User login

From their days in training through their years of practice, family physicians emphasize preventive medicine. They counsel patients on diet and exercise, safe sex, and substance abuse; screen for early detection of cancer (eg, cervical, breast, colon, prostate); and administer chemo- and immunoprophylaxis (daily aspirin, vaccinations).

Though physicians are accustomed to caring for individuals, adopting a population perspective—considering the practice’s patient panel or even the larger community—is a logical extension of one’s daily practice. The public’s health benefits from parallel efforts in risk assessment and community-wide prevention. And, as we propose here, awareness of the similarities between the 2 areas of endeavor strengthens both.

Assessing risk for the individual

Risk factors are characteristics of a person that increase the likelihood of becoming diseased. Obvious risk factors include physical traits and laboratory values such as obesity, high cholesterol levels, and high blood pressure, and behaviors such as smoking and binge drinking. Other risk factors include demographic traits (age, race/ethnicity, gender, income), environmental influences (occupation, geographic location), and system issues (insurance status, usual source of care). Though risk factors may not cause disease, their presence can increase the probability that disease will eventually develop.

The degree to which a risk factor may influence disease development can be calculated with 2 measures.

Absolute risk is the difference between the incidence of disease in the group exposed to a risk factor and the incidence in the group not exposed to the factor.

Relative risk is the extent to which persons exposed to a risk are likely to develop the disease compared with those not exposed (see Calculating relative risk). Relative risk is more useful for judging a factor’s strength of disease causality, but it does not necessarily indicate the magnitude of risk for a population. With an uncommon disease, for instance, the relative risk of disease from an exposure may be large but the absolute risk may be small.

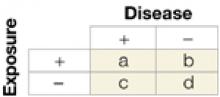

Relative risk—the likelihood that those exposed to a risk factor for disease will become diseased, compared with those not exposed to the factor—is calculated as follows:

Relative risk = (a/a+b) / (c/c+d)

The incidence of disease among those exposed (a divided by a+b) divided by the indicence of disease among those not exposed (c divided by c+d).

For more on relative risk, see “Relative risks and odds ratios: What’s the difference?,” in the February 2004 JFP.

Assessing risk for a population

Just as absolute and relative risk help quantify an individual’s susceptibility to disease, the population attributable risk helps gauge the level of risk to a community. The calculation takes into account disease incidence as well as how often the population is exposed to a related risk factor. This measure can be particularly influential in health policy decisions such as how to spend scarce resources—illustrated in the following example.2

Individual and population risks are determined in part by the prevalence of a risk factor. Consider the risk of death in the case of hypertension. For an individual, the risk of death is greater with severe hypertension than with mild hypertension. However, mild hypertension is quite common; severe hypertension is not. Therefore, the population attributable risk of hypertension (the number of extra deaths in the population attributable to hypertension) is greater for those with mild hypertension, even though the risk to an individual is greatest when hypertension is severe. This suggests that more lives can be saved by treating lots of people who have mild hypertension than by treating the much smaller number of people with severe hypertension—a concept called the “prevention paradox,” and one that underlies a number of national prevention efforts.

Synergies between individual and community prevention

Individual and community prevention strategies both have merit. For example, public health smoking cessation campaigns have been effective at the population level. At the same time, physician efforts to promote smoking cessation through office counseling sessions are effective with individuals. Individual physician efforts become population efforts if thousands of physicians each day provide cessation counseling to their patients. Public health campaigns help accomplish this by reinforcing the importance of cessation efforts including those delivered by practicing physicians.

Another excellent example of this type of reinforcing synergy is the work of the past decade to address hyperlipidemia as a risk factor for heart disease. In this effort, physician screening and treatment of patients has been both promoted and complemented by national media campaigns, local health fairs, and ongoing research, to the point where many individuals now are familiar with cholesterol and want to know their own lipid values.

Drawing on both arenas to prioritize prevention strategies

The federal government has supported the development of several types of evidence-based prevention guidelines. Family physicians are familiar with the US Preventive Service Task Force Guide to Clinical Preventive Services,3 but may be less familiar with the more recently developed Guide to Community Preventive Services.4 For a comprehensive continuum of preventive care, both guides can be used in combination. Using both sets of recommendations can help physicians to prioritize prevention strategies for individuals, office patient populations, and communities.

The Community Guide is a federally sponsored initiative producing evidenced-based recommendations for health promotion and disease prevention from a population-based perspective sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Table 1). Like the Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, the independent task force that oversees the Community Guide develops evidence-based reviews of potential interventions and translates the findings into recommendations that can be used by policy makers, public health entities, and health systems.

TABLE 1

Topics covered in the Guide to Community Preventive Services

|

Actionable recommendations for practitioners

Though the Community Guide takes a population-based approach to prevention (eg, recommendations for policy strategies, mass media campaigns, and school health programs), a number of its recommendations focus on the health care system and are directly applicable to practicing family physicians. For instance:

- Vaccination: a section on provider-based interventions such as reminder systems, standing orders for adults, and provider feedback strategies

- Diabetes: a section on disease management strategies

- Tobacco: a section on improving the delivery of cessation services

- Cancer: a section on improving screening for specific diseases.

The topic reviews grade the strength of each intervention (strong evidence, sufficient evidence, or insufficient evidence), provide a 1-page summary of the recommendations, and have links to longer papers that review the specific evidence.

Complementary web support

The website also includes an excellent 2-page summary of types of activities family doctors can undertake, with links to specific directions for implementing prevention activities. Included are patient and provider reminder systems, disease and case management, and use of standing orders.4

The recommendations in both the Clinical and Community Guides that address common conditions provide especially strong “roadmaps” for focusing on and addressing health promotion and disease prevention. By using both guides, physicians can develop a range of effective, evidence-based approaches for practice. For example, Table 2 presents evidence-based recommendations concerning smoking. These recommendations fall across a range of preventive interventions.

Producing successful initiatives

Using the guides as a reference, the family physician could initiate screening of patients for smoking status in the practice and then implement one or more of the recommended strategies listed in Table 2. Possibilities include adding a provider reminder system, delivering brief counseling to quit smoking, prescribing cessation medications, and coupling these efforts with advocacy for development of a media campaign in the community. Family physicians who undertake community prevention efforts outside the office setting are likely to improve their success by partnering with other community health and social service professionals to implement agreed upon prevention interventions.5

As more topics are developed for the Community Guide, family physicians will likely find more reasons to refer to it as a companion to the Clinical Guide. Using the 2 together will enhance the benefit gained from using each alone in a way that is analogous to the added health benefits obtained when the traditional health care system works more closely with the public health system.

TABLE 2

Intervention strategies in the clinical and community guides

| Intervention strategy recommendation | Where it’s found | Where it’s to be used |

|---|---|---|

| Screening patients for tobacco use | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Provider gives brief advise to quit to patients who use tobacco | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Provider counseling to patients on tobacco cessation | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Self-help education materials for patients who use tobacco | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Pharmacologic treatment for tobacco and dependence | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Provider reminder systems | Community Guide | Office |

| Multicomponent clinical program (provider reminder + education) | Community Guide | Office |

| Patient-oriented interventions (telephone support; sliding fee scale) | Community Guide | Office |

| Policies, regulations, and laws (smoking ban and restrictions) | Community Guide | Community |

| Mass media campaigns | Community Guide | Community |

| Sources: Adapted from USPSTF, Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, 19963; | ||

| USPSTF, Guide to Community Preventive Services, 2000.4 | ||

Correspondence

Eric Henley, MD, MPH, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Turabian JL, Perez-Franco B. Cual es el sentido de la educacion para la salud y las actividades “communitaria” en atencion primaria? Aten Primaria. 1998;22:662-666.

2. Fletcher R, Fletcher S, Wagner E. Clinical Epidemiology: The Essentials. Philadelphia, Pa: Williams and Wilkins; 1996.

3. US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. Available at: www.ahcpr.gov/clinic/cpsix.htm

4. US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Community Preventive Services. Available at: www.thecommunityguide.org.

5. Peters K, Elster A. Population based medicine: Roadmaps to clinical practice. Chicago, Ill: American Medical Association, 2002.

From their days in training through their years of practice, family physicians emphasize preventive medicine. They counsel patients on diet and exercise, safe sex, and substance abuse; screen for early detection of cancer (eg, cervical, breast, colon, prostate); and administer chemo- and immunoprophylaxis (daily aspirin, vaccinations).

Though physicians are accustomed to caring for individuals, adopting a population perspective—considering the practice’s patient panel or even the larger community—is a logical extension of one’s daily practice. The public’s health benefits from parallel efforts in risk assessment and community-wide prevention. And, as we propose here, awareness of the similarities between the 2 areas of endeavor strengthens both.

Assessing risk for the individual

Risk factors are characteristics of a person that increase the likelihood of becoming diseased. Obvious risk factors include physical traits and laboratory values such as obesity, high cholesterol levels, and high blood pressure, and behaviors such as smoking and binge drinking. Other risk factors include demographic traits (age, race/ethnicity, gender, income), environmental influences (occupation, geographic location), and system issues (insurance status, usual source of care). Though risk factors may not cause disease, their presence can increase the probability that disease will eventually develop.

The degree to which a risk factor may influence disease development can be calculated with 2 measures.

Absolute risk is the difference between the incidence of disease in the group exposed to a risk factor and the incidence in the group not exposed to the factor.

Relative risk is the extent to which persons exposed to a risk are likely to develop the disease compared with those not exposed (see Calculating relative risk). Relative risk is more useful for judging a factor’s strength of disease causality, but it does not necessarily indicate the magnitude of risk for a population. With an uncommon disease, for instance, the relative risk of disease from an exposure may be large but the absolute risk may be small.

Relative risk—the likelihood that those exposed to a risk factor for disease will become diseased, compared with those not exposed to the factor—is calculated as follows:

Relative risk = (a/a+b) / (c/c+d)

The incidence of disease among those exposed (a divided by a+b) divided by the indicence of disease among those not exposed (c divided by c+d).

For more on relative risk, see “Relative risks and odds ratios: What’s the difference?,” in the February 2004 JFP.

Assessing risk for a population

Just as absolute and relative risk help quantify an individual’s susceptibility to disease, the population attributable risk helps gauge the level of risk to a community. The calculation takes into account disease incidence as well as how often the population is exposed to a related risk factor. This measure can be particularly influential in health policy decisions such as how to spend scarce resources—illustrated in the following example.2

Individual and population risks are determined in part by the prevalence of a risk factor. Consider the risk of death in the case of hypertension. For an individual, the risk of death is greater with severe hypertension than with mild hypertension. However, mild hypertension is quite common; severe hypertension is not. Therefore, the population attributable risk of hypertension (the number of extra deaths in the population attributable to hypertension) is greater for those with mild hypertension, even though the risk to an individual is greatest when hypertension is severe. This suggests that more lives can be saved by treating lots of people who have mild hypertension than by treating the much smaller number of people with severe hypertension—a concept called the “prevention paradox,” and one that underlies a number of national prevention efforts.

Synergies between individual and community prevention

Individual and community prevention strategies both have merit. For example, public health smoking cessation campaigns have been effective at the population level. At the same time, physician efforts to promote smoking cessation through office counseling sessions are effective with individuals. Individual physician efforts become population efforts if thousands of physicians each day provide cessation counseling to their patients. Public health campaigns help accomplish this by reinforcing the importance of cessation efforts including those delivered by practicing physicians.

Another excellent example of this type of reinforcing synergy is the work of the past decade to address hyperlipidemia as a risk factor for heart disease. In this effort, physician screening and treatment of patients has been both promoted and complemented by national media campaigns, local health fairs, and ongoing research, to the point where many individuals now are familiar with cholesterol and want to know their own lipid values.

Drawing on both arenas to prioritize prevention strategies

The federal government has supported the development of several types of evidence-based prevention guidelines. Family physicians are familiar with the US Preventive Service Task Force Guide to Clinical Preventive Services,3 but may be less familiar with the more recently developed Guide to Community Preventive Services.4 For a comprehensive continuum of preventive care, both guides can be used in combination. Using both sets of recommendations can help physicians to prioritize prevention strategies for individuals, office patient populations, and communities.

The Community Guide is a federally sponsored initiative producing evidenced-based recommendations for health promotion and disease prevention from a population-based perspective sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Table 1). Like the Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, the independent task force that oversees the Community Guide develops evidence-based reviews of potential interventions and translates the findings into recommendations that can be used by policy makers, public health entities, and health systems.

TABLE 1

Topics covered in the Guide to Community Preventive Services

|

Actionable recommendations for practitioners

Though the Community Guide takes a population-based approach to prevention (eg, recommendations for policy strategies, mass media campaigns, and school health programs), a number of its recommendations focus on the health care system and are directly applicable to practicing family physicians. For instance:

- Vaccination: a section on provider-based interventions such as reminder systems, standing orders for adults, and provider feedback strategies

- Diabetes: a section on disease management strategies

- Tobacco: a section on improving the delivery of cessation services

- Cancer: a section on improving screening for specific diseases.

The topic reviews grade the strength of each intervention (strong evidence, sufficient evidence, or insufficient evidence), provide a 1-page summary of the recommendations, and have links to longer papers that review the specific evidence.

Complementary web support

The website also includes an excellent 2-page summary of types of activities family doctors can undertake, with links to specific directions for implementing prevention activities. Included are patient and provider reminder systems, disease and case management, and use of standing orders.4

The recommendations in both the Clinical and Community Guides that address common conditions provide especially strong “roadmaps” for focusing on and addressing health promotion and disease prevention. By using both guides, physicians can develop a range of effective, evidence-based approaches for practice. For example, Table 2 presents evidence-based recommendations concerning smoking. These recommendations fall across a range of preventive interventions.

Producing successful initiatives

Using the guides as a reference, the family physician could initiate screening of patients for smoking status in the practice and then implement one or more of the recommended strategies listed in Table 2. Possibilities include adding a provider reminder system, delivering brief counseling to quit smoking, prescribing cessation medications, and coupling these efforts with advocacy for development of a media campaign in the community. Family physicians who undertake community prevention efforts outside the office setting are likely to improve their success by partnering with other community health and social service professionals to implement agreed upon prevention interventions.5

As more topics are developed for the Community Guide, family physicians will likely find more reasons to refer to it as a companion to the Clinical Guide. Using the 2 together will enhance the benefit gained from using each alone in a way that is analogous to the added health benefits obtained when the traditional health care system works more closely with the public health system.

TABLE 2

Intervention strategies in the clinical and community guides

| Intervention strategy recommendation | Where it’s found | Where it’s to be used |

|---|---|---|

| Screening patients for tobacco use | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Provider gives brief advise to quit to patients who use tobacco | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Provider counseling to patients on tobacco cessation | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Self-help education materials for patients who use tobacco | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Pharmacologic treatment for tobacco and dependence | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Provider reminder systems | Community Guide | Office |

| Multicomponent clinical program (provider reminder + education) | Community Guide | Office |

| Patient-oriented interventions (telephone support; sliding fee scale) | Community Guide | Office |

| Policies, regulations, and laws (smoking ban and restrictions) | Community Guide | Community |

| Mass media campaigns | Community Guide | Community |

| Sources: Adapted from USPSTF, Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, 19963; | ||

| USPSTF, Guide to Community Preventive Services, 2000.4 | ||

Correspondence

Eric Henley, MD, MPH, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107. E-mail: [email protected].

From their days in training through their years of practice, family physicians emphasize preventive medicine. They counsel patients on diet and exercise, safe sex, and substance abuse; screen for early detection of cancer (eg, cervical, breast, colon, prostate); and administer chemo- and immunoprophylaxis (daily aspirin, vaccinations).

Though physicians are accustomed to caring for individuals, adopting a population perspective—considering the practice’s patient panel or even the larger community—is a logical extension of one’s daily practice. The public’s health benefits from parallel efforts in risk assessment and community-wide prevention. And, as we propose here, awareness of the similarities between the 2 areas of endeavor strengthens both.

Assessing risk for the individual

Risk factors are characteristics of a person that increase the likelihood of becoming diseased. Obvious risk factors include physical traits and laboratory values such as obesity, high cholesterol levels, and high blood pressure, and behaviors such as smoking and binge drinking. Other risk factors include demographic traits (age, race/ethnicity, gender, income), environmental influences (occupation, geographic location), and system issues (insurance status, usual source of care). Though risk factors may not cause disease, their presence can increase the probability that disease will eventually develop.

The degree to which a risk factor may influence disease development can be calculated with 2 measures.

Absolute risk is the difference between the incidence of disease in the group exposed to a risk factor and the incidence in the group not exposed to the factor.

Relative risk is the extent to which persons exposed to a risk are likely to develop the disease compared with those not exposed (see Calculating relative risk). Relative risk is more useful for judging a factor’s strength of disease causality, but it does not necessarily indicate the magnitude of risk for a population. With an uncommon disease, for instance, the relative risk of disease from an exposure may be large but the absolute risk may be small.

Relative risk—the likelihood that those exposed to a risk factor for disease will become diseased, compared with those not exposed to the factor—is calculated as follows:

Relative risk = (a/a+b) / (c/c+d)

The incidence of disease among those exposed (a divided by a+b) divided by the indicence of disease among those not exposed (c divided by c+d).

For more on relative risk, see “Relative risks and odds ratios: What’s the difference?,” in the February 2004 JFP.

Assessing risk for a population

Just as absolute and relative risk help quantify an individual’s susceptibility to disease, the population attributable risk helps gauge the level of risk to a community. The calculation takes into account disease incidence as well as how often the population is exposed to a related risk factor. This measure can be particularly influential in health policy decisions such as how to spend scarce resources—illustrated in the following example.2

Individual and population risks are determined in part by the prevalence of a risk factor. Consider the risk of death in the case of hypertension. For an individual, the risk of death is greater with severe hypertension than with mild hypertension. However, mild hypertension is quite common; severe hypertension is not. Therefore, the population attributable risk of hypertension (the number of extra deaths in the population attributable to hypertension) is greater for those with mild hypertension, even though the risk to an individual is greatest when hypertension is severe. This suggests that more lives can be saved by treating lots of people who have mild hypertension than by treating the much smaller number of people with severe hypertension—a concept called the “prevention paradox,” and one that underlies a number of national prevention efforts.

Synergies between individual and community prevention

Individual and community prevention strategies both have merit. For example, public health smoking cessation campaigns have been effective at the population level. At the same time, physician efforts to promote smoking cessation through office counseling sessions are effective with individuals. Individual physician efforts become population efforts if thousands of physicians each day provide cessation counseling to their patients. Public health campaigns help accomplish this by reinforcing the importance of cessation efforts including those delivered by practicing physicians.

Another excellent example of this type of reinforcing synergy is the work of the past decade to address hyperlipidemia as a risk factor for heart disease. In this effort, physician screening and treatment of patients has been both promoted and complemented by national media campaigns, local health fairs, and ongoing research, to the point where many individuals now are familiar with cholesterol and want to know their own lipid values.

Drawing on both arenas to prioritize prevention strategies

The federal government has supported the development of several types of evidence-based prevention guidelines. Family physicians are familiar with the US Preventive Service Task Force Guide to Clinical Preventive Services,3 but may be less familiar with the more recently developed Guide to Community Preventive Services.4 For a comprehensive continuum of preventive care, both guides can be used in combination. Using both sets of recommendations can help physicians to prioritize prevention strategies for individuals, office patient populations, and communities.

The Community Guide is a federally sponsored initiative producing evidenced-based recommendations for health promotion and disease prevention from a population-based perspective sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Table 1). Like the Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, the independent task force that oversees the Community Guide develops evidence-based reviews of potential interventions and translates the findings into recommendations that can be used by policy makers, public health entities, and health systems.

TABLE 1

Topics covered in the Guide to Community Preventive Services

|

Actionable recommendations for practitioners

Though the Community Guide takes a population-based approach to prevention (eg, recommendations for policy strategies, mass media campaigns, and school health programs), a number of its recommendations focus on the health care system and are directly applicable to practicing family physicians. For instance:

- Vaccination: a section on provider-based interventions such as reminder systems, standing orders for adults, and provider feedback strategies

- Diabetes: a section on disease management strategies

- Tobacco: a section on improving the delivery of cessation services

- Cancer: a section on improving screening for specific diseases.

The topic reviews grade the strength of each intervention (strong evidence, sufficient evidence, or insufficient evidence), provide a 1-page summary of the recommendations, and have links to longer papers that review the specific evidence.

Complementary web support

The website also includes an excellent 2-page summary of types of activities family doctors can undertake, with links to specific directions for implementing prevention activities. Included are patient and provider reminder systems, disease and case management, and use of standing orders.4

The recommendations in both the Clinical and Community Guides that address common conditions provide especially strong “roadmaps” for focusing on and addressing health promotion and disease prevention. By using both guides, physicians can develop a range of effective, evidence-based approaches for practice. For example, Table 2 presents evidence-based recommendations concerning smoking. These recommendations fall across a range of preventive interventions.

Producing successful initiatives

Using the guides as a reference, the family physician could initiate screening of patients for smoking status in the practice and then implement one or more of the recommended strategies listed in Table 2. Possibilities include adding a provider reminder system, delivering brief counseling to quit smoking, prescribing cessation medications, and coupling these efforts with advocacy for development of a media campaign in the community. Family physicians who undertake community prevention efforts outside the office setting are likely to improve their success by partnering with other community health and social service professionals to implement agreed upon prevention interventions.5

As more topics are developed for the Community Guide, family physicians will likely find more reasons to refer to it as a companion to the Clinical Guide. Using the 2 together will enhance the benefit gained from using each alone in a way that is analogous to the added health benefits obtained when the traditional health care system works more closely with the public health system.

TABLE 2

Intervention strategies in the clinical and community guides

| Intervention strategy recommendation | Where it’s found | Where it’s to be used |

|---|---|---|

| Screening patients for tobacco use | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Provider gives brief advise to quit to patients who use tobacco | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Provider counseling to patients on tobacco cessation | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Self-help education materials for patients who use tobacco | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Pharmacologic treatment for tobacco and dependence | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Provider reminder systems | Community Guide | Office |

| Multicomponent clinical program (provider reminder + education) | Community Guide | Office |

| Patient-oriented interventions (telephone support; sliding fee scale) | Community Guide | Office |

| Policies, regulations, and laws (smoking ban and restrictions) | Community Guide | Community |

| Mass media campaigns | Community Guide | Community |

| Sources: Adapted from USPSTF, Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, 19963; | ||

| USPSTF, Guide to Community Preventive Services, 2000.4 | ||

Correspondence

Eric Henley, MD, MPH, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Turabian JL, Perez-Franco B. Cual es el sentido de la educacion para la salud y las actividades “communitaria” en atencion primaria? Aten Primaria. 1998;22:662-666.

2. Fletcher R, Fletcher S, Wagner E. Clinical Epidemiology: The Essentials. Philadelphia, Pa: Williams and Wilkins; 1996.

3. US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. Available at: www.ahcpr.gov/clinic/cpsix.htm

4. US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Community Preventive Services. Available at: www.thecommunityguide.org.

5. Peters K, Elster A. Population based medicine: Roadmaps to clinical practice. Chicago, Ill: American Medical Association, 2002.

1. Turabian JL, Perez-Franco B. Cual es el sentido de la educacion para la salud y las actividades “communitaria” en atencion primaria? Aten Primaria. 1998;22:662-666.

2. Fletcher R, Fletcher S, Wagner E. Clinical Epidemiology: The Essentials. Philadelphia, Pa: Williams and Wilkins; 1996.

3. US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. Available at: www.ahcpr.gov/clinic/cpsix.htm

4. US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Community Preventive Services. Available at: www.thecommunityguide.org.

5. Peters K, Elster A. Population based medicine: Roadmaps to clinical practice. Chicago, Ill: American Medical Association, 2002.