User login

Breast cancer is the most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death in women in the United States, with an estimated 252,710 new cases and 40,610 deaths in 2017.1 Breast cancer mortality is prevented by the use of regular screening mammography, as demonstrated by randomized controlled trials (20% reduction), incidence-based mortality studies (38% to 40% reduction), and service screening studies (48% to 49% reduction).2

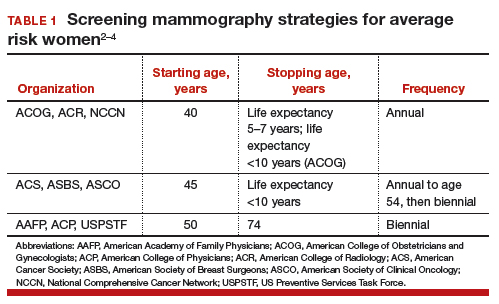

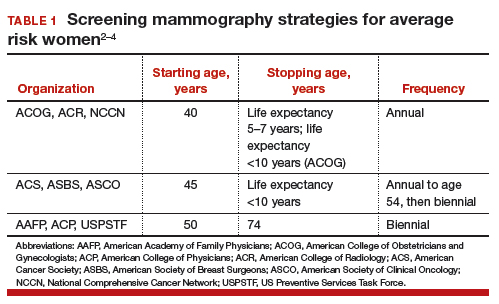

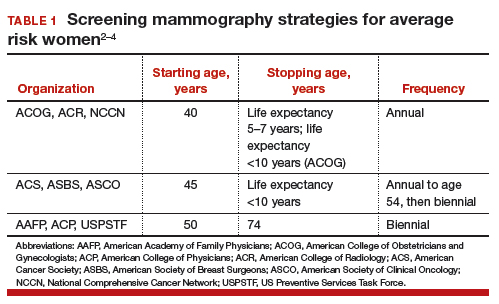

Controversy continues, however, on when to start mammography screening, when to stop screening, and the frequency with which screening should be performed for women at average risk for breast cancer. Indeed, 3 national recommendations—written by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Cancer Society (ACS), and the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)—offer different guidelines for mammography screening (TABLE 1).2–4

There are 2 principal reasons for the controversy over screening:

- mammography has both benefits and harms, and individuals place differential weight on the importance of these relative to each other

- randomized controlled trials on screening mammography did not include all of the starting age, stopping age, and screening intervals that are included in screening recommendations.

New comparison of recommendations

An ongoing project funded by the National Cancer Institute, known as the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET), models different starting and stopping ages and screening intervals for mammography to assess their impact on both benefits (mortality improvement, life-years gained) and harms (callbacks, benign breast biopsies). Recently, Arleo and colleagues used CISNET model data to compare the breast cancer screening recommendations from ACOG, the ACS, and the USPSTF, focusing on the differential effect on benefits and harms.5

Benefits vs harms of screening in perspective

Without question, the principal goal of cancer screening strategies is to effectively and efficiently reduce cancer mortality. Because mammography screening has both benefits and harms, a clear understanding of the relative frequency of these events among the different screening recommendations should be an important element in patient counseling.

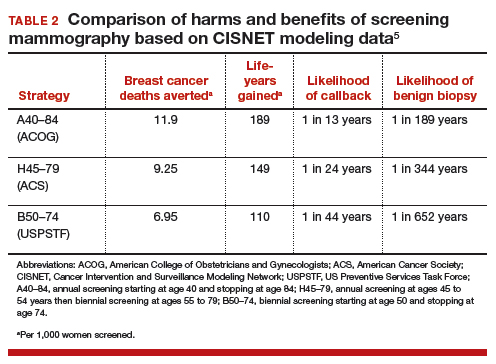

Based on CISNET-modeled estimates, TABLE 2, illustrates the differences in both benefits and harms of the 3 screening strategies. With all strategies, there is a clear benefit in both fewer breast cancer–related deaths and life-years gained per 1,000 women screened.

The greatest benefit is seen in the A40–84 group, that is, women who undergo the most intensive screening strategy with annual screening starting at age 40 and ending at age 84 (ACOG) compared with the USPSTF’s least intensive screening strategy, B50–74, which includes biennial screening starting at age 50 and stopping at age 74; benefits of the ACS’s H45–79 strategy (annual screening at ages 45 to 54 years then biennial screening at ages 55 to 79) were in-between. Not surprisingly, the A40–84 screening strategy was also associated with the most harms, with more recalls and benign breast biopsies; the least harms occurred with the USPSTF strategy, with the ACS strategy again in-between in terms of harms.

Related articles:

Breast density and optimal screening for breast cancer

To further demonstrate differences between the 3 strategies, CISNET also modeled results by looking at all women born in a single birth year cohort (1960) who were still alive at age 40 (2.468 million women). The modeling estimates the number of women who would die from breast cancer without screening mammography and compares that with the number of women who would die from breast cancer using any of the 3 screening strategies. Using this 1960 birth year cohort analysis, there would be approximately 12,000 fewer breast cancer deaths using the ACOG-recommended screening strategy compared with the USPSTF-recommended approach.4

These data show that while there are more harms associated with the most intense screening recommendation, the less frequent screening recommendations will result in higher mortality and more life-years lost. It is reasonable to assume that most patients would value mortality reduction and life-years gained over a likelihood of more benign biopsies or callbacks. As a result, each of the guidelines recommends that by age 40, women at average risk for breast cancer should be counseled and offered mammography screening based on their personal values.

Read about how Dr. Pearlman counsels his patients on screening.

My counseling approach on screening

Notably, the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative recommends that average risk women initiate mammography screening no earlier than age 40 and no later than age 50.6 This creates more flexibility around starting time for screening. In the population of women that I personally counsel, we discuss that fewer women (1 in 68) will experience breast cancer in their 40s compared with in their 50s (1 in 43); therefore as a population, more women will benefit from screening mammography in their 50s. However, there is clear evidence of mortality benefit for a woman in either decade should she develop breast cancer.

We also discuss that the frequency of harms is fairly comparable in either decade, but women who choose to start screening at age 50 will obviously not experience any callbacks or screening-associated benign breast biopsies in their 40s. With this understanding of benefits and harms, most (but not all) average risk women in my practice choose to start screening at age 40.

Related articles:

Breast cancer screening: My practices and response to the USPSTF guidelines

Be mindful of study limitations

The study by Arleo and colleagues has several weaknesses.5

Simulation studies/computer models have limitations. They are only as accurate as the assumptions that are used in the model. However, CISNET modeling has the benefit of having 6 different models with different assumptions on mortality, efficacy of mammography, and efficacy of treatment, and Arleo and colleagues’ analysis takes the mean of these 6 different models.5 It is reassuring to know that the modeling results are consistent with virtually all studies that show that annual screening mammography has a mortality benefit for women in their 40s.

Cost differences are not included. The actual cost of differences between the strategies is difficult to calculate and was not analyzed in this study. While it is easy to calculate the “front end” costs in a study like this (for example, how many more mammograms or biopsies in the different strategies), it is very difficult to calculate the “back end” costs (such as avoided chemotherapy or end-of-life care).

Overtreatment and overdiagnosis have been discussed extensively with regard to the different screening strategies. For example, approximately 80% of women with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) have these tumors detected on screening mammography, and DCIS is not an obligate precursor to invasive breast cancer. Because the natural history of DCIS cannot be predicted, treatment is recommended for all women with DCIS, even though many of these tumors will remain indolent and never cause harm. As a result, concerns have been raised that more intensive screening strategies may result in more overdiagnosis and overtreatment compared with less intensive strategies.

Increasingly, this argument has been questioned, since the prevailing thought is that DCIS does not regress or disappear on mammography. In other words, if DCIS is present at age 40, it will be detected whenever screening starts (age 40, 45, or 50), and age of starting screening or the screening interval will not impact overdiagnosis or overtreatment.7

Related articles:

More than one-third of tumors found on breast cancer screening represent overdiagnosis

Counsel patients, offer screening at age 40

While 3 different breast cancer mammography screening strategies are recommended in the United States, the study by Arleo and colleagues suggests that based on CISNET data, the A40–84 strategy appears to be the most effective at reducing breast cancer mortality and resulting in the most life-years gained. This strategy also requires the most lifetime mammograms and results in the most callbacks and benign biopsies. Women should be offered annual screening mammography starting at age 40 and should start no later than age 50 after receiving counseling about benefits and harms.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Cancer Facts & Figures 2017. American Cancer Society website. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2017/cancer-facts-and-figures-2017.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2017.

- Oeffinger KC, Frontham ET, Etzioni R, et al; American Cancer Society. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1599–1614.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 179: Breast cancer risk assessment and screening in average risk women. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):e1–e16.

- Siu AL; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(4):279–296.

- Arleo EK, Hendrick RE, Helvie MA, Sickles EA. Comparison of recommendations for screening mammography using CISNET models. Cancer. 2017;123(19):3673–3680.

- Women’s Preventive Services Initiative. Breast cancer screening for average-risk women. https://www.womenspreventivehealth.org/recommendations/breast-cancer-screening-for-average-risk-women/. Published 2016. Accessed October 4, 2017.

- Arleo EK, Monticciolo DL, Monsees B, McGinty G, Sickles EA. Persistent untreated screening-detected breast cancer: an argument against delaying screening or increasing the interval between screenings. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14(7):863–867.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death in women in the United States, with an estimated 252,710 new cases and 40,610 deaths in 2017.1 Breast cancer mortality is prevented by the use of regular screening mammography, as demonstrated by randomized controlled trials (20% reduction), incidence-based mortality studies (38% to 40% reduction), and service screening studies (48% to 49% reduction).2

Controversy continues, however, on when to start mammography screening, when to stop screening, and the frequency with which screening should be performed for women at average risk for breast cancer. Indeed, 3 national recommendations—written by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Cancer Society (ACS), and the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)—offer different guidelines for mammography screening (TABLE 1).2–4

There are 2 principal reasons for the controversy over screening:

- mammography has both benefits and harms, and individuals place differential weight on the importance of these relative to each other

- randomized controlled trials on screening mammography did not include all of the starting age, stopping age, and screening intervals that are included in screening recommendations.

New comparison of recommendations

An ongoing project funded by the National Cancer Institute, known as the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET), models different starting and stopping ages and screening intervals for mammography to assess their impact on both benefits (mortality improvement, life-years gained) and harms (callbacks, benign breast biopsies). Recently, Arleo and colleagues used CISNET model data to compare the breast cancer screening recommendations from ACOG, the ACS, and the USPSTF, focusing on the differential effect on benefits and harms.5

Benefits vs harms of screening in perspective

Without question, the principal goal of cancer screening strategies is to effectively and efficiently reduce cancer mortality. Because mammography screening has both benefits and harms, a clear understanding of the relative frequency of these events among the different screening recommendations should be an important element in patient counseling.

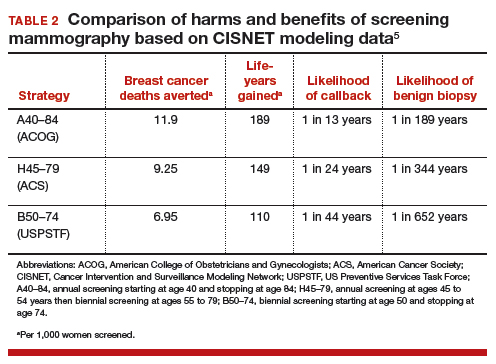

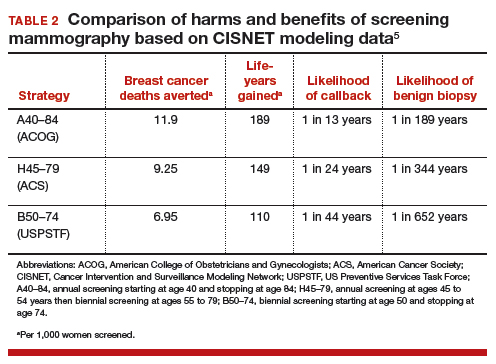

Based on CISNET-modeled estimates, TABLE 2, illustrates the differences in both benefits and harms of the 3 screening strategies. With all strategies, there is a clear benefit in both fewer breast cancer–related deaths and life-years gained per 1,000 women screened.

The greatest benefit is seen in the A40–84 group, that is, women who undergo the most intensive screening strategy with annual screening starting at age 40 and ending at age 84 (ACOG) compared with the USPSTF’s least intensive screening strategy, B50–74, which includes biennial screening starting at age 50 and stopping at age 74; benefits of the ACS’s H45–79 strategy (annual screening at ages 45 to 54 years then biennial screening at ages 55 to 79) were in-between. Not surprisingly, the A40–84 screening strategy was also associated with the most harms, with more recalls and benign breast biopsies; the least harms occurred with the USPSTF strategy, with the ACS strategy again in-between in terms of harms.

Related articles:

Breast density and optimal screening for breast cancer

To further demonstrate differences between the 3 strategies, CISNET also modeled results by looking at all women born in a single birth year cohort (1960) who were still alive at age 40 (2.468 million women). The modeling estimates the number of women who would die from breast cancer without screening mammography and compares that with the number of women who would die from breast cancer using any of the 3 screening strategies. Using this 1960 birth year cohort analysis, there would be approximately 12,000 fewer breast cancer deaths using the ACOG-recommended screening strategy compared with the USPSTF-recommended approach.4

These data show that while there are more harms associated with the most intense screening recommendation, the less frequent screening recommendations will result in higher mortality and more life-years lost. It is reasonable to assume that most patients would value mortality reduction and life-years gained over a likelihood of more benign biopsies or callbacks. As a result, each of the guidelines recommends that by age 40, women at average risk for breast cancer should be counseled and offered mammography screening based on their personal values.

Read about how Dr. Pearlman counsels his patients on screening.

My counseling approach on screening

Notably, the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative recommends that average risk women initiate mammography screening no earlier than age 40 and no later than age 50.6 This creates more flexibility around starting time for screening. In the population of women that I personally counsel, we discuss that fewer women (1 in 68) will experience breast cancer in their 40s compared with in their 50s (1 in 43); therefore as a population, more women will benefit from screening mammography in their 50s. However, there is clear evidence of mortality benefit for a woman in either decade should she develop breast cancer.

We also discuss that the frequency of harms is fairly comparable in either decade, but women who choose to start screening at age 50 will obviously not experience any callbacks or screening-associated benign breast biopsies in their 40s. With this understanding of benefits and harms, most (but not all) average risk women in my practice choose to start screening at age 40.

Related articles:

Breast cancer screening: My practices and response to the USPSTF guidelines

Be mindful of study limitations

The study by Arleo and colleagues has several weaknesses.5

Simulation studies/computer models have limitations. They are only as accurate as the assumptions that are used in the model. However, CISNET modeling has the benefit of having 6 different models with different assumptions on mortality, efficacy of mammography, and efficacy of treatment, and Arleo and colleagues’ analysis takes the mean of these 6 different models.5 It is reassuring to know that the modeling results are consistent with virtually all studies that show that annual screening mammography has a mortality benefit for women in their 40s.

Cost differences are not included. The actual cost of differences between the strategies is difficult to calculate and was not analyzed in this study. While it is easy to calculate the “front end” costs in a study like this (for example, how many more mammograms or biopsies in the different strategies), it is very difficult to calculate the “back end” costs (such as avoided chemotherapy or end-of-life care).

Overtreatment and overdiagnosis have been discussed extensively with regard to the different screening strategies. For example, approximately 80% of women with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) have these tumors detected on screening mammography, and DCIS is not an obligate precursor to invasive breast cancer. Because the natural history of DCIS cannot be predicted, treatment is recommended for all women with DCIS, even though many of these tumors will remain indolent and never cause harm. As a result, concerns have been raised that more intensive screening strategies may result in more overdiagnosis and overtreatment compared with less intensive strategies.

Increasingly, this argument has been questioned, since the prevailing thought is that DCIS does not regress or disappear on mammography. In other words, if DCIS is present at age 40, it will be detected whenever screening starts (age 40, 45, or 50), and age of starting screening or the screening interval will not impact overdiagnosis or overtreatment.7

Related articles:

More than one-third of tumors found on breast cancer screening represent overdiagnosis

Counsel patients, offer screening at age 40

While 3 different breast cancer mammography screening strategies are recommended in the United States, the study by Arleo and colleagues suggests that based on CISNET data, the A40–84 strategy appears to be the most effective at reducing breast cancer mortality and resulting in the most life-years gained. This strategy also requires the most lifetime mammograms and results in the most callbacks and benign biopsies. Women should be offered annual screening mammography starting at age 40 and should start no later than age 50 after receiving counseling about benefits and harms.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer and the second leading cause of cancer death in women in the United States, with an estimated 252,710 new cases and 40,610 deaths in 2017.1 Breast cancer mortality is prevented by the use of regular screening mammography, as demonstrated by randomized controlled trials (20% reduction), incidence-based mortality studies (38% to 40% reduction), and service screening studies (48% to 49% reduction).2

Controversy continues, however, on when to start mammography screening, when to stop screening, and the frequency with which screening should be performed for women at average risk for breast cancer. Indeed, 3 national recommendations—written by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Cancer Society (ACS), and the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)—offer different guidelines for mammography screening (TABLE 1).2–4

There are 2 principal reasons for the controversy over screening:

- mammography has both benefits and harms, and individuals place differential weight on the importance of these relative to each other

- randomized controlled trials on screening mammography did not include all of the starting age, stopping age, and screening intervals that are included in screening recommendations.

New comparison of recommendations

An ongoing project funded by the National Cancer Institute, known as the Cancer Intervention and Surveillance Modeling Network (CISNET), models different starting and stopping ages and screening intervals for mammography to assess their impact on both benefits (mortality improvement, life-years gained) and harms (callbacks, benign breast biopsies). Recently, Arleo and colleagues used CISNET model data to compare the breast cancer screening recommendations from ACOG, the ACS, and the USPSTF, focusing on the differential effect on benefits and harms.5

Benefits vs harms of screening in perspective

Without question, the principal goal of cancer screening strategies is to effectively and efficiently reduce cancer mortality. Because mammography screening has both benefits and harms, a clear understanding of the relative frequency of these events among the different screening recommendations should be an important element in patient counseling.

Based on CISNET-modeled estimates, TABLE 2, illustrates the differences in both benefits and harms of the 3 screening strategies. With all strategies, there is a clear benefit in both fewer breast cancer–related deaths and life-years gained per 1,000 women screened.

The greatest benefit is seen in the A40–84 group, that is, women who undergo the most intensive screening strategy with annual screening starting at age 40 and ending at age 84 (ACOG) compared with the USPSTF’s least intensive screening strategy, B50–74, which includes biennial screening starting at age 50 and stopping at age 74; benefits of the ACS’s H45–79 strategy (annual screening at ages 45 to 54 years then biennial screening at ages 55 to 79) were in-between. Not surprisingly, the A40–84 screening strategy was also associated with the most harms, with more recalls and benign breast biopsies; the least harms occurred with the USPSTF strategy, with the ACS strategy again in-between in terms of harms.

Related articles:

Breast density and optimal screening for breast cancer

To further demonstrate differences between the 3 strategies, CISNET also modeled results by looking at all women born in a single birth year cohort (1960) who were still alive at age 40 (2.468 million women). The modeling estimates the number of women who would die from breast cancer without screening mammography and compares that with the number of women who would die from breast cancer using any of the 3 screening strategies. Using this 1960 birth year cohort analysis, there would be approximately 12,000 fewer breast cancer deaths using the ACOG-recommended screening strategy compared with the USPSTF-recommended approach.4

These data show that while there are more harms associated with the most intense screening recommendation, the less frequent screening recommendations will result in higher mortality and more life-years lost. It is reasonable to assume that most patients would value mortality reduction and life-years gained over a likelihood of more benign biopsies or callbacks. As a result, each of the guidelines recommends that by age 40, women at average risk for breast cancer should be counseled and offered mammography screening based on their personal values.

Read about how Dr. Pearlman counsels his patients on screening.

My counseling approach on screening

Notably, the Women’s Preventive Services Initiative recommends that average risk women initiate mammography screening no earlier than age 40 and no later than age 50.6 This creates more flexibility around starting time for screening. In the population of women that I personally counsel, we discuss that fewer women (1 in 68) will experience breast cancer in their 40s compared with in their 50s (1 in 43); therefore as a population, more women will benefit from screening mammography in their 50s. However, there is clear evidence of mortality benefit for a woman in either decade should she develop breast cancer.

We also discuss that the frequency of harms is fairly comparable in either decade, but women who choose to start screening at age 50 will obviously not experience any callbacks or screening-associated benign breast biopsies in their 40s. With this understanding of benefits and harms, most (but not all) average risk women in my practice choose to start screening at age 40.

Related articles:

Breast cancer screening: My practices and response to the USPSTF guidelines

Be mindful of study limitations

The study by Arleo and colleagues has several weaknesses.5

Simulation studies/computer models have limitations. They are only as accurate as the assumptions that are used in the model. However, CISNET modeling has the benefit of having 6 different models with different assumptions on mortality, efficacy of mammography, and efficacy of treatment, and Arleo and colleagues’ analysis takes the mean of these 6 different models.5 It is reassuring to know that the modeling results are consistent with virtually all studies that show that annual screening mammography has a mortality benefit for women in their 40s.

Cost differences are not included. The actual cost of differences between the strategies is difficult to calculate and was not analyzed in this study. While it is easy to calculate the “front end” costs in a study like this (for example, how many more mammograms or biopsies in the different strategies), it is very difficult to calculate the “back end” costs (such as avoided chemotherapy or end-of-life care).

Overtreatment and overdiagnosis have been discussed extensively with regard to the different screening strategies. For example, approximately 80% of women with ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) have these tumors detected on screening mammography, and DCIS is not an obligate precursor to invasive breast cancer. Because the natural history of DCIS cannot be predicted, treatment is recommended for all women with DCIS, even though many of these tumors will remain indolent and never cause harm. As a result, concerns have been raised that more intensive screening strategies may result in more overdiagnosis and overtreatment compared with less intensive strategies.

Increasingly, this argument has been questioned, since the prevailing thought is that DCIS does not regress or disappear on mammography. In other words, if DCIS is present at age 40, it will be detected whenever screening starts (age 40, 45, or 50), and age of starting screening or the screening interval will not impact overdiagnosis or overtreatment.7

Related articles:

More than one-third of tumors found on breast cancer screening represent overdiagnosis

Counsel patients, offer screening at age 40

While 3 different breast cancer mammography screening strategies are recommended in the United States, the study by Arleo and colleagues suggests that based on CISNET data, the A40–84 strategy appears to be the most effective at reducing breast cancer mortality and resulting in the most life-years gained. This strategy also requires the most lifetime mammograms and results in the most callbacks and benign biopsies. Women should be offered annual screening mammography starting at age 40 and should start no later than age 50 after receiving counseling about benefits and harms.

Share your thoughts! Send your Letter to the Editor to [email protected]. Please include your name and the city and state in which you practice.

- Cancer Facts & Figures 2017. American Cancer Society website. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2017/cancer-facts-and-figures-2017.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2017.

- Oeffinger KC, Frontham ET, Etzioni R, et al; American Cancer Society. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1599–1614.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 179: Breast cancer risk assessment and screening in average risk women. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):e1–e16.

- Siu AL; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(4):279–296.

- Arleo EK, Hendrick RE, Helvie MA, Sickles EA. Comparison of recommendations for screening mammography using CISNET models. Cancer. 2017;123(19):3673–3680.

- Women’s Preventive Services Initiative. Breast cancer screening for average-risk women. https://www.womenspreventivehealth.org/recommendations/breast-cancer-screening-for-average-risk-women/. Published 2016. Accessed October 4, 2017.

- Arleo EK, Monticciolo DL, Monsees B, McGinty G, Sickles EA. Persistent untreated screening-detected breast cancer: an argument against delaying screening or increasing the interval between screenings. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14(7):863–867.

- Cancer Facts & Figures 2017. American Cancer Society website. https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2017/cancer-facts-and-figures-2017.pdf. Accessed October 4, 2017.

- Oeffinger KC, Frontham ET, Etzioni R, et al; American Cancer Society. Breast cancer screening for women at average risk: 2015 guideline update from the American Cancer Society. JAMA. 2015;314(15):1599–1614.

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee on Practice Bulletins–Gynecology. ACOG Practice Bulletin No. 179: Breast cancer risk assessment and screening in average risk women. Obstet Gynecol. 2017;130(1):e1–e16.

- Siu AL; US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for breast cancer: US Preventive Services Task Force recommendation statement. Ann Intern Med. 2016;164(4):279–296.

- Arleo EK, Hendrick RE, Helvie MA, Sickles EA. Comparison of recommendations for screening mammography using CISNET models. Cancer. 2017;123(19):3673–3680.

- Women’s Preventive Services Initiative. Breast cancer screening for average-risk women. https://www.womenspreventivehealth.org/recommendations/breast-cancer-screening-for-average-risk-women/. Published 2016. Accessed October 4, 2017.

- Arleo EK, Monticciolo DL, Monsees B, McGinty G, Sickles EA. Persistent untreated screening-detected breast cancer: an argument against delaying screening or increasing the interval between screenings. J Am Coll Radiol. 2017;14(7):863–867.