User login

As psychiatrists, we do not often encounter situations in which we need to inform patients and their families that they have a life-threatening diagnosis. Nonetheless, on the rare occasions when we work with such patients, new psychiatrists may find their clinical skills challenged. Breaking bad news remains an aspect of clinical training that is often overlooked by medical schools.

Here I present a case that illustrates the challenges residents and medical students face when they need to deliver bad news and review the current literature on how to present patients with this type of information.

Case

Bizarre behavior, difficult diagnosis

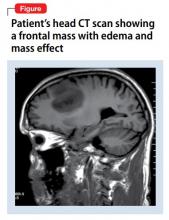

Mr. C, age 59, with a 1-year history of major depressive disorder, was brought to the emergency department by his wife for worsening depression and disorganized behavior over the course of 3 weeks. Mr. C had obsessive thoughts about arranging things in symmetrical patterns, difficulty sleeping, loss of appetite, and anhedonia. His wife reported that his bizarre, disorganized behavior further intensified in the previous week; he was urinating on the rug, rubbing his genitals against the bathroom counter, staring into space without moving for prolonged periods of time, and arranging his food in symmetrical patterns. Mr. C has no reported substance use or suicidal or homicidal ideation.

Strategies for delivering bad news

Initially, I struggled when I realized I would have to deliver the news of this potentially life-threatening diagnosis to the patient and his wife because I had not received any training on how to do so. However, I took time to look into the literature and used the skills that we as psychiatrists have, including empathy, listening, and validation. My experience with Mr. C and his family made me realize that delivering bad news with empathy and being involved in the struggle that follows can make a significant difference to their suffering.

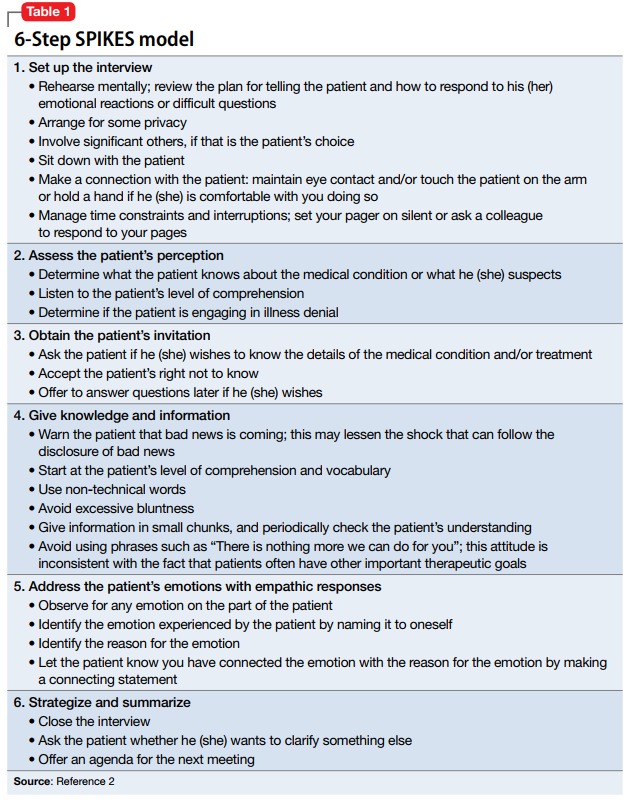

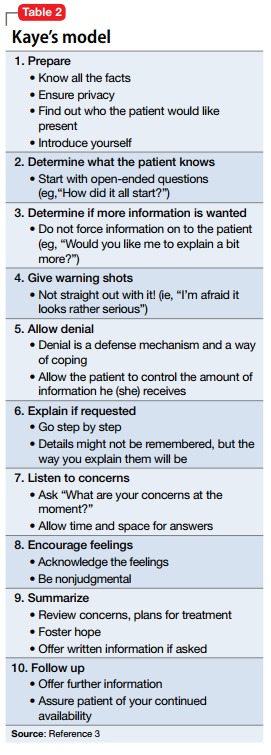

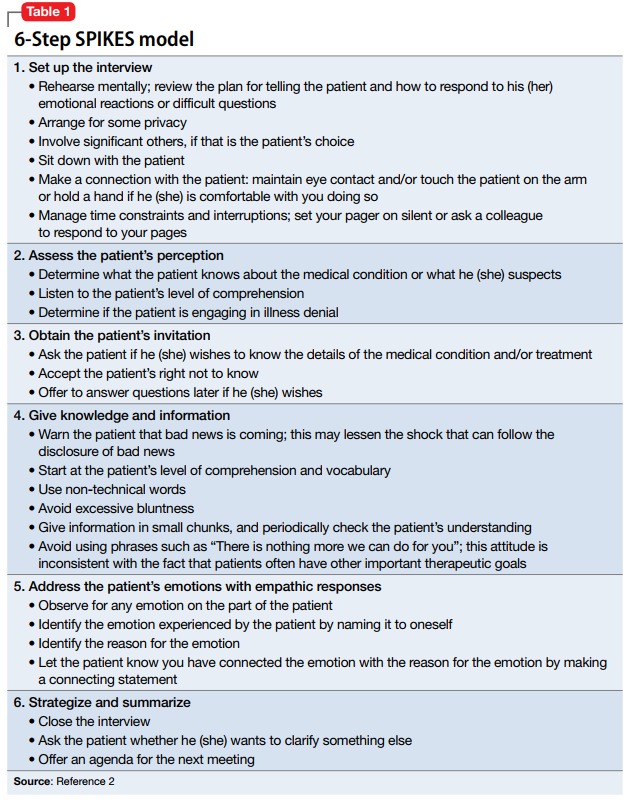

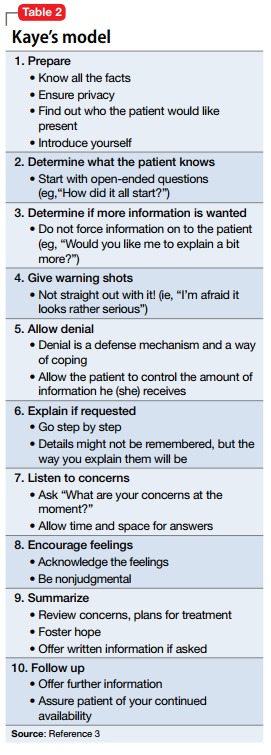

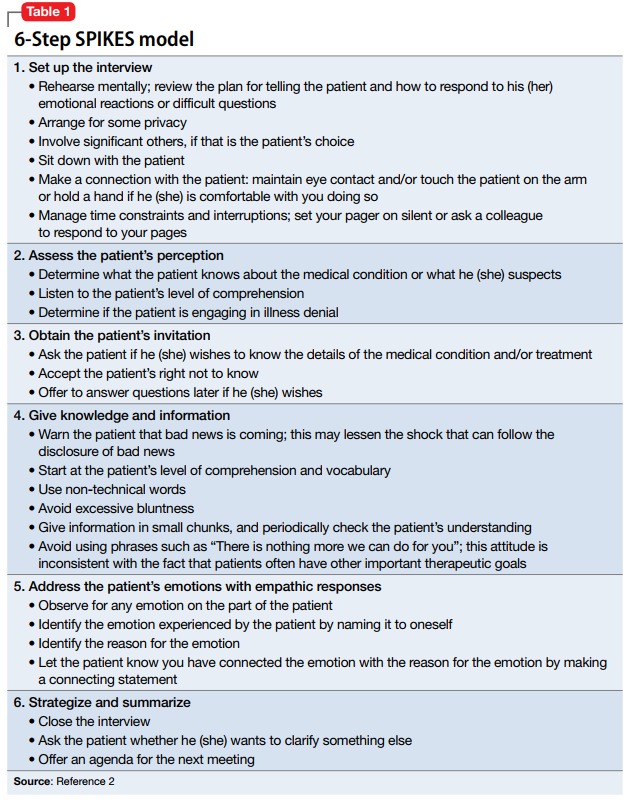

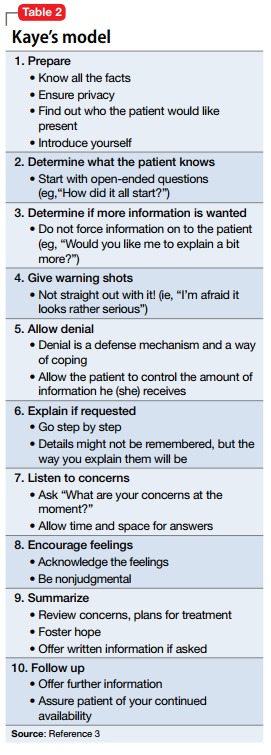

There are various models and techniques for breaking bad news to patients. Two of the most commonly used models in the oncology setting are the SPIKES (Set up, Perception, Interview, Knowledge, Emotions, Strategize and Summarize) model (Table 12) and Kaye’s model (Table 23).

A clinician’s attitude and communication skills play a crucial role in how well patients and family members cope when they receive bad news. When delivering bad news:

- Choose a setting with adequate privacy, use simple language that distills medical facts into appreciable pieces of information, and give the recipients ample space and time to process the implications. Doing so will foster better understanding and facilitate their acceptance of the bad news.

- Although physicians can rarely appreciate the patient’s feelings at a personal level, make every effort to validate their thoughts and offer emotional support. In such situations, it is often appropriate to move closer to the recipient and make brief physical gestures, such as laying a hand on the shoulder, which might comfort them.

- In the aftermath of such encounters, it is important to remain active in the patient’s emotional journey and available for further clarification, which can mitigate uncertainties and facilitate the difficult process of coming to terms with new realities.4,5

1. Munjal S, Pahlajani S, Baxi A, et al. Delayed diagnosis of glioblastoma multiforme presenting with atypical psychiatric symptoms. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2016;18(6). doi: 10.4088/PCC.16l01972.

2. Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, et al. SPIKES-a six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302-311.

3. Kaye P. Breaking bad news: a 10 step approach. Northampton, MA: EPL Publications; 1995.

4. Chaturvedi SK, Chandra PS. Breaking bad news-issues important for psychiatrists. Asian J Psychiatr. 2010;3(2):87-89.

5. VandeKieft GK. Breaking bad news. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64(12):1975-1978.

As psychiatrists, we do not often encounter situations in which we need to inform patients and their families that they have a life-threatening diagnosis. Nonetheless, on the rare occasions when we work with such patients, new psychiatrists may find their clinical skills challenged. Breaking bad news remains an aspect of clinical training that is often overlooked by medical schools.

Here I present a case that illustrates the challenges residents and medical students face when they need to deliver bad news and review the current literature on how to present patients with this type of information.

Case

Bizarre behavior, difficult diagnosis

Mr. C, age 59, with a 1-year history of major depressive disorder, was brought to the emergency department by his wife for worsening depression and disorganized behavior over the course of 3 weeks. Mr. C had obsessive thoughts about arranging things in symmetrical patterns, difficulty sleeping, loss of appetite, and anhedonia. His wife reported that his bizarre, disorganized behavior further intensified in the previous week; he was urinating on the rug, rubbing his genitals against the bathroom counter, staring into space without moving for prolonged periods of time, and arranging his food in symmetrical patterns. Mr. C has no reported substance use or suicidal or homicidal ideation.

Strategies for delivering bad news

Initially, I struggled when I realized I would have to deliver the news of this potentially life-threatening diagnosis to the patient and his wife because I had not received any training on how to do so. However, I took time to look into the literature and used the skills that we as psychiatrists have, including empathy, listening, and validation. My experience with Mr. C and his family made me realize that delivering bad news with empathy and being involved in the struggle that follows can make a significant difference to their suffering.

There are various models and techniques for breaking bad news to patients. Two of the most commonly used models in the oncology setting are the SPIKES (Set up, Perception, Interview, Knowledge, Emotions, Strategize and Summarize) model (Table 12) and Kaye’s model (Table 23).

A clinician’s attitude and communication skills play a crucial role in how well patients and family members cope when they receive bad news. When delivering bad news:

- Choose a setting with adequate privacy, use simple language that distills medical facts into appreciable pieces of information, and give the recipients ample space and time to process the implications. Doing so will foster better understanding and facilitate their acceptance of the bad news.

- Although physicians can rarely appreciate the patient’s feelings at a personal level, make every effort to validate their thoughts and offer emotional support. In such situations, it is often appropriate to move closer to the recipient and make brief physical gestures, such as laying a hand on the shoulder, which might comfort them.

- In the aftermath of such encounters, it is important to remain active in the patient’s emotional journey and available for further clarification, which can mitigate uncertainties and facilitate the difficult process of coming to terms with new realities.4,5

As psychiatrists, we do not often encounter situations in which we need to inform patients and their families that they have a life-threatening diagnosis. Nonetheless, on the rare occasions when we work with such patients, new psychiatrists may find their clinical skills challenged. Breaking bad news remains an aspect of clinical training that is often overlooked by medical schools.

Here I present a case that illustrates the challenges residents and medical students face when they need to deliver bad news and review the current literature on how to present patients with this type of information.

Case

Bizarre behavior, difficult diagnosis

Mr. C, age 59, with a 1-year history of major depressive disorder, was brought to the emergency department by his wife for worsening depression and disorganized behavior over the course of 3 weeks. Mr. C had obsessive thoughts about arranging things in symmetrical patterns, difficulty sleeping, loss of appetite, and anhedonia. His wife reported that his bizarre, disorganized behavior further intensified in the previous week; he was urinating on the rug, rubbing his genitals against the bathroom counter, staring into space without moving for prolonged periods of time, and arranging his food in symmetrical patterns. Mr. C has no reported substance use or suicidal or homicidal ideation.

Strategies for delivering bad news

Initially, I struggled when I realized I would have to deliver the news of this potentially life-threatening diagnosis to the patient and his wife because I had not received any training on how to do so. However, I took time to look into the literature and used the skills that we as psychiatrists have, including empathy, listening, and validation. My experience with Mr. C and his family made me realize that delivering bad news with empathy and being involved in the struggle that follows can make a significant difference to their suffering.

There are various models and techniques for breaking bad news to patients. Two of the most commonly used models in the oncology setting are the SPIKES (Set up, Perception, Interview, Knowledge, Emotions, Strategize and Summarize) model (Table 12) and Kaye’s model (Table 23).

A clinician’s attitude and communication skills play a crucial role in how well patients and family members cope when they receive bad news. When delivering bad news:

- Choose a setting with adequate privacy, use simple language that distills medical facts into appreciable pieces of information, and give the recipients ample space and time to process the implications. Doing so will foster better understanding and facilitate their acceptance of the bad news.

- Although physicians can rarely appreciate the patient’s feelings at a personal level, make every effort to validate their thoughts and offer emotional support. In such situations, it is often appropriate to move closer to the recipient and make brief physical gestures, such as laying a hand on the shoulder, which might comfort them.

- In the aftermath of such encounters, it is important to remain active in the patient’s emotional journey and available for further clarification, which can mitigate uncertainties and facilitate the difficult process of coming to terms with new realities.4,5

1. Munjal S, Pahlajani S, Baxi A, et al. Delayed diagnosis of glioblastoma multiforme presenting with atypical psychiatric symptoms. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2016;18(6). doi: 10.4088/PCC.16l01972.

2. Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, et al. SPIKES-a six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302-311.

3. Kaye P. Breaking bad news: a 10 step approach. Northampton, MA: EPL Publications; 1995.

4. Chaturvedi SK, Chandra PS. Breaking bad news-issues important for psychiatrists. Asian J Psychiatr. 2010;3(2):87-89.

5. VandeKieft GK. Breaking bad news. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64(12):1975-1978.

1. Munjal S, Pahlajani S, Baxi A, et al. Delayed diagnosis of glioblastoma multiforme presenting with atypical psychiatric symptoms. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2016;18(6). doi: 10.4088/PCC.16l01972.

2. Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, et al. SPIKES-a six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302-311.

3. Kaye P. Breaking bad news: a 10 step approach. Northampton, MA: EPL Publications; 1995.

4. Chaturvedi SK, Chandra PS. Breaking bad news-issues important for psychiatrists. Asian J Psychiatr. 2010;3(2):87-89.

5. VandeKieft GK. Breaking bad news. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64(12):1975-1978.