User login

Prognostication continues to be a challenge to the clinician despite over 100 prognostic indices that have been developed during the past few decades to inform clinical practice and medical decision making.[1] Physicians are not accurate in prognostication of patients' risk of death and tend to overestimate survival.[2, 3] In addition, many physicians do not feel comfortable offering a prognosis to patients, despite patients' wishes to be informed.[4, 5] Regardless of the prevalence in the literature and value in improving physicians' prognostic accuracy, prognostic indices of survival are not regularly utilized in the hospital setting. Prognostic tools available for providers are often complicated and may require data about patients that are not readily available.[6, 7, 8] Prognostic indices may be too specific to a patient population, too difficult to remember, or too time consuming to use. A simple, rapid, and practical prognostic index is important in the hospital setting to assist in identifying patients at high risk of death so that primary palliative interventions can be incorporated into the plan of care early in the hospital stay. Patient and family education, advance care planning, formulating the plan of care based on patientfamily goals, and improved resource utilization could be better executed by more accurate risk of death prediction on hospital admission.

The CARING criteria are the only prognostic index to our knowledge that evaluates a patient's risk of death in the next year, with information readily available at the time of hospital admission (Table 1).[9] The CARING criteria are a unique prognostic tool: (1) CARING is a mnemonic acronym, making it more user friendly to the clinician. (2) The 5 prognostic indicators are readily available from the patient's chart on admission; gathering further data by patient or caretaker interviews or by obtaining laboratory data is not needed. (3) The timing for application of the tool on admission to the hospital is an ideal opportunity to intervene and introduce palliative interventions early on the hospital stay. The CARING criteria were developed and validated in a Veteran's Administration hospital setting by Fischer et al.[9] We sought to validate the CARING criteria in a broader patient populationmedical and surgical patients from a tertiary referral university hospital setting and a safety‐net hospital setting.

METHODS

Study Design

This study was a retrospective observational cohort study. The study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board and the University of Colorado Hospital Research Review Committee.

Study Purpose

To validate the CARING criteria in a tertiary referral university hospital (University of Colorado Hospital [UCH]) and safety‐net hospital (Denver Health and Hospitals [DHH]) setting using similar methodology to that employed by the original CARING criteria study.[9]

Study Setting/Population

All adults (18 years of age) admitted as inpatients to the medical and surgical services of internal medicine, hospitalist, pulmonary, cardiology, hematology/oncology, hepatology, surgery, intensive care unit, and intermediary care unit at UCH and DHH during the study period of July 2005 through August 2005. The only exclusion criteria were those patients who were prisoners or pregnant. Administrative admission data from July 2005 to August 2005 were used to identify names of all persons admitted to the medicine and surgical services of the study hospitals during the specified time period.

The 2 study hospitals, UCH and DHH, provide a range of patients who vary in ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and medical illness. This variability allows for greater generalizability of the results. Both hospitals are affiliated with the University of Colorado School of Medicine internal medicine residency training program and are located in Denver, Colorado.

At the time of the study, UCH was a licensed 550‐bed tertiary referral, academic hospital serving the Denver metropolitan area and the Rocky Mountain region as a specialty care and referral center. DHH was a 398‐bed, academic, safety‐net hospital serving primarily the Denver metropolitan area. DHH provides 42% of the care for the uninsured in Denver and 26% of the uninsured care for the state of Colorado.

Measures

The CARING criteria were developed and validated in a Veteran's Administration (VA) hospital setting by Fischer et al.[9] The purpose of the CARING criteria is to identify patients, at the time of hospital admission, who are at higher risk of death in the following year. The prognostic index uses 5 predictors that can be abstracted from the chart at time of admission. The CARING criteria were developed a priori, and patients were evaluated using only the medical data available at the time of admission. The criteria include items that are already part of the routine physician admission notes and do not require additional data collection or assessments. The criteria include: C=primary diagnosis of cancer, A=2 admissions to the hospital for a chronic illness within the last year; R=resident in a nursing home; I=intensive care unit (ICU) admission with multiorgan failure (MOF), NG=noncancer hospice guidelines (meeting 2 of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization's [NHPCO] guidelines).

Patients were identified using name, date of birth, social security number, address, and phone number. This identifying information was then used for tracing death records 1 year after hospital admission.

Mortality at 1 year following the index hospitalization was the primary end point. To minimize missing data and the number of subjects lost to follow‐up, 3 determinants of mortality were used. First, electronic medical records of the 2 participating hospitals and their outpatient clinics were reviewed to determine if a follow‐up appointment had occurred past the study's end point of 1 year (August 2006). For those without a confirmed follow‐up visit, death records from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Vital Records were obtained. For those patients residing outside of Colorado or whose mortality status was still unclear, the National Death Index was accessed.

Medical Record Review

Medical records for all study participants were reviewed by J.Y. (UCH) and B.C. (DHH). Data collection was completed using direct data entry into a Microsoft Access (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) database utilizing a data entry form linked with the database table. This form utilized skip patterns and input masks to ensure quality of data entry and minimize missing or invalid data. Inter‐rater reliability was assessed by an independent rereview (S.F.) of 5% of the total charts. Demographic variables were collected using hospital administrative data. These included personal identifiers of the participants for purposes of mortality follow‐up. Clinical data including the 5 CARING variables and additional descriptive variables were abstracted from the paper hospital chart and the electronic record of the chart (together these constitute the medical record).

Death Follow‐up

A search of Colorado death records was conducted in February 2011 for all subjects. Death records were used to determine mortality and time to death from the index hospitalization. The National Death Index was then searched for any subjects without or record of death in Colorado.

Analysis

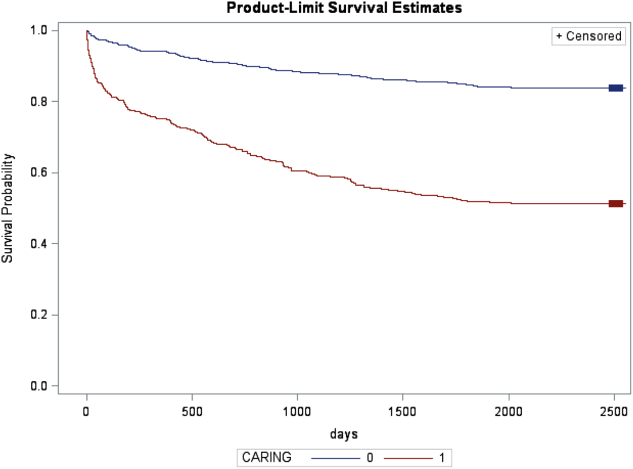

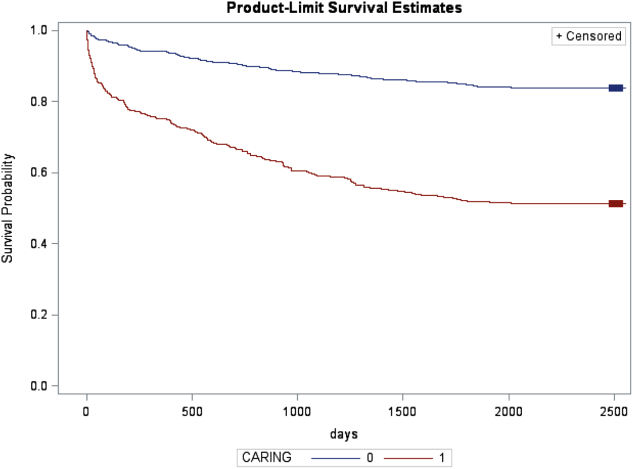

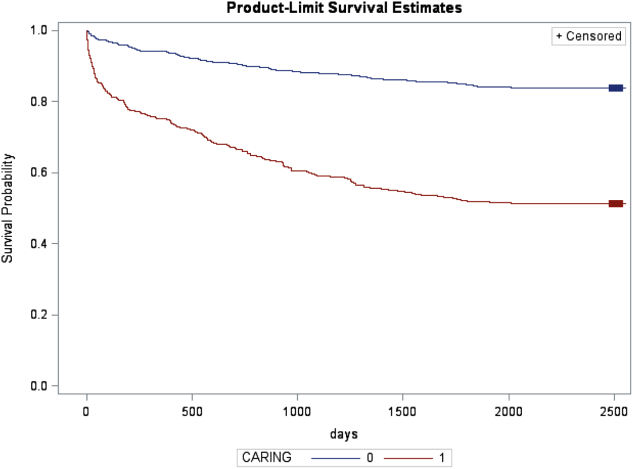

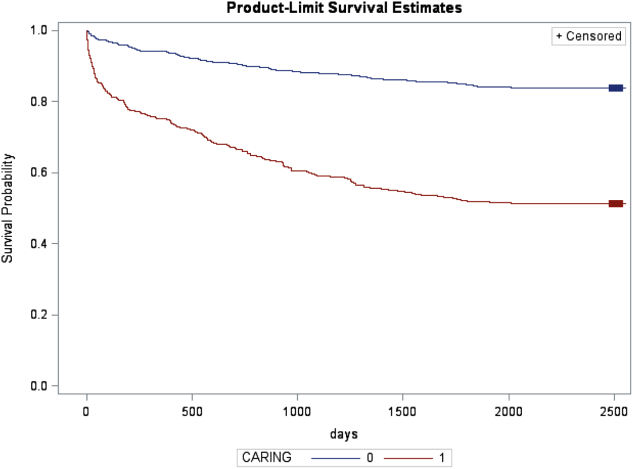

All analyses were conducted using the statistical application software SAS for Windows version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Simple frequencies and means ( standard deviation) were used to describe the baseline characteristics. Multiple logistic regression models were used to model 1‐year mortality. The models were fitted using all of the CARING variables and age. As the aim of the study was to validate the CARING criteria, the variables for the models were selected a priori based on the original index. Two hospital cohorts (DHH and UCH) were modeled separately and as a combined sample. Kaplan‐Meier survival analysis was conducted to compare those subjects who met 1 of the CARING criteria with those who did not through the entire period of mortality follow‐up (20052011). Finally, using the probabilities from the logistic regression models, we again developed a scoring rule appropriate for a non‐VA setting to allow clinicians to easily identify patient risk for 1‐year mortality at the time of hospital admission.

RESULTS

There were a total of 1064 patients admitted to the medical and surgical services during the study period568 patients at DHH and 496 patients at UCH. Sample characteristics of each individual hospital cohort and the entire combined study cohort are detailed in Table 2. Overall, slightly over half the population were male, with a mean age of 50 years, and the ethnic breakdown roughly reflects the population in Denver. A total of 36.5% (n=388) of the study population met 1 of the CARING criteria, and 12.6% (n=134 among 1063 excluding 1 without an admit date) died within 1 year of the index hospitalization. These were younger and healthier patients compared to the VA sample used in developing the CARING criteria.

| |

| Renal | Dementia |

| Stop/decline dialysis | Unable to ambulate independently |

| Not candidate for transplant | Urinary or fecal incontinence |

| Urine output < 40cc/24 hours | Unable to speak with more than single words |

| Creatinine > 8.0 (>6.0 for diabetics) | Unable to bathe independently |

| Creatinine clearance 10cc/min | Unable to dress independently |

| Uremia | Co‐morbid conditions: |

| Persistent serum K + > 7.0 | Aspiration pneumonia |

| Co‐morbid conditions: | Pyelonephritis |

| Cancer CHF | Decubitus ulcer |

| Chronic lung disease AIDS/HIV | Difficulty swallowing or refusal to eat |

| Sepsis Cirrhosis | |

| Cardiac | Pulmonary |

| Ejection fraction < 20% | Dyspnea at rest |

| Symptomatic with diuretics and vasodilators | FEV1 < 30% |

| Not candidate for transplant | Frequent ER or hospital admits for pulmonary infections or respiratory distress |

| History of cardiac arrest | Cor pulmonale or right heart failure |

| History of syncope | 02 sat < 88% on 02 |

| Systolic BP < 120mmHG | PC02 > 50 |

| CVA cardiac origin | Resting tachycardia > 100/min |

| Co‐morbid conditions as listed in Renal | Co‐morbid conditions as listed in Renal |

| Liver | Stroke/CVA |

| End stage cirrhosis | Coma at onset |

| Not candidate for transplant | Coma >3 days |

| Protime > 5sec and albumin <2.5 | Limb paralysis |

| Ascites unresponsive to treatment | Urinary/fecal incontinence |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | Impaired sitting balance |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | Karnofsky < 50% |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | Recurrent aspiration |

| Recurrent variceal bleed | Age > 70 |

| Co‐morbid conditions as listed in Renal | Co‐morbid conditions as listed in Renal |

| HIV/AIDS | Neuromuscular |

| Persistent decline in function | Diminished respiratory function |

| Chronic diarrhea 1 year | Chosen not to receive BiPAP/vent |

| Decision to stop treatment | Difficulty swallowing |

| CNS lymphoma | Diminished functional status |

| MAC‐untreated | Incontinence |

| Systemic lymphoma | Co‐morbid conditions as listed in Renal |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | |

| CD4 < 25 with disease progression | |

| Viral load > 100,000 | |

| Safety‐Net Hospital Cohort, N=568 | Academic Center Cohort, N=496 | Study Cohort,N=1064 | Original CARING Cohort, N=8739 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Mean age ( SD), y | 47.8 (16.5) | 54.4 (17.5) | 50.9 (17.3) | 63 (13) |

| Male gender | 59.5% (338) | 50.1% (248) | 55.1% (586) | 98% (856) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| African American | 14.1% (80) | 13.5% (65) | 13.8% (145) | 13% (114) |

| Asian | 0.4% (2) | 1.5% (7) | 0.9% (9) | Not reported |

| Caucasian | 41.7% (237) | 66.3% (318) | 53.0 % (555) | 69% (602) |

| Latino | 41.9% (238) | 9.6% (46) | 27.1% (284) | 8% (70) |

| Native American | 0.5% (3) | 0.4% (2) | 0.5% (5) | Not reported |

| Other | 0.5% (3) | 0.6% (3) | 0.6% (6) | 10% (87) |

| Unknown | 0.9% (5) | 8.1% (39) | 4.2% (44) | Not reported |

| CARING criteria | ||||

| Cancer | 6.2% (35) | 19.4% (96) | 12.3% (131) | 23% (201) |

| Admissions to the hospital 2 in past year | 13.6% (77) | 42.7% (212) | 27.2% (289) | 36% (314) |

| Resident in a nursing home | 1.8% (10) | 3.4% (17) | 2.5% (27) | 3% (26) |

| ICU with MOF | 3.7% (21) | 1.2% (6) | 2.5% (27) | 2% (17) |

| NHPCO (2) noncancer guidelines | 1.6% (9) | 5.9% (29) | 3.6% (38) | 8% (70) |

Reliability testing demonstrated excellent inter‐rater reliability. Kappa for each criterion is as follows: (1) primary diagnosis of cancer=1.0, (2) 2 admissions to the hospital in the past year=0.91, (3) resident in a nursing home=1.0, (4) ICU admission with MOF=1.0, and (5) 2 noncancer hospice guidelines=0.78.

This study aimed to validate the CARING criteria9; therefore, all original individual CARING criterion were included in the validation logistic regression models. The 1 exception to this was in the university hospital study cohort, where the ICU criterion was excluded from the model due to small sample size and quasiseparation in the model. The model results are presented in Table 3 for the individual hospitals and combined study cohort.

| Safety Net Hospital Cohort, C Index=0.76 | Academic Center Cohort, C Index=0.76 | Combined Hospital Cohort, C Index=0.79 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Estimate | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Estimate | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

| ||||||

| Cancer | 1.92 | 6.85 (2.83‐16.59)a | 1.85 | 6.36 (3.54‐11.41)a | 1.98 | 7.23 (4.45‐11.75)a |

| Admissions to the hospital 2 in past year | 0.55 | 1.74 (0.76‐3.97) | 0.14 | 0.87 (0.51‐1.49) | 0.20 | 1.22 (0.78‐1.91) |

| Resident in a nursing home | 0.49 | 0.61 (0.06‐6.56) | 0.27 | 1.31 (0.37‐4.66) | 0.09 | 1.09 (0.36‐3.32) |

| ICU with MOF | 1.85 | 6.34 (2.0219.90)a | 1.94 | 6.97 (2.75‐17.68)a | ||

| NHPCO (2) noncancer guidelines | 3.04 | 20.86 (4.25102.32)a | 2.62 | 13.73 (5.86‐32.15)a | 2.74 | 15.55 (7.2833.23)a |

| Ageb | 0.38 | 1.46 (1.05‐2.03)a | 0.45 | 1.56 (1.23‐1.98)a | 0.47 | 1.60 (1.32‐1.93)a |

In the safety‐net hospital, admission to the hospital with a primary diagnosis related to cancer, 2 noncancer hospice guidelines, ICU admission with MOF, and age by category all were significant predictors of 1‐year mortality. In the university hospital cohort, primary diagnosis of cancer, 2 noncancer hospice guidelines, and age by category were predictive of 1‐year mortality. Finally, in the entire study cohort, primary diagnosis of cancer, ICU with MOF, 2 noncancer hospice guidelines, and age were all predictive of 1‐year mortality. Parameter estimates were similar in 3 of the criteria compared to the VA setting. Differences in patient characteristics may have caused the differences in the estimates. Gender was additionally tested but not significant in any model. One‐year survival was significantly lower for those who met 1 of the CARING criteria versus those who did not (Figure 1).

Based on the framework from the original CARING criteria analysis, a scoring rule was developed using the regression results of this validation cohort. To predict a high probability of 1‐year mortality, sensitivity was set to 58% and specificity was set at 86% (error rate=17%). Medium to high probability was set with a sensitivity of 73% and specificity of 72% (error rate=28%). The coefficients from the regression model of the entire study cohort were converted to scores for each of the CARING criteria. The scores are as follows: 0.5 points for admission from a nursing home, 1 point for 2 hospital admissions in the past year for a chronic illness, 10 points for primary diagnosis of cancer, 10 points for ICU admission with MOF, and 14 points for 2 noncancer hospice guidelines. For every age category increase, 2 points are assigned so that 0 points for age <55 years, 2 points for ages 56 to 65 years, 4 points for ages 66 to 75 years, and 6 points for >75 years. Points for individual risk factors were proportional to s (ie, log odds) in the logistic regression model for death at 1 year. Although no linear transformation exists between s and probabilities (of death at 1 year), the aggregated points for combinations of risk factors shown in Table 4 follow the probabilities in an approximately linear fashion, so that different degrees of risk of death can be represented contiguously (as highlighted by differently shaded regions in the scoring matrix) (Table 4). The scoring matrix allows for quick identification for patients at high risk for 1‐year mortality. In this non‐VA setting with healthier patients, low risk is defined at a lower probability threshold (0.1) compared to the VA setting (0.175).

| CARING Criteria Components | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Resident in a Nursing Home | Admitted to the Hospital 2 Times in the Past Year | Resident in a Nursing Home Admitted to the Hospital 2 Times in the Past Year | Primary Diagnosis of Cancer | ICU Admission With MOF | Noncancer Hospice Guidelines | |

| |||||||

| Age | |||||||

| 55 years | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 10 | ||

| 5565 years | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | 3.5 | 10 | ||

| 6675 years | 4 | 4.5 | 5 | 5.5 | 10 | ||

| >75 years | 6 | 6.5 | 7 | 7.5 | 10 | ||

| Risk | |||||||

| Low | 3.5 | Probability<0.1 | |||||

| Medium | 46.5 | 0.1probability <0.175 | |||||

| High | 7 | Probability0.175 | |||||

DISCUSSION

The CARING criteria are a practical prognostic tool that can be easily and rapidly applied to patients admitted to the hospital to estimate risk of death in 1 year, with the goal of identifying patients who may benefit most from incorporating palliative interventions into their plan of care. This study validated the CARING criteria in a tertiary referral university hospital and safety‐net hospital setting, demonstrating applicability in a much broader population than the VA hospital of the original CARING criteria study. The population studied represented a younger population by over 10 years, a more equitable proportion of males to females, a broader ethnic diversity, and lower 1‐year deaths rates than the original study. Despite the broader representation of the population, the significance of each of the individual CARING criterion was maintained except for 2 hospital admissions in the past year for a chronic illness (admission from a nursing home did not meet significance in either study as a sole criterion). As with the original study, meeting 2 of the NHPCO noncancer hospice guidelines demonstrated the highest risk of 1‐year mortality following index hospitalization, followed by primary diagnosis of cancer and ICU admission with MOF. Advancing age, also similar to the original study, conferred increased risk across the criterion.

Hospitalists could be an effective target for utilizing the CARING criteria because they are frequently the first‐line providers in the hospital setting. With the national shortage of palliative care specialists, hospitalists need to be able to identify when a patient has a limited life expectancy so they will be better equipped to make clinical decisions that are aligned with their patients' values, preferences, and goals of care. With the realization that not addressing advance care planning and patient goals of care may be considered medical errors, primary palliative care skills become alarmingly more important as priorities for hospitalists to obtain and feel comfortable using in daily practice.

The CARING criteria are directly applicable to patients who are seen by hospitalists. Other prognostic indices have focused on select patient populations, such as the elderly,[10, 11, 12] require collection of data that are not readily available on admission or would not otherwise be obtained,[10, 13] or apply to patients post‐hospital discharge, thereby missing the opportunity to make an impact earlier in the disease trajectory and incorporate palliative care into the hospital plan of care when key discussions about goals of care and preferences should be encouraged.

Additionally, the CARING criteria could easily be incorporated as a trigger for palliative care consults on hospital admission. Palliative care consults tend to happen late in a hospital stay, limiting the effectiveness of the palliative care team. A trigger system for hospitalists and other primary providers on hospital admission would lend to more effective timing of palliative measures being incorporated into the plan of care. Palliative care consults would not only be initiated earlier, but could be targeted for the more complex and sick patients with the highest risk of death in the next year.

In the time‐pressured environment, the presence of any 1 of the CARING criteria can act as a trigger to begin incorporating primary palliative care measures into the plan of care. The admitting hospitalist provider (ie, physician, nurse practitioner, physician assistant) could access the CARING criteria through an electronic health record prompt when admitting patients. When a more detailed assessment of mortality risk is helpful, the hospitalist can use the scoring matrix, which combines age with the individual criterion to calculate patients at medium or high risk of death within 1 year. Limited resources can then be directed to the patients with the greatest need. Patients with a focused care need, such as advance care planning or hospice referral, can be directed to the social worker or case manager. More complicated patients may be referred to a specialty palliative care team.

Several limitations to this study are recognized, including the small sample size of patients meeting criterion for ICU with MOF in the academic center study cohort. The patient data were collected during a transition time when the university hospital moved to a new campus, resulting in an ICU at each campus that housed patients with differing levels of illness severity, which may have contributed to the lower acuity ICU patient observed. Although we advocate the simplicity of the CARING criteria, the NHPCO noncancer hospice guidelines are more complicated, as they incorporates 8 broad categories of chronic illness. The hospice guidelines may not be general knowledge to the hospitalist or other primary providers. ePrognosis (

CONCLUSION

The CARING criteria are a simple, practical prognostic tool predictive of death within 1 year that has been validated in a broad population of hospitalized patients. The criteria hold up in a younger, healthier population that is more diverse by age, gender, and ethnicity than the VA population. With ready access to critical prognostic information on hospital admission, clinicians will be better informed to make decisions that are aligned with their patients' values, preferences, and goals of care.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , . Predicting death: an empirical evaluation of predictive tools for mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1721–1726.

- , . Extent and determinants of error in physicians' prognoses in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort study. West J Med. 2000;172:310–313.

- , , , et al. A systematic review of physicians' survival predictions in terminally ill cancer patients. BMJ. 2003;327:195–198.

- , . Attitude and self‐reported practice regarding prognostication in a national sample of internists. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2389–2395.

- , , , et al. Discussing prognosis: balancing hope and realism. Cancer J. 2010;16:461–466.

- , , , . Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) IV: hospital mortality assessment for today's critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1297–1310.

- , , , , . SAPS 3 admission score: an external validation in a general intensive care population. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:1873–1877.

- , , , , , . Prospective validation of the intensive care unit admission Mortality Probability Model (MPM0‐III). Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1619–1623.

- , , , , , . A practical tool to identify patients who may benefit from a palliative approach: the CARING criteria. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31:285–292.

- , , , et al. Prediction of survival for older hospitalized patients: the HELP survival model. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:S16–S24.

- , , , et al. Development and validation of a multidimensional prognostic index for one‐year mortality from comprehensive geriatric assessment in hospitalized older patients. Rejuvenation Res. 2008;11:151–161.

- , , , et al. Burden of illness score for elderly persons: risk adjustment incorporating the cumulative impact of diseases, physiologic abnormalities, and functional impairments. Med Care. 2003;41:70–83.

- , , , et al. The SUPPORT prognostic model. Objective estimates of survival for seriously ill hospitalized adults. Study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:191–203.

Prognostication continues to be a challenge to the clinician despite over 100 prognostic indices that have been developed during the past few decades to inform clinical practice and medical decision making.[1] Physicians are not accurate in prognostication of patients' risk of death and tend to overestimate survival.[2, 3] In addition, many physicians do not feel comfortable offering a prognosis to patients, despite patients' wishes to be informed.[4, 5] Regardless of the prevalence in the literature and value in improving physicians' prognostic accuracy, prognostic indices of survival are not regularly utilized in the hospital setting. Prognostic tools available for providers are often complicated and may require data about patients that are not readily available.[6, 7, 8] Prognostic indices may be too specific to a patient population, too difficult to remember, or too time consuming to use. A simple, rapid, and practical prognostic index is important in the hospital setting to assist in identifying patients at high risk of death so that primary palliative interventions can be incorporated into the plan of care early in the hospital stay. Patient and family education, advance care planning, formulating the plan of care based on patientfamily goals, and improved resource utilization could be better executed by more accurate risk of death prediction on hospital admission.

The CARING criteria are the only prognostic index to our knowledge that evaluates a patient's risk of death in the next year, with information readily available at the time of hospital admission (Table 1).[9] The CARING criteria are a unique prognostic tool: (1) CARING is a mnemonic acronym, making it more user friendly to the clinician. (2) The 5 prognostic indicators are readily available from the patient's chart on admission; gathering further data by patient or caretaker interviews or by obtaining laboratory data is not needed. (3) The timing for application of the tool on admission to the hospital is an ideal opportunity to intervene and introduce palliative interventions early on the hospital stay. The CARING criteria were developed and validated in a Veteran's Administration hospital setting by Fischer et al.[9] We sought to validate the CARING criteria in a broader patient populationmedical and surgical patients from a tertiary referral university hospital setting and a safety‐net hospital setting.

METHODS

Study Design

This study was a retrospective observational cohort study. The study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board and the University of Colorado Hospital Research Review Committee.

Study Purpose

To validate the CARING criteria in a tertiary referral university hospital (University of Colorado Hospital [UCH]) and safety‐net hospital (Denver Health and Hospitals [DHH]) setting using similar methodology to that employed by the original CARING criteria study.[9]

Study Setting/Population

All adults (18 years of age) admitted as inpatients to the medical and surgical services of internal medicine, hospitalist, pulmonary, cardiology, hematology/oncology, hepatology, surgery, intensive care unit, and intermediary care unit at UCH and DHH during the study period of July 2005 through August 2005. The only exclusion criteria were those patients who were prisoners or pregnant. Administrative admission data from July 2005 to August 2005 were used to identify names of all persons admitted to the medicine and surgical services of the study hospitals during the specified time period.

The 2 study hospitals, UCH and DHH, provide a range of patients who vary in ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and medical illness. This variability allows for greater generalizability of the results. Both hospitals are affiliated with the University of Colorado School of Medicine internal medicine residency training program and are located in Denver, Colorado.

At the time of the study, UCH was a licensed 550‐bed tertiary referral, academic hospital serving the Denver metropolitan area and the Rocky Mountain region as a specialty care and referral center. DHH was a 398‐bed, academic, safety‐net hospital serving primarily the Denver metropolitan area. DHH provides 42% of the care for the uninsured in Denver and 26% of the uninsured care for the state of Colorado.

Measures

The CARING criteria were developed and validated in a Veteran's Administration (VA) hospital setting by Fischer et al.[9] The purpose of the CARING criteria is to identify patients, at the time of hospital admission, who are at higher risk of death in the following year. The prognostic index uses 5 predictors that can be abstracted from the chart at time of admission. The CARING criteria were developed a priori, and patients were evaluated using only the medical data available at the time of admission. The criteria include items that are already part of the routine physician admission notes and do not require additional data collection or assessments. The criteria include: C=primary diagnosis of cancer, A=2 admissions to the hospital for a chronic illness within the last year; R=resident in a nursing home; I=intensive care unit (ICU) admission with multiorgan failure (MOF), NG=noncancer hospice guidelines (meeting 2 of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization's [NHPCO] guidelines).

Patients were identified using name, date of birth, social security number, address, and phone number. This identifying information was then used for tracing death records 1 year after hospital admission.

Mortality at 1 year following the index hospitalization was the primary end point. To minimize missing data and the number of subjects lost to follow‐up, 3 determinants of mortality were used. First, electronic medical records of the 2 participating hospitals and their outpatient clinics were reviewed to determine if a follow‐up appointment had occurred past the study's end point of 1 year (August 2006). For those without a confirmed follow‐up visit, death records from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Vital Records were obtained. For those patients residing outside of Colorado or whose mortality status was still unclear, the National Death Index was accessed.

Medical Record Review

Medical records for all study participants were reviewed by J.Y. (UCH) and B.C. (DHH). Data collection was completed using direct data entry into a Microsoft Access (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) database utilizing a data entry form linked with the database table. This form utilized skip patterns and input masks to ensure quality of data entry and minimize missing or invalid data. Inter‐rater reliability was assessed by an independent rereview (S.F.) of 5% of the total charts. Demographic variables were collected using hospital administrative data. These included personal identifiers of the participants for purposes of mortality follow‐up. Clinical data including the 5 CARING variables and additional descriptive variables were abstracted from the paper hospital chart and the electronic record of the chart (together these constitute the medical record).

Death Follow‐up

A search of Colorado death records was conducted in February 2011 for all subjects. Death records were used to determine mortality and time to death from the index hospitalization. The National Death Index was then searched for any subjects without or record of death in Colorado.

Analysis

All analyses were conducted using the statistical application software SAS for Windows version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Simple frequencies and means ( standard deviation) were used to describe the baseline characteristics. Multiple logistic regression models were used to model 1‐year mortality. The models were fitted using all of the CARING variables and age. As the aim of the study was to validate the CARING criteria, the variables for the models were selected a priori based on the original index. Two hospital cohorts (DHH and UCH) were modeled separately and as a combined sample. Kaplan‐Meier survival analysis was conducted to compare those subjects who met 1 of the CARING criteria with those who did not through the entire period of mortality follow‐up (20052011). Finally, using the probabilities from the logistic regression models, we again developed a scoring rule appropriate for a non‐VA setting to allow clinicians to easily identify patient risk for 1‐year mortality at the time of hospital admission.

RESULTS

There were a total of 1064 patients admitted to the medical and surgical services during the study period568 patients at DHH and 496 patients at UCH. Sample characteristics of each individual hospital cohort and the entire combined study cohort are detailed in Table 2. Overall, slightly over half the population were male, with a mean age of 50 years, and the ethnic breakdown roughly reflects the population in Denver. A total of 36.5% (n=388) of the study population met 1 of the CARING criteria, and 12.6% (n=134 among 1063 excluding 1 without an admit date) died within 1 year of the index hospitalization. These were younger and healthier patients compared to the VA sample used in developing the CARING criteria.

| |

| Renal | Dementia |

| Stop/decline dialysis | Unable to ambulate independently |

| Not candidate for transplant | Urinary or fecal incontinence |

| Urine output < 40cc/24 hours | Unable to speak with more than single words |

| Creatinine > 8.0 (>6.0 for diabetics) | Unable to bathe independently |

| Creatinine clearance 10cc/min | Unable to dress independently |

| Uremia | Co‐morbid conditions: |

| Persistent serum K + > 7.0 | Aspiration pneumonia |

| Co‐morbid conditions: | Pyelonephritis |

| Cancer CHF | Decubitus ulcer |

| Chronic lung disease AIDS/HIV | Difficulty swallowing or refusal to eat |

| Sepsis Cirrhosis | |

| Cardiac | Pulmonary |

| Ejection fraction < 20% | Dyspnea at rest |

| Symptomatic with diuretics and vasodilators | FEV1 < 30% |

| Not candidate for transplant | Frequent ER or hospital admits for pulmonary infections or respiratory distress |

| History of cardiac arrest | Cor pulmonale or right heart failure |

| History of syncope | 02 sat < 88% on 02 |

| Systolic BP < 120mmHG | PC02 > 50 |

| CVA cardiac origin | Resting tachycardia > 100/min |

| Co‐morbid conditions as listed in Renal | Co‐morbid conditions as listed in Renal |

| Liver | Stroke/CVA |

| End stage cirrhosis | Coma at onset |

| Not candidate for transplant | Coma >3 days |

| Protime > 5sec and albumin <2.5 | Limb paralysis |

| Ascites unresponsive to treatment | Urinary/fecal incontinence |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | Impaired sitting balance |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | Karnofsky < 50% |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | Recurrent aspiration |

| Recurrent variceal bleed | Age > 70 |

| Co‐morbid conditions as listed in Renal | Co‐morbid conditions as listed in Renal |

| HIV/AIDS | Neuromuscular |

| Persistent decline in function | Diminished respiratory function |

| Chronic diarrhea 1 year | Chosen not to receive BiPAP/vent |

| Decision to stop treatment | Difficulty swallowing |

| CNS lymphoma | Diminished functional status |

| MAC‐untreated | Incontinence |

| Systemic lymphoma | Co‐morbid conditions as listed in Renal |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | |

| CD4 < 25 with disease progression | |

| Viral load > 100,000 | |

| Safety‐Net Hospital Cohort, N=568 | Academic Center Cohort, N=496 | Study Cohort,N=1064 | Original CARING Cohort, N=8739 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Mean age ( SD), y | 47.8 (16.5) | 54.4 (17.5) | 50.9 (17.3) | 63 (13) |

| Male gender | 59.5% (338) | 50.1% (248) | 55.1% (586) | 98% (856) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| African American | 14.1% (80) | 13.5% (65) | 13.8% (145) | 13% (114) |

| Asian | 0.4% (2) | 1.5% (7) | 0.9% (9) | Not reported |

| Caucasian | 41.7% (237) | 66.3% (318) | 53.0 % (555) | 69% (602) |

| Latino | 41.9% (238) | 9.6% (46) | 27.1% (284) | 8% (70) |

| Native American | 0.5% (3) | 0.4% (2) | 0.5% (5) | Not reported |

| Other | 0.5% (3) | 0.6% (3) | 0.6% (6) | 10% (87) |

| Unknown | 0.9% (5) | 8.1% (39) | 4.2% (44) | Not reported |

| CARING criteria | ||||

| Cancer | 6.2% (35) | 19.4% (96) | 12.3% (131) | 23% (201) |

| Admissions to the hospital 2 in past year | 13.6% (77) | 42.7% (212) | 27.2% (289) | 36% (314) |

| Resident in a nursing home | 1.8% (10) | 3.4% (17) | 2.5% (27) | 3% (26) |

| ICU with MOF | 3.7% (21) | 1.2% (6) | 2.5% (27) | 2% (17) |

| NHPCO (2) noncancer guidelines | 1.6% (9) | 5.9% (29) | 3.6% (38) | 8% (70) |

Reliability testing demonstrated excellent inter‐rater reliability. Kappa for each criterion is as follows: (1) primary diagnosis of cancer=1.0, (2) 2 admissions to the hospital in the past year=0.91, (3) resident in a nursing home=1.0, (4) ICU admission with MOF=1.0, and (5) 2 noncancer hospice guidelines=0.78.

This study aimed to validate the CARING criteria9; therefore, all original individual CARING criterion were included in the validation logistic regression models. The 1 exception to this was in the university hospital study cohort, where the ICU criterion was excluded from the model due to small sample size and quasiseparation in the model. The model results are presented in Table 3 for the individual hospitals and combined study cohort.

| Safety Net Hospital Cohort, C Index=0.76 | Academic Center Cohort, C Index=0.76 | Combined Hospital Cohort, C Index=0.79 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Estimate | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Estimate | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

| ||||||

| Cancer | 1.92 | 6.85 (2.83‐16.59)a | 1.85 | 6.36 (3.54‐11.41)a | 1.98 | 7.23 (4.45‐11.75)a |

| Admissions to the hospital 2 in past year | 0.55 | 1.74 (0.76‐3.97) | 0.14 | 0.87 (0.51‐1.49) | 0.20 | 1.22 (0.78‐1.91) |

| Resident in a nursing home | 0.49 | 0.61 (0.06‐6.56) | 0.27 | 1.31 (0.37‐4.66) | 0.09 | 1.09 (0.36‐3.32) |

| ICU with MOF | 1.85 | 6.34 (2.0219.90)a | 1.94 | 6.97 (2.75‐17.68)a | ||

| NHPCO (2) noncancer guidelines | 3.04 | 20.86 (4.25102.32)a | 2.62 | 13.73 (5.86‐32.15)a | 2.74 | 15.55 (7.2833.23)a |

| Ageb | 0.38 | 1.46 (1.05‐2.03)a | 0.45 | 1.56 (1.23‐1.98)a | 0.47 | 1.60 (1.32‐1.93)a |

In the safety‐net hospital, admission to the hospital with a primary diagnosis related to cancer, 2 noncancer hospice guidelines, ICU admission with MOF, and age by category all were significant predictors of 1‐year mortality. In the university hospital cohort, primary diagnosis of cancer, 2 noncancer hospice guidelines, and age by category were predictive of 1‐year mortality. Finally, in the entire study cohort, primary diagnosis of cancer, ICU with MOF, 2 noncancer hospice guidelines, and age were all predictive of 1‐year mortality. Parameter estimates were similar in 3 of the criteria compared to the VA setting. Differences in patient characteristics may have caused the differences in the estimates. Gender was additionally tested but not significant in any model. One‐year survival was significantly lower for those who met 1 of the CARING criteria versus those who did not (Figure 1).

Based on the framework from the original CARING criteria analysis, a scoring rule was developed using the regression results of this validation cohort. To predict a high probability of 1‐year mortality, sensitivity was set to 58% and specificity was set at 86% (error rate=17%). Medium to high probability was set with a sensitivity of 73% and specificity of 72% (error rate=28%). The coefficients from the regression model of the entire study cohort were converted to scores for each of the CARING criteria. The scores are as follows: 0.5 points for admission from a nursing home, 1 point for 2 hospital admissions in the past year for a chronic illness, 10 points for primary diagnosis of cancer, 10 points for ICU admission with MOF, and 14 points for 2 noncancer hospice guidelines. For every age category increase, 2 points are assigned so that 0 points for age <55 years, 2 points for ages 56 to 65 years, 4 points for ages 66 to 75 years, and 6 points for >75 years. Points for individual risk factors were proportional to s (ie, log odds) in the logistic regression model for death at 1 year. Although no linear transformation exists between s and probabilities (of death at 1 year), the aggregated points for combinations of risk factors shown in Table 4 follow the probabilities in an approximately linear fashion, so that different degrees of risk of death can be represented contiguously (as highlighted by differently shaded regions in the scoring matrix) (Table 4). The scoring matrix allows for quick identification for patients at high risk for 1‐year mortality. In this non‐VA setting with healthier patients, low risk is defined at a lower probability threshold (0.1) compared to the VA setting (0.175).

| CARING Criteria Components | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Resident in a Nursing Home | Admitted to the Hospital 2 Times in the Past Year | Resident in a Nursing Home Admitted to the Hospital 2 Times in the Past Year | Primary Diagnosis of Cancer | ICU Admission With MOF | Noncancer Hospice Guidelines | |

| |||||||

| Age | |||||||

| 55 years | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 10 | ||

| 5565 years | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | 3.5 | 10 | ||

| 6675 years | 4 | 4.5 | 5 | 5.5 | 10 | ||

| >75 years | 6 | 6.5 | 7 | 7.5 | 10 | ||

| Risk | |||||||

| Low | 3.5 | Probability<0.1 | |||||

| Medium | 46.5 | 0.1probability <0.175 | |||||

| High | 7 | Probability0.175 | |||||

DISCUSSION

The CARING criteria are a practical prognostic tool that can be easily and rapidly applied to patients admitted to the hospital to estimate risk of death in 1 year, with the goal of identifying patients who may benefit most from incorporating palliative interventions into their plan of care. This study validated the CARING criteria in a tertiary referral university hospital and safety‐net hospital setting, demonstrating applicability in a much broader population than the VA hospital of the original CARING criteria study. The population studied represented a younger population by over 10 years, a more equitable proportion of males to females, a broader ethnic diversity, and lower 1‐year deaths rates than the original study. Despite the broader representation of the population, the significance of each of the individual CARING criterion was maintained except for 2 hospital admissions in the past year for a chronic illness (admission from a nursing home did not meet significance in either study as a sole criterion). As with the original study, meeting 2 of the NHPCO noncancer hospice guidelines demonstrated the highest risk of 1‐year mortality following index hospitalization, followed by primary diagnosis of cancer and ICU admission with MOF. Advancing age, also similar to the original study, conferred increased risk across the criterion.

Hospitalists could be an effective target for utilizing the CARING criteria because they are frequently the first‐line providers in the hospital setting. With the national shortage of palliative care specialists, hospitalists need to be able to identify when a patient has a limited life expectancy so they will be better equipped to make clinical decisions that are aligned with their patients' values, preferences, and goals of care. With the realization that not addressing advance care planning and patient goals of care may be considered medical errors, primary palliative care skills become alarmingly more important as priorities for hospitalists to obtain and feel comfortable using in daily practice.

The CARING criteria are directly applicable to patients who are seen by hospitalists. Other prognostic indices have focused on select patient populations, such as the elderly,[10, 11, 12] require collection of data that are not readily available on admission or would not otherwise be obtained,[10, 13] or apply to patients post‐hospital discharge, thereby missing the opportunity to make an impact earlier in the disease trajectory and incorporate palliative care into the hospital plan of care when key discussions about goals of care and preferences should be encouraged.

Additionally, the CARING criteria could easily be incorporated as a trigger for palliative care consults on hospital admission. Palliative care consults tend to happen late in a hospital stay, limiting the effectiveness of the palliative care team. A trigger system for hospitalists and other primary providers on hospital admission would lend to more effective timing of palliative measures being incorporated into the plan of care. Palliative care consults would not only be initiated earlier, but could be targeted for the more complex and sick patients with the highest risk of death in the next year.

In the time‐pressured environment, the presence of any 1 of the CARING criteria can act as a trigger to begin incorporating primary palliative care measures into the plan of care. The admitting hospitalist provider (ie, physician, nurse practitioner, physician assistant) could access the CARING criteria through an electronic health record prompt when admitting patients. When a more detailed assessment of mortality risk is helpful, the hospitalist can use the scoring matrix, which combines age with the individual criterion to calculate patients at medium or high risk of death within 1 year. Limited resources can then be directed to the patients with the greatest need. Patients with a focused care need, such as advance care planning or hospice referral, can be directed to the social worker or case manager. More complicated patients may be referred to a specialty palliative care team.

Several limitations to this study are recognized, including the small sample size of patients meeting criterion for ICU with MOF in the academic center study cohort. The patient data were collected during a transition time when the university hospital moved to a new campus, resulting in an ICU at each campus that housed patients with differing levels of illness severity, which may have contributed to the lower acuity ICU patient observed. Although we advocate the simplicity of the CARING criteria, the NHPCO noncancer hospice guidelines are more complicated, as they incorporates 8 broad categories of chronic illness. The hospice guidelines may not be general knowledge to the hospitalist or other primary providers. ePrognosis (

CONCLUSION

The CARING criteria are a simple, practical prognostic tool predictive of death within 1 year that has been validated in a broad population of hospitalized patients. The criteria hold up in a younger, healthier population that is more diverse by age, gender, and ethnicity than the VA population. With ready access to critical prognostic information on hospital admission, clinicians will be better informed to make decisions that are aligned with their patients' values, preferences, and goals of care.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

Prognostication continues to be a challenge to the clinician despite over 100 prognostic indices that have been developed during the past few decades to inform clinical practice and medical decision making.[1] Physicians are not accurate in prognostication of patients' risk of death and tend to overestimate survival.[2, 3] In addition, many physicians do not feel comfortable offering a prognosis to patients, despite patients' wishes to be informed.[4, 5] Regardless of the prevalence in the literature and value in improving physicians' prognostic accuracy, prognostic indices of survival are not regularly utilized in the hospital setting. Prognostic tools available for providers are often complicated and may require data about patients that are not readily available.[6, 7, 8] Prognostic indices may be too specific to a patient population, too difficult to remember, or too time consuming to use. A simple, rapid, and practical prognostic index is important in the hospital setting to assist in identifying patients at high risk of death so that primary palliative interventions can be incorporated into the plan of care early in the hospital stay. Patient and family education, advance care planning, formulating the plan of care based on patientfamily goals, and improved resource utilization could be better executed by more accurate risk of death prediction on hospital admission.

The CARING criteria are the only prognostic index to our knowledge that evaluates a patient's risk of death in the next year, with information readily available at the time of hospital admission (Table 1).[9] The CARING criteria are a unique prognostic tool: (1) CARING is a mnemonic acronym, making it more user friendly to the clinician. (2) The 5 prognostic indicators are readily available from the patient's chart on admission; gathering further data by patient or caretaker interviews or by obtaining laboratory data is not needed. (3) The timing for application of the tool on admission to the hospital is an ideal opportunity to intervene and introduce palliative interventions early on the hospital stay. The CARING criteria were developed and validated in a Veteran's Administration hospital setting by Fischer et al.[9] We sought to validate the CARING criteria in a broader patient populationmedical and surgical patients from a tertiary referral university hospital setting and a safety‐net hospital setting.

METHODS

Study Design

This study was a retrospective observational cohort study. The study was approved by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board and the University of Colorado Hospital Research Review Committee.

Study Purpose

To validate the CARING criteria in a tertiary referral university hospital (University of Colorado Hospital [UCH]) and safety‐net hospital (Denver Health and Hospitals [DHH]) setting using similar methodology to that employed by the original CARING criteria study.[9]

Study Setting/Population

All adults (18 years of age) admitted as inpatients to the medical and surgical services of internal medicine, hospitalist, pulmonary, cardiology, hematology/oncology, hepatology, surgery, intensive care unit, and intermediary care unit at UCH and DHH during the study period of July 2005 through August 2005. The only exclusion criteria were those patients who were prisoners or pregnant. Administrative admission data from July 2005 to August 2005 were used to identify names of all persons admitted to the medicine and surgical services of the study hospitals during the specified time period.

The 2 study hospitals, UCH and DHH, provide a range of patients who vary in ethnicity, socioeconomic status, and medical illness. This variability allows for greater generalizability of the results. Both hospitals are affiliated with the University of Colorado School of Medicine internal medicine residency training program and are located in Denver, Colorado.

At the time of the study, UCH was a licensed 550‐bed tertiary referral, academic hospital serving the Denver metropolitan area and the Rocky Mountain region as a specialty care and referral center. DHH was a 398‐bed, academic, safety‐net hospital serving primarily the Denver metropolitan area. DHH provides 42% of the care for the uninsured in Denver and 26% of the uninsured care for the state of Colorado.

Measures

The CARING criteria were developed and validated in a Veteran's Administration (VA) hospital setting by Fischer et al.[9] The purpose of the CARING criteria is to identify patients, at the time of hospital admission, who are at higher risk of death in the following year. The prognostic index uses 5 predictors that can be abstracted from the chart at time of admission. The CARING criteria were developed a priori, and patients were evaluated using only the medical data available at the time of admission. The criteria include items that are already part of the routine physician admission notes and do not require additional data collection or assessments. The criteria include: C=primary diagnosis of cancer, A=2 admissions to the hospital for a chronic illness within the last year; R=resident in a nursing home; I=intensive care unit (ICU) admission with multiorgan failure (MOF), NG=noncancer hospice guidelines (meeting 2 of the National Hospice and Palliative Care Organization's [NHPCO] guidelines).

Patients were identified using name, date of birth, social security number, address, and phone number. This identifying information was then used for tracing death records 1 year after hospital admission.

Mortality at 1 year following the index hospitalization was the primary end point. To minimize missing data and the number of subjects lost to follow‐up, 3 determinants of mortality were used. First, electronic medical records of the 2 participating hospitals and their outpatient clinics were reviewed to determine if a follow‐up appointment had occurred past the study's end point of 1 year (August 2006). For those without a confirmed follow‐up visit, death records from the Colorado Department of Public Health and Vital Records were obtained. For those patients residing outside of Colorado or whose mortality status was still unclear, the National Death Index was accessed.

Medical Record Review

Medical records for all study participants were reviewed by J.Y. (UCH) and B.C. (DHH). Data collection was completed using direct data entry into a Microsoft Access (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA) database utilizing a data entry form linked with the database table. This form utilized skip patterns and input masks to ensure quality of data entry and minimize missing or invalid data. Inter‐rater reliability was assessed by an independent rereview (S.F.) of 5% of the total charts. Demographic variables were collected using hospital administrative data. These included personal identifiers of the participants for purposes of mortality follow‐up. Clinical data including the 5 CARING variables and additional descriptive variables were abstracted from the paper hospital chart and the electronic record of the chart (together these constitute the medical record).

Death Follow‐up

A search of Colorado death records was conducted in February 2011 for all subjects. Death records were used to determine mortality and time to death from the index hospitalization. The National Death Index was then searched for any subjects without or record of death in Colorado.

Analysis

All analyses were conducted using the statistical application software SAS for Windows version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Simple frequencies and means ( standard deviation) were used to describe the baseline characteristics. Multiple logistic regression models were used to model 1‐year mortality. The models were fitted using all of the CARING variables and age. As the aim of the study was to validate the CARING criteria, the variables for the models were selected a priori based on the original index. Two hospital cohorts (DHH and UCH) were modeled separately and as a combined sample. Kaplan‐Meier survival analysis was conducted to compare those subjects who met 1 of the CARING criteria with those who did not through the entire period of mortality follow‐up (20052011). Finally, using the probabilities from the logistic regression models, we again developed a scoring rule appropriate for a non‐VA setting to allow clinicians to easily identify patient risk for 1‐year mortality at the time of hospital admission.

RESULTS

There were a total of 1064 patients admitted to the medical and surgical services during the study period568 patients at DHH and 496 patients at UCH. Sample characteristics of each individual hospital cohort and the entire combined study cohort are detailed in Table 2. Overall, slightly over half the population were male, with a mean age of 50 years, and the ethnic breakdown roughly reflects the population in Denver. A total of 36.5% (n=388) of the study population met 1 of the CARING criteria, and 12.6% (n=134 among 1063 excluding 1 without an admit date) died within 1 year of the index hospitalization. These were younger and healthier patients compared to the VA sample used in developing the CARING criteria.

| |

| Renal | Dementia |

| Stop/decline dialysis | Unable to ambulate independently |

| Not candidate for transplant | Urinary or fecal incontinence |

| Urine output < 40cc/24 hours | Unable to speak with more than single words |

| Creatinine > 8.0 (>6.0 for diabetics) | Unable to bathe independently |

| Creatinine clearance 10cc/min | Unable to dress independently |

| Uremia | Co‐morbid conditions: |

| Persistent serum K + > 7.0 | Aspiration pneumonia |

| Co‐morbid conditions: | Pyelonephritis |

| Cancer CHF | Decubitus ulcer |

| Chronic lung disease AIDS/HIV | Difficulty swallowing or refusal to eat |

| Sepsis Cirrhosis | |

| Cardiac | Pulmonary |

| Ejection fraction < 20% | Dyspnea at rest |

| Symptomatic with diuretics and vasodilators | FEV1 < 30% |

| Not candidate for transplant | Frequent ER or hospital admits for pulmonary infections or respiratory distress |

| History of cardiac arrest | Cor pulmonale or right heart failure |

| History of syncope | 02 sat < 88% on 02 |

| Systolic BP < 120mmHG | PC02 > 50 |

| CVA cardiac origin | Resting tachycardia > 100/min |

| Co‐morbid conditions as listed in Renal | Co‐morbid conditions as listed in Renal |

| Liver | Stroke/CVA |

| End stage cirrhosis | Coma at onset |

| Not candidate for transplant | Coma >3 days |

| Protime > 5sec and albumin <2.5 | Limb paralysis |

| Ascites unresponsive to treatment | Urinary/fecal incontinence |

| Hepatorenal syndrome | Impaired sitting balance |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | Karnofsky < 50% |

| Spontaneous bacterial peritonitis | Recurrent aspiration |

| Recurrent variceal bleed | Age > 70 |

| Co‐morbid conditions as listed in Renal | Co‐morbid conditions as listed in Renal |

| HIV/AIDS | Neuromuscular |

| Persistent decline in function | Diminished respiratory function |

| Chronic diarrhea 1 year | Chosen not to receive BiPAP/vent |

| Decision to stop treatment | Difficulty swallowing |

| CNS lymphoma | Diminished functional status |

| MAC‐untreated | Incontinence |

| Systemic lymphoma | Co‐morbid conditions as listed in Renal |

| Dilated cardiomyopathy | |

| CD4 < 25 with disease progression | |

| Viral load > 100,000 | |

| Safety‐Net Hospital Cohort, N=568 | Academic Center Cohort, N=496 | Study Cohort,N=1064 | Original CARING Cohort, N=8739 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Mean age ( SD), y | 47.8 (16.5) | 54.4 (17.5) | 50.9 (17.3) | 63 (13) |

| Male gender | 59.5% (338) | 50.1% (248) | 55.1% (586) | 98% (856) |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| African American | 14.1% (80) | 13.5% (65) | 13.8% (145) | 13% (114) |

| Asian | 0.4% (2) | 1.5% (7) | 0.9% (9) | Not reported |

| Caucasian | 41.7% (237) | 66.3% (318) | 53.0 % (555) | 69% (602) |

| Latino | 41.9% (238) | 9.6% (46) | 27.1% (284) | 8% (70) |

| Native American | 0.5% (3) | 0.4% (2) | 0.5% (5) | Not reported |

| Other | 0.5% (3) | 0.6% (3) | 0.6% (6) | 10% (87) |

| Unknown | 0.9% (5) | 8.1% (39) | 4.2% (44) | Not reported |

| CARING criteria | ||||

| Cancer | 6.2% (35) | 19.4% (96) | 12.3% (131) | 23% (201) |

| Admissions to the hospital 2 in past year | 13.6% (77) | 42.7% (212) | 27.2% (289) | 36% (314) |

| Resident in a nursing home | 1.8% (10) | 3.4% (17) | 2.5% (27) | 3% (26) |

| ICU with MOF | 3.7% (21) | 1.2% (6) | 2.5% (27) | 2% (17) |

| NHPCO (2) noncancer guidelines | 1.6% (9) | 5.9% (29) | 3.6% (38) | 8% (70) |

Reliability testing demonstrated excellent inter‐rater reliability. Kappa for each criterion is as follows: (1) primary diagnosis of cancer=1.0, (2) 2 admissions to the hospital in the past year=0.91, (3) resident in a nursing home=1.0, (4) ICU admission with MOF=1.0, and (5) 2 noncancer hospice guidelines=0.78.

This study aimed to validate the CARING criteria9; therefore, all original individual CARING criterion were included in the validation logistic regression models. The 1 exception to this was in the university hospital study cohort, where the ICU criterion was excluded from the model due to small sample size and quasiseparation in the model. The model results are presented in Table 3 for the individual hospitals and combined study cohort.

| Safety Net Hospital Cohort, C Index=0.76 | Academic Center Cohort, C Index=0.76 | Combined Hospital Cohort, C Index=0.79 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Estimate | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Estimate | Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

| ||||||

| Cancer | 1.92 | 6.85 (2.83‐16.59)a | 1.85 | 6.36 (3.54‐11.41)a | 1.98 | 7.23 (4.45‐11.75)a |

| Admissions to the hospital 2 in past year | 0.55 | 1.74 (0.76‐3.97) | 0.14 | 0.87 (0.51‐1.49) | 0.20 | 1.22 (0.78‐1.91) |

| Resident in a nursing home | 0.49 | 0.61 (0.06‐6.56) | 0.27 | 1.31 (0.37‐4.66) | 0.09 | 1.09 (0.36‐3.32) |

| ICU with MOF | 1.85 | 6.34 (2.0219.90)a | 1.94 | 6.97 (2.75‐17.68)a | ||

| NHPCO (2) noncancer guidelines | 3.04 | 20.86 (4.25102.32)a | 2.62 | 13.73 (5.86‐32.15)a | 2.74 | 15.55 (7.2833.23)a |

| Ageb | 0.38 | 1.46 (1.05‐2.03)a | 0.45 | 1.56 (1.23‐1.98)a | 0.47 | 1.60 (1.32‐1.93)a |

In the safety‐net hospital, admission to the hospital with a primary diagnosis related to cancer, 2 noncancer hospice guidelines, ICU admission with MOF, and age by category all were significant predictors of 1‐year mortality. In the university hospital cohort, primary diagnosis of cancer, 2 noncancer hospice guidelines, and age by category were predictive of 1‐year mortality. Finally, in the entire study cohort, primary diagnosis of cancer, ICU with MOF, 2 noncancer hospice guidelines, and age were all predictive of 1‐year mortality. Parameter estimates were similar in 3 of the criteria compared to the VA setting. Differences in patient characteristics may have caused the differences in the estimates. Gender was additionally tested but not significant in any model. One‐year survival was significantly lower for those who met 1 of the CARING criteria versus those who did not (Figure 1).

Based on the framework from the original CARING criteria analysis, a scoring rule was developed using the regression results of this validation cohort. To predict a high probability of 1‐year mortality, sensitivity was set to 58% and specificity was set at 86% (error rate=17%). Medium to high probability was set with a sensitivity of 73% and specificity of 72% (error rate=28%). The coefficients from the regression model of the entire study cohort were converted to scores for each of the CARING criteria. The scores are as follows: 0.5 points for admission from a nursing home, 1 point for 2 hospital admissions in the past year for a chronic illness, 10 points for primary diagnosis of cancer, 10 points for ICU admission with MOF, and 14 points for 2 noncancer hospice guidelines. For every age category increase, 2 points are assigned so that 0 points for age <55 years, 2 points for ages 56 to 65 years, 4 points for ages 66 to 75 years, and 6 points for >75 years. Points for individual risk factors were proportional to s (ie, log odds) in the logistic regression model for death at 1 year. Although no linear transformation exists between s and probabilities (of death at 1 year), the aggregated points for combinations of risk factors shown in Table 4 follow the probabilities in an approximately linear fashion, so that different degrees of risk of death can be represented contiguously (as highlighted by differently shaded regions in the scoring matrix) (Table 4). The scoring matrix allows for quick identification for patients at high risk for 1‐year mortality. In this non‐VA setting with healthier patients, low risk is defined at a lower probability threshold (0.1) compared to the VA setting (0.175).

| CARING Criteria Components | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None | Resident in a Nursing Home | Admitted to the Hospital 2 Times in the Past Year | Resident in a Nursing Home Admitted to the Hospital 2 Times in the Past Year | Primary Diagnosis of Cancer | ICU Admission With MOF | Noncancer Hospice Guidelines | |

| |||||||

| Age | |||||||

| 55 years | 0 | 0.5 | 1 | 1.5 | 10 | ||

| 5565 years | 2 | 2.5 | 3 | 3.5 | 10 | ||

| 6675 years | 4 | 4.5 | 5 | 5.5 | 10 | ||

| >75 years | 6 | 6.5 | 7 | 7.5 | 10 | ||

| Risk | |||||||

| Low | 3.5 | Probability<0.1 | |||||

| Medium | 46.5 | 0.1probability <0.175 | |||||

| High | 7 | Probability0.175 | |||||

DISCUSSION

The CARING criteria are a practical prognostic tool that can be easily and rapidly applied to patients admitted to the hospital to estimate risk of death in 1 year, with the goal of identifying patients who may benefit most from incorporating palliative interventions into their plan of care. This study validated the CARING criteria in a tertiary referral university hospital and safety‐net hospital setting, demonstrating applicability in a much broader population than the VA hospital of the original CARING criteria study. The population studied represented a younger population by over 10 years, a more equitable proportion of males to females, a broader ethnic diversity, and lower 1‐year deaths rates than the original study. Despite the broader representation of the population, the significance of each of the individual CARING criterion was maintained except for 2 hospital admissions in the past year for a chronic illness (admission from a nursing home did not meet significance in either study as a sole criterion). As with the original study, meeting 2 of the NHPCO noncancer hospice guidelines demonstrated the highest risk of 1‐year mortality following index hospitalization, followed by primary diagnosis of cancer and ICU admission with MOF. Advancing age, also similar to the original study, conferred increased risk across the criterion.

Hospitalists could be an effective target for utilizing the CARING criteria because they are frequently the first‐line providers in the hospital setting. With the national shortage of palliative care specialists, hospitalists need to be able to identify when a patient has a limited life expectancy so they will be better equipped to make clinical decisions that are aligned with their patients' values, preferences, and goals of care. With the realization that not addressing advance care planning and patient goals of care may be considered medical errors, primary palliative care skills become alarmingly more important as priorities for hospitalists to obtain and feel comfortable using in daily practice.

The CARING criteria are directly applicable to patients who are seen by hospitalists. Other prognostic indices have focused on select patient populations, such as the elderly,[10, 11, 12] require collection of data that are not readily available on admission or would not otherwise be obtained,[10, 13] or apply to patients post‐hospital discharge, thereby missing the opportunity to make an impact earlier in the disease trajectory and incorporate palliative care into the hospital plan of care when key discussions about goals of care and preferences should be encouraged.

Additionally, the CARING criteria could easily be incorporated as a trigger for palliative care consults on hospital admission. Palliative care consults tend to happen late in a hospital stay, limiting the effectiveness of the palliative care team. A trigger system for hospitalists and other primary providers on hospital admission would lend to more effective timing of palliative measures being incorporated into the plan of care. Palliative care consults would not only be initiated earlier, but could be targeted for the more complex and sick patients with the highest risk of death in the next year.

In the time‐pressured environment, the presence of any 1 of the CARING criteria can act as a trigger to begin incorporating primary palliative care measures into the plan of care. The admitting hospitalist provider (ie, physician, nurse practitioner, physician assistant) could access the CARING criteria through an electronic health record prompt when admitting patients. When a more detailed assessment of mortality risk is helpful, the hospitalist can use the scoring matrix, which combines age with the individual criterion to calculate patients at medium or high risk of death within 1 year. Limited resources can then be directed to the patients with the greatest need. Patients with a focused care need, such as advance care planning or hospice referral, can be directed to the social worker or case manager. More complicated patients may be referred to a specialty palliative care team.

Several limitations to this study are recognized, including the small sample size of patients meeting criterion for ICU with MOF in the academic center study cohort. The patient data were collected during a transition time when the university hospital moved to a new campus, resulting in an ICU at each campus that housed patients with differing levels of illness severity, which may have contributed to the lower acuity ICU patient observed. Although we advocate the simplicity of the CARING criteria, the NHPCO noncancer hospice guidelines are more complicated, as they incorporates 8 broad categories of chronic illness. The hospice guidelines may not be general knowledge to the hospitalist or other primary providers. ePrognosis (

CONCLUSION

The CARING criteria are a simple, practical prognostic tool predictive of death within 1 year that has been validated in a broad population of hospitalized patients. The criteria hold up in a younger, healthier population that is more diverse by age, gender, and ethnicity than the VA population. With ready access to critical prognostic information on hospital admission, clinicians will be better informed to make decisions that are aligned with their patients' values, preferences, and goals of care.

Disclosure

Nothing to report.

- , , . Predicting death: an empirical evaluation of predictive tools for mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1721–1726.

- , . Extent and determinants of error in physicians' prognoses in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort study. West J Med. 2000;172:310–313.

- , , , et al. A systematic review of physicians' survival predictions in terminally ill cancer patients. BMJ. 2003;327:195–198.

- , . Attitude and self‐reported practice regarding prognostication in a national sample of internists. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2389–2395.

- , , , et al. Discussing prognosis: balancing hope and realism. Cancer J. 2010;16:461–466.

- , , , . Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) IV: hospital mortality assessment for today's critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1297–1310.

- , , , , . SAPS 3 admission score: an external validation in a general intensive care population. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:1873–1877.

- , , , , , . Prospective validation of the intensive care unit admission Mortality Probability Model (MPM0‐III). Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1619–1623.

- , , , , , . A practical tool to identify patients who may benefit from a palliative approach: the CARING criteria. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31:285–292.

- , , , et al. Prediction of survival for older hospitalized patients: the HELP survival model. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:S16–S24.

- , , , et al. Development and validation of a multidimensional prognostic index for one‐year mortality from comprehensive geriatric assessment in hospitalized older patients. Rejuvenation Res. 2008;11:151–161.

- , , , et al. Burden of illness score for elderly persons: risk adjustment incorporating the cumulative impact of diseases, physiologic abnormalities, and functional impairments. Med Care. 2003;41:70–83.

- , , , et al. The SUPPORT prognostic model. Objective estimates of survival for seriously ill hospitalized adults. Study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:191–203.

- , , . Predicting death: an empirical evaluation of predictive tools for mortality. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171:1721–1726.

- , . Extent and determinants of error in physicians' prognoses in terminally ill patients: prospective cohort study. West J Med. 2000;172:310–313.

- , , , et al. A systematic review of physicians' survival predictions in terminally ill cancer patients. BMJ. 2003;327:195–198.

- , . Attitude and self‐reported practice regarding prognostication in a national sample of internists. Arch Intern Med. 1998;158:2389–2395.

- , , , et al. Discussing prognosis: balancing hope and realism. Cancer J. 2010;16:461–466.

- , , , . Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation (APACHE) IV: hospital mortality assessment for today's critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1297–1310.

- , , , , . SAPS 3 admission score: an external validation in a general intensive care population. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:1873–1877.

- , , , , , . Prospective validation of the intensive care unit admission Mortality Probability Model (MPM0‐III). Crit Care Med. 2009;37:1619–1623.

- , , , , , . A practical tool to identify patients who may benefit from a palliative approach: the CARING criteria. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;31:285–292.

- , , , et al. Prediction of survival for older hospitalized patients: the HELP survival model. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000;48:S16–S24.

- , , , et al. Development and validation of a multidimensional prognostic index for one‐year mortality from comprehensive geriatric assessment in hospitalized older patients. Rejuvenation Res. 2008;11:151–161.

- , , , et al. Burden of illness score for elderly persons: risk adjustment incorporating the cumulative impact of diseases, physiologic abnormalities, and functional impairments. Med Care. 2003;41:70–83.

- , , , et al. The SUPPORT prognostic model. Objective estimates of survival for seriously ill hospitalized adults. Study to understand prognoses and preferences for outcomes and risks of treatments. Ann Intern Med. 1995;122:191–203.

© 2013 Society of Hospital Medicine