User login

Recurrent pleural effusions and a normal cardiac CT

CASE An 84-year-old man was admitted to our family medicine inpatient service with increasing weakness, fatigue, nausea, jaundice, and anorexia after undergoing thoracentesis for recurrent large right-sided pleural effusion twice within the past 6 weeks. The patient had no fever, chills, night sweats, chest pain, or chronic cough.

His past medical history included coronary artery disease and hyperlipidemia, and he had undergone coronary artery bypass grafting 6 years prior to this admission.

Initial vital signs included a blood pressure of 116/68 mm hg and a pulse rate of 78 beats per minute. physical examination revealed a thin but otherwise active and functional man, with the presence of scleral icterus and a 2/6 systolic murmur that was loudest at the left upper sternal border, with no pericardial knocks or rubs. There was no jugular venous distension. The patient had decreased breath sounds at the right base, but no appreciable rales, rhonchi, or wheezes, and an enlarged liver with an irregular edge approximately 7 cm below the costal margin. he had bilateral trace pitting edema of the lower extremities and an erythematous chronic venous stasis ulcer on his left lower leg that was being treated with sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim and rifampin.

Laboratory findings included a sodium level of 130 mEq/L; creatinine, 1.6 mg/dL; total bilirubin, 4.2 mg/dL; and an international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.6, with an otherwise normal liver profile. pleural fluid was transudative by light’s criteria, with negative pleural fluid cultures.

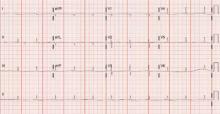

A chest x-ray showed right-sided airspace disease, with an associated small effusion (FIGURE 1), and an electrocardiogram (EKG) revealed a right axis deviation with flipped T waves in V3-V6 (FIGURE 2). A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest performed 2 months prior to admission revealed a small right pleural effusion, moderate emphysema, and pleural plaques. A transthoracic echocardiogram performed a week earlier was significant for a normal ejection fraction without pericardial thickening, and mild dilation of the left and right atria and the right ventricle.

Our patient had recurrent transudative pleural effusions with no history of congestive heart failure, a normal thyroid-stimulating hormone, no signs of nephrotic syndrome, no risk factors for lung cancer, and a presentation that was not consistent with an acute pulmonary embolus. he had jaundice, but no risk factors for cirrhosis. A comprehensive hepatology consult suggested that the jaundice was associated with recent rifampin use, along with hepatic congestion likely due to cardiac etiology.

The patient also had a documented history of constrictive pericarditis. Although a cardiac CT scan 15 months prior to his hospital admission showed normal pericardial thickness, constrictive pericarditis remained high on our differential.

To further evaluate the patient’s cardiac function, a cardiologist performed a right-sided cardiac catheterization. in constrictive pericarditis, equalization of end-diastolic pressures occurs due to limitation of the total volume of the ventricles by a rigid pericardium. in our patient, these pressures did not equalize. his right and left ventricular pressure tracings did, however, have the classic square root sign often seen in constrictive pericarditis (FIGURE 3). This “dip and plateau” is the result of rapid filling of the ventricles during early diastole, with the inflexible pericardium causing an abrupt halt in ventricular filling.1

We considered restrictive cardiomyopathy in the differential, too, but the signs and symptoms weren’t a perfect fit there, either. equalization of left and right ventricular end-diastolic pressures in cardiac catheterization is usually not seen in restrictive cardiomyopathy, but neither is the square-root sign evident on ventricular pressure monitors.1

FIGURE 1

X-ray shows right-sided airspace disease

FIGURE 2

Right axis deviation with flipped T waves

FIGURE 3

Classic square root sign

WHAT IS THE MOST LIKELY EXPLANATION FOR HIS CONDITION?

Constrictive pericarditis

On the advice of a cardiologist who specializes in advanced cardiac imaging, our patient underwent tissue Doppler velocity echocardiography—a diagnostic test that provides evidence of a diseased myocardium (as in restrictive cardiomyopathy), as well as changes in diastolic blood flow that differentiate constrictive pericarditis from restrictive cardiomyopathy. Our patient’s tissue Doppler velocity echocardiogram revealed a normal myocardium with an abrupt cessation of early left ventricular filling, consistent with constrictive pericarditis. Along with his clinical presentation and history, this test was conclusive enough to diagnose constrictive pericarditis.

Making the diagnosis in more “typical” cases

Symptoms of constrictive pericarditis include fluid overload (eg, recurrent pleural effusions2-4) hepatic dysfunction, and peripheral edema. Studies show that 44% to 54% of patients with constrictive pericarditis present with pleural effusions;5 chest pain and dyspnea are other common symptoms.6 Past medical history is also important, considering the 3 most common risks for constrictive pericarditis: cardiac surgery, pericarditis, and irradiation of the mediastinum (TABLE).7

Typical physical exam findings in patients with constrictive pericarditis include an elevated jugular venous pressure, third spacing of fluids, a pericardial knock, and Kussmaul’s sign. Our patient had third spacing of fluids, including mild peripheral edema and the recurrent effusions as noted, as well as signs of hepatic dysfunction that were initially attributed to his rifampin use. While these symptoms raise the suspicion of constrictive pericarditis, none is specific to that condition alone.

Studies that help in the diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis include chest x-ray, cardiac CT, echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and cardiac catheterization. EKG has no specific findings, but cardiac arrhythmias (eg, atrial fibrillation) are common.8 Pericardial thickening on cardiac CT scan is a definitive but not universal finding; in a Mayo Clinic study, such thickening was not evident in 26 of 143 patients with confirmed constrictive pericarditis.8 Cardiac MRI has been shown to have 88% sensitivity and 100% specificity,9 but will miss up to 18% of patients with constrictive pericarditis.8

Differentiating between restriction and constriction. It can be difficult to distinguish between constrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy. Although these conditions can present in a similar manner, they require different modes of treatment. Laboratory testing, cardiac catheterization, and tissue Doppler velocity echocardiography (which we relied on) can help to distinguish between them.

TABLE

Causes of constrictive pericarditis7

| More common |

|---|

| Idiopathic Postcardiac surgery (coronary artery bypass grafting, valve replacement) Postradiation therapy (eg, for breast cancer, lymphoma) Viral (pericarditis) |

| Less common |

| Asbestosis Cancer and myeloproliferative disorders Connective tissue disorders (rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus) Adverse drug reaction Infection (tuberculosis, fungal) Sarcoidosis Trauma Uremia |

Pericardiectomy is the treatment of choice

Pericardiectomy, the optimal treatment for most patients with constrictive pericarditis, carries a 30-day perioperative mortality of approximately 6%.5,7 Patients with minimal symptoms can be monitored for up to 2 months, but only 17% of cases are self-limited.6 Patients with end-stage disease or those who have radiation-induced constrictive pericarditis experience poor surgical outcomes, and may be better served by medical management.7

In light of our patient’s excellent baseline functional status, clinical presentation, and Doppler test results, a cardiothoracic surgeon performed a pericardiectomy. His symptoms improved postoperatively, and he has had no further pleural effusions. The patient’s fatigue, anorexia, weight loss, and dyspnea fully resolved, as well.

- Include constrictive pericarditis in the differential diagnosis of patients with recurrent pleural effusions, an important presenting symptom in 44% to 54% of patients with this condition.

- Consider multiple testing modalities to arrive at a diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis, including cardiac CT or MRI, tissue Doppler echocardiography, and cardiac catheterization.

- Do not rule out constrictive pericarditis if pericardial thickening is not found on cardiac CT scan; in 1 study, this finding was not present in 18% of patients with a confirmed diagnosis.

CORRESPONDENCE Jeffrey S. Morgeson, MD; 2123 Auburn Avenue, 340 MOB, Cincinnati, OH 45219; [email protected]

1. Maisch B, Seferovic PM, Ristic AD, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases executive summary; The Task force on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:587-610.

2. Akhter MW, Nuño IN, Rahimtoola SH. Constrictive pericarditis masquerading as chronic idiopathic pleural effusion: importance of physical examination. Am J Med. 2006;119:e1-e4.

3. Ramar K, Daniels CA. Constrictive pericarditis presenting as unexplained dyspnea with recurrent pleural effusion. Respir Care. 2008;53:912-915.

4. Sadikot RT, Fredi JL, Light RW. A 43-year-old man with a large recurrent right-sided pleural effusion. Diagnosis: constrictive pericarditis. Chest. 2000;117:1191-1194.

5. Bertog SC, Thambidorai SK, Parakh K, et al. Constrictive pericarditis: etiology and cause-specific survival after pericardiectomy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1445-1452.

6. Haley JH, Tajik AJ, Danielson GK, et al. Transient constrictive pericarditis: causes and natural history. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:271-275.

7. Ling LH, Oh JK, Schaff HV, et al. Constrictive pericarditis in the modern era: evolving clinical spectrum and impact on outcome after pericardiectomy. Circulation. 1999;100:1380-1386.

8. Talreja DP, Edwards WD, Danielson GK, et al. Constrictive pericarditis in 26 patients with histologically normal pericardial thickness. Circulation. 2003;108:1852-1857.

9. Masui T, Finck S, Higgins CB. Constrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology. 1992;182:369-373.

CASE An 84-year-old man was admitted to our family medicine inpatient service with increasing weakness, fatigue, nausea, jaundice, and anorexia after undergoing thoracentesis for recurrent large right-sided pleural effusion twice within the past 6 weeks. The patient had no fever, chills, night sweats, chest pain, or chronic cough.

His past medical history included coronary artery disease and hyperlipidemia, and he had undergone coronary artery bypass grafting 6 years prior to this admission.

Initial vital signs included a blood pressure of 116/68 mm hg and a pulse rate of 78 beats per minute. physical examination revealed a thin but otherwise active and functional man, with the presence of scleral icterus and a 2/6 systolic murmur that was loudest at the left upper sternal border, with no pericardial knocks or rubs. There was no jugular venous distension. The patient had decreased breath sounds at the right base, but no appreciable rales, rhonchi, or wheezes, and an enlarged liver with an irregular edge approximately 7 cm below the costal margin. he had bilateral trace pitting edema of the lower extremities and an erythematous chronic venous stasis ulcer on his left lower leg that was being treated with sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim and rifampin.

Laboratory findings included a sodium level of 130 mEq/L; creatinine, 1.6 mg/dL; total bilirubin, 4.2 mg/dL; and an international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.6, with an otherwise normal liver profile. pleural fluid was transudative by light’s criteria, with negative pleural fluid cultures.

A chest x-ray showed right-sided airspace disease, with an associated small effusion (FIGURE 1), and an electrocardiogram (EKG) revealed a right axis deviation with flipped T waves in V3-V6 (FIGURE 2). A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest performed 2 months prior to admission revealed a small right pleural effusion, moderate emphysema, and pleural plaques. A transthoracic echocardiogram performed a week earlier was significant for a normal ejection fraction without pericardial thickening, and mild dilation of the left and right atria and the right ventricle.

Our patient had recurrent transudative pleural effusions with no history of congestive heart failure, a normal thyroid-stimulating hormone, no signs of nephrotic syndrome, no risk factors for lung cancer, and a presentation that was not consistent with an acute pulmonary embolus. he had jaundice, but no risk factors for cirrhosis. A comprehensive hepatology consult suggested that the jaundice was associated with recent rifampin use, along with hepatic congestion likely due to cardiac etiology.

The patient also had a documented history of constrictive pericarditis. Although a cardiac CT scan 15 months prior to his hospital admission showed normal pericardial thickness, constrictive pericarditis remained high on our differential.

To further evaluate the patient’s cardiac function, a cardiologist performed a right-sided cardiac catheterization. in constrictive pericarditis, equalization of end-diastolic pressures occurs due to limitation of the total volume of the ventricles by a rigid pericardium. in our patient, these pressures did not equalize. his right and left ventricular pressure tracings did, however, have the classic square root sign often seen in constrictive pericarditis (FIGURE 3). This “dip and plateau” is the result of rapid filling of the ventricles during early diastole, with the inflexible pericardium causing an abrupt halt in ventricular filling.1

We considered restrictive cardiomyopathy in the differential, too, but the signs and symptoms weren’t a perfect fit there, either. equalization of left and right ventricular end-diastolic pressures in cardiac catheterization is usually not seen in restrictive cardiomyopathy, but neither is the square-root sign evident on ventricular pressure monitors.1

FIGURE 1

X-ray shows right-sided airspace disease

FIGURE 2

Right axis deviation with flipped T waves

FIGURE 3

Classic square root sign

WHAT IS THE MOST LIKELY EXPLANATION FOR HIS CONDITION?

Constrictive pericarditis

On the advice of a cardiologist who specializes in advanced cardiac imaging, our patient underwent tissue Doppler velocity echocardiography—a diagnostic test that provides evidence of a diseased myocardium (as in restrictive cardiomyopathy), as well as changes in diastolic blood flow that differentiate constrictive pericarditis from restrictive cardiomyopathy. Our patient’s tissue Doppler velocity echocardiogram revealed a normal myocardium with an abrupt cessation of early left ventricular filling, consistent with constrictive pericarditis. Along with his clinical presentation and history, this test was conclusive enough to diagnose constrictive pericarditis.

Making the diagnosis in more “typical” cases

Symptoms of constrictive pericarditis include fluid overload (eg, recurrent pleural effusions2-4) hepatic dysfunction, and peripheral edema. Studies show that 44% to 54% of patients with constrictive pericarditis present with pleural effusions;5 chest pain and dyspnea are other common symptoms.6 Past medical history is also important, considering the 3 most common risks for constrictive pericarditis: cardiac surgery, pericarditis, and irradiation of the mediastinum (TABLE).7

Typical physical exam findings in patients with constrictive pericarditis include an elevated jugular venous pressure, third spacing of fluids, a pericardial knock, and Kussmaul’s sign. Our patient had third spacing of fluids, including mild peripheral edema and the recurrent effusions as noted, as well as signs of hepatic dysfunction that were initially attributed to his rifampin use. While these symptoms raise the suspicion of constrictive pericarditis, none is specific to that condition alone.

Studies that help in the diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis include chest x-ray, cardiac CT, echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and cardiac catheterization. EKG has no specific findings, but cardiac arrhythmias (eg, atrial fibrillation) are common.8 Pericardial thickening on cardiac CT scan is a definitive but not universal finding; in a Mayo Clinic study, such thickening was not evident in 26 of 143 patients with confirmed constrictive pericarditis.8 Cardiac MRI has been shown to have 88% sensitivity and 100% specificity,9 but will miss up to 18% of patients with constrictive pericarditis.8

Differentiating between restriction and constriction. It can be difficult to distinguish between constrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy. Although these conditions can present in a similar manner, they require different modes of treatment. Laboratory testing, cardiac catheterization, and tissue Doppler velocity echocardiography (which we relied on) can help to distinguish between them.

TABLE

Causes of constrictive pericarditis7

| More common |

|---|

| Idiopathic Postcardiac surgery (coronary artery bypass grafting, valve replacement) Postradiation therapy (eg, for breast cancer, lymphoma) Viral (pericarditis) |

| Less common |

| Asbestosis Cancer and myeloproliferative disorders Connective tissue disorders (rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus) Adverse drug reaction Infection (tuberculosis, fungal) Sarcoidosis Trauma Uremia |

Pericardiectomy is the treatment of choice

Pericardiectomy, the optimal treatment for most patients with constrictive pericarditis, carries a 30-day perioperative mortality of approximately 6%.5,7 Patients with minimal symptoms can be monitored for up to 2 months, but only 17% of cases are self-limited.6 Patients with end-stage disease or those who have radiation-induced constrictive pericarditis experience poor surgical outcomes, and may be better served by medical management.7

In light of our patient’s excellent baseline functional status, clinical presentation, and Doppler test results, a cardiothoracic surgeon performed a pericardiectomy. His symptoms improved postoperatively, and he has had no further pleural effusions. The patient’s fatigue, anorexia, weight loss, and dyspnea fully resolved, as well.

- Include constrictive pericarditis in the differential diagnosis of patients with recurrent pleural effusions, an important presenting symptom in 44% to 54% of patients with this condition.

- Consider multiple testing modalities to arrive at a diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis, including cardiac CT or MRI, tissue Doppler echocardiography, and cardiac catheterization.

- Do not rule out constrictive pericarditis if pericardial thickening is not found on cardiac CT scan; in 1 study, this finding was not present in 18% of patients with a confirmed diagnosis.

CORRESPONDENCE Jeffrey S. Morgeson, MD; 2123 Auburn Avenue, 340 MOB, Cincinnati, OH 45219; [email protected]

CASE An 84-year-old man was admitted to our family medicine inpatient service with increasing weakness, fatigue, nausea, jaundice, and anorexia after undergoing thoracentesis for recurrent large right-sided pleural effusion twice within the past 6 weeks. The patient had no fever, chills, night sweats, chest pain, or chronic cough.

His past medical history included coronary artery disease and hyperlipidemia, and he had undergone coronary artery bypass grafting 6 years prior to this admission.

Initial vital signs included a blood pressure of 116/68 mm hg and a pulse rate of 78 beats per minute. physical examination revealed a thin but otherwise active and functional man, with the presence of scleral icterus and a 2/6 systolic murmur that was loudest at the left upper sternal border, with no pericardial knocks or rubs. There was no jugular venous distension. The patient had decreased breath sounds at the right base, but no appreciable rales, rhonchi, or wheezes, and an enlarged liver with an irregular edge approximately 7 cm below the costal margin. he had bilateral trace pitting edema of the lower extremities and an erythematous chronic venous stasis ulcer on his left lower leg that was being treated with sulfamethoxazole and trimethoprim and rifampin.

Laboratory findings included a sodium level of 130 mEq/L; creatinine, 1.6 mg/dL; total bilirubin, 4.2 mg/dL; and an international normalized ratio (INR) of 1.6, with an otherwise normal liver profile. pleural fluid was transudative by light’s criteria, with negative pleural fluid cultures.

A chest x-ray showed right-sided airspace disease, with an associated small effusion (FIGURE 1), and an electrocardiogram (EKG) revealed a right axis deviation with flipped T waves in V3-V6 (FIGURE 2). A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest performed 2 months prior to admission revealed a small right pleural effusion, moderate emphysema, and pleural plaques. A transthoracic echocardiogram performed a week earlier was significant for a normal ejection fraction without pericardial thickening, and mild dilation of the left and right atria and the right ventricle.

Our patient had recurrent transudative pleural effusions with no history of congestive heart failure, a normal thyroid-stimulating hormone, no signs of nephrotic syndrome, no risk factors for lung cancer, and a presentation that was not consistent with an acute pulmonary embolus. he had jaundice, but no risk factors for cirrhosis. A comprehensive hepatology consult suggested that the jaundice was associated with recent rifampin use, along with hepatic congestion likely due to cardiac etiology.

The patient also had a documented history of constrictive pericarditis. Although a cardiac CT scan 15 months prior to his hospital admission showed normal pericardial thickness, constrictive pericarditis remained high on our differential.

To further evaluate the patient’s cardiac function, a cardiologist performed a right-sided cardiac catheterization. in constrictive pericarditis, equalization of end-diastolic pressures occurs due to limitation of the total volume of the ventricles by a rigid pericardium. in our patient, these pressures did not equalize. his right and left ventricular pressure tracings did, however, have the classic square root sign often seen in constrictive pericarditis (FIGURE 3). This “dip and plateau” is the result of rapid filling of the ventricles during early diastole, with the inflexible pericardium causing an abrupt halt in ventricular filling.1

We considered restrictive cardiomyopathy in the differential, too, but the signs and symptoms weren’t a perfect fit there, either. equalization of left and right ventricular end-diastolic pressures in cardiac catheterization is usually not seen in restrictive cardiomyopathy, but neither is the square-root sign evident on ventricular pressure monitors.1

FIGURE 1

X-ray shows right-sided airspace disease

FIGURE 2

Right axis deviation with flipped T waves

FIGURE 3

Classic square root sign

WHAT IS THE MOST LIKELY EXPLANATION FOR HIS CONDITION?

Constrictive pericarditis

On the advice of a cardiologist who specializes in advanced cardiac imaging, our patient underwent tissue Doppler velocity echocardiography—a diagnostic test that provides evidence of a diseased myocardium (as in restrictive cardiomyopathy), as well as changes in diastolic blood flow that differentiate constrictive pericarditis from restrictive cardiomyopathy. Our patient’s tissue Doppler velocity echocardiogram revealed a normal myocardium with an abrupt cessation of early left ventricular filling, consistent with constrictive pericarditis. Along with his clinical presentation and history, this test was conclusive enough to diagnose constrictive pericarditis.

Making the diagnosis in more “typical” cases

Symptoms of constrictive pericarditis include fluid overload (eg, recurrent pleural effusions2-4) hepatic dysfunction, and peripheral edema. Studies show that 44% to 54% of patients with constrictive pericarditis present with pleural effusions;5 chest pain and dyspnea are other common symptoms.6 Past medical history is also important, considering the 3 most common risks for constrictive pericarditis: cardiac surgery, pericarditis, and irradiation of the mediastinum (TABLE).7

Typical physical exam findings in patients with constrictive pericarditis include an elevated jugular venous pressure, third spacing of fluids, a pericardial knock, and Kussmaul’s sign. Our patient had third spacing of fluids, including mild peripheral edema and the recurrent effusions as noted, as well as signs of hepatic dysfunction that were initially attributed to his rifampin use. While these symptoms raise the suspicion of constrictive pericarditis, none is specific to that condition alone.

Studies that help in the diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis include chest x-ray, cardiac CT, echocardiography, cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and cardiac catheterization. EKG has no specific findings, but cardiac arrhythmias (eg, atrial fibrillation) are common.8 Pericardial thickening on cardiac CT scan is a definitive but not universal finding; in a Mayo Clinic study, such thickening was not evident in 26 of 143 patients with confirmed constrictive pericarditis.8 Cardiac MRI has been shown to have 88% sensitivity and 100% specificity,9 but will miss up to 18% of patients with constrictive pericarditis.8

Differentiating between restriction and constriction. It can be difficult to distinguish between constrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy. Although these conditions can present in a similar manner, they require different modes of treatment. Laboratory testing, cardiac catheterization, and tissue Doppler velocity echocardiography (which we relied on) can help to distinguish between them.

TABLE

Causes of constrictive pericarditis7

| More common |

|---|

| Idiopathic Postcardiac surgery (coronary artery bypass grafting, valve replacement) Postradiation therapy (eg, for breast cancer, lymphoma) Viral (pericarditis) |

| Less common |

| Asbestosis Cancer and myeloproliferative disorders Connective tissue disorders (rheumatoid arthritis, systemic lupus erythematosus) Adverse drug reaction Infection (tuberculosis, fungal) Sarcoidosis Trauma Uremia |

Pericardiectomy is the treatment of choice

Pericardiectomy, the optimal treatment for most patients with constrictive pericarditis, carries a 30-day perioperative mortality of approximately 6%.5,7 Patients with minimal symptoms can be monitored for up to 2 months, but only 17% of cases are self-limited.6 Patients with end-stage disease or those who have radiation-induced constrictive pericarditis experience poor surgical outcomes, and may be better served by medical management.7

In light of our patient’s excellent baseline functional status, clinical presentation, and Doppler test results, a cardiothoracic surgeon performed a pericardiectomy. His symptoms improved postoperatively, and he has had no further pleural effusions. The patient’s fatigue, anorexia, weight loss, and dyspnea fully resolved, as well.

- Include constrictive pericarditis in the differential diagnosis of patients with recurrent pleural effusions, an important presenting symptom in 44% to 54% of patients with this condition.

- Consider multiple testing modalities to arrive at a diagnosis of constrictive pericarditis, including cardiac CT or MRI, tissue Doppler echocardiography, and cardiac catheterization.

- Do not rule out constrictive pericarditis if pericardial thickening is not found on cardiac CT scan; in 1 study, this finding was not present in 18% of patients with a confirmed diagnosis.

CORRESPONDENCE Jeffrey S. Morgeson, MD; 2123 Auburn Avenue, 340 MOB, Cincinnati, OH 45219; [email protected]

1. Maisch B, Seferovic PM, Ristic AD, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases executive summary; The Task force on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:587-610.

2. Akhter MW, Nuño IN, Rahimtoola SH. Constrictive pericarditis masquerading as chronic idiopathic pleural effusion: importance of physical examination. Am J Med. 2006;119:e1-e4.

3. Ramar K, Daniels CA. Constrictive pericarditis presenting as unexplained dyspnea with recurrent pleural effusion. Respir Care. 2008;53:912-915.

4. Sadikot RT, Fredi JL, Light RW. A 43-year-old man with a large recurrent right-sided pleural effusion. Diagnosis: constrictive pericarditis. Chest. 2000;117:1191-1194.

5. Bertog SC, Thambidorai SK, Parakh K, et al. Constrictive pericarditis: etiology and cause-specific survival after pericardiectomy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1445-1452.

6. Haley JH, Tajik AJ, Danielson GK, et al. Transient constrictive pericarditis: causes and natural history. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:271-275.

7. Ling LH, Oh JK, Schaff HV, et al. Constrictive pericarditis in the modern era: evolving clinical spectrum and impact on outcome after pericardiectomy. Circulation. 1999;100:1380-1386.

8. Talreja DP, Edwards WD, Danielson GK, et al. Constrictive pericarditis in 26 patients with histologically normal pericardial thickness. Circulation. 2003;108:1852-1857.

9. Masui T, Finck S, Higgins CB. Constrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology. 1992;182:369-373.

1. Maisch B, Seferovic PM, Ristic AD, et al. Guidelines on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases executive summary; The Task force on the diagnosis and management of pericardial diseases of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:587-610.

2. Akhter MW, Nuño IN, Rahimtoola SH. Constrictive pericarditis masquerading as chronic idiopathic pleural effusion: importance of physical examination. Am J Med. 2006;119:e1-e4.

3. Ramar K, Daniels CA. Constrictive pericarditis presenting as unexplained dyspnea with recurrent pleural effusion. Respir Care. 2008;53:912-915.

4. Sadikot RT, Fredi JL, Light RW. A 43-year-old man with a large recurrent right-sided pleural effusion. Diagnosis: constrictive pericarditis. Chest. 2000;117:1191-1194.

5. Bertog SC, Thambidorai SK, Parakh K, et al. Constrictive pericarditis: etiology and cause-specific survival after pericardiectomy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1445-1452.

6. Haley JH, Tajik AJ, Danielson GK, et al. Transient constrictive pericarditis: causes and natural history. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:271-275.

7. Ling LH, Oh JK, Schaff HV, et al. Constrictive pericarditis in the modern era: evolving clinical spectrum and impact on outcome after pericardiectomy. Circulation. 1999;100:1380-1386.

8. Talreja DP, Edwards WD, Danielson GK, et al. Constrictive pericarditis in 26 patients with histologically normal pericardial thickness. Circulation. 2003;108:1852-1857.

9. Masui T, Finck S, Higgins CB. Constrictive pericarditis and restrictive cardiomyopathy: evaluation with MR imaging. Radiology. 1992;182:369-373.