User login

Off-label medications for addictive disorders

Off-label prescribing (OLP) refers to the practice of using medications for indications outside of those approved by the FDA, or in dosages, dose forms, or patient populations that have not been approved by the FDA.1 OLP is common, occurring in many practice settings and nearly every medical specialty. In a 2006 review, Radley et al2 found OLP accounted for 21% of the overall use of 160 common medications. The frequency of OLP varies between medication classes. Off-label use of anticonvulsants, antidepressants, and antipsychotics tends to be higher than that of other medications.3,4 OLP is often more common

Box

Several aspects contribute to off-label prescribing (OLP). First, there is little financial incentive for pharmaceutical companies to seek new FDA indications for existing medications. In addition, there are no FDA-approved medications for many disorders included in DSM-5, and treatment of these conditions relies almost exclusively on the practice of OLP. Finally, patients enrolled in clinical trials must often meet stringent exclusion criteria, such as the lack of comorbid substance use disorders. For these reasons, using off-label medications to treat substance-related and addictive disorders is particularly necessary.

Several important medicolegal and ethical considerations surround OLP. The FDA prohibits off-label promotion, in which manufacturers advertise the use of a medication for off-label use.5 However, regulations allow physicians to use their best clinical judgment when prescribing medications for off-label use. When considering off-label use of any medication, physicians should review the most up-to-date research, including clinical trials, case reports, and reviews to safely support their decision-making. OLP should be guided by ethical principles such as autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice. Physicians should obtain informed consent by conducting an appropriate discussion of the risks, benefits, and alternatives of off-label medications. This conversation should be clearly documented, and physicians should provide written material regarding off-label options to patients when available. Finally, physicians should verify their patients’ understanding of this discussion, and allow patients to accept or decline off-label medications without pressure.

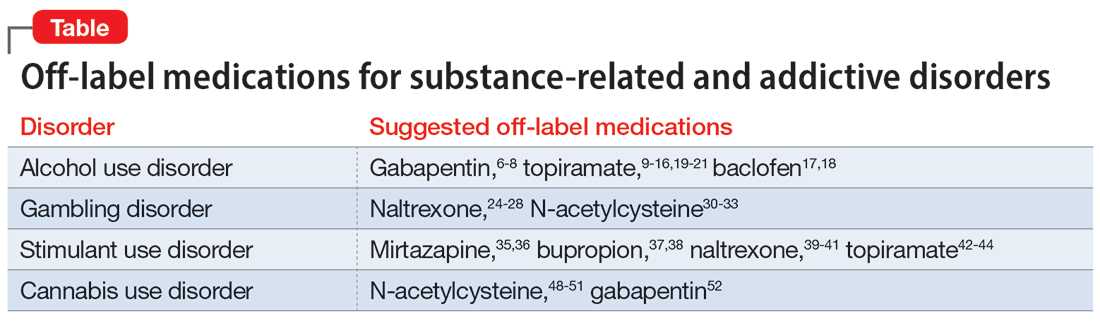

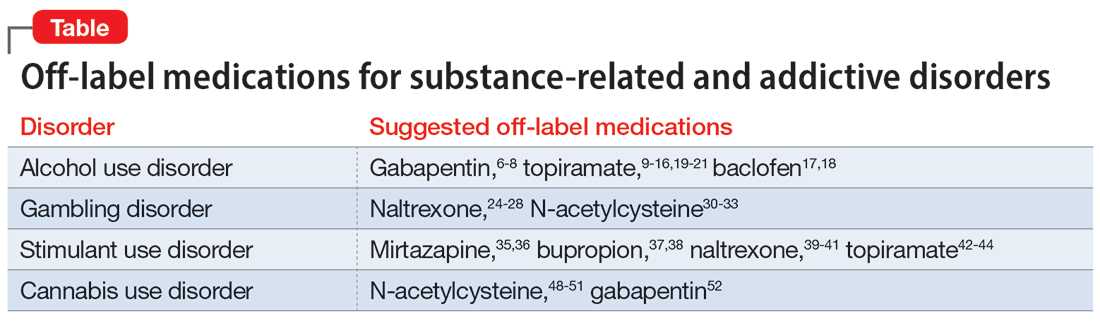

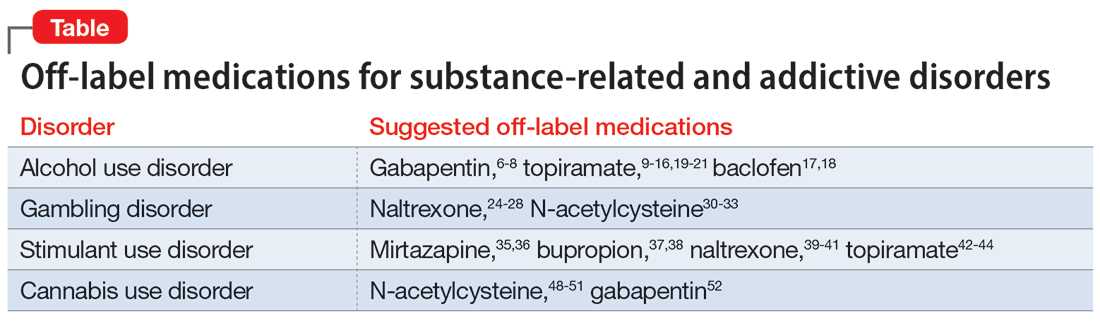

This article focuses on current and potential future medications available for OLP to treat patients with alcohol use disorder (AUD), gambling disorder (GD), stimulant use disorder, and cannabis use disorder.

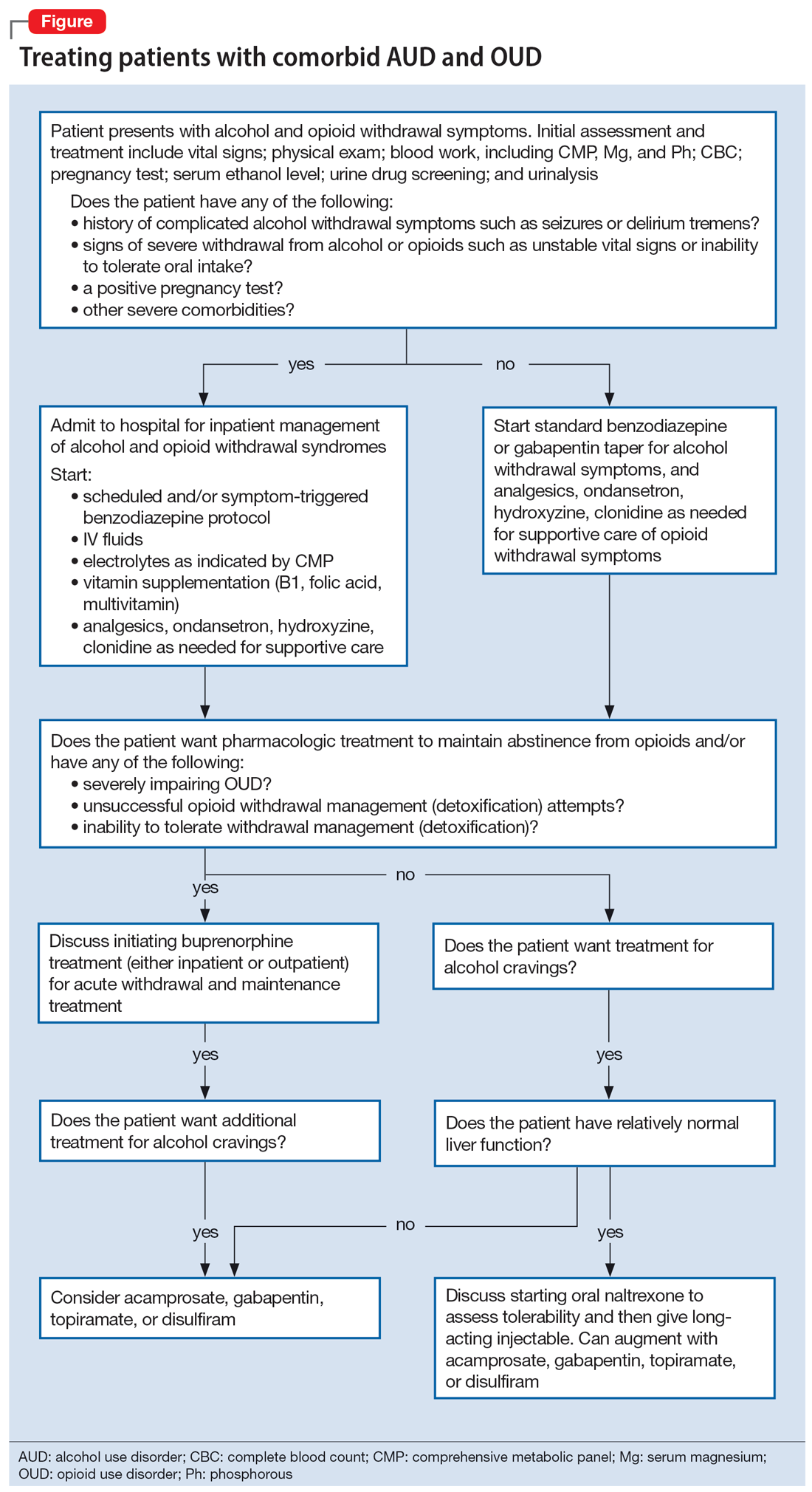

Alcohol use disorder

CASE 1

Ms. X, age 67, has a history of severe AUD, mild renal impairment, and migraines. She presents to the outpatient clinic seeking help to drink less alcohol. Ms. X reports drinking 1 to 2 bottles of wine each day. She was previously treated for AUD but was not helped by naltrexone and did not tolerate disulfiram (abstinence was not her goal and she experienced significant adverse effects). Ms. X says she has a medical history of chronic migraines but denies other medical issues. The treatment team discusses alternative pharmacologic options, including acamprosate and topiramate. After outlining the dosing schedule and risks/benefits with Ms. X, you make the joint decision to start topiramate to reduce alcohol cravings and target her migraine symptoms.

Only 3 medications are FDA-approved for treating AUD: disulfiram, naltrexone (oral and injectable formulations), and acamprosate. Off-label options for AUD treatment include gabapentin, topiramate, and baclofen.

Gabapentin is FDA-approved for treating postherpetic neuralgia and partial seizures in patients age ≥3. The exact mechanism of action is unclear, though its effects are possibly related to its activity as a calcium channel ligand. It also carries a structural resemblance to gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), though it lacks activity at GABA receptors.

Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the efficacy of gabapentin for AUD produced promising results. In a comparison of gabapentin vs placebo for AUD, Anton et al6 found gabapentin led to significant increases in the number of participants with total alcohol abstinence and participants who reported reduced drinking. Notably, the effect was most prominent in those with heavy drinking patterns and pretreatment alcohol withdrawal symptoms. A total of 41% of participants with high alcohol withdrawal scores on pretreatment evaluation achieved total abstinence while taking gabapentin, compared to 1% in the placebo group.6 A meta-analysis of gabapentin for AUD by Kranzler et al7 included 7 RCTs and 32 effect measures. It found that although all outcome measures favored gabapentin over placebo, only the percentage of heavy drinking days was significantly different.

Gabapentin is dosed between 300 to 600 mg 3 times per day, but 1 study found that a higher dose (1,800 mg/d) was associated with better outcomes.8 Common adverse effects include sedation, dizziness, peripheral edema, and ataxia.

Continue to: Topiramate

Topiramate blocks voltage-gated sodium channels and enhances GABA-A receptor activity.9 It is indicated for the treatment of seizures, migraine prophylaxis, weight management, and weight loss. Several clinical trials, including RCTs,10-12 demonstrated that topiramate was superior to placebo in reducing the percentage of heavy drinking days and overall drinking days. Some also showed that topiramate was associated with abstinence and reduced craving levels.12,13 A meta-analysis by Blodgett et al14 found that compared to placebo, topiramate lowered the rate of heavy drinking and increased abstinence.

Topiramate is dosed from 50 to 150 mg twice daily, although some studies suggest a lower dose (≤75 mg/d) may be associated with clinical benefits.15,16 One important clinical consideration: topiramate must follow a slow titration schedule (4 to 6 weeks) to increase tolerability and avoid adverse effects. Common adverse effects include sedation, word-finding difficulty, paresthesia, increased risk for renal calculi, dizziness, anorexia, and alterations in taste.

Baclofen is a GABA-B agonist FDA-approved for the treatment of muscle spasticity related to multiple sclerosis and reversible spasticity related to spinal cord lesions and multiple sclerosis. Of note, it is approved for treatment of AUD in Europe.

In a meta-analysis of 13 RCTs, Pierce et al17 found a greater likelihood of abstinence and greater time to first lapse of drinking with baclofen compared to placebo. Interestingly, a subgroup analysis found that the positive effects were limited to trials that used 30 to 60 mg/d of baclofen, and not evident in those that used higher doses. Additionally, there was no difference between baclofen and placebo with regard to several important outcomes, including alcohol cravings, anxiety, depression, or number of total abstinent days. A review by Andrade18 proposed that individualized treatment with high-dose baclofen (30 to 300 mg/d) may be a useful second-line approach in heavy drinkers who wish to reduce their alcohol intake.

Continue to: Before starting baclofen...

Before starting baclofen, patients should be informed about its adverse effects. Common adverse effects include sedation and motor impairment. More serious but less common adverse effects include seizures, respiratory depression with sleep apnea, severe mood disorders (ie, mania, depression, or suicide risk), and mental confusion. Baclofen should be gradually discontinued, because there is some risk of clinical withdrawal symptoms (ie, agitation, confusion, seizures, or delirium).

Among the medications discussed in this section, the evidence for gabapentin and topiramate is moderate to strong, while the evidence for baclofen is overall weaker or mixed. The American Psychiatric Association’s Practice Guideline suggests offering gabapentin or topiramate to patients with moderate to severe AUD whose goal is to achieve abstinence or reduce alcohol use, or those who prefer gabapentin or topiramate or cannot tolerate or have not responded to naltrexone and acamprosate.19 Clinicians must ensure patients have no contraindications to the use of these medications. Due to the moderate quality evidence for a significant reduction in heavy drinking and increased abstinence,14,20 a practice guideline from the US Department of Veterans Affairs and US Department of Defense21 recommends topiramate as 1 of 2 first-line treatments (the other is naltrexone). This guideline suggests gabapentin as a second-line treatment for AUD.21

Gambling disorder

CASE 2

Mr. P, age 28, seeks treatment for GD and cocaine use disorder. He reports a 7-year history of sports betting that has increasingly impaired his functioning over the past year. He lost his job, savings, and familial relationships due to his impulsive and risky behavior. Mr. P also reports frequent cocaine use, about 2 to 3 days per week, mostly on the weekends. The psychiatrist tells Mr. P there is no FDA-approved pharmacologic treatment for GD or cocaine use disorder. The psychiatrist discusses the option of naltrexone as off-label treatment for GD with the goal of reducing Mr. P’s urges to gamble, and points to possible benefits for cocaine use disorder.

GD impacts approximately 0.5% of the adult US population and is often co-occurring with substance use disorders.22 It is thought to share neurobiological and clinical similarities with substance use disorders.23 There are currently no FDA-approved medications to treat the disorder. In studies of GD, treatment success with antidepressants and mood stabilizers has not been consistent,23,24 but some promising results have been published for the opioid receptor antagonist naltrexone24-29 and N-acetylcysteine (NAC).30-32

Naltrexone is thought to reduce gambling behavior and urges via downstream modulation of mesolimbic dopamine circuitry.24 It is FDA-approved for the treatment of AUD and opioid use disorder. Open-label RCTs have found a reduction in gambling urges and behavior with daily naltrexone.25-27 Dosing at 50 mg/d appears to be just as efficacious as higher doses such as 100 and 150 mg/d.27 When used as a daily as-needed medication for strong gambling urges or if an individual was planning to gamble, naltrexone 50 mg/d was not effective.28

Continue to: Naltrexone typically is started...

Naltrexone typically is started at 25 mg/d to assess tolerability and quickly titrated to 50 mg/d. When titrating, common adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, and transient elevations in transaminases. Another opioid antagonist, nalmefene, has also been studied in patients with GD. An RCT by Grant et al29 that evaluated 207 patients found that compared with placebo, nalmefene 25 mg/d for 16 weeks was associated with a significant reduction in gambling assessment scores. In Europe, nalmefene is approved for treating AUD but the oral formulation is not currently available in the US.

N-acetylcysteine is thought to potentially reverse neuronal dysfunction seen in addictive disorders by glutamatergic modulation.30 Research investigating NAC for GD is scarce. A pilot study found 16 of 27 patients with GD reduced gambling behavior with a mean dose of 1,476.9 mg/d.31 An additional study investigating the addition of NAC to behavioral therapy in nicotine-dependent individuals with pathologic gambling found a reduction in problem gambling after 18 weeks (6 weeks + 3 months follow-up).32 Common but mild adverse effects associated with NAC are nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

A meta-analysis by Goslar et al33 that reviewed 34 studies (1,340 participants) found pharmacologic treatments were associated with large and medium pre-post reductions in global severity, frequency, and financial loss in patients with GD. RCTs studying opioid antagonists and mood stabilizers (combined with a cognitive intervention) as well as lithium for patients with comorbid bipolar disorder and GD demonstrated promising results.33

Stimulant use disorder

There are no FDA-approved medications for stimulant use disorder. Multiple off-label options have been studied for the treatment of methamphetamine abuse and cocaine abuse.

Methamphetamine use has been expanding over the past decade with a 3.6-fold increase in positive methamphetamine screens in overdose deaths from 2011 to 2016.34 Pharmacologic options studied for OLP of methamphetamine use disorder include mirtazapine, bupropion, naltrexone, and topiramate.

Continue to: Mirtazapine

Mirtazapine is an atypical antidepressant whose mechanism of action includes modulation of the serotonin, norepinephrine, and alpha-2 adrenergic systems. It is FDA-approved for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). In a randomized placebo-controlled study, mirtazapine 30 mg/d at night was found to decrease methamphetamine use for active users and led to decreased sexual risk in men who have sex with men.35 These results were supported by an additional RCT in which mirtazapine 30 mg/d significantly reduced rates of methamphetamine use vs placebo at 24 and 36 weeks despite poor medication adherence.36 Adverse effects to monitor in patients treated with mirtazapine include increased appetite, weight gain, sedation, and constipation.

Bupropion is a norepinephrine dopamine reuptake inhibitor that produces increased neurotransmission of norepinephrine and dopamine in the CNS. It is FDA-approved for the treatment of MDD and as an aid for smoking cessation. Bupropion has been studied for methamphetamine use disorder with mixed results. In a randomized placebo-controlled trial, bupropion sustained release 15

Naltrexone. Data about using oral naltrexone to treat stimulant use disorders are limited. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial by Jayaram-Lindström et al39 found naltrexone 50 mg/d significantly reduced amphetamine use compared to placebo. Additionally, naltrexone 50 and 150 mg/d have been shown to reduce cocaine use over time in combination with therapy for cocaine-dependent patients and those dependent on alcohol and cocaine.40,41

Topiramate has been studied for the treatment of cocaine use disorder. It is hypothesized that modulation of the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system may contribute to decreased cocaine cravings.42 A pilot study by Kampman et al43 found that after an 8-week titration of topiramate to 200 mg/d, individuals were more likely to achieve cocaine abstinence compared to those who receive placebo. In an RCT, Elkashef et al44 did not find topiramate assisted with increased abstinence of methamphetamine in active users at a target dose of 200 mg/d. However, it was associated with reduced relapse rates in individuals who were abstinent prior to the study.44 At a target dose of 300 mg/d, topiramate also outperformed placebo in decreasing days of cocaine use.42 Adverse effects of topiramate included paresthesia, alteration in taste, and difficulty with concentration.

Cannabis use disorder

In recent years, cannabis use in the US has greatly increased45 but no medications are FDA-approved for treating cannabis use disorder. Studies of pharmacologic options for cannabis use disorder have had mixed results.46 A meta-analysis by Bahji et al47 of 24 studies investigating pharmacotherapies for cannabis use disorder highlighted the lack of adequate evidence. In this section, we focus on a few positive trials of NAC and gabapentin.

Continue to: N-acetylcysteine

N-acetylcysteine. Studies investigating NAC 1,200 mg twice daily have been promising in adolescent and adult populations.48-50 There are some mixed results, however. A large RCT found NAC 1,200 mg twice daily was not better than placebo in helping adults achieve abstinence from cannabis.51

Gabapentin may be a viable option for treating cannabis use disorder. A pilot study by Mason et al52 found gabapentin 1,200 mg/d was more effective than placebo at reducing cannabis use among treatment-seeking adults.

When and how to consider OLP

OLP for addictive disorders is common and often necessary. This is primarily due to limitations of the FDA-approved medications and because there are no FDA-approved medications for many substance-related and addictive disorders (ie, GD, cannabis use disorder, and stimulant use disorder). When assessing pharmacotherapy options, if FDA-approved medications are available for certain diagnoses, clinicians should first consider them. The off-label medications discussed in this article are outlined in the Table.6-21,24-28,30-33,35-44,48-52

The overall level of evidence to support the use of off-label medications is lower than that of FDA-approved medications, which contributes to potential medicolegal concerns of OLP. Off-label medications should be considered when there are no FDA-approved medications available, and the decision to use off-label medications should be based on evidence from the literature and current standard of care. Additionally, OLP is necessary if a patient cannot tolerate FDA-approved medications, is not helped by FDA-approved treatments, or when there are other clinical reasons to choose a particular off-label medication. For example, if a patient has comorbid AUD and obesity (or migraines), using topiramate may be appropriate because it may target alcohol cravings and can be helpful for weight loss (and migraine prophylaxis). Similarly, for patients with AUD and neuropathic pain, using gabapentin can be considered for its dual therapeutic effects.

It is critical for clinicians to understand the landscape of off-label options for treating addictive disorders. Additional research in the form of RCTs is needed to better clarify the efficacy and adverse effects of these treatments.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Off-label prescribing is prevalent in practice, including in the treatment of substance-related and addictive disorders. When considering off-label use of any medication, clinicians should review the most recent research, obtain informed consent from patients, and verify patients’ understanding of the potential risks and adverse effects associated with the particular medication.

Related Resources

- Joshi KG, Frierson RL. Off-label prescribing: how to limit your liability. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(9):12,39. doi:10.12788/ cp.0035

- Stanciu CN, Gnanasegaram SA. Don’t balk at using medical therapy to manage alcohol use disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(2):50-52.

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Baclofen • Ozobax

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Disulfiram • Antabuse

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Naltrexone • ReVia, Vivitrol

Topiramate • Topamax

1. Wittich CM, Burkle CM, Lanier WL. Ten common questions (and their answers) about off-label drug use. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(10):982-990. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.04.017

2. Radley DC, Finkelstein SN, Stafford RS. Off-label prescribing among office-based physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):1021-1026. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.9.1021

3. Wang J, Jiang F, Yating Y, et al. Off-label use of antipsychotic medications in psychiatric inpatients in China: a national real-world survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):375. doi:10.1186/s12888-021-03374-0

4. Chen H, Reeves JH, Fincham JE, et al. Off-label use of antidepressant, anticonvulsant, and antipsychotic medications among Georgia Medicaid enrollees in 2001. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(6):972-982. doi:10.4088/jcp.v67n0615

5. Ventola CL. Off-label drug information: regulation, distribution, evaluation, and related controversies. P T. 2009;34(8):428-440.

6. Anton RF, Latham P, Voronin K, et al. Efficacy of gabapentin for the treatment of alcohol use disorder in patients with alcohol withdrawal symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(5):728-736. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0249

7. Kranzler HR, Feinn R, Morris P, et al. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of gabapentin for treating alcohol use disorder. Addiction. 2019;114(9):1547-1555. doi:10.1111/add.14655

8. Mason BJ, Quello S, Goodell V. Gabapentin treatment for alcohol dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):70-77. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.11950

9. Fariba KA. Saadabadi A. Topiramate. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2023. Accessed December 22, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554530/

10. Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Bowden CL, et al. Oral topiramate for treatment of alcohol dependence: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9370):1677-1685. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13370-3

11. Johnson BA, Rosenthal N, Capece JA, et al. Topiramate for treating alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298(14):1641-1651. doi:10.1001/jama.298.14.1641

12. Knapp CM, Ciraulo DA, Sarid-Segal O, et al. Zonisamide, topiramate, and levetiracetam: efficacy and neuropsychological effects in alcohol use disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35(1):34-42. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000000246

13. Kranzler HR, Covault J, Feinn R, et al. Topiramate treatment for heavy drinkers: moderation by a GRIK1 polymorphism. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(4):445-452. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13081014

14. Blodgett JC, Del Re AC, Maisel NC, et al. A meta-analysis of topiramate’s effects for individuals with alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(6):1481-1488. doi:10.1111/acer.12411

15. Paparrigopoulos T, Tzavellas E, Karaiskos D, et al. Treatment of alcohol dependence with low-dose topiramate: an open-label controlled study. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:41. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-11-41

16. Tang YL, Hao W, Leggio L. Treatments for alcohol-related disorders in China: a developing story. Alcohol Alcohol. 2012;47(5):563-570. doi:10.1093/alcalc/ags066

17. Pierce M, Sutterland A, Beraha EM, et al. Efficacy, tolerability, and safety of low-dose and high-dose baclofen in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;28(7):795-806. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.03.017

18. Andrade C. Individualized, high-dose baclofen for reduction in alcohol intake in persons with high levels of consumption. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(4):20f13606. doi:10.4088/JCP.20f13606

19. Reus VI, Fochtmann LJ, Bukstein O, et al. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the pharmacological treatment of patients with alcohol use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(1):86-90. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.1750101

20. Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1889-1900. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3628

21. US Department of Veterans Affairs, US Department of Defense. Management of Substance Use Disorder (SUD) (2021). US Department of Veterans Affairs. 2021. Accessed December 24, 2022. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/mh/sud/

22. Potenza MN, Balodis IM, Derevensky J, et al. Gambling disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):51. doi:10.1038/s41572-019-0099-7

23. Lupi M, Martinotti G, Acciavatti T, et al. Pharmacological treatments in gambling disorder: a qualitative review. BioMed Res Int. 2014;537306. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2014/537306/

24. Choi SW, Shin YC, Kim DJ, et al. Treatment modalities for patients with gambling disorder. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2017;16:23. doi:10.1186/s12991-017-0146-2

25. Kim SW, Grant JE. An open naltrexone treatment study in pathological gambling disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;16(5):285-289. doi:10.1097/00004850-200109000-00006

26. Kim SW, Grant JE, Adson DE, et al. Double-blind naltrexone and placebo comparison study in the treatment of pathological gambling. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49(11):914-921. doi:10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01079-4

27. Grant JE, Kim SW, Hartman BK. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the opiate antagonist naltrexone in the treatment of pathological gambling urges. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(5):783-789. doi:10.4088/jcp.v69n0511

28. Kovanen L, Basnet S, Castrén S, et al. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of as-needed naltrexone in the treatment of pathological gambling. Eur Addict Res. 2016;22(2):70-79. doi:10.1159/000435876

29. Grant JE, Potenza MN, Hollander E, et al. Multicenter investigation of the opioid antagonist nalmefene in the treatment of pathological gambling. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(2):303-312. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.303

30. Tomko RL, Jones JL, Gilmore AK, et al. N-acetylcysteine: a potential treatment for substance use disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(6):30-36,41-52,55.

31. Grant JE, Kim SW, Odlaug BL. N-acetyl cysteine, a glutamate-modulating agent, in the treatment of pathological gambling: a pilot study. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(6):652-657. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.021

32. G

33. Goslar M, Leibetseder M, Muench HM, et al. Pharmacological treatments for disordered gambling: a meta-analysis. J Gambling Stud. 2019;35(2):415-445. doi:10.1007/s10899-018-09815-y

34. Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Spencer MR, et al. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. December 30, 2021. Accessed December 11, 2022. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/112340

35. Colfax GN, Santos GM, Das M, et al. Mirtazapine to reduce methamphetamine use: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(11):1168-1175. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.124

36. Coffin PO, Santos GM, Hern J, et al. Effects of mirtazapine for methamphetamine use disorder among cisgender men and transgender women who have sex with men: a placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(3):246-255. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3655

37. Shoptaw S, Heinzerling KG, Rotheram-Fuller E, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of bupropion for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Dependence. 2008;96(3):222-232. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.010

38. Trivedi MH, Walker R, Ling W, et al. Bupropion and naltrexone in methamphetamine use disorder. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(2):140-153. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2020214

39. Jayaram-Lindström N, Hammarberg A, Beck O, et al. Naltrexone for the treatment of amphetamine dependence: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(11):1442-1448. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08020304

40. Schmitz JM, Stotts AL, Rhoades HM, et al. Naltrexone and relapse prevention treatment for cocaine-dependent patients. Addict Behav. 2001;26(2):167-180. doi:10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00098-8

41. Oslin DW, Pettinati HM, Volpicelli JR, et al. The effects of naltrexone on alcohol and cocaine use in dually addicted patients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1999;16(2):163-167. doi:10.1016/s0740-5472(98)00039-7

42. Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Wang XQ, et al. Topiramate for the treatment of cocaine addiction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(12):1338-1346. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2295

43. Kampman KM, Pettinati H, Lynch KG, et al. A pilot trial of topiramate for the treatment of cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Dependence. 2004;75(3):233-240. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.03.008

44. Elkashef A, Kahn R, Yu E, et al. Topiramate for the treatment of methamphetamine addiction: a multi-center placebo-controlled trial. Addiction. 2012;107(7):1297-1306. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03771.x

45. Hasin DS. US epidemiology of cannabis use and associated problems. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43(1):195-212.

46. Brezing CA, Levin FR. The current state of pharmacological treatments for cannabis use disorder and withdrawal. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43(1):173-194. doi:10.1038/npp.2017.198

47. Bahji A, Meyyappan AC, Hawken ER, et al. Pharmacotherapies for cannabis use disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Intl J Drug Policy. 2021;97:103295. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103295

48. Gray KM, Carpenter MJ, Baker NL, et al. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of N-acetylcysteine in cannabis-dependent adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(8):805-812. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12010055

49. Roten AT, Baker NL, Gray KM. Marijuana craving trajectories in an adolescent marijuana cessation pharmacotherapy trial. Addict Behav. 2013;38(3):1788-1791. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.11.003

50. McClure EA, Sonne SC, Winhusen T, et al. Achieving cannabis cessation—evaluating N-acetylcysteine treatment (ACCENT): design and implementation of a multi-site, randomized controlled study in the National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;39(2):211-223. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2014.08.011

51. Gray KM, Sonne SC, McClure EA, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of N-acetylcysteine for cannabis use disorder in adults. Drug Alcohol Dependence. 2017;177:249-257. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.04.020

52. Mason BJ, Crean R, Goodell V, et al. A proof-of-concept randomized controlled study of gabapentin: effects on cannabis use, withdrawal and executive function deficits in cannabis-dependent adults. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(7):1689-1698. doi:10.1038/npp.2012.14

Off-label prescribing (OLP) refers to the practice of using medications for indications outside of those approved by the FDA, or in dosages, dose forms, or patient populations that have not been approved by the FDA.1 OLP is common, occurring in many practice settings and nearly every medical specialty. In a 2006 review, Radley et al2 found OLP accounted for 21% of the overall use of 160 common medications. The frequency of OLP varies between medication classes. Off-label use of anticonvulsants, antidepressants, and antipsychotics tends to be higher than that of other medications.3,4 OLP is often more common

Box

Several aspects contribute to off-label prescribing (OLP). First, there is little financial incentive for pharmaceutical companies to seek new FDA indications for existing medications. In addition, there are no FDA-approved medications for many disorders included in DSM-5, and treatment of these conditions relies almost exclusively on the practice of OLP. Finally, patients enrolled in clinical trials must often meet stringent exclusion criteria, such as the lack of comorbid substance use disorders. For these reasons, using off-label medications to treat substance-related and addictive disorders is particularly necessary.

Several important medicolegal and ethical considerations surround OLP. The FDA prohibits off-label promotion, in which manufacturers advertise the use of a medication for off-label use.5 However, regulations allow physicians to use their best clinical judgment when prescribing medications for off-label use. When considering off-label use of any medication, physicians should review the most up-to-date research, including clinical trials, case reports, and reviews to safely support their decision-making. OLP should be guided by ethical principles such as autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice. Physicians should obtain informed consent by conducting an appropriate discussion of the risks, benefits, and alternatives of off-label medications. This conversation should be clearly documented, and physicians should provide written material regarding off-label options to patients when available. Finally, physicians should verify their patients’ understanding of this discussion, and allow patients to accept or decline off-label medications without pressure.

This article focuses on current and potential future medications available for OLP to treat patients with alcohol use disorder (AUD), gambling disorder (GD), stimulant use disorder, and cannabis use disorder.

Alcohol use disorder

CASE 1

Ms. X, age 67, has a history of severe AUD, mild renal impairment, and migraines. She presents to the outpatient clinic seeking help to drink less alcohol. Ms. X reports drinking 1 to 2 bottles of wine each day. She was previously treated for AUD but was not helped by naltrexone and did not tolerate disulfiram (abstinence was not her goal and she experienced significant adverse effects). Ms. X says she has a medical history of chronic migraines but denies other medical issues. The treatment team discusses alternative pharmacologic options, including acamprosate and topiramate. After outlining the dosing schedule and risks/benefits with Ms. X, you make the joint decision to start topiramate to reduce alcohol cravings and target her migraine symptoms.

Only 3 medications are FDA-approved for treating AUD: disulfiram, naltrexone (oral and injectable formulations), and acamprosate. Off-label options for AUD treatment include gabapentin, topiramate, and baclofen.

Gabapentin is FDA-approved for treating postherpetic neuralgia and partial seizures in patients age ≥3. The exact mechanism of action is unclear, though its effects are possibly related to its activity as a calcium channel ligand. It also carries a structural resemblance to gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), though it lacks activity at GABA receptors.

Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the efficacy of gabapentin for AUD produced promising results. In a comparison of gabapentin vs placebo for AUD, Anton et al6 found gabapentin led to significant increases in the number of participants with total alcohol abstinence and participants who reported reduced drinking. Notably, the effect was most prominent in those with heavy drinking patterns and pretreatment alcohol withdrawal symptoms. A total of 41% of participants with high alcohol withdrawal scores on pretreatment evaluation achieved total abstinence while taking gabapentin, compared to 1% in the placebo group.6 A meta-analysis of gabapentin for AUD by Kranzler et al7 included 7 RCTs and 32 effect measures. It found that although all outcome measures favored gabapentin over placebo, only the percentage of heavy drinking days was significantly different.

Gabapentin is dosed between 300 to 600 mg 3 times per day, but 1 study found that a higher dose (1,800 mg/d) was associated with better outcomes.8 Common adverse effects include sedation, dizziness, peripheral edema, and ataxia.

Continue to: Topiramate

Topiramate blocks voltage-gated sodium channels and enhances GABA-A receptor activity.9 It is indicated for the treatment of seizures, migraine prophylaxis, weight management, and weight loss. Several clinical trials, including RCTs,10-12 demonstrated that topiramate was superior to placebo in reducing the percentage of heavy drinking days and overall drinking days. Some also showed that topiramate was associated with abstinence and reduced craving levels.12,13 A meta-analysis by Blodgett et al14 found that compared to placebo, topiramate lowered the rate of heavy drinking and increased abstinence.

Topiramate is dosed from 50 to 150 mg twice daily, although some studies suggest a lower dose (≤75 mg/d) may be associated with clinical benefits.15,16 One important clinical consideration: topiramate must follow a slow titration schedule (4 to 6 weeks) to increase tolerability and avoid adverse effects. Common adverse effects include sedation, word-finding difficulty, paresthesia, increased risk for renal calculi, dizziness, anorexia, and alterations in taste.

Baclofen is a GABA-B agonist FDA-approved for the treatment of muscle spasticity related to multiple sclerosis and reversible spasticity related to spinal cord lesions and multiple sclerosis. Of note, it is approved for treatment of AUD in Europe.

In a meta-analysis of 13 RCTs, Pierce et al17 found a greater likelihood of abstinence and greater time to first lapse of drinking with baclofen compared to placebo. Interestingly, a subgroup analysis found that the positive effects were limited to trials that used 30 to 60 mg/d of baclofen, and not evident in those that used higher doses. Additionally, there was no difference between baclofen and placebo with regard to several important outcomes, including alcohol cravings, anxiety, depression, or number of total abstinent days. A review by Andrade18 proposed that individualized treatment with high-dose baclofen (30 to 300 mg/d) may be a useful second-line approach in heavy drinkers who wish to reduce their alcohol intake.

Continue to: Before starting baclofen...

Before starting baclofen, patients should be informed about its adverse effects. Common adverse effects include sedation and motor impairment. More serious but less common adverse effects include seizures, respiratory depression with sleep apnea, severe mood disorders (ie, mania, depression, or suicide risk), and mental confusion. Baclofen should be gradually discontinued, because there is some risk of clinical withdrawal symptoms (ie, agitation, confusion, seizures, or delirium).

Among the medications discussed in this section, the evidence for gabapentin and topiramate is moderate to strong, while the evidence for baclofen is overall weaker or mixed. The American Psychiatric Association’s Practice Guideline suggests offering gabapentin or topiramate to patients with moderate to severe AUD whose goal is to achieve abstinence or reduce alcohol use, or those who prefer gabapentin or topiramate or cannot tolerate or have not responded to naltrexone and acamprosate.19 Clinicians must ensure patients have no contraindications to the use of these medications. Due to the moderate quality evidence for a significant reduction in heavy drinking and increased abstinence,14,20 a practice guideline from the US Department of Veterans Affairs and US Department of Defense21 recommends topiramate as 1 of 2 first-line treatments (the other is naltrexone). This guideline suggests gabapentin as a second-line treatment for AUD.21

Gambling disorder

CASE 2

Mr. P, age 28, seeks treatment for GD and cocaine use disorder. He reports a 7-year history of sports betting that has increasingly impaired his functioning over the past year. He lost his job, savings, and familial relationships due to his impulsive and risky behavior. Mr. P also reports frequent cocaine use, about 2 to 3 days per week, mostly on the weekends. The psychiatrist tells Mr. P there is no FDA-approved pharmacologic treatment for GD or cocaine use disorder. The psychiatrist discusses the option of naltrexone as off-label treatment for GD with the goal of reducing Mr. P’s urges to gamble, and points to possible benefits for cocaine use disorder.

GD impacts approximately 0.5% of the adult US population and is often co-occurring with substance use disorders.22 It is thought to share neurobiological and clinical similarities with substance use disorders.23 There are currently no FDA-approved medications to treat the disorder. In studies of GD, treatment success with antidepressants and mood stabilizers has not been consistent,23,24 but some promising results have been published for the opioid receptor antagonist naltrexone24-29 and N-acetylcysteine (NAC).30-32

Naltrexone is thought to reduce gambling behavior and urges via downstream modulation of mesolimbic dopamine circuitry.24 It is FDA-approved for the treatment of AUD and opioid use disorder. Open-label RCTs have found a reduction in gambling urges and behavior with daily naltrexone.25-27 Dosing at 50 mg/d appears to be just as efficacious as higher doses such as 100 and 150 mg/d.27 When used as a daily as-needed medication for strong gambling urges or if an individual was planning to gamble, naltrexone 50 mg/d was not effective.28

Continue to: Naltrexone typically is started...

Naltrexone typically is started at 25 mg/d to assess tolerability and quickly titrated to 50 mg/d. When titrating, common adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, and transient elevations in transaminases. Another opioid antagonist, nalmefene, has also been studied in patients with GD. An RCT by Grant et al29 that evaluated 207 patients found that compared with placebo, nalmefene 25 mg/d for 16 weeks was associated with a significant reduction in gambling assessment scores. In Europe, nalmefene is approved for treating AUD but the oral formulation is not currently available in the US.

N-acetylcysteine is thought to potentially reverse neuronal dysfunction seen in addictive disorders by glutamatergic modulation.30 Research investigating NAC for GD is scarce. A pilot study found 16 of 27 patients with GD reduced gambling behavior with a mean dose of 1,476.9 mg/d.31 An additional study investigating the addition of NAC to behavioral therapy in nicotine-dependent individuals with pathologic gambling found a reduction in problem gambling after 18 weeks (6 weeks + 3 months follow-up).32 Common but mild adverse effects associated with NAC are nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

A meta-analysis by Goslar et al33 that reviewed 34 studies (1,340 participants) found pharmacologic treatments were associated with large and medium pre-post reductions in global severity, frequency, and financial loss in patients with GD. RCTs studying opioid antagonists and mood stabilizers (combined with a cognitive intervention) as well as lithium for patients with comorbid bipolar disorder and GD demonstrated promising results.33

Stimulant use disorder

There are no FDA-approved medications for stimulant use disorder. Multiple off-label options have been studied for the treatment of methamphetamine abuse and cocaine abuse.

Methamphetamine use has been expanding over the past decade with a 3.6-fold increase in positive methamphetamine screens in overdose deaths from 2011 to 2016.34 Pharmacologic options studied for OLP of methamphetamine use disorder include mirtazapine, bupropion, naltrexone, and topiramate.

Continue to: Mirtazapine

Mirtazapine is an atypical antidepressant whose mechanism of action includes modulation of the serotonin, norepinephrine, and alpha-2 adrenergic systems. It is FDA-approved for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). In a randomized placebo-controlled study, mirtazapine 30 mg/d at night was found to decrease methamphetamine use for active users and led to decreased sexual risk in men who have sex with men.35 These results were supported by an additional RCT in which mirtazapine 30 mg/d significantly reduced rates of methamphetamine use vs placebo at 24 and 36 weeks despite poor medication adherence.36 Adverse effects to monitor in patients treated with mirtazapine include increased appetite, weight gain, sedation, and constipation.

Bupropion is a norepinephrine dopamine reuptake inhibitor that produces increased neurotransmission of norepinephrine and dopamine in the CNS. It is FDA-approved for the treatment of MDD and as an aid for smoking cessation. Bupropion has been studied for methamphetamine use disorder with mixed results. In a randomized placebo-controlled trial, bupropion sustained release 15

Naltrexone. Data about using oral naltrexone to treat stimulant use disorders are limited. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial by Jayaram-Lindström et al39 found naltrexone 50 mg/d significantly reduced amphetamine use compared to placebo. Additionally, naltrexone 50 and 150 mg/d have been shown to reduce cocaine use over time in combination with therapy for cocaine-dependent patients and those dependent on alcohol and cocaine.40,41

Topiramate has been studied for the treatment of cocaine use disorder. It is hypothesized that modulation of the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system may contribute to decreased cocaine cravings.42 A pilot study by Kampman et al43 found that after an 8-week titration of topiramate to 200 mg/d, individuals were more likely to achieve cocaine abstinence compared to those who receive placebo. In an RCT, Elkashef et al44 did not find topiramate assisted with increased abstinence of methamphetamine in active users at a target dose of 200 mg/d. However, it was associated with reduced relapse rates in individuals who were abstinent prior to the study.44 At a target dose of 300 mg/d, topiramate also outperformed placebo in decreasing days of cocaine use.42 Adverse effects of topiramate included paresthesia, alteration in taste, and difficulty with concentration.

Cannabis use disorder

In recent years, cannabis use in the US has greatly increased45 but no medications are FDA-approved for treating cannabis use disorder. Studies of pharmacologic options for cannabis use disorder have had mixed results.46 A meta-analysis by Bahji et al47 of 24 studies investigating pharmacotherapies for cannabis use disorder highlighted the lack of adequate evidence. In this section, we focus on a few positive trials of NAC and gabapentin.

Continue to: N-acetylcysteine

N-acetylcysteine. Studies investigating NAC 1,200 mg twice daily have been promising in adolescent and adult populations.48-50 There are some mixed results, however. A large RCT found NAC 1,200 mg twice daily was not better than placebo in helping adults achieve abstinence from cannabis.51

Gabapentin may be a viable option for treating cannabis use disorder. A pilot study by Mason et al52 found gabapentin 1,200 mg/d was more effective than placebo at reducing cannabis use among treatment-seeking adults.

When and how to consider OLP

OLP for addictive disorders is common and often necessary. This is primarily due to limitations of the FDA-approved medications and because there are no FDA-approved medications for many substance-related and addictive disorders (ie, GD, cannabis use disorder, and stimulant use disorder). When assessing pharmacotherapy options, if FDA-approved medications are available for certain diagnoses, clinicians should first consider them. The off-label medications discussed in this article are outlined in the Table.6-21,24-28,30-33,35-44,48-52

The overall level of evidence to support the use of off-label medications is lower than that of FDA-approved medications, which contributes to potential medicolegal concerns of OLP. Off-label medications should be considered when there are no FDA-approved medications available, and the decision to use off-label medications should be based on evidence from the literature and current standard of care. Additionally, OLP is necessary if a patient cannot tolerate FDA-approved medications, is not helped by FDA-approved treatments, or when there are other clinical reasons to choose a particular off-label medication. For example, if a patient has comorbid AUD and obesity (or migraines), using topiramate may be appropriate because it may target alcohol cravings and can be helpful for weight loss (and migraine prophylaxis). Similarly, for patients with AUD and neuropathic pain, using gabapentin can be considered for its dual therapeutic effects.

It is critical for clinicians to understand the landscape of off-label options for treating addictive disorders. Additional research in the form of RCTs is needed to better clarify the efficacy and adverse effects of these treatments.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Off-label prescribing is prevalent in practice, including in the treatment of substance-related and addictive disorders. When considering off-label use of any medication, clinicians should review the most recent research, obtain informed consent from patients, and verify patients’ understanding of the potential risks and adverse effects associated with the particular medication.

Related Resources

- Joshi KG, Frierson RL. Off-label prescribing: how to limit your liability. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(9):12,39. doi:10.12788/ cp.0035

- Stanciu CN, Gnanasegaram SA. Don’t balk at using medical therapy to manage alcohol use disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(2):50-52.

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Baclofen • Ozobax

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Disulfiram • Antabuse

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Naltrexone • ReVia, Vivitrol

Topiramate • Topamax

Off-label prescribing (OLP) refers to the practice of using medications for indications outside of those approved by the FDA, or in dosages, dose forms, or patient populations that have not been approved by the FDA.1 OLP is common, occurring in many practice settings and nearly every medical specialty. In a 2006 review, Radley et al2 found OLP accounted for 21% of the overall use of 160 common medications. The frequency of OLP varies between medication classes. Off-label use of anticonvulsants, antidepressants, and antipsychotics tends to be higher than that of other medications.3,4 OLP is often more common

Box

Several aspects contribute to off-label prescribing (OLP). First, there is little financial incentive for pharmaceutical companies to seek new FDA indications for existing medications. In addition, there are no FDA-approved medications for many disorders included in DSM-5, and treatment of these conditions relies almost exclusively on the practice of OLP. Finally, patients enrolled in clinical trials must often meet stringent exclusion criteria, such as the lack of comorbid substance use disorders. For these reasons, using off-label medications to treat substance-related and addictive disorders is particularly necessary.

Several important medicolegal and ethical considerations surround OLP. The FDA prohibits off-label promotion, in which manufacturers advertise the use of a medication for off-label use.5 However, regulations allow physicians to use their best clinical judgment when prescribing medications for off-label use. When considering off-label use of any medication, physicians should review the most up-to-date research, including clinical trials, case reports, and reviews to safely support their decision-making. OLP should be guided by ethical principles such as autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice. Physicians should obtain informed consent by conducting an appropriate discussion of the risks, benefits, and alternatives of off-label medications. This conversation should be clearly documented, and physicians should provide written material regarding off-label options to patients when available. Finally, physicians should verify their patients’ understanding of this discussion, and allow patients to accept or decline off-label medications without pressure.

This article focuses on current and potential future medications available for OLP to treat patients with alcohol use disorder (AUD), gambling disorder (GD), stimulant use disorder, and cannabis use disorder.

Alcohol use disorder

CASE 1

Ms. X, age 67, has a history of severe AUD, mild renal impairment, and migraines. She presents to the outpatient clinic seeking help to drink less alcohol. Ms. X reports drinking 1 to 2 bottles of wine each day. She was previously treated for AUD but was not helped by naltrexone and did not tolerate disulfiram (abstinence was not her goal and she experienced significant adverse effects). Ms. X says she has a medical history of chronic migraines but denies other medical issues. The treatment team discusses alternative pharmacologic options, including acamprosate and topiramate. After outlining the dosing schedule and risks/benefits with Ms. X, you make the joint decision to start topiramate to reduce alcohol cravings and target her migraine symptoms.

Only 3 medications are FDA-approved for treating AUD: disulfiram, naltrexone (oral and injectable formulations), and acamprosate. Off-label options for AUD treatment include gabapentin, topiramate, and baclofen.

Gabapentin is FDA-approved for treating postherpetic neuralgia and partial seizures in patients age ≥3. The exact mechanism of action is unclear, though its effects are possibly related to its activity as a calcium channel ligand. It also carries a structural resemblance to gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), though it lacks activity at GABA receptors.

Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) evaluating the efficacy of gabapentin for AUD produced promising results. In a comparison of gabapentin vs placebo for AUD, Anton et al6 found gabapentin led to significant increases in the number of participants with total alcohol abstinence and participants who reported reduced drinking. Notably, the effect was most prominent in those with heavy drinking patterns and pretreatment alcohol withdrawal symptoms. A total of 41% of participants with high alcohol withdrawal scores on pretreatment evaluation achieved total abstinence while taking gabapentin, compared to 1% in the placebo group.6 A meta-analysis of gabapentin for AUD by Kranzler et al7 included 7 RCTs and 32 effect measures. It found that although all outcome measures favored gabapentin over placebo, only the percentage of heavy drinking days was significantly different.

Gabapentin is dosed between 300 to 600 mg 3 times per day, but 1 study found that a higher dose (1,800 mg/d) was associated with better outcomes.8 Common adverse effects include sedation, dizziness, peripheral edema, and ataxia.

Continue to: Topiramate

Topiramate blocks voltage-gated sodium channels and enhances GABA-A receptor activity.9 It is indicated for the treatment of seizures, migraine prophylaxis, weight management, and weight loss. Several clinical trials, including RCTs,10-12 demonstrated that topiramate was superior to placebo in reducing the percentage of heavy drinking days and overall drinking days. Some also showed that topiramate was associated with abstinence and reduced craving levels.12,13 A meta-analysis by Blodgett et al14 found that compared to placebo, topiramate lowered the rate of heavy drinking and increased abstinence.

Topiramate is dosed from 50 to 150 mg twice daily, although some studies suggest a lower dose (≤75 mg/d) may be associated with clinical benefits.15,16 One important clinical consideration: topiramate must follow a slow titration schedule (4 to 6 weeks) to increase tolerability and avoid adverse effects. Common adverse effects include sedation, word-finding difficulty, paresthesia, increased risk for renal calculi, dizziness, anorexia, and alterations in taste.

Baclofen is a GABA-B agonist FDA-approved for the treatment of muscle spasticity related to multiple sclerosis and reversible spasticity related to spinal cord lesions and multiple sclerosis. Of note, it is approved for treatment of AUD in Europe.

In a meta-analysis of 13 RCTs, Pierce et al17 found a greater likelihood of abstinence and greater time to first lapse of drinking with baclofen compared to placebo. Interestingly, a subgroup analysis found that the positive effects were limited to trials that used 30 to 60 mg/d of baclofen, and not evident in those that used higher doses. Additionally, there was no difference between baclofen and placebo with regard to several important outcomes, including alcohol cravings, anxiety, depression, or number of total abstinent days. A review by Andrade18 proposed that individualized treatment with high-dose baclofen (30 to 300 mg/d) may be a useful second-line approach in heavy drinkers who wish to reduce their alcohol intake.

Continue to: Before starting baclofen...

Before starting baclofen, patients should be informed about its adverse effects. Common adverse effects include sedation and motor impairment. More serious but less common adverse effects include seizures, respiratory depression with sleep apnea, severe mood disorders (ie, mania, depression, or suicide risk), and mental confusion. Baclofen should be gradually discontinued, because there is some risk of clinical withdrawal symptoms (ie, agitation, confusion, seizures, or delirium).

Among the medications discussed in this section, the evidence for gabapentin and topiramate is moderate to strong, while the evidence for baclofen is overall weaker or mixed. The American Psychiatric Association’s Practice Guideline suggests offering gabapentin or topiramate to patients with moderate to severe AUD whose goal is to achieve abstinence or reduce alcohol use, or those who prefer gabapentin or topiramate or cannot tolerate or have not responded to naltrexone and acamprosate.19 Clinicians must ensure patients have no contraindications to the use of these medications. Due to the moderate quality evidence for a significant reduction in heavy drinking and increased abstinence,14,20 a practice guideline from the US Department of Veterans Affairs and US Department of Defense21 recommends topiramate as 1 of 2 first-line treatments (the other is naltrexone). This guideline suggests gabapentin as a second-line treatment for AUD.21

Gambling disorder

CASE 2

Mr. P, age 28, seeks treatment for GD and cocaine use disorder. He reports a 7-year history of sports betting that has increasingly impaired his functioning over the past year. He lost his job, savings, and familial relationships due to his impulsive and risky behavior. Mr. P also reports frequent cocaine use, about 2 to 3 days per week, mostly on the weekends. The psychiatrist tells Mr. P there is no FDA-approved pharmacologic treatment for GD or cocaine use disorder. The psychiatrist discusses the option of naltrexone as off-label treatment for GD with the goal of reducing Mr. P’s urges to gamble, and points to possible benefits for cocaine use disorder.

GD impacts approximately 0.5% of the adult US population and is often co-occurring with substance use disorders.22 It is thought to share neurobiological and clinical similarities with substance use disorders.23 There are currently no FDA-approved medications to treat the disorder. In studies of GD, treatment success with antidepressants and mood stabilizers has not been consistent,23,24 but some promising results have been published for the opioid receptor antagonist naltrexone24-29 and N-acetylcysteine (NAC).30-32

Naltrexone is thought to reduce gambling behavior and urges via downstream modulation of mesolimbic dopamine circuitry.24 It is FDA-approved for the treatment of AUD and opioid use disorder. Open-label RCTs have found a reduction in gambling urges and behavior with daily naltrexone.25-27 Dosing at 50 mg/d appears to be just as efficacious as higher doses such as 100 and 150 mg/d.27 When used as a daily as-needed medication for strong gambling urges or if an individual was planning to gamble, naltrexone 50 mg/d was not effective.28

Continue to: Naltrexone typically is started...

Naltrexone typically is started at 25 mg/d to assess tolerability and quickly titrated to 50 mg/d. When titrating, common adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, and transient elevations in transaminases. Another opioid antagonist, nalmefene, has also been studied in patients with GD. An RCT by Grant et al29 that evaluated 207 patients found that compared with placebo, nalmefene 25 mg/d for 16 weeks was associated with a significant reduction in gambling assessment scores. In Europe, nalmefene is approved for treating AUD but the oral formulation is not currently available in the US.

N-acetylcysteine is thought to potentially reverse neuronal dysfunction seen in addictive disorders by glutamatergic modulation.30 Research investigating NAC for GD is scarce. A pilot study found 16 of 27 patients with GD reduced gambling behavior with a mean dose of 1,476.9 mg/d.31 An additional study investigating the addition of NAC to behavioral therapy in nicotine-dependent individuals with pathologic gambling found a reduction in problem gambling after 18 weeks (6 weeks + 3 months follow-up).32 Common but mild adverse effects associated with NAC are nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea.

A meta-analysis by Goslar et al33 that reviewed 34 studies (1,340 participants) found pharmacologic treatments were associated with large and medium pre-post reductions in global severity, frequency, and financial loss in patients with GD. RCTs studying opioid antagonists and mood stabilizers (combined with a cognitive intervention) as well as lithium for patients with comorbid bipolar disorder and GD demonstrated promising results.33

Stimulant use disorder

There are no FDA-approved medications for stimulant use disorder. Multiple off-label options have been studied for the treatment of methamphetamine abuse and cocaine abuse.

Methamphetamine use has been expanding over the past decade with a 3.6-fold increase in positive methamphetamine screens in overdose deaths from 2011 to 2016.34 Pharmacologic options studied for OLP of methamphetamine use disorder include mirtazapine, bupropion, naltrexone, and topiramate.

Continue to: Mirtazapine

Mirtazapine is an atypical antidepressant whose mechanism of action includes modulation of the serotonin, norepinephrine, and alpha-2 adrenergic systems. It is FDA-approved for the treatment of major depressive disorder (MDD). In a randomized placebo-controlled study, mirtazapine 30 mg/d at night was found to decrease methamphetamine use for active users and led to decreased sexual risk in men who have sex with men.35 These results were supported by an additional RCT in which mirtazapine 30 mg/d significantly reduced rates of methamphetamine use vs placebo at 24 and 36 weeks despite poor medication adherence.36 Adverse effects to monitor in patients treated with mirtazapine include increased appetite, weight gain, sedation, and constipation.

Bupropion is a norepinephrine dopamine reuptake inhibitor that produces increased neurotransmission of norepinephrine and dopamine in the CNS. It is FDA-approved for the treatment of MDD and as an aid for smoking cessation. Bupropion has been studied for methamphetamine use disorder with mixed results. In a randomized placebo-controlled trial, bupropion sustained release 15

Naltrexone. Data about using oral naltrexone to treat stimulant use disorders are limited. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial by Jayaram-Lindström et al39 found naltrexone 50 mg/d significantly reduced amphetamine use compared to placebo. Additionally, naltrexone 50 and 150 mg/d have been shown to reduce cocaine use over time in combination with therapy for cocaine-dependent patients and those dependent on alcohol and cocaine.40,41

Topiramate has been studied for the treatment of cocaine use disorder. It is hypothesized that modulation of the mesocorticolimbic dopamine system may contribute to decreased cocaine cravings.42 A pilot study by Kampman et al43 found that after an 8-week titration of topiramate to 200 mg/d, individuals were more likely to achieve cocaine abstinence compared to those who receive placebo. In an RCT, Elkashef et al44 did not find topiramate assisted with increased abstinence of methamphetamine in active users at a target dose of 200 mg/d. However, it was associated with reduced relapse rates in individuals who were abstinent prior to the study.44 At a target dose of 300 mg/d, topiramate also outperformed placebo in decreasing days of cocaine use.42 Adverse effects of topiramate included paresthesia, alteration in taste, and difficulty with concentration.

Cannabis use disorder

In recent years, cannabis use in the US has greatly increased45 but no medications are FDA-approved for treating cannabis use disorder. Studies of pharmacologic options for cannabis use disorder have had mixed results.46 A meta-analysis by Bahji et al47 of 24 studies investigating pharmacotherapies for cannabis use disorder highlighted the lack of adequate evidence. In this section, we focus on a few positive trials of NAC and gabapentin.

Continue to: N-acetylcysteine

N-acetylcysteine. Studies investigating NAC 1,200 mg twice daily have been promising in adolescent and adult populations.48-50 There are some mixed results, however. A large RCT found NAC 1,200 mg twice daily was not better than placebo in helping adults achieve abstinence from cannabis.51

Gabapentin may be a viable option for treating cannabis use disorder. A pilot study by Mason et al52 found gabapentin 1,200 mg/d was more effective than placebo at reducing cannabis use among treatment-seeking adults.

When and how to consider OLP

OLP for addictive disorders is common and often necessary. This is primarily due to limitations of the FDA-approved medications and because there are no FDA-approved medications for many substance-related and addictive disorders (ie, GD, cannabis use disorder, and stimulant use disorder). When assessing pharmacotherapy options, if FDA-approved medications are available for certain diagnoses, clinicians should first consider them. The off-label medications discussed in this article are outlined in the Table.6-21,24-28,30-33,35-44,48-52

The overall level of evidence to support the use of off-label medications is lower than that of FDA-approved medications, which contributes to potential medicolegal concerns of OLP. Off-label medications should be considered when there are no FDA-approved medications available, and the decision to use off-label medications should be based on evidence from the literature and current standard of care. Additionally, OLP is necessary if a patient cannot tolerate FDA-approved medications, is not helped by FDA-approved treatments, or when there are other clinical reasons to choose a particular off-label medication. For example, if a patient has comorbid AUD and obesity (or migraines), using topiramate may be appropriate because it may target alcohol cravings and can be helpful for weight loss (and migraine prophylaxis). Similarly, for patients with AUD and neuropathic pain, using gabapentin can be considered for its dual therapeutic effects.

It is critical for clinicians to understand the landscape of off-label options for treating addictive disorders. Additional research in the form of RCTs is needed to better clarify the efficacy and adverse effects of these treatments.

Continue to: Bottom Line

Bottom Line

Off-label prescribing is prevalent in practice, including in the treatment of substance-related and addictive disorders. When considering off-label use of any medication, clinicians should review the most recent research, obtain informed consent from patients, and verify patients’ understanding of the potential risks and adverse effects associated with the particular medication.

Related Resources

- Joshi KG, Frierson RL. Off-label prescribing: how to limit your liability. Current Psychiatry. 2020;19(9):12,39. doi:10.12788/ cp.0035

- Stanciu CN, Gnanasegaram SA. Don’t balk at using medical therapy to manage alcohol use disorder. Current Psychiatry. 2017;16(2):50-52.

Drug Brand Names

Acamprosate • Campral

Baclofen • Ozobax

Bupropion • Wellbutrin, Zyban

Disulfiram • Antabuse

Gabapentin • Neurontin

Lithium • Eskalith, Lithobid

Mirtazapine • Remeron

Naltrexone • ReVia, Vivitrol

Topiramate • Topamax

1. Wittich CM, Burkle CM, Lanier WL. Ten common questions (and their answers) about off-label drug use. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(10):982-990. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.04.017

2. Radley DC, Finkelstein SN, Stafford RS. Off-label prescribing among office-based physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):1021-1026. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.9.1021

3. Wang J, Jiang F, Yating Y, et al. Off-label use of antipsychotic medications in psychiatric inpatients in China: a national real-world survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):375. doi:10.1186/s12888-021-03374-0

4. Chen H, Reeves JH, Fincham JE, et al. Off-label use of antidepressant, anticonvulsant, and antipsychotic medications among Georgia Medicaid enrollees in 2001. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(6):972-982. doi:10.4088/jcp.v67n0615

5. Ventola CL. Off-label drug information: regulation, distribution, evaluation, and related controversies. P T. 2009;34(8):428-440.

6. Anton RF, Latham P, Voronin K, et al. Efficacy of gabapentin for the treatment of alcohol use disorder in patients with alcohol withdrawal symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(5):728-736. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0249

7. Kranzler HR, Feinn R, Morris P, et al. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of gabapentin for treating alcohol use disorder. Addiction. 2019;114(9):1547-1555. doi:10.1111/add.14655

8. Mason BJ, Quello S, Goodell V. Gabapentin treatment for alcohol dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):70-77. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.11950

9. Fariba KA. Saadabadi A. Topiramate. StatPearls [Internet]. StatPearls Publishing LLC; 2023. Accessed December 22, 2022. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK554530/

10. Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Bowden CL, et al. Oral topiramate for treatment of alcohol dependence: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2003;361(9370):1677-1685. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13370-3

11. Johnson BA, Rosenthal N, Capece JA, et al. Topiramate for treating alcohol dependence: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2007;298(14):1641-1651. doi:10.1001/jama.298.14.1641

12. Knapp CM, Ciraulo DA, Sarid-Segal O, et al. Zonisamide, topiramate, and levetiracetam: efficacy and neuropsychological effects in alcohol use disorders. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2015;35(1):34-42. doi:10.1097/JCP.0000000000000246

13. Kranzler HR, Covault J, Feinn R, et al. Topiramate treatment for heavy drinkers: moderation by a GRIK1 polymorphism. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(4):445-452. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.13081014

14. Blodgett JC, Del Re AC, Maisel NC, et al. A meta-analysis of topiramate’s effects for individuals with alcohol use disorders. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2014;38(6):1481-1488. doi:10.1111/acer.12411

15. Paparrigopoulos T, Tzavellas E, Karaiskos D, et al. Treatment of alcohol dependence with low-dose topiramate: an open-label controlled study. BMC Psychiatry. 2011;11:41. doi:10.1186/1471-244X-11-41

16. Tang YL, Hao W, Leggio L. Treatments for alcohol-related disorders in China: a developing story. Alcohol Alcohol. 2012;47(5):563-570. doi:10.1093/alcalc/ags066

17. Pierce M, Sutterland A, Beraha EM, et al. Efficacy, tolerability, and safety of low-dose and high-dose baclofen in the treatment of alcohol dependence: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2018;28(7):795-806. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2018.03.017

18. Andrade C. Individualized, high-dose baclofen for reduction in alcohol intake in persons with high levels of consumption. J Clin Psychiatry. 2020;81(4):20f13606. doi:10.4088/JCP.20f13606

19. Reus VI, Fochtmann LJ, Bukstein O, et al. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the pharmacological treatment of patients with alcohol use disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2018;175(1):86-90. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2017.1750101

20. Jonas DE, Amick HR, Feltner C, et al. Pharmacotherapy for adults with alcohol use disorders in outpatient settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2014;311(18):1889-1900. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.3628

21. US Department of Veterans Affairs, US Department of Defense. Management of Substance Use Disorder (SUD) (2021). US Department of Veterans Affairs. 2021. Accessed December 24, 2022. https://www.healthquality.va.gov/guidelines/mh/sud/

22. Potenza MN, Balodis IM, Derevensky J, et al. Gambling disorder. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2019;5(1):51. doi:10.1038/s41572-019-0099-7

23. Lupi M, Martinotti G, Acciavatti T, et al. Pharmacological treatments in gambling disorder: a qualitative review. BioMed Res Int. 2014;537306. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.hindawi.com/journals/bmri/2014/537306/

24. Choi SW, Shin YC, Kim DJ, et al. Treatment modalities for patients with gambling disorder. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2017;16:23. doi:10.1186/s12991-017-0146-2

25. Kim SW, Grant JE. An open naltrexone treatment study in pathological gambling disorder. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2001;16(5):285-289. doi:10.1097/00004850-200109000-00006

26. Kim SW, Grant JE, Adson DE, et al. Double-blind naltrexone and placebo comparison study in the treatment of pathological gambling. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;49(11):914-921. doi:10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01079-4

27. Grant JE, Kim SW, Hartman BK. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of the opiate antagonist naltrexone in the treatment of pathological gambling urges. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69(5):783-789. doi:10.4088/jcp.v69n0511

28. Kovanen L, Basnet S, Castrén S, et al. A randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of as-needed naltrexone in the treatment of pathological gambling. Eur Addict Res. 2016;22(2):70-79. doi:10.1159/000435876

29. Grant JE, Potenza MN, Hollander E, et al. Multicenter investigation of the opioid antagonist nalmefene in the treatment of pathological gambling. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163(2):303-312. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.163.2.303

30. Tomko RL, Jones JL, Gilmore AK, et al. N-acetylcysteine: a potential treatment for substance use disorders. Current Psychiatry. 2018;17(6):30-36,41-52,55.

31. Grant JE, Kim SW, Odlaug BL. N-acetyl cysteine, a glutamate-modulating agent, in the treatment of pathological gambling: a pilot study. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62(6):652-657. doi:10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.11.021

32. G

33. Goslar M, Leibetseder M, Muench HM, et al. Pharmacological treatments for disordered gambling: a meta-analysis. J Gambling Stud. 2019;35(2):415-445. doi:10.1007/s10899-018-09815-y

34. Hedegaard H, Miniño AM, Spencer MR, et al. Drug overdose deaths in the United States, 1999-2020. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. December 30, 2021. Accessed December 11, 2022. https://stacks.cdc.gov/view/cdc/112340

35. Colfax GN, Santos GM, Das M, et al. Mirtazapine to reduce methamphetamine use: a randomized controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68(11):1168-1175. doi:10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.124

36. Coffin PO, Santos GM, Hern J, et al. Effects of mirtazapine for methamphetamine use disorder among cisgender men and transgender women who have sex with men: a placebo-controlled randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(3):246-255. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.3655

37. Shoptaw S, Heinzerling KG, Rotheram-Fuller E, et al. Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of bupropion for the treatment of methamphetamine dependence. Drug Alcohol Dependence. 2008;96(3):222-232. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.010

38. Trivedi MH, Walker R, Ling W, et al. Bupropion and naltrexone in methamphetamine use disorder. N Engl J Med. 2021;384(2):140-153. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2020214

39. Jayaram-Lindström N, Hammarberg A, Beck O, et al. Naltrexone for the treatment of amphetamine dependence: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165(11):1442-1448. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08020304

40. Schmitz JM, Stotts AL, Rhoades HM, et al. Naltrexone and relapse prevention treatment for cocaine-dependent patients. Addict Behav. 2001;26(2):167-180. doi:10.1016/s0306-4603(00)00098-8

41. Oslin DW, Pettinati HM, Volpicelli JR, et al. The effects of naltrexone on alcohol and cocaine use in dually addicted patients. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1999;16(2):163-167. doi:10.1016/s0740-5472(98)00039-7

42. Johnson BA, Ait-Daoud N, Wang XQ, et al. Topiramate for the treatment of cocaine addiction: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2013;70(12):1338-1346. doi:10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.2295

43. Kampman KM, Pettinati H, Lynch KG, et al. A pilot trial of topiramate for the treatment of cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Dependence. 2004;75(3):233-240. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.03.008

44. Elkashef A, Kahn R, Yu E, et al. Topiramate for the treatment of methamphetamine addiction: a multi-center placebo-controlled trial. Addiction. 2012;107(7):1297-1306. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03771.x

45. Hasin DS. US epidemiology of cannabis use and associated problems. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43(1):195-212.

46. Brezing CA, Levin FR. The current state of pharmacological treatments for cannabis use disorder and withdrawal. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2018;43(1):173-194. doi:10.1038/npp.2017.198

47. Bahji A, Meyyappan AC, Hawken ER, et al. Pharmacotherapies for cannabis use disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Intl J Drug Policy. 2021;97:103295. doi:10.1016/j.drugpo.2021.103295

48. Gray KM, Carpenter MJ, Baker NL, et al. A double-blind randomized controlled trial of N-acetylcysteine in cannabis-dependent adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169(8):805-812. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12010055

49. Roten AT, Baker NL, Gray KM. Marijuana craving trajectories in an adolescent marijuana cessation pharmacotherapy trial. Addict Behav. 2013;38(3):1788-1791. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2012.11.003

50. McClure EA, Sonne SC, Winhusen T, et al. Achieving cannabis cessation—evaluating N-acetylcysteine treatment (ACCENT): design and implementation of a multi-site, randomized controlled study in the National Institute on Drug Abuse Clinical Trials Network. Contemp Clin Trials. 2014;39(2):211-223. doi:10.1016/j.cct.2014.08.011

51. Gray KM, Sonne SC, McClure EA, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled trial of N-acetylcysteine for cannabis use disorder in adults. Drug Alcohol Dependence. 2017;177:249-257. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2017.04.020

52. Mason BJ, Crean R, Goodell V, et al. A proof-of-concept randomized controlled study of gabapentin: effects on cannabis use, withdrawal and executive function deficits in cannabis-dependent adults. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2012;37(7):1689-1698. doi:10.1038/npp.2012.14

1. Wittich CM, Burkle CM, Lanier WL. Ten common questions (and their answers) about off-label drug use. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(10):982-990. doi:10.1016/j.mayocp.2012.04.017

2. Radley DC, Finkelstein SN, Stafford RS. Off-label prescribing among office-based physicians. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(9):1021-1026. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.9.1021

3. Wang J, Jiang F, Yating Y, et al. Off-label use of antipsychotic medications in psychiatric inpatients in China: a national real-world survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2021;21(1):375. doi:10.1186/s12888-021-03374-0

4. Chen H, Reeves JH, Fincham JE, et al. Off-label use of antidepressant, anticonvulsant, and antipsychotic medications among Georgia Medicaid enrollees in 2001. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67(6):972-982. doi:10.4088/jcp.v67n0615

5. Ventola CL. Off-label drug information: regulation, distribution, evaluation, and related controversies. P T. 2009;34(8):428-440.

6. Anton RF, Latham P, Voronin K, et al. Efficacy of gabapentin for the treatment of alcohol use disorder in patients with alcohol withdrawal symptoms: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(5):728-736. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.0249

7. Kranzler HR, Feinn R, Morris P, et al. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of gabapentin for treating alcohol use disorder. Addiction. 2019;114(9):1547-1555. doi:10.1111/add.14655

8. Mason BJ, Quello S, Goodell V. Gabapentin treatment for alcohol dependence: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(1):70-77. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.11950