User login

Update on Management of Atopic Dermatitis in Young Children

Update on Management of Atopic Dermatitis in Young Children

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition associated with skin barrier impairment and immune system dysregulation.1 Development of AD in young children can present challenges in determining appropriate treatment regimens. Natural remedies for AD often are promoted on social media over traditional treatments, including topical corticosteroids (TCSs), which can contribute to corticophobia.2 Dermatologists play a critical role not only in optimizing topical therapy but also addressing patient interest in natural approaches to AD, including diet-related questions. This article outlines the role of diet and probiotics in pediatric AD and reviews the topical treatments currently approved for this patient population.

Diet and Probiotics

With a growing focus on natural therapies for AD, dietary interventions have come to the forefront. A prevalent theme among patients and their families is addressing gut health and allergic triggers. Broad elimination diets have not shown clinical benefit in patients with AD regardless of age,3 and in children, they may result in nutritional deficiencies, poor growth, and increased risk for IgE-mediated food allergies.4 If a true food allergy is identified based on positive IgE and an acute clinical reaction, elimination of the allergen may provide some benefit.5

The link between gut microbiota and skin health has driven an interest in the role of probiotics in the treatment of pediatric AD. A meta-analysis of 20 articles concluded that, whether administered to infants or breastfeeding mothers, use of probiotics overall led to a significant reduction in AD risk in infants (P=.001). Lactobacillus and mixed strains were effective.6 While broad elimination diets are not used to treat AD, probiotic supplementation can be considered for prevention of AD.

Topical Corticosteroids

Topical corticosteroids are the cornerstone of AD treatment; however, corticophobia among patients is on the rise, leading to poor adherence and suboptimal control of AD.7 Mild cutaneous adverse effects (AEs) including skin atrophy, striae, and telangiectasias may occur. Rarely, systemic AEs occur due to absorption of TCSs into the bloodstream, mainly with application of potent steroids over large body surface areas or under occlusion.8 When the optimal potency of a TCS is chosen and used appropriately, incidence of AEs from TCS use is very low.9

Counseling parents about risk factors that can lead to AEs during treatment with TCSs and formulating regimens that minimize these risks while maintaining efficacy increases adherence and outcomes. Pulse maintenance dosing of TCSs typically involves application 1 to 2 times weekly to areas of the skin that are prone to frequent outbreaks. Pulse maintenance dosing can reduce the incidence of AD flares while also decreasing the total amount of topical medication needed as compared to the reactive approach alone, thereby reducing risk for AEs.8

Steroid-Sparing Topical Treatments

Although TCSs are considered first-line agents, recently there has been an advent of steroid-sparing topical agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for pediatric patients with AD, including topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs), phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors, a Janus kinase inhibitor, and aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists. Offering steroid-sparing agents in these patients can help ease parental anxiety regarding TCS overuse.

Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors—Pimecrolimus cream 1% and tacrolimus ointment 0.03% are approved for patients aged 2 years and older and have anti-inflammatory and antipruritic effects equivalent to low-potency TCS. Tacrolimus ointment 0.1% is approved for patients aged 16 years and older with similar efficacy to a midpotency TCSs. Pimecrolimus cream 1% and tacrolimus ointment 0.03% often are used off-label in children younger than 2 years, as supported by clinical trials showing their safety and efficacy.10

Topical calcineurin inhibitors can replace or supplement TCSs, making TCIs a desirable option for avoidance of steroid-related AEs. The addition of a TCI to spot treatment or a pulse regimen in a young patient can reassure them and their caregivers that the provider is proactively reducing the risk of TCS overuse. The largest barrier to TCI use is the FDA’s black box warning based on the oral formulation of tacrolimus, citing a potential increased risk for lymphoma and skin cancer; however, there is no evidence for substantial systemic absorption of topical pimecrolimus or tacrolimus.11 Large task-force reviews have found no association between TCI use and development of malignancy.12,13 Based on the current data, counseling patients and their caregivers that this risk primarily is theoretical may help them more confidently integrate TCIs into their treatment regimen. Burning and tingling may occur in a minority of pediatric patients using TCIs for AD. Applying the medication to open wounds or inflamed skin increases the risk for stinging, but pretreatment with a short course of TCSs before transitioning to a TCI may boost tolerance.14

Phosphodiesterase 4 Inhibitors—Crisaborole ointment 2%, a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, is approved for children aged 3 months and older with mild to moderate AD. Its use has been more limited than TCSs and TCIs, as local irritation including stinging and burning can occur in up to 50% of patients.15 One study comparing crisaborole 2% with tacrolimus 0.03% revealed greater improvement with tacrolimus.16 A second phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor approved for once-daily use in children aged 6 years and older with mild to moderate AD is roflumilast cream 0.15%. Roflumilast reduces eczema severity and pruritus, with AEs also limited to application-site stinging and burning.17

Janus Kinase Inhibitor—Ruxolitinib cream 1.5%, a Janus kinase inhibitor, has been approved by the FDA since 2023 for twice-daily use in children aged 12 years and older with AD. Similar to TCIs, ruxolitinib cream carries a black box warning. Short-term safety data on ruxolitinib cream have revealed low levels of ruxolitinib concentration in plasma18; however, long-term studies on topical Janus kinase inhibitors for AD in pediatric and adult populations are lacking. To reduce the risk for systemic absorption, recommendations include limiting usage to 60 g per week and limiting treatment to less than 20% of the body surface area.19 Ruxolitinib has efficacy similar to or possibly superior to triamcinolone 0.1%.20 Ruxolitinib is emerging as a promising nonsteroidal option that potentially is highly efficacious and well tolerated without cutaneous AEs.

Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Agonist—Tapinarof cream 1% is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that has been approved by the FDA since 2024 for children aged 2 years and older as a once-daily treatment for moderate to severe AD. Adverse events include folliculitis, nasopharyngitis, and headache, which are mostly mild or moderate.21

Final Thoughts

Topical management of pediatric AD includes traditional therapy with TCSs and newer steroid-sparing agents, which can help address corticophobia. Anticipatory guidance regarding the safety and long-term effects of individual therapies is critical to ensuring patient adherence to treatment regimens. Probiotics may help prevent pediatric AD, but future studies are needed to determine their role in treatment.

- Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, et al. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:1.

- Voillot P, Riche B, Portafax M, et al. Social media platforms listening study on atopic dermatitis: quantitative and qualitative findings. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24:E31140.

- Bath-Hextall F, Delamere FM, Williams HC. Dietary exclusions for improving established atopic eczema in adults and children: systematic review. Allergy. 2009;64:258-264.

- Rustad AM, Nickles MA, Bilimoria SN, et al. The role of diet modification in atopic dermatitis: navigating the complexity. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:27-36.

- Khan A, Adalsteinsson J, Whitaker-Worth DL. Atopic dermatitis and nutrition. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:135-144.

- Chen L, Ni Y, Wu X, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of atopic dermatitis in infants from different geographic regions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:2931-2939.

- Herzum A, Occella C, Gariazzo L, et al. Corticophobia among parents of children with atopic dermatitis: assessing major and minor risk factors for high TOPICOP scores. J Clin Med. 2023;12:6813.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-132.

- Callen J, Chamlin S, Eichenfield LF, et al. A systematic review of the safety of topical therapies for atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:203-221.

- Reitamo S, Rustin M, Ruzicka T, et al. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus ointment compared with that of hydrocortisone butyrate ointment in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:547-555.

- Thaçi D, Salgo R. Malignancy concerns of topical calcineurin inhibitors for atopic dermatitis: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:52-56.

- Berger TG, Duvic M, Van Voorhees AS, et al. The use of topical calcineurin inhibitors in dermatology: safety concerns. report of the AAD Association Task Force. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:818-823.

- Fonacier L, Spergel J, Charlesworth EN, et al. Report of the Topical Calcineurin Inhibitor Task Force of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1249-1253.

- Eichenfield LF, Lucky AW, Boguniewicz M, et al. Safety and efficacy of pimecrolimus (ASM 981) cream 1% in the treatment of mild and moderate atopic dermatitis in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:495-504.

- Lin CPL, Gordon S, Her MJ, et al. A retrospective study: application site pain with the use of crisaborole, a topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1451-1453.

- Ryan Wolf J, Chen A, Wieser J, et al. Improved patient- and caregiver-reported outcomes distinguish tacrolimus 0.03% from crisaborole in children with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024;38:1364-1372.

- Simpson EL, Eichenfield LF, Alonso-Llamazares J, et al. Roflumilast cream, 0.15%, for atopic dermatitis in adults and children: INTEGUMENT-1 and INTEGUMENT-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:1161-1170.

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Long-term safety and disease control with ruxolitinib cream in atopic dermatitis: results from two phase 3 studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:1008-1016.

- Sidbury R, Alikhan A, Bercovitch L, et al. Guidelines of carefor the management of atopic dermatitis in adults with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:E1-E20.

- Sadeghi S, Mohandesi NA. Efficacy and safety of topical JAK inhibitors in the treatment of atopic dermatitis in paediatrics and adults: a systematic review. Exp Dermatol. 2023;32:599-610.

- Silverberg JI, Eichenfield LF, Hebert AA, et al. Tapinarof cream 1% once daily: significant efficacy in the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adults and children down to 2 years of age in the pivotal phase 3 ADORING trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:457-465.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition associated with skin barrier impairment and immune system dysregulation.1 Development of AD in young children can present challenges in determining appropriate treatment regimens. Natural remedies for AD often are promoted on social media over traditional treatments, including topical corticosteroids (TCSs), which can contribute to corticophobia.2 Dermatologists play a critical role not only in optimizing topical therapy but also addressing patient interest in natural approaches to AD, including diet-related questions. This article outlines the role of diet and probiotics in pediatric AD and reviews the topical treatments currently approved for this patient population.

Diet and Probiotics

With a growing focus on natural therapies for AD, dietary interventions have come to the forefront. A prevalent theme among patients and their families is addressing gut health and allergic triggers. Broad elimination diets have not shown clinical benefit in patients with AD regardless of age,3 and in children, they may result in nutritional deficiencies, poor growth, and increased risk for IgE-mediated food allergies.4 If a true food allergy is identified based on positive IgE and an acute clinical reaction, elimination of the allergen may provide some benefit.5

The link between gut microbiota and skin health has driven an interest in the role of probiotics in the treatment of pediatric AD. A meta-analysis of 20 articles concluded that, whether administered to infants or breastfeeding mothers, use of probiotics overall led to a significant reduction in AD risk in infants (P=.001). Lactobacillus and mixed strains were effective.6 While broad elimination diets are not used to treat AD, probiotic supplementation can be considered for prevention of AD.

Topical Corticosteroids

Topical corticosteroids are the cornerstone of AD treatment; however, corticophobia among patients is on the rise, leading to poor adherence and suboptimal control of AD.7 Mild cutaneous adverse effects (AEs) including skin atrophy, striae, and telangiectasias may occur. Rarely, systemic AEs occur due to absorption of TCSs into the bloodstream, mainly with application of potent steroids over large body surface areas or under occlusion.8 When the optimal potency of a TCS is chosen and used appropriately, incidence of AEs from TCS use is very low.9

Counseling parents about risk factors that can lead to AEs during treatment with TCSs and formulating regimens that minimize these risks while maintaining efficacy increases adherence and outcomes. Pulse maintenance dosing of TCSs typically involves application 1 to 2 times weekly to areas of the skin that are prone to frequent outbreaks. Pulse maintenance dosing can reduce the incidence of AD flares while also decreasing the total amount of topical medication needed as compared to the reactive approach alone, thereby reducing risk for AEs.8

Steroid-Sparing Topical Treatments

Although TCSs are considered first-line agents, recently there has been an advent of steroid-sparing topical agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for pediatric patients with AD, including topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs), phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors, a Janus kinase inhibitor, and aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists. Offering steroid-sparing agents in these patients can help ease parental anxiety regarding TCS overuse.

Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors—Pimecrolimus cream 1% and tacrolimus ointment 0.03% are approved for patients aged 2 years and older and have anti-inflammatory and antipruritic effects equivalent to low-potency TCS. Tacrolimus ointment 0.1% is approved for patients aged 16 years and older with similar efficacy to a midpotency TCSs. Pimecrolimus cream 1% and tacrolimus ointment 0.03% often are used off-label in children younger than 2 years, as supported by clinical trials showing their safety and efficacy.10

Topical calcineurin inhibitors can replace or supplement TCSs, making TCIs a desirable option for avoidance of steroid-related AEs. The addition of a TCI to spot treatment or a pulse regimen in a young patient can reassure them and their caregivers that the provider is proactively reducing the risk of TCS overuse. The largest barrier to TCI use is the FDA’s black box warning based on the oral formulation of tacrolimus, citing a potential increased risk for lymphoma and skin cancer; however, there is no evidence for substantial systemic absorption of topical pimecrolimus or tacrolimus.11 Large task-force reviews have found no association between TCI use and development of malignancy.12,13 Based on the current data, counseling patients and their caregivers that this risk primarily is theoretical may help them more confidently integrate TCIs into their treatment regimen. Burning and tingling may occur in a minority of pediatric patients using TCIs for AD. Applying the medication to open wounds or inflamed skin increases the risk for stinging, but pretreatment with a short course of TCSs before transitioning to a TCI may boost tolerance.14

Phosphodiesterase 4 Inhibitors—Crisaborole ointment 2%, a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, is approved for children aged 3 months and older with mild to moderate AD. Its use has been more limited than TCSs and TCIs, as local irritation including stinging and burning can occur in up to 50% of patients.15 One study comparing crisaborole 2% with tacrolimus 0.03% revealed greater improvement with tacrolimus.16 A second phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor approved for once-daily use in children aged 6 years and older with mild to moderate AD is roflumilast cream 0.15%. Roflumilast reduces eczema severity and pruritus, with AEs also limited to application-site stinging and burning.17

Janus Kinase Inhibitor—Ruxolitinib cream 1.5%, a Janus kinase inhibitor, has been approved by the FDA since 2023 for twice-daily use in children aged 12 years and older with AD. Similar to TCIs, ruxolitinib cream carries a black box warning. Short-term safety data on ruxolitinib cream have revealed low levels of ruxolitinib concentration in plasma18; however, long-term studies on topical Janus kinase inhibitors for AD in pediatric and adult populations are lacking. To reduce the risk for systemic absorption, recommendations include limiting usage to 60 g per week and limiting treatment to less than 20% of the body surface area.19 Ruxolitinib has efficacy similar to or possibly superior to triamcinolone 0.1%.20 Ruxolitinib is emerging as a promising nonsteroidal option that potentially is highly efficacious and well tolerated without cutaneous AEs.

Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Agonist—Tapinarof cream 1% is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that has been approved by the FDA since 2024 for children aged 2 years and older as a once-daily treatment for moderate to severe AD. Adverse events include folliculitis, nasopharyngitis, and headache, which are mostly mild or moderate.21

Final Thoughts

Topical management of pediatric AD includes traditional therapy with TCSs and newer steroid-sparing agents, which can help address corticophobia. Anticipatory guidance regarding the safety and long-term effects of individual therapies is critical to ensuring patient adherence to treatment regimens. Probiotics may help prevent pediatric AD, but future studies are needed to determine their role in treatment.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic inflammatory skin condition associated with skin barrier impairment and immune system dysregulation.1 Development of AD in young children can present challenges in determining appropriate treatment regimens. Natural remedies for AD often are promoted on social media over traditional treatments, including topical corticosteroids (TCSs), which can contribute to corticophobia.2 Dermatologists play a critical role not only in optimizing topical therapy but also addressing patient interest in natural approaches to AD, including diet-related questions. This article outlines the role of diet and probiotics in pediatric AD and reviews the topical treatments currently approved for this patient population.

Diet and Probiotics

With a growing focus on natural therapies for AD, dietary interventions have come to the forefront. A prevalent theme among patients and their families is addressing gut health and allergic triggers. Broad elimination diets have not shown clinical benefit in patients with AD regardless of age,3 and in children, they may result in nutritional deficiencies, poor growth, and increased risk for IgE-mediated food allergies.4 If a true food allergy is identified based on positive IgE and an acute clinical reaction, elimination of the allergen may provide some benefit.5

The link between gut microbiota and skin health has driven an interest in the role of probiotics in the treatment of pediatric AD. A meta-analysis of 20 articles concluded that, whether administered to infants or breastfeeding mothers, use of probiotics overall led to a significant reduction in AD risk in infants (P=.001). Lactobacillus and mixed strains were effective.6 While broad elimination diets are not used to treat AD, probiotic supplementation can be considered for prevention of AD.

Topical Corticosteroids

Topical corticosteroids are the cornerstone of AD treatment; however, corticophobia among patients is on the rise, leading to poor adherence and suboptimal control of AD.7 Mild cutaneous adverse effects (AEs) including skin atrophy, striae, and telangiectasias may occur. Rarely, systemic AEs occur due to absorption of TCSs into the bloodstream, mainly with application of potent steroids over large body surface areas or under occlusion.8 When the optimal potency of a TCS is chosen and used appropriately, incidence of AEs from TCS use is very low.9

Counseling parents about risk factors that can lead to AEs during treatment with TCSs and formulating regimens that minimize these risks while maintaining efficacy increases adherence and outcomes. Pulse maintenance dosing of TCSs typically involves application 1 to 2 times weekly to areas of the skin that are prone to frequent outbreaks. Pulse maintenance dosing can reduce the incidence of AD flares while also decreasing the total amount of topical medication needed as compared to the reactive approach alone, thereby reducing risk for AEs.8

Steroid-Sparing Topical Treatments

Although TCSs are considered first-line agents, recently there has been an advent of steroid-sparing topical agents approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for pediatric patients with AD, including topical calcineurin inhibitors (TCIs), phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitors, a Janus kinase inhibitor, and aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonists. Offering steroid-sparing agents in these patients can help ease parental anxiety regarding TCS overuse.

Topical Calcineurin Inhibitors—Pimecrolimus cream 1% and tacrolimus ointment 0.03% are approved for patients aged 2 years and older and have anti-inflammatory and antipruritic effects equivalent to low-potency TCS. Tacrolimus ointment 0.1% is approved for patients aged 16 years and older with similar efficacy to a midpotency TCSs. Pimecrolimus cream 1% and tacrolimus ointment 0.03% often are used off-label in children younger than 2 years, as supported by clinical trials showing their safety and efficacy.10

Topical calcineurin inhibitors can replace or supplement TCSs, making TCIs a desirable option for avoidance of steroid-related AEs. The addition of a TCI to spot treatment or a pulse regimen in a young patient can reassure them and their caregivers that the provider is proactively reducing the risk of TCS overuse. The largest barrier to TCI use is the FDA’s black box warning based on the oral formulation of tacrolimus, citing a potential increased risk for lymphoma and skin cancer; however, there is no evidence for substantial systemic absorption of topical pimecrolimus or tacrolimus.11 Large task-force reviews have found no association between TCI use and development of malignancy.12,13 Based on the current data, counseling patients and their caregivers that this risk primarily is theoretical may help them more confidently integrate TCIs into their treatment regimen. Burning and tingling may occur in a minority of pediatric patients using TCIs for AD. Applying the medication to open wounds or inflamed skin increases the risk for stinging, but pretreatment with a short course of TCSs before transitioning to a TCI may boost tolerance.14

Phosphodiesterase 4 Inhibitors—Crisaborole ointment 2%, a phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor, is approved for children aged 3 months and older with mild to moderate AD. Its use has been more limited than TCSs and TCIs, as local irritation including stinging and burning can occur in up to 50% of patients.15 One study comparing crisaborole 2% with tacrolimus 0.03% revealed greater improvement with tacrolimus.16 A second phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor approved for once-daily use in children aged 6 years and older with mild to moderate AD is roflumilast cream 0.15%. Roflumilast reduces eczema severity and pruritus, with AEs also limited to application-site stinging and burning.17

Janus Kinase Inhibitor—Ruxolitinib cream 1.5%, a Janus kinase inhibitor, has been approved by the FDA since 2023 for twice-daily use in children aged 12 years and older with AD. Similar to TCIs, ruxolitinib cream carries a black box warning. Short-term safety data on ruxolitinib cream have revealed low levels of ruxolitinib concentration in plasma18; however, long-term studies on topical Janus kinase inhibitors for AD in pediatric and adult populations are lacking. To reduce the risk for systemic absorption, recommendations include limiting usage to 60 g per week and limiting treatment to less than 20% of the body surface area.19 Ruxolitinib has efficacy similar to or possibly superior to triamcinolone 0.1%.20 Ruxolitinib is emerging as a promising nonsteroidal option that potentially is highly efficacious and well tolerated without cutaneous AEs.

Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Agonist—Tapinarof cream 1% is an aryl hydrocarbon receptor agonist that has been approved by the FDA since 2024 for children aged 2 years and older as a once-daily treatment for moderate to severe AD. Adverse events include folliculitis, nasopharyngitis, and headache, which are mostly mild or moderate.21

Final Thoughts

Topical management of pediatric AD includes traditional therapy with TCSs and newer steroid-sparing agents, which can help address corticophobia. Anticipatory guidance regarding the safety and long-term effects of individual therapies is critical to ensuring patient adherence to treatment regimens. Probiotics may help prevent pediatric AD, but future studies are needed to determine their role in treatment.

- Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, et al. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:1.

- Voillot P, Riche B, Portafax M, et al. Social media platforms listening study on atopic dermatitis: quantitative and qualitative findings. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24:E31140.

- Bath-Hextall F, Delamere FM, Williams HC. Dietary exclusions for improving established atopic eczema in adults and children: systematic review. Allergy. 2009;64:258-264.

- Rustad AM, Nickles MA, Bilimoria SN, et al. The role of diet modification in atopic dermatitis: navigating the complexity. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:27-36.

- Khan A, Adalsteinsson J, Whitaker-Worth DL. Atopic dermatitis and nutrition. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:135-144.

- Chen L, Ni Y, Wu X, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of atopic dermatitis in infants from different geographic regions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:2931-2939.

- Herzum A, Occella C, Gariazzo L, et al. Corticophobia among parents of children with atopic dermatitis: assessing major and minor risk factors for high TOPICOP scores. J Clin Med. 2023;12:6813.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-132.

- Callen J, Chamlin S, Eichenfield LF, et al. A systematic review of the safety of topical therapies for atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:203-221.

- Reitamo S, Rustin M, Ruzicka T, et al. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus ointment compared with that of hydrocortisone butyrate ointment in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:547-555.

- Thaçi D, Salgo R. Malignancy concerns of topical calcineurin inhibitors for atopic dermatitis: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:52-56.

- Berger TG, Duvic M, Van Voorhees AS, et al. The use of topical calcineurin inhibitors in dermatology: safety concerns. report of the AAD Association Task Force. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:818-823.

- Fonacier L, Spergel J, Charlesworth EN, et al. Report of the Topical Calcineurin Inhibitor Task Force of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1249-1253.

- Eichenfield LF, Lucky AW, Boguniewicz M, et al. Safety and efficacy of pimecrolimus (ASM 981) cream 1% in the treatment of mild and moderate atopic dermatitis in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:495-504.

- Lin CPL, Gordon S, Her MJ, et al. A retrospective study: application site pain with the use of crisaborole, a topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1451-1453.

- Ryan Wolf J, Chen A, Wieser J, et al. Improved patient- and caregiver-reported outcomes distinguish tacrolimus 0.03% from crisaborole in children with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024;38:1364-1372.

- Simpson EL, Eichenfield LF, Alonso-Llamazares J, et al. Roflumilast cream, 0.15%, for atopic dermatitis in adults and children: INTEGUMENT-1 and INTEGUMENT-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:1161-1170.

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Long-term safety and disease control with ruxolitinib cream in atopic dermatitis: results from two phase 3 studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:1008-1016.

- Sidbury R, Alikhan A, Bercovitch L, et al. Guidelines of carefor the management of atopic dermatitis in adults with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:E1-E20.

- Sadeghi S, Mohandesi NA. Efficacy and safety of topical JAK inhibitors in the treatment of atopic dermatitis in paediatrics and adults: a systematic review. Exp Dermatol. 2023;32:599-610.

- Silverberg JI, Eichenfield LF, Hebert AA, et al. Tapinarof cream 1% once daily: significant efficacy in the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adults and children down to 2 years of age in the pivotal phase 3 ADORING trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:457-465.

- Weidinger S, Beck LA, Bieber T, et al. Atopic dermatitis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:1.

- Voillot P, Riche B, Portafax M, et al. Social media platforms listening study on atopic dermatitis: quantitative and qualitative findings. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24:E31140.

- Bath-Hextall F, Delamere FM, Williams HC. Dietary exclusions for improving established atopic eczema in adults and children: systematic review. Allergy. 2009;64:258-264.

- Rustad AM, Nickles MA, Bilimoria SN, et al. The role of diet modification in atopic dermatitis: navigating the complexity. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23:27-36.

- Khan A, Adalsteinsson J, Whitaker-Worth DL. Atopic dermatitis and nutrition. Clin Dermatol. 2022;40:135-144.

- Chen L, Ni Y, Wu X, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of atopic dermatitis in infants from different geographic regions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2022;33:2931-2939.

- Herzum A, Occella C, Gariazzo L, et al. Corticophobia among parents of children with atopic dermatitis: assessing major and minor risk factors for high TOPICOP scores. J Clin Med. 2023;12:6813.

- Eichenfield LF, Tom WL, Berger TG, et al. Guidelines of care for the management of atopic dermatitis: section 2. management and treatment of atopic dermatitis with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71:116-132.

- Callen J, Chamlin S, Eichenfield LF, et al. A systematic review of the safety of topical therapies for atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2007;156:203-221.

- Reitamo S, Rustin M, Ruzicka T, et al. Efficacy and safety of tacrolimus ointment compared with that of hydrocortisone butyrate ointment in adult patients with atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:547-555.

- Thaçi D, Salgo R. Malignancy concerns of topical calcineurin inhibitors for atopic dermatitis: facts and controversies. Clin Dermatol. 2010;28:52-56.

- Berger TG, Duvic M, Van Voorhees AS, et al. The use of topical calcineurin inhibitors in dermatology: safety concerns. report of the AAD Association Task Force. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:818-823.

- Fonacier L, Spergel J, Charlesworth EN, et al. Report of the Topical Calcineurin Inhibitor Task Force of the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology and the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;115:1249-1253.

- Eichenfield LF, Lucky AW, Boguniewicz M, et al. Safety and efficacy of pimecrolimus (ASM 981) cream 1% in the treatment of mild and moderate atopic dermatitis in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2002;46:495-504.

- Lin CPL, Gordon S, Her MJ, et al. A retrospective study: application site pain with the use of crisaborole, a topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80:1451-1453.

- Ryan Wolf J, Chen A, Wieser J, et al. Improved patient- and caregiver-reported outcomes distinguish tacrolimus 0.03% from crisaborole in children with atopic dermatitis. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2024;38:1364-1372.

- Simpson EL, Eichenfield LF, Alonso-Llamazares J, et al. Roflumilast cream, 0.15%, for atopic dermatitis in adults and children: INTEGUMENT-1 and INTEGUMENT-2 randomized clinical trials. JAMA Dermatol. 2024;160:1161-1170.

- Papp K, Szepietowski JC, Kircik L, et al. Long-term safety and disease control with ruxolitinib cream in atopic dermatitis: results from two phase 3 studies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;88:1008-1016.

- Sidbury R, Alikhan A, Bercovitch L, et al. Guidelines of carefor the management of atopic dermatitis in adults with topical therapies. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2023;89:E1-E20.

- Sadeghi S, Mohandesi NA. Efficacy and safety of topical JAK inhibitors in the treatment of atopic dermatitis in paediatrics and adults: a systematic review. Exp Dermatol. 2023;32:599-610.

- Silverberg JI, Eichenfield LF, Hebert AA, et al. Tapinarof cream 1% once daily: significant efficacy in the treatment of moderate to severe atopic dermatitis in adults and children down to 2 years of age in the pivotal phase 3 ADORING trials. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2024;91:457-465.

Update on Management of Atopic Dermatitis in Young Children

Update on Management of Atopic Dermatitis in Young Children

Epidemiologic and Clinical Evaluation of the Bidirectional Link Between Molluscum Contagiosum and Atopic Dermatitis in Children

Epidemiologic and Clinical Evaluation of the Bidirectional Link Between Molluscum Contagiosum and Atopic Dermatitis in Children

Molluscum contagiosum (MC), which is caused by a DNA virus in the Poxviridae family, is a common viral skin infection that primarily affects children.1-4 The reported incidence and prevalence of MC exhibit notable geographic variation. Worldwide, annual incidence rates per 1000 individuals range from 3.1 to 25, and prevalence ranges from 0.27% to 34.6%.2-7

Molluscum contagiosum is diagnosed clinically and typically manifests as smooth, flesh-colored papules measuring 2 to 6 mm in diameter with central umbilication. It can manifest as a single lesion or multiple clustered lesions, or in a disseminated pattern. The primary mode of transmission is through contact with skin, lesions, or contaminated personal items, or via self-inoculation. The majority of cases are asymptomatic, but in some patients, MC may be associated with pruritus, tenderness, erythema, or irritation. When present, secondary bacterial infections can cause localized inflammation and pain.1,3,4 The pathogenesis hinges on MC virus replication within keratinocytes, disrupting cellular differentiation and keratinization. The virus persists in the host by influencing the immune response through various mechanisms, including interference with signaling pathways, apoptosis inhibition, and antigen presentation disruption.3,4

Molluscum contagiosum typically follows a self-limiting trajectory, resolving over several months to 2 years.3,4 The resolution timeframe is intricately linked to variables such as the patient’s immune profile, lesion burden, and treatment approach. For symptomatic lesions, a variety of treatment options have been described, including physical ablation (eg, cryotherapy, curettage) and topical agents such as potassium hydroxide, cantharidin, imiquimod, and salicylic acid.3,4,8,9

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common chronic relapsing inflammatory skin disorder. In the United States, its prevalence ranges from 15% to 30% in children and from 2% to 10% in adults, with ongoing evidence of a growing global incidence.10-14 While AD can emerge at any age, typical onset is during early childhood. The clinical manifestation of AD includes a spectrum of eczematous features, often accompanied by persistent itching. The pathogenesis is multifactorial, involving a complex interplay of genetic, immunologic, and environmental factors. Key contributors to this multifaceted process encompass a compromised epidermal barrier, alterations in the skin microbiome, and an immune dysregulation promoting a type 2 immune response. Epidermal barrier dysfunction can be attributed to various factors, including diminished ceramide production, altered lipid composition, the release of inflammatory mediators, and mechanical damage from the persistent itch-scratch cycle.10-13,15 These factors or their interplay may enhance the susceptibility of patients with AD to infections.

Several studies conducted across various geographic regions examining the relationship between MC and AD have reported variable findings.2,6,7,16-21 Published studies have reported a prevalence of AD in children with MC ranging from 13.2% to 43%.2,6,7,16-21 Although some studies suggest a higher rate of atopy in patients with MC, not all research has confirmed this association.16,21 Dohil et al2 reported a greater number of MC lesions in children with AD than those without an atopic background. Silverberg20 reported that in 10% (5/50) of children with MC, the onset of AD was triggered, and in 22% (11/50) MC was associated with flares of pre-existing AD.

In this study, we aimed to assess MC infection rates in children with AD, analyze the epidemiologic aspects and severity differences between atopic children with and without MC infection, and compare data from atopic and nonatopic children with MC.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, we analyzed the medical records of pediatric patients diagnosed with MC, AD, or both conditions at an outpatient dermatology practice in Netanya, HaSharon, Israel, from September 2013 to August 2022. Data were collected from the electronic medical records and included patient demographics, the clinical presentation of MC and/or AD at diagnosis, and the duration of both conditions. Only patients with complete data and at least 6 months of follow-up were included. Key epidemiologic characteristics assessed included patient sex, age at the initial visit, and age at the onset of MC and/or AD. Diagnoses of MC and AD were established through clinical examinations conducted by dermatologists. The clinical evaluation of AD encompassed the assessment of body surface area involvement (categorized as <5%, 5%-10%, or >10%). Atopic dermatitis severity was classified as mild, moderate, or severe using the validated Investigator Global Assessment Scale for Atopic Dermatitis.22 Clinical evaluation of MC included assessment of the number of lesions (categorized as ≤4, 5-9, or ≥10), presence of inflammatory lesions, and resolution times for individual lesions (categorized as <1 week, several weeks, or unknown), as well as the overall resolution time for all lesions (categorized as <6 months, 6-12 months, 13-18 months, or >18 months). The temporal relationship between the appearance of MC and AD also was assessed.

Statistical Analysis—Numbers and percentages were used for categorical variables. Continuous variables were represented by mean and standard deviation. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test, and continuous variables between groups were compared using the Student t test. All statistical tests were 2-sided, with statistical significance defined as P≤.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 28 (IBM).

Results

Study Population—A total of 610 children were included in the study; 263 (43%) were female and 347 (57%) were male. The patients ranged in age from 4 months to 10 years, with a mean (SD) age of 4.87 (1.82) years. Five hundred fifty-six (91%) patients had AD, and 336 (55%) had MC. Within this cohort, 274 (45%) children had AD only, 54 (9%) had MC only, and 282 (46%) had both AD and MC. Regarding the temporal sequence, among the 282 children who had both AD and MC, AD preceded MC in 203 (72%) cases, both conditions were diagnosed concomitantly in 43 (15%) cases, and MC preceded AD in 36 (13%) cases. For cases in which the MC diagnosis followed the diagnosis of AD, the mean (SD) time between each diagnosis was 3.17 (1.5) years.

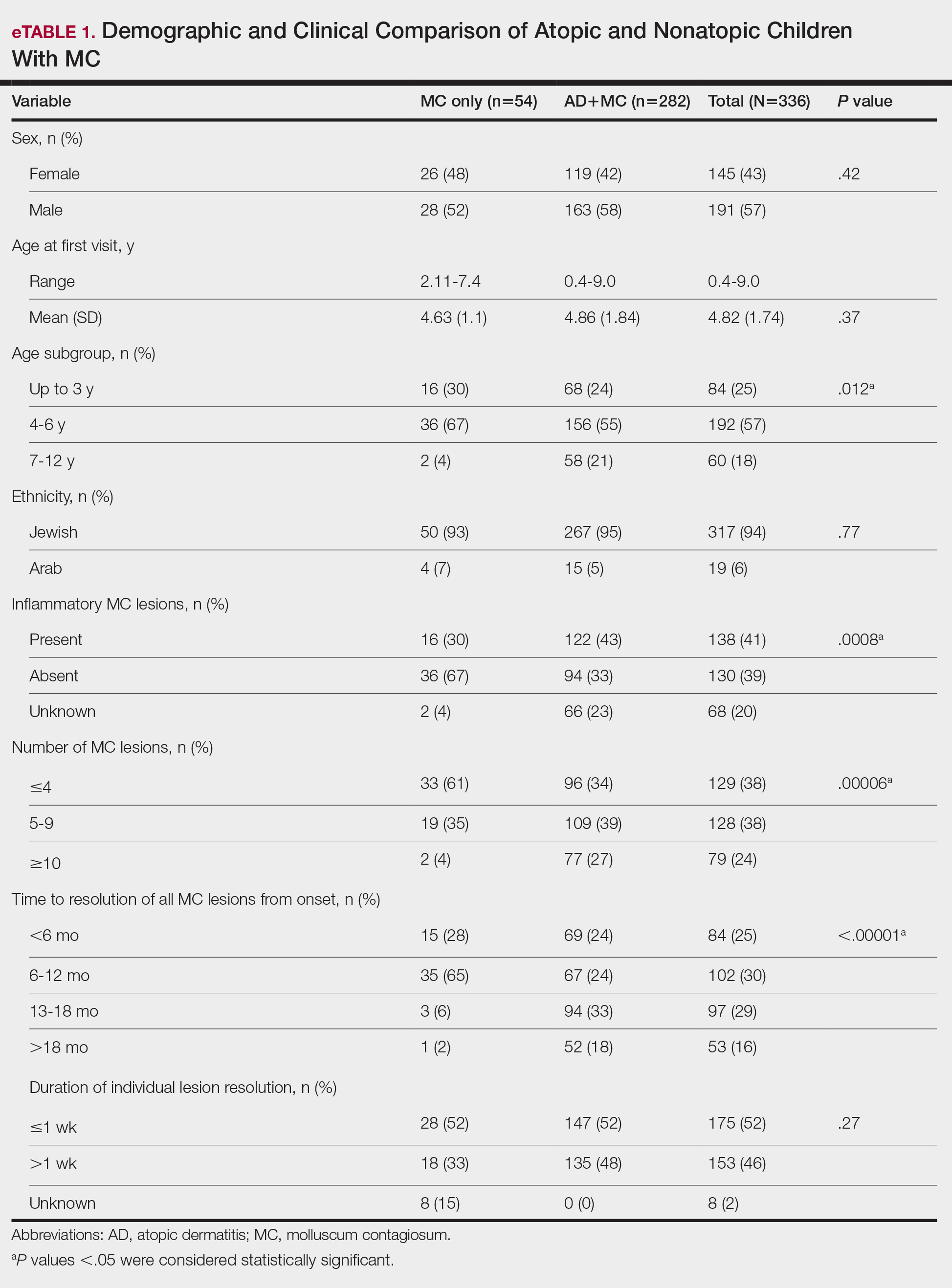

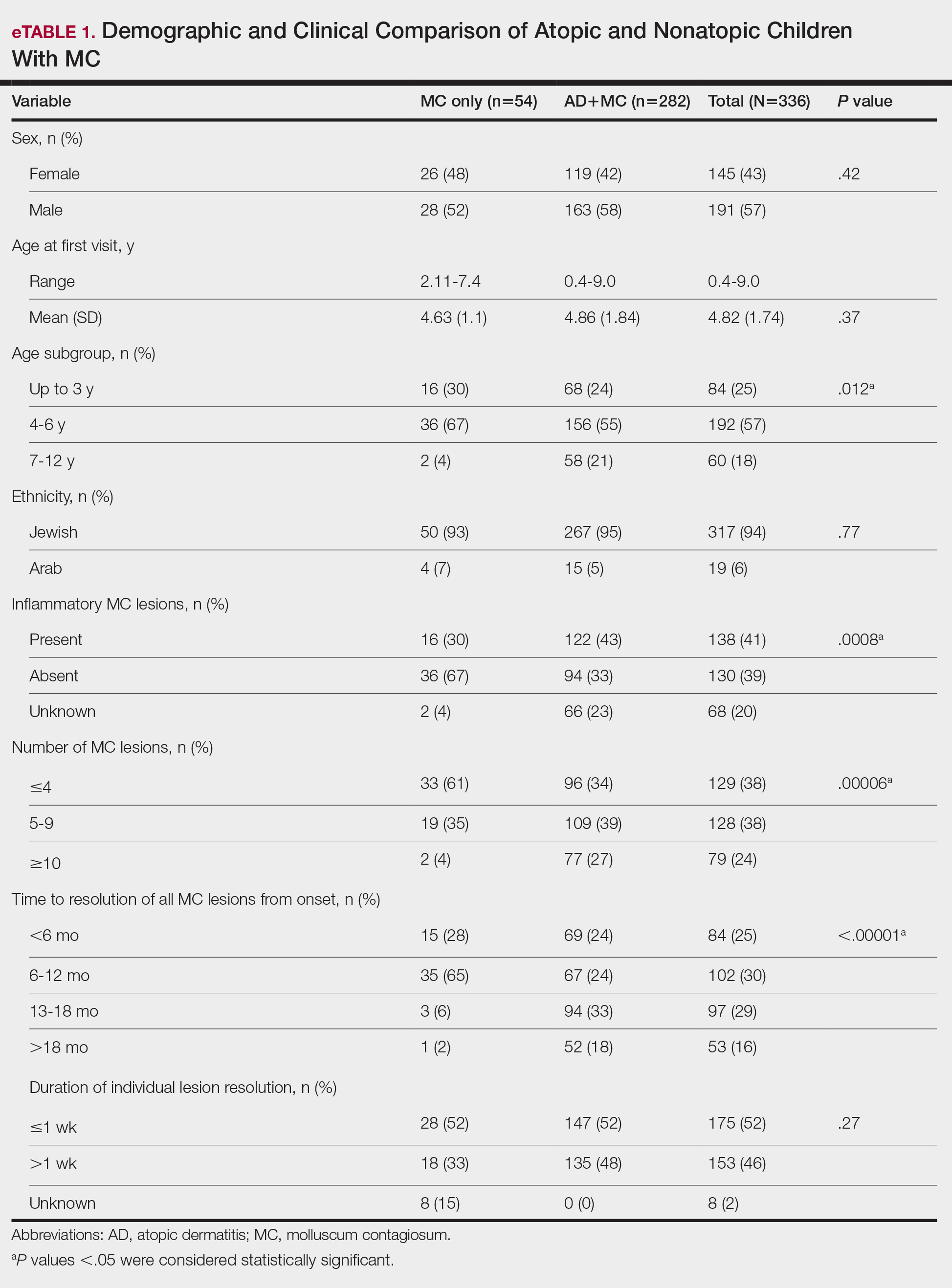

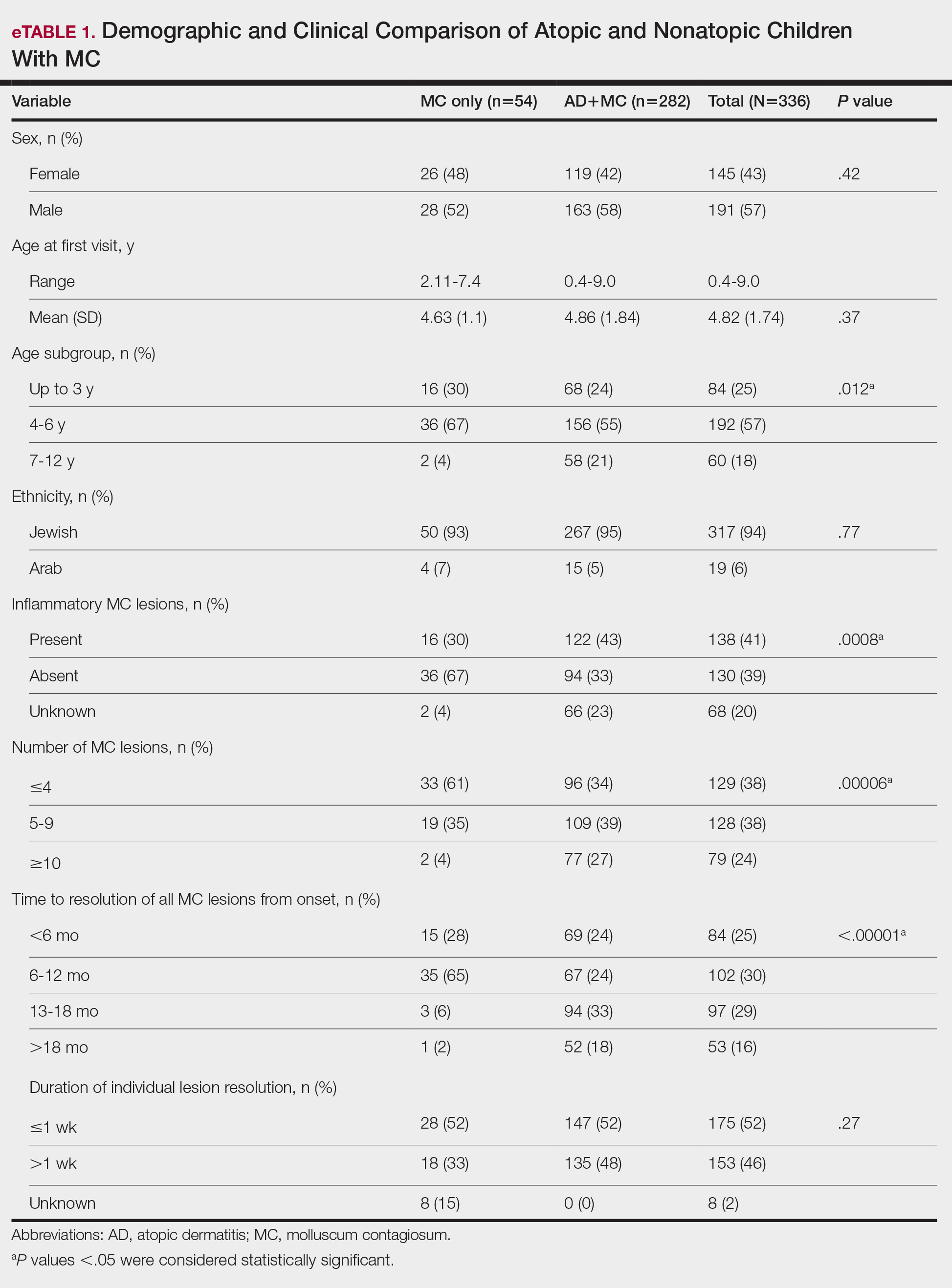

Comparison of Atopic and Nonatopic Children With MC—Although a higher proportion of males were diagnosed with MC (with or without concurrent AD), the differences in sex distribution between the 2 groups did not reach statistical significance. Among all children with MC, the majority (81.5% [274/336]) were aged 1 to 6 years at presentation. Patients with MC as their sole diagnosis had a similar mean age compared with those with concurrent AD. However, a detailed age subgroup analysis revealed a notable distinction: in the group with MC as the sole diagnosis, the majority (95% [51/54]) were younger than 7 years. In contrast, in the combined MC and AD group, MC manifested across a wider age range, with 21% (58/282) of patients being older than 7 years. In MC cases associated with AD, a notably higher lesion count and increased local inflammatory response were observed compared to those without AD. The time for complete resolution of all MC lesions was substantially prolonged in patients with comorbid AD. Specifically, 93% (50/54) of patients with MC without comorbid AD achieved full resolution within 1 year, whereas 52% (146/282) of patients with comorbid AD required more than 1 year for resolution (eTable 1).

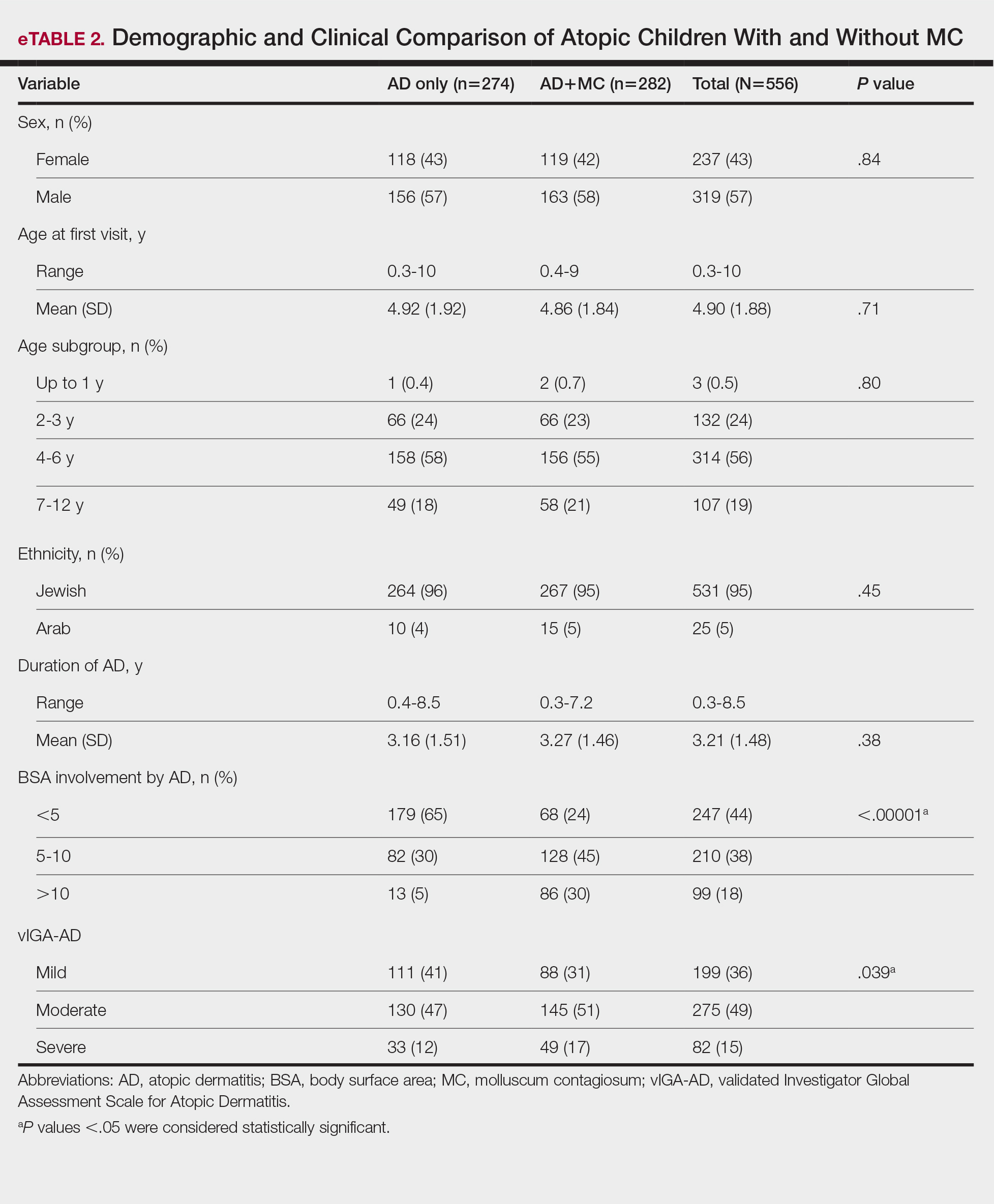

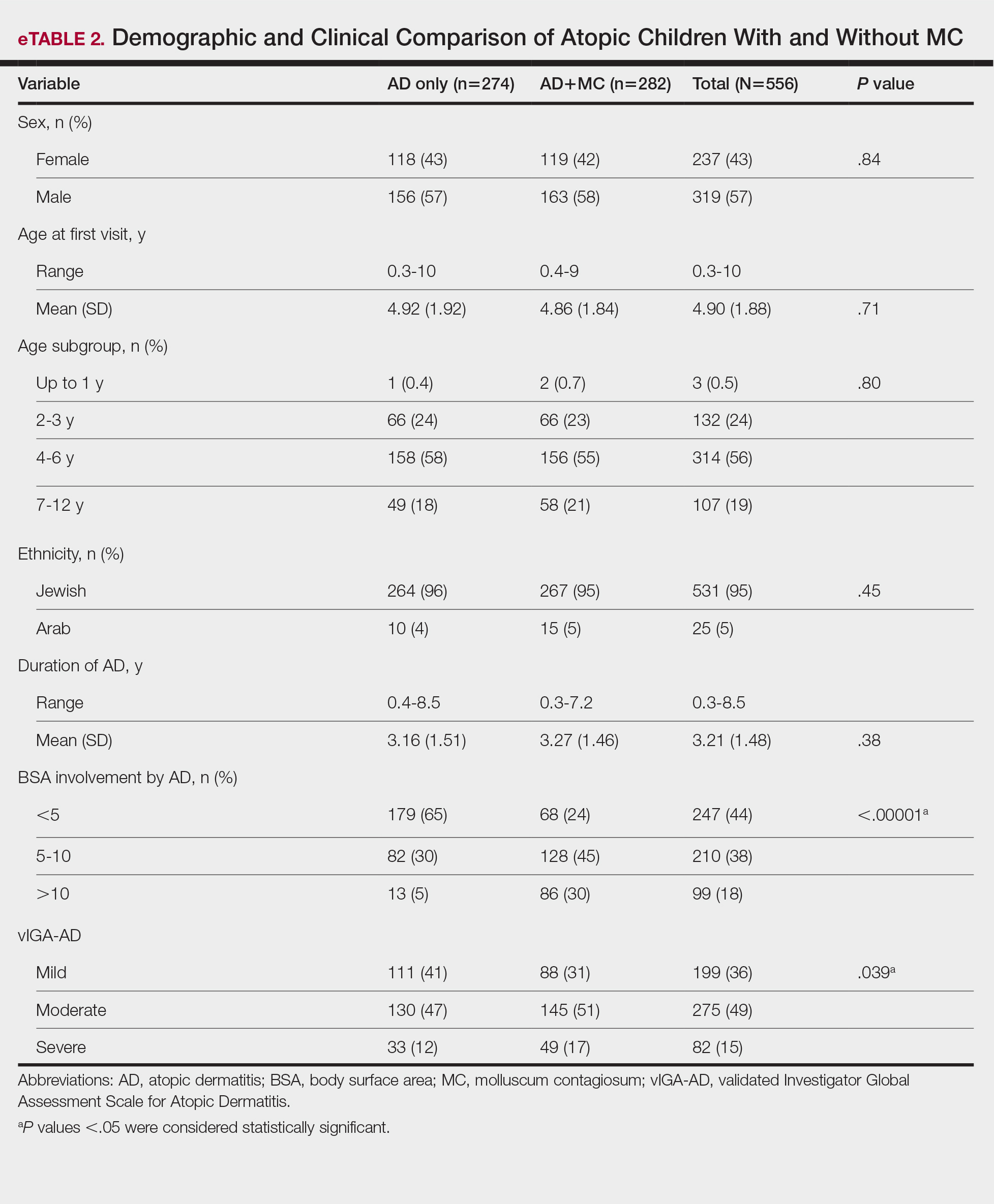

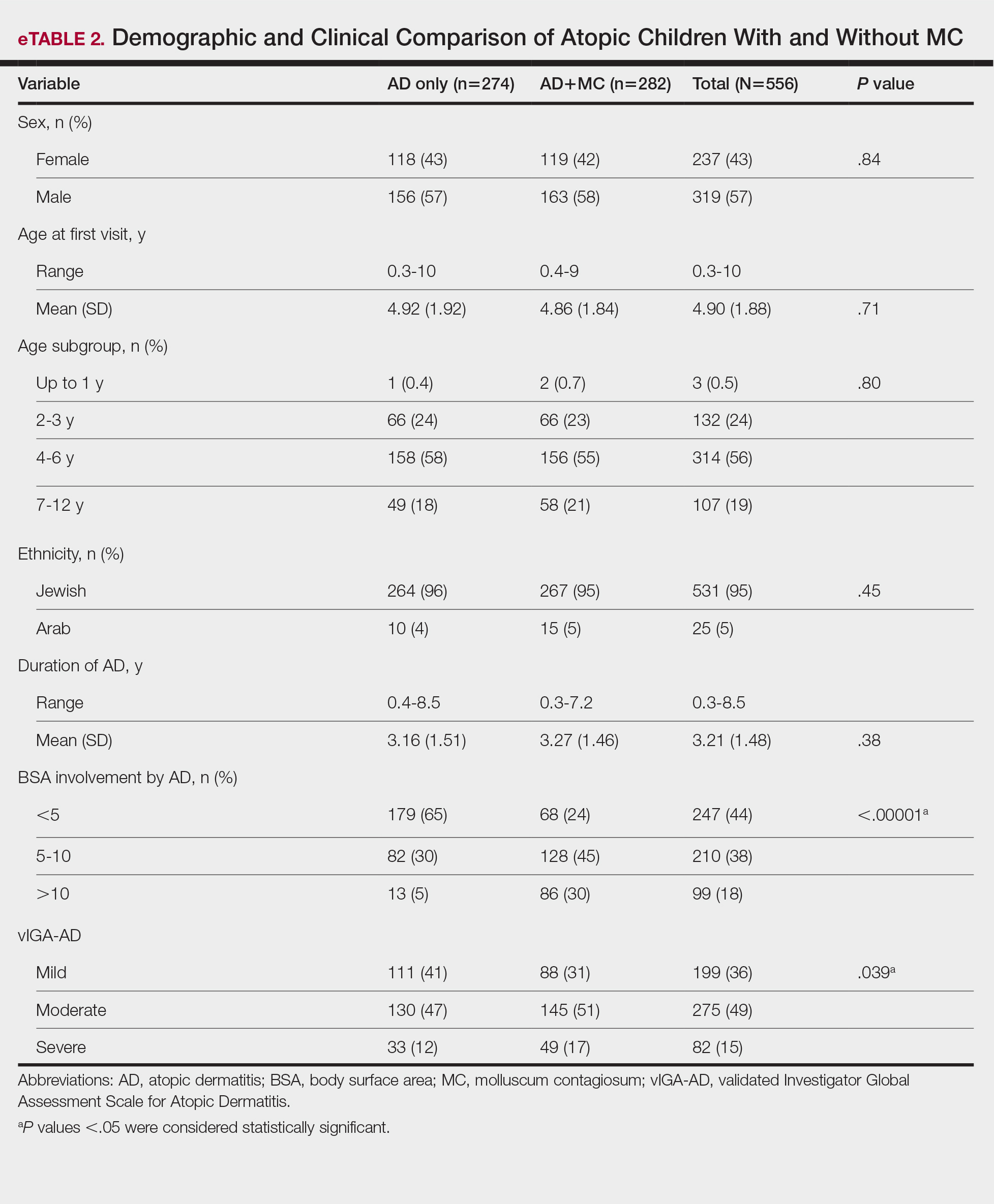

Comparison of Atopic Children With and Without MC—Sex, age distribution, and disease duration showed no differences between atopic patients with and without MC. Atopic patients with MC exhibited greater body surface area involvement and higher validated Investigator Global Assessment Scale for Atopic Dermatitis scores compared to atopic patients without MC (eTable 2).

Comment

This study examined the relationship between MC and AD in pediatric patients, revealing a notable correlation and yielding valuable epidemiologic and clinical insights. Consistent with previous research, our study demonstrated a high prevalence of AD in children with MC.2,6,7,16-21 Previous studies indicated AD rates of 13% to 43% in pediatric patients with MC, whereas our study found a higher prevalence (84%), signifying a substantial majority of patients with MC in our cohort had AD. This discrepancy arises from factors such as demographic, genetic, and environmental differences, along with differences in access to medical care, referral practices, and diagnostic approaches across health care systems.14

Our temporal analysis of MC and AD diagnoses offers important insights. In the majority (72% [203/282]) of cases, the diagnosis of AD preceded MC, supporting previous research suggesting that the underlying pathophysiology of AD heightens susceptibility to MC.15,17-20 Less frequently, MC was diagnosed before or concurrently with AD, indicating that MC may occasionally trigger or exacerbate milder or undiagnosed AD, as previously proposed.20

A notable finding in our study was the expanded age range for MC onset in patients with AD, encompassing older age groups compared to patients with MC as their sole diagnosis, possibly due to persistent immune dysregulation. To the best of our knowledge, this specific observation has not been systematically reported or documented in prior cohort studies. Visible skin lesions of MC may have a psychological impact on patients, influencing self-consciousness and causing embarrassment and emotional distress. This may be more pronounced in older children, who are more aware of their appearance and social perceptions.23-25 These considerations should play a role in the management of MC.

Our study revealed that children with AD and MC displayed higher lesion counts, increased local inflammatory responses, and a more protracted resolution period compared to nonatopic children. In more than 50% of children with AD, MC took more than 1 year for resolution, whereas the majority of those without AD achieved resolution within 1 year. These findings may be attributed to AD-related immune dysregulation, influencing the natural course of MC. Consequently, it suggests that while nonatopic children with MC usually are managed through observation, atopic patients may benefit from an intervention-oriented approach.

Comparing atopic patients with and without MC showed a heightened occurrence of severe and extensive AD among those with concurrent MC. Several factors could contribute to this observation. On one hand, there could be a direct association between the extent and severity of AD, leading to an elevated susceptibility to MC. Conversely, MC might exacerbate immunologic dysregulation and intensify skin inflammation in atopic individuals.20 Additionally, itching related to both disorders may exacerbate inflammation and compromise the epidermal barrier, facilitating the spread of MC. This interplay suggests that each condition exacerbates the other in a self-reinforcing cycle. The importance of patient and caregiver education is underscored by recognizing these interactions. To manage both conditions effectively, health care providers should counsel patients and caregivers on maintaining proper skin care practices such as gentle cleansing with mild, fragrance-free products, regular moisturization, and avoidance of irritants, encourage them to avoid scratching, and recommend adopting an active treatment approach.

Our study had notable strengths. Firstly, a substantial sample size enhanced the statistical reliability of our findings. Additionally, valuable insights into the epidemiology and clinical aspects of AD and MC were obtained by utilizing real-world data from an outpatient dermatology practice. In our study, clinical evaluations covered body surface area involvement and disease severity for AD while also assessing lesion counts and the presence of inflammatory lesions for MC. This comprehensive approach facilitated a thorough analysis of both conditions. The extended data collection period not only allowed for observation of their clinical course and duration, but also enabled a detailed assessment of their interplay.

Our study also had several limitations. Primarily, its retrospective design relied on the accuracy and comprehensiveness of medical records, which may have introduced bias. The exclusion of some patients due to incomplete data further increased the potential for selection bias. Additionally, this study was conducted in a single outpatient dermatology practice in Israel, resulting in a study population composed predominantly of Jewish patients (94%), with a minority (6%) of Arab patients. Other ethnic groups, including Black, Asian, and Hispanic populations, were not represented. This reflects the country’s demographic composition rather than an intentional selection bias. However, the limited ethnic diversity reduces the generalizability of our findings. Differences in demographics, coding practices, health care utilization (eg, timeliness of seeking care, access to dermatology services), and treatment strategies also may impact the observed prevalence, clinical characteristics, and patient outcomes. Furthermore, while our study highlighted the potential advantages of a proactive treatment approach for atopic children with MC, it did not evaluate specific treatment protocols. Future research should aim to confirm the most efficacious therapeutic strategies for managing MC in atopic individuals and to include a more diverse population to better understand the applicability of findings across various ethnic groups.

Conclusion

Our study found a high prevalence of AD in children with MC and a strong bidirectional relationship between these conditions. Pediatric patients with AD display a broader age range for MC, greater lesion burden, increased local inflammatory responses, prolonged resolution times, and more extensive and severe AD.

Recognizing the interplay between MC and AD is crucial, highlighting the importance of health care providers educating patients and caregivers. Emphasizing skin hygiene, discouraging scratching, and implementing proactive treatment approaches can enhance the outcomes of both conditions. Further research into the underlying mechanisms of this association and effective therapeutic strategies for MC in atopic individuals is warranted.

Acknowledgments—The authors thank Zvi Segal, MD (Tel Hashomer, Israel) for his insightful contribution to the statistical analysis of the results. We would like to express our appreciation to the dedicated team of the dermatology practice in Netanya for the support throughout the performance of the study. Additionally, we thank all study participants and their parents for their participation and contribution to our research.

- Han H, Smythe C, Yousefian F, et al. Molluscum contagiosum virus evasion of immune surveillance: a review. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22182-189.

- Dohil MA, Lin P, Lee J, et al. The epidemiology of molluscum contagiosum in children. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;54:47-54.

- Silverberg NB. Pediatric molluscum: an update. Cutis. 2019;104:301-305;E1;E2.

- Forbat E, Al-Niaimi F, Ali FR. Molluscum contagiosum: review and update on management. Pediatr Dermatol. 2017;34:504-515.

- Olsen JR, Gallacher J, Piguet V, et al. Epidemiology of molluscum contagiosum in children: a systematic review. Fam Pract. 2014;31:130-136.

- Kakourou T, Zachariades A, Anastasiou T, et al. Molluscum contagiosum in Greek children: a case series. Int J Dermatol. 2005;44:221-223.

- Osio A, Deslandes E, Saada V, et al. Clinical characteristics of molluscum contagiosum in children in a private dermatology practice in the greater Paris area, France: a prospective study in 661 patients. Dermatology. 2011;222:314-320.

- Hebert AA, Bhatia N, Del Rosso JQ. Molluscum contagiosum: epidemiology, considerations, treatment options, and therapeutic gaps. J Clin Aesthet Dermatol. 2023;16(8 Suppl 1):S4-S11.

- Chao YC, Ko MJ, Tsai WC, et al. Comparative efficacy of treatments for molluscum contagiosum: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2023;21:587-597.

- Garg N, Silverberg JI. Epidemiology of childhood atopic dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33:281-288.

- Hale G, Davies E, Grindlay DJC, et al. What’s new in atopic eczema? an analysis of systematic reviews published in 2017. part 2: epidemiology, etiology, and risk factors. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2019;44:868-873.

- Tracy A, Bhatti S, Eichenfield LF. Update on pediatric atopic dermatitis. Cutis. 2020;106:143-146.

- Langan SM, Irvine AD, Weidinger S. Atopic dermatitis. Lancet. 2020;396:345-360.

- Silverberg JI. Public health burden and epidemiology of atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Clin. 2017;35:283-289.

- Manti S, Amorini M, Cuppari C, et al. Filaggrin mutations and molluscum contagiosum skin infection in patients with atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119446-451.

- Seize M, Ianhez M, Cestari S. A study of the correlation between molluscum contagiosum and atopic dermatitis in children. An Bras Dermatol. 2011;86:663-668.

- Ren Z, Silverberg JI. Association of atopic dermatitis with bacterial, fungal, viral, and sexually transmitted skin infections. Dermatitis. 2020;31:157-164.

- Olsen JR, Piguet V, Gallacher J, et al. Molluscum contagiosum and associations with atopic eczema in children: a retrospective longitudinal study in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66:E53-E58.

- Han JH, Yoon JW, Yook HJ, et al. Evaluation of atopic dermatitis and cutaneous infectious disorders using sequential pattern mining: a nationwide population-based cohort study. J Clin Med. 2022;11:3422.

- Silverberg NB. Molluscum contagiosum virus infection can trigger atopic dermatitis disease onset or flare. Cutis. 2018;102:191-194.

- Hayashida S, Furusho N, Uchi H, et al. Are lifetime prevalence of impetigo, molluscum and herpes infection really increased in children having atopic dermatitis? J Dermatol Sci. 2010;60:173-178.

- Simpson E, Bissonnette R, Eichenfield LF, et al. The Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis (vIGA-AD): the development and reliability testing of a novel clinical outcome measurement instrument for the severity of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83:839-846.

- Olsen JR, Gallacher J, Finlay AY, et al. Time to resolution and effect on quality of life of molluscum contagiosum in children in the UK: a prospective community cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015;15:190-195.

- Ðurovic´ MR, Jankovic´ J, Spiric´ VT, et al. Does age influence the quality of life in children with atopic dermatitis? PLoS One. 2019;14:E0224618.

- Chernyshov PV. Stigmatization and self-perception in children with atopic dermatitis. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2016;9:159-166.

Molluscum contagiosum (MC), which is caused by a DNA virus in the Poxviridae family, is a common viral skin infection that primarily affects children.1-4 The reported incidence and prevalence of MC exhibit notable geographic variation. Worldwide, annual incidence rates per 1000 individuals range from 3.1 to 25, and prevalence ranges from 0.27% to 34.6%.2-7

Molluscum contagiosum is diagnosed clinically and typically manifests as smooth, flesh-colored papules measuring 2 to 6 mm in diameter with central umbilication. It can manifest as a single lesion or multiple clustered lesions, or in a disseminated pattern. The primary mode of transmission is through contact with skin, lesions, or contaminated personal items, or via self-inoculation. The majority of cases are asymptomatic, but in some patients, MC may be associated with pruritus, tenderness, erythema, or irritation. When present, secondary bacterial infections can cause localized inflammation and pain.1,3,4 The pathogenesis hinges on MC virus replication within keratinocytes, disrupting cellular differentiation and keratinization. The virus persists in the host by influencing the immune response through various mechanisms, including interference with signaling pathways, apoptosis inhibition, and antigen presentation disruption.3,4

Molluscum contagiosum typically follows a self-limiting trajectory, resolving over several months to 2 years.3,4 The resolution timeframe is intricately linked to variables such as the patient’s immune profile, lesion burden, and treatment approach. For symptomatic lesions, a variety of treatment options have been described, including physical ablation (eg, cryotherapy, curettage) and topical agents such as potassium hydroxide, cantharidin, imiquimod, and salicylic acid.3,4,8,9

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common chronic relapsing inflammatory skin disorder. In the United States, its prevalence ranges from 15% to 30% in children and from 2% to 10% in adults, with ongoing evidence of a growing global incidence.10-14 While AD can emerge at any age, typical onset is during early childhood. The clinical manifestation of AD includes a spectrum of eczematous features, often accompanied by persistent itching. The pathogenesis is multifactorial, involving a complex interplay of genetic, immunologic, and environmental factors. Key contributors to this multifaceted process encompass a compromised epidermal barrier, alterations in the skin microbiome, and an immune dysregulation promoting a type 2 immune response. Epidermal barrier dysfunction can be attributed to various factors, including diminished ceramide production, altered lipid composition, the release of inflammatory mediators, and mechanical damage from the persistent itch-scratch cycle.10-13,15 These factors or their interplay may enhance the susceptibility of patients with AD to infections.

Several studies conducted across various geographic regions examining the relationship between MC and AD have reported variable findings.2,6,7,16-21 Published studies have reported a prevalence of AD in children with MC ranging from 13.2% to 43%.2,6,7,16-21 Although some studies suggest a higher rate of atopy in patients with MC, not all research has confirmed this association.16,21 Dohil et al2 reported a greater number of MC lesions in children with AD than those without an atopic background. Silverberg20 reported that in 10% (5/50) of children with MC, the onset of AD was triggered, and in 22% (11/50) MC was associated with flares of pre-existing AD.

In this study, we aimed to assess MC infection rates in children with AD, analyze the epidemiologic aspects and severity differences between atopic children with and without MC infection, and compare data from atopic and nonatopic children with MC.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, we analyzed the medical records of pediatric patients diagnosed with MC, AD, or both conditions at an outpatient dermatology practice in Netanya, HaSharon, Israel, from September 2013 to August 2022. Data were collected from the electronic medical records and included patient demographics, the clinical presentation of MC and/or AD at diagnosis, and the duration of both conditions. Only patients with complete data and at least 6 months of follow-up were included. Key epidemiologic characteristics assessed included patient sex, age at the initial visit, and age at the onset of MC and/or AD. Diagnoses of MC and AD were established through clinical examinations conducted by dermatologists. The clinical evaluation of AD encompassed the assessment of body surface area involvement (categorized as <5%, 5%-10%, or >10%). Atopic dermatitis severity was classified as mild, moderate, or severe using the validated Investigator Global Assessment Scale for Atopic Dermatitis.22 Clinical evaluation of MC included assessment of the number of lesions (categorized as ≤4, 5-9, or ≥10), presence of inflammatory lesions, and resolution times for individual lesions (categorized as <1 week, several weeks, or unknown), as well as the overall resolution time for all lesions (categorized as <6 months, 6-12 months, 13-18 months, or >18 months). The temporal relationship between the appearance of MC and AD also was assessed.

Statistical Analysis—Numbers and percentages were used for categorical variables. Continuous variables were represented by mean and standard deviation. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test, and continuous variables between groups were compared using the Student t test. All statistical tests were 2-sided, with statistical significance defined as P≤.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 28 (IBM).

Results

Study Population—A total of 610 children were included in the study; 263 (43%) were female and 347 (57%) were male. The patients ranged in age from 4 months to 10 years, with a mean (SD) age of 4.87 (1.82) years. Five hundred fifty-six (91%) patients had AD, and 336 (55%) had MC. Within this cohort, 274 (45%) children had AD only, 54 (9%) had MC only, and 282 (46%) had both AD and MC. Regarding the temporal sequence, among the 282 children who had both AD and MC, AD preceded MC in 203 (72%) cases, both conditions were diagnosed concomitantly in 43 (15%) cases, and MC preceded AD in 36 (13%) cases. For cases in which the MC diagnosis followed the diagnosis of AD, the mean (SD) time between each diagnosis was 3.17 (1.5) years.

Comparison of Atopic and Nonatopic Children With MC—Although a higher proportion of males were diagnosed with MC (with or without concurrent AD), the differences in sex distribution between the 2 groups did not reach statistical significance. Among all children with MC, the majority (81.5% [274/336]) were aged 1 to 6 years at presentation. Patients with MC as their sole diagnosis had a similar mean age compared with those with concurrent AD. However, a detailed age subgroup analysis revealed a notable distinction: in the group with MC as the sole diagnosis, the majority (95% [51/54]) were younger than 7 years. In contrast, in the combined MC and AD group, MC manifested across a wider age range, with 21% (58/282) of patients being older than 7 years. In MC cases associated with AD, a notably higher lesion count and increased local inflammatory response were observed compared to those without AD. The time for complete resolution of all MC lesions was substantially prolonged in patients with comorbid AD. Specifically, 93% (50/54) of patients with MC without comorbid AD achieved full resolution within 1 year, whereas 52% (146/282) of patients with comorbid AD required more than 1 year for resolution (eTable 1).

Comparison of Atopic Children With and Without MC—Sex, age distribution, and disease duration showed no differences between atopic patients with and without MC. Atopic patients with MC exhibited greater body surface area involvement and higher validated Investigator Global Assessment Scale for Atopic Dermatitis scores compared to atopic patients without MC (eTable 2).

Comment

This study examined the relationship between MC and AD in pediatric patients, revealing a notable correlation and yielding valuable epidemiologic and clinical insights. Consistent with previous research, our study demonstrated a high prevalence of AD in children with MC.2,6,7,16-21 Previous studies indicated AD rates of 13% to 43% in pediatric patients with MC, whereas our study found a higher prevalence (84%), signifying a substantial majority of patients with MC in our cohort had AD. This discrepancy arises from factors such as demographic, genetic, and environmental differences, along with differences in access to medical care, referral practices, and diagnostic approaches across health care systems.14

Our temporal analysis of MC and AD diagnoses offers important insights. In the majority (72% [203/282]) of cases, the diagnosis of AD preceded MC, supporting previous research suggesting that the underlying pathophysiology of AD heightens susceptibility to MC.15,17-20 Less frequently, MC was diagnosed before or concurrently with AD, indicating that MC may occasionally trigger or exacerbate milder or undiagnosed AD, as previously proposed.20

A notable finding in our study was the expanded age range for MC onset in patients with AD, encompassing older age groups compared to patients with MC as their sole diagnosis, possibly due to persistent immune dysregulation. To the best of our knowledge, this specific observation has not been systematically reported or documented in prior cohort studies. Visible skin lesions of MC may have a psychological impact on patients, influencing self-consciousness and causing embarrassment and emotional distress. This may be more pronounced in older children, who are more aware of their appearance and social perceptions.23-25 These considerations should play a role in the management of MC.

Our study revealed that children with AD and MC displayed higher lesion counts, increased local inflammatory responses, and a more protracted resolution period compared to nonatopic children. In more than 50% of children with AD, MC took more than 1 year for resolution, whereas the majority of those without AD achieved resolution within 1 year. These findings may be attributed to AD-related immune dysregulation, influencing the natural course of MC. Consequently, it suggests that while nonatopic children with MC usually are managed through observation, atopic patients may benefit from an intervention-oriented approach.

Comparing atopic patients with and without MC showed a heightened occurrence of severe and extensive AD among those with concurrent MC. Several factors could contribute to this observation. On one hand, there could be a direct association between the extent and severity of AD, leading to an elevated susceptibility to MC. Conversely, MC might exacerbate immunologic dysregulation and intensify skin inflammation in atopic individuals.20 Additionally, itching related to both disorders may exacerbate inflammation and compromise the epidermal barrier, facilitating the spread of MC. This interplay suggests that each condition exacerbates the other in a self-reinforcing cycle. The importance of patient and caregiver education is underscored by recognizing these interactions. To manage both conditions effectively, health care providers should counsel patients and caregivers on maintaining proper skin care practices such as gentle cleansing with mild, fragrance-free products, regular moisturization, and avoidance of irritants, encourage them to avoid scratching, and recommend adopting an active treatment approach.

Our study had notable strengths. Firstly, a substantial sample size enhanced the statistical reliability of our findings. Additionally, valuable insights into the epidemiology and clinical aspects of AD and MC were obtained by utilizing real-world data from an outpatient dermatology practice. In our study, clinical evaluations covered body surface area involvement and disease severity for AD while also assessing lesion counts and the presence of inflammatory lesions for MC. This comprehensive approach facilitated a thorough analysis of both conditions. The extended data collection period not only allowed for observation of their clinical course and duration, but also enabled a detailed assessment of their interplay.

Our study also had several limitations. Primarily, its retrospective design relied on the accuracy and comprehensiveness of medical records, which may have introduced bias. The exclusion of some patients due to incomplete data further increased the potential for selection bias. Additionally, this study was conducted in a single outpatient dermatology practice in Israel, resulting in a study population composed predominantly of Jewish patients (94%), with a minority (6%) of Arab patients. Other ethnic groups, including Black, Asian, and Hispanic populations, were not represented. This reflects the country’s demographic composition rather than an intentional selection bias. However, the limited ethnic diversity reduces the generalizability of our findings. Differences in demographics, coding practices, health care utilization (eg, timeliness of seeking care, access to dermatology services), and treatment strategies also may impact the observed prevalence, clinical characteristics, and patient outcomes. Furthermore, while our study highlighted the potential advantages of a proactive treatment approach for atopic children with MC, it did not evaluate specific treatment protocols. Future research should aim to confirm the most efficacious therapeutic strategies for managing MC in atopic individuals and to include a more diverse population to better understand the applicability of findings across various ethnic groups.

Conclusion

Our study found a high prevalence of AD in children with MC and a strong bidirectional relationship between these conditions. Pediatric patients with AD display a broader age range for MC, greater lesion burden, increased local inflammatory responses, prolonged resolution times, and more extensive and severe AD.

Recognizing the interplay between MC and AD is crucial, highlighting the importance of health care providers educating patients and caregivers. Emphasizing skin hygiene, discouraging scratching, and implementing proactive treatment approaches can enhance the outcomes of both conditions. Further research into the underlying mechanisms of this association and effective therapeutic strategies for MC in atopic individuals is warranted.

Acknowledgments—The authors thank Zvi Segal, MD (Tel Hashomer, Israel) for his insightful contribution to the statistical analysis of the results. We would like to express our appreciation to the dedicated team of the dermatology practice in Netanya for the support throughout the performance of the study. Additionally, we thank all study participants and their parents for their participation and contribution to our research.

Molluscum contagiosum (MC), which is caused by a DNA virus in the Poxviridae family, is a common viral skin infection that primarily affects children.1-4 The reported incidence and prevalence of MC exhibit notable geographic variation. Worldwide, annual incidence rates per 1000 individuals range from 3.1 to 25, and prevalence ranges from 0.27% to 34.6%.2-7

Molluscum contagiosum is diagnosed clinically and typically manifests as smooth, flesh-colored papules measuring 2 to 6 mm in diameter with central umbilication. It can manifest as a single lesion or multiple clustered lesions, or in a disseminated pattern. The primary mode of transmission is through contact with skin, lesions, or contaminated personal items, or via self-inoculation. The majority of cases are asymptomatic, but in some patients, MC may be associated with pruritus, tenderness, erythema, or irritation. When present, secondary bacterial infections can cause localized inflammation and pain.1,3,4 The pathogenesis hinges on MC virus replication within keratinocytes, disrupting cellular differentiation and keratinization. The virus persists in the host by influencing the immune response through various mechanisms, including interference with signaling pathways, apoptosis inhibition, and antigen presentation disruption.3,4

Molluscum contagiosum typically follows a self-limiting trajectory, resolving over several months to 2 years.3,4 The resolution timeframe is intricately linked to variables such as the patient’s immune profile, lesion burden, and treatment approach. For symptomatic lesions, a variety of treatment options have been described, including physical ablation (eg, cryotherapy, curettage) and topical agents such as potassium hydroxide, cantharidin, imiquimod, and salicylic acid.3,4,8,9

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common chronic relapsing inflammatory skin disorder. In the United States, its prevalence ranges from 15% to 30% in children and from 2% to 10% in adults, with ongoing evidence of a growing global incidence.10-14 While AD can emerge at any age, typical onset is during early childhood. The clinical manifestation of AD includes a spectrum of eczematous features, often accompanied by persistent itching. The pathogenesis is multifactorial, involving a complex interplay of genetic, immunologic, and environmental factors. Key contributors to this multifaceted process encompass a compromised epidermal barrier, alterations in the skin microbiome, and an immune dysregulation promoting a type 2 immune response. Epidermal barrier dysfunction can be attributed to various factors, including diminished ceramide production, altered lipid composition, the release of inflammatory mediators, and mechanical damage from the persistent itch-scratch cycle.10-13,15 These factors or their interplay may enhance the susceptibility of patients with AD to infections.

Several studies conducted across various geographic regions examining the relationship between MC and AD have reported variable findings.2,6,7,16-21 Published studies have reported a prevalence of AD in children with MC ranging from 13.2% to 43%.2,6,7,16-21 Although some studies suggest a higher rate of atopy in patients with MC, not all research has confirmed this association.16,21 Dohil et al2 reported a greater number of MC lesions in children with AD than those without an atopic background. Silverberg20 reported that in 10% (5/50) of children with MC, the onset of AD was triggered, and in 22% (11/50) MC was associated with flares of pre-existing AD.

In this study, we aimed to assess MC infection rates in children with AD, analyze the epidemiologic aspects and severity differences between atopic children with and without MC infection, and compare data from atopic and nonatopic children with MC.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, we analyzed the medical records of pediatric patients diagnosed with MC, AD, or both conditions at an outpatient dermatology practice in Netanya, HaSharon, Israel, from September 2013 to August 2022. Data were collected from the electronic medical records and included patient demographics, the clinical presentation of MC and/or AD at diagnosis, and the duration of both conditions. Only patients with complete data and at least 6 months of follow-up were included. Key epidemiologic characteristics assessed included patient sex, age at the initial visit, and age at the onset of MC and/or AD. Diagnoses of MC and AD were established through clinical examinations conducted by dermatologists. The clinical evaluation of AD encompassed the assessment of body surface area involvement (categorized as <5%, 5%-10%, or >10%). Atopic dermatitis severity was classified as mild, moderate, or severe using the validated Investigator Global Assessment Scale for Atopic Dermatitis.22 Clinical evaluation of MC included assessment of the number of lesions (categorized as ≤4, 5-9, or ≥10), presence of inflammatory lesions, and resolution times for individual lesions (categorized as <1 week, several weeks, or unknown), as well as the overall resolution time for all lesions (categorized as <6 months, 6-12 months, 13-18 months, or >18 months). The temporal relationship between the appearance of MC and AD also was assessed.

Statistical Analysis—Numbers and percentages were used for categorical variables. Continuous variables were represented by mean and standard deviation. Categorical variables were compared using the χ2 test, and continuous variables between groups were compared using the Student t test. All statistical tests were 2-sided, with statistical significance defined as P≤.05. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 28 (IBM).

Results

Study Population—A total of 610 children were included in the study; 263 (43%) were female and 347 (57%) were male. The patients ranged in age from 4 months to 10 years, with a mean (SD) age of 4.87 (1.82) years. Five hundred fifty-six (91%) patients had AD, and 336 (55%) had MC. Within this cohort, 274 (45%) children had AD only, 54 (9%) had MC only, and 282 (46%) had both AD and MC. Regarding the temporal sequence, among the 282 children who had both AD and MC, AD preceded MC in 203 (72%) cases, both conditions were diagnosed concomitantly in 43 (15%) cases, and MC preceded AD in 36 (13%) cases. For cases in which the MC diagnosis followed the diagnosis of AD, the mean (SD) time between each diagnosis was 3.17 (1.5) years.

Comparison of Atopic and Nonatopic Children With MC—Although a higher proportion of males were diagnosed with MC (with or without concurrent AD), the differences in sex distribution between the 2 groups did not reach statistical significance. Among all children with MC, the majority (81.5% [274/336]) were aged 1 to 6 years at presentation. Patients with MC as their sole diagnosis had a similar mean age compared with those with concurrent AD. However, a detailed age subgroup analysis revealed a notable distinction: in the group with MC as the sole diagnosis, the majority (95% [51/54]) were younger than 7 years. In contrast, in the combined MC and AD group, MC manifested across a wider age range, with 21% (58/282) of patients being older than 7 years. In MC cases associated with AD, a notably higher lesion count and increased local inflammatory response were observed compared to those without AD. The time for complete resolution of all MC lesions was substantially prolonged in patients with comorbid AD. Specifically, 93% (50/54) of patients with MC without comorbid AD achieved full resolution within 1 year, whereas 52% (146/282) of patients with comorbid AD required more than 1 year for resolution (eTable 1).

Comparison of Atopic Children With and Without MC—Sex, age distribution, and disease duration showed no differences between atopic patients with and without MC. Atopic patients with MC exhibited greater body surface area involvement and higher validated Investigator Global Assessment Scale for Atopic Dermatitis scores compared to atopic patients without MC (eTable 2).

Comment

This study examined the relationship between MC and AD in pediatric patients, revealing a notable correlation and yielding valuable epidemiologic and clinical insights. Consistent with previous research, our study demonstrated a high prevalence of AD in children with MC.2,6,7,16-21 Previous studies indicated AD rates of 13% to 43% in pediatric patients with MC, whereas our study found a higher prevalence (84%), signifying a substantial majority of patients with MC in our cohort had AD. This discrepancy arises from factors such as demographic, genetic, and environmental differences, along with differences in access to medical care, referral practices, and diagnostic approaches across health care systems.14

Our temporal analysis of MC and AD diagnoses offers important insights. In the majority (72% [203/282]) of cases, the diagnosis of AD preceded MC, supporting previous research suggesting that the underlying pathophysiology of AD heightens susceptibility to MC.15,17-20 Less frequently, MC was diagnosed before or concurrently with AD, indicating that MC may occasionally trigger or exacerbate milder or undiagnosed AD, as previously proposed.20

A notable finding in our study was the expanded age range for MC onset in patients with AD, encompassing older age groups compared to patients with MC as their sole diagnosis, possibly due to persistent immune dysregulation. To the best of our knowledge, this specific observation has not been systematically reported or documented in prior cohort studies. Visible skin lesions of MC may have a psychological impact on patients, influencing self-consciousness and causing embarrassment and emotional distress. This may be more pronounced in older children, who are more aware of their appearance and social perceptions.23-25 These considerations should play a role in the management of MC.