User login

- The true origin of the heel pain of calcaneal apophysitis is a stress microfracture (invisible on x-ray) due to chronic repetitive microtrauma—it’s an overuse syndrome that resolves without surgery in nearly all cases. (C)

- Most patients experience pain relief and can resume full activities while using a simple in-shoe wedge-shaped orthotic. (C)

- The most distinguishing feature on physical exam is the exquisite heel pain produced by lateral and medial compression (“squeezing”) of the heel. (C)

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

- Good quality patient-oriented evidence

- Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

- Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

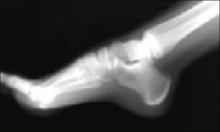

Two things about calcaneal “apophysitis” are a bit misleading. The first is its name. Although this common cause of heel pain in adolescents and teenagers was once considered a true osteochondritis, we now know that it’s actually a mechanical overuse pain syndrome with a self-limited, benign prognosis.1-3 The second area of confusion is what you’ll see on x-ray: an increased density and irregular fragmentation that was once viewed with suspicion, but is actually a normal pattern of ossification for this particular apophysis.

Don’t let the x-ray fool you

Primary care physicians can properly manage this common pain condition, given an understanding of the features, natural history, and treatment principles presented here.

Orthopedic referral is indicated for only a few recalcitrant cases.

Shoes aren’t to blame, but activity level is

Adolescents with calcaneal apophysitis—also known as Sever’s disease—will typically come into the office complaining of pain, often in both heels, particularly with mechanical activities such as running, jumping, and long-distance walking. Patients may walk on tiptoe to avoid the pain.4

The condition is common in both boys and girls, although personal experience indicates it’s more common in boys. The typical age of the patient is 8 to 15 years. The condition is most commonly seen in patients who are engaged in athletic endeavors,5,6 including soccer, basketball, and gymnastics,7,8 though no specific athletic endeavor has been directly implicated in the pathogenesis. Likewise, no specific foot structure or type of shoe wear has been directly related to the symptomatology.

An otherwise healthy boy, age 12, walks into your office—on tiptoe. His problem is pain in both heels, especially when running. It’s his first season on his school track team, and he says he’s been practicing hard for the 50-yard dash, “my best event.” his parents express to you their concern about possible sports-related injuries or underlying disease, and their son’s distress about the possibilty of “letting down the team” if he quits. You find no swelling, no skin changes, no erythema, and no other local abnormalities. Symptoms of marked pain are produced by medial and lateral compression (squeezing) of the heel at the site where the calcaneal apophysis attaches to the main body of the os calcis. There is no pain on plantar, posterior, or retrocalcaneal pressure, or adjacent to the Achilles tendon.

Exquisite heel pain produced by medial and lateral compression of the heel is the most distinguishing feature of calcaneal apophysitis

Is this x-ray normal? You order a lateral x-ray of the calcaneus to exclude other pathology. You observe a pattern of increased density and apparent irregular fragmentation on the x-ray. The radiologist reports no abnormal findings. The above x-ray typifies calcaneal apophysitis, an overuse syndrome often seen in children 8 to 15 years of age. The “dense” area is actually a secondary ossification center of the calcaneus, not an indication of pathology.

The ossification of the calcaneus is different from that of the tarsal bones, which are each ossified from a single center. In the case of the calcaneus, a secondary center of ossification typically appears in girls by age 6, and in boys by age 8.14,15 During adolescence, a C-shaped cartilage develops between the metaphyseal bone of the body of the calcaneus and the secondary center (or centers) of ossification. Then, at around age 10 or 11, a more superior tertiary ossification center appears in the apophysis of the calcaneus.

As the calcaneal apophysis progressively ossifies, it presents as a very dense radiographic pattern in an adolescent. For years, this was thought to represent a form of osteochondritis.16 In fact, this is a normal pattern of ossification for this particular apophysis.17-22

What do you tell the patient and parents? You advise an in-shoe orthotic, no limits on physical activity, and no surgery. You explain that the pain is due to recurrent impact (overuse), and that the orthotic will “unload” the heel and permit symtoms to resolve, typically within 60 days. If asked about discomfort, you may advise anti-inflammatories and ice/heat.

Patients typically have no swelling, skin changes, erythema, or other local abnormalities.8 The most characteristic distinguishing feature on physical examination is exquisite pain produced on medial and lateral compression (“squeezing”) of the heel at the site where the calcaneal apophysis attaches to the main body of the os calcis. The pain is not on plantar pressure (as you would see with plantar fasciitis), or posterior, retrocalcaneal, or adjacent to the Achilles tendon (as you would see on Achilles tendinitis), but on medial and lateral compression.3

I’ve noticed a number of trends over the years while caring for patients with calcaneal apophysitis. My chart review of the 227 patients I cared for between 1971 and 1997 revealed the following:

- 60% (137) of patients had bilateral involvement.

- 78% of the patients were male. The reason for the male preponderance remains unclear.

- All but 3 of the 364 feet obtained eventual complete symptom resolution with the prescribed sponge-leather heel orthotic.

- Symptoms typically resolved within 60 days.

- The 3 cases that were recalcitrant to orthotic treatment required an equinus-type cast for 4 to 6 weeks. Those patients treated with a cast also had resolution of their symptoms.

- Roughly 30% of the cases encountered a recurrence of symptoms with similar resolution with the previously described retreatment. Recurrences were unrelated to gender.

- No case ever required any other treatment type beyond the orthotic or cast.—Dennis Weiner, MD

Researchers found microfractures. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evidence suggests that the true pathogenesis of calcaneal apophysitis is a stress microfracture related to chronic repetitive microtrauma.9 In addition, MRI evidence suggests that the location of the stress microfractures is in the metaphysis of the body of the calcaneus adjacent to—but not directly involving—the apophysis.1,7 This more recent evidence replaces the historical hypotheses that the condition is primarily an inflammatory process. As a consequence of the microtrauma, however, it’s possible that an inflammatory process may occur secondarily.

Should you order x-rays? X-rays are not essential to the diagnosis, though they may be used to rule out other conditions, such as fracture, infection, or a bone cyst. Keep in mind, though, that patients with calcaneal pain will have a normal x-ray.7 What is normal, however, is another matter, and has been the subject of confusion in the past.

Pain stops in a few weeks

Usually, the symptoms of calcaneal apophysitis resolve fairly quickly, and with relatively simple treatment. (The symptoms also disappear as the child gets older and the calcaneal apophysis amalgamates with the main body of the calcaneus.)

Physiotherapy, forced ankle dorsiflexion stretching, gastrocsoleus stretching, ice, heat, heel cups and pads,1,10-13 and anti-inflammatories have all been used in the management of the condition.3,8 Clinicians have also historically restricted the patients’ activity, but this is unnecessary.

An in-shoe soft orthotic is helpful in treating calcaneal apophysitis. The prescription that the lead author writes is for a ⅝″ compressible, sponge-filled leather orthotic that is made in the form of a heel wedge or heel pad. Pain relief is believed to occur as a result of relaxation of the tension on the gastrocsoleus complex inserting onto the calcaneal apophysis and by “cushioning” the impact of heel strike.3 The orthotic, which typically lasts for 3 to 6 months, generally abrogates the need for anti-inflammatories as a primary treatment. However, relief of discomfort during this period may include use of antiflammatories.

For many years, the lead author has utilized a simple in-shoe, wedge-shaped orthotic consisting of a sponge material covered by leather, and compressible down to ⅝″. It raises the heel and cushions the impact of weightbearing. It can be transferred from shoe to shoe, and the patient can resume full activities while wearing the orthotic. Pain relief is generally achieved within 6 weeks to 3 months. Recalcitrant cases may require a 4 to 6 week period of casting in a plantar flexed position. Surgery is not necessary, nor are there any surgical cases reported in the literature. Orthopaedic referral is indicated for recalcitrant cases.

Acknowledgments

The Audio-Visual Department, Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Akron and Adeline Weiner assisted in preparing this paper.

Correspondence

Dennis S. Weiner, MD, 300 Locust Street, Suite 160, Akron, OH 44302-1821. [email protected]

1. Ogden J. Skeletal Injury in the Child. 3rd ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2000:1118–1120.

2. Orava S, Virtanen K. Osteochondroses in athletes. Br J Sports Med 1982;16:161-168.

3. Weiner DS. Pediatric Orthopedics for Primary Care Physicians. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004.

4. Ishikawa SN. Conditions of the calcaneus in skeletally immature patients. Foot Ankle Clin N Am 2005;10:503-513.

5. Allison N. Apophysitis of the os calcis. J Bone Joint Surg 1924;6:91-94.

6. Brantigan CO. Calcaneal apophysitis. One of the growing pains of adolescence. Rocky Mt Med J 1972;69(8):59-60.

7. Ogden J, Ganey T, Hill JD, Jaakkola JI. Sever’s injury: a stress fracture of the immature calcaneal metaphysis. J Pediatr Orthop 2004;24:488-492.

8. Micheli LJ, Ireland LM. Prevention and management of calcaneal apophysitis in children; an overuse syndrome. J Pediatr Orthop 1987;7:34-38.

9. Liberson A, Lieberson S, Mendes DG, Shajrawi I, Ben Haim Y, Boss JH. Remodeling of the calcaneus apophysis in the growing child. J Pediatr Orthop 1995;4:74-79.

10. Contompasis JP. The management of heel pain in the athlete. Clin Podiatr Med Surg 1986;3:705-711.

11. McKenzie DC, Taunton JE, Clement DB, Smart GW, McNicol KL. Calcaneal epiphysitis in adolescent athletes. Can J Appl Sport Sci 1981;6:123-125.

12. Madden C, Mellion M. Sever’s disease and other causes of heel pain in adolescents. Am Fam Physician 1996;54:1995-2000.

13. Meyerding HW, Stuck WG. Painful heels among children (apophysitis). JAMA 1934;102:1658-1660.

14. Rhine I, Locke R. Apophysitis of the calcaneus. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1952;51:441-447.

15. Ross SE, Caffey J. Ossification of the calcaneal apophysis in healthy children. Stanford Med Bull 1957;15:224-226.

16. Sever JW. Apophysitis of the os calcis. NY State J Med 1912;95:1025-1029.

17. Volpon JB, de Carvalho Filho G. Calcaneal apophysitis a quantitative radiographic evaluation of the secondary ossification center. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2002;122:338-341.

18. Hughes ASR. Painful heels in children. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1948;86:64-68.

19. Kohler A, Zimmer EA. Borderlands of the Normal and Early Pathologic and Skeletal Roentgenology. 3rd ed. New York: Grune and Stratton; 1968.

20. Shopfner CE, Coin CG. Effect of weightbearing on the appearance and development of the secondary calcaneal epiphysis. Radiology 1966;86:201-206.

21. Krantz MK. Calcaneal apophysitis a clinical and roentgenologic study. J Am Podiatry Assoc 1965;55:801-807.

22. Lerner LH. Radiographic evaluation of calcaneal apophysitis. J Natl Assoc Chiropodists 1957;47:451-459.

- The true origin of the heel pain of calcaneal apophysitis is a stress microfracture (invisible on x-ray) due to chronic repetitive microtrauma—it’s an overuse syndrome that resolves without surgery in nearly all cases. (C)

- Most patients experience pain relief and can resume full activities while using a simple in-shoe wedge-shaped orthotic. (C)

- The most distinguishing feature on physical exam is the exquisite heel pain produced by lateral and medial compression (“squeezing”) of the heel. (C)

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

- Good quality patient-oriented evidence

- Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

- Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Two things about calcaneal “apophysitis” are a bit misleading. The first is its name. Although this common cause of heel pain in adolescents and teenagers was once considered a true osteochondritis, we now know that it’s actually a mechanical overuse pain syndrome with a self-limited, benign prognosis.1-3 The second area of confusion is what you’ll see on x-ray: an increased density and irregular fragmentation that was once viewed with suspicion, but is actually a normal pattern of ossification for this particular apophysis.

Don’t let the x-ray fool you

Primary care physicians can properly manage this common pain condition, given an understanding of the features, natural history, and treatment principles presented here.

Orthopedic referral is indicated for only a few recalcitrant cases.

Shoes aren’t to blame, but activity level is

Adolescents with calcaneal apophysitis—also known as Sever’s disease—will typically come into the office complaining of pain, often in both heels, particularly with mechanical activities such as running, jumping, and long-distance walking. Patients may walk on tiptoe to avoid the pain.4

The condition is common in both boys and girls, although personal experience indicates it’s more common in boys. The typical age of the patient is 8 to 15 years. The condition is most commonly seen in patients who are engaged in athletic endeavors,5,6 including soccer, basketball, and gymnastics,7,8 though no specific athletic endeavor has been directly implicated in the pathogenesis. Likewise, no specific foot structure or type of shoe wear has been directly related to the symptomatology.

An otherwise healthy boy, age 12, walks into your office—on tiptoe. His problem is pain in both heels, especially when running. It’s his first season on his school track team, and he says he’s been practicing hard for the 50-yard dash, “my best event.” his parents express to you their concern about possible sports-related injuries or underlying disease, and their son’s distress about the possibilty of “letting down the team” if he quits. You find no swelling, no skin changes, no erythema, and no other local abnormalities. Symptoms of marked pain are produced by medial and lateral compression (squeezing) of the heel at the site where the calcaneal apophysis attaches to the main body of the os calcis. There is no pain on plantar, posterior, or retrocalcaneal pressure, or adjacent to the Achilles tendon.

Exquisite heel pain produced by medial and lateral compression of the heel is the most distinguishing feature of calcaneal apophysitis

Is this x-ray normal? You order a lateral x-ray of the calcaneus to exclude other pathology. You observe a pattern of increased density and apparent irregular fragmentation on the x-ray. The radiologist reports no abnormal findings. The above x-ray typifies calcaneal apophysitis, an overuse syndrome often seen in children 8 to 15 years of age. The “dense” area is actually a secondary ossification center of the calcaneus, not an indication of pathology.

The ossification of the calcaneus is different from that of the tarsal bones, which are each ossified from a single center. In the case of the calcaneus, a secondary center of ossification typically appears in girls by age 6, and in boys by age 8.14,15 During adolescence, a C-shaped cartilage develops between the metaphyseal bone of the body of the calcaneus and the secondary center (or centers) of ossification. Then, at around age 10 or 11, a more superior tertiary ossification center appears in the apophysis of the calcaneus.

As the calcaneal apophysis progressively ossifies, it presents as a very dense radiographic pattern in an adolescent. For years, this was thought to represent a form of osteochondritis.16 In fact, this is a normal pattern of ossification for this particular apophysis.17-22

What do you tell the patient and parents? You advise an in-shoe orthotic, no limits on physical activity, and no surgery. You explain that the pain is due to recurrent impact (overuse), and that the orthotic will “unload” the heel and permit symtoms to resolve, typically within 60 days. If asked about discomfort, you may advise anti-inflammatories and ice/heat.

Patients typically have no swelling, skin changes, erythema, or other local abnormalities.8 The most characteristic distinguishing feature on physical examination is exquisite pain produced on medial and lateral compression (“squeezing”) of the heel at the site where the calcaneal apophysis attaches to the main body of the os calcis. The pain is not on plantar pressure (as you would see with plantar fasciitis), or posterior, retrocalcaneal, or adjacent to the Achilles tendon (as you would see on Achilles tendinitis), but on medial and lateral compression.3

I’ve noticed a number of trends over the years while caring for patients with calcaneal apophysitis. My chart review of the 227 patients I cared for between 1971 and 1997 revealed the following:

- 60% (137) of patients had bilateral involvement.

- 78% of the patients were male. The reason for the male preponderance remains unclear.

- All but 3 of the 364 feet obtained eventual complete symptom resolution with the prescribed sponge-leather heel orthotic.

- Symptoms typically resolved within 60 days.

- The 3 cases that were recalcitrant to orthotic treatment required an equinus-type cast for 4 to 6 weeks. Those patients treated with a cast also had resolution of their symptoms.

- Roughly 30% of the cases encountered a recurrence of symptoms with similar resolution with the previously described retreatment. Recurrences were unrelated to gender.

- No case ever required any other treatment type beyond the orthotic or cast.—Dennis Weiner, MD

Researchers found microfractures. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evidence suggests that the true pathogenesis of calcaneal apophysitis is a stress microfracture related to chronic repetitive microtrauma.9 In addition, MRI evidence suggests that the location of the stress microfractures is in the metaphysis of the body of the calcaneus adjacent to—but not directly involving—the apophysis.1,7 This more recent evidence replaces the historical hypotheses that the condition is primarily an inflammatory process. As a consequence of the microtrauma, however, it’s possible that an inflammatory process may occur secondarily.

Should you order x-rays? X-rays are not essential to the diagnosis, though they may be used to rule out other conditions, such as fracture, infection, or a bone cyst. Keep in mind, though, that patients with calcaneal pain will have a normal x-ray.7 What is normal, however, is another matter, and has been the subject of confusion in the past.

Pain stops in a few weeks

Usually, the symptoms of calcaneal apophysitis resolve fairly quickly, and with relatively simple treatment. (The symptoms also disappear as the child gets older and the calcaneal apophysis amalgamates with the main body of the calcaneus.)

Physiotherapy, forced ankle dorsiflexion stretching, gastrocsoleus stretching, ice, heat, heel cups and pads,1,10-13 and anti-inflammatories have all been used in the management of the condition.3,8 Clinicians have also historically restricted the patients’ activity, but this is unnecessary.

An in-shoe soft orthotic is helpful in treating calcaneal apophysitis. The prescription that the lead author writes is for a ⅝″ compressible, sponge-filled leather orthotic that is made in the form of a heel wedge or heel pad. Pain relief is believed to occur as a result of relaxation of the tension on the gastrocsoleus complex inserting onto the calcaneal apophysis and by “cushioning” the impact of heel strike.3 The orthotic, which typically lasts for 3 to 6 months, generally abrogates the need for anti-inflammatories as a primary treatment. However, relief of discomfort during this period may include use of antiflammatories.

For many years, the lead author has utilized a simple in-shoe, wedge-shaped orthotic consisting of a sponge material covered by leather, and compressible down to ⅝″. It raises the heel and cushions the impact of weightbearing. It can be transferred from shoe to shoe, and the patient can resume full activities while wearing the orthotic. Pain relief is generally achieved within 6 weeks to 3 months. Recalcitrant cases may require a 4 to 6 week period of casting in a plantar flexed position. Surgery is not necessary, nor are there any surgical cases reported in the literature. Orthopaedic referral is indicated for recalcitrant cases.

Acknowledgments

The Audio-Visual Department, Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Akron and Adeline Weiner assisted in preparing this paper.

Correspondence

Dennis S. Weiner, MD, 300 Locust Street, Suite 160, Akron, OH 44302-1821. [email protected]

- The true origin of the heel pain of calcaneal apophysitis is a stress microfracture (invisible on x-ray) due to chronic repetitive microtrauma—it’s an overuse syndrome that resolves without surgery in nearly all cases. (C)

- Most patients experience pain relief and can resume full activities while using a simple in-shoe wedge-shaped orthotic. (C)

- The most distinguishing feature on physical exam is the exquisite heel pain produced by lateral and medial compression (“squeezing”) of the heel. (C)

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

- Good quality patient-oriented evidence

- Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

- Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

Two things about calcaneal “apophysitis” are a bit misleading. The first is its name. Although this common cause of heel pain in adolescents and teenagers was once considered a true osteochondritis, we now know that it’s actually a mechanical overuse pain syndrome with a self-limited, benign prognosis.1-3 The second area of confusion is what you’ll see on x-ray: an increased density and irregular fragmentation that was once viewed with suspicion, but is actually a normal pattern of ossification for this particular apophysis.

Don’t let the x-ray fool you

Primary care physicians can properly manage this common pain condition, given an understanding of the features, natural history, and treatment principles presented here.

Orthopedic referral is indicated for only a few recalcitrant cases.

Shoes aren’t to blame, but activity level is

Adolescents with calcaneal apophysitis—also known as Sever’s disease—will typically come into the office complaining of pain, often in both heels, particularly with mechanical activities such as running, jumping, and long-distance walking. Patients may walk on tiptoe to avoid the pain.4

The condition is common in both boys and girls, although personal experience indicates it’s more common in boys. The typical age of the patient is 8 to 15 years. The condition is most commonly seen in patients who are engaged in athletic endeavors,5,6 including soccer, basketball, and gymnastics,7,8 though no specific athletic endeavor has been directly implicated in the pathogenesis. Likewise, no specific foot structure or type of shoe wear has been directly related to the symptomatology.

An otherwise healthy boy, age 12, walks into your office—on tiptoe. His problem is pain in both heels, especially when running. It’s his first season on his school track team, and he says he’s been practicing hard for the 50-yard dash, “my best event.” his parents express to you their concern about possible sports-related injuries or underlying disease, and their son’s distress about the possibilty of “letting down the team” if he quits. You find no swelling, no skin changes, no erythema, and no other local abnormalities. Symptoms of marked pain are produced by medial and lateral compression (squeezing) of the heel at the site where the calcaneal apophysis attaches to the main body of the os calcis. There is no pain on plantar, posterior, or retrocalcaneal pressure, or adjacent to the Achilles tendon.

Exquisite heel pain produced by medial and lateral compression of the heel is the most distinguishing feature of calcaneal apophysitis

Is this x-ray normal? You order a lateral x-ray of the calcaneus to exclude other pathology. You observe a pattern of increased density and apparent irregular fragmentation on the x-ray. The radiologist reports no abnormal findings. The above x-ray typifies calcaneal apophysitis, an overuse syndrome often seen in children 8 to 15 years of age. The “dense” area is actually a secondary ossification center of the calcaneus, not an indication of pathology.

The ossification of the calcaneus is different from that of the tarsal bones, which are each ossified from a single center. In the case of the calcaneus, a secondary center of ossification typically appears in girls by age 6, and in boys by age 8.14,15 During adolescence, a C-shaped cartilage develops between the metaphyseal bone of the body of the calcaneus and the secondary center (or centers) of ossification. Then, at around age 10 or 11, a more superior tertiary ossification center appears in the apophysis of the calcaneus.

As the calcaneal apophysis progressively ossifies, it presents as a very dense radiographic pattern in an adolescent. For years, this was thought to represent a form of osteochondritis.16 In fact, this is a normal pattern of ossification for this particular apophysis.17-22

What do you tell the patient and parents? You advise an in-shoe orthotic, no limits on physical activity, and no surgery. You explain that the pain is due to recurrent impact (overuse), and that the orthotic will “unload” the heel and permit symtoms to resolve, typically within 60 days. If asked about discomfort, you may advise anti-inflammatories and ice/heat.

Patients typically have no swelling, skin changes, erythema, or other local abnormalities.8 The most characteristic distinguishing feature on physical examination is exquisite pain produced on medial and lateral compression (“squeezing”) of the heel at the site where the calcaneal apophysis attaches to the main body of the os calcis. The pain is not on plantar pressure (as you would see with plantar fasciitis), or posterior, retrocalcaneal, or adjacent to the Achilles tendon (as you would see on Achilles tendinitis), but on medial and lateral compression.3

I’ve noticed a number of trends over the years while caring for patients with calcaneal apophysitis. My chart review of the 227 patients I cared for between 1971 and 1997 revealed the following:

- 60% (137) of patients had bilateral involvement.

- 78% of the patients were male. The reason for the male preponderance remains unclear.

- All but 3 of the 364 feet obtained eventual complete symptom resolution with the prescribed sponge-leather heel orthotic.

- Symptoms typically resolved within 60 days.

- The 3 cases that were recalcitrant to orthotic treatment required an equinus-type cast for 4 to 6 weeks. Those patients treated with a cast also had resolution of their symptoms.

- Roughly 30% of the cases encountered a recurrence of symptoms with similar resolution with the previously described retreatment. Recurrences were unrelated to gender.

- No case ever required any other treatment type beyond the orthotic or cast.—Dennis Weiner, MD

Researchers found microfractures. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) evidence suggests that the true pathogenesis of calcaneal apophysitis is a stress microfracture related to chronic repetitive microtrauma.9 In addition, MRI evidence suggests that the location of the stress microfractures is in the metaphysis of the body of the calcaneus adjacent to—but not directly involving—the apophysis.1,7 This more recent evidence replaces the historical hypotheses that the condition is primarily an inflammatory process. As a consequence of the microtrauma, however, it’s possible that an inflammatory process may occur secondarily.

Should you order x-rays? X-rays are not essential to the diagnosis, though they may be used to rule out other conditions, such as fracture, infection, or a bone cyst. Keep in mind, though, that patients with calcaneal pain will have a normal x-ray.7 What is normal, however, is another matter, and has been the subject of confusion in the past.

Pain stops in a few weeks

Usually, the symptoms of calcaneal apophysitis resolve fairly quickly, and with relatively simple treatment. (The symptoms also disappear as the child gets older and the calcaneal apophysis amalgamates with the main body of the calcaneus.)

Physiotherapy, forced ankle dorsiflexion stretching, gastrocsoleus stretching, ice, heat, heel cups and pads,1,10-13 and anti-inflammatories have all been used in the management of the condition.3,8 Clinicians have also historically restricted the patients’ activity, but this is unnecessary.

An in-shoe soft orthotic is helpful in treating calcaneal apophysitis. The prescription that the lead author writes is for a ⅝″ compressible, sponge-filled leather orthotic that is made in the form of a heel wedge or heel pad. Pain relief is believed to occur as a result of relaxation of the tension on the gastrocsoleus complex inserting onto the calcaneal apophysis and by “cushioning” the impact of heel strike.3 The orthotic, which typically lasts for 3 to 6 months, generally abrogates the need for anti-inflammatories as a primary treatment. However, relief of discomfort during this period may include use of antiflammatories.

For many years, the lead author has utilized a simple in-shoe, wedge-shaped orthotic consisting of a sponge material covered by leather, and compressible down to ⅝″. It raises the heel and cushions the impact of weightbearing. It can be transferred from shoe to shoe, and the patient can resume full activities while wearing the orthotic. Pain relief is generally achieved within 6 weeks to 3 months. Recalcitrant cases may require a 4 to 6 week period of casting in a plantar flexed position. Surgery is not necessary, nor are there any surgical cases reported in the literature. Orthopaedic referral is indicated for recalcitrant cases.

Acknowledgments

The Audio-Visual Department, Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Akron and Adeline Weiner assisted in preparing this paper.

Correspondence

Dennis S. Weiner, MD, 300 Locust Street, Suite 160, Akron, OH 44302-1821. [email protected]

1. Ogden J. Skeletal Injury in the Child. 3rd ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2000:1118–1120.

2. Orava S, Virtanen K. Osteochondroses in athletes. Br J Sports Med 1982;16:161-168.

3. Weiner DS. Pediatric Orthopedics for Primary Care Physicians. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004.

4. Ishikawa SN. Conditions of the calcaneus in skeletally immature patients. Foot Ankle Clin N Am 2005;10:503-513.

5. Allison N. Apophysitis of the os calcis. J Bone Joint Surg 1924;6:91-94.

6. Brantigan CO. Calcaneal apophysitis. One of the growing pains of adolescence. Rocky Mt Med J 1972;69(8):59-60.

7. Ogden J, Ganey T, Hill JD, Jaakkola JI. Sever’s injury: a stress fracture of the immature calcaneal metaphysis. J Pediatr Orthop 2004;24:488-492.

8. Micheli LJ, Ireland LM. Prevention and management of calcaneal apophysitis in children; an overuse syndrome. J Pediatr Orthop 1987;7:34-38.

9. Liberson A, Lieberson S, Mendes DG, Shajrawi I, Ben Haim Y, Boss JH. Remodeling of the calcaneus apophysis in the growing child. J Pediatr Orthop 1995;4:74-79.

10. Contompasis JP. The management of heel pain in the athlete. Clin Podiatr Med Surg 1986;3:705-711.

11. McKenzie DC, Taunton JE, Clement DB, Smart GW, McNicol KL. Calcaneal epiphysitis in adolescent athletes. Can J Appl Sport Sci 1981;6:123-125.

12. Madden C, Mellion M. Sever’s disease and other causes of heel pain in adolescents. Am Fam Physician 1996;54:1995-2000.

13. Meyerding HW, Stuck WG. Painful heels among children (apophysitis). JAMA 1934;102:1658-1660.

14. Rhine I, Locke R. Apophysitis of the calcaneus. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1952;51:441-447.

15. Ross SE, Caffey J. Ossification of the calcaneal apophysis in healthy children. Stanford Med Bull 1957;15:224-226.

16. Sever JW. Apophysitis of the os calcis. NY State J Med 1912;95:1025-1029.

17. Volpon JB, de Carvalho Filho G. Calcaneal apophysitis a quantitative radiographic evaluation of the secondary ossification center. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2002;122:338-341.

18. Hughes ASR. Painful heels in children. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1948;86:64-68.

19. Kohler A, Zimmer EA. Borderlands of the Normal and Early Pathologic and Skeletal Roentgenology. 3rd ed. New York: Grune and Stratton; 1968.

20. Shopfner CE, Coin CG. Effect of weightbearing on the appearance and development of the secondary calcaneal epiphysis. Radiology 1966;86:201-206.

21. Krantz MK. Calcaneal apophysitis a clinical and roentgenologic study. J Am Podiatry Assoc 1965;55:801-807.

22. Lerner LH. Radiographic evaluation of calcaneal apophysitis. J Natl Assoc Chiropodists 1957;47:451-459.

1. Ogden J. Skeletal Injury in the Child. 3rd ed. New York: Springer-Verlag; 2000:1118–1120.

2. Orava S, Virtanen K. Osteochondroses in athletes. Br J Sports Med 1982;16:161-168.

3. Weiner DS. Pediatric Orthopedics for Primary Care Physicians. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2004.

4. Ishikawa SN. Conditions of the calcaneus in skeletally immature patients. Foot Ankle Clin N Am 2005;10:503-513.

5. Allison N. Apophysitis of the os calcis. J Bone Joint Surg 1924;6:91-94.

6. Brantigan CO. Calcaneal apophysitis. One of the growing pains of adolescence. Rocky Mt Med J 1972;69(8):59-60.

7. Ogden J, Ganey T, Hill JD, Jaakkola JI. Sever’s injury: a stress fracture of the immature calcaneal metaphysis. J Pediatr Orthop 2004;24:488-492.

8. Micheli LJ, Ireland LM. Prevention and management of calcaneal apophysitis in children; an overuse syndrome. J Pediatr Orthop 1987;7:34-38.

9. Liberson A, Lieberson S, Mendes DG, Shajrawi I, Ben Haim Y, Boss JH. Remodeling of the calcaneus apophysis in the growing child. J Pediatr Orthop 1995;4:74-79.

10. Contompasis JP. The management of heel pain in the athlete. Clin Podiatr Med Surg 1986;3:705-711.

11. McKenzie DC, Taunton JE, Clement DB, Smart GW, McNicol KL. Calcaneal epiphysitis in adolescent athletes. Can J Appl Sport Sci 1981;6:123-125.

12. Madden C, Mellion M. Sever’s disease and other causes of heel pain in adolescents. Am Fam Physician 1996;54:1995-2000.

13. Meyerding HW, Stuck WG. Painful heels among children (apophysitis). JAMA 1934;102:1658-1660.

14. Rhine I, Locke R. Apophysitis of the calcaneus. J Am Osteopath Assoc 1952;51:441-447.

15. Ross SE, Caffey J. Ossification of the calcaneal apophysis in healthy children. Stanford Med Bull 1957;15:224-226.

16. Sever JW. Apophysitis of the os calcis. NY State J Med 1912;95:1025-1029.

17. Volpon JB, de Carvalho Filho G. Calcaneal apophysitis a quantitative radiographic evaluation of the secondary ossification center. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2002;122:338-341.

18. Hughes ASR. Painful heels in children. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1948;86:64-68.

19. Kohler A, Zimmer EA. Borderlands of the Normal and Early Pathologic and Skeletal Roentgenology. 3rd ed. New York: Grune and Stratton; 1968.

20. Shopfner CE, Coin CG. Effect of weightbearing on the appearance and development of the secondary calcaneal epiphysis. Radiology 1966;86:201-206.

21. Krantz MK. Calcaneal apophysitis a clinical and roentgenologic study. J Am Podiatry Assoc 1965;55:801-807.

22. Lerner LH. Radiographic evaluation of calcaneal apophysitis. J Natl Assoc Chiropodists 1957;47:451-459.