User login

ORLANDO – The common challenge faced by clinicians in deciding whether or not to continue dual antiplatelet therapy beyond a year in a patient who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention has gotten easier.

Researchers have devised a simple, eight-element scoring system using information already available in a patient’s records to help determine whether an individual patient will be more likely to benefit from continuing or stopping dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT).

“The DAPT score may help clinicians decide who should and who should not be treated with extended DAPT,” Dr. Robert W. Yeh said at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

“This is a step forward for an issue we deal with daily, balancing an individual patient’s risk from ischemia and bleeding,” commented Dr. Alice Jacobs, professor of medicine at Boston University and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory and interventional cardiology at Boston Medical Center.

Dr. Yeh and his associates devised the DAPT score from the data collected in the DAPT study, which enrolled more than 25,000 patients and randomized about 10,000 to test whether patients fared better by stopping or continuing DAPT after completing their initial year of DAPT following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The DAPT study results showed that after 18 additional months, continuing DAPT cut the rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis by 1 percentage point and the combined rate of death, MI, or stroke by 1.6 percentage points, both statistically significant differences, compared with patients randomized to treatment with aspirin plus placebo. The results also showed that continued DAPT increased GUSTO moderate or severe bleeding events by 1 percentage point, compared with the control patients (N Engl J Med. 2014 Dec 4;371[23]:2155-66).

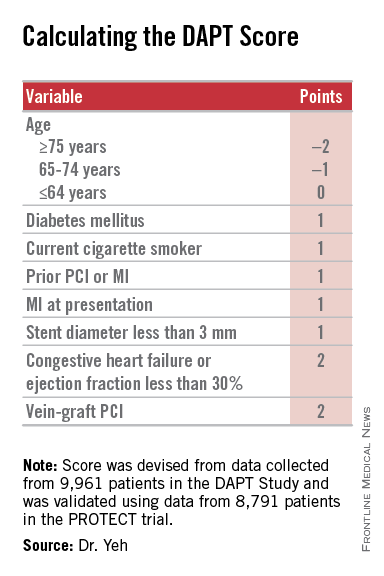

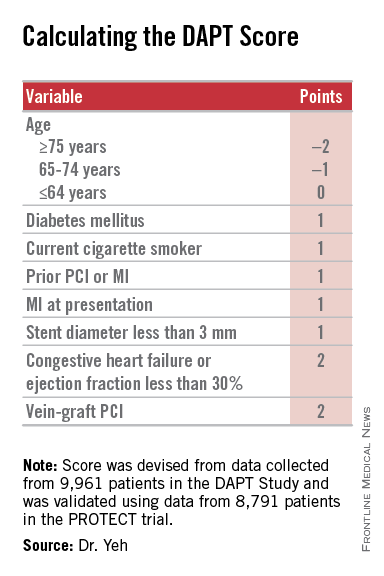

The researchers used data collected in the DAPT study to build risk models using patient- and procedure-specific variables that predicted the ischemic and bleeding outcomes, and then combined the two into a single model. That meant abandoning some variables that had significant impact on both outcomes.

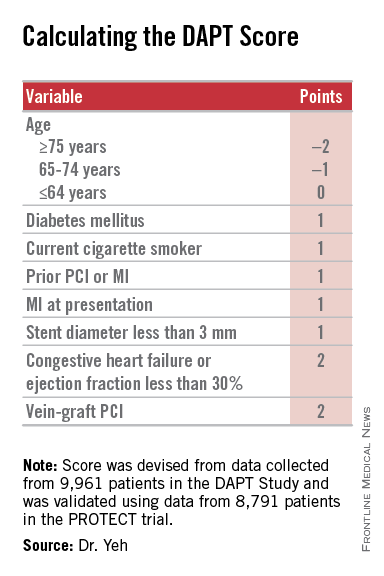

The result was a scoring system that includes eight variables that result in a score that ranges from –2 to 9. The analysis showed that a score of 1 or less identified patients for whom the risk for bleeding outweighs their potential gain by avoiding an ischemic event by about 2.5-fold, and hence likely would fare better by stopping DAPT. A score of 2 or higher flagged patients who benefited about eightfold more from avoided ischemic events, compared with their risk for a moderate or severe bleed.

Patient scores showed a classic bell-shaped curve, with roughly a quarter of the DAPT study patients having a score of 1 and about a quarter with a score of 2, about 16% had a score of 0 and about 16% had a score of 3, and about 8% had a score of –1 or –2, while about 9% had a score of 4 or more.

The investigators validated the scoring system using data collected in the PROTECT trial, which included 8,791 patients who underwent PCI during 2007-2008. Dr. Yeh acknowledged that the discrimination strength of the models he and his associated developed was “modest,” but added that its efficacy was greater than what has been shown in validation cohorts for the commonly used CH2ADS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scoring systems.

Dr. Yeh stressed that using the DAPT score “cannot trump clinical judgment.” He suggested that a clinician use the score to help facilitate a conversation with a PCI patient when the time comes to decide whether or not to continue DAPT beyond 1 year.

Other factors that could influence the decision include the length of the stented coronary lesions or prior radiation exposure to the patient’s coronary arteries, said Dr. Laura Mauri, who led the DAPT study and collaborated on developing the DAPT score. “It requires judgment to decide [on whether to continue DAPT] for patients who are on the borderline” for risk and benefit. “This gives patients a way to better understand what they might gain or lose” by continuing treatment. Without the quantification that the DAPT score provides, the balance of risk and benefit “is somewhat nebulous,” said Dr. Mauri, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Clinical Biometrics in the division of cardiovascular medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The investigators who ran the DAPT study realized several years before the study finished that development of the DAPT score was a critical part of applying the findings from the study into clinical practice, she said in an interview.

Dr. Yeh cautioned that the score is only appropriate for patients who match those enrolled into the DAPT study: patients who went through their first year post PCI on DAPT without having any ischemic or bleeding complications. For these patients, “we feel the DAPT score is incredibly valuable,” said Dr. Yeh, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. He and his associates are now using data from the DAPT study to model bleeding and ischemia risks during the first year following PCI to try to come up with risk models that can address DAPT use during this period.

Dr. Yeh and Dr. Mauri have placed a link to the electronic DAPT score calculator on the website for the DAPT study (www.daptstudy.org), and Dr. Yeh said that an app version will soon become available. Interventionalists in the programs that Dr. Yeh and Mauri are affiliated with have recently begun using the DAPT score calculator in their routine practice, Dr. Yeh said.

The DAPT study received funding from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Medtronic, Bristol-Myers Squib-Sanofi, Eli Lilly, and Daiichi Sankyo. Derivation of the DAPT score was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Yeh has received honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Merck. Dr. Jacobs had no disclosures. Dr. Mauri has been a consultant to Biotronik, Medtronic, and St. Jude and has received research funding from several companies.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

The DAPT score is a clever and innovative idea. It is a major step forward in helping clinicians decide which patients should continue dual antiplatelet therapy after safely completing a year on this therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention. The DAPT score was data driven and provides a tool to help personalize decision making with a simple, practical solution to a common clinical dilemma. It’s a welcome addition to our decision-making process.

The competing risks from bleeding events caused by continued dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) beyond 1 year and ischemic events caused by stopping DAPT creates difficulty in determining whether or not to continue or stop DAPT for an individual patient. The DAPT score helps make that decision.

|

| Mitchel L. Zoler/Frontline Medical News Dr. James de Lemos |

The analysis performed by Dr. Yeh and his associates produced a clear and convincing result. The primary caveat is that it is only applicable to patients who entered the randomized phase of the DAPT study, specifically patients who underwent a full first year of DAPT treatment following PCI without an ischemic or major bleeding event. I would like to see replication of the score’s validation in an additional data set, although few data sets exist that are suitable for such replication. Although the discrimination produced by the DAPT score is moderate, it compares favorably with other widely used clinical decision scores such as the CHA2ADS2-VASc.

The added decision-making ability facilitated by this score revises my interpretation of the results from the DAPT study. When the results of the trial appeared in 2014, I considered the outcome null because of the problem it highlighted in balancing the competing risks of ischemic and bleeding events when deciding about continuing DAPT beyond 1 year. The DAPT score helps produce a much clearer risk versus benefit decision for a sizable subset of patients who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention.

Dr. James de Lemos is a professor of medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and chief of the cardiology service at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas. He has received honoraria from Novo Nordisk and St. Jude and research funding from Roche Diagnostics and Abbott Diagnostics. He made these comments as the designated discussant for Dr. Yeh’s report.

The DAPT score is a clever and innovative idea. It is a major step forward in helping clinicians decide which patients should continue dual antiplatelet therapy after safely completing a year on this therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention. The DAPT score was data driven and provides a tool to help personalize decision making with a simple, practical solution to a common clinical dilemma. It’s a welcome addition to our decision-making process.

The competing risks from bleeding events caused by continued dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) beyond 1 year and ischemic events caused by stopping DAPT creates difficulty in determining whether or not to continue or stop DAPT for an individual patient. The DAPT score helps make that decision.

|

| Mitchel L. Zoler/Frontline Medical News Dr. James de Lemos |

The analysis performed by Dr. Yeh and his associates produced a clear and convincing result. The primary caveat is that it is only applicable to patients who entered the randomized phase of the DAPT study, specifically patients who underwent a full first year of DAPT treatment following PCI without an ischemic or major bleeding event. I would like to see replication of the score’s validation in an additional data set, although few data sets exist that are suitable for such replication. Although the discrimination produced by the DAPT score is moderate, it compares favorably with other widely used clinical decision scores such as the CHA2ADS2-VASc.

The added decision-making ability facilitated by this score revises my interpretation of the results from the DAPT study. When the results of the trial appeared in 2014, I considered the outcome null because of the problem it highlighted in balancing the competing risks of ischemic and bleeding events when deciding about continuing DAPT beyond 1 year. The DAPT score helps produce a much clearer risk versus benefit decision for a sizable subset of patients who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention.

Dr. James de Lemos is a professor of medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and chief of the cardiology service at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas. He has received honoraria from Novo Nordisk and St. Jude and research funding from Roche Diagnostics and Abbott Diagnostics. He made these comments as the designated discussant for Dr. Yeh’s report.

The DAPT score is a clever and innovative idea. It is a major step forward in helping clinicians decide which patients should continue dual antiplatelet therapy after safely completing a year on this therapy following percutaneous coronary intervention. The DAPT score was data driven and provides a tool to help personalize decision making with a simple, practical solution to a common clinical dilemma. It’s a welcome addition to our decision-making process.

The competing risks from bleeding events caused by continued dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) beyond 1 year and ischemic events caused by stopping DAPT creates difficulty in determining whether or not to continue or stop DAPT for an individual patient. The DAPT score helps make that decision.

|

| Mitchel L. Zoler/Frontline Medical News Dr. James de Lemos |

The analysis performed by Dr. Yeh and his associates produced a clear and convincing result. The primary caveat is that it is only applicable to patients who entered the randomized phase of the DAPT study, specifically patients who underwent a full first year of DAPT treatment following PCI without an ischemic or major bleeding event. I would like to see replication of the score’s validation in an additional data set, although few data sets exist that are suitable for such replication. Although the discrimination produced by the DAPT score is moderate, it compares favorably with other widely used clinical decision scores such as the CHA2ADS2-VASc.

The added decision-making ability facilitated by this score revises my interpretation of the results from the DAPT study. When the results of the trial appeared in 2014, I considered the outcome null because of the problem it highlighted in balancing the competing risks of ischemic and bleeding events when deciding about continuing DAPT beyond 1 year. The DAPT score helps produce a much clearer risk versus benefit decision for a sizable subset of patients who undergo percutaneous coronary intervention.

Dr. James de Lemos is a professor of medicine at UT Southwestern Medical Center, Dallas, and chief of the cardiology service at Parkland Memorial Hospital in Dallas. He has received honoraria from Novo Nordisk and St. Jude and research funding from Roche Diagnostics and Abbott Diagnostics. He made these comments as the designated discussant for Dr. Yeh’s report.

ORLANDO – The common challenge faced by clinicians in deciding whether or not to continue dual antiplatelet therapy beyond a year in a patient who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention has gotten easier.

Researchers have devised a simple, eight-element scoring system using information already available in a patient’s records to help determine whether an individual patient will be more likely to benefit from continuing or stopping dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT).

“The DAPT score may help clinicians decide who should and who should not be treated with extended DAPT,” Dr. Robert W. Yeh said at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

“This is a step forward for an issue we deal with daily, balancing an individual patient’s risk from ischemia and bleeding,” commented Dr. Alice Jacobs, professor of medicine at Boston University and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory and interventional cardiology at Boston Medical Center.

Dr. Yeh and his associates devised the DAPT score from the data collected in the DAPT study, which enrolled more than 25,000 patients and randomized about 10,000 to test whether patients fared better by stopping or continuing DAPT after completing their initial year of DAPT following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The DAPT study results showed that after 18 additional months, continuing DAPT cut the rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis by 1 percentage point and the combined rate of death, MI, or stroke by 1.6 percentage points, both statistically significant differences, compared with patients randomized to treatment with aspirin plus placebo. The results also showed that continued DAPT increased GUSTO moderate or severe bleeding events by 1 percentage point, compared with the control patients (N Engl J Med. 2014 Dec 4;371[23]:2155-66).

The researchers used data collected in the DAPT study to build risk models using patient- and procedure-specific variables that predicted the ischemic and bleeding outcomes, and then combined the two into a single model. That meant abandoning some variables that had significant impact on both outcomes.

The result was a scoring system that includes eight variables that result in a score that ranges from –2 to 9. The analysis showed that a score of 1 or less identified patients for whom the risk for bleeding outweighs their potential gain by avoiding an ischemic event by about 2.5-fold, and hence likely would fare better by stopping DAPT. A score of 2 or higher flagged patients who benefited about eightfold more from avoided ischemic events, compared with their risk for a moderate or severe bleed.

Patient scores showed a classic bell-shaped curve, with roughly a quarter of the DAPT study patients having a score of 1 and about a quarter with a score of 2, about 16% had a score of 0 and about 16% had a score of 3, and about 8% had a score of –1 or –2, while about 9% had a score of 4 or more.

The investigators validated the scoring system using data collected in the PROTECT trial, which included 8,791 patients who underwent PCI during 2007-2008. Dr. Yeh acknowledged that the discrimination strength of the models he and his associated developed was “modest,” but added that its efficacy was greater than what has been shown in validation cohorts for the commonly used CH2ADS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scoring systems.

Dr. Yeh stressed that using the DAPT score “cannot trump clinical judgment.” He suggested that a clinician use the score to help facilitate a conversation with a PCI patient when the time comes to decide whether or not to continue DAPT beyond 1 year.

Other factors that could influence the decision include the length of the stented coronary lesions or prior radiation exposure to the patient’s coronary arteries, said Dr. Laura Mauri, who led the DAPT study and collaborated on developing the DAPT score. “It requires judgment to decide [on whether to continue DAPT] for patients who are on the borderline” for risk and benefit. “This gives patients a way to better understand what they might gain or lose” by continuing treatment. Without the quantification that the DAPT score provides, the balance of risk and benefit “is somewhat nebulous,” said Dr. Mauri, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Clinical Biometrics in the division of cardiovascular medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The investigators who ran the DAPT study realized several years before the study finished that development of the DAPT score was a critical part of applying the findings from the study into clinical practice, she said in an interview.

Dr. Yeh cautioned that the score is only appropriate for patients who match those enrolled into the DAPT study: patients who went through their first year post PCI on DAPT without having any ischemic or bleeding complications. For these patients, “we feel the DAPT score is incredibly valuable,” said Dr. Yeh, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. He and his associates are now using data from the DAPT study to model bleeding and ischemia risks during the first year following PCI to try to come up with risk models that can address DAPT use during this period.

Dr. Yeh and Dr. Mauri have placed a link to the electronic DAPT score calculator on the website for the DAPT study (www.daptstudy.org), and Dr. Yeh said that an app version will soon become available. Interventionalists in the programs that Dr. Yeh and Mauri are affiliated with have recently begun using the DAPT score calculator in their routine practice, Dr. Yeh said.

The DAPT study received funding from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Medtronic, Bristol-Myers Squib-Sanofi, Eli Lilly, and Daiichi Sankyo. Derivation of the DAPT score was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Yeh has received honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Merck. Dr. Jacobs had no disclosures. Dr. Mauri has been a consultant to Biotronik, Medtronic, and St. Jude and has received research funding from several companies.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

ORLANDO – The common challenge faced by clinicians in deciding whether or not to continue dual antiplatelet therapy beyond a year in a patient who underwent percutaneous coronary intervention has gotten easier.

Researchers have devised a simple, eight-element scoring system using information already available in a patient’s records to help determine whether an individual patient will be more likely to benefit from continuing or stopping dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT).

“The DAPT score may help clinicians decide who should and who should not be treated with extended DAPT,” Dr. Robert W. Yeh said at the American Heart Association Scientific Sessions.

“This is a step forward for an issue we deal with daily, balancing an individual patient’s risk from ischemia and bleeding,” commented Dr. Alice Jacobs, professor of medicine at Boston University and director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory and interventional cardiology at Boston Medical Center.

Dr. Yeh and his associates devised the DAPT score from the data collected in the DAPT study, which enrolled more than 25,000 patients and randomized about 10,000 to test whether patients fared better by stopping or continuing DAPT after completing their initial year of DAPT following percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). The DAPT study results showed that after 18 additional months, continuing DAPT cut the rate of definite or probable stent thrombosis by 1 percentage point and the combined rate of death, MI, or stroke by 1.6 percentage points, both statistically significant differences, compared with patients randomized to treatment with aspirin plus placebo. The results also showed that continued DAPT increased GUSTO moderate or severe bleeding events by 1 percentage point, compared with the control patients (N Engl J Med. 2014 Dec 4;371[23]:2155-66).

The researchers used data collected in the DAPT study to build risk models using patient- and procedure-specific variables that predicted the ischemic and bleeding outcomes, and then combined the two into a single model. That meant abandoning some variables that had significant impact on both outcomes.

The result was a scoring system that includes eight variables that result in a score that ranges from –2 to 9. The analysis showed that a score of 1 or less identified patients for whom the risk for bleeding outweighs their potential gain by avoiding an ischemic event by about 2.5-fold, and hence likely would fare better by stopping DAPT. A score of 2 or higher flagged patients who benefited about eightfold more from avoided ischemic events, compared with their risk for a moderate or severe bleed.

Patient scores showed a classic bell-shaped curve, with roughly a quarter of the DAPT study patients having a score of 1 and about a quarter with a score of 2, about 16% had a score of 0 and about 16% had a score of 3, and about 8% had a score of –1 or –2, while about 9% had a score of 4 or more.

The investigators validated the scoring system using data collected in the PROTECT trial, which included 8,791 patients who underwent PCI during 2007-2008. Dr. Yeh acknowledged that the discrimination strength of the models he and his associated developed was “modest,” but added that its efficacy was greater than what has been shown in validation cohorts for the commonly used CH2ADS2-VASc and HAS-BLED scoring systems.

Dr. Yeh stressed that using the DAPT score “cannot trump clinical judgment.” He suggested that a clinician use the score to help facilitate a conversation with a PCI patient when the time comes to decide whether or not to continue DAPT beyond 1 year.

Other factors that could influence the decision include the length of the stented coronary lesions or prior radiation exposure to the patient’s coronary arteries, said Dr. Laura Mauri, who led the DAPT study and collaborated on developing the DAPT score. “It requires judgment to decide [on whether to continue DAPT] for patients who are on the borderline” for risk and benefit. “This gives patients a way to better understand what they might gain or lose” by continuing treatment. Without the quantification that the DAPT score provides, the balance of risk and benefit “is somewhat nebulous,” said Dr. Mauri, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Clinical Biometrics in the division of cardiovascular medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston.

The investigators who ran the DAPT study realized several years before the study finished that development of the DAPT score was a critical part of applying the findings from the study into clinical practice, she said in an interview.

Dr. Yeh cautioned that the score is only appropriate for patients who match those enrolled into the DAPT study: patients who went through their first year post PCI on DAPT without having any ischemic or bleeding complications. For these patients, “we feel the DAPT score is incredibly valuable,” said Dr. Yeh, an interventional cardiologist and director of the Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston. He and his associates are now using data from the DAPT study to model bleeding and ischemia risks during the first year following PCI to try to come up with risk models that can address DAPT use during this period.

Dr. Yeh and Dr. Mauri have placed a link to the electronic DAPT score calculator on the website for the DAPT study (www.daptstudy.org), and Dr. Yeh said that an app version will soon become available. Interventionalists in the programs that Dr. Yeh and Mauri are affiliated with have recently begun using the DAPT score calculator in their routine practice, Dr. Yeh said.

The DAPT study received funding from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Medtronic, Bristol-Myers Squib-Sanofi, Eli Lilly, and Daiichi Sankyo. Derivation of the DAPT score was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Yeh has received honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Merck. Dr. Jacobs had no disclosures. Dr. Mauri has been a consultant to Biotronik, Medtronic, and St. Jude and has received research funding from several companies.

On Twitter @mitchelzoler

AT THE AHA SCIENTIFIC SESSIONS

Key clinical point: A year after percutaneous coronary intervention, the DAPT score helps clinicians decide whether to continue dual antiplatelet therapy.

Major finding: DAPT scores of 1 or less were linked with a 2.5-fold higher risk of bleeding than ischemic events prevented by continued DAPT; scores of 2 or more were linked with an eightfold increased rate of ischemic events prevented, compared with bleeding events triggered.

Data source: The DAPT study, a multicenter, international, randomized trial that enrolled 25,682 patients.

Disclosures: The DAPT study received funding from Abbott, Boston Scientific, Cordis, Medtronic, Bristol-Myers Squibb-Sanofi, Eli Lilly, and Daiichi Sankyo. Derivation of the DAPT score was funded by the National Institutes of Health. Dr. Yeh has received honoraria from Abbott, Boston Scientific, and Merck.