User login

Essential oils: How safe? How effective?

Essential oils (EOs), which are concentrated plant-based oils, have become ubiquitous over the past decade. Given the far reach of EOs and their longtime use in traditional, complementary, alternative, and integrative medicine, it is imperative that clinicians have some knowledge of the potential benefits, risks, and overall efficacy.

Commonly used for aromatic benefits (aromatherapy), EOs are now also incorporated into a multitude of products promoting health and wellness. EOs are sold as individual products and can be a component in consumer goods such as cosmetics, body care/hygiene/beauty products, laundry detergents, insect repellents, over-the-counter medications, and food.

The review that follows presents the most current evidence available. With that said, it’s important to keep in mind some caveats that relate to this evidence. First, the studies cited tend to have a small sample size. Second, a majority of these studies were conducted in countries where there appears to be a significant culture of EO use, which could contribute to confirmation bias. Finally, in a number of the studies, there is concern for publication bias as well as a discrepancy between calculated statistical significance and actual clinical relevance.

What are essential oils?

EOs generally are made by extracting the oil from leaves, bark, flowers, seeds/fruit, rinds, and/or roots by steaming or pressing parts of a plant. It can take several pounds of plant material to produce a single bottle of EO, which usually contains ≥ 15 to 30 mL (.5 to 1 oz).1

Some commonly used EOs in the United States are lavender, peppermint, rose, clary sage, tea tree, eucalyptus, and citrus; however, there are approximately 300 EOs available.2 EOs are used most often via topical application, inhalation, or ingestion.

As with any botanical agent, EOs are complex substances often containing a multitude of chemical compounds.1 Because of the complex makeup of EOs, which often contain up to 100 volatile organic compounds, and their wide-ranging potential effects, applying the scientific method to study effectiveness poses a challenge that has limited their adoption in evidence-based practice.2

Availability and cost. EOs can be purchased at large retailers (eg, grocery stores, drug stores) and smaller health food stores, as well as on the Internet. Various EO vehicles, such as inhalers and topical creams, also can be purchased at these stores.

Continue to: The cost varies...

The cost varies enormously by manufacturer and type of plant used to make the EO. Common EOs such as peppermint and lavender oil generally cost $10 to $25, while rarer plant oils can cost $80 or more per bottle.

How safe are essential oils?

Patients may assume EOs are harmless because they are derived from natural plants and have been used medicinally for centuries. However, care must be taken with their use.

The safest way to use EOs is topically, although due to their highly concentrated nature, EOs should be diluted in an unscented neutral carrier oil such as coconut, jojoba, olive, or sweet almond.3 Ingestion of certain oils can cause hepatotoxicity, seizures, and even death.3 In fact, patients should speak with a knowledgeable physician before purchasing any oral EO capsules.

Whether used topically or ingested, all EOs carry risk for skin irritation and allergic reactions, and oral ingestion may result in some negative gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects.4 A case report of 3 patients published in 2007 identified the potential for lavender and tea tree EOs to be endocrine disruptors.5

Inhalation of EOs may be harmful, as they emit many volatile organic compounds, some of which are considered potentially hazardous.6 At this time, there is insufficient evidence regarding inhaled EOs and their direct connection to respiratory health. It is reasonable to suggest, however, that the prolonged use of EOs and their use by patients who have lung conditions such as asthma or COPD should be avoided.7

Continue to: How are quality and purity assessed?

How are quality and purity assessed?

Like other dietary supplements, EOs are not regulated. No US regulatory agencies (eg, the US Food and Drug Administration [FDA] or Department of Agriculture [USDA]) certify or approve EOs for quality and purity. Bottles labeled with “QAI” for Quality Assurance International or “USDA Organic” will ensure the plant constituents used in the EO are from organic farming but do not attest to quality or purity.

Manufacturers commonly use marketing terms such as “therapeutic grade” or “pure” to sell products, but again, these terms do not reflect the product’s quality or purity. A labeled single EO may contain contaminants, alcohol, or additional ingredients.7 When choosing to use EOs, identifying reputable brands is essential; one resource is the independent testing organization ConsumerLab.com.

It is important to assess the manufacturer and read ingredient labels before purchasing an EO to understand what the product contains. Reputable companies will identify the plant ingredient, usually by the formal Latin binomial name, and explain the extraction process. A more certain way to assess the quality and purity of an EO is to ask the manufacturer to provide a certificate of analysis and gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy (GC/MS) data for the specific product. Some manufacturers offer GC/MS test results on their website Quality page.8 Others have detailed information on quality and testing, and GC/MS test reports can be obtained.9 Yet another manufacturer has test results on a product page matching reports to batch codes.10

Which conditions have evidence of benefit from essential oils?

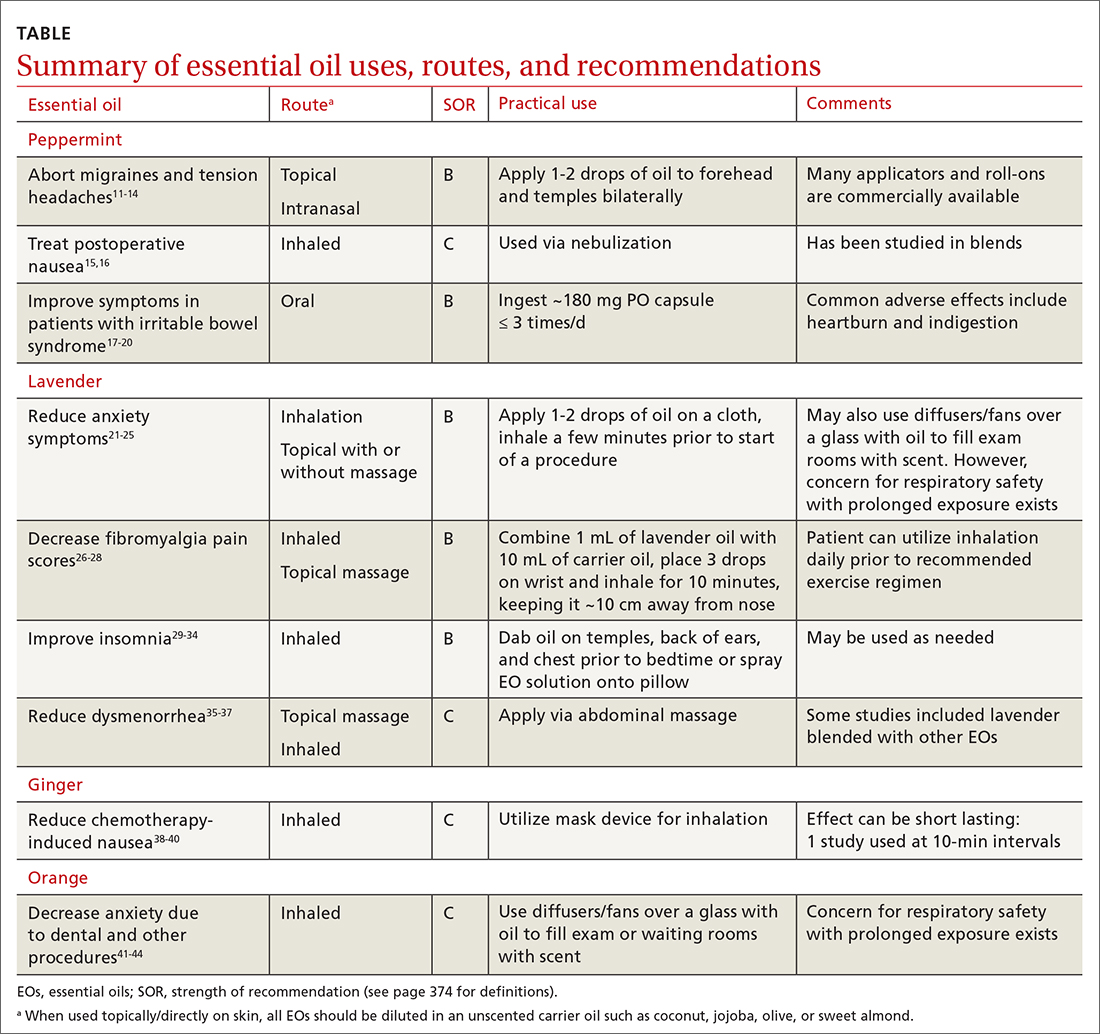

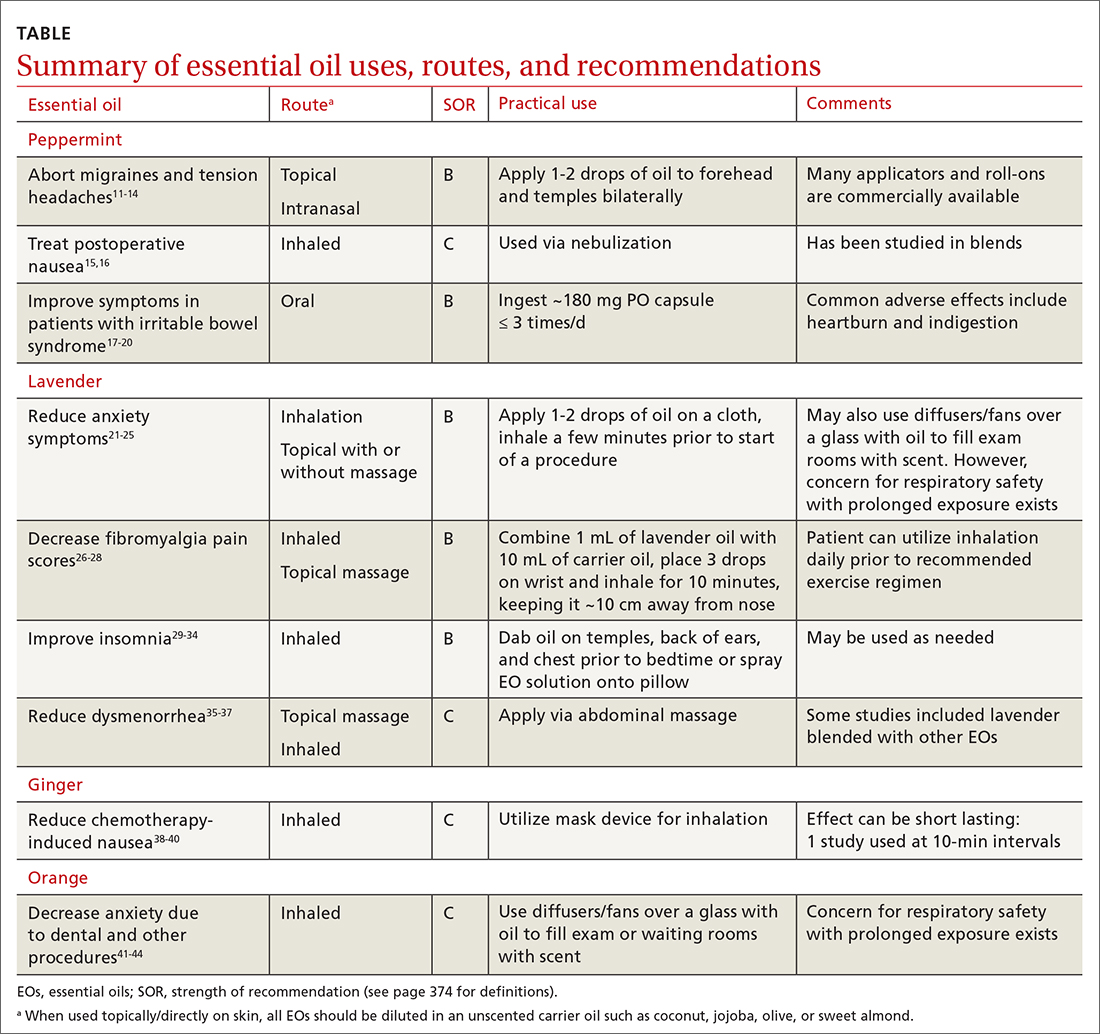

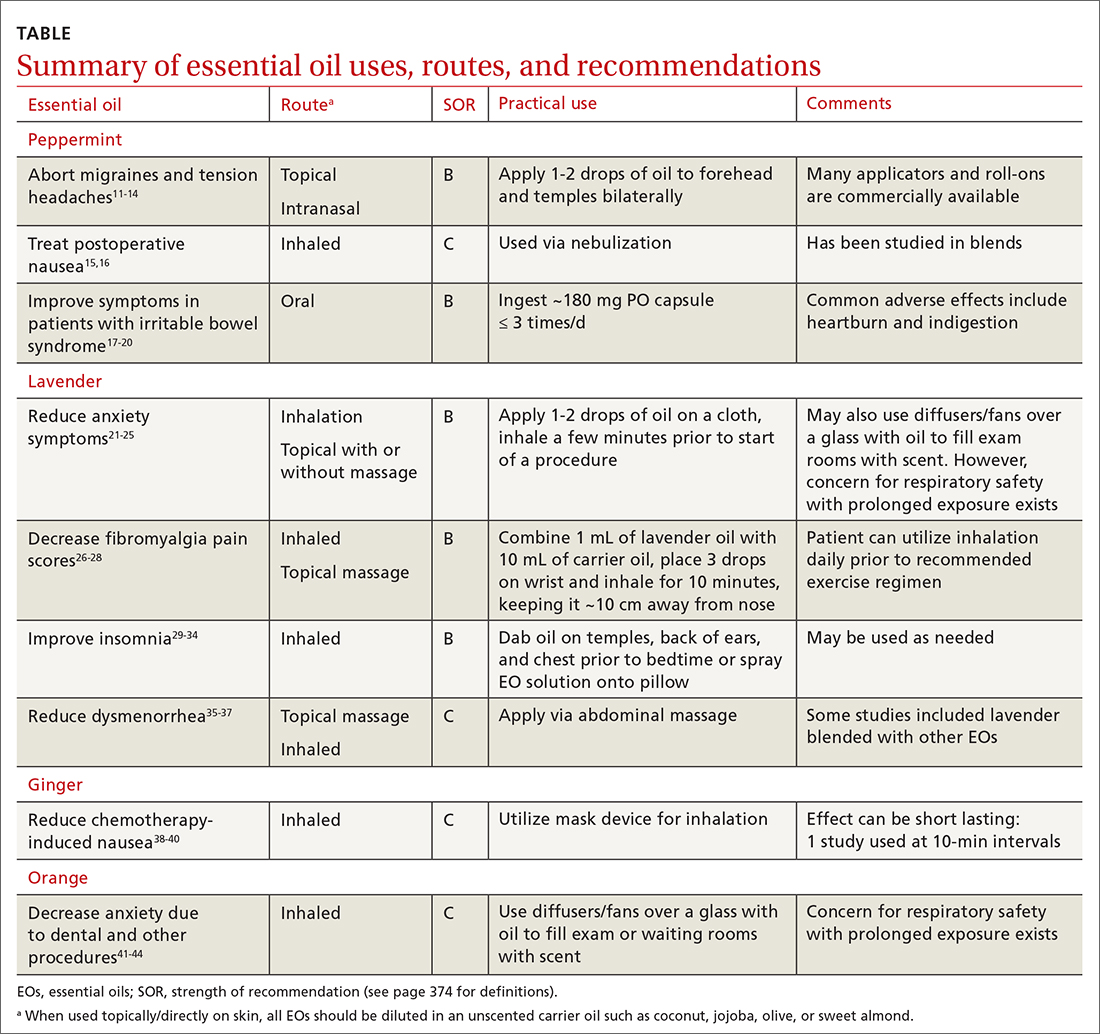

EOs currently are being studied for treatment of many conditions—including pain, GI disorders, behavioral health disorders, and women’s health issues. The TABLE summarizes the conditions treated, outcomes, and practical applications of EOs.11-44

Pain

Headache. As an adjunct to available medications and procedures for headache treatment, EOs are one of the nonpharmacologic modalities that patients and clinicians have at their disposal for both migraine and tension-type headaches. A systematic review of 19 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) examining the effects of herbal ingredients for the acute treatment or prophylaxis of migraines found certain topically applied or inhaled EOs, such as peppermint and chamomile, to be effective for migraine pain alleviation; however, topically applied rose oil was not effective.11-13 Note: “topical application” in these studies implies application of the EO to ≥ 1 of the following areas: temples, forehead, behind ears, or above upper lip/below the nose.

Continue to: One RCT with 120 patients...

One RCT with 120 patients evaluated diluted intranasal peppermint oil and found that it reduced migraine intensity at similar rates to intranasal lidocaine.13 In this study, patients were randomized to receive one of the following: 4% lidocaine, 1.5% peppermint EO, or placebo. Two drops of the intranasal intervention were self-administered while the patient was in a supine position with their head suspended off the edge of the surface on which they were lying. They were instructed to stay in this position for at least 30 seconds after administration.

With regard to tension headache treatment, there is limited literature on the use of EOs. One study found that a preparation of peppermint oil applied topically to the temples and forehead of study participants resulted in significant analgesic effect.14

Fibromyalgia. Usual treatments for fibromyalgia include exercise, antidepressant and anticonvulsant medications, and stress management. Evidence also supports the use of inhaled and topically applied (with and without massage) lavender oil to improve symptoms.26 Positive effects may be related to the analgesic, anti-inflammatory, sleep-regulating, and anxiety-reducing effects of the major volatile compounds contained in lavender oil.

In one RCT with 42 patients with fibromyalgia, the use of inhaled lavender oil was shown to increase the perception of well-being (assessed on the validated SF-36 Health Survey Questionnaire) after 4 weeks.27 In this study, the patient applied 3 drops of an oil mixture, comprising 1 mL lavender EO and 10 mL of fixed neutral base oil, to the wrist and inhaled for 10 minutes before going to bed.

The use of a topical oil blend labeled “Oil 24” (containing camphor, rosemary, eucalyptus, peppermint, aloe vera, and lemon/orange) also has been shown to be more effective than placebo in managing fibromyalgia symptoms. A randomized controlled pilot study of 153 participants found that regular application of Oil 24 improved scores on pain scales and the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire.28

Continue to: GI disorders

GI disorders

Irritable bowel syndrome. Peppermint oil relaxes GI smooth muscle, which has led to investigation of its use in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) symptom amelioration.17 One meta-analysis including 12 RCTs with 835 patients with undifferentiated IBS found that orally ingested peppermint EO capsules reduced patient-reported symptoms of either abdominal pain or global symptoms.18

One study utilized the Total IBS Symptom Score to evaluate symptom reduction in patients with IBS-D (with diarrhea) and IBS-M (mixed) using 180-mg peppermint EO capsules ingested 3 times daily. There was a significant improvement in abdominal pain/discomfort, bloating/distension, pain at evacuation, and bowel urgency.19 A reduction in symptoms was observed after the first 24 hours of treatment and at the end of the 4-week treatment period.

In another study, among the 190 patients meeting Rome IV criteria for general (nonspecific) IBS who were treated with 182-mg peppermint EO capsules, no statistically significant reduction in overall symptom relief was found (based on outcome measures by the FDA and European Medicines Agency). However, in a secondary outcome analysis, peppermint oil produced greater improvements than placebo for the alleviation of abdominal pain, discomfort, and general IBS severity.20

Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy often explore integrative medicine approaches, including aromatherapy, to ameliorate adverse effects and improve quality of life.38 A few small studies have shown potential for the use of inhaled ginger oil to reduce nausea and vomiting severity and improve health-related quality-of-life measures in these patients.

For example, a study with 60 participants found that inhaling ginger EO for 10 minutes was beneficial for reducing both nausea and vomiting.39 A single-blind, controlled, randomized crossover study of 60 patients with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy showed that ginger EO inhaled 3 times per day for 2 minutes at a time can decrease the severity of nausea but had no effect on vomiting. The same study showed that health-related quality of life improved with the ginger oil treatment.40

Continue to: Other EOs such as cardamom...

Other EOs such as cardamom and peppermint show promise as an adjunctive treatment for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting as well.38

Postoperative nausea. A 2013 randomized trial of 303 patients examined the use of ginger EO, a blend of EOs (including ginger, spearmint, peppermint, and cardamom), and isopropyl alcohol. Both the single EO and EO blend significantly reduced the symptom of nausea. The number of antiemetic medications requested by patients receiving an EO also was significantly reduced compared to those receiving saline.15

The use of EOs to reduce nausea after cardiac operations was reviewed in an RCT of 60 surgical candidates using 10% peppermint oil via nebulization for 10 minutes.16 This technique was effective in reducing nausea during cardiac postoperative periods. Although the evidence for the use of EOs for postoperative nausea is not robust, it may be a useful and generally safe approach for this common issue.

Behavioral health

Insomnia. EOs have been used as a treatment for insomnia traditionally and in complementary, alternative, and integrative medicine. A 2014 systematic review of 15 quantitative studies, including 11 RCTs, evaluated the hypnotic effects of EOs through inhalation, finding the strongest evidence for lavender, jasmine, and peppermint oils.29 The majority of the studies in the systematic review used the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) to evaluate EO effectiveness. A more recent 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis that evaluated 34 RCTs found that inhalation of EOs, most notably lavender aromatherapy, is effective in improving sleep problems such as insomnia.30

Findings from multiple smaller RCTs were consistent with those of the aforementioned systematic reviews. For example, in a well-conducted parallel randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of 100 people using orally ingested lemon verbena, the authors concluded that this intervention can be a complementary therapy for improving sleep quality and reducing insomnia severity.31 Another RCT with 60 participants evaluated an inhaled EO blend (lemon, eucalyptus, tea tree, and peppermint) over 4 weeks and found lowered perceived stress and depression as well as better sleep quality, but no influence on objective physiologic data such as stress indices or immune states.32

Continue to: In a 2020 randomized crossover...

In a 2020 randomized crossover placebocontrolled trial of 37 participants with diabetes reporting insomnia, inhaled lavender improved sleep quality and quantity, quality of life, and mood but not physiologic or metabolic measures, such as fasting glucose.33 Findings were similar in a cohort of cardiac rehabilitation patients (n = 37) who were treated with either an inhaled combination of lavender, bergamot, and ylang ylang, or placebo; cotton balls infused with the intervention oil or placebo oil were placed at the patient’s bedside for 5 nights. Sleep quality of participants receiving intervention oil was significantly better than the sleep quality of participants receiving the placebo oil as measured by participant completion of the PSQI.34

Anxiety is a common disorder that can be managed with nonpharmacologic treatments such as yoga, deep breathing, meditation, and EO therapy.21,22 In a systematic review and meta-analysis, the inhaled and topical use (with or without massage) of lavender EO was shown to improve psychological and physical manifestations of anxiety.23 Lavender EO is purported to affect the parasympathetic nervous system via anxiolytic, sedative, analgesic, and anticonvulsant properties.24 One systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the anxiolytic effect of both inhaled and topical lavender EO found improvement in several biomarkers and physiologic data including blood pressure, heart rate, and cortisol levels, as well as a reduction in self-reported levels of anxiety, compared with placebo.25

Anxiety related to dental procedures is another area of study for the use of EOs. Two RCTs demonstrate statistically significant improvement in anxiety-related physiologic markers such as heart rate, blood pressure, and salivary cortisol levels in children who inhaled lavender EO during dental procedures.41,42 In 1 of the RCTs, the intervention was described as 3 drops of 100% lavender EO applied to a cloth and inhaled over the course of 3 minutes.41 Additionally, 2 studies found that orange EO was beneficial for dental procedure–induced anxiety, reducing pulse rates, cortisol levels, and self-reported anxiety.43,44

Dementia-related behavioral disturbances. A small, poorly designed study examining 2 EO blends—rosemary with lemon and lavender with orange—found some potential for improving cognitive function, especially in patients with Alzheimer disease.45 A Cochrane review of 13 RCTs totaling 708 patients concluded that it is not certain from the available evidence that EO therapy benefits patients with dementia in long-term-care facilities and hospital wards.46 Given that reporting of adverse events in the trials was poor, it is not possible to make conclusions about the risk vs benefit of EO therapy in this population.

Women’s health

Dysmenorrhea.

Continue to: In a randomized, double-blind clinical trial...

In a randomized, double-blind clinical trial of 48 women, a cream-based blend of lavender, clary sage, and marjoram EO (used topically in a 2:1:1 ratio diluted in unscented cream at 3% concentration and applied daily via abdominal massage) reduced participants’ reported menstrual pain symptoms and duration of pain.36 In a meta-analysis of 6 studies, topical abdominal application of EO (mainly lavender with or without other oils) with massage showed superiority over massage with placebo oils in reducing menstrual pain.37 A reduction in pain, mood symptoms, and fatigue in women with premenstrual symptoms was seen in an RCT of 77 patients using 3 drops of inhaled lavender EO.47

Labor. There is limited evidence for the use of EOs during labor. In an RCT of 104 women, patient-selected diffused EOs, including lavender, rose geranium, citrus, or jasmine, were found to help lower pain scores during the latent and early active phase of labor. There were no differences in labor augmentation, length of labor, perinatal outcomes, or need for additional pain medication.48

Other uses

Antimicrobial support. Some common EOs that have demonstrated antimicrobial properties are oregano, thyme, clove, lavender, clary sage, garlic, and cinnamon.49,50 Topical lemongrass and tea tree EOs have shown some degree of efficacy as an alternative treatment for acne, decolonization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and superficial fungal infections.51 Support for an oral mixture of EOs labeled Myrtol (containing eucalyptus, citrus myrtle, and lavender) for viral acute bronchitis and sinusitis was found in a review of 7 studies.52 More research needs to be done before clear recommendations can be made on the use of EOs as antimicrobials, but the current data are encouraging.

Insect repellent. Reviews of the insect-repellent properties of EOs have shown promise and are in the public’s interest due to increasing awareness of the potential health and environmental hazards of synthetic repellents.53 Individual compounds present in EOs such as citronella/lemongrass, basil, and eucalyptus species demonstrate high repellent activity.54 Since EOs require frequent reapplication for efficacy due to their highly volatile nature, scientists are currently developing a means to prolong their protection time through cream-based formulations.55

The bottom line

Because of the ubiquity of EOs, family physicians will undoubtedly be asked about them by patients, and it would be beneficial to feel comfortable discussing their most common uses. For most adult patients, the topical and periodic inhaled usage of EOs is generally safe.56

There is existing evidence of efficacy for a number of EOs, most strongly for lavender and peppermint. Future research into EOs should include higher-powered and higher-quality studies in order to provide more conclusive evidence regarding the continued use of EOs for many common conditions. More evidence-based information on dosing, application/use regimens, and safety in long-term use also will help providers better instruct patients on how to utilize EOs effectively and safely.

CORRESPONDENCE

Pooja Amy Shah, MD, Columbia University College of Physicians & Surgeons, 610 West 158th Street, New York, NY 10032; [email protected]

1. Butnariu M, Sarac I. Essential oils from plants. J Biotechnol Biomed Sci. 2018;1:35-43. doi: 10.14302/issn.2576-6694.jbbs-18-2489

2. Singh B, Sellam P, Majumder, J, et al. Floral essential oils : importance and uses for mankind. HortFlora Res Spectr. 2014;3:7-13. www.academia.edu/6707801/Floral_essential_oils_Importance_and_uses_for_mankind

3. Posadzki P, Alotaibi A, Ernst E. Adverse effects of aromatherapy: a systematic review of case reports and case series. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2012;24:147-161. doi: 10.3233/JRS-2012-0568

4. Sharmeen JB, Mahomoodally FM, Zengin G, et al. Essential oils as natural sources of fragrance compounds for cosmetics and cosmeceuticals. Molecules. 2021;26:666. doi: 10.3390/molecules26030666

5. Henley DV, Lipson N, Korach KS, et al. Prepubertal gynecomastia linked to lavender and tea tree oils. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:479-485. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064725

6. Nematollahi N, Weinberg JL, Flattery J, et al. Volatile chemical emissions from essential oils with therapeutic claims. Air Qual Atmosphere Health. 2021;14:365-369. doi: 10.1007/s11869-020-00941-4

7. Balekian D, Long A. Essential oil diffusers and asthma. Published February 24, 2020. Accessed September 22, 2023. www.aaaai.org/Allergist-Resources/Ask-the-Expert/Answers/Old-Ask-the-Experts/oil-diffusers-asthma

8. Aura Cacia. Quality. Accessed September 22, 2023. www.auracacia.com/quality

9. Now. Essential oil identity & purity testing. Accessed September 22, 2023. www.nowfoods.com/quality-safety/essential-oil-identity-purity-testing

10. Aura Cacia. GCMS documents. Accessed September 22, 2023. www.auracacia.com/aura-cacia-gcms-documents

11. Lopresti AL, Smith SJ, Drummond PD. Herbal treatments for migraine: a systematic review of randomised-controlled studies. Phytother Res. 2020;34:2493-2517. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6701

12. Niazi M, Hashempur MH, Taghizadeh M, et al. Efficacy of topical Rose (Rosa damascena Mill.) oil for migraine headache: A randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled cross-over trial. Complement Ther Med. 2017;34:35-41. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim. 2017.07.009

13. Rafieian-Kopaei M, Hasanpour-Dehkordi A, Lorigooini Z, et al. Comparing the effect of intranasal lidocaine 4% with peppermint essential oil drop 1.5% on migraine attacks: a double-blind clinical trial. Int J Prev Med. 2019;10:121. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_530_17

14. Göbel H, Fresenius J, Heinze A, et al. [Effectiveness of Oleum menthae piperitae and paracetamol in therapy of headache of the tension type]. Nervenarzt. 1996;67:672-681. doi: 10.1007/s001150050040

15. Hunt R, Dienemann J, Norton HJ, et al. Aromatherapy as treatment for postoperative nausea: a randomized trial. Anesth Analg. 2013;117:597-604. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31824a0b1c

16. Maghami M, Afazel MR, Azizi-Fini I, et al. The effect of aromatherapy with peppermint essential oil on nausea and vomiting after cardiac surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2020;40:101199. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101199

17. Hills JM, Aaronson PI. The mechanism of action of peppermint oil on gastrointestinal smooth muscle. An analysis using patch clamp electrophysiology and isolated tissue pharmacology in rabbit and guinea pig. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:55-65. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90459-x

18. Alammar N, Wang L, Saberi B, et al. The impact of peppermint oil on the irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis of the pooled clinical data. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019;19:21. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2409-0

19. Cash BD, Epstein MS, Shah SM. A novel delivery system of peppermint oil is an effective therapy for irritable bowel syndrome symptoms. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:560-571. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3858-7

20. Weerts ZZRM, Masclee AAM, Witteman BJM, et al. Efficacy and safety of peppermint oil in a randomized, double-blind trial of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:123-136. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.08.026

21. Ma X, Yue ZQ, Gong ZQ, et al. The effect of diaphragmatic breathing on attention, negative affect and stress in healthy adults. Front Psychol. 2017;8:874. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00874

22. Cabral P, Meyer HB, Ames D. Effectiveness of yoga therapy as a complementary treatment for major psychiatric disorders: a meta-analysis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. Published July 7, 2011. doi: 10.4088/PCC.10r01068

23. Donelli D, Antonelli M, Bellinazzi C, et ala. Effects of lavender on anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytomedicine Int J Phytother Phytopharm. 2019;65:153099. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2019.153099

24. Koulivand PH, Khaleghi Ghadiri M, Gorji A. Lavender and the nervous system. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:1-10. doi: 10.1155/2013/681304

25. Kang HJ, Nam ES, Lee Y, et al. How strong is the evidence for the anxiolytic efficacy of lavender? Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Asian Nurs Res. 2019;13:295-305. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2019.11.003

26. Barão Paixão VL, Freire de Carvalho J. Essential oil therapy in rheumatic diseases: a systematic review. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2021;43:101391. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2021.101391

27. Yasa Ozturk G, Bashan I. The effect of aromatherapy with lavender oil on the health-related quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia. J Food Qual. 2021;2021:1-5. doi: 10.1155/2021/9938630

28. Ko GD, Hum A, Traitses G, et al. Effects of topical O24 essential oils on patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: a randomized, placebo controlled pilot study. J Musculoskelet Pain. 2007;15:11-19. doi: 10.1300/J094v15n01_03

29. Lillehei AS, Halcon LL. A systematic review of the effect of inhaled essential oils on sleep. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20:441-451. doi: 10.1089/acm.2013.0311

30. Cheong MJ, Kim S, Kim JS, et al. A systematic literature review and meta-analysis of the clinical effects of aroma inhalation therapy on sleep problems. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e24652. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000024652

31. Afrasiabian F, Mirabzadeh Ardakani M, Rahmani K, et al. Aloysia citriodora Paláu (lemon verbena) for insomnia patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of efficacy and safety. Phytother Res PTR. 2019;33:350-359. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6228

32. Lee M, Lim S, Song JA, et al. The effects of aromatherapy essential oil inhalation on stress, sleep quality and immunity in healthy adults: randomized controlled trial. Eur J Integr Med. 2017;12:79-86. doi: 10.1016/j.eujim.2017.04.009

33. Nasiri Lari Z, Hajimonfarednejad M, Riasatian M, et al. Efficacy of inhaled Lavandula angustifolia Mill. Essential oil on sleep quality, quality of life and metabolic control in patients with diabetes mellitus type II and insomnia. J Ethnopharmacol. 2020;251:112560. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.112560

34. McDonnell B, Newcomb P. Trial of essential oils to improve sleep for patients in cardiac rehabilitation. J Altern Complement Med N Y N. 2019;25:1193-1199. doi: 10.1089/acm.2019.0222

35. Song JA, Lee MK, Min E, et al. Effects of aromatherapy on dysmenorrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;84:1-11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.01.016

36. Ou MC, Hsu TF, Lai AC, et al. Pain relief assessment by aromatic essential oil massage on outpatients with primary dysmenorrhea: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial: PD pain relief by aromatic oil massage. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2012;38:817-822. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01802.x

37. Sut N, Kahyaoglu-Sut H. Effect of aromatherapy massage on pain in primary dysmenorrhea: a meta-analysis. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2017;27:5-10. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2017.01.001

38. Keyhanmehr AS, Kolouri S, Heydarirad G, et al. Aromatherapy for the management of cancer complications: a narrative review. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;31:175-180. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.02.009

39. Sriningsih I, Elisa E, Lestari KP. Aromatherapy ginger use in patients with nausea & vomiting on post cervical cancer chemotherapy. KEMAS J Kesehat Masy. 2017;13:59-68. doi: 10.15294/kemas.v13i1.5367

40. Lua PL, Salihah N, Mazlan N. Effects of inhaled ginger aromatherapy on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and health-related quality of life in women with breast cancer. Complement Ther Med. 2015;23:396-404. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2015.03.009

41. Arslan I, Aydinoglu S, Karan NB. Can lavender oil inhalation help to overcome dental anxiety and pain in children? A randomized clinical trial. Eur J Pediatr. 2020;179:985-992. doi: 10.1007/s00431-020-03595-7

42. Ghaderi F, Solhjou N. The effects of lavender aromatherapy on stress and pain perception in children during dental treatment: a randomized clinical trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2020;40:101182. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101182

43. Jafarzadeh M, Arman S, Pour FF. Effect of aromatherapy with orange essential oil on salivary cortisol and pulse rate in children during dental treatment: a randomized controlled clinical trial. Adv Biomed Res. 2013;2:10. doi: 10.4103/2277-9175.107968

44. Lehrner J, Eckersberger C, Walla P, et al. Ambient odor of orange in a dental office reduces anxiety and improves mood in female patients. Physiol Behav. 2000;71:83-86. doi: 10.1016/S0031-9384(00)00308-5

45. Jimbo D, Kimura Y, Taniguchi M, et al. Effect of aromatherapy on patients with Alzheimer’s disease. Psychogeriatrics. 2009;9:173-179. doi: 10.1111/j.1479-8301.2009.00299.x

46. Ball EL, Owen-Booth B, Gray A, et al. Aromatherapy for dementia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2020;(8). doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003150.pub3

47. Uzunçakmak T, Ayaz Alkaya S. Effect of aromatherapy on coping with premenstrual syndrome: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Med. 2018;36:63-67. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2017.11.022

48. Tanvisut R, Traisrisilp K, Tongsong T. Efficacy of aromatherapy for reducing pain during labor: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2018;297:1145-1150. doi: 10.1007/s00404-018-4700-1

49. Ramsey JT, Shropshire BC, Nagy TR, et al. Essential oils and health. Yale J Biol Med. 2020;93:291-305.

50. Puškárová A, Bučková M, Kraková L, et al. The antibacterial and antifungal activity of six essential oils and their cyto/genotoxicity to human HEL 12469 cells. Sci Rep. 2017;7:8211. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08673-9

51. Deyno S, Mtewa AG, Abebe A, et al. Essential oils as topical anti-infective agents: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Complement Ther Med. 2019;47:102224. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2019.102224

52. Prall S, Bowles EJ, Bennett K, et al. Effects of essential oils on symptoms and course (duration and severity) of viral respiratory infections in humans: a rapid review. Adv Integr Med. 2020;7:218-221. doi: 10.1016/j.aimed.2020.07.005

53. Weeks JA, Guiney PD, Nikiforov AI. Assessment of the environmental fate and ecotoxicity of N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide (DEET). Integr Environ Assess Manag. 2012;8:120-134. doi: 10.1002/ieam.1246

54. Nerio LS, Olivero-Verbel J, Stashenko E. Repellent activity of essential oils: a review. Bioresour Technol. 2010;101:372-378. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.07.048

55. Lee MY. Essential oils as repellents against arthropods. BioMed Res Int. 2018;2018:6860271. doi: 10.1155/2018/6860271

56. Göbel H, Heinze A, Heinze-Kuhn K, et al. [Peppermint oil in the acute treatment of tension-type headache]. Schmerz Berl Ger. 2016;30:295-310. doi: 10.1007/s00482-016-0109-6

Essential oils (EOs), which are concentrated plant-based oils, have become ubiquitous over the past decade. Given the far reach of EOs and their longtime use in traditional, complementary, alternative, and integrative medicine, it is imperative that clinicians have some knowledge of the potential benefits, risks, and overall efficacy.

Commonly used for aromatic benefits (aromatherapy), EOs are now also incorporated into a multitude of products promoting health and wellness. EOs are sold as individual products and can be a component in consumer goods such as cosmetics, body care/hygiene/beauty products, laundry detergents, insect repellents, over-the-counter medications, and food.

The review that follows presents the most current evidence available. With that said, it’s important to keep in mind some caveats that relate to this evidence. First, the studies cited tend to have a small sample size. Second, a majority of these studies were conducted in countries where there appears to be a significant culture of EO use, which could contribute to confirmation bias. Finally, in a number of the studies, there is concern for publication bias as well as a discrepancy between calculated statistical significance and actual clinical relevance.

What are essential oils?

EOs generally are made by extracting the oil from leaves, bark, flowers, seeds/fruit, rinds, and/or roots by steaming or pressing parts of a plant. It can take several pounds of plant material to produce a single bottle of EO, which usually contains ≥ 15 to 30 mL (.5 to 1 oz).1

Some commonly used EOs in the United States are lavender, peppermint, rose, clary sage, tea tree, eucalyptus, and citrus; however, there are approximately 300 EOs available.2 EOs are used most often via topical application, inhalation, or ingestion.

As with any botanical agent, EOs are complex substances often containing a multitude of chemical compounds.1 Because of the complex makeup of EOs, which often contain up to 100 volatile organic compounds, and their wide-ranging potential effects, applying the scientific method to study effectiveness poses a challenge that has limited their adoption in evidence-based practice.2

Availability and cost. EOs can be purchased at large retailers (eg, grocery stores, drug stores) and smaller health food stores, as well as on the Internet. Various EO vehicles, such as inhalers and topical creams, also can be purchased at these stores.

Continue to: The cost varies...

The cost varies enormously by manufacturer and type of plant used to make the EO. Common EOs such as peppermint and lavender oil generally cost $10 to $25, while rarer plant oils can cost $80 or more per bottle.

How safe are essential oils?

Patients may assume EOs are harmless because they are derived from natural plants and have been used medicinally for centuries. However, care must be taken with their use.

The safest way to use EOs is topically, although due to their highly concentrated nature, EOs should be diluted in an unscented neutral carrier oil such as coconut, jojoba, olive, or sweet almond.3 Ingestion of certain oils can cause hepatotoxicity, seizures, and even death.3 In fact, patients should speak with a knowledgeable physician before purchasing any oral EO capsules.

Whether used topically or ingested, all EOs carry risk for skin irritation and allergic reactions, and oral ingestion may result in some negative gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects.4 A case report of 3 patients published in 2007 identified the potential for lavender and tea tree EOs to be endocrine disruptors.5

Inhalation of EOs may be harmful, as they emit many volatile organic compounds, some of which are considered potentially hazardous.6 At this time, there is insufficient evidence regarding inhaled EOs and their direct connection to respiratory health. It is reasonable to suggest, however, that the prolonged use of EOs and their use by patients who have lung conditions such as asthma or COPD should be avoided.7

Continue to: How are quality and purity assessed?

How are quality and purity assessed?

Like other dietary supplements, EOs are not regulated. No US regulatory agencies (eg, the US Food and Drug Administration [FDA] or Department of Agriculture [USDA]) certify or approve EOs for quality and purity. Bottles labeled with “QAI” for Quality Assurance International or “USDA Organic” will ensure the plant constituents used in the EO are from organic farming but do not attest to quality or purity.

Manufacturers commonly use marketing terms such as “therapeutic grade” or “pure” to sell products, but again, these terms do not reflect the product’s quality or purity. A labeled single EO may contain contaminants, alcohol, or additional ingredients.7 When choosing to use EOs, identifying reputable brands is essential; one resource is the independent testing organization ConsumerLab.com.

It is important to assess the manufacturer and read ingredient labels before purchasing an EO to understand what the product contains. Reputable companies will identify the plant ingredient, usually by the formal Latin binomial name, and explain the extraction process. A more certain way to assess the quality and purity of an EO is to ask the manufacturer to provide a certificate of analysis and gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy (GC/MS) data for the specific product. Some manufacturers offer GC/MS test results on their website Quality page.8 Others have detailed information on quality and testing, and GC/MS test reports can be obtained.9 Yet another manufacturer has test results on a product page matching reports to batch codes.10

Which conditions have evidence of benefit from essential oils?

EOs currently are being studied for treatment of many conditions—including pain, GI disorders, behavioral health disorders, and women’s health issues. The TABLE summarizes the conditions treated, outcomes, and practical applications of EOs.11-44

Pain

Headache. As an adjunct to available medications and procedures for headache treatment, EOs are one of the nonpharmacologic modalities that patients and clinicians have at their disposal for both migraine and tension-type headaches. A systematic review of 19 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) examining the effects of herbal ingredients for the acute treatment or prophylaxis of migraines found certain topically applied or inhaled EOs, such as peppermint and chamomile, to be effective for migraine pain alleviation; however, topically applied rose oil was not effective.11-13 Note: “topical application” in these studies implies application of the EO to ≥ 1 of the following areas: temples, forehead, behind ears, or above upper lip/below the nose.

Continue to: One RCT with 120 patients...

One RCT with 120 patients evaluated diluted intranasal peppermint oil and found that it reduced migraine intensity at similar rates to intranasal lidocaine.13 In this study, patients were randomized to receive one of the following: 4% lidocaine, 1.5% peppermint EO, or placebo. Two drops of the intranasal intervention were self-administered while the patient was in a supine position with their head suspended off the edge of the surface on which they were lying. They were instructed to stay in this position for at least 30 seconds after administration.

With regard to tension headache treatment, there is limited literature on the use of EOs. One study found that a preparation of peppermint oil applied topically to the temples and forehead of study participants resulted in significant analgesic effect.14

Fibromyalgia. Usual treatments for fibromyalgia include exercise, antidepressant and anticonvulsant medications, and stress management. Evidence also supports the use of inhaled and topically applied (with and without massage) lavender oil to improve symptoms.26 Positive effects may be related to the analgesic, anti-inflammatory, sleep-regulating, and anxiety-reducing effects of the major volatile compounds contained in lavender oil.

In one RCT with 42 patients with fibromyalgia, the use of inhaled lavender oil was shown to increase the perception of well-being (assessed on the validated SF-36 Health Survey Questionnaire) after 4 weeks.27 In this study, the patient applied 3 drops of an oil mixture, comprising 1 mL lavender EO and 10 mL of fixed neutral base oil, to the wrist and inhaled for 10 minutes before going to bed.

The use of a topical oil blend labeled “Oil 24” (containing camphor, rosemary, eucalyptus, peppermint, aloe vera, and lemon/orange) also has been shown to be more effective than placebo in managing fibromyalgia symptoms. A randomized controlled pilot study of 153 participants found that regular application of Oil 24 improved scores on pain scales and the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire.28

Continue to: GI disorders

GI disorders

Irritable bowel syndrome. Peppermint oil relaxes GI smooth muscle, which has led to investigation of its use in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) symptom amelioration.17 One meta-analysis including 12 RCTs with 835 patients with undifferentiated IBS found that orally ingested peppermint EO capsules reduced patient-reported symptoms of either abdominal pain or global symptoms.18

One study utilized the Total IBS Symptom Score to evaluate symptom reduction in patients with IBS-D (with diarrhea) and IBS-M (mixed) using 180-mg peppermint EO capsules ingested 3 times daily. There was a significant improvement in abdominal pain/discomfort, bloating/distension, pain at evacuation, and bowel urgency.19 A reduction in symptoms was observed after the first 24 hours of treatment and at the end of the 4-week treatment period.

In another study, among the 190 patients meeting Rome IV criteria for general (nonspecific) IBS who were treated with 182-mg peppermint EO capsules, no statistically significant reduction in overall symptom relief was found (based on outcome measures by the FDA and European Medicines Agency). However, in a secondary outcome analysis, peppermint oil produced greater improvements than placebo for the alleviation of abdominal pain, discomfort, and general IBS severity.20

Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy often explore integrative medicine approaches, including aromatherapy, to ameliorate adverse effects and improve quality of life.38 A few small studies have shown potential for the use of inhaled ginger oil to reduce nausea and vomiting severity and improve health-related quality-of-life measures in these patients.

For example, a study with 60 participants found that inhaling ginger EO for 10 minutes was beneficial for reducing both nausea and vomiting.39 A single-blind, controlled, randomized crossover study of 60 patients with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy showed that ginger EO inhaled 3 times per day for 2 minutes at a time can decrease the severity of nausea but had no effect on vomiting. The same study showed that health-related quality of life improved with the ginger oil treatment.40

Continue to: Other EOs such as cardamom...

Other EOs such as cardamom and peppermint show promise as an adjunctive treatment for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting as well.38

Postoperative nausea. A 2013 randomized trial of 303 patients examined the use of ginger EO, a blend of EOs (including ginger, spearmint, peppermint, and cardamom), and isopropyl alcohol. Both the single EO and EO blend significantly reduced the symptom of nausea. The number of antiemetic medications requested by patients receiving an EO also was significantly reduced compared to those receiving saline.15

The use of EOs to reduce nausea after cardiac operations was reviewed in an RCT of 60 surgical candidates using 10% peppermint oil via nebulization for 10 minutes.16 This technique was effective in reducing nausea during cardiac postoperative periods. Although the evidence for the use of EOs for postoperative nausea is not robust, it may be a useful and generally safe approach for this common issue.

Behavioral health

Insomnia. EOs have been used as a treatment for insomnia traditionally and in complementary, alternative, and integrative medicine. A 2014 systematic review of 15 quantitative studies, including 11 RCTs, evaluated the hypnotic effects of EOs through inhalation, finding the strongest evidence for lavender, jasmine, and peppermint oils.29 The majority of the studies in the systematic review used the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) to evaluate EO effectiveness. A more recent 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis that evaluated 34 RCTs found that inhalation of EOs, most notably lavender aromatherapy, is effective in improving sleep problems such as insomnia.30

Findings from multiple smaller RCTs were consistent with those of the aforementioned systematic reviews. For example, in a well-conducted parallel randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of 100 people using orally ingested lemon verbena, the authors concluded that this intervention can be a complementary therapy for improving sleep quality and reducing insomnia severity.31 Another RCT with 60 participants evaluated an inhaled EO blend (lemon, eucalyptus, tea tree, and peppermint) over 4 weeks and found lowered perceived stress and depression as well as better sleep quality, but no influence on objective physiologic data such as stress indices or immune states.32

Continue to: In a 2020 randomized crossover...

In a 2020 randomized crossover placebocontrolled trial of 37 participants with diabetes reporting insomnia, inhaled lavender improved sleep quality and quantity, quality of life, and mood but not physiologic or metabolic measures, such as fasting glucose.33 Findings were similar in a cohort of cardiac rehabilitation patients (n = 37) who were treated with either an inhaled combination of lavender, bergamot, and ylang ylang, or placebo; cotton balls infused with the intervention oil or placebo oil were placed at the patient’s bedside for 5 nights. Sleep quality of participants receiving intervention oil was significantly better than the sleep quality of participants receiving the placebo oil as measured by participant completion of the PSQI.34

Anxiety is a common disorder that can be managed with nonpharmacologic treatments such as yoga, deep breathing, meditation, and EO therapy.21,22 In a systematic review and meta-analysis, the inhaled and topical use (with or without massage) of lavender EO was shown to improve psychological and physical manifestations of anxiety.23 Lavender EO is purported to affect the parasympathetic nervous system via anxiolytic, sedative, analgesic, and anticonvulsant properties.24 One systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the anxiolytic effect of both inhaled and topical lavender EO found improvement in several biomarkers and physiologic data including blood pressure, heart rate, and cortisol levels, as well as a reduction in self-reported levels of anxiety, compared with placebo.25

Anxiety related to dental procedures is another area of study for the use of EOs. Two RCTs demonstrate statistically significant improvement in anxiety-related physiologic markers such as heart rate, blood pressure, and salivary cortisol levels in children who inhaled lavender EO during dental procedures.41,42 In 1 of the RCTs, the intervention was described as 3 drops of 100% lavender EO applied to a cloth and inhaled over the course of 3 minutes.41 Additionally, 2 studies found that orange EO was beneficial for dental procedure–induced anxiety, reducing pulse rates, cortisol levels, and self-reported anxiety.43,44

Dementia-related behavioral disturbances. A small, poorly designed study examining 2 EO blends—rosemary with lemon and lavender with orange—found some potential for improving cognitive function, especially in patients with Alzheimer disease.45 A Cochrane review of 13 RCTs totaling 708 patients concluded that it is not certain from the available evidence that EO therapy benefits patients with dementia in long-term-care facilities and hospital wards.46 Given that reporting of adverse events in the trials was poor, it is not possible to make conclusions about the risk vs benefit of EO therapy in this population.

Women’s health

Dysmenorrhea.

Continue to: In a randomized, double-blind clinical trial...

In a randomized, double-blind clinical trial of 48 women, a cream-based blend of lavender, clary sage, and marjoram EO (used topically in a 2:1:1 ratio diluted in unscented cream at 3% concentration and applied daily via abdominal massage) reduced participants’ reported menstrual pain symptoms and duration of pain.36 In a meta-analysis of 6 studies, topical abdominal application of EO (mainly lavender with or without other oils) with massage showed superiority over massage with placebo oils in reducing menstrual pain.37 A reduction in pain, mood symptoms, and fatigue in women with premenstrual symptoms was seen in an RCT of 77 patients using 3 drops of inhaled lavender EO.47

Labor. There is limited evidence for the use of EOs during labor. In an RCT of 104 women, patient-selected diffused EOs, including lavender, rose geranium, citrus, or jasmine, were found to help lower pain scores during the latent and early active phase of labor. There were no differences in labor augmentation, length of labor, perinatal outcomes, or need for additional pain medication.48

Other uses

Antimicrobial support. Some common EOs that have demonstrated antimicrobial properties are oregano, thyme, clove, lavender, clary sage, garlic, and cinnamon.49,50 Topical lemongrass and tea tree EOs have shown some degree of efficacy as an alternative treatment for acne, decolonization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and superficial fungal infections.51 Support for an oral mixture of EOs labeled Myrtol (containing eucalyptus, citrus myrtle, and lavender) for viral acute bronchitis and sinusitis was found in a review of 7 studies.52 More research needs to be done before clear recommendations can be made on the use of EOs as antimicrobials, but the current data are encouraging.

Insect repellent. Reviews of the insect-repellent properties of EOs have shown promise and are in the public’s interest due to increasing awareness of the potential health and environmental hazards of synthetic repellents.53 Individual compounds present in EOs such as citronella/lemongrass, basil, and eucalyptus species demonstrate high repellent activity.54 Since EOs require frequent reapplication for efficacy due to their highly volatile nature, scientists are currently developing a means to prolong their protection time through cream-based formulations.55

The bottom line

Because of the ubiquity of EOs, family physicians will undoubtedly be asked about them by patients, and it would be beneficial to feel comfortable discussing their most common uses. For most adult patients, the topical and periodic inhaled usage of EOs is generally safe.56

There is existing evidence of efficacy for a number of EOs, most strongly for lavender and peppermint. Future research into EOs should include higher-powered and higher-quality studies in order to provide more conclusive evidence regarding the continued use of EOs for many common conditions. More evidence-based information on dosing, application/use regimens, and safety in long-term use also will help providers better instruct patients on how to utilize EOs effectively and safely.

CORRESPONDENCE

Pooja Amy Shah, MD, Columbia University College of Physicians & Surgeons, 610 West 158th Street, New York, NY 10032; [email protected]

Essential oils (EOs), which are concentrated plant-based oils, have become ubiquitous over the past decade. Given the far reach of EOs and their longtime use in traditional, complementary, alternative, and integrative medicine, it is imperative that clinicians have some knowledge of the potential benefits, risks, and overall efficacy.

Commonly used for aromatic benefits (aromatherapy), EOs are now also incorporated into a multitude of products promoting health and wellness. EOs are sold as individual products and can be a component in consumer goods such as cosmetics, body care/hygiene/beauty products, laundry detergents, insect repellents, over-the-counter medications, and food.

The review that follows presents the most current evidence available. With that said, it’s important to keep in mind some caveats that relate to this evidence. First, the studies cited tend to have a small sample size. Second, a majority of these studies were conducted in countries where there appears to be a significant culture of EO use, which could contribute to confirmation bias. Finally, in a number of the studies, there is concern for publication bias as well as a discrepancy between calculated statistical significance and actual clinical relevance.

What are essential oils?

EOs generally are made by extracting the oil from leaves, bark, flowers, seeds/fruit, rinds, and/or roots by steaming or pressing parts of a plant. It can take several pounds of plant material to produce a single bottle of EO, which usually contains ≥ 15 to 30 mL (.5 to 1 oz).1

Some commonly used EOs in the United States are lavender, peppermint, rose, clary sage, tea tree, eucalyptus, and citrus; however, there are approximately 300 EOs available.2 EOs are used most often via topical application, inhalation, or ingestion.

As with any botanical agent, EOs are complex substances often containing a multitude of chemical compounds.1 Because of the complex makeup of EOs, which often contain up to 100 volatile organic compounds, and their wide-ranging potential effects, applying the scientific method to study effectiveness poses a challenge that has limited their adoption in evidence-based practice.2

Availability and cost. EOs can be purchased at large retailers (eg, grocery stores, drug stores) and smaller health food stores, as well as on the Internet. Various EO vehicles, such as inhalers and topical creams, also can be purchased at these stores.

Continue to: The cost varies...

The cost varies enormously by manufacturer and type of plant used to make the EO. Common EOs such as peppermint and lavender oil generally cost $10 to $25, while rarer plant oils can cost $80 or more per bottle.

How safe are essential oils?

Patients may assume EOs are harmless because they are derived from natural plants and have been used medicinally for centuries. However, care must be taken with their use.

The safest way to use EOs is topically, although due to their highly concentrated nature, EOs should be diluted in an unscented neutral carrier oil such as coconut, jojoba, olive, or sweet almond.3 Ingestion of certain oils can cause hepatotoxicity, seizures, and even death.3 In fact, patients should speak with a knowledgeable physician before purchasing any oral EO capsules.

Whether used topically or ingested, all EOs carry risk for skin irritation and allergic reactions, and oral ingestion may result in some negative gastrointestinal (GI) adverse effects.4 A case report of 3 patients published in 2007 identified the potential for lavender and tea tree EOs to be endocrine disruptors.5

Inhalation of EOs may be harmful, as they emit many volatile organic compounds, some of which are considered potentially hazardous.6 At this time, there is insufficient evidence regarding inhaled EOs and their direct connection to respiratory health. It is reasonable to suggest, however, that the prolonged use of EOs and their use by patients who have lung conditions such as asthma or COPD should be avoided.7

Continue to: How are quality and purity assessed?

How are quality and purity assessed?

Like other dietary supplements, EOs are not regulated. No US regulatory agencies (eg, the US Food and Drug Administration [FDA] or Department of Agriculture [USDA]) certify or approve EOs for quality and purity. Bottles labeled with “QAI” for Quality Assurance International or “USDA Organic” will ensure the plant constituents used in the EO are from organic farming but do not attest to quality or purity.

Manufacturers commonly use marketing terms such as “therapeutic grade” or “pure” to sell products, but again, these terms do not reflect the product’s quality or purity. A labeled single EO may contain contaminants, alcohol, or additional ingredients.7 When choosing to use EOs, identifying reputable brands is essential; one resource is the independent testing organization ConsumerLab.com.

It is important to assess the manufacturer and read ingredient labels before purchasing an EO to understand what the product contains. Reputable companies will identify the plant ingredient, usually by the formal Latin binomial name, and explain the extraction process. A more certain way to assess the quality and purity of an EO is to ask the manufacturer to provide a certificate of analysis and gas chromatography/mass spectroscopy (GC/MS) data for the specific product. Some manufacturers offer GC/MS test results on their website Quality page.8 Others have detailed information on quality and testing, and GC/MS test reports can be obtained.9 Yet another manufacturer has test results on a product page matching reports to batch codes.10

Which conditions have evidence of benefit from essential oils?

EOs currently are being studied for treatment of many conditions—including pain, GI disorders, behavioral health disorders, and women’s health issues. The TABLE summarizes the conditions treated, outcomes, and practical applications of EOs.11-44

Pain

Headache. As an adjunct to available medications and procedures for headache treatment, EOs are one of the nonpharmacologic modalities that patients and clinicians have at their disposal for both migraine and tension-type headaches. A systematic review of 19 randomized controlled trials (RCTs) examining the effects of herbal ingredients for the acute treatment or prophylaxis of migraines found certain topically applied or inhaled EOs, such as peppermint and chamomile, to be effective for migraine pain alleviation; however, topically applied rose oil was not effective.11-13 Note: “topical application” in these studies implies application of the EO to ≥ 1 of the following areas: temples, forehead, behind ears, or above upper lip/below the nose.

Continue to: One RCT with 120 patients...

One RCT with 120 patients evaluated diluted intranasal peppermint oil and found that it reduced migraine intensity at similar rates to intranasal lidocaine.13 In this study, patients were randomized to receive one of the following: 4% lidocaine, 1.5% peppermint EO, or placebo. Two drops of the intranasal intervention were self-administered while the patient was in a supine position with their head suspended off the edge of the surface on which they were lying. They were instructed to stay in this position for at least 30 seconds after administration.

With regard to tension headache treatment, there is limited literature on the use of EOs. One study found that a preparation of peppermint oil applied topically to the temples and forehead of study participants resulted in significant analgesic effect.14

Fibromyalgia. Usual treatments for fibromyalgia include exercise, antidepressant and anticonvulsant medications, and stress management. Evidence also supports the use of inhaled and topically applied (with and without massage) lavender oil to improve symptoms.26 Positive effects may be related to the analgesic, anti-inflammatory, sleep-regulating, and anxiety-reducing effects of the major volatile compounds contained in lavender oil.

In one RCT with 42 patients with fibromyalgia, the use of inhaled lavender oil was shown to increase the perception of well-being (assessed on the validated SF-36 Health Survey Questionnaire) after 4 weeks.27 In this study, the patient applied 3 drops of an oil mixture, comprising 1 mL lavender EO and 10 mL of fixed neutral base oil, to the wrist and inhaled for 10 minutes before going to bed.

The use of a topical oil blend labeled “Oil 24” (containing camphor, rosemary, eucalyptus, peppermint, aloe vera, and lemon/orange) also has been shown to be more effective than placebo in managing fibromyalgia symptoms. A randomized controlled pilot study of 153 participants found that regular application of Oil 24 improved scores on pain scales and the Fibromyalgia Impact Questionnaire.28

Continue to: GI disorders

GI disorders

Irritable bowel syndrome. Peppermint oil relaxes GI smooth muscle, which has led to investigation of its use in irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) symptom amelioration.17 One meta-analysis including 12 RCTs with 835 patients with undifferentiated IBS found that orally ingested peppermint EO capsules reduced patient-reported symptoms of either abdominal pain or global symptoms.18

One study utilized the Total IBS Symptom Score to evaluate symptom reduction in patients with IBS-D (with diarrhea) and IBS-M (mixed) using 180-mg peppermint EO capsules ingested 3 times daily. There was a significant improvement in abdominal pain/discomfort, bloating/distension, pain at evacuation, and bowel urgency.19 A reduction in symptoms was observed after the first 24 hours of treatment and at the end of the 4-week treatment period.

In another study, among the 190 patients meeting Rome IV criteria for general (nonspecific) IBS who were treated with 182-mg peppermint EO capsules, no statistically significant reduction in overall symptom relief was found (based on outcome measures by the FDA and European Medicines Agency). However, in a secondary outcome analysis, peppermint oil produced greater improvements than placebo for the alleviation of abdominal pain, discomfort, and general IBS severity.20

Chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting. Patients with cancer undergoing chemotherapy often explore integrative medicine approaches, including aromatherapy, to ameliorate adverse effects and improve quality of life.38 A few small studies have shown potential for the use of inhaled ginger oil to reduce nausea and vomiting severity and improve health-related quality-of-life measures in these patients.

For example, a study with 60 participants found that inhaling ginger EO for 10 minutes was beneficial for reducing both nausea and vomiting.39 A single-blind, controlled, randomized crossover study of 60 patients with breast cancer receiving chemotherapy showed that ginger EO inhaled 3 times per day for 2 minutes at a time can decrease the severity of nausea but had no effect on vomiting. The same study showed that health-related quality of life improved with the ginger oil treatment.40

Continue to: Other EOs such as cardamom...

Other EOs such as cardamom and peppermint show promise as an adjunctive treatment for chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting as well.38

Postoperative nausea. A 2013 randomized trial of 303 patients examined the use of ginger EO, a blend of EOs (including ginger, spearmint, peppermint, and cardamom), and isopropyl alcohol. Both the single EO and EO blend significantly reduced the symptom of nausea. The number of antiemetic medications requested by patients receiving an EO also was significantly reduced compared to those receiving saline.15

The use of EOs to reduce nausea after cardiac operations was reviewed in an RCT of 60 surgical candidates using 10% peppermint oil via nebulization for 10 minutes.16 This technique was effective in reducing nausea during cardiac postoperative periods. Although the evidence for the use of EOs for postoperative nausea is not robust, it may be a useful and generally safe approach for this common issue.

Behavioral health

Insomnia. EOs have been used as a treatment for insomnia traditionally and in complementary, alternative, and integrative medicine. A 2014 systematic review of 15 quantitative studies, including 11 RCTs, evaluated the hypnotic effects of EOs through inhalation, finding the strongest evidence for lavender, jasmine, and peppermint oils.29 The majority of the studies in the systematic review used the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) to evaluate EO effectiveness. A more recent 2021 systematic review and meta-analysis that evaluated 34 RCTs found that inhalation of EOs, most notably lavender aromatherapy, is effective in improving sleep problems such as insomnia.30

Findings from multiple smaller RCTs were consistent with those of the aforementioned systematic reviews. For example, in a well-conducted parallel randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial of 100 people using orally ingested lemon verbena, the authors concluded that this intervention can be a complementary therapy for improving sleep quality and reducing insomnia severity.31 Another RCT with 60 participants evaluated an inhaled EO blend (lemon, eucalyptus, tea tree, and peppermint) over 4 weeks and found lowered perceived stress and depression as well as better sleep quality, but no influence on objective physiologic data such as stress indices or immune states.32

Continue to: In a 2020 randomized crossover...

In a 2020 randomized crossover placebocontrolled trial of 37 participants with diabetes reporting insomnia, inhaled lavender improved sleep quality and quantity, quality of life, and mood but not physiologic or metabolic measures, such as fasting glucose.33 Findings were similar in a cohort of cardiac rehabilitation patients (n = 37) who were treated with either an inhaled combination of lavender, bergamot, and ylang ylang, or placebo; cotton balls infused with the intervention oil or placebo oil were placed at the patient’s bedside for 5 nights. Sleep quality of participants receiving intervention oil was significantly better than the sleep quality of participants receiving the placebo oil as measured by participant completion of the PSQI.34

Anxiety is a common disorder that can be managed with nonpharmacologic treatments such as yoga, deep breathing, meditation, and EO therapy.21,22 In a systematic review and meta-analysis, the inhaled and topical use (with or without massage) of lavender EO was shown to improve psychological and physical manifestations of anxiety.23 Lavender EO is purported to affect the parasympathetic nervous system via anxiolytic, sedative, analgesic, and anticonvulsant properties.24 One systematic review and meta-analysis evaluating the anxiolytic effect of both inhaled and topical lavender EO found improvement in several biomarkers and physiologic data including blood pressure, heart rate, and cortisol levels, as well as a reduction in self-reported levels of anxiety, compared with placebo.25

Anxiety related to dental procedures is another area of study for the use of EOs. Two RCTs demonstrate statistically significant improvement in anxiety-related physiologic markers such as heart rate, blood pressure, and salivary cortisol levels in children who inhaled lavender EO during dental procedures.41,42 In 1 of the RCTs, the intervention was described as 3 drops of 100% lavender EO applied to a cloth and inhaled over the course of 3 minutes.41 Additionally, 2 studies found that orange EO was beneficial for dental procedure–induced anxiety, reducing pulse rates, cortisol levels, and self-reported anxiety.43,44

Dementia-related behavioral disturbances. A small, poorly designed study examining 2 EO blends—rosemary with lemon and lavender with orange—found some potential for improving cognitive function, especially in patients with Alzheimer disease.45 A Cochrane review of 13 RCTs totaling 708 patients concluded that it is not certain from the available evidence that EO therapy benefits patients with dementia in long-term-care facilities and hospital wards.46 Given that reporting of adverse events in the trials was poor, it is not possible to make conclusions about the risk vs benefit of EO therapy in this population.

Women’s health

Dysmenorrhea.

Continue to: In a randomized, double-blind clinical trial...

In a randomized, double-blind clinical trial of 48 women, a cream-based blend of lavender, clary sage, and marjoram EO (used topically in a 2:1:1 ratio diluted in unscented cream at 3% concentration and applied daily via abdominal massage) reduced participants’ reported menstrual pain symptoms and duration of pain.36 In a meta-analysis of 6 studies, topical abdominal application of EO (mainly lavender with or without other oils) with massage showed superiority over massage with placebo oils in reducing menstrual pain.37 A reduction in pain, mood symptoms, and fatigue in women with premenstrual symptoms was seen in an RCT of 77 patients using 3 drops of inhaled lavender EO.47

Labor. There is limited evidence for the use of EOs during labor. In an RCT of 104 women, patient-selected diffused EOs, including lavender, rose geranium, citrus, or jasmine, were found to help lower pain scores during the latent and early active phase of labor. There were no differences in labor augmentation, length of labor, perinatal outcomes, or need for additional pain medication.48

Other uses

Antimicrobial support. Some common EOs that have demonstrated antimicrobial properties are oregano, thyme, clove, lavender, clary sage, garlic, and cinnamon.49,50 Topical lemongrass and tea tree EOs have shown some degree of efficacy as an alternative treatment for acne, decolonization of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, and superficial fungal infections.51 Support for an oral mixture of EOs labeled Myrtol (containing eucalyptus, citrus myrtle, and lavender) for viral acute bronchitis and sinusitis was found in a review of 7 studies.52 More research needs to be done before clear recommendations can be made on the use of EOs as antimicrobials, but the current data are encouraging.

Insect repellent. Reviews of the insect-repellent properties of EOs have shown promise and are in the public’s interest due to increasing awareness of the potential health and environmental hazards of synthetic repellents.53 Individual compounds present in EOs such as citronella/lemongrass, basil, and eucalyptus species demonstrate high repellent activity.54 Since EOs require frequent reapplication for efficacy due to their highly volatile nature, scientists are currently developing a means to prolong their protection time through cream-based formulations.55

The bottom line

Because of the ubiquity of EOs, family physicians will undoubtedly be asked about them by patients, and it would be beneficial to feel comfortable discussing their most common uses. For most adult patients, the topical and periodic inhaled usage of EOs is generally safe.56

There is existing evidence of efficacy for a number of EOs, most strongly for lavender and peppermint. Future research into EOs should include higher-powered and higher-quality studies in order to provide more conclusive evidence regarding the continued use of EOs for many common conditions. More evidence-based information on dosing, application/use regimens, and safety in long-term use also will help providers better instruct patients on how to utilize EOs effectively and safely.

CORRESPONDENCE

Pooja Amy Shah, MD, Columbia University College of Physicians & Surgeons, 610 West 158th Street, New York, NY 10032; [email protected]

1. Butnariu M, Sarac I. Essential oils from plants. J Biotechnol Biomed Sci. 2018;1:35-43. doi: 10.14302/issn.2576-6694.jbbs-18-2489

2. Singh B, Sellam P, Majumder, J, et al. Floral essential oils : importance and uses for mankind. HortFlora Res Spectr. 2014;3:7-13. www.academia.edu/6707801/Floral_essential_oils_Importance_and_uses_for_mankind

3. Posadzki P, Alotaibi A, Ernst E. Adverse effects of aromatherapy: a systematic review of case reports and case series. Int J Risk Saf Med. 2012;24:147-161. doi: 10.3233/JRS-2012-0568

4. Sharmeen JB, Mahomoodally FM, Zengin G, et al. Essential oils as natural sources of fragrance compounds for cosmetics and cosmeceuticals. Molecules. 2021;26:666. doi: 10.3390/molecules26030666

5. Henley DV, Lipson N, Korach KS, et al. Prepubertal gynecomastia linked to lavender and tea tree oils. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:479-485. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa064725

6. Nematollahi N, Weinberg JL, Flattery J, et al. Volatile chemical emissions from essential oils with therapeutic claims. Air Qual Atmosphere Health. 2021;14:365-369. doi: 10.1007/s11869-020-00941-4

7. Balekian D, Long A. Essential oil diffusers and asthma. Published February 24, 2020. Accessed September 22, 2023. www.aaaai.org/Allergist-Resources/Ask-the-Expert/Answers/Old-Ask-the-Experts/oil-diffusers-asthma

8. Aura Cacia. Quality. Accessed September 22, 2023. www.auracacia.com/quality

9. Now. Essential oil identity & purity testing. Accessed September 22, 2023. www.nowfoods.com/quality-safety/essential-oil-identity-purity-testing

10. Aura Cacia. GCMS documents. Accessed September 22, 2023. www.auracacia.com/aura-cacia-gcms-documents

11. Lopresti AL, Smith SJ, Drummond PD. Herbal treatments for migraine: a systematic review of randomised-controlled studies. Phytother Res. 2020;34:2493-2517. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6701

12. Niazi M, Hashempur MH, Taghizadeh M, et al. Efficacy of topical Rose (Rosa damascena Mill.) oil for migraine headache: A randomized double-blinded placebo-controlled cross-over trial. Complement Ther Med. 2017;34:35-41. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim. 2017.07.009

13. Rafieian-Kopaei M, Hasanpour-Dehkordi A, Lorigooini Z, et al. Comparing the effect of intranasal lidocaine 4% with peppermint essential oil drop 1.5% on migraine attacks: a double-blind clinical trial. Int J Prev Med. 2019;10:121. doi: 10.4103/ijpvm.IJPVM_530_17

14. Göbel H, Fresenius J, Heinze A, et al. [Effectiveness of Oleum menthae piperitae and paracetamol in therapy of headache of the tension type]. Nervenarzt. 1996;67:672-681. doi: 10.1007/s001150050040

15. Hunt R, Dienemann J, Norton HJ, et al. Aromatherapy as treatment for postoperative nausea: a randomized trial. Anesth Analg. 2013;117:597-604. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e31824a0b1c

16. Maghami M, Afazel MR, Azizi-Fini I, et al. The effect of aromatherapy with peppermint essential oil on nausea and vomiting after cardiac surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2020;40:101199. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2020.101199

17. Hills JM, Aaronson PI. The mechanism of action of peppermint oil on gastrointestinal smooth muscle. An analysis using patch clamp electrophysiology and isolated tissue pharmacology in rabbit and guinea pig. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:55-65. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90459-x

18. Alammar N, Wang L, Saberi B, et al. The impact of peppermint oil on the irritable bowel syndrome: a meta-analysis of the pooled clinical data. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2019;19:21. doi: 10.1186/s12906-018-2409-0

19. Cash BD, Epstein MS, Shah SM. A novel delivery system of peppermint oil is an effective therapy for irritable bowel syndrome symptoms. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61:560-571. doi: 10.1007/s10620-015-3858-7

20. Weerts ZZRM, Masclee AAM, Witteman BJM, et al. Efficacy and safety of peppermint oil in a randomized, double-blind trial of patients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:123-136. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.08.026

21. Ma X, Yue ZQ, Gong ZQ, et al. The effect of diaphragmatic breathing on attention, negative affect and stress in healthy adults. Front Psychol. 2017;8:874. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00874

22. Cabral P, Meyer HB, Ames D. Effectiveness of yoga therapy as a complementary treatment for major psychiatric disorders: a meta-analysis. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. Published July 7, 2011. doi: 10.4088/PCC.10r01068

23. Donelli D, Antonelli M, Bellinazzi C, et ala. Effects of lavender on anxiety: systematic review and meta-analysis. Phytomedicine Int J Phytother Phytopharm. 2019;65:153099. doi: 10.1016/j.phymed.2019.153099

24. Koulivand PH, Khaleghi Ghadiri M, Gorji A. Lavender and the nervous system. Evid Based Complement Alternat Med. 2013;2013:1-10. doi: 10.1155/2013/681304

25. Kang HJ, Nam ES, Lee Y, et al. How strong is the evidence for the anxiolytic efficacy of lavender? Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Asian Nurs Res. 2019;13:295-305. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2019.11.003

26. Barão Paixão VL, Freire de Carvalho J. Essential oil therapy in rheumatic diseases: a systematic review. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2021;43:101391. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2021.101391

27. Yasa Ozturk G, Bashan I. The effect of aromatherapy with lavender oil on the health-related quality of life in patients with fibromyalgia. J Food Qual. 2021;2021:1-5. doi: 10.1155/2021/9938630

28. Ko GD, Hum A, Traitses G, et al. Effects of topical O24 essential oils on patients with fibromyalgia syndrome: a randomized, placebo controlled pilot study. J Musculoskelet Pain. 2007;15:11-19. doi: 10.1300/J094v15n01_03

29. Lillehei AS, Halcon LL. A systematic review of the effect of inhaled essential oils on sleep. J Altern Complement Med. 2014;20:441-451. doi: 10.1089/acm.2013.0311

30. Cheong MJ, Kim S, Kim JS, et al. A systematic literature review and meta-analysis of the clinical effects of aroma inhalation therapy on sleep problems. Medicine (Baltimore). 2021;100:e24652. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000024652

31. Afrasiabian F, Mirabzadeh Ardakani M, Rahmani K, et al. Aloysia citriodora Paláu (lemon verbena) for insomnia patients: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial of efficacy and safety. Phytother Res PTR. 2019;33:350-359. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6228

32. Lee M, Lim S, Song JA, et al. The effects of aromatherapy essential oil inhalation on stress, sleep quality and immunity in healthy adults: randomized controlled trial. Eur J Integr Med. 2017;12:79-86. doi: 10.1016/j.eujim.2017.04.009

33. Nasiri Lari Z, Hajimonfarednejad M, Riasatian M, et al. Efficacy of inhaled Lavandula angustifolia Mill. Essential oil on sleep quality, quality of life and metabolic control in patients with diabetes mellitus type II and insomnia. J Ethnopharmacol. 2020;251:112560. doi: 10.1016/j.jep.2020.112560

34. McDonnell B, Newcomb P. Trial of essential oils to improve sleep for patients in cardiac rehabilitation. J Altern Complement Med N Y N. 2019;25:1193-1199. doi: 10.1089/acm.2019.0222

35. Song JA, Lee MK, Min E, et al. Effects of aromatherapy on dysmenorrhea: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Nurs Stud. 2018;84:1-11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2018.01.016

36. Ou MC, Hsu TF, Lai AC, et al. Pain relief assessment by aromatic essential oil massage on outpatients with primary dysmenorrhea: a randomized, double-blind clinical trial: PD pain relief by aromatic oil massage. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2012;38:817-822. doi: 10.1111/j.1447-0756.2011.01802.x

37. Sut N, Kahyaoglu-Sut H. Effect of aromatherapy massage on pain in primary dysmenorrhea: a meta-analysis. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2017;27:5-10. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2017.01.001

38. Keyhanmehr AS, Kolouri S, Heydarirad G, et al. Aromatherapy for the management of cancer complications: a narrative review. Complement Ther Clin Pract. 2018;31:175-180. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2018.02.009

39. Sriningsih I, Elisa E, Lestari KP. Aromatherapy ginger use in patients with nausea & vomiting on post cervical cancer chemotherapy. KEMAS J Kesehat Masy. 2017;13:59-68. doi: 10.15294/kemas.v13i1.5367

40. Lua PL, Salihah N, Mazlan N. Effects of inhaled ginger aromatherapy on chemotherapy-induced nausea and vomiting and health-related quality of life in women with breast cancer. Complement Ther Med. 2015;23:396-404. doi: 10.1016/j.ctim.2015.03.009