User login

Standardized Orders Improve Pediatric Care

For many years physicians have created and used various standardized order forms for patient hospital admissions. The increasing popularity of electronic medical records and forms has led to the use of computerized physician order entry (CPOE) as a means of reducing medication errors.13 Crowley et al.,4 Stucky,5 and Garg et al.,6 along with various committees, have recommended standardized order sets and CPOE as a strategy for reducing medication errors. However, implementation of CPOE systems is expensive and not available in most hospitals. According to a recent survey of hospitals in the US, CPOE was only available to physicians at 16% of the participating institutions.7 Until CPOE becomes widespread, standardized preprinted formatted order sets may serve as an inexpensive alternative.

There is anecdotal evidence that standardized admission order forms may improve quality of care and efficiency, and decrease provider variation.8 However, few rigorous studies exist in the pediatric research literature regarding their ability to actually improve patient care.

In 2005, our institution, a large tertiary‐care academic teaching hospital, developed a standardized preprinted pediatric admission order set (PAOS). We did so for 3 reasons. First, there was a desire to improve completeness of orders. Handwritten orders often missed important elements such as weight, allergies, vital sign parameters, activity, etc. Second, there was a need to save time and improve efficiency. Third, it was important to reduce medical errors and the number of clarification requests by decreasing the necessity to decipher physician handwriting. Our PAOS was a convenience order set as opposed to a best practices order set. In other words, our PAOS did not contain evidence‐based management guidelines or protocols for specific admission diagnoses and was created solely to improve the quality and efficiency of workflow.

Documenting improvement in patient outcomes or reduction of medical errors is ultimately needed to establish the effectiveness of a standardized order set. Secondary outcomes, howeverparticularly the perceptions of the staff who are asked to use the order setare equally important, because they may identify real‐life barriers to use that, regardless of effectiveness, could limit dissemination and uptake. With respect to perceptions, 2 groups become paramount: those who write the orders, and those who respond to them. The purpose of the current study was to examine perceived effects of the new PAOS on inpatient care among those who, in our institution, write the ordersresident physicians.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

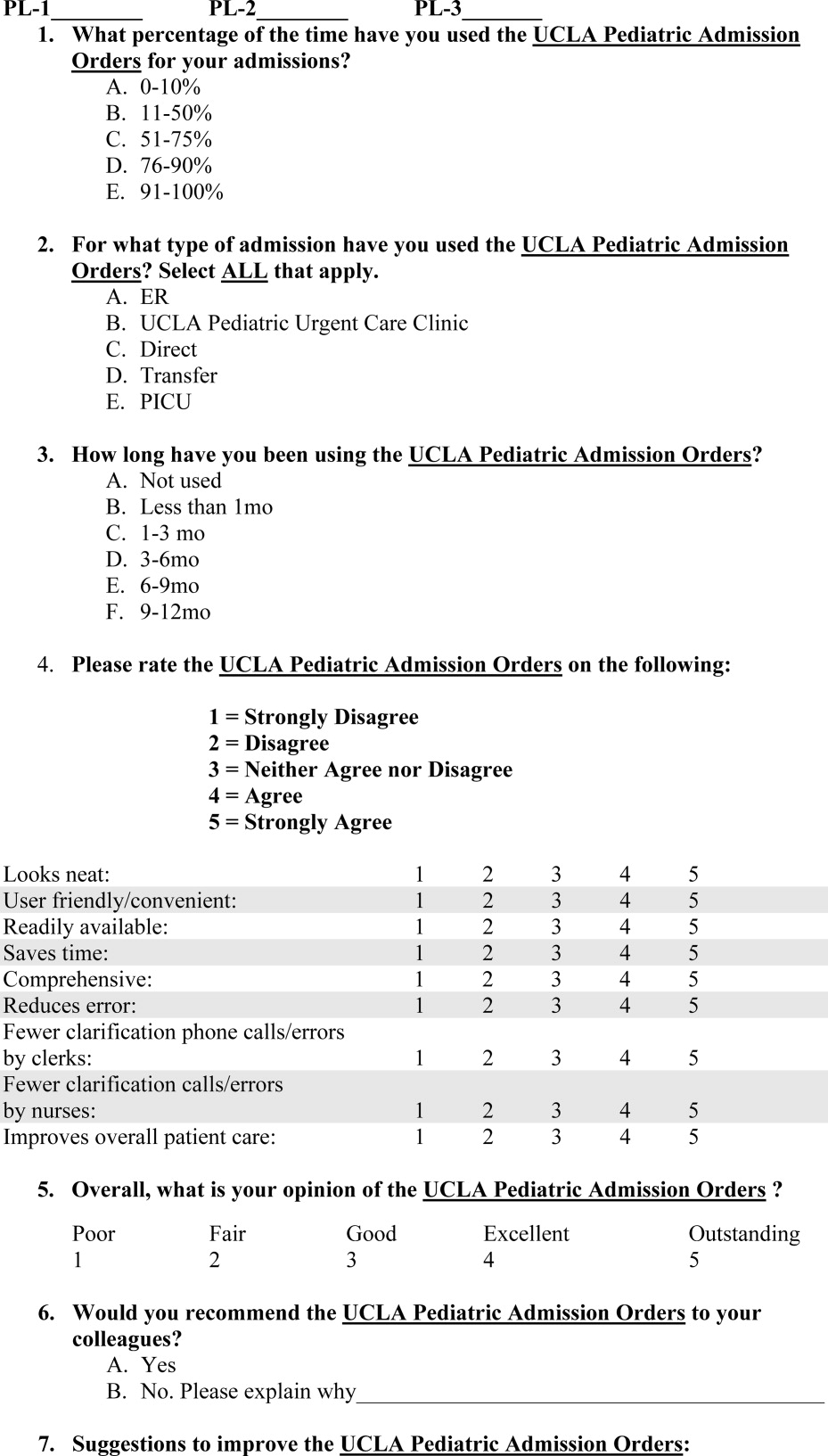

The PAOS was created in August 2005 at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Medical Center by a committee comprising pediatric hospitalists, nurses, pharmacists, residents, and clerks. The PAOS consisted mainly of check boxes (Figure 1). The PAOS was uploaded to the hospital website and made available for printing from all computers in the hospital, emergency room, and clinics.

The UCLA Hospital and Medical Center is a nonprofit, 667‐bed tertiary‐care teaching hospital in Los Angeles, California. The pediatric ward has 70 licensed beds with approximately 3,000 admissions per year. The majority of the admissions were done by the pediatric residents. Physicians were free to edit the PAOS to suit a particular patient's needs or to hand‐write orders on a blank order form.

Measures

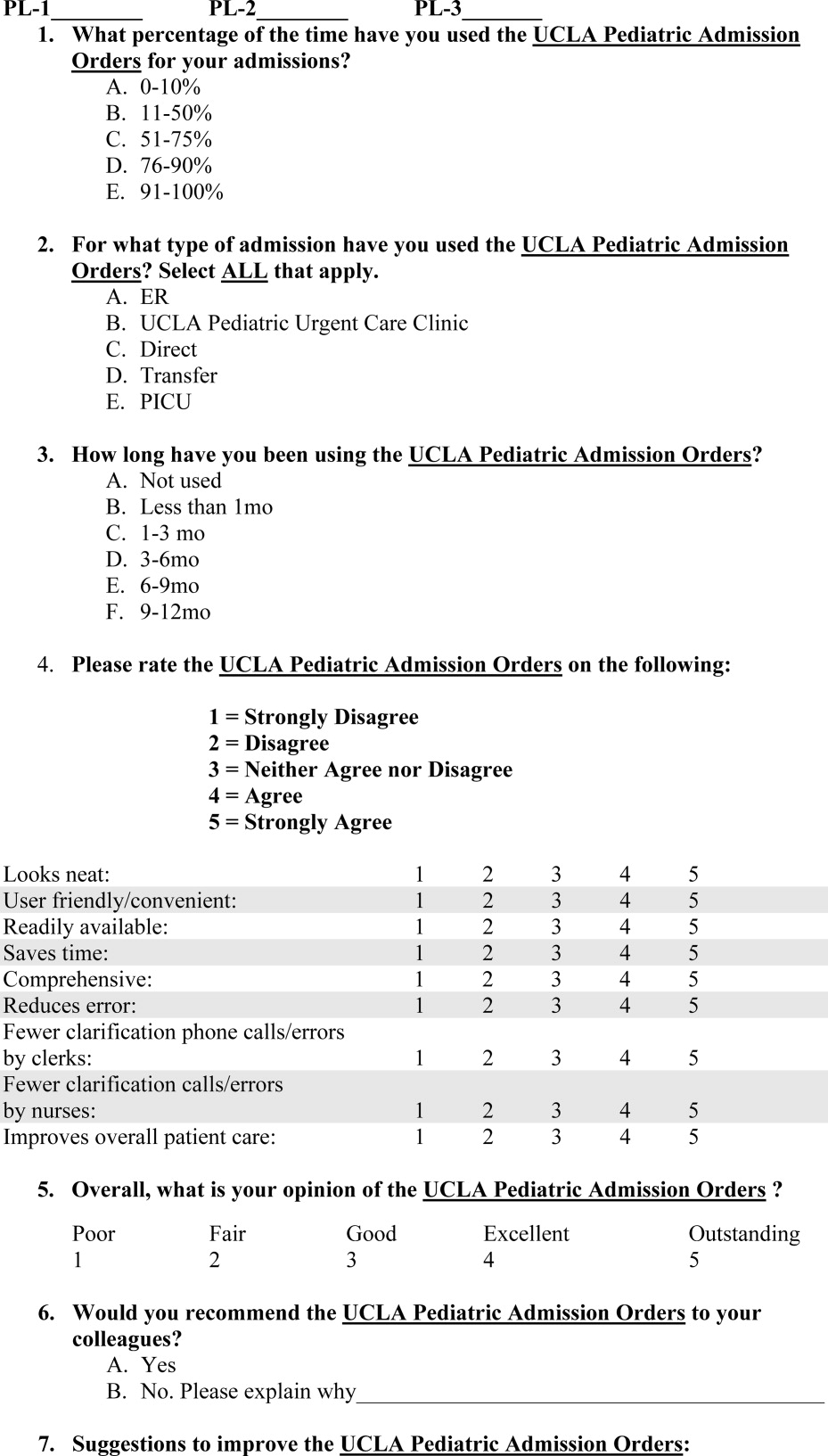

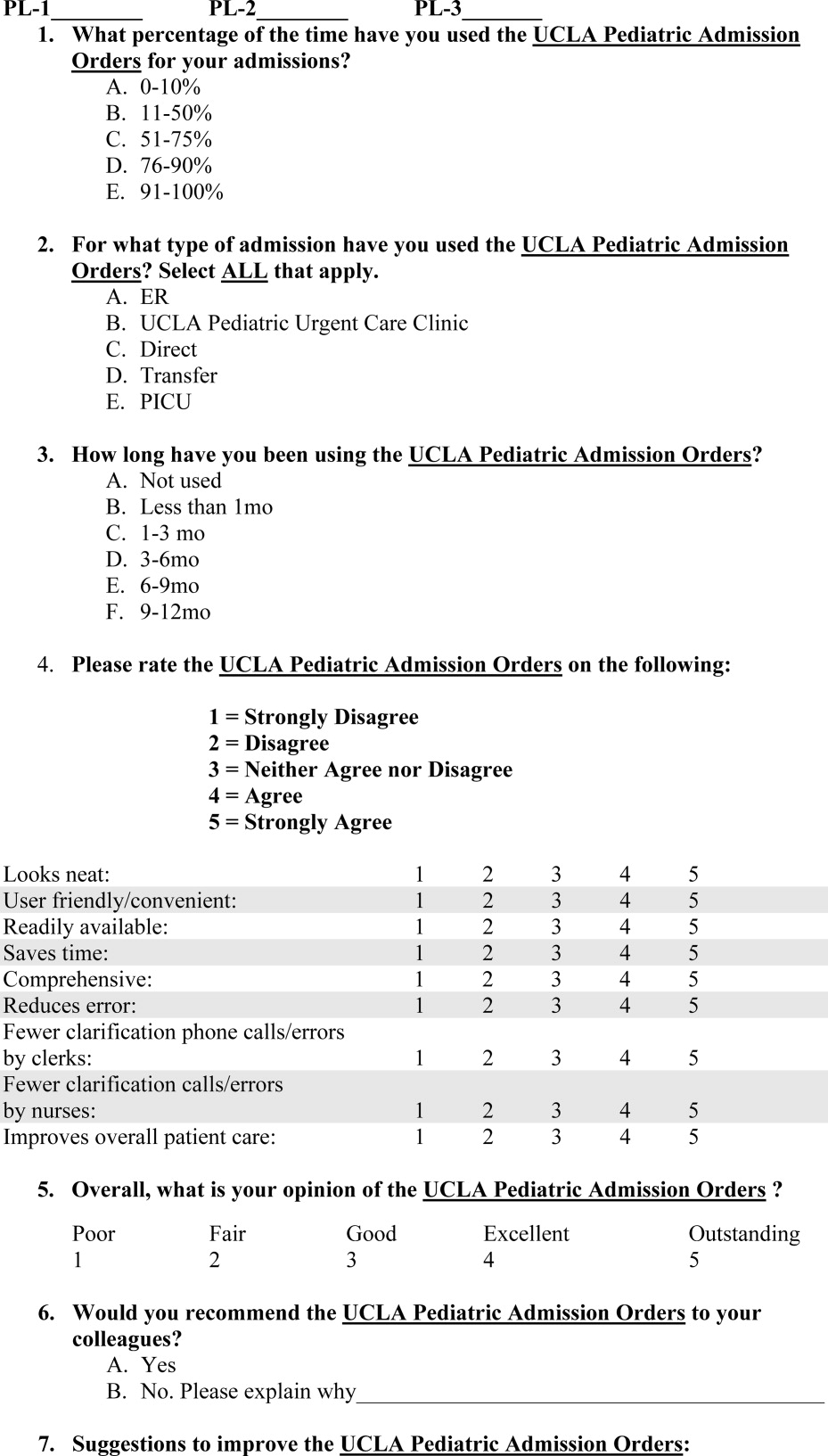

Fourteen months after the institution of the PAOS, all 97 UCLA pediatric residents (PL‐1, n = 34; PL‐2, n = 33; PL‐3, n = 30) were asked to complete a survey to anonymously evaluate the order set. All residents were US medical school graduates. Resident participation in the research project was voluntary and confidential, and residents were assured that participation would not affect their standing in the pediatric residency program. Each resident completed only 1 survey. Responses were collected October 2006 to June 2007. The residents were asked to rate the PAOS overall and with respect to 9 specific dimensions using a 5‐point Likert scale with 1 indicating strong disagreement and 5 indicating strong agreement (Figure 2).

This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at the UCLA Medical Center.

Statistical Analysis

We used bivariate ordered logistic regression to estimate the association between overall rating and each of the 9 dimensions. Ordered logistic regression, a standard technique for ordered categorical variables, is essentially a weighted average of logistic regressions performed at each potential cut‐point of the outcome variable. For instance, potential cut‐points on our 5‐point Likert scale included strong disagreement versus any other, any disagreement versus nondisagreement, any agreement versus nonagreement, and strong agreement versus any other. We then used multivariate ordered logistic regression to examine which specific dimensions remained independently associated with the overall rating.

RESULTS

From October 2006 to June 2007, 59 residents (from a total of 97 residents; 61%) responded to the survey. Overall, 89% of respondents approved of the PAOS, 58% reported using it 90% of the time, and all said that they would recommend it to their colleagues (Table 1). Eighty‐four percent thought that the PAOS improved inpatient care, and 75% thought that medical errors were reduced. Eighty‐eight percent reported that the POAS saved time; 93% said it was convenient; and most reported less need for clarification with clerks (81%) and nurses (82%).

| Strongly Agree (%) | Agree (%) | Other (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific dimensions | |||

| Looks neat | 63 | 32 | 5 |

| User friendly/convenient | 60 | 33 | 7 |

| Readily available | 47 | 26 | 26 |

| Saves time | 56 | 32 | 12 |

| Comprehensive | 40 | 40 | 19 |

| Reduces medical error | 40 | 35 | 25 |

| Fewer clarification phone calls/errors by clerks | 47 | 33 | 19 |

| Fewer clarification phone calls/errors by nurses | 47 | 35 | 18 |

| Improves overall patient care | 46 | 39 | 16 |

| Overall rating | 40 | 49 | 11 |

In bivariate analyses, each of the 9 dimensions was strongly associated with the overall rating (P < 0.001 for each). In multivariate analyses, however, only perceived improvement in patient care was independently associated with overall rating (OR, 3.9; P = 0.04).

We then examined whether perceived improvement in patient care itself was independently predicted by the other 8 dimensions. Residents who said that the form was comprehensive (OR, 5.6; P = 0.01), reduced medical errors (OR, 4.1; P = 0.01), or required less need for clarification with nurses (OR, 9.6; P = 0.01) were more likely to perceive that the form improved patient care than residents who did not.

DISCUSSION

A standardized admission order set is a simple, low‐cost intervention that may benefit patients by reducing medical errors and expediting high‐quality care. In general, residents rated the PAOS favorably. Just as importantly, the PAOS scored well across all specific dimensions, which suggests few perceived barriers to use among residents.

Some dimensions, however, appeared potentially more important than others. Residents who perceived an improvement in patient care tended to rate the PAOS favorably. Perceived improvement in patient care, in turn, was linked to the order set's comprehensiveness, perceived reductions in medical errors, and less need for clarification with nurses.

Even though this study did not directly query those most responsible for responding to the order set (ie, nurses, pharmacists, and clerks), the order set was created through a collaborative partnership of physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and clerks. It is reasonable to infer that resident‐perceived reduction in the need for clarification of orders with nurses and clerks might indicate a broad‐based, multidisciplinary improvement in clarity and workflow. Moreover, the fact that less need for clarification with nurses was strongly associated with resident‐perceived improvement in patient care underscores the importance of including nurses, pharmacists, and clerks in the development of these order sets.

Our experience using the standard admission orders over the past 2 years is congruent with other authors' findings. Most studies, however, have examined standardized order forms only in adult populations, and mainly for specific medical conditions. Micek et al.9 demonstrated that use of a standardized physician order set among adults with septic shock lowered 28‐day mortality and reduced hospital stay. Among stroke patients, rates of optimal treatment significantly improved after the introduction of standardized stroke orders.10 For patients with acute myocardial infarction, standardized admission orders increased early administration of aspirin and beta blockers.11, 12 With respect to cancer, implementation of a preprinted chemotherapy prescription form improved order completeness, prevented medication errors, and reduced time spent by pharmacists clarifying orders.13 Finally, standardized trauma admission orders developed in a surgical‐trauma intensive care unit reduced admission laboratory charges and improved order completeness.14 We found only a single pediatric study examining standardized order forms. Kozer et al.15 found that the use of a preprinted structured medication order form cut medication errors nearly in half in a pediatric emergency department.

Whether our results would have been similar had we implemented a series of best practices order sets rather than a single convenience order set is unclear. Although best practices order sets would have facilitated application of evidence‐based guidelines for common diagnoses, they would also have introduced potentially unwelcome logistical heterogeneity (with a separate form and protocol needed for each diagnosis) that might have reduced acceptability and uptake. In addition, there is a risk that best practices order sets would have been perceived as unduly limiting physician professional autonomy.

Our study has limitations. First, our study was performed within a single institution and may not be easily generalized. However, we believe that the basic format of the PAOS lends it to easy adaptability. Second, we did not survey residents before the order set was introduced to assess baseline perceptions. Instead, many of the questions in the survey ask about perceived improvements compared with the previous system. Conducting a formal pre‐post data collection and analysis might have yielded different results. Third, improvement in patient care was measured indirectly based on resident opinion.

In conclusion, our study suggests that our standardized admission order set prompting physicians to initiate comprehensive care is well‐liked by residents and is thought to benefit patients by reducing medical errors and expediting high‐quality care. The next step is to confirm that the resident‐perceived improvement in patient care correlates with actual improvement in patient care. If improvements can be confirmed, then PAOS adoption could be broadly recommended to pediatric hospitals. In the future, the PAOS may also help guide computerized physician order entry templates that can be further tailored to specific common diagnoses.

- ,,, et al.Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors.JAMA.1998;280(15):1311–1316.

- ,,.Effects of computerized physician order entry and clinical decision support systems on medication safety: a systematic review.Arch Intern Med.2003;163(12):1409–1416.

- ,,,,.The effect of computerized physician order entry on medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients.Pediatrics.2003;112(3 Pt 1):506–509.

- ,,.Medication errors in children: a descriptive summary of medication error reports submitted to the United States Pharmacopoeia.Curr Ther Res Clin Exp.2001;62:627–640.

- .Prevention of medication errors in the pediatric inpatient setting.Pediatrics.2003;112(2):431–436.

- ,,, et al.Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review.JAMA.2005;293(10):1223–1238.

- ,,,.Computerized physician order entry in U.S. hospitals: results of a 2002 survey.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2004;11(2):95–99.

- .Using standardized admit orders to improve inpatient care.Fam Pract Manag.1999;6(10):30–32.

- ,,, et al.Before‐after study of a standardized hospital order set for the management of septic shock.Crit Care Med.2006;34(11):2707–2713.

- California Acute Stroke Pilot Registry Investigators.The impact of standardized stroke orders on adherence to best practices.Neurology.2005;65(3):360–365.

- ,,,,,.Improving quality of care for acute myocardial infarction. The guidelines applied in practice (GAP) initiative.JAMA.2002;287(10):1269–1276.

- ,,,,,.Quality improvement initiative and its impact on the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction.Arch Intern Med.2000;160:3057–3061.

- ,,,,,.Effect of a cancer chemotherapy prescription form on prescription completeness.Am J Hosp Pharm.1989;46(9):1802–1806.

- ,.Standardized trauma admission orders, a pilot project.Int J Trauma Nurs.1996;2(1):13–21.

- ,,,,.Using a preprinted order sheet to reduce prescription errors in a pediatric emergency department: a randomized, controlled trial.Pediatrics.2005;116(6):1299–1302.

For many years physicians have created and used various standardized order forms for patient hospital admissions. The increasing popularity of electronic medical records and forms has led to the use of computerized physician order entry (CPOE) as a means of reducing medication errors.13 Crowley et al.,4 Stucky,5 and Garg et al.,6 along with various committees, have recommended standardized order sets and CPOE as a strategy for reducing medication errors. However, implementation of CPOE systems is expensive and not available in most hospitals. According to a recent survey of hospitals in the US, CPOE was only available to physicians at 16% of the participating institutions.7 Until CPOE becomes widespread, standardized preprinted formatted order sets may serve as an inexpensive alternative.

There is anecdotal evidence that standardized admission order forms may improve quality of care and efficiency, and decrease provider variation.8 However, few rigorous studies exist in the pediatric research literature regarding their ability to actually improve patient care.

In 2005, our institution, a large tertiary‐care academic teaching hospital, developed a standardized preprinted pediatric admission order set (PAOS). We did so for 3 reasons. First, there was a desire to improve completeness of orders. Handwritten orders often missed important elements such as weight, allergies, vital sign parameters, activity, etc. Second, there was a need to save time and improve efficiency. Third, it was important to reduce medical errors and the number of clarification requests by decreasing the necessity to decipher physician handwriting. Our PAOS was a convenience order set as opposed to a best practices order set. In other words, our PAOS did not contain evidence‐based management guidelines or protocols for specific admission diagnoses and was created solely to improve the quality and efficiency of workflow.

Documenting improvement in patient outcomes or reduction of medical errors is ultimately needed to establish the effectiveness of a standardized order set. Secondary outcomes, howeverparticularly the perceptions of the staff who are asked to use the order setare equally important, because they may identify real‐life barriers to use that, regardless of effectiveness, could limit dissemination and uptake. With respect to perceptions, 2 groups become paramount: those who write the orders, and those who respond to them. The purpose of the current study was to examine perceived effects of the new PAOS on inpatient care among those who, in our institution, write the ordersresident physicians.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The PAOS was created in August 2005 at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Medical Center by a committee comprising pediatric hospitalists, nurses, pharmacists, residents, and clerks. The PAOS consisted mainly of check boxes (Figure 1). The PAOS was uploaded to the hospital website and made available for printing from all computers in the hospital, emergency room, and clinics.

The UCLA Hospital and Medical Center is a nonprofit, 667‐bed tertiary‐care teaching hospital in Los Angeles, California. The pediatric ward has 70 licensed beds with approximately 3,000 admissions per year. The majority of the admissions were done by the pediatric residents. Physicians were free to edit the PAOS to suit a particular patient's needs or to hand‐write orders on a blank order form.

Measures

Fourteen months after the institution of the PAOS, all 97 UCLA pediatric residents (PL‐1, n = 34; PL‐2, n = 33; PL‐3, n = 30) were asked to complete a survey to anonymously evaluate the order set. All residents were US medical school graduates. Resident participation in the research project was voluntary and confidential, and residents were assured that participation would not affect their standing in the pediatric residency program. Each resident completed only 1 survey. Responses were collected October 2006 to June 2007. The residents were asked to rate the PAOS overall and with respect to 9 specific dimensions using a 5‐point Likert scale with 1 indicating strong disagreement and 5 indicating strong agreement (Figure 2).

This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at the UCLA Medical Center.

Statistical Analysis

We used bivariate ordered logistic regression to estimate the association between overall rating and each of the 9 dimensions. Ordered logistic regression, a standard technique for ordered categorical variables, is essentially a weighted average of logistic regressions performed at each potential cut‐point of the outcome variable. For instance, potential cut‐points on our 5‐point Likert scale included strong disagreement versus any other, any disagreement versus nondisagreement, any agreement versus nonagreement, and strong agreement versus any other. We then used multivariate ordered logistic regression to examine which specific dimensions remained independently associated with the overall rating.

RESULTS

From October 2006 to June 2007, 59 residents (from a total of 97 residents; 61%) responded to the survey. Overall, 89% of respondents approved of the PAOS, 58% reported using it 90% of the time, and all said that they would recommend it to their colleagues (Table 1). Eighty‐four percent thought that the PAOS improved inpatient care, and 75% thought that medical errors were reduced. Eighty‐eight percent reported that the POAS saved time; 93% said it was convenient; and most reported less need for clarification with clerks (81%) and nurses (82%).

| Strongly Agree (%) | Agree (%) | Other (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific dimensions | |||

| Looks neat | 63 | 32 | 5 |

| User friendly/convenient | 60 | 33 | 7 |

| Readily available | 47 | 26 | 26 |

| Saves time | 56 | 32 | 12 |

| Comprehensive | 40 | 40 | 19 |

| Reduces medical error | 40 | 35 | 25 |

| Fewer clarification phone calls/errors by clerks | 47 | 33 | 19 |

| Fewer clarification phone calls/errors by nurses | 47 | 35 | 18 |

| Improves overall patient care | 46 | 39 | 16 |

| Overall rating | 40 | 49 | 11 |

In bivariate analyses, each of the 9 dimensions was strongly associated with the overall rating (P < 0.001 for each). In multivariate analyses, however, only perceived improvement in patient care was independently associated with overall rating (OR, 3.9; P = 0.04).

We then examined whether perceived improvement in patient care itself was independently predicted by the other 8 dimensions. Residents who said that the form was comprehensive (OR, 5.6; P = 0.01), reduced medical errors (OR, 4.1; P = 0.01), or required less need for clarification with nurses (OR, 9.6; P = 0.01) were more likely to perceive that the form improved patient care than residents who did not.

DISCUSSION

A standardized admission order set is a simple, low‐cost intervention that may benefit patients by reducing medical errors and expediting high‐quality care. In general, residents rated the PAOS favorably. Just as importantly, the PAOS scored well across all specific dimensions, which suggests few perceived barriers to use among residents.

Some dimensions, however, appeared potentially more important than others. Residents who perceived an improvement in patient care tended to rate the PAOS favorably. Perceived improvement in patient care, in turn, was linked to the order set's comprehensiveness, perceived reductions in medical errors, and less need for clarification with nurses.

Even though this study did not directly query those most responsible for responding to the order set (ie, nurses, pharmacists, and clerks), the order set was created through a collaborative partnership of physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and clerks. It is reasonable to infer that resident‐perceived reduction in the need for clarification of orders with nurses and clerks might indicate a broad‐based, multidisciplinary improvement in clarity and workflow. Moreover, the fact that less need for clarification with nurses was strongly associated with resident‐perceived improvement in patient care underscores the importance of including nurses, pharmacists, and clerks in the development of these order sets.

Our experience using the standard admission orders over the past 2 years is congruent with other authors' findings. Most studies, however, have examined standardized order forms only in adult populations, and mainly for specific medical conditions. Micek et al.9 demonstrated that use of a standardized physician order set among adults with septic shock lowered 28‐day mortality and reduced hospital stay. Among stroke patients, rates of optimal treatment significantly improved after the introduction of standardized stroke orders.10 For patients with acute myocardial infarction, standardized admission orders increased early administration of aspirin and beta blockers.11, 12 With respect to cancer, implementation of a preprinted chemotherapy prescription form improved order completeness, prevented medication errors, and reduced time spent by pharmacists clarifying orders.13 Finally, standardized trauma admission orders developed in a surgical‐trauma intensive care unit reduced admission laboratory charges and improved order completeness.14 We found only a single pediatric study examining standardized order forms. Kozer et al.15 found that the use of a preprinted structured medication order form cut medication errors nearly in half in a pediatric emergency department.

Whether our results would have been similar had we implemented a series of best practices order sets rather than a single convenience order set is unclear. Although best practices order sets would have facilitated application of evidence‐based guidelines for common diagnoses, they would also have introduced potentially unwelcome logistical heterogeneity (with a separate form and protocol needed for each diagnosis) that might have reduced acceptability and uptake. In addition, there is a risk that best practices order sets would have been perceived as unduly limiting physician professional autonomy.

Our study has limitations. First, our study was performed within a single institution and may not be easily generalized. However, we believe that the basic format of the PAOS lends it to easy adaptability. Second, we did not survey residents before the order set was introduced to assess baseline perceptions. Instead, many of the questions in the survey ask about perceived improvements compared with the previous system. Conducting a formal pre‐post data collection and analysis might have yielded different results. Third, improvement in patient care was measured indirectly based on resident opinion.

In conclusion, our study suggests that our standardized admission order set prompting physicians to initiate comprehensive care is well‐liked by residents and is thought to benefit patients by reducing medical errors and expediting high‐quality care. The next step is to confirm that the resident‐perceived improvement in patient care correlates with actual improvement in patient care. If improvements can be confirmed, then PAOS adoption could be broadly recommended to pediatric hospitals. In the future, the PAOS may also help guide computerized physician order entry templates that can be further tailored to specific common diagnoses.

For many years physicians have created and used various standardized order forms for patient hospital admissions. The increasing popularity of electronic medical records and forms has led to the use of computerized physician order entry (CPOE) as a means of reducing medication errors.13 Crowley et al.,4 Stucky,5 and Garg et al.,6 along with various committees, have recommended standardized order sets and CPOE as a strategy for reducing medication errors. However, implementation of CPOE systems is expensive and not available in most hospitals. According to a recent survey of hospitals in the US, CPOE was only available to physicians at 16% of the participating institutions.7 Until CPOE becomes widespread, standardized preprinted formatted order sets may serve as an inexpensive alternative.

There is anecdotal evidence that standardized admission order forms may improve quality of care and efficiency, and decrease provider variation.8 However, few rigorous studies exist in the pediatric research literature regarding their ability to actually improve patient care.

In 2005, our institution, a large tertiary‐care academic teaching hospital, developed a standardized preprinted pediatric admission order set (PAOS). We did so for 3 reasons. First, there was a desire to improve completeness of orders. Handwritten orders often missed important elements such as weight, allergies, vital sign parameters, activity, etc. Second, there was a need to save time and improve efficiency. Third, it was important to reduce medical errors and the number of clarification requests by decreasing the necessity to decipher physician handwriting. Our PAOS was a convenience order set as opposed to a best practices order set. In other words, our PAOS did not contain evidence‐based management guidelines or protocols for specific admission diagnoses and was created solely to improve the quality and efficiency of workflow.

Documenting improvement in patient outcomes or reduction of medical errors is ultimately needed to establish the effectiveness of a standardized order set. Secondary outcomes, howeverparticularly the perceptions of the staff who are asked to use the order setare equally important, because they may identify real‐life barriers to use that, regardless of effectiveness, could limit dissemination and uptake. With respect to perceptions, 2 groups become paramount: those who write the orders, and those who respond to them. The purpose of the current study was to examine perceived effects of the new PAOS on inpatient care among those who, in our institution, write the ordersresident physicians.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The PAOS was created in August 2005 at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) Medical Center by a committee comprising pediatric hospitalists, nurses, pharmacists, residents, and clerks. The PAOS consisted mainly of check boxes (Figure 1). The PAOS was uploaded to the hospital website and made available for printing from all computers in the hospital, emergency room, and clinics.

The UCLA Hospital and Medical Center is a nonprofit, 667‐bed tertiary‐care teaching hospital in Los Angeles, California. The pediatric ward has 70 licensed beds with approximately 3,000 admissions per year. The majority of the admissions were done by the pediatric residents. Physicians were free to edit the PAOS to suit a particular patient's needs or to hand‐write orders on a blank order form.

Measures

Fourteen months after the institution of the PAOS, all 97 UCLA pediatric residents (PL‐1, n = 34; PL‐2, n = 33; PL‐3, n = 30) were asked to complete a survey to anonymously evaluate the order set. All residents were US medical school graduates. Resident participation in the research project was voluntary and confidential, and residents were assured that participation would not affect their standing in the pediatric residency program. Each resident completed only 1 survey. Responses were collected October 2006 to June 2007. The residents were asked to rate the PAOS overall and with respect to 9 specific dimensions using a 5‐point Likert scale with 1 indicating strong disagreement and 5 indicating strong agreement (Figure 2).

This study was reviewed and approved by the institutional review board at the UCLA Medical Center.

Statistical Analysis

We used bivariate ordered logistic regression to estimate the association between overall rating and each of the 9 dimensions. Ordered logistic regression, a standard technique for ordered categorical variables, is essentially a weighted average of logistic regressions performed at each potential cut‐point of the outcome variable. For instance, potential cut‐points on our 5‐point Likert scale included strong disagreement versus any other, any disagreement versus nondisagreement, any agreement versus nonagreement, and strong agreement versus any other. We then used multivariate ordered logistic regression to examine which specific dimensions remained independently associated with the overall rating.

RESULTS

From October 2006 to June 2007, 59 residents (from a total of 97 residents; 61%) responded to the survey. Overall, 89% of respondents approved of the PAOS, 58% reported using it 90% of the time, and all said that they would recommend it to their colleagues (Table 1). Eighty‐four percent thought that the PAOS improved inpatient care, and 75% thought that medical errors were reduced. Eighty‐eight percent reported that the POAS saved time; 93% said it was convenient; and most reported less need for clarification with clerks (81%) and nurses (82%).

| Strongly Agree (%) | Agree (%) | Other (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Specific dimensions | |||

| Looks neat | 63 | 32 | 5 |

| User friendly/convenient | 60 | 33 | 7 |

| Readily available | 47 | 26 | 26 |

| Saves time | 56 | 32 | 12 |

| Comprehensive | 40 | 40 | 19 |

| Reduces medical error | 40 | 35 | 25 |

| Fewer clarification phone calls/errors by clerks | 47 | 33 | 19 |

| Fewer clarification phone calls/errors by nurses | 47 | 35 | 18 |

| Improves overall patient care | 46 | 39 | 16 |

| Overall rating | 40 | 49 | 11 |

In bivariate analyses, each of the 9 dimensions was strongly associated with the overall rating (P < 0.001 for each). In multivariate analyses, however, only perceived improvement in patient care was independently associated with overall rating (OR, 3.9; P = 0.04).

We then examined whether perceived improvement in patient care itself was independently predicted by the other 8 dimensions. Residents who said that the form was comprehensive (OR, 5.6; P = 0.01), reduced medical errors (OR, 4.1; P = 0.01), or required less need for clarification with nurses (OR, 9.6; P = 0.01) were more likely to perceive that the form improved patient care than residents who did not.

DISCUSSION

A standardized admission order set is a simple, low‐cost intervention that may benefit patients by reducing medical errors and expediting high‐quality care. In general, residents rated the PAOS favorably. Just as importantly, the PAOS scored well across all specific dimensions, which suggests few perceived barriers to use among residents.

Some dimensions, however, appeared potentially more important than others. Residents who perceived an improvement in patient care tended to rate the PAOS favorably. Perceived improvement in patient care, in turn, was linked to the order set's comprehensiveness, perceived reductions in medical errors, and less need for clarification with nurses.

Even though this study did not directly query those most responsible for responding to the order set (ie, nurses, pharmacists, and clerks), the order set was created through a collaborative partnership of physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and clerks. It is reasonable to infer that resident‐perceived reduction in the need for clarification of orders with nurses and clerks might indicate a broad‐based, multidisciplinary improvement in clarity and workflow. Moreover, the fact that less need for clarification with nurses was strongly associated with resident‐perceived improvement in patient care underscores the importance of including nurses, pharmacists, and clerks in the development of these order sets.

Our experience using the standard admission orders over the past 2 years is congruent with other authors' findings. Most studies, however, have examined standardized order forms only in adult populations, and mainly for specific medical conditions. Micek et al.9 demonstrated that use of a standardized physician order set among adults with septic shock lowered 28‐day mortality and reduced hospital stay. Among stroke patients, rates of optimal treatment significantly improved after the introduction of standardized stroke orders.10 For patients with acute myocardial infarction, standardized admission orders increased early administration of aspirin and beta blockers.11, 12 With respect to cancer, implementation of a preprinted chemotherapy prescription form improved order completeness, prevented medication errors, and reduced time spent by pharmacists clarifying orders.13 Finally, standardized trauma admission orders developed in a surgical‐trauma intensive care unit reduced admission laboratory charges and improved order completeness.14 We found only a single pediatric study examining standardized order forms. Kozer et al.15 found that the use of a preprinted structured medication order form cut medication errors nearly in half in a pediatric emergency department.

Whether our results would have been similar had we implemented a series of best practices order sets rather than a single convenience order set is unclear. Although best practices order sets would have facilitated application of evidence‐based guidelines for common diagnoses, they would also have introduced potentially unwelcome logistical heterogeneity (with a separate form and protocol needed for each diagnosis) that might have reduced acceptability and uptake. In addition, there is a risk that best practices order sets would have been perceived as unduly limiting physician professional autonomy.

Our study has limitations. First, our study was performed within a single institution and may not be easily generalized. However, we believe that the basic format of the PAOS lends it to easy adaptability. Second, we did not survey residents before the order set was introduced to assess baseline perceptions. Instead, many of the questions in the survey ask about perceived improvements compared with the previous system. Conducting a formal pre‐post data collection and analysis might have yielded different results. Third, improvement in patient care was measured indirectly based on resident opinion.

In conclusion, our study suggests that our standardized admission order set prompting physicians to initiate comprehensive care is well‐liked by residents and is thought to benefit patients by reducing medical errors and expediting high‐quality care. The next step is to confirm that the resident‐perceived improvement in patient care correlates with actual improvement in patient care. If improvements can be confirmed, then PAOS adoption could be broadly recommended to pediatric hospitals. In the future, the PAOS may also help guide computerized physician order entry templates that can be further tailored to specific common diagnoses.

- ,,, et al.Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors.JAMA.1998;280(15):1311–1316.

- ,,.Effects of computerized physician order entry and clinical decision support systems on medication safety: a systematic review.Arch Intern Med.2003;163(12):1409–1416.

- ,,,,.The effect of computerized physician order entry on medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients.Pediatrics.2003;112(3 Pt 1):506–509.

- ,,.Medication errors in children: a descriptive summary of medication error reports submitted to the United States Pharmacopoeia.Curr Ther Res Clin Exp.2001;62:627–640.

- .Prevention of medication errors in the pediatric inpatient setting.Pediatrics.2003;112(2):431–436.

- ,,, et al.Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review.JAMA.2005;293(10):1223–1238.

- ,,,.Computerized physician order entry in U.S. hospitals: results of a 2002 survey.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2004;11(2):95–99.

- .Using standardized admit orders to improve inpatient care.Fam Pract Manag.1999;6(10):30–32.

- ,,, et al.Before‐after study of a standardized hospital order set for the management of septic shock.Crit Care Med.2006;34(11):2707–2713.

- California Acute Stroke Pilot Registry Investigators.The impact of standardized stroke orders on adherence to best practices.Neurology.2005;65(3):360–365.

- ,,,,,.Improving quality of care for acute myocardial infarction. The guidelines applied in practice (GAP) initiative.JAMA.2002;287(10):1269–1276.

- ,,,,,.Quality improvement initiative and its impact on the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction.Arch Intern Med.2000;160:3057–3061.

- ,,,,,.Effect of a cancer chemotherapy prescription form on prescription completeness.Am J Hosp Pharm.1989;46(9):1802–1806.

- ,.Standardized trauma admission orders, a pilot project.Int J Trauma Nurs.1996;2(1):13–21.

- ,,,,.Using a preprinted order sheet to reduce prescription errors in a pediatric emergency department: a randomized, controlled trial.Pediatrics.2005;116(6):1299–1302.

- ,,, et al.Effect of computerized physician order entry and a team intervention on prevention of serious medication errors.JAMA.1998;280(15):1311–1316.

- ,,.Effects of computerized physician order entry and clinical decision support systems on medication safety: a systematic review.Arch Intern Med.2003;163(12):1409–1416.

- ,,,,.The effect of computerized physician order entry on medication errors and adverse drug events in pediatric inpatients.Pediatrics.2003;112(3 Pt 1):506–509.

- ,,.Medication errors in children: a descriptive summary of medication error reports submitted to the United States Pharmacopoeia.Curr Ther Res Clin Exp.2001;62:627–640.

- .Prevention of medication errors in the pediatric inpatient setting.Pediatrics.2003;112(2):431–436.

- ,,, et al.Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes: a systematic review.JAMA.2005;293(10):1223–1238.

- ,,,.Computerized physician order entry in U.S. hospitals: results of a 2002 survey.J Am Med Inform Assoc.2004;11(2):95–99.

- .Using standardized admit orders to improve inpatient care.Fam Pract Manag.1999;6(10):30–32.

- ,,, et al.Before‐after study of a standardized hospital order set for the management of septic shock.Crit Care Med.2006;34(11):2707–2713.

- California Acute Stroke Pilot Registry Investigators.The impact of standardized stroke orders on adherence to best practices.Neurology.2005;65(3):360–365.

- ,,,,,.Improving quality of care for acute myocardial infarction. The guidelines applied in practice (GAP) initiative.JAMA.2002;287(10):1269–1276.

- ,,,,,.Quality improvement initiative and its impact on the management of patients with acute myocardial infarction.Arch Intern Med.2000;160:3057–3061.

- ,,,,,.Effect of a cancer chemotherapy prescription form on prescription completeness.Am J Hosp Pharm.1989;46(9):1802–1806.

- ,.Standardized trauma admission orders, a pilot project.Int J Trauma Nurs.1996;2(1):13–21.

- ,,,,.Using a preprinted order sheet to reduce prescription errors in a pediatric emergency department: a randomized, controlled trial.Pediatrics.2005;116(6):1299–1302.

Copyright © 2009 Society of Hospital Medicine