User login

A 10-year-old boy with ‘voices in my head’: Is it a psychotic disorder?

CASE Auditory hallucinations?

M, age 10, has had multiple visits to the pediatric emergency department (PED) with the chief concern of excessive urinary frequency. At each visit, the medical workup has been negative and he was discharged home. After a few months, M’s parents bring their son back to the PED because he reports hearing “voices in my head” and “feeling tense and scared.” When these feelings become too overwhelming, M stops eating and experiences substantial fear and anxiety that require his mother’s repeated reassurances. M’s mother reports that 2 weeks before his most recent PED visit, he became increasingly anxious and disturbed, and said he was afraid most of the time, and worried about the safety of his family for no apparent reason.

The psychiatrist evaluates M in the PED and diagnoses him with unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder based on his persistent report of auditory and tactile hallucinations, including hearing a voice of a man telling him he was going to choke on his food and feeling someone touch his arm to soothe him during his anxious moments. M does not meet criteria for acute inpatient hospitalization, and is discharged home with referral to follow-up at our child and adolescent psychiatry outpatient clinic.

On subsequent evaluation in our clinic, M reports most of the same about his experience hearing “voices in my head” that repeatedly suggest “I might choke on my food and end up seriously ill in the hospital.” He started to hear the “voices” after he witnessed his sister choke while eating a few days earlier. He also mentions that the “voices” tell him “you have to use the restroom.” As a result, he uses the restroom several times before leaving for home and is frequently late for school. His parents accommodate his behavior—his mother allows him to use the bathroom multiple times, and his father overlooks the behavior as part of school anxiety.

At school, his teacher reports a concern for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) based on M’s continuous inattentiveness in class and dropping grades. He asks for bathroom breaks up to 15 times a day, which disrupts his class work.

These behaviors have led to a gradual 1-year decline in his overall functioning, including difficulty at school for requesting too many bathroom breaks; having to repeat the 3rd grade; and incurring multiple hospital visits for evaluation of his various complaints. M has become socially isolated and withdrawn from friends and family.

M’s developmental history is normal and his family history is negative for any psychiatric disorder. Medical history and physical examination are unremarkable. CT scan of his head is unremarkable, and all hematologic and biochemistry laboratory test values are within normal range.

[polldaddy:9971376]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Several factors may contribute to an increased chance of misdiagnosis of a psychiatric illness

On closer sequential evaluations with M and his family, we determined that the “voices” he was hearing were actually intrusive thoughts, and not hallucinations. M clarified this by saying that first he feels a “pressure”-like sensation in his head, followed by repeated intrusive thoughts of voiding his bladder that compel him to go to the restroom to try to urinate. He feels temporary relief after complying with the urge, even when he passes only a small amount of urine or just washes his hands. After a brief period of relief, this process repeats itself. Further, he was able to clarify his experience while eating food, where he first felt a “pressure”-like sensation in his head, followed by intrusive thoughts of choking that result in him not eating.

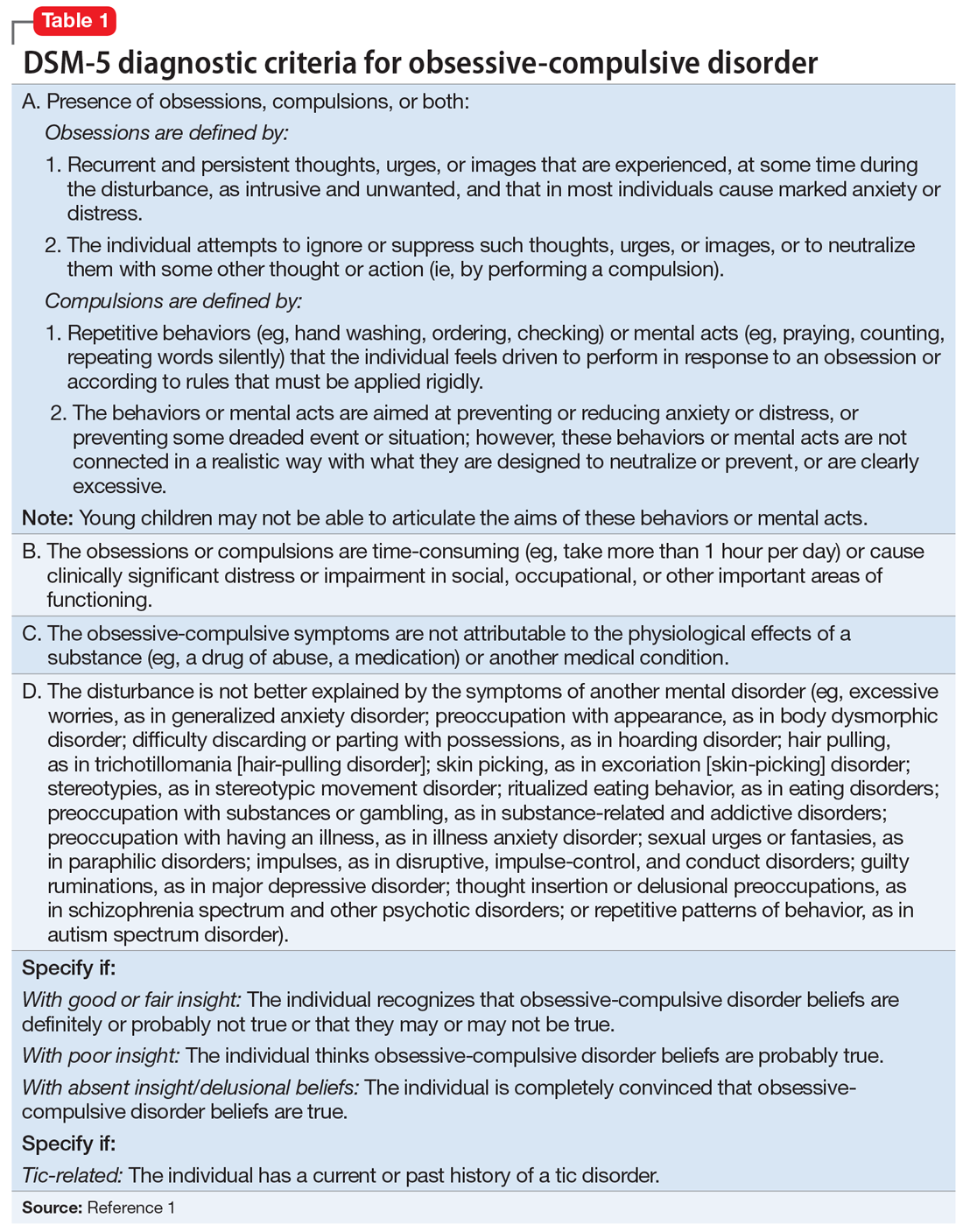

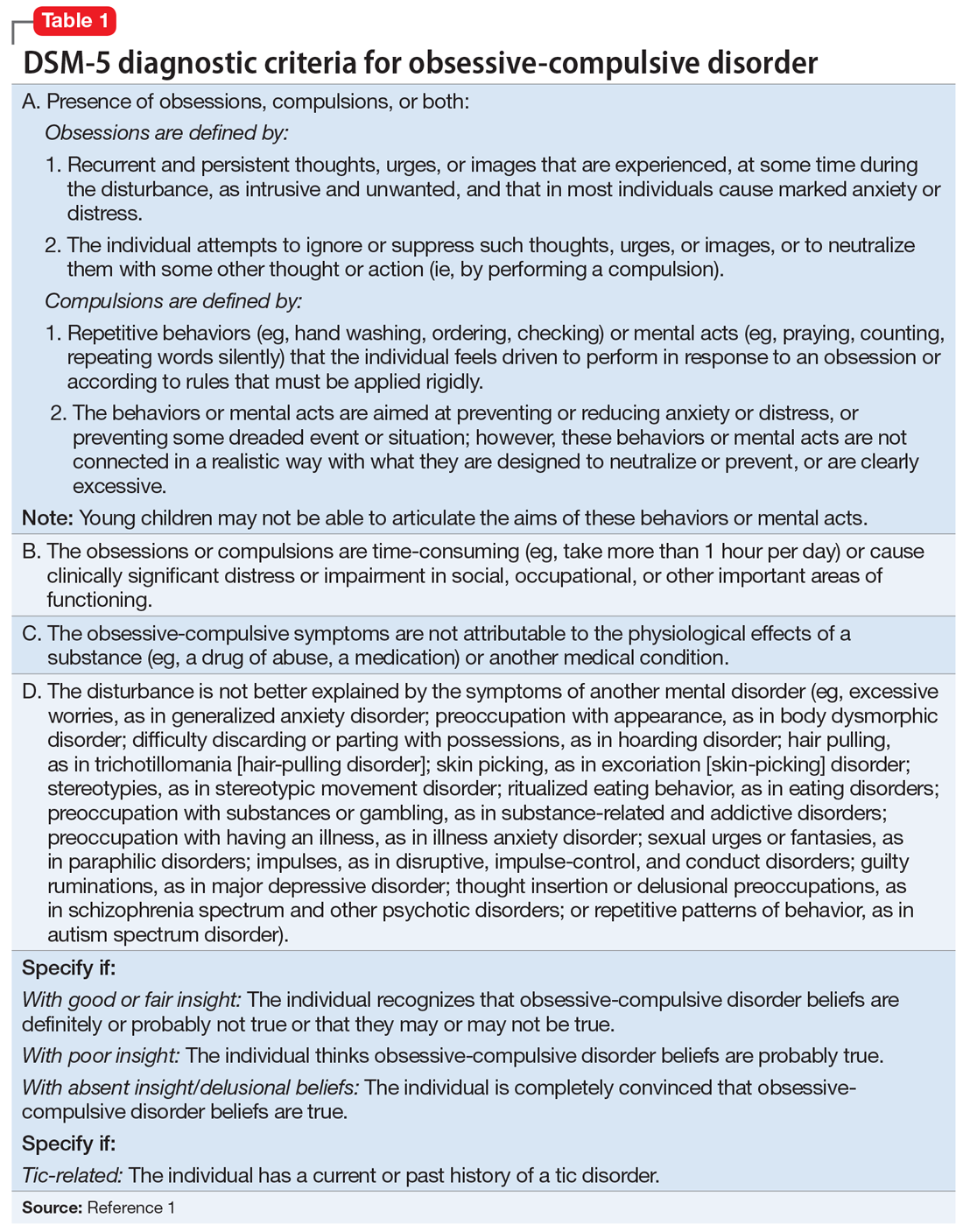

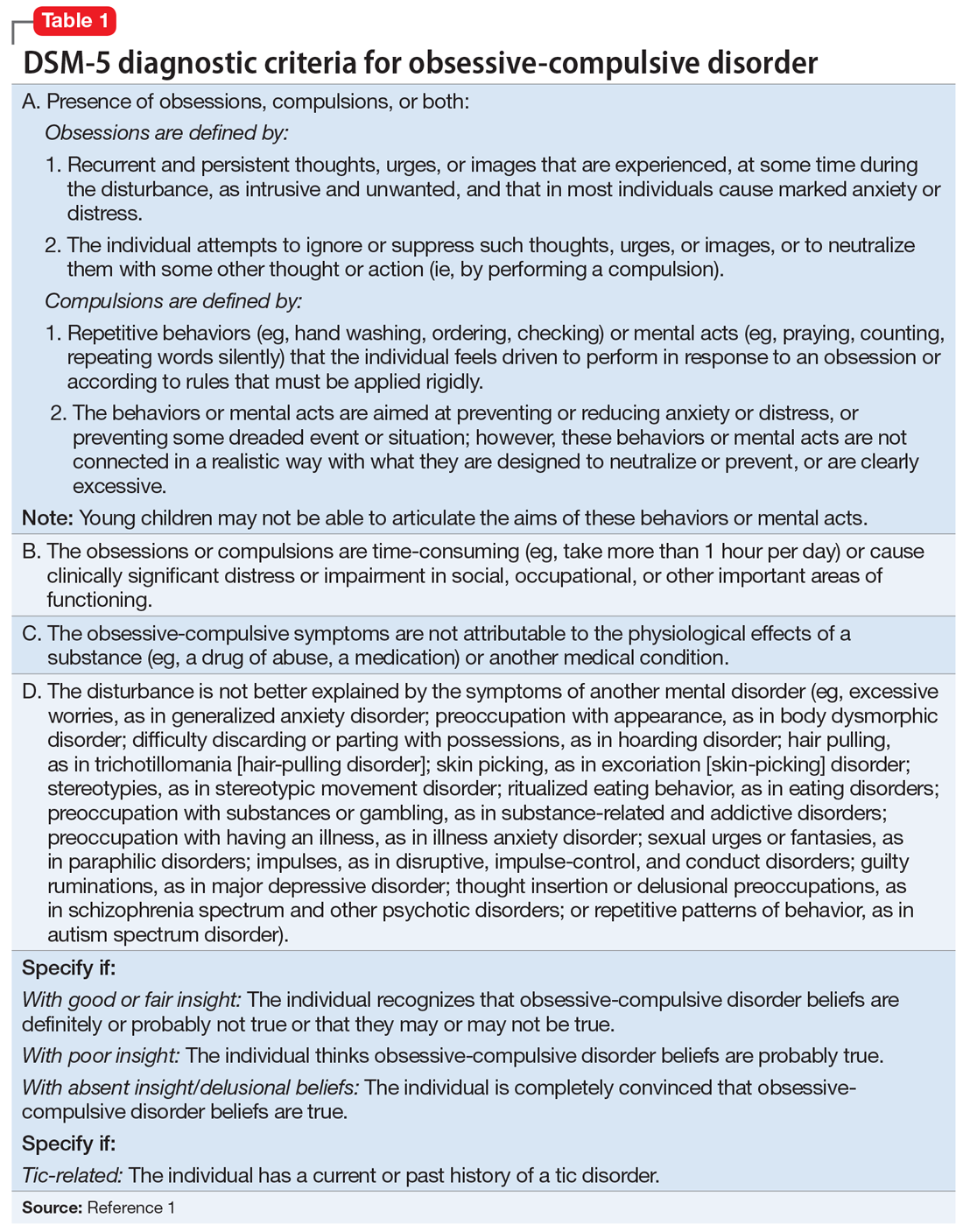

This led us to a more appropriate diagnosis of OCD (Table 11). The incidence of OCD has 2 peaks, with different gender distributions. The first peak occurs in childhood, with symptoms mostly arising between 7 and 12 years of age and affecting boys more often than girls. The second peak occurs in early adulthood, at a mean age of 21 years, with a slight female majority.2 However, OCD is often under recognized and undertreated, perhaps due to its extensive heterogeneity; symptom presentations and comorbidity patterns can vary noticeably between individual patients as well as age groups.

OCD is characterized by the presence of obsessions or compulsions that wax and wane in severity, are time-consuming (at least 1 hour per day), and cause subjective distress or interfere with life of the patient or the family. Adults with OCD recognize at some level that the obsessions and/or compulsions are excessive and unreasonable, although children are not required to have this insight to meet criteria for the diagnosis.1 Rating scales, such as the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale, Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale, and Family Accommodation Scale, are useful to obtain detailed information regarding OCD symptoms, tics, and other factors relevant to the diagnosis.

Continue to: M's symptomatology...

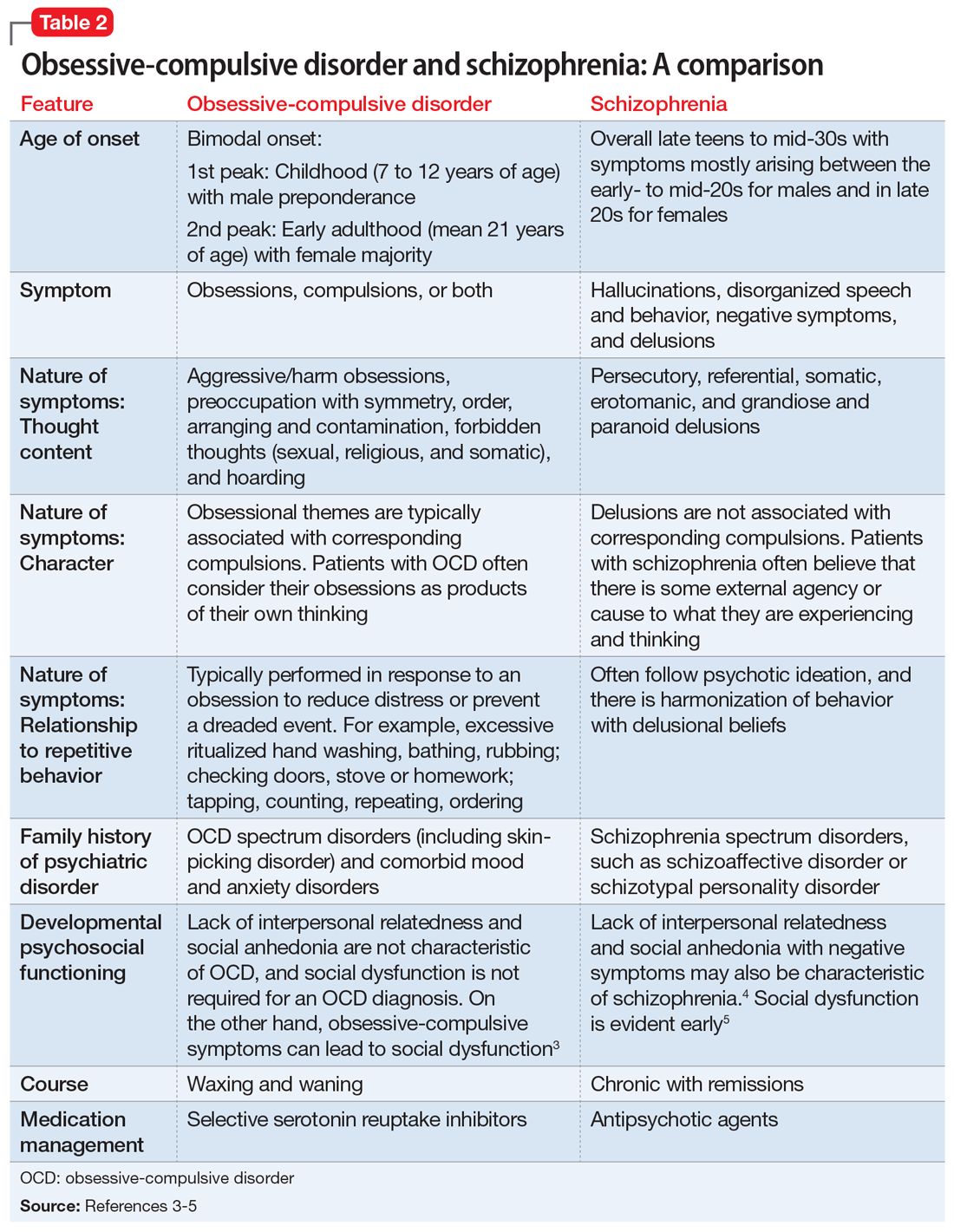

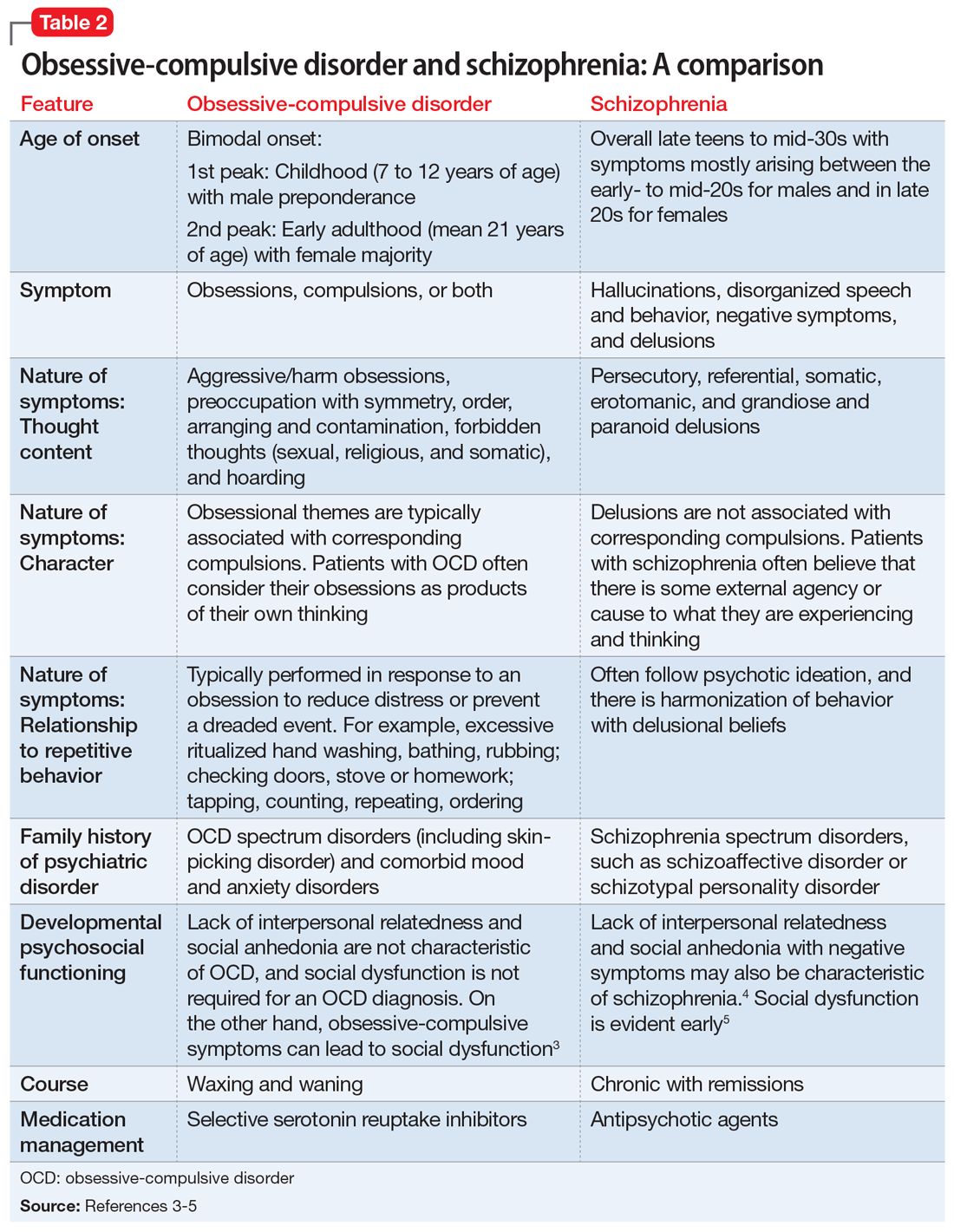

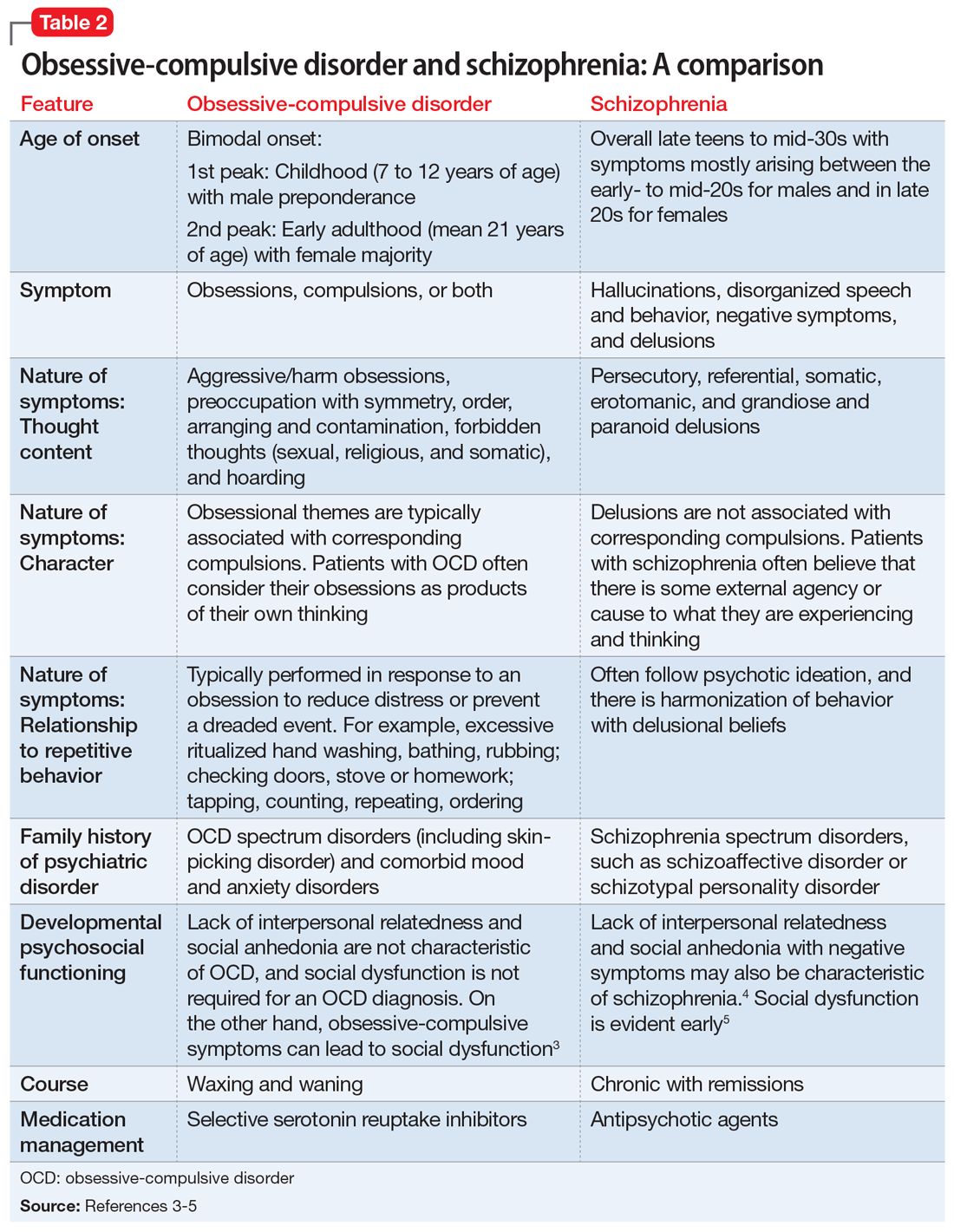

M’s symptomatology did not appear to be psychotic. He was screened for positive or negative symptoms of psychosis, which he and his family clearly denied. Moreover, M’s compulsions (going to the restroom) were typically performed in response to his obsessions (urge to void his bladder) to reduce his distress, which is different from schizophrenia, in which repetitive behaviors are performed in response to psychotic ideation, and not obsessions (Table 23-5).

M’s inattentiveness in the classroom was found to be related to his obsessions and compulsions, and not part of a symptom cluster characterizing ADHD. Teachers often interpret inattention and poor classroom performance as ADHD, but having detailed conversations with teachers often is helpful in understanding the nature of a child’s symptomology and making the appropriate diagnosis.

Establishing the correct clinical diagnosis is critical because it is the starting point in treatment. First-line medication for one condition may exacerbate the symptoms of others. For example, in addition to having a large adverse-effect burden, antipsychotics can induce de novo obsessive–compulsive symptoms (OCS) or exacerbate preexisting OCS, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may exacerbate psychosis in schizo-obsessive patients with a history of impulsivity and aggressiveness.6 Similarly, stimulant medications for ADHD may exacerbate OCS and may even induce them on their own.7,8

[polldaddy:9971377]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Studies have reported an average of 2.5 years from the onset of OCD symptoms to diagnosis in the United States.9 A key reason for this delay, which is more frequently encountered in pediatric patients, is secrecy. Children often feel embarrassed about their symptoms and conceal them until the interference with their functioning becomes extremely disabling. In some cases, symptoms may closely resemble normal childhood routines. In fact, some repetitive behaviors may be normal in some developmental stages, and OCD could be conceptualized as a pathological condition with continuity of normal behaviors during different developmental periods.10

Also, symptoms may go unnoticed for quite some time as unsuspecting and well-intentioned parents and family members become overly involved in the child’s rituals (eg, allowing for increasing frequent prolonged bathroom breaks or frequent change of clothing, etc.). This well-established phenomenon, termed accommodation, is defined as participation of family members in a child’s OCD–related rituals.11 Especially when symptoms are mild or the child is functioning well, accommodation can make it difficult for parents to realize the presence or nature of a problem, as they might tend to minimize their child’s symptoms as representing a unique personality trait or a special “quirk.” Parents generally will seek treatment when their child’s symptoms become more impairing and begin to interfere with social functioning, school performance, or family functioning.

The clinical picture is further complicated by comorbidity. Approximately 60% to 80% of children and adolescents with OCD have ≥1 comorbid psychiatric disorders. Some of the most common include tic disorders, ADHD, anxiety disorders, and mood or eating disorders.9

[polldaddy:9971379]

Continue to: TREATMENT Combination therapy

TREATMENT Combination therapy

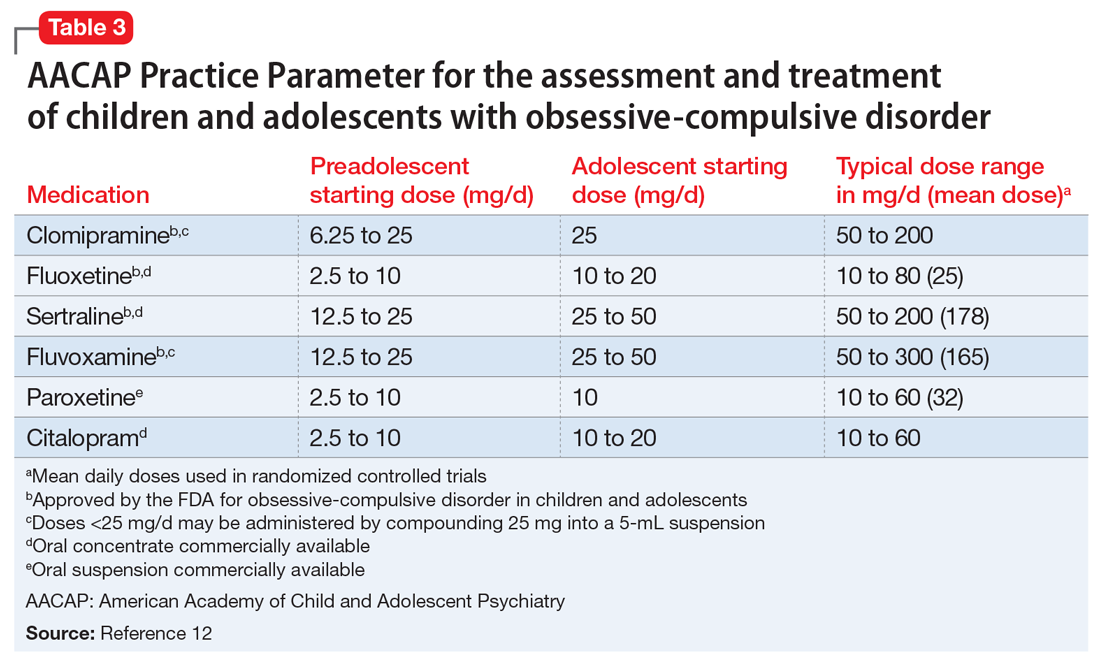

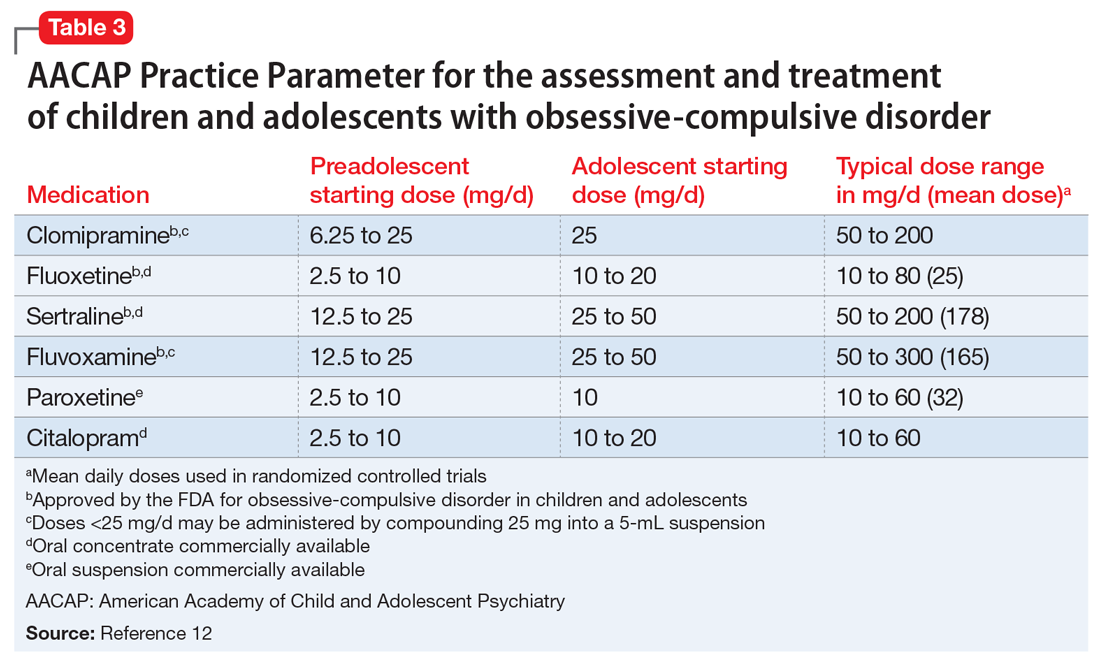

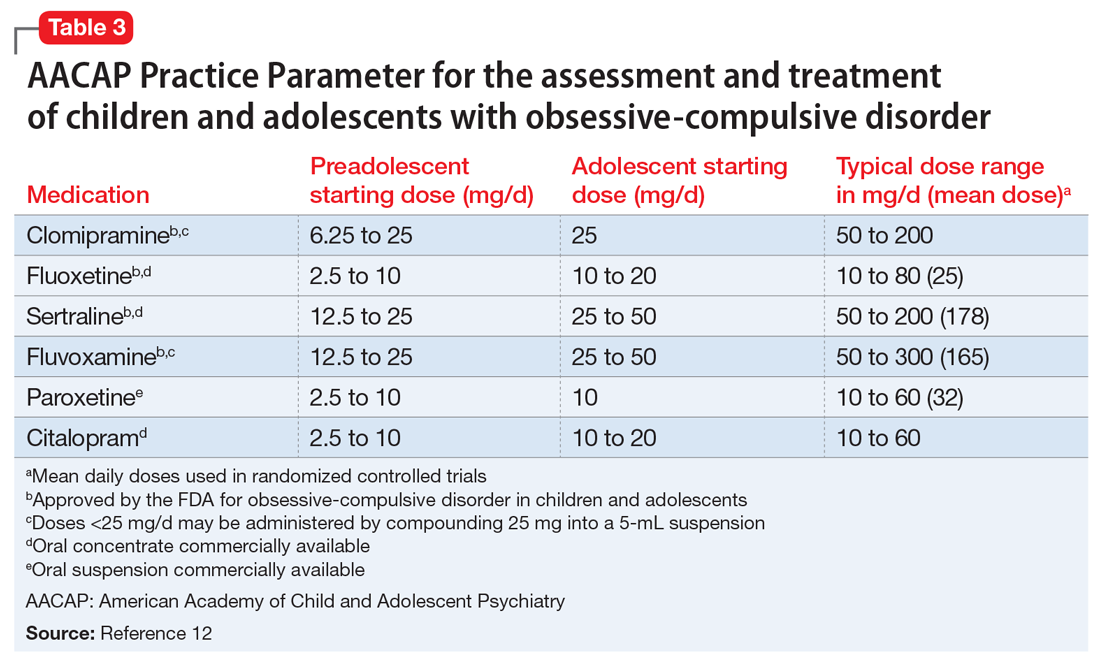

In keeping with American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry guidelines on treating OCD (Table 312), we start M on fluoxetine 10 mg/d. He also begins CBT. Fluoxetine is slowly titrated to 40 mg/d while M engages in learning and utilizing CBT techniques to manage his OCD.

The authors’ observations

The combination of CBT and medication has been suggested as the treatment of choice for moderate and severe OCD.12 The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study, a 5-year, 3-site outcome study designed to compare placebo, sertraline, CBT, and combined CBT and sertraline, concluded that the combined treatment (CBT plus sertraline) was more effective than CBT alone or sertraline alone.13 The effect sizes for the combined treatment, CBT alone, and sertraline alone were 1.4, 0.97, and 0.67, respectively. Remission rates for SSRIs alone are <33%.13,14

SSRIs are the first-line medication for OCD in children, adolescents, and adults (Table 312). Well-designed clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of the SSRIs fluoxetine, sertraline, and fluvoxamine (alone or combined with CBT) in children and adolescents with OCD.13 Other SSRIs, such as citalopram, paroxetine, and escitalopram, also have demonstrated efficacy in children and adolescents with OCD, even though the FDA has not yet approved their use in pediatric patients.12 Despite a positive trial of paroxetine in pediatric OCD,12 there have been concerns related to its higher rates of treatment-emergent suicidality,15 lower likelihood of treatment response,16 and its particularly short half-life in pediatric patients.17

Clomipramine is a tricyclic antidepressant with serotonergic properties that is used alone or to boost the effect of an SSRI when there is a partial response. It should be introduced at a low dose in pediatric patients (before age 12) and closely monitored for anticholinergic and cardiac adverse effects. A systemic review and meta-analysis of early treatment responses of SSRIs and clomipramine in pediatric OCD indicated that the greatest benefits occurred early in treatment.18 Clomipramine was associated with a greater measured benefit compared with placebo than SSRIs; there was no evidence of a relationship between SSRI dosing and treatment effect, although data were limited. Adults and children with OCD demonstrated a similar degree and time course of response to SSRIs in OCD.18

Treatment should start with a low dose to reduce the risk of adverse effects with an adequate trial for 10 to 16 weeks at adequate doses. Most experts suggest that treatment should continue for at least 12 months after symptom resolution or stabilization, followed by a very gradual cessation.19

Continue to: OUTCOME Improvement in functioning

OUTCOME Improvement in functioning

After 12 months of combined CBT and fluoxetine, M’s global assessment of functioning (GAF) scale score improves from 35 to 80, indicating major improvement in overall functional level.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Uzoma Osuchukwu, MD, ex-fellow, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, Harlem Hospital Center, New York, New York, for his assistance with this article.

Bottom Line

Obsessive-compulsive disorder may masquerade as a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, particularly in younger patients. Accurate differentiation is crucial because antipsychotics can induce de novo obsessive-compulsive symptoms (OCS) or exacerbate preexisting OCS, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may exacerbate psychosis in schizo-obsessive patients with a history of impulsivity and aggressiveness.

Related Resource

- Raveendranathan D, Shiva L, Sharma E, et al. Obsessive compulsive disorder masquerading as psychosis. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34(2):179-180.

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Paroxetine • Paxil

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Geller D, Biederman J, Jones J, et al. Is juvenile obsessive-compulsive disorder a developmental subtype of the disorder? A review of the pediatric literature. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.1998;37(4):420-427.

3. Huppert JD, Simpson HB, Nissenson KJ, et al. Quality of life and functional impairment in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A comparison of patients with and without comorbidity, patients in remission, and healthy controls. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(1):39-45.

4. Sobel W, Wolski R, Cancro R, et al. Interpersonal relatedness and paranoid schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry.1996;153(8):1084-1087.

5. Meares A. The diagnosis of prepsychotic schizophrenia. Lancet. 1959;1(7063):55-58.

6. Poyurovsky M, Weizman A, Weizman R. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in schizophrenia: Clinical characteristics and treatment. CNS Drugs. 2004;18(14):989-1010.

7. Kouris S. Methylphenidate-induced obsessive-compulsiveness. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(2):135.

8. Woolley JB, Heyman I. Dexamphetamine for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):183.

9. Geller DA. Obsessive-compulsive and spectrum disorders in children and adolescents. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;29(2):352-370.

10. Evans DW, Milanak ME, Medeiros B, et al. Magical beliefs and rituals in young children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2002;33(1):43-58.

11. Amir N, Freshman M, Foa E. Family distress and involvement in relatives of obsessive-compulsive disorder patients. J Anxiety Disord. 2000;14(3):209-217.

12. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(1):98-113.

13. Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) Team. Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(16):1969-1976.

14. Franklin ME, Sapyta J, Freeman JB, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy augmentation of pharmacotherapy in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study II (POTS II) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;306(11):1224-1232.

15. Wagner KD, Asarnow JR, Vitiello B, et al. Out of the black box: treatment of resistant depression in adolescents and the antidepressant controversy. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012;22(1):5-10.

16. Sakolsky DJ, Perel JM, Emslie GJ, et al. Antidepressant exposure as a predictor of clinical outcomes in the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents (TORDIA) study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(1):92-97.

17. Findling RL. How (not) to dose antidepressants and antipsychotics for children. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(6):79-83.

18. Varigonda AL, Jakubovski E, Bloch MH. Systematic review and meta-analysis: early treatment responses of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and clomipramine in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016 Oct;55(10):851-859.e2.

19. Mancuso E, Faro A, Joshi G, et al. Treatment of pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: a review. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(4):299-308.

CASE Auditory hallucinations?

M, age 10, has had multiple visits to the pediatric emergency department (PED) with the chief concern of excessive urinary frequency. At each visit, the medical workup has been negative and he was discharged home. After a few months, M’s parents bring their son back to the PED because he reports hearing “voices in my head” and “feeling tense and scared.” When these feelings become too overwhelming, M stops eating and experiences substantial fear and anxiety that require his mother’s repeated reassurances. M’s mother reports that 2 weeks before his most recent PED visit, he became increasingly anxious and disturbed, and said he was afraid most of the time, and worried about the safety of his family for no apparent reason.

The psychiatrist evaluates M in the PED and diagnoses him with unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder based on his persistent report of auditory and tactile hallucinations, including hearing a voice of a man telling him he was going to choke on his food and feeling someone touch his arm to soothe him during his anxious moments. M does not meet criteria for acute inpatient hospitalization, and is discharged home with referral to follow-up at our child and adolescent psychiatry outpatient clinic.

On subsequent evaluation in our clinic, M reports most of the same about his experience hearing “voices in my head” that repeatedly suggest “I might choke on my food and end up seriously ill in the hospital.” He started to hear the “voices” after he witnessed his sister choke while eating a few days earlier. He also mentions that the “voices” tell him “you have to use the restroom.” As a result, he uses the restroom several times before leaving for home and is frequently late for school. His parents accommodate his behavior—his mother allows him to use the bathroom multiple times, and his father overlooks the behavior as part of school anxiety.

At school, his teacher reports a concern for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) based on M’s continuous inattentiveness in class and dropping grades. He asks for bathroom breaks up to 15 times a day, which disrupts his class work.

These behaviors have led to a gradual 1-year decline in his overall functioning, including difficulty at school for requesting too many bathroom breaks; having to repeat the 3rd grade; and incurring multiple hospital visits for evaluation of his various complaints. M has become socially isolated and withdrawn from friends and family.

M’s developmental history is normal and his family history is negative for any psychiatric disorder. Medical history and physical examination are unremarkable. CT scan of his head is unremarkable, and all hematologic and biochemistry laboratory test values are within normal range.

[polldaddy:9971376]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Several factors may contribute to an increased chance of misdiagnosis of a psychiatric illness

On closer sequential evaluations with M and his family, we determined that the “voices” he was hearing were actually intrusive thoughts, and not hallucinations. M clarified this by saying that first he feels a “pressure”-like sensation in his head, followed by repeated intrusive thoughts of voiding his bladder that compel him to go to the restroom to try to urinate. He feels temporary relief after complying with the urge, even when he passes only a small amount of urine or just washes his hands. After a brief period of relief, this process repeats itself. Further, he was able to clarify his experience while eating food, where he first felt a “pressure”-like sensation in his head, followed by intrusive thoughts of choking that result in him not eating.

This led us to a more appropriate diagnosis of OCD (Table 11). The incidence of OCD has 2 peaks, with different gender distributions. The first peak occurs in childhood, with symptoms mostly arising between 7 and 12 years of age and affecting boys more often than girls. The second peak occurs in early adulthood, at a mean age of 21 years, with a slight female majority.2 However, OCD is often under recognized and undertreated, perhaps due to its extensive heterogeneity; symptom presentations and comorbidity patterns can vary noticeably between individual patients as well as age groups.

OCD is characterized by the presence of obsessions or compulsions that wax and wane in severity, are time-consuming (at least 1 hour per day), and cause subjective distress or interfere with life of the patient or the family. Adults with OCD recognize at some level that the obsessions and/or compulsions are excessive and unreasonable, although children are not required to have this insight to meet criteria for the diagnosis.1 Rating scales, such as the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale, Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale, and Family Accommodation Scale, are useful to obtain detailed information regarding OCD symptoms, tics, and other factors relevant to the diagnosis.

Continue to: M's symptomatology...

M’s symptomatology did not appear to be psychotic. He was screened for positive or negative symptoms of psychosis, which he and his family clearly denied. Moreover, M’s compulsions (going to the restroom) were typically performed in response to his obsessions (urge to void his bladder) to reduce his distress, which is different from schizophrenia, in which repetitive behaviors are performed in response to psychotic ideation, and not obsessions (Table 23-5).

M’s inattentiveness in the classroom was found to be related to his obsessions and compulsions, and not part of a symptom cluster characterizing ADHD. Teachers often interpret inattention and poor classroom performance as ADHD, but having detailed conversations with teachers often is helpful in understanding the nature of a child’s symptomology and making the appropriate diagnosis.

Establishing the correct clinical diagnosis is critical because it is the starting point in treatment. First-line medication for one condition may exacerbate the symptoms of others. For example, in addition to having a large adverse-effect burden, antipsychotics can induce de novo obsessive–compulsive symptoms (OCS) or exacerbate preexisting OCS, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may exacerbate psychosis in schizo-obsessive patients with a history of impulsivity and aggressiveness.6 Similarly, stimulant medications for ADHD may exacerbate OCS and may even induce them on their own.7,8

[polldaddy:9971377]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Studies have reported an average of 2.5 years from the onset of OCD symptoms to diagnosis in the United States.9 A key reason for this delay, which is more frequently encountered in pediatric patients, is secrecy. Children often feel embarrassed about their symptoms and conceal them until the interference with their functioning becomes extremely disabling. In some cases, symptoms may closely resemble normal childhood routines. In fact, some repetitive behaviors may be normal in some developmental stages, and OCD could be conceptualized as a pathological condition with continuity of normal behaviors during different developmental periods.10

Also, symptoms may go unnoticed for quite some time as unsuspecting and well-intentioned parents and family members become overly involved in the child’s rituals (eg, allowing for increasing frequent prolonged bathroom breaks or frequent change of clothing, etc.). This well-established phenomenon, termed accommodation, is defined as participation of family members in a child’s OCD–related rituals.11 Especially when symptoms are mild or the child is functioning well, accommodation can make it difficult for parents to realize the presence or nature of a problem, as they might tend to minimize their child’s symptoms as representing a unique personality trait or a special “quirk.” Parents generally will seek treatment when their child’s symptoms become more impairing and begin to interfere with social functioning, school performance, or family functioning.

The clinical picture is further complicated by comorbidity. Approximately 60% to 80% of children and adolescents with OCD have ≥1 comorbid psychiatric disorders. Some of the most common include tic disorders, ADHD, anxiety disorders, and mood or eating disorders.9

[polldaddy:9971379]

Continue to: TREATMENT Combination therapy

TREATMENT Combination therapy

In keeping with American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry guidelines on treating OCD (Table 312), we start M on fluoxetine 10 mg/d. He also begins CBT. Fluoxetine is slowly titrated to 40 mg/d while M engages in learning and utilizing CBT techniques to manage his OCD.

The authors’ observations

The combination of CBT and medication has been suggested as the treatment of choice for moderate and severe OCD.12 The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study, a 5-year, 3-site outcome study designed to compare placebo, sertraline, CBT, and combined CBT and sertraline, concluded that the combined treatment (CBT plus sertraline) was more effective than CBT alone or sertraline alone.13 The effect sizes for the combined treatment, CBT alone, and sertraline alone were 1.4, 0.97, and 0.67, respectively. Remission rates for SSRIs alone are <33%.13,14

SSRIs are the first-line medication for OCD in children, adolescents, and adults (Table 312). Well-designed clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of the SSRIs fluoxetine, sertraline, and fluvoxamine (alone or combined with CBT) in children and adolescents with OCD.13 Other SSRIs, such as citalopram, paroxetine, and escitalopram, also have demonstrated efficacy in children and adolescents with OCD, even though the FDA has not yet approved their use in pediatric patients.12 Despite a positive trial of paroxetine in pediatric OCD,12 there have been concerns related to its higher rates of treatment-emergent suicidality,15 lower likelihood of treatment response,16 and its particularly short half-life in pediatric patients.17

Clomipramine is a tricyclic antidepressant with serotonergic properties that is used alone or to boost the effect of an SSRI when there is a partial response. It should be introduced at a low dose in pediatric patients (before age 12) and closely monitored for anticholinergic and cardiac adverse effects. A systemic review and meta-analysis of early treatment responses of SSRIs and clomipramine in pediatric OCD indicated that the greatest benefits occurred early in treatment.18 Clomipramine was associated with a greater measured benefit compared with placebo than SSRIs; there was no evidence of a relationship between SSRI dosing and treatment effect, although data were limited. Adults and children with OCD demonstrated a similar degree and time course of response to SSRIs in OCD.18

Treatment should start with a low dose to reduce the risk of adverse effects with an adequate trial for 10 to 16 weeks at adequate doses. Most experts suggest that treatment should continue for at least 12 months after symptom resolution or stabilization, followed by a very gradual cessation.19

Continue to: OUTCOME Improvement in functioning

OUTCOME Improvement in functioning

After 12 months of combined CBT and fluoxetine, M’s global assessment of functioning (GAF) scale score improves from 35 to 80, indicating major improvement in overall functional level.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Uzoma Osuchukwu, MD, ex-fellow, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, Harlem Hospital Center, New York, New York, for his assistance with this article.

Bottom Line

Obsessive-compulsive disorder may masquerade as a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, particularly in younger patients. Accurate differentiation is crucial because antipsychotics can induce de novo obsessive-compulsive symptoms (OCS) or exacerbate preexisting OCS, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may exacerbate psychosis in schizo-obsessive patients with a history of impulsivity and aggressiveness.

Related Resource

- Raveendranathan D, Shiva L, Sharma E, et al. Obsessive compulsive disorder masquerading as psychosis. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34(2):179-180.

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Paroxetine • Paxil

Sertraline • Zoloft

CASE Auditory hallucinations?

M, age 10, has had multiple visits to the pediatric emergency department (PED) with the chief concern of excessive urinary frequency. At each visit, the medical workup has been negative and he was discharged home. After a few months, M’s parents bring their son back to the PED because he reports hearing “voices in my head” and “feeling tense and scared.” When these feelings become too overwhelming, M stops eating and experiences substantial fear and anxiety that require his mother’s repeated reassurances. M’s mother reports that 2 weeks before his most recent PED visit, he became increasingly anxious and disturbed, and said he was afraid most of the time, and worried about the safety of his family for no apparent reason.

The psychiatrist evaluates M in the PED and diagnoses him with unspecified schizophrenia spectrum and other psychotic disorder based on his persistent report of auditory and tactile hallucinations, including hearing a voice of a man telling him he was going to choke on his food and feeling someone touch his arm to soothe him during his anxious moments. M does not meet criteria for acute inpatient hospitalization, and is discharged home with referral to follow-up at our child and adolescent psychiatry outpatient clinic.

On subsequent evaluation in our clinic, M reports most of the same about his experience hearing “voices in my head” that repeatedly suggest “I might choke on my food and end up seriously ill in the hospital.” He started to hear the “voices” after he witnessed his sister choke while eating a few days earlier. He also mentions that the “voices” tell him “you have to use the restroom.” As a result, he uses the restroom several times before leaving for home and is frequently late for school. His parents accommodate his behavior—his mother allows him to use the bathroom multiple times, and his father overlooks the behavior as part of school anxiety.

At school, his teacher reports a concern for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) based on M’s continuous inattentiveness in class and dropping grades. He asks for bathroom breaks up to 15 times a day, which disrupts his class work.

These behaviors have led to a gradual 1-year decline in his overall functioning, including difficulty at school for requesting too many bathroom breaks; having to repeat the 3rd grade; and incurring multiple hospital visits for evaluation of his various complaints. M has become socially isolated and withdrawn from friends and family.

M’s developmental history is normal and his family history is negative for any psychiatric disorder. Medical history and physical examination are unremarkable. CT scan of his head is unremarkable, and all hematologic and biochemistry laboratory test values are within normal range.

[polldaddy:9971376]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Several factors may contribute to an increased chance of misdiagnosis of a psychiatric illness

On closer sequential evaluations with M and his family, we determined that the “voices” he was hearing were actually intrusive thoughts, and not hallucinations. M clarified this by saying that first he feels a “pressure”-like sensation in his head, followed by repeated intrusive thoughts of voiding his bladder that compel him to go to the restroom to try to urinate. He feels temporary relief after complying with the urge, even when he passes only a small amount of urine or just washes his hands. After a brief period of relief, this process repeats itself. Further, he was able to clarify his experience while eating food, where he first felt a “pressure”-like sensation in his head, followed by intrusive thoughts of choking that result in him not eating.

This led us to a more appropriate diagnosis of OCD (Table 11). The incidence of OCD has 2 peaks, with different gender distributions. The first peak occurs in childhood, with symptoms mostly arising between 7 and 12 years of age and affecting boys more often than girls. The second peak occurs in early adulthood, at a mean age of 21 years, with a slight female majority.2 However, OCD is often under recognized and undertreated, perhaps due to its extensive heterogeneity; symptom presentations and comorbidity patterns can vary noticeably between individual patients as well as age groups.

OCD is characterized by the presence of obsessions or compulsions that wax and wane in severity, are time-consuming (at least 1 hour per day), and cause subjective distress or interfere with life of the patient or the family. Adults with OCD recognize at some level that the obsessions and/or compulsions are excessive and unreasonable, although children are not required to have this insight to meet criteria for the diagnosis.1 Rating scales, such as the Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale, Dimensional Yale-Brown Obsessive-Compulsive Scale, and Family Accommodation Scale, are useful to obtain detailed information regarding OCD symptoms, tics, and other factors relevant to the diagnosis.

Continue to: M's symptomatology...

M’s symptomatology did not appear to be psychotic. He was screened for positive or negative symptoms of psychosis, which he and his family clearly denied. Moreover, M’s compulsions (going to the restroom) were typically performed in response to his obsessions (urge to void his bladder) to reduce his distress, which is different from schizophrenia, in which repetitive behaviors are performed in response to psychotic ideation, and not obsessions (Table 23-5).

M’s inattentiveness in the classroom was found to be related to his obsessions and compulsions, and not part of a symptom cluster characterizing ADHD. Teachers often interpret inattention and poor classroom performance as ADHD, but having detailed conversations with teachers often is helpful in understanding the nature of a child’s symptomology and making the appropriate diagnosis.

Establishing the correct clinical diagnosis is critical because it is the starting point in treatment. First-line medication for one condition may exacerbate the symptoms of others. For example, in addition to having a large adverse-effect burden, antipsychotics can induce de novo obsessive–compulsive symptoms (OCS) or exacerbate preexisting OCS, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may exacerbate psychosis in schizo-obsessive patients with a history of impulsivity and aggressiveness.6 Similarly, stimulant medications for ADHD may exacerbate OCS and may even induce them on their own.7,8

[polldaddy:9971377]

Continue to: The authors' observations

The authors’ observations

Studies have reported an average of 2.5 years from the onset of OCD symptoms to diagnosis in the United States.9 A key reason for this delay, which is more frequently encountered in pediatric patients, is secrecy. Children often feel embarrassed about their symptoms and conceal them until the interference with their functioning becomes extremely disabling. In some cases, symptoms may closely resemble normal childhood routines. In fact, some repetitive behaviors may be normal in some developmental stages, and OCD could be conceptualized as a pathological condition with continuity of normal behaviors during different developmental periods.10

Also, symptoms may go unnoticed for quite some time as unsuspecting and well-intentioned parents and family members become overly involved in the child’s rituals (eg, allowing for increasing frequent prolonged bathroom breaks or frequent change of clothing, etc.). This well-established phenomenon, termed accommodation, is defined as participation of family members in a child’s OCD–related rituals.11 Especially when symptoms are mild or the child is functioning well, accommodation can make it difficult for parents to realize the presence or nature of a problem, as they might tend to minimize their child’s symptoms as representing a unique personality trait or a special “quirk.” Parents generally will seek treatment when their child’s symptoms become more impairing and begin to interfere with social functioning, school performance, or family functioning.

The clinical picture is further complicated by comorbidity. Approximately 60% to 80% of children and adolescents with OCD have ≥1 comorbid psychiatric disorders. Some of the most common include tic disorders, ADHD, anxiety disorders, and mood or eating disorders.9

[polldaddy:9971379]

Continue to: TREATMENT Combination therapy

TREATMENT Combination therapy

In keeping with American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry guidelines on treating OCD (Table 312), we start M on fluoxetine 10 mg/d. He also begins CBT. Fluoxetine is slowly titrated to 40 mg/d while M engages in learning and utilizing CBT techniques to manage his OCD.

The authors’ observations

The combination of CBT and medication has been suggested as the treatment of choice for moderate and severe OCD.12 The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study, a 5-year, 3-site outcome study designed to compare placebo, sertraline, CBT, and combined CBT and sertraline, concluded that the combined treatment (CBT plus sertraline) was more effective than CBT alone or sertraline alone.13 The effect sizes for the combined treatment, CBT alone, and sertraline alone were 1.4, 0.97, and 0.67, respectively. Remission rates for SSRIs alone are <33%.13,14

SSRIs are the first-line medication for OCD in children, adolescents, and adults (Table 312). Well-designed clinical trials have demonstrated the efficacy and safety of the SSRIs fluoxetine, sertraline, and fluvoxamine (alone or combined with CBT) in children and adolescents with OCD.13 Other SSRIs, such as citalopram, paroxetine, and escitalopram, also have demonstrated efficacy in children and adolescents with OCD, even though the FDA has not yet approved their use in pediatric patients.12 Despite a positive trial of paroxetine in pediatric OCD,12 there have been concerns related to its higher rates of treatment-emergent suicidality,15 lower likelihood of treatment response,16 and its particularly short half-life in pediatric patients.17

Clomipramine is a tricyclic antidepressant with serotonergic properties that is used alone or to boost the effect of an SSRI when there is a partial response. It should be introduced at a low dose in pediatric patients (before age 12) and closely monitored for anticholinergic and cardiac adverse effects. A systemic review and meta-analysis of early treatment responses of SSRIs and clomipramine in pediatric OCD indicated that the greatest benefits occurred early in treatment.18 Clomipramine was associated with a greater measured benefit compared with placebo than SSRIs; there was no evidence of a relationship between SSRI dosing and treatment effect, although data were limited. Adults and children with OCD demonstrated a similar degree and time course of response to SSRIs in OCD.18

Treatment should start with a low dose to reduce the risk of adverse effects with an adequate trial for 10 to 16 weeks at adequate doses. Most experts suggest that treatment should continue for at least 12 months after symptom resolution or stabilization, followed by a very gradual cessation.19

Continue to: OUTCOME Improvement in functioning

OUTCOME Improvement in functioning

After 12 months of combined CBT and fluoxetine, M’s global assessment of functioning (GAF) scale score improves from 35 to 80, indicating major improvement in overall functional level.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Uzoma Osuchukwu, MD, ex-fellow, Department of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons, Harlem Hospital Center, New York, New York, for his assistance with this article.

Bottom Line

Obsessive-compulsive disorder may masquerade as a schizophrenia spectrum disorder, particularly in younger patients. Accurate differentiation is crucial because antipsychotics can induce de novo obsessive-compulsive symptoms (OCS) or exacerbate preexisting OCS, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may exacerbate psychosis in schizo-obsessive patients with a history of impulsivity and aggressiveness.

Related Resource

- Raveendranathan D, Shiva L, Sharma E, et al. Obsessive compulsive disorder masquerading as psychosis. Indian J Psychol Med. 2012;34(2):179-180.

Drug Brand Names

Citalopram • Celexa

Clomipramine • Anafranil

Escitalopram • Lexapro

Fluoxetine • Prozac

Fluvoxamine • Luvox

Paroxetine • Paxil

Sertraline • Zoloft

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Geller D, Biederman J, Jones J, et al. Is juvenile obsessive-compulsive disorder a developmental subtype of the disorder? A review of the pediatric literature. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.1998;37(4):420-427.

3. Huppert JD, Simpson HB, Nissenson KJ, et al. Quality of life and functional impairment in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A comparison of patients with and without comorbidity, patients in remission, and healthy controls. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(1):39-45.

4. Sobel W, Wolski R, Cancro R, et al. Interpersonal relatedness and paranoid schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry.1996;153(8):1084-1087.

5. Meares A. The diagnosis of prepsychotic schizophrenia. Lancet. 1959;1(7063):55-58.

6. Poyurovsky M, Weizman A, Weizman R. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in schizophrenia: Clinical characteristics and treatment. CNS Drugs. 2004;18(14):989-1010.

7. Kouris S. Methylphenidate-induced obsessive-compulsiveness. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(2):135.

8. Woolley JB, Heyman I. Dexamphetamine for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):183.

9. Geller DA. Obsessive-compulsive and spectrum disorders in children and adolescents. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;29(2):352-370.

10. Evans DW, Milanak ME, Medeiros B, et al. Magical beliefs and rituals in young children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2002;33(1):43-58.

11. Amir N, Freshman M, Foa E. Family distress and involvement in relatives of obsessive-compulsive disorder patients. J Anxiety Disord. 2000;14(3):209-217.

12. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(1):98-113.

13. Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) Team. Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(16):1969-1976.

14. Franklin ME, Sapyta J, Freeman JB, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy augmentation of pharmacotherapy in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study II (POTS II) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;306(11):1224-1232.

15. Wagner KD, Asarnow JR, Vitiello B, et al. Out of the black box: treatment of resistant depression in adolescents and the antidepressant controversy. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012;22(1):5-10.

16. Sakolsky DJ, Perel JM, Emslie GJ, et al. Antidepressant exposure as a predictor of clinical outcomes in the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents (TORDIA) study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(1):92-97.

17. Findling RL. How (not) to dose antidepressants and antipsychotics for children. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(6):79-83.

18. Varigonda AL, Jakubovski E, Bloch MH. Systematic review and meta-analysis: early treatment responses of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and clomipramine in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016 Oct;55(10):851-859.e2.

19. Mancuso E, Faro A, Joshi G, et al. Treatment of pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: a review. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(4):299-308.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Geller D, Biederman J, Jones J, et al. Is juvenile obsessive-compulsive disorder a developmental subtype of the disorder? A review of the pediatric literature. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.1998;37(4):420-427.

3. Huppert JD, Simpson HB, Nissenson KJ, et al. Quality of life and functional impairment in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A comparison of patients with and without comorbidity, patients in remission, and healthy controls. Depress Anxiety. 2009;26(1):39-45.

4. Sobel W, Wolski R, Cancro R, et al. Interpersonal relatedness and paranoid schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry.1996;153(8):1084-1087.

5. Meares A. The diagnosis of prepsychotic schizophrenia. Lancet. 1959;1(7063):55-58.

6. Poyurovsky M, Weizman A, Weizman R. Obsessive-compulsive disorder in schizophrenia: Clinical characteristics and treatment. CNS Drugs. 2004;18(14):989-1010.

7. Kouris S. Methylphenidate-induced obsessive-compulsiveness. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1998;37(2):135.

8. Woolley JB, Heyman I. Dexamphetamine for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160(1):183.

9. Geller DA. Obsessive-compulsive and spectrum disorders in children and adolescents. Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2006;29(2):352-370.

10. Evans DW, Milanak ME, Medeiros B, et al. Magical beliefs and rituals in young children. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev. 2002;33(1):43-58.

11. Amir N, Freshman M, Foa E. Family distress and involvement in relatives of obsessive-compulsive disorder patients. J Anxiety Disord. 2000;14(3):209-217.

12. Practice parameter for the assessment and treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(1):98-113.

13. Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) Team. Cognitive-behavior therapy, sertraline, and their combination for children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder: The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study (POTS) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292(16):1969-1976.

14. Franklin ME, Sapyta J, Freeman JB, et al. Cognitive behavior therapy augmentation of pharmacotherapy in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: The Pediatric OCD Treatment Study II (POTS II) randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2011;306(11):1224-1232.

15. Wagner KD, Asarnow JR, Vitiello B, et al. Out of the black box: treatment of resistant depression in adolescents and the antidepressant controversy. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2012;22(1):5-10.

16. Sakolsky DJ, Perel JM, Emslie GJ, et al. Antidepressant exposure as a predictor of clinical outcomes in the treatment of resistant depression in adolescents (TORDIA) study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(1):92-97.

17. Findling RL. How (not) to dose antidepressants and antipsychotics for children. Current Psychiatry. 2007;6(6):79-83.

18. Varigonda AL, Jakubovski E, Bloch MH. Systematic review and meta-analysis: early treatment responses of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and clomipramine in pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2016 Oct;55(10):851-859.e2.

19. Mancuso E, Faro A, Joshi G, et al. Treatment of pediatric obsessive-compulsive disorder: a review. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2010;20(4):299-308.