User login

The Use of Clinical Decision Support in Reducing Diagnosis of and Treatment of Asymptomatic Bacteriuria

Reducing the treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB), or isolation of bacteria from a urine specimen in a patient without urinary tract infection (UTI) symptoms, is a key goal of antibiotic stewardship programs.1 Treatment of ASB has been associated with the emergence of resistant organisms and subsequent UTI risk among women with recurrent UTI.2,3 The Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign recommend against treating ASB, with the exception of pregnant patients and urogenital surgical patients.1,4

Obtaining urinalyses and urine cultures (UC) in asymptomatic patients may contribute to the unnecessary treatment of ASB. In a study of hospitalized patients, 62% received urinalysis testing, even though 82% of these patients did not have UTI symptoms.5 Of the patients found to have ASB, 30% were given antibiotics.5 Therefore, interventions aimed at reducing urine testing may reduce ASB treatment.

Electronic passive clinical decision support (CDS) alerts and electronic education may be effective interventions to reduce urine testing.6 While CDS tools are recommended in antibiotic stewardship guidelines,7 they have led to only modest improvements in appropriate antibiotic prescribing and are typically bundled with time-intensive educational interventions.8 Furthermore, most in-hospital interventions to decrease ASB treatment have focused on intensive care units (ICUs).9 We hypothesized that CDS and electronic education would decrease (1) urinalysis and UC ordering and (2) antibiotic orders for urinalyses and UCs in hospitalized adult patients.

METHODS

Population

We conducted a prospective time series analysis (preintervention: September 2014 to June 2015; postintervention: September 2015 to June 2016) at a large tertiary medical center. All hospitalized patients ≥18 years old were eligible except those admitted to services requiring specialized ASB management (eg, leukemia and lymphoma, solid organ transplant, and obstetrics).1 The study was declared quality improvement by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board.

Intervention

In August 2015, we implemented a multifaceted intervention that included provider education and passive electronic CDS (supplementary Appendix 1 and supplementary Appendix 2). Materials were disseminated through hospital-wide computer workstation screensavers and a 1-page e-mailed newsletter to department of medicine clinicians. The CDS tool included simple informational messages recommending against urine testing without symptoms and against treating ASB; these messages accompanied electronic health record (EHR; Allscripts Sunrise Clinical Manager, Chicago, IL) orders for urinalysis, UC, and antibiotics commonly used within our institution to treat UTI (cefazolin, cephalexin, ceftriaxone, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, nitrofurantoin, and ciprofloxacin). The information was displayed automatically when orders for these tests and antibiotics were selected; provider acknowledgment was not required to proceed.

Data Collection

The services within our hospital are geographically located. We collected orders for urinalysis, UC, and the associated antibiotics for all units except those housing patients excluded from our study. As the CDS tool appeared only in the inpatient EHR, only postadmission orders were included, excluding emergency department orders. For admissions with multiple urinalyses, urinalysis orders placed ≥72 hours apart were eligible. Only antibiotics ordered for ≥24 hours were included, excluding on-call and 1-time antibiotic orders.

Our approach to data collection attempted to model a clinician’s decision-making pathway from (1) ordering a urinalysis, to (2) ordering a UC in response to a urinalysis result, to (3) ordering antibiotics in response to a urinalysis or UC result. We focused on order placement rather than results to prioritize avoiding testing in asymptomatic patients, as our institution does not require positive urinalyses for UC testing (reflex testing). Urinalyses resulted within 1 to 2 hours, allowing for clinicians to quickly order UCs after urinalysis result review. Urinalysis and UC orders per monthly admissions were defined as (1) urinalyses, (2) UCs, (3) simultaneous urinalysis and UC (within 1 hour of each other), and (4) UCs ordered 1 to 24 hours after urinalysis. We also analyzed the following antibiotic orders per monthly admissions: (1) simultaneous urinalysis and antibiotic orders, (2) antibiotics ordered 1 to 24 hours after urinalysis order, and (3) antibiotics ordered within 24 hours of the UC result.

Outcome Measures

All outcome measures were calculated as the change over time per total monthly admissions in the preintervention and postintervention periods. In addition to symptoms, urinalysis is a critical, measurable early step in determining the presence of ASB. Therefore, the primary outcome measure was the postintervention change in monthly urinalysis orders, and the secondary outcome measure was the postintervention change in monthly UC orders. Additional outcome measures included monthly postintervention changes in (1) UC ordered 1 to 24 hours after urinalyses, (2) urinalyses and antibiotics ordered simultaneously, (3) antibiotic orders within 1 to 24 hours of urinalyses, and (4) antibiotics ordered within 24 hours of UC result.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by using Stata (version 14.2; StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). An interrupted time series analysis was performed to compare the change in orders per 100 monthly admissions in preintervention and postintervention periods. To do this, we created 2 separate segmented linear regression models for each dependent variable, pre- and postintervention. Normality was assumed because of large numbers. Rate differences per 100 monthly admissions are also calculated as the total number of orders divided by the total number of admissions in postintervention and preintervention periods with Mantel-Haenszel estimators. Differences were considered statistically significant at P ≤ .05.

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

A multifaceted but simple bundle of CDS and provider education reduced UC testing but not urinalyses in a large tertiary care hospital. The bundle also reduced antibiotic ordering in response to urinalyses as well as antibiotic ordering in response to UC results.

Other in-hospital CDS tools to decrease ASB treatment have focused only on ICUs.9,10 Our intervention was evaluated hospital-wide and included urinalyses and UCs. Our intervention was clinician directed and not laboratory directed, such as a positive urinalysis reflexing to a UC. Simultaneous urinalysis and UC testing may lead to ASB treatment, as clinicians treat the positive UC and ignore the negative urinalysis.11,12 Therefore, we focused on UCs being sent in response to urinalyses.

We chose to focus on laboratory testing data instead of administrative diagnoses for UTI. The sensitivity of administrative data to determine similar conditions such as catheter-associated UTIs is low (0%).13

Our single-center study may not be generalizable to other settings. We did not include emergency department patients, as this location used a different EHR. In addition, given the 600,000 yearly hospital admissions, it was impractical to assess the appropriateness of each antibiotic-based documentation of symptoms. Instead of focusing on symptoms of ASB or UTI diagnoses, we focused on ordering urinalysis, UC, and antibiotics. In investigating the antibiotics most frequently used to treat UTI in our hospital, we may have both missed some patients who were treated with other antibiotics for ASB (eg, 4th generation cephalosporins, penicillins, carbapenems, etc) and captured patients receiving antibiotics for indications other than UTI (eg, pneumonia). In our focus on overall ordering practices across a hospital, we did not capture data on bladder catheterization status or the predominant organism seen in UC. At the time of the intervention, the laboratory did not have the resources for urinalysis testing reflexing to UC. However, our intervention did not prevent ordering simultaneous urinalysis and UC in symptomatic patients in general or urosepsis in particular. With only 12 total time points, the interrupted time series analysis may have been underpowered.14 We also do not know if the intervention’s effect would decay over time.

Although the intervention took very little staff time and resources, alert fatigue was a risk.15 We attempted to mitigate this alert fatigue by making the CDS passive (in the form of a brief informational message) with no provider action required. In conversations with providers in our institution, there has been dissatisfaction with alerts requiring action, as these are thought to be overly intrusive. We are also not clear on which element of the intervention bundle (ie, the CDS or the educational intervention) may have had more of an impact, as the elements of the intervention bundle were rolled out simultaneously. It is possible and even probable that both elements are needed to raise awareness of the problem. Also, as our EHR required all interventions to be rolled out hospital-wide simultaneously, we were unable to randomize certain floors or providers to the CDS portion of the intervention bundle. Other analyses including the type of hospital unit were beyond the scope of this brief report.

Our intervention bundle was associated with reduced UC orders and reduced antibiotics ordered after urinalyses. If a provider does not know there is bacteriuria, then the provider will not be tempted to order antibiotics. This easily implementable bundle may play an important role as an antimicrobial stewardship strategy for ASB.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of Erin Fanning, BS, and Angel Florentin, BS, in providing data for analysis. SCK received funding from the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR), which is funded in part by grant number KL2TR001077 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. These contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the Johns Hopkins ICTR, NCATS, or NIH. We also acknowledge support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Prevention Epicenter Program Q8377 (collaborative agreement U54 CK000447 to SEC). SEC has received support for consulting from Novartis and Theravance, and her institution has received a grant from Pfizer Grants for Learning and Change/The Joint Commission. This work was supported by the NIH T32 HL116275 to NC. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Disclosure

No conflicts of interest have been reported by any author.

1. Nicolle LE, Bradley S, Colgan R, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(5):643-654. PubMed

2. Cai T, Mazzoli S, Mondaini N, et al. The role of asymptomatic bacteriuria in young women with recurrent urinary tract infections: to treat or not to treat? Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(6):771-777. PubMed

3. Cai T, Nesi G, Mazzoli S, et al. Asymptomatic bacteriuria treatment is associated with a higher prevalence of antibiotic resistant strains in women with urinary tract infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(11):1655-1661. PubMed

4. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Choosing Wisely: Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question. 2015. http://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/infectious-diseases-society-of-america/. Accessed on September 11, 2016.

5. Yin P, Kiss A, Leis JA. Urinalysis Orders Among Patients Admitted to the General Medicine Service. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(10):1711-1713. PubMed

6. McGregor JC, Weekes E, Forrest GN, et al. Impact of a computerized clinical decision support system on reducing inappropriate antimicrobial use: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13(4):378-384. PubMed

7. Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, et al. Implementing an Antibiotic Stewardship Program: Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(10):e51-e77. PubMed

8. Gonzales R, Anderer T, McCulloch CE, et al. A cluster randomized trial of decision support strategies for reducing antibiotic use in acute bronchitis. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(4):267-273. PubMed

9. Sarg M, Waldrop GE, Beier MA, et al. Impact of Changes in Urine Culture Ordering Practice on Antimicrobial Utilization in Intensive Care Units at an Academic Medical Center. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(4):448-454. PubMed

10. Mehrotra A, Linder JA. Tipping the Balance Toward Fewer Antibiotics. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1649-1650. PubMed

11. Leis JA, Gold WL, Daneman N, Shojania K, McGeer A. Downstream impact of urine cultures ordered without indication at two acute care teaching hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(10):1113-1114. PubMed

12. Stagg A, Lutz H, Kirpalaney S, et al. Impact of two-step urine culture ordering in the emergency department: a time series analysis. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006250. PubMed

13. Cass AL, Kelly JW, Probst JC, Addy CL, McKeown RE. Identification of device-associated infections utilizing administrative data. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(12):1195-1199. PubMed

14. Zhang F, Wagner AK, Ross-Degnan D. Simulation-based power calculation for designing interrupted time series analyses of health policy interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(11):1252-1261. PubMed

15. Embi PJ, Leonard AC. Evaluating alert fatigue over time to EHR-based clinical trial alerts: findings from a randomized controlled study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(e1):e145-e148. PubMed

Reducing the treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB), or isolation of bacteria from a urine specimen in a patient without urinary tract infection (UTI) symptoms, is a key goal of antibiotic stewardship programs.1 Treatment of ASB has been associated with the emergence of resistant organisms and subsequent UTI risk among women with recurrent UTI.2,3 The Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign recommend against treating ASB, with the exception of pregnant patients and urogenital surgical patients.1,4

Obtaining urinalyses and urine cultures (UC) in asymptomatic patients may contribute to the unnecessary treatment of ASB. In a study of hospitalized patients, 62% received urinalysis testing, even though 82% of these patients did not have UTI symptoms.5 Of the patients found to have ASB, 30% were given antibiotics.5 Therefore, interventions aimed at reducing urine testing may reduce ASB treatment.

Electronic passive clinical decision support (CDS) alerts and electronic education may be effective interventions to reduce urine testing.6 While CDS tools are recommended in antibiotic stewardship guidelines,7 they have led to only modest improvements in appropriate antibiotic prescribing and are typically bundled with time-intensive educational interventions.8 Furthermore, most in-hospital interventions to decrease ASB treatment have focused on intensive care units (ICUs).9 We hypothesized that CDS and electronic education would decrease (1) urinalysis and UC ordering and (2) antibiotic orders for urinalyses and UCs in hospitalized adult patients.

METHODS

Population

We conducted a prospective time series analysis (preintervention: September 2014 to June 2015; postintervention: September 2015 to June 2016) at a large tertiary medical center. All hospitalized patients ≥18 years old were eligible except those admitted to services requiring specialized ASB management (eg, leukemia and lymphoma, solid organ transplant, and obstetrics).1 The study was declared quality improvement by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board.

Intervention

In August 2015, we implemented a multifaceted intervention that included provider education and passive electronic CDS (supplementary Appendix 1 and supplementary Appendix 2). Materials were disseminated through hospital-wide computer workstation screensavers and a 1-page e-mailed newsletter to department of medicine clinicians. The CDS tool included simple informational messages recommending against urine testing without symptoms and against treating ASB; these messages accompanied electronic health record (EHR; Allscripts Sunrise Clinical Manager, Chicago, IL) orders for urinalysis, UC, and antibiotics commonly used within our institution to treat UTI (cefazolin, cephalexin, ceftriaxone, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, nitrofurantoin, and ciprofloxacin). The information was displayed automatically when orders for these tests and antibiotics were selected; provider acknowledgment was not required to proceed.

Data Collection

The services within our hospital are geographically located. We collected orders for urinalysis, UC, and the associated antibiotics for all units except those housing patients excluded from our study. As the CDS tool appeared only in the inpatient EHR, only postadmission orders were included, excluding emergency department orders. For admissions with multiple urinalyses, urinalysis orders placed ≥72 hours apart were eligible. Only antibiotics ordered for ≥24 hours were included, excluding on-call and 1-time antibiotic orders.

Our approach to data collection attempted to model a clinician’s decision-making pathway from (1) ordering a urinalysis, to (2) ordering a UC in response to a urinalysis result, to (3) ordering antibiotics in response to a urinalysis or UC result. We focused on order placement rather than results to prioritize avoiding testing in asymptomatic patients, as our institution does not require positive urinalyses for UC testing (reflex testing). Urinalyses resulted within 1 to 2 hours, allowing for clinicians to quickly order UCs after urinalysis result review. Urinalysis and UC orders per monthly admissions were defined as (1) urinalyses, (2) UCs, (3) simultaneous urinalysis and UC (within 1 hour of each other), and (4) UCs ordered 1 to 24 hours after urinalysis. We also analyzed the following antibiotic orders per monthly admissions: (1) simultaneous urinalysis and antibiotic orders, (2) antibiotics ordered 1 to 24 hours after urinalysis order, and (3) antibiotics ordered within 24 hours of the UC result.

Outcome Measures

All outcome measures were calculated as the change over time per total monthly admissions in the preintervention and postintervention periods. In addition to symptoms, urinalysis is a critical, measurable early step in determining the presence of ASB. Therefore, the primary outcome measure was the postintervention change in monthly urinalysis orders, and the secondary outcome measure was the postintervention change in monthly UC orders. Additional outcome measures included monthly postintervention changes in (1) UC ordered 1 to 24 hours after urinalyses, (2) urinalyses and antibiotics ordered simultaneously, (3) antibiotic orders within 1 to 24 hours of urinalyses, and (4) antibiotics ordered within 24 hours of UC result.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by using Stata (version 14.2; StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). An interrupted time series analysis was performed to compare the change in orders per 100 monthly admissions in preintervention and postintervention periods. To do this, we created 2 separate segmented linear regression models for each dependent variable, pre- and postintervention. Normality was assumed because of large numbers. Rate differences per 100 monthly admissions are also calculated as the total number of orders divided by the total number of admissions in postintervention and preintervention periods with Mantel-Haenszel estimators. Differences were considered statistically significant at P ≤ .05.

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

A multifaceted but simple bundle of CDS and provider education reduced UC testing but not urinalyses in a large tertiary care hospital. The bundle also reduced antibiotic ordering in response to urinalyses as well as antibiotic ordering in response to UC results.

Other in-hospital CDS tools to decrease ASB treatment have focused only on ICUs.9,10 Our intervention was evaluated hospital-wide and included urinalyses and UCs. Our intervention was clinician directed and not laboratory directed, such as a positive urinalysis reflexing to a UC. Simultaneous urinalysis and UC testing may lead to ASB treatment, as clinicians treat the positive UC and ignore the negative urinalysis.11,12 Therefore, we focused on UCs being sent in response to urinalyses.

We chose to focus on laboratory testing data instead of administrative diagnoses for UTI. The sensitivity of administrative data to determine similar conditions such as catheter-associated UTIs is low (0%).13

Our single-center study may not be generalizable to other settings. We did not include emergency department patients, as this location used a different EHR. In addition, given the 600,000 yearly hospital admissions, it was impractical to assess the appropriateness of each antibiotic-based documentation of symptoms. Instead of focusing on symptoms of ASB or UTI diagnoses, we focused on ordering urinalysis, UC, and antibiotics. In investigating the antibiotics most frequently used to treat UTI in our hospital, we may have both missed some patients who were treated with other antibiotics for ASB (eg, 4th generation cephalosporins, penicillins, carbapenems, etc) and captured patients receiving antibiotics for indications other than UTI (eg, pneumonia). In our focus on overall ordering practices across a hospital, we did not capture data on bladder catheterization status or the predominant organism seen in UC. At the time of the intervention, the laboratory did not have the resources for urinalysis testing reflexing to UC. However, our intervention did not prevent ordering simultaneous urinalysis and UC in symptomatic patients in general or urosepsis in particular. With only 12 total time points, the interrupted time series analysis may have been underpowered.14 We also do not know if the intervention’s effect would decay over time.

Although the intervention took very little staff time and resources, alert fatigue was a risk.15 We attempted to mitigate this alert fatigue by making the CDS passive (in the form of a brief informational message) with no provider action required. In conversations with providers in our institution, there has been dissatisfaction with alerts requiring action, as these are thought to be overly intrusive. We are also not clear on which element of the intervention bundle (ie, the CDS or the educational intervention) may have had more of an impact, as the elements of the intervention bundle were rolled out simultaneously. It is possible and even probable that both elements are needed to raise awareness of the problem. Also, as our EHR required all interventions to be rolled out hospital-wide simultaneously, we were unable to randomize certain floors or providers to the CDS portion of the intervention bundle. Other analyses including the type of hospital unit were beyond the scope of this brief report.

Our intervention bundle was associated with reduced UC orders and reduced antibiotics ordered after urinalyses. If a provider does not know there is bacteriuria, then the provider will not be tempted to order antibiotics. This easily implementable bundle may play an important role as an antimicrobial stewardship strategy for ASB.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of Erin Fanning, BS, and Angel Florentin, BS, in providing data for analysis. SCK received funding from the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR), which is funded in part by grant number KL2TR001077 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. These contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the Johns Hopkins ICTR, NCATS, or NIH. We also acknowledge support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Prevention Epicenter Program Q8377 (collaborative agreement U54 CK000447 to SEC). SEC has received support for consulting from Novartis and Theravance, and her institution has received a grant from Pfizer Grants for Learning and Change/The Joint Commission. This work was supported by the NIH T32 HL116275 to NC. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Disclosure

No conflicts of interest have been reported by any author.

Reducing the treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria (ASB), or isolation of bacteria from a urine specimen in a patient without urinary tract infection (UTI) symptoms, is a key goal of antibiotic stewardship programs.1 Treatment of ASB has been associated with the emergence of resistant organisms and subsequent UTI risk among women with recurrent UTI.2,3 The Infectious Diseases Society of America and the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation’s Choosing Wisely campaign recommend against treating ASB, with the exception of pregnant patients and urogenital surgical patients.1,4

Obtaining urinalyses and urine cultures (UC) in asymptomatic patients may contribute to the unnecessary treatment of ASB. In a study of hospitalized patients, 62% received urinalysis testing, even though 82% of these patients did not have UTI symptoms.5 Of the patients found to have ASB, 30% were given antibiotics.5 Therefore, interventions aimed at reducing urine testing may reduce ASB treatment.

Electronic passive clinical decision support (CDS) alerts and electronic education may be effective interventions to reduce urine testing.6 While CDS tools are recommended in antibiotic stewardship guidelines,7 they have led to only modest improvements in appropriate antibiotic prescribing and are typically bundled with time-intensive educational interventions.8 Furthermore, most in-hospital interventions to decrease ASB treatment have focused on intensive care units (ICUs).9 We hypothesized that CDS and electronic education would decrease (1) urinalysis and UC ordering and (2) antibiotic orders for urinalyses and UCs in hospitalized adult patients.

METHODS

Population

We conducted a prospective time series analysis (preintervention: September 2014 to June 2015; postintervention: September 2015 to June 2016) at a large tertiary medical center. All hospitalized patients ≥18 years old were eligible except those admitted to services requiring specialized ASB management (eg, leukemia and lymphoma, solid organ transplant, and obstetrics).1 The study was declared quality improvement by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board.

Intervention

In August 2015, we implemented a multifaceted intervention that included provider education and passive electronic CDS (supplementary Appendix 1 and supplementary Appendix 2). Materials were disseminated through hospital-wide computer workstation screensavers and a 1-page e-mailed newsletter to department of medicine clinicians. The CDS tool included simple informational messages recommending against urine testing without symptoms and against treating ASB; these messages accompanied electronic health record (EHR; Allscripts Sunrise Clinical Manager, Chicago, IL) orders for urinalysis, UC, and antibiotics commonly used within our institution to treat UTI (cefazolin, cephalexin, ceftriaxone, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, nitrofurantoin, and ciprofloxacin). The information was displayed automatically when orders for these tests and antibiotics were selected; provider acknowledgment was not required to proceed.

Data Collection

The services within our hospital are geographically located. We collected orders for urinalysis, UC, and the associated antibiotics for all units except those housing patients excluded from our study. As the CDS tool appeared only in the inpatient EHR, only postadmission orders were included, excluding emergency department orders. For admissions with multiple urinalyses, urinalysis orders placed ≥72 hours apart were eligible. Only antibiotics ordered for ≥24 hours were included, excluding on-call and 1-time antibiotic orders.

Our approach to data collection attempted to model a clinician’s decision-making pathway from (1) ordering a urinalysis, to (2) ordering a UC in response to a urinalysis result, to (3) ordering antibiotics in response to a urinalysis or UC result. We focused on order placement rather than results to prioritize avoiding testing in asymptomatic patients, as our institution does not require positive urinalyses for UC testing (reflex testing). Urinalyses resulted within 1 to 2 hours, allowing for clinicians to quickly order UCs after urinalysis result review. Urinalysis and UC orders per monthly admissions were defined as (1) urinalyses, (2) UCs, (3) simultaneous urinalysis and UC (within 1 hour of each other), and (4) UCs ordered 1 to 24 hours after urinalysis. We also analyzed the following antibiotic orders per monthly admissions: (1) simultaneous urinalysis and antibiotic orders, (2) antibiotics ordered 1 to 24 hours after urinalysis order, and (3) antibiotics ordered within 24 hours of the UC result.

Outcome Measures

All outcome measures were calculated as the change over time per total monthly admissions in the preintervention and postintervention periods. In addition to symptoms, urinalysis is a critical, measurable early step in determining the presence of ASB. Therefore, the primary outcome measure was the postintervention change in monthly urinalysis orders, and the secondary outcome measure was the postintervention change in monthly UC orders. Additional outcome measures included monthly postintervention changes in (1) UC ordered 1 to 24 hours after urinalyses, (2) urinalyses and antibiotics ordered simultaneously, (3) antibiotic orders within 1 to 24 hours of urinalyses, and (4) antibiotics ordered within 24 hours of UC result.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed by using Stata (version 14.2; StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). An interrupted time series analysis was performed to compare the change in orders per 100 monthly admissions in preintervention and postintervention periods. To do this, we created 2 separate segmented linear regression models for each dependent variable, pre- and postintervention. Normality was assumed because of large numbers. Rate differences per 100 monthly admissions are also calculated as the total number of orders divided by the total number of admissions in postintervention and preintervention periods with Mantel-Haenszel estimators. Differences were considered statistically significant at P ≤ .05.

RESULTS

DISCUSSION

A multifaceted but simple bundle of CDS and provider education reduced UC testing but not urinalyses in a large tertiary care hospital. The bundle also reduced antibiotic ordering in response to urinalyses as well as antibiotic ordering in response to UC results.

Other in-hospital CDS tools to decrease ASB treatment have focused only on ICUs.9,10 Our intervention was evaluated hospital-wide and included urinalyses and UCs. Our intervention was clinician directed and not laboratory directed, such as a positive urinalysis reflexing to a UC. Simultaneous urinalysis and UC testing may lead to ASB treatment, as clinicians treat the positive UC and ignore the negative urinalysis.11,12 Therefore, we focused on UCs being sent in response to urinalyses.

We chose to focus on laboratory testing data instead of administrative diagnoses for UTI. The sensitivity of administrative data to determine similar conditions such as catheter-associated UTIs is low (0%).13

Our single-center study may not be generalizable to other settings. We did not include emergency department patients, as this location used a different EHR. In addition, given the 600,000 yearly hospital admissions, it was impractical to assess the appropriateness of each antibiotic-based documentation of symptoms. Instead of focusing on symptoms of ASB or UTI diagnoses, we focused on ordering urinalysis, UC, and antibiotics. In investigating the antibiotics most frequently used to treat UTI in our hospital, we may have both missed some patients who were treated with other antibiotics for ASB (eg, 4th generation cephalosporins, penicillins, carbapenems, etc) and captured patients receiving antibiotics for indications other than UTI (eg, pneumonia). In our focus on overall ordering practices across a hospital, we did not capture data on bladder catheterization status or the predominant organism seen in UC. At the time of the intervention, the laboratory did not have the resources for urinalysis testing reflexing to UC. However, our intervention did not prevent ordering simultaneous urinalysis and UC in symptomatic patients in general or urosepsis in particular. With only 12 total time points, the interrupted time series analysis may have been underpowered.14 We also do not know if the intervention’s effect would decay over time.

Although the intervention took very little staff time and resources, alert fatigue was a risk.15 We attempted to mitigate this alert fatigue by making the CDS passive (in the form of a brief informational message) with no provider action required. In conversations with providers in our institution, there has been dissatisfaction with alerts requiring action, as these are thought to be overly intrusive. We are also not clear on which element of the intervention bundle (ie, the CDS or the educational intervention) may have had more of an impact, as the elements of the intervention bundle were rolled out simultaneously. It is possible and even probable that both elements are needed to raise awareness of the problem. Also, as our EHR required all interventions to be rolled out hospital-wide simultaneously, we were unable to randomize certain floors or providers to the CDS portion of the intervention bundle. Other analyses including the type of hospital unit were beyond the scope of this brief report.

Our intervention bundle was associated with reduced UC orders and reduced antibiotics ordered after urinalyses. If a provider does not know there is bacteriuria, then the provider will not be tempted to order antibiotics. This easily implementable bundle may play an important role as an antimicrobial stewardship strategy for ASB.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the support of Erin Fanning, BS, and Angel Florentin, BS, in providing data for analysis. SCK received funding from the Johns Hopkins Institute for Clinical and Translational Research (ICTR), which is funded in part by grant number KL2TR001077 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and the NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. These contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of the Johns Hopkins ICTR, NCATS, or NIH. We also acknowledge support from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Prevention Epicenter Program Q8377 (collaborative agreement U54 CK000447 to SEC). SEC has received support for consulting from Novartis and Theravance, and her institution has received a grant from Pfizer Grants for Learning and Change/The Joint Commission. This work was supported by the NIH T32 HL116275 to NC. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Disclosure

No conflicts of interest have been reported by any author.

1. Nicolle LE, Bradley S, Colgan R, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(5):643-654. PubMed

2. Cai T, Mazzoli S, Mondaini N, et al. The role of asymptomatic bacteriuria in young women with recurrent urinary tract infections: to treat or not to treat? Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(6):771-777. PubMed

3. Cai T, Nesi G, Mazzoli S, et al. Asymptomatic bacteriuria treatment is associated with a higher prevalence of antibiotic resistant strains in women with urinary tract infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(11):1655-1661. PubMed

4. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Choosing Wisely: Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question. 2015. http://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/infectious-diseases-society-of-america/. Accessed on September 11, 2016.

5. Yin P, Kiss A, Leis JA. Urinalysis Orders Among Patients Admitted to the General Medicine Service. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(10):1711-1713. PubMed

6. McGregor JC, Weekes E, Forrest GN, et al. Impact of a computerized clinical decision support system on reducing inappropriate antimicrobial use: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13(4):378-384. PubMed

7. Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, et al. Implementing an Antibiotic Stewardship Program: Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(10):e51-e77. PubMed

8. Gonzales R, Anderer T, McCulloch CE, et al. A cluster randomized trial of decision support strategies for reducing antibiotic use in acute bronchitis. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(4):267-273. PubMed

9. Sarg M, Waldrop GE, Beier MA, et al. Impact of Changes in Urine Culture Ordering Practice on Antimicrobial Utilization in Intensive Care Units at an Academic Medical Center. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(4):448-454. PubMed

10. Mehrotra A, Linder JA. Tipping the Balance Toward Fewer Antibiotics. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1649-1650. PubMed

11. Leis JA, Gold WL, Daneman N, Shojania K, McGeer A. Downstream impact of urine cultures ordered without indication at two acute care teaching hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(10):1113-1114. PubMed

12. Stagg A, Lutz H, Kirpalaney S, et al. Impact of two-step urine culture ordering in the emergency department: a time series analysis. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006250. PubMed

13. Cass AL, Kelly JW, Probst JC, Addy CL, McKeown RE. Identification of device-associated infections utilizing administrative data. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(12):1195-1199. PubMed

14. Zhang F, Wagner AK, Ross-Degnan D. Simulation-based power calculation for designing interrupted time series analyses of health policy interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(11):1252-1261. PubMed

15. Embi PJ, Leonard AC. Evaluating alert fatigue over time to EHR-based clinical trial alerts: findings from a randomized controlled study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(e1):e145-e148. PubMed

1. Nicolle LE, Bradley S, Colgan R, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of asymptomatic bacteriuria in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2005;40(5):643-654. PubMed

2. Cai T, Mazzoli S, Mondaini N, et al. The role of asymptomatic bacteriuria in young women with recurrent urinary tract infections: to treat or not to treat? Clin Infect Dis. 2012;55(6):771-777. PubMed

3. Cai T, Nesi G, Mazzoli S, et al. Asymptomatic bacteriuria treatment is associated with a higher prevalence of antibiotic resistant strains in women with urinary tract infections. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;61(11):1655-1661. PubMed

4. Infectious Diseases Society of America. Choosing Wisely: Five Things Physicians and Patients Should Question. 2015. http://www.choosingwisely.org/societies/infectious-diseases-society-of-america/. Accessed on September 11, 2016.

5. Yin P, Kiss A, Leis JA. Urinalysis Orders Among Patients Admitted to the General Medicine Service. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(10):1711-1713. PubMed

6. McGregor JC, Weekes E, Forrest GN, et al. Impact of a computerized clinical decision support system on reducing inappropriate antimicrobial use: a randomized controlled trial. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2006;13(4):378-384. PubMed

7. Barlam TF, Cosgrove SE, Abbo LM, et al. Implementing an Antibiotic Stewardship Program: Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America and the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62(10):e51-e77. PubMed

8. Gonzales R, Anderer T, McCulloch CE, et al. A cluster randomized trial of decision support strategies for reducing antibiotic use in acute bronchitis. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(4):267-273. PubMed

9. Sarg M, Waldrop GE, Beier MA, et al. Impact of Changes in Urine Culture Ordering Practice on Antimicrobial Utilization in Intensive Care Units at an Academic Medical Center. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2016;37(4):448-454. PubMed

10. Mehrotra A, Linder JA. Tipping the Balance Toward Fewer Antibiotics. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(11):1649-1650. PubMed

11. Leis JA, Gold WL, Daneman N, Shojania K, McGeer A. Downstream impact of urine cultures ordered without indication at two acute care teaching hospitals. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(10):1113-1114. PubMed

12. Stagg A, Lutz H, Kirpalaney S, et al. Impact of two-step urine culture ordering in the emergency department: a time series analysis. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017. doi:10.1136/bmjqs-2016-006250. PubMed

13. Cass AL, Kelly JW, Probst JC, Addy CL, McKeown RE. Identification of device-associated infections utilizing administrative data. Am J Infect Control. 2013;41(12):1195-1199. PubMed

14. Zhang F, Wagner AK, Ross-Degnan D. Simulation-based power calculation for designing interrupted time series analyses of health policy interventions. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64(11):1252-1261. PubMed

15. Embi PJ, Leonard AC. Evaluating alert fatigue over time to EHR-based clinical trial alerts: findings from a randomized controlled study. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2012;19(e1):e145-e148. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

Primary Care Provider Preferences for Communication with Inpatient Teams: One Size Does Not Fit All

As the hospitalist’s role in medicine grows, the transition of care from inpatient to primary care providers (PCPs, including primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, or physician assistants), becomes increasingly important. Inadequate communication at this transition is associated with preventable adverse events leading to rehospitalization, disability, and death.1-

Providing PCPs access to the inpatient electronic health record (EHR) may reduce the need for active communication. However, a recent survey of PCPs in the general internal medicine division of an academic hospital found a strong preference for additional communication with inpatient providers, despite a shared EHR.5

We examined communication preferences of general internal medicine PCPs at a different academic institution and extended our study to include community-based PCPs who were both affiliated and unaffiliated with the institution.

METHODS

Between October 2015 and June 2016, we surveyed PCPs from 3 practice groups with institutional affiliation or proximity to The Johns Hopkins Hospital: all general internal medicine faculty with outpatient practices (“academic,” 2 practice sites, n = 35), all community-based PCPs affiliated with the health system (“community,” 36 practice sites, n = 220), and all PCPs from an unaffiliated managed care organization (“unaffiliated,” 5 practice sites ranging from 0.3 to 4 miles from The Johns Hopkins Hospital, n = 29).

All groups have work-sponsored e-mail services. At the time of the survey, both the academic and community groups used an EHR that allowed access to inpatient laboratory and radiology data and discharge summaries. The unaffiliated group used paper health records. The hospital faxes discharge summaries to all PCPs who are identified by patients.

The investigators and representatives from each practice group collaborated to develop 15 questions with mutually exclusive answers to evaluate PCP experiences with and preferences for communication with inpatient teams. The survey was constructed and administered through Qualtrics’ online platform (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) and distributed via e-mail. The study was reviewed and acknowledged by the Johns Hopkins institutional review board as quality improvement activity.

The survey contained branching logic. Only respondents who indicated preference for communication received questions regarding preferred mode of communication. We used the preferred mode of communication for initial contact from the inpatient team in our analysis. χ2 and Fischer’s exact tests were performed with JMP 12 software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Fourteen (40%) academic, 43 (14%) community, and 16 (55%) unaffiliated PCPs completed the survey, for 73 total responses from 284 surveys distributed (26%).

Among the 73 responding PCPs, 31 (42%) reported receiving notification of admission during “every” or “almost every” hospitalization, with no significant variation across practice groups (P = 0.5).

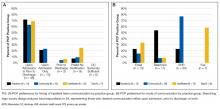

Across all groups, 64 PCPs (88%) preferred communication at 1 or more points during hospitalizations (panel A of Figure). “Both upon admission and prior to discharge” was selected most frequently, and there were no differences between practice groups (P = 0.2).

Preferred mode of communication, however, differed significantly between groups (panel B of Figure). The academic group had a greater preference for telephone (54%) than the community (8%; P < 0.001) and unaffiliated groups (8%; P < 0.001), the community group a greater preference for EHR (77%) than the academic (23%; P = 0.002) and unaffiliated groups (0%; P < 0.001), and the unaffiliated group a greater preference for fax (58%) than the other groups (both 0%; P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Our findings add to previous evidence of low rates of communication between inpatient providers and PCPs6 and a preference from PCPs for communication during hospitalizations despite shared EHRs.5 We extend previous work by demonstrating that PCP preferences for mode of communication vary by practice setting. Our findings lead us to hypothesize that identifying and incorporating PCP preferences may improve communication, though at the potential expense of standardization and efficiency.

There may be several reasons for the differing communication preferences observed. Most academic PCPs are located near or have admitting privileges to the hospital and are not in clinic full time. Their preference for the telephone may thus result from interpersonal relationships born from proximity and greater availability for telephone calls, or reduced fluency with the EHR compared to full-time community clinicians.

The unaffiliated group’s preference for fax may reflect a desire for communication that integrates easily with paper charts and is least disruptive to workflow, or concerns about health information confidentiality in e-mails.

Our study’s generalizability is limited by a low response rate, though it is comparable to prior studies.7 The unaffiliated group was accessed by convenience (acquaintance with the medical director); however, we note it had the highest response rate (55%).

In summary, we found low rates of communication between inpatient providers and PCPs, despite a strong preference from most PCPs for such communication during hospitalizations. PCPs’ preferred mode of communication differed based on practice setting. Addressing PCP communication preferences may be important to future care transition interventions.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

1. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-174. PubMed

2. Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, McGinn T. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(8):646-651. PubMed

3. van Walraven C, Mamdani M, Fang J, Austin PC. Continuity of care and patient outcomes after hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(6):624-631. PubMed

4. Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of Care Consensus policy statement: American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College Of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency M. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(6):364-370. PubMed

5. Sheu L, Fung K, Mourad M, Ranji S, Wu E. We need to talk: Primary care provider communication at discharge in the era of a shared electronic medical record. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(5):307-310. PubMed

6. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831-841. PubMed

7. Pantilat SZ, Lindenauer PK, Katz PP, Wachter RM. Primary care physician attitudes regarding communication with hospitalists. Am J Med. 2001(9B);111:15-20. PubMed

As the hospitalist’s role in medicine grows, the transition of care from inpatient to primary care providers (PCPs, including primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, or physician assistants), becomes increasingly important. Inadequate communication at this transition is associated with preventable adverse events leading to rehospitalization, disability, and death.1-

Providing PCPs access to the inpatient electronic health record (EHR) may reduce the need for active communication. However, a recent survey of PCPs in the general internal medicine division of an academic hospital found a strong preference for additional communication with inpatient providers, despite a shared EHR.5

We examined communication preferences of general internal medicine PCPs at a different academic institution and extended our study to include community-based PCPs who were both affiliated and unaffiliated with the institution.

METHODS

Between October 2015 and June 2016, we surveyed PCPs from 3 practice groups with institutional affiliation or proximity to The Johns Hopkins Hospital: all general internal medicine faculty with outpatient practices (“academic,” 2 practice sites, n = 35), all community-based PCPs affiliated with the health system (“community,” 36 practice sites, n = 220), and all PCPs from an unaffiliated managed care organization (“unaffiliated,” 5 practice sites ranging from 0.3 to 4 miles from The Johns Hopkins Hospital, n = 29).

All groups have work-sponsored e-mail services. At the time of the survey, both the academic and community groups used an EHR that allowed access to inpatient laboratory and radiology data and discharge summaries. The unaffiliated group used paper health records. The hospital faxes discharge summaries to all PCPs who are identified by patients.

The investigators and representatives from each practice group collaborated to develop 15 questions with mutually exclusive answers to evaluate PCP experiences with and preferences for communication with inpatient teams. The survey was constructed and administered through Qualtrics’ online platform (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) and distributed via e-mail. The study was reviewed and acknowledged by the Johns Hopkins institutional review board as quality improvement activity.

The survey contained branching logic. Only respondents who indicated preference for communication received questions regarding preferred mode of communication. We used the preferred mode of communication for initial contact from the inpatient team in our analysis. χ2 and Fischer’s exact tests were performed with JMP 12 software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Fourteen (40%) academic, 43 (14%) community, and 16 (55%) unaffiliated PCPs completed the survey, for 73 total responses from 284 surveys distributed (26%).

Among the 73 responding PCPs, 31 (42%) reported receiving notification of admission during “every” or “almost every” hospitalization, with no significant variation across practice groups (P = 0.5).

Across all groups, 64 PCPs (88%) preferred communication at 1 or more points during hospitalizations (panel A of Figure). “Both upon admission and prior to discharge” was selected most frequently, and there were no differences between practice groups (P = 0.2).

Preferred mode of communication, however, differed significantly between groups (panel B of Figure). The academic group had a greater preference for telephone (54%) than the community (8%; P < 0.001) and unaffiliated groups (8%; P < 0.001), the community group a greater preference for EHR (77%) than the academic (23%; P = 0.002) and unaffiliated groups (0%; P < 0.001), and the unaffiliated group a greater preference for fax (58%) than the other groups (both 0%; P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Our findings add to previous evidence of low rates of communication between inpatient providers and PCPs6 and a preference from PCPs for communication during hospitalizations despite shared EHRs.5 We extend previous work by demonstrating that PCP preferences for mode of communication vary by practice setting. Our findings lead us to hypothesize that identifying and incorporating PCP preferences may improve communication, though at the potential expense of standardization and efficiency.

There may be several reasons for the differing communication preferences observed. Most academic PCPs are located near or have admitting privileges to the hospital and are not in clinic full time. Their preference for the telephone may thus result from interpersonal relationships born from proximity and greater availability for telephone calls, or reduced fluency with the EHR compared to full-time community clinicians.

The unaffiliated group’s preference for fax may reflect a desire for communication that integrates easily with paper charts and is least disruptive to workflow, or concerns about health information confidentiality in e-mails.

Our study’s generalizability is limited by a low response rate, though it is comparable to prior studies.7 The unaffiliated group was accessed by convenience (acquaintance with the medical director); however, we note it had the highest response rate (55%).

In summary, we found low rates of communication between inpatient providers and PCPs, despite a strong preference from most PCPs for such communication during hospitalizations. PCPs’ preferred mode of communication differed based on practice setting. Addressing PCP communication preferences may be important to future care transition interventions.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

As the hospitalist’s role in medicine grows, the transition of care from inpatient to primary care providers (PCPs, including primary care physicians, nurse practitioners, or physician assistants), becomes increasingly important. Inadequate communication at this transition is associated with preventable adverse events leading to rehospitalization, disability, and death.1-

Providing PCPs access to the inpatient electronic health record (EHR) may reduce the need for active communication. However, a recent survey of PCPs in the general internal medicine division of an academic hospital found a strong preference for additional communication with inpatient providers, despite a shared EHR.5

We examined communication preferences of general internal medicine PCPs at a different academic institution and extended our study to include community-based PCPs who were both affiliated and unaffiliated with the institution.

METHODS

Between October 2015 and June 2016, we surveyed PCPs from 3 practice groups with institutional affiliation or proximity to The Johns Hopkins Hospital: all general internal medicine faculty with outpatient practices (“academic,” 2 practice sites, n = 35), all community-based PCPs affiliated with the health system (“community,” 36 practice sites, n = 220), and all PCPs from an unaffiliated managed care organization (“unaffiliated,” 5 practice sites ranging from 0.3 to 4 miles from The Johns Hopkins Hospital, n = 29).

All groups have work-sponsored e-mail services. At the time of the survey, both the academic and community groups used an EHR that allowed access to inpatient laboratory and radiology data and discharge summaries. The unaffiliated group used paper health records. The hospital faxes discharge summaries to all PCPs who are identified by patients.

The investigators and representatives from each practice group collaborated to develop 15 questions with mutually exclusive answers to evaluate PCP experiences with and preferences for communication with inpatient teams. The survey was constructed and administered through Qualtrics’ online platform (Qualtrics, Provo, UT) and distributed via e-mail. The study was reviewed and acknowledged by the Johns Hopkins institutional review board as quality improvement activity.

The survey contained branching logic. Only respondents who indicated preference for communication received questions regarding preferred mode of communication. We used the preferred mode of communication for initial contact from the inpatient team in our analysis. χ2 and Fischer’s exact tests were performed with JMP 12 software (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Fourteen (40%) academic, 43 (14%) community, and 16 (55%) unaffiliated PCPs completed the survey, for 73 total responses from 284 surveys distributed (26%).

Among the 73 responding PCPs, 31 (42%) reported receiving notification of admission during “every” or “almost every” hospitalization, with no significant variation across practice groups (P = 0.5).

Across all groups, 64 PCPs (88%) preferred communication at 1 or more points during hospitalizations (panel A of Figure). “Both upon admission and prior to discharge” was selected most frequently, and there were no differences between practice groups (P = 0.2).

Preferred mode of communication, however, differed significantly between groups (panel B of Figure). The academic group had a greater preference for telephone (54%) than the community (8%; P < 0.001) and unaffiliated groups (8%; P < 0.001), the community group a greater preference for EHR (77%) than the academic (23%; P = 0.002) and unaffiliated groups (0%; P < 0.001), and the unaffiliated group a greater preference for fax (58%) than the other groups (both 0%; P < 0.001).

DISCUSSION

Our findings add to previous evidence of low rates of communication between inpatient providers and PCPs6 and a preference from PCPs for communication during hospitalizations despite shared EHRs.5 We extend previous work by demonstrating that PCP preferences for mode of communication vary by practice setting. Our findings lead us to hypothesize that identifying and incorporating PCP preferences may improve communication, though at the potential expense of standardization and efficiency.

There may be several reasons for the differing communication preferences observed. Most academic PCPs are located near or have admitting privileges to the hospital and are not in clinic full time. Their preference for the telephone may thus result from interpersonal relationships born from proximity and greater availability for telephone calls, or reduced fluency with the EHR compared to full-time community clinicians.

The unaffiliated group’s preference for fax may reflect a desire for communication that integrates easily with paper charts and is least disruptive to workflow, or concerns about health information confidentiality in e-mails.

Our study’s generalizability is limited by a low response rate, though it is comparable to prior studies.7 The unaffiliated group was accessed by convenience (acquaintance with the medical director); however, we note it had the highest response rate (55%).

In summary, we found low rates of communication between inpatient providers and PCPs, despite a strong preference from most PCPs for such communication during hospitalizations. PCPs’ preferred mode of communication differed based on practice setting. Addressing PCP communication preferences may be important to future care transition interventions.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

1. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-174. PubMed

2. Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, McGinn T. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(8):646-651. PubMed

3. van Walraven C, Mamdani M, Fang J, Austin PC. Continuity of care and patient outcomes after hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(6):624-631. PubMed

4. Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of Care Consensus policy statement: American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College Of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency M. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(6):364-370. PubMed

5. Sheu L, Fung K, Mourad M, Ranji S, Wu E. We need to talk: Primary care provider communication at discharge in the era of a shared electronic medical record. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(5):307-310. PubMed

6. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831-841. PubMed

7. Pantilat SZ, Lindenauer PK, Katz PP, Wachter RM. Primary care physician attitudes regarding communication with hospitalists. Am J Med. 2001(9B);111:15-20. PubMed

1. Forster AJ, Murff HJ, Peterson JF, Gandhi TK, Bates DW. The incidence and severity of adverse events affecting patients after discharge from the hospital. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(3):161-174. PubMed

2. Moore C, Wisnivesky J, Williams S, McGinn T. Medical errors related to discontinuity of care from an inpatient to an outpatient setting. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(8):646-651. PubMed

3. van Walraven C, Mamdani M, Fang J, Austin PC. Continuity of care and patient outcomes after hospital discharge. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(6):624-631. PubMed

4. Snow V, Beck D, Budnitz T, et al. Transitions of Care Consensus policy statement: American College of Physicians, Society of General Internal Medicine, Society of Hospital Medicine, American Geriatrics Society, American College Of Emergency Physicians, and Society for Academic Emergency M. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(6):364-370. PubMed

5. Sheu L, Fung K, Mourad M, Ranji S, Wu E. We need to talk: Primary care provider communication at discharge in the era of a shared electronic medical record. J Hosp Med. 2015;10(5):307-310. PubMed

6. Kripalani S, LeFevre F, Phillips CO, Williams MV, Basaviah P, Baker DW. Deficits in communication and information transfer between hospital-based and primary care physicians. JAMA. 2007;297(8):831-841. PubMed

7. Pantilat SZ, Lindenauer PK, Katz PP, Wachter RM. Primary care physician attitudes regarding communication with hospitalists. Am J Med. 2001(9B);111:15-20. PubMed

© 2017 Society of Hospital Medicine

[email protected]