User login

Hospital readmissions for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure, and pneumonia have become central to quality-measurement efforts by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), which seek to improve hospital care transitions through public reporting and payment programs.1 Most current measures are limited to readmissions that require inpatient hospitalization and do not capture return visits to the emergency department (ED) that do not result in readmission but rather ED discharge. These visits may reflect important needs for acute, unscheduled care during the vulnerable posthospitalization period.2-5 While previous research has suggested that nearly 10% of patients may return to the ED following hospital discharge without readmission, the characteristics of these visits among Medicare beneficiaries and the implications for national care-coordination quality-measurement initiatives have not been explored.6,7

As the locus of acute outpatient care and the primary portal of hospital admissions and readmissions, ED visits following hospital discharge may convey meaningful information about posthospitalization care transitions.8,9 In addition, recent reviews and perspectives have highlighted the role of ED care-coordination services as interventions to reduce inpatient hospitalizations and improve care transitions,10,11 yet no empirical studies have evaluated the relationship between these unique care-coordination opportunities in the ED and care-coordination outcomes, such as hospital readmissions. As policymakers seek to develop accountability measures that capture the totality of acute, unscheduled visits following hospital discharge, describing the relationship between ED visits and readmissions will be essential to providers for benchmarking and to policymakers and payers seeking to reduce the total cost of care.12,13

Accordingly, we sought to characterize the frequency, diagnoses, and hospital-level variation in treat-and-discharge ED visitation following hospital discharge for 3 conditions for which hospital readmission is publicly reported by the CMS: AMI, heart failure, and pneumonia. We also sought to evaluate the relationship between hospital-level ED visitation following hospital discharge and publicly reported, risk-standardized readmission rates (RSRRs).

METHODS

Study Design

This study was a cross-sectional analysis of Medicare beneficiaries discharged alive following hospitalization for AMI, heart failure, and pneumonia between July 2011 and June 2012.

Selection of Participants

We used Medicare Standard Analytic Files to identify inpatient hospitalizations for each disease cohort based on principal discharge diagnoses. Each condition-specific cohort was constructed to be consistent with the CMS’s readmission measures using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision-Clinical Modification codes to identify AMI, heart failure, and pneumonia discharges.1 We included only patients who were enrolled in fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare parts A and B for 12 months prior to their index hospitalization to maximize the capture of diagnoses for risk adjustment. Each cohort included only patients who were discharged alive while maintaining FFS coverage for at least 30 days following hospital discharge to minimize bias in outcome ascertainment. We excluded patients who were discharged against medical advice. All contiguous admissions that were identified in a transfer chain were considered to be a single admission. Hospitals with fewer than 25 condition-specific index hospital admissions were excluded from this analysis for consistency with publicly reported measures.1

Measurements

Outcomes

We describe hospital-level, postdischarge ED visitation as the risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rate. The general construct of this measure is consistent with those of prior studies that define postdischarge ED visitation as the proportion of index admissions followed by a treat-and-discharge ED visit without hospital readmission2,3; however, this outcome also incorporates a risk-standardization model with covariates that are identical to the risk-standardization approach that is used for readmission measurement.

We describe hospital-level readmission by calculating RSRRs consistent with CMS readmission measures, which are endorsed by the National Quality Forum and used for public reporting.15-17 Detailed technical documentation, including the SAS code used to replicate hospital-level measures of readmission, are available publicly through the CMS QualityNet portal.18

We calculated risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates and RSRRs as the ratio of the predicted number of postdischarge ED visits or readmissions for a hospital given its observed case mix to the expected number of postdischarge ED visits or readmissions based on the nation’s performance with that hospital’s case mix, respectively. This approach estimates a distinct risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rate and RSRR for each hospital using hierarchical generalized linear models (HGLMs) and using a logit link with a first-level adjustment for age, sex, 29 clinical covariates for AMI, 35 clinical covariates for heart failure, and 38 clinical covariates for pneumonia. Each clinical covariate is identified based on inpatient and outpatient claims during the 12 months prior to the index hospitalization. The second level of the HGLM includes a random hospital-level intercept. This approach to measuring hospital readmissions accounts for the correlated nature of observed readmission rates within a hospital and reflects the assumption that after adjustment for patient characteristics and sampling variability, the remaining variation in postdischarge ED visit rates or readmission rates reflects hospital quality.

Analysis

In order to characterize treat-and-discharge postdischarge ED visits, we first described the clinical conditions that were evaluated during the first postdischarge ED visit. Based on the principal discharge diagnosis, ED visits were grouped into clinically meaningful categories using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Classifications Software (CCS).19 We also report hospital-level variation in risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates for AMI, heart failure, and pneumonia.

Next, we examined the relationship between hospital characteristics and risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates. We linked hospital characteristics from the American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey to the study dataset, including the following: safety-net status, teaching status, and urban or rural status. Consistent with prior work, hospital safety-net status was defined as a hospital Medicaid caseload greater than 1 standard deviation above the mean Medicaid caseload in the hospital’s state. Approximately 94% of the hospitals included in the 3 condition cohorts in the dataset had complete data in the 2011 AHA Annual Survey to be included in this analysis.

We evaluated the relationship between postdischarge ED visit rates and hospital readmission rates in 2 ways. First, we calculated Spearman rank correlation coefficients between hospital-level, risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates and RSRRs. Second, we calculated hospital-level variation in RSRRs based on the strata of risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates. Given the normal distribution of postdischarge ED visit rates, we grouped hospitals by quartile of postdischarge ED visit rates and 1 group for hospitals with no postdischarge ED visits.

Based on preliminary analyses indicating a relationship between hospital size, measured by condition-specific index hospitalization volume, and postdischarge treat-and-discharge ED visit rates, all descriptive statistics and correlations reported are weighted by the volume of condition-specific index hospitalizations. The study was approved by the Yale University Human Research Protection Program. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). The analytic plan and results reported in this work are in compliance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist.20

RESULTS

During the 1-year study period, we included a total of 157,035 patients who were hospitalized at 1656 hospitals for AMI, 391,209 at 3044 hospitals for heart failure, and 342,376 at 3484 hospitals for pneumonia. Details of study cohort creation are available in supplementary Table 1. After hospitalization for AMI, 14,714 patients experienced a postdischarge ED visit (8.4%) and 27,214 an inpatient readmissions (17.3%) within 30 days of discharge; 31,621 (7.6%) and 88,106 (22.5%) patients after hospitalization for heart failure and 26,681 (7.4%) and 59,352 (17.3%) patients after hospitalization for pneumonia experienced a postdischarge ED visit and an inpatient readmission within 30 days of discharge, respectively.

Postdischarge ED visits were for a wide variety of conditions, with the top 10 CCS categories comprising 44% of postdischarge ED visits following AMI hospitalizations, 44% of following heart failure hospitalizations, and 41% following pneumonia hospitalizations (supplementary Table 2). The first postdischarge ED visit was rarely for the same condition as the index hospitalization in the AMI cohort (224 visits; 1.5%) as well as the pneumonia cohort (1401 visits; 5.3%). Among patients who were originally admitted for heart failure, 10.6% of the first postdischarge ED visits were also for congestive heart failure.

We found wide hospital-level variation in postdischarge ED visit rates for each condition: AMI (median: 8.3%; 5th and 95th percentile: 2.8%-14.3%), heart failure (median: 7.3%; 5th and 95th percentile: 3.0%-13.3%), and pneumonia (median: 7.1%; 5th and 95th percentile: 2.4%-13.2%; supplementary Table 3). The variation persisted after accounting for hospital case mix, as evidenced in the supplementary Figure, which describes hospital variation in risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates. This variation was statistically significant (P < .001), as demonstrated by the isolated relationship between the random effect and the outcome (AMI: random effect estimate 0.0849 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.0832 to 0.0866]; heart failure: random effect estimate 0.0796 [95% CI, 0.0784 to 0.0809]; pneumonia: random effect estimate 0.0753 [95% CI, 0.0741 to 0.0764]).

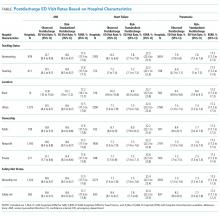

Across all 3 conditions, hospitals located in rural areas had significantly higher risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates than hospitals located in urban areas (10.1% vs 8.6% for AMI, 8.4% vs 7.5% for heart failure, and 8.0% vs 7.4% for pneumonia). In comparison to teaching hospitals, nonteaching hospitals had significantly higher risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates following hospital discharge for pneumonia (7.6% vs 7.1%). Safety-net hospitals also had higher risk-standardized postdischarge ED visitation rates following discharge for heart failure (8.4% vs 7.7%) and pneumonia (7.7% vs 7.3%). Risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates were higher in publicly owned hospitals than in nonprofit or privately owned hospitals for heart failure (8.0% vs 7.5% in nonprofit hospitals or 7.5% in private hospitals) and pneumonia (7.7% vs 7.4% in nonprofit hospitals and 7.3% in private hospitals; Table).

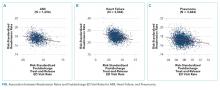

Among hospitals with RSRRs that were publicly reported by CMS, we found a moderate inverse correlation between risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates and hospital RSRRs for each condition: AMI (r = −0.23; 95% CI, −0.29 to −0.19), heart failure (r = −0.29; 95% CI, −0.34 to −0.27), and pneumonia (r = −0.18; 95% CI, −0.22 to −0.15; Figure).

DISCUSSION

Across a national cohort of Medicare beneficiaries, we found frequent treat-and-discharge ED utilization following hospital discharge for AMI, heart failure, and pneumonia, suggesting that publicly reported readmission measures are capturing only a portion of postdischarge acute-care use. Our findings confirm prior work describing a 30-day postdischarge ED visit rate of 8% to 9% among Medicare beneficiaries for all hospitalizations in several states.3,6

We also described substantial hospital-level variation in risk-standardized ED postdischarge rates. Prior work by Vashi et al.3 demonstrated substantial variation in observed postdischarge ED visit rates and inpatient readmissions following hospital discharge between clinical conditions in a population-level study. Our work extends upon this by demonstrating hospital-level variation for 3 conditions of high volume and substantial policy importance after accounting for differences in hospital case mix. Interestingly, our work also found similar rates of postdischarge ED treat-and-discharge visitation as recent work by Sabbatini et al.23 analyzing an all-payer, adult population with any clinical condition. Taken together, these studies show the substantial volume of postdischarge acute-care utilization in the ED not captured by existing readmission measures.

We found several hospital characteristics of importance in describing variation in postdischarge ED visitation rates. Notably, hospitals located in rural areas and safety-net hospitals demonstrated higher postdischarge ED visitation rates. This may reflect a higher use of the ED as an acute, unscheduled care access point in rural communities without access to alternative acute diagnostic and treatment services.24 Similarly, safety-net hospitals may be more likely to provide unscheduled care for patients with poor access to primary care in the ED setting. Yet, consistent with prior work, our results also indicate that these differences do not result in different readmission rates.25 Regarding hospital teaching status, unlike prior work suggesting that teaching hospitals care for more safety-net Medicare beneficiaries,26 our work found opposite patterns of postdischarge ED visitation between hospital teaching and safety-net status following pneumonia hospitalization. This may reflect differences in the organization of acute care as patients with limited access to unscheduled primary and specialty care in safety-net communities utilize the ED, whereas patients in teaching-hospital communities may be able to access hospital-based clinics for care.

Contrary to the expectations of many clinicians and policymakers, we found an inverse relationship between postdischarge ED visit rates and readmission rates. While the cross-sectional design of our study cannot provide a causal explanation, these findings merit policy attention and future exploration of several hypotheses. One possible explanation for this finding is that hospitals with high postdischarge ED visit rates provide care in communities in which acute, unscheduled care is consolidated to the ED setting and thereby permits the ED to serve a gatekeeper function for scarce inpatient resources. This hypothesis may also be supported by recent interventions demonstrating that the use of ED care coordination and geriatric ED services at higher-volume EDs can reduce hospitalizations. Also, hospitals with greater ED capacity may have easier ED access and may be able to see patients earlier in their disease courses post discharge or more frequently in the ED for follow-up, therefore increasing ED visits but avoiding rehospitalization. Another possible explanation is that hospitals with lower postdischarge ED visit rates may also have a lower propensity to admit patients. Because our definition of postdischarge ED visitation did not include ED visits that result in hospitalization, hospitals with a lower propensity to admit from the ED may therefore appear to have higher ED visit rates. This explanation may be further supported by our finding that many postdischarge ED visits are for conditions that are associated with discretionary hospitalization in the ED.27 A third explanation for this finding may be that poor access to outpatient care outside the hospital setting results in higher postdischarge ED visit rates without increasing the acuity of these revisits or increasing readmission rates28; however, given the validated, risk-standardized approach to readmission measurement, this is unlikely. This is also unlikely given recent work by Sabbatini et al.23 demonstrating substantial acuity among patients who return to the ED following hospital discharge. Future work should seek to evaluate the relationship between the availability of ED care-coordination services and the specific ED, hospital, and community care-coordination activities undertaken in the ED following hospital discharge to reduce readmission rates.

This work should be interpreted within the confines of its design. First, it is possible that some of the variation detected in postdischarge ED visit rates is mediated by hospital-level variation in postdischarge observation visits that are not captured in this outcome. However, in previous work, we have demonstrated that almost one-third of hospitals have no postdischarge observation stays and that most postdischarge observation stays are for more than 24 hours, which is unlikely to reflect the intensity of care of postdischarge ED visits.27 Second, our analyses were limited to Medicare FFS beneficiaries, which may limit the generalizability of this work to other patient populations. However, this dataset did include a national cohort of Medicare beneficiaries that is identical to those included in publicly reported CMS readmission measures; therefore, these results have substantial policy relevance. Third, this work was limited to 3 conditions of high illness severity of policy focus, and future work applying similar analyses to less severe conditions may find different degrees of hospital-level variation in postdischarge outcomes that are amenable to quality improvement. Finally, we assessed the rate of treat-and-discharge ED visits only after hospital discharge; this understates the frequency of ED visits since repeat ED visits and ED visits resulting in rehospitalization are not included. However, our definition was designed to mirror the definition used to assess hospital readmissions for policy purposes and is a conservative approach.

In summary, ED visits following hospital discharge are common, as Medicare beneficiaries have 1 treat-and-discharge ED visit for every 2 readmissions within 30 days of hospital discharge. Postdischarge ED visits occur for a wide variety of conditions, with wide risk-standardized, hospital-level variation. Hospitals with the highest risk-standardized postdischarge ED visitation rates demonstrated lower RSRRs, suggesting that policymakers and researchers should further examine the role of the hospital-based ED in providing access to acute care and supporting care transitions for the vulnerable Medicare population.

Disclosure

Dr. Venkatesh received contract support from the CMS, an agency of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, and grant support from the Emergency Medicine Foundation’s Health Policy Research Scholar Award during the conduct of the study; and Dr. Wang, Mr. Wang, Ms. Altaf, Dr. Bernheim, and Dr. Horwitz received contract support from the CMS, an agency of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, during the conduct of the study.

1. Dorsey KB GJ, Desai N, Lindenauer P, et al. 2015 Condition-Specific Measures Updates and Specifications Report Hospital-Level 30-Day Risk-Standardized Readmission Measures: AMI-Version 8.0, HF-Version 8.0, Pneumonia-Version 8.0, COPD-Version 4.0, and Stroke-Version 4.0. 2015. https://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/BlobServer?blobkey=id&blobnocache=true&blobwhere=1228890435217&blobheader=multipart%2Foctet-stream&blobheadername1=Content-Disposition&blobheadervalue1=attachment%3Bfilename%3DRdmn_AMIHFPNCOPDSTK_Msr_UpdtRpt.pdf&blobcol=urldata&blobtable=MungoBlobs. Accessed on July 8, 2015.

2. Rising KL, White LF, Fernandez WG, Boutwell AE. Emergency department visits after hospital discharge: a missing part of the equation. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(2):145-150. PubMed

3. Vashi AA, Fox JP, Carr BG, et al. Use of hospital-based acute care among patients recently discharged from the hospital. JAMA. 2013;309(4):364-371. PubMed

4. Kocher KE, Nallamothu BK, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Emergency department visits after surgery are common for Medicare patients, suggesting opportunities to improve care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(9):1600-1607. PubMed

5. Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome–an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):100-102. PubMed

6. Baier RR, Gardner RL, Coleman EA, Jencks SF, Mor V, Gravenstein S. Shifting the dialogue from hospital readmissions to unplanned care. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(6):450-453. PubMed

7. Schuur JD, Venkatesh AK. The growing role of emergency departments in hospital admissions. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):391-393. PubMed

8. Kocher KE, Dimick JB, Nallamothu BK. Changes in the source of unscheduled hospitalizations in the United States. Med Care. 2013;51(8):689-698. PubMed

9. Morganti KG, Bauhoff S, Blanchard JC, Abir M, Iyer N. The evolving role of emergency departments in the United States. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation; 2013. PubMed

10. Katz EB, Carrier ER, Umscheid CA, Pines JM. Comparative effectiveness of care coordination interventions in the emergency department: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(1):12.e1-23.e1. PubMed

11. Jaquis WP, Kaplan JA, Carpenter C, et al. Transitions of Care Task Force Report. 2012. http://www.acep.org/workarea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=91206. Accessed on January 2, 2016.

12. Horwitz LI, Wang C, Altaf FK, et al. Excess Days in Acute Care after Hospitalization for Heart Failure (Version 1.0) Final Measure Methodology Report. 2015. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/Measure-Methodology.html. Accessed on January 2, 2016.

13. Horwitz LI, Wang C, Altaf FK, et al. Excess Days in Acute Care after Hospitalization for Acute Myocardial Infarction (Version 1.0) Final Measure Methodology Report. 2015. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/Measure-Methodology.html. Accessed on January 2, 2016.

14. Hennessy S, Leonard CE, Freeman CP, et al. Validation of diagnostic codes for outpatient-originating sudden cardiac death and ventricular arrhythmia in Medicaid and Medicare claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(6):555-562. PubMed

15. Krumholz H, Normand S, Keenan P, et al. Hospital 30-Day Acute Myocardial Infarction Readmission Measure Methodology. 2008. http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/BlobServer?blobkey=id&blobnocache=true&blobwhere=1228873653724&blobheader=multipart%2Foctet-stream&blobheadername1=Content-Disposition&blobheadervalue1=attachment%3Bfilename%3DAMI_ReadmMeasMethod.pdf&blobcol=urldata&blobtable=MungoBlobs. Accessed on February 22, 2016.

16. Krumholz H, Normand S, Keenan P, et al. Hospital 30-Day Heart Failure Readmission Measure Methodology. 2008. http://69.28.93.62/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/2007-Baseline-info-on-Readmissions-krumholz.pdf. Accessed on February 22, 2016.

17. Krumholz H, Normand S, Keenan P, et al. Hospital 30-Day Pneumonia Readmission Measure Methodology. 2008. http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/BlobServer?blobkey=id&blobnocache=true&blobwhere=1228873654295&blobheader=multipart%2Foctet-stream&blobheadername1=Content-Disposition&blobheadervalue1=attachment%3Bfilename%3DPneumo_ReadmMeasMethod.pdf&blobcol=urldata&blobtable=MungoBlobs. Accessed on February 22, 2016.

18. QualityNet. Claims-based measures: readmission measures. 2016. http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?cid=1219069855273&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier3. Accessed on December 14, 2017.

19. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Clinical classifications software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project 2013; https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed December 14, 2017.

20. Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Prev Med. 2007;45(4):247-251. PubMed

21. Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309(4):355-363. PubMed

22. Venkatesh AK, Wang C, Ross JS, et al. Hospital Use of Observation Stays: Cross-Sectional Study of the Impact on Readmission Rates. Med Care. 2016;54(12):1070-1077. PubMed

23. Sabbatini AK, Kocher KE, Basu A, Hsia RY. In-hospital outcomes and costs among patients hospitalized during a return visit to the emergency department. JAMA. 2016;315(7):663-671. PubMed

24. Pitts SR, Carrier ER, Rich EC, Kellermann AL. Where Americans get acute care: increasingly, it’s not at their doctor’s office. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(9):1620-1629. PubMed

25. Ross JS, Bernheim SM, Lin Z, et al. Based on key measures, care quality for Medicare enrollees at safety-net and non-safety-net hospitals was almost equal. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(8):1739-1748. PubMed

26. Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. JAMA. 2011;305(7):675-681. PubMed

27. Venkatesh A, Wang C, Suter LG, et al. Hospital Use of Observation Stays: Cross-Sectional Study of the Impact on Readmission Rates. In: Academy Health Annual Research Meeting. San Diego, CA; 2014. PubMed

28. Pittsenbarger ZE, Thurm CW, Neuman MI, et al. Hospital-level factors associated with pediatric emergency department return visits. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(7):536-543. PubMed

Hospital readmissions for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure, and pneumonia have become central to quality-measurement efforts by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), which seek to improve hospital care transitions through public reporting and payment programs.1 Most current measures are limited to readmissions that require inpatient hospitalization and do not capture return visits to the emergency department (ED) that do not result in readmission but rather ED discharge. These visits may reflect important needs for acute, unscheduled care during the vulnerable posthospitalization period.2-5 While previous research has suggested that nearly 10% of patients may return to the ED following hospital discharge without readmission, the characteristics of these visits among Medicare beneficiaries and the implications for national care-coordination quality-measurement initiatives have not been explored.6,7

As the locus of acute outpatient care and the primary portal of hospital admissions and readmissions, ED visits following hospital discharge may convey meaningful information about posthospitalization care transitions.8,9 In addition, recent reviews and perspectives have highlighted the role of ED care-coordination services as interventions to reduce inpatient hospitalizations and improve care transitions,10,11 yet no empirical studies have evaluated the relationship between these unique care-coordination opportunities in the ED and care-coordination outcomes, such as hospital readmissions. As policymakers seek to develop accountability measures that capture the totality of acute, unscheduled visits following hospital discharge, describing the relationship between ED visits and readmissions will be essential to providers for benchmarking and to policymakers and payers seeking to reduce the total cost of care.12,13

Accordingly, we sought to characterize the frequency, diagnoses, and hospital-level variation in treat-and-discharge ED visitation following hospital discharge for 3 conditions for which hospital readmission is publicly reported by the CMS: AMI, heart failure, and pneumonia. We also sought to evaluate the relationship between hospital-level ED visitation following hospital discharge and publicly reported, risk-standardized readmission rates (RSRRs).

METHODS

Study Design

This study was a cross-sectional analysis of Medicare beneficiaries discharged alive following hospitalization for AMI, heart failure, and pneumonia between July 2011 and June 2012.

Selection of Participants

We used Medicare Standard Analytic Files to identify inpatient hospitalizations for each disease cohort based on principal discharge diagnoses. Each condition-specific cohort was constructed to be consistent with the CMS’s readmission measures using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision-Clinical Modification codes to identify AMI, heart failure, and pneumonia discharges.1 We included only patients who were enrolled in fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare parts A and B for 12 months prior to their index hospitalization to maximize the capture of diagnoses for risk adjustment. Each cohort included only patients who were discharged alive while maintaining FFS coverage for at least 30 days following hospital discharge to minimize bias in outcome ascertainment. We excluded patients who were discharged against medical advice. All contiguous admissions that were identified in a transfer chain were considered to be a single admission. Hospitals with fewer than 25 condition-specific index hospital admissions were excluded from this analysis for consistency with publicly reported measures.1

Measurements

Outcomes

We describe hospital-level, postdischarge ED visitation as the risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rate. The general construct of this measure is consistent with those of prior studies that define postdischarge ED visitation as the proportion of index admissions followed by a treat-and-discharge ED visit without hospital readmission2,3; however, this outcome also incorporates a risk-standardization model with covariates that are identical to the risk-standardization approach that is used for readmission measurement.

We describe hospital-level readmission by calculating RSRRs consistent with CMS readmission measures, which are endorsed by the National Quality Forum and used for public reporting.15-17 Detailed technical documentation, including the SAS code used to replicate hospital-level measures of readmission, are available publicly through the CMS QualityNet portal.18

We calculated risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates and RSRRs as the ratio of the predicted number of postdischarge ED visits or readmissions for a hospital given its observed case mix to the expected number of postdischarge ED visits or readmissions based on the nation’s performance with that hospital’s case mix, respectively. This approach estimates a distinct risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rate and RSRR for each hospital using hierarchical generalized linear models (HGLMs) and using a logit link with a first-level adjustment for age, sex, 29 clinical covariates for AMI, 35 clinical covariates for heart failure, and 38 clinical covariates for pneumonia. Each clinical covariate is identified based on inpatient and outpatient claims during the 12 months prior to the index hospitalization. The second level of the HGLM includes a random hospital-level intercept. This approach to measuring hospital readmissions accounts for the correlated nature of observed readmission rates within a hospital and reflects the assumption that after adjustment for patient characteristics and sampling variability, the remaining variation in postdischarge ED visit rates or readmission rates reflects hospital quality.

Analysis

In order to characterize treat-and-discharge postdischarge ED visits, we first described the clinical conditions that were evaluated during the first postdischarge ED visit. Based on the principal discharge diagnosis, ED visits were grouped into clinically meaningful categories using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Classifications Software (CCS).19 We also report hospital-level variation in risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates for AMI, heart failure, and pneumonia.

Next, we examined the relationship between hospital characteristics and risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates. We linked hospital characteristics from the American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey to the study dataset, including the following: safety-net status, teaching status, and urban or rural status. Consistent with prior work, hospital safety-net status was defined as a hospital Medicaid caseload greater than 1 standard deviation above the mean Medicaid caseload in the hospital’s state. Approximately 94% of the hospitals included in the 3 condition cohorts in the dataset had complete data in the 2011 AHA Annual Survey to be included in this analysis.

We evaluated the relationship between postdischarge ED visit rates and hospital readmission rates in 2 ways. First, we calculated Spearman rank correlation coefficients between hospital-level, risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates and RSRRs. Second, we calculated hospital-level variation in RSRRs based on the strata of risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates. Given the normal distribution of postdischarge ED visit rates, we grouped hospitals by quartile of postdischarge ED visit rates and 1 group for hospitals with no postdischarge ED visits.

Based on preliminary analyses indicating a relationship between hospital size, measured by condition-specific index hospitalization volume, and postdischarge treat-and-discharge ED visit rates, all descriptive statistics and correlations reported are weighted by the volume of condition-specific index hospitalizations. The study was approved by the Yale University Human Research Protection Program. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). The analytic plan and results reported in this work are in compliance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist.20

RESULTS

During the 1-year study period, we included a total of 157,035 patients who were hospitalized at 1656 hospitals for AMI, 391,209 at 3044 hospitals for heart failure, and 342,376 at 3484 hospitals for pneumonia. Details of study cohort creation are available in supplementary Table 1. After hospitalization for AMI, 14,714 patients experienced a postdischarge ED visit (8.4%) and 27,214 an inpatient readmissions (17.3%) within 30 days of discharge; 31,621 (7.6%) and 88,106 (22.5%) patients after hospitalization for heart failure and 26,681 (7.4%) and 59,352 (17.3%) patients after hospitalization for pneumonia experienced a postdischarge ED visit and an inpatient readmission within 30 days of discharge, respectively.

Postdischarge ED visits were for a wide variety of conditions, with the top 10 CCS categories comprising 44% of postdischarge ED visits following AMI hospitalizations, 44% of following heart failure hospitalizations, and 41% following pneumonia hospitalizations (supplementary Table 2). The first postdischarge ED visit was rarely for the same condition as the index hospitalization in the AMI cohort (224 visits; 1.5%) as well as the pneumonia cohort (1401 visits; 5.3%). Among patients who were originally admitted for heart failure, 10.6% of the first postdischarge ED visits were also for congestive heart failure.

We found wide hospital-level variation in postdischarge ED visit rates for each condition: AMI (median: 8.3%; 5th and 95th percentile: 2.8%-14.3%), heart failure (median: 7.3%; 5th and 95th percentile: 3.0%-13.3%), and pneumonia (median: 7.1%; 5th and 95th percentile: 2.4%-13.2%; supplementary Table 3). The variation persisted after accounting for hospital case mix, as evidenced in the supplementary Figure, which describes hospital variation in risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates. This variation was statistically significant (P < .001), as demonstrated by the isolated relationship between the random effect and the outcome (AMI: random effect estimate 0.0849 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.0832 to 0.0866]; heart failure: random effect estimate 0.0796 [95% CI, 0.0784 to 0.0809]; pneumonia: random effect estimate 0.0753 [95% CI, 0.0741 to 0.0764]).

Across all 3 conditions, hospitals located in rural areas had significantly higher risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates than hospitals located in urban areas (10.1% vs 8.6% for AMI, 8.4% vs 7.5% for heart failure, and 8.0% vs 7.4% for pneumonia). In comparison to teaching hospitals, nonteaching hospitals had significantly higher risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates following hospital discharge for pneumonia (7.6% vs 7.1%). Safety-net hospitals also had higher risk-standardized postdischarge ED visitation rates following discharge for heart failure (8.4% vs 7.7%) and pneumonia (7.7% vs 7.3%). Risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates were higher in publicly owned hospitals than in nonprofit or privately owned hospitals for heart failure (8.0% vs 7.5% in nonprofit hospitals or 7.5% in private hospitals) and pneumonia (7.7% vs 7.4% in nonprofit hospitals and 7.3% in private hospitals; Table).

Among hospitals with RSRRs that were publicly reported by CMS, we found a moderate inverse correlation between risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates and hospital RSRRs for each condition: AMI (r = −0.23; 95% CI, −0.29 to −0.19), heart failure (r = −0.29; 95% CI, −0.34 to −0.27), and pneumonia (r = −0.18; 95% CI, −0.22 to −0.15; Figure).

DISCUSSION

Across a national cohort of Medicare beneficiaries, we found frequent treat-and-discharge ED utilization following hospital discharge for AMI, heart failure, and pneumonia, suggesting that publicly reported readmission measures are capturing only a portion of postdischarge acute-care use. Our findings confirm prior work describing a 30-day postdischarge ED visit rate of 8% to 9% among Medicare beneficiaries for all hospitalizations in several states.3,6

We also described substantial hospital-level variation in risk-standardized ED postdischarge rates. Prior work by Vashi et al.3 demonstrated substantial variation in observed postdischarge ED visit rates and inpatient readmissions following hospital discharge between clinical conditions in a population-level study. Our work extends upon this by demonstrating hospital-level variation for 3 conditions of high volume and substantial policy importance after accounting for differences in hospital case mix. Interestingly, our work also found similar rates of postdischarge ED treat-and-discharge visitation as recent work by Sabbatini et al.23 analyzing an all-payer, adult population with any clinical condition. Taken together, these studies show the substantial volume of postdischarge acute-care utilization in the ED not captured by existing readmission measures.

We found several hospital characteristics of importance in describing variation in postdischarge ED visitation rates. Notably, hospitals located in rural areas and safety-net hospitals demonstrated higher postdischarge ED visitation rates. This may reflect a higher use of the ED as an acute, unscheduled care access point in rural communities without access to alternative acute diagnostic and treatment services.24 Similarly, safety-net hospitals may be more likely to provide unscheduled care for patients with poor access to primary care in the ED setting. Yet, consistent with prior work, our results also indicate that these differences do not result in different readmission rates.25 Regarding hospital teaching status, unlike prior work suggesting that teaching hospitals care for more safety-net Medicare beneficiaries,26 our work found opposite patterns of postdischarge ED visitation between hospital teaching and safety-net status following pneumonia hospitalization. This may reflect differences in the organization of acute care as patients with limited access to unscheduled primary and specialty care in safety-net communities utilize the ED, whereas patients in teaching-hospital communities may be able to access hospital-based clinics for care.

Contrary to the expectations of many clinicians and policymakers, we found an inverse relationship between postdischarge ED visit rates and readmission rates. While the cross-sectional design of our study cannot provide a causal explanation, these findings merit policy attention and future exploration of several hypotheses. One possible explanation for this finding is that hospitals with high postdischarge ED visit rates provide care in communities in which acute, unscheduled care is consolidated to the ED setting and thereby permits the ED to serve a gatekeeper function for scarce inpatient resources. This hypothesis may also be supported by recent interventions demonstrating that the use of ED care coordination and geriatric ED services at higher-volume EDs can reduce hospitalizations. Also, hospitals with greater ED capacity may have easier ED access and may be able to see patients earlier in their disease courses post discharge or more frequently in the ED for follow-up, therefore increasing ED visits but avoiding rehospitalization. Another possible explanation is that hospitals with lower postdischarge ED visit rates may also have a lower propensity to admit patients. Because our definition of postdischarge ED visitation did not include ED visits that result in hospitalization, hospitals with a lower propensity to admit from the ED may therefore appear to have higher ED visit rates. This explanation may be further supported by our finding that many postdischarge ED visits are for conditions that are associated with discretionary hospitalization in the ED.27 A third explanation for this finding may be that poor access to outpatient care outside the hospital setting results in higher postdischarge ED visit rates without increasing the acuity of these revisits or increasing readmission rates28; however, given the validated, risk-standardized approach to readmission measurement, this is unlikely. This is also unlikely given recent work by Sabbatini et al.23 demonstrating substantial acuity among patients who return to the ED following hospital discharge. Future work should seek to evaluate the relationship between the availability of ED care-coordination services and the specific ED, hospital, and community care-coordination activities undertaken in the ED following hospital discharge to reduce readmission rates.

This work should be interpreted within the confines of its design. First, it is possible that some of the variation detected in postdischarge ED visit rates is mediated by hospital-level variation in postdischarge observation visits that are not captured in this outcome. However, in previous work, we have demonstrated that almost one-third of hospitals have no postdischarge observation stays and that most postdischarge observation stays are for more than 24 hours, which is unlikely to reflect the intensity of care of postdischarge ED visits.27 Second, our analyses were limited to Medicare FFS beneficiaries, which may limit the generalizability of this work to other patient populations. However, this dataset did include a national cohort of Medicare beneficiaries that is identical to those included in publicly reported CMS readmission measures; therefore, these results have substantial policy relevance. Third, this work was limited to 3 conditions of high illness severity of policy focus, and future work applying similar analyses to less severe conditions may find different degrees of hospital-level variation in postdischarge outcomes that are amenable to quality improvement. Finally, we assessed the rate of treat-and-discharge ED visits only after hospital discharge; this understates the frequency of ED visits since repeat ED visits and ED visits resulting in rehospitalization are not included. However, our definition was designed to mirror the definition used to assess hospital readmissions for policy purposes and is a conservative approach.

In summary, ED visits following hospital discharge are common, as Medicare beneficiaries have 1 treat-and-discharge ED visit for every 2 readmissions within 30 days of hospital discharge. Postdischarge ED visits occur for a wide variety of conditions, with wide risk-standardized, hospital-level variation. Hospitals with the highest risk-standardized postdischarge ED visitation rates demonstrated lower RSRRs, suggesting that policymakers and researchers should further examine the role of the hospital-based ED in providing access to acute care and supporting care transitions for the vulnerable Medicare population.

Disclosure

Dr. Venkatesh received contract support from the CMS, an agency of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, and grant support from the Emergency Medicine Foundation’s Health Policy Research Scholar Award during the conduct of the study; and Dr. Wang, Mr. Wang, Ms. Altaf, Dr. Bernheim, and Dr. Horwitz received contract support from the CMS, an agency of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, during the conduct of the study.

Hospital readmissions for acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure, and pneumonia have become central to quality-measurement efforts by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), which seek to improve hospital care transitions through public reporting and payment programs.1 Most current measures are limited to readmissions that require inpatient hospitalization and do not capture return visits to the emergency department (ED) that do not result in readmission but rather ED discharge. These visits may reflect important needs for acute, unscheduled care during the vulnerable posthospitalization period.2-5 While previous research has suggested that nearly 10% of patients may return to the ED following hospital discharge without readmission, the characteristics of these visits among Medicare beneficiaries and the implications for national care-coordination quality-measurement initiatives have not been explored.6,7

As the locus of acute outpatient care and the primary portal of hospital admissions and readmissions, ED visits following hospital discharge may convey meaningful information about posthospitalization care transitions.8,9 In addition, recent reviews and perspectives have highlighted the role of ED care-coordination services as interventions to reduce inpatient hospitalizations and improve care transitions,10,11 yet no empirical studies have evaluated the relationship between these unique care-coordination opportunities in the ED and care-coordination outcomes, such as hospital readmissions. As policymakers seek to develop accountability measures that capture the totality of acute, unscheduled visits following hospital discharge, describing the relationship between ED visits and readmissions will be essential to providers for benchmarking and to policymakers and payers seeking to reduce the total cost of care.12,13

Accordingly, we sought to characterize the frequency, diagnoses, and hospital-level variation in treat-and-discharge ED visitation following hospital discharge for 3 conditions for which hospital readmission is publicly reported by the CMS: AMI, heart failure, and pneumonia. We also sought to evaluate the relationship between hospital-level ED visitation following hospital discharge and publicly reported, risk-standardized readmission rates (RSRRs).

METHODS

Study Design

This study was a cross-sectional analysis of Medicare beneficiaries discharged alive following hospitalization for AMI, heart failure, and pneumonia between July 2011 and June 2012.

Selection of Participants

We used Medicare Standard Analytic Files to identify inpatient hospitalizations for each disease cohort based on principal discharge diagnoses. Each condition-specific cohort was constructed to be consistent with the CMS’s readmission measures using International Classification of Diseases, 9th Revision-Clinical Modification codes to identify AMI, heart failure, and pneumonia discharges.1 We included only patients who were enrolled in fee-for-service (FFS) Medicare parts A and B for 12 months prior to their index hospitalization to maximize the capture of diagnoses for risk adjustment. Each cohort included only patients who were discharged alive while maintaining FFS coverage for at least 30 days following hospital discharge to minimize bias in outcome ascertainment. We excluded patients who were discharged against medical advice. All contiguous admissions that were identified in a transfer chain were considered to be a single admission. Hospitals with fewer than 25 condition-specific index hospital admissions were excluded from this analysis for consistency with publicly reported measures.1

Measurements

Outcomes

We describe hospital-level, postdischarge ED visitation as the risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rate. The general construct of this measure is consistent with those of prior studies that define postdischarge ED visitation as the proportion of index admissions followed by a treat-and-discharge ED visit without hospital readmission2,3; however, this outcome also incorporates a risk-standardization model with covariates that are identical to the risk-standardization approach that is used for readmission measurement.

We describe hospital-level readmission by calculating RSRRs consistent with CMS readmission measures, which are endorsed by the National Quality Forum and used for public reporting.15-17 Detailed technical documentation, including the SAS code used to replicate hospital-level measures of readmission, are available publicly through the CMS QualityNet portal.18

We calculated risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates and RSRRs as the ratio of the predicted number of postdischarge ED visits or readmissions for a hospital given its observed case mix to the expected number of postdischarge ED visits or readmissions based on the nation’s performance with that hospital’s case mix, respectively. This approach estimates a distinct risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rate and RSRR for each hospital using hierarchical generalized linear models (HGLMs) and using a logit link with a first-level adjustment for age, sex, 29 clinical covariates for AMI, 35 clinical covariates for heart failure, and 38 clinical covariates for pneumonia. Each clinical covariate is identified based on inpatient and outpatient claims during the 12 months prior to the index hospitalization. The second level of the HGLM includes a random hospital-level intercept. This approach to measuring hospital readmissions accounts for the correlated nature of observed readmission rates within a hospital and reflects the assumption that after adjustment for patient characteristics and sampling variability, the remaining variation in postdischarge ED visit rates or readmission rates reflects hospital quality.

Analysis

In order to characterize treat-and-discharge postdischarge ED visits, we first described the clinical conditions that were evaluated during the first postdischarge ED visit. Based on the principal discharge diagnosis, ED visits were grouped into clinically meaningful categories using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Clinical Classifications Software (CCS).19 We also report hospital-level variation in risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates for AMI, heart failure, and pneumonia.

Next, we examined the relationship between hospital characteristics and risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates. We linked hospital characteristics from the American Hospital Association (AHA) Annual Survey to the study dataset, including the following: safety-net status, teaching status, and urban or rural status. Consistent with prior work, hospital safety-net status was defined as a hospital Medicaid caseload greater than 1 standard deviation above the mean Medicaid caseload in the hospital’s state. Approximately 94% of the hospitals included in the 3 condition cohorts in the dataset had complete data in the 2011 AHA Annual Survey to be included in this analysis.

We evaluated the relationship between postdischarge ED visit rates and hospital readmission rates in 2 ways. First, we calculated Spearman rank correlation coefficients between hospital-level, risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates and RSRRs. Second, we calculated hospital-level variation in RSRRs based on the strata of risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates. Given the normal distribution of postdischarge ED visit rates, we grouped hospitals by quartile of postdischarge ED visit rates and 1 group for hospitals with no postdischarge ED visits.

Based on preliminary analyses indicating a relationship between hospital size, measured by condition-specific index hospitalization volume, and postdischarge treat-and-discharge ED visit rates, all descriptive statistics and correlations reported are weighted by the volume of condition-specific index hospitalizations. The study was approved by the Yale University Human Research Protection Program. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC). The analytic plan and results reported in this work are in compliance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology checklist.20

RESULTS

During the 1-year study period, we included a total of 157,035 patients who were hospitalized at 1656 hospitals for AMI, 391,209 at 3044 hospitals for heart failure, and 342,376 at 3484 hospitals for pneumonia. Details of study cohort creation are available in supplementary Table 1. After hospitalization for AMI, 14,714 patients experienced a postdischarge ED visit (8.4%) and 27,214 an inpatient readmissions (17.3%) within 30 days of discharge; 31,621 (7.6%) and 88,106 (22.5%) patients after hospitalization for heart failure and 26,681 (7.4%) and 59,352 (17.3%) patients after hospitalization for pneumonia experienced a postdischarge ED visit and an inpatient readmission within 30 days of discharge, respectively.

Postdischarge ED visits were for a wide variety of conditions, with the top 10 CCS categories comprising 44% of postdischarge ED visits following AMI hospitalizations, 44% of following heart failure hospitalizations, and 41% following pneumonia hospitalizations (supplementary Table 2). The first postdischarge ED visit was rarely for the same condition as the index hospitalization in the AMI cohort (224 visits; 1.5%) as well as the pneumonia cohort (1401 visits; 5.3%). Among patients who were originally admitted for heart failure, 10.6% of the first postdischarge ED visits were also for congestive heart failure.

We found wide hospital-level variation in postdischarge ED visit rates for each condition: AMI (median: 8.3%; 5th and 95th percentile: 2.8%-14.3%), heart failure (median: 7.3%; 5th and 95th percentile: 3.0%-13.3%), and pneumonia (median: 7.1%; 5th and 95th percentile: 2.4%-13.2%; supplementary Table 3). The variation persisted after accounting for hospital case mix, as evidenced in the supplementary Figure, which describes hospital variation in risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates. This variation was statistically significant (P < .001), as demonstrated by the isolated relationship between the random effect and the outcome (AMI: random effect estimate 0.0849 [95% confidence interval (CI), 0.0832 to 0.0866]; heart failure: random effect estimate 0.0796 [95% CI, 0.0784 to 0.0809]; pneumonia: random effect estimate 0.0753 [95% CI, 0.0741 to 0.0764]).

Across all 3 conditions, hospitals located in rural areas had significantly higher risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates than hospitals located in urban areas (10.1% vs 8.6% for AMI, 8.4% vs 7.5% for heart failure, and 8.0% vs 7.4% for pneumonia). In comparison to teaching hospitals, nonteaching hospitals had significantly higher risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates following hospital discharge for pneumonia (7.6% vs 7.1%). Safety-net hospitals also had higher risk-standardized postdischarge ED visitation rates following discharge for heart failure (8.4% vs 7.7%) and pneumonia (7.7% vs 7.3%). Risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates were higher in publicly owned hospitals than in nonprofit or privately owned hospitals for heart failure (8.0% vs 7.5% in nonprofit hospitals or 7.5% in private hospitals) and pneumonia (7.7% vs 7.4% in nonprofit hospitals and 7.3% in private hospitals; Table).

Among hospitals with RSRRs that were publicly reported by CMS, we found a moderate inverse correlation between risk-standardized postdischarge ED visit rates and hospital RSRRs for each condition: AMI (r = −0.23; 95% CI, −0.29 to −0.19), heart failure (r = −0.29; 95% CI, −0.34 to −0.27), and pneumonia (r = −0.18; 95% CI, −0.22 to −0.15; Figure).

DISCUSSION

Across a national cohort of Medicare beneficiaries, we found frequent treat-and-discharge ED utilization following hospital discharge for AMI, heart failure, and pneumonia, suggesting that publicly reported readmission measures are capturing only a portion of postdischarge acute-care use. Our findings confirm prior work describing a 30-day postdischarge ED visit rate of 8% to 9% among Medicare beneficiaries for all hospitalizations in several states.3,6

We also described substantial hospital-level variation in risk-standardized ED postdischarge rates. Prior work by Vashi et al.3 demonstrated substantial variation in observed postdischarge ED visit rates and inpatient readmissions following hospital discharge between clinical conditions in a population-level study. Our work extends upon this by demonstrating hospital-level variation for 3 conditions of high volume and substantial policy importance after accounting for differences in hospital case mix. Interestingly, our work also found similar rates of postdischarge ED treat-and-discharge visitation as recent work by Sabbatini et al.23 analyzing an all-payer, adult population with any clinical condition. Taken together, these studies show the substantial volume of postdischarge acute-care utilization in the ED not captured by existing readmission measures.

We found several hospital characteristics of importance in describing variation in postdischarge ED visitation rates. Notably, hospitals located in rural areas and safety-net hospitals demonstrated higher postdischarge ED visitation rates. This may reflect a higher use of the ED as an acute, unscheduled care access point in rural communities without access to alternative acute diagnostic and treatment services.24 Similarly, safety-net hospitals may be more likely to provide unscheduled care for patients with poor access to primary care in the ED setting. Yet, consistent with prior work, our results also indicate that these differences do not result in different readmission rates.25 Regarding hospital teaching status, unlike prior work suggesting that teaching hospitals care for more safety-net Medicare beneficiaries,26 our work found opposite patterns of postdischarge ED visitation between hospital teaching and safety-net status following pneumonia hospitalization. This may reflect differences in the organization of acute care as patients with limited access to unscheduled primary and specialty care in safety-net communities utilize the ED, whereas patients in teaching-hospital communities may be able to access hospital-based clinics for care.

Contrary to the expectations of many clinicians and policymakers, we found an inverse relationship between postdischarge ED visit rates and readmission rates. While the cross-sectional design of our study cannot provide a causal explanation, these findings merit policy attention and future exploration of several hypotheses. One possible explanation for this finding is that hospitals with high postdischarge ED visit rates provide care in communities in which acute, unscheduled care is consolidated to the ED setting and thereby permits the ED to serve a gatekeeper function for scarce inpatient resources. This hypothesis may also be supported by recent interventions demonstrating that the use of ED care coordination and geriatric ED services at higher-volume EDs can reduce hospitalizations. Also, hospitals with greater ED capacity may have easier ED access and may be able to see patients earlier in their disease courses post discharge or more frequently in the ED for follow-up, therefore increasing ED visits but avoiding rehospitalization. Another possible explanation is that hospitals with lower postdischarge ED visit rates may also have a lower propensity to admit patients. Because our definition of postdischarge ED visitation did not include ED visits that result in hospitalization, hospitals with a lower propensity to admit from the ED may therefore appear to have higher ED visit rates. This explanation may be further supported by our finding that many postdischarge ED visits are for conditions that are associated with discretionary hospitalization in the ED.27 A third explanation for this finding may be that poor access to outpatient care outside the hospital setting results in higher postdischarge ED visit rates without increasing the acuity of these revisits or increasing readmission rates28; however, given the validated, risk-standardized approach to readmission measurement, this is unlikely. This is also unlikely given recent work by Sabbatini et al.23 demonstrating substantial acuity among patients who return to the ED following hospital discharge. Future work should seek to evaluate the relationship between the availability of ED care-coordination services and the specific ED, hospital, and community care-coordination activities undertaken in the ED following hospital discharge to reduce readmission rates.

This work should be interpreted within the confines of its design. First, it is possible that some of the variation detected in postdischarge ED visit rates is mediated by hospital-level variation in postdischarge observation visits that are not captured in this outcome. However, in previous work, we have demonstrated that almost one-third of hospitals have no postdischarge observation stays and that most postdischarge observation stays are for more than 24 hours, which is unlikely to reflect the intensity of care of postdischarge ED visits.27 Second, our analyses were limited to Medicare FFS beneficiaries, which may limit the generalizability of this work to other patient populations. However, this dataset did include a national cohort of Medicare beneficiaries that is identical to those included in publicly reported CMS readmission measures; therefore, these results have substantial policy relevance. Third, this work was limited to 3 conditions of high illness severity of policy focus, and future work applying similar analyses to less severe conditions may find different degrees of hospital-level variation in postdischarge outcomes that are amenable to quality improvement. Finally, we assessed the rate of treat-and-discharge ED visits only after hospital discharge; this understates the frequency of ED visits since repeat ED visits and ED visits resulting in rehospitalization are not included. However, our definition was designed to mirror the definition used to assess hospital readmissions for policy purposes and is a conservative approach.

In summary, ED visits following hospital discharge are common, as Medicare beneficiaries have 1 treat-and-discharge ED visit for every 2 readmissions within 30 days of hospital discharge. Postdischarge ED visits occur for a wide variety of conditions, with wide risk-standardized, hospital-level variation. Hospitals with the highest risk-standardized postdischarge ED visitation rates demonstrated lower RSRRs, suggesting that policymakers and researchers should further examine the role of the hospital-based ED in providing access to acute care and supporting care transitions for the vulnerable Medicare population.

Disclosure

Dr. Venkatesh received contract support from the CMS, an agency of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, and grant support from the Emergency Medicine Foundation’s Health Policy Research Scholar Award during the conduct of the study; and Dr. Wang, Mr. Wang, Ms. Altaf, Dr. Bernheim, and Dr. Horwitz received contract support from the CMS, an agency of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, during the conduct of the study.

1. Dorsey KB GJ, Desai N, Lindenauer P, et al. 2015 Condition-Specific Measures Updates and Specifications Report Hospital-Level 30-Day Risk-Standardized Readmission Measures: AMI-Version 8.0, HF-Version 8.0, Pneumonia-Version 8.0, COPD-Version 4.0, and Stroke-Version 4.0. 2015. https://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/BlobServer?blobkey=id&blobnocache=true&blobwhere=1228890435217&blobheader=multipart%2Foctet-stream&blobheadername1=Content-Disposition&blobheadervalue1=attachment%3Bfilename%3DRdmn_AMIHFPNCOPDSTK_Msr_UpdtRpt.pdf&blobcol=urldata&blobtable=MungoBlobs. Accessed on July 8, 2015.

2. Rising KL, White LF, Fernandez WG, Boutwell AE. Emergency department visits after hospital discharge: a missing part of the equation. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(2):145-150. PubMed

3. Vashi AA, Fox JP, Carr BG, et al. Use of hospital-based acute care among patients recently discharged from the hospital. JAMA. 2013;309(4):364-371. PubMed

4. Kocher KE, Nallamothu BK, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Emergency department visits after surgery are common for Medicare patients, suggesting opportunities to improve care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(9):1600-1607. PubMed

5. Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome–an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):100-102. PubMed

6. Baier RR, Gardner RL, Coleman EA, Jencks SF, Mor V, Gravenstein S. Shifting the dialogue from hospital readmissions to unplanned care. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(6):450-453. PubMed

7. Schuur JD, Venkatesh AK. The growing role of emergency departments in hospital admissions. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):391-393. PubMed

8. Kocher KE, Dimick JB, Nallamothu BK. Changes in the source of unscheduled hospitalizations in the United States. Med Care. 2013;51(8):689-698. PubMed

9. Morganti KG, Bauhoff S, Blanchard JC, Abir M, Iyer N. The evolving role of emergency departments in the United States. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation; 2013. PubMed

10. Katz EB, Carrier ER, Umscheid CA, Pines JM. Comparative effectiveness of care coordination interventions in the emergency department: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(1):12.e1-23.e1. PubMed

11. Jaquis WP, Kaplan JA, Carpenter C, et al. Transitions of Care Task Force Report. 2012. http://www.acep.org/workarea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=91206. Accessed on January 2, 2016.

12. Horwitz LI, Wang C, Altaf FK, et al. Excess Days in Acute Care after Hospitalization for Heart Failure (Version 1.0) Final Measure Methodology Report. 2015. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/Measure-Methodology.html. Accessed on January 2, 2016.

13. Horwitz LI, Wang C, Altaf FK, et al. Excess Days in Acute Care after Hospitalization for Acute Myocardial Infarction (Version 1.0) Final Measure Methodology Report. 2015. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/Measure-Methodology.html. Accessed on January 2, 2016.

14. Hennessy S, Leonard CE, Freeman CP, et al. Validation of diagnostic codes for outpatient-originating sudden cardiac death and ventricular arrhythmia in Medicaid and Medicare claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(6):555-562. PubMed

15. Krumholz H, Normand S, Keenan P, et al. Hospital 30-Day Acute Myocardial Infarction Readmission Measure Methodology. 2008. http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/BlobServer?blobkey=id&blobnocache=true&blobwhere=1228873653724&blobheader=multipart%2Foctet-stream&blobheadername1=Content-Disposition&blobheadervalue1=attachment%3Bfilename%3DAMI_ReadmMeasMethod.pdf&blobcol=urldata&blobtable=MungoBlobs. Accessed on February 22, 2016.

16. Krumholz H, Normand S, Keenan P, et al. Hospital 30-Day Heart Failure Readmission Measure Methodology. 2008. http://69.28.93.62/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/2007-Baseline-info-on-Readmissions-krumholz.pdf. Accessed on February 22, 2016.

17. Krumholz H, Normand S, Keenan P, et al. Hospital 30-Day Pneumonia Readmission Measure Methodology. 2008. http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/BlobServer?blobkey=id&blobnocache=true&blobwhere=1228873654295&blobheader=multipart%2Foctet-stream&blobheadername1=Content-Disposition&blobheadervalue1=attachment%3Bfilename%3DPneumo_ReadmMeasMethod.pdf&blobcol=urldata&blobtable=MungoBlobs. Accessed on February 22, 2016.

18. QualityNet. Claims-based measures: readmission measures. 2016. http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?cid=1219069855273&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier3. Accessed on December 14, 2017.

19. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Clinical classifications software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project 2013; https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed December 14, 2017.

20. Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Prev Med. 2007;45(4):247-251. PubMed

21. Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309(4):355-363. PubMed

22. Venkatesh AK, Wang C, Ross JS, et al. Hospital Use of Observation Stays: Cross-Sectional Study of the Impact on Readmission Rates. Med Care. 2016;54(12):1070-1077. PubMed

23. Sabbatini AK, Kocher KE, Basu A, Hsia RY. In-hospital outcomes and costs among patients hospitalized during a return visit to the emergency department. JAMA. 2016;315(7):663-671. PubMed

24. Pitts SR, Carrier ER, Rich EC, Kellermann AL. Where Americans get acute care: increasingly, it’s not at their doctor’s office. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(9):1620-1629. PubMed

25. Ross JS, Bernheim SM, Lin Z, et al. Based on key measures, care quality for Medicare enrollees at safety-net and non-safety-net hospitals was almost equal. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(8):1739-1748. PubMed

26. Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. JAMA. 2011;305(7):675-681. PubMed

27. Venkatesh A, Wang C, Suter LG, et al. Hospital Use of Observation Stays: Cross-Sectional Study of the Impact on Readmission Rates. In: Academy Health Annual Research Meeting. San Diego, CA; 2014. PubMed

28. Pittsenbarger ZE, Thurm CW, Neuman MI, et al. Hospital-level factors associated with pediatric emergency department return visits. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(7):536-543. PubMed

1. Dorsey KB GJ, Desai N, Lindenauer P, et al. 2015 Condition-Specific Measures Updates and Specifications Report Hospital-Level 30-Day Risk-Standardized Readmission Measures: AMI-Version 8.0, HF-Version 8.0, Pneumonia-Version 8.0, COPD-Version 4.0, and Stroke-Version 4.0. 2015. https://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/BlobServer?blobkey=id&blobnocache=true&blobwhere=1228890435217&blobheader=multipart%2Foctet-stream&blobheadername1=Content-Disposition&blobheadervalue1=attachment%3Bfilename%3DRdmn_AMIHFPNCOPDSTK_Msr_UpdtRpt.pdf&blobcol=urldata&blobtable=MungoBlobs. Accessed on July 8, 2015.

2. Rising KL, White LF, Fernandez WG, Boutwell AE. Emergency department visits after hospital discharge: a missing part of the equation. Ann Emerg Med. 2013;62(2):145-150. PubMed

3. Vashi AA, Fox JP, Carr BG, et al. Use of hospital-based acute care among patients recently discharged from the hospital. JAMA. 2013;309(4):364-371. PubMed

4. Kocher KE, Nallamothu BK, Birkmeyer JD, Dimick JB. Emergency department visits after surgery are common for Medicare patients, suggesting opportunities to improve care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2013;32(9):1600-1607. PubMed

5. Krumholz HM. Post-hospital syndrome–an acquired, transient condition of generalized risk. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(2):100-102. PubMed

6. Baier RR, Gardner RL, Coleman EA, Jencks SF, Mor V, Gravenstein S. Shifting the dialogue from hospital readmissions to unplanned care. Am J Manag Care. 2013;19(6):450-453. PubMed

7. Schuur JD, Venkatesh AK. The growing role of emergency departments in hospital admissions. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):391-393. PubMed

8. Kocher KE, Dimick JB, Nallamothu BK. Changes in the source of unscheduled hospitalizations in the United States. Med Care. 2013;51(8):689-698. PubMed

9. Morganti KG, Bauhoff S, Blanchard JC, Abir M, Iyer N. The evolving role of emergency departments in the United States. Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation; 2013. PubMed

10. Katz EB, Carrier ER, Umscheid CA, Pines JM. Comparative effectiveness of care coordination interventions in the emergency department: a systematic review. Ann Emerg Med. 2012;60(1):12.e1-23.e1. PubMed

11. Jaquis WP, Kaplan JA, Carpenter C, et al. Transitions of Care Task Force Report. 2012. http://www.acep.org/workarea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=91206. Accessed on January 2, 2016.

12. Horwitz LI, Wang C, Altaf FK, et al. Excess Days in Acute Care after Hospitalization for Heart Failure (Version 1.0) Final Measure Methodology Report. 2015. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/Measure-Methodology.html. Accessed on January 2, 2016.

13. Horwitz LI, Wang C, Altaf FK, et al. Excess Days in Acute Care after Hospitalization for Acute Myocardial Infarction (Version 1.0) Final Measure Methodology Report. 2015. https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Quality-Initiatives-Patient-Assessment-Instruments/HospitalQualityInits/Measure-Methodology.html. Accessed on January 2, 2016.

14. Hennessy S, Leonard CE, Freeman CP, et al. Validation of diagnostic codes for outpatient-originating sudden cardiac death and ventricular arrhythmia in Medicaid and Medicare claims data. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. 2010;19(6):555-562. PubMed

15. Krumholz H, Normand S, Keenan P, et al. Hospital 30-Day Acute Myocardial Infarction Readmission Measure Methodology. 2008. http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/BlobServer?blobkey=id&blobnocache=true&blobwhere=1228873653724&blobheader=multipart%2Foctet-stream&blobheadername1=Content-Disposition&blobheadervalue1=attachment%3Bfilename%3DAMI_ReadmMeasMethod.pdf&blobcol=urldata&blobtable=MungoBlobs. Accessed on February 22, 2016.

16. Krumholz H, Normand S, Keenan P, et al. Hospital 30-Day Heart Failure Readmission Measure Methodology. 2008. http://69.28.93.62/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/2007-Baseline-info-on-Readmissions-krumholz.pdf. Accessed on February 22, 2016.

17. Krumholz H, Normand S, Keenan P, et al. Hospital 30-Day Pneumonia Readmission Measure Methodology. 2008. http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/BlobServer?blobkey=id&blobnocache=true&blobwhere=1228873654295&blobheader=multipart%2Foctet-stream&blobheadername1=Content-Disposition&blobheadervalue1=attachment%3Bfilename%3DPneumo_ReadmMeasMethod.pdf&blobcol=urldata&blobtable=MungoBlobs. Accessed on February 22, 2016.

18. QualityNet. Claims-based measures: readmission measures. 2016. http://www.qualitynet.org/dcs/ContentServer?cid=1219069855273&pagename=QnetPublic%2FPage%2FQnetTier3. Accessed on December 14, 2017.

19. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. Clinical classifications software (CCS) for ICD-9-CM. Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project 2013; https://www.hcup-us.ahrq.gov/toolssoftware/ccs/ccs.jsp. Accessed December 14, 2017.

20. Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Prev Med. 2007;45(4):247-251. PubMed

21. Dharmarajan K, Hsieh AF, Lin Z, et al. Diagnoses and timing of 30-day readmissions after hospitalization for heart failure, acute myocardial infarction, or pneumonia. JAMA. 2013;309(4):355-363. PubMed

22. Venkatesh AK, Wang C, Ross JS, et al. Hospital Use of Observation Stays: Cross-Sectional Study of the Impact on Readmission Rates. Med Care. 2016;54(12):1070-1077. PubMed

23. Sabbatini AK, Kocher KE, Basu A, Hsia RY. In-hospital outcomes and costs among patients hospitalized during a return visit to the emergency department. JAMA. 2016;315(7):663-671. PubMed

24. Pitts SR, Carrier ER, Rich EC, Kellermann AL. Where Americans get acute care: increasingly, it’s not at their doctor’s office. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(9):1620-1629. PubMed

25. Ross JS, Bernheim SM, Lin Z, et al. Based on key measures, care quality for Medicare enrollees at safety-net and non-safety-net hospitals was almost equal. Health Aff (Millwood). 2012;31(8):1739-1748. PubMed

26. Joynt KE, Orav EJ, Jha AK. Thirty-day readmission rates for Medicare beneficiaries by race and site of care. JAMA. 2011;305(7):675-681. PubMed

27. Venkatesh A, Wang C, Suter LG, et al. Hospital Use of Observation Stays: Cross-Sectional Study of the Impact on Readmission Rates. In: Academy Health Annual Research Meeting. San Diego, CA; 2014. PubMed

28. Pittsenbarger ZE, Thurm CW, Neuman MI, et al. Hospital-level factors associated with pediatric emergency department return visits. J Hosp Med. 2017;12(7):536-543. PubMed

© 2018 Society of Hospital Medicine