in HIV-positive patients with CD4 counts less than 200/mm3 or a history of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining illness.27 Additionally, patients with a CD4 cell percentage less than 14% should be considered for prophylaxis.27

Unfortunately, there are no guidelines for prophylaxis in patients taking immunosuppressants for rheumatic disease.

The recommended regimen for PCP prophylaxis in HIV-infected patients is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 1 double-strength or 1 single-strength tablet daily. Alternative regimens include 1 double-strength tablet 3 times per week, dapsone, aerosolized pentamidine, and atovaquone.27

There are also guidelines for prophylaxis in kidney transplant recipients, as well as for patients with hematologic malignancies and solid-organ malignancies, particularly those on chemotherapeutic agents and the T-cell-depleting agent alemtuzumab.29–31

Italian clinical practice guidelines for the use of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in inflammatory bowel disease recommend consideration of PCP prophylaxis in patients who are also on other immunosuppressants, particularly high-dose glucocorticoids.32

Prophylaxis has been shown to increase life expectancy and quality-adjusted life-years and to reduce cost for patients on immunosuppressive therapy for granulomatosis with polyangiitis.21 The European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases recently produced consensus statements recommending PCP prophylaxis for patients on rituximab with other concomitant immunosuppressants such as the equivalent of prednisone 20 mg daily for more than 4 weeks.33 Prophylaxis was not recommended for other biologic therapies.34,35

THE RISKS OF PROPHYLAXIS

The risk of PCP should be weighed against the risk of prophylaxis in patients with rheumatic disease. Adverse reactions to sulfonamide antibiotics including disease flares have been reported in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.36,37 Other studies have found no increased risk of flares in patients taking trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for PCP prophylaxis.12,38 A retrospective analysis of patients with vasculitis found no increased risk of combining methotrexate and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.39

KEY POINTS

- PCP is an opportunistic infection with a high risk of death.

- PCP has been reported with biologics used as immunomodulators in rheumatic disease.

- PCP prophylaxis should be considered in patients at high risk of PCP, such as those who have granulomatosis with polyangiitis, underlying pulmonary disease or who are concomitantly taking glucocorticoids.

Pneumocystis jirovecii (previously carinii) pneumonia (PCP) is rare in patients taking biologic response modifiers for rheumatic disease.1–10 However, prophylaxis should be considered in patients who have granulomatosis with polyangiitis or underlying pulmonary disease, or who are concomitantly receiving glucocorticoids in high doses. There is some risk of adverse reactions to the prophylactic medicine.1,11–21 Until clear guidelines are available, the decision to initiate PCP prophylaxis and the choice of agent should be individualized.

THE BURDEN OF PCP

In a meta-analysis23 of 867 patients who developed PCP and did not have HIV infection, 20.1% had autoimmune or chronic inflammatory disease and the rest were transplant recipients or had malignancies. The mortality rate was 30.6%.

PHARMACOLOGIC RISK FACTORS FOR PCP

Treatment with glucocorticoids

Treatment with glucocorticoids is an important risk factor for PCP, independent of biologic therapy.

Calero-Bernal et al11 reported on 128 patients with non-HIV PCP, of whom 114 (89%) had received a glucocorticoid for more than 4 weeks, and 98 (76%) were currently receiving one. The mean daily dose was equivalent to 27.73 mg of prednisone per day in those on glucocorticoids only, and 21.34 mg in those receiving glucocorticoids in combination with other immunosuppressants.

Park et al,12 in a retrospective study of Korean patients treated for rheumatic disease with high-dose glucocorticoids (≥ 30 mg/day of prednisone or equivalent for more than 4 weeks), reported an incidence rate of PCP of 2.37 per 100 patient-years in those not on prophylaxis.

Other studies13,14 have also found a prednisone dose greater than 15 to 20 mg per day for more than 4 weeks or concomitant use of 2 or more disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs to be a significant risk factor.13,14

Tumor necrosis factor alpha antagonists

A US Food and Drug Administration review1 of voluntary reports of adverse drug events estimated the incidence of PCP to be 2.3 per 100,000 patient-years with infliximab and 1.6 per 100,000 patient-years with etanercept. In most cases, other immunosuppressants were used concomitantly.1

Postmarketing surveillance2 of 5,000 patients with rheumatoid arthritis showed an incidence of suspected PCP of 0.4% within the first 6 months of starting infliximab therapy.

Komano et al,15 in a case-control study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab, reported that all 21 patients with PCP were also on methotrexate (median dosage 8 mg per week) and prednisolone (median dosage 7.5 mg per day).

PCP has also been reported after adalimumab use in combination with prednisone, azathioprine, and methotrexate, as well as with certolizumab, golimumab, tocilizumab, abatacept, and rituximab.3–6,24–26

Rituximab

Calero-Bernal et al11 reported that 23% of patients with non-HIV PCP who were receiving immunosuppressant drugs were on rituximab.

Alexandre et al16 performed a retrospective review of 11 cases of PCP complicating rituximab therapy for autoimmune disease, in which 10 (91%) of the patients were also on corticosteroids, with a median dosage of 30 mg of prednisone daily. A literature review of an additional 18 cases revealed similar findings.

PATIENT RISK FACTORS FOR PCP

Pulmonary disease, age, other factors

Komano et al,15 in their study of patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab, found that 10 (48%) of 21 patients with PCP had preexisting pulmonary disease, compared with 11 (10.8%) of 102 patients without PCP (P < .001). Patients with PCP were older (mean age 64 vs 54, P < .001), were on higher median doses of prednisolone per day (7.5 vs 5 mg, P = .001), and had lower median serum immunoglobulin G (IgG) levels (944 vs 1,394 mg/dL, P < .001).15

Tadros et al13 performed a case-control study that also showed that patients with autoimmune disease who developed PCP had lower lymphocyte counts than controls on admission. Other risk factors included low CD4 counts and age older than 50.

Li et al17 found that patients with autoimmune or inflammatory disease with PCP were more likely to have low CD3, CD4, and CD8 cell counts, as well as albumin levels less than 28 g/L. They therefore suggested that lymphocyte subtyping may be a useful tool to guide PCP prophylaxis.

Granulomatosis with polyangiitis

Patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis have a significantly higher incidence of PCP than patients with other connective tissue diseases.

Ward and Donald18 reviewed 223 cases of PCP in patients with connective tissue disease. The highest frequency (89 cases per 10,000 hospitalizations per year) was in patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis, followed by 65 per 10,000 hospitalizations per year for patients with polyarteritis nodosa. The lowest frequency was in rheumatoid arthritis patients, at 2 per 10,000 hospitalizations per year. In decreasing order, diseases with significant associations with PCP were:

- Polyarteritis nodosa (odds ratio [OR] 10.20, 95% confidence interval [CI] 5.69–18.29)

- Granulomatosis with polyangiitis (OR 7.81, 95% CI 4.71–13.05)

- Inflammatory myopathy (OR 4.44, 95% CI 2.67–7.38)

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (OR 2.52, 95% CI 1.66–3.82).

Vallabhaneni and Chiller,26 in a meta-analysis including rheumatoid arthritis patients on biologics, did not find an increased risk of PCP (OR 1.77, 95% CI 0.42–7.47).

Park et al12 found that the highest incidences of PCP were in patients with granulomatosis with polyangiitis, microscopic polyangiitis, and systemic sclerosis. For systemic sclerosis, the main reason for giving high-dose glucocorticoids was interstitial lung disease.

Other studies19,20,28 also found an association with coexisting pulmonary disease in patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

CURRENT GUIDELINES

There are guidelines for primary and secondary prophylaxis of PCP in HIV-positive patients with CD4 counts less than 200/mm3 or a history of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-defining illness.27 Additionally, patients with a CD4 cell percentage less than 14% should be considered for prophylaxis.27

Unfortunately, there are no guidelines for prophylaxis in patients taking immunosuppressants for rheumatic disease.

The recommended regimen for PCP prophylaxis in HIV-infected patients is trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, 1 double-strength or 1 single-strength tablet daily. Alternative regimens include 1 double-strength tablet 3 times per week, dapsone, aerosolized pentamidine, and atovaquone.27

There are also guidelines for prophylaxis in kidney transplant recipients, as well as for patients with hematologic malignancies and solid-organ malignancies, particularly those on chemotherapeutic agents and the T-cell-depleting agent alemtuzumab.29–31

Italian clinical practice guidelines for the use of tumor necrosis factor antagonists in inflammatory bowel disease recommend consideration of PCP prophylaxis in patients who are also on other immunosuppressants, particularly high-dose glucocorticoids.32

Prophylaxis has been shown to increase life expectancy and quality-adjusted life-years and to reduce cost for patients on immunosuppressive therapy for granulomatosis with polyangiitis.21 The European Society of Clinical Microbiology and Infectious Diseases recently produced consensus statements recommending PCP prophylaxis for patients on rituximab with other concomitant immunosuppressants such as the equivalent of prednisone 20 mg daily for more than 4 weeks.33 Prophylaxis was not recommended for other biologic therapies.34,35

THE RISKS OF PROPHYLAXIS

The risk of PCP should be weighed against the risk of prophylaxis in patients with rheumatic disease. Adverse reactions to sulfonamide antibiotics including disease flares have been reported in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus.36,37 Other studies have found no increased risk of flares in patients taking trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for PCP prophylaxis.12,38 A retrospective analysis of patients with vasculitis found no increased risk of combining methotrexate and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole.39

KEY POINTS

- PCP is an opportunistic infection with a high risk of death.

- PCP has been reported with biologics used as immunomodulators in rheumatic disease.

- PCP prophylaxis should be considered in patients at high risk of PCP, such as those who have granulomatosis with polyangiitis, underlying pulmonary disease or who are concomitantly taking glucocorticoids.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Safety update on TNF-alpha antagonists: infliximab and etanercept.https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20180127041103/https://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/01/briefing/3779b2_01_cber_safety_revision2.htm. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- Takeuchi T, Tatsuki Y, Nogami Y, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety profile of infliximab in 5000 Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2008; 67(2):189–194. doi:10.1136/ard.2007.072967

- Koike T, Harigai M, Ishiguro N, et al. Safety and effectiveness of adalimumab in Japanese rheumatoid arthritis patients: postmarketing surveillance report of the first 3,000 patients. Mod Rheumatol 2012; 22(4):498–508. doi:10.1007/s10165-011-0541-5

- Bykerk V, Cush J, Winthrop K, et al. Update on the safety profile of certolizumab pegol in rheumatoid arthritis: an integrated analysis from clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74(1):96–103. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203660

- Koike T, Harigai M, Inokuma S, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis in Japan: interim analysis of 3881 patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2011; 70(12):2148–2151. doi:10.1136/ard.2011.151092

- Harigai M, Ishiguro N, Inokuma S, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety and effectiveness of abatacept in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol 2016; 26(4):491–498. doi:10.3109/14397595.2015.1123211

- Koike T, Harigai M, Inokuma S, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety and effectiveness of etanercept in Japan. J Rheumatol 2009; 36(5):898–906. doi:10.3899/jrheum.080791

- Grubbs JA, Baddley JW. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients receiving tumor-necrosis-factor-inhibitor therapy: implications for chemoprophylaxis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2014; 16(10):445. doi:10.1007/s11926-014-0445-4

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS) public dashboard. www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Surveillance/AdverseDrugEffects/ucm070093.htm. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- Rutherford AI, Patarata E, Subesinghe S, Hyrich KL, Galloway JB. Opportunistic infections in rheumatoid arthritis patients exposed to biologic therapy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018; 57(6):997–1001. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/key023

- Calero-Bernal ML, Martin-Garrido I, Donazar-Ezcurra M, Limper AH, Carmona EM. Intermittent courses of corticosteroids also present a risk for Pneumocystis pneumonia in non-HIV patients. Can Respir J 2016; 2016:2464791. doi:10.1155/2016/2464791

- Park JW, Curtis JR, Moon J, Song YW, Kim S, Lee EB. Prophylactic effect of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with rheumatic diseases exposed to prolonged high-dose glucocorticoids. Ann Rheum Dis 2018; 77(5):644–649. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211796

- Tadros S, Teichtahl AJ, Ciciriello S, Wicks IP. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in systemic autoimmune rheumatic disease: a case-control study. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017; 46(6):804–809. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.09.009

- Demoruelle MK, Kahr A, Verilhac K, Deane K, Fischer A, West S. Recent-onset systemic lupus erythematosus complicated by acute respiratory failure. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013; 65(2):314–323. doi:10.1002/acr.21857

- Komano Y, Harigai M, Koike R, et al. Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab: a retrospective review and case-control study of 21 patients. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 61(3):305–312. doi:10.1002/art.24283

- Alexandre K, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Versini M, Sailler L, Benhamou Y. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients treated with rituximab for systemic diseases: report of 11 cases and review of the literature. Eur J Intern Med 2018; 50:e23–e24. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2017.11.014

- Li Y, Ghannoum M, Deng C, et al. Pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with inflammatory or autoimmune diseases: usefulness of lymphocyte subtyping. Int J Infect Dis 2017; 57:108–115. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2017.02.010

- Ward MM, Donald F. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with connective tissue diseases: the role of hospital experience in diagnosis and mortality. Arthritis Rheum 1999; 42(4):780–789. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(199904)42:4<780::AID-ANR23>3.0.CO;2-M

- Katsuyama T, Saito K, Kubo S, Nawata M, Tanaka Y. Prophylaxis for Pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologics, based on risk factors found in a retrospective study. Arthritis Res Ther 2014; 16(1):R43. doi:10.1186/ar4472

- Tanaka M, Sakai R, Koike R, et al. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia associated with etanercept treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective review of 15 cases and analysis of risk factors. Mod Rheumatol 2012; 22(6):849–858. doi:10.1007/s10165-012-0615-z

- Chung JB, Armstrong K, Schwartz JS, Albert D. Cost-effectiveness of prophylaxis against Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis undergoing immunosuppressive therapy. Arthritis Rheum 2000; 43(8):1841–1848. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(200008)43:8<1841::AID-ANR21>3.0.CO;2-Q

- Selmi C, Generali E, Massarotti M, Bianchi G, Scire CA. New treatments for inflammatory rheumatic disease. Immunol Res 2014; 60(2–3):277–288. doi:10.1007/s12026-014-8565-5

- Liu Y, Su L, Jiang SJ, Qu H. Risk factors for mortality from Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) in non-HIV patients: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017; 8(35):59729–59739. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.19927

- Desales AL, Mendez-Navarro J, Méndez-Tovar LJ, et al. Pneumocystosis in a patient with Crohn's disease treated with combination therapy with adalimumab. J Crohns Colitis 2012; 6(4):483–487. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2011.10.012

- Kalyoncu U, Karadag O, Akdogan A, et al. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in a rheumatoid arthritis patient treated with adalimumab. Scand J Infect Dis 2007; 39(5):475–478. doi:10.1080/00365540601071867

- Vallabhaneni S, Chiller TM. Fungal infections and new biologic therapies. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2016; 18(5):29. doi:10.1007/s11926-016-0572-1

- Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adult_oi.pdf. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- Kourbeti IS, Ziakas PD, Mylonakis E. Biologic therapies in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of opportunistic infections: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58(12):1649–1657. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu185

- Bia M, Adey DB, Bloom RD, Chan L, Kulkarni S, Tomlanovich S. KDOQI US commentary on the 2009 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am J Kidney Dis 2010; 56(2):189–218. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.04.010

- Baden LR, Swaminathan S, Angarone M, et al. Prevention and treatment of cancer-related infections, version 2.2016, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2016; 14(7):882–913. pmid:27407129

- Cooley L, Dendle C, Wolf J, et al. Consensus guidelines for diagnosis, prophylaxis and management of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with haematological and solid malignancies, 2014. Intern Med J 2014; 44(12b):1350–1363. doi:10.1111/imj.12599

- Orlando A, Armuzzi A, Papi C, et al; Italian Society of Gastroenterology; Italian Group for the study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. The Italian Society of Gastroenterology (SIGE) and the Italian Group for the study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IG-IBD) clinical practice guidelines: the use of tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonist therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis 2011; 43(1):1–20. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2010.07.010

- Mikulska M, Lanini S, Gudiol C, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) consensus document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (agents targeting lymphoid cells surface antigens [I]: CD19, CD20 and CD52). Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24(suppl 2):S71–S82. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2018.02.003

- Baddley J, Cantini F, Goletti D, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) consensus document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (soluble immune effector molecules [I]: anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha agents). Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24(suppl 2):S10–S20. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.12.025

- Winthrop K, Mariette X, Silva J, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) consensus document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (soluble immune effector molecules [II]: agents targeting interleukins, immunoglobulins and complement factors). Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24(suppl 2):S21–S40. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2018.02.002

- Petri M, Allbritton J. Antibiotic allergy in systemic lupus erythematosus: a case-control study. J Rheumatol 1992; 19(2):265–269. pmid:1629825

- Pope J, Jerome D, Fenlon D, Krizova A, Ouimet J. Frequency of adverse drug reactions in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2003; 30(3):480–484. pmid:12610805

- Vananuvat P, Suwannalai P, Sungkanuparph S, Limsuwan T, Ngamjanyaporn P, Janwityanujit S. Primary prophylaxis for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with connective tissue diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2011; 41(3):497–502. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.05.004

- Tamaki H, Butler R, Langford C. Abstract Number: 1755: Safety of methotrexate and low-dose trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis. www.acrabstracts.org/abstract/safety-of-methotrexate-and-low-dose-trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-in-patients-with-anca-associated-vasculitis. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- US Food and Drug Administration. Safety update on TNF-alpha antagonists: infliximab and etanercept.https://wayback.archive-it.org/7993/20180127041103/https://www.fda.gov/ohrms/dockets/ac/01/briefing/3779b2_01_cber_safety_revision2.htm. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- Takeuchi T, Tatsuki Y, Nogami Y, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety profile of infliximab in 5000 Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis 2008; 67(2):189–194. doi:10.1136/ard.2007.072967

- Koike T, Harigai M, Ishiguro N, et al. Safety and effectiveness of adalimumab in Japanese rheumatoid arthritis patients: postmarketing surveillance report of the first 3,000 patients. Mod Rheumatol 2012; 22(4):498–508. doi:10.1007/s10165-011-0541-5

- Bykerk V, Cush J, Winthrop K, et al. Update on the safety profile of certolizumab pegol in rheumatoid arthritis: an integrated analysis from clinical trials. Ann Rheum Dis 2015; 74(1):96–103. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2013-203660

- Koike T, Harigai M, Inokuma S, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of tocilizumab for rheumatoid arthritis in Japan: interim analysis of 3881 patients. Ann Rheum Dis 2011; 70(12):2148–2151. doi:10.1136/ard.2011.151092

- Harigai M, Ishiguro N, Inokuma S, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety and effectiveness of abatacept in Japanese patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Mod Rheumatol 2016; 26(4):491–498. doi:10.3109/14397595.2015.1123211

- Koike T, Harigai M, Inokuma S, et al. Postmarketing surveillance of the safety and effectiveness of etanercept in Japan. J Rheumatol 2009; 36(5):898–906. doi:10.3899/jrheum.080791

- Grubbs JA, Baddley JW. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients receiving tumor-necrosis-factor-inhibitor therapy: implications for chemoprophylaxis. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2014; 16(10):445. doi:10.1007/s11926-014-0445-4

- US Food and Drug Administration. FDA adverse event reporting system (FAERS) public dashboard. www.fda.gov/Drugs/GuidanceComplianceRegulatoryInformation/Surveillance/AdverseDrugEffects/ucm070093.htm. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- Rutherford AI, Patarata E, Subesinghe S, Hyrich KL, Galloway JB. Opportunistic infections in rheumatoid arthritis patients exposed to biologic therapy: results from the British Society for Rheumatology Biologics Register for Rheumatoid Arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2018; 57(6):997–1001. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/key023

- Calero-Bernal ML, Martin-Garrido I, Donazar-Ezcurra M, Limper AH, Carmona EM. Intermittent courses of corticosteroids also present a risk for Pneumocystis pneumonia in non-HIV patients. Can Respir J 2016; 2016:2464791. doi:10.1155/2016/2464791

- Park JW, Curtis JR, Moon J, Song YW, Kim S, Lee EB. Prophylactic effect of trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole for pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with rheumatic diseases exposed to prolonged high-dose glucocorticoids. Ann Rheum Dis 2018; 77(5):644–649. doi:10.1136/annrheumdis-2017-211796

- Tadros S, Teichtahl AJ, Ciciriello S, Wicks IP. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in systemic autoimmune rheumatic disease: a case-control study. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2017; 46(6):804–809. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.09.009

- Demoruelle MK, Kahr A, Verilhac K, Deane K, Fischer A, West S. Recent-onset systemic lupus erythematosus complicated by acute respiratory failure. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2013; 65(2):314–323. doi:10.1002/acr.21857

- Komano Y, Harigai M, Koike R, et al. Pneumocystis jiroveci pneumonia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with infliximab: a retrospective review and case-control study of 21 patients. Arthritis Rheum 2009; 61(3):305–312. doi:10.1002/art.24283

- Alexandre K, Ingen-Housz-Oro S, Versini M, Sailler L, Benhamou Y. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients treated with rituximab for systemic diseases: report of 11 cases and review of the literature. Eur J Intern Med 2018; 50:e23–e24. doi:10.1016/j.ejim.2017.11.014

- Li Y, Ghannoum M, Deng C, et al. Pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with inflammatory or autoimmune diseases: usefulness of lymphocyte subtyping. Int J Infect Dis 2017; 57:108–115. doi:10.1016/j.ijid.2017.02.010

- Ward MM, Donald F. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with connective tissue diseases: the role of hospital experience in diagnosis and mortality. Arthritis Rheum 1999; 42(4):780–789. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(199904)42:4<780::AID-ANR23>3.0.CO;2-M

- Katsuyama T, Saito K, Kubo S, Nawata M, Tanaka Y. Prophylaxis for Pneumocystis pneumonia in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with biologics, based on risk factors found in a retrospective study. Arthritis Res Ther 2014; 16(1):R43. doi:10.1186/ar4472

- Tanaka M, Sakai R, Koike R, et al. Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia associated with etanercept treatment in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective review of 15 cases and analysis of risk factors. Mod Rheumatol 2012; 22(6):849–858. doi:10.1007/s10165-012-0615-z

- Chung JB, Armstrong K, Schwartz JS, Albert D. Cost-effectiveness of prophylaxis against Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in patients with Wegener’s granulomatosis undergoing immunosuppressive therapy. Arthritis Rheum 2000; 43(8):1841–1848. doi:10.1002/1529-0131(200008)43:8<1841::AID-ANR21>3.0.CO;2-Q

- Selmi C, Generali E, Massarotti M, Bianchi G, Scire CA. New treatments for inflammatory rheumatic disease. Immunol Res 2014; 60(2–3):277–288. doi:10.1007/s12026-014-8565-5

- Liu Y, Su L, Jiang SJ, Qu H. Risk factors for mortality from Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) in non-HIV patients: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget 2017; 8(35):59729–59739. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.19927

- Desales AL, Mendez-Navarro J, Méndez-Tovar LJ, et al. Pneumocystosis in a patient with Crohn's disease treated with combination therapy with adalimumab. J Crohns Colitis 2012; 6(4):483–487. doi:10.1016/j.crohns.2011.10.012

- Kalyoncu U, Karadag O, Akdogan A, et al. Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia in a rheumatoid arthritis patient treated with adalimumab. Scand J Infect Dis 2007; 39(5):475–478. doi:10.1080/00365540601071867

- Vallabhaneni S, Chiller TM. Fungal infections and new biologic therapies. Curr Rheumatol Rep 2016; 18(5):29. doi:10.1007/s11926-016-0572-1

- Panel on Opportunistic Infections in HIV-Infected Adults and Adolescents. Guidelines for the prevention and treatment of opportunistic infections in HIV-infected adults and adolescents: recommendations from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the National Institutes of Health, and the HIV Medicine Association of the Infectious Diseases Society of America. www.aidsinfo.nih.gov/contentfiles/lvguidelines/adult_oi.pdf. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- Kourbeti IS, Ziakas PD, Mylonakis E. Biologic therapies in rheumatoid arthritis and the risk of opportunistic infections: a meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 58(12):1649–1657. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu185

- Bia M, Adey DB, Bloom RD, Chan L, Kulkarni S, Tomlanovich S. KDOQI US commentary on the 2009 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the care of kidney transplant recipients. Am J Kidney Dis 2010; 56(2):189–218. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.04.010

- Baden LR, Swaminathan S, Angarone M, et al. Prevention and treatment of cancer-related infections, version 2.2016, NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw 2016; 14(7):882–913. pmid:27407129

- Cooley L, Dendle C, Wolf J, et al. Consensus guidelines for diagnosis, prophylaxis and management of Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with haematological and solid malignancies, 2014. Intern Med J 2014; 44(12b):1350–1363. doi:10.1111/imj.12599

- Orlando A, Armuzzi A, Papi C, et al; Italian Society of Gastroenterology; Italian Group for the study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. The Italian Society of Gastroenterology (SIGE) and the Italian Group for the study of Inflammatory Bowel Disease (IG-IBD) clinical practice guidelines: the use of tumor necrosis factor-alpha antagonist therapy in inflammatory bowel disease. Dig Liver Dis 2011; 43(1):1–20. doi:10.1016/j.dld.2010.07.010

- Mikulska M, Lanini S, Gudiol C, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) consensus document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (agents targeting lymphoid cells surface antigens [I]: CD19, CD20 and CD52). Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24(suppl 2):S71–S82. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2018.02.003

- Baddley J, Cantini F, Goletti D, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) consensus document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (soluble immune effector molecules [I]: anti-tumor necrosis factor-alpha agents). Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24(suppl 2):S10–S20. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2017.12.025

- Winthrop K, Mariette X, Silva J, et al. ESCMID Study Group for Infections in Compromised Hosts (ESGICH) consensus document on the safety of targeted and biological therapies: an infectious diseases perspective (soluble immune effector molecules [II]: agents targeting interleukins, immunoglobulins and complement factors). Clin Microbiol Infect 2018; 24(suppl 2):S21–S40. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2018.02.002

- Petri M, Allbritton J. Antibiotic allergy in systemic lupus erythematosus: a case-control study. J Rheumatol 1992; 19(2):265–269. pmid:1629825

- Pope J, Jerome D, Fenlon D, Krizova A, Ouimet J. Frequency of adverse drug reactions in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. J Rheumatol 2003; 30(3):480–484. pmid:12610805

- Vananuvat P, Suwannalai P, Sungkanuparph S, Limsuwan T, Ngamjanyaporn P, Janwityanujit S. Primary prophylaxis for Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia in patients with connective tissue diseases. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2011; 41(3):497–502. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2011.05.004

- Tamaki H, Butler R, Langford C. Abstract Number: 1755: Safety of methotrexate and low-dose trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole in patients with ANCA-associated vasculitis. www.acrabstracts.org/abstract/safety-of-methotrexate-and-low-dose-trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole-in-patients-with-anca-associated-vasculitis. Accessed May 3, 2019.