User login

Individuals spend close to half of their lives preventing, or planning for, pregnancy. As such, contraception plays a major role in patient-provider interactions. Contraception counseling and management is a common scenario encountered in the general gynecologist’s practice. Luckily, we have two evidence-based guidelines developed by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that support the provision of contraceptive care:

- US Medical Eligibility for Contraceptive Use (US-MEC),1 which provides guidance on which patients can safely use a method

- US Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use (US-SPR),2 which provides method-specific guidance on how to use a method (including how to: initiate or start a method; manage adherence issues, such as a missed pill, etc; and manage common issues like breakthrough bleeding). Both of these guidelines are updated routinely and are publicly available online or for free, through smartphone applications.

While most contraceptive care is straightforward, there are circumstances that require additional consideration. In this 3-part series we review 3 clinical cases, existing evidence to guide management decisions, and our recommendations. In part 1, we focus on restarting hormonal contraception after ulipristal acetate administration. In parts 2 and 3, we will discuss removal of a nonpalpable contraceptive implant and the consideration of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) for emergency contraception.

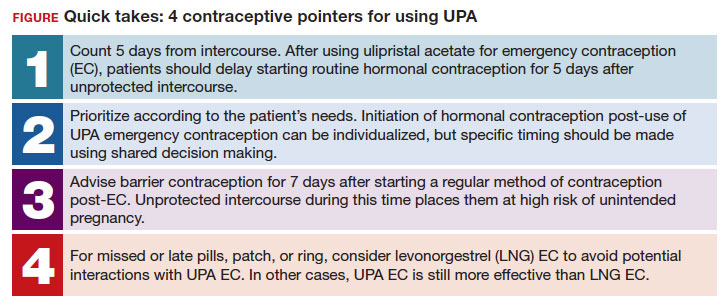

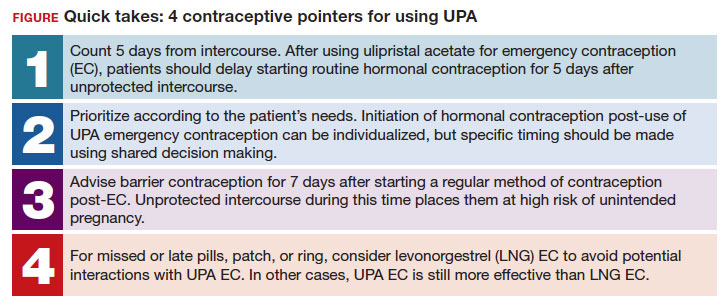

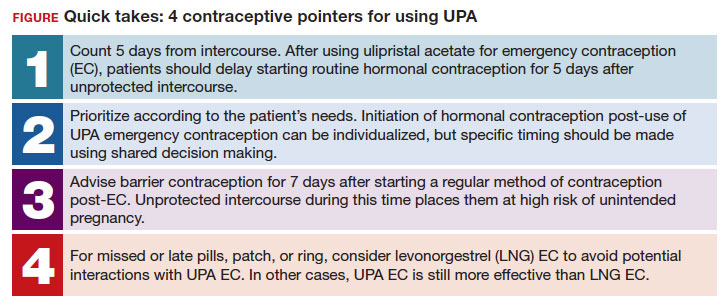

- After using ulipristal acetate for emergency contraception, advise patients to wait at least 5 days to initiate hormonal contraception and about the importance of abstaining or using a back-up method for another 7 days with the start of their hormonal contraceptive method

CASE Meeting emergency and follow-up contraception needs

A 27-year-old woman (G0) presents to you after having unprotected intercourse 4 days ago. She does not formally track her menstrual cycles and is unsure when her last menstrual period was. She is not using contraception but is interested in starting a method. After counseling, she elects to take a dose of oral ulipristal acetate (UPA; Ella) now for emergency contraception and would like to start a combined oral contraceptive (COC) pill moving forward.

How soon after taking UPA should you tell her to start the combined hormonal pill?

Effectiveness of hormonal contraception following UPA

UPA does not appear to decrease the efficacy of COCs when started around the same time. However, immediately starting a hormonal contraceptive can decrease the effectiveness of UPA, and as such, it is recommended to take UPA and then abstain or use a backup method for 7 days before initiating a hormonal contraceptive method.1 By obtaining some additional information from your patient and with the use of shared decision making, though, your patient may be able to start their contraceptive method earlier than 5 days after UPA.

What is UPA

UPA is a progesterone receptor modulator used for emergency contraception intenhded to prevent pregnancy after unprotected intercourse or contraceptive failure.3 It works by delaying follicular rupture at least 5 days, if taken before the peak of the luteinizing hormone (LH) surge. If taken after that timeframe, it does not work. Since UPA competes for the progesterone receptor, there is a concern that the effectiveness of UPA may be decreased if a progestin-containing form of contraception is started immediately after taking UPA, or vice versa.4 Several studies have now specifically looked at the interaction between UPA and progestin-containing contraceptives, including at how UPA is impacted by the contraceptive method, and conversely, how the contraceptive method is impacted by UPA.5-8

Data on types of hormonal contraception. Brache and colleagues demonstrated that UPA users who started a desogestrel progestin-only pill (DSG POP) the next day had higher rates of ovulation within 5 days of taking UPA (45%), compared with those who the next day started a placebo pill (3%).6 This type of progestin-only pill is not available in the United States.

A study by Edelman and colleagues demonstrated similar findings in those starting a COC pill containing estrogen and progestin. When taking a COC two days after UPA use, more participants had evidence of follicular rupture in less than 5 days.5 It should be noted that these studies focused on ovulation, which—while necessary for conception to occur—is a surrogate biomarker for pregnancy risk. Additional studies have looked at the impact of UPA on the COC and have not found that UPA impacts ovulation suppression of the COC with its initiation or use.8

Considering unprotected intercourse and UPA timing. Of course, the risk of pregnancy is reliant on cycle timing plus the presence of viable sperm in the reproductive tract. Sperm have been shown to only be viable in the reproductive tract for 5 days, which could result in fertilization and subsequent pregnancy. Longevity of an egg is much shorter, at 12 to 24 hours after ovulation. For this patient, her exposure was 4 days ago, but sperm are only viable for approximately 5 days—she could consider taking the UPA now and then starting a COC earlier than 5 days since she only needs an extra day or two of protection from the UPA from the sperm in her reproductive tract. Your patient’s involvement in this decision making is paramount, as only they can prioritize their desire to avoid pregnancy from their recent act of unprotected intercourse versus their immediate needs for starting their method of contraception. It is important that individuals abstain from sexual activity or use an additional back-up method during the first 7 days of starting their method of contraception.

Continue to: Counseling considerations for the case patient...

Counseling considerations for the case patient

For a patient planning to start or resume a hormonal contraceptive method after taking UPA, the waiting period recommended by the CDC (5 days) is most beneficial for patients who are uncertain about their menstrual cycle timing in relation to the act of unprotected intercourse that already occurred and need to prioritize maximum effectiveness of emergency contraception.

Patients with unsure cycle-sex timing planning to self-start or resume a short-term hormonal contraceptive method (eg, pills, patches, or rings), should be counseled to wait 5 days after the most recent act of unprotected sex, before taking their hormonal contraceptive method.7 Patients with unsure cycle-sex timing planning to use provider-dependent hormonal contraceptive methods (eg, those requiring a prescription, including a progestin-contraceptive implant or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate) should also be counseled to wait. Timing of levonorgestrel and copper intrauterine devices are addressed in part 3 of this series.

However, if your patient has a good understanding of their menstrual cycle, and the primary concern is exposure from subsequent sexual encounters and not the recent unprotected intercourse, it is advisable to provide UPA and immediately initiate a contraceptive method. One of the primary reasons for emergency contraception failure is that its effectiveness is limited to the most recent act of unprotected sexual intercourse and does not extend to subsequent acts throughout the month.

For these patients with sure cycle-sex timing who are planning to start or resume short-or long-term contraceptive methods, and whose primary concern is to prevent pregnancy risk from subsequent sexual encounters, immediately initiating a contraceptive method is advisable. For provider-dependent methods, we must weigh the risk of unintended pregnancy from the act of intercourse that already occurred (and the potential to increase that risk by initiating a method that could compromise UPA efficacy) versus the future risk of pregnancy if the patient cannot return for a contraception visit.7

In short, starting the contraceptive method at the time of UPA use can be considered after shared decision making with the patient and understanding what their primary concerns are.

Important point

Counsel on using backup barrier contraception after UPA

Oral emergency contraception only covers that one act of unprotected intercourse and does not continue to protect a patient from pregnancy for the rest of their cycle. When taken before ovulation, UPA works by delaying follicular development and rupture for at least 5 days. Patients who continue to have unprotected intercourse after taking UPA are at a high risk of an unintended pregnancy from this ‘stalled’ follicle that will eventually ovulate. Follicular maturation resumes after UPA’s effects wane, and the patient is primed for ovulation (and therefore unintended pregnancy) if ongoing unprotected intercourse occurs for the rest of their cycle.

Therefore, it is important to counsel patients on the need, if they do not desire a pregnancy, to abstain or start a method of contraception.

Final question

What about starting or resuming non–hormonal contraceptive methods?

Non-hormonal contraceptive methods can be started immediately with UPA use.1

CASE Resolved

After shared decision making, the patient decides to start using the COC pill. You prescribe her both UPA for emergency contraception and a combined hormonal contraceptive pill. Given her unsure cycle-sex timing, she expresses to you that her most important priority is preventing unintended pregnancy. You counsel her to set a reminder on her phone to start taking the pill 5 days from her most recent act of unprotected intercourse. You also counsel her to use a back-up barrier method of contraception for 7 days after starting her COC pill. ●

- Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2016. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1-66. https://doi .org/10.15585/mmwr.rr6504a1

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Reproductive Health. US Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use (US-SPR). Accessed October 11, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth /contraception/mmwr/spr/summary.html

- Ella [package insert]. Charleston, SC; Afaxys, Inc. 2014.

- Salcedo J, Rodriguez MI, Curtis KM, et al. When can a woman resume or initiate contraception after taking emergency contraceptive pills? A systematic review. Contraception. 2013;87:602-604. https://doi.org/10.1016 /j.contraception.2012.08.013

- Edelman AB, Jensen JT, McCrimmon S, et al. Combined oral contraceptive interference with the ability of ulipristal acetate to delay ovulation: a prospective cohort study. Contraception. 2018;98:463-466. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2018.08.003

- Brache V, Cochon L, Duijkers IJM, et al. A prospective, randomized, pharmacodynamic study of quick-starting a desogestrel progestin-only pill following ulipristal acetate for emergency contraception. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2015;30:2785-2793. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep /dev241

- Cameron ST, Berger C, Michie L, et al. The effects on ovarian activity of ulipristal acetate when ‘quickstarting’ a combined oral contraceptive pill: a prospective, randomized, doubleblind parallel-arm, placebo-controlled study. Hum Reprod. 2015;30:1566-1572. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev115

- Banh C, Rautenberg T, Diujkers I, et al. The effects on ovarian activity of delaying versus immediately restarting combined oral contraception after missing three pills and taking ulipristal acetate 30 mg. Contraception. 2020;102:145-151. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2020.05.013

- American Society for Emergency Contraception. Providing ongoing hormonal contraception after use of emergency contraceptive pills. September 2016. Accessed October 11, 2023. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj /https://www.americansocietyforec.org/_files/ugd/7f2e0b _ff1bc90bea204644ba28d1b0e6a6a6a8.pdf

Individuals spend close to half of their lives preventing, or planning for, pregnancy. As such, contraception plays a major role in patient-provider interactions. Contraception counseling and management is a common scenario encountered in the general gynecologist’s practice. Luckily, we have two evidence-based guidelines developed by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that support the provision of contraceptive care:

- US Medical Eligibility for Contraceptive Use (US-MEC),1 which provides guidance on which patients can safely use a method

- US Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use (US-SPR),2 which provides method-specific guidance on how to use a method (including how to: initiate or start a method; manage adherence issues, such as a missed pill, etc; and manage common issues like breakthrough bleeding). Both of these guidelines are updated routinely and are publicly available online or for free, through smartphone applications.

While most contraceptive care is straightforward, there are circumstances that require additional consideration. In this 3-part series we review 3 clinical cases, existing evidence to guide management decisions, and our recommendations. In part 1, we focus on restarting hormonal contraception after ulipristal acetate administration. In parts 2 and 3, we will discuss removal of a nonpalpable contraceptive implant and the consideration of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) for emergency contraception.

- After using ulipristal acetate for emergency contraception, advise patients to wait at least 5 days to initiate hormonal contraception and about the importance of abstaining or using a back-up method for another 7 days with the start of their hormonal contraceptive method

CASE Meeting emergency and follow-up contraception needs

A 27-year-old woman (G0) presents to you after having unprotected intercourse 4 days ago. She does not formally track her menstrual cycles and is unsure when her last menstrual period was. She is not using contraception but is interested in starting a method. After counseling, she elects to take a dose of oral ulipristal acetate (UPA; Ella) now for emergency contraception and would like to start a combined oral contraceptive (COC) pill moving forward.

How soon after taking UPA should you tell her to start the combined hormonal pill?

Effectiveness of hormonal contraception following UPA

UPA does not appear to decrease the efficacy of COCs when started around the same time. However, immediately starting a hormonal contraceptive can decrease the effectiveness of UPA, and as such, it is recommended to take UPA and then abstain or use a backup method for 7 days before initiating a hormonal contraceptive method.1 By obtaining some additional information from your patient and with the use of shared decision making, though, your patient may be able to start their contraceptive method earlier than 5 days after UPA.

What is UPA

UPA is a progesterone receptor modulator used for emergency contraception intenhded to prevent pregnancy after unprotected intercourse or contraceptive failure.3 It works by delaying follicular rupture at least 5 days, if taken before the peak of the luteinizing hormone (LH) surge. If taken after that timeframe, it does not work. Since UPA competes for the progesterone receptor, there is a concern that the effectiveness of UPA may be decreased if a progestin-containing form of contraception is started immediately after taking UPA, or vice versa.4 Several studies have now specifically looked at the interaction between UPA and progestin-containing contraceptives, including at how UPA is impacted by the contraceptive method, and conversely, how the contraceptive method is impacted by UPA.5-8

Data on types of hormonal contraception. Brache and colleagues demonstrated that UPA users who started a desogestrel progestin-only pill (DSG POP) the next day had higher rates of ovulation within 5 days of taking UPA (45%), compared with those who the next day started a placebo pill (3%).6 This type of progestin-only pill is not available in the United States.

A study by Edelman and colleagues demonstrated similar findings in those starting a COC pill containing estrogen and progestin. When taking a COC two days after UPA use, more participants had evidence of follicular rupture in less than 5 days.5 It should be noted that these studies focused on ovulation, which—while necessary for conception to occur—is a surrogate biomarker for pregnancy risk. Additional studies have looked at the impact of UPA on the COC and have not found that UPA impacts ovulation suppression of the COC with its initiation or use.8

Considering unprotected intercourse and UPA timing. Of course, the risk of pregnancy is reliant on cycle timing plus the presence of viable sperm in the reproductive tract. Sperm have been shown to only be viable in the reproductive tract for 5 days, which could result in fertilization and subsequent pregnancy. Longevity of an egg is much shorter, at 12 to 24 hours after ovulation. For this patient, her exposure was 4 days ago, but sperm are only viable for approximately 5 days—she could consider taking the UPA now and then starting a COC earlier than 5 days since she only needs an extra day or two of protection from the UPA from the sperm in her reproductive tract. Your patient’s involvement in this decision making is paramount, as only they can prioritize their desire to avoid pregnancy from their recent act of unprotected intercourse versus their immediate needs for starting their method of contraception. It is important that individuals abstain from sexual activity or use an additional back-up method during the first 7 days of starting their method of contraception.

Continue to: Counseling considerations for the case patient...

Counseling considerations for the case patient

For a patient planning to start or resume a hormonal contraceptive method after taking UPA, the waiting period recommended by the CDC (5 days) is most beneficial for patients who are uncertain about their menstrual cycle timing in relation to the act of unprotected intercourse that already occurred and need to prioritize maximum effectiveness of emergency contraception.

Patients with unsure cycle-sex timing planning to self-start or resume a short-term hormonal contraceptive method (eg, pills, patches, or rings), should be counseled to wait 5 days after the most recent act of unprotected sex, before taking their hormonal contraceptive method.7 Patients with unsure cycle-sex timing planning to use provider-dependent hormonal contraceptive methods (eg, those requiring a prescription, including a progestin-contraceptive implant or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate) should also be counseled to wait. Timing of levonorgestrel and copper intrauterine devices are addressed in part 3 of this series.

However, if your patient has a good understanding of their menstrual cycle, and the primary concern is exposure from subsequent sexual encounters and not the recent unprotected intercourse, it is advisable to provide UPA and immediately initiate a contraceptive method. One of the primary reasons for emergency contraception failure is that its effectiveness is limited to the most recent act of unprotected sexual intercourse and does not extend to subsequent acts throughout the month.

For these patients with sure cycle-sex timing who are planning to start or resume short-or long-term contraceptive methods, and whose primary concern is to prevent pregnancy risk from subsequent sexual encounters, immediately initiating a contraceptive method is advisable. For provider-dependent methods, we must weigh the risk of unintended pregnancy from the act of intercourse that already occurred (and the potential to increase that risk by initiating a method that could compromise UPA efficacy) versus the future risk of pregnancy if the patient cannot return for a contraception visit.7

In short, starting the contraceptive method at the time of UPA use can be considered after shared decision making with the patient and understanding what their primary concerns are.

Important point

Counsel on using backup barrier contraception after UPA

Oral emergency contraception only covers that one act of unprotected intercourse and does not continue to protect a patient from pregnancy for the rest of their cycle. When taken before ovulation, UPA works by delaying follicular development and rupture for at least 5 days. Patients who continue to have unprotected intercourse after taking UPA are at a high risk of an unintended pregnancy from this ‘stalled’ follicle that will eventually ovulate. Follicular maturation resumes after UPA’s effects wane, and the patient is primed for ovulation (and therefore unintended pregnancy) if ongoing unprotected intercourse occurs for the rest of their cycle.

Therefore, it is important to counsel patients on the need, if they do not desire a pregnancy, to abstain or start a method of contraception.

Final question

What about starting or resuming non–hormonal contraceptive methods?

Non-hormonal contraceptive methods can be started immediately with UPA use.1

CASE Resolved

After shared decision making, the patient decides to start using the COC pill. You prescribe her both UPA for emergency contraception and a combined hormonal contraceptive pill. Given her unsure cycle-sex timing, she expresses to you that her most important priority is preventing unintended pregnancy. You counsel her to set a reminder on her phone to start taking the pill 5 days from her most recent act of unprotected intercourse. You also counsel her to use a back-up barrier method of contraception for 7 days after starting her COC pill. ●

Individuals spend close to half of their lives preventing, or planning for, pregnancy. As such, contraception plays a major role in patient-provider interactions. Contraception counseling and management is a common scenario encountered in the general gynecologist’s practice. Luckily, we have two evidence-based guidelines developed by the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that support the provision of contraceptive care:

- US Medical Eligibility for Contraceptive Use (US-MEC),1 which provides guidance on which patients can safely use a method

- US Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use (US-SPR),2 which provides method-specific guidance on how to use a method (including how to: initiate or start a method; manage adherence issues, such as a missed pill, etc; and manage common issues like breakthrough bleeding). Both of these guidelines are updated routinely and are publicly available online or for free, through smartphone applications.

While most contraceptive care is straightforward, there are circumstances that require additional consideration. In this 3-part series we review 3 clinical cases, existing evidence to guide management decisions, and our recommendations. In part 1, we focus on restarting hormonal contraception after ulipristal acetate administration. In parts 2 and 3, we will discuss removal of a nonpalpable contraceptive implant and the consideration of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine device (LNG-IUD) for emergency contraception.

- After using ulipristal acetate for emergency contraception, advise patients to wait at least 5 days to initiate hormonal contraception and about the importance of abstaining or using a back-up method for another 7 days with the start of their hormonal contraceptive method

CASE Meeting emergency and follow-up contraception needs

A 27-year-old woman (G0) presents to you after having unprotected intercourse 4 days ago. She does not formally track her menstrual cycles and is unsure when her last menstrual period was. She is not using contraception but is interested in starting a method. After counseling, she elects to take a dose of oral ulipristal acetate (UPA; Ella) now for emergency contraception and would like to start a combined oral contraceptive (COC) pill moving forward.

How soon after taking UPA should you tell her to start the combined hormonal pill?

Effectiveness of hormonal contraception following UPA

UPA does not appear to decrease the efficacy of COCs when started around the same time. However, immediately starting a hormonal contraceptive can decrease the effectiveness of UPA, and as such, it is recommended to take UPA and then abstain or use a backup method for 7 days before initiating a hormonal contraceptive method.1 By obtaining some additional information from your patient and with the use of shared decision making, though, your patient may be able to start their contraceptive method earlier than 5 days after UPA.

What is UPA

UPA is a progesterone receptor modulator used for emergency contraception intenhded to prevent pregnancy after unprotected intercourse or contraceptive failure.3 It works by delaying follicular rupture at least 5 days, if taken before the peak of the luteinizing hormone (LH) surge. If taken after that timeframe, it does not work. Since UPA competes for the progesterone receptor, there is a concern that the effectiveness of UPA may be decreased if a progestin-containing form of contraception is started immediately after taking UPA, or vice versa.4 Several studies have now specifically looked at the interaction between UPA and progestin-containing contraceptives, including at how UPA is impacted by the contraceptive method, and conversely, how the contraceptive method is impacted by UPA.5-8

Data on types of hormonal contraception. Brache and colleagues demonstrated that UPA users who started a desogestrel progestin-only pill (DSG POP) the next day had higher rates of ovulation within 5 days of taking UPA (45%), compared with those who the next day started a placebo pill (3%).6 This type of progestin-only pill is not available in the United States.

A study by Edelman and colleagues demonstrated similar findings in those starting a COC pill containing estrogen and progestin. When taking a COC two days after UPA use, more participants had evidence of follicular rupture in less than 5 days.5 It should be noted that these studies focused on ovulation, which—while necessary for conception to occur—is a surrogate biomarker for pregnancy risk. Additional studies have looked at the impact of UPA on the COC and have not found that UPA impacts ovulation suppression of the COC with its initiation or use.8

Considering unprotected intercourse and UPA timing. Of course, the risk of pregnancy is reliant on cycle timing plus the presence of viable sperm in the reproductive tract. Sperm have been shown to only be viable in the reproductive tract for 5 days, which could result in fertilization and subsequent pregnancy. Longevity of an egg is much shorter, at 12 to 24 hours after ovulation. For this patient, her exposure was 4 days ago, but sperm are only viable for approximately 5 days—she could consider taking the UPA now and then starting a COC earlier than 5 days since she only needs an extra day or two of protection from the UPA from the sperm in her reproductive tract. Your patient’s involvement in this decision making is paramount, as only they can prioritize their desire to avoid pregnancy from their recent act of unprotected intercourse versus their immediate needs for starting their method of contraception. It is important that individuals abstain from sexual activity or use an additional back-up method during the first 7 days of starting their method of contraception.

Continue to: Counseling considerations for the case patient...

Counseling considerations for the case patient

For a patient planning to start or resume a hormonal contraceptive method after taking UPA, the waiting period recommended by the CDC (5 days) is most beneficial for patients who are uncertain about their menstrual cycle timing in relation to the act of unprotected intercourse that already occurred and need to prioritize maximum effectiveness of emergency contraception.

Patients with unsure cycle-sex timing planning to self-start or resume a short-term hormonal contraceptive method (eg, pills, patches, or rings), should be counseled to wait 5 days after the most recent act of unprotected sex, before taking their hormonal contraceptive method.7 Patients with unsure cycle-sex timing planning to use provider-dependent hormonal contraceptive methods (eg, those requiring a prescription, including a progestin-contraceptive implant or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate) should also be counseled to wait. Timing of levonorgestrel and copper intrauterine devices are addressed in part 3 of this series.

However, if your patient has a good understanding of their menstrual cycle, and the primary concern is exposure from subsequent sexual encounters and not the recent unprotected intercourse, it is advisable to provide UPA and immediately initiate a contraceptive method. One of the primary reasons for emergency contraception failure is that its effectiveness is limited to the most recent act of unprotected sexual intercourse and does not extend to subsequent acts throughout the month.

For these patients with sure cycle-sex timing who are planning to start or resume short-or long-term contraceptive methods, and whose primary concern is to prevent pregnancy risk from subsequent sexual encounters, immediately initiating a contraceptive method is advisable. For provider-dependent methods, we must weigh the risk of unintended pregnancy from the act of intercourse that already occurred (and the potential to increase that risk by initiating a method that could compromise UPA efficacy) versus the future risk of pregnancy if the patient cannot return for a contraception visit.7

In short, starting the contraceptive method at the time of UPA use can be considered after shared decision making with the patient and understanding what their primary concerns are.

Important point

Counsel on using backup barrier contraception after UPA

Oral emergency contraception only covers that one act of unprotected intercourse and does not continue to protect a patient from pregnancy for the rest of their cycle. When taken before ovulation, UPA works by delaying follicular development and rupture for at least 5 days. Patients who continue to have unprotected intercourse after taking UPA are at a high risk of an unintended pregnancy from this ‘stalled’ follicle that will eventually ovulate. Follicular maturation resumes after UPA’s effects wane, and the patient is primed for ovulation (and therefore unintended pregnancy) if ongoing unprotected intercourse occurs for the rest of their cycle.

Therefore, it is important to counsel patients on the need, if they do not desire a pregnancy, to abstain or start a method of contraception.

Final question

What about starting or resuming non–hormonal contraceptive methods?

Non-hormonal contraceptive methods can be started immediately with UPA use.1

CASE Resolved

After shared decision making, the patient decides to start using the COC pill. You prescribe her both UPA for emergency contraception and a combined hormonal contraceptive pill. Given her unsure cycle-sex timing, she expresses to you that her most important priority is preventing unintended pregnancy. You counsel her to set a reminder on her phone to start taking the pill 5 days from her most recent act of unprotected intercourse. You also counsel her to use a back-up barrier method of contraception for 7 days after starting her COC pill. ●

- Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2016. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1-66. https://doi .org/10.15585/mmwr.rr6504a1

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Reproductive Health. US Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use (US-SPR). Accessed October 11, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth /contraception/mmwr/spr/summary.html

- Ella [package insert]. Charleston, SC; Afaxys, Inc. 2014.

- Salcedo J, Rodriguez MI, Curtis KM, et al. When can a woman resume or initiate contraception after taking emergency contraceptive pills? A systematic review. Contraception. 2013;87:602-604. https://doi.org/10.1016 /j.contraception.2012.08.013

- Edelman AB, Jensen JT, McCrimmon S, et al. Combined oral contraceptive interference with the ability of ulipristal acetate to delay ovulation: a prospective cohort study. Contraception. 2018;98:463-466. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2018.08.003

- Brache V, Cochon L, Duijkers IJM, et al. A prospective, randomized, pharmacodynamic study of quick-starting a desogestrel progestin-only pill following ulipristal acetate for emergency contraception. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2015;30:2785-2793. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep /dev241

- Cameron ST, Berger C, Michie L, et al. The effects on ovarian activity of ulipristal acetate when ‘quickstarting’ a combined oral contraceptive pill: a prospective, randomized, doubleblind parallel-arm, placebo-controlled study. Hum Reprod. 2015;30:1566-1572. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev115

- Banh C, Rautenberg T, Diujkers I, et al. The effects on ovarian activity of delaying versus immediately restarting combined oral contraception after missing three pills and taking ulipristal acetate 30 mg. Contraception. 2020;102:145-151. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2020.05.013

- American Society for Emergency Contraception. Providing ongoing hormonal contraception after use of emergency contraceptive pills. September 2016. Accessed October 11, 2023. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj /https://www.americansocietyforec.org/_files/ugd/7f2e0b _ff1bc90bea204644ba28d1b0e6a6a6a8.pdf

- Curtis KM, Jatlaoui TC, Tepper NK, et al. U.S. Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use, 2016. Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:1-66. https://doi .org/10.15585/mmwr.rr6504a1

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Division of Reproductive Health. US Selected Practice Recommendations for Contraceptive Use (US-SPR). Accessed October 11, 2023. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth /contraception/mmwr/spr/summary.html

- Ella [package insert]. Charleston, SC; Afaxys, Inc. 2014.

- Salcedo J, Rodriguez MI, Curtis KM, et al. When can a woman resume or initiate contraception after taking emergency contraceptive pills? A systematic review. Contraception. 2013;87:602-604. https://doi.org/10.1016 /j.contraception.2012.08.013

- Edelman AB, Jensen JT, McCrimmon S, et al. Combined oral contraceptive interference with the ability of ulipristal acetate to delay ovulation: a prospective cohort study. Contraception. 2018;98:463-466. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2018.08.003

- Brache V, Cochon L, Duijkers IJM, et al. A prospective, randomized, pharmacodynamic study of quick-starting a desogestrel progestin-only pill following ulipristal acetate for emergency contraception. Hum Reprod Oxf Engl. 2015;30:2785-2793. https://doi.org/10.1093/humrep /dev241

- Cameron ST, Berger C, Michie L, et al. The effects on ovarian activity of ulipristal acetate when ‘quickstarting’ a combined oral contraceptive pill: a prospective, randomized, doubleblind parallel-arm, placebo-controlled study. Hum Reprod. 2015;30:1566-1572. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dev115

- Banh C, Rautenberg T, Diujkers I, et al. The effects on ovarian activity of delaying versus immediately restarting combined oral contraception after missing three pills and taking ulipristal acetate 30 mg. Contraception. 2020;102:145-151. doi: 10.1016/j.contraception.2020.05.013

- American Society for Emergency Contraception. Providing ongoing hormonal contraception after use of emergency contraceptive pills. September 2016. Accessed October 11, 2023. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj /https://www.americansocietyforec.org/_files/ugd/7f2e0b _ff1bc90bea204644ba28d1b0e6a6a6a8.pdf