User login

CASE A 40-year-old man came to our office slightly agitated. He had an acute illness that was minor in nature. However, he was not interested in answering my questions or undergoing a physical exam. The more I tried to proceed with the visit, the more agitated he became—pacing the room, muttering, avoiding eye contact. I was uncomfortable and knew that the situation could quickly escalate if it was not brought under control.

What steps would you take if this were your patient?

The scene described above occurred several years ago, but more recently, one of the institutions in my (TIM) area was affected by a shooter in the workplace. The apprehension felt by all of us who were on the periphery paled in comparison to what was experienced by those at the scene. The outcome was horrific. Communicating with those directly involved during, and immediately after, the event was heart-wrenching. The trauma that they continue to relive is unimaginable, and some are not yet able to return to work.

Situations involving agitated patients are not uncommon in health care settings, although ones that escalate to the level of a shooting are. And no matter where on the spectrum an incident involving an agitated patient falls, it can leave those involved with various levels of physical, emotional, and psychological harm. It can also leave everyone asking themselves: “How can I better prepare for such occurrences?”

This article offers some answers by providing tips and guidelines for handling agitated and/or violent patients in various settings.

[polldaddy:9948472]

Defining the problem, assessing its severity

Between 2011 and 2013, workplace assaults ranged from 23,540 and 25,630 annually, with 70% to 74% occurring in health care and social service settings.1,2

Agitation is defined as a state that may include inattention, disinhibition, emotional lability, impulsivity, motor restlessness, and aggression.3,4 Violence in a clinical setting may be seen as an extreme expression of agitation sufficient enough to cause harm to an individual or damage to an object.5,6

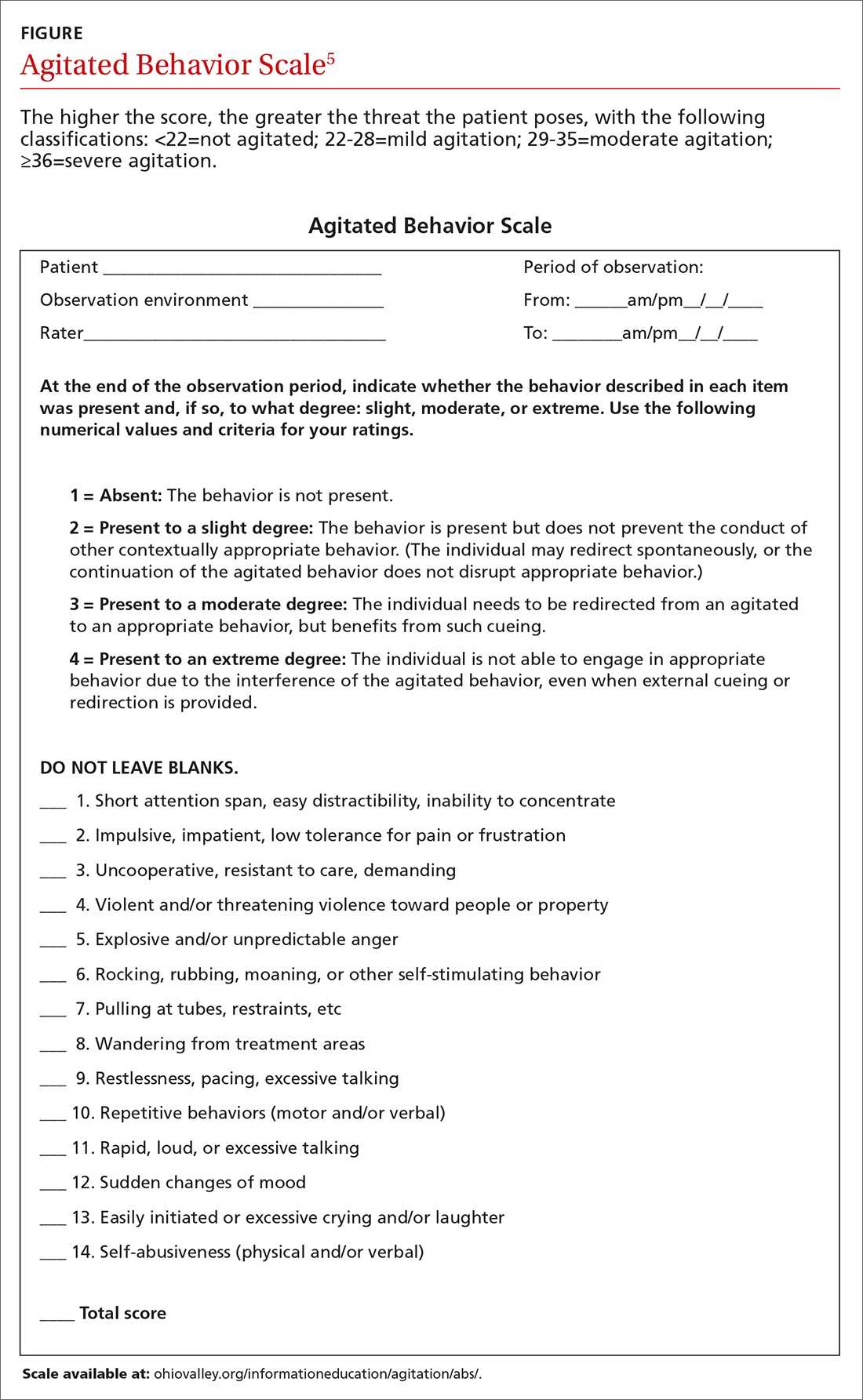

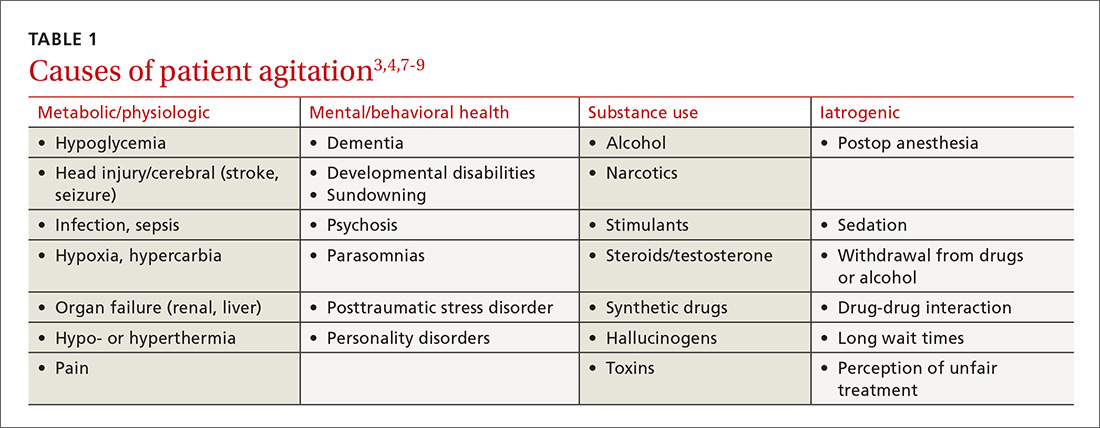

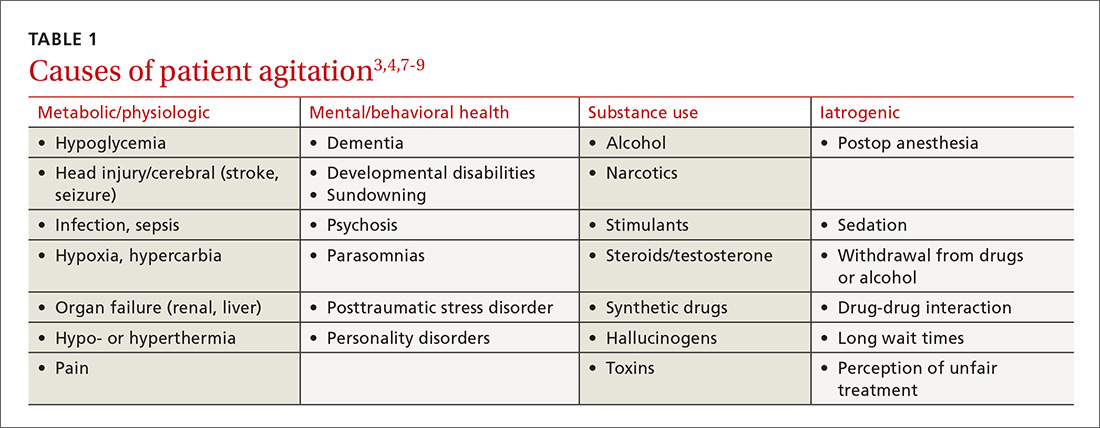

The causes of agitation can be grouped into categories: those due to a general medical condition, those due to a psychiatric condition, and those due to drug intoxication and/or withdrawal.7 We have chosen to add a fourth category—iatrogenic (see TABLE 13,4,7-9). They are not distinct categories, as there is sometimes overlap among areas.

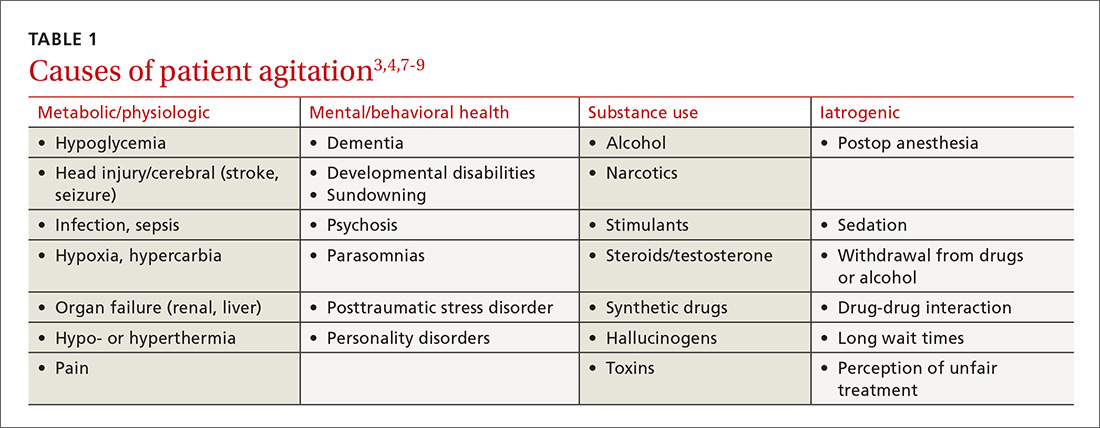

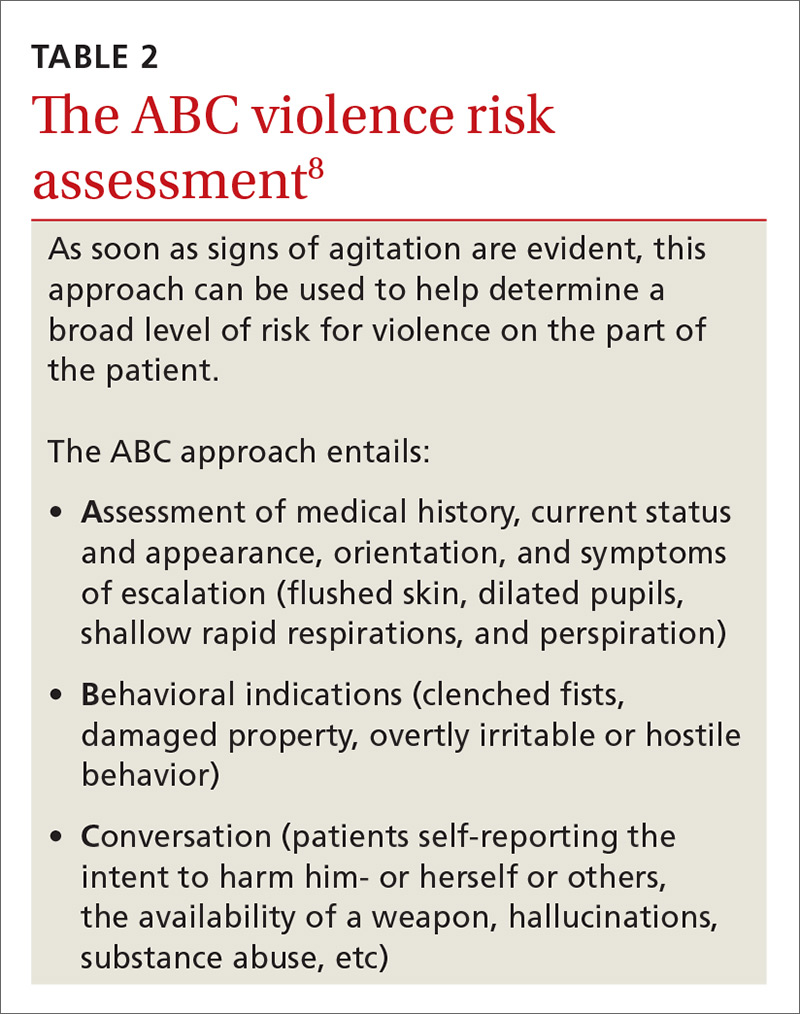

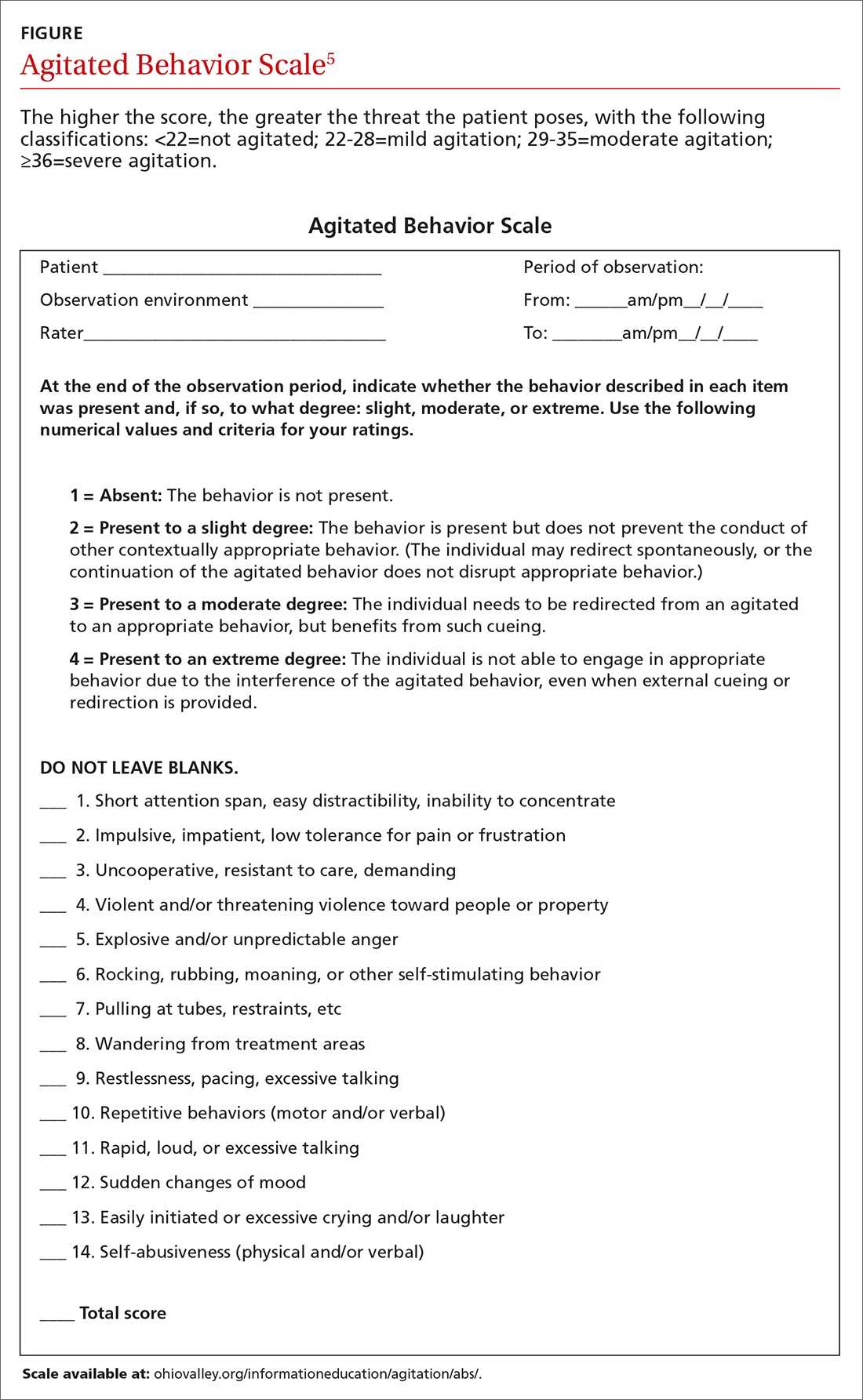

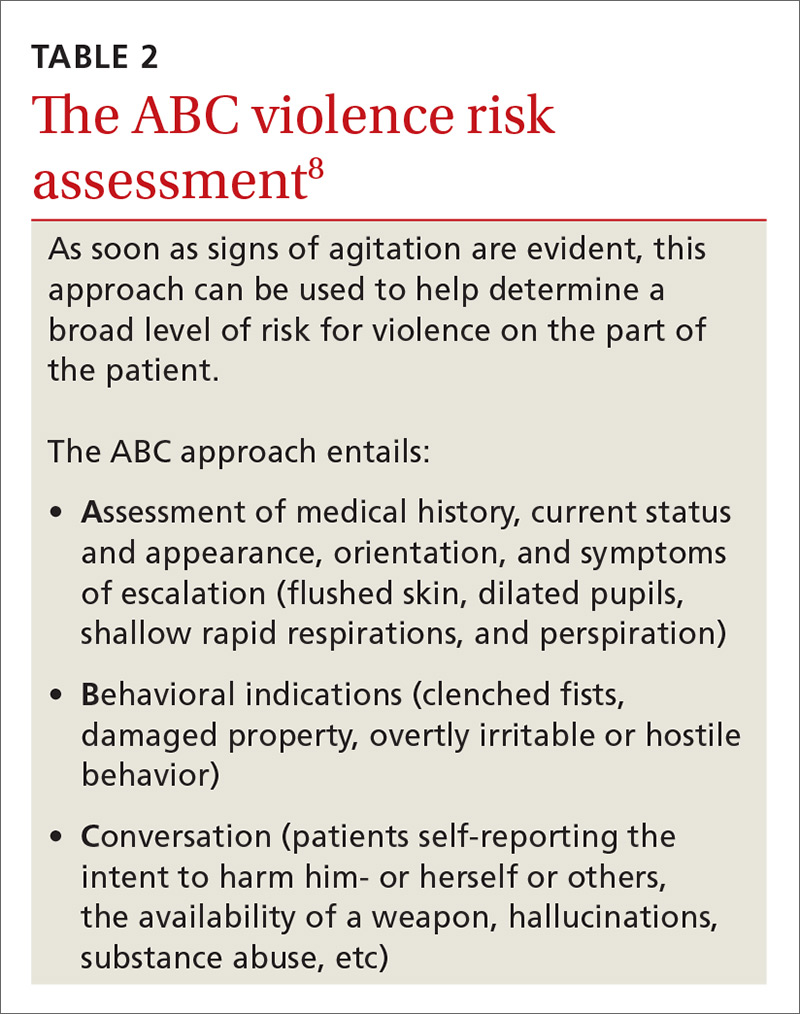

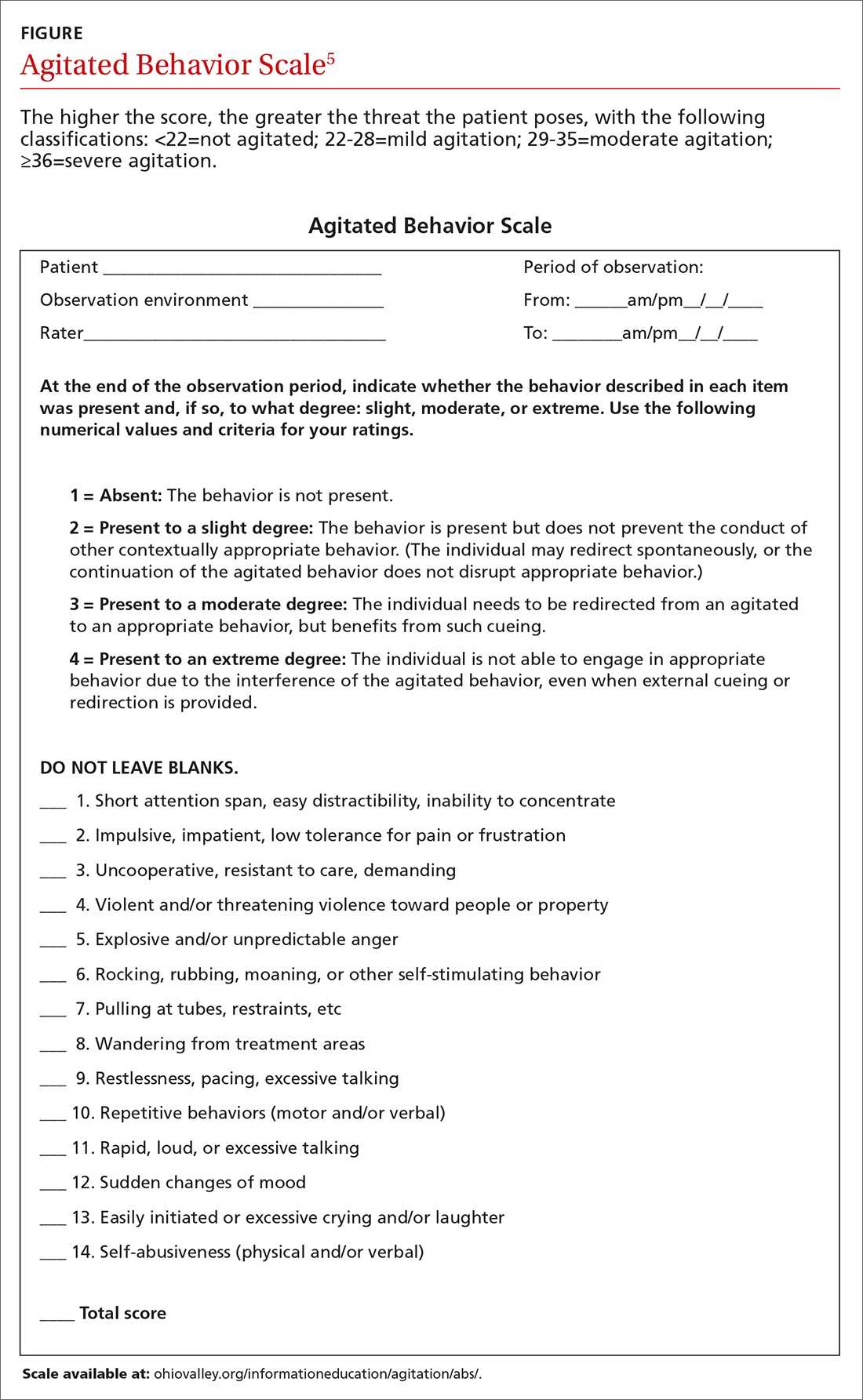

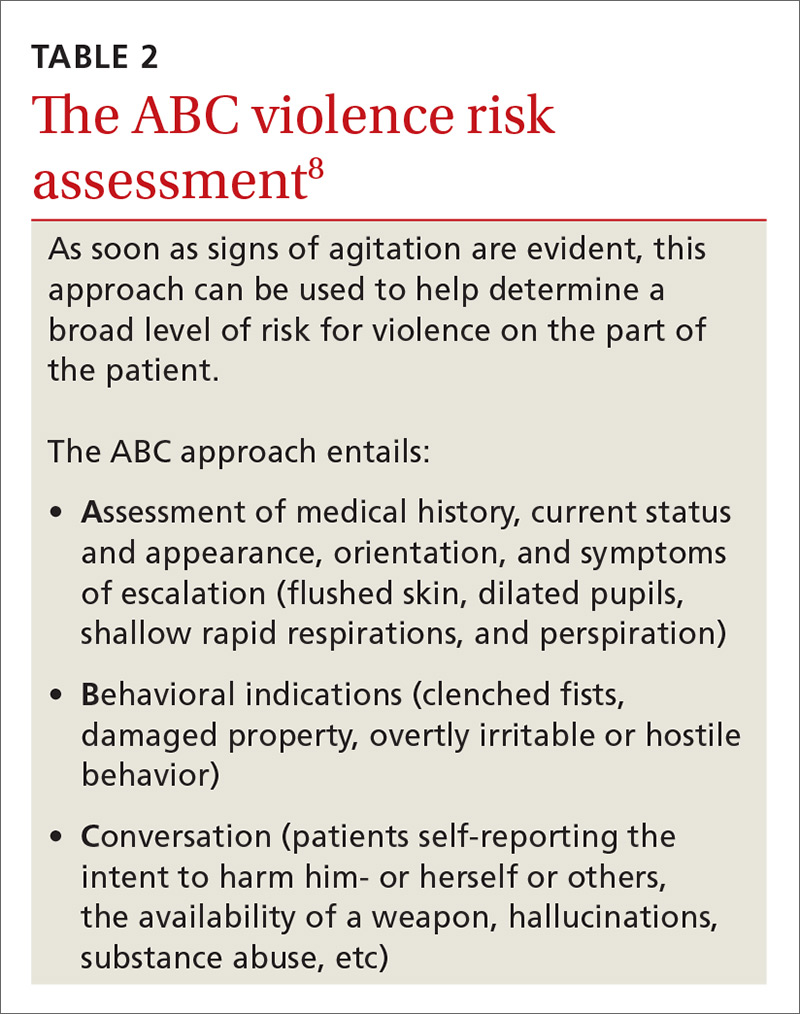

Determining the level of agitation. Various scales and approaches can help determine the level of agitation in a patient (eg, the Agitated Behavior Scale [ABS; FIGURE];5 the Behavioral Activity Rating Scale [BARS]10) and the risk for violence (eg, the ABC violence risk assessment,

Scales like the ABS should be employed as soon as a patient shows signs of agitation sufficient to warrant intervention. The idea is for the family physician (FP) to be familiar enough with the tool to be able to mentally check it off, fill it out when time permits, and keep it in the patient’s chart. The first version of the form serves as a baseline so that if care is handed off to another provider, that provider can monitor whether signs and symptoms are improving or worsening.

Setting often drives the solution

Much of the evidence-based research on managing patient agitation and violence stems from inpatient psychiatric and emergency department (ED) settings. To make other health care providers aware of the experience gained in those settings, the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry created Project BETA (Best Practices in Evaluation and Treatment of Agitation). This project is designed to help promote consistency across health care settings and specialties in the way clinicians respond to agitated patients and to emphasize for all health care providers the availability of more than just pharmacologic approaches.7

De-escalating the situation. General tenets of de-escalation apply across practice settings. Among them:

- Stay calm. Avoid aggressive postures and prolonged eye contact.

- Be nonconfrontational. Acknowledge the patient’s frustration/perceptions and ask open-ended questions.

- Assess available resources such as clinical team members, family members, and silent alarms.

- Manage the situation and the patient’s underlying issues/diagnoses. This includes mobilizing other patients to avoid collateral damage and exploring solutions with the patient.

For more on de-escalation tools, see (TABLE 34,6,9,11).

Your setting matters. It’s worth noting that the settings in which clinicians practice greatly influence the resources available to de-escalate a situation and ensure the safety of the patient and others.7 The review that follows provides some issues—and tips—that are unique to different practice settings.

Ambulatory settings

Sim and colleagues9 noted that aggressive behavior in the general practice setting may stem not only from factors related to the patient’s own physical or psychological discomfort, but from patients feeling that they are being treated unfairly, whether it be because of wait times, uncomfortable waiting conditions, or something else. A number of international studies have shown high rates of abuse toward FPs.9,12 Of 831 primary care physicians surveyed in a German study, close to three-quarters indicated that within the last year, they had experienced aggression (ranging from verbal abuse and threats to physical violence and property damage) from a patient.12 This statistic increased to 91% when it included the length of their career.

Bell13 suggests that physicians be aware that transference and countertransference issues are often at play when dealing with hostile or potentially violent patients. Suggestions to prevent aggression include some practice-level approaches (eg, providing waiting room distractions, making patients aware of potential delays), as well as being aware of nonverbal cues suggesting increased agitation (eg, clenched fists, crossed arms, chin thrusts, finger pointing).9

Group practice

An FP who practices with other health care providers and clinical staff has a built-in team that can assist with de-escalation. When meeting with a patient who has a history of violence or agitation in an exam room or office, try to ensure that you can get to an exit quickly if necessary. Also, alert staff to any concerns, and have a system for at least one staff member to check in periodically during the visit.

It is also helpful to develop an evacuation plan and create a “panic room” or “safe zone” for emergencies.14,15 Such a space may be nothing more than an area or room for staff to gather. It should have access to the police or other emergency services via a land and/or cell phone line.

Solo practice

If you practice alone, institute safeguards whereby a colleague (at a different practice, building, or location) can be alerted if concerns arise. In addition, consider the following precautions: locking the door when alone after hours, screening potential patients, having a way to call for help (keep the number for the local police station and ED readily available), prohibiting potential weapons (as some states allow them to be carried), and learning some form of self-defense.15

Resources exist that offer guidelines for developing policies and procedures, checklists, and sample incident forms (eg, the International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety; iahss.org). Other organizations that can help with the development of a preparedness plan include the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/workplaceviolence/evaluation.html), the Department of Homeland Security (https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/ISC%20Violence%20in%20%20the%20Federal%20Workplace%20Guide%20April%202013.pdf), and The Joint Commission (https://www.jointcommission.org/workplace_violence.aspx).

Long- and short-term care facilities

In long-term care settings, such as nursing homes, and shorter-term care settings, such as rehabilitation facilities, agitation may stem from causes related to a head injury or dementia or from living in an unfamiliar environment. Assessment can be accomplished using a formal scale (eg, the ABS), as well as by identifying potential underlying health-related factors that can lead to agitation, such as pain, an infection, bowel and bladder issues, seizures, wounds, endocrine anomalies, cardiac or pulmonary problems, gastrointestinal dysfunction, and metabolic abnormalities.3

Modify the environment. For this population, a primary approach involves modifying the environment to decrease the likelihood of agitation. This may involve decreasing noise or light or ensuring adequate levels of stimulation. Preventing disorientation can be addressed through verbal and visual reminders of the date, schedule, etc. If a particular situation or activity is identified as a source of agitation, attempts at modifications are called for.3

For patients with dementia, the American Psychiatric Association recommends using the lowest effective dose of an antipsychotic in conjunction with environmental and behavioral measures.16 A benzodiazepine (lorazepam, oxazepam) may be used for infrequent agitation. Trazodone or a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor are alternatives for those without psychosis or who are intolerant to antipsychotics.16

For individuals in a rehabilitation setting, agitation can impede participation in therapy and has been associated with poorer functioning at the time of discharge.3 Agitation can also be disruptive and lead to distress for family members and caregivers, as well as for fellow patients. And because this environment has a greater likelihood of visitors unrelated to the patient being exposed to the aberrant behavior, it is especially important to have established policies and procedures for de-escalation in place.

Home care

More and more FPs and residents are conducting home visits. That’s because the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine now include integrating a patient’s care across settings—including the home.17 Those who do provide home care may find themselves in circumstances similar to those of domestic disputes.

The German study mentioned earlier of more than 800 primary care physicians found that while the vast majority of physicians felt safe in their offices, 66% of female doctors and 34% of male doctors did not feel safe making home visits.12

Know the neighborhood. There’s no doubt that working in the home health sector makes one vulnerable. More than 61% of home care workers report workplace violence annually.18,19 An action plan, as well as established policies and procedures, are essential when making home visits. Prior to the visit, be aware of the community and the location of the nearest police department and hospital.

Unwin and Tatum20 suggest not wearing a white coat or carrying a doctor’s bag so as not to stand out as a physician in neighborhoods where personal safety is an issue. Make sure that your cell phone is fully charged and that there is a GPS mechanism activated that allows others to locate you.21 Note the available exits in a patient’s home, and position yourself near them, if possible. Have someone call or text you at predetermined times so that the absence of a response from you will alert someone to send help.

In such situations, it is imperative to remain calm and to use the same verbal de-escalation techniques (TABLE 34,6,9,11) that would be used in any other health care setting. It is prudent to set expectations for the patient and family members prior to the home visit regarding the tools and services that will be provided in the home setting and the limitations in terms of scope of practice.

Emergency department

The ED is one of the most common settings for patient agitation and violence within the health care continuum.22 Providers must quickly determine the cause of the agitation while de-escalating the situation and ensuring that they do not miss a pertinent medical finding related to a time-sensitive issue, such as an intracerebral bleed or poisoning.7 In addition, the ED is usually heavily populated, providing an opportunity for tremendous collateral human damage should the violence escalate or weapons be deployed. The upside is that many EDs are now staffed with security personnel and, depending on the community, police officers may be on the premises or in the vicinity.22

Etiologies for agitation in the ED can range from ingestion of unknown or unidentified substances to psychiatric or medical conditions. Knowledge of etiology is necessary prior to initiation of treatment.4

As in other settings, the safety of the patient and others present is of utmost importance. Key recommendations for managing agitated patients in the ED include: 4

- Have an established plan for the management of agitated patients.

- Identify signs of agitation early, and complete an agitation rating scale.

- Attempt verbal de-escalation before using medication whenever possible.

- Employ a “show of concern” rather than “a show of force” in response to escalating agitation/violence. Doing so can strengthen the perception that interventions are coming from a place of caring.

- Use physical restraint as a last resort. When used, it should be with the intention of protecting the patient and those present, rather than as punishment.

Inpatient units

Unlike the ED, patients on units generally have a working diagnosis, and the provider has some background information with which to work, such as laboratory test results and radiology reports, facilitating more expedient and accurate situational assessment. However, the recommendations for assessment and early identification, as described for the ED, still apply.

If a provider finds him- or herself in an escalating situation, the call bells located in the rooms are of use. An alternative is to call out for help from someone in the hallway. One needs to be aware of the current policies and procedures for de-escalation, as some facilities have a specific “code” that is called for such occasions.19

Postop delirium is a common cause of agitation in the inpatient setting. Ng and colleagues11 recommend a cognitive assessment before surgery to establish a baseline in order to determine the risk for delirium after surgery. Additionally, the FP must remain aware of preexisting conditions that may surface during a hospital stay, such as dehydration or unrecognized alcohol or medication withdrawal.

Medication choice should be based on the type of delirium. Hyperactive delirium (restlessness, emotional lability, hallucinations) and mixed delirium (a combination of signs of hyperactive and hypoactive dementia) both hold the potential for agitation and even violence. The approach to hyperactive delirium includes consideration of an antipsychotic medication, although the efficacy of antipsychotics is considered controversial. In the case of mixed delirium, behavioral and environmental modifications are useful (eg, reducing noise and early ambulation).11

No medications are registered with the US Food and Drug Administration for the management of delirium, and it is suggested that antipsychotics be considered only when other, less invasive, strategies have been attempted.23

Addressing caregiver stress, anxiety disorders afterward

Regardless of the setting in which FPs work, witnessing or being directly involved in a traumatic event puts one at risk for symptoms—or a full diagnosis—of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), acute stress disorder, or anxiety or mood disorders.24,25 Although findings vary, studies have found that as many as 12% of ED personnel meet the criteria for PTSD26,27 and 12% to 15% report having been threatened physically.28,29 More than half of physicians in another study had witnessed a physical attack.30

Physicians and other health care personnel who have experienced a traumatic incident, or offered help to another during an incident, may attempt to cope through avoidance, cutting down on work hours, leaving the work setting in which the event took place, or leaving the profession altogether.29,31,32

There is a paucity of methodologically sound research with regard to prevention and treatment of PTSD symptoms in this population.24 According to a 2002 Cochrane review, the effectiveness of individual, single-session debriefing does not have solid research support,33 and there are concerns about potential harms due to reliving the traumatic event when sessions are led by poorly trained debriefing staff.34-36

Critical incident stress debriefing (CISD), however, holds promise in terms of facilitating a return to pretrauma functioning based on studies of first responders.34,35 This may be because CISD follows a specific protocol and that group sessions may capitalize on the social support/camaraderie within a group that has undergone a traumatic event.34,35 It is important that those providing debriefing and support be well-trained.35

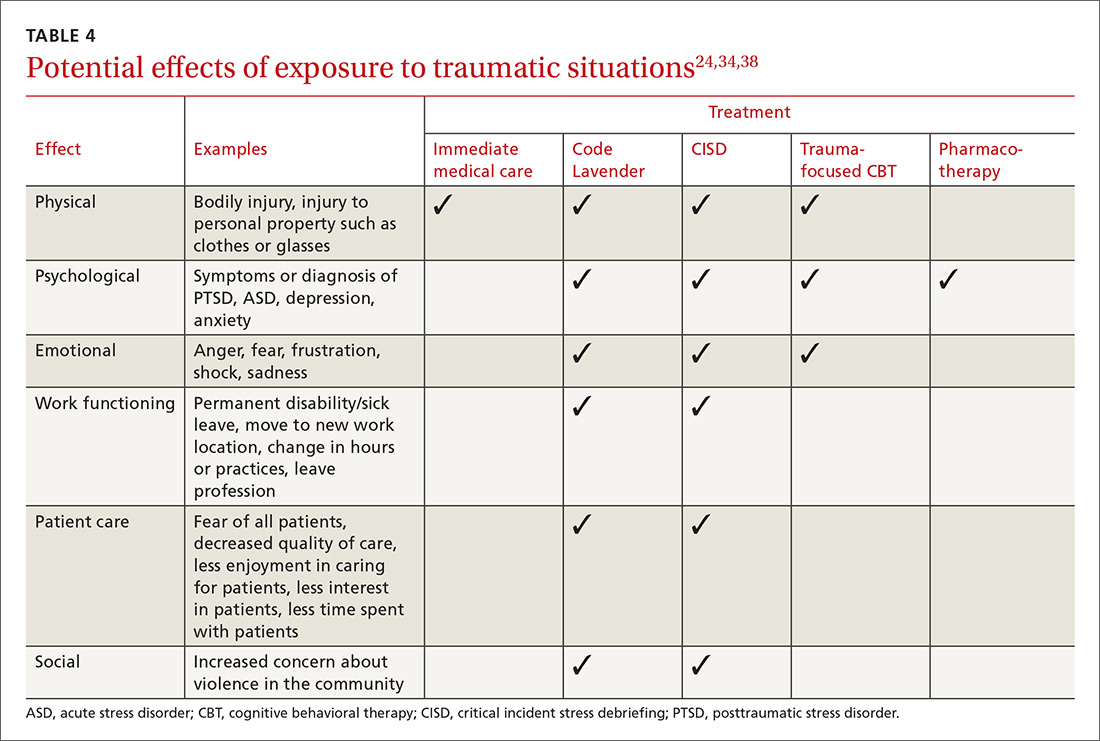

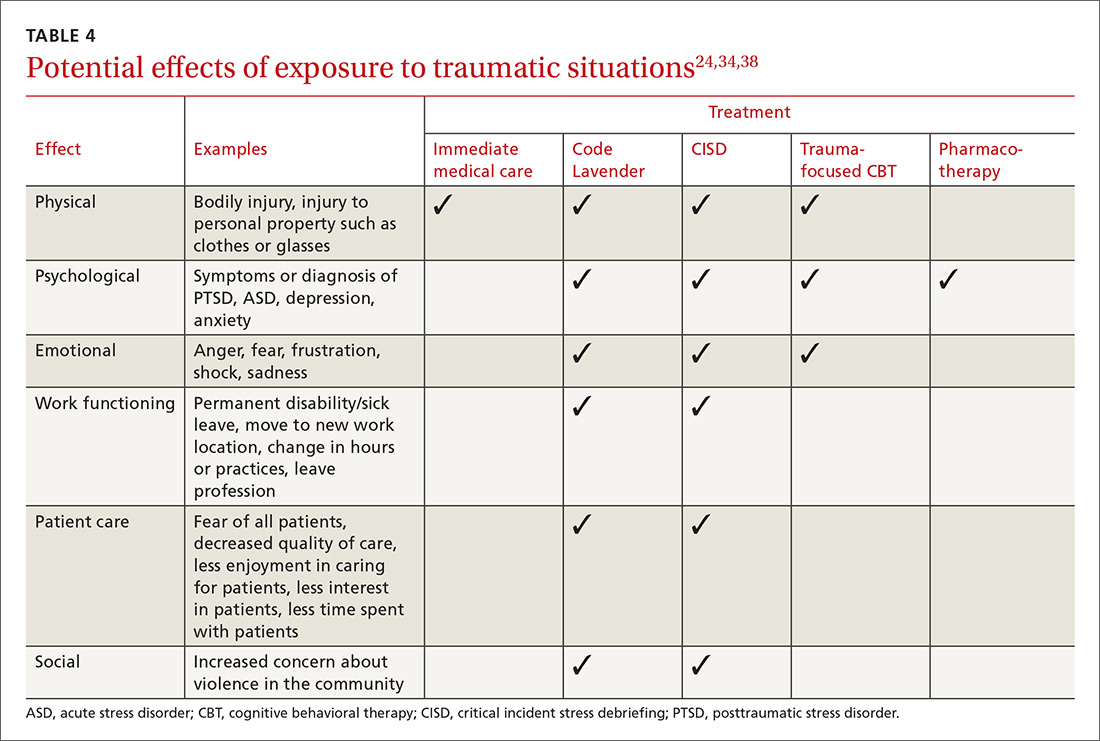

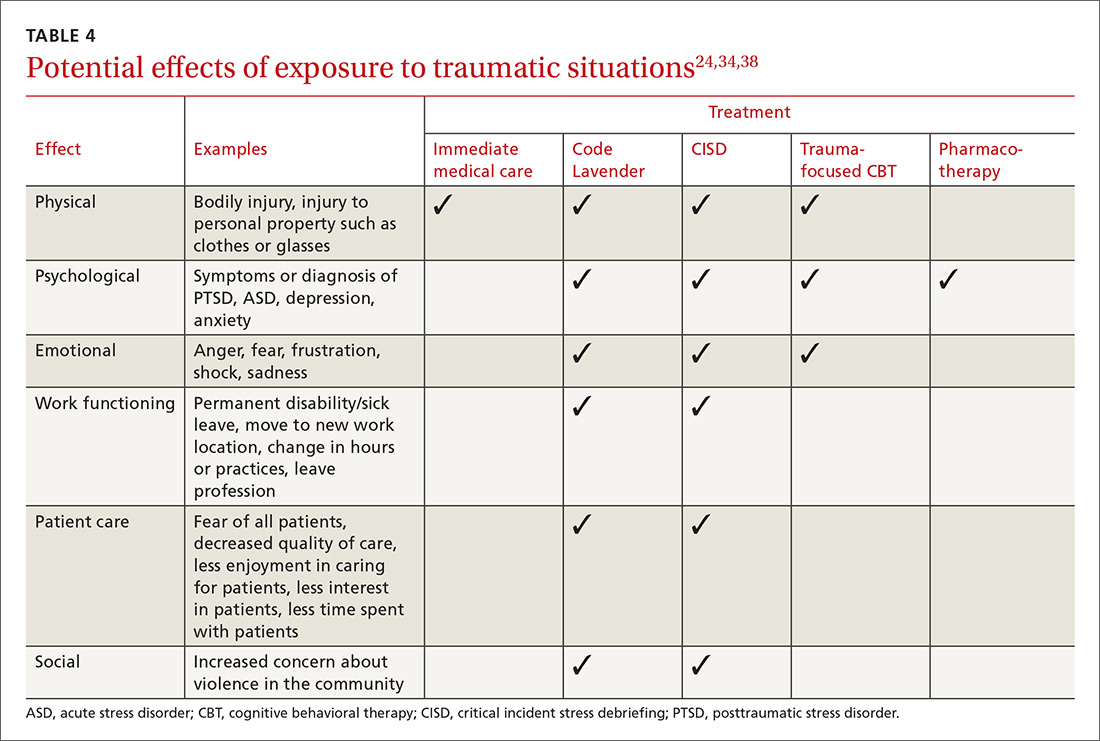

Debriefing, however, is not always sufficient, and those who appear to be affected on an ongoing basis may require individual treatment for PTSD symptoms. Evidence-based treatments for PTSD, such as trauma-focused psychotherapy and/or pharmacotherapy, may be considered37 (TABLE 424,34,38).

Ongoing support in the workplace. The Cleveland Clinic has developed a “Code Lavender” to combat stress in the workplace. Like a Code Blue for medical emergencies, a Code Lavender is called when a health care worker is in need of emotional or spiritual support.38 A provider who initiates the call is met by a team of holistic nurses within 30 minutes. The team provides Reiki and massage, healthy snacks and water, and lavender arm bands to remind the individual to relax for the rest of the day. Further opportunities for spiritual support, mindfulness training, counseling, and yoga may also be made available.

CASE Sensing that the situation with my patient might escalate, I lowered my voice, relaxed my shoulders, leaned casually against the desk, and asked him to tell me how I could best help him. As he spoke, I offered him a seat (by gesturing to the chair). I did this for 2 reasons: to move him away from blocking my exit from the room, and to put him at a lower level than me so that he was entirely in my view. I didn’t interrupt him as he spoke. I just nodded or tilted my head to show I was listening. In my mind, I played out the various scenarios that could ensue.

Fortunately, I was able to get him to relax enough for an assessment, which involved a more relevant history and the exam, which he agreed to once an aide had come into the room. He did not exhibit the concerning signs of flushed skin, dilated pupils, shallow rapid respirations, or perspiration. He did have a comorbid behavioral health issue, which we were able to address. His earlier behavioral indicators of agitation were controlled with verbal and physical cues on my part. Our conversation didn't reveal an intent to harm himself or others. In this case, physical restraints were not required. Throughout the encounter the door was left open, and the patient was reminded that we were there to help.

Once he left, I made the relevant notes in the chart regarding his agitated state at the start of the visit and his final state at the end of the visit so as to assist any other providers. We (TIM, MG) also held a quick debrief after the encounter with the office staff and decided that we needed to create a policy and protocol regarding how to handle such situations in the future.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tochi Iroku-Malize, MD, MPH, MBA, Family Medicine Department, Southside Hospital, 301 East Main Street, Bay Shore, NY 11706; [email protected].

1. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Workplace violence in healthcare: understanding the challenge. December 2015. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3826.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2018.

2. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Guidelines for preventing workplace violence for healthcare and social service workers. 2016. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/Publications/osha3148.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2017.

3. Mortimer DS, Berg W. Agitation in patients recovering from traumatic brain injury: nursing management. J Neurosci Nurs. 2017;49:25-30.

4. Wilson MP, Nordstrom K, Vilke GM. The agitated patient in the emergency department. Curr Emerg Hosp Med Rep. 2015;3:188-194.

5. Bogner JA, Corrigan JD, Bode RK, et al. Rating scale analysis of the Agitated Behavior Scale. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2000;15:656-669.

6. Gaynes BN, Brown CL, Lux LJ, et al. Preventing and de-escalating aggressive behavior among adult psychiatric patients: a systematic review of the evidence. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68:819-831.

7. Nordstrom K, Zun LS, Wilson MP, et al. Medical evaluation and triage of the agitated patient: consensus statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry Project Beta Medical Evaluation Workgroup. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13:3-10.

8. Sands N. Mental health triage: towards a model for nursing practice. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2007;14:243-249.

9. Sim MG, Wain T, Khong E. Aggressive behaviour - prevention and management in the general practice environment. Aust Fam Physician. 2011;40:866-872.

10. Swift RH, Harrigan EP, Cappelleri JC, et al. Validation of the behavioural activity rating scale (BARS): a novel measure of activity in agitated patients. J Psychiatr Res. 2002;36:87-95.

11. Ng J, Pan CX, Geube A, et al. Your postop patient is confused and agitated—next steps? J Fam Pract. 2015;64:361-366.

12. Vorderwülbecke F, Feistle M, Mehring M, et al. Aggression and violence against primary care physicians—a nationwide questionnaire survey. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:159-165.

13. Bell HS. Curbside consultation—a potentially violent patient? Am Fam Physician. 2000;61:2237-2238.

14. Taylor H. Patient violence against clinicians: managing the risk. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10:40-42.

15. Munsey C. How to stay safe in practice. APA Monitor. 2008;39:36.

16. Reus VI, Fochtmann LJ, Eyler AE, et al. The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline on the use of antipsychotics to treat agitation or psychosis in patients with dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:543-546.

17. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine. Revised July 1, 2017. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/120_family_medicine_2017-07-01.pdf . Accessed October 30, 2017.

18. Phillips JP. Workplace violence against health care workers in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1661-1669.

19. Hanson GC, Perrin NA, Moss H, et al. Workplace violence against homecare workers and its relationship with workers health outcomes: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:11.

20. Unwin BK, Tatum PE 3rd. House calls. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83:925-938.

21. Victor P. Safety tips for home visits from a veteran NYC social worker. National Association of Social Workers, New York. Available at: http://www.naswnyc.org/?489. Accessed June 1, 2017.

22. Kansagra SM, Rao SR, Sullivan AF, et al. A survey of workplace violence across 65 U.S. emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:1268-1274.

23. Meagher D, Agar MR, Teodorczuk A. Debate article: antipsychotic medications are clinically useful for the treatment of delirium. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017 Jul 30. doi: 10.1002/gps.4759. [Epub ahead of print].

24. Lanctot N, Guay S. The aftermath of workplace violence among healthcare workers: a systematic literature review of the consequences. Aggress Violent Behav. 2014;19:492-501.

25. Edward KL, Stephenson J, Ousey K, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of factors that relate to aggression perpetrated against nurses by patients/relatives or staff. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25:289-299.

26. Laposa JM, Alden LE. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the emergency room: exploration of a cognitive model. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:49-65.

27. Mills LD, Mills TJ. Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder among emergency medicine residents. J Emerg Med. 2005;28:1-4.

28. Laposa JM, Alden LE, Fullerton LM. Work stress and posttraumatic stress disorder in ED nurses/personnel. J Emerg Nurs. 2003;29:23-28.

29. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Workplace violence in healthcare: understanding the challenge. 2015. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3826.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2017.

30. Zafar W, Khan UR, Siddiqui SA, et al. Workplace violence and self-reported psychological health: coping with post-traumatic stress, mental distress, and burnout among physicians working in the emergency departments compared to other specialties in Pakistan. J Emerg Med. 2016;50:167-177.

31. de Boer J, Lok A, Van’t Verlaat E, et al. Work-related critical incidents in hospital-based health care providers and the risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms, anxiety, and depression: a meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:316-326.

32. Shah L, Annamalai J, Aye SN, et al. Key components and strategies utilized by nurses for de-escalation of aggression in psychiatric in-patients: a systematic review protocol. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep. 2016;14:109-118.

33. Rose S, Bisson J, Churchill R, et al. Psychological debriefing for preventing post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD000560.

34. Tuckey MR, Scott JE. Group critical incident stress debriefing with emergency services personnel: a randomized controlled trial. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2014;27:38-54.

35. Pack MJ. Critical incident stress management: a review of the literature with implications for social work. Int Soc Work. 2012;56: 608-627.

36. Forneris CA, Gartlehner G, Brownley KA, et al. Interventions to prevent post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:635-650.

37. Warner CH, Warner CM, Appenzeller GN, et al. Identifying and managing posttraumatic stress disorder. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:827-834.

38. Johnson B. Code lavender: initiating holistic rapid response at the Cleveland Clinic. Beginnings. 2014;34:10-11.

CASE A 40-year-old man came to our office slightly agitated. He had an acute illness that was minor in nature. However, he was not interested in answering my questions or undergoing a physical exam. The more I tried to proceed with the visit, the more agitated he became—pacing the room, muttering, avoiding eye contact. I was uncomfortable and knew that the situation could quickly escalate if it was not brought under control.

What steps would you take if this were your patient?

The scene described above occurred several years ago, but more recently, one of the institutions in my (TIM) area was affected by a shooter in the workplace. The apprehension felt by all of us who were on the periphery paled in comparison to what was experienced by those at the scene. The outcome was horrific. Communicating with those directly involved during, and immediately after, the event was heart-wrenching. The trauma that they continue to relive is unimaginable, and some are not yet able to return to work.

Situations involving agitated patients are not uncommon in health care settings, although ones that escalate to the level of a shooting are. And no matter where on the spectrum an incident involving an agitated patient falls, it can leave those involved with various levels of physical, emotional, and psychological harm. It can also leave everyone asking themselves: “How can I better prepare for such occurrences?”

This article offers some answers by providing tips and guidelines for handling agitated and/or violent patients in various settings.

[polldaddy:9948472]

Defining the problem, assessing its severity

Between 2011 and 2013, workplace assaults ranged from 23,540 and 25,630 annually, with 70% to 74% occurring in health care and social service settings.1,2

Agitation is defined as a state that may include inattention, disinhibition, emotional lability, impulsivity, motor restlessness, and aggression.3,4 Violence in a clinical setting may be seen as an extreme expression of agitation sufficient enough to cause harm to an individual or damage to an object.5,6

The causes of agitation can be grouped into categories: those due to a general medical condition, those due to a psychiatric condition, and those due to drug intoxication and/or withdrawal.7 We have chosen to add a fourth category—iatrogenic (see TABLE 13,4,7-9). They are not distinct categories, as there is sometimes overlap among areas.

Determining the level of agitation. Various scales and approaches can help determine the level of agitation in a patient (eg, the Agitated Behavior Scale [ABS; FIGURE];5 the Behavioral Activity Rating Scale [BARS]10) and the risk for violence (eg, the ABC violence risk assessment,

Scales like the ABS should be employed as soon as a patient shows signs of agitation sufficient to warrant intervention. The idea is for the family physician (FP) to be familiar enough with the tool to be able to mentally check it off, fill it out when time permits, and keep it in the patient’s chart. The first version of the form serves as a baseline so that if care is handed off to another provider, that provider can monitor whether signs and symptoms are improving or worsening.

Setting often drives the solution

Much of the evidence-based research on managing patient agitation and violence stems from inpatient psychiatric and emergency department (ED) settings. To make other health care providers aware of the experience gained in those settings, the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry created Project BETA (Best Practices in Evaluation and Treatment of Agitation). This project is designed to help promote consistency across health care settings and specialties in the way clinicians respond to agitated patients and to emphasize for all health care providers the availability of more than just pharmacologic approaches.7

De-escalating the situation. General tenets of de-escalation apply across practice settings. Among them:

- Stay calm. Avoid aggressive postures and prolonged eye contact.

- Be nonconfrontational. Acknowledge the patient’s frustration/perceptions and ask open-ended questions.

- Assess available resources such as clinical team members, family members, and silent alarms.

- Manage the situation and the patient’s underlying issues/diagnoses. This includes mobilizing other patients to avoid collateral damage and exploring solutions with the patient.

For more on de-escalation tools, see (TABLE 34,6,9,11).

Your setting matters. It’s worth noting that the settings in which clinicians practice greatly influence the resources available to de-escalate a situation and ensure the safety of the patient and others.7 The review that follows provides some issues—and tips—that are unique to different practice settings.

Ambulatory settings

Sim and colleagues9 noted that aggressive behavior in the general practice setting may stem not only from factors related to the patient’s own physical or psychological discomfort, but from patients feeling that they are being treated unfairly, whether it be because of wait times, uncomfortable waiting conditions, or something else. A number of international studies have shown high rates of abuse toward FPs.9,12 Of 831 primary care physicians surveyed in a German study, close to three-quarters indicated that within the last year, they had experienced aggression (ranging from verbal abuse and threats to physical violence and property damage) from a patient.12 This statistic increased to 91% when it included the length of their career.

Bell13 suggests that physicians be aware that transference and countertransference issues are often at play when dealing with hostile or potentially violent patients. Suggestions to prevent aggression include some practice-level approaches (eg, providing waiting room distractions, making patients aware of potential delays), as well as being aware of nonverbal cues suggesting increased agitation (eg, clenched fists, crossed arms, chin thrusts, finger pointing).9

Group practice

An FP who practices with other health care providers and clinical staff has a built-in team that can assist with de-escalation. When meeting with a patient who has a history of violence or agitation in an exam room or office, try to ensure that you can get to an exit quickly if necessary. Also, alert staff to any concerns, and have a system for at least one staff member to check in periodically during the visit.

It is also helpful to develop an evacuation plan and create a “panic room” or “safe zone” for emergencies.14,15 Such a space may be nothing more than an area or room for staff to gather. It should have access to the police or other emergency services via a land and/or cell phone line.

Solo practice

If you practice alone, institute safeguards whereby a colleague (at a different practice, building, or location) can be alerted if concerns arise. In addition, consider the following precautions: locking the door when alone after hours, screening potential patients, having a way to call for help (keep the number for the local police station and ED readily available), prohibiting potential weapons (as some states allow them to be carried), and learning some form of self-defense.15

Resources exist that offer guidelines for developing policies and procedures, checklists, and sample incident forms (eg, the International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety; iahss.org). Other organizations that can help with the development of a preparedness plan include the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/workplaceviolence/evaluation.html), the Department of Homeland Security (https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/ISC%20Violence%20in%20%20the%20Federal%20Workplace%20Guide%20April%202013.pdf), and The Joint Commission (https://www.jointcommission.org/workplace_violence.aspx).

Long- and short-term care facilities

In long-term care settings, such as nursing homes, and shorter-term care settings, such as rehabilitation facilities, agitation may stem from causes related to a head injury or dementia or from living in an unfamiliar environment. Assessment can be accomplished using a formal scale (eg, the ABS), as well as by identifying potential underlying health-related factors that can lead to agitation, such as pain, an infection, bowel and bladder issues, seizures, wounds, endocrine anomalies, cardiac or pulmonary problems, gastrointestinal dysfunction, and metabolic abnormalities.3

Modify the environment. For this population, a primary approach involves modifying the environment to decrease the likelihood of agitation. This may involve decreasing noise or light or ensuring adequate levels of stimulation. Preventing disorientation can be addressed through verbal and visual reminders of the date, schedule, etc. If a particular situation or activity is identified as a source of agitation, attempts at modifications are called for.3

For patients with dementia, the American Psychiatric Association recommends using the lowest effective dose of an antipsychotic in conjunction with environmental and behavioral measures.16 A benzodiazepine (lorazepam, oxazepam) may be used for infrequent agitation. Trazodone or a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor are alternatives for those without psychosis or who are intolerant to antipsychotics.16

For individuals in a rehabilitation setting, agitation can impede participation in therapy and has been associated with poorer functioning at the time of discharge.3 Agitation can also be disruptive and lead to distress for family members and caregivers, as well as for fellow patients. And because this environment has a greater likelihood of visitors unrelated to the patient being exposed to the aberrant behavior, it is especially important to have established policies and procedures for de-escalation in place.

Home care

More and more FPs and residents are conducting home visits. That’s because the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine now include integrating a patient’s care across settings—including the home.17 Those who do provide home care may find themselves in circumstances similar to those of domestic disputes.

The German study mentioned earlier of more than 800 primary care physicians found that while the vast majority of physicians felt safe in their offices, 66% of female doctors and 34% of male doctors did not feel safe making home visits.12

Know the neighborhood. There’s no doubt that working in the home health sector makes one vulnerable. More than 61% of home care workers report workplace violence annually.18,19 An action plan, as well as established policies and procedures, are essential when making home visits. Prior to the visit, be aware of the community and the location of the nearest police department and hospital.

Unwin and Tatum20 suggest not wearing a white coat or carrying a doctor’s bag so as not to stand out as a physician in neighborhoods where personal safety is an issue. Make sure that your cell phone is fully charged and that there is a GPS mechanism activated that allows others to locate you.21 Note the available exits in a patient’s home, and position yourself near them, if possible. Have someone call or text you at predetermined times so that the absence of a response from you will alert someone to send help.

In such situations, it is imperative to remain calm and to use the same verbal de-escalation techniques (TABLE 34,6,9,11) that would be used in any other health care setting. It is prudent to set expectations for the patient and family members prior to the home visit regarding the tools and services that will be provided in the home setting and the limitations in terms of scope of practice.

Emergency department

The ED is one of the most common settings for patient agitation and violence within the health care continuum.22 Providers must quickly determine the cause of the agitation while de-escalating the situation and ensuring that they do not miss a pertinent medical finding related to a time-sensitive issue, such as an intracerebral bleed or poisoning.7 In addition, the ED is usually heavily populated, providing an opportunity for tremendous collateral human damage should the violence escalate or weapons be deployed. The upside is that many EDs are now staffed with security personnel and, depending on the community, police officers may be on the premises or in the vicinity.22

Etiologies for agitation in the ED can range from ingestion of unknown or unidentified substances to psychiatric or medical conditions. Knowledge of etiology is necessary prior to initiation of treatment.4

As in other settings, the safety of the patient and others present is of utmost importance. Key recommendations for managing agitated patients in the ED include: 4

- Have an established plan for the management of agitated patients.

- Identify signs of agitation early, and complete an agitation rating scale.

- Attempt verbal de-escalation before using medication whenever possible.

- Employ a “show of concern” rather than “a show of force” in response to escalating agitation/violence. Doing so can strengthen the perception that interventions are coming from a place of caring.

- Use physical restraint as a last resort. When used, it should be with the intention of protecting the patient and those present, rather than as punishment.

Inpatient units

Unlike the ED, patients on units generally have a working diagnosis, and the provider has some background information with which to work, such as laboratory test results and radiology reports, facilitating more expedient and accurate situational assessment. However, the recommendations for assessment and early identification, as described for the ED, still apply.

If a provider finds him- or herself in an escalating situation, the call bells located in the rooms are of use. An alternative is to call out for help from someone in the hallway. One needs to be aware of the current policies and procedures for de-escalation, as some facilities have a specific “code” that is called for such occasions.19

Postop delirium is a common cause of agitation in the inpatient setting. Ng and colleagues11 recommend a cognitive assessment before surgery to establish a baseline in order to determine the risk for delirium after surgery. Additionally, the FP must remain aware of preexisting conditions that may surface during a hospital stay, such as dehydration or unrecognized alcohol or medication withdrawal.

Medication choice should be based on the type of delirium. Hyperactive delirium (restlessness, emotional lability, hallucinations) and mixed delirium (a combination of signs of hyperactive and hypoactive dementia) both hold the potential for agitation and even violence. The approach to hyperactive delirium includes consideration of an antipsychotic medication, although the efficacy of antipsychotics is considered controversial. In the case of mixed delirium, behavioral and environmental modifications are useful (eg, reducing noise and early ambulation).11

No medications are registered with the US Food and Drug Administration for the management of delirium, and it is suggested that antipsychotics be considered only when other, less invasive, strategies have been attempted.23

Addressing caregiver stress, anxiety disorders afterward

Regardless of the setting in which FPs work, witnessing or being directly involved in a traumatic event puts one at risk for symptoms—or a full diagnosis—of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), acute stress disorder, or anxiety or mood disorders.24,25 Although findings vary, studies have found that as many as 12% of ED personnel meet the criteria for PTSD26,27 and 12% to 15% report having been threatened physically.28,29 More than half of physicians in another study had witnessed a physical attack.30

Physicians and other health care personnel who have experienced a traumatic incident, or offered help to another during an incident, may attempt to cope through avoidance, cutting down on work hours, leaving the work setting in which the event took place, or leaving the profession altogether.29,31,32

There is a paucity of methodologically sound research with regard to prevention and treatment of PTSD symptoms in this population.24 According to a 2002 Cochrane review, the effectiveness of individual, single-session debriefing does not have solid research support,33 and there are concerns about potential harms due to reliving the traumatic event when sessions are led by poorly trained debriefing staff.34-36

Critical incident stress debriefing (CISD), however, holds promise in terms of facilitating a return to pretrauma functioning based on studies of first responders.34,35 This may be because CISD follows a specific protocol and that group sessions may capitalize on the social support/camaraderie within a group that has undergone a traumatic event.34,35 It is important that those providing debriefing and support be well-trained.35

Debriefing, however, is not always sufficient, and those who appear to be affected on an ongoing basis may require individual treatment for PTSD symptoms. Evidence-based treatments for PTSD, such as trauma-focused psychotherapy and/or pharmacotherapy, may be considered37 (TABLE 424,34,38).

Ongoing support in the workplace. The Cleveland Clinic has developed a “Code Lavender” to combat stress in the workplace. Like a Code Blue for medical emergencies, a Code Lavender is called when a health care worker is in need of emotional or spiritual support.38 A provider who initiates the call is met by a team of holistic nurses within 30 minutes. The team provides Reiki and massage, healthy snacks and water, and lavender arm bands to remind the individual to relax for the rest of the day. Further opportunities for spiritual support, mindfulness training, counseling, and yoga may also be made available.

CASE Sensing that the situation with my patient might escalate, I lowered my voice, relaxed my shoulders, leaned casually against the desk, and asked him to tell me how I could best help him. As he spoke, I offered him a seat (by gesturing to the chair). I did this for 2 reasons: to move him away from blocking my exit from the room, and to put him at a lower level than me so that he was entirely in my view. I didn’t interrupt him as he spoke. I just nodded or tilted my head to show I was listening. In my mind, I played out the various scenarios that could ensue.

Fortunately, I was able to get him to relax enough for an assessment, which involved a more relevant history and the exam, which he agreed to once an aide had come into the room. He did not exhibit the concerning signs of flushed skin, dilated pupils, shallow rapid respirations, or perspiration. He did have a comorbid behavioral health issue, which we were able to address. His earlier behavioral indicators of agitation were controlled with verbal and physical cues on my part. Our conversation didn't reveal an intent to harm himself or others. In this case, physical restraints were not required. Throughout the encounter the door was left open, and the patient was reminded that we were there to help.

Once he left, I made the relevant notes in the chart regarding his agitated state at the start of the visit and his final state at the end of the visit so as to assist any other providers. We (TIM, MG) also held a quick debrief after the encounter with the office staff and decided that we needed to create a policy and protocol regarding how to handle such situations in the future.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tochi Iroku-Malize, MD, MPH, MBA, Family Medicine Department, Southside Hospital, 301 East Main Street, Bay Shore, NY 11706; [email protected].

CASE A 40-year-old man came to our office slightly agitated. He had an acute illness that was minor in nature. However, he was not interested in answering my questions or undergoing a physical exam. The more I tried to proceed with the visit, the more agitated he became—pacing the room, muttering, avoiding eye contact. I was uncomfortable and knew that the situation could quickly escalate if it was not brought under control.

What steps would you take if this were your patient?

The scene described above occurred several years ago, but more recently, one of the institutions in my (TIM) area was affected by a shooter in the workplace. The apprehension felt by all of us who were on the periphery paled in comparison to what was experienced by those at the scene. The outcome was horrific. Communicating with those directly involved during, and immediately after, the event was heart-wrenching. The trauma that they continue to relive is unimaginable, and some are not yet able to return to work.

Situations involving agitated patients are not uncommon in health care settings, although ones that escalate to the level of a shooting are. And no matter where on the spectrum an incident involving an agitated patient falls, it can leave those involved with various levels of physical, emotional, and psychological harm. It can also leave everyone asking themselves: “How can I better prepare for such occurrences?”

This article offers some answers by providing tips and guidelines for handling agitated and/or violent patients in various settings.

[polldaddy:9948472]

Defining the problem, assessing its severity

Between 2011 and 2013, workplace assaults ranged from 23,540 and 25,630 annually, with 70% to 74% occurring in health care and social service settings.1,2

Agitation is defined as a state that may include inattention, disinhibition, emotional lability, impulsivity, motor restlessness, and aggression.3,4 Violence in a clinical setting may be seen as an extreme expression of agitation sufficient enough to cause harm to an individual or damage to an object.5,6

The causes of agitation can be grouped into categories: those due to a general medical condition, those due to a psychiatric condition, and those due to drug intoxication and/or withdrawal.7 We have chosen to add a fourth category—iatrogenic (see TABLE 13,4,7-9). They are not distinct categories, as there is sometimes overlap among areas.

Determining the level of agitation. Various scales and approaches can help determine the level of agitation in a patient (eg, the Agitated Behavior Scale [ABS; FIGURE];5 the Behavioral Activity Rating Scale [BARS]10) and the risk for violence (eg, the ABC violence risk assessment,

Scales like the ABS should be employed as soon as a patient shows signs of agitation sufficient to warrant intervention. The idea is for the family physician (FP) to be familiar enough with the tool to be able to mentally check it off, fill it out when time permits, and keep it in the patient’s chart. The first version of the form serves as a baseline so that if care is handed off to another provider, that provider can monitor whether signs and symptoms are improving or worsening.

Setting often drives the solution

Much of the evidence-based research on managing patient agitation and violence stems from inpatient psychiatric and emergency department (ED) settings. To make other health care providers aware of the experience gained in those settings, the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry created Project BETA (Best Practices in Evaluation and Treatment of Agitation). This project is designed to help promote consistency across health care settings and specialties in the way clinicians respond to agitated patients and to emphasize for all health care providers the availability of more than just pharmacologic approaches.7

De-escalating the situation. General tenets of de-escalation apply across practice settings. Among them:

- Stay calm. Avoid aggressive postures and prolonged eye contact.

- Be nonconfrontational. Acknowledge the patient’s frustration/perceptions and ask open-ended questions.

- Assess available resources such as clinical team members, family members, and silent alarms.

- Manage the situation and the patient’s underlying issues/diagnoses. This includes mobilizing other patients to avoid collateral damage and exploring solutions with the patient.

For more on de-escalation tools, see (TABLE 34,6,9,11).

Your setting matters. It’s worth noting that the settings in which clinicians practice greatly influence the resources available to de-escalate a situation and ensure the safety of the patient and others.7 The review that follows provides some issues—and tips—that are unique to different practice settings.

Ambulatory settings

Sim and colleagues9 noted that aggressive behavior in the general practice setting may stem not only from factors related to the patient’s own physical or psychological discomfort, but from patients feeling that they are being treated unfairly, whether it be because of wait times, uncomfortable waiting conditions, or something else. A number of international studies have shown high rates of abuse toward FPs.9,12 Of 831 primary care physicians surveyed in a German study, close to three-quarters indicated that within the last year, they had experienced aggression (ranging from verbal abuse and threats to physical violence and property damage) from a patient.12 This statistic increased to 91% when it included the length of their career.

Bell13 suggests that physicians be aware that transference and countertransference issues are often at play when dealing with hostile or potentially violent patients. Suggestions to prevent aggression include some practice-level approaches (eg, providing waiting room distractions, making patients aware of potential delays), as well as being aware of nonverbal cues suggesting increased agitation (eg, clenched fists, crossed arms, chin thrusts, finger pointing).9

Group practice

An FP who practices with other health care providers and clinical staff has a built-in team that can assist with de-escalation. When meeting with a patient who has a history of violence or agitation in an exam room or office, try to ensure that you can get to an exit quickly if necessary. Also, alert staff to any concerns, and have a system for at least one staff member to check in periodically during the visit.

It is also helpful to develop an evacuation plan and create a “panic room” or “safe zone” for emergencies.14,15 Such a space may be nothing more than an area or room for staff to gather. It should have access to the police or other emergency services via a land and/or cell phone line.

Solo practice

If you practice alone, institute safeguards whereby a colleague (at a different practice, building, or location) can be alerted if concerns arise. In addition, consider the following precautions: locking the door when alone after hours, screening potential patients, having a way to call for help (keep the number for the local police station and ED readily available), prohibiting potential weapons (as some states allow them to be carried), and learning some form of self-defense.15

Resources exist that offer guidelines for developing policies and procedures, checklists, and sample incident forms (eg, the International Association for Healthcare Security and Safety; iahss.org). Other organizations that can help with the development of a preparedness plan include the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (https://www.osha.gov/SLTC/workplaceviolence/evaluation.html), the Department of Homeland Security (https://www.dhs.gov/sites/default/files/publications/ISC%20Violence%20in%20%20the%20Federal%20Workplace%20Guide%20April%202013.pdf), and The Joint Commission (https://www.jointcommission.org/workplace_violence.aspx).

Long- and short-term care facilities

In long-term care settings, such as nursing homes, and shorter-term care settings, such as rehabilitation facilities, agitation may stem from causes related to a head injury or dementia or from living in an unfamiliar environment. Assessment can be accomplished using a formal scale (eg, the ABS), as well as by identifying potential underlying health-related factors that can lead to agitation, such as pain, an infection, bowel and bladder issues, seizures, wounds, endocrine anomalies, cardiac or pulmonary problems, gastrointestinal dysfunction, and metabolic abnormalities.3

Modify the environment. For this population, a primary approach involves modifying the environment to decrease the likelihood of agitation. This may involve decreasing noise or light or ensuring adequate levels of stimulation. Preventing disorientation can be addressed through verbal and visual reminders of the date, schedule, etc. If a particular situation or activity is identified as a source of agitation, attempts at modifications are called for.3

For patients with dementia, the American Psychiatric Association recommends using the lowest effective dose of an antipsychotic in conjunction with environmental and behavioral measures.16 A benzodiazepine (lorazepam, oxazepam) may be used for infrequent agitation. Trazodone or a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor are alternatives for those without psychosis or who are intolerant to antipsychotics.16

For individuals in a rehabilitation setting, agitation can impede participation in therapy and has been associated with poorer functioning at the time of discharge.3 Agitation can also be disruptive and lead to distress for family members and caregivers, as well as for fellow patients. And because this environment has a greater likelihood of visitors unrelated to the patient being exposed to the aberrant behavior, it is especially important to have established policies and procedures for de-escalation in place.

Home care

More and more FPs and residents are conducting home visits. That’s because the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine now include integrating a patient’s care across settings—including the home.17 Those who do provide home care may find themselves in circumstances similar to those of domestic disputes.

The German study mentioned earlier of more than 800 primary care physicians found that while the vast majority of physicians felt safe in their offices, 66% of female doctors and 34% of male doctors did not feel safe making home visits.12

Know the neighborhood. There’s no doubt that working in the home health sector makes one vulnerable. More than 61% of home care workers report workplace violence annually.18,19 An action plan, as well as established policies and procedures, are essential when making home visits. Prior to the visit, be aware of the community and the location of the nearest police department and hospital.

Unwin and Tatum20 suggest not wearing a white coat or carrying a doctor’s bag so as not to stand out as a physician in neighborhoods where personal safety is an issue. Make sure that your cell phone is fully charged and that there is a GPS mechanism activated that allows others to locate you.21 Note the available exits in a patient’s home, and position yourself near them, if possible. Have someone call or text you at predetermined times so that the absence of a response from you will alert someone to send help.

In such situations, it is imperative to remain calm and to use the same verbal de-escalation techniques (TABLE 34,6,9,11) that would be used in any other health care setting. It is prudent to set expectations for the patient and family members prior to the home visit regarding the tools and services that will be provided in the home setting and the limitations in terms of scope of practice.

Emergency department

The ED is one of the most common settings for patient agitation and violence within the health care continuum.22 Providers must quickly determine the cause of the agitation while de-escalating the situation and ensuring that they do not miss a pertinent medical finding related to a time-sensitive issue, such as an intracerebral bleed or poisoning.7 In addition, the ED is usually heavily populated, providing an opportunity for tremendous collateral human damage should the violence escalate or weapons be deployed. The upside is that many EDs are now staffed with security personnel and, depending on the community, police officers may be on the premises or in the vicinity.22

Etiologies for agitation in the ED can range from ingestion of unknown or unidentified substances to psychiatric or medical conditions. Knowledge of etiology is necessary prior to initiation of treatment.4

As in other settings, the safety of the patient and others present is of utmost importance. Key recommendations for managing agitated patients in the ED include: 4

- Have an established plan for the management of agitated patients.

- Identify signs of agitation early, and complete an agitation rating scale.

- Attempt verbal de-escalation before using medication whenever possible.

- Employ a “show of concern” rather than “a show of force” in response to escalating agitation/violence. Doing so can strengthen the perception that interventions are coming from a place of caring.

- Use physical restraint as a last resort. When used, it should be with the intention of protecting the patient and those present, rather than as punishment.

Inpatient units

Unlike the ED, patients on units generally have a working diagnosis, and the provider has some background information with which to work, such as laboratory test results and radiology reports, facilitating more expedient and accurate situational assessment. However, the recommendations for assessment and early identification, as described for the ED, still apply.

If a provider finds him- or herself in an escalating situation, the call bells located in the rooms are of use. An alternative is to call out for help from someone in the hallway. One needs to be aware of the current policies and procedures for de-escalation, as some facilities have a specific “code” that is called for such occasions.19

Postop delirium is a common cause of agitation in the inpatient setting. Ng and colleagues11 recommend a cognitive assessment before surgery to establish a baseline in order to determine the risk for delirium after surgery. Additionally, the FP must remain aware of preexisting conditions that may surface during a hospital stay, such as dehydration or unrecognized alcohol or medication withdrawal.

Medication choice should be based on the type of delirium. Hyperactive delirium (restlessness, emotional lability, hallucinations) and mixed delirium (a combination of signs of hyperactive and hypoactive dementia) both hold the potential for agitation and even violence. The approach to hyperactive delirium includes consideration of an antipsychotic medication, although the efficacy of antipsychotics is considered controversial. In the case of mixed delirium, behavioral and environmental modifications are useful (eg, reducing noise and early ambulation).11

No medications are registered with the US Food and Drug Administration for the management of delirium, and it is suggested that antipsychotics be considered only when other, less invasive, strategies have been attempted.23

Addressing caregiver stress, anxiety disorders afterward

Regardless of the setting in which FPs work, witnessing or being directly involved in a traumatic event puts one at risk for symptoms—or a full diagnosis—of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), acute stress disorder, or anxiety or mood disorders.24,25 Although findings vary, studies have found that as many as 12% of ED personnel meet the criteria for PTSD26,27 and 12% to 15% report having been threatened physically.28,29 More than half of physicians in another study had witnessed a physical attack.30

Physicians and other health care personnel who have experienced a traumatic incident, or offered help to another during an incident, may attempt to cope through avoidance, cutting down on work hours, leaving the work setting in which the event took place, or leaving the profession altogether.29,31,32

There is a paucity of methodologically sound research with regard to prevention and treatment of PTSD symptoms in this population.24 According to a 2002 Cochrane review, the effectiveness of individual, single-session debriefing does not have solid research support,33 and there are concerns about potential harms due to reliving the traumatic event when sessions are led by poorly trained debriefing staff.34-36

Critical incident stress debriefing (CISD), however, holds promise in terms of facilitating a return to pretrauma functioning based on studies of first responders.34,35 This may be because CISD follows a specific protocol and that group sessions may capitalize on the social support/camaraderie within a group that has undergone a traumatic event.34,35 It is important that those providing debriefing and support be well-trained.35

Debriefing, however, is not always sufficient, and those who appear to be affected on an ongoing basis may require individual treatment for PTSD symptoms. Evidence-based treatments for PTSD, such as trauma-focused psychotherapy and/or pharmacotherapy, may be considered37 (TABLE 424,34,38).

Ongoing support in the workplace. The Cleveland Clinic has developed a “Code Lavender” to combat stress in the workplace. Like a Code Blue for medical emergencies, a Code Lavender is called when a health care worker is in need of emotional or spiritual support.38 A provider who initiates the call is met by a team of holistic nurses within 30 minutes. The team provides Reiki and massage, healthy snacks and water, and lavender arm bands to remind the individual to relax for the rest of the day. Further opportunities for spiritual support, mindfulness training, counseling, and yoga may also be made available.

CASE Sensing that the situation with my patient might escalate, I lowered my voice, relaxed my shoulders, leaned casually against the desk, and asked him to tell me how I could best help him. As he spoke, I offered him a seat (by gesturing to the chair). I did this for 2 reasons: to move him away from blocking my exit from the room, and to put him at a lower level than me so that he was entirely in my view. I didn’t interrupt him as he spoke. I just nodded or tilted my head to show I was listening. In my mind, I played out the various scenarios that could ensue.

Fortunately, I was able to get him to relax enough for an assessment, which involved a more relevant history and the exam, which he agreed to once an aide had come into the room. He did not exhibit the concerning signs of flushed skin, dilated pupils, shallow rapid respirations, or perspiration. He did have a comorbid behavioral health issue, which we were able to address. His earlier behavioral indicators of agitation were controlled with verbal and physical cues on my part. Our conversation didn't reveal an intent to harm himself or others. In this case, physical restraints were not required. Throughout the encounter the door was left open, and the patient was reminded that we were there to help.

Once he left, I made the relevant notes in the chart regarding his agitated state at the start of the visit and his final state at the end of the visit so as to assist any other providers. We (TIM, MG) also held a quick debrief after the encounter with the office staff and decided that we needed to create a policy and protocol regarding how to handle such situations in the future.

CORRESPONDENCE

Tochi Iroku-Malize, MD, MPH, MBA, Family Medicine Department, Southside Hospital, 301 East Main Street, Bay Shore, NY 11706; [email protected].

1. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Workplace violence in healthcare: understanding the challenge. December 2015. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3826.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2018.

2. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Guidelines for preventing workplace violence for healthcare and social service workers. 2016. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/Publications/osha3148.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2017.

3. Mortimer DS, Berg W. Agitation in patients recovering from traumatic brain injury: nursing management. J Neurosci Nurs. 2017;49:25-30.

4. Wilson MP, Nordstrom K, Vilke GM. The agitated patient in the emergency department. Curr Emerg Hosp Med Rep. 2015;3:188-194.

5. Bogner JA, Corrigan JD, Bode RK, et al. Rating scale analysis of the Agitated Behavior Scale. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2000;15:656-669.

6. Gaynes BN, Brown CL, Lux LJ, et al. Preventing and de-escalating aggressive behavior among adult psychiatric patients: a systematic review of the evidence. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68:819-831.

7. Nordstrom K, Zun LS, Wilson MP, et al. Medical evaluation and triage of the agitated patient: consensus statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry Project Beta Medical Evaluation Workgroup. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13:3-10.

8. Sands N. Mental health triage: towards a model for nursing practice. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2007;14:243-249.

9. Sim MG, Wain T, Khong E. Aggressive behaviour - prevention and management in the general practice environment. Aust Fam Physician. 2011;40:866-872.

10. Swift RH, Harrigan EP, Cappelleri JC, et al. Validation of the behavioural activity rating scale (BARS): a novel measure of activity in agitated patients. J Psychiatr Res. 2002;36:87-95.

11. Ng J, Pan CX, Geube A, et al. Your postop patient is confused and agitated—next steps? J Fam Pract. 2015;64:361-366.

12. Vorderwülbecke F, Feistle M, Mehring M, et al. Aggression and violence against primary care physicians—a nationwide questionnaire survey. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:159-165.

13. Bell HS. Curbside consultation—a potentially violent patient? Am Fam Physician. 2000;61:2237-2238.

14. Taylor H. Patient violence against clinicians: managing the risk. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10:40-42.

15. Munsey C. How to stay safe in practice. APA Monitor. 2008;39:36.

16. Reus VI, Fochtmann LJ, Eyler AE, et al. The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline on the use of antipsychotics to treat agitation or psychosis in patients with dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:543-546.

17. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine. Revised July 1, 2017. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/120_family_medicine_2017-07-01.pdf . Accessed October 30, 2017.

18. Phillips JP. Workplace violence against health care workers in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1661-1669.

19. Hanson GC, Perrin NA, Moss H, et al. Workplace violence against homecare workers and its relationship with workers health outcomes: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:11.

20. Unwin BK, Tatum PE 3rd. House calls. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83:925-938.

21. Victor P. Safety tips for home visits from a veteran NYC social worker. National Association of Social Workers, New York. Available at: http://www.naswnyc.org/?489. Accessed June 1, 2017.

22. Kansagra SM, Rao SR, Sullivan AF, et al. A survey of workplace violence across 65 U.S. emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:1268-1274.

23. Meagher D, Agar MR, Teodorczuk A. Debate article: antipsychotic medications are clinically useful for the treatment of delirium. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017 Jul 30. doi: 10.1002/gps.4759. [Epub ahead of print].

24. Lanctot N, Guay S. The aftermath of workplace violence among healthcare workers: a systematic literature review of the consequences. Aggress Violent Behav. 2014;19:492-501.

25. Edward KL, Stephenson J, Ousey K, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of factors that relate to aggression perpetrated against nurses by patients/relatives or staff. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25:289-299.

26. Laposa JM, Alden LE. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the emergency room: exploration of a cognitive model. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:49-65.

27. Mills LD, Mills TJ. Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder among emergency medicine residents. J Emerg Med. 2005;28:1-4.

28. Laposa JM, Alden LE, Fullerton LM. Work stress and posttraumatic stress disorder in ED nurses/personnel. J Emerg Nurs. 2003;29:23-28.

29. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Workplace violence in healthcare: understanding the challenge. 2015. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3826.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2017.

30. Zafar W, Khan UR, Siddiqui SA, et al. Workplace violence and self-reported psychological health: coping with post-traumatic stress, mental distress, and burnout among physicians working in the emergency departments compared to other specialties in Pakistan. J Emerg Med. 2016;50:167-177.

31. de Boer J, Lok A, Van’t Verlaat E, et al. Work-related critical incidents in hospital-based health care providers and the risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms, anxiety, and depression: a meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:316-326.

32. Shah L, Annamalai J, Aye SN, et al. Key components and strategies utilized by nurses for de-escalation of aggression in psychiatric in-patients: a systematic review protocol. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep. 2016;14:109-118.

33. Rose S, Bisson J, Churchill R, et al. Psychological debriefing for preventing post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD000560.

34. Tuckey MR, Scott JE. Group critical incident stress debriefing with emergency services personnel: a randomized controlled trial. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2014;27:38-54.

35. Pack MJ. Critical incident stress management: a review of the literature with implications for social work. Int Soc Work. 2012;56: 608-627.

36. Forneris CA, Gartlehner G, Brownley KA, et al. Interventions to prevent post-traumatic stress disorder: a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2013;44:635-650.

37. Warner CH, Warner CM, Appenzeller GN, et al. Identifying and managing posttraumatic stress disorder. Am Fam Physician. 2013;88:827-834.

38. Johnson B. Code lavender: initiating holistic rapid response at the Cleveland Clinic. Beginnings. 2014;34:10-11.

1. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Workplace violence in healthcare: understanding the challenge. December 2015. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3826.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2018.

2. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Guidelines for preventing workplace violence for healthcare and social service workers. 2016. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/Publications/osha3148.pdf. Accessed February 8, 2017.

3. Mortimer DS, Berg W. Agitation in patients recovering from traumatic brain injury: nursing management. J Neurosci Nurs. 2017;49:25-30.

4. Wilson MP, Nordstrom K, Vilke GM. The agitated patient in the emergency department. Curr Emerg Hosp Med Rep. 2015;3:188-194.

5. Bogner JA, Corrigan JD, Bode RK, et al. Rating scale analysis of the Agitated Behavior Scale. J Head Trauma Rehabil. 2000;15:656-669.

6. Gaynes BN, Brown CL, Lux LJ, et al. Preventing and de-escalating aggressive behavior among adult psychiatric patients: a systematic review of the evidence. Psychiatr Serv. 2017;68:819-831.

7. Nordstrom K, Zun LS, Wilson MP, et al. Medical evaluation and triage of the agitated patient: consensus statement of the American Association for Emergency Psychiatry Project Beta Medical Evaluation Workgroup. West J Emerg Med. 2012;13:3-10.

8. Sands N. Mental health triage: towards a model for nursing practice. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2007;14:243-249.

9. Sim MG, Wain T, Khong E. Aggressive behaviour - prevention and management in the general practice environment. Aust Fam Physician. 2011;40:866-872.

10. Swift RH, Harrigan EP, Cappelleri JC, et al. Validation of the behavioural activity rating scale (BARS): a novel measure of activity in agitated patients. J Psychiatr Res. 2002;36:87-95.

11. Ng J, Pan CX, Geube A, et al. Your postop patient is confused and agitated—next steps? J Fam Pract. 2015;64:361-366.

12. Vorderwülbecke F, Feistle M, Mehring M, et al. Aggression and violence against primary care physicians—a nationwide questionnaire survey. Dtsch Arztebl Int. 2015;112:159-165.

13. Bell HS. Curbside consultation—a potentially violent patient? Am Fam Physician. 2000;61:2237-2238.

14. Taylor H. Patient violence against clinicians: managing the risk. Innov Clin Neurosci. 2013;10:40-42.

15. Munsey C. How to stay safe in practice. APA Monitor. 2008;39:36.

16. Reus VI, Fochtmann LJ, Eyler AE, et al. The American Psychiatric Association practice guideline on the use of antipsychotics to treat agitation or psychosis in patients with dementia. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:543-546.

17. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine. Revised July 1, 2017. Available at: http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/120_family_medicine_2017-07-01.pdf . Accessed October 30, 2017.

18. Phillips JP. Workplace violence against health care workers in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2016;374:1661-1669.

19. Hanson GC, Perrin NA, Moss H, et al. Workplace violence against homecare workers and its relationship with workers health outcomes: a cross-sectional study. BMC Public Health. 2015;15:11.

20. Unwin BK, Tatum PE 3rd. House calls. Am Fam Physician. 2011;83:925-938.

21. Victor P. Safety tips for home visits from a veteran NYC social worker. National Association of Social Workers, New York. Available at: http://www.naswnyc.org/?489. Accessed June 1, 2017.

22. Kansagra SM, Rao SR, Sullivan AF, et al. A survey of workplace violence across 65 U.S. emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:1268-1274.

23. Meagher D, Agar MR, Teodorczuk A. Debate article: antipsychotic medications are clinically useful for the treatment of delirium. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2017 Jul 30. doi: 10.1002/gps.4759. [Epub ahead of print].

24. Lanctot N, Guay S. The aftermath of workplace violence among healthcare workers: a systematic literature review of the consequences. Aggress Violent Behav. 2014;19:492-501.

25. Edward KL, Stephenson J, Ousey K, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of factors that relate to aggression perpetrated against nurses by patients/relatives or staff. J Clin Nurs. 2016;25:289-299.

26. Laposa JM, Alden LE. Posttraumatic stress disorder in the emergency room: exploration of a cognitive model. Behav Res Ther. 2003;41:49-65.

27. Mills LD, Mills TJ. Symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder among emergency medicine residents. J Emerg Med. 2005;28:1-4.

28. Laposa JM, Alden LE, Fullerton LM. Work stress and posttraumatic stress disorder in ED nurses/personnel. J Emerg Nurs. 2003;29:23-28.

29. Occupational Safety and Health Administration. Workplace violence in healthcare: understanding the challenge. 2015. Available at: https://www.osha.gov/Publications/OSHA3826.pdf. Accessed June 1, 2017.

30. Zafar W, Khan UR, Siddiqui SA, et al. Workplace violence and self-reported psychological health: coping with post-traumatic stress, mental distress, and burnout among physicians working in the emergency departments compared to other specialties in Pakistan. J Emerg Med. 2016;50:167-177.

31. de Boer J, Lok A, Van’t Verlaat E, et al. Work-related critical incidents in hospital-based health care providers and the risk of post-traumatic stress symptoms, anxiety, and depression: a meta-analysis. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:316-326.

32. Shah L, Annamalai J, Aye SN, et al. Key components and strategies utilized by nurses for de-escalation of aggression in psychiatric in-patients: a systematic review protocol. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep. 2016;14:109-118.

33. Rose S, Bisson J, Churchill R, et al. Psychological debriefing for preventing post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;(2):CD000560.

34. Tuckey MR, Scott JE. Group critical incident stress debriefing with emergency services personnel: a randomized controlled trial. Anxiety Stress Coping. 2014;27:38-54.