User login

Diagnosis and Management of Aggressive B-Cell Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma

Abstract

- Objective: To review the diagnosis and management of aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: NHL comprises a wide variety of malignant hematologic disorders with varying clinical and biological features. Aggressive NHLs are characterized by rapid clinical progression without therapy. However, a significant proportion of patients are cured with appropriate combination chemotherapy or combined modality regimens. In contrast, the indolent lymphomas have a relatively good prognosis (median survival of 10 years or longer) but usually are not curable in advanced clinical stages. Overall 5-year survival for aggressive NHLs with current treatment is approximately 50% to 60%, with relapses typically occurring within the first 5 years.

- Conclusion: Treatment strategies for relapsed patients offer some potential for cure; however, clinical trial participation should be encouraged whenever possible to investigate new approaches for improving outcomes in this patient population.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) comprises a wide variety of malignant hematologic disorders with varying clinical and biological features. The more than 60 separate NHL subtypes can be classified according to cell of origin (B cell versus T cell), anatomical location (eg, orbital, testicular, bone, central nervous system), clinical behavior (indolent versus aggressive), histological features, or cytogenetic abnormalities. Although various NHL classification schemes have been used over the years, the World Health Organization (WHO) classification is now widely accepted as the definitive pathologic classification system for lymphoproliferative disorders, incorporating morphologic, immunohistochemical, flow cytometric, cytogenetic, and molecular features [1]. While the pathologic and molecular subclassification of NHL has become increasingly refined in recent years, from a management standpoint, classification based on clinical behavior remains very useful. This approach separates NHL subtypes into indolent versus aggressive categories. Whereas indolent NHLs may remain clinically insignificant for months to years, aggressive B-cell NHLs generally become life-threatening within weeks to months without treatment.

Epidemiology

Data from cancer registries show a steady, unexplainable increase in the incidence of NHL during the second half of the 20th century; the incidence has subsequently plateaued. There was a significant increase in NHL incidence between 1970 and 1995, which has been attributed in part to the HIV epidemic. More than 72,000 new cases of NHL were diagnosed in the United States in 2017, compared to just over 8000 cases of Hodgkin lymphoma, making NHL the sixth most common cancer in adult men and the fifth most common in adult women [2]. NHL appears to occur more frequently in Western countries than in Asian populations.

Various factors associated with increased risk for B-cell NHL have been identified over the years, including occupational and environmental exposure to certain pesticides and herbicides [3], immunosuppression associated with HIV infection [4], autoimmune disorders [5], iatrogenically induced immune suppression in the post-transplant and other settings [6], family history of NHL [7], and a personal history of a prior cancer, including Hodgkin lymphoma and prior NHL [8]. In terms of infectious agents associated with aggressive B-cell NHLs, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) has a clear pathogenic role in Burkitt lymphoma, in many cases of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders, and in some cases of HIV-related aggressive B-cell lymphoma [9]. Human herpesvirus-8 viral genomes have been found in virtually all cases of primary effusion lymphomas [10]. Epidemiological studies also have linked hepatitis B and C to increased incidences of certain NHL subtypes [11–13], including primary hepatic diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Similarly, Helicobacter pylori has been associated with gastric DLBCL.

Staging and Workup

A tissue biopsy is essential in the diagnosis and management of NHL. The most significant disadvantage of fine-needle aspiration cytology is the lack of histologic architecture. The optimal specimen is an excisional biopsy; when this cannot be performed, a core needle biopsy, ideally using a 16-gauge or larger caliber needle, is the next best choice.

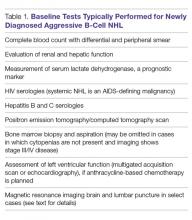

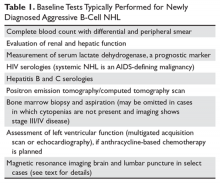

The baseline tests appropriate for most cases of newly diagnosed aggressive B-cell NHL are listed in Table 1.

Prior to the initiation of treatment, patients should always undergo a thorough cardiac and pulmonary evaluation, especially if the patient will be treated with an anthracycline or mediastinal irradiation. Central nervous system (CNS) evaluation with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and lumbar puncture is essential if there are neurological signs or symptoms. In addition, certain anatomical sites including the testicles, paranasal sinuses, kidney, adrenal glands, and epidural space have been associated with increased involvement of the CNS and may warrant MRI evaluation and lumbar puncture. Certain NHL subtypes like Burkitt lymphoma, high-grade NHL with translocations of MYC and BCL-2 or BCL-6 (double-hit lymphoma), blastoid mantle cell lymphoma, and lymphoblastic lymphoma have a high risk of CNS involvement, and patients with these subtypes need CNS evaluation.

The Lugano classification is used to stage patients with NHL [14]. This classification is based on the Ann Arbor staging system and uses the distribution and number of tumor sites to stage disease. In general, this staging system in isolation is of limited value in predicting survival after treatment. However, the Ann Arbor stage does have prognostic impact when incorporated into risk scoring systems such as the International Prognostic Index (IPI). In clinical practice, the Ann Arbor stage is useful primarily to determine eligibility for localized therapy approaches. The absence or presence of systemic symptoms such as fevers, drenching night sweats, or weight loss (> 10% of baseline over 6 months or less) is designated by A or B, respectively.

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

DLBCL is the most common lymphoid neoplasm in adults, accounting for about 25% of all NHL cases [2]. It is increasingly clear that the diagnostic category of DLBCL is quite heterogeneous in terms of morphology, genetics, and biologic behavior. A number of clinicopathologic subtypes of DLBCL exist, such as T cell/histiocyte–rich large B-cell lymphoma, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, intravascular large B-cell lymphoma, DLBCL associated with chronic inflammation, lymphomatoid granulomatosis, and EBV-positive large B-cell lymphoma, among others. Gene expression profiling (GEP) can distinguish 2 cell of origin DLBCL subtypes: the germinal center B-cell (GCB) and activated B-cell (ABC) subtypes [15].

DLBCL may be primary (de novo) or may arise through the transformation of many different types of low-grade B-cell lymphomas. This latter scenario is referred to as histologic transformation or transformed lymphoma. In some cases, patients may have a previously diagnosed low-grade B-cell NHL; in other cases, both low-grade and aggressive B-cell NHL may be diagnosed concurrently. The presence of elements of both low-grade and aggressive B-cell NHL in the same biopsy specimen is sometimes referred to as a composite lymphoma.

In the United States, incidence varies by ethnicity, with DLBCL being more common in Caucasians than other races [16]. There is a slight male predominance (55%), median age at diagnosis is 65 years [16,17] and the incidence increases with age.

Presentation, Pathology, and Prognostic Factors

The most common presentation of patients with DLBCL is rapidly enlarging lymphadenopathy, usually in the neck or abdomen. Extranodal/extramedullary presentation is seen in approximately 40% of cases, with the gastrointestinal (GI) tract being the most common site. However, extranodal DLBCL can arise in virtually any tissue [18]. Nodal DLBCL presents with symptoms related to the sites of involvement (eg, shortness of breath or chest pain with mediastinal lymphadenopathy), while extranodal DLBCL typically presents with symptoms secondary to dysfunction at the site of origin. Up to one third of patients present with constitutional symptoms (B symptoms) and more than 50% have elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) at diagnosis [19].

Approximately 40% of patients present with stage I/II disease. Of these, only a subset present with stage I, or truly localized disease (defined as that which can be contained within 1 irradiation field). About 60% of patients present with advanced (stage III–IV) disease [20]. The bone marrow is involved in about 15% to 30% of cases. DLBCL involvement of the bone marrow is associated with a less favorable prognosis. Patients with DLBCL elsewhere may have low-grade NHL involvement of the bone marrow. Referred to as discordant bone marrow involvement [21], this feature does not carry the same poor prognosis associated with transformed disease [22] or DLBCL involvement of the bone marrow [23].

DLBCL is defined as a neoplasm of large B-lymphoid cells with a diffuse growth pattern. The proliferative fraction of cells, as determined by Ki-67 staining, is usually greater than 40%, and may even exceed 90%. Lymph nodes usually demonstrate complete effacement of the normal architecture by sheets of atypical lymphoid cells. Tumor cells in DLBCL generally express pan B-cell antigens (CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79a, Pax-5) as well as CD45 and surface immunoglobulin. Between 20% and 37% of DLBCL cases express the BCL-2 protein [24], and about 70% express the BCL-6 protein [25]. C-MYC protein expression is seen in a higher percentage (~ 30%–50%) of cases of DLBCL [26].

Many factors are associated with outcome in DLBCL. The IPI score was developed in the pre-rituximab era and is a robust prognostic tool. This simple tool uses 5 easily obtained clinical factors (age > 60 years, impaired performance status, elevated LDH, > 1 extranodal site of disease, and stage III/IV disease). By summing these factors, 4 groups with distinct 5-year overall survival (OS) rates ranging from 26% to 73% were identified (Table 2).

Cytogenetic and molecular factors also predict outcome in DLBCL. The ABC subtype distinguished by GEP has consistently been shown to have inferior outcomes with first-line therapy. As GEP is not routinely available in clinical practice, immunohistochemical (IHC) approaches (eg, the Hans algorithm) have been developed that can approximate the GEP subtypes. These IHC approaches have approximately 80% concordance with GEP [28]. The 3 most common chromosomal translocations in DLBCL involve BCL-2, BCL-6 and MYC. MYC-rearranged DLBCLs have a less favorable prognosis [29,30]. Cases in which a MYC translocation occurs in combination with a BCL-2 or BCL-6 translocation are commonly referred to as double-hit lymphoma (DHL); cases with all 3 translocations are referred to as triple-hit lymphoma (THL). Both DHL and THL have a worse prognosis with standard DLBCL therapy compared to non-DHL/THL cases. In the 2016 revised WHO classification, DHL and THL are an entity technically distinct from DLBCL, referred to as high-grade B-cell lymphoma [1]. In some cases, MYC and BCL-2 protein overexpression occurs in the absence of chromosomal translocations. Cases in which MYC and BCL-2 are overexpressed (by IHC) are referred to as double expressor lymphoma (DEL), and also have inferior outcome compared with non-DEL DLBCL [31,32]. Interestingly, MYC protein expression alone does not confer inferior outcomes, unlike isolated MYC translocation, which is associated with inferior outcomes.

Treatment

First-Line Therapy. DLBCL is an aggressive disease and, in most cases, survival without treatment can be measured in weeks to months. The advent of combination chemotherapy (CHOP [cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone] or CHOP-like regimens) led to disease-free survival (DFS) rates of 35% to 40% at 3 to 5 years [33]. The addition of rituximab to CHOP (R-CHOP) has improved both progression-free surivial (PFS) and OS [34,35].

Treatment options vary for patients with localized (stage I/II) and advanced (stage III/IV) disease. Options for limited-stage DLBCL include an abbreviated course of R-CHOP (3 or 4 cycles) with involved-field radiation therapy (IFRT) versus a full course (6–8 cycles) of R-CHOP without radiation therapy (RT). Most studies comparing combined modality therapy (chemotherapy plus RT) versus chemotherapy alone were conducted in the pre-rituximab era. With the introduction of rituximab, Persky and colleagues [36] studied the use of 3 cycles of R-CHOP followed by RT, demonstrating a slightly improved OS of 92% at 4 years as compared to 88% in a historical cohort. The French LYSA/GOELAMS group performed the only direct comparison in the rituximab era (4 cycles of R-CHOP followed by RT versus 4 cycles of R-CHOP followed by 2 additional cycles of R-CHOP) and reported similar outcomes between both arms [37], with OS of 92% in the R-CHOP alone arm and 96% in the R-CHOP + RT arm (nonsignificant difference statistically). IFRT alone is not recommended other than for palliation in patients who cannot tolerate chemotherapy or combined modality therapy. Stage I and II patients with bulky disease (> 10 cm) have a prognosis similar to patients with advanced DLBCL and should be treated aggressively with 6 to 8 cycles of R-CHOP with or without RT [36].

For patients with advanced stage disease, a full course of R-CHOP-21 (6–8 cycles given on a 21-day cycle) is the standard of care. This approach results in OS rates of 70% and 60% at 2 and 5 years, respectively. For older adults unable to tolerate full-dose R-CHOP, attenuated versions of R-CHOP with decreased dose density or decreased dose intensity have been developed [38]. Numerous randomized trials have attempted to improve upon the results of R-CHOP-21 using strategies such as infusional chemotherapy (DA-EPOCH-R [etoposide, prednisone, vincristine, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, rituximab]) [39]; dose-dense therapy (R-CHOP-14); replacement of rituximab with obinutuzuimab [40]; addition of novel agents such as bortezomib [41], lenalidomide[42], or ibrutinib [43,44] to R-CHOP; and various maintenance strategies such as rituximab, lenalidomide [45], enzastaurin [46], and everolimus [47]. Unfortunately, none of these strategies has been shown to improve OS in DLBCL. In part this appears to be due to the fact that inclusion/exclusion criteria for DLBCL trials have been too strict, such that the most severely ill DLBCL patients are typically not included. As a result, the results in the control arms have ended up better than what was expected based on historical data. Efforts are underway to include all patients in future first-line DLBCL studies.

Currently, autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (auto-HCT) is not routinely used in the initial treatment of DLBCL. In the pre-rituximab era, numerous trials were conducted in DLBCL patients with high and/or high-intermediate risk disease based on the IPI score to determine if outcomes could be improved with high-dose therapy and auto-HCT as consolidation after patients achieved complete remission with first-line therapy. The results of these trials were conflicting. A 2003 meta-analysis of 11 such trials concluded that the results were very heterogeneous and showed no OS benefit [48]. More recently, the Southwestern Oncology Group published the results of a prospective trial testing the impact of auto-HCT for consolidation of aggressive NHL patients with an IPI score of 3 to 5 who achieved complete remission with first-line therapy with CHOP or R-CHOP. In this study, 75% of the patients had DLBCL and, of the B-cell NHL patients, 47% received R-CHOP. A survival benefit was seen only in the subgroup that had an IPI score of 4 or 5; a subgroup analysis restricted to those receiving R-CHOP as induction was not performed, however [49]. As a result, this area remains controversial, with most institutions not routinely performing auto-HCT for any DLBCL patients in first complete remission and some institutions considering auto-HCT in first complete remission for patients with an IPI score of 4 or 5. These studies all used the IPI score to identify high-risk patients. It is possible that the use of newer biomarkers or minimal-residual disease analysis will lead to a more robust algorithm for identifying high-risk patients and selecting patients who might benefit from consolidation of first complete remission with auto-HCT.

For patients with DHL or THL, long-term PFS with standard R-CHOP therapy is poor (20% to 40%) [50,51]. Treatment with more intensive first-line regimens such as DA-EPOCH-R, R-hyperCVAD (rituximab plus hyperfractionated cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, dexamethasone), or CODOX-M/IVAC±R (cyclophosphamide, vincristine, doxorubicin, high‐dose methotrexate/ifosfamide, etoposide, high‐dose cytarabine ± rituximab), along with CNS prophylaxis, however, has been shown to produce superior outcomes [52], with 3-year relapse-free survival rates of 88% compared to 56% for R-CHOP. For patients who achieve a complete response by PET/CT scan after intensive induction, consolidation with auto-HCT has not been shown to improve outcomes based on retrospective analysis. However for DHL/THL patients who achieve complete response after R-CHOP, PFS was improved if auto-HCT was given as consolidation of first remission [53].

Patients with DLBCL have an approximately 5% risk of subsequently developing CNS involvement. Historically (in the pre-rituximab era), patients who presented with multiple sites of extranodal disease and/or extensive bone marrow involvement and/or an elevated LDH had an increased risk (up to 20%–30%) of developing CNS involvement. In addition, patients with involvement of certain anatomical sites (testicular, paranasal sinuses, epidural space) had an increased risk of CNS disease. Several algorithms have been proposed to identify patients who should receive prophylactic CNS therapy. One of the most robust tools for this purpose is the CNS-IPI, which is a 6-point score consisting of the 5 IPI elements, plus 1 additional point if the adrenal glands or kidneys are involved. Importantly, the CNS-IPI was developed and validated in patients treated with R-CHOP-like therapy. Subsequent risk of CNS relapse was 0.6%, 3.4%, and 10.2% for those with low-, intermediate- and high-risk CNS-IPI scores, respectively [54]. A reasonable strategy, therefore, is to perform CNS prophylaxis in those with a CNS-IPI score of 4 to 6. When CNS prophylaxis is used, intrathecal methotrexate or high-dose systemic methotrexate is most frequently given, with high-dose systemic methotrexate favored over intrathecal chemotherapy given that high-dose methotrexate penetrates the brain and spinal cord parenchyma, in addition to treating the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) [55]. In contrast, intrathecal therapy only treats the CSF and requires repeated lumbar punctures or placement of an Ommaya reservoir. For DLBCL patients who present with active CSF involvement (known as lymphomatous meningitis), intrathecal chemotherapy treatments are typically given 2 or 3 times weekly until the CSF clears, followed by weekly intrathecal treatment for 4 weeks, and then monthly intrathecal treatment for 4 months [56]. For those with concurrent systemic and brain parenchymal DLBCL, a strategy of alternating R-CHOP with mid-cycle high-dose methotrexate can be successful. In addition, consolidation with high-dose therapy and auto-HCT improved survival in such patients in 1 retrospective series [57].

Relapsed/Refractory Disease. Between 30% and 40% of patients with advanced stage DLBCL will either fail to attain a remission with primary therapy (referred to as primary induction failure) or will relapse. In general, for those with progressive or relapsed disease, an updated tissue biopsy is recommended. This is especially true for patients who have had prior complete remission and have new lymph node enlargement, or those who have emergence of new sites of disease at the completion of first-line therapy.

Patients with relapsed disease are treated with systemic second-line platinum-based chemoimmunotherapy, with the usual goal of ultimately proceeding to auto-HCT. A number of platinum-based regimens have been used in this setting such as R-ICE, R-DHAP, R-GDP, R-Gem-Ox, and R-ESHAP. None of these regimens has been shown to be superior in terms of efficacy, and the choice of regimen is typically made based on the anticipated tolerance of the patient in light of comorbidities, laboratory studies, and physician preference. In the CORAL study, R-DHAP (rituximab, dexamethasone, high-dose cytarabine, cisplatin) seemed to show superior PFS in patients with the GCB subtype [58]. However, this was an unplanned subgroup analysis and R-DHAP was associated with higher renal toxicity.

Several studies have demonstrated that long-term PFS can be observed for relapsed/refractory DLBCL patients who respond to second-line therapy and then undergo high-dose therapy with auto-HCT. The Parma trial remains the only published prospective randomized trial performed in relapsed DLBCL comparing a transplant strategy to a non-transplant strategy. This study, performed in the pre-rituximab era, clearly showed a benefit in terms of DFS and OS in favor of auto-HCT versus salvage therapy alone [59]. The benefit of auto-HCT in patients treated in the rituximab era, even in patients who experience early failure (within 1 year of diagnosis), was confirmed in a retrospective analysis by the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research. In this study, a 44% 3-year PFS was seen in the early failure cohort versus 52% in the late failure cohort [60].

Some DLBCL patients are very unlikely to benefit from auto-HCT. The REFINE study focused on patients with primary induction failure or early relapse within 6 months of completing first-line therapy. Among such patients, primary progressive disease (defined as progression while still receiving first-line therapy), a high NCCN-IPI score at relapse, and MYC rearrangement were risk factors for poor PFS following auto-HCT [61]. Patients with 2 or 3 high-risk features had a 2-year OS of 10.7% compared to 74.3% for those without any high-risk features.

Allogeneic HCT (allo-HCT) is a treatment option for relapsed/refractory DLBCL. This option is more commonly considered for patients in whom an autotransplant has failed to achieve durable remission. For properly selected patients in this setting, a long-term PFS in the 30% to 40% range can be attained [62]. However, in practice, only about 20% of patients who fail auto-HCT end up undergoing allo-HCT due to rapid progression of disease, age, poor performance status, or lack of suitable donor. It has been proposed that in the coming years, allo-HCT will be utilized less commonly in this setting due to the advent of chimeric antigen receptor T-cell (CAR T) therapy.

CAR T-cell therapy genetically modifies the patient’s own T lymphocytes with a gene that encodes an antigen receptor to direct the T cells against lymphoma cells. Typically, the T cells are genetically modified and expanded in a production facility and then infused back into the patient. Axicabtagene ciloleucel is directed against the CD-19 receptor and has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of patients with DLBCL who have failed 2 or more lines of systemic therapy. Use of CAR-T therapy in such patients was examined in a multicenter trial (ZUMA-1), which reported a 54% complete response rate and 52% OS rate at 18 months.63 CAR-T therapy is associated with serious side effects such as cytokine release syndrome, neurological toxicities, and prolonged cytopenias. While there are now some patients with ongoing remission 2 or more years after undergoing CAR-T therapy, it remains uncertain what proportion of patients have been truly cured with this modality. Nevertheless, this new treatment option remains a source of optimism for relapsed and refractory DLBCL patients.

Primary Mediastinal Large B-Cell Lymphoma

Primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMBCL) is a form of DLBCL arising in the mediastinum from the thymic B cell. It is an uncommon entity and has clinical and pathologic features distinct from systemic DLBCL [64]. PMBCL accounts for 2% of all NHLs and about 7% of all DLBCL [20]. It typically affects women in the third to fourth decade of life.

Presentation and Prognostic Features

PMBCL usually presents as a locally invasive anterior mediastinal mass, often with a superior vena cava syndrome which may or may not be clinically obvious [64]. Other presentations include pericardial tamponade, thrombosis of neck veins, and acute airway obstruction. About 80% of patients present with bulky (> 10 cm) stage I or II disease [65], with distant spread uncommon on presentation. Morphologically and on GEP, PMBL has a profile more similar to classical Hodgkin lymphoma (cHL) than non-mediastinal DLBCL [66]. PMBL is distinguished from cHL by immunophenotyping: unlike cHL, PMBCL has pan B cell markers, rarely expresses CD15, and has weak CD30.

Poor prognostic features in PMBCL are Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status greater than 2, pericardial effusion, bulky disease, and elevated serum LDH. The diagnosis of PMBCL can be difficult because the tumor is often encased with extensive fibrosis and necrosis. As a result, a needle biopsy may not yield sufficient tissue, thus making a surgical biopsy often the only viable way to obtain sufficient tissue.

Treatment

Early series suggested that PMBCL is unusually aggressive, with a poor prognosis [67]. This led to studies using more aggressive chemotherapy regimens (often in combination with mediastinal radiation) as well as upfront auto-HCT [68–70]. The addition of rituximab to treatment regimens significantly improved outcomes in PMBCL. For example, a subgroup analysis of the PMBCL patients in the MinT trial revealed a 3-year event-free survival (EFS) of 78% [71] when rituximab was combined with CHOP. Because of previous reports demonstrating radiosensitivity of PMBL, radiation was traditionally sequenced into treatment regimens for PMBL. However, this is associated with higher long-term toxicities, often a concern in PMBCL patients given that the disease frequently affects younger females, and given that breast tissue will be in the radiation field. For patients with a strong personal or family history of breast cancer or cardiovascular disease, these concerns are even more significant. More recently, the DA-EPOCH-R regimen has been shown to produce very high rates (80%–90%) of long-term DFS, without the need for mediastinal radiation in most cases [72,73]. For patients receiving R-CHOP, consolidation with mediastinal radiation is still commonly given. This approach also leads to high rates of long-term remission and, although utilizing mediastinal radiation, allows for less intensive chemotherapy. Determining which approach is most appropriate for an individual patient requires an assessment of the risks of each treatment option for that patient. A randomized trial by the International Extranodal Lymphoma Study Group (IELSG37) is evaluating whether RT may be safely omitted in PMBCL patients who achieve a complete metabolic response after R-CHOP.

Most relapses of PMBCL occur within the first 1 to 2 years and often present with extranodal disease in various organs. For those with relapsed or refractory disease, high-dose chemotherapy followed by auto-HCT provides 5-year survival rates of 50% to 80% [74–76] In a phase 1b trial evaluating the role of pembrolizumab in relapsed/refractory patients (KEYNOTE-13), 7 of 17 PMBCL patients achieved responses, with an additional 6 demonstrating stable disease [77]. This provides an additional option for patients who might be too weak to undergo auto-HCT or for those who relapse following auto-HCT.

Mantle Cell Lymphoma

The name mantle cell lymphoma (MCL) is based on the presumed normal cell counterpart to MCL, which is believed to be found in the mantle zone surrounding germinal center follicles. It represents approximately 6% of all NHL cases in the United States and Europe [78] MCL occurs at a median age of 63 to 68 years and has a male predominance.

Presentation and Prognostic Features

Patients can present with a broad spectrum of clinical features, and most patients (70%) present with advanced disease [79]. Up to one third of patients have B symptoms, with most demonstrating lymphadenopathy and bone marrow involvement. Approximately 25% present with extranodal disease as the primary presentation (eg, GI tract, pleura, breast, or orbits). MCL can involve any part of the GI tract and often presents as polypoid lesions.

Histologically, the pattern of MCL may be diffuse, nodular, mantle zone, or a combination of the these; morphologically, MCL can range from small, more irregular lymphocytes to lymphoblast-like cells. Blastoid and pleomorphic variants of MCL have a higher proliferation index and a more aggressive clinical course than other variants. MCL is characterized by the expression of pan B cell antigens (CD19+, CD20+) with coexpression of the T-cell antigen CD5, lack of CD23 expression, and nuclear expression of cyclin D1. Nuclear staining for cyclin D1 is present in more than 98% of cases [80]. In rare cases, CD5 or cyclin D1 may be negative [80]. Most MCL cases have a unique translocation that fuses the immunoglobulin heavy chain gene promoter (14q32) to the promoter of the BCL-1 gene (11q13), which encodes the cyclin D1 protein. This translocation is not unique to MCL and can be present in multiple myeloma as well. Interestingly, cyclin D1 is overproduced in cases lacking t(11:14), likely from other point mutations resulting in its overexpression [81]. Cyclin D1–negative tumors overexpress cyclin D2 or D3, with no apparent difference in clinical behavior or outcome [82]. In cyclin D1–negative cases, SOX11 expression may help with diagnosis [83]. A proliferation rate greater than 30% (as measured by Ki-67 staining), low SOX11 expression, and presence of p53 mutations have all been associated with adverse outcome.

In a minority of cases, MCL follows an indolent clinical course. For the remainder, however, MCL is an aggressive disease that generally requires treatment soon after diagnosis. When initially described in the 1980s and 1990s, treatment of MCL was characterized by low complete response rates, short durations of remission, repeated recurrences, and a median survival in the 2- to 5-year range [84]. In recent years, intensive regimens incorporating rituximab and high-dose cytarabine with or without auto-HCT have been developed and are associated with high complete response rates and median duration of first remission in the 6- to 9-year range [85–87]. Several prognostic indices have been applied to patients with MCL, including the IPI, the Follicular Lymphoma International Prognostic Index , and the Mantle Cell Lymphoma International Prognostic Index (MIPI). The MIPI was originally described based on a cohort from the period 1996 to 2004 [88], and subsequently confirmed in a separate cohort of 958 patients with MCL treated on prospective trials between 2004 and 2010 [89]. The MIPI score can identify 3 risk groups with significant survival differences (83%, 63%, and 34% survival at 5 years). A refined version of the MIPI score, the combined MIPI or MIPI-c, incorporates proliferation rate and is better able to stratify patients [90]. The blastoid variant of MCL follows a more aggressive clinical course and is associated with a high proliferation rate, shorter remissions, and a higher rate of CNS involvement [91].

In most patients, MCL is an aggressive disease with a short OS without treatment. A subset of patients may have a more indolent course [92], but unfortunately reliable factors that identify this group at the time of diagnosis are not available. Pretreatment evaluation is as with other lymphomas, with lumbar puncture and MRI of the brain also recommended for patients with the blastoid variant. For those presenting with GI symptoms, endoscopy is recommended as part of the initial evaluation as well.

Treatment

First-line Therapy. For patients under age 65 to 70 years with a good performance status and few comorbidities, an intensive induction regimen (such as R-CHOP/R-DHAP, Maxi-R-CHOP/R-araC, or R-DHAP) followed by consolidation with auto-HCT is commonly given, with a goal of achieving a durable (6–9 year) first remission [87,93,94]. Auto-HCT is now routinely followed by 3 years of maintenance rituximab based on the survival benefit seen in the recent LYSA trial [93]. At many centers, auto-HCT in first remission is a standard of care, with the greatest benefit seen in patients who have achieved a complete remission with no more than 2 lines of chemotherapy [95]. However, there remains some controversy about whether all patients truly benefit from auto-HCT in first remission, and current research efforts are focused on identifying patients most likely to benefit from auto-HCT and incorporation of new agents into first-line regimens. For patients who are not candidates for auto-HCT, bendamustine plus rituximab (BR) or R-CHOP alone or followed by maintenance rituximab is a reasonable approach [96]. Based on the StiL and BRIGHT trials, BR seems to have less toxicity and higher rates of response with no difference in OS when compared to R-CHOP [97,98].

In summary, dose-intense induction chemotherapy with consolidative auto-HCT results in high rates of long-term remission and can be considered in MCL patients who lack significant comorbidities and who understand the risks and benefits of this approach. For other patients, the less aggressive frontline approaches are more appropriate.

Relapsed/Refractory Disease

Despite initial high response rates, most patients with MCL will eventually relapse. For example, most patients given CHOP or R-CHOP alone as first-line therapy will relapse within 2 years [99]. In recent years, a number of therapies have emerged for relapsed/refractory MCL; however, the optimal sequencing of these is unclear. FDA-approved options for relapsed/refractory MCL include the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib [100,101], the BTK inhibitors ibrutinib [102,103] and acalabrutinib [104], and the immunomodulatory agent lenalidomide [105].

Auto-HCT can be considered for patients who did not undergo auto-HCT as part of first-line therapy and who had a reasonably long first remission [95]. Allo-HCT has curative potential in MCL with good evidence of a graft-versus-lymphoma effect. With a matched related or matched unrelated donor, the chance for treatment-related mortality is 15% to 25% at 1 to 2 years, with a 50% to 60% chance for long-term PFS. However, given the risk of treatment-related mortality and graft-versus-host disease, this option is typically reserved for patients with early relapse after auto-HCT, multiple relapses, or relatively chemotherapy-unresponsive disease [95,106]. A number of clinical trials for relapsed/refractory MCL are ongoing, and participation in these is encouraged whenever possible.

Burkitt Lymphoma

Burkitt lymphoma is a rare, aggressive and highly curable subtype of NHL. It can occur at any age, although peak incidence is in the first decade of life. There are 3 distinct clinical forms of Burkitt lymphoma [107]. The endemic form is common in African children and commonly involves the jaw and kidneys. The sporadic (nonendemic) form accounts for 1% to 2% of all lymphomas in the United States and Western Europe and usually has an abdominal presentation. The immunodeficiency-associated form is commonly seen in HIV patients with a relatively preserved CD4 cell count.

Patients typically present with rapidly growing masses and tumor lysis syndrome. CNS and bone marrow involvement are common. Burkitt lymphoma cells are high-grade, rapidly proliferating medium-sized cells with a monomorphic appearance. Biopsies show a classic histological appearance known as a “starry sky pattern” due to benign macrophages engulfing debris resulting from apoptosis. It is derived from a germinal center B cell and has distinct oncogenic pathways. Translocations such as t(8;14), t(2;8) or t(8;22) juxtapose the MYC locus with immunoglobulin heavy or light chain loci and result in MYC overexpression. Burkitt lymphoma is typically CD10-positive and BCL-2-negative, with a MYC translocation and a proliferation rate greater than 95%.

With conventional NHL regimens, Burkitt lymphoma had a poor prognosis, with complete remission in the 30% to 70% range and low rates of long-term remission. With the introduction of short-term, dose-intensive, multiagent chemotherapy regimens (adapted from pediatric acute lymphoblastic leukemia [ALL] regimens), the complete remission rate improved to 60% to 90% [107]. Early stage disease (localized or completely resected intra-abdominal disease) can have complete remission rates of 100%, with 2- to 5-year freedom-from-progression rates of 95%. CNS prophylaxis, including high-dose methotrexate, high-dose cytarabine, and intrathecal chemotherapy, is a standard component of Burkitt lymphoma regimens (CNS relapse rates can reach 50% without prophylactic therapy). Crucially, relapse after 1 to 2 years is very rare following complete response to induction therapy. Classically, several intensive regimens have been used for Burkitt lymphoma. In recent years, the most commonly used regimens have been the modified Magrath regimen of R-CODOX-M/IVAC and R-hyperCVAD. DA-EPOCH-R has also been used, typically for older, more frail, or HIV-positive patients. However, at the American Society of Hematology 2017 annual meeting, results from the NCI 9177 trial were presented which validated, in a prospective multi-center fashion, the use of DA-EPOCH-R in all Burkitt lymphoma patients [108]. In NCI 9177, low-risk patients (defined as normal LDH, ECOG performance score 0 or 1, ≤ stage II, and no tumor lesion > 7 cm) received 2 cycles of DA-EPOCH-R without intrathecal therapy followed by PET. If interim PET was negative, low-risk patients then received 1 more cycle of DA-EPOCH-R. High-risk patients with negative brain MRI and CSF cytology/flow cytometry received 2 cycles of DA-EPOCH-R with intrathecal therapy (2 doses per cycle) followed by PET. Unless interim PET showed progression, high-risk patients received 4 additional cycles of DA-EPOCH-R including methotrexate 12 mg intrathecally on days 1 and 5 (8 total doses). With a median follow-up of 36 months, this regimen resulted in an EFS of 85.7%. As expected, patients with CNS, marrow, or peripheral blood involvement fared worse. For those without CNS, marrow, or peripheral blood involvement, the results were excellent, with an EFS of 94.6% compared to 62.8% for those with CNS, bone marrow, or blood involvement at diagnosis.

Although no standard of care has been defined, patients with relapsed/refractory Burkitt lymphoma are often given standard second-line aggressive NHL regimens (eg, R-ICE); for those with chemosensitive disease, auto- or allo-HCT is often pursued, with long-term remissions possible following HCT [109].

Lymphoblastic Lymphoma

Lymphoblastic lymphoma (LBL) is a rare disease postulated to arise from precursor B or T lymphoblasts at varying stages of differentiation. Accounting for approximately 2% of all NHLs, 85% to 90% of all cases have a T-cell phenotype, while B-cell LBL comprises approximately 10% to 15% of cases. LBL and ALL are thought to represent the same disease entity, but LBL has been arbitrarily defined as cases with lymph node or mediastinal disease. Those with significant (> 25%) bone marrow or peripheral blood involvement are classified as ALL.

Precursor T-cell LBL patients are usually adolescent and young males who commonly present with a mediastinal mass and peripheral lymphadenopathy. Precursor B-cell LBL patients are usually older (median age 39 years) with peripheral lymphadenopathy and extranodal involvement. Mediastinal involvement with B-cell LBL is uncommon, and there is no male predominance. LBL has a propensity for dissemination to the bone marrow and CNS.

Morphologically, the tumor cells are medium sized, with a scant cytoplasm and finely dispersed chromatin. Mitotic features and apoptotic bodies are present since it is a high-grade malignancy. The lymphoblasts are typically positive for CD7 and either surface or cytoplasmic CD3. Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase expression is a defining feature. Other markers such as CD19, CD22, CD20, CD79a, CD45, and CD10 are variably expressed. Poor prognostic factors in T-cell LBL are female gender, age greater than 35 years, complex cytogenetics, and lack of a matched sibling donor.

Regimens for LBL are based on dose-dense, multi-agent protocols used in ALL. Most of these regimens are characterized by intensive remission-induction chemotherapy, CNS prophylaxis, a phase of consolidation therapy, and a prolonged maintenance phase, often lasting for 12 to 18 months with long-term DFS rates of 40% to 70% [110,111]. High-dose therapy with auto-HCT or allo-HCT in first complete response has been evaluated in an attempt to reduce the incidence of relapse [112]. However, the intensity of primary chemotherapy appears to be a stronger determinant of long-term survival than the use of HCT as consolidation. As a result, HCT is not routinely applied to patients in first complete remission following modern induction regimens. After relapse, prognosis is poor, with median survival rates of 6 to 9 months with conventional chemotherapy, although long-term survival rates of 30% and 20%, respectively, are reported after HCT in relapsed and primary refractory disease [113].

Treatment options in relapsed disease are limited. Nelarabine can produce responses in up to 40% of relapsed/refractory LBL/ALL patients [114]. For the minority of LBL patients with a B-cell phenotype, emerging options for relapsed/refractory LBL/ALL such as inotuzumab, blinatumomab, or anti-CD19 CAR T-cell therapy should be considered. These are not options for the majority who have a T-cell phenotype, and treatment options for these patients are limited to conventional relapsed/refractory ALL and aggressive NHL regimens.

Summary

Aggressive NHLs are characterized by rapid clinical progression without therapy. However, a significant proportion of patients are cured with appropriate combination chemotherapy or combined modality (chemotherapy + RT) regimens. In contrast, the indolent lymphomas have a relatively good prognosis (median survival of 10 years or longer) but usually are not curable in advanced clinical stages. Overall 5-year survival for aggressive NHLs with current treatment is approximately 50% to 60%, with relapses typically occurring within the first 5 years. Treatment strategies for relapsed patients offer some potential for cure; however, clinical trial participation should be encouraged whenever possible to investigate new approaches for improving outcomes in this patient population.

Corresponding author: Timothy S. Fenske, MD, Division of Hematology & Oncology, Medical College of Wisconsin, 9200 W. Wisconsin Ave., Milwaukee, WI 53226.

1. Swerdlow, SH, Campo E, Harris NL, et al. WHO classification of tumours of haematopoietic and lymphoid tissues. Revised 4th edition. Lyon, France: World Health Organization; 2017.

2. Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. www.seer.cancer.gov. Research Data 2017.

3. Boffetta P, de Vocht F. Occupation and the risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 2007;16:369–72.

4. Bower M. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome-related systemic non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Br J Haematol 2001;112:863–73.

5. Ekstrom Smedby K, Vajdic CM, Falster M, et al. Autoimmune disorders and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma subtypes: a pooled analysis within the InterLymph Consortium. Blood 2008;111:4029–38.

6. Clarke CA, Morton LM, Lynch C, et al. Risk of lymphoma subtypes after solid organ transplantation in the United States. Br J Cancer 2013;109:280–8.

7. Wang SS, Slager SL, Brennan P, et al. Family history of hematopoietic malignancies and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL): a pooled analysis of 10 211 cases and 11 905 controls from the International Lymphoma Epidemiology Consortium (InterLymph). Blood 2007;109:3479–88.

8. Dong C, Hemminki K. Second primary neoplasms among 53 159 haematolymphoproliferative malignancy patients in Sweden, 1958–1996: a search for common mechanisms. Br J Cancer 2001;85:997–1005.

9. Hummel M, Anagnostopoulos I, Korbjuhn P, Stein H. Epstein-Barr virus in B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas: unexpected infection patterns and different infection incidence in low- and high-grade types. J Pathol 1995;175:263–71.

10. Cesarman E, Chang Y, Moore PS, et al. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in AIDS-related body-cavity-based lymphomas. N Engl J Med 1995;332:1186–91.

11. Viswanatha DS, Dogan A. Hepatitis C virus and lymphoma. J Clin Pathol 2007;60:1378–83.

12. Engels EA, Cho ER, Jee SH. Hepatitis B virus infection and risk of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in South Korea: a cohort study. Lancet Oncol 2010;11:827–34.

13. Marcucci F, Mele A. Hepatitis viruses and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: epidemiology, mechanisms of tumorigenesis, and therapeutic opportunities. Blood 2011;117:1792–8.

14. Cheson BD, Fisher RI, Barrington SF, et al. Recommendations for initial evaluation, staging, and response assessment of Hodgkin and non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the Lugano classification. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:3059–68.

15. Rosenwald A, Wright G, Chan WC, et al. The use of molecular profiling to predict survival after chemotherapy for diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2002;346:1937–47.

16. Teras LR, DeSantis CE, Cerhan JR, et al. 2016 US lymphoid malignancy statistics by World Health Organization subtypes. CA Cancer J Clin 2016;66:443–59.

17. Morton LM, Wang SS, Devesa SS, et al. Lymphoma incidence patterns by WHO subtype in the United States, 1992-2001. Blood 2006;107:265–76.

18. Møller MB, Pedersen NT, Christensen BE. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: clinical implications of extranodal versus nodal presentation--a population-based study of 1575 cases. Br J Haematol 2004;124:151–9.

19. Armitage JO, Weisenburger DD. New approach to classifying non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas: clinical features of the major histologic subtypes. Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Classification Project. J Clin Oncol 1998;16:2780–95.

20. A clinical evaluation of the International Lymphoma Study Group classification of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. The Non-Hodgkin’s Lymphoma Classification Project. Blood 1997;89:3909–18.

21. Sehn LH, Scott DW, Chhanabhai M, et al. Impact of concordant and discordant bone marrow involvement on outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:1452–7.

22. Fisher DE, Jacobson JO, Ault KA, Harris NL. Diffuse large cell lymphoma with discordant bone marrow histology. Clinical features and biological implications. Cancer 1989;64:1879–87.

23. Yao Z, Deng L, Xu-Monette ZY, et al. Concordant bone marrow involvement of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma represents a distinct clinical and biological entity in the era of immunotherapy. Leukemia 2018;32:353–63.

24. Gascoyne RD, Adomat SA, Krajewski S, et al. Prognostic significance of Bcl-2 protein expression and Bcl-2 gene rearrangement in diffuse aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. Blood 1997;90:244–51.

25. Skinnider BF, Horsman DE, Dupuis B, Gascoyne RD. Bcl-6 and Bcl-2 protein expression in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and follicular lymphoma: correlation with 3q27 and 18q21 chromosomal abnormalities. Hum Pathol 1999;30:803–8.

26. Chisholm KM, Bangs CD, Bacchi CE, et al. Expression profiles of MYC protein and MYC gene rearrangement in lymphomas. Am J Surg Pathol 2015;39:294–303.

27. Zhou Z, Sehn LH, Rademaker AW, et al. An enhanced International Prognostic Index (NCCN-IPI) for patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated in the rituximab era. Blood 2014;123:837–42.

28. Hans CP, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, et al. Confirmation of the molecular classification of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma by immunohistochemistry using a tissue microarray. Blood 2004;103:275–82.

29. Horn H, Ziepert M, Becher C, et al. MYC status in concert with BCL2 and BCL6 expression predicts outcome in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2013;121:2253–63.

30. Barrans S, Crouch S, Smith A, et al. Rearrangement of MYC is associated with poor prognosis in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated in the era of rituximab. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:3360–5.

31. Hu S, Xu-Monette ZY, Tzankov A, et al. MYC/BCL2 protein coexpression contributes to the inferior survival of activated B-cell subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma and demonstrates high-risk gene expression signatures: a report from The International DLBCL Rituximab-CHOP Consortium Program. Blood 2013;121:4021–31.

32. Green TM, Young KH, Visco C, et al. Immunohistochemical double-hit score is a strong predictor of outcome in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:3460–7.

33. Fisher RI, Gaynor ER, Dahlberg S, et al. Comparison of a standard regimen (CHOP) with three intensive chemotherapy regimens for advanced non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med 1993;328:1002–6.

34. Pfreundschuh M, Kuhnt E, Trümper L, et al. CHOP-like chemotherapy with or without rituximab in young patients with good-prognosis diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma: 6-year results of an open-label randomised study of the MabThera International Trial (MInT) Group. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:1013–22.

35. Coiffier B, Lepage E, Brière J, et al. CHOP chemotherapy plus rituximab compared with CHOP alone in elderly patients with diffuse large-B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2002;346:235–42.

36. Persky DO, Unger JM, Spier CM, et al. Phase II study of rituximab plus three cycles of CHOP and involved-field radiotherapy for patients with limited-stage aggressive B-cell lymphoma: Southwest Oncology Group study 0014. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:2258–63.

37. Lamy T, Damaj G, Soubeyran P, et al. R-CHOP 14 with or without radiotherapy in nonbulky limited-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2018;131:174–81.

38. Peyrade F, Jardin F, Thieblemont C, et al. Attenuated immunochemotherapy regimen (R-miniCHOP) in elderly patients older than 80 years with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a multicentre, single-arm, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol 2011;12:460–8.

39. Wilson WH, sin-Ho J, Pitcher BN, et al. Phase III randomized study of R-CHOP versus DA-EPOCH-R and molecular analysis of untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: CALGB/Alliance 50303. Blood 2016;128:469 LP-469. 38.

40. Vitolo U, Trne˘ný M, Belada D, et al. Obinutuzumab or rituximab plus cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone in previously untreated diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:3529–37.

41. Leonard JP, Kolibaba KS, Reeves JA, et al. Randomized phase II study of R-CHOP with or without bortezomib in previously untreated patients with non-germinal center B-cell-like diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:3538–46.

42. Nowakowski GS, LaPlant B, Macon WR, et al. Lenalidomide combined with R-CHOP overcomes negative prognostic impact of non-germinal center B-cell phenotype in newly diagnosed diffuse large B-Cell lymphoma: a phase II study. J Clin Oncol 2015;33:251–7.

43. Younes A, Thieblemont C, Morschhauser F, et al. Combination of ibrutinib with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) for treatment-naive patients with CD20-positive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma: a non-randomised, phase 1b study. Lancet Oncol 2014;15:1019–26.

44. Younes A, Zinzani PL, Sehn LH, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study of ibrutinib in combination with rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone (R-CHOP) in subjects with newly diagnosed nongerminal center B-cell subtype of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). J Clin Oncol 2014;32(15_suppl):TPS8615.

45. Delarue R, Tilly H, Mounier N, et al. Dose-dense rituximab-CHOP compared with standard rituximab-CHOP in elderly patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (the LNH03-6B study): a randomised phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:525–33.

46. Leppä S, Fayad LE, Lee J-J, et al. A phase III study of enzastaurin in patients with high-risk diffuse large B cell lymphoma following response to primary treatment: the Prelude trial. Blood 2013;122:371 LP-371.

47. Witzig TE, Tobinai K, Rigacci L, et al. Adjuvant everolimus in high-risk diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: final results from the PILLAR-2 randomized phase III trial. Ann Oncol 2018;29:707–14.

48. Strehl J, Mey U, Glasmacher A, et al. High-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation as first-line therapy in aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma: a meta-analysis. Haematologica 2003;88:1304–15.

49. Stiff PJ, Unger JM, Cook JR, et al. Autologous transplantation as consolidation for aggressive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2013;369:1681–90.

50. Oki Y, Noorani M, Lin P, et al. Double hit lymphoma: the MD Anderson Cancer Center clinical experience. Br J Haematol 2014;166:891–901.

51. Petrich AM, Gandhi M, Jovanovic B, et al. Impact of induction regimen and stem cell transplantation on outcomes in double-hit lymphoma: a multicenter retrospective analysis. Blood 2014;124:2354–61.

52. Howlett C, Snedecor SJ, Landsburg DJ, et al. Front-line, dose-escalated immunochemotherapy is associated with a significant progression-free survival advantage in patients with double-hit lymphomas: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Haematol 2015;170:504–14.

53. Landsburg DJ, Falkiewicz MK, Maly J, et al. Outcomes of patients with double-hit lymphoma who achieve first complete remission. J Clin Oncol 2017;35:2260–7.

54. Schmitz N, Zeynalova S, Nickelsen M, et al. CNS International Prognostic Index: a risk model for CNS relapse in patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma treated with R-CHOP. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:3150–6.

55. Abramson JS, Hellmann M, Barnes JA, et al. Intravenous methotrexate as central nervous system (CNS) prophylaxis is associated with a low risk of CNS recurrence in high-risk patients with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Cancer 2010;116:4283–90.

56. Dunleavy K, Roschewski M, Abramson JS, et al. Risk-adapted therapy in adults with Burkitt lymphoma: updated results of a multicenter prospective phase II study of DA-EPOCH-R. Hematol Oncol 2017;35(S2):133–4.

57. Damaj G, Ivanoff S, Coso D, et al. Concomitant systemic and central nervous system non-Hodgkin lymphoma: the role of consolidation in terms of high dose therapy and autologous stem cell transplantation. A 60-case retrospective study from LYSA and the LOC network. Haematologica 2015;100:1199–206.

58. Thieblemont C, Briere J, Mounier N, et al. The germinal center/activated B-cell subclassification has a prognostic impact for response to salvage therapy in relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma: a bio-CORAL study. J Clin Oncol 2011;29:4079–87.

59. Philip T, Guglielmi C, Hagenbeek A, et al. Autologous bone marrow transplantation as compared with dalvage vhemotherapy in relapses of chemotherapy-densitive non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. N Engl J Med 1995;333:1540–5.

60. Hamadani M, Hari PN, Zhang Y, et al. Early failure of frontline rituximab-containing chemo-immunotherapy in diffuse large B cell lymphoma does not predict futility of autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2014;20:1729–36.

61. Costa LJ, Maddocks K, Epperla N, et al. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with primary treatment failure: Ultra-high risk features and benchmarking for experimental therapies. Am J Hematol 2017;92:e24615.

62. Fenske TS, Ahn KW, Graff TM, et al. Allogeneic transplantation provides durable remission in a subset of DLBCL patients relapsing after autologous transplantation. Br J Haematol 2016;174:235–48.

63. Neelapu SS, Locke FL, Bartlett NL, et al. Axicabtagene ciloleucel CAR T-cell therapy in refractory large B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2017;377:2531–44.

64. van Besien K, Kelta M, Bahaguna P. Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma: a review of pathology and management. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:1855–64.

65. Savage KJ, Al-Rajhi N, Voss N, et al. Favorable outcome of primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma in a single institution: the British Columbia experience. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol 2006;17:123–30.

66. Rosenwald A, Wright G, Leroy K, et al. Molecular diagnosis of primary mediastinal B cell lymphoma identifies a clinically favorable subgroup of diffuse large B cell lymphoma related to Hodgkin lymphoma. J Exp Med 2003;198:851–62.

67. Lavabre-Bertrand T, Donadio D, Fegueux N, et al. A study of 15 cases of primary mediastinal lymphoma of B-cell type. Cancer 1992;69:2561–6.

68. Lazzarino M, Orlandi E, Paulli M, et al. Treatment outcome and prognostic factors for primary mediastinal (thymic) B-cell lymphoma: a multicenter study of 106 patients. J Clin Oncol 1997;15:1646–53.

69. Zinzani PL, Martelli M, Magagnoli M, et al. Treatment and clinical management of primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma with sclerosis: MACOP-B regimen and mediastinal radiotherapy monitored by (67)Gallium scan in 50 patients. Blood 1999;94:3289–93.

70. Todeschini G, Secchi S, Morra E, et al. Primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMLBCL): long-term results from a retrospective multicentre Italian experience in 138 patients treated with CHOP or MACOP-B/VACOP-B. Br J Cancer 2004;90:372–6.

71. Rieger M, Osterborg A, Pettengell R, et al. Primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma treated with CHOP-like chemotherapy with or without rituximab: results of the Mabthera International Trial Group study. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol 2011;22:664–70.

72. Shah NN, Szabo A, Huntington SF, et al. R-CHOP versus dose-adjusted R-EPOCH in frontline management of primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma: a multi-centre analysis. Br J Haematol 2018;180:534–44.

73. Dunleavy K, Pittaluga S, Maeda LS, et al. Dose-adjusted EPOCH-rituximab therapy in primary mediastinal B-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1408–16.

74. Aoki T, Shimada K, Suzuki R, et al. High-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation for relapsed/refractory primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Blood Cancer J 2015;5:e372–e372.

75. Sehn LH, Antin JH, Shulman LN, et al. Primary diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the mediastinum: outcome following high-dose chemotherapy and autologous hematopoietic cell transplantation. Blood 1998;91:717–23.

76. Kuruvilla J, Pintilie M, Tsang R, et al. Salvage chemotherapy and autologous stem cell transplantation are inferior for relapsed or refractory primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma compared with diffuse large B-cell lymphoma. Leuk Lymphoma 2008;49:1329–36.

77. Zinzani PL, Ribrag V, Moskowitz CH, et al. Safety and tolerability of pembrolizumab in patients with relapsed/refractory primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma. Blood 2017;130:267–70.

78. Smith A, Howell D, Patmore R, et al. Incidence of haematological malignancy by sub-type: a report from the Haematological Malignancy Research Network. Br J Cancer 2011;105:1684–92.

79. Argatoff LH, Connors JM, Klasa RJ, et al. Mantle cell lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study of 80 cases. Blood 1997;89:2067–78.

80. Zukerberg LR, Yang WI, Arnold A, Harris NL. Cyclin D1 expression in non-Hodgkin’s lymphomas. Detection by immunohistochemistry. Am J Clin Pathol 1995;103:756–60.

81. Wiestner A, Tehrani M, Chiorazzi M, et al. Point mutations and genomic deletions in CCND1 create stable truncated cyclin D1 mRNAs that are associated with increased proliferation rate and shorter survival. Blood 2007;109:4599–606.

82. Fu K, Weisenburger DD, Greiner TC, et al. Cyclin D1-negative mantle cell lymphoma: a clinicopathologic study based on gene expression profiling. Blood 2005;106:4315–21.

83. Mozos A, Royo C, Hartmann E, et al. SOX11 expression is highly specific for mantle cell lymphoma and identifies the cyclin D1-negative subtype. Haematologica 2009;94:1555–62.

84. Norton AJ, Matthews J, Pappa V, et al. Mantle cell lymphoma: Natural history defined in a serially biopsied population over a 20-year period. Ann Oncol 1995;6:249–56.

85. Chihara D, Cheah CY, Westin JR, et al. Rituximab plus hyper-CVAD alternating with MTX/Ara-C in patients with newly diagnosed mantle cell lymphoma: 15-year follow-up of a phase II study from the MD Anderson Cancer Center. Br J Haematol 2016;172:80–8.

86. Delarue R, Haioun C, Ribrag V, et al. CHOP and DHAP plus rituximab followed by autologous stem cell transplantation in mantle cell lymphoma: a phase 2 study from the Groupe d’Etude des Lymphomes de l’Adulte. Blood 2013;121:48–53.

87. Eskelund CW, Kolstad A, Jerkeman M, et al. 15-year follow-up of the Second Nordic Mantle Cell Lymphoma trial (MCL2): prolonged remissions without survival plateau. Br J Haematol 2016;175:410–8.

88. Hoster E, Dreyling M, Klapper W, et al. A new prognostic index (MIPI) for patients with advanced-stage mantle cell lymphoma. Blood 2008;111:558–65.

89. Hoster E, Klapper W, Hermine O, et al. Confirmation of the mantle-cell lymphoma International Prognostic Index in randomized trials of the European Mantle-Cell Lymphoma Network. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:1338–46.

90. Hoster E, Rosenwald A, Berger F, et al. Prognostic value of Ki-67 index, cytology, and growth pattern in mantle-cell lymphoma: Results from randomized trials of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. J Clin Oncol 2016;34:1386–94.

91. Bernard M, Gressin R, Lefrère F, et al. Blastic variant of mantle cell lymphoma: a rare but highly aggressive subtype. Leukemia 2001;15:1785–91.

92. Martin P, Chadburn A, Christos P, et al. Outcome of deferred initial therapy in mantle-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:1209–13.

93. Le Gouill S, Thieblemont C, Oberic L, et al. Rituximab after autologous stem-cell transplantation in mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 2017 Sep 28;377(13):1250–60.

94. Hermine O, Hoster E, Walewski J, et al. Addition of high-dose cytarabine to immunochemotherapy before autologous stem-cell transplantation in patients aged 65 years or younger with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL Younger): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial of the European Mantle Cell Lymphoma Network. Lancet 2016;388:565–75.

95. Fenske TS, Zhang M-J, Carreras J, et al. Autologous or reduced-intensity conditioning allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation for chemotherapy-sensitive mantle-cell lymphoma: analysis of transplantation timing and modality. J Clin Oncol 2014;32:273–81.

96. Kluin-Nelemans HC, Hoster E, Hermine O, et al. Treatment of older patients with mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2012;367:520–31.

97. Flinn IW, van der Jagt R, Kahl BS, et al. Randomized trial of bendamustine-rituximab or R-CHOP/R-CVP in first-line treatment of indolent NHL or MCL: the BRIGHT study. Blood 2014;123:2944–52.

98. Rummel MJ, Niederle N, Maschmeyer G, et al. Bendamustine plus rituximab versus CHOP plus rituximab as first-line treatment for patients with indolent and mantle-cell lymphomas: an open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 3 non-inferiority trial. Lancet 2013;381:1203–10.

99. Lenz G, Dreyling M, Hoster E, et al. Immunochemotherapy with rituximab and cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone significantly improves response and time to treatment failure, but not long-term outcome in patients with previously untreated mantle cell lymphoma: results of a prospective randomized trial of the German Low Grade Lymphoma Study Group (GLSG). J Clin Oncol 2005;23:1984–92.

100. Belch A, Kouroukis CT, Crump M, et al. A phase II study of bortezomib in mantle cell lymphoma: the National Cancer Institute of Canada Clinical Trials Group trial IND.150. Ann Oncol Off J Eur Soc Med Oncol 2007;18:116–21.

101. Fisher RI, Bernstein SH, Kahl BS, et al. Multicenter phase II study of bortezomib in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2006;24:4867–74.

102. Dreyling M, Jurczak W, Jerkeman M, et al. Ibrutinib versus temsirolimus in patients with relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma: an international, randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet 2016;387:770–8.

103. Wang ML, Rule S, Martin P, Goy A, et al. Targeting BTK with ibrutinib in relapsed or refractory mantle-cell lymphoma. N Engl J Med 2013;369:507–16.

104. Wang M, Rule S, Zinzani PL, et al. Acalabrutinib in relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma (ACE-LY-004): a single-arm, multicentre, phase 2 trial. Lancet 2018;391:659–67.

105. Goy A, Sinha R, Williams ME, et al. Single-agent lenalidomide in patients with mantle-cell lymphoma who relapsed or progressed after or were refractory to bortezomib: phase II MCL-001 (EMERGE) study. J Clin Oncol 2013;31:3688–95.

106. Khouri IF, Lee M-S, Saliba RM, et al. Nonablative allogeneic stem-cell transplantation for advanced/recurrent mantle-cell lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:4407–12.

107. Blum KA, Lozanski G, Byrd JC. Adult Burkitt leukemia and lymphoma. Blood 2004;104:3009–20.

108. Roschewski M, Dunleavy K, Abramson JS, et al. Risk-adapted therapy in adults with Burkitt lymphoma: results of NCI 9177, a multicenter prospective phase II study of DA-EPOCH-R. Blood American Society of Hematology;2017;130(Suppl 1):188.

109. Maramattom L V, Hari PN, Burns LJ, et al. Autologous and allogeneic transplantation for burkitt lymphoma outcomes and changes in utilization: a report from the center for international blood and marrow transplant research. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2013;19:173–9.

110. Zinzani PL, Bendandi M, Visani G, et al. Adult lymphoblastic lymphoma: clinical features and prognostic factors in 53 patients. Leuk Lymphoma 1996;23:577–82.

111. Thomas DA, O’Brien S, Cortes J, et al. Outcome with the hyper-CVAD regimens in lymphoblastic lymphoma. Blood 2004;104:1624–30.

112. Aljurf M, Zaidi SZA. Chemotherapy and hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for adult T-cell lymphoblastic lymphoma: current status and controversies. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant 2005;11:739–54.

113. Sweetenham JW, Santini G, Qian W, et al. High-dose therapy and autologous stem-cell transplantation versus conventional-dose consolidation/maintenance therapy as postremission therapy for adult patients with lymphoblastic lymphoma: results of a randomized trial of the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation and the United Kingdom Lymphoma Group. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:2927–36.

114. Zwaan CM, Kowalczyk J, Schmitt C, et al. Safety and efficacy of nelarabine in children and young adults with relapsed or refractory T-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukaemia or T-lineage lymphoblastic lymphoma: results of a phase 4 study. Br J Haematol 2017;179:284–93.

Abstract

- Objective: To review the diagnosis and management of aggressive B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL).

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: NHL comprises a wide variety of malignant hematologic disorders with varying clinical and biological features. Aggressive NHLs are characterized by rapid clinical progression without therapy. However, a significant proportion of patients are cured with appropriate combination chemotherapy or combined modality regimens. In contrast, the indolent lymphomas have a relatively good prognosis (median survival of 10 years or longer) but usually are not curable in advanced clinical stages. Overall 5-year survival for aggressive NHLs with current treatment is approximately 50% to 60%, with relapses typically occurring within the first 5 years.

- Conclusion: Treatment strategies for relapsed patients offer some potential for cure; however, clinical trial participation should be encouraged whenever possible to investigate new approaches for improving outcomes in this patient population.

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) comprises a wide variety of malignant hematologic disorders with varying clinical and biological features. The more than 60 separate NHL subtypes can be classified according to cell of origin (B cell versus T cell), anatomical location (eg, orbital, testicular, bone, central nervous system), clinical behavior (indolent versus aggressive), histological features, or cytogenetic abnormalities. Although various NHL classification schemes have been used over the years, the World Health Organization (WHO) classification is now widely accepted as the definitive pathologic classification system for lymphoproliferative disorders, incorporating morphologic, immunohistochemical, flow cytometric, cytogenetic, and molecular features [1]. While the pathologic and molecular subclassification of NHL has become increasingly refined in recent years, from a management standpoint, classification based on clinical behavior remains very useful. This approach separates NHL subtypes into indolent versus aggressive categories. Whereas indolent NHLs may remain clinically insignificant for months to years, aggressive B-cell NHLs generally become life-threatening within weeks to months without treatment.

Epidemiology

Data from cancer registries show a steady, unexplainable increase in the incidence of NHL during the second half of the 20th century; the incidence has subsequently plateaued. There was a significant increase in NHL incidence between 1970 and 1995, which has been attributed in part to the HIV epidemic. More than 72,000 new cases of NHL were diagnosed in the United States in 2017, compared to just over 8000 cases of Hodgkin lymphoma, making NHL the sixth most common cancer in adult men and the fifth most common in adult women [2]. NHL appears to occur more frequently in Western countries than in Asian populations.

Various factors associated with increased risk for B-cell NHL have been identified over the years, including occupational and environmental exposure to certain pesticides and herbicides [3], immunosuppression associated with HIV infection [4], autoimmune disorders [5], iatrogenically induced immune suppression in the post-transplant and other settings [6], family history of NHL [7], and a personal history of a prior cancer, including Hodgkin lymphoma and prior NHL [8]. In terms of infectious agents associated with aggressive B-cell NHLs, Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) has a clear pathogenic role in Burkitt lymphoma, in many cases of post-transplant lymphoproliferative disorders, and in some cases of HIV-related aggressive B-cell lymphoma [9]. Human herpesvirus-8 viral genomes have been found in virtually all cases of primary effusion lymphomas [10]. Epidemiological studies also have linked hepatitis B and C to increased incidences of certain NHL subtypes [11–13], including primary hepatic diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). Similarly, Helicobacter pylori has been associated with gastric DLBCL.

Staging and Workup

A tissue biopsy is essential in the diagnosis and management of NHL. The most significant disadvantage of fine-needle aspiration cytology is the lack of histologic architecture. The optimal specimen is an excisional biopsy; when this cannot be performed, a core needle biopsy, ideally using a 16-gauge or larger caliber needle, is the next best choice.

The baseline tests appropriate for most cases of newly diagnosed aggressive B-cell NHL are listed in Table 1.

Prior to the initiation of treatment, patients should always undergo a thorough cardiac and pulmonary evaluation, especially if the patient will be treated with an anthracycline or mediastinal irradiation. Central nervous system (CNS) evaluation with magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and lumbar puncture is essential if there are neurological signs or symptoms. In addition, certain anatomical sites including the testicles, paranasal sinuses, kidney, adrenal glands, and epidural space have been associated with increased involvement of the CNS and may warrant MRI evaluation and lumbar puncture. Certain NHL subtypes like Burkitt lymphoma, high-grade NHL with translocations of MYC and BCL-2 or BCL-6 (double-hit lymphoma), blastoid mantle cell lymphoma, and lymphoblastic lymphoma have a high risk of CNS involvement, and patients with these subtypes need CNS evaluation.

The Lugano classification is used to stage patients with NHL [14]. This classification is based on the Ann Arbor staging system and uses the distribution and number of tumor sites to stage disease. In general, this staging system in isolation is of limited value in predicting survival after treatment. However, the Ann Arbor stage does have prognostic impact when incorporated into risk scoring systems such as the International Prognostic Index (IPI). In clinical practice, the Ann Arbor stage is useful primarily to determine eligibility for localized therapy approaches. The absence or presence of systemic symptoms such as fevers, drenching night sweats, or weight loss (> 10% of baseline over 6 months or less) is designated by A or B, respectively.

Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma

DLBCL is the most common lymphoid neoplasm in adults, accounting for about 25% of all NHL cases [2]. It is increasingly clear that the diagnostic category of DLBCL is quite heterogeneous in terms of morphology, genetics, and biologic behavior. A number of clinicopathologic subtypes of DLBCL exist, such as T cell/histiocyte–rich large B-cell lymphoma, primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma, intravascular large B-cell lymphoma, DLBCL associated with chronic inflammation, lymphomatoid granulomatosis, and EBV-positive large B-cell lymphoma, among others. Gene expression profiling (GEP) can distinguish 2 cell of origin DLBCL subtypes: the germinal center B-cell (GCB) and activated B-cell (ABC) subtypes [15].

DLBCL may be primary (de novo) or may arise through the transformation of many different types of low-grade B-cell lymphomas. This latter scenario is referred to as histologic transformation or transformed lymphoma. In some cases, patients may have a previously diagnosed low-grade B-cell NHL; in other cases, both low-grade and aggressive B-cell NHL may be diagnosed concurrently. The presence of elements of both low-grade and aggressive B-cell NHL in the same biopsy specimen is sometimes referred to as a composite lymphoma.

In the United States, incidence varies by ethnicity, with DLBCL being more common in Caucasians than other races [16]. There is a slight male predominance (55%), median age at diagnosis is 65 years [16,17] and the incidence increases with age.

Presentation, Pathology, and Prognostic Factors

The most common presentation of patients with DLBCL is rapidly enlarging lymphadenopathy, usually in the neck or abdomen. Extranodal/extramedullary presentation is seen in approximately 40% of cases, with the gastrointestinal (GI) tract being the most common site. However, extranodal DLBCL can arise in virtually any tissue [18]. Nodal DLBCL presents with symptoms related to the sites of involvement (eg, shortness of breath or chest pain with mediastinal lymphadenopathy), while extranodal DLBCL typically presents with symptoms secondary to dysfunction at the site of origin. Up to one third of patients present with constitutional symptoms (B symptoms) and more than 50% have elevated serum lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) at diagnosis [19].

Approximately 40% of patients present with stage I/II disease. Of these, only a subset present with stage I, or truly localized disease (defined as that which can be contained within 1 irradiation field). About 60% of patients present with advanced (stage III–IV) disease [20]. The bone marrow is involved in about 15% to 30% of cases. DLBCL involvement of the bone marrow is associated with a less favorable prognosis. Patients with DLBCL elsewhere may have low-grade NHL involvement of the bone marrow. Referred to as discordant bone marrow involvement [21], this feature does not carry the same poor prognosis associated with transformed disease [22] or DLBCL involvement of the bone marrow [23].

DLBCL is defined as a neoplasm of large B-lymphoid cells with a diffuse growth pattern. The proliferative fraction of cells, as determined by Ki-67 staining, is usually greater than 40%, and may even exceed 90%. Lymph nodes usually demonstrate complete effacement of the normal architecture by sheets of atypical lymphoid cells. Tumor cells in DLBCL generally express pan B-cell antigens (CD19, CD20, CD22, CD79a, Pax-5) as well as CD45 and surface immunoglobulin. Between 20% and 37% of DLBCL cases express the BCL-2 protein [24], and about 70% express the BCL-6 protein [25]. C-MYC protein expression is seen in a higher percentage (~ 30%–50%) of cases of DLBCL [26].

Many factors are associated with outcome in DLBCL. The IPI score was developed in the pre-rituximab era and is a robust prognostic tool. This simple tool uses 5 easily obtained clinical factors (age > 60 years, impaired performance status, elevated LDH, > 1 extranodal site of disease, and stage III/IV disease). By summing these factors, 4 groups with distinct 5-year overall survival (OS) rates ranging from 26% to 73% were identified (Table 2).