User login

The patient has probably transitioned to the secondary progressive form of multiple sclerosis (MS). Four phenotypes have been identified in MS, with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) representing the most common and secondary progressive MS (SPMS) the second most common. RRMS is thought to begin as an inflammatory disease that over time becomes primarily neurodegenerative. The course of RRMS is marked by episodes of neurologic deficit followed by periods of remission which may be asymptomatic. When symptoms do not resolve — becoming fixed without remission — this is a sign of progression to SPMS. One in two RRMS patients will develop SPMS within 15 years of their diagnosis, leading to a progressive decrease of neurologic function and limitation of daily activities. Risk factors for developing SPMS include older age at onset of RRMS, longer duration of RRMS, and more cortical inflammatory lesions at baseline.

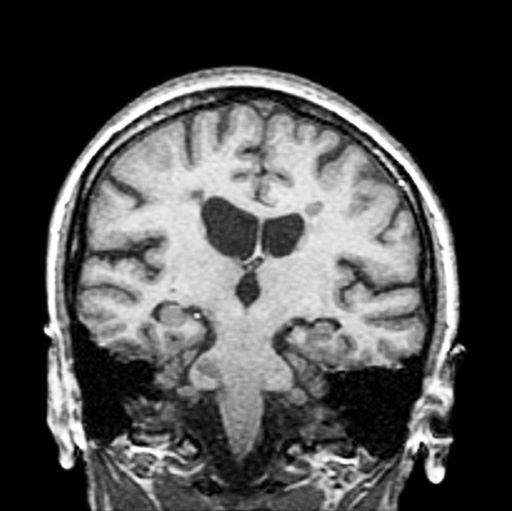

RRMS is diagnosed through clinical findings and laboratory results, the main approaches being MRI of the brain and spinal cord, and examination of cerebrospinal fluid. Neurologic symptoms must be consistent with those typically seen in MS, with deficit lasting for days to weeks. MRI is useful in monitoring disease progression (ie, new lesions that develop during relapses in RRMS). There are no universally accepted diagnostic criteria for SPMS, however. A patient usually can be diagnosed upon meeting these criteria: The patient was previously diagnosed with RRMS; the patient's symptoms are gradually worsening; this worsening is not tied to a relapse; and this worsening has been observed for 6 months or longer. Of note, SPMS' symptom-worsening characteristics can be subtle and difficult for patients to detect, and delays in diagnosis of up to several years are common.

Recognizing the onset of transition to SPMS is critical, as early initiation of therapy is thought to slow disease progression, the primary goal of treatment. In patients with SPMS, adhering to a holistic health program and managing comorbidities, especially vascular risk factors, can help preserve the health and functions of both the central nervous system and brain. Patients with SPMS who experience relapses or demonstrate new lesion formation as captured on MRI are thought to have active SPMS (aSPMS) and generally benefit from disease-modifying therapy (DMT). There is generally a transition period of about 5 years during which SPMS patients will still have a relapsing form of the disease, meaning that DMTs have proven to be effective in managing progressive MS should theoretically be beneficial for SPMS during this period. There are FDA-approved treatments for aSPMS, but off-label use is acceptable of those medications indicated for relapsing MS in those patients with evidence of relapses or new MRI activity.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme

The patient has probably transitioned to the secondary progressive form of multiple sclerosis (MS). Four phenotypes have been identified in MS, with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) representing the most common and secondary progressive MS (SPMS) the second most common. RRMS is thought to begin as an inflammatory disease that over time becomes primarily neurodegenerative. The course of RRMS is marked by episodes of neurologic deficit followed by periods of remission which may be asymptomatic. When symptoms do not resolve — becoming fixed without remission — this is a sign of progression to SPMS. One in two RRMS patients will develop SPMS within 15 years of their diagnosis, leading to a progressive decrease of neurologic function and limitation of daily activities. Risk factors for developing SPMS include older age at onset of RRMS, longer duration of RRMS, and more cortical inflammatory lesions at baseline.

RRMS is diagnosed through clinical findings and laboratory results, the main approaches being MRI of the brain and spinal cord, and examination of cerebrospinal fluid. Neurologic symptoms must be consistent with those typically seen in MS, with deficit lasting for days to weeks. MRI is useful in monitoring disease progression (ie, new lesions that develop during relapses in RRMS). There are no universally accepted diagnostic criteria for SPMS, however. A patient usually can be diagnosed upon meeting these criteria: The patient was previously diagnosed with RRMS; the patient's symptoms are gradually worsening; this worsening is not tied to a relapse; and this worsening has been observed for 6 months or longer. Of note, SPMS' symptom-worsening characteristics can be subtle and difficult for patients to detect, and delays in diagnosis of up to several years are common.

Recognizing the onset of transition to SPMS is critical, as early initiation of therapy is thought to slow disease progression, the primary goal of treatment. In patients with SPMS, adhering to a holistic health program and managing comorbidities, especially vascular risk factors, can help preserve the health and functions of both the central nervous system and brain. Patients with SPMS who experience relapses or demonstrate new lesion formation as captured on MRI are thought to have active SPMS (aSPMS) and generally benefit from disease-modifying therapy (DMT). There is generally a transition period of about 5 years during which SPMS patients will still have a relapsing form of the disease, meaning that DMTs have proven to be effective in managing progressive MS should theoretically be beneficial for SPMS during this period. There are FDA-approved treatments for aSPMS, but off-label use is acceptable of those medications indicated for relapsing MS in those patients with evidence of relapses or new MRI activity.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme

The patient has probably transitioned to the secondary progressive form of multiple sclerosis (MS). Four phenotypes have been identified in MS, with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) representing the most common and secondary progressive MS (SPMS) the second most common. RRMS is thought to begin as an inflammatory disease that over time becomes primarily neurodegenerative. The course of RRMS is marked by episodes of neurologic deficit followed by periods of remission which may be asymptomatic. When symptoms do not resolve — becoming fixed without remission — this is a sign of progression to SPMS. One in two RRMS patients will develop SPMS within 15 years of their diagnosis, leading to a progressive decrease of neurologic function and limitation of daily activities. Risk factors for developing SPMS include older age at onset of RRMS, longer duration of RRMS, and more cortical inflammatory lesions at baseline.

RRMS is diagnosed through clinical findings and laboratory results, the main approaches being MRI of the brain and spinal cord, and examination of cerebrospinal fluid. Neurologic symptoms must be consistent with those typically seen in MS, with deficit lasting for days to weeks. MRI is useful in monitoring disease progression (ie, new lesions that develop during relapses in RRMS). There are no universally accepted diagnostic criteria for SPMS, however. A patient usually can be diagnosed upon meeting these criteria: The patient was previously diagnosed with RRMS; the patient's symptoms are gradually worsening; this worsening is not tied to a relapse; and this worsening has been observed for 6 months or longer. Of note, SPMS' symptom-worsening characteristics can be subtle and difficult for patients to detect, and delays in diagnosis of up to several years are common.

Recognizing the onset of transition to SPMS is critical, as early initiation of therapy is thought to slow disease progression, the primary goal of treatment. In patients with SPMS, adhering to a holistic health program and managing comorbidities, especially vascular risk factors, can help preserve the health and functions of both the central nervous system and brain. Patients with SPMS who experience relapses or demonstrate new lesion formation as captured on MRI are thought to have active SPMS (aSPMS) and generally benefit from disease-modifying therapy (DMT). There is generally a transition period of about 5 years during which SPMS patients will still have a relapsing form of the disease, meaning that DMTs have proven to be effective in managing progressive MS should theoretically be beneficial for SPMS during this period. There are FDA-approved treatments for aSPMS, but off-label use is acceptable of those medications indicated for relapsing MS in those patients with evidence of relapses or new MRI activity.

Krupa Pandey, MD, Director, Multiple Sclerosis Center, Department of Neurology & Neuroscience Institute, Hackensack University Medical Center; Neurologist, Department of Neurology, Hackensack Meridian Health, Hackensack, NJ

Krupa Pandey, MD, has serve(d) as a speaker or a member of a speakers bureau for: Bristol-Myers Squibb; Biogen; Alexion; Genentech; Sanofi-Genzyme

A 51-year-old woman presents with a 3-year history of difficulty walking. She says that it is difficult to pinpoint when her walking problems began but reports that it has been gradual. She recalls about 10 years back a history of numbness and tingling in her hands that improved over the course of a few weeks without any further workup. She also recalls blurry vision and loss of color perception in her left eye 5 years ago while traveling for work. Because the symptoms resolved on their own over 6-8 weeks, she never sought care. MRI shows plaques of demyelination.