User login

Weight gain and antidepressants

How to control weight gain when prescribing antidepressants

The prevalence of undesired weight gain in the United States has reached an all-time high, with 68.5% of adults identified as overweight (body mass index [BMI] ≥25) or obese (BMI ≥30), 34.5% considered obese, and 6.4% considered extremely obese (BMI ≥40).1 Reasons for weight gain include various physical and nutritional factors in a patient’s life, but sometimes weight gain is iatrogenic. Many medications we prescribe are associated with weight gain, including most antidepressants and atypical antipsychotics. Clinicians might minimize or overlook the risk of weight gain when prescribing antidepressants.

Patients with major depression often have associated weight loss. Regaining weight can be seen as sign of successful treatment of depressive symptoms. If weight gain after treatment exceeds the amount of weight loss attributed to depression, however, medication could have caused the excessive gain. This is considered a side effect, or iatrogenic weight gain, and should not be considered normal or clinically acceptable.

Patients who are overweight or obese when beginning antidepressant treatment might be at greater medical risk when placed on a medication that can cause additional weight gain. The time to onset of weight gain during treatment can predict weight gain patterns; those affected in the first month are most at risk of future excessive weight gain.2

In this article, we discuss:

- considerations when prescribing antidepressants

- ways to approach weight gain

- medications available to assist in weight loss.

Our general recommendations

Screen. The United States Preventive Services Task Force maintains a Class-B recommendation for screening all patients for obesity. This means that the Task Force’s review panel determined that such screening is at least moderately or substantially beneficial.3 Screening is important in a setting of potential weight gain in patients taking an antidepressant.

Educate and treat. Provide at least some education and encouragement about eating a healthy diet and exercising, or refer the patient to a nutritionist or dietician. Next, initiate psychotherapy (motivational interviewing, cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]) as needed. Reserve anti-obesity medications for those who do not respond to weight loss efforts or who might be taking an antidepressant for the long term.

The need for medical management of weight gain has given rise to specialists who treat this complicated, multifactorial condition. Whether psychiatrists should be seen as a substitution for their specialty is not the purpose of this review; rather, how we might more effectively (1) work on our patients’ behalf to mitigate potential weight gain from the treatments that we prescribe and (2) participate in consultations that we’ve provided on their behalf.

BMI is not an absolute marker of healthBMI likely should not be viewed as a marker with absolute prognostic certainty of overall health of an overweight or obese person: An overweight person considered healthy from a cardiovascular and metabolic perspective could still benefit from preventing further weight gain.

Tomiyama et al4 concluded that BMI itself was insufficient to stratify health in a meaningful way—and that such a focus would lead to overweight and obese people in otherwise good health being penalized unfairly through higher health insurance premiums, and would divert focus on those with less optimal health but a normal BMI. The researchers’ goal was to use blood pressure, lipid levels, and glycemic markers as surrogate markers of health, and then statistically compare results with patients’ corresponding BMI. Their findings showed that approximately one-half of people who are overweight and 29% of obese people can be considered healthy.4

Potential causes of weight gainThere may be more than one reason for weight gain during depression treatment, so a multifactorial management approach might be necessary, depending on the patient’s medication regimen. Appetite might be influenced by physical (chemical, metabolic) and psychological (cultural, familial) factors. The following sections focus on specific antidepressant classes and their proclivity for weight gain.

Serotonergic antidepressantsMany patients with depression are treated with medications that alter serotonin levels in the body, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). This neurotransmitter often is affected through depression treatment, and therefore might be a factor contributing to unintended weight gain. In mice bred to lack serotonin 5-HT2c receptors in proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons, the expected anorectic reaction to serotonergic agents often is reversed, causing a robust increase in hyperphagia and obesity.5 This effect indicates that 5-HT2c receptor stimulation might control appetite and feeding.

After SSRI or SNRI treatment, accumulation of serotonin over time in the synaptic cleft is thought to result in down-regulation of 5-HT2c receptors. This may cause a relative absence of 5-HT2c receptors, similar to what is seen in mice who lack them biologically. The loss of these receptors or their activity often will result in excessive weight gain. Some sedating antidepressants (mirtazapine) and some second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) (olanzapine, quetiapine) directly block 5-HT2c receptors and might cause more rapid weight gain. Lorcaserin, a selective 5-HT2c receptor agonist, theoretically could reverse this proposed weight gain mechanism and suppress appetite by activating the POMC pathway in the hypothalamus.

Continue to: Among SSRIs and SNRIs

Among SSRIs and SNRIs, paroxetine might be one of the worst for provoking long-term weight gain; a study showed an average increase of 2.73 kg over a 4-month period.6

Theoretically, SNRIs have the ability to increase noradrenergic tone. This might be associated with nausea and a decline in appetite or it might generally curb appetite. These agents likely will cause less future weight gain. SNRIs typically induce more noradrenergic tone at increasingly higher dosages. There may be a dose-response curve in this manner. Levomilnacipran likely is the most noradrenergic of the SNRIs; recent regulatory studies suggest no statistically significant weight gain over the long term.7

Sedating antidepressants

Mirtazapine has receptor-blocking effects on noradrenergic α-2 and serotonergic 5-HT2a and 5-HT2c receptors. Additionally, histamine blocking of H1 receptors can contribute to additional weight gain, similar to what is seen with some SGAs. H1 antagonism dampens satiety response, resulting in increased caloric intake. In that case, or when specific SGAs are used for managing depression, appetite increases (H1 antagonism) and metabolism slows (possibly 5-HT2c antagonism, muscarinic receptor antagonism, etc.), thus allowing for greater adipose tissue growth and leptin insensitivity.

In a meta-analysis, mean weight increased by 1.74 kg (P < .0001) in the first 4 to 12 weeks of mirtazapine treatment, with greater variability in periods >4 months.6 Among the more novel antidepressants released since the era of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) or monoamine oxidase inhibitor, mirtazapine might have the greatest weight gain potential.

Trazodone and nefazodone block 5-HT2a and 5-HT2c receptors, as well as serotonin reuptake transporters. Compared with trazodone, nefazodone has a more potent effect on 5-HT2a receptor antagonism and a less potent effect on 5-HT2c receptors, and also mildly inhibits uptake of norepinephrine—meaning that this drug might have less weight gain potential. These medications are not used frequently for treating depression, but trazodone is used as an adjunctive agent for insomnia. Used even at off-label low dosages, trazodone exerts H1-histaminic and α-1 adrenergic antagonistic properties, decreasing the level of consciousness and allowing sedation and somnolence. Because of its fast onset and relatively short duration of action, it can improve depression symptoms by promoting restful sleep as well as by facilitating monoamine neurotransmission. It also might add to weight gain because of its pharmacodynamic receptor profile.

Tricyclic antidepressants

Amitriptyline can be associated with release of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, which is implicated in causing weight gain. Many TCAs block H1 (amitriptyline, imipramine, clomipramine), likely causing weight gain. Most TCAs antagonize muscarinic receptors as well. The more noradrenergic TCAs could curb appetite (nortriptyline, desipramine, protriptyline) similar to SNRIs, therefore countering some of the weight gain drive.

As an example, in a meta-analysis examining weight gain with antidepressants, amitriptyline was associated with weight gain of 1.52 kg above baseline in the acute period (4 to 12 weeks) and 2.24 kg above baseline at 4 to 7 months.6 These results of the acute phase should be viewed cautiously because the authors reported high heterogeneity among these studies, and the possibility of publication bias (Egger test, P < .0001). In the same meta-analysis, the even the more noradrenergic nortriptyline was associated with an increase of 2.0 kg on average over baseline during acute treatment, with that number dropping to 1.24 kg over baseline at ≥4 months.6

Newer antidepressants

Vilazodone is a weak SSRI that aggressively partially agonizes pre-synaptic and post-synaptic 5-HT1a receptors in the CNS. This dual site 5-HT1a action is somewhat unique among antidepressants. This type of agent sometimes is called multimodal,8 or could be considered an “SSRI +” antidepressant. These drugs are SSRIs at the core but have additional 5-HT receptor modulating capabilities. Vilazodone has a favorable weight gain profile, as suggested in a 52-week trial reporting 1.7 kg gain over 52 weeks, compared with an average of 6.8 to 10 kg for long-term SSRI therapy.9

Vortioxetine is a stronger SSRI that also partially agonizes presynaptic 5-HT1a receptors. In addition, it antagonizes 5-HT1d, 5-HT3, and 5-HT7 receptors, giving it a unique pharmacodynamic profile.10 Vortioxetine also had minimal impact on drug-induced weight gain in 52-week studies, with data from 2 trials indicating either minimal weight gain in 6.1% of patients (mean increase of 0.41 kg over 52 weeks)11 or gain that was not statistically significant.12

Levomilnacipran is unique in that it has the most aggressive norepinephrine reuptake inhibition of all SNRIs.13 Again, increased noradrenergic tone might curb appetite and caloric intake. Many SNRIs cause low-grade nausea, which could account for decreased appetite. Long-term, 52-week data for this drug also shows minimal proclivity for weight gain, with the trial participants reporting a slight decrease of 4.34 kg on average from baseline.14

Continue to: Addressing weight gain

Addressing weight gain

Lifestyle modification. Eating smaller portions, combined with restricting foods high in calories and fat, should be the first step. A simple suggestion to a patient to eat the same foods, but remove 20% of the portion, is a simple intervention akin to that of suggesting sleep hygiene practices for insomnia management. Under medical supervision or with referral to a dietician or nutritionist, more rigid caloric restrictions could be employed.

Commercial weight-loss programs, such as Weight Watchers or Curves, can be helpful; some insurers will only cover medications for weight loss if one of these programs have been tried or is used in combination with medication. Some patients might ask about extreme weight-loss measures, such as low-calorie diets combined with intense exercise programs that have been popularized in the media. Although the motivation to initiate and maintain meaningful weight loss should be encouraged, doing so in a more gradual manner should be the goal.

Addressing portion size is a good approach in the early stages of managing obesity. Restaurants often serve portions that have more calories than should be consumed in one meal. Visual cues can influence this trend; using smaller plates can help reduce caloric intake.15

Exercise, sustained for at least 45 minutes, can have long-lasting effects, with a small study showing an increase in metabolic rate of 190 ± 71.4 kcal (P < .001) above baseline for 14 hours after exercise.16 Endurance exercise training is associated with a significant decrease in total cholesterol, triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, as well as an increase in the high-density lipoprotein level over a 24-week period.17

Encouraging an exercise regimen that is appropriate for your patient can help maintain weight loss. In small trials,18,19 high-intensity exercise was shown to help suppress appetite and decrease 24-hour caloric consumption by 6% to 11%.18

Psychotherapy can become an important intervention for initiating and maintaining weight loss. CBT can help patients recognize and modify lifestyle components, and reinforce behaviors that promote weight loss. This can come from setting realistic weight loss goals; preventing triggering factors that lead to overeating; encouraging portion control during meals; and promoting exercise habits.

In a small, randomized controlled trial (RCT) examining weight loss in obese women, those who underwent CBT and psychoeducation for 2 hours a week for 10 weeks in addition to dietary changes and exercise showed an average weight loss of 10.4 kg at 18-month follow-up, compared with weight gain of 2.3 kg in the control group.20 The short duration of treatment in this study might be desirable to reduce cost and utilization of services. Group formats also could be employed.

Motivational interviewing is a useful tool in addiction psychiatry and shows promise for treating obesity and overeating as well. The approach may differ slightly because weight-loss therapy involves behavior modification rather than behavior cessation. In a meta-analysis of data from RCTs exploring motivational interviewing and its use as an intervention for weight loss, those in the intervention groups experienced significant weight loss as indicated by BMI decreasing a standardized mean difference of −0.51, compared with control groups.21

Medical management considerations

Diagnostics. Recognition and early intervention are instrumental in successfully treating medication-associated weight gain. It is important to obtain any family history of obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. This will likely indicate a patient’s risk for weight gain before initiating medication.

Obtain vital signs at every visit, including blood pressure. Monitoring weight at every clinical visit can be used to calculate and monitor BMI, while also asking the patient to maintain a log of weight measurements obtained at home. Measuring abdominal girth is important to watch for metabolic syndrome, although often this is the least measured variable.

Laboratory testing is helpful. Obtaining a baseline lipid panel and a fasting glucose level (consider measuring hemoglobin A1c in patients with diabetes) is warranted. Including thyroid markers, such as thyroid-stimulating hormone and thyroxine (free T4), might be important considerations, because inadequate management of hypothyroidism can complicate the clinical picture.

Follow-up testing should be ordered every 3 to 12 months to monitor progress if your patient is showing signs of rapid weight gain, or if BMI nears ≥30 kg/m². These guidelines generally are assigned for prescribing of SGAs, but can be applied when using any psychotropic with weight gain potential.

Medications to considerWhen considering the medication regimen as an intervention point, consider changing the antidepressant to one that is not associated with significant weight gain. Although not specifically indicated as a monotherapy for weight loss, switching to or augmenting therapy with bupropion could aid weight loss through appetite suppression.20 Some newer antidepressants, such as vilazodone, vortioxetine, and levomilnacipran, might have less propensity to cause weight gain. In patients with severe depression, augmenting with medications containing amphetamine or methylphenidate could cause some weight loss, but greater care should be taken because of cardiovascular effects and dependency issues.

Continue to: Discussing with your patient...

Discussing with your patient the possibility of changing or worsening depressive symptoms when adding or switching medications allows them to be aware and engaged in the process and can encourage them to notice and report changes. Developing a sensible schedule to taper an existing medication slowly over several weeks and allowing a new one to build up gradually to a therapeutic level can help minimize adverse effects or a discontinuation syndrome.

If switching antidepressants is not possible, or is ineffective, an anti-obesity medication (Table 122-29) can be considered. These medications should not be considered first-line in weight loss management, but reserved for more difficult or refractory weight loss challenges and in patients who are not able to participate in weight loss or dieting programs because of cognitive disorders, a history of nonadherance, financial or travel limitations, or in those with poor social support systems such as homelessness.

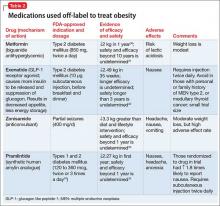

Some of these medications are not reimbursed by insurance companies; therefore, consider the financial burden to the patient and their capacity for adherence to therapy, and discuss this challenge before initiating treatment. There is some evidence for using medications off-label to treat obesity (Table 2,30-34).

Anti-obesity medications typically are considered for patients with a BMI >30 or in any overweight patient with diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or cardiovascular disease. As always, discuss with patients and their primary care provider the potential benefits and risks of adding any of these or other medications to an existing treatment regimen.

If weight loss goals are not met, consider discontinuing anti-obesity therapy. Patients and physicians should be cognizant of the need to continue long-term maintenance on these medications after successful treatment—perhaps indefinitely, because patients frequently regain weight after medication is discontinued.

Bottom Line

Many antidepressants are known to increase the risk of excessive weight gain, although risk of weigh gain varies among antidepressant classes. First, advise changes in diet and exercise; next, initiate psychotherapy as indicated, and then consider referral to a nutritionist. Consider switching to an antidepressant with less potential for causing weight gain or adding bupropion, which could lead to weight loss, if your patient can tolerate it. If these strategies are unsuccessful, consider an anti-obesity medication.

Related Resource

1. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, et al. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806-814.

2. Vandenberghe F, Gholam-Rezaee M, Saigí-Morgui N, et al. Importance of early weight changes to predict long-term weight gain during psychotropic drug treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(11):e1417-e1423.

3. Grade Definitions. Electronic Preventive Services Selector (ePSS). http://epss.ahrq.gov/ePSS/gradedef.jsp. Accessed May 2, 2016.

4. Tomiyama AJ, Hunger JM, Nguyen-Cuu J, et al. Misclassification of cardiometabolic health when using body mass index categories in NHANES 2005-2012 [published online February 4, 2016]. Int J Obes (Lond). doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.17.

5. Berglund ED, Liu C, Sohn J, et al. Serotonin 2C receptors in pro-opiomelanocortin neurons regulate energy and glucose homeostasis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(12):5061-5070.

6. Serretti A, Mandelli L. Antidepressants and body weight: a comprehensive review and meta-anaylsis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(10):1259-1272.

7. Mago R, Forero G, Greenberg WM, et al. Safety and tolerability of levomilnacipran ER in major depressive disorder: results from an open-label, 48-week extension study. Clin Drug Investig. 2013;33(10):761-771.

8. Schwartz TL, Siddiqui UA, Stahl SM. Vilazodone: a brief pharmacological and clinical review of the novel serotonin partial agonist and reuptake inhibitor. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2011;1(3):81-87.

9. Robinson DS, Kajdasz DK, Gallipoli S, et al. A 1-year, open-label study assessing the safety and tolerability of vilazodone in patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(5):643-646.

10. Stahl SM. Modes and nodes explain the mechanism of action of vortioxetine, a multimodal agent (MMA): actions at serotonin receptors may enhance downstream release of four pro-cognitive neurotransmitters. CNS Spectr. 2015;20(6):515-519.

11. Jacobsen PL, Harper L, Chrones L, et al. Safety and tolerability of vortioxetine (15 and 20 mg) in patients with major depressive disorder: results of an open-label, flexible-dose, 52-week extension study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;30(5):255-264.

12. Boulenger JP, Loft H, Olsen CK. Efficacy and safety of vortioxetine (Lu AA21004), 15 and 20 mg/day: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, duloxetine-referenced study in the acute treatment of adult patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(3):138-149.

13. Grady MM, Stahl SM. Novel agents in development for the treatment of depression. CNS Spectr. 2013;18(suppl 1):37-40; quiz 41.

14. Mago R, Forero G, Greenberg WM, et al. Safety and tolerability of levomilnacipran ER in major depressive disorder: results from an open-label, 48-week extension study. Clin Drug Investig. 2013;33(10):761-771.

15. Hollands GJ, Shemilt I, Marteau TM, et al. Portion, package or tableware size for changing selection and consumption of food, alcohol and tobacco. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9:CD011045.

16. Knab AM, Shanely RA, Corbin KD, et al. A 45-minute vigorous exercise bout increases metabolic rate for 14 hours. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(9):1643-1648.

17. Halverstadt A, Phares DA, Wilund KR, et al. Endurance exercise training raises high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and lowers small low-density lipoprotein and very low-density lipoprotein independent of body fat phenotypes in older men and women. Metabolism. 2007;56(4):444-450.

18. Thivel D, Isacco L, Montaurier C, et al. The 24-h energy intake of obese adolescents is spontaneously reduced after intensive exercise: a randomized controlled trial in calorimetric chambers [published online January 17, 2012]. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29840. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029840.

19. Sim AY, Wallman KE, Fairchild TJ, et al. High-intensity intermittent exercise attenuates ad-libitum energy intake. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014;38(3):417-422.

20. Stahre L, Tärnell B, Håkanson CE, et al. A randomized controlled trial of two weight-reducing short-term group treatment programs for obesity with an 18-month follow-up. Int J Behav Med. 2007;14(1):48-55.

21. Armstrong MJ, Mottershead TA, Ronksley PE, et al. Motivational interviewing to improve weight loss in overweight and/or obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2011;12(9):709-723.

22. Apovian CM, Aronne L, Rubino D, et al. A randomized, phase 3 trial of naltrexone SR/bupropion SR on weight and obesity-related risk factors (COR-II). Obesity (Silver Springs). 2013;21(5):935-943.

23. Greenway FL, Fujioka K, Plodkowski RA, et al. Effect of naltrexone plus bupropion on weight loss in overweight and obese adults (COR-I): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9741):595-605.

24. Fidler MC, Sanchez M, Raether B, et al; BLOSSOM Clinical Trial Group. A one-year randomized trial of lorcaserin for weight loss in obese and overweight adults: the BLOSSOM trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(10):3067-3077.

25. Gadde KM, Allison DB, Ryan DH, et al. Effects of low-dose, controlled-release, phentermine plus topiramate combination on weight and associated comorbidities in overweight and obese adults (CONQUER): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial [Erratum in Lancet. 2011;377(9776):1494]. Lancet. 2011;377(9774):1341-1352.

26. Garvey WT, Ryan DH, Look M, et al. Two-year sustained weight loss and metabolic benefits with controlled-release phentermine/topiramate in obese and overweight adults (SEQUEL): a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 extension study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(2):297-308.

27. Pi-Sunyer X, Astrup A, Fujioka K, et al; SCALE Obesity and Prediabetes NN8022-1839 Study Group. A randomized, controlled trial of 3.0 mg of liraglutide in weight management. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(1):11-22.

28. Leblanc ES, O’Connor E, Whitlock EP, et al. Effectiveness of primary care-relevant treatments for obesity in adults: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(7):434-447.

29. Torgerson JS, Hauptman J, Boldrin MN, et al. XENical in the prevention of diabetes in obese subjects (XENDOS) study: a randomized study of orlistat as an adjunct to lifestyle changes for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in obese patients. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(1):155-161.

30. Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393-403.

31. McDonagh MS, Selph S, Ozpinar A, et al. Systematic review of the benefits and risks of metformin in treating obesity in children aged 18 years and younger. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(2):178-184.

32. Dushay J, Gao C, Gopalakrishnan GS, et al. Short-term exenatide treatment leads to significant weight loss in a subset of obese women without diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(1):4-11.

33. Gadde KM, Kopping MF, Wagner HR 2nd, et al. Zonisamide for weight reduction in obese adults: a 1-year randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(20):1557-1564.

34. Singh-Franco D, Perez A, Harrington C. The effect of pramlintide acetate on glycemic control and weight in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and in obese patients without diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(2):169-180.

The prevalence of undesired weight gain in the United States has reached an all-time high, with 68.5% of adults identified as overweight (body mass index [BMI] ≥25) or obese (BMI ≥30), 34.5% considered obese, and 6.4% considered extremely obese (BMI ≥40).1 Reasons for weight gain include various physical and nutritional factors in a patient’s life, but sometimes weight gain is iatrogenic. Many medications we prescribe are associated with weight gain, including most antidepressants and atypical antipsychotics. Clinicians might minimize or overlook the risk of weight gain when prescribing antidepressants.

Patients with major depression often have associated weight loss. Regaining weight can be seen as sign of successful treatment of depressive symptoms. If weight gain after treatment exceeds the amount of weight loss attributed to depression, however, medication could have caused the excessive gain. This is considered a side effect, or iatrogenic weight gain, and should not be considered normal or clinically acceptable.

Patients who are overweight or obese when beginning antidepressant treatment might be at greater medical risk when placed on a medication that can cause additional weight gain. The time to onset of weight gain during treatment can predict weight gain patterns; those affected in the first month are most at risk of future excessive weight gain.2

In this article, we discuss:

- considerations when prescribing antidepressants

- ways to approach weight gain

- medications available to assist in weight loss.

Our general recommendations

Screen. The United States Preventive Services Task Force maintains a Class-B recommendation for screening all patients for obesity. This means that the Task Force’s review panel determined that such screening is at least moderately or substantially beneficial.3 Screening is important in a setting of potential weight gain in patients taking an antidepressant.

Educate and treat. Provide at least some education and encouragement about eating a healthy diet and exercising, or refer the patient to a nutritionist or dietician. Next, initiate psychotherapy (motivational interviewing, cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]) as needed. Reserve anti-obesity medications for those who do not respond to weight loss efforts or who might be taking an antidepressant for the long term.

The need for medical management of weight gain has given rise to specialists who treat this complicated, multifactorial condition. Whether psychiatrists should be seen as a substitution for their specialty is not the purpose of this review; rather, how we might more effectively (1) work on our patients’ behalf to mitigate potential weight gain from the treatments that we prescribe and (2) participate in consultations that we’ve provided on their behalf.

BMI is not an absolute marker of healthBMI likely should not be viewed as a marker with absolute prognostic certainty of overall health of an overweight or obese person: An overweight person considered healthy from a cardiovascular and metabolic perspective could still benefit from preventing further weight gain.

Tomiyama et al4 concluded that BMI itself was insufficient to stratify health in a meaningful way—and that such a focus would lead to overweight and obese people in otherwise good health being penalized unfairly through higher health insurance premiums, and would divert focus on those with less optimal health but a normal BMI. The researchers’ goal was to use blood pressure, lipid levels, and glycemic markers as surrogate markers of health, and then statistically compare results with patients’ corresponding BMI. Their findings showed that approximately one-half of people who are overweight and 29% of obese people can be considered healthy.4

Potential causes of weight gainThere may be more than one reason for weight gain during depression treatment, so a multifactorial management approach might be necessary, depending on the patient’s medication regimen. Appetite might be influenced by physical (chemical, metabolic) and psychological (cultural, familial) factors. The following sections focus on specific antidepressant classes and their proclivity for weight gain.

Serotonergic antidepressantsMany patients with depression are treated with medications that alter serotonin levels in the body, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). This neurotransmitter often is affected through depression treatment, and therefore might be a factor contributing to unintended weight gain. In mice bred to lack serotonin 5-HT2c receptors in proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons, the expected anorectic reaction to serotonergic agents often is reversed, causing a robust increase in hyperphagia and obesity.5 This effect indicates that 5-HT2c receptor stimulation might control appetite and feeding.

After SSRI or SNRI treatment, accumulation of serotonin over time in the synaptic cleft is thought to result in down-regulation of 5-HT2c receptors. This may cause a relative absence of 5-HT2c receptors, similar to what is seen in mice who lack them biologically. The loss of these receptors or their activity often will result in excessive weight gain. Some sedating antidepressants (mirtazapine) and some second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) (olanzapine, quetiapine) directly block 5-HT2c receptors and might cause more rapid weight gain. Lorcaserin, a selective 5-HT2c receptor agonist, theoretically could reverse this proposed weight gain mechanism and suppress appetite by activating the POMC pathway in the hypothalamus.

Continue to: Among SSRIs and SNRIs

Among SSRIs and SNRIs, paroxetine might be one of the worst for provoking long-term weight gain; a study showed an average increase of 2.73 kg over a 4-month period.6

Theoretically, SNRIs have the ability to increase noradrenergic tone. This might be associated with nausea and a decline in appetite or it might generally curb appetite. These agents likely will cause less future weight gain. SNRIs typically induce more noradrenergic tone at increasingly higher dosages. There may be a dose-response curve in this manner. Levomilnacipran likely is the most noradrenergic of the SNRIs; recent regulatory studies suggest no statistically significant weight gain over the long term.7

Sedating antidepressants

Mirtazapine has receptor-blocking effects on noradrenergic α-2 and serotonergic 5-HT2a and 5-HT2c receptors. Additionally, histamine blocking of H1 receptors can contribute to additional weight gain, similar to what is seen with some SGAs. H1 antagonism dampens satiety response, resulting in increased caloric intake. In that case, or when specific SGAs are used for managing depression, appetite increases (H1 antagonism) and metabolism slows (possibly 5-HT2c antagonism, muscarinic receptor antagonism, etc.), thus allowing for greater adipose tissue growth and leptin insensitivity.

In a meta-analysis, mean weight increased by 1.74 kg (P < .0001) in the first 4 to 12 weeks of mirtazapine treatment, with greater variability in periods >4 months.6 Among the more novel antidepressants released since the era of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) or monoamine oxidase inhibitor, mirtazapine might have the greatest weight gain potential.

Trazodone and nefazodone block 5-HT2a and 5-HT2c receptors, as well as serotonin reuptake transporters. Compared with trazodone, nefazodone has a more potent effect on 5-HT2a receptor antagonism and a less potent effect on 5-HT2c receptors, and also mildly inhibits uptake of norepinephrine—meaning that this drug might have less weight gain potential. These medications are not used frequently for treating depression, but trazodone is used as an adjunctive agent for insomnia. Used even at off-label low dosages, trazodone exerts H1-histaminic and α-1 adrenergic antagonistic properties, decreasing the level of consciousness and allowing sedation and somnolence. Because of its fast onset and relatively short duration of action, it can improve depression symptoms by promoting restful sleep as well as by facilitating monoamine neurotransmission. It also might add to weight gain because of its pharmacodynamic receptor profile.

Tricyclic antidepressants

Amitriptyline can be associated with release of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, which is implicated in causing weight gain. Many TCAs block H1 (amitriptyline, imipramine, clomipramine), likely causing weight gain. Most TCAs antagonize muscarinic receptors as well. The more noradrenergic TCAs could curb appetite (nortriptyline, desipramine, protriptyline) similar to SNRIs, therefore countering some of the weight gain drive.

As an example, in a meta-analysis examining weight gain with antidepressants, amitriptyline was associated with weight gain of 1.52 kg above baseline in the acute period (4 to 12 weeks) and 2.24 kg above baseline at 4 to 7 months.6 These results of the acute phase should be viewed cautiously because the authors reported high heterogeneity among these studies, and the possibility of publication bias (Egger test, P < .0001). In the same meta-analysis, the even the more noradrenergic nortriptyline was associated with an increase of 2.0 kg on average over baseline during acute treatment, with that number dropping to 1.24 kg over baseline at ≥4 months.6

Newer antidepressants

Vilazodone is a weak SSRI that aggressively partially agonizes pre-synaptic and post-synaptic 5-HT1a receptors in the CNS. This dual site 5-HT1a action is somewhat unique among antidepressants. This type of agent sometimes is called multimodal,8 or could be considered an “SSRI +” antidepressant. These drugs are SSRIs at the core but have additional 5-HT receptor modulating capabilities. Vilazodone has a favorable weight gain profile, as suggested in a 52-week trial reporting 1.7 kg gain over 52 weeks, compared with an average of 6.8 to 10 kg for long-term SSRI therapy.9

Vortioxetine is a stronger SSRI that also partially agonizes presynaptic 5-HT1a receptors. In addition, it antagonizes 5-HT1d, 5-HT3, and 5-HT7 receptors, giving it a unique pharmacodynamic profile.10 Vortioxetine also had minimal impact on drug-induced weight gain in 52-week studies, with data from 2 trials indicating either minimal weight gain in 6.1% of patients (mean increase of 0.41 kg over 52 weeks)11 or gain that was not statistically significant.12

Levomilnacipran is unique in that it has the most aggressive norepinephrine reuptake inhibition of all SNRIs.13 Again, increased noradrenergic tone might curb appetite and caloric intake. Many SNRIs cause low-grade nausea, which could account for decreased appetite. Long-term, 52-week data for this drug also shows minimal proclivity for weight gain, with the trial participants reporting a slight decrease of 4.34 kg on average from baseline.14

Continue to: Addressing weight gain

Addressing weight gain

Lifestyle modification. Eating smaller portions, combined with restricting foods high in calories and fat, should be the first step. A simple suggestion to a patient to eat the same foods, but remove 20% of the portion, is a simple intervention akin to that of suggesting sleep hygiene practices for insomnia management. Under medical supervision or with referral to a dietician or nutritionist, more rigid caloric restrictions could be employed.

Commercial weight-loss programs, such as Weight Watchers or Curves, can be helpful; some insurers will only cover medications for weight loss if one of these programs have been tried or is used in combination with medication. Some patients might ask about extreme weight-loss measures, such as low-calorie diets combined with intense exercise programs that have been popularized in the media. Although the motivation to initiate and maintain meaningful weight loss should be encouraged, doing so in a more gradual manner should be the goal.

Addressing portion size is a good approach in the early stages of managing obesity. Restaurants often serve portions that have more calories than should be consumed in one meal. Visual cues can influence this trend; using smaller plates can help reduce caloric intake.15

Exercise, sustained for at least 45 minutes, can have long-lasting effects, with a small study showing an increase in metabolic rate of 190 ± 71.4 kcal (P < .001) above baseline for 14 hours after exercise.16 Endurance exercise training is associated with a significant decrease in total cholesterol, triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, as well as an increase in the high-density lipoprotein level over a 24-week period.17

Encouraging an exercise regimen that is appropriate for your patient can help maintain weight loss. In small trials,18,19 high-intensity exercise was shown to help suppress appetite and decrease 24-hour caloric consumption by 6% to 11%.18

Psychotherapy can become an important intervention for initiating and maintaining weight loss. CBT can help patients recognize and modify lifestyle components, and reinforce behaviors that promote weight loss. This can come from setting realistic weight loss goals; preventing triggering factors that lead to overeating; encouraging portion control during meals; and promoting exercise habits.

In a small, randomized controlled trial (RCT) examining weight loss in obese women, those who underwent CBT and psychoeducation for 2 hours a week for 10 weeks in addition to dietary changes and exercise showed an average weight loss of 10.4 kg at 18-month follow-up, compared with weight gain of 2.3 kg in the control group.20 The short duration of treatment in this study might be desirable to reduce cost and utilization of services. Group formats also could be employed.

Motivational interviewing is a useful tool in addiction psychiatry and shows promise for treating obesity and overeating as well. The approach may differ slightly because weight-loss therapy involves behavior modification rather than behavior cessation. In a meta-analysis of data from RCTs exploring motivational interviewing and its use as an intervention for weight loss, those in the intervention groups experienced significant weight loss as indicated by BMI decreasing a standardized mean difference of −0.51, compared with control groups.21

Medical management considerations

Diagnostics. Recognition and early intervention are instrumental in successfully treating medication-associated weight gain. It is important to obtain any family history of obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. This will likely indicate a patient’s risk for weight gain before initiating medication.

Obtain vital signs at every visit, including blood pressure. Monitoring weight at every clinical visit can be used to calculate and monitor BMI, while also asking the patient to maintain a log of weight measurements obtained at home. Measuring abdominal girth is important to watch for metabolic syndrome, although often this is the least measured variable.

Laboratory testing is helpful. Obtaining a baseline lipid panel and a fasting glucose level (consider measuring hemoglobin A1c in patients with diabetes) is warranted. Including thyroid markers, such as thyroid-stimulating hormone and thyroxine (free T4), might be important considerations, because inadequate management of hypothyroidism can complicate the clinical picture.

Follow-up testing should be ordered every 3 to 12 months to monitor progress if your patient is showing signs of rapid weight gain, or if BMI nears ≥30 kg/m². These guidelines generally are assigned for prescribing of SGAs, but can be applied when using any psychotropic with weight gain potential.

Medications to considerWhen considering the medication regimen as an intervention point, consider changing the antidepressant to one that is not associated with significant weight gain. Although not specifically indicated as a monotherapy for weight loss, switching to or augmenting therapy with bupropion could aid weight loss through appetite suppression.20 Some newer antidepressants, such as vilazodone, vortioxetine, and levomilnacipran, might have less propensity to cause weight gain. In patients with severe depression, augmenting with medications containing amphetamine or methylphenidate could cause some weight loss, but greater care should be taken because of cardiovascular effects and dependency issues.

Continue to: Discussing with your patient...

Discussing with your patient the possibility of changing or worsening depressive symptoms when adding or switching medications allows them to be aware and engaged in the process and can encourage them to notice and report changes. Developing a sensible schedule to taper an existing medication slowly over several weeks and allowing a new one to build up gradually to a therapeutic level can help minimize adverse effects or a discontinuation syndrome.

If switching antidepressants is not possible, or is ineffective, an anti-obesity medication (Table 122-29) can be considered. These medications should not be considered first-line in weight loss management, but reserved for more difficult or refractory weight loss challenges and in patients who are not able to participate in weight loss or dieting programs because of cognitive disorders, a history of nonadherance, financial or travel limitations, or in those with poor social support systems such as homelessness.

Some of these medications are not reimbursed by insurance companies; therefore, consider the financial burden to the patient and their capacity for adherence to therapy, and discuss this challenge before initiating treatment. There is some evidence for using medications off-label to treat obesity (Table 2,30-34).

Anti-obesity medications typically are considered for patients with a BMI >30 or in any overweight patient with diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or cardiovascular disease. As always, discuss with patients and their primary care provider the potential benefits and risks of adding any of these or other medications to an existing treatment regimen.

If weight loss goals are not met, consider discontinuing anti-obesity therapy. Patients and physicians should be cognizant of the need to continue long-term maintenance on these medications after successful treatment—perhaps indefinitely, because patients frequently regain weight after medication is discontinued.

Bottom Line

Many antidepressants are known to increase the risk of excessive weight gain, although risk of weigh gain varies among antidepressant classes. First, advise changes in diet and exercise; next, initiate psychotherapy as indicated, and then consider referral to a nutritionist. Consider switching to an antidepressant with less potential for causing weight gain or adding bupropion, which could lead to weight loss, if your patient can tolerate it. If these strategies are unsuccessful, consider an anti-obesity medication.

Related Resource

The prevalence of undesired weight gain in the United States has reached an all-time high, with 68.5% of adults identified as overweight (body mass index [BMI] ≥25) or obese (BMI ≥30), 34.5% considered obese, and 6.4% considered extremely obese (BMI ≥40).1 Reasons for weight gain include various physical and nutritional factors in a patient’s life, but sometimes weight gain is iatrogenic. Many medications we prescribe are associated with weight gain, including most antidepressants and atypical antipsychotics. Clinicians might minimize or overlook the risk of weight gain when prescribing antidepressants.

Patients with major depression often have associated weight loss. Regaining weight can be seen as sign of successful treatment of depressive symptoms. If weight gain after treatment exceeds the amount of weight loss attributed to depression, however, medication could have caused the excessive gain. This is considered a side effect, or iatrogenic weight gain, and should not be considered normal or clinically acceptable.

Patients who are overweight or obese when beginning antidepressant treatment might be at greater medical risk when placed on a medication that can cause additional weight gain. The time to onset of weight gain during treatment can predict weight gain patterns; those affected in the first month are most at risk of future excessive weight gain.2

In this article, we discuss:

- considerations when prescribing antidepressants

- ways to approach weight gain

- medications available to assist in weight loss.

Our general recommendations

Screen. The United States Preventive Services Task Force maintains a Class-B recommendation for screening all patients for obesity. This means that the Task Force’s review panel determined that such screening is at least moderately or substantially beneficial.3 Screening is important in a setting of potential weight gain in patients taking an antidepressant.

Educate and treat. Provide at least some education and encouragement about eating a healthy diet and exercising, or refer the patient to a nutritionist or dietician. Next, initiate psychotherapy (motivational interviewing, cognitive-behavioral therapy [CBT]) as needed. Reserve anti-obesity medications for those who do not respond to weight loss efforts or who might be taking an antidepressant for the long term.

The need for medical management of weight gain has given rise to specialists who treat this complicated, multifactorial condition. Whether psychiatrists should be seen as a substitution for their specialty is not the purpose of this review; rather, how we might more effectively (1) work on our patients’ behalf to mitigate potential weight gain from the treatments that we prescribe and (2) participate in consultations that we’ve provided on their behalf.

BMI is not an absolute marker of healthBMI likely should not be viewed as a marker with absolute prognostic certainty of overall health of an overweight or obese person: An overweight person considered healthy from a cardiovascular and metabolic perspective could still benefit from preventing further weight gain.

Tomiyama et al4 concluded that BMI itself was insufficient to stratify health in a meaningful way—and that such a focus would lead to overweight and obese people in otherwise good health being penalized unfairly through higher health insurance premiums, and would divert focus on those with less optimal health but a normal BMI. The researchers’ goal was to use blood pressure, lipid levels, and glycemic markers as surrogate markers of health, and then statistically compare results with patients’ corresponding BMI. Their findings showed that approximately one-half of people who are overweight and 29% of obese people can be considered healthy.4

Potential causes of weight gainThere may be more than one reason for weight gain during depression treatment, so a multifactorial management approach might be necessary, depending on the patient’s medication regimen. Appetite might be influenced by physical (chemical, metabolic) and psychological (cultural, familial) factors. The following sections focus on specific antidepressant classes and their proclivity for weight gain.

Serotonergic antidepressantsMany patients with depression are treated with medications that alter serotonin levels in the body, such as selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) or serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). This neurotransmitter often is affected through depression treatment, and therefore might be a factor contributing to unintended weight gain. In mice bred to lack serotonin 5-HT2c receptors in proopiomelanocortin (POMC) neurons, the expected anorectic reaction to serotonergic agents often is reversed, causing a robust increase in hyperphagia and obesity.5 This effect indicates that 5-HT2c receptor stimulation might control appetite and feeding.

After SSRI or SNRI treatment, accumulation of serotonin over time in the synaptic cleft is thought to result in down-regulation of 5-HT2c receptors. This may cause a relative absence of 5-HT2c receptors, similar to what is seen in mice who lack them biologically. The loss of these receptors or their activity often will result in excessive weight gain. Some sedating antidepressants (mirtazapine) and some second-generation antipsychotics (SGAs) (olanzapine, quetiapine) directly block 5-HT2c receptors and might cause more rapid weight gain. Lorcaserin, a selective 5-HT2c receptor agonist, theoretically could reverse this proposed weight gain mechanism and suppress appetite by activating the POMC pathway in the hypothalamus.

Continue to: Among SSRIs and SNRIs

Among SSRIs and SNRIs, paroxetine might be one of the worst for provoking long-term weight gain; a study showed an average increase of 2.73 kg over a 4-month period.6

Theoretically, SNRIs have the ability to increase noradrenergic tone. This might be associated with nausea and a decline in appetite or it might generally curb appetite. These agents likely will cause less future weight gain. SNRIs typically induce more noradrenergic tone at increasingly higher dosages. There may be a dose-response curve in this manner. Levomilnacipran likely is the most noradrenergic of the SNRIs; recent regulatory studies suggest no statistically significant weight gain over the long term.7

Sedating antidepressants

Mirtazapine has receptor-blocking effects on noradrenergic α-2 and serotonergic 5-HT2a and 5-HT2c receptors. Additionally, histamine blocking of H1 receptors can contribute to additional weight gain, similar to what is seen with some SGAs. H1 antagonism dampens satiety response, resulting in increased caloric intake. In that case, or when specific SGAs are used for managing depression, appetite increases (H1 antagonism) and metabolism slows (possibly 5-HT2c antagonism, muscarinic receptor antagonism, etc.), thus allowing for greater adipose tissue growth and leptin insensitivity.

In a meta-analysis, mean weight increased by 1.74 kg (P < .0001) in the first 4 to 12 weeks of mirtazapine treatment, with greater variability in periods >4 months.6 Among the more novel antidepressants released since the era of tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs) or monoamine oxidase inhibitor, mirtazapine might have the greatest weight gain potential.

Trazodone and nefazodone block 5-HT2a and 5-HT2c receptors, as well as serotonin reuptake transporters. Compared with trazodone, nefazodone has a more potent effect on 5-HT2a receptor antagonism and a less potent effect on 5-HT2c receptors, and also mildly inhibits uptake of norepinephrine—meaning that this drug might have less weight gain potential. These medications are not used frequently for treating depression, but trazodone is used as an adjunctive agent for insomnia. Used even at off-label low dosages, trazodone exerts H1-histaminic and α-1 adrenergic antagonistic properties, decreasing the level of consciousness and allowing sedation and somnolence. Because of its fast onset and relatively short duration of action, it can improve depression symptoms by promoting restful sleep as well as by facilitating monoamine neurotransmission. It also might add to weight gain because of its pharmacodynamic receptor profile.

Tricyclic antidepressants

Amitriptyline can be associated with release of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, which is implicated in causing weight gain. Many TCAs block H1 (amitriptyline, imipramine, clomipramine), likely causing weight gain. Most TCAs antagonize muscarinic receptors as well. The more noradrenergic TCAs could curb appetite (nortriptyline, desipramine, protriptyline) similar to SNRIs, therefore countering some of the weight gain drive.

As an example, in a meta-analysis examining weight gain with antidepressants, amitriptyline was associated with weight gain of 1.52 kg above baseline in the acute period (4 to 12 weeks) and 2.24 kg above baseline at 4 to 7 months.6 These results of the acute phase should be viewed cautiously because the authors reported high heterogeneity among these studies, and the possibility of publication bias (Egger test, P < .0001). In the same meta-analysis, the even the more noradrenergic nortriptyline was associated with an increase of 2.0 kg on average over baseline during acute treatment, with that number dropping to 1.24 kg over baseline at ≥4 months.6

Newer antidepressants

Vilazodone is a weak SSRI that aggressively partially agonizes pre-synaptic and post-synaptic 5-HT1a receptors in the CNS. This dual site 5-HT1a action is somewhat unique among antidepressants. This type of agent sometimes is called multimodal,8 or could be considered an “SSRI +” antidepressant. These drugs are SSRIs at the core but have additional 5-HT receptor modulating capabilities. Vilazodone has a favorable weight gain profile, as suggested in a 52-week trial reporting 1.7 kg gain over 52 weeks, compared with an average of 6.8 to 10 kg for long-term SSRI therapy.9

Vortioxetine is a stronger SSRI that also partially agonizes presynaptic 5-HT1a receptors. In addition, it antagonizes 5-HT1d, 5-HT3, and 5-HT7 receptors, giving it a unique pharmacodynamic profile.10 Vortioxetine also had minimal impact on drug-induced weight gain in 52-week studies, with data from 2 trials indicating either minimal weight gain in 6.1% of patients (mean increase of 0.41 kg over 52 weeks)11 or gain that was not statistically significant.12

Levomilnacipran is unique in that it has the most aggressive norepinephrine reuptake inhibition of all SNRIs.13 Again, increased noradrenergic tone might curb appetite and caloric intake. Many SNRIs cause low-grade nausea, which could account for decreased appetite. Long-term, 52-week data for this drug also shows minimal proclivity for weight gain, with the trial participants reporting a slight decrease of 4.34 kg on average from baseline.14

Continue to: Addressing weight gain

Addressing weight gain

Lifestyle modification. Eating smaller portions, combined with restricting foods high in calories and fat, should be the first step. A simple suggestion to a patient to eat the same foods, but remove 20% of the portion, is a simple intervention akin to that of suggesting sleep hygiene practices for insomnia management. Under medical supervision or with referral to a dietician or nutritionist, more rigid caloric restrictions could be employed.

Commercial weight-loss programs, such as Weight Watchers or Curves, can be helpful; some insurers will only cover medications for weight loss if one of these programs have been tried or is used in combination with medication. Some patients might ask about extreme weight-loss measures, such as low-calorie diets combined with intense exercise programs that have been popularized in the media. Although the motivation to initiate and maintain meaningful weight loss should be encouraged, doing so in a more gradual manner should be the goal.

Addressing portion size is a good approach in the early stages of managing obesity. Restaurants often serve portions that have more calories than should be consumed in one meal. Visual cues can influence this trend; using smaller plates can help reduce caloric intake.15

Exercise, sustained for at least 45 minutes, can have long-lasting effects, with a small study showing an increase in metabolic rate of 190 ± 71.4 kcal (P < .001) above baseline for 14 hours after exercise.16 Endurance exercise training is associated with a significant decrease in total cholesterol, triglycerides, and low-density lipoprotein cholesterol, as well as an increase in the high-density lipoprotein level over a 24-week period.17

Encouraging an exercise regimen that is appropriate for your patient can help maintain weight loss. In small trials,18,19 high-intensity exercise was shown to help suppress appetite and decrease 24-hour caloric consumption by 6% to 11%.18

Psychotherapy can become an important intervention for initiating and maintaining weight loss. CBT can help patients recognize and modify lifestyle components, and reinforce behaviors that promote weight loss. This can come from setting realistic weight loss goals; preventing triggering factors that lead to overeating; encouraging portion control during meals; and promoting exercise habits.

In a small, randomized controlled trial (RCT) examining weight loss in obese women, those who underwent CBT and psychoeducation for 2 hours a week for 10 weeks in addition to dietary changes and exercise showed an average weight loss of 10.4 kg at 18-month follow-up, compared with weight gain of 2.3 kg in the control group.20 The short duration of treatment in this study might be desirable to reduce cost and utilization of services. Group formats also could be employed.

Motivational interviewing is a useful tool in addiction psychiatry and shows promise for treating obesity and overeating as well. The approach may differ slightly because weight-loss therapy involves behavior modification rather than behavior cessation. In a meta-analysis of data from RCTs exploring motivational interviewing and its use as an intervention for weight loss, those in the intervention groups experienced significant weight loss as indicated by BMI decreasing a standardized mean difference of −0.51, compared with control groups.21

Medical management considerations

Diagnostics. Recognition and early intervention are instrumental in successfully treating medication-associated weight gain. It is important to obtain any family history of obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and hyperlipidemia. This will likely indicate a patient’s risk for weight gain before initiating medication.

Obtain vital signs at every visit, including blood pressure. Monitoring weight at every clinical visit can be used to calculate and monitor BMI, while also asking the patient to maintain a log of weight measurements obtained at home. Measuring abdominal girth is important to watch for metabolic syndrome, although often this is the least measured variable.

Laboratory testing is helpful. Obtaining a baseline lipid panel and a fasting glucose level (consider measuring hemoglobin A1c in patients with diabetes) is warranted. Including thyroid markers, such as thyroid-stimulating hormone and thyroxine (free T4), might be important considerations, because inadequate management of hypothyroidism can complicate the clinical picture.

Follow-up testing should be ordered every 3 to 12 months to monitor progress if your patient is showing signs of rapid weight gain, or if BMI nears ≥30 kg/m². These guidelines generally are assigned for prescribing of SGAs, but can be applied when using any psychotropic with weight gain potential.

Medications to considerWhen considering the medication regimen as an intervention point, consider changing the antidepressant to one that is not associated with significant weight gain. Although not specifically indicated as a monotherapy for weight loss, switching to or augmenting therapy with bupropion could aid weight loss through appetite suppression.20 Some newer antidepressants, such as vilazodone, vortioxetine, and levomilnacipran, might have less propensity to cause weight gain. In patients with severe depression, augmenting with medications containing amphetamine or methylphenidate could cause some weight loss, but greater care should be taken because of cardiovascular effects and dependency issues.

Continue to: Discussing with your patient...

Discussing with your patient the possibility of changing or worsening depressive symptoms when adding or switching medications allows them to be aware and engaged in the process and can encourage them to notice and report changes. Developing a sensible schedule to taper an existing medication slowly over several weeks and allowing a new one to build up gradually to a therapeutic level can help minimize adverse effects or a discontinuation syndrome.

If switching antidepressants is not possible, or is ineffective, an anti-obesity medication (Table 122-29) can be considered. These medications should not be considered first-line in weight loss management, but reserved for more difficult or refractory weight loss challenges and in patients who are not able to participate in weight loss or dieting programs because of cognitive disorders, a history of nonadherance, financial or travel limitations, or in those with poor social support systems such as homelessness.

Some of these medications are not reimbursed by insurance companies; therefore, consider the financial burden to the patient and their capacity for adherence to therapy, and discuss this challenge before initiating treatment. There is some evidence for using medications off-label to treat obesity (Table 2,30-34).

Anti-obesity medications typically are considered for patients with a BMI >30 or in any overweight patient with diabetes, hyperlipidemia, or cardiovascular disease. As always, discuss with patients and their primary care provider the potential benefits and risks of adding any of these or other medications to an existing treatment regimen.

If weight loss goals are not met, consider discontinuing anti-obesity therapy. Patients and physicians should be cognizant of the need to continue long-term maintenance on these medications after successful treatment—perhaps indefinitely, because patients frequently regain weight after medication is discontinued.

Bottom Line

Many antidepressants are known to increase the risk of excessive weight gain, although risk of weigh gain varies among antidepressant classes. First, advise changes in diet and exercise; next, initiate psychotherapy as indicated, and then consider referral to a nutritionist. Consider switching to an antidepressant with less potential for causing weight gain or adding bupropion, which could lead to weight loss, if your patient can tolerate it. If these strategies are unsuccessful, consider an anti-obesity medication.

Related Resource

1. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, et al. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806-814.

2. Vandenberghe F, Gholam-Rezaee M, Saigí-Morgui N, et al. Importance of early weight changes to predict long-term weight gain during psychotropic drug treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(11):e1417-e1423.

3. Grade Definitions. Electronic Preventive Services Selector (ePSS). http://epss.ahrq.gov/ePSS/gradedef.jsp. Accessed May 2, 2016.

4. Tomiyama AJ, Hunger JM, Nguyen-Cuu J, et al. Misclassification of cardiometabolic health when using body mass index categories in NHANES 2005-2012 [published online February 4, 2016]. Int J Obes (Lond). doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.17.

5. Berglund ED, Liu C, Sohn J, et al. Serotonin 2C receptors in pro-opiomelanocortin neurons regulate energy and glucose homeostasis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(12):5061-5070.

6. Serretti A, Mandelli L. Antidepressants and body weight: a comprehensive review and meta-anaylsis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(10):1259-1272.

7. Mago R, Forero G, Greenberg WM, et al. Safety and tolerability of levomilnacipran ER in major depressive disorder: results from an open-label, 48-week extension study. Clin Drug Investig. 2013;33(10):761-771.

8. Schwartz TL, Siddiqui UA, Stahl SM. Vilazodone: a brief pharmacological and clinical review of the novel serotonin partial agonist and reuptake inhibitor. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2011;1(3):81-87.

9. Robinson DS, Kajdasz DK, Gallipoli S, et al. A 1-year, open-label study assessing the safety and tolerability of vilazodone in patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(5):643-646.

10. Stahl SM. Modes and nodes explain the mechanism of action of vortioxetine, a multimodal agent (MMA): actions at serotonin receptors may enhance downstream release of four pro-cognitive neurotransmitters. CNS Spectr. 2015;20(6):515-519.

11. Jacobsen PL, Harper L, Chrones L, et al. Safety and tolerability of vortioxetine (15 and 20 mg) in patients with major depressive disorder: results of an open-label, flexible-dose, 52-week extension study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;30(5):255-264.

12. Boulenger JP, Loft H, Olsen CK. Efficacy and safety of vortioxetine (Lu AA21004), 15 and 20 mg/day: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, duloxetine-referenced study in the acute treatment of adult patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(3):138-149.

13. Grady MM, Stahl SM. Novel agents in development for the treatment of depression. CNS Spectr. 2013;18(suppl 1):37-40; quiz 41.

14. Mago R, Forero G, Greenberg WM, et al. Safety and tolerability of levomilnacipran ER in major depressive disorder: results from an open-label, 48-week extension study. Clin Drug Investig. 2013;33(10):761-771.

15. Hollands GJ, Shemilt I, Marteau TM, et al. Portion, package or tableware size for changing selection and consumption of food, alcohol and tobacco. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9:CD011045.

16. Knab AM, Shanely RA, Corbin KD, et al. A 45-minute vigorous exercise bout increases metabolic rate for 14 hours. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(9):1643-1648.

17. Halverstadt A, Phares DA, Wilund KR, et al. Endurance exercise training raises high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and lowers small low-density lipoprotein and very low-density lipoprotein independent of body fat phenotypes in older men and women. Metabolism. 2007;56(4):444-450.

18. Thivel D, Isacco L, Montaurier C, et al. The 24-h energy intake of obese adolescents is spontaneously reduced after intensive exercise: a randomized controlled trial in calorimetric chambers [published online January 17, 2012]. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29840. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029840.

19. Sim AY, Wallman KE, Fairchild TJ, et al. High-intensity intermittent exercise attenuates ad-libitum energy intake. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014;38(3):417-422.

20. Stahre L, Tärnell B, Håkanson CE, et al. A randomized controlled trial of two weight-reducing short-term group treatment programs for obesity with an 18-month follow-up. Int J Behav Med. 2007;14(1):48-55.

21. Armstrong MJ, Mottershead TA, Ronksley PE, et al. Motivational interviewing to improve weight loss in overweight and/or obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2011;12(9):709-723.

22. Apovian CM, Aronne L, Rubino D, et al. A randomized, phase 3 trial of naltrexone SR/bupropion SR on weight and obesity-related risk factors (COR-II). Obesity (Silver Springs). 2013;21(5):935-943.

23. Greenway FL, Fujioka K, Plodkowski RA, et al. Effect of naltrexone plus bupropion on weight loss in overweight and obese adults (COR-I): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9741):595-605.

24. Fidler MC, Sanchez M, Raether B, et al; BLOSSOM Clinical Trial Group. A one-year randomized trial of lorcaserin for weight loss in obese and overweight adults: the BLOSSOM trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(10):3067-3077.

25. Gadde KM, Allison DB, Ryan DH, et al. Effects of low-dose, controlled-release, phentermine plus topiramate combination on weight and associated comorbidities in overweight and obese adults (CONQUER): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial [Erratum in Lancet. 2011;377(9776):1494]. Lancet. 2011;377(9774):1341-1352.

26. Garvey WT, Ryan DH, Look M, et al. Two-year sustained weight loss and metabolic benefits with controlled-release phentermine/topiramate in obese and overweight adults (SEQUEL): a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 extension study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(2):297-308.

27. Pi-Sunyer X, Astrup A, Fujioka K, et al; SCALE Obesity and Prediabetes NN8022-1839 Study Group. A randomized, controlled trial of 3.0 mg of liraglutide in weight management. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(1):11-22.

28. Leblanc ES, O’Connor E, Whitlock EP, et al. Effectiveness of primary care-relevant treatments for obesity in adults: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(7):434-447.

29. Torgerson JS, Hauptman J, Boldrin MN, et al. XENical in the prevention of diabetes in obese subjects (XENDOS) study: a randomized study of orlistat as an adjunct to lifestyle changes for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in obese patients. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(1):155-161.

30. Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393-403.

31. McDonagh MS, Selph S, Ozpinar A, et al. Systematic review of the benefits and risks of metformin in treating obesity in children aged 18 years and younger. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(2):178-184.

32. Dushay J, Gao C, Gopalakrishnan GS, et al. Short-term exenatide treatment leads to significant weight loss in a subset of obese women without diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(1):4-11.

33. Gadde KM, Kopping MF, Wagner HR 2nd, et al. Zonisamide for weight reduction in obese adults: a 1-year randomized controlled trial. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(20):1557-1564.

34. Singh-Franco D, Perez A, Harrington C. The effect of pramlintide acetate on glycemic control and weight in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus and in obese patients without diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2011;13(2):169-180.

1. Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, et al. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;311(8):806-814.

2. Vandenberghe F, Gholam-Rezaee M, Saigí-Morgui N, et al. Importance of early weight changes to predict long-term weight gain during psychotropic drug treatment. J Clin Psychiatry. 2015;76(11):e1417-e1423.

3. Grade Definitions. Electronic Preventive Services Selector (ePSS). http://epss.ahrq.gov/ePSS/gradedef.jsp. Accessed May 2, 2016.

4. Tomiyama AJ, Hunger JM, Nguyen-Cuu J, et al. Misclassification of cardiometabolic health when using body mass index categories in NHANES 2005-2012 [published online February 4, 2016]. Int J Obes (Lond). doi: 10.1038/ijo.2016.17.

5. Berglund ED, Liu C, Sohn J, et al. Serotonin 2C receptors in pro-opiomelanocortin neurons regulate energy and glucose homeostasis. J Clin Invest. 2013;123(12):5061-5070.

6. Serretti A, Mandelli L. Antidepressants and body weight: a comprehensive review and meta-anaylsis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;71(10):1259-1272.

7. Mago R, Forero G, Greenberg WM, et al. Safety and tolerability of levomilnacipran ER in major depressive disorder: results from an open-label, 48-week extension study. Clin Drug Investig. 2013;33(10):761-771.

8. Schwartz TL, Siddiqui UA, Stahl SM. Vilazodone: a brief pharmacological and clinical review of the novel serotonin partial agonist and reuptake inhibitor. Ther Adv Psychopharmacol. 2011;1(3):81-87.

9. Robinson DS, Kajdasz DK, Gallipoli S, et al. A 1-year, open-label study assessing the safety and tolerability of vilazodone in patients with major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2011;31(5):643-646.

10. Stahl SM. Modes and nodes explain the mechanism of action of vortioxetine, a multimodal agent (MMA): actions at serotonin receptors may enhance downstream release of four pro-cognitive neurotransmitters. CNS Spectr. 2015;20(6):515-519.

11. Jacobsen PL, Harper L, Chrones L, et al. Safety and tolerability of vortioxetine (15 and 20 mg) in patients with major depressive disorder: results of an open-label, flexible-dose, 52-week extension study. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;30(5):255-264.

12. Boulenger JP, Loft H, Olsen CK. Efficacy and safety of vortioxetine (Lu AA21004), 15 and 20 mg/day: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, duloxetine-referenced study in the acute treatment of adult patients with major depressive disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2014;29(3):138-149.

13. Grady MM, Stahl SM. Novel agents in development for the treatment of depression. CNS Spectr. 2013;18(suppl 1):37-40; quiz 41.

14. Mago R, Forero G, Greenberg WM, et al. Safety and tolerability of levomilnacipran ER in major depressive disorder: results from an open-label, 48-week extension study. Clin Drug Investig. 2013;33(10):761-771.

15. Hollands GJ, Shemilt I, Marteau TM, et al. Portion, package or tableware size for changing selection and consumption of food, alcohol and tobacco. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;9:CD011045.

16. Knab AM, Shanely RA, Corbin KD, et al. A 45-minute vigorous exercise bout increases metabolic rate for 14 hours. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2011;43(9):1643-1648.

17. Halverstadt A, Phares DA, Wilund KR, et al. Endurance exercise training raises high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and lowers small low-density lipoprotein and very low-density lipoprotein independent of body fat phenotypes in older men and women. Metabolism. 2007;56(4):444-450.

18. Thivel D, Isacco L, Montaurier C, et al. The 24-h energy intake of obese adolescents is spontaneously reduced after intensive exercise: a randomized controlled trial in calorimetric chambers [published online January 17, 2012]. PLoS One. 2012;7(1):e29840. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0029840.

19. Sim AY, Wallman KE, Fairchild TJ, et al. High-intensity intermittent exercise attenuates ad-libitum energy intake. Int J Obes (Lond). 2014;38(3):417-422.

20. Stahre L, Tärnell B, Håkanson CE, et al. A randomized controlled trial of two weight-reducing short-term group treatment programs for obesity with an 18-month follow-up. Int J Behav Med. 2007;14(1):48-55.

21. Armstrong MJ, Mottershead TA, Ronksley PE, et al. Motivational interviewing to improve weight loss in overweight and/or obese patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Obes Rev. 2011;12(9):709-723.

22. Apovian CM, Aronne L, Rubino D, et al. A randomized, phase 3 trial of naltrexone SR/bupropion SR on weight and obesity-related risk factors (COR-II). Obesity (Silver Springs). 2013;21(5):935-943.

23. Greenway FL, Fujioka K, Plodkowski RA, et al. Effect of naltrexone plus bupropion on weight loss in overweight and obese adults (COR-I): a multicentre, randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2010;376(9741):595-605.

24. Fidler MC, Sanchez M, Raether B, et al; BLOSSOM Clinical Trial Group. A one-year randomized trial of lorcaserin for weight loss in obese and overweight adults: the BLOSSOM trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(10):3067-3077.

25. Gadde KM, Allison DB, Ryan DH, et al. Effects of low-dose, controlled-release, phentermine plus topiramate combination on weight and associated comorbidities in overweight and obese adults (CONQUER): a randomised, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial [Erratum in Lancet. 2011;377(9776):1494]. Lancet. 2011;377(9774):1341-1352.

26. Garvey WT, Ryan DH, Look M, et al. Two-year sustained weight loss and metabolic benefits with controlled-release phentermine/topiramate in obese and overweight adults (SEQUEL): a randomized, placebo-controlled, phase 3 extension study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(2):297-308.

27. Pi-Sunyer X, Astrup A, Fujioka K, et al; SCALE Obesity and Prediabetes NN8022-1839 Study Group. A randomized, controlled trial of 3.0 mg of liraglutide in weight management. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(1):11-22.

28. Leblanc ES, O’Connor E, Whitlock EP, et al. Effectiveness of primary care-relevant treatments for obesity in adults: a systematic evidence review for the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155(7):434-447.

29. Torgerson JS, Hauptman J, Boldrin MN, et al. XENical in the prevention of diabetes in obese subjects (XENDOS) study: a randomized study of orlistat as an adjunct to lifestyle changes for the prevention of type 2 diabetes in obese patients. Diabetes Care. 2004;27(1):155-161.

30. Knowler WC, Barrett-Connor E, Fowler SE, et al. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346(6):393-403.

31. McDonagh MS, Selph S, Ozpinar A, et al. Systematic review of the benefits and risks of metformin in treating obesity in children aged 18 years and younger. JAMA Pediatr. 2014;168(2):178-184.

32. Dushay J, Gao C, Gopalakrishnan GS, et al. Short-term exenatide treatment leads to significant weight loss in a subset of obese women without diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2012;35(1):4-11.