User login

Hand Hygiene Intervention in Japan

Healthcare‐associated infections are a major cause of illness and death in hospitalized patients, and preventing healthcare‐associated infection is a global challenge.[1] Worldwide, the prevalence of healthcare‐associated infections in developed and undeveloped countries ranges from 5.1% to 11.6% and 5.7% to 19.1%, respectively.[2] In the United States, roughly 2 million such infections occur annually, resulting in approximately 99,000 deaths[3] and estimated annual direct medical costs between $28.4 and $33.8 billion.[4] In Japan, nearly 9% of patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) develop an infection during hospitalization,[5] and 5% of all patients hospitalized become infected with methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus.[6] The management of healthcare‐associated infections in Japan accounts for up to 5% of total annual healthcare costs, with an estimated $6.8 billion estimated to be potentially preventable.[7] In addition, healthcare‐associated infections are associated with increased length of stay in the hospital. Studies estimate surgical site infections extend length of stay by 9.7 days,[8] and bloodstream infections increase length of stay by 10 days.[9]

Improving hand hygiene practice for healthcare workers is considered a core strategy to decrease the incidence of healthcare‐associated infection.[6, 10] Specifically, the use of alcohol‐based hand rub is strongly recommended in acute care hospitals by both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[11, 12] Improving hand hygiene adherence may reduce healthcare‐associated infection by 9% to 50%,[13, 14] and multiple studies have reported that greater use of alcohol‐based hand rubs results in significant reductions in healthcare‐associated infections.[14, 15]

Due to the difficulty in improving hand hygiene in various settings across the world, the WHO strategy for improving hand hygiene has been adopted and implemented by several studies in varying locations, such as Costa Rica, Italy, Mali, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia.[16] Implementations of these multimodal strategies, following WHObased guidelines, have been shown to increase the level of hand hygiene adherence among healthcare workers and reduce infections at these locations.[14, 17, 18] This study expands upon that work by extending the same implementation strategy to assess the effectiveness of the introduction of alcohol‐based hand rub on hand hygiene practice at multiple hospitals in Japan.

In a previous article[19] we reported results from an observational study assessing healthcare worker hand hygiene adherence before touching the patient in 4 geographically diverse hospitals in Japan. The study reported that hand hygiene adherence in Japanese hospitals was lower than reported mean values from other international studies, and that greater adherence to hand hygiene should be encouraged. In this article, we present the results of a multimodal intervention intended to improve levels of healthcare worker hand hygiene in 3 of these hospitals.

METHODS

Participating Institutions

Three of the 4 hospitals participating in the prior observational study chose to participate in this intervention. Evaluation of hand hygiene practice was performed in at least 3 wards of each hospital including an inpatient surgical ward, an inpatient medicine ward, an ICU, or an emergency ward.

Table 1 lists the characteristics of the participating hospitals. Hospital A is a university‐affiliated, tertiary care medical center with 312 beds in East Japan. Although the hospital did not have an infection prevention unit or designated infection control nurses during the preintervention periods, the hospital hired a designated infection prevention nurse and established a department of infection prevention before this intervention in April 2012. Hospital B is a community‐based, tertiary care medical center with 428 beds, located in Midwest Japan. Although the facility had no infection control nurses at the outset of the study, a physician certified by the American Board of Internal Medicine and Infectious Diseases provided educational sessions of hand hygiene. Hospital B hired a designated infection prevention nurse and established a department of infection prevention in April 2012. Hospital C, located in Northern Japan, is a community‐based, tertiary care medical center with 562 beds. The department of infection prevention was established in 2010 and has 1 full‐time and 2 part‐time infection prevention nurses.

| Hospital A | Hospital B | Hospital C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preintervention | Postintervention | Preintervention | Postintervention | Preintervention | Postintervention | |

| ||||||

| Hospital characteristics | ||||||

| Location | East Japan | Midwest Japan | Northern Japan | |||

| Hospital type | University affiliated | Community based | Community based | |||

| Level of care | Tertiary care | Tertiary care | Tertiary care | |||

| Residency program | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| No. of beds | 250 | 312 | 428 | 428 | 550 | 562 |

| No. of employees | 398 | 475 | 1,035 | 1,263 | 1,500 | 1,568 |

| No. of physicians | 73 | 91 | 179 | 188 | 207 | 217 |

| No. of nurses | 172 | 210 | 410 | 540 | 616 | 800 |

| Infection control practice | ||||||

| Establishment of infection prevention units (year) | N/A | Yes (2012) | N/A | Yes (2012) | Yes (2010) | Yes |

| Employment of certified nurses in infection control (FTE) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 3 (1.5) | 3 (1.5) |

| Employment of ABIM‐IDcertified physician | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

Role of the Funding Source

This study was unfunded. The prize for the contest was provided by an American collaborator (S.S.) who was not affiliated with any of the participating hospitals.

Intervention

In the prior preintervention study, hand hygiene adherence rates of healthcare workers were evaluated between July 2011 and November 2011.[19] To improve hand hygiene adherence in these facilities, we initiated a multimodal intervention based on WHO recommendations and the findings from the prior study. Each facility was provided the same guidance on how to improve hand hygiene adherence (Table 2) and encouraged to tailor the intervention to their local setting. As an added incentive, we initiated a contest, where the facility obtaining the highest hand hygiene adherence postintervention would win a trophy and 500,000 Japanese yen (approximately $5000 US dollars). The recommended strategies consisted of 15 components (Table 2): infrastructure (3 components), training and education (2 components), evaluation and feedback (5 components), reminder in the workplace (1 component), and institution safety climate (4 components). Of note, the participating institutions had already implemented a varying number of the intervention components prior to the start of the intervention. Each facility conducted a 6‐month intervention to improve hand hygiene adherence; however, the actual timing of interventions varied slightly by institution. Hospitals A and C conducted an intervention from October 2012 through March 2013, whereas hospital B's intervention was from April 2012 to September 2012. Details of the multimodal intervention performed at each participating hospital are shown in Table 3.

| Intervention Components | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Infrastructure (3 components) | |

| Hand‐washing faucets for each room | At least 1 faucet and sink for each room was available. |

| Placement of alcohol hand rub at patient's room entrance | Alcohol hand rub was placed at all patient room entrances. |

| Portable alcohol hand rub distributed for each healthcare worker | Personal, portable alcohol hand rub dispensers were provided for healthcare workers who contact patients. |

| 2. Training/education (2 components) | |

| Educational resources | At least 1 physician or 1 nurse who provides educational sessions regarding hand hygiene practice was available. |

| Periodic seminars and lectures regarding hand hygiene education | Hospital‐wide hand hygiene seminar or educational activities were held during the intervention period. |

| 3. Evaluation and feedback (5 components) | |

| Evaluation of hand hygiene practice by direct observation | Hospitals utilize direct observation for healthcare worker's hand hygiene practice. |

| Evaluation of hand hygiene practice by monitoring the amount of alcohol hand rub consumption | Hospitals utilize the amount of alcohol hand rub consumption as a parameter for healthcare worker's hand hygiene practice. |

| Hand hygiene rate feedback at infection control committee | Hand hygiene adherence rate was reported and discussed at hospital infection control committee. |

| Hand hygiene rate feedback to the designated wards/units | Hand hygiene adherence rate was reported and discussed with healthcare workers at the designated wards/units where hand hygiene observation was performed. |

| Granting the award of top‐rated person of hand hygiene | Hospitals established the system to assess individual healthcare worker's hand hygiene adherence rate. |

| 4. Reminder in the workplace (1 components) | |

| Poster notification | Poster notification for hand hygiene practice was performed in the intervention period. |

| 5. Institutional safety climate (4 components) | |

| Commitment of hospital president or hospital executives | Hospital executives including the president agreed on the importance of hand hygiene practice and declared to healthcare workers to enhance hand hygiene practice during the intervention period. |

| Commitment of nurse managers and physician leaders | Commitment of improving hand hygiene practice by representative healthcare workers at the designated wards/units (eg, meeting by nurse manager or physician leaders at the designated wards/units and collaborative work with infection prevention services). |

| Meeting at the designated wards/units | A ward/unit‐level meeting or voluntary session for hands‐on hand hygiene practice by healthcare workers at the designated wards/units. |

| Identifying champions at the designated wards/units | An individual healthcare worker who contributed to improving hand hygiene practice was appointed. |

| Hospital A | Hospital Ba | Hospital C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Intervention period | October 2012March 2013 | April 2012September 2012 | October 2012March 2013 | |||

| Evaluation of hand hygiene in the postintervention period | May 2013July 2013 | October 2012 | June 2013 | |||

| Suggested intervention components | Preintervention | Postintervention | Preintervention | Postintervention | Preintervention | Postintervention |

| No. of implemented components | 2/15 | 10/15 | 9/15 | 10/15 | 6/15 | 8/15 |

| Infrastructure (3 components) | ||||||

| Hand‐washing faucets for each room | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Placement of alcohol hand rubs at patient's room entrance | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Portable alcohol hand rub distributed for each healthcare worker | No | Yesb | No | Yesb | No | No |

| Training/education (2 components) | ||||||

| Educational resources | No | Yesb | Yes | Yesb | Yes | Yes |

| Periodic seminars and lectures regarding hand hygiene education | No | Yesb | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Evaluation and feedback (5 components) | ||||||

| Evaluation of hand hygiene practice by direct observation | No | Yesb | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Evaluation of hand hygiene practice by the amount of alcohol hand rub consumption | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hand hygiene rate feedback at infection control committee | No | Yesb | Yes | Yes | No | Yesb |

| Hand hygiene rate feedback to designated departments | No | Yesb | Yes | Yes | No | Yesb |

| Granting the award of top‐rated person | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Reminders in the workplace (1 component) | ||||||

| Poster notification | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5. Institutional safety climate (4 components) | ||||||

| Commitment of hospital president or hospital executives | No | Yesb | No | No | No | No |

| Commitment of nurse managers and physicians leaders | No | Yesb | No | No | No | No |

| Meeting regarding hand hygiene practice by the designated wards/units | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Identifying champions at the designated wards/units | No | No | No | No | No | No |

Observation of Hand Hygiene Practice

The same methods for hand hygiene observation used for the preintervention study was used for postintervention assessment. Ten distinct units across the 3 participating hospitals were evaluated for healthcare worker hand hygiene prior to patient contact. Three to 4 units were observed at each facility. One of the study authors (T.S.), a Japanese board‐certified infection control nurse, conducted all of the hand hygiene observations for both the preintervention and postintervention studies. Intraobserver variation was minimized by providing the same training outlined in the previous study.[19] Appropriate hand hygiene was defined as the use of soap and water or alcohol‐based hand rub before patient contact, which corresponds to the first moment of the WHO's 5 moments of hand hygiene.[11]

Hand hygiene practice prior to patient contact for each individual provider‐patient encounter was observed and recorded using the hand hygiene observation form adapted from a previous study by Saint et al.[6, 20] Identical to the preintervention study,[19] the form captured the following information: unit in which observations were performed, time of initiation and completion of observations, healthcare worker subgroup (physician or nurse), and the type of hand hygiene before patient contact (ie, hand washing with soap and water, use of alcohol‐based hand rub, or no hand hygiene). Unit physicians and nurses were informed that their clinical practices were going to be observed, but were not informed of the purpose of the observations (eg, hand hygiene adherence). To avoid interfering with clinical care delivery, the observer was given strict instructions to maintain a certain distance from the observed healthcare workers. The observer was instructed to leave immediately if asked for any reason by the unit staff or patients.

Statistical Analysis

Overall hand hygiene adherence rates were calculated and compared between the pre‐ and the postintervention periods. Comparison of hand hygiene adherence by healthcare worker subgroup and by hospital unit between the pre‐ and postintervention periods was also performed. Hand hygiene adherence rates were compared using JMP 9.0 and SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Comparison of hand hygiene adherence rates by observational periods was calculated by Pearson [2] tests, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using binomial distribution. Pearson correlations were used to determine the relationship of hand hygiene between physicians and nurses in the same unit. Two‐tailed P value0.05 was considered statistically significant. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethics committees at the participating hospitals.

RESULTS

Data were collected from May 2013 to July 2013 in hospital A, in October 2012 in hospital B, and June 2013 in hospital C to ensure data were collected after the 6‐month intervention at each site. A total of 2982 observations of hand hygiene were performed in 10 distinct units across the 3 participating hospitals during the postintervention periods. Hand hygiene observations were performed during the day Monday through Friday between 8:30 am and 7:30 pm, with the majority occurring prior to 1:00 pm.

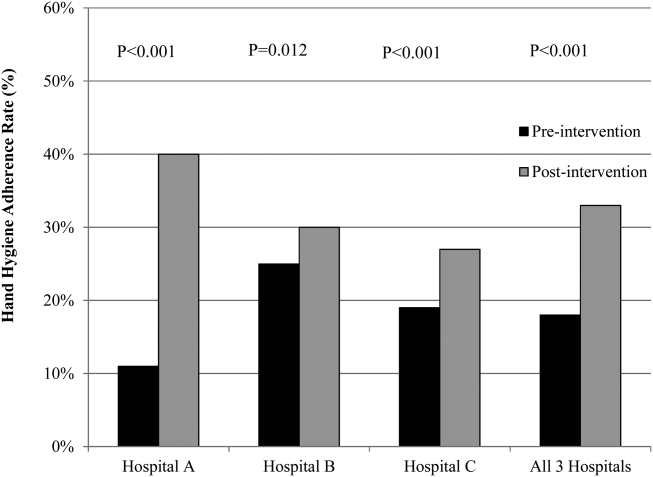

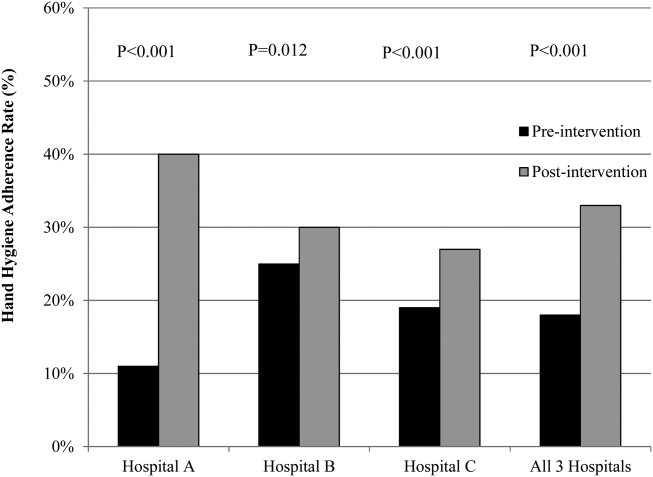

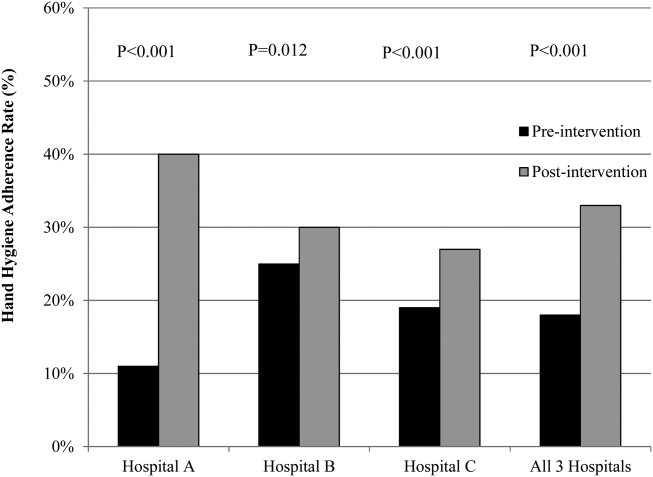

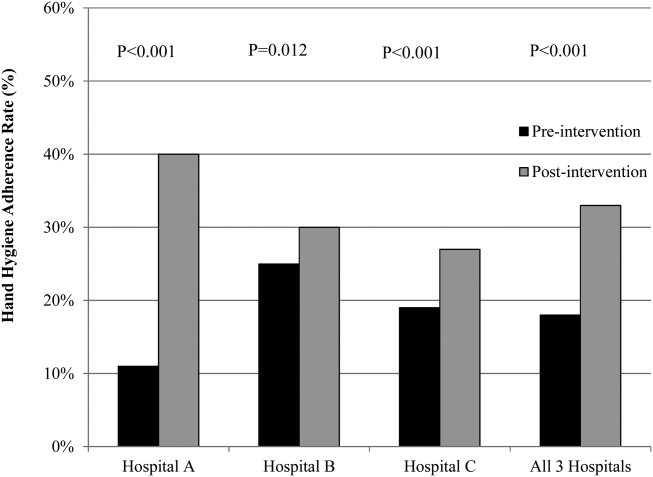

The overall postintervention hand hygiene adherence rate (in all 3 hospitals) was significantly higher at 32.7% (974/2982) adherence compared to 18.0% (482/2679) adherence in the preintervention period (P<0.001). An increased hand hygiene adherence rate in each participating hospital in the postintervention period was observed (Figure 1). Similar trends of higher overall hand hygiene adherence rates for both nurses and physicians in the postintervention period were seen. Use of alcohol‐based hand rub among those with appropriate hand hygiene was significantly higher, with 90.0% (880/974) using hand rub in the postintervention period versus 67.0% (322/482) in the preintervention period (P<0.001). Comparison of overall hand hygiene adherence rates by unit type and healthcare worker subgroup between the pre‐ and postintervention periods are shown in Table 4. Detailed comparisons of hand hygiene adherence rates for each hospital are available in the supplementary appendix. Although a significant improvement of hand hygiene practice was observed in the majority of participating units (6/10), there was a significant decline in hand hygiene practice in 2 units for nurses and 1 unit for physicians. Hand hygiene adherence rates by healthcare worker subgroups (both physicians and nurses) were significantly higher in the postintervention period than those in the preintervention period. Trends toward higher hand hygiene adherence rate of nurses in the postintervention period were observed (34.8% adherence for nurses compared to 30.4% adherence for physicians); the difference between nurses and physicians were not statistically significant (P=0.07).

| Ward/Unit | Healthcare Worker Subgroup | Preintervention Period | Postintervention Period | Improvement After Intervention (%) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Observations | Hand hygiene Adherence (%) | No. of Observations | Hand Hygiene Adherence (%) | ||||

| |||||||

| All 3 hospitals | |||||||

| Surgery | Nurse | 455 | 20 | 480 | 40 | 20 | <0.001 |

| Physician | 424 | 18 | 448 | 43 | 25 | <0.001 | |

| All | 879 | 19 | 928 | 41 | 22 | <0.001 | |

| Medicine | Nurse | 455 | 23 | 508 | 39 | 16 | <0.001 |

| Physician | 435 | 15 | 452 | 33 | 18 | <0.001 | |

| All | 890 | 20 | 960 | 36 | 16 | <0.001 | |

| ICU | Nurse | 305 | 21 | 379 | 25 | 4 | 0.17 |

| Physician | 203 | 9 | 268 | 28 | 19 | <0.001 | |

| All | 508 | 16 | 647 | 26 | 10 | <0.001 | |

| ED | Nurse | 170 | 16 | 173 | 27 | 11 | 0.01 |

| Physician | 232 | 14 | 274 | 9 | ‐5 | 0.07 | |

| All | 402 | 15 | 447 | 16 | 1 | 0.64 | |

| All units | Nurse | 1385 | 21 | 1540 | 35 | 14 | <0.001 |

| Physician | 1294 | 15 | 1442 | 30 | 15 | <0.001 | |

| All | 2679 | 18 | 2982 | 33 | 15 | <0.001 | |

Hospital A achieved the highest postintervention adherence rates (39.9% adherence postintervention), as well as the greatest absolute improvement in hand hygiene (increase of 29.0%). There were significant improvements in 3 of the 4 participating units in hospital A, with the emergency department showing improvements only in the nurse subgroup. In hospital B, total hand hygiene adherence increased from 24.7% to 30.0% (P=0.01); however, this increase was mainly due to increase in hand hygiene adherence rates of nurses. There were significant increases in hand hygiene adherence rates for nurses in the medicine (+11%, P=0.04) and surgery wards (+14%, P=0.01), with nonsignificant increases for physicians (+10% medicine, P=0.07;+2% surgery, P=0.78). However, in the emergency department, nurses showed no significant improvement, and physicians had a significant decrease in adherence (15.7% preintervention vs 7.4% postintervention; P=0.02). In hospital C, total hand hygiene practice rates were significantly improved (from 18.9% to 26.5%; P<0.001); however, this was driven by improvements only in the surgical ward (14.6% preintervention to 42.3% postintervention; P<0.001). The rates for nurses declined significantly in both the medicine and ICU wards, leading to no observed improvements on those wards.

DISCUSSION

Our multicenter intervention study in Japan included observations from almost 3000 encounters between clinicians and patients. Before the intervention, the overall rate of hand hygiene adherence was 18%. After the multimodal intervention, the absolute increase in healthcare worker hand hygiene adherence was 15%. Although there was overall improvement, the adherence rates varied by hospital, with hospital A increasing by 29% and hospital B and C only attaining increases of 5% and 7%, respectively.

Despite the importance of hand hygiene of healthcare workers, it is challenging to increase hand hygiene adherence because it requires behavioral modification. Moreover, it remains uncertain what factors will affect healthcare worker behavior. We implemented pragmatic strategies to evaluate the efficacy of hand hygiene multimodal interventions based on internationally recognized WHO hand hygiene adherence strategies[11] and an institutional‐level contest with financial incentives. The findings in the current study help us understand not only how a multimodal intervention importantly improves hand hygiene adherence, but also what factors potentially make healthcare workers modify their behaviors.

In this study, we evaluated whether an institutional‐level contest with financial incentives contributed to improved hand hygiene adherence of healthcare workers. This study demonstrated improvement of hand hygiene practice after implementation of a multimodal hand hygiene intervention combined with an institutional‐level contest with financial incentives. The contest might have had a modest effect to help motivate the participating hospitals to improve their hand hygiene adherence rate. This is consistent with a previous study that demonstrated financial incentives were associated with modifying healthcare workers' hand hygiene practice.[21] However, we did not strictly standardize how the contest information was distributed in each participating institution and the objective assessment for changes in motivation by the contest was lacking in this study. Thus, changes in motivation by the contest with financial incentives likely varied by each participating institution. Further studies are needed to assess if this type of approach is worth pursuing.

We observed several noteworthy associations between the intervention components that were implemented at each facility and their improvement in hand hygiene adherence. Among the participating hospitals, hospital A was most successful with improving hand hygiene adherence, although all participating hospitals achieved a similar number of the 15 recommended intervention components during the intervention (8 to 10 per hospital). Interestingly, hospital A initiated the most new components during the intervention period (8 new components for a total of 10 out of 15), whereas hospital B and hospital C initiated only 1 or 2 new components during the intervention period. Hospital A also successfully involved hospital executives, and elicited the commitment of a nurse manager and physician leader. Consistent with a previous study,[22] we believe that involvement of hospital executives appears to be important to increase overall hand hygiene rate among healthcare workers.

In contrast, hospitals B and C did not involve senior executives or identify nurse or physician champions for all participating units. Based on the results in this study, we believe that the involvement of hospital executives is likely a key for the penetration of hospital‐wide hand hygiene culture among healthcare workers.

Although this study was unable to determine which components are precisely associated with improving hand hygiene adherence, the findings suggest initiating multiple intervention components at the same time may provide more motivation for change than initiating only 1 or 2 components at a time. It is also possible that certain intervention components were more beneficial than others. For example, hospital A, which achieved the most success, was the only hospital to obtain leadership support. Other studies have demonstrated that the presence of leadership appeared to play a key role in improving hand hygiene adherence.[23, 24] Moreover, a recent Japanese nationwide survey demonstrated higher safety centeredness was associated with regular use of standard infection prevention practice.[25] Consistent with a previous study, improving hand hygiene adherence cannot be simply achieved by improving infrastructure (eg, introduction of portable alcohol‐based hand rub) alone, but it depends on altering healthcare worker behavior.[26]

This study has several limitations. Because participating hospitals could tailor the specific interventions chosen for their facility, the improvement in hand hygiene adherence was likely multifactorial. We are unable in the existing study to determine a direct causal relationship between any of the individual intervention components and hand hygiene adherence. We are also unable to determine whether the improvements seen in hospital A were due to participation in the contest or due to the specific intervention components that were implemented. However, WHO hand hygiene guidelines point out that recognition of the importance of hand hygiene varies in different regions and countries, and the goal for hand hygiene interventions is to establish a culture of hand hygiene practice through pragmatic intervention strategies, frequent evaluation, and feedback to healthcare workers.[27] Thus, we prioritized pragmatic strategies to include in our intervention to promote hand hygiene adherence. Another limitation was the date of implementation of the multimodal intervention was slightly different at each facility. It was challenging to implement the intervention simultaneously across institutions due to competing priorities at each facility. Although the primary goal of hand hygiene is to reduce the burden of healthcare‐associated infection, we were unable to measure infection rates at the participating facilities. It is possible the presence of an external observer had an impact on the healthcare workers' behavior.[28] However, the healthcare workers were not informed as to what the observer was monitoring to minimize this potential effect. Lastly, the findings in this study provide immediate intervention effects but further study will be required to determine if these effects are sustainable.

Altering healthcare worker behavior is likely the key element to improve hand hygiene adherence, and behavioral modification may be achieved with the support of leadership at the unit and facility level. However, even though we found significant improvements in healthcare worker hand hygiene adherence after the intervention, the adherence rates are still relatively low compared to reported adherence rates from other countries,[29] suggesting further intervention is needed in this setting to optimize and hygiene practice. Because hand hygiene practice is a crucial strategy to prevent healthcare‐associated infections, every effort should be made to enhance the hand hygiene practice of healthcare workers.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the International Ann Arbor Safety Collaborative (

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

- . Infection control—a problem for patient safety. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(7):651–656.

- World Health Organization. The burden of health care‐associated infection worldwide: a summary. Available at: http://www.who.int/gpsc/country_work/summary_20100430_en.pdf. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- , , , et al. Estimating health care‐associated infections and deaths in U.S. hospitals, 2002. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(2):160–166.

- . The direct medical costs of healthcare‐associated infections in U.S. hospitals and the benefits of prevention. Atlanta, GA: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2009. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/HAI/pdfs/hai/Scott_CostPaper.pdf. Accessed April 20, 2015.

- , , . Epidemiological approach to nosocomial infection surveillance data: the Japanese Nosocomial Infection Surveillance System. Environ Health Prev Med. 2008;13(1):30–35.

- , , , et al. Improving healthcare worker hand hygiene adherence before patient contact: a before‐and‐after five‐unit multimodal intervention in Tuscany. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(6):429–433.

- . Economical efficiency of infection control. Antibiot Chemother (Northfield). 2004;20:635–638.

- , , , , , . Surgical site infection: incidence and impact on hospital utilization and treatment costs. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37(5):387–397.

- , , , , , . Hospital‐acquired, laboratory‐confirmed bloodstream infections: linking national surveillance data to clinical and financial hospital data to estimate increased length of stay and healthcare costs. J Hosp Infect. 2010;75(3):158–162.

- . APIC guideline for handwashing and hand antisepsis in health care settings. Am J Infect Control. 1995;23(4):251–269.

- World Health Organization. WHO Guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care. Clean care is safer care: first global patient safety challenge. Geneva, Switzerland; 2009. Available at: http://www.who.int/gpsc/en/index.html. Accessed October 6, 2014.

- , ; Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee, HICPAC SHEA APIC IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. Guideline for hand hygiene in health‐care settings. Recommendations of the Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee and the HICPAC/SHEA/APIC/IDSA Hand Hygiene Task Force. Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America/Association for Professionals in Infection Control/Infectious Diseases Society of America. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2002;51(RR‐16):1–45.

- National Patient Safety Agency. The economic case: implementing near‐patient alcohol hand rum in your trust. London, United Kingdom; 2004. Available at: http://www.npsa.nhs.uk/cleanyourhands/resource‐area/evidence‐base/?EntryId34=58433. Accessed October 9, 2014.

- , , , et al. Effectiveness of a hospital‐wide programme to improve compliance with hand hygiene. Infection Control Programme. Lancet. 2000;356(9238):1307–1312.

- , . Role of hand hygiene in healthcare‐associated infection prevention. J Hosp Infect. 2009;73(4):305–315.

- , , , et al. Global implementation of WHO's multimodal strategy for improvement of hand hygiene: a quasi‐experimental study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(10):843–851.

- , , , et al. Impact of the International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC) multidimensional hand hygiene approach over 13 years in 51 cities of 19 limited‐resource countries from Latin America, Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(4):415–423.

- , , , . Bundling hand hygiene interventions and measurement to decrease health care‐associated infections. Am J Infect Control. 2012;40(4 suppl 1):S18–S27.

- , , , et al. Hand hygiene adherence among health care workers at Japanese hospitals: a multicenter observational study in Japan [published online April 8, 2014]. J Patient Saf. doi: 10.1097/PTS.0000000000000108.

- , , , et al. Marked variability in adherence to hand hygiene: a 5‐unit observational study in Tuscany. Am J Infect Control. 2009;37(4):306–310.

- , , , et al. Sustained improvement in hand hygiene adherence: utilizing shared accountability and financial incentives. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2013;34(11):1129–1136.

- , , , . Status of the implementation of the World Health Organization multimodal hand hygiene strategy in United States of America health care facilities. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(3):224–230.

- , , , et al. The effect of leadership on hand hygiene: assessing hand hygiene adherence prior to patient contact in 2 infectious disease units in Tuscany. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2014;35(3):313–316.

- , , , , , . Impact of a hospital‐wide hand hygiene initiative on healthcare‐associated infections: results of an interrupted time series. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(12):1019–1026.

- , , , , , . Health care‐associated infection prevention in Japan: the role of safety culture. Am J Infect Control. 2014;42(8):888–893.

- , , . Why healthcare workers don't wash their hands: a behavioral explanation. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2006;27(5):484–492.

- World Health Organization. Guide to implementation. A guide to the implementation of the WHO multimodal hand hygiene improvement strategy. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/hq/2009/WHO_IER_PSP_2009.02_eng.pdf. Accessed October 9, 2014.

- , , , et al. Compliance of health care workers with hand hygiene practices: independent advantages of overt and covert observers. PLoS One. 2013;8(1):e53746.

- , , , et al. Systematic review of studies on compliance with hand hygiene guidelines in hospital care. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2010;31(3):283–294.

Healthcare‐associated infections are a major cause of illness and death in hospitalized patients, and preventing healthcare‐associated infection is a global challenge.[1] Worldwide, the prevalence of healthcare‐associated infections in developed and undeveloped countries ranges from 5.1% to 11.6% and 5.7% to 19.1%, respectively.[2] In the United States, roughly 2 million such infections occur annually, resulting in approximately 99,000 deaths[3] and estimated annual direct medical costs between $28.4 and $33.8 billion.[4] In Japan, nearly 9% of patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) develop an infection during hospitalization,[5] and 5% of all patients hospitalized become infected with methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus.[6] The management of healthcare‐associated infections in Japan accounts for up to 5% of total annual healthcare costs, with an estimated $6.8 billion estimated to be potentially preventable.[7] In addition, healthcare‐associated infections are associated with increased length of stay in the hospital. Studies estimate surgical site infections extend length of stay by 9.7 days,[8] and bloodstream infections increase length of stay by 10 days.[9]

Improving hand hygiene practice for healthcare workers is considered a core strategy to decrease the incidence of healthcare‐associated infection.[6, 10] Specifically, the use of alcohol‐based hand rub is strongly recommended in acute care hospitals by both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[11, 12] Improving hand hygiene adherence may reduce healthcare‐associated infection by 9% to 50%,[13, 14] and multiple studies have reported that greater use of alcohol‐based hand rubs results in significant reductions in healthcare‐associated infections.[14, 15]

Due to the difficulty in improving hand hygiene in various settings across the world, the WHO strategy for improving hand hygiene has been adopted and implemented by several studies in varying locations, such as Costa Rica, Italy, Mali, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia.[16] Implementations of these multimodal strategies, following WHObased guidelines, have been shown to increase the level of hand hygiene adherence among healthcare workers and reduce infections at these locations.[14, 17, 18] This study expands upon that work by extending the same implementation strategy to assess the effectiveness of the introduction of alcohol‐based hand rub on hand hygiene practice at multiple hospitals in Japan.

In a previous article[19] we reported results from an observational study assessing healthcare worker hand hygiene adherence before touching the patient in 4 geographically diverse hospitals in Japan. The study reported that hand hygiene adherence in Japanese hospitals was lower than reported mean values from other international studies, and that greater adherence to hand hygiene should be encouraged. In this article, we present the results of a multimodal intervention intended to improve levels of healthcare worker hand hygiene in 3 of these hospitals.

METHODS

Participating Institutions

Three of the 4 hospitals participating in the prior observational study chose to participate in this intervention. Evaluation of hand hygiene practice was performed in at least 3 wards of each hospital including an inpatient surgical ward, an inpatient medicine ward, an ICU, or an emergency ward.

Table 1 lists the characteristics of the participating hospitals. Hospital A is a university‐affiliated, tertiary care medical center with 312 beds in East Japan. Although the hospital did not have an infection prevention unit or designated infection control nurses during the preintervention periods, the hospital hired a designated infection prevention nurse and established a department of infection prevention before this intervention in April 2012. Hospital B is a community‐based, tertiary care medical center with 428 beds, located in Midwest Japan. Although the facility had no infection control nurses at the outset of the study, a physician certified by the American Board of Internal Medicine and Infectious Diseases provided educational sessions of hand hygiene. Hospital B hired a designated infection prevention nurse and established a department of infection prevention in April 2012. Hospital C, located in Northern Japan, is a community‐based, tertiary care medical center with 562 beds. The department of infection prevention was established in 2010 and has 1 full‐time and 2 part‐time infection prevention nurses.

| Hospital A | Hospital B | Hospital C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preintervention | Postintervention | Preintervention | Postintervention | Preintervention | Postintervention | |

| ||||||

| Hospital characteristics | ||||||

| Location | East Japan | Midwest Japan | Northern Japan | |||

| Hospital type | University affiliated | Community based | Community based | |||

| Level of care | Tertiary care | Tertiary care | Tertiary care | |||

| Residency program | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| No. of beds | 250 | 312 | 428 | 428 | 550 | 562 |

| No. of employees | 398 | 475 | 1,035 | 1,263 | 1,500 | 1,568 |

| No. of physicians | 73 | 91 | 179 | 188 | 207 | 217 |

| No. of nurses | 172 | 210 | 410 | 540 | 616 | 800 |

| Infection control practice | ||||||

| Establishment of infection prevention units (year) | N/A | Yes (2012) | N/A | Yes (2012) | Yes (2010) | Yes |

| Employment of certified nurses in infection control (FTE) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 3 (1.5) | 3 (1.5) |

| Employment of ABIM‐IDcertified physician | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

Role of the Funding Source

This study was unfunded. The prize for the contest was provided by an American collaborator (S.S.) who was not affiliated with any of the participating hospitals.

Intervention

In the prior preintervention study, hand hygiene adherence rates of healthcare workers were evaluated between July 2011 and November 2011.[19] To improve hand hygiene adherence in these facilities, we initiated a multimodal intervention based on WHO recommendations and the findings from the prior study. Each facility was provided the same guidance on how to improve hand hygiene adherence (Table 2) and encouraged to tailor the intervention to their local setting. As an added incentive, we initiated a contest, where the facility obtaining the highest hand hygiene adherence postintervention would win a trophy and 500,000 Japanese yen (approximately $5000 US dollars). The recommended strategies consisted of 15 components (Table 2): infrastructure (3 components), training and education (2 components), evaluation and feedback (5 components), reminder in the workplace (1 component), and institution safety climate (4 components). Of note, the participating institutions had already implemented a varying number of the intervention components prior to the start of the intervention. Each facility conducted a 6‐month intervention to improve hand hygiene adherence; however, the actual timing of interventions varied slightly by institution. Hospitals A and C conducted an intervention from October 2012 through March 2013, whereas hospital B's intervention was from April 2012 to September 2012. Details of the multimodal intervention performed at each participating hospital are shown in Table 3.

| Intervention Components | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Infrastructure (3 components) | |

| Hand‐washing faucets for each room | At least 1 faucet and sink for each room was available. |

| Placement of alcohol hand rub at patient's room entrance | Alcohol hand rub was placed at all patient room entrances. |

| Portable alcohol hand rub distributed for each healthcare worker | Personal, portable alcohol hand rub dispensers were provided for healthcare workers who contact patients. |

| 2. Training/education (2 components) | |

| Educational resources | At least 1 physician or 1 nurse who provides educational sessions regarding hand hygiene practice was available. |

| Periodic seminars and lectures regarding hand hygiene education | Hospital‐wide hand hygiene seminar or educational activities were held during the intervention period. |

| 3. Evaluation and feedback (5 components) | |

| Evaluation of hand hygiene practice by direct observation | Hospitals utilize direct observation for healthcare worker's hand hygiene practice. |

| Evaluation of hand hygiene practice by monitoring the amount of alcohol hand rub consumption | Hospitals utilize the amount of alcohol hand rub consumption as a parameter for healthcare worker's hand hygiene practice. |

| Hand hygiene rate feedback at infection control committee | Hand hygiene adherence rate was reported and discussed at hospital infection control committee. |

| Hand hygiene rate feedback to the designated wards/units | Hand hygiene adherence rate was reported and discussed with healthcare workers at the designated wards/units where hand hygiene observation was performed. |

| Granting the award of top‐rated person of hand hygiene | Hospitals established the system to assess individual healthcare worker's hand hygiene adherence rate. |

| 4. Reminder in the workplace (1 components) | |

| Poster notification | Poster notification for hand hygiene practice was performed in the intervention period. |

| 5. Institutional safety climate (4 components) | |

| Commitment of hospital president or hospital executives | Hospital executives including the president agreed on the importance of hand hygiene practice and declared to healthcare workers to enhance hand hygiene practice during the intervention period. |

| Commitment of nurse managers and physician leaders | Commitment of improving hand hygiene practice by representative healthcare workers at the designated wards/units (eg, meeting by nurse manager or physician leaders at the designated wards/units and collaborative work with infection prevention services). |

| Meeting at the designated wards/units | A ward/unit‐level meeting or voluntary session for hands‐on hand hygiene practice by healthcare workers at the designated wards/units. |

| Identifying champions at the designated wards/units | An individual healthcare worker who contributed to improving hand hygiene practice was appointed. |

| Hospital A | Hospital Ba | Hospital C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Intervention period | October 2012March 2013 | April 2012September 2012 | October 2012March 2013 | |||

| Evaluation of hand hygiene in the postintervention period | May 2013July 2013 | October 2012 | June 2013 | |||

| Suggested intervention components | Preintervention | Postintervention | Preintervention | Postintervention | Preintervention | Postintervention |

| No. of implemented components | 2/15 | 10/15 | 9/15 | 10/15 | 6/15 | 8/15 |

| Infrastructure (3 components) | ||||||

| Hand‐washing faucets for each room | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Placement of alcohol hand rubs at patient's room entrance | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Portable alcohol hand rub distributed for each healthcare worker | No | Yesb | No | Yesb | No | No |

| Training/education (2 components) | ||||||

| Educational resources | No | Yesb | Yes | Yesb | Yes | Yes |

| Periodic seminars and lectures regarding hand hygiene education | No | Yesb | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Evaluation and feedback (5 components) | ||||||

| Evaluation of hand hygiene practice by direct observation | No | Yesb | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Evaluation of hand hygiene practice by the amount of alcohol hand rub consumption | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hand hygiene rate feedback at infection control committee | No | Yesb | Yes | Yes | No | Yesb |

| Hand hygiene rate feedback to designated departments | No | Yesb | Yes | Yes | No | Yesb |

| Granting the award of top‐rated person | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Reminders in the workplace (1 component) | ||||||

| Poster notification | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5. Institutional safety climate (4 components) | ||||||

| Commitment of hospital president or hospital executives | No | Yesb | No | No | No | No |

| Commitment of nurse managers and physicians leaders | No | Yesb | No | No | No | No |

| Meeting regarding hand hygiene practice by the designated wards/units | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Identifying champions at the designated wards/units | No | No | No | No | No | No |

Observation of Hand Hygiene Practice

The same methods for hand hygiene observation used for the preintervention study was used for postintervention assessment. Ten distinct units across the 3 participating hospitals were evaluated for healthcare worker hand hygiene prior to patient contact. Three to 4 units were observed at each facility. One of the study authors (T.S.), a Japanese board‐certified infection control nurse, conducted all of the hand hygiene observations for both the preintervention and postintervention studies. Intraobserver variation was minimized by providing the same training outlined in the previous study.[19] Appropriate hand hygiene was defined as the use of soap and water or alcohol‐based hand rub before patient contact, which corresponds to the first moment of the WHO's 5 moments of hand hygiene.[11]

Hand hygiene practice prior to patient contact for each individual provider‐patient encounter was observed and recorded using the hand hygiene observation form adapted from a previous study by Saint et al.[6, 20] Identical to the preintervention study,[19] the form captured the following information: unit in which observations were performed, time of initiation and completion of observations, healthcare worker subgroup (physician or nurse), and the type of hand hygiene before patient contact (ie, hand washing with soap and water, use of alcohol‐based hand rub, or no hand hygiene). Unit physicians and nurses were informed that their clinical practices were going to be observed, but were not informed of the purpose of the observations (eg, hand hygiene adherence). To avoid interfering with clinical care delivery, the observer was given strict instructions to maintain a certain distance from the observed healthcare workers. The observer was instructed to leave immediately if asked for any reason by the unit staff or patients.

Statistical Analysis

Overall hand hygiene adherence rates were calculated and compared between the pre‐ and the postintervention periods. Comparison of hand hygiene adherence by healthcare worker subgroup and by hospital unit between the pre‐ and postintervention periods was also performed. Hand hygiene adherence rates were compared using JMP 9.0 and SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Comparison of hand hygiene adherence rates by observational periods was calculated by Pearson [2] tests, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using binomial distribution. Pearson correlations were used to determine the relationship of hand hygiene between physicians and nurses in the same unit. Two‐tailed P value0.05 was considered statistically significant. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethics committees at the participating hospitals.

RESULTS

Data were collected from May 2013 to July 2013 in hospital A, in October 2012 in hospital B, and June 2013 in hospital C to ensure data were collected after the 6‐month intervention at each site. A total of 2982 observations of hand hygiene were performed in 10 distinct units across the 3 participating hospitals during the postintervention periods. Hand hygiene observations were performed during the day Monday through Friday between 8:30 am and 7:30 pm, with the majority occurring prior to 1:00 pm.

The overall postintervention hand hygiene adherence rate (in all 3 hospitals) was significantly higher at 32.7% (974/2982) adherence compared to 18.0% (482/2679) adherence in the preintervention period (P<0.001). An increased hand hygiene adherence rate in each participating hospital in the postintervention period was observed (Figure 1). Similar trends of higher overall hand hygiene adherence rates for both nurses and physicians in the postintervention period were seen. Use of alcohol‐based hand rub among those with appropriate hand hygiene was significantly higher, with 90.0% (880/974) using hand rub in the postintervention period versus 67.0% (322/482) in the preintervention period (P<0.001). Comparison of overall hand hygiene adherence rates by unit type and healthcare worker subgroup between the pre‐ and postintervention periods are shown in Table 4. Detailed comparisons of hand hygiene adherence rates for each hospital are available in the supplementary appendix. Although a significant improvement of hand hygiene practice was observed in the majority of participating units (6/10), there was a significant decline in hand hygiene practice in 2 units for nurses and 1 unit for physicians. Hand hygiene adherence rates by healthcare worker subgroups (both physicians and nurses) were significantly higher in the postintervention period than those in the preintervention period. Trends toward higher hand hygiene adherence rate of nurses in the postintervention period were observed (34.8% adherence for nurses compared to 30.4% adherence for physicians); the difference between nurses and physicians were not statistically significant (P=0.07).

| Ward/Unit | Healthcare Worker Subgroup | Preintervention Period | Postintervention Period | Improvement After Intervention (%) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Observations | Hand hygiene Adherence (%) | No. of Observations | Hand Hygiene Adherence (%) | ||||

| |||||||

| All 3 hospitals | |||||||

| Surgery | Nurse | 455 | 20 | 480 | 40 | 20 | <0.001 |

| Physician | 424 | 18 | 448 | 43 | 25 | <0.001 | |

| All | 879 | 19 | 928 | 41 | 22 | <0.001 | |

| Medicine | Nurse | 455 | 23 | 508 | 39 | 16 | <0.001 |

| Physician | 435 | 15 | 452 | 33 | 18 | <0.001 | |

| All | 890 | 20 | 960 | 36 | 16 | <0.001 | |

| ICU | Nurse | 305 | 21 | 379 | 25 | 4 | 0.17 |

| Physician | 203 | 9 | 268 | 28 | 19 | <0.001 | |

| All | 508 | 16 | 647 | 26 | 10 | <0.001 | |

| ED | Nurse | 170 | 16 | 173 | 27 | 11 | 0.01 |

| Physician | 232 | 14 | 274 | 9 | ‐5 | 0.07 | |

| All | 402 | 15 | 447 | 16 | 1 | 0.64 | |

| All units | Nurse | 1385 | 21 | 1540 | 35 | 14 | <0.001 |

| Physician | 1294 | 15 | 1442 | 30 | 15 | <0.001 | |

| All | 2679 | 18 | 2982 | 33 | 15 | <0.001 | |

Hospital A achieved the highest postintervention adherence rates (39.9% adherence postintervention), as well as the greatest absolute improvement in hand hygiene (increase of 29.0%). There were significant improvements in 3 of the 4 participating units in hospital A, with the emergency department showing improvements only in the nurse subgroup. In hospital B, total hand hygiene adherence increased from 24.7% to 30.0% (P=0.01); however, this increase was mainly due to increase in hand hygiene adherence rates of nurses. There were significant increases in hand hygiene adherence rates for nurses in the medicine (+11%, P=0.04) and surgery wards (+14%, P=0.01), with nonsignificant increases for physicians (+10% medicine, P=0.07;+2% surgery, P=0.78). However, in the emergency department, nurses showed no significant improvement, and physicians had a significant decrease in adherence (15.7% preintervention vs 7.4% postintervention; P=0.02). In hospital C, total hand hygiene practice rates were significantly improved (from 18.9% to 26.5%; P<0.001); however, this was driven by improvements only in the surgical ward (14.6% preintervention to 42.3% postintervention; P<0.001). The rates for nurses declined significantly in both the medicine and ICU wards, leading to no observed improvements on those wards.

DISCUSSION

Our multicenter intervention study in Japan included observations from almost 3000 encounters between clinicians and patients. Before the intervention, the overall rate of hand hygiene adherence was 18%. After the multimodal intervention, the absolute increase in healthcare worker hand hygiene adherence was 15%. Although there was overall improvement, the adherence rates varied by hospital, with hospital A increasing by 29% and hospital B and C only attaining increases of 5% and 7%, respectively.

Despite the importance of hand hygiene of healthcare workers, it is challenging to increase hand hygiene adherence because it requires behavioral modification. Moreover, it remains uncertain what factors will affect healthcare worker behavior. We implemented pragmatic strategies to evaluate the efficacy of hand hygiene multimodal interventions based on internationally recognized WHO hand hygiene adherence strategies[11] and an institutional‐level contest with financial incentives. The findings in the current study help us understand not only how a multimodal intervention importantly improves hand hygiene adherence, but also what factors potentially make healthcare workers modify their behaviors.

In this study, we evaluated whether an institutional‐level contest with financial incentives contributed to improved hand hygiene adherence of healthcare workers. This study demonstrated improvement of hand hygiene practice after implementation of a multimodal hand hygiene intervention combined with an institutional‐level contest with financial incentives. The contest might have had a modest effect to help motivate the participating hospitals to improve their hand hygiene adherence rate. This is consistent with a previous study that demonstrated financial incentives were associated with modifying healthcare workers' hand hygiene practice.[21] However, we did not strictly standardize how the contest information was distributed in each participating institution and the objective assessment for changes in motivation by the contest was lacking in this study. Thus, changes in motivation by the contest with financial incentives likely varied by each participating institution. Further studies are needed to assess if this type of approach is worth pursuing.

We observed several noteworthy associations between the intervention components that were implemented at each facility and their improvement in hand hygiene adherence. Among the participating hospitals, hospital A was most successful with improving hand hygiene adherence, although all participating hospitals achieved a similar number of the 15 recommended intervention components during the intervention (8 to 10 per hospital). Interestingly, hospital A initiated the most new components during the intervention period (8 new components for a total of 10 out of 15), whereas hospital B and hospital C initiated only 1 or 2 new components during the intervention period. Hospital A also successfully involved hospital executives, and elicited the commitment of a nurse manager and physician leader. Consistent with a previous study,[22] we believe that involvement of hospital executives appears to be important to increase overall hand hygiene rate among healthcare workers.

In contrast, hospitals B and C did not involve senior executives or identify nurse or physician champions for all participating units. Based on the results in this study, we believe that the involvement of hospital executives is likely a key for the penetration of hospital‐wide hand hygiene culture among healthcare workers.

Although this study was unable to determine which components are precisely associated with improving hand hygiene adherence, the findings suggest initiating multiple intervention components at the same time may provide more motivation for change than initiating only 1 or 2 components at a time. It is also possible that certain intervention components were more beneficial than others. For example, hospital A, which achieved the most success, was the only hospital to obtain leadership support. Other studies have demonstrated that the presence of leadership appeared to play a key role in improving hand hygiene adherence.[23, 24] Moreover, a recent Japanese nationwide survey demonstrated higher safety centeredness was associated with regular use of standard infection prevention practice.[25] Consistent with a previous study, improving hand hygiene adherence cannot be simply achieved by improving infrastructure (eg, introduction of portable alcohol‐based hand rub) alone, but it depends on altering healthcare worker behavior.[26]

This study has several limitations. Because participating hospitals could tailor the specific interventions chosen for their facility, the improvement in hand hygiene adherence was likely multifactorial. We are unable in the existing study to determine a direct causal relationship between any of the individual intervention components and hand hygiene adherence. We are also unable to determine whether the improvements seen in hospital A were due to participation in the contest or due to the specific intervention components that were implemented. However, WHO hand hygiene guidelines point out that recognition of the importance of hand hygiene varies in different regions and countries, and the goal for hand hygiene interventions is to establish a culture of hand hygiene practice through pragmatic intervention strategies, frequent evaluation, and feedback to healthcare workers.[27] Thus, we prioritized pragmatic strategies to include in our intervention to promote hand hygiene adherence. Another limitation was the date of implementation of the multimodal intervention was slightly different at each facility. It was challenging to implement the intervention simultaneously across institutions due to competing priorities at each facility. Although the primary goal of hand hygiene is to reduce the burden of healthcare‐associated infection, we were unable to measure infection rates at the participating facilities. It is possible the presence of an external observer had an impact on the healthcare workers' behavior.[28] However, the healthcare workers were not informed as to what the observer was monitoring to minimize this potential effect. Lastly, the findings in this study provide immediate intervention effects but further study will be required to determine if these effects are sustainable.

Altering healthcare worker behavior is likely the key element to improve hand hygiene adherence, and behavioral modification may be achieved with the support of leadership at the unit and facility level. However, even though we found significant improvements in healthcare worker hand hygiene adherence after the intervention, the adherence rates are still relatively low compared to reported adherence rates from other countries,[29] suggesting further intervention is needed in this setting to optimize and hygiene practice. Because hand hygiene practice is a crucial strategy to prevent healthcare‐associated infections, every effort should be made to enhance the hand hygiene practice of healthcare workers.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the International Ann Arbor Safety Collaborative (

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

Healthcare‐associated infections are a major cause of illness and death in hospitalized patients, and preventing healthcare‐associated infection is a global challenge.[1] Worldwide, the prevalence of healthcare‐associated infections in developed and undeveloped countries ranges from 5.1% to 11.6% and 5.7% to 19.1%, respectively.[2] In the United States, roughly 2 million such infections occur annually, resulting in approximately 99,000 deaths[3] and estimated annual direct medical costs between $28.4 and $33.8 billion.[4] In Japan, nearly 9% of patients admitted to the intensive care unit (ICU) develop an infection during hospitalization,[5] and 5% of all patients hospitalized become infected with methicillin‐resistant Staphylococcus aureus.[6] The management of healthcare‐associated infections in Japan accounts for up to 5% of total annual healthcare costs, with an estimated $6.8 billion estimated to be potentially preventable.[7] In addition, healthcare‐associated infections are associated with increased length of stay in the hospital. Studies estimate surgical site infections extend length of stay by 9.7 days,[8] and bloodstream infections increase length of stay by 10 days.[9]

Improving hand hygiene practice for healthcare workers is considered a core strategy to decrease the incidence of healthcare‐associated infection.[6, 10] Specifically, the use of alcohol‐based hand rub is strongly recommended in acute care hospitals by both the World Health Organization (WHO) and the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.[11, 12] Improving hand hygiene adherence may reduce healthcare‐associated infection by 9% to 50%,[13, 14] and multiple studies have reported that greater use of alcohol‐based hand rubs results in significant reductions in healthcare‐associated infections.[14, 15]

Due to the difficulty in improving hand hygiene in various settings across the world, the WHO strategy for improving hand hygiene has been adopted and implemented by several studies in varying locations, such as Costa Rica, Italy, Mali, Pakistan, and Saudi Arabia.[16] Implementations of these multimodal strategies, following WHObased guidelines, have been shown to increase the level of hand hygiene adherence among healthcare workers and reduce infections at these locations.[14, 17, 18] This study expands upon that work by extending the same implementation strategy to assess the effectiveness of the introduction of alcohol‐based hand rub on hand hygiene practice at multiple hospitals in Japan.

In a previous article[19] we reported results from an observational study assessing healthcare worker hand hygiene adherence before touching the patient in 4 geographically diverse hospitals in Japan. The study reported that hand hygiene adherence in Japanese hospitals was lower than reported mean values from other international studies, and that greater adherence to hand hygiene should be encouraged. In this article, we present the results of a multimodal intervention intended to improve levels of healthcare worker hand hygiene in 3 of these hospitals.

METHODS

Participating Institutions

Three of the 4 hospitals participating in the prior observational study chose to participate in this intervention. Evaluation of hand hygiene practice was performed in at least 3 wards of each hospital including an inpatient surgical ward, an inpatient medicine ward, an ICU, or an emergency ward.

Table 1 lists the characteristics of the participating hospitals. Hospital A is a university‐affiliated, tertiary care medical center with 312 beds in East Japan. Although the hospital did not have an infection prevention unit or designated infection control nurses during the preintervention periods, the hospital hired a designated infection prevention nurse and established a department of infection prevention before this intervention in April 2012. Hospital B is a community‐based, tertiary care medical center with 428 beds, located in Midwest Japan. Although the facility had no infection control nurses at the outset of the study, a physician certified by the American Board of Internal Medicine and Infectious Diseases provided educational sessions of hand hygiene. Hospital B hired a designated infection prevention nurse and established a department of infection prevention in April 2012. Hospital C, located in Northern Japan, is a community‐based, tertiary care medical center with 562 beds. The department of infection prevention was established in 2010 and has 1 full‐time and 2 part‐time infection prevention nurses.

| Hospital A | Hospital B | Hospital C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Preintervention | Postintervention | Preintervention | Postintervention | Preintervention | Postintervention | |

| ||||||

| Hospital characteristics | ||||||

| Location | East Japan | Midwest Japan | Northern Japan | |||

| Hospital type | University affiliated | Community based | Community based | |||

| Level of care | Tertiary care | Tertiary care | Tertiary care | |||

| Residency program | Yes | Yes | Yes | |||

| No. of beds | 250 | 312 | 428 | 428 | 550 | 562 |

| No. of employees | 398 | 475 | 1,035 | 1,263 | 1,500 | 1,568 |

| No. of physicians | 73 | 91 | 179 | 188 | 207 | 217 |

| No. of nurses | 172 | 210 | 410 | 540 | 616 | 800 |

| Infection control practice | ||||||

| Establishment of infection prevention units (year) | N/A | Yes (2012) | N/A | Yes (2012) | Yes (2010) | Yes |

| Employment of certified nurses in infection control (FTE) | 0 | 1 (1) | 0 | 1 (1) | 3 (1.5) | 3 (1.5) |

| Employment of ABIM‐IDcertified physician | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 |

Role of the Funding Source

This study was unfunded. The prize for the contest was provided by an American collaborator (S.S.) who was not affiliated with any of the participating hospitals.

Intervention

In the prior preintervention study, hand hygiene adherence rates of healthcare workers were evaluated between July 2011 and November 2011.[19] To improve hand hygiene adherence in these facilities, we initiated a multimodal intervention based on WHO recommendations and the findings from the prior study. Each facility was provided the same guidance on how to improve hand hygiene adherence (Table 2) and encouraged to tailor the intervention to their local setting. As an added incentive, we initiated a contest, where the facility obtaining the highest hand hygiene adherence postintervention would win a trophy and 500,000 Japanese yen (approximately $5000 US dollars). The recommended strategies consisted of 15 components (Table 2): infrastructure (3 components), training and education (2 components), evaluation and feedback (5 components), reminder in the workplace (1 component), and institution safety climate (4 components). Of note, the participating institutions had already implemented a varying number of the intervention components prior to the start of the intervention. Each facility conducted a 6‐month intervention to improve hand hygiene adherence; however, the actual timing of interventions varied slightly by institution. Hospitals A and C conducted an intervention from October 2012 through March 2013, whereas hospital B's intervention was from April 2012 to September 2012. Details of the multimodal intervention performed at each participating hospital are shown in Table 3.

| Intervention Components | Description |

|---|---|

| 1. Infrastructure (3 components) | |

| Hand‐washing faucets for each room | At least 1 faucet and sink for each room was available. |

| Placement of alcohol hand rub at patient's room entrance | Alcohol hand rub was placed at all patient room entrances. |

| Portable alcohol hand rub distributed for each healthcare worker | Personal, portable alcohol hand rub dispensers were provided for healthcare workers who contact patients. |

| 2. Training/education (2 components) | |

| Educational resources | At least 1 physician or 1 nurse who provides educational sessions regarding hand hygiene practice was available. |

| Periodic seminars and lectures regarding hand hygiene education | Hospital‐wide hand hygiene seminar or educational activities were held during the intervention period. |

| 3. Evaluation and feedback (5 components) | |

| Evaluation of hand hygiene practice by direct observation | Hospitals utilize direct observation for healthcare worker's hand hygiene practice. |

| Evaluation of hand hygiene practice by monitoring the amount of alcohol hand rub consumption | Hospitals utilize the amount of alcohol hand rub consumption as a parameter for healthcare worker's hand hygiene practice. |

| Hand hygiene rate feedback at infection control committee | Hand hygiene adherence rate was reported and discussed at hospital infection control committee. |

| Hand hygiene rate feedback to the designated wards/units | Hand hygiene adherence rate was reported and discussed with healthcare workers at the designated wards/units where hand hygiene observation was performed. |

| Granting the award of top‐rated person of hand hygiene | Hospitals established the system to assess individual healthcare worker's hand hygiene adherence rate. |

| 4. Reminder in the workplace (1 components) | |

| Poster notification | Poster notification for hand hygiene practice was performed in the intervention period. |

| 5. Institutional safety climate (4 components) | |

| Commitment of hospital president or hospital executives | Hospital executives including the president agreed on the importance of hand hygiene practice and declared to healthcare workers to enhance hand hygiene practice during the intervention period. |

| Commitment of nurse managers and physician leaders | Commitment of improving hand hygiene practice by representative healthcare workers at the designated wards/units (eg, meeting by nurse manager or physician leaders at the designated wards/units and collaborative work with infection prevention services). |

| Meeting at the designated wards/units | A ward/unit‐level meeting or voluntary session for hands‐on hand hygiene practice by healthcare workers at the designated wards/units. |

| Identifying champions at the designated wards/units | An individual healthcare worker who contributed to improving hand hygiene practice was appointed. |

| Hospital A | Hospital Ba | Hospital C | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||

| Intervention period | October 2012March 2013 | April 2012September 2012 | October 2012March 2013 | |||

| Evaluation of hand hygiene in the postintervention period | May 2013July 2013 | October 2012 | June 2013 | |||

| Suggested intervention components | Preintervention | Postintervention | Preintervention | Postintervention | Preintervention | Postintervention |

| No. of implemented components | 2/15 | 10/15 | 9/15 | 10/15 | 6/15 | 8/15 |

| Infrastructure (3 components) | ||||||

| Hand‐washing faucets for each room | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Placement of alcohol hand rubs at patient's room entrance | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Portable alcohol hand rub distributed for each healthcare worker | No | Yesb | No | Yesb | No | No |

| Training/education (2 components) | ||||||

| Educational resources | No | Yesb | Yes | Yesb | Yes | Yes |

| Periodic seminars and lectures regarding hand hygiene education | No | Yesb | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Evaluation and feedback (5 components) | ||||||

| Evaluation of hand hygiene practice by direct observation | No | Yesb | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Evaluation of hand hygiene practice by the amount of alcohol hand rub consumption | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Hand hygiene rate feedback at infection control committee | No | Yesb | Yes | Yes | No | Yesb |

| Hand hygiene rate feedback to designated departments | No | Yesb | Yes | Yes | No | Yesb |

| Granting the award of top‐rated person | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Reminders in the workplace (1 component) | ||||||

| Poster notification | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5. Institutional safety climate (4 components) | ||||||

| Commitment of hospital president or hospital executives | No | Yesb | No | No | No | No |

| Commitment of nurse managers and physicians leaders | No | Yesb | No | No | No | No |

| Meeting regarding hand hygiene practice by the designated wards/units | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| Identifying champions at the designated wards/units | No | No | No | No | No | No |

Observation of Hand Hygiene Practice

The same methods for hand hygiene observation used for the preintervention study was used for postintervention assessment. Ten distinct units across the 3 participating hospitals were evaluated for healthcare worker hand hygiene prior to patient contact. Three to 4 units were observed at each facility. One of the study authors (T.S.), a Japanese board‐certified infection control nurse, conducted all of the hand hygiene observations for both the preintervention and postintervention studies. Intraobserver variation was minimized by providing the same training outlined in the previous study.[19] Appropriate hand hygiene was defined as the use of soap and water or alcohol‐based hand rub before patient contact, which corresponds to the first moment of the WHO's 5 moments of hand hygiene.[11]

Hand hygiene practice prior to patient contact for each individual provider‐patient encounter was observed and recorded using the hand hygiene observation form adapted from a previous study by Saint et al.[6, 20] Identical to the preintervention study,[19] the form captured the following information: unit in which observations were performed, time of initiation and completion of observations, healthcare worker subgroup (physician or nurse), and the type of hand hygiene before patient contact (ie, hand washing with soap and water, use of alcohol‐based hand rub, or no hand hygiene). Unit physicians and nurses were informed that their clinical practices were going to be observed, but were not informed of the purpose of the observations (eg, hand hygiene adherence). To avoid interfering with clinical care delivery, the observer was given strict instructions to maintain a certain distance from the observed healthcare workers. The observer was instructed to leave immediately if asked for any reason by the unit staff or patients.

Statistical Analysis

Overall hand hygiene adherence rates were calculated and compared between the pre‐ and the postintervention periods. Comparison of hand hygiene adherence by healthcare worker subgroup and by hospital unit between the pre‐ and postintervention periods was also performed. Hand hygiene adherence rates were compared using JMP 9.0 and SAS 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Comparison of hand hygiene adherence rates by observational periods was calculated by Pearson [2] tests, and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were estimated using binomial distribution. Pearson correlations were used to determine the relationship of hand hygiene between physicians and nurses in the same unit. Two‐tailed P value0.05 was considered statistically significant. The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the ethics committees at the participating hospitals.

RESULTS

Data were collected from May 2013 to July 2013 in hospital A, in October 2012 in hospital B, and June 2013 in hospital C to ensure data were collected after the 6‐month intervention at each site. A total of 2982 observations of hand hygiene were performed in 10 distinct units across the 3 participating hospitals during the postintervention periods. Hand hygiene observations were performed during the day Monday through Friday between 8:30 am and 7:30 pm, with the majority occurring prior to 1:00 pm.

The overall postintervention hand hygiene adherence rate (in all 3 hospitals) was significantly higher at 32.7% (974/2982) adherence compared to 18.0% (482/2679) adherence in the preintervention period (P<0.001). An increased hand hygiene adherence rate in each participating hospital in the postintervention period was observed (Figure 1). Similar trends of higher overall hand hygiene adherence rates for both nurses and physicians in the postintervention period were seen. Use of alcohol‐based hand rub among those with appropriate hand hygiene was significantly higher, with 90.0% (880/974) using hand rub in the postintervention period versus 67.0% (322/482) in the preintervention period (P<0.001). Comparison of overall hand hygiene adherence rates by unit type and healthcare worker subgroup between the pre‐ and postintervention periods are shown in Table 4. Detailed comparisons of hand hygiene adherence rates for each hospital are available in the supplementary appendix. Although a significant improvement of hand hygiene practice was observed in the majority of participating units (6/10), there was a significant decline in hand hygiene practice in 2 units for nurses and 1 unit for physicians. Hand hygiene adherence rates by healthcare worker subgroups (both physicians and nurses) were significantly higher in the postintervention period than those in the preintervention period. Trends toward higher hand hygiene adherence rate of nurses in the postintervention period were observed (34.8% adherence for nurses compared to 30.4% adherence for physicians); the difference between nurses and physicians were not statistically significant (P=0.07).

| Ward/Unit | Healthcare Worker Subgroup | Preintervention Period | Postintervention Period | Improvement After Intervention (%) | P Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of Observations | Hand hygiene Adherence (%) | No. of Observations | Hand Hygiene Adherence (%) | ||||

| |||||||

| All 3 hospitals | |||||||

| Surgery | Nurse | 455 | 20 | 480 | 40 | 20 | <0.001 |

| Physician | 424 | 18 | 448 | 43 | 25 | <0.001 | |

| All | 879 | 19 | 928 | 41 | 22 | <0.001 | |

| Medicine | Nurse | 455 | 23 | 508 | 39 | 16 | <0.001 |

| Physician | 435 | 15 | 452 | 33 | 18 | <0.001 | |

| All | 890 | 20 | 960 | 36 | 16 | <0.001 | |

| ICU | Nurse | 305 | 21 | 379 | 25 | 4 | 0.17 |

| Physician | 203 | 9 | 268 | 28 | 19 | <0.001 | |

| All | 508 | 16 | 647 | 26 | 10 | <0.001 | |

| ED | Nurse | 170 | 16 | 173 | 27 | 11 | 0.01 |

| Physician | 232 | 14 | 274 | 9 | ‐5 | 0.07 | |

| All | 402 | 15 | 447 | 16 | 1 | 0.64 | |

| All units | Nurse | 1385 | 21 | 1540 | 35 | 14 | <0.001 |

| Physician | 1294 | 15 | 1442 | 30 | 15 | <0.001 | |

| All | 2679 | 18 | 2982 | 33 | 15 | <0.001 | |