User login

You, Me, and Your A1C

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

This video was filmed at Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit (MEDS). Click here to learn more.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

This video was filmed at Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit (MEDS). Click here to learn more.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

This video was filmed at Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit (MEDS). Click here to learn more.

Myth Buster: Adrenal “Fatigue”

This video was filmed at Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit (MEDS). Click here to learn more.

This video was filmed at Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit (MEDS). Click here to learn more.

This video was filmed at Metabolic & Endocrine Disease Summit (MEDS). Click here to learn more.

Adrenal “incidentalomas”

Partnering With Patients to Optimize Diabetes Therapy

IN THIS ARTICLE

• Fasting versus postprandial glucose contribution to A1C

• General glycemic targets for individuals with T2DM

• Sonja's blood glucose log

• Glycemic impact of noninsulin agents available for T2DM

• Considerations when determining glycemic targets

“… Our ability to help others is a source of pride and satisfaction; however, if we listen, really listen to our patients, we may discover that they are also experts, problem-solvers, and teachers. If we allow our patients to also be our teachers, we may someday realize that although we began with knowledge, we ended up with wisdom.” — 1,000 Years of Diabetes Wisdom

(Marrero DG et al, eds)

The pharmacotherapeutic options available for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) have expanded exponentially in the past 15 years. Although this is great news, having so many therapeutic options has led to confusion for both patients and health care providers (HCPs) as they consider which agent or combination of agents is most appropriate for glucose management, while also considering efficacy, safety, adverse effects, patient preferences, and cost.

Current expert recommendations and guidelines provide algorithms that assist the HCP with selecting medications based on safety (avoiding hypoglycemia), adverse-effect profile (eg, weight gain), and efficacy (predicted A1C reduction). These same guidelines also recommend that the choice of antihyperglycemic agent(s) be individualized according to the patient’s health status and personal preferences.

True success in diabetes management requires not only the knowledge and expertise of the clinician, but also the active involvement of the patient as a partner in health care decision making.

Continue for patient presentation/history >>

PATIENT PRESENTATION/HISTORY

We will explore a combined glucose-centric/patient-focused approach with our patient, Sonja.

Sonja is a 38-year-old Latina woman who was diagnosed with T2DM one week ago. She was being closely monitored for diabetes due to a strong family history for T2DM (father, two sisters, and several aunts/uncles affected), high-risk ethnicity, and history of gestational diabetes. Two years ago, when she was told she had prediabetes, she attempted to make appropriate therapeutic lifestyle changes.

Sonja is significantly overweight, with a BMI (29) bordering on obesity. She is inconsistent in her approach to exercise, and her long working hours as a dentist have contributed to a sedentary lifestyle. However, she made a concerted effort to change her diet and successfully lost 18 lb in the past year. Unfortunately, she then experienced considerable stress in her personal life and regained the weight, plus an additional 6 lb.

She presents today to review recent laboratory test results, which include a fasting glucose of 133 mg/dL; serum creatinine (SCr), 1.0 mg/dL; estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), 103 mL/min; A1C, 7.2%; and aspartate transaminase/alanine transaminase (AST/ALT), normal. Sonja says she feels “defeated, frustrated, and helpless” in her attempt to control her weight and thus her inability to avoid T2DM. Fortunately, she wants to change and is determined to do whatever is necessary.

Continue for treatment/management >>

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

Current guidelines from the American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes (ADA/EASD) and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) advise that in addition to a therapeutic lifestyle (adequate physical activity, healthy diet, and weight control), metformin is the drug of choice and is recommended as firstline therapy.1,2

The many available pharmacologic options can make the choice of agents after metformin use an overwhelming task, especially if the HCP has limited experience with them. The 2015 ADA/EASD and AACE algorithms help guide decision making by prioritizing the medications according to efficacy, safety, and adverse-effect profiles.1,2

Emphasis is placed on choosing medications that have low potential for hypoglycemia and, if possible, avoiding medications that may cause weight gain. Additionally, HCPs must take into account patient concerns about adverse effects, convenience/ease of use, mode of administration, and cost. Engaging patients about what is important to them and addressing their beliefs, desires, and fears are key components of individualizing therapy and are essential for successful treatment outcomes.

While Sonja’s current labs suggest that she would be an appropriate candidate for metformin, the drug’s known potential for gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects is concerning because of Sonja’s underlying history of diarrhea-dominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). She remarks that while her IBS is currently controlled, she is wary of developing problems. You respond that extended-release metformin is generally better tolerated than the immediate-release preparations, but it may cost more. She considers this and is willing to try the extended-release option; you instruct her to increase her dose by one 500-mg tablet every week, as tolerated, to reduce the risk for intolerance.

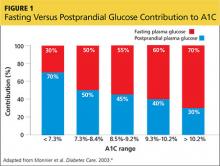

You also discuss blood-glucose testing with her. While she is not taking a medication that will cause hypoglycemia, you explain that structured self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) will provide her immediate feedback about the effects of her lifestyle changes, as well as the effect of the medication, on her blood sugar control.3 Her A1C of 7.2% suggests postprandial glucose (PPG) as a significant contributing factor; thus, it would be beneficial to measure this value regularly (see Figure 14).

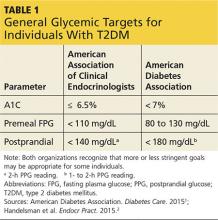

You show Sonja the AACE and ADA therapeutic blood glucose parameters required for optimal glucose control so she can see the impact of her efforts (see Table 11,2). She is willing to test her blood sugar twice daily and agrees to test before and then two hours after a different meal each day (this is known as paired testing).5

Sonja returns two weeks later with her blood glucose log for review (see Figure 2). She is pleased with her improved glucose values but has been unable to exceed 1,000 mg/d due to frequent daytime diarrhea that interferes with work. She requests a change of medication.

Continue for therapeutic considerations >>

THERAPEUTIC CONSIDERATIONS

Glucose-centric

Sonja’s glucose log demonstrates that her blood glucose values are at target with her current dose of extended-release metformin. Based on her glucose patterns and A1C, an agent of choice would be one that best directs its action on postprandial hyperglycemia. Fortunately, at this point in Sonja’s disease state, she should be able to achieve an A1C of < 7% with any of the noninsulin options.

However, when applying the glucose-centric approach, the proper course should be to use an agent that best addresses postprandial hyperglycemia. These agents include glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA), dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP4i), sulfonylureas (SU), glinide, and α-glucosidase inhibitors (AGI) (see Table 2). Other agents would be less effective in addressing PPG.

Patient-focused

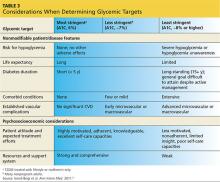

Since Sonja is young, has new-onset T2DM, is otherwise healthy, and has no overt complications from diabetes, her A1C goal should be < 6.5% and perhaps even < 6%, while minimizing the risk for hypoglycemia (see Table 3). However, she continues to be concerned with taking medications associated with any GI-related adverse effects.

The following are discussion points for Sonja regarding the agents approved as monotherapy or as monotherapy when metformin is contraindicated or not tolerated. Although all these classes have potential adverse effects, only GI intolerance and possibility for weight gain are covered here, since these directly pertain to Sonja’s choice of agent.

GLP-1RA (exenatide, liraglutide, exenatide extended-release, albiglutide, dulaglutide).7 This class, along with DPP4i, is also referred to as the incretins. The GLP-1RAs predominately target postprandial hyperglycemia and, to a lesser degree, fasting hyperglycemia—especially when used with the daily options of exenatide and/or liraglutide. The once-weekly options (exenatide extended-release, albiglutide, dulaglutide) have beneficial effects on both fasting and postprandial hyperglycemia.

Though GLP-1RAs are typically well tolerated, the most common associated adverse effects are nausea, which usually resolves in several weeks, and vomiting, which occurs infrequently. The GLP-1RAs are also one of two classes of diabetes medications associated with modest weight loss (the other is sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors [SGLT2i], to be discussed shortly). An additional benefit of GLP-1RA agents is that they are not associated with hypoglycemia, since they exert their effect in a glucose-dependent manner (ie, only when blood sugar is increased).

While Sonja is not averse to using an injectable agent, she is extremely hesitant to use any agent that may cause GI upset.

DPP4i (sitagliptin, saxagliptin, linagliptin, alogliptin).7 As previously stated, these are in the incretin class along with the GLP-1RAs. They help maintain physiologic levels of endogenous GLP-1, compared with the nearly eightfold pharmacologic level of GLP-1 from the injectable GLP-1RA. DPP4i agents are a physiologically appropriate choice for Sonja, because their effect is primarily on postprandial hyperglycemia. Since these medications also function in a glucose-dependent manner, they are not associated with hypoglycemia.

You explain to Sonja that while the DPP4i agents have a very low GI adverse-effect profile (compared with GLP-1RAs), they are not associated with weight loss but are considered weight neutral.

SU (glyburide, glipizide, glimepiride) and glinides (nateglinide, repaglinide).7 The SU class has a much longer half-life than the glinides and as a result affects both fasting glucose and PPG. The quicker-acting glinides improve PPG extremely well. However, because of the short duration of action, they must be dosed before each meal and sometimes before snacks as well. Since both of these classes stimulate insulin production, they carry a risk for hypoglycemia, but less than for the glinides.8

These agents are generally well tolerated, have a low GI adverse-effect profile, and can be associated with modest weight gain. But the risk for hypoglycemia means they may not be the optimal choice for Sonja.

SGLT2i (canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin).7 The mechanism of action for this class is rather unique in that it reduces re-absorption of glucose by the kidneys, resulting in increased urinary glucose output (glycosuria). This class has been shown to demonstrate modest weight loss. Since increased insulin secretion is not an effect of this class, it carries a very low risk for hypoglycemia.

While SGLT2i medications have a low GI adverse-effect profile, Sonja should be alerted to the associated increased urination, as it may impact her busy work schedule caring for patients.

TZD (rosiglitazone, pioglitazone).7 This is the most effective class for addressing insulin resistance, the key physiologic defect in T2DM. TZD is the only class that has demonstrated long-term A1C reductions (> 5 y).9 The drugs in this class are not associated with hypoglycemia and have a low GI adverse-effect profile. The most common adverse effects are weight gain and fluid retention, which are even more commonly observed in patients also taking insulin. Additionally, there is concern about increased risk for atypical fractures in women, particularly postmenopausal women.

Sonja should be made aware of this potential risk during her postmenopausal years, should she use one of these agents long-term. Currently, however, this would still be a viable option for her since she is early in the course of her disease and likely still has fairly good β-cell function.

AGI (acarbose, miglitol).7 This class is a good choice for directing therapy at postprandial elevations without hypoglycemia and is weight-neutral. Unfortunately, use of these agents has fallen out of favor since they are associated with significant GI adverse effects (ie, bloating, flatulence) and require multiple daily doses, with specific timing before each meal.

Insulin. Insulin is always an option for patients with diabetes, and it is the most effective and natural agent available. However, Sonja’s A1C and glucose pattern—consisting of mild postprandial elevations and near-target fasting glucose—suggest that she does not yet require this medication. Additionally, the risks for hypoglycemia and weight gain make this choice less desirable when other effective therapies are available.

After you have spent time discussing feasible options with Sonja, she decides that she would like to try a DPP4i. You agree and support her decision.

In your discussion, you also reiterate that T2DM is a progressive disease and that Sonja will likely need to use additional agents, possibly even insulin, in the years to come. You encourage her to strive for ongoing good dietary habits, exercise, and weight loss/maintenance, as these measures can lengthen the time before additional diabetes agents are needed.

To assist her with achieving these goals, you refer Sonja to a certified diabetes educator (CDE). The CDE, an integral member of the diabetes management team, will partner with Sonja to develop a plan to successfully implement these necessary lifestyle modifications.

Continue for the conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

Metformin is safe, efficacious, and recommended as a firstline therapy. However, even the best and most effective medication is no good if not taken. Adverse effects, convenience, fears—as perceived by the patient—will ultimately determine treatment success. Therefore, it is often necessary and appropriate to consider other agents in order to meet both the glycemic challenges and the personal choice of patients.

HCPs must incorporate a glucose-centric approach when initiating and advancing noninsulin therapies in order to maximize efficacy, safety, tolerability, and adherence. We must engage patients and involve them as partners in shared decision making. Merging the science of the medications along with realistic preferences of patients solidifies a better provider-patient relationship that will increase the likelihood of meeting glycemic goals and preventing diabetes-related complications and burdens.

REFERENCES

1. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2015. Diabetes Care. 2015:38(suppl 1):1-99.

2. Handelsman Y, Bloomgarden ZT, Grunberger G, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology: clinical practice guidelines for developing a diabetes mellitus comprehensive care plan—2015. Endocr Pract. 2015;21(suppl 1):1-87.

3. International Diabetes Federation. Guideline: self-monitoring of blood glucose in non–insulin treated type 2 diabetes (2009). www.idf.org/guidelines/self-monitoring. Accessed November 24, 2015.

4. Monnier L, Lapinski H, Colette C. Contributions of fasting and postprandial plasma glucose increments to the overall diurnal hyperglycemia of type 2 diabetic patients: variations with increasing levels of HbA(1c). Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):881-885.

5. Parkin CG, Hinnen D, Campbell RK, et al. Effective use of paired testing in type 2 diabetes: practical applications in clinical practice. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35(6):915-927.

6. Ismail-Beigi F, Moghissi E, Tiktin M, et al. Individualizing glycemic targets in type 2 diabetes mellitus: implications of recent clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(8):554-559.

7. FDA. Drugs@FDA: FDA approved drug products. www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm. Accessed November 20, 2015.

8. Gerich J, Raskin P, Jean-Louis L, et al. PRESERVE-beta: two-year efficacy and safety of initial combination therapy with nateglinide or glyburide plus metformin. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(9):2093-2099.

9. Kahn SE, Haffner SM, Heise MA, et al; ADOPT Study Group. Glycemic durability of rosiglitazone, metformin, or glyburide monotherapy [erratum in N Engl J Med. 2007 Mar 29;356(13):1387-1388]. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355(23):2427-2443.

IN THIS ARTICLE

• Fasting versus postprandial glucose contribution to A1C

• General glycemic targets for individuals with T2DM

• Sonja's blood glucose log

• Glycemic impact of noninsulin agents available for T2DM

• Considerations when determining glycemic targets

“… Our ability to help others is a source of pride and satisfaction; however, if we listen, really listen to our patients, we may discover that they are also experts, problem-solvers, and teachers. If we allow our patients to also be our teachers, we may someday realize that although we began with knowledge, we ended up with wisdom.” — 1,000 Years of Diabetes Wisdom

(Marrero DG et al, eds)

The pharmacotherapeutic options available for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) have expanded exponentially in the past 15 years. Although this is great news, having so many therapeutic options has led to confusion for both patients and health care providers (HCPs) as they consider which agent or combination of agents is most appropriate for glucose management, while also considering efficacy, safety, adverse effects, patient preferences, and cost.

Current expert recommendations and guidelines provide algorithms that assist the HCP with selecting medications based on safety (avoiding hypoglycemia), adverse-effect profile (eg, weight gain), and efficacy (predicted A1C reduction). These same guidelines also recommend that the choice of antihyperglycemic agent(s) be individualized according to the patient’s health status and personal preferences.

True success in diabetes management requires not only the knowledge and expertise of the clinician, but also the active involvement of the patient as a partner in health care decision making.

Continue for patient presentation/history >>

PATIENT PRESENTATION/HISTORY

We will explore a combined glucose-centric/patient-focused approach with our patient, Sonja.

Sonja is a 38-year-old Latina woman who was diagnosed with T2DM one week ago. She was being closely monitored for diabetes due to a strong family history for T2DM (father, two sisters, and several aunts/uncles affected), high-risk ethnicity, and history of gestational diabetes. Two years ago, when she was told she had prediabetes, she attempted to make appropriate therapeutic lifestyle changes.

Sonja is significantly overweight, with a BMI (29) bordering on obesity. She is inconsistent in her approach to exercise, and her long working hours as a dentist have contributed to a sedentary lifestyle. However, she made a concerted effort to change her diet and successfully lost 18 lb in the past year. Unfortunately, she then experienced considerable stress in her personal life and regained the weight, plus an additional 6 lb.

She presents today to review recent laboratory test results, which include a fasting glucose of 133 mg/dL; serum creatinine (SCr), 1.0 mg/dL; estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), 103 mL/min; A1C, 7.2%; and aspartate transaminase/alanine transaminase (AST/ALT), normal. Sonja says she feels “defeated, frustrated, and helpless” in her attempt to control her weight and thus her inability to avoid T2DM. Fortunately, she wants to change and is determined to do whatever is necessary.

Continue for treatment/management >>

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

Current guidelines from the American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes (ADA/EASD) and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) advise that in addition to a therapeutic lifestyle (adequate physical activity, healthy diet, and weight control), metformin is the drug of choice and is recommended as firstline therapy.1,2

The many available pharmacologic options can make the choice of agents after metformin use an overwhelming task, especially if the HCP has limited experience with them. The 2015 ADA/EASD and AACE algorithms help guide decision making by prioritizing the medications according to efficacy, safety, and adverse-effect profiles.1,2

Emphasis is placed on choosing medications that have low potential for hypoglycemia and, if possible, avoiding medications that may cause weight gain. Additionally, HCPs must take into account patient concerns about adverse effects, convenience/ease of use, mode of administration, and cost. Engaging patients about what is important to them and addressing their beliefs, desires, and fears are key components of individualizing therapy and are essential for successful treatment outcomes.

While Sonja’s current labs suggest that she would be an appropriate candidate for metformin, the drug’s known potential for gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects is concerning because of Sonja’s underlying history of diarrhea-dominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). She remarks that while her IBS is currently controlled, she is wary of developing problems. You respond that extended-release metformin is generally better tolerated than the immediate-release preparations, but it may cost more. She considers this and is willing to try the extended-release option; you instruct her to increase her dose by one 500-mg tablet every week, as tolerated, to reduce the risk for intolerance.

You also discuss blood-glucose testing with her. While she is not taking a medication that will cause hypoglycemia, you explain that structured self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) will provide her immediate feedback about the effects of her lifestyle changes, as well as the effect of the medication, on her blood sugar control.3 Her A1C of 7.2% suggests postprandial glucose (PPG) as a significant contributing factor; thus, it would be beneficial to measure this value regularly (see Figure 14).

You show Sonja the AACE and ADA therapeutic blood glucose parameters required for optimal glucose control so she can see the impact of her efforts (see Table 11,2). She is willing to test her blood sugar twice daily and agrees to test before and then two hours after a different meal each day (this is known as paired testing).5

Sonja returns two weeks later with her blood glucose log for review (see Figure 2). She is pleased with her improved glucose values but has been unable to exceed 1,000 mg/d due to frequent daytime diarrhea that interferes with work. She requests a change of medication.

Continue for therapeutic considerations >>

THERAPEUTIC CONSIDERATIONS

Glucose-centric

Sonja’s glucose log demonstrates that her blood glucose values are at target with her current dose of extended-release metformin. Based on her glucose patterns and A1C, an agent of choice would be one that best directs its action on postprandial hyperglycemia. Fortunately, at this point in Sonja’s disease state, she should be able to achieve an A1C of < 7% with any of the noninsulin options.

However, when applying the glucose-centric approach, the proper course should be to use an agent that best addresses postprandial hyperglycemia. These agents include glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA), dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP4i), sulfonylureas (SU), glinide, and α-glucosidase inhibitors (AGI) (see Table 2). Other agents would be less effective in addressing PPG.

Patient-focused

Since Sonja is young, has new-onset T2DM, is otherwise healthy, and has no overt complications from diabetes, her A1C goal should be < 6.5% and perhaps even < 6%, while minimizing the risk for hypoglycemia (see Table 3). However, she continues to be concerned with taking medications associated with any GI-related adverse effects.

The following are discussion points for Sonja regarding the agents approved as monotherapy or as monotherapy when metformin is contraindicated or not tolerated. Although all these classes have potential adverse effects, only GI intolerance and possibility for weight gain are covered here, since these directly pertain to Sonja’s choice of agent.

GLP-1RA (exenatide, liraglutide, exenatide extended-release, albiglutide, dulaglutide).7 This class, along with DPP4i, is also referred to as the incretins. The GLP-1RAs predominately target postprandial hyperglycemia and, to a lesser degree, fasting hyperglycemia—especially when used with the daily options of exenatide and/or liraglutide. The once-weekly options (exenatide extended-release, albiglutide, dulaglutide) have beneficial effects on both fasting and postprandial hyperglycemia.

Though GLP-1RAs are typically well tolerated, the most common associated adverse effects are nausea, which usually resolves in several weeks, and vomiting, which occurs infrequently. The GLP-1RAs are also one of two classes of diabetes medications associated with modest weight loss (the other is sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors [SGLT2i], to be discussed shortly). An additional benefit of GLP-1RA agents is that they are not associated with hypoglycemia, since they exert their effect in a glucose-dependent manner (ie, only when blood sugar is increased).

While Sonja is not averse to using an injectable agent, she is extremely hesitant to use any agent that may cause GI upset.

DPP4i (sitagliptin, saxagliptin, linagliptin, alogliptin).7 As previously stated, these are in the incretin class along with the GLP-1RAs. They help maintain physiologic levels of endogenous GLP-1, compared with the nearly eightfold pharmacologic level of GLP-1 from the injectable GLP-1RA. DPP4i agents are a physiologically appropriate choice for Sonja, because their effect is primarily on postprandial hyperglycemia. Since these medications also function in a glucose-dependent manner, they are not associated with hypoglycemia.

You explain to Sonja that while the DPP4i agents have a very low GI adverse-effect profile (compared with GLP-1RAs), they are not associated with weight loss but are considered weight neutral.

SU (glyburide, glipizide, glimepiride) and glinides (nateglinide, repaglinide).7 The SU class has a much longer half-life than the glinides and as a result affects both fasting glucose and PPG. The quicker-acting glinides improve PPG extremely well. However, because of the short duration of action, they must be dosed before each meal and sometimes before snacks as well. Since both of these classes stimulate insulin production, they carry a risk for hypoglycemia, but less than for the glinides.8

These agents are generally well tolerated, have a low GI adverse-effect profile, and can be associated with modest weight gain. But the risk for hypoglycemia means they may not be the optimal choice for Sonja.

SGLT2i (canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin).7 The mechanism of action for this class is rather unique in that it reduces re-absorption of glucose by the kidneys, resulting in increased urinary glucose output (glycosuria). This class has been shown to demonstrate modest weight loss. Since increased insulin secretion is not an effect of this class, it carries a very low risk for hypoglycemia.

While SGLT2i medications have a low GI adverse-effect profile, Sonja should be alerted to the associated increased urination, as it may impact her busy work schedule caring for patients.

TZD (rosiglitazone, pioglitazone).7 This is the most effective class for addressing insulin resistance, the key physiologic defect in T2DM. TZD is the only class that has demonstrated long-term A1C reductions (> 5 y).9 The drugs in this class are not associated with hypoglycemia and have a low GI adverse-effect profile. The most common adverse effects are weight gain and fluid retention, which are even more commonly observed in patients also taking insulin. Additionally, there is concern about increased risk for atypical fractures in women, particularly postmenopausal women.

Sonja should be made aware of this potential risk during her postmenopausal years, should she use one of these agents long-term. Currently, however, this would still be a viable option for her since she is early in the course of her disease and likely still has fairly good β-cell function.

AGI (acarbose, miglitol).7 This class is a good choice for directing therapy at postprandial elevations without hypoglycemia and is weight-neutral. Unfortunately, use of these agents has fallen out of favor since they are associated with significant GI adverse effects (ie, bloating, flatulence) and require multiple daily doses, with specific timing before each meal.

Insulin. Insulin is always an option for patients with diabetes, and it is the most effective and natural agent available. However, Sonja’s A1C and glucose pattern—consisting of mild postprandial elevations and near-target fasting glucose—suggest that she does not yet require this medication. Additionally, the risks for hypoglycemia and weight gain make this choice less desirable when other effective therapies are available.

After you have spent time discussing feasible options with Sonja, she decides that she would like to try a DPP4i. You agree and support her decision.

In your discussion, you also reiterate that T2DM is a progressive disease and that Sonja will likely need to use additional agents, possibly even insulin, in the years to come. You encourage her to strive for ongoing good dietary habits, exercise, and weight loss/maintenance, as these measures can lengthen the time before additional diabetes agents are needed.

To assist her with achieving these goals, you refer Sonja to a certified diabetes educator (CDE). The CDE, an integral member of the diabetes management team, will partner with Sonja to develop a plan to successfully implement these necessary lifestyle modifications.

Continue for the conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

Metformin is safe, efficacious, and recommended as a firstline therapy. However, even the best and most effective medication is no good if not taken. Adverse effects, convenience, fears—as perceived by the patient—will ultimately determine treatment success. Therefore, it is often necessary and appropriate to consider other agents in order to meet both the glycemic challenges and the personal choice of patients.

HCPs must incorporate a glucose-centric approach when initiating and advancing noninsulin therapies in order to maximize efficacy, safety, tolerability, and adherence. We must engage patients and involve them as partners in shared decision making. Merging the science of the medications along with realistic preferences of patients solidifies a better provider-patient relationship that will increase the likelihood of meeting glycemic goals and preventing diabetes-related complications and burdens.

REFERENCES

1. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2015. Diabetes Care. 2015:38(suppl 1):1-99.

2. Handelsman Y, Bloomgarden ZT, Grunberger G, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology: clinical practice guidelines for developing a diabetes mellitus comprehensive care plan—2015. Endocr Pract. 2015;21(suppl 1):1-87.

3. International Diabetes Federation. Guideline: self-monitoring of blood glucose in non–insulin treated type 2 diabetes (2009). www.idf.org/guidelines/self-monitoring. Accessed November 24, 2015.

4. Monnier L, Lapinski H, Colette C. Contributions of fasting and postprandial plasma glucose increments to the overall diurnal hyperglycemia of type 2 diabetic patients: variations with increasing levels of HbA(1c). Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):881-885.

5. Parkin CG, Hinnen D, Campbell RK, et al. Effective use of paired testing in type 2 diabetes: practical applications in clinical practice. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35(6):915-927.

6. Ismail-Beigi F, Moghissi E, Tiktin M, et al. Individualizing glycemic targets in type 2 diabetes mellitus: implications of recent clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(8):554-559.

7. FDA. Drugs@FDA: FDA approved drug products. www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm. Accessed November 20, 2015.

8. Gerich J, Raskin P, Jean-Louis L, et al. PRESERVE-beta: two-year efficacy and safety of initial combination therapy with nateglinide or glyburide plus metformin. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(9):2093-2099.

9. Kahn SE, Haffner SM, Heise MA, et al; ADOPT Study Group. Glycemic durability of rosiglitazone, metformin, or glyburide monotherapy [erratum in N Engl J Med. 2007 Mar 29;356(13):1387-1388]. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355(23):2427-2443.

IN THIS ARTICLE

• Fasting versus postprandial glucose contribution to A1C

• General glycemic targets for individuals with T2DM

• Sonja's blood glucose log

• Glycemic impact of noninsulin agents available for T2DM

• Considerations when determining glycemic targets

“… Our ability to help others is a source of pride and satisfaction; however, if we listen, really listen to our patients, we may discover that they are also experts, problem-solvers, and teachers. If we allow our patients to also be our teachers, we may someday realize that although we began with knowledge, we ended up with wisdom.” — 1,000 Years of Diabetes Wisdom

(Marrero DG et al, eds)

The pharmacotherapeutic options available for the treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) have expanded exponentially in the past 15 years. Although this is great news, having so many therapeutic options has led to confusion for both patients and health care providers (HCPs) as they consider which agent or combination of agents is most appropriate for glucose management, while also considering efficacy, safety, adverse effects, patient preferences, and cost.

Current expert recommendations and guidelines provide algorithms that assist the HCP with selecting medications based on safety (avoiding hypoglycemia), adverse-effect profile (eg, weight gain), and efficacy (predicted A1C reduction). These same guidelines also recommend that the choice of antihyperglycemic agent(s) be individualized according to the patient’s health status and personal preferences.

True success in diabetes management requires not only the knowledge and expertise of the clinician, but also the active involvement of the patient as a partner in health care decision making.

Continue for patient presentation/history >>

PATIENT PRESENTATION/HISTORY

We will explore a combined glucose-centric/patient-focused approach with our patient, Sonja.

Sonja is a 38-year-old Latina woman who was diagnosed with T2DM one week ago. She was being closely monitored for diabetes due to a strong family history for T2DM (father, two sisters, and several aunts/uncles affected), high-risk ethnicity, and history of gestational diabetes. Two years ago, when she was told she had prediabetes, she attempted to make appropriate therapeutic lifestyle changes.

Sonja is significantly overweight, with a BMI (29) bordering on obesity. She is inconsistent in her approach to exercise, and her long working hours as a dentist have contributed to a sedentary lifestyle. However, she made a concerted effort to change her diet and successfully lost 18 lb in the past year. Unfortunately, she then experienced considerable stress in her personal life and regained the weight, plus an additional 6 lb.

She presents today to review recent laboratory test results, which include a fasting glucose of 133 mg/dL; serum creatinine (SCr), 1.0 mg/dL; estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR), 103 mL/min; A1C, 7.2%; and aspartate transaminase/alanine transaminase (AST/ALT), normal. Sonja says she feels “defeated, frustrated, and helpless” in her attempt to control her weight and thus her inability to avoid T2DM. Fortunately, she wants to change and is determined to do whatever is necessary.

Continue for treatment/management >>

TREATMENT/MANAGEMENT

Current guidelines from the American Diabetes Association/European Association for the Study of Diabetes (ADA/EASD) and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists (AACE) advise that in addition to a therapeutic lifestyle (adequate physical activity, healthy diet, and weight control), metformin is the drug of choice and is recommended as firstline therapy.1,2

The many available pharmacologic options can make the choice of agents after metformin use an overwhelming task, especially if the HCP has limited experience with them. The 2015 ADA/EASD and AACE algorithms help guide decision making by prioritizing the medications according to efficacy, safety, and adverse-effect profiles.1,2

Emphasis is placed on choosing medications that have low potential for hypoglycemia and, if possible, avoiding medications that may cause weight gain. Additionally, HCPs must take into account patient concerns about adverse effects, convenience/ease of use, mode of administration, and cost. Engaging patients about what is important to them and addressing their beliefs, desires, and fears are key components of individualizing therapy and are essential for successful treatment outcomes.

While Sonja’s current labs suggest that she would be an appropriate candidate for metformin, the drug’s known potential for gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects is concerning because of Sonja’s underlying history of diarrhea-dominant irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). She remarks that while her IBS is currently controlled, she is wary of developing problems. You respond that extended-release metformin is generally better tolerated than the immediate-release preparations, but it may cost more. She considers this and is willing to try the extended-release option; you instruct her to increase her dose by one 500-mg tablet every week, as tolerated, to reduce the risk for intolerance.

You also discuss blood-glucose testing with her. While she is not taking a medication that will cause hypoglycemia, you explain that structured self-monitoring of blood glucose (SMBG) will provide her immediate feedback about the effects of her lifestyle changes, as well as the effect of the medication, on her blood sugar control.3 Her A1C of 7.2% suggests postprandial glucose (PPG) as a significant contributing factor; thus, it would be beneficial to measure this value regularly (see Figure 14).

You show Sonja the AACE and ADA therapeutic blood glucose parameters required for optimal glucose control so she can see the impact of her efforts (see Table 11,2). She is willing to test her blood sugar twice daily and agrees to test before and then two hours after a different meal each day (this is known as paired testing).5

Sonja returns two weeks later with her blood glucose log for review (see Figure 2). She is pleased with her improved glucose values but has been unable to exceed 1,000 mg/d due to frequent daytime diarrhea that interferes with work. She requests a change of medication.

Continue for therapeutic considerations >>

THERAPEUTIC CONSIDERATIONS

Glucose-centric

Sonja’s glucose log demonstrates that her blood glucose values are at target with her current dose of extended-release metformin. Based on her glucose patterns and A1C, an agent of choice would be one that best directs its action on postprandial hyperglycemia. Fortunately, at this point in Sonja’s disease state, she should be able to achieve an A1C of < 7% with any of the noninsulin options.

However, when applying the glucose-centric approach, the proper course should be to use an agent that best addresses postprandial hyperglycemia. These agents include glucagon-like peptide 1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RA), dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors (DPP4i), sulfonylureas (SU), glinide, and α-glucosidase inhibitors (AGI) (see Table 2). Other agents would be less effective in addressing PPG.

Patient-focused

Since Sonja is young, has new-onset T2DM, is otherwise healthy, and has no overt complications from diabetes, her A1C goal should be < 6.5% and perhaps even < 6%, while minimizing the risk for hypoglycemia (see Table 3). However, she continues to be concerned with taking medications associated with any GI-related adverse effects.

The following are discussion points for Sonja regarding the agents approved as monotherapy or as monotherapy when metformin is contraindicated or not tolerated. Although all these classes have potential adverse effects, only GI intolerance and possibility for weight gain are covered here, since these directly pertain to Sonja’s choice of agent.

GLP-1RA (exenatide, liraglutide, exenatide extended-release, albiglutide, dulaglutide).7 This class, along with DPP4i, is also referred to as the incretins. The GLP-1RAs predominately target postprandial hyperglycemia and, to a lesser degree, fasting hyperglycemia—especially when used with the daily options of exenatide and/or liraglutide. The once-weekly options (exenatide extended-release, albiglutide, dulaglutide) have beneficial effects on both fasting and postprandial hyperglycemia.

Though GLP-1RAs are typically well tolerated, the most common associated adverse effects are nausea, which usually resolves in several weeks, and vomiting, which occurs infrequently. The GLP-1RAs are also one of two classes of diabetes medications associated with modest weight loss (the other is sodium glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors [SGLT2i], to be discussed shortly). An additional benefit of GLP-1RA agents is that they are not associated with hypoglycemia, since they exert their effect in a glucose-dependent manner (ie, only when blood sugar is increased).

While Sonja is not averse to using an injectable agent, she is extremely hesitant to use any agent that may cause GI upset.

DPP4i (sitagliptin, saxagliptin, linagliptin, alogliptin).7 As previously stated, these are in the incretin class along with the GLP-1RAs. They help maintain physiologic levels of endogenous GLP-1, compared with the nearly eightfold pharmacologic level of GLP-1 from the injectable GLP-1RA. DPP4i agents are a physiologically appropriate choice for Sonja, because their effect is primarily on postprandial hyperglycemia. Since these medications also function in a glucose-dependent manner, they are not associated with hypoglycemia.

You explain to Sonja that while the DPP4i agents have a very low GI adverse-effect profile (compared with GLP-1RAs), they are not associated with weight loss but are considered weight neutral.

SU (glyburide, glipizide, glimepiride) and glinides (nateglinide, repaglinide).7 The SU class has a much longer half-life than the glinides and as a result affects both fasting glucose and PPG. The quicker-acting glinides improve PPG extremely well. However, because of the short duration of action, they must be dosed before each meal and sometimes before snacks as well. Since both of these classes stimulate insulin production, they carry a risk for hypoglycemia, but less than for the glinides.8

These agents are generally well tolerated, have a low GI adverse-effect profile, and can be associated with modest weight gain. But the risk for hypoglycemia means they may not be the optimal choice for Sonja.

SGLT2i (canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, empagliflozin).7 The mechanism of action for this class is rather unique in that it reduces re-absorption of glucose by the kidneys, resulting in increased urinary glucose output (glycosuria). This class has been shown to demonstrate modest weight loss. Since increased insulin secretion is not an effect of this class, it carries a very low risk for hypoglycemia.

While SGLT2i medications have a low GI adverse-effect profile, Sonja should be alerted to the associated increased urination, as it may impact her busy work schedule caring for patients.

TZD (rosiglitazone, pioglitazone).7 This is the most effective class for addressing insulin resistance, the key physiologic defect in T2DM. TZD is the only class that has demonstrated long-term A1C reductions (> 5 y).9 The drugs in this class are not associated with hypoglycemia and have a low GI adverse-effect profile. The most common adverse effects are weight gain and fluid retention, which are even more commonly observed in patients also taking insulin. Additionally, there is concern about increased risk for atypical fractures in women, particularly postmenopausal women.

Sonja should be made aware of this potential risk during her postmenopausal years, should she use one of these agents long-term. Currently, however, this would still be a viable option for her since she is early in the course of her disease and likely still has fairly good β-cell function.

AGI (acarbose, miglitol).7 This class is a good choice for directing therapy at postprandial elevations without hypoglycemia and is weight-neutral. Unfortunately, use of these agents has fallen out of favor since they are associated with significant GI adverse effects (ie, bloating, flatulence) and require multiple daily doses, with specific timing before each meal.

Insulin. Insulin is always an option for patients with diabetes, and it is the most effective and natural agent available. However, Sonja’s A1C and glucose pattern—consisting of mild postprandial elevations and near-target fasting glucose—suggest that she does not yet require this medication. Additionally, the risks for hypoglycemia and weight gain make this choice less desirable when other effective therapies are available.

After you have spent time discussing feasible options with Sonja, she decides that she would like to try a DPP4i. You agree and support her decision.

In your discussion, you also reiterate that T2DM is a progressive disease and that Sonja will likely need to use additional agents, possibly even insulin, in the years to come. You encourage her to strive for ongoing good dietary habits, exercise, and weight loss/maintenance, as these measures can lengthen the time before additional diabetes agents are needed.

To assist her with achieving these goals, you refer Sonja to a certified diabetes educator (CDE). The CDE, an integral member of the diabetes management team, will partner with Sonja to develop a plan to successfully implement these necessary lifestyle modifications.

Continue for the conclusion >>

CONCLUSION

Metformin is safe, efficacious, and recommended as a firstline therapy. However, even the best and most effective medication is no good if not taken. Adverse effects, convenience, fears—as perceived by the patient—will ultimately determine treatment success. Therefore, it is often necessary and appropriate to consider other agents in order to meet both the glycemic challenges and the personal choice of patients.

HCPs must incorporate a glucose-centric approach when initiating and advancing noninsulin therapies in order to maximize efficacy, safety, tolerability, and adherence. We must engage patients and involve them as partners in shared decision making. Merging the science of the medications along with realistic preferences of patients solidifies a better provider-patient relationship that will increase the likelihood of meeting glycemic goals and preventing diabetes-related complications and burdens.

REFERENCES

1. American Diabetes Association. Standards of medical care in diabetes—2015. Diabetes Care. 2015:38(suppl 1):1-99.

2. Handelsman Y, Bloomgarden ZT, Grunberger G, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology: clinical practice guidelines for developing a diabetes mellitus comprehensive care plan—2015. Endocr Pract. 2015;21(suppl 1):1-87.

3. International Diabetes Federation. Guideline: self-monitoring of blood glucose in non–insulin treated type 2 diabetes (2009). www.idf.org/guidelines/self-monitoring. Accessed November 24, 2015.

4. Monnier L, Lapinski H, Colette C. Contributions of fasting and postprandial plasma glucose increments to the overall diurnal hyperglycemia of type 2 diabetic patients: variations with increasing levels of HbA(1c). Diabetes Care. 2003;26(3):881-885.

5. Parkin CG, Hinnen D, Campbell RK, et al. Effective use of paired testing in type 2 diabetes: practical applications in clinical practice. Diabetes Educ. 2009;35(6):915-927.

6. Ismail-Beigi F, Moghissi E, Tiktin M, et al. Individualizing glycemic targets in type 2 diabetes mellitus: implications of recent clinical trials. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(8):554-559.

7. FDA. Drugs@FDA: FDA approved drug products. www.accessdata.fda.gov/scripts/cder/drugsatfda/index.cfm. Accessed November 20, 2015.

8. Gerich J, Raskin P, Jean-Louis L, et al. PRESERVE-beta: two-year efficacy and safety of initial combination therapy with nateglinide or glyburide plus metformin. Diabetes Care. 2005;28(9):2093-2099.

9. Kahn SE, Haffner SM, Heise MA, et al; ADOPT Study Group. Glycemic durability of rosiglitazone, metformin, or glyburide monotherapy [erratum in N Engl J Med. 2007 Mar 29;356(13):1387-1388]. N Engl J Med. 2006; 355(23):2427-2443.

Hypercalcemia, Parathyroid Disease, Vitamin D Deficiency

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

Overview of This Year’s Conference

To learn more about registering for the 2013 MEDS West conference in Irvine, CA, October 3-5, click here for complete details.

To learn more about registering for the 2013 MEDS West conference in Irvine, CA, October 3-5, click here for complete details.

To learn more about registering for the 2013 MEDS West conference in Irvine, CA, October 3-5, click here for complete details.

Lifestyle Interventions for Obese Patients

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

To hear his lecture on “Lifestyle Intervention Strategies for the Overweight Patient” please attend the 2013 MEDS West in Irvine, CA, October 3-5. Click here for complete details.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

To hear his lecture on “Lifestyle Intervention Strategies for the Overweight Patient” please attend the 2013 MEDS West in Irvine, CA, October 3-5. Click here for complete details.

The video associated with this article is no longer available on this site. Please view all of our videos on the MDedge YouTube channel

To hear his lecture on “Lifestyle Intervention Strategies for the Overweight Patient” please attend the 2013 MEDS West in Irvine, CA, October 3-5. Click here for complete details.

How to Handle "Incidentalomas"

Maggie, 42, presents to the emergency department with chronic intermittent abdominal pain and bloating with constipation and occasional diarrhea. She denies fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, melana, bright red blood per rectum, or changes in stool caliper, and she says she otherwise feels well.

Relevant lab and study results include: a comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count with differential, beta hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin), urinalysis, and amylase and lipase, all within normal limits; pregnancy test, negative; abdominal x-ray, within normal limits except increased stool in distal colon; and abdominal CT, 2.3-cm right adrenal mass and a Hounsfield measurement of 4 units.

Maggie has a right adrenal incidentaloma (incidentally discovered adenoma that was not in the differential diagnosis). Such findings have become all too often the case, due to the immediate access to and overutilization of high-resolution CT, MRI, and ultrasound. We are now seeing a significantly increased number of incidental adrenal lesions/masses discovered on images not intended to look for adrenal-related diseases (eg, Cushing syndrome, pheochromocytomas, and aldosterone-producing adenomas).

Q: How common are adrenal adenomas, and what must I consider?

Incidental adrenal adenomas are found on 4.4% of abdominal CTs, and in one autopsy series were discovered in 8.7%. Prevalence increases with age, with occurrence of < 1% in patients younger than 30 and about 7% for patients 70 or older.

Evaluation is based on two concerns: First, is the adrenal mass benign or malignant? Second, is the mass secretory or nonsecretory (non-hormone secreting) in nature?

The fortunate news about adrenal incidentalomas is that 80% are benign and nonsecretory, which provides immediate reassuring news to the patient. Examples of benign adrenal masses are: adenoma, lipoma, cyst, ganglioneuroma, hematoma, and infection (eg, tuberculosis, fungal).

The other encouraging statistic is that only 1:4,000 adrenal incidentalomas are malignant. Examples of malignant adrenal masses are: adrenocortical carcinoma, metastatic neoplasm, lymphoma, and malignant pheochromocytoma.

Q: Does adrenal adenoma size matter?

Yes, the larger the size of the adenoma, the higher the association with malignancy. The guide below (based on CT findings) shows not only malignancy potential as it relates to size, but also the importance of Hounsfield units and when surgical intervention is recommended.

Imaging (CT scan)

< 4 cm: homogeneous mass with smooth borders and < 10 Hounsfield units; suggests benign mass (likelihood of malignancy, about 2%)

4 to 6 cm: follow closely, consider surgery (likelihood of malignancy, about 6%)

> 6 cm: surgery indicated (likelihood of malignancy, about 25%)

Some providers and patients inquire whether it is helpful or necessary to biopsy. It is generally not advisable to biopsy, especially if the findings are favorable for benign nonsecretory masses, since there is a high false-negative rate. An indication for biopsy is if the patient has a history of extra-adrenal malignancy; this will distinguish recurrence or metastatic disease from a benign mass. A final proviso: If biopsy is performed, make sure the adrenal mass is not a pheochromocytoma, as biopsy of a hormone-secreting neoplasm can lead to a hypertensive emergency.

Q: How do I determine whether the mass is hormone-secreting?

Although 80% are nonsecretory, you must still maintain a high index of suspicion so as not to miss a potentially problematic and fully treatable adenoma. A thorough history is essential in screening for hormonal excess arising from adrenal adenomas, since the signs and symptoms can be insidious. The three hormones secreted by adrenal adenomas are cortisol, aldosterone, and catecholamines (seen in Cushing syndrome, aldosterone-producing adenoma [APA], and pheochromocytoma, respectively).

It is important to note that Cushing syndrome has an insidious onset and can be easily missed. Hyperaldosteronism presents with hypertension (requiring several medications) and commonly hypokalemia. And pheochromocytoma can be “written off as” anxiety disorder, panic attack, or even hypoglycemia symptoms (especially if patients are treated for diabetes with agents that cause hypoglycemia). To help in your differential diagnosis of secretory adenomas, know that APA accounts for only 1%, and therefore the majority will secrete cortisol and (far less likely) catecholamines.

Q: What is the appropriate laboratory work-up?

The best simple screening test for hypercortisolemia is a 1-mg overnight dexamethasone suppression test. If this value is increased to ≥ 3 µg/dL, it should be followed up with a more sensitive test (a 24-hour urine for creatinine and free cortisol) to further assess for hypercortisolemia.

Patients thought to have a potential pheochromocytoma should undergo measurement of plasma fractionated metanephrines and normetanephrines or 24-hour urine for total metanephrines and fractionated catecholamines.

Finally, for patients with hypokalemia and hypertension or refractory hypertension requiring multiple (> 3) antihypertensive medications, plasma renin activity (PRA) and plasma aldosterone concentration (PAC) should be obtained. A low PRA and a PAC > 15 ng/dL, along with a PAC/PRA ratio of > 20, is highly suggestive of an APA.

Q: What is the treatment and follow-up?

Here is a quick reference guide regarding surgical treatment and medical follow-up and surveillance:

• Adrenalectomy (pheochromocytoma, APA, Cushing syndrome): for masses 4 to 6 cm, consider surgery, especially if > 10 Hounsfield units; for masses > 6 cm, there is an increased risk for malignancy and surgery is required.

• Follow-up for low-suspicion, nonsecretory masses: abdominal CT 3 to 6 months after the initial scan, then annually for 1 to 2 years; hormonal evaluation and follow-up annually for 5 years, to evaluate for signs and symptoms of hormonal excess.

SUGGESTED READING

American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American Association of Endocrine Surgeons Medical Guidelines for the Management of Adrenal Incidentalomas. Endocr Pract. 2009;15(Suppl 1).

Management of the Clinically Inapparent Adrenal Mass (Incidentaloma). NIH State-of-the-Science Conference Statement; February 4-6, 2002.

Slawik M, Reincke M. Adrenal incidentalomas (Chapter 20). EndoText.com. www.endotext.org/adrenal/adrenal20/adrenal20.htm. Accessed October 12, 2012.

Fitzgerald PA, Goldfien A. Adrenal medulla. In: Greenspan F, Gardner D, eds. Basic and Clinical Endocrinology. 7th ed. McGraw-Hill: 2003;453-473.

The Washington Manual Endocrinology Specialty Consult. 2005;57-61, 71-84.

Endocrine Secrets. 4th ed. 2005;197-204, 241-252, 257-265.

Cleveland Clinic Endocrine & Metabolism Board Review. www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/live/courses/ann/endoreview/default.asp. Accessed October 12, 2012.

Maggie, 42, presents to the emergency department with chronic intermittent abdominal pain and bloating with constipation and occasional diarrhea. She denies fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, melana, bright red blood per rectum, or changes in stool caliper, and she says she otherwise feels well.

Relevant lab and study results include: a comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count with differential, beta hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin), urinalysis, and amylase and lipase, all within normal limits; pregnancy test, negative; abdominal x-ray, within normal limits except increased stool in distal colon; and abdominal CT, 2.3-cm right adrenal mass and a Hounsfield measurement of 4 units.

Maggie has a right adrenal incidentaloma (incidentally discovered adenoma that was not in the differential diagnosis). Such findings have become all too often the case, due to the immediate access to and overutilization of high-resolution CT, MRI, and ultrasound. We are now seeing a significantly increased number of incidental adrenal lesions/masses discovered on images not intended to look for adrenal-related diseases (eg, Cushing syndrome, pheochromocytomas, and aldosterone-producing adenomas).

Q: How common are adrenal adenomas, and what must I consider?

Incidental adrenal adenomas are found on 4.4% of abdominal CTs, and in one autopsy series were discovered in 8.7%. Prevalence increases with age, with occurrence of < 1% in patients younger than 30 and about 7% for patients 70 or older.

Evaluation is based on two concerns: First, is the adrenal mass benign or malignant? Second, is the mass secretory or nonsecretory (non-hormone secreting) in nature?

The fortunate news about adrenal incidentalomas is that 80% are benign and nonsecretory, which provides immediate reassuring news to the patient. Examples of benign adrenal masses are: adenoma, lipoma, cyst, ganglioneuroma, hematoma, and infection (eg, tuberculosis, fungal).

The other encouraging statistic is that only 1:4,000 adrenal incidentalomas are malignant. Examples of malignant adrenal masses are: adrenocortical carcinoma, metastatic neoplasm, lymphoma, and malignant pheochromocytoma.

Q: Does adrenal adenoma size matter?

Yes, the larger the size of the adenoma, the higher the association with malignancy. The guide below (based on CT findings) shows not only malignancy potential as it relates to size, but also the importance of Hounsfield units and when surgical intervention is recommended.

Imaging (CT scan)

< 4 cm: homogeneous mass with smooth borders and < 10 Hounsfield units; suggests benign mass (likelihood of malignancy, about 2%)

4 to 6 cm: follow closely, consider surgery (likelihood of malignancy, about 6%)

> 6 cm: surgery indicated (likelihood of malignancy, about 25%)

Some providers and patients inquire whether it is helpful or necessary to biopsy. It is generally not advisable to biopsy, especially if the findings are favorable for benign nonsecretory masses, since there is a high false-negative rate. An indication for biopsy is if the patient has a history of extra-adrenal malignancy; this will distinguish recurrence or metastatic disease from a benign mass. A final proviso: If biopsy is performed, make sure the adrenal mass is not a pheochromocytoma, as biopsy of a hormone-secreting neoplasm can lead to a hypertensive emergency.

Q: How do I determine whether the mass is hormone-secreting?

Although 80% are nonsecretory, you must still maintain a high index of suspicion so as not to miss a potentially problematic and fully treatable adenoma. A thorough history is essential in screening for hormonal excess arising from adrenal adenomas, since the signs and symptoms can be insidious. The three hormones secreted by adrenal adenomas are cortisol, aldosterone, and catecholamines (seen in Cushing syndrome, aldosterone-producing adenoma [APA], and pheochromocytoma, respectively).

It is important to note that Cushing syndrome has an insidious onset and can be easily missed. Hyperaldosteronism presents with hypertension (requiring several medications) and commonly hypokalemia. And pheochromocytoma can be “written off as” anxiety disorder, panic attack, or even hypoglycemia symptoms (especially if patients are treated for diabetes with agents that cause hypoglycemia). To help in your differential diagnosis of secretory adenomas, know that APA accounts for only 1%, and therefore the majority will secrete cortisol and (far less likely) catecholamines.

Q: What is the appropriate laboratory work-up?

The best simple screening test for hypercortisolemia is a 1-mg overnight dexamethasone suppression test. If this value is increased to ≥ 3 µg/dL, it should be followed up with a more sensitive test (a 24-hour urine for creatinine and free cortisol) to further assess for hypercortisolemia.

Patients thought to have a potential pheochromocytoma should undergo measurement of plasma fractionated metanephrines and normetanephrines or 24-hour urine for total metanephrines and fractionated catecholamines.

Finally, for patients with hypokalemia and hypertension or refractory hypertension requiring multiple (> 3) antihypertensive medications, plasma renin activity (PRA) and plasma aldosterone concentration (PAC) should be obtained. A low PRA and a PAC > 15 ng/dL, along with a PAC/PRA ratio of > 20, is highly suggestive of an APA.

Q: What is the treatment and follow-up?

Here is a quick reference guide regarding surgical treatment and medical follow-up and surveillance:

• Adrenalectomy (pheochromocytoma, APA, Cushing syndrome): for masses 4 to 6 cm, consider surgery, especially if > 10 Hounsfield units; for masses > 6 cm, there is an increased risk for malignancy and surgery is required.

• Follow-up for low-suspicion, nonsecretory masses: abdominal CT 3 to 6 months after the initial scan, then annually for 1 to 2 years; hormonal evaluation and follow-up annually for 5 years, to evaluate for signs and symptoms of hormonal excess.

SUGGESTED READING

American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American Association of Endocrine Surgeons Medical Guidelines for the Management of Adrenal Incidentalomas. Endocr Pract. 2009;15(Suppl 1).

Management of the Clinically Inapparent Adrenal Mass (Incidentaloma). NIH State-of-the-Science Conference Statement; February 4-6, 2002.

Slawik M, Reincke M. Adrenal incidentalomas (Chapter 20). EndoText.com. www.endotext.org/adrenal/adrenal20/adrenal20.htm. Accessed October 12, 2012.

Fitzgerald PA, Goldfien A. Adrenal medulla. In: Greenspan F, Gardner D, eds. Basic and Clinical Endocrinology. 7th ed. McGraw-Hill: 2003;453-473.

The Washington Manual Endocrinology Specialty Consult. 2005;57-61, 71-84.

Endocrine Secrets. 4th ed. 2005;197-204, 241-252, 257-265.

Cleveland Clinic Endocrine & Metabolism Board Review. www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/live/courses/ann/endoreview/default.asp. Accessed October 12, 2012.

Maggie, 42, presents to the emergency department with chronic intermittent abdominal pain and bloating with constipation and occasional diarrhea. She denies fever, chills, nausea, vomiting, melana, bright red blood per rectum, or changes in stool caliper, and she says she otherwise feels well.

Relevant lab and study results include: a comprehensive metabolic panel, complete blood count with differential, beta hCG (human chorionic gonadotropin), urinalysis, and amylase and lipase, all within normal limits; pregnancy test, negative; abdominal x-ray, within normal limits except increased stool in distal colon; and abdominal CT, 2.3-cm right adrenal mass and a Hounsfield measurement of 4 units.

Maggie has a right adrenal incidentaloma (incidentally discovered adenoma that was not in the differential diagnosis). Such findings have become all too often the case, due to the immediate access to and overutilization of high-resolution CT, MRI, and ultrasound. We are now seeing a significantly increased number of incidental adrenal lesions/masses discovered on images not intended to look for adrenal-related diseases (eg, Cushing syndrome, pheochromocytomas, and aldosterone-producing adenomas).

Q: How common are adrenal adenomas, and what must I consider?

Incidental adrenal adenomas are found on 4.4% of abdominal CTs, and in one autopsy series were discovered in 8.7%. Prevalence increases with age, with occurrence of < 1% in patients younger than 30 and about 7% for patients 70 or older.

Evaluation is based on two concerns: First, is the adrenal mass benign or malignant? Second, is the mass secretory or nonsecretory (non-hormone secreting) in nature?

The fortunate news about adrenal incidentalomas is that 80% are benign and nonsecretory, which provides immediate reassuring news to the patient. Examples of benign adrenal masses are: adenoma, lipoma, cyst, ganglioneuroma, hematoma, and infection (eg, tuberculosis, fungal).

The other encouraging statistic is that only 1:4,000 adrenal incidentalomas are malignant. Examples of malignant adrenal masses are: adrenocortical carcinoma, metastatic neoplasm, lymphoma, and malignant pheochromocytoma.

Q: Does adrenal adenoma size matter?

Yes, the larger the size of the adenoma, the higher the association with malignancy. The guide below (based on CT findings) shows not only malignancy potential as it relates to size, but also the importance of Hounsfield units and when surgical intervention is recommended.

Imaging (CT scan)

< 4 cm: homogeneous mass with smooth borders and < 10 Hounsfield units; suggests benign mass (likelihood of malignancy, about 2%)

4 to 6 cm: follow closely, consider surgery (likelihood of malignancy, about 6%)

> 6 cm: surgery indicated (likelihood of malignancy, about 25%)

Some providers and patients inquire whether it is helpful or necessary to biopsy. It is generally not advisable to biopsy, especially if the findings are favorable for benign nonsecretory masses, since there is a high false-negative rate. An indication for biopsy is if the patient has a history of extra-adrenal malignancy; this will distinguish recurrence or metastatic disease from a benign mass. A final proviso: If biopsy is performed, make sure the adrenal mass is not a pheochromocytoma, as biopsy of a hormone-secreting neoplasm can lead to a hypertensive emergency.

Q: How do I determine whether the mass is hormone-secreting?

Although 80% are nonsecretory, you must still maintain a high index of suspicion so as not to miss a potentially problematic and fully treatable adenoma. A thorough history is essential in screening for hormonal excess arising from adrenal adenomas, since the signs and symptoms can be insidious. The three hormones secreted by adrenal adenomas are cortisol, aldosterone, and catecholamines (seen in Cushing syndrome, aldosterone-producing adenoma [APA], and pheochromocytoma, respectively).

It is important to note that Cushing syndrome has an insidious onset and can be easily missed. Hyperaldosteronism presents with hypertension (requiring several medications) and commonly hypokalemia. And pheochromocytoma can be “written off as” anxiety disorder, panic attack, or even hypoglycemia symptoms (especially if patients are treated for diabetes with agents that cause hypoglycemia). To help in your differential diagnosis of secretory adenomas, know that APA accounts for only 1%, and therefore the majority will secrete cortisol and (far less likely) catecholamines.

Q: What is the appropriate laboratory work-up?

The best simple screening test for hypercortisolemia is a 1-mg overnight dexamethasone suppression test. If this value is increased to ≥ 3 µg/dL, it should be followed up with a more sensitive test (a 24-hour urine for creatinine and free cortisol) to further assess for hypercortisolemia.

Patients thought to have a potential pheochromocytoma should undergo measurement of plasma fractionated metanephrines and normetanephrines or 24-hour urine for total metanephrines and fractionated catecholamines.

Finally, for patients with hypokalemia and hypertension or refractory hypertension requiring multiple (> 3) antihypertensive medications, plasma renin activity (PRA) and plasma aldosterone concentration (PAC) should be obtained. A low PRA and a PAC > 15 ng/dL, along with a PAC/PRA ratio of > 20, is highly suggestive of an APA.

Q: What is the treatment and follow-up?

Here is a quick reference guide regarding surgical treatment and medical follow-up and surveillance:

• Adrenalectomy (pheochromocytoma, APA, Cushing syndrome): for masses 4 to 6 cm, consider surgery, especially if > 10 Hounsfield units; for masses > 6 cm, there is an increased risk for malignancy and surgery is required.

• Follow-up for low-suspicion, nonsecretory masses: abdominal CT 3 to 6 months after the initial scan, then annually for 1 to 2 years; hormonal evaluation and follow-up annually for 5 years, to evaluate for signs and symptoms of hormonal excess.

SUGGESTED READING

American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists/American Association of Endocrine Surgeons Medical Guidelines for the Management of Adrenal Incidentalomas. Endocr Pract. 2009;15(Suppl 1).

Management of the Clinically Inapparent Adrenal Mass (Incidentaloma). NIH State-of-the-Science Conference Statement; February 4-6, 2002.

Slawik M, Reincke M. Adrenal incidentalomas (Chapter 20). EndoText.com. www.endotext.org/adrenal/adrenal20/adrenal20.htm. Accessed October 12, 2012.

Fitzgerald PA, Goldfien A. Adrenal medulla. In: Greenspan F, Gardner D, eds. Basic and Clinical Endocrinology. 7th ed. McGraw-Hill: 2003;453-473.

The Washington Manual Endocrinology Specialty Consult. 2005;57-61, 71-84.

Endocrine Secrets. 4th ed. 2005;197-204, 241-252, 257-265.

Cleveland Clinic Endocrine & Metabolism Board Review. www.clevelandclinicmeded.com/live/courses/ann/endoreview/default.asp. Accessed October 12, 2012.

Therapeutic Lifestyle Changes

Q: Why aren’t we promoting therapeutic lifestyle changes (TLCs) as a “true” therapeutic option for our patients with type 2 diabetes?

From a clinician’s perspective, here are three actual cases:

1. A 47-year-old man presents to our endocrine practice with type 2 diabetes (T2DM) diagnosed three years ago by his primary care provider (PCP). He is being treated with metformin ER (500 mg bid), and glimepiride (4 mg/d), and his A1C is 8.2%. He has a BMI of 37 kg/m2, and since starting treatment for his diabetes he has not made any changes in his diet and does not exercise. His PCP informed him that he needs to start insulin right away since none of the remaining noninsulin options has the efficacy to lower his A1C to 6.5% (–1.7%).

2. A 53-year-old woman is referred to our endocrine practice with a new diagnosis of T2DM, made two weeks ago during a routine health maintenance exam. Since her A1C is 9.6%, her PCP told her she needed to start metformin plus insulin or a GLP-1 receptor agonist right away. Dietary note: The patient has drunk four to five (12-oz) cans of regular cola daily for the past two years and states, “I’ve never been an exerciser.”

3. A 44-year-old patient has a new diagnosis of T2DM and A1C of 7.4%. Patient was started on metformin (500 mg bid) before any TLCs were implemented.

In each case, the plan suggested by the PCP is an acceptable option based on current diabetes consensus algorithms. However, one problem I encounter time and time again is that TLCs have not been adequately discussed with the patients as a viable option. It is important to remember that patients with a recent diagnosis of T2DM who are drug naive will have the best glucose-lowering response to oral diabetes medications. Therefore, you will likely observe the highest A1C reductions compared with the average expected reductions in patients who are already taking other diabetes medications.

My experience has been that most PCPs—and even endocrinologists—will start metformin or other diabetes drugs as an initial medication and spend little time on promoting TLCs. I’m uncertain if it’s appointment time constraints, experience, or lack of belief that TLCs will actually be undertaken and continued by the patients. Patients often ask me why other health care providers didn’t enthusiastically promote changes in diet and exercise as a viable treatment option to improve glycemic control. It is not unusual to see patients decrease their A1C value by > 1.0%—and even experience hypoglycemia—on their current diabetes medications when carbohydrates and refined sugars are decreased and light-to-moderate exercise five to seven days per week is instituted.

Remember that the first-line therapy for hypertension, dyslipidemia, prediabetes, and T2DM is lifestyle modification. This first-line approach is all too often the last thing emphasized—or at least it receives little attention.

Q: Are we communicating to patients that TLCs actually have little value and we don’t think they have the ability to make necessary changes?

It seems to be the norm for many providers to evade this sometimes time-consuming yet underrated therapeutic discussion. It is as if we are convinced that the patients won’t make TLCs, so why spend the time discussing them? We essentially discount the patient’s willingness to change, and we default to the quick-and-easy “write a prescription,” since we have scientific studies that support the efficacy of current medications.

Instead, I say, we should be creating a sense of support, empowerment, credibility for change, and an opportunity for a victorious attitude in the patient, not one of failure. If you don’t spend valuable time discussing TLCs and the benefits they have on hypertension, dyslipidemia, and diabetes, then who will? I advise creating a referral list of those professionals who specialize in areas of TLCs, including certified diabetes educators, registered dieticians, behavioral health specialists, and certified personal trainers and fitness consultants.

T2DM is a progressive disease requiring additional medications over time, with the ultimate need for insulin. We should be cautious in how we use this information, as it may frustrate patients and make them feel, “Why should I try since it will not make any difference in the end?” The fact is that the progression of the disease can be altered with diet, exercise, and weight loss in such a fashion that some patients will be able to decrease their current diabetes medications and possibly even discontinue some, including insulin. Keep in mind that this will depend on the number of years they have had T2DM (ie, reflecting their insulin reserves).

I always ask patients what they are willing to do and how soon they plan to commit to these changes. I inform them that I will add and/or change medication(s) as needed based on what they are not willing to do with regard to lifestyle modification. I tell them that immediate changes in diet aimed to nearly eliminate simple sugars and reduce refined or “white foods” (white bread/pasta/potatoes/flour), in addition to establishing regular exercise, will have immediate impact on lowering blood sugars. Weight loss is not required for immediate improvements in blood sugars, but instead will have lasting benefits with as little as a 5% to 10% loss.

Q: If the Diabetes Prevention Program demonstrated such amazing results in the prediabetes population, shouldn’t we surmise that these same results could be applied to the T2DM population?