User login

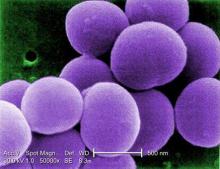

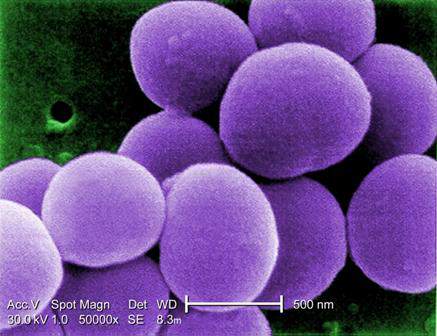

HOUSTON – New science suggests that the skin microbial environment may be manipulated in patients with atopic dermatitis in a way that could quell overgrowth of Staphylococcus aureus – meaning that the first microbiome-based therapies for AD might not be far away.

Dr. Richard L. Gallo, professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, described preliminary findings that the skin microbiome functions differently in patients with AD than in those without.

Dr. Gallo and his colleagues took skin sloughs from 50 AD patients and 30 non-AD controls. Most of the Staphylococcus aureus bacteria on sloughs from AD patients were alive, while most were dead on sloughs from patients without AD. Normal subjects had skin biomes that were able to kill S. aureus, Dr. Gallo said in a plenary talk at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The investigators looked at the few species of normally occurring skin bacteria that can kill S. aureus, focusing on Staphylococcus hominis, which, they found, produces an antimicrobial peptide very effective against S. aureus. After mouse experiments showed S. hominis effective against S. aureus infection, Dr. Gallo and his colleagues began investigating its activity in a human patient. They isolated S. hominis from the skin of a patient, cultured it, and applied it in a topical cream. The result was a 1,000-fold drop in S. aureus colonization in the same patient. Dr. Gallo did not say how long the effect lasted or whether clinical symptoms abated.

“The pharmaceutical industry has been looking for antimicrobials in the jungles and the deep sea,” Dr. Gallo said. “We just swabbed an arm and found one that was really effective.” The findings suggest, he said, that “perhaps there are some therapeutic opportunities using the skin microbiome that aren’t 5 years away.” He added that his team has funding from NIH to continue this work as well as for a larger study using a similar approach that will be applicable in larger populations.

Dr. Gallo also mentioned new research showing that the skin microbiome goes quite a bit deeper than commonly understood, with immune-mediating bacteria found in the dermis and even the adipose layers. “We have to start thinking about skin in a different way,” he said. “These are not absolute barriers but highly evolved filters that permit selected microbes to interact.” Dr. Gallo has received research support from Galderma and Bayer and is listed on several patents for potential therapies held by his institution.

HOUSTON – New science suggests that the skin microbial environment may be manipulated in patients with atopic dermatitis in a way that could quell overgrowth of Staphylococcus aureus – meaning that the first microbiome-based therapies for AD might not be far away.

Dr. Richard L. Gallo, professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, described preliminary findings that the skin microbiome functions differently in patients with AD than in those without.

Dr. Gallo and his colleagues took skin sloughs from 50 AD patients and 30 non-AD controls. Most of the Staphylococcus aureus bacteria on sloughs from AD patients were alive, while most were dead on sloughs from patients without AD. Normal subjects had skin biomes that were able to kill S. aureus, Dr. Gallo said in a plenary talk at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The investigators looked at the few species of normally occurring skin bacteria that can kill S. aureus, focusing on Staphylococcus hominis, which, they found, produces an antimicrobial peptide very effective against S. aureus. After mouse experiments showed S. hominis effective against S. aureus infection, Dr. Gallo and his colleagues began investigating its activity in a human patient. They isolated S. hominis from the skin of a patient, cultured it, and applied it in a topical cream. The result was a 1,000-fold drop in S. aureus colonization in the same patient. Dr. Gallo did not say how long the effect lasted or whether clinical symptoms abated.

“The pharmaceutical industry has been looking for antimicrobials in the jungles and the deep sea,” Dr. Gallo said. “We just swabbed an arm and found one that was really effective.” The findings suggest, he said, that “perhaps there are some therapeutic opportunities using the skin microbiome that aren’t 5 years away.” He added that his team has funding from NIH to continue this work as well as for a larger study using a similar approach that will be applicable in larger populations.

Dr. Gallo also mentioned new research showing that the skin microbiome goes quite a bit deeper than commonly understood, with immune-mediating bacteria found in the dermis and even the adipose layers. “We have to start thinking about skin in a different way,” he said. “These are not absolute barriers but highly evolved filters that permit selected microbes to interact.” Dr. Gallo has received research support from Galderma and Bayer and is listed on several patents for potential therapies held by his institution.

HOUSTON – New science suggests that the skin microbial environment may be manipulated in patients with atopic dermatitis in a way that could quell overgrowth of Staphylococcus aureus – meaning that the first microbiome-based therapies for AD might not be far away.

Dr. Richard L. Gallo, professor of medicine and pediatrics at the University of California, San Diego, described preliminary findings that the skin microbiome functions differently in patients with AD than in those without.

Dr. Gallo and his colleagues took skin sloughs from 50 AD patients and 30 non-AD controls. Most of the Staphylococcus aureus bacteria on sloughs from AD patients were alive, while most were dead on sloughs from patients without AD. Normal subjects had skin biomes that were able to kill S. aureus, Dr. Gallo said in a plenary talk at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology.

The investigators looked at the few species of normally occurring skin bacteria that can kill S. aureus, focusing on Staphylococcus hominis, which, they found, produces an antimicrobial peptide very effective against S. aureus. After mouse experiments showed S. hominis effective against S. aureus infection, Dr. Gallo and his colleagues began investigating its activity in a human patient. They isolated S. hominis from the skin of a patient, cultured it, and applied it in a topical cream. The result was a 1,000-fold drop in S. aureus colonization in the same patient. Dr. Gallo did not say how long the effect lasted or whether clinical symptoms abated.

“The pharmaceutical industry has been looking for antimicrobials in the jungles and the deep sea,” Dr. Gallo said. “We just swabbed an arm and found one that was really effective.” The findings suggest, he said, that “perhaps there are some therapeutic opportunities using the skin microbiome that aren’t 5 years away.” He added that his team has funding from NIH to continue this work as well as for a larger study using a similar approach that will be applicable in larger populations.

Dr. Gallo also mentioned new research showing that the skin microbiome goes quite a bit deeper than commonly understood, with immune-mediating bacteria found in the dermis and even the adipose layers. “We have to start thinking about skin in a different way,” he said. “These are not absolute barriers but highly evolved filters that permit selected microbes to interact.” Dr. Gallo has received research support from Galderma and Bayer and is listed on several patents for potential therapies held by his institution.

AT 2015 AAAAI ANNUAL MEETING