User login

Adenomyosis causing severe dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and heavy menstrual bleeding has been thought to affect primarily multiparous women in their mid- to late 40s. Often women who experience pain and heavy bleeding will tolerate their symptoms until they are done with childbearing, at which point they often go on to have a hysterectomy to relieve them of these symptoms. Tissue histology obtained at the time of hysterectomy confirms the diagnosis of adenomyosis.

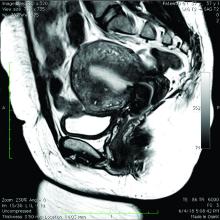

Because the diagnosis is made at the time of hysterectomy, the published incidence and prevalence of adenomyosis is more a reflection of a risk for hysterectomy and not for the disease itself. MRI has been used to evaluate the junctional zone in patients with symptoms of endometriosis. This screen tool is an expensive one, however, and has not been used extensively to evaluate women with symptoms of adenomyosis who are not candidates for a hysterectomy.

Ultrasound studies

Over the past 5-7 years, numerous studies have been performed that demonstrate ultrasound changes consistent with adenomyosis within the uterus. These changes include asymmetry and heterogeneity of the anterior and posterior myometrium, cystic lesions in the myometrium, ultrasound striations, and streaking and irregular junctional zone thickening seen on 3-D scans.

Our newfound ability to demonstrate changes consistent with adenomyosis by ultrasound – a tool that is much less expensive than MRI and more available to patients – means that we can and should consider adenomyosis in patients suffering from dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, back pain, dyspareunia, and infertility – regardless of the patient’s age.

In the last 5 years, adenomyosis has been increasingly recognized as a disorder affecting women of all reproductive ages, including teenagers whose dysmenorrhea disrupts their education and young women undergoing infertility evaluations. In one study, 12% of adolescent girls and young women aged 14–20 years lost days of school or work each month because of dysmenorrhea.1 This disruption is not “normal.”

Several meta-analyses have also demonstrated that ultrasound and MRI changes consistent with adenomyosis can affect embryo implantation rates in women undergoing in vitro fertilization. The implantation rates can be as low as one half the expected rate without adenomyosis. Additionally, adenomyosis has been shown to increase the risk of miscarriage and preterm delivery.2,3

The clinicians who order and carefully look at the ultrasound themselves, rather than rely on the radiologist to make the diagnosis, will be able to see the changes consistent with adenomyosis. Over time – I anticipate the next several years – a standardized radiologic definition for adenomyosis will evolve, and radiologists will become more familiar with these changes. In the meantime, our patients should not have missed diagnoses.

Considerations for surgery

For the majority of younger patients who are not trying to conceive but want to maintain their fertility, medical treatment with oral contraceptives, progestins, or the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (Mirena) will relieve symptoms. The Mirena IUD has been found in studies of 6-36 months’ treatment duration to decrease the size of the uterus by 25%4 and improve dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia with a low profile of adverse effects in most women.

The Mirena IUD should be considered as a first-line therapy for all women with heavy menstrual bleeding and dyspareunia who want to preserve their fertility.

Patients who do not respond to or cannot tolerate medical therapy, and do not want to preserve their fertility, may consider hysterectomy, long regarded as the preferred method of treatment. Endometrial ablation can also be considered in those who no longer desire to preserve fertility and are experiencing heavy menstrual bleeding. Those with extensive adenomyosis, however, often experience poor results with endometrial ablation and may ultimately require hysterectomy. Endometrial ablation has a history of a high failure rate in women younger than 45 years old.

Patients with adenomyosis who wish to preserve their fertility and cannot tolerate or are unresponsive to hormonal therapy, or those with infertility thought to be caused by adenomyosis, should consider these three management options:

- Do nothing. The embryo implantation rate is not zero with adenomyosis, and we have no data on the number of patients who conceive with adenomyotic changes detected by MRI or ultrasound.

- Pretreat with a GnRH agonist for 2-3 months prior to a frozen embryo transfer (FET). Suppressing the disease prior to an FET seems to increase the implantation rate to what is expected for that patient given her age and other fertility factors.3 While this approach is often successful, an estimated 15%-20% of patients are unable to tolerate GnRH agonist treatment because of its side effects.

- Seek surgical resection of adenomyosis. Unlike uterine fibroids, adenomyosis has no pseudocapsule. When resecting the disease via laparotomy, laparoscopy, or hysteroscopy, the process is more of a debulking procedure. Surgical resection should be reserved for those who cannot tolerate hormonal suppression or have failed the other two options.

Surgical approaches

Surgical excision can be challenging because adenomyosis burrows its way through the muscle, is often diffuse, and cannot necessarily be resected with clean margins as can a fibroid. Yet, as demonstrated in a systematic review of 27 observational studies of conservative surgery for adenomyosis – 10 prospective and 17 retrospective studies with a total of almost 1,400 patients and all with adenomyosis confirmed histopathologically – surgery can improve pain, menorrhagia, and adenomyosis-related infertility in a significant number of cases.5

Disease may be resected through laparotomy, laparoscopy, or as we are currently doing with focal disease that is close to the endometrium, hysteroscopy. The type of surgery will depend on the location and characteristics of the disease, and on the surgeon’s skills. The principles are the same with all three approaches: to remove as much diseased tissue – and preserve as much healthy myometrial tissue – as possible and to reconstruct the uterine wall so that it maintains its integrity and can sustain a pregnancy.

The open approach known as the Osada procedure, after Hisao Osada, MD, PhD, in Tokyo, is well described in the literature, with a relatively large number of cases reported in prospective studies. Dr. Osada performs a radical adenomyosis excision with a triple flap method of uterine wall reconstruction. The uterus is bisected in the mid-sagittal plane all the way down through the adenomyosis until the uterine cavity is reached. Excision of the adenomyotic tissue is guided by palpation with the index finger, and a myometrial thickness of 1 cm from the serosa and the endometrium is preserved.

The endometrium is closed, and the myometrial defect is closed with a triple flap method that avoids overlapping suture lines. On one side of the uterus, the myometrium and serosa are sutured in the antero-posterior plane. The seromuscular layer of the opposite side of the uterine wall is then brought over the first seromuscular suture line.6

Others, such as Grigoris H. Grimbizis, MD, PhD, in Greece, have used a laparoscopic approach and closed the myometrium in layers similar to those of a myomectomy.7 There are no comparative trials that demonstrate one technique is superior to the other.

While there are no textbook techniques published for resecting adenomyotic tissue laparoscopically or hysteroscopically from the normal myometrium, there are some general principals the surgeon should keep in mind. Adenomyosis is defined as the presence of endometrial glands and stroma within myometrium, but biopsy studies have demonstrated that there are relatively few glands and stroma within the diseased tissue. Mostly, the adenomyotic tissue we encounter comprises smooth muscle hyperplasia and fibrosis.

Since there is no pseudocapsule surrounding adenomyotic tissue, the visual cue for the cytoreductive procedure is the presence of normal-appearing myometrium. The normal myometrium can be delineated by palpation with laparoscopic instruments or hysteroscopic loops as it clearly feels less fibrotic and firm than the adenomyotic tissue. For this reason, the adenomyotic tissue is removed in a piecemeal fashion until normal tissue is encountered. (This same philosophy can be applied to removing fibrotic, glandular, or cystic tissue hysteroscopically.)

If the disease involves the inner myometrium, it should resected as this may be very important to restoring normal uterine contractions needed for embryo implantation and development, even if it means entering the cavity laparoscopically.

Hysteroscopically, there is no ability to suture a myometrial defect. This limitation is concerning because the adenomyosis is thought to invade the myometrium and not displace it as seen with monoclonal uterine fibroids. There are no case reports of uterine rupture after hysteroscopic resection of adenomyosis, but the number of cases reported with this type of resection in general is very small.

Laparoscopically, the myometrial defect should be repaired similarly to a myomectomy defect. Chromic or polydioxanone (PDS) suture is appropriate. We have used 2-0 PDS V-loc and a 2-3 layer closure in our laparoscopic cases.

Diffuse adenomyosis can involve the entire anterior or posterior wall of the uterus or both. The surgeon should not attempt to remove all of the disease in this situation and must leave enough tissue, even diseased, to allow for structural integrity during pregnancy. Uterine rupture has not been reported in all published case series and studies, but overall, it is a concern with surgical excision of adenomyosis. An analysis of over 2,000 cases of adenomyomectomies reported worldwide since 1990 shows a uterine rupture rate in the 6% rate, with a pregnancy rate ranging from 7%-72%.8

When the disease is focal and close to the endometrium, as opposed to diffuse and affecting the entire back wall of the uterus, hysteroscopic excision may be an appropriate, less invasive approach.

One of the patients for whom we’ve taken this approach was a 37-year-old patient who presented with a history of six miscarriages, a negative work-up for recurrent pregnancy loss, an enlarged uterus, 8 years of heavy menstrual bleeding, and only mild dysmenorrhea. She had undergone in vitro fertilization with failed embryo transfers but normal genetic screens of the embryos. She was referred with a suspicion of fibroids. An MRI and ultrasound showed heterogeneous myometrium adjacent to the endometrium. This tissue was resected using a bipolar loop electrode until normal myometrium was encountered.

Hysteroscopic resections are currently described in the literature through case reports rather than larger prospective or retrospective studies, and much more research is needed to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of this approach.

At this point in time, while surgery to excise adenomyosis is a last resort and best methods are deliberated, it is still important to appreciate that surgery is an option. Continued infertility is not the only choice, nor is hysterectomy.

References

1. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2014;27:258-65.

2. Minerva Ginecol. 2018 Jun;70(3):295-302.

3. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(3):483-490.e3.

4. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(4):373.e1-7.

5. J. Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018 Feb;25:265-76.

6. Reproductive BioMed Online. 2011 Jan;22(1):94-9.

7. Fertil Steril. 2014 Feb;101(2):472-87.

8. Fertil Steril. 2018 Mar;109(3):406-17.

Adenomyosis causing severe dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and heavy menstrual bleeding has been thought to affect primarily multiparous women in their mid- to late 40s. Often women who experience pain and heavy bleeding will tolerate their symptoms until they are done with childbearing, at which point they often go on to have a hysterectomy to relieve them of these symptoms. Tissue histology obtained at the time of hysterectomy confirms the diagnosis of adenomyosis.

Because the diagnosis is made at the time of hysterectomy, the published incidence and prevalence of adenomyosis is more a reflection of a risk for hysterectomy and not for the disease itself. MRI has been used to evaluate the junctional zone in patients with symptoms of endometriosis. This screen tool is an expensive one, however, and has not been used extensively to evaluate women with symptoms of adenomyosis who are not candidates for a hysterectomy.

Ultrasound studies

Over the past 5-7 years, numerous studies have been performed that demonstrate ultrasound changes consistent with adenomyosis within the uterus. These changes include asymmetry and heterogeneity of the anterior and posterior myometrium, cystic lesions in the myometrium, ultrasound striations, and streaking and irregular junctional zone thickening seen on 3-D scans.

Our newfound ability to demonstrate changes consistent with adenomyosis by ultrasound – a tool that is much less expensive than MRI and more available to patients – means that we can and should consider adenomyosis in patients suffering from dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, back pain, dyspareunia, and infertility – regardless of the patient’s age.

In the last 5 years, adenomyosis has been increasingly recognized as a disorder affecting women of all reproductive ages, including teenagers whose dysmenorrhea disrupts their education and young women undergoing infertility evaluations. In one study, 12% of adolescent girls and young women aged 14–20 years lost days of school or work each month because of dysmenorrhea.1 This disruption is not “normal.”

Several meta-analyses have also demonstrated that ultrasound and MRI changes consistent with adenomyosis can affect embryo implantation rates in women undergoing in vitro fertilization. The implantation rates can be as low as one half the expected rate without adenomyosis. Additionally, adenomyosis has been shown to increase the risk of miscarriage and preterm delivery.2,3

The clinicians who order and carefully look at the ultrasound themselves, rather than rely on the radiologist to make the diagnosis, will be able to see the changes consistent with adenomyosis. Over time – I anticipate the next several years – a standardized radiologic definition for adenomyosis will evolve, and radiologists will become more familiar with these changes. In the meantime, our patients should not have missed diagnoses.

Considerations for surgery

For the majority of younger patients who are not trying to conceive but want to maintain their fertility, medical treatment with oral contraceptives, progestins, or the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (Mirena) will relieve symptoms. The Mirena IUD has been found in studies of 6-36 months’ treatment duration to decrease the size of the uterus by 25%4 and improve dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia with a low profile of adverse effects in most women.

The Mirena IUD should be considered as a first-line therapy for all women with heavy menstrual bleeding and dyspareunia who want to preserve their fertility.

Patients who do not respond to or cannot tolerate medical therapy, and do not want to preserve their fertility, may consider hysterectomy, long regarded as the preferred method of treatment. Endometrial ablation can also be considered in those who no longer desire to preserve fertility and are experiencing heavy menstrual bleeding. Those with extensive adenomyosis, however, often experience poor results with endometrial ablation and may ultimately require hysterectomy. Endometrial ablation has a history of a high failure rate in women younger than 45 years old.

Patients with adenomyosis who wish to preserve their fertility and cannot tolerate or are unresponsive to hormonal therapy, or those with infertility thought to be caused by adenomyosis, should consider these three management options:

- Do nothing. The embryo implantation rate is not zero with adenomyosis, and we have no data on the number of patients who conceive with adenomyotic changes detected by MRI or ultrasound.

- Pretreat with a GnRH agonist for 2-3 months prior to a frozen embryo transfer (FET). Suppressing the disease prior to an FET seems to increase the implantation rate to what is expected for that patient given her age and other fertility factors.3 While this approach is often successful, an estimated 15%-20% of patients are unable to tolerate GnRH agonist treatment because of its side effects.

- Seek surgical resection of adenomyosis. Unlike uterine fibroids, adenomyosis has no pseudocapsule. When resecting the disease via laparotomy, laparoscopy, or hysteroscopy, the process is more of a debulking procedure. Surgical resection should be reserved for those who cannot tolerate hormonal suppression or have failed the other two options.

Surgical approaches

Surgical excision can be challenging because adenomyosis burrows its way through the muscle, is often diffuse, and cannot necessarily be resected with clean margins as can a fibroid. Yet, as demonstrated in a systematic review of 27 observational studies of conservative surgery for adenomyosis – 10 prospective and 17 retrospective studies with a total of almost 1,400 patients and all with adenomyosis confirmed histopathologically – surgery can improve pain, menorrhagia, and adenomyosis-related infertility in a significant number of cases.5

Disease may be resected through laparotomy, laparoscopy, or as we are currently doing with focal disease that is close to the endometrium, hysteroscopy. The type of surgery will depend on the location and characteristics of the disease, and on the surgeon’s skills. The principles are the same with all three approaches: to remove as much diseased tissue – and preserve as much healthy myometrial tissue – as possible and to reconstruct the uterine wall so that it maintains its integrity and can sustain a pregnancy.

The open approach known as the Osada procedure, after Hisao Osada, MD, PhD, in Tokyo, is well described in the literature, with a relatively large number of cases reported in prospective studies. Dr. Osada performs a radical adenomyosis excision with a triple flap method of uterine wall reconstruction. The uterus is bisected in the mid-sagittal plane all the way down through the adenomyosis until the uterine cavity is reached. Excision of the adenomyotic tissue is guided by palpation with the index finger, and a myometrial thickness of 1 cm from the serosa and the endometrium is preserved.

The endometrium is closed, and the myometrial defect is closed with a triple flap method that avoids overlapping suture lines. On one side of the uterus, the myometrium and serosa are sutured in the antero-posterior plane. The seromuscular layer of the opposite side of the uterine wall is then brought over the first seromuscular suture line.6

Others, such as Grigoris H. Grimbizis, MD, PhD, in Greece, have used a laparoscopic approach and closed the myometrium in layers similar to those of a myomectomy.7 There are no comparative trials that demonstrate one technique is superior to the other.

While there are no textbook techniques published for resecting adenomyotic tissue laparoscopically or hysteroscopically from the normal myometrium, there are some general principals the surgeon should keep in mind. Adenomyosis is defined as the presence of endometrial glands and stroma within myometrium, but biopsy studies have demonstrated that there are relatively few glands and stroma within the diseased tissue. Mostly, the adenomyotic tissue we encounter comprises smooth muscle hyperplasia and fibrosis.

Since there is no pseudocapsule surrounding adenomyotic tissue, the visual cue for the cytoreductive procedure is the presence of normal-appearing myometrium. The normal myometrium can be delineated by palpation with laparoscopic instruments or hysteroscopic loops as it clearly feels less fibrotic and firm than the adenomyotic tissue. For this reason, the adenomyotic tissue is removed in a piecemeal fashion until normal tissue is encountered. (This same philosophy can be applied to removing fibrotic, glandular, or cystic tissue hysteroscopically.)

If the disease involves the inner myometrium, it should resected as this may be very important to restoring normal uterine contractions needed for embryo implantation and development, even if it means entering the cavity laparoscopically.

Hysteroscopically, there is no ability to suture a myometrial defect. This limitation is concerning because the adenomyosis is thought to invade the myometrium and not displace it as seen with monoclonal uterine fibroids. There are no case reports of uterine rupture after hysteroscopic resection of adenomyosis, but the number of cases reported with this type of resection in general is very small.

Laparoscopically, the myometrial defect should be repaired similarly to a myomectomy defect. Chromic or polydioxanone (PDS) suture is appropriate. We have used 2-0 PDS V-loc and a 2-3 layer closure in our laparoscopic cases.

Diffuse adenomyosis can involve the entire anterior or posterior wall of the uterus or both. The surgeon should not attempt to remove all of the disease in this situation and must leave enough tissue, even diseased, to allow for structural integrity during pregnancy. Uterine rupture has not been reported in all published case series and studies, but overall, it is a concern with surgical excision of adenomyosis. An analysis of over 2,000 cases of adenomyomectomies reported worldwide since 1990 shows a uterine rupture rate in the 6% rate, with a pregnancy rate ranging from 7%-72%.8

When the disease is focal and close to the endometrium, as opposed to diffuse and affecting the entire back wall of the uterus, hysteroscopic excision may be an appropriate, less invasive approach.

One of the patients for whom we’ve taken this approach was a 37-year-old patient who presented with a history of six miscarriages, a negative work-up for recurrent pregnancy loss, an enlarged uterus, 8 years of heavy menstrual bleeding, and only mild dysmenorrhea. She had undergone in vitro fertilization with failed embryo transfers but normal genetic screens of the embryos. She was referred with a suspicion of fibroids. An MRI and ultrasound showed heterogeneous myometrium adjacent to the endometrium. This tissue was resected using a bipolar loop electrode until normal myometrium was encountered.

Hysteroscopic resections are currently described in the literature through case reports rather than larger prospective or retrospective studies, and much more research is needed to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of this approach.

At this point in time, while surgery to excise adenomyosis is a last resort and best methods are deliberated, it is still important to appreciate that surgery is an option. Continued infertility is not the only choice, nor is hysterectomy.

References

1. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2014;27:258-65.

2. Minerva Ginecol. 2018 Jun;70(3):295-302.

3. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(3):483-490.e3.

4. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(4):373.e1-7.

5. J. Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018 Feb;25:265-76.

6. Reproductive BioMed Online. 2011 Jan;22(1):94-9.

7. Fertil Steril. 2014 Feb;101(2):472-87.

8. Fertil Steril. 2018 Mar;109(3):406-17.

Adenomyosis causing severe dysmenorrhea, dyspareunia, and heavy menstrual bleeding has been thought to affect primarily multiparous women in their mid- to late 40s. Often women who experience pain and heavy bleeding will tolerate their symptoms until they are done with childbearing, at which point they often go on to have a hysterectomy to relieve them of these symptoms. Tissue histology obtained at the time of hysterectomy confirms the diagnosis of adenomyosis.

Because the diagnosis is made at the time of hysterectomy, the published incidence and prevalence of adenomyosis is more a reflection of a risk for hysterectomy and not for the disease itself. MRI has been used to evaluate the junctional zone in patients with symptoms of endometriosis. This screen tool is an expensive one, however, and has not been used extensively to evaluate women with symptoms of adenomyosis who are not candidates for a hysterectomy.

Ultrasound studies

Over the past 5-7 years, numerous studies have been performed that demonstrate ultrasound changes consistent with adenomyosis within the uterus. These changes include asymmetry and heterogeneity of the anterior and posterior myometrium, cystic lesions in the myometrium, ultrasound striations, and streaking and irregular junctional zone thickening seen on 3-D scans.

Our newfound ability to demonstrate changes consistent with adenomyosis by ultrasound – a tool that is much less expensive than MRI and more available to patients – means that we can and should consider adenomyosis in patients suffering from dysmenorrhea, heavy menstrual bleeding, back pain, dyspareunia, and infertility – regardless of the patient’s age.

In the last 5 years, adenomyosis has been increasingly recognized as a disorder affecting women of all reproductive ages, including teenagers whose dysmenorrhea disrupts their education and young women undergoing infertility evaluations. In one study, 12% of adolescent girls and young women aged 14–20 years lost days of school or work each month because of dysmenorrhea.1 This disruption is not “normal.”

Several meta-analyses have also demonstrated that ultrasound and MRI changes consistent with adenomyosis can affect embryo implantation rates in women undergoing in vitro fertilization. The implantation rates can be as low as one half the expected rate without adenomyosis. Additionally, adenomyosis has been shown to increase the risk of miscarriage and preterm delivery.2,3

The clinicians who order and carefully look at the ultrasound themselves, rather than rely on the radiologist to make the diagnosis, will be able to see the changes consistent with adenomyosis. Over time – I anticipate the next several years – a standardized radiologic definition for adenomyosis will evolve, and radiologists will become more familiar with these changes. In the meantime, our patients should not have missed diagnoses.

Considerations for surgery

For the majority of younger patients who are not trying to conceive but want to maintain their fertility, medical treatment with oral contraceptives, progestins, or the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (Mirena) will relieve symptoms. The Mirena IUD has been found in studies of 6-36 months’ treatment duration to decrease the size of the uterus by 25%4 and improve dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia with a low profile of adverse effects in most women.

The Mirena IUD should be considered as a first-line therapy for all women with heavy menstrual bleeding and dyspareunia who want to preserve their fertility.

Patients who do not respond to or cannot tolerate medical therapy, and do not want to preserve their fertility, may consider hysterectomy, long regarded as the preferred method of treatment. Endometrial ablation can also be considered in those who no longer desire to preserve fertility and are experiencing heavy menstrual bleeding. Those with extensive adenomyosis, however, often experience poor results with endometrial ablation and may ultimately require hysterectomy. Endometrial ablation has a history of a high failure rate in women younger than 45 years old.

Patients with adenomyosis who wish to preserve their fertility and cannot tolerate or are unresponsive to hormonal therapy, or those with infertility thought to be caused by adenomyosis, should consider these three management options:

- Do nothing. The embryo implantation rate is not zero with adenomyosis, and we have no data on the number of patients who conceive with adenomyotic changes detected by MRI or ultrasound.

- Pretreat with a GnRH agonist for 2-3 months prior to a frozen embryo transfer (FET). Suppressing the disease prior to an FET seems to increase the implantation rate to what is expected for that patient given her age and other fertility factors.3 While this approach is often successful, an estimated 15%-20% of patients are unable to tolerate GnRH agonist treatment because of its side effects.

- Seek surgical resection of adenomyosis. Unlike uterine fibroids, adenomyosis has no pseudocapsule. When resecting the disease via laparotomy, laparoscopy, or hysteroscopy, the process is more of a debulking procedure. Surgical resection should be reserved for those who cannot tolerate hormonal suppression or have failed the other two options.

Surgical approaches

Surgical excision can be challenging because adenomyosis burrows its way through the muscle, is often diffuse, and cannot necessarily be resected with clean margins as can a fibroid. Yet, as demonstrated in a systematic review of 27 observational studies of conservative surgery for adenomyosis – 10 prospective and 17 retrospective studies with a total of almost 1,400 patients and all with adenomyosis confirmed histopathologically – surgery can improve pain, menorrhagia, and adenomyosis-related infertility in a significant number of cases.5

Disease may be resected through laparotomy, laparoscopy, or as we are currently doing with focal disease that is close to the endometrium, hysteroscopy. The type of surgery will depend on the location and characteristics of the disease, and on the surgeon’s skills. The principles are the same with all three approaches: to remove as much diseased tissue – and preserve as much healthy myometrial tissue – as possible and to reconstruct the uterine wall so that it maintains its integrity and can sustain a pregnancy.

The open approach known as the Osada procedure, after Hisao Osada, MD, PhD, in Tokyo, is well described in the literature, with a relatively large number of cases reported in prospective studies. Dr. Osada performs a radical adenomyosis excision with a triple flap method of uterine wall reconstruction. The uterus is bisected in the mid-sagittal plane all the way down through the adenomyosis until the uterine cavity is reached. Excision of the adenomyotic tissue is guided by palpation with the index finger, and a myometrial thickness of 1 cm from the serosa and the endometrium is preserved.

The endometrium is closed, and the myometrial defect is closed with a triple flap method that avoids overlapping suture lines. On one side of the uterus, the myometrium and serosa are sutured in the antero-posterior plane. The seromuscular layer of the opposite side of the uterine wall is then brought over the first seromuscular suture line.6

Others, such as Grigoris H. Grimbizis, MD, PhD, in Greece, have used a laparoscopic approach and closed the myometrium in layers similar to those of a myomectomy.7 There are no comparative trials that demonstrate one technique is superior to the other.

While there are no textbook techniques published for resecting adenomyotic tissue laparoscopically or hysteroscopically from the normal myometrium, there are some general principals the surgeon should keep in mind. Adenomyosis is defined as the presence of endometrial glands and stroma within myometrium, but biopsy studies have demonstrated that there are relatively few glands and stroma within the diseased tissue. Mostly, the adenomyotic tissue we encounter comprises smooth muscle hyperplasia and fibrosis.

Since there is no pseudocapsule surrounding adenomyotic tissue, the visual cue for the cytoreductive procedure is the presence of normal-appearing myometrium. The normal myometrium can be delineated by palpation with laparoscopic instruments or hysteroscopic loops as it clearly feels less fibrotic and firm than the adenomyotic tissue. For this reason, the adenomyotic tissue is removed in a piecemeal fashion until normal tissue is encountered. (This same philosophy can be applied to removing fibrotic, glandular, or cystic tissue hysteroscopically.)

If the disease involves the inner myometrium, it should resected as this may be very important to restoring normal uterine contractions needed for embryo implantation and development, even if it means entering the cavity laparoscopically.

Hysteroscopically, there is no ability to suture a myometrial defect. This limitation is concerning because the adenomyosis is thought to invade the myometrium and not displace it as seen with monoclonal uterine fibroids. There are no case reports of uterine rupture after hysteroscopic resection of adenomyosis, but the number of cases reported with this type of resection in general is very small.

Laparoscopically, the myometrial defect should be repaired similarly to a myomectomy defect. Chromic or polydioxanone (PDS) suture is appropriate. We have used 2-0 PDS V-loc and a 2-3 layer closure in our laparoscopic cases.

Diffuse adenomyosis can involve the entire anterior or posterior wall of the uterus or both. The surgeon should not attempt to remove all of the disease in this situation and must leave enough tissue, even diseased, to allow for structural integrity during pregnancy. Uterine rupture has not been reported in all published case series and studies, but overall, it is a concern with surgical excision of adenomyosis. An analysis of over 2,000 cases of adenomyomectomies reported worldwide since 1990 shows a uterine rupture rate in the 6% rate, with a pregnancy rate ranging from 7%-72%.8

When the disease is focal and close to the endometrium, as opposed to diffuse and affecting the entire back wall of the uterus, hysteroscopic excision may be an appropriate, less invasive approach.

One of the patients for whom we’ve taken this approach was a 37-year-old patient who presented with a history of six miscarriages, a negative work-up for recurrent pregnancy loss, an enlarged uterus, 8 years of heavy menstrual bleeding, and only mild dysmenorrhea. She had undergone in vitro fertilization with failed embryo transfers but normal genetic screens of the embryos. She was referred with a suspicion of fibroids. An MRI and ultrasound showed heterogeneous myometrium adjacent to the endometrium. This tissue was resected using a bipolar loop electrode until normal myometrium was encountered.

Hysteroscopic resections are currently described in the literature through case reports rather than larger prospective or retrospective studies, and much more research is needed to demonstrate the efficacy and safety of this approach.

At this point in time, while surgery to excise adenomyosis is a last resort and best methods are deliberated, it is still important to appreciate that surgery is an option. Continued infertility is not the only choice, nor is hysterectomy.

References

1. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol 2014;27:258-65.

2. Minerva Ginecol. 2018 Jun;70(3):295-302.

3. Fertil Steril. 2017;108(3):483-490.e3.

4. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2008;198(4):373.e1-7.

5. J. Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2018 Feb;25:265-76.

6. Reproductive BioMed Online. 2011 Jan;22(1):94-9.

7. Fertil Steril. 2014 Feb;101(2):472-87.

8. Fertil Steril. 2018 Mar;109(3):406-17.