User login

Pseudoverrucous Papules and Nodules Around a Surgical Stoma

Pseudoverrucous Papules and Nodules Around a Surgical Stoma

To the Editor:

A 22-year-old man was referred to our dermatology outpatient department for wartlike growths that gradually developed around a postoperative enteroatmospheric fistula and stoma over the past 4 months. The patient presented for an emergency exploratory laparotomy with a history of perforation peritonitis 1.5 years prior to the current presentation. He also had a small bowel obstruction 5 months prior to the current presentation that resulted in the resection of a large segment of the small bowel. He underwent a diverting loop ileostomy when the abdominal closure was not achieved because of bowel edema, following which he developed a postoperative enteroatmospheric fistula. In addition, the stoma retracted and was followed by dermal dehiscence, which led to notable leakage and resulted in heavy fecal contamination of the midline wound.

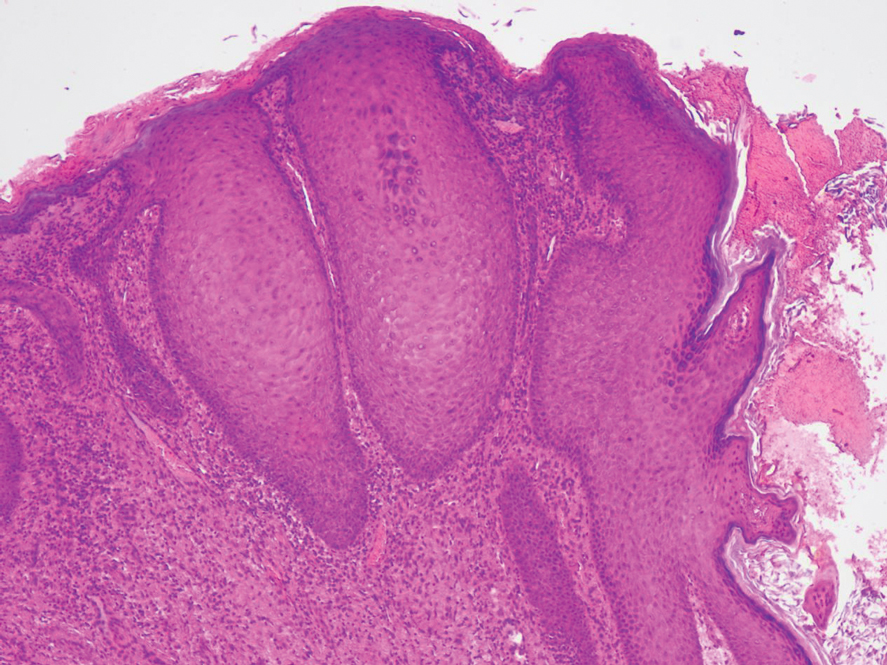

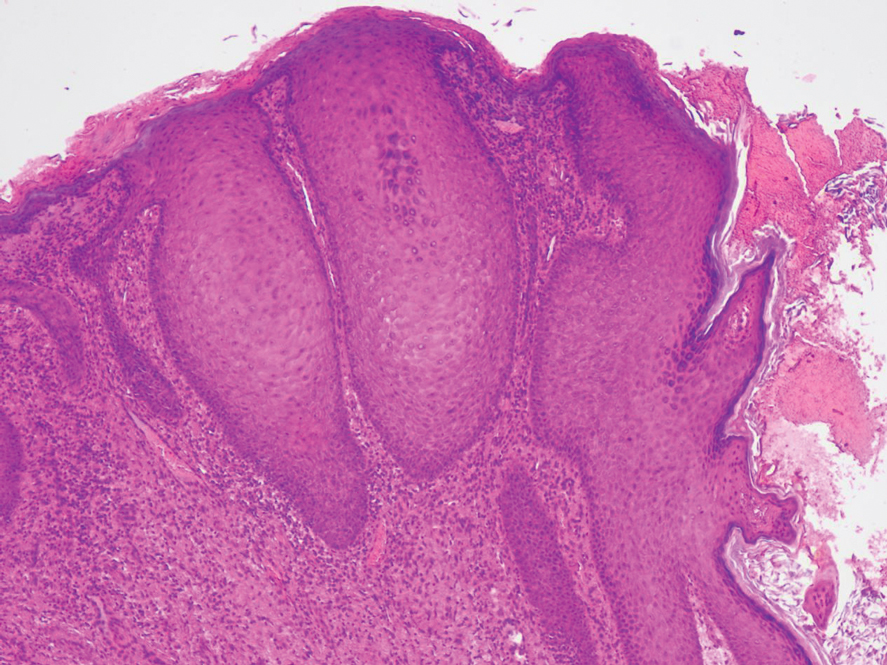

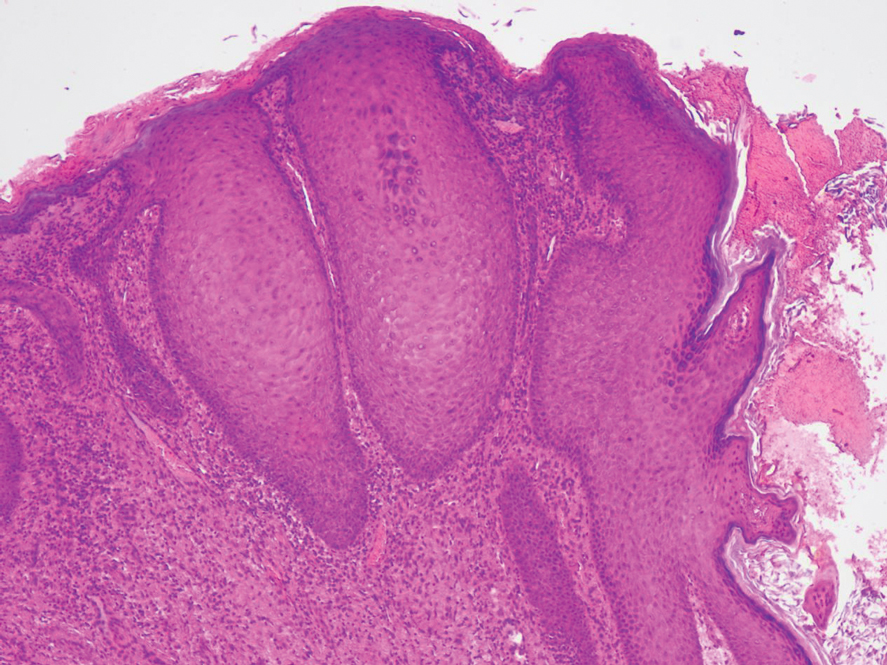

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed multiple grayish-white, dome-shaped, moist papules coalescing to form a peristomal pseudoverrucous mass on the lower side of the stoma (Figure 1). The patient experienced mild itching. The lesion showed no signs of erosion, bleeding, or purulent discharge, and there were no nearby lumps or enlarged lymph nodes. The differential diagnosis included peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, pseudoverrucous papules and nodules (PPNs), squamous cell carcinoma, and exuberant granulation tissue. A skin biopsy was performed, and histopathology revealed hyperkeratosis, moderate papillomatosis, and marked acanthotic hyperplasia seen as downgrowths into the dermis (Figure 2). No koilocytes, atypia, or mitotic figures were present. Abundant neutrophils and few eosinophils were seen in the dermal infiltrate. A final diagnosis of PPN was made based on clinicopathologic correlation. The patient was advised to use a smaller stoma bag and to change the collection pouch frequently to reduce skin contact with fecal matter.

Peristomal skin conditions are reported in 18% to 55% of patients with stomas and include allergic contact dermatitis, mechanical dermatitis, infections, pyoderma gangrenosum, and irritant contact dermatitis.1,2 Pseudoverrucous papules (also called chronic papillomatous dermatitis or pseudoverrucous lesions) is a rare dermatologic complication found on the skin around stomas,3 most commonly around urostomy stomas. The presence of PPNs around colostomy stomas and the perianal region is extremely rare.2,4 This condition is the result of chronic irritant dermatitis from frequent exposure to urine or feces, leading to maceration and epidermal hyperplasia. It occurs because of improper sizing of the stoma bag or incorrect positioning or construction of the stoma.5

the overuse of topical benzocaine-resorcinol, leading to chronic irritation.6 It is clinically characterized by multiple grayish-white, wartlike, confluent papulonodules around areas chronically exposed to moisture. Differential diagnoses such as secondary neoplasms, HPV infection, exuberant granulation tissue, and candidal infections should be considered.3 Final diagnosis is based on clinicopathologic findings, similar to our case. Epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor are thought to play a role in the pathophysiology of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Increased expression of these mediators leads to proliferation of the epidermis into the dermis.7 The role of HPV in PPN remains unclear, as not all PPN lesions are positive for HPV and the cutaneous lesions resolve once the source of irritation is removed. Recommended treatment includes local skin care; stoma refitting; and, in severe cases, excision and revision of the stoma.2 Dermatologists must be aware of this often-underdiagnosed condition.

- Alslaim F, Al Farajat F, Alslaim HS, et al. Etiology and management of peristomal pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Cureus. 2021;13 :E20196. doi:10.7759/cureus.20196

- Rambhia PH, Conic RZ, Honda K, et al. Chronic papillomatous dermatitis in a patient with a urinary ileal diversion: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Arch. 2017;1:47-50. doi:10.36959/661/297

- Latour-Álvarez I, García-Peris E, Pestana-Eliche MM, et al. Nodular peristomal lesions. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;108:363-364. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2016.02.018

- Dandale A, Dhurat R, Ghate S. Perianal pseudoverrucous papules and nodules. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2013;34:44-46. doi:10.4103/0253-7184.112939

- Brogna L. Prevention and management of pseudoverrucous lesions: a review and case scenarios. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2021;34:461-471. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000758620.93518.39

- Robson KJ, Maughan JA, Purcell SD, et al. Erosive papulonodular dermatosis associated with topical benzocaine: a report of two cases and evidence that granuloma gluteale, pseudoverrucous papules, and Jacquet’s erosive dermatitis are a disease spectrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5 suppl):S74-S80. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2005.12.025

- Oğuz ID, Vural S, Cinar E, et al. Peristomal pseudoverrucous lesions: a rare skin complication of colostomy. Cureus. 2023;15:E38068. doi:10.7759/cureus.38068

To the Editor:

A 22-year-old man was referred to our dermatology outpatient department for wartlike growths that gradually developed around a postoperative enteroatmospheric fistula and stoma over the past 4 months. The patient presented for an emergency exploratory laparotomy with a history of perforation peritonitis 1.5 years prior to the current presentation. He also had a small bowel obstruction 5 months prior to the current presentation that resulted in the resection of a large segment of the small bowel. He underwent a diverting loop ileostomy when the abdominal closure was not achieved because of bowel edema, following which he developed a postoperative enteroatmospheric fistula. In addition, the stoma retracted and was followed by dermal dehiscence, which led to notable leakage and resulted in heavy fecal contamination of the midline wound.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed multiple grayish-white, dome-shaped, moist papules coalescing to form a peristomal pseudoverrucous mass on the lower side of the stoma (Figure 1). The patient experienced mild itching. The lesion showed no signs of erosion, bleeding, or purulent discharge, and there were no nearby lumps or enlarged lymph nodes. The differential diagnosis included peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, pseudoverrucous papules and nodules (PPNs), squamous cell carcinoma, and exuberant granulation tissue. A skin biopsy was performed, and histopathology revealed hyperkeratosis, moderate papillomatosis, and marked acanthotic hyperplasia seen as downgrowths into the dermis (Figure 2). No koilocytes, atypia, or mitotic figures were present. Abundant neutrophils and few eosinophils were seen in the dermal infiltrate. A final diagnosis of PPN was made based on clinicopathologic correlation. The patient was advised to use a smaller stoma bag and to change the collection pouch frequently to reduce skin contact with fecal matter.

Peristomal skin conditions are reported in 18% to 55% of patients with stomas and include allergic contact dermatitis, mechanical dermatitis, infections, pyoderma gangrenosum, and irritant contact dermatitis.1,2 Pseudoverrucous papules (also called chronic papillomatous dermatitis or pseudoverrucous lesions) is a rare dermatologic complication found on the skin around stomas,3 most commonly around urostomy stomas. The presence of PPNs around colostomy stomas and the perianal region is extremely rare.2,4 This condition is the result of chronic irritant dermatitis from frequent exposure to urine or feces, leading to maceration and epidermal hyperplasia. It occurs because of improper sizing of the stoma bag or incorrect positioning or construction of the stoma.5

the overuse of topical benzocaine-resorcinol, leading to chronic irritation.6 It is clinically characterized by multiple grayish-white, wartlike, confluent papulonodules around areas chronically exposed to moisture. Differential diagnoses such as secondary neoplasms, HPV infection, exuberant granulation tissue, and candidal infections should be considered.3 Final diagnosis is based on clinicopathologic findings, similar to our case. Epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor are thought to play a role in the pathophysiology of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Increased expression of these mediators leads to proliferation of the epidermis into the dermis.7 The role of HPV in PPN remains unclear, as not all PPN lesions are positive for HPV and the cutaneous lesions resolve once the source of irritation is removed. Recommended treatment includes local skin care; stoma refitting; and, in severe cases, excision and revision of the stoma.2 Dermatologists must be aware of this often-underdiagnosed condition.

To the Editor:

A 22-year-old man was referred to our dermatology outpatient department for wartlike growths that gradually developed around a postoperative enteroatmospheric fistula and stoma over the past 4 months. The patient presented for an emergency exploratory laparotomy with a history of perforation peritonitis 1.5 years prior to the current presentation. He also had a small bowel obstruction 5 months prior to the current presentation that resulted in the resection of a large segment of the small bowel. He underwent a diverting loop ileostomy when the abdominal closure was not achieved because of bowel edema, following which he developed a postoperative enteroatmospheric fistula. In addition, the stoma retracted and was followed by dermal dehiscence, which led to notable leakage and resulted in heavy fecal contamination of the midline wound.

At the current presentation, physical examination revealed multiple grayish-white, dome-shaped, moist papules coalescing to form a peristomal pseudoverrucous mass on the lower side of the stoma (Figure 1). The patient experienced mild itching. The lesion showed no signs of erosion, bleeding, or purulent discharge, and there were no nearby lumps or enlarged lymph nodes. The differential diagnosis included peristomal pyoderma gangrenosum, human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, pseudoverrucous papules and nodules (PPNs), squamous cell carcinoma, and exuberant granulation tissue. A skin biopsy was performed, and histopathology revealed hyperkeratosis, moderate papillomatosis, and marked acanthotic hyperplasia seen as downgrowths into the dermis (Figure 2). No koilocytes, atypia, or mitotic figures were present. Abundant neutrophils and few eosinophils were seen in the dermal infiltrate. A final diagnosis of PPN was made based on clinicopathologic correlation. The patient was advised to use a smaller stoma bag and to change the collection pouch frequently to reduce skin contact with fecal matter.

Peristomal skin conditions are reported in 18% to 55% of patients with stomas and include allergic contact dermatitis, mechanical dermatitis, infections, pyoderma gangrenosum, and irritant contact dermatitis.1,2 Pseudoverrucous papules (also called chronic papillomatous dermatitis or pseudoverrucous lesions) is a rare dermatologic complication found on the skin around stomas,3 most commonly around urostomy stomas. The presence of PPNs around colostomy stomas and the perianal region is extremely rare.2,4 This condition is the result of chronic irritant dermatitis from frequent exposure to urine or feces, leading to maceration and epidermal hyperplasia. It occurs because of improper sizing of the stoma bag or incorrect positioning or construction of the stoma.5

the overuse of topical benzocaine-resorcinol, leading to chronic irritation.6 It is clinically characterized by multiple grayish-white, wartlike, confluent papulonodules around areas chronically exposed to moisture. Differential diagnoses such as secondary neoplasms, HPV infection, exuberant granulation tissue, and candidal infections should be considered.3 Final diagnosis is based on clinicopathologic findings, similar to our case. Epidermal growth factor and transforming growth factor are thought to play a role in the pathophysiology of pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Increased expression of these mediators leads to proliferation of the epidermis into the dermis.7 The role of HPV in PPN remains unclear, as not all PPN lesions are positive for HPV and the cutaneous lesions resolve once the source of irritation is removed. Recommended treatment includes local skin care; stoma refitting; and, in severe cases, excision and revision of the stoma.2 Dermatologists must be aware of this often-underdiagnosed condition.

- Alslaim F, Al Farajat F, Alslaim HS, et al. Etiology and management of peristomal pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Cureus. 2021;13 :E20196. doi:10.7759/cureus.20196

- Rambhia PH, Conic RZ, Honda K, et al. Chronic papillomatous dermatitis in a patient with a urinary ileal diversion: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Arch. 2017;1:47-50. doi:10.36959/661/297

- Latour-Álvarez I, García-Peris E, Pestana-Eliche MM, et al. Nodular peristomal lesions. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;108:363-364. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2016.02.018

- Dandale A, Dhurat R, Ghate S. Perianal pseudoverrucous papules and nodules. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2013;34:44-46. doi:10.4103/0253-7184.112939

- Brogna L. Prevention and management of pseudoverrucous lesions: a review and case scenarios. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2021;34:461-471. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000758620.93518.39

- Robson KJ, Maughan JA, Purcell SD, et al. Erosive papulonodular dermatosis associated with topical benzocaine: a report of two cases and evidence that granuloma gluteale, pseudoverrucous papules, and Jacquet’s erosive dermatitis are a disease spectrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5 suppl):S74-S80. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2005.12.025

- Oğuz ID, Vural S, Cinar E, et al. Peristomal pseudoverrucous lesions: a rare skin complication of colostomy. Cureus. 2023;15:E38068. doi:10.7759/cureus.38068

- Alslaim F, Al Farajat F, Alslaim HS, et al. Etiology and management of peristomal pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia. Cureus. 2021;13 :E20196. doi:10.7759/cureus.20196

- Rambhia PH, Conic RZ, Honda K, et al. Chronic papillomatous dermatitis in a patient with a urinary ileal diversion: a case report and review of the literature. Dermatol Arch. 2017;1:47-50. doi:10.36959/661/297

- Latour-Álvarez I, García-Peris E, Pestana-Eliche MM, et al. Nodular peristomal lesions. Actas Dermosifiliogr. 2016;108:363-364. doi:10.1016/j.ad.2016.02.018

- Dandale A, Dhurat R, Ghate S. Perianal pseudoverrucous papules and nodules. Indian J Sex Transm Dis AIDS. 2013;34:44-46. doi:10.4103/0253-7184.112939

- Brogna L. Prevention and management of pseudoverrucous lesions: a review and case scenarios. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2021;34:461-471. doi:10.1097/01.ASW.0000758620.93518.39

- Robson KJ, Maughan JA, Purcell SD, et al. Erosive papulonodular dermatosis associated with topical benzocaine: a report of two cases and evidence that granuloma gluteale, pseudoverrucous papules, and Jacquet’s erosive dermatitis are a disease spectrum. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(5 suppl):S74-S80. doi:10.1016/j .jaad.2005.12.025

- Oğuz ID, Vural S, Cinar E, et al. Peristomal pseudoverrucous lesions: a rare skin complication of colostomy. Cureus. 2023;15:E38068. doi:10.7759/cureus.38068

Pseudoverrucous Papules and Nodules Around a Surgical Stoma

Pseudoverrucous Papules and Nodules Around a Surgical Stoma

PRACTICE POINTS

- Pseudoverrucous papules and nodules (PPNs) can develop around stomas due to chronic irritant dermatitis from fecal or urinary exposure.

- Proper stoma management, including the use of appropriately sized stoma bags and frequent changes, is essential to prevent skin complications such as PPN.

- When evaluating peristomal lesions, consider a broad differential diagnosis, including infections, neoplasms, and dermatitis, and ensure thorough clinicopathologic correlation for accurate diagnosis and treatment.

Cutaneous Signs of Piety

Religious practices can lead to cutaneous changes, and awareness of these changes is of paramount importance in establishing the cause. We review the cutaneous changes related to religious practices, including the Semitic religions, Hinduism, and Sikhism (Table). The most widely followed Semitic religions are Christianity, Islam, and Judaism. Christianity and Islam collectively account for more than half of the world’s population.1

Christianity

Christian individuals are prone to blisters that develop below the knees due to repeated kneeling in prayer.2 A case of allergic contact dermatitis to a wooden cross made from Dalbergia nigra has been reported.3 Localized swelling with hypertrichosis due to muscular hypertrophy in the lower neck above the interscapular region has been described in well-built men who lift weights to bear pasos (floats with wooden sculptures) during Holy Week in Seville, Spain.4

Islam

Cutaneous signs of piety have been well documented in Muslim individuals. The most common presentation is hyperpigmentation of the forehead, usually noted as a secondary finding in patients seeking treatment of unrelated symptoms.5 Cutaneous changes in this region correspond with the area of the forehead that rests on the carpet during prayer. Macules typically present on the upper central aspect of the forehead close to the hairline and/or in pairs above the medial ends of the eyebrows; sometimes 3 or 4 lesions may be present in this area with involvement of the nasion (Figure 1).6

In Saudi Arabia where Sunni Islam predominates, Muslim individuals observe prayer 5 times per day. Calluses have been observed in areas of the body that are frequently subject to friction during this practice.7 For instance, calluses are more prominent on the right knee (Figure 2) and the left ankle, which bear the individual’s weight during prayer, and typically become nodular over time (Figure 3). In Arabic, these calluses are referred to as zabiba.8

A notable finding in followers of Shia Islam, which predominates in Iran, is the development of small nodules on the forehead, possibly caused by rubbing the forehead on a flat disclike prayer stone called a mohr during daily prayer,9 which is said to enhance public esteem.10 The nodules generally are asymptomatic, but some individuals experience minimal pain on pressure.8 Ulceration of the nodules has rarely been observed.7

Limited access to thick and soft carpets and rarely bony exostoses or obesity are factors associated with prayer that can lead to skin changes (known as prayer signs), as they render the skin sensitive to pressure. Localized alopecia may occur on the forehead in individuals with low or pointed hairlines. An unexplained finding noted by one of the authors (K.A.) in some elderly Muslim individuals is that hair located on the forehead at the point of pressure during prayer remains pigmented, while the rest of the hair on the scalp turns white. Hyperpigmentation of the knuckles may be seen in individuals who use closed fists to rise from the ground following prayer. Except for mild hyperpigmentation of the knees,7 Muslim women rarely develop these changes, as they either do not pray,10 particularly during menstruation or puerperium, or they have more subcutaneous fat for protection.7 Some Muslim individuals who pray regularly at home may be conscious of these skin changes and therefore use a soft pillow to rest the forehead during prayer.

The histopathologic findings of prayer signs depend on the extent of lichenification and typically show compact hyperkeratosis or orthokeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, and mild dermal inflammation.8 Increased dermal vascularization and papillary fibrosis unlike that seen in lichen simplex chronicus have been described from skin changes in the lower limbs due to prayer practices.7 Additional findings in forehead biopsies include multiple comedones and epidermoid cysts in elderly patients showing a foreign body granulomatous reaction to hair fragments.10 Deposition of mucinous material in the dermal collagen in a prayer nodule on the forehead has been described in a Shiite individual, possibly due to repetitive microtrauma from the use of a prayer stone.9 Infections developed from sharing communal facilities or performing ritual sacrifices (eg, tinea,11 orf12) are prevalent during the yearly Hajj pilgrimage at Makkah, Saudi Arabia, in addition to other infectious and noninfectious dermatoses.13 Muslim women wearing headscarves secured at the neck with a safety pin have developed vitiligo at that site due to friction.14 Occasionally, Muslim individuals may apply perfumes before prayers, which may cause allergic contact dermatitis.

Judaism

Hyperpigmentation has been described in Jewish men at Talmudic seminaries due to the practice of reciting scriptures, which involves a rocking motion known as daven that leads to friction on the back.15 Lesions associated with this practice typically appear as isolated macules or a continuous linear patch over the skin of the bony protuberances of the inferior thoracic and lumbar vertebrae. Allergic contact dermatitis has been reported in Jewish individuals due to exposure to a variety of agents during religious practices, such as potassium dichromate, which is present in the leather used to make phylacteries or tefillin (boxes containing scripture that are secured to the forehead with straps that are then tied to the left arm during prayer). This finding has been noted in some or all areas of contact including the forehead, scalp, neck, left wrist, and waist.16

It is customary for both Orthodox Jewish and Muslim women to be concealed by clothing, which predisposes them to vitamin D deficiency17,18 but also protects them from developing malignant melanoma.19 Neonates have developed genital herpetic infections following circumcision due to the ancient practice of having the mohel (the person who performs the Jewish circumcision) suck on the wound until the bleeding stops.20

Hinduism

Hinduism espouses an eclectic philosophy of life subsuming numerous beliefs involving guardian deities, invoked by sacred marks, symbols, and rituals. Marks generally are placed on the forehead or other specified sites on the body. Sandalwood paste as well as vibhuti and kumkum powders most commonly are used, which can cause allergic contact dermatitis. Vibhuti is holy ash prepared by burning balls of dried cow dung in a fire pit with rice husk and clarified butter. Kumkum is prepared by alkalinizing turmeric powder, which turns red in color. A case of contact allergic dermatitis was reported in a Hindu priest who regularly used sandalwood paste on the forehead and as a balm for an ailment of the hands and feet.21 In our experience, vibhuti also has caused dermatitis on the forehead as well as on the neck and arms. The main difference between the 2 eruptions is that sandalwood dermatitis generally is localized to the center of the forehead as a circular or vertical mark or often in the center of the left palm, which is used to mix sandalwood powder with water to make a paste (Figure 4), while vibhuti contact dermatitis typically presents as a broad horizontal patch on the forehead because the powder is smeared with the middle 3 fingers (Figure 5). Perfumes used by some Muslim individuals before prayer that are applied on the clothes can mimic this type of contact dermatitis, but eruptions typically are confined to the fingers and palms.22 Contact dermatitis caused by necklaces made with beads of the stem of the Ocimum sanctum (holy basil) plant and seeds of the evergreen tree Elaeocarpus ganitrus have been reported.23 Calluses are sometimes seen in individuals who meditate for long hours while sitting in a cross-legged position and usually occur on or uncommonly below the lateral malleolus of the right foot, similar to practitioners of yoga.24

Hemorrhaging and crusting below the lateral malleolus of the right foot have been reported in Buddhist monks due to sitting in a cross-legged position for prolonged periods of meditation.25 Hyperpigmentation of the knees, ankles, and interphalangeal joints of the feet has been seen after sitting in the traditional Japanese meditative position.26 Tattoos of Hindu gods are common, while tattoos are forbidden in Islam and Judaism. Attributes of prominent deities branded on the body may be seen. Discrete sarcoidlike nodules along the axillae and chest wall have been attributed to a Hindu ritual (kavadi) that is performed annually as a form of self-inflicted punishment for their sins in which devotees pierce the chest wall with spokes to form a base over a heavy cage in which offerings are carried, and skewers passed through the cheeks have resulted in similar nodules in the oral cavity.27,28 Consumption of cow’s urine during rituals may induce acute urticaria.29 Lichen planus of the trunk30 and leukoderma of the waist31 may be induced by köbnerization or contact allergy from wearing sacred threads, respectively.

Sikhism

Sikhism, a religion founded in the 15th century, epitomizes the high-water mark of the syncretism between Hinduism and Islam. Men must abstain from cutting their hair; pulling and knotting the hair to maintain a coiffure can cause traction alopecia in the submandibular region and the frontal and parietal areas of the scalp as well as ridging and furrowing of the scalp resembling cutis verticis gyrata. Fixer, a product used to keep the beard intact, can cause contact dermatitis. The tight broad band of cloth (known as a ribbon) that is worn around the head to keep hair intact beneath a turban may cause forehead lesions. Discoid lupus erythematosus–like lesions or painful chondrodermatitis of the pinnae due to pressure from wearing a starched turban have been observed, also called “turban ear” from prominence of both anthelices.32,33 A case of a Sikh man who developed oral sarcoidal lesions from body piercing has been reported.28

Conclusion

Knowledge of the religious practices of patients would help in recognizing puzzling and peculiar dermatoses. It may not be possible to eliminate the causes of these conditions, but methods to reduce their effects on the skin can be discussed with patients.

Acknowledgments—We are grateful to the valuable help rendered by Joginder Kumar, MD, New Delhi, India, and C. Indira, MD, Hyderabad, India.

- The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. The Global Religious Landscape: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World’s Major Religious Groups as of 2010. Washington, DC: The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, The Pew Research Center; 2012.

- Goodheart HP. “Devotional dermatoses”: a new nosologic entity? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:543.

- Fisher AA, Bikowski J. Allergic dermatitis due to a wooden cross made of Dalbergia nigra. Contact Dermatitis. 1981;7:45-46.

- Camacho F. Acquired circumscribed hypertrichosis in the ‘costaleros’ who bear the ‘pasos’ during Holy Week in Seville, Spain. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:361-363.

- Mishriki YY. Skin commotion from repetitive devotion. prayer callus. Postgrad Med. 1999;105:153-154.

- Barankin B. Prayer marks. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:985-986.

- Abanmi AA, Al Zouman AY, Al Hussaini H, et al. Prayer marks. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:411-414.

- Kahana M, Cohen M, Ronnen M, et al. Prayer nodules in Moslem men. Cutis. 1986;38:281-282.

- O’Goshi KI, Aoyama H, Tagami H. Mucin deposition in a prayer nodule on the forehead. Dermatology. 1998;196:364.

- Vollum DI, Azadeh B. Prayer nodules. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1979;4:39-47.

- Arrese JE, Piérard-Franchimont C, Piérard GE. Scytalidium dimidiatum melanonychia and scaly plantar skin in four patients from the Maghreb: imported disease or outbreak in a Belgian mosque? Dermatology. 2001;202:183-185.

- Malik M, Bharier M, Tahan S, et al. Orf acquired during religious observance. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:606-608.

- Mimesh SA, Al-Khenaizan S, Memish ZA. Dermatologic challenge of pilgrimage. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:52-61.

- El-Din Anbar T, Abdel-Rahman AT, El-Khayyat MA, et al. Vitiligo on anterior aspect of neck in Muslim females: case series. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:178-179.

- Naimer SA, Trattner A, Biton A, et al. Davener’s dermatosis: a variant of friction hypermelanosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:442-445.

- Feit NE, Weinberg JM, DeLeo VA. Cutaneous disease and religious practice: case of allergic contact dermatitis to tefillin and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:886-888.

- Mukamel MN, Weisman Y, Somech R, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency in Orthodox and non-Orthodox Jewish mothers in Israel. Isr Med Assoc J. 2001;3:419-421.

- Hatun S, Islam O, Cizmecioglu F, et al. Subclinical vitamin D deficiency is increased in adolescent girls who wear concealing clothing. J Nutr. 2005;135:218-222.

- Vardi G, Modan B, Golan R, et al. Orthodox Jews have a lower incidence of malignant melanoma. a note on the potentially protective role of traditional clothing. Int J Cancer. 1993;53:771-773.

- Gesundheit B, Grisaru-Soen G, Greenberg G, et al. Neonatal genital herpes virus type 1 infection after Jewish ritual circumcision: modern medicine and religious tradition. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e259-e263.

- Pasricha JS, Ramam M. Contact dermatitis due to sandalwood (Santalum album Linn). Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1986;52:232-233.

- Carmichael AJ, Foulds IS. Sensitization as a result of a religious ritual. Br J Dermatol. 1990;123:846.

- Bajaj AK, Saraswat A. Contact dermatitis. In: Valia RG, Valia AR, eds. Textbook of Dermatology. 3rd ed. Mumbai, India: Bhalani Publishing House; 2008:545-549.

- Verma SB, Wollina U. Callosities of cross-legged sitting: “yoga sign”—an under-recognized cultural cutaneous presentation. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:1212-1214.

- Rehman H, Asfour NA. Clinical images: prayer nodules [published online ahead of print November 16, 2009]. CMAJ. 2010;182:e19.

- Ruhnke WG, Serizawa Y. Viral pericarditis. BMJ. 2010;340:b5579.

- Nayar M. Sarcoidosis on ritual scarification. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:116-118.

- Ng KH, Siar CH, Ganesapillai T. Sarcoid-like foreign body reaction in body piercing: a report of two cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Radiol Endod. 1997;84:28-31.

- Bhalla M, Thami GP. Acute urticaria following ‘gomutra’ (cow’s urine) gargles. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:722-723.

- Joshi A, Agarwalla A, Agrawal S, et al. Köbner phenomenon due to sacred thread in lichen planus. J Dermatol. 2000;27:129-130.

- Banerjee K, Banerjee R, Mandal B. Amulet string contact leukoderma and its differentiation from vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:180-181.

- Kanwar AJ, Kaur S. Some dermatoses peculiar to Sikh men. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:739-740.

- Williams HC. Turban ear. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:117-119.

Religious practices can lead to cutaneous changes, and awareness of these changes is of paramount importance in establishing the cause. We review the cutaneous changes related to religious practices, including the Semitic religions, Hinduism, and Sikhism (Table). The most widely followed Semitic religions are Christianity, Islam, and Judaism. Christianity and Islam collectively account for more than half of the world’s population.1

Christianity

Christian individuals are prone to blisters that develop below the knees due to repeated kneeling in prayer.2 A case of allergic contact dermatitis to a wooden cross made from Dalbergia nigra has been reported.3 Localized swelling with hypertrichosis due to muscular hypertrophy in the lower neck above the interscapular region has been described in well-built men who lift weights to bear pasos (floats with wooden sculptures) during Holy Week in Seville, Spain.4

Islam

Cutaneous signs of piety have been well documented in Muslim individuals. The most common presentation is hyperpigmentation of the forehead, usually noted as a secondary finding in patients seeking treatment of unrelated symptoms.5 Cutaneous changes in this region correspond with the area of the forehead that rests on the carpet during prayer. Macules typically present on the upper central aspect of the forehead close to the hairline and/or in pairs above the medial ends of the eyebrows; sometimes 3 or 4 lesions may be present in this area with involvement of the nasion (Figure 1).6

In Saudi Arabia where Sunni Islam predominates, Muslim individuals observe prayer 5 times per day. Calluses have been observed in areas of the body that are frequently subject to friction during this practice.7 For instance, calluses are more prominent on the right knee (Figure 2) and the left ankle, which bear the individual’s weight during prayer, and typically become nodular over time (Figure 3). In Arabic, these calluses are referred to as zabiba.8

A notable finding in followers of Shia Islam, which predominates in Iran, is the development of small nodules on the forehead, possibly caused by rubbing the forehead on a flat disclike prayer stone called a mohr during daily prayer,9 which is said to enhance public esteem.10 The nodules generally are asymptomatic, but some individuals experience minimal pain on pressure.8 Ulceration of the nodules has rarely been observed.7

Limited access to thick and soft carpets and rarely bony exostoses or obesity are factors associated with prayer that can lead to skin changes (known as prayer signs), as they render the skin sensitive to pressure. Localized alopecia may occur on the forehead in individuals with low or pointed hairlines. An unexplained finding noted by one of the authors (K.A.) in some elderly Muslim individuals is that hair located on the forehead at the point of pressure during prayer remains pigmented, while the rest of the hair on the scalp turns white. Hyperpigmentation of the knuckles may be seen in individuals who use closed fists to rise from the ground following prayer. Except for mild hyperpigmentation of the knees,7 Muslim women rarely develop these changes, as they either do not pray,10 particularly during menstruation or puerperium, or they have more subcutaneous fat for protection.7 Some Muslim individuals who pray regularly at home may be conscious of these skin changes and therefore use a soft pillow to rest the forehead during prayer.

The histopathologic findings of prayer signs depend on the extent of lichenification and typically show compact hyperkeratosis or orthokeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, and mild dermal inflammation.8 Increased dermal vascularization and papillary fibrosis unlike that seen in lichen simplex chronicus have been described from skin changes in the lower limbs due to prayer practices.7 Additional findings in forehead biopsies include multiple comedones and epidermoid cysts in elderly patients showing a foreign body granulomatous reaction to hair fragments.10 Deposition of mucinous material in the dermal collagen in a prayer nodule on the forehead has been described in a Shiite individual, possibly due to repetitive microtrauma from the use of a prayer stone.9 Infections developed from sharing communal facilities or performing ritual sacrifices (eg, tinea,11 orf12) are prevalent during the yearly Hajj pilgrimage at Makkah, Saudi Arabia, in addition to other infectious and noninfectious dermatoses.13 Muslim women wearing headscarves secured at the neck with a safety pin have developed vitiligo at that site due to friction.14 Occasionally, Muslim individuals may apply perfumes before prayers, which may cause allergic contact dermatitis.

Judaism

Hyperpigmentation has been described in Jewish men at Talmudic seminaries due to the practice of reciting scriptures, which involves a rocking motion known as daven that leads to friction on the back.15 Lesions associated with this practice typically appear as isolated macules or a continuous linear patch over the skin of the bony protuberances of the inferior thoracic and lumbar vertebrae. Allergic contact dermatitis has been reported in Jewish individuals due to exposure to a variety of agents during religious practices, such as potassium dichromate, which is present in the leather used to make phylacteries or tefillin (boxes containing scripture that are secured to the forehead with straps that are then tied to the left arm during prayer). This finding has been noted in some or all areas of contact including the forehead, scalp, neck, left wrist, and waist.16

It is customary for both Orthodox Jewish and Muslim women to be concealed by clothing, which predisposes them to vitamin D deficiency17,18 but also protects them from developing malignant melanoma.19 Neonates have developed genital herpetic infections following circumcision due to the ancient practice of having the mohel (the person who performs the Jewish circumcision) suck on the wound until the bleeding stops.20

Hinduism

Hinduism espouses an eclectic philosophy of life subsuming numerous beliefs involving guardian deities, invoked by sacred marks, symbols, and rituals. Marks generally are placed on the forehead or other specified sites on the body. Sandalwood paste as well as vibhuti and kumkum powders most commonly are used, which can cause allergic contact dermatitis. Vibhuti is holy ash prepared by burning balls of dried cow dung in a fire pit with rice husk and clarified butter. Kumkum is prepared by alkalinizing turmeric powder, which turns red in color. A case of contact allergic dermatitis was reported in a Hindu priest who regularly used sandalwood paste on the forehead and as a balm for an ailment of the hands and feet.21 In our experience, vibhuti also has caused dermatitis on the forehead as well as on the neck and arms. The main difference between the 2 eruptions is that sandalwood dermatitis generally is localized to the center of the forehead as a circular or vertical mark or often in the center of the left palm, which is used to mix sandalwood powder with water to make a paste (Figure 4), while vibhuti contact dermatitis typically presents as a broad horizontal patch on the forehead because the powder is smeared with the middle 3 fingers (Figure 5). Perfumes used by some Muslim individuals before prayer that are applied on the clothes can mimic this type of contact dermatitis, but eruptions typically are confined to the fingers and palms.22 Contact dermatitis caused by necklaces made with beads of the stem of the Ocimum sanctum (holy basil) plant and seeds of the evergreen tree Elaeocarpus ganitrus have been reported.23 Calluses are sometimes seen in individuals who meditate for long hours while sitting in a cross-legged position and usually occur on or uncommonly below the lateral malleolus of the right foot, similar to practitioners of yoga.24

Hemorrhaging and crusting below the lateral malleolus of the right foot have been reported in Buddhist monks due to sitting in a cross-legged position for prolonged periods of meditation.25 Hyperpigmentation of the knees, ankles, and interphalangeal joints of the feet has been seen after sitting in the traditional Japanese meditative position.26 Tattoos of Hindu gods are common, while tattoos are forbidden in Islam and Judaism. Attributes of prominent deities branded on the body may be seen. Discrete sarcoidlike nodules along the axillae and chest wall have been attributed to a Hindu ritual (kavadi) that is performed annually as a form of self-inflicted punishment for their sins in which devotees pierce the chest wall with spokes to form a base over a heavy cage in which offerings are carried, and skewers passed through the cheeks have resulted in similar nodules in the oral cavity.27,28 Consumption of cow’s urine during rituals may induce acute urticaria.29 Lichen planus of the trunk30 and leukoderma of the waist31 may be induced by köbnerization or contact allergy from wearing sacred threads, respectively.

Sikhism

Sikhism, a religion founded in the 15th century, epitomizes the high-water mark of the syncretism between Hinduism and Islam. Men must abstain from cutting their hair; pulling and knotting the hair to maintain a coiffure can cause traction alopecia in the submandibular region and the frontal and parietal areas of the scalp as well as ridging and furrowing of the scalp resembling cutis verticis gyrata. Fixer, a product used to keep the beard intact, can cause contact dermatitis. The tight broad band of cloth (known as a ribbon) that is worn around the head to keep hair intact beneath a turban may cause forehead lesions. Discoid lupus erythematosus–like lesions or painful chondrodermatitis of the pinnae due to pressure from wearing a starched turban have been observed, also called “turban ear” from prominence of both anthelices.32,33 A case of a Sikh man who developed oral sarcoidal lesions from body piercing has been reported.28

Conclusion

Knowledge of the religious practices of patients would help in recognizing puzzling and peculiar dermatoses. It may not be possible to eliminate the causes of these conditions, but methods to reduce their effects on the skin can be discussed with patients.

Acknowledgments—We are grateful to the valuable help rendered by Joginder Kumar, MD, New Delhi, India, and C. Indira, MD, Hyderabad, India.

Religious practices can lead to cutaneous changes, and awareness of these changes is of paramount importance in establishing the cause. We review the cutaneous changes related to religious practices, including the Semitic religions, Hinduism, and Sikhism (Table). The most widely followed Semitic religions are Christianity, Islam, and Judaism. Christianity and Islam collectively account for more than half of the world’s population.1

Christianity

Christian individuals are prone to blisters that develop below the knees due to repeated kneeling in prayer.2 A case of allergic contact dermatitis to a wooden cross made from Dalbergia nigra has been reported.3 Localized swelling with hypertrichosis due to muscular hypertrophy in the lower neck above the interscapular region has been described in well-built men who lift weights to bear pasos (floats with wooden sculptures) during Holy Week in Seville, Spain.4

Islam

Cutaneous signs of piety have been well documented in Muslim individuals. The most common presentation is hyperpigmentation of the forehead, usually noted as a secondary finding in patients seeking treatment of unrelated symptoms.5 Cutaneous changes in this region correspond with the area of the forehead that rests on the carpet during prayer. Macules typically present on the upper central aspect of the forehead close to the hairline and/or in pairs above the medial ends of the eyebrows; sometimes 3 or 4 lesions may be present in this area with involvement of the nasion (Figure 1).6

In Saudi Arabia where Sunni Islam predominates, Muslim individuals observe prayer 5 times per day. Calluses have been observed in areas of the body that are frequently subject to friction during this practice.7 For instance, calluses are more prominent on the right knee (Figure 2) and the left ankle, which bear the individual’s weight during prayer, and typically become nodular over time (Figure 3). In Arabic, these calluses are referred to as zabiba.8

A notable finding in followers of Shia Islam, which predominates in Iran, is the development of small nodules on the forehead, possibly caused by rubbing the forehead on a flat disclike prayer stone called a mohr during daily prayer,9 which is said to enhance public esteem.10 The nodules generally are asymptomatic, but some individuals experience minimal pain on pressure.8 Ulceration of the nodules has rarely been observed.7

Limited access to thick and soft carpets and rarely bony exostoses or obesity are factors associated with prayer that can lead to skin changes (known as prayer signs), as they render the skin sensitive to pressure. Localized alopecia may occur on the forehead in individuals with low or pointed hairlines. An unexplained finding noted by one of the authors (K.A.) in some elderly Muslim individuals is that hair located on the forehead at the point of pressure during prayer remains pigmented, while the rest of the hair on the scalp turns white. Hyperpigmentation of the knuckles may be seen in individuals who use closed fists to rise from the ground following prayer. Except for mild hyperpigmentation of the knees,7 Muslim women rarely develop these changes, as they either do not pray,10 particularly during menstruation or puerperium, or they have more subcutaneous fat for protection.7 Some Muslim individuals who pray regularly at home may be conscious of these skin changes and therefore use a soft pillow to rest the forehead during prayer.

The histopathologic findings of prayer signs depend on the extent of lichenification and typically show compact hyperkeratosis or orthokeratosis, hypergranulosis, acanthosis, and mild dermal inflammation.8 Increased dermal vascularization and papillary fibrosis unlike that seen in lichen simplex chronicus have been described from skin changes in the lower limbs due to prayer practices.7 Additional findings in forehead biopsies include multiple comedones and epidermoid cysts in elderly patients showing a foreign body granulomatous reaction to hair fragments.10 Deposition of mucinous material in the dermal collagen in a prayer nodule on the forehead has been described in a Shiite individual, possibly due to repetitive microtrauma from the use of a prayer stone.9 Infections developed from sharing communal facilities or performing ritual sacrifices (eg, tinea,11 orf12) are prevalent during the yearly Hajj pilgrimage at Makkah, Saudi Arabia, in addition to other infectious and noninfectious dermatoses.13 Muslim women wearing headscarves secured at the neck with a safety pin have developed vitiligo at that site due to friction.14 Occasionally, Muslim individuals may apply perfumes before prayers, which may cause allergic contact dermatitis.

Judaism

Hyperpigmentation has been described in Jewish men at Talmudic seminaries due to the practice of reciting scriptures, which involves a rocking motion known as daven that leads to friction on the back.15 Lesions associated with this practice typically appear as isolated macules or a continuous linear patch over the skin of the bony protuberances of the inferior thoracic and lumbar vertebrae. Allergic contact dermatitis has been reported in Jewish individuals due to exposure to a variety of agents during religious practices, such as potassium dichromate, which is present in the leather used to make phylacteries or tefillin (boxes containing scripture that are secured to the forehead with straps that are then tied to the left arm during prayer). This finding has been noted in some or all areas of contact including the forehead, scalp, neck, left wrist, and waist.16

It is customary for both Orthodox Jewish and Muslim women to be concealed by clothing, which predisposes them to vitamin D deficiency17,18 but also protects them from developing malignant melanoma.19 Neonates have developed genital herpetic infections following circumcision due to the ancient practice of having the mohel (the person who performs the Jewish circumcision) suck on the wound until the bleeding stops.20

Hinduism

Hinduism espouses an eclectic philosophy of life subsuming numerous beliefs involving guardian deities, invoked by sacred marks, symbols, and rituals. Marks generally are placed on the forehead or other specified sites on the body. Sandalwood paste as well as vibhuti and kumkum powders most commonly are used, which can cause allergic contact dermatitis. Vibhuti is holy ash prepared by burning balls of dried cow dung in a fire pit with rice husk and clarified butter. Kumkum is prepared by alkalinizing turmeric powder, which turns red in color. A case of contact allergic dermatitis was reported in a Hindu priest who regularly used sandalwood paste on the forehead and as a balm for an ailment of the hands and feet.21 In our experience, vibhuti also has caused dermatitis on the forehead as well as on the neck and arms. The main difference between the 2 eruptions is that sandalwood dermatitis generally is localized to the center of the forehead as a circular or vertical mark or often in the center of the left palm, which is used to mix sandalwood powder with water to make a paste (Figure 4), while vibhuti contact dermatitis typically presents as a broad horizontal patch on the forehead because the powder is smeared with the middle 3 fingers (Figure 5). Perfumes used by some Muslim individuals before prayer that are applied on the clothes can mimic this type of contact dermatitis, but eruptions typically are confined to the fingers and palms.22 Contact dermatitis caused by necklaces made with beads of the stem of the Ocimum sanctum (holy basil) plant and seeds of the evergreen tree Elaeocarpus ganitrus have been reported.23 Calluses are sometimes seen in individuals who meditate for long hours while sitting in a cross-legged position and usually occur on or uncommonly below the lateral malleolus of the right foot, similar to practitioners of yoga.24

Hemorrhaging and crusting below the lateral malleolus of the right foot have been reported in Buddhist monks due to sitting in a cross-legged position for prolonged periods of meditation.25 Hyperpigmentation of the knees, ankles, and interphalangeal joints of the feet has been seen after sitting in the traditional Japanese meditative position.26 Tattoos of Hindu gods are common, while tattoos are forbidden in Islam and Judaism. Attributes of prominent deities branded on the body may be seen. Discrete sarcoidlike nodules along the axillae and chest wall have been attributed to a Hindu ritual (kavadi) that is performed annually as a form of self-inflicted punishment for their sins in which devotees pierce the chest wall with spokes to form a base over a heavy cage in which offerings are carried, and skewers passed through the cheeks have resulted in similar nodules in the oral cavity.27,28 Consumption of cow’s urine during rituals may induce acute urticaria.29 Lichen planus of the trunk30 and leukoderma of the waist31 may be induced by köbnerization or contact allergy from wearing sacred threads, respectively.

Sikhism

Sikhism, a religion founded in the 15th century, epitomizes the high-water mark of the syncretism between Hinduism and Islam. Men must abstain from cutting their hair; pulling and knotting the hair to maintain a coiffure can cause traction alopecia in the submandibular region and the frontal and parietal areas of the scalp as well as ridging and furrowing of the scalp resembling cutis verticis gyrata. Fixer, a product used to keep the beard intact, can cause contact dermatitis. The tight broad band of cloth (known as a ribbon) that is worn around the head to keep hair intact beneath a turban may cause forehead lesions. Discoid lupus erythematosus–like lesions or painful chondrodermatitis of the pinnae due to pressure from wearing a starched turban have been observed, also called “turban ear” from prominence of both anthelices.32,33 A case of a Sikh man who developed oral sarcoidal lesions from body piercing has been reported.28

Conclusion

Knowledge of the religious practices of patients would help in recognizing puzzling and peculiar dermatoses. It may not be possible to eliminate the causes of these conditions, but methods to reduce their effects on the skin can be discussed with patients.

Acknowledgments—We are grateful to the valuable help rendered by Joginder Kumar, MD, New Delhi, India, and C. Indira, MD, Hyderabad, India.

- The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. The Global Religious Landscape: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World’s Major Religious Groups as of 2010. Washington, DC: The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, The Pew Research Center; 2012.

- Goodheart HP. “Devotional dermatoses”: a new nosologic entity? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:543.

- Fisher AA, Bikowski J. Allergic dermatitis due to a wooden cross made of Dalbergia nigra. Contact Dermatitis. 1981;7:45-46.

- Camacho F. Acquired circumscribed hypertrichosis in the ‘costaleros’ who bear the ‘pasos’ during Holy Week in Seville, Spain. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:361-363.

- Mishriki YY. Skin commotion from repetitive devotion. prayer callus. Postgrad Med. 1999;105:153-154.

- Barankin B. Prayer marks. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:985-986.

- Abanmi AA, Al Zouman AY, Al Hussaini H, et al. Prayer marks. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:411-414.

- Kahana M, Cohen M, Ronnen M, et al. Prayer nodules in Moslem men. Cutis. 1986;38:281-282.

- O’Goshi KI, Aoyama H, Tagami H. Mucin deposition in a prayer nodule on the forehead. Dermatology. 1998;196:364.

- Vollum DI, Azadeh B. Prayer nodules. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1979;4:39-47.

- Arrese JE, Piérard-Franchimont C, Piérard GE. Scytalidium dimidiatum melanonychia and scaly plantar skin in four patients from the Maghreb: imported disease or outbreak in a Belgian mosque? Dermatology. 2001;202:183-185.

- Malik M, Bharier M, Tahan S, et al. Orf acquired during religious observance. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:606-608.

- Mimesh SA, Al-Khenaizan S, Memish ZA. Dermatologic challenge of pilgrimage. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:52-61.

- El-Din Anbar T, Abdel-Rahman AT, El-Khayyat MA, et al. Vitiligo on anterior aspect of neck in Muslim females: case series. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:178-179.

- Naimer SA, Trattner A, Biton A, et al. Davener’s dermatosis: a variant of friction hypermelanosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:442-445.

- Feit NE, Weinberg JM, DeLeo VA. Cutaneous disease and religious practice: case of allergic contact dermatitis to tefillin and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:886-888.

- Mukamel MN, Weisman Y, Somech R, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency in Orthodox and non-Orthodox Jewish mothers in Israel. Isr Med Assoc J. 2001;3:419-421.

- Hatun S, Islam O, Cizmecioglu F, et al. Subclinical vitamin D deficiency is increased in adolescent girls who wear concealing clothing. J Nutr. 2005;135:218-222.

- Vardi G, Modan B, Golan R, et al. Orthodox Jews have a lower incidence of malignant melanoma. a note on the potentially protective role of traditional clothing. Int J Cancer. 1993;53:771-773.

- Gesundheit B, Grisaru-Soen G, Greenberg G, et al. Neonatal genital herpes virus type 1 infection after Jewish ritual circumcision: modern medicine and religious tradition. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e259-e263.

- Pasricha JS, Ramam M. Contact dermatitis due to sandalwood (Santalum album Linn). Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1986;52:232-233.

- Carmichael AJ, Foulds IS. Sensitization as a result of a religious ritual. Br J Dermatol. 1990;123:846.

- Bajaj AK, Saraswat A. Contact dermatitis. In: Valia RG, Valia AR, eds. Textbook of Dermatology. 3rd ed. Mumbai, India: Bhalani Publishing House; 2008:545-549.

- Verma SB, Wollina U. Callosities of cross-legged sitting: “yoga sign”—an under-recognized cultural cutaneous presentation. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:1212-1214.

- Rehman H, Asfour NA. Clinical images: prayer nodules [published online ahead of print November 16, 2009]. CMAJ. 2010;182:e19.

- Ruhnke WG, Serizawa Y. Viral pericarditis. BMJ. 2010;340:b5579.

- Nayar M. Sarcoidosis on ritual scarification. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:116-118.

- Ng KH, Siar CH, Ganesapillai T. Sarcoid-like foreign body reaction in body piercing: a report of two cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Radiol Endod. 1997;84:28-31.

- Bhalla M, Thami GP. Acute urticaria following ‘gomutra’ (cow’s urine) gargles. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:722-723.

- Joshi A, Agarwalla A, Agrawal S, et al. Köbner phenomenon due to sacred thread in lichen planus. J Dermatol. 2000;27:129-130.

- Banerjee K, Banerjee R, Mandal B. Amulet string contact leukoderma and its differentiation from vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:180-181.

- Kanwar AJ, Kaur S. Some dermatoses peculiar to Sikh men. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:739-740.

- Williams HC. Turban ear. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:117-119.

- The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life. The Global Religious Landscape: A Report on the Size and Distribution of the World’s Major Religious Groups as of 2010. Washington, DC: The Pew Forum on Religion & Public Life, The Pew Research Center; 2012.

- Goodheart HP. “Devotional dermatoses”: a new nosologic entity? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44:543.

- Fisher AA, Bikowski J. Allergic dermatitis due to a wooden cross made of Dalbergia nigra. Contact Dermatitis. 1981;7:45-46.

- Camacho F. Acquired circumscribed hypertrichosis in the ‘costaleros’ who bear the ‘pasos’ during Holy Week in Seville, Spain. Arch Dermatol. 1995;131:361-363.

- Mishriki YY. Skin commotion from repetitive devotion. prayer callus. Postgrad Med. 1999;105:153-154.

- Barankin B. Prayer marks. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:985-986.

- Abanmi AA, Al Zouman AY, Al Hussaini H, et al. Prayer marks. Int J Dermatol. 2002;41:411-414.

- Kahana M, Cohen M, Ronnen M, et al. Prayer nodules in Moslem men. Cutis. 1986;38:281-282.

- O’Goshi KI, Aoyama H, Tagami H. Mucin deposition in a prayer nodule on the forehead. Dermatology. 1998;196:364.

- Vollum DI, Azadeh B. Prayer nodules. Clin Exp Dermatol. 1979;4:39-47.

- Arrese JE, Piérard-Franchimont C, Piérard GE. Scytalidium dimidiatum melanonychia and scaly plantar skin in four patients from the Maghreb: imported disease or outbreak in a Belgian mosque? Dermatology. 2001;202:183-185.

- Malik M, Bharier M, Tahan S, et al. Orf acquired during religious observance. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:606-608.

- Mimesh SA, Al-Khenaizan S, Memish ZA. Dermatologic challenge of pilgrimage. Clin Dermatol. 2008;26:52-61.

- El-Din Anbar T, Abdel-Rahman AT, El-Khayyat MA, et al. Vitiligo on anterior aspect of neck in Muslim females: case series. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:178-179.

- Naimer SA, Trattner A, Biton A, et al. Davener’s dermatosis: a variant of friction hypermelanosis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:442-445.

- Feit NE, Weinberg JM, DeLeo VA. Cutaneous disease and religious practice: case of allergic contact dermatitis to tefillin and review of the literature. Int J Dermatol. 2004;43:886-888.

- Mukamel MN, Weisman Y, Somech R, et al. Vitamin D deficiency and insufficiency in Orthodox and non-Orthodox Jewish mothers in Israel. Isr Med Assoc J. 2001;3:419-421.

- Hatun S, Islam O, Cizmecioglu F, et al. Subclinical vitamin D deficiency is increased in adolescent girls who wear concealing clothing. J Nutr. 2005;135:218-222.

- Vardi G, Modan B, Golan R, et al. Orthodox Jews have a lower incidence of malignant melanoma. a note on the potentially protective role of traditional clothing. Int J Cancer. 1993;53:771-773.

- Gesundheit B, Grisaru-Soen G, Greenberg G, et al. Neonatal genital herpes virus type 1 infection after Jewish ritual circumcision: modern medicine and religious tradition. Pediatrics. 2004;114:e259-e263.

- Pasricha JS, Ramam M. Contact dermatitis due to sandalwood (Santalum album Linn). Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 1986;52:232-233.

- Carmichael AJ, Foulds IS. Sensitization as a result of a religious ritual. Br J Dermatol. 1990;123:846.

- Bajaj AK, Saraswat A. Contact dermatitis. In: Valia RG, Valia AR, eds. Textbook of Dermatology. 3rd ed. Mumbai, India: Bhalani Publishing House; 2008:545-549.

- Verma SB, Wollina U. Callosities of cross-legged sitting: “yoga sign”—an under-recognized cultural cutaneous presentation. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:1212-1214.

- Rehman H, Asfour NA. Clinical images: prayer nodules [published online ahead of print November 16, 2009]. CMAJ. 2010;182:e19.

- Ruhnke WG, Serizawa Y. Viral pericarditis. BMJ. 2010;340:b5579.

- Nayar M. Sarcoidosis on ritual scarification. Int J Dermatol. 1993;32:116-118.

- Ng KH, Siar CH, Ganesapillai T. Sarcoid-like foreign body reaction in body piercing: a report of two cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Radiol Endod. 1997;84:28-31.

- Bhalla M, Thami GP. Acute urticaria following ‘gomutra’ (cow’s urine) gargles. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2005;30:722-723.

- Joshi A, Agarwalla A, Agrawal S, et al. Köbner phenomenon due to sacred thread in lichen planus. J Dermatol. 2000;27:129-130.

- Banerjee K, Banerjee R, Mandal B. Amulet string contact leukoderma and its differentiation from vitiligo. Indian J Dermatol Venereol Leprol. 2004;70:180-181.

- Kanwar AJ, Kaur S. Some dermatoses peculiar to Sikh men. Int J Dermatol. 1990;29:739-740.

- Williams HC. Turban ear. Arch Dermatol. 1994;130:117-119.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous changes may be seen in specified areas of the skin following regular worship in almost all major religions of the world.

- Cutaneous lesions are most commonly associated with friction from praying, along with contact allergic dermatitis from products and substances commonly used in worshipping and granulomas due to practices such as tattoos and skin piercing.

- Uncommon skin manifestations include urticaria and leukoderma.

- Some religious practices may render individuals prone to infections that manifest on the skin.