User login

Acting on synergies between clinic and community strategies to improve preventive medicine

From their days in training through their years of practice, family physicians emphasize preventive medicine. They counsel patients on diet and exercise, safe sex, and substance abuse; screen for early detection of cancer (eg, cervical, breast, colon, prostate); and administer chemo- and immunoprophylaxis (daily aspirin, vaccinations).

Though physicians are accustomed to caring for individuals, adopting a population perspective—considering the practice’s patient panel or even the larger community—is a logical extension of one’s daily practice. The public’s health benefits from parallel efforts in risk assessment and community-wide prevention. And, as we propose here, awareness of the similarities between the 2 areas of endeavor strengthens both.

Assessing risk for the individual

Risk factors are characteristics of a person that increase the likelihood of becoming diseased. Obvious risk factors include physical traits and laboratory values such as obesity, high cholesterol levels, and high blood pressure, and behaviors such as smoking and binge drinking. Other risk factors include demographic traits (age, race/ethnicity, gender, income), environmental influences (occupation, geographic location), and system issues (insurance status, usual source of care). Though risk factors may not cause disease, their presence can increase the probability that disease will eventually develop.

The degree to which a risk factor may influence disease development can be calculated with 2 measures.

Absolute risk is the difference between the incidence of disease in the group exposed to a risk factor and the incidence in the group not exposed to the factor.

Relative risk is the extent to which persons exposed to a risk are likely to develop the disease compared with those not exposed (see Calculating relative risk). Relative risk is more useful for judging a factor’s strength of disease causality, but it does not necessarily indicate the magnitude of risk for a population. With an uncommon disease, for instance, the relative risk of disease from an exposure may be large but the absolute risk may be small.

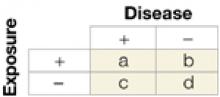

Relative risk—the likelihood that those exposed to a risk factor for disease will become diseased, compared with those not exposed to the factor—is calculated as follows:

Relative risk = (a/a+b) / (c/c+d)

The incidence of disease among those exposed (a divided by a+b) divided by the indicence of disease among those not exposed (c divided by c+d).

For more on relative risk, see “Relative risks and odds ratios: What’s the difference?,” in the February 2004 JFP.

Assessing risk for a population

Just as absolute and relative risk help quantify an individual’s susceptibility to disease, the population attributable risk helps gauge the level of risk to a community. The calculation takes into account disease incidence as well as how often the population is exposed to a related risk factor. This measure can be particularly influential in health policy decisions such as how to spend scarce resources—illustrated in the following example.2

Individual and population risks are determined in part by the prevalence of a risk factor. Consider the risk of death in the case of hypertension. For an individual, the risk of death is greater with severe hypertension than with mild hypertension. However, mild hypertension is quite common; severe hypertension is not. Therefore, the population attributable risk of hypertension (the number of extra deaths in the population attributable to hypertension) is greater for those with mild hypertension, even though the risk to an individual is greatest when hypertension is severe. This suggests that more lives can be saved by treating lots of people who have mild hypertension than by treating the much smaller number of people with severe hypertension—a concept called the “prevention paradox,” and one that underlies a number of national prevention efforts.

Synergies between individual and community prevention

Individual and community prevention strategies both have merit. For example, public health smoking cessation campaigns have been effective at the population level. At the same time, physician efforts to promote smoking cessation through office counseling sessions are effective with individuals. Individual physician efforts become population efforts if thousands of physicians each day provide cessation counseling to their patients. Public health campaigns help accomplish this by reinforcing the importance of cessation efforts including those delivered by practicing physicians.

Another excellent example of this type of reinforcing synergy is the work of the past decade to address hyperlipidemia as a risk factor for heart disease. In this effort, physician screening and treatment of patients has been both promoted and complemented by national media campaigns, local health fairs, and ongoing research, to the point where many individuals now are familiar with cholesterol and want to know their own lipid values.

Drawing on both arenas to prioritize prevention strategies

The federal government has supported the development of several types of evidence-based prevention guidelines. Family physicians are familiar with the US Preventive Service Task Force Guide to Clinical Preventive Services,3 but may be less familiar with the more recently developed Guide to Community Preventive Services.4 For a comprehensive continuum of preventive care, both guides can be used in combination. Using both sets of recommendations can help physicians to prioritize prevention strategies for individuals, office patient populations, and communities.

The Community Guide is a federally sponsored initiative producing evidenced-based recommendations for health promotion and disease prevention from a population-based perspective sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Table 1). Like the Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, the independent task force that oversees the Community Guide develops evidence-based reviews of potential interventions and translates the findings into recommendations that can be used by policy makers, public health entities, and health systems.

TABLE 1

Topics covered in the Guide to Community Preventive Services

|

Actionable recommendations for practitioners

Though the Community Guide takes a population-based approach to prevention (eg, recommendations for policy strategies, mass media campaigns, and school health programs), a number of its recommendations focus on the health care system and are directly applicable to practicing family physicians. For instance:

- Vaccination: a section on provider-based interventions such as reminder systems, standing orders for adults, and provider feedback strategies

- Diabetes: a section on disease management strategies

- Tobacco: a section on improving the delivery of cessation services

- Cancer: a section on improving screening for specific diseases.

The topic reviews grade the strength of each intervention (strong evidence, sufficient evidence, or insufficient evidence), provide a 1-page summary of the recommendations, and have links to longer papers that review the specific evidence.

Complementary web support

The website also includes an excellent 2-page summary of types of activities family doctors can undertake, with links to specific directions for implementing prevention activities. Included are patient and provider reminder systems, disease and case management, and use of standing orders.4

The recommendations in both the Clinical and Community Guides that address common conditions provide especially strong “roadmaps” for focusing on and addressing health promotion and disease prevention. By using both guides, physicians can develop a range of effective, evidence-based approaches for practice. For example, Table 2 presents evidence-based recommendations concerning smoking. These recommendations fall across a range of preventive interventions.

Producing successful initiatives

Using the guides as a reference, the family physician could initiate screening of patients for smoking status in the practice and then implement one or more of the recommended strategies listed in Table 2. Possibilities include adding a provider reminder system, delivering brief counseling to quit smoking, prescribing cessation medications, and coupling these efforts with advocacy for development of a media campaign in the community. Family physicians who undertake community prevention efforts outside the office setting are likely to improve their success by partnering with other community health and social service professionals to implement agreed upon prevention interventions.5

As more topics are developed for the Community Guide, family physicians will likely find more reasons to refer to it as a companion to the Clinical Guide. Using the 2 together will enhance the benefit gained from using each alone in a way that is analogous to the added health benefits obtained when the traditional health care system works more closely with the public health system.

TABLE 2

Intervention strategies in the clinical and community guides

| Intervention strategy recommendation | Where it’s found | Where it’s to be used |

|---|---|---|

| Screening patients for tobacco use | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Provider gives brief advise to quit to patients who use tobacco | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Provider counseling to patients on tobacco cessation | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Self-help education materials for patients who use tobacco | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Pharmacologic treatment for tobacco and dependence | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Provider reminder systems | Community Guide | Office |

| Multicomponent clinical program (provider reminder + education) | Community Guide | Office |

| Patient-oriented interventions (telephone support; sliding fee scale) | Community Guide | Office |

| Policies, regulations, and laws (smoking ban and restrictions) | Community Guide | Community |

| Mass media campaigns | Community Guide | Community |

| Sources: Adapted from USPSTF, Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, 19963; | ||

| USPSTF, Guide to Community Preventive Services, 2000.4 | ||

Correspondence

Eric Henley, MD, MPH, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Turabian JL, Perez-Franco B. Cual es el sentido de la educacion para la salud y las actividades “communitaria” en atencion primaria? Aten Primaria. 1998;22:662-666.

2. Fletcher R, Fletcher S, Wagner E. Clinical Epidemiology: The Essentials. Philadelphia, Pa: Williams and Wilkins; 1996.

3. US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. Available at: www.ahcpr.gov/clinic/cpsix.htm

4. US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Community Preventive Services. Available at: www.thecommunityguide.org.

5. Peters K, Elster A. Population based medicine: Roadmaps to clinical practice. Chicago, Ill: American Medical Association, 2002.

From their days in training through their years of practice, family physicians emphasize preventive medicine. They counsel patients on diet and exercise, safe sex, and substance abuse; screen for early detection of cancer (eg, cervical, breast, colon, prostate); and administer chemo- and immunoprophylaxis (daily aspirin, vaccinations).

Though physicians are accustomed to caring for individuals, adopting a population perspective—considering the practice’s patient panel or even the larger community—is a logical extension of one’s daily practice. The public’s health benefits from parallel efforts in risk assessment and community-wide prevention. And, as we propose here, awareness of the similarities between the 2 areas of endeavor strengthens both.

Assessing risk for the individual

Risk factors are characteristics of a person that increase the likelihood of becoming diseased. Obvious risk factors include physical traits and laboratory values such as obesity, high cholesterol levels, and high blood pressure, and behaviors such as smoking and binge drinking. Other risk factors include demographic traits (age, race/ethnicity, gender, income), environmental influences (occupation, geographic location), and system issues (insurance status, usual source of care). Though risk factors may not cause disease, their presence can increase the probability that disease will eventually develop.

The degree to which a risk factor may influence disease development can be calculated with 2 measures.

Absolute risk is the difference between the incidence of disease in the group exposed to a risk factor and the incidence in the group not exposed to the factor.

Relative risk is the extent to which persons exposed to a risk are likely to develop the disease compared with those not exposed (see Calculating relative risk). Relative risk is more useful for judging a factor’s strength of disease causality, but it does not necessarily indicate the magnitude of risk for a population. With an uncommon disease, for instance, the relative risk of disease from an exposure may be large but the absolute risk may be small.

Relative risk—the likelihood that those exposed to a risk factor for disease will become diseased, compared with those not exposed to the factor—is calculated as follows:

Relative risk = (a/a+b) / (c/c+d)

The incidence of disease among those exposed (a divided by a+b) divided by the indicence of disease among those not exposed (c divided by c+d).

For more on relative risk, see “Relative risks and odds ratios: What’s the difference?,” in the February 2004 JFP.

Assessing risk for a population

Just as absolute and relative risk help quantify an individual’s susceptibility to disease, the population attributable risk helps gauge the level of risk to a community. The calculation takes into account disease incidence as well as how often the population is exposed to a related risk factor. This measure can be particularly influential in health policy decisions such as how to spend scarce resources—illustrated in the following example.2

Individual and population risks are determined in part by the prevalence of a risk factor. Consider the risk of death in the case of hypertension. For an individual, the risk of death is greater with severe hypertension than with mild hypertension. However, mild hypertension is quite common; severe hypertension is not. Therefore, the population attributable risk of hypertension (the number of extra deaths in the population attributable to hypertension) is greater for those with mild hypertension, even though the risk to an individual is greatest when hypertension is severe. This suggests that more lives can be saved by treating lots of people who have mild hypertension than by treating the much smaller number of people with severe hypertension—a concept called the “prevention paradox,” and one that underlies a number of national prevention efforts.

Synergies between individual and community prevention

Individual and community prevention strategies both have merit. For example, public health smoking cessation campaigns have been effective at the population level. At the same time, physician efforts to promote smoking cessation through office counseling sessions are effective with individuals. Individual physician efforts become population efforts if thousands of physicians each day provide cessation counseling to their patients. Public health campaigns help accomplish this by reinforcing the importance of cessation efforts including those delivered by practicing physicians.

Another excellent example of this type of reinforcing synergy is the work of the past decade to address hyperlipidemia as a risk factor for heart disease. In this effort, physician screening and treatment of patients has been both promoted and complemented by national media campaigns, local health fairs, and ongoing research, to the point where many individuals now are familiar with cholesterol and want to know their own lipid values.

Drawing on both arenas to prioritize prevention strategies

The federal government has supported the development of several types of evidence-based prevention guidelines. Family physicians are familiar with the US Preventive Service Task Force Guide to Clinical Preventive Services,3 but may be less familiar with the more recently developed Guide to Community Preventive Services.4 For a comprehensive continuum of preventive care, both guides can be used in combination. Using both sets of recommendations can help physicians to prioritize prevention strategies for individuals, office patient populations, and communities.

The Community Guide is a federally sponsored initiative producing evidenced-based recommendations for health promotion and disease prevention from a population-based perspective sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Table 1). Like the Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, the independent task force that oversees the Community Guide develops evidence-based reviews of potential interventions and translates the findings into recommendations that can be used by policy makers, public health entities, and health systems.

TABLE 1

Topics covered in the Guide to Community Preventive Services

|

Actionable recommendations for practitioners

Though the Community Guide takes a population-based approach to prevention (eg, recommendations for policy strategies, mass media campaigns, and school health programs), a number of its recommendations focus on the health care system and are directly applicable to practicing family physicians. For instance:

- Vaccination: a section on provider-based interventions such as reminder systems, standing orders for adults, and provider feedback strategies

- Diabetes: a section on disease management strategies

- Tobacco: a section on improving the delivery of cessation services

- Cancer: a section on improving screening for specific diseases.

The topic reviews grade the strength of each intervention (strong evidence, sufficient evidence, or insufficient evidence), provide a 1-page summary of the recommendations, and have links to longer papers that review the specific evidence.

Complementary web support

The website also includes an excellent 2-page summary of types of activities family doctors can undertake, with links to specific directions for implementing prevention activities. Included are patient and provider reminder systems, disease and case management, and use of standing orders.4

The recommendations in both the Clinical and Community Guides that address common conditions provide especially strong “roadmaps” for focusing on and addressing health promotion and disease prevention. By using both guides, physicians can develop a range of effective, evidence-based approaches for practice. For example, Table 2 presents evidence-based recommendations concerning smoking. These recommendations fall across a range of preventive interventions.

Producing successful initiatives

Using the guides as a reference, the family physician could initiate screening of patients for smoking status in the practice and then implement one or more of the recommended strategies listed in Table 2. Possibilities include adding a provider reminder system, delivering brief counseling to quit smoking, prescribing cessation medications, and coupling these efforts with advocacy for development of a media campaign in the community. Family physicians who undertake community prevention efforts outside the office setting are likely to improve their success by partnering with other community health and social service professionals to implement agreed upon prevention interventions.5

As more topics are developed for the Community Guide, family physicians will likely find more reasons to refer to it as a companion to the Clinical Guide. Using the 2 together will enhance the benefit gained from using each alone in a way that is analogous to the added health benefits obtained when the traditional health care system works more closely with the public health system.

TABLE 2

Intervention strategies in the clinical and community guides

| Intervention strategy recommendation | Where it’s found | Where it’s to be used |

|---|---|---|

| Screening patients for tobacco use | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Provider gives brief advise to quit to patients who use tobacco | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Provider counseling to patients on tobacco cessation | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Self-help education materials for patients who use tobacco | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Pharmacologic treatment for tobacco and dependence | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Provider reminder systems | Community Guide | Office |

| Multicomponent clinical program (provider reminder + education) | Community Guide | Office |

| Patient-oriented interventions (telephone support; sliding fee scale) | Community Guide | Office |

| Policies, regulations, and laws (smoking ban and restrictions) | Community Guide | Community |

| Mass media campaigns | Community Guide | Community |

| Sources: Adapted from USPSTF, Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, 19963; | ||

| USPSTF, Guide to Community Preventive Services, 2000.4 | ||

Correspondence

Eric Henley, MD, MPH, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107. E-mail: [email protected].

From their days in training through their years of practice, family physicians emphasize preventive medicine. They counsel patients on diet and exercise, safe sex, and substance abuse; screen for early detection of cancer (eg, cervical, breast, colon, prostate); and administer chemo- and immunoprophylaxis (daily aspirin, vaccinations).

Though physicians are accustomed to caring for individuals, adopting a population perspective—considering the practice’s patient panel or even the larger community—is a logical extension of one’s daily practice. The public’s health benefits from parallel efforts in risk assessment and community-wide prevention. And, as we propose here, awareness of the similarities between the 2 areas of endeavor strengthens both.

Assessing risk for the individual

Risk factors are characteristics of a person that increase the likelihood of becoming diseased. Obvious risk factors include physical traits and laboratory values such as obesity, high cholesterol levels, and high blood pressure, and behaviors such as smoking and binge drinking. Other risk factors include demographic traits (age, race/ethnicity, gender, income), environmental influences (occupation, geographic location), and system issues (insurance status, usual source of care). Though risk factors may not cause disease, their presence can increase the probability that disease will eventually develop.

The degree to which a risk factor may influence disease development can be calculated with 2 measures.

Absolute risk is the difference between the incidence of disease in the group exposed to a risk factor and the incidence in the group not exposed to the factor.

Relative risk is the extent to which persons exposed to a risk are likely to develop the disease compared with those not exposed (see Calculating relative risk). Relative risk is more useful for judging a factor’s strength of disease causality, but it does not necessarily indicate the magnitude of risk for a population. With an uncommon disease, for instance, the relative risk of disease from an exposure may be large but the absolute risk may be small.

Relative risk—the likelihood that those exposed to a risk factor for disease will become diseased, compared with those not exposed to the factor—is calculated as follows:

Relative risk = (a/a+b) / (c/c+d)

The incidence of disease among those exposed (a divided by a+b) divided by the indicence of disease among those not exposed (c divided by c+d).

For more on relative risk, see “Relative risks and odds ratios: What’s the difference?,” in the February 2004 JFP.

Assessing risk for a population

Just as absolute and relative risk help quantify an individual’s susceptibility to disease, the population attributable risk helps gauge the level of risk to a community. The calculation takes into account disease incidence as well as how often the population is exposed to a related risk factor. This measure can be particularly influential in health policy decisions such as how to spend scarce resources—illustrated in the following example.2

Individual and population risks are determined in part by the prevalence of a risk factor. Consider the risk of death in the case of hypertension. For an individual, the risk of death is greater with severe hypertension than with mild hypertension. However, mild hypertension is quite common; severe hypertension is not. Therefore, the population attributable risk of hypertension (the number of extra deaths in the population attributable to hypertension) is greater for those with mild hypertension, even though the risk to an individual is greatest when hypertension is severe. This suggests that more lives can be saved by treating lots of people who have mild hypertension than by treating the much smaller number of people with severe hypertension—a concept called the “prevention paradox,” and one that underlies a number of national prevention efforts.

Synergies between individual and community prevention

Individual and community prevention strategies both have merit. For example, public health smoking cessation campaigns have been effective at the population level. At the same time, physician efforts to promote smoking cessation through office counseling sessions are effective with individuals. Individual physician efforts become population efforts if thousands of physicians each day provide cessation counseling to their patients. Public health campaigns help accomplish this by reinforcing the importance of cessation efforts including those delivered by practicing physicians.

Another excellent example of this type of reinforcing synergy is the work of the past decade to address hyperlipidemia as a risk factor for heart disease. In this effort, physician screening and treatment of patients has been both promoted and complemented by national media campaigns, local health fairs, and ongoing research, to the point where many individuals now are familiar with cholesterol and want to know their own lipid values.

Drawing on both arenas to prioritize prevention strategies

The federal government has supported the development of several types of evidence-based prevention guidelines. Family physicians are familiar with the US Preventive Service Task Force Guide to Clinical Preventive Services,3 but may be less familiar with the more recently developed Guide to Community Preventive Services.4 For a comprehensive continuum of preventive care, both guides can be used in combination. Using both sets of recommendations can help physicians to prioritize prevention strategies for individuals, office patient populations, and communities.

The Community Guide is a federally sponsored initiative producing evidenced-based recommendations for health promotion and disease prevention from a population-based perspective sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Table 1). Like the Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, the independent task force that oversees the Community Guide develops evidence-based reviews of potential interventions and translates the findings into recommendations that can be used by policy makers, public health entities, and health systems.

TABLE 1

Topics covered in the Guide to Community Preventive Services

|

Actionable recommendations for practitioners

Though the Community Guide takes a population-based approach to prevention (eg, recommendations for policy strategies, mass media campaigns, and school health programs), a number of its recommendations focus on the health care system and are directly applicable to practicing family physicians. For instance:

- Vaccination: a section on provider-based interventions such as reminder systems, standing orders for adults, and provider feedback strategies

- Diabetes: a section on disease management strategies

- Tobacco: a section on improving the delivery of cessation services

- Cancer: a section on improving screening for specific diseases.

The topic reviews grade the strength of each intervention (strong evidence, sufficient evidence, or insufficient evidence), provide a 1-page summary of the recommendations, and have links to longer papers that review the specific evidence.

Complementary web support

The website also includes an excellent 2-page summary of types of activities family doctors can undertake, with links to specific directions for implementing prevention activities. Included are patient and provider reminder systems, disease and case management, and use of standing orders.4

The recommendations in both the Clinical and Community Guides that address common conditions provide especially strong “roadmaps” for focusing on and addressing health promotion and disease prevention. By using both guides, physicians can develop a range of effective, evidence-based approaches for practice. For example, Table 2 presents evidence-based recommendations concerning smoking. These recommendations fall across a range of preventive interventions.

Producing successful initiatives

Using the guides as a reference, the family physician could initiate screening of patients for smoking status in the practice and then implement one or more of the recommended strategies listed in Table 2. Possibilities include adding a provider reminder system, delivering brief counseling to quit smoking, prescribing cessation medications, and coupling these efforts with advocacy for development of a media campaign in the community. Family physicians who undertake community prevention efforts outside the office setting are likely to improve their success by partnering with other community health and social service professionals to implement agreed upon prevention interventions.5

As more topics are developed for the Community Guide, family physicians will likely find more reasons to refer to it as a companion to the Clinical Guide. Using the 2 together will enhance the benefit gained from using each alone in a way that is analogous to the added health benefits obtained when the traditional health care system works more closely with the public health system.

TABLE 2

Intervention strategies in the clinical and community guides

| Intervention strategy recommendation | Where it’s found | Where it’s to be used |

|---|---|---|

| Screening patients for tobacco use | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Provider gives brief advise to quit to patients who use tobacco | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Provider counseling to patients on tobacco cessation | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Self-help education materials for patients who use tobacco | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Pharmacologic treatment for tobacco and dependence | Clinical Guide | Office |

| Provider reminder systems | Community Guide | Office |

| Multicomponent clinical program (provider reminder + education) | Community Guide | Office |

| Patient-oriented interventions (telephone support; sliding fee scale) | Community Guide | Office |

| Policies, regulations, and laws (smoking ban and restrictions) | Community Guide | Community |

| Mass media campaigns | Community Guide | Community |

| Sources: Adapted from USPSTF, Guide to Clinical Preventive Services, 19963; | ||

| USPSTF, Guide to Community Preventive Services, 2000.4 | ||

Correspondence

Eric Henley, MD, MPH, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Turabian JL, Perez-Franco B. Cual es el sentido de la educacion para la salud y las actividades “communitaria” en atencion primaria? Aten Primaria. 1998;22:662-666.

2. Fletcher R, Fletcher S, Wagner E. Clinical Epidemiology: The Essentials. Philadelphia, Pa: Williams and Wilkins; 1996.

3. US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. Available at: www.ahcpr.gov/clinic/cpsix.htm

4. US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Community Preventive Services. Available at: www.thecommunityguide.org.

5. Peters K, Elster A. Population based medicine: Roadmaps to clinical practice. Chicago, Ill: American Medical Association, 2002.

1. Turabian JL, Perez-Franco B. Cual es el sentido de la educacion para la salud y las actividades “communitaria” en atencion primaria? Aten Primaria. 1998;22:662-666.

2. Fletcher R, Fletcher S, Wagner E. Clinical Epidemiology: The Essentials. Philadelphia, Pa: Williams and Wilkins; 1996.

3. US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Clinical Preventive Services. Available at: www.ahcpr.gov/clinic/cpsix.htm

4. US Preventive Services Task Force. Guide to Community Preventive Services. Available at: www.thecommunityguide.org.

5. Peters K, Elster A. Population based medicine: Roadmaps to clinical practice. Chicago, Ill: American Medical Association, 2002.

10 steps for avoiding health disparities in your practice

We hope the answer to the question above is no. However, the evidence regarding differences in the care of patients based on race, ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status suggests that if this patient is a woman or African American or from a lower socioeconomic class, resultant morbidity or mortality will be higher.

Differences are seen in the provision of cardiovascular care, cancer diagnosis and treament, and HIV care. African Americans, Latino Americans, Asian Americans, and Native Americans have higher morbidity and mortality than Caucasian chemical dependency, diabetes, heart disease, infant Americans for multiple problems including cancer, mortality, and unintentional and intentional injuries.1

This article explores possible explanations for health care disparities and offers 10 practical strategies for tackling this challenging issue.

Examples of health disparities

The United States has dramatically improved the health status of its citizens—increasing longevity, reducing infant mortality and teenage pregnancies, and increasing the number of children being immunized. Despite these improvements, though, there remain persistent and disproportionate burdens of disease and illness borne by subgroups of the population (Table 1). 2,3

The Institute of Medicine in its recent report, “Unequal Treatment,” approaches the issue from another perspective: they define these disparities as “racial or ethnic differences in the quality of healthcare that are not due to access-related factors or clinical needs, preferences and appropriateness of intervention.”4

TABLE 1

Examples of health disparities that could be changed

| Disparity in mortality |

| Infant mortality |

| Infant mortality is higher for infants of African American, Native Hawaiian, and Native American mothers (13.8, 10.0, and 9.3 deaths per 1000 live births, respectively) than for infants of other race groups. Infant mortality decreases as the mother’s level of education increases. |

| Disparity in morbidity |

| Cancer (males) |

| The incidence of cancer among black males exceeds that of white males for prostate cancer (60%), lung and bronchial cancer (58% ), and colon and rectum cancers (14%). |

| Disparity in health behaviors |

| Cigarette smoking |

| Smoking among persons aged 25 years and over ranges from 11% among college graduates to 32% for those without a high school diploma; 19% of adolescents in the most rural counties smoke compared to 11% in central counties. |

| Disparity in preventive health care |

| Mammography |

| Poor women are 27% less likely to have had a recent mammogram than are women with family incomes above the poverty level. |

| Disparity in access to care |

| Health insurance coverage |

| 13% of children under aged <18 years have no health insurance coverage; 28% of children with family incomes of 1 to 1.5 times the poverty level are without coverage, compared with 5% of those with family incomes at least twice the poverty level. |

| Source: Adapted from Health, United States, 2001. |

| Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics; 2001. |

Correcting health disparity begins with understanding its causes

A number of factors account for disparities in health and health care.

Population-influenced factors

Leading candidates are some population groups’ lower socioeconomic status (eg, income, occupation, education) and increased exposure to unhealthy environments. Individuals may also exhibit preferences for or against treatment (when appropriate treatment recommendations are offered) that mirror group preferences.

For example, African American patients’ distrust of the healthcare system may be based in part on their experience of discrimination as research subjects in the Tuskegee syphilis study and Los Angeles measles immunization study. Research has shown that while these issues are relevant, they do not fully account for observed disparities.

System factors

Problems with access to care are common: inadequate insurance, transportation difficulties, geographic barriers to needed services (rural/urban), and language barriers. Again, research has shown that access to care matters, but not necessarily more than other factors.

Individual factors

At the individual level, a clinical encounter may be adversely affected by physician-patient racial/ethnic discordance, patient health literacy, and physician cultural competence. Also, there is the high prevalence of risky behavior such as smoking.

Finally, provider-specific issues may be operative: bias (prejudice) against certain groups of patients, clinical uncertainty when dealing with patients, and stereotypes held by providers about the behavior or health of different groups of patients according to race, ethnicity, or culture.

Addressing disparities in practice

Clearly, improving the socioeconomic status and access to care for all people are among the most important ways to eliminate health disparities. Physicians can influence these areas through individual participation in political activities, in nonprofit organizations, and in their professional organizations.

Steps can also be taken in your own practice (Table 2).

TABLE 2

Ten practical measures for avoiding health disparity in your practice

| Use evidence-based clinical guidelines as much as possible. |

| Consider the health literacy level of your patients when planning care and treatment, when explaining medical recommendations, and when handing out written material. |

| Ensure that front desk staff are sensitive to patient backgrounds and cultures. |

| Provide culturally sensitive patient education materials (eg, brochures in Spanish). |

| Keep a “black book” with the names and numbers of community health resources. |

| Volunteer with a nonprofit community-based agency in your area. |

| Ask your local health department or managed care plans if they have a community health improvement plan. Get involved in creating or implementing the plan. |

| Create a special program for one or more of the populations you care for (eg, a school-based program to help reduce teenage pregnancy). |

| Develop a plan for translation services. |

| Browse through the Institute of Medicine report, “Unequal Treatment” (available at www.iom.edu/report.asp?id=4475). |

Use evidence-based guidelines

To minimize the effect of possible bias and stereotyping in caring for patients of different races, ethnicities, and cultures, an important foundation is to standardize care for all patients by using evidence-based practice guidelines when appropriate. Clinical guidelines such as those published by the US Preventive Services Task Force and those available on the Internet through the National Guideline Clearinghouse provide well-researched and substantiated recommendations (available at www.ngc.gov).

Using guidelines is consistent with national recommendations to incorporate more evidence-based practices in clinical care.

Make your office patient-friendly

Create an office environment that is sensitive to the needs of all patients. Addressing language issues, having front desk staff who are sensitive and unbiased, and providing culturally relevant patient education material (eg, posters, magazines) are important components of a supportive office environment.1

Advocate patient education

Strategies to improve patient health literacy and physician cultural competence may be of benefit. The literacy issue can be helped considerably by enabling patients to increase their understanding of health terminology, and there are national efforts to address patient health literacy. Physicians can also help by explaining options and care plans simply, carefully, and without medical jargon. The American Medical Association has a national campaign in support of health literacy (www.amaassn.org/ama/pub/category/8115.html).

Increase cross-cultural communication skills

The Institute of Medicine and academicians have increasingly recommended training healthcare professionals to be more culturally competent. Experts have agreed that the “essence of cultural competence is not the mastery of ‘facts’ about different ethnic groups, but rather a patient-centered approach that incorporates fundamental skills and attitudes that may be applicable across ethnic boundaries.”6

A recent national survey supported this idea by showing that racial differences in patient satisfaction disappeared after adjustment for the quality of physician behaviors (eg, showing respect for patients, spending adequate time with patients). The fact that these positive physician behaviors were reported more frequently by white than non-white patients points to the need for continued effort at improving physicians’ interpersonal skills.

Eliminating health disparities is one of the top 2 goals of Healthy People 2010, the document that guides the nation’s health promotion and disease prevention agenda. Healthy People 2010 (www.health.gov/healthypeople) is a compilation of important prevention objectives for the Nation identified by the US Public Health Service that helps to focus health care system and community efforts. The vision for Healthy People 2010 is “Healthy People in Healthy Communities,” a theme emphasizing that the health of the individual is closely linked with the health of the community.

The Leading Health Indicators are a subset of the Healthy People 2010 objectives and were chosen for emphasis because they account for more than 50% of the leading preventable causes of morbidity and premature morality in the US. 5 Data on these 10 objectives also point to disparities in health status and health outcomes among population groups in the US. Most states and many local communities have used the Healthy People 2010/Leading Health Indicators to develop and implement state and local “Healthy People” plans.

Physicians have an important role in efforts to meet these goals because many of them can only be met by utilizing multicomponent intervention strategies that include actions at the clinic, health care system and community level.

Corresponding author

Eric Henley, MD, MPH, Co-Editor, Practice Alert, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Tucker C, Herman K, Pedersen T, Higley B, Montrichard M, Ivery P. Cultural sensitivity in physician-patient relationships: perspectives of an ethnically diverse sample of low-income primary care patients. Med Care 2003;41:859-870.

2. Fiscella K, Franks P, Gold MR, Clancy CM. Inequality in quality: addressing socioeconomic, racial and ethnic disparities in health care. JAMA 2000;283:2579-2584.

3. Navarro V. Race or class versus race and class: mortality differentials in the United States. Lancet 1990;336:1238-1240.

4. Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. Available at: www.iom.edu/report.asp?id=4475. Accessed on February 13, 2004.

5. McGinnis JM, Foege W. Actual causes of death in the Unites States. JAMA 1993;270:2207-2212.

6. Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, Cooper LA. Patient-Physician relationships and racial disparities in the quality of health care. Am J Public Health 2003;93:1713-1719.

We hope the answer to the question above is no. However, the evidence regarding differences in the care of patients based on race, ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status suggests that if this patient is a woman or African American or from a lower socioeconomic class, resultant morbidity or mortality will be higher.

Differences are seen in the provision of cardiovascular care, cancer diagnosis and treament, and HIV care. African Americans, Latino Americans, Asian Americans, and Native Americans have higher morbidity and mortality than Caucasian chemical dependency, diabetes, heart disease, infant Americans for multiple problems including cancer, mortality, and unintentional and intentional injuries.1

This article explores possible explanations for health care disparities and offers 10 practical strategies for tackling this challenging issue.

Examples of health disparities

The United States has dramatically improved the health status of its citizens—increasing longevity, reducing infant mortality and teenage pregnancies, and increasing the number of children being immunized. Despite these improvements, though, there remain persistent and disproportionate burdens of disease and illness borne by subgroups of the population (Table 1). 2,3

The Institute of Medicine in its recent report, “Unequal Treatment,” approaches the issue from another perspective: they define these disparities as “racial or ethnic differences in the quality of healthcare that are not due to access-related factors or clinical needs, preferences and appropriateness of intervention.”4

TABLE 1

Examples of health disparities that could be changed

| Disparity in mortality |

| Infant mortality |

| Infant mortality is higher for infants of African American, Native Hawaiian, and Native American mothers (13.8, 10.0, and 9.3 deaths per 1000 live births, respectively) than for infants of other race groups. Infant mortality decreases as the mother’s level of education increases. |

| Disparity in morbidity |

| Cancer (males) |

| The incidence of cancer among black males exceeds that of white males for prostate cancer (60%), lung and bronchial cancer (58% ), and colon and rectum cancers (14%). |

| Disparity in health behaviors |

| Cigarette smoking |

| Smoking among persons aged 25 years and over ranges from 11% among college graduates to 32% for those without a high school diploma; 19% of adolescents in the most rural counties smoke compared to 11% in central counties. |

| Disparity in preventive health care |

| Mammography |

| Poor women are 27% less likely to have had a recent mammogram than are women with family incomes above the poverty level. |

| Disparity in access to care |

| Health insurance coverage |

| 13% of children under aged <18 years have no health insurance coverage; 28% of children with family incomes of 1 to 1.5 times the poverty level are without coverage, compared with 5% of those with family incomes at least twice the poverty level. |

| Source: Adapted from Health, United States, 2001. |

| Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics; 2001. |

Correcting health disparity begins with understanding its causes

A number of factors account for disparities in health and health care.

Population-influenced factors

Leading candidates are some population groups’ lower socioeconomic status (eg, income, occupation, education) and increased exposure to unhealthy environments. Individuals may also exhibit preferences for or against treatment (when appropriate treatment recommendations are offered) that mirror group preferences.

For example, African American patients’ distrust of the healthcare system may be based in part on their experience of discrimination as research subjects in the Tuskegee syphilis study and Los Angeles measles immunization study. Research has shown that while these issues are relevant, they do not fully account for observed disparities.

System factors

Problems with access to care are common: inadequate insurance, transportation difficulties, geographic barriers to needed services (rural/urban), and language barriers. Again, research has shown that access to care matters, but not necessarily more than other factors.

Individual factors

At the individual level, a clinical encounter may be adversely affected by physician-patient racial/ethnic discordance, patient health literacy, and physician cultural competence. Also, there is the high prevalence of risky behavior such as smoking.

Finally, provider-specific issues may be operative: bias (prejudice) against certain groups of patients, clinical uncertainty when dealing with patients, and stereotypes held by providers about the behavior or health of different groups of patients according to race, ethnicity, or culture.

Addressing disparities in practice

Clearly, improving the socioeconomic status and access to care for all people are among the most important ways to eliminate health disparities. Physicians can influence these areas through individual participation in political activities, in nonprofit organizations, and in their professional organizations.

Steps can also be taken in your own practice (Table 2).

TABLE 2

Ten practical measures for avoiding health disparity in your practice

| Use evidence-based clinical guidelines as much as possible. |

| Consider the health literacy level of your patients when planning care and treatment, when explaining medical recommendations, and when handing out written material. |

| Ensure that front desk staff are sensitive to patient backgrounds and cultures. |

| Provide culturally sensitive patient education materials (eg, brochures in Spanish). |

| Keep a “black book” with the names and numbers of community health resources. |

| Volunteer with a nonprofit community-based agency in your area. |

| Ask your local health department or managed care plans if they have a community health improvement plan. Get involved in creating or implementing the plan. |

| Create a special program for one or more of the populations you care for (eg, a school-based program to help reduce teenage pregnancy). |

| Develop a plan for translation services. |

| Browse through the Institute of Medicine report, “Unequal Treatment” (available at www.iom.edu/report.asp?id=4475). |

Use evidence-based guidelines

To minimize the effect of possible bias and stereotyping in caring for patients of different races, ethnicities, and cultures, an important foundation is to standardize care for all patients by using evidence-based practice guidelines when appropriate. Clinical guidelines such as those published by the US Preventive Services Task Force and those available on the Internet through the National Guideline Clearinghouse provide well-researched and substantiated recommendations (available at www.ngc.gov).

Using guidelines is consistent with national recommendations to incorporate more evidence-based practices in clinical care.

Make your office patient-friendly

Create an office environment that is sensitive to the needs of all patients. Addressing language issues, having front desk staff who are sensitive and unbiased, and providing culturally relevant patient education material (eg, posters, magazines) are important components of a supportive office environment.1

Advocate patient education

Strategies to improve patient health literacy and physician cultural competence may be of benefit. The literacy issue can be helped considerably by enabling patients to increase their understanding of health terminology, and there are national efforts to address patient health literacy. Physicians can also help by explaining options and care plans simply, carefully, and without medical jargon. The American Medical Association has a national campaign in support of health literacy (www.amaassn.org/ama/pub/category/8115.html).

Increase cross-cultural communication skills

The Institute of Medicine and academicians have increasingly recommended training healthcare professionals to be more culturally competent. Experts have agreed that the “essence of cultural competence is not the mastery of ‘facts’ about different ethnic groups, but rather a patient-centered approach that incorporates fundamental skills and attitudes that may be applicable across ethnic boundaries.”6

A recent national survey supported this idea by showing that racial differences in patient satisfaction disappeared after adjustment for the quality of physician behaviors (eg, showing respect for patients, spending adequate time with patients). The fact that these positive physician behaviors were reported more frequently by white than non-white patients points to the need for continued effort at improving physicians’ interpersonal skills.

Eliminating health disparities is one of the top 2 goals of Healthy People 2010, the document that guides the nation’s health promotion and disease prevention agenda. Healthy People 2010 (www.health.gov/healthypeople) is a compilation of important prevention objectives for the Nation identified by the US Public Health Service that helps to focus health care system and community efforts. The vision for Healthy People 2010 is “Healthy People in Healthy Communities,” a theme emphasizing that the health of the individual is closely linked with the health of the community.

The Leading Health Indicators are a subset of the Healthy People 2010 objectives and were chosen for emphasis because they account for more than 50% of the leading preventable causes of morbidity and premature morality in the US. 5 Data on these 10 objectives also point to disparities in health status and health outcomes among population groups in the US. Most states and many local communities have used the Healthy People 2010/Leading Health Indicators to develop and implement state and local “Healthy People” plans.

Physicians have an important role in efforts to meet these goals because many of them can only be met by utilizing multicomponent intervention strategies that include actions at the clinic, health care system and community level.

Corresponding author

Eric Henley, MD, MPH, Co-Editor, Practice Alert, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107. E-mail: [email protected].

We hope the answer to the question above is no. However, the evidence regarding differences in the care of patients based on race, ethnicity, gender, and socioeconomic status suggests that if this patient is a woman or African American or from a lower socioeconomic class, resultant morbidity or mortality will be higher.

Differences are seen in the provision of cardiovascular care, cancer diagnosis and treament, and HIV care. African Americans, Latino Americans, Asian Americans, and Native Americans have higher morbidity and mortality than Caucasian chemical dependency, diabetes, heart disease, infant Americans for multiple problems including cancer, mortality, and unintentional and intentional injuries.1

This article explores possible explanations for health care disparities and offers 10 practical strategies for tackling this challenging issue.

Examples of health disparities

The United States has dramatically improved the health status of its citizens—increasing longevity, reducing infant mortality and teenage pregnancies, and increasing the number of children being immunized. Despite these improvements, though, there remain persistent and disproportionate burdens of disease and illness borne by subgroups of the population (Table 1). 2,3

The Institute of Medicine in its recent report, “Unequal Treatment,” approaches the issue from another perspective: they define these disparities as “racial or ethnic differences in the quality of healthcare that are not due to access-related factors or clinical needs, preferences and appropriateness of intervention.”4

TABLE 1

Examples of health disparities that could be changed

| Disparity in mortality |

| Infant mortality |

| Infant mortality is higher for infants of African American, Native Hawaiian, and Native American mothers (13.8, 10.0, and 9.3 deaths per 1000 live births, respectively) than for infants of other race groups. Infant mortality decreases as the mother’s level of education increases. |

| Disparity in morbidity |

| Cancer (males) |

| The incidence of cancer among black males exceeds that of white males for prostate cancer (60%), lung and bronchial cancer (58% ), and colon and rectum cancers (14%). |

| Disparity in health behaviors |

| Cigarette smoking |

| Smoking among persons aged 25 years and over ranges from 11% among college graduates to 32% for those without a high school diploma; 19% of adolescents in the most rural counties smoke compared to 11% in central counties. |

| Disparity in preventive health care |

| Mammography |

| Poor women are 27% less likely to have had a recent mammogram than are women with family incomes above the poverty level. |

| Disparity in access to care |

| Health insurance coverage |

| 13% of children under aged <18 years have no health insurance coverage; 28% of children with family incomes of 1 to 1.5 times the poverty level are without coverage, compared with 5% of those with family incomes at least twice the poverty level. |

| Source: Adapted from Health, United States, 2001. |

| Hyattsville, Md: National Center for Health Statistics; 2001. |

Correcting health disparity begins with understanding its causes

A number of factors account for disparities in health and health care.

Population-influenced factors

Leading candidates are some population groups’ lower socioeconomic status (eg, income, occupation, education) and increased exposure to unhealthy environments. Individuals may also exhibit preferences for or against treatment (when appropriate treatment recommendations are offered) that mirror group preferences.

For example, African American patients’ distrust of the healthcare system may be based in part on their experience of discrimination as research subjects in the Tuskegee syphilis study and Los Angeles measles immunization study. Research has shown that while these issues are relevant, they do not fully account for observed disparities.

System factors

Problems with access to care are common: inadequate insurance, transportation difficulties, geographic barriers to needed services (rural/urban), and language barriers. Again, research has shown that access to care matters, but not necessarily more than other factors.

Individual factors

At the individual level, a clinical encounter may be adversely affected by physician-patient racial/ethnic discordance, patient health literacy, and physician cultural competence. Also, there is the high prevalence of risky behavior such as smoking.

Finally, provider-specific issues may be operative: bias (prejudice) against certain groups of patients, clinical uncertainty when dealing with patients, and stereotypes held by providers about the behavior or health of different groups of patients according to race, ethnicity, or culture.

Addressing disparities in practice

Clearly, improving the socioeconomic status and access to care for all people are among the most important ways to eliminate health disparities. Physicians can influence these areas through individual participation in political activities, in nonprofit organizations, and in their professional organizations.

Steps can also be taken in your own practice (Table 2).

TABLE 2

Ten practical measures for avoiding health disparity in your practice

| Use evidence-based clinical guidelines as much as possible. |

| Consider the health literacy level of your patients when planning care and treatment, when explaining medical recommendations, and when handing out written material. |

| Ensure that front desk staff are sensitive to patient backgrounds and cultures. |

| Provide culturally sensitive patient education materials (eg, brochures in Spanish). |

| Keep a “black book” with the names and numbers of community health resources. |

| Volunteer with a nonprofit community-based agency in your area. |

| Ask your local health department or managed care plans if they have a community health improvement plan. Get involved in creating or implementing the plan. |

| Create a special program for one or more of the populations you care for (eg, a school-based program to help reduce teenage pregnancy). |

| Develop a plan for translation services. |

| Browse through the Institute of Medicine report, “Unequal Treatment” (available at www.iom.edu/report.asp?id=4475). |

Use evidence-based guidelines

To minimize the effect of possible bias and stereotyping in caring for patients of different races, ethnicities, and cultures, an important foundation is to standardize care for all patients by using evidence-based practice guidelines when appropriate. Clinical guidelines such as those published by the US Preventive Services Task Force and those available on the Internet through the National Guideline Clearinghouse provide well-researched and substantiated recommendations (available at www.ngc.gov).

Using guidelines is consistent with national recommendations to incorporate more evidence-based practices in clinical care.

Make your office patient-friendly

Create an office environment that is sensitive to the needs of all patients. Addressing language issues, having front desk staff who are sensitive and unbiased, and providing culturally relevant patient education material (eg, posters, magazines) are important components of a supportive office environment.1

Advocate patient education

Strategies to improve patient health literacy and physician cultural competence may be of benefit. The literacy issue can be helped considerably by enabling patients to increase their understanding of health terminology, and there are national efforts to address patient health literacy. Physicians can also help by explaining options and care plans simply, carefully, and without medical jargon. The American Medical Association has a national campaign in support of health literacy (www.amaassn.org/ama/pub/category/8115.html).

Increase cross-cultural communication skills

The Institute of Medicine and academicians have increasingly recommended training healthcare professionals to be more culturally competent. Experts have agreed that the “essence of cultural competence is not the mastery of ‘facts’ about different ethnic groups, but rather a patient-centered approach that incorporates fundamental skills and attitudes that may be applicable across ethnic boundaries.”6

A recent national survey supported this idea by showing that racial differences in patient satisfaction disappeared after adjustment for the quality of physician behaviors (eg, showing respect for patients, spending adequate time with patients). The fact that these positive physician behaviors were reported more frequently by white than non-white patients points to the need for continued effort at improving physicians’ interpersonal skills.

Eliminating health disparities is one of the top 2 goals of Healthy People 2010, the document that guides the nation’s health promotion and disease prevention agenda. Healthy People 2010 (www.health.gov/healthypeople) is a compilation of important prevention objectives for the Nation identified by the US Public Health Service that helps to focus health care system and community efforts. The vision for Healthy People 2010 is “Healthy People in Healthy Communities,” a theme emphasizing that the health of the individual is closely linked with the health of the community.

The Leading Health Indicators are a subset of the Healthy People 2010 objectives and were chosen for emphasis because they account for more than 50% of the leading preventable causes of morbidity and premature morality in the US. 5 Data on these 10 objectives also point to disparities in health status and health outcomes among population groups in the US. Most states and many local communities have used the Healthy People 2010/Leading Health Indicators to develop and implement state and local “Healthy People” plans.

Physicians have an important role in efforts to meet these goals because many of them can only be met by utilizing multicomponent intervention strategies that include actions at the clinic, health care system and community level.

Corresponding author

Eric Henley, MD, MPH, Co-Editor, Practice Alert, 1601 Parkview Avenue, Rockford, IL 61107. E-mail: [email protected].

1. Tucker C, Herman K, Pedersen T, Higley B, Montrichard M, Ivery P. Cultural sensitivity in physician-patient relationships: perspectives of an ethnically diverse sample of low-income primary care patients. Med Care 2003;41:859-870.

2. Fiscella K, Franks P, Gold MR, Clancy CM. Inequality in quality: addressing socioeconomic, racial and ethnic disparities in health care. JAMA 2000;283:2579-2584.

3. Navarro V. Race or class versus race and class: mortality differentials in the United States. Lancet 1990;336:1238-1240.

4. Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. Available at: www.iom.edu/report.asp?id=4475. Accessed on February 13, 2004.

5. McGinnis JM, Foege W. Actual causes of death in the Unites States. JAMA 1993;270:2207-2212.

6. Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, Cooper LA. Patient-Physician relationships and racial disparities in the quality of health care. Am J Public Health 2003;93:1713-1719.

1. Tucker C, Herman K, Pedersen T, Higley B, Montrichard M, Ivery P. Cultural sensitivity in physician-patient relationships: perspectives of an ethnically diverse sample of low-income primary care patients. Med Care 2003;41:859-870.

2. Fiscella K, Franks P, Gold MR, Clancy CM. Inequality in quality: addressing socioeconomic, racial and ethnic disparities in health care. JAMA 2000;283:2579-2584.

3. Navarro V. Race or class versus race and class: mortality differentials in the United States. Lancet 1990;336:1238-1240.

4. Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2002. Available at: www.iom.edu/report.asp?id=4475. Accessed on February 13, 2004.

5. McGinnis JM, Foege W. Actual causes of death in the Unites States. JAMA 1993;270:2207-2212.

6. Saha S, Arbelaez JJ, Cooper LA. Patient-Physician relationships and racial disparities in the quality of health care. Am J Public Health 2003;93:1713-1719.