User login

Proactive consultation: A new model of care in consultation-liaison psychiatry

During my residency training, I was trained in the standard “reactive” psychiatric consultation model. In this system, I would see consults placed by the primary team after they identified a behavioral issue in a patient. As a trainee, I experienced frequent frustrations working in this model: Consults that are discharge-dependent (“Can you see the patient before he is discharged this morning?”), consults for acute behavioral dysregulation (“The patient is near the elevator, can you come see him ASAP?”), or consults for consequences of poor management of alcohol/benzodiazepine withdrawal (“The patient is confused and trying to leave”).

As a fellow in consultation-liaison (C-L) psychiatry, I was introduced to the “proactive” consultation model, which avoids some of these issues. In this article, which is intended for residents who have not been exposed to this new approach, I explain how the proactive model changes our experience as C-L clinicians.

The Behavioral Intervention Team

At Yale New Haven Hospital, the Behavioral Intervention Team (BIT) is a proactive, multidisciplinary psychiatric consultation service that serves the internal medicine units at the hospital. The team consists of nurse practitioners, nurse liaison specialists, social workers, and psychiatrists. The team identifies and removes behavioral barriers in the care of hospitalized mentally ill patients.

The BIT collaborates closely with the medical team through formal and informal consultation; co-management of behavioral issues; education of medical, nursing, and social work staff; and direct care of complex patients with behavioral disorders. The BIT assists the medical team with transitions to appropriate outpatient and inpatient psychiatric care. The team also manages the relationship with the insurer when a patient requires a stay in a psychiatric unit.

This model has a critical financial benefit in reducing the length of stay, but it also has many other benefits. It focuses on early recognition and treatment, and helps mitigate the effects of mental or substance use disorders on patients’ recovery. BIT members educate their peers regarding management of a multitude of behavioral issues. This fosters extensive informal collaboration (“curbside consultation”), which helps patients who did not receive a formal consult. The model distributes work more rationally among different professional specialists. It yields a relationship with medical teams that is not only more effective, but also more enjoyable. In the BIT model, psychiatrists pick the cases where they feel they can have the most impact, and avoid the cases they feel they cannot have any.1-3

CASE A better approach to alcohol withdrawal

Mr. X, age 56, has a history of alcohol use disorder, hypertension, and coronary artery disease. He’s had multiple past admissions for complicated alcohol withdrawal. He is transferred from a local community hospital, where he had presented with chest pain. His last drink was 2 days prior to admission, and his blood alcohol level is <10 mg/dL.

During Mr. X’s previous hospitalizations, psychiatric consults were performed in the standard reactive model. The primary team initially prescribed an ineffective dosage of benzodiazepines for his alcohol withdrawal. This escalated his withdrawal into delirium tremens, after which psychiatry was involved. Due to this early ineffective management, the patient had a prolonged medical ICU stay and overall stay, experienced increased medical complications, and required increased staff resources because he was extremely agitated.

Continued to: During this hospitalization...

During this hospitalization, Mr. X arrives with similar medical complaints. The nurse practitioner on the BIT service, who screened all admissions each day, examines the prior notes (she finds the team sign-outs to be particularly useful). She suggests a psychiatric consult on Day 1 of the admission, which the primary medical team orders. The BIT nurse practitioner gives apt recommendations of evidence-based management, including a benzodiazepine taper, high-dose thiamine, and psychopharmacologic approaches to severe agitation. The nurse liaison specialist on the service makes behavioral plans for managing agitation, which she communicates to the nurses caring for Mr. X.

Because his withdrawal is managed more promptly, Mr. X’s length of stay is shorter and he does not experience any medical complications. The BIT social worker helps find appropriate aftercare options, including residential treatment and Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, to which the patient agrees.

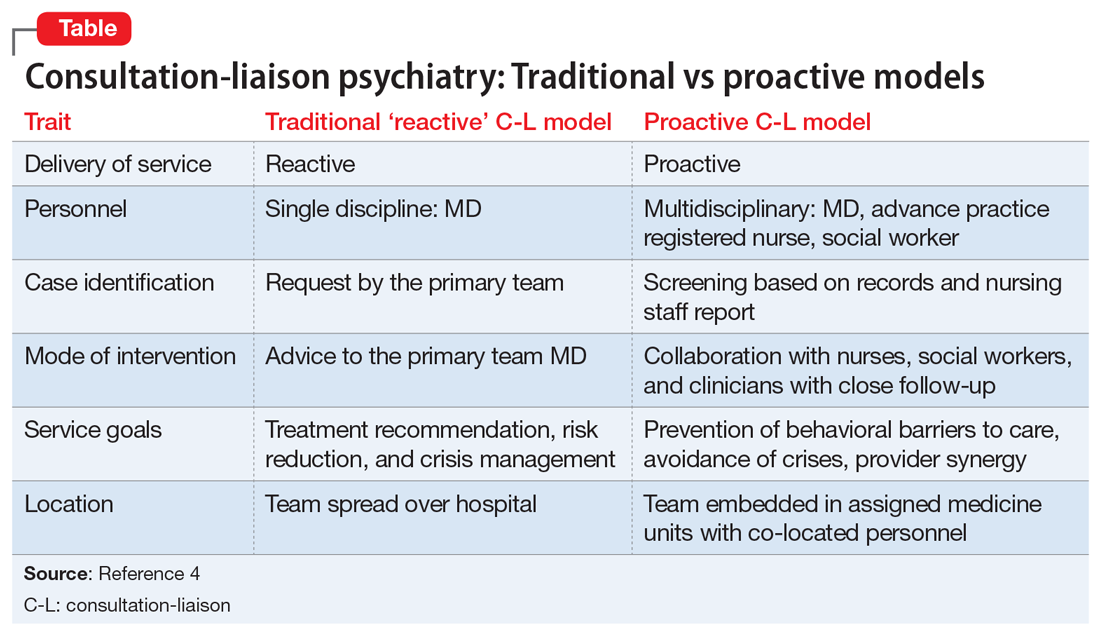

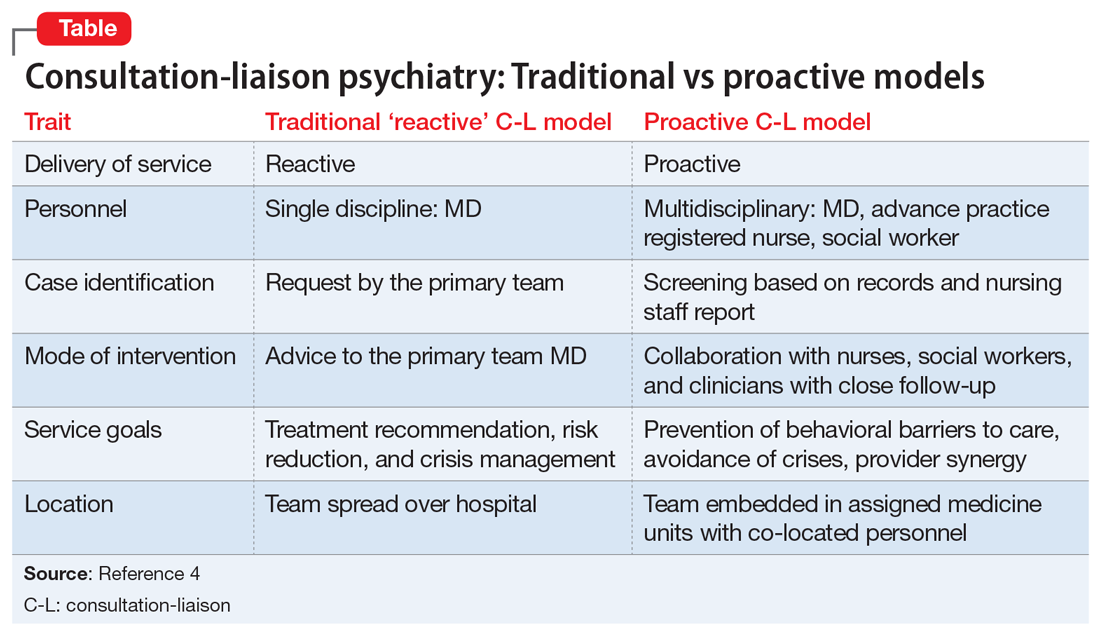

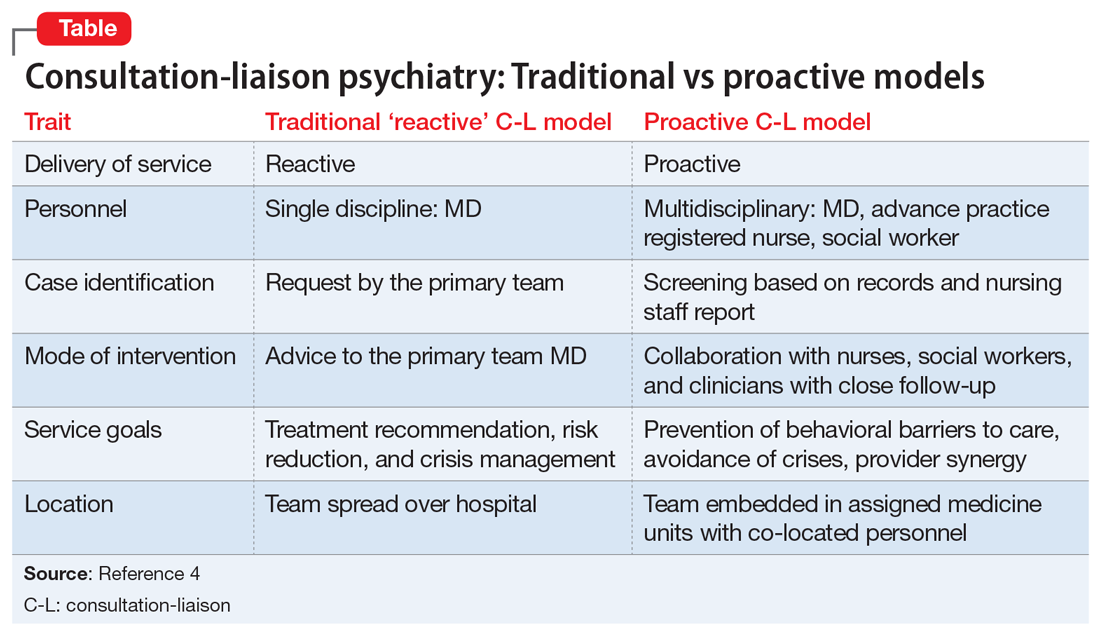

Participating in this case was highly educational for me as a trainee. This case is but one example among many where proactive consultation provided prompt care, lowered the rate of complications, reduced length of stay, and resulted in greater provider satisfaction. The Table4 contrasts the proactive and reactive consultation models. The following 5 factors are critical in the proactive consultation model4,5:

1. Standardized and reliable procedure screening of all admissions, involving a mental health professional, through record review and staff contact. This screening should identify patients with issues who will benefit specifically from in-hospital services, rather than just patients with any psychiatric issue. An electronic medical record is essential to efficient screening, team communication, and progress monitoring. Truly integrated consultation would be impossible with a paper chart.

Continued to: 2. Rapid intervention...

2. Rapid intervention that anticipates impending problems before a cascade of complications starts.

3. Collaborative engagement with the primary medical team, sharing the burden of caring for the complex inpatient, and transmitting critical behavioral management skills to all caregivers, including the skill of recognizing patients who can benefit from a psychiatric consultation.

4. Daily and close contact between behavioral and medical teams, ensuring that treatment recommendations are understood, enacted, and reinforced, ineffective treatments are discontinued, and new problems are addressed before complicating consequences arise. Dedicating specific personnel to specific hospital units and placing them in rounds simplifies communication and speeds intervention implementation.

5. A multidisciplinary consultation team, offering a range of responses, including informal curbside consultation, consultation with an advanced practice registered nurse, social work interventions, advice to discharge planning teams, psychological services, and access to specialized providers, such as addiction teams, as well as traditional consultation with an experienced psychiatrist.

Research has shown the effectiveness of proactive, embedded, multidisciplinary approaches.1-3,5 It was a gratifying experience to work in this model. I worked intimately with medical clinicians, and shared the burden of responsibilities leading to optimal patient outcomes. The proactive consultation model truly re-emphasizes the “liaison” component of C-L psychiatry, as it was originally envisioned.

1. Sledge WH, Gueorguieva R, Desan P, et al. Multidisciplinary proactive psychiatric consultation service: impact on length of stay for medical inpatients. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(4):208-216.

2. Desan PH, Zimbrean PC, Weinstein AJ, et al. Proactive psychiatric consultation services reduce length of stay for admissions to an inpatient medical team. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(6):513-520.

3. Sledge WH, Bozzo J, White-McCullum BA, et al. The cost-benefit from the perspective of the hospital of a proactive psychiatric consultation service on inpatient general medicine services. Health Econ Outcome Res Open Access. 2016;2(4):122.

4. Sledge WH, Lee HB. Proactive psychiatric consultation for hospitalized patients, a plan for the future. Health Affairs. www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20150528.048026/full/. Published May 28, 2015. Accessed September 12, 2018.

5. Desan P, Lee H, Zimbrean P, et al. New models of psychiatric consultation in the general medical hospital: liaison psychiatry is back. Psychiatr Ann. 2017;47:355-361.

During my residency training, I was trained in the standard “reactive” psychiatric consultation model. In this system, I would see consults placed by the primary team after they identified a behavioral issue in a patient. As a trainee, I experienced frequent frustrations working in this model: Consults that are discharge-dependent (“Can you see the patient before he is discharged this morning?”), consults for acute behavioral dysregulation (“The patient is near the elevator, can you come see him ASAP?”), or consults for consequences of poor management of alcohol/benzodiazepine withdrawal (“The patient is confused and trying to leave”).

As a fellow in consultation-liaison (C-L) psychiatry, I was introduced to the “proactive” consultation model, which avoids some of these issues. In this article, which is intended for residents who have not been exposed to this new approach, I explain how the proactive model changes our experience as C-L clinicians.

The Behavioral Intervention Team

At Yale New Haven Hospital, the Behavioral Intervention Team (BIT) is a proactive, multidisciplinary psychiatric consultation service that serves the internal medicine units at the hospital. The team consists of nurse practitioners, nurse liaison specialists, social workers, and psychiatrists. The team identifies and removes behavioral barriers in the care of hospitalized mentally ill patients.

The BIT collaborates closely with the medical team through formal and informal consultation; co-management of behavioral issues; education of medical, nursing, and social work staff; and direct care of complex patients with behavioral disorders. The BIT assists the medical team with transitions to appropriate outpatient and inpatient psychiatric care. The team also manages the relationship with the insurer when a patient requires a stay in a psychiatric unit.

This model has a critical financial benefit in reducing the length of stay, but it also has many other benefits. It focuses on early recognition and treatment, and helps mitigate the effects of mental or substance use disorders on patients’ recovery. BIT members educate their peers regarding management of a multitude of behavioral issues. This fosters extensive informal collaboration (“curbside consultation”), which helps patients who did not receive a formal consult. The model distributes work more rationally among different professional specialists. It yields a relationship with medical teams that is not only more effective, but also more enjoyable. In the BIT model, psychiatrists pick the cases where they feel they can have the most impact, and avoid the cases they feel they cannot have any.1-3

CASE A better approach to alcohol withdrawal

Mr. X, age 56, has a history of alcohol use disorder, hypertension, and coronary artery disease. He’s had multiple past admissions for complicated alcohol withdrawal. He is transferred from a local community hospital, where he had presented with chest pain. His last drink was 2 days prior to admission, and his blood alcohol level is <10 mg/dL.

During Mr. X’s previous hospitalizations, psychiatric consults were performed in the standard reactive model. The primary team initially prescribed an ineffective dosage of benzodiazepines for his alcohol withdrawal. This escalated his withdrawal into delirium tremens, after which psychiatry was involved. Due to this early ineffective management, the patient had a prolonged medical ICU stay and overall stay, experienced increased medical complications, and required increased staff resources because he was extremely agitated.

Continued to: During this hospitalization...

During this hospitalization, Mr. X arrives with similar medical complaints. The nurse practitioner on the BIT service, who screened all admissions each day, examines the prior notes (she finds the team sign-outs to be particularly useful). She suggests a psychiatric consult on Day 1 of the admission, which the primary medical team orders. The BIT nurse practitioner gives apt recommendations of evidence-based management, including a benzodiazepine taper, high-dose thiamine, and psychopharmacologic approaches to severe agitation. The nurse liaison specialist on the service makes behavioral plans for managing agitation, which she communicates to the nurses caring for Mr. X.

Because his withdrawal is managed more promptly, Mr. X’s length of stay is shorter and he does not experience any medical complications. The BIT social worker helps find appropriate aftercare options, including residential treatment and Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, to which the patient agrees.

Participating in this case was highly educational for me as a trainee. This case is but one example among many where proactive consultation provided prompt care, lowered the rate of complications, reduced length of stay, and resulted in greater provider satisfaction. The Table4 contrasts the proactive and reactive consultation models. The following 5 factors are critical in the proactive consultation model4,5:

1. Standardized and reliable procedure screening of all admissions, involving a mental health professional, through record review and staff contact. This screening should identify patients with issues who will benefit specifically from in-hospital services, rather than just patients with any psychiatric issue. An electronic medical record is essential to efficient screening, team communication, and progress monitoring. Truly integrated consultation would be impossible with a paper chart.

Continued to: 2. Rapid intervention...

2. Rapid intervention that anticipates impending problems before a cascade of complications starts.

3. Collaborative engagement with the primary medical team, sharing the burden of caring for the complex inpatient, and transmitting critical behavioral management skills to all caregivers, including the skill of recognizing patients who can benefit from a psychiatric consultation.

4. Daily and close contact between behavioral and medical teams, ensuring that treatment recommendations are understood, enacted, and reinforced, ineffective treatments are discontinued, and new problems are addressed before complicating consequences arise. Dedicating specific personnel to specific hospital units and placing them in rounds simplifies communication and speeds intervention implementation.

5. A multidisciplinary consultation team, offering a range of responses, including informal curbside consultation, consultation with an advanced practice registered nurse, social work interventions, advice to discharge planning teams, psychological services, and access to specialized providers, such as addiction teams, as well as traditional consultation with an experienced psychiatrist.

Research has shown the effectiveness of proactive, embedded, multidisciplinary approaches.1-3,5 It was a gratifying experience to work in this model. I worked intimately with medical clinicians, and shared the burden of responsibilities leading to optimal patient outcomes. The proactive consultation model truly re-emphasizes the “liaison” component of C-L psychiatry, as it was originally envisioned.

During my residency training, I was trained in the standard “reactive” psychiatric consultation model. In this system, I would see consults placed by the primary team after they identified a behavioral issue in a patient. As a trainee, I experienced frequent frustrations working in this model: Consults that are discharge-dependent (“Can you see the patient before he is discharged this morning?”), consults for acute behavioral dysregulation (“The patient is near the elevator, can you come see him ASAP?”), or consults for consequences of poor management of alcohol/benzodiazepine withdrawal (“The patient is confused and trying to leave”).

As a fellow in consultation-liaison (C-L) psychiatry, I was introduced to the “proactive” consultation model, which avoids some of these issues. In this article, which is intended for residents who have not been exposed to this new approach, I explain how the proactive model changes our experience as C-L clinicians.

The Behavioral Intervention Team

At Yale New Haven Hospital, the Behavioral Intervention Team (BIT) is a proactive, multidisciplinary psychiatric consultation service that serves the internal medicine units at the hospital. The team consists of nurse practitioners, nurse liaison specialists, social workers, and psychiatrists. The team identifies and removes behavioral barriers in the care of hospitalized mentally ill patients.

The BIT collaborates closely with the medical team through formal and informal consultation; co-management of behavioral issues; education of medical, nursing, and social work staff; and direct care of complex patients with behavioral disorders. The BIT assists the medical team with transitions to appropriate outpatient and inpatient psychiatric care. The team also manages the relationship with the insurer when a patient requires a stay in a psychiatric unit.

This model has a critical financial benefit in reducing the length of stay, but it also has many other benefits. It focuses on early recognition and treatment, and helps mitigate the effects of mental or substance use disorders on patients’ recovery. BIT members educate their peers regarding management of a multitude of behavioral issues. This fosters extensive informal collaboration (“curbside consultation”), which helps patients who did not receive a formal consult. The model distributes work more rationally among different professional specialists. It yields a relationship with medical teams that is not only more effective, but also more enjoyable. In the BIT model, psychiatrists pick the cases where they feel they can have the most impact, and avoid the cases they feel they cannot have any.1-3

CASE A better approach to alcohol withdrawal

Mr. X, age 56, has a history of alcohol use disorder, hypertension, and coronary artery disease. He’s had multiple past admissions for complicated alcohol withdrawal. He is transferred from a local community hospital, where he had presented with chest pain. His last drink was 2 days prior to admission, and his blood alcohol level is <10 mg/dL.

During Mr. X’s previous hospitalizations, psychiatric consults were performed in the standard reactive model. The primary team initially prescribed an ineffective dosage of benzodiazepines for his alcohol withdrawal. This escalated his withdrawal into delirium tremens, after which psychiatry was involved. Due to this early ineffective management, the patient had a prolonged medical ICU stay and overall stay, experienced increased medical complications, and required increased staff resources because he was extremely agitated.

Continued to: During this hospitalization...

During this hospitalization, Mr. X arrives with similar medical complaints. The nurse practitioner on the BIT service, who screened all admissions each day, examines the prior notes (she finds the team sign-outs to be particularly useful). She suggests a psychiatric consult on Day 1 of the admission, which the primary medical team orders. The BIT nurse practitioner gives apt recommendations of evidence-based management, including a benzodiazepine taper, high-dose thiamine, and psychopharmacologic approaches to severe agitation. The nurse liaison specialist on the service makes behavioral plans for managing agitation, which she communicates to the nurses caring for Mr. X.

Because his withdrawal is managed more promptly, Mr. X’s length of stay is shorter and he does not experience any medical complications. The BIT social worker helps find appropriate aftercare options, including residential treatment and Alcoholics Anonymous meetings, to which the patient agrees.

Participating in this case was highly educational for me as a trainee. This case is but one example among many where proactive consultation provided prompt care, lowered the rate of complications, reduced length of stay, and resulted in greater provider satisfaction. The Table4 contrasts the proactive and reactive consultation models. The following 5 factors are critical in the proactive consultation model4,5:

1. Standardized and reliable procedure screening of all admissions, involving a mental health professional, through record review and staff contact. This screening should identify patients with issues who will benefit specifically from in-hospital services, rather than just patients with any psychiatric issue. An electronic medical record is essential to efficient screening, team communication, and progress monitoring. Truly integrated consultation would be impossible with a paper chart.

Continued to: 2. Rapid intervention...

2. Rapid intervention that anticipates impending problems before a cascade of complications starts.

3. Collaborative engagement with the primary medical team, sharing the burden of caring for the complex inpatient, and transmitting critical behavioral management skills to all caregivers, including the skill of recognizing patients who can benefit from a psychiatric consultation.

4. Daily and close contact between behavioral and medical teams, ensuring that treatment recommendations are understood, enacted, and reinforced, ineffective treatments are discontinued, and new problems are addressed before complicating consequences arise. Dedicating specific personnel to specific hospital units and placing them in rounds simplifies communication and speeds intervention implementation.

5. A multidisciplinary consultation team, offering a range of responses, including informal curbside consultation, consultation with an advanced practice registered nurse, social work interventions, advice to discharge planning teams, psychological services, and access to specialized providers, such as addiction teams, as well as traditional consultation with an experienced psychiatrist.

Research has shown the effectiveness of proactive, embedded, multidisciplinary approaches.1-3,5 It was a gratifying experience to work in this model. I worked intimately with medical clinicians, and shared the burden of responsibilities leading to optimal patient outcomes. The proactive consultation model truly re-emphasizes the “liaison” component of C-L psychiatry, as it was originally envisioned.

1. Sledge WH, Gueorguieva R, Desan P, et al. Multidisciplinary proactive psychiatric consultation service: impact on length of stay for medical inpatients. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(4):208-216.

2. Desan PH, Zimbrean PC, Weinstein AJ, et al. Proactive psychiatric consultation services reduce length of stay for admissions to an inpatient medical team. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(6):513-520.

3. Sledge WH, Bozzo J, White-McCullum BA, et al. The cost-benefit from the perspective of the hospital of a proactive psychiatric consultation service on inpatient general medicine services. Health Econ Outcome Res Open Access. 2016;2(4):122.

4. Sledge WH, Lee HB. Proactive psychiatric consultation for hospitalized patients, a plan for the future. Health Affairs. www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20150528.048026/full/. Published May 28, 2015. Accessed September 12, 2018.

5. Desan P, Lee H, Zimbrean P, et al. New models of psychiatric consultation in the general medical hospital: liaison psychiatry is back. Psychiatr Ann. 2017;47:355-361.

1. Sledge WH, Gueorguieva R, Desan P, et al. Multidisciplinary proactive psychiatric consultation service: impact on length of stay for medical inpatients. Psychother Psychosom. 2015;84(4):208-216.

2. Desan PH, Zimbrean PC, Weinstein AJ, et al. Proactive psychiatric consultation services reduce length of stay for admissions to an inpatient medical team. Psychosomatics. 2011;52(6):513-520.

3. Sledge WH, Bozzo J, White-McCullum BA, et al. The cost-benefit from the perspective of the hospital of a proactive psychiatric consultation service on inpatient general medicine services. Health Econ Outcome Res Open Access. 2016;2(4):122.

4. Sledge WH, Lee HB. Proactive psychiatric consultation for hospitalized patients, a plan for the future. Health Affairs. www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20150528.048026/full/. Published May 28, 2015. Accessed September 12, 2018.

5. Desan P, Lee H, Zimbrean P, et al. New models of psychiatric consultation in the general medical hospital: liaison psychiatry is back. Psychiatr Ann. 2017;47:355-361.

Breaking bad news

As psychiatrists, we do not often encounter situations in which we need to inform patients and their families that they have a life-threatening diagnosis. Nonetheless, on the rare occasions when we work with such patients, new psychiatrists may find their clinical skills challenged. Breaking bad news remains an aspect of clinical training that is often overlooked by medical schools.

Here I present a case that illustrates the challenges residents and medical students face when they need to deliver bad news and review the current literature on how to present patients with this type of information.

Case

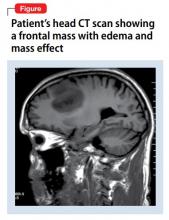

Bizarre behavior, difficult diagnosis

Mr. C, age 59, with a 1-year history of major depressive disorder, was brought to the emergency department by his wife for worsening depression and disorganized behavior over the course of 3 weeks. Mr. C had obsessive thoughts about arranging things in symmetrical patterns, difficulty sleeping, loss of appetite, and anhedonia. His wife reported that his bizarre, disorganized behavior further intensified in the previous week; he was urinating on the rug, rubbing his genitals against the bathroom counter, staring into space without moving for prolonged periods of time, and arranging his food in symmetrical patterns. Mr. C has no reported substance use or suicidal or homicidal ideation.

Strategies for delivering bad news

Initially, I struggled when I realized I would have to deliver the news of this potentially life-threatening diagnosis to the patient and his wife because I had not received any training on how to do so. However, I took time to look into the literature and used the skills that we as psychiatrists have, including empathy, listening, and validation. My experience with Mr. C and his family made me realize that delivering bad news with empathy and being involved in the struggle that follows can make a significant difference to their suffering.

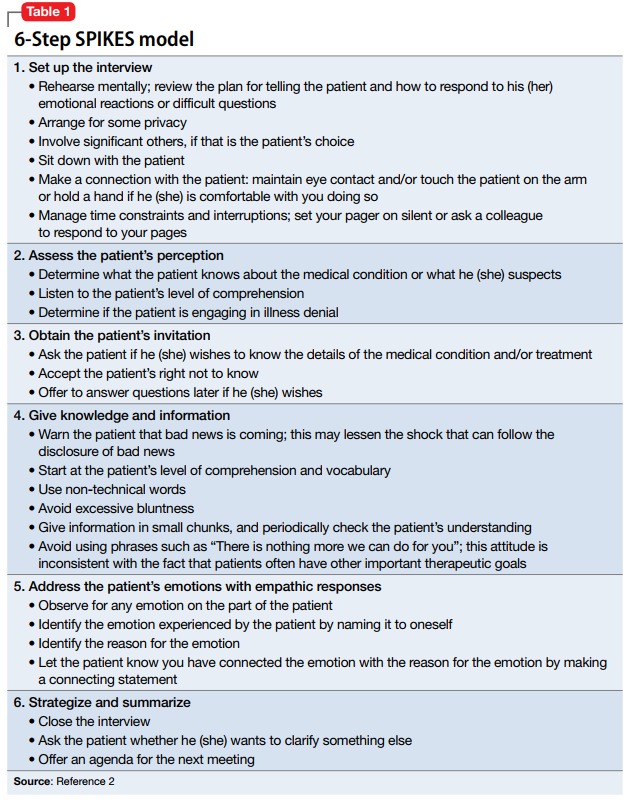

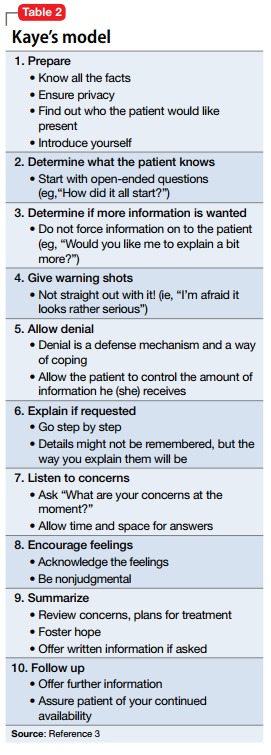

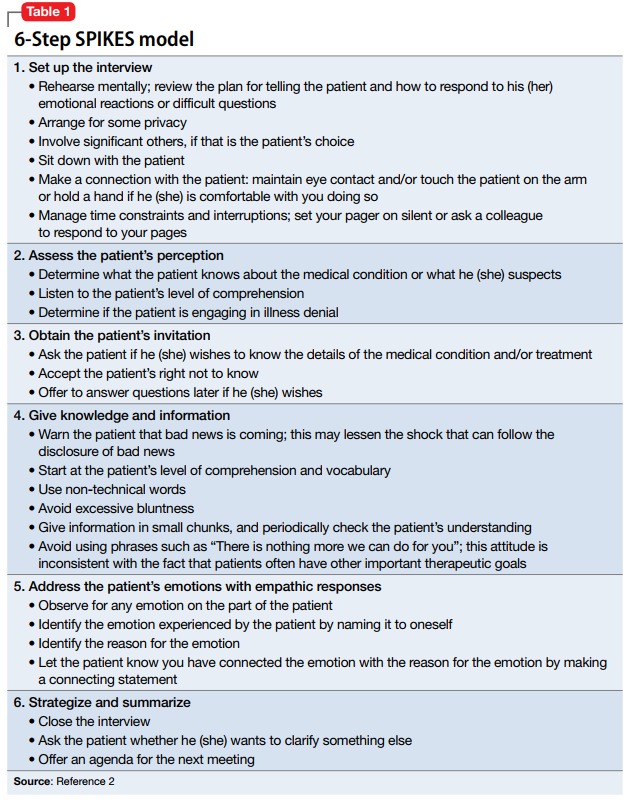

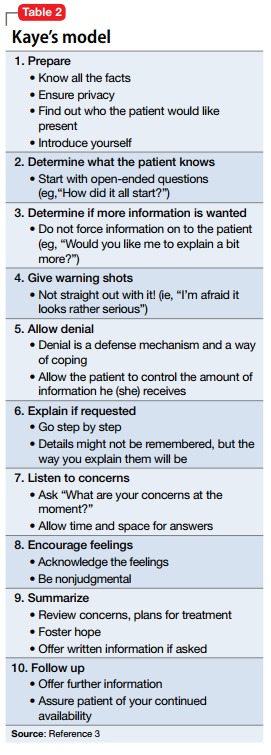

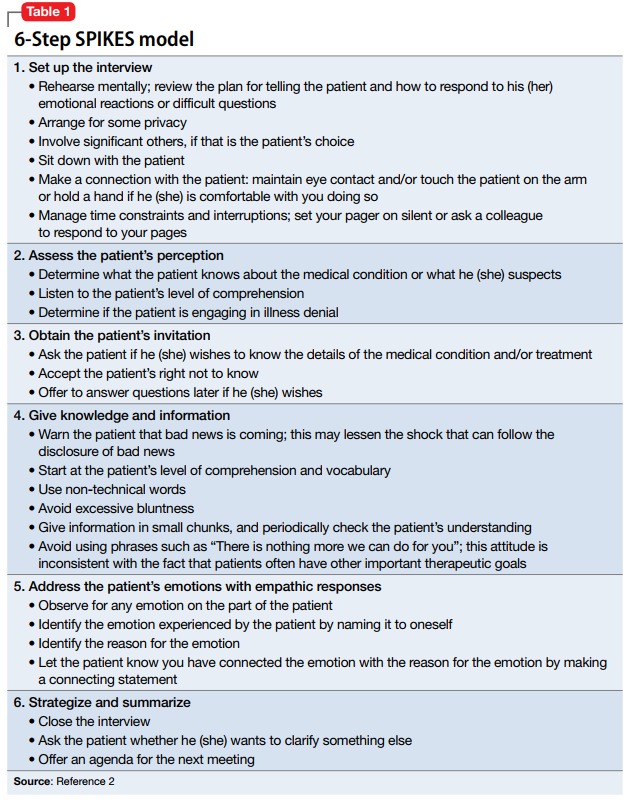

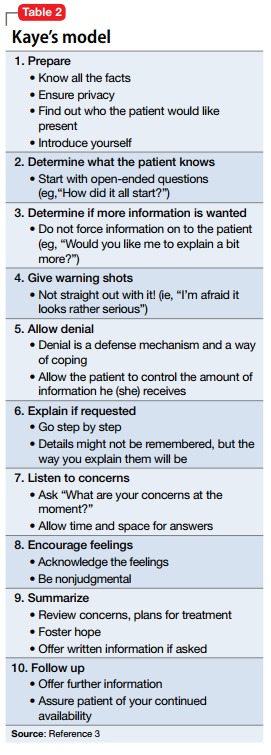

There are various models and techniques for breaking bad news to patients. Two of the most commonly used models in the oncology setting are the SPIKES (Set up, Perception, Interview, Knowledge, Emotions, Strategize and Summarize) model (Table 12) and Kaye’s model (Table 23).

A clinician’s attitude and communication skills play a crucial role in how well patients and family members cope when they receive bad news. When delivering bad news:

- Choose a setting with adequate privacy, use simple language that distills medical facts into appreciable pieces of information, and give the recipients ample space and time to process the implications. Doing so will foster better understanding and facilitate their acceptance of the bad news.

- Although physicians can rarely appreciate the patient’s feelings at a personal level, make every effort to validate their thoughts and offer emotional support. In such situations, it is often appropriate to move closer to the recipient and make brief physical gestures, such as laying a hand on the shoulder, which might comfort them.

- In the aftermath of such encounters, it is important to remain active in the patient’s emotional journey and available for further clarification, which can mitigate uncertainties and facilitate the difficult process of coming to terms with new realities.4,5

1. Munjal S, Pahlajani S, Baxi A, et al. Delayed diagnosis of glioblastoma multiforme presenting with atypical psychiatric symptoms. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2016;18(6). doi: 10.4088/PCC.16l01972.

2. Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, et al. SPIKES-a six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302-311.

3. Kaye P. Breaking bad news: a 10 step approach. Northampton, MA: EPL Publications; 1995.

4. Chaturvedi SK, Chandra PS. Breaking bad news-issues important for psychiatrists. Asian J Psychiatr. 2010;3(2):87-89.

5. VandeKieft GK. Breaking bad news. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64(12):1975-1978.

As psychiatrists, we do not often encounter situations in which we need to inform patients and their families that they have a life-threatening diagnosis. Nonetheless, on the rare occasions when we work with such patients, new psychiatrists may find their clinical skills challenged. Breaking bad news remains an aspect of clinical training that is often overlooked by medical schools.

Here I present a case that illustrates the challenges residents and medical students face when they need to deliver bad news and review the current literature on how to present patients with this type of information.

Case

Bizarre behavior, difficult diagnosis

Mr. C, age 59, with a 1-year history of major depressive disorder, was brought to the emergency department by his wife for worsening depression and disorganized behavior over the course of 3 weeks. Mr. C had obsessive thoughts about arranging things in symmetrical patterns, difficulty sleeping, loss of appetite, and anhedonia. His wife reported that his bizarre, disorganized behavior further intensified in the previous week; he was urinating on the rug, rubbing his genitals against the bathroom counter, staring into space without moving for prolonged periods of time, and arranging his food in symmetrical patterns. Mr. C has no reported substance use or suicidal or homicidal ideation.

Strategies for delivering bad news

Initially, I struggled when I realized I would have to deliver the news of this potentially life-threatening diagnosis to the patient and his wife because I had not received any training on how to do so. However, I took time to look into the literature and used the skills that we as psychiatrists have, including empathy, listening, and validation. My experience with Mr. C and his family made me realize that delivering bad news with empathy and being involved in the struggle that follows can make a significant difference to their suffering.

There are various models and techniques for breaking bad news to patients. Two of the most commonly used models in the oncology setting are the SPIKES (Set up, Perception, Interview, Knowledge, Emotions, Strategize and Summarize) model (Table 12) and Kaye’s model (Table 23).

A clinician’s attitude and communication skills play a crucial role in how well patients and family members cope when they receive bad news. When delivering bad news:

- Choose a setting with adequate privacy, use simple language that distills medical facts into appreciable pieces of information, and give the recipients ample space and time to process the implications. Doing so will foster better understanding and facilitate their acceptance of the bad news.

- Although physicians can rarely appreciate the patient’s feelings at a personal level, make every effort to validate their thoughts and offer emotional support. In such situations, it is often appropriate to move closer to the recipient and make brief physical gestures, such as laying a hand on the shoulder, which might comfort them.

- In the aftermath of such encounters, it is important to remain active in the patient’s emotional journey and available for further clarification, which can mitigate uncertainties and facilitate the difficult process of coming to terms with new realities.4,5

As psychiatrists, we do not often encounter situations in which we need to inform patients and their families that they have a life-threatening diagnosis. Nonetheless, on the rare occasions when we work with such patients, new psychiatrists may find their clinical skills challenged. Breaking bad news remains an aspect of clinical training that is often overlooked by medical schools.

Here I present a case that illustrates the challenges residents and medical students face when they need to deliver bad news and review the current literature on how to present patients with this type of information.

Case

Bizarre behavior, difficult diagnosis

Mr. C, age 59, with a 1-year history of major depressive disorder, was brought to the emergency department by his wife for worsening depression and disorganized behavior over the course of 3 weeks. Mr. C had obsessive thoughts about arranging things in symmetrical patterns, difficulty sleeping, loss of appetite, and anhedonia. His wife reported that his bizarre, disorganized behavior further intensified in the previous week; he was urinating on the rug, rubbing his genitals against the bathroom counter, staring into space without moving for prolonged periods of time, and arranging his food in symmetrical patterns. Mr. C has no reported substance use or suicidal or homicidal ideation.

Strategies for delivering bad news

Initially, I struggled when I realized I would have to deliver the news of this potentially life-threatening diagnosis to the patient and his wife because I had not received any training on how to do so. However, I took time to look into the literature and used the skills that we as psychiatrists have, including empathy, listening, and validation. My experience with Mr. C and his family made me realize that delivering bad news with empathy and being involved in the struggle that follows can make a significant difference to their suffering.

There are various models and techniques for breaking bad news to patients. Two of the most commonly used models in the oncology setting are the SPIKES (Set up, Perception, Interview, Knowledge, Emotions, Strategize and Summarize) model (Table 12) and Kaye’s model (Table 23).

A clinician’s attitude and communication skills play a crucial role in how well patients and family members cope when they receive bad news. When delivering bad news:

- Choose a setting with adequate privacy, use simple language that distills medical facts into appreciable pieces of information, and give the recipients ample space and time to process the implications. Doing so will foster better understanding and facilitate their acceptance of the bad news.

- Although physicians can rarely appreciate the patient’s feelings at a personal level, make every effort to validate their thoughts and offer emotional support. In such situations, it is often appropriate to move closer to the recipient and make brief physical gestures, such as laying a hand on the shoulder, which might comfort them.

- In the aftermath of such encounters, it is important to remain active in the patient’s emotional journey and available for further clarification, which can mitigate uncertainties and facilitate the difficult process of coming to terms with new realities.4,5

1. Munjal S, Pahlajani S, Baxi A, et al. Delayed diagnosis of glioblastoma multiforme presenting with atypical psychiatric symptoms. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2016;18(6). doi: 10.4088/PCC.16l01972.

2. Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, et al. SPIKES-a six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302-311.

3. Kaye P. Breaking bad news: a 10 step approach. Northampton, MA: EPL Publications; 1995.

4. Chaturvedi SK, Chandra PS. Breaking bad news-issues important for psychiatrists. Asian J Psychiatr. 2010;3(2):87-89.

5. VandeKieft GK. Breaking bad news. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64(12):1975-1978.

1. Munjal S, Pahlajani S, Baxi A, et al. Delayed diagnosis of glioblastoma multiforme presenting with atypical psychiatric symptoms. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2016;18(6). doi: 10.4088/PCC.16l01972.

2. Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, et al. SPIKES-a six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5(4):302-311.

3. Kaye P. Breaking bad news: a 10 step approach. Northampton, MA: EPL Publications; 1995.

4. Chaturvedi SK, Chandra PS. Breaking bad news-issues important for psychiatrists. Asian J Psychiatr. 2010;3(2):87-89.

5. VandeKieft GK. Breaking bad news. Am Fam Physician. 2001;64(12):1975-1978.

Don’t assume that psychiatric patients lack capacity to make decisions about care

Some practitioners of medicine—including psychiatrists—might equate “psychosis” with incapacity, but that isn’t necessarily true. Even patients who, by most measures, are deemed psychotic might be capable of making wise and thoughtful decisions about their life. The case I describe in this article demonstrates that fact.

While rotating on a busy consultation service, I was asked to evaluate the capacity of a woman who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and was being seen for worsening auditory hallucinations and progressive weight loss. She had a complicated medical course that eventually led to multiple requests to the consult team for a capacity evaluation.

The question of capacity in this patient, and in the psychiatric population generally, motivated me to review the literature, because the assumption by many on the medical teams involved in this patient’s care was that psychiatric patients do not have the capacity to participate in their own care. My goal here is to clarify the misconceptions in regard to this situation.

CASE REPORT

Schizophrenia, weight loss, back pain

Ms. V, age 67, a resident of a group home for the past 6 years, was brought to the emergency department (ED) because of weight loss and auditory hallucinations that had developed during the past few months. She had a history of paranoid schizophrenia that included several psychiatric hospitalizations but no known medical history.

The patient appeared cachectic and dehydrated. When approached, she was pleasant and reported hearing voices of the “devil.”

“They are not scary,” she confided. “They talk to me about art and literature.”

Over the past 6 months, Ms. V had lost 60 lb; she was now bedridden because of back pain. Collateral information obtained from staff members at the group home indicated that she had refused to get out of bed, and only intermittently took her medications or ate meals during the past few months. In general, however, she had been relatively stable over the course of her psychiatric illness, was adherent to psychiatric treatment, and had had no psychiatric hospitalizations in the past 3 decades.

Ominous development. Although the ED staff was convinced that Ms. V needed psychiatric admission, we (the consult team) first requested a detailed medical workup, including imaging studies. A CT scan showed multiple metastatic foci throughout her spine. She was admitted to the medical service.

Respiratory distress developed; her condition deteriorated. Numerous capacity consults were requested because she refused a medical workup or to sign do-not-resuscitate and do-not-intubate orders. Each time an evaluation was performed, Ms. V was deemed by various clinicians on the consult service to have decision-making capacity.

The patient grew unhappy with the staff’s insistence that she undergo more tests regardless of her stated wishes. The palliative care service determined that further workup would not benefit her medically: Ms. V’s condition would be grave and her prognosis poor regardless of what treatment she received.

The medical team continued to believe that, because that this patient had a mental illness and was actively hallucinating, she did not have the capacity to refuse any proposed treatments and tests.

What is capacity?

Capacity is an assessment of a person’s ability to make rational decisions. This includes the ability to understand, appreciate, and manipulate information in reaching such decisions. Determining whether a patient has the capacity to accept or refuse treatment is a medical decision that any physician can make; however, consultation−liaison psychiatrists are the experts who often are involved in this activity, particularly in patients who have a psychiatric comorbidity.

Capacity is evaluated by assessing 4 standards; that is, whether a patient can:

- communicate choice about proposed treatment

- understand her (his) medical situation

- appreciate the situation and its consequences

- manipulate information to reach a rational decision.1-3

- manipulate information to reach a rational decision.

CASE REPORT continued

Although Ms. V’s health was deteriorating and her auditory hallucinations were becoming worse, she appeared insightful about her medical problems, understood her prognosis, and wanted comfort care. She understood that having multiple metastases meant a poor prognosis, and that a biopsy might yield a medical diagnosis. She stated, “If it were caught earlier and I was better able to tolerate treatment, it would make sense to know for sure, but now it doesn’t make sense. I just want to have no pain in my end.”

Misconceptions

In a study by Ganzini et al,4,5 395 consultation−liaison psychiatrists, geriatricians, and geriatric psychologists responded to a survey in which they rated types of misunderstandings by clinicians who refer patients for assessment of decision-making capacity. Seventy percent reported that it is common that, when a patient has a mental illness such as schizophrenia, practitioners think that the patient lacks capacity to make medical decisions. However, results of a meta-analysis by Jeste et al,6 in which the magnitude of impairment of decisional capacity in patients with schizophrenia was assessed in comparison to that of normal subjects, suggest that the presence of schizophrenia does not necessarily mean the patient has impaired capacity.

Voluntary participation in research. Many patients with schizophrenia volunteer to participate in clinical trials even when they are acutely psychotic and admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Given the importance placed on participants’ voluntary informed consent as a prerequisite for ethical conduct of research, the cognitive and emotional impairments associated with schizophrenia raise questions about patients’ capacity to consent.

As is true in other areas of functional capacity, the ability of patients with schizophrenia to make competent decisions relates more to their overall cognitive functioning than to the presence or absence of specific symptoms of the disorder.7 Documentation of longitudinal consent-related abilities among research participants with schizophrenia in the long-term Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness study indicated that most participants had stable or improved consent-related abilities. Although almost 25% of participants experienced substantial worsening, only 4% fell below the study’s capacity threshold for enrollment.8

What I learned from Ms. V

A diagnosis of schizophrenia does not automatically render a person unable to make decisions about medical care. Even patients who have severe mental illness might have significant intact areas of reality testing. Ethically, it is important to at least consider that the chronically mentally ill can understand treatment options and express consistent choices.

Healthcare providers might tend to exclude psychiatric patients from end-of-life decisions because they (1) are worried about the emotional fragility of such patients and (2) assume that patients lack capacity to participate in making such important decisions. The case presented here is an example of a patient with a severe psychiatric diagnosis being able to participate in her care despite her mental state.

1. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(25):1635-1638.

2. Leo RJ. Competency and the capacity to make treatment decisions: a primer for primary care physicians. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;1(5):131-141.

3. White MM, Lofwall MR. Challenges of the capacity evaluation for the consultation-liaison psychiatrist. J Psychiatr Pract. 2015;21(2):160-170.

4. Ganzini L, Volicer L, Nelson W, et al. Pitfalls in assessment of decision-making capacity. Psychosomatics. 2003;44(3):237-243.

5. Ganzini L, Volicer L, Nelson WA, et al. Ten myths about decision-making capacity. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2005;6(3):S100-S104.

6. Jeste DV, Depp CA, Palmer BW. Magnitude of impairment in decisional capacity in people with schizophrenia compared to normal subjects: an overview. Schizophr Bull. 2005;32(1):121-128.

7. Appelbaum PS. Decisional capacity of patients with schizophrenia to consent to research: taking stock. Schizophr Bull. 2005;32(1):22-25.

8. Stroup TS, Appelbaum PS, Gu H, et al. Longitudinal consent-related abilities among research participants with schizophrenia: results from the CATIE study. Schizophr Res. 2011;130(1-3):47-52.

Some practitioners of medicine—including psychiatrists—might equate “psychosis” with incapacity, but that isn’t necessarily true. Even patients who, by most measures, are deemed psychotic might be capable of making wise and thoughtful decisions about their life. The case I describe in this article demonstrates that fact.

While rotating on a busy consultation service, I was asked to evaluate the capacity of a woman who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and was being seen for worsening auditory hallucinations and progressive weight loss. She had a complicated medical course that eventually led to multiple requests to the consult team for a capacity evaluation.

The question of capacity in this patient, and in the psychiatric population generally, motivated me to review the literature, because the assumption by many on the medical teams involved in this patient’s care was that psychiatric patients do not have the capacity to participate in their own care. My goal here is to clarify the misconceptions in regard to this situation.

CASE REPORT

Schizophrenia, weight loss, back pain

Ms. V, age 67, a resident of a group home for the past 6 years, was brought to the emergency department (ED) because of weight loss and auditory hallucinations that had developed during the past few months. She had a history of paranoid schizophrenia that included several psychiatric hospitalizations but no known medical history.

The patient appeared cachectic and dehydrated. When approached, she was pleasant and reported hearing voices of the “devil.”

“They are not scary,” she confided. “They talk to me about art and literature.”

Over the past 6 months, Ms. V had lost 60 lb; she was now bedridden because of back pain. Collateral information obtained from staff members at the group home indicated that she had refused to get out of bed, and only intermittently took her medications or ate meals during the past few months. In general, however, she had been relatively stable over the course of her psychiatric illness, was adherent to psychiatric treatment, and had had no psychiatric hospitalizations in the past 3 decades.

Ominous development. Although the ED staff was convinced that Ms. V needed psychiatric admission, we (the consult team) first requested a detailed medical workup, including imaging studies. A CT scan showed multiple metastatic foci throughout her spine. She was admitted to the medical service.

Respiratory distress developed; her condition deteriorated. Numerous capacity consults were requested because she refused a medical workup or to sign do-not-resuscitate and do-not-intubate orders. Each time an evaluation was performed, Ms. V was deemed by various clinicians on the consult service to have decision-making capacity.

The patient grew unhappy with the staff’s insistence that she undergo more tests regardless of her stated wishes. The palliative care service determined that further workup would not benefit her medically: Ms. V’s condition would be grave and her prognosis poor regardless of what treatment she received.

The medical team continued to believe that, because that this patient had a mental illness and was actively hallucinating, she did not have the capacity to refuse any proposed treatments and tests.

What is capacity?

Capacity is an assessment of a person’s ability to make rational decisions. This includes the ability to understand, appreciate, and manipulate information in reaching such decisions. Determining whether a patient has the capacity to accept or refuse treatment is a medical decision that any physician can make; however, consultation−liaison psychiatrists are the experts who often are involved in this activity, particularly in patients who have a psychiatric comorbidity.

Capacity is evaluated by assessing 4 standards; that is, whether a patient can:

- communicate choice about proposed treatment

- understand her (his) medical situation

- appreciate the situation and its consequences

- manipulate information to reach a rational decision.1-3

- manipulate information to reach a rational decision.

CASE REPORT continued

Although Ms. V’s health was deteriorating and her auditory hallucinations were becoming worse, she appeared insightful about her medical problems, understood her prognosis, and wanted comfort care. She understood that having multiple metastases meant a poor prognosis, and that a biopsy might yield a medical diagnosis. She stated, “If it were caught earlier and I was better able to tolerate treatment, it would make sense to know for sure, but now it doesn’t make sense. I just want to have no pain in my end.”

Misconceptions

In a study by Ganzini et al,4,5 395 consultation−liaison psychiatrists, geriatricians, and geriatric psychologists responded to a survey in which they rated types of misunderstandings by clinicians who refer patients for assessment of decision-making capacity. Seventy percent reported that it is common that, when a patient has a mental illness such as schizophrenia, practitioners think that the patient lacks capacity to make medical decisions. However, results of a meta-analysis by Jeste et al,6 in which the magnitude of impairment of decisional capacity in patients with schizophrenia was assessed in comparison to that of normal subjects, suggest that the presence of schizophrenia does not necessarily mean the patient has impaired capacity.

Voluntary participation in research. Many patients with schizophrenia volunteer to participate in clinical trials even when they are acutely psychotic and admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Given the importance placed on participants’ voluntary informed consent as a prerequisite for ethical conduct of research, the cognitive and emotional impairments associated with schizophrenia raise questions about patients’ capacity to consent.

As is true in other areas of functional capacity, the ability of patients with schizophrenia to make competent decisions relates more to their overall cognitive functioning than to the presence or absence of specific symptoms of the disorder.7 Documentation of longitudinal consent-related abilities among research participants with schizophrenia in the long-term Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness study indicated that most participants had stable or improved consent-related abilities. Although almost 25% of participants experienced substantial worsening, only 4% fell below the study’s capacity threshold for enrollment.8

What I learned from Ms. V

A diagnosis of schizophrenia does not automatically render a person unable to make decisions about medical care. Even patients who have severe mental illness might have significant intact areas of reality testing. Ethically, it is important to at least consider that the chronically mentally ill can understand treatment options and express consistent choices.

Healthcare providers might tend to exclude psychiatric patients from end-of-life decisions because they (1) are worried about the emotional fragility of such patients and (2) assume that patients lack capacity to participate in making such important decisions. The case presented here is an example of a patient with a severe psychiatric diagnosis being able to participate in her care despite her mental state.

Some practitioners of medicine—including psychiatrists—might equate “psychosis” with incapacity, but that isn’t necessarily true. Even patients who, by most measures, are deemed psychotic might be capable of making wise and thoughtful decisions about their life. The case I describe in this article demonstrates that fact.

While rotating on a busy consultation service, I was asked to evaluate the capacity of a woman who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia and was being seen for worsening auditory hallucinations and progressive weight loss. She had a complicated medical course that eventually led to multiple requests to the consult team for a capacity evaluation.

The question of capacity in this patient, and in the psychiatric population generally, motivated me to review the literature, because the assumption by many on the medical teams involved in this patient’s care was that psychiatric patients do not have the capacity to participate in their own care. My goal here is to clarify the misconceptions in regard to this situation.

CASE REPORT

Schizophrenia, weight loss, back pain

Ms. V, age 67, a resident of a group home for the past 6 years, was brought to the emergency department (ED) because of weight loss and auditory hallucinations that had developed during the past few months. She had a history of paranoid schizophrenia that included several psychiatric hospitalizations but no known medical history.

The patient appeared cachectic and dehydrated. When approached, she was pleasant and reported hearing voices of the “devil.”

“They are not scary,” she confided. “They talk to me about art and literature.”

Over the past 6 months, Ms. V had lost 60 lb; she was now bedridden because of back pain. Collateral information obtained from staff members at the group home indicated that she had refused to get out of bed, and only intermittently took her medications or ate meals during the past few months. In general, however, she had been relatively stable over the course of her psychiatric illness, was adherent to psychiatric treatment, and had had no psychiatric hospitalizations in the past 3 decades.

Ominous development. Although the ED staff was convinced that Ms. V needed psychiatric admission, we (the consult team) first requested a detailed medical workup, including imaging studies. A CT scan showed multiple metastatic foci throughout her spine. She was admitted to the medical service.

Respiratory distress developed; her condition deteriorated. Numerous capacity consults were requested because she refused a medical workup or to sign do-not-resuscitate and do-not-intubate orders. Each time an evaluation was performed, Ms. V was deemed by various clinicians on the consult service to have decision-making capacity.

The patient grew unhappy with the staff’s insistence that she undergo more tests regardless of her stated wishes. The palliative care service determined that further workup would not benefit her medically: Ms. V’s condition would be grave and her prognosis poor regardless of what treatment she received.

The medical team continued to believe that, because that this patient had a mental illness and was actively hallucinating, she did not have the capacity to refuse any proposed treatments and tests.

What is capacity?

Capacity is an assessment of a person’s ability to make rational decisions. This includes the ability to understand, appreciate, and manipulate information in reaching such decisions. Determining whether a patient has the capacity to accept or refuse treatment is a medical decision that any physician can make; however, consultation−liaison psychiatrists are the experts who often are involved in this activity, particularly in patients who have a psychiatric comorbidity.

Capacity is evaluated by assessing 4 standards; that is, whether a patient can:

- communicate choice about proposed treatment

- understand her (his) medical situation

- appreciate the situation and its consequences

- manipulate information to reach a rational decision.1-3

- manipulate information to reach a rational decision.

CASE REPORT continued

Although Ms. V’s health was deteriorating and her auditory hallucinations were becoming worse, she appeared insightful about her medical problems, understood her prognosis, and wanted comfort care. She understood that having multiple metastases meant a poor prognosis, and that a biopsy might yield a medical diagnosis. She stated, “If it were caught earlier and I was better able to tolerate treatment, it would make sense to know for sure, but now it doesn’t make sense. I just want to have no pain in my end.”

Misconceptions

In a study by Ganzini et al,4,5 395 consultation−liaison psychiatrists, geriatricians, and geriatric psychologists responded to a survey in which they rated types of misunderstandings by clinicians who refer patients for assessment of decision-making capacity. Seventy percent reported that it is common that, when a patient has a mental illness such as schizophrenia, practitioners think that the patient lacks capacity to make medical decisions. However, results of a meta-analysis by Jeste et al,6 in which the magnitude of impairment of decisional capacity in patients with schizophrenia was assessed in comparison to that of normal subjects, suggest that the presence of schizophrenia does not necessarily mean the patient has impaired capacity.

Voluntary participation in research. Many patients with schizophrenia volunteer to participate in clinical trials even when they are acutely psychotic and admitted to a psychiatric hospital. Given the importance placed on participants’ voluntary informed consent as a prerequisite for ethical conduct of research, the cognitive and emotional impairments associated with schizophrenia raise questions about patients’ capacity to consent.

As is true in other areas of functional capacity, the ability of patients with schizophrenia to make competent decisions relates more to their overall cognitive functioning than to the presence or absence of specific symptoms of the disorder.7 Documentation of longitudinal consent-related abilities among research participants with schizophrenia in the long-term Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness study indicated that most participants had stable or improved consent-related abilities. Although almost 25% of participants experienced substantial worsening, only 4% fell below the study’s capacity threshold for enrollment.8

What I learned from Ms. V

A diagnosis of schizophrenia does not automatically render a person unable to make decisions about medical care. Even patients who have severe mental illness might have significant intact areas of reality testing. Ethically, it is important to at least consider that the chronically mentally ill can understand treatment options and express consistent choices.

Healthcare providers might tend to exclude psychiatric patients from end-of-life decisions because they (1) are worried about the emotional fragility of such patients and (2) assume that patients lack capacity to participate in making such important decisions. The case presented here is an example of a patient with a severe psychiatric diagnosis being able to participate in her care despite her mental state.

1. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(25):1635-1638.

2. Leo RJ. Competency and the capacity to make treatment decisions: a primer for primary care physicians. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;1(5):131-141.

3. White MM, Lofwall MR. Challenges of the capacity evaluation for the consultation-liaison psychiatrist. J Psychiatr Pract. 2015;21(2):160-170.

4. Ganzini L, Volicer L, Nelson W, et al. Pitfalls in assessment of decision-making capacity. Psychosomatics. 2003;44(3):237-243.

5. Ganzini L, Volicer L, Nelson WA, et al. Ten myths about decision-making capacity. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2005;6(3):S100-S104.

6. Jeste DV, Depp CA, Palmer BW. Magnitude of impairment in decisional capacity in people with schizophrenia compared to normal subjects: an overview. Schizophr Bull. 2005;32(1):121-128.

7. Appelbaum PS. Decisional capacity of patients with schizophrenia to consent to research: taking stock. Schizophr Bull. 2005;32(1):22-25.

8. Stroup TS, Appelbaum PS, Gu H, et al. Longitudinal consent-related abilities among research participants with schizophrenia: results from the CATIE study. Schizophr Res. 2011;130(1-3):47-52.

1. Appelbaum PS, Grisso T. Assessing patients’ capacities to consent to treatment. N Engl J Med. 1988;319(25):1635-1638.

2. Leo RJ. Competency and the capacity to make treatment decisions: a primer for primary care physicians. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 1999;1(5):131-141.

3. White MM, Lofwall MR. Challenges of the capacity evaluation for the consultation-liaison psychiatrist. J Psychiatr Pract. 2015;21(2):160-170.

4. Ganzini L, Volicer L, Nelson W, et al. Pitfalls in assessment of decision-making capacity. Psychosomatics. 2003;44(3):237-243.

5. Ganzini L, Volicer L, Nelson WA, et al. Ten myths about decision-making capacity. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2005;6(3):S100-S104.

6. Jeste DV, Depp CA, Palmer BW. Magnitude of impairment in decisional capacity in people with schizophrenia compared to normal subjects: an overview. Schizophr Bull. 2005;32(1):121-128.

7. Appelbaum PS. Decisional capacity of patients with schizophrenia to consent to research: taking stock. Schizophr Bull. 2005;32(1):22-25.

8. Stroup TS, Appelbaum PS, Gu H, et al. Longitudinal consent-related abilities among research participants with schizophrenia: results from the CATIE study. Schizophr Res. 2011;130(1-3):47-52.