User login

Case Report

A 66-year-old non-Hispanic white man with a history of adult-onset seizures, renal cell carcinoma, and nephrolithiasis presented to the dermatology clinic with numerous dark red, dry, scaling lesions on the lower legs, abdomen, back, thighs, and scrotum that bled easily. The lesions had developed 2 to 4 years prior to presentation. The patient also noted several dark blue lesions on the bilateral arms that had been present for several years.

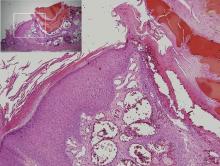

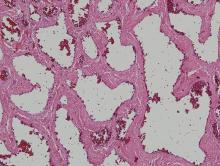

Physical examination revealed multiple black, keratotic papules on the bilateral lower legs (Figure 1), with similar lesions on the lower abdomen and lower back. Numerous dark red, scaling papules were present on the thighs and scrotum, and firm, 1- to 3-cm, dark blue nodules were noted on the bilateral arms (Figure 2) and right side of the forehead. Biopsy of papules from the lower right leg and back demonstrated angiokeratomas on pathologic review (Figure 3). Four separate biopsies taken from the left forearm demonstrated lobular and cavernous hemangiomas (Figure 4).

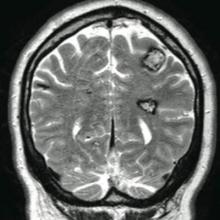

The patient’s medical history was remarkable for neurologic symptoms including adult-onset seizures at the age of 42 years. Recent magnetic resonance imaging of the head showed multiple areas of heterogeneous signal intensity with T2 hypointense rims consistent with cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs) involving both cerebral hemispheres, the posterior cranial fossa, and the brainstem (Figure 5). Of note, the patient’s mother had been diagnosed with epilepsy in her 40s, but no other family history of a clinically or radiographically diagnosed neurologic disorder was reported.

This presentation of numerous CCMs and cutaneous vascular lesions prompted genetic testing for mutations in the 3 CCM genes. Bidirectional sequencing from a blood specimen confirmed a 1267C→T substitution resulting in an Arg423X nonsense mutation in the KRIT1, ankyrin repeat containing gene (also known as CCM1) on chromosome 7, which is a published mutation.1 No treatment of the cutaneous lesions was administered. The patient continued to be treated by a neurologist for the seizure disorder after genetic testing and counseling was complete.

Comment

Cerebral cavernous malformations represent collections of dilated, capillarylike vessels without intervening brain parenchyma,2 which can occur as a sporadic or autosomal-dominant condition with variable prevalence. Imaging and autopsy studies suggest CCMs may be present in 0.5% of the general population, with the incidence of clinically symptomatic disease being much lower.3,4 While sporadic cases are usually associated with the presence of a single CCM, hereditary cases generally display multiple CCMs5-7; studies indicate that most patients who present with symptomatic CCMs are in the second to fifth decades of life.3,8-10 The most common clinical manifestations of CCMs are headaches, seizures, and focal neurologic deficits due to cerebral hemorrhages.11

Three autosomal-dominant forms of familial CCMs are associated with several different heterozygous mutations in the CCM1 gene, which encodes Krev interaction trapped protein 1; the cerebral cavernous malformation 2 gene (CCM2), which encodes the protein malcavernin; and the programmed cell death 10 gene (PDCD10)(also known as CCM3), which encodes the PDCD10 protein.12-14 Although the precise pathophysiologic mechanisms linking these mutations with the resultant clinical phenotypes have yet to be fully elucidated, these genes are thought to play roles in angiogenesis as well as vascular maintenance and remodeling.11 Among non-Hispanic white kindreds with familial CCMs, 40% to 72% of kindreds were linked to mutations in CCM1, 20% were linked to mutations in CCM2, and 8% to 40% were linked to mutations in CCM3, depending on the series.13,15 The prevalence of symptomatic disease among gene carriers for kindreds linked to CCM1, CCM2, and CCM3 was 88%, 100%, and 63%, respectively.13 A specific founder mutation in CCM1 is thought to be responsible for virtually all cases of familial CCMs in Hispanic American individuals16 and up to 50% of this patient population are thought to have the familial form of the condition.5 As more is learned about the role of CCM gene mutations in the pathogenesis of CCMs, understanding how different mutations with different degrees of prevalence affect different patient populations will be important to help guide testing and perhaps treatment in the future.

Extracerebral manifestations of familial CCMs include retinal and cutaneous involvement. The incidence of retinal cavernomas has been estimated at 5% in familial CCM patients.17 The most commonly reported cutaneous finding (with an incidence of 3% to 5% reported in large case series) is hyperkeratotic cutaneous capillary-venous malformations (HCCVMs), which are composed of dilated capillaries and blood-filled, venouslike channels extending into the dermis and hypodermis with an overlying hyperkeratotic epidermis.7,18-20 Although the prevalence for CCM1-associated CCMs is reported to be higher than that for the HCCVMs in families affected by both cerebral and cutaneous lesions, all patients manifesting HCCVMs also have CCMs.18-20 Perhaps the cutaneous lesions may serve as markers of neurologic involvement in affected families. Other reports have shown an association between CCMs and cutaneous cavernous hemangiomas,21 capillary malformations,20 venous malformations,20,22 and cherry angiomas,21,23 although the relevance of cherry angiomas is unclear given their high prevalence in the general population.

There are few reports of patients with CCMs having angiokeratomas, including a 77-year-old Hispanic man with a solitary angiokeratoma, cutaneous venous malformations, multiple CCMs, and demonstration of the 2105C→T CCM1 founder mutation, which is commonly found in Hispanic patients24; a Chinese man with a CCM1 mutation and purple-black, raised, angiomalike skin lesions (similar to those seen in our patient) that which were not biopsied25; and a patient with multiple eruptive angiokeratomas who was found to have numerous CCMs before the availability of genetic testing.26 In our patient, the presentation of eruptive angiokeratomas prompted consideration of genetic testing and subsequent confirmation of a CCM1 mutation. Knowledge of the association between familial CCMs and cutaneous vascular lesions may be used to identify patients with clinically silent, undetected CCMs who may be at risk of developing future neurologic disorders or who may benefit from appropriate genetic counseling.

Conclusion

Familial CCMs are associated with extracerebral manifestations that include retinal cavernomas along with a variety of cutaneous manifestations. We present a case of a patient with adult-onset seizures, eruptive angiokeratomas, and cutaneous hemangiomas in the setting of numerous CCMs with confirmation of CCM1 mutation on genetic testing. We hope to raise awareness of the cutaneous findings associated with CCMs and the availability of genetic testing for CCM gene mutations so that patients with multiple cutaneous vascular lesions, including eruptive angiokeratomas, can be screened and tested for genetic mutations and neurologic involvement when appropriate.

1. Cavé-Riant F, Denier C, Labauge P, et al. Spectrum and expression analysis of KRIT1 mutations in 121 consecutive and unrelated patients with cerebral cavernous malformations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2002;10:733-740.

2. Simard JM, Garcia-Bengochea F, Ballinger WE Jr, et al. Cavernous angioma: a review of 126 collected and 12 new clinical cases. Neurosurgery. 1986;18:162-172.

3. Del Curling O Jr, Kelly DL Jr, Elster AD, et al. An analysis of the natural history of cavernous angiomas. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:702-708.

4. Otten P, Pizzolato GP, Rilliet B, et al. 131 cases of cavernous angioma (cavernomas) of the cns, discovered by retrospective analysis of 24,535 autopsies [article in French]. Neurochirurgie. 1989;35:82-83, 128-131.

5. Rigamonti D, Hadley MN, Drayer BP, et al. Cerebral cavernous malformations. incidence and familial occurrence. N Eng J Med. 1988;319:343-347.

6. Labauge P, Laberge S, Brunereau L, et al. Hereditary cerebral cavernous angiomas: clinical and genetic features in 57 French families. Société Française de Neurochirurgie. Lancet. 1998;352:1892-1897.

7. Denier C, Labauge P, Brunereau L, et al. Clinical features of cerebral cavernous malformations patients with KRIT1 mutations. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:213-220.

8. Moriarity JL, Wetzel M, Clatterbuck RE, et al. The natural history of cavernous malformations: a prospective study of 68 patients. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:1166-1171.

9. Robinson JR, Awad IA, Little JR. Natural history of the cavernous angioma. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:709-714.

10. Zabramski JM, Wascher TM, Spetzler RF, et al. The natural history of familial cavernous malformations: results of an ongoing study. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:422-432.

11. Cavalcanti DD, Kalani MY, Martirosyan NL, et al. Cerebral cavernous malformations: from genes to proteins to disease. J Neurosurg. 2012;116:122-132.

12. Sahoo T, Johnson EW, Thomas JW, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding KRIT1, a KREV-1/rap1a binding protein, cause cerebral cavernous malformations (CCM1). Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:2325-2333.

13. Craig HD, Gunel M, Cepeda O, et al. Multilocus linkage identifies two new loci for a mendelian form of stroke, cerebral cavernous malformation, at 7p15-13 and 3q25.2-27. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1851-1858.

14. Bergametti F, Denier C, Labauge P, et al; Société Française de Neurochirurgie. Mutations within the programmed cell death 10 gene cause cerebral cavernous malformations. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:42-51.

15. Denier C, Labauge P, Bergametti F, et al; Brain Vascular Malformation Consortium (BVMC) Study. Genotype-phenotype correlations in cerebral cavernous malformations patients. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:550-556.

16. Gunel M, Awad IA, Finberg K, et al. A founder mutation as a cause of cerebral cavernous malformation in Hispanic Americans. N Eng J Med. 1996;334:946-951.

17. Labauge P, Krivosic V, Denier C, et al. Frequency of retinal cavernomas in 60 patients with familial cerebral cavernomas: a clinical and genetic study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:885-886.

18. Eerola I, Plate KH, Spiegel R, et al. KRIT1 is mutated in hyperkeratotic cutaneous capillary-venous malformation associated with cerebral capillary malformation. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1351-1355.

19. Labauge P, Enjolras O, Bonerandi JJ, et al. An association between autosomal dominant cerebral cavernomas and a distinctive hyperkeratotic cutaneous vascular malformation in 4 families. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:250-254.

20. Sirvente J, Enjolras O, Wassef M, et al. Frequency and phenotypes of cutaneous vascular malformations in a consecutive series of 417 patients with familial cerebral cavernous malformations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1066-1072.

21. Filling-Katz MR, Levin SW, Patronas NJ, et al. Terminal transverse limb defects associated with familial cavernous angiomatosis. Am J Med Genet. 1992;42:346-351.

22. Toll A, Parera E, Giménez-Arnau AM, et al. Cutaneous venous malformations in familial cerebral cavernomatosis caused by KRIT1 gene mutations. Dermatology. 2009;218:307-313.

23. Clatterbuck RE, Rigamonti D. Cherry angiomas associated with familial cerebral cavernous malformations: case illustration. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:964.

24. Zlotoff BJ, Bang RH, Padilla RS, et al. Cutaneous angiokeratoma and venous malformations in a Hispanic-American patient with cerebral cavernous malformations. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:210-212.

25. Chen DH, Lipe HP, Qin Z, et al. Cerebral cavernous malformation: novel mutation in a Chinese family and evidence for heterogeneity. J Neurol Sci. 2002;196:91-96.

26. Ostlere L, Hart Y, Misch KJ. Cutaneous and cerebral haemangiomas associated with eruptive angiokeratomas. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:98-101.

Case Report

A 66-year-old non-Hispanic white man with a history of adult-onset seizures, renal cell carcinoma, and nephrolithiasis presented to the dermatology clinic with numerous dark red, dry, scaling lesions on the lower legs, abdomen, back, thighs, and scrotum that bled easily. The lesions had developed 2 to 4 years prior to presentation. The patient also noted several dark blue lesions on the bilateral arms that had been present for several years.

Physical examination revealed multiple black, keratotic papules on the bilateral lower legs (Figure 1), with similar lesions on the lower abdomen and lower back. Numerous dark red, scaling papules were present on the thighs and scrotum, and firm, 1- to 3-cm, dark blue nodules were noted on the bilateral arms (Figure 2) and right side of the forehead. Biopsy of papules from the lower right leg and back demonstrated angiokeratomas on pathologic review (Figure 3). Four separate biopsies taken from the left forearm demonstrated lobular and cavernous hemangiomas (Figure 4).

The patient’s medical history was remarkable for neurologic symptoms including adult-onset seizures at the age of 42 years. Recent magnetic resonance imaging of the head showed multiple areas of heterogeneous signal intensity with T2 hypointense rims consistent with cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs) involving both cerebral hemispheres, the posterior cranial fossa, and the brainstem (Figure 5). Of note, the patient’s mother had been diagnosed with epilepsy in her 40s, but no other family history of a clinically or radiographically diagnosed neurologic disorder was reported.

This presentation of numerous CCMs and cutaneous vascular lesions prompted genetic testing for mutations in the 3 CCM genes. Bidirectional sequencing from a blood specimen confirmed a 1267C→T substitution resulting in an Arg423X nonsense mutation in the KRIT1, ankyrin repeat containing gene (also known as CCM1) on chromosome 7, which is a published mutation.1 No treatment of the cutaneous lesions was administered. The patient continued to be treated by a neurologist for the seizure disorder after genetic testing and counseling was complete.

Comment

Cerebral cavernous malformations represent collections of dilated, capillarylike vessels without intervening brain parenchyma,2 which can occur as a sporadic or autosomal-dominant condition with variable prevalence. Imaging and autopsy studies suggest CCMs may be present in 0.5% of the general population, with the incidence of clinically symptomatic disease being much lower.3,4 While sporadic cases are usually associated with the presence of a single CCM, hereditary cases generally display multiple CCMs5-7; studies indicate that most patients who present with symptomatic CCMs are in the second to fifth decades of life.3,8-10 The most common clinical manifestations of CCMs are headaches, seizures, and focal neurologic deficits due to cerebral hemorrhages.11

Three autosomal-dominant forms of familial CCMs are associated with several different heterozygous mutations in the CCM1 gene, which encodes Krev interaction trapped protein 1; the cerebral cavernous malformation 2 gene (CCM2), which encodes the protein malcavernin; and the programmed cell death 10 gene (PDCD10)(also known as CCM3), which encodes the PDCD10 protein.12-14 Although the precise pathophysiologic mechanisms linking these mutations with the resultant clinical phenotypes have yet to be fully elucidated, these genes are thought to play roles in angiogenesis as well as vascular maintenance and remodeling.11 Among non-Hispanic white kindreds with familial CCMs, 40% to 72% of kindreds were linked to mutations in CCM1, 20% were linked to mutations in CCM2, and 8% to 40% were linked to mutations in CCM3, depending on the series.13,15 The prevalence of symptomatic disease among gene carriers for kindreds linked to CCM1, CCM2, and CCM3 was 88%, 100%, and 63%, respectively.13 A specific founder mutation in CCM1 is thought to be responsible for virtually all cases of familial CCMs in Hispanic American individuals16 and up to 50% of this patient population are thought to have the familial form of the condition.5 As more is learned about the role of CCM gene mutations in the pathogenesis of CCMs, understanding how different mutations with different degrees of prevalence affect different patient populations will be important to help guide testing and perhaps treatment in the future.

Extracerebral manifestations of familial CCMs include retinal and cutaneous involvement. The incidence of retinal cavernomas has been estimated at 5% in familial CCM patients.17 The most commonly reported cutaneous finding (with an incidence of 3% to 5% reported in large case series) is hyperkeratotic cutaneous capillary-venous malformations (HCCVMs), which are composed of dilated capillaries and blood-filled, venouslike channels extending into the dermis and hypodermis with an overlying hyperkeratotic epidermis.7,18-20 Although the prevalence for CCM1-associated CCMs is reported to be higher than that for the HCCVMs in families affected by both cerebral and cutaneous lesions, all patients manifesting HCCVMs also have CCMs.18-20 Perhaps the cutaneous lesions may serve as markers of neurologic involvement in affected families. Other reports have shown an association between CCMs and cutaneous cavernous hemangiomas,21 capillary malformations,20 venous malformations,20,22 and cherry angiomas,21,23 although the relevance of cherry angiomas is unclear given their high prevalence in the general population.

There are few reports of patients with CCMs having angiokeratomas, including a 77-year-old Hispanic man with a solitary angiokeratoma, cutaneous venous malformations, multiple CCMs, and demonstration of the 2105C→T CCM1 founder mutation, which is commonly found in Hispanic patients24; a Chinese man with a CCM1 mutation and purple-black, raised, angiomalike skin lesions (similar to those seen in our patient) that which were not biopsied25; and a patient with multiple eruptive angiokeratomas who was found to have numerous CCMs before the availability of genetic testing.26 In our patient, the presentation of eruptive angiokeratomas prompted consideration of genetic testing and subsequent confirmation of a CCM1 mutation. Knowledge of the association between familial CCMs and cutaneous vascular lesions may be used to identify patients with clinically silent, undetected CCMs who may be at risk of developing future neurologic disorders or who may benefit from appropriate genetic counseling.

Conclusion

Familial CCMs are associated with extracerebral manifestations that include retinal cavernomas along with a variety of cutaneous manifestations. We present a case of a patient with adult-onset seizures, eruptive angiokeratomas, and cutaneous hemangiomas in the setting of numerous CCMs with confirmation of CCM1 mutation on genetic testing. We hope to raise awareness of the cutaneous findings associated with CCMs and the availability of genetic testing for CCM gene mutations so that patients with multiple cutaneous vascular lesions, including eruptive angiokeratomas, can be screened and tested for genetic mutations and neurologic involvement when appropriate.

Case Report

A 66-year-old non-Hispanic white man with a history of adult-onset seizures, renal cell carcinoma, and nephrolithiasis presented to the dermatology clinic with numerous dark red, dry, scaling lesions on the lower legs, abdomen, back, thighs, and scrotum that bled easily. The lesions had developed 2 to 4 years prior to presentation. The patient also noted several dark blue lesions on the bilateral arms that had been present for several years.

Physical examination revealed multiple black, keratotic papules on the bilateral lower legs (Figure 1), with similar lesions on the lower abdomen and lower back. Numerous dark red, scaling papules were present on the thighs and scrotum, and firm, 1- to 3-cm, dark blue nodules were noted on the bilateral arms (Figure 2) and right side of the forehead. Biopsy of papules from the lower right leg and back demonstrated angiokeratomas on pathologic review (Figure 3). Four separate biopsies taken from the left forearm demonstrated lobular and cavernous hemangiomas (Figure 4).

The patient’s medical history was remarkable for neurologic symptoms including adult-onset seizures at the age of 42 years. Recent magnetic resonance imaging of the head showed multiple areas of heterogeneous signal intensity with T2 hypointense rims consistent with cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs) involving both cerebral hemispheres, the posterior cranial fossa, and the brainstem (Figure 5). Of note, the patient’s mother had been diagnosed with epilepsy in her 40s, but no other family history of a clinically or radiographically diagnosed neurologic disorder was reported.

This presentation of numerous CCMs and cutaneous vascular lesions prompted genetic testing for mutations in the 3 CCM genes. Bidirectional sequencing from a blood specimen confirmed a 1267C→T substitution resulting in an Arg423X nonsense mutation in the KRIT1, ankyrin repeat containing gene (also known as CCM1) on chromosome 7, which is a published mutation.1 No treatment of the cutaneous lesions was administered. The patient continued to be treated by a neurologist for the seizure disorder after genetic testing and counseling was complete.

Comment

Cerebral cavernous malformations represent collections of dilated, capillarylike vessels without intervening brain parenchyma,2 which can occur as a sporadic or autosomal-dominant condition with variable prevalence. Imaging and autopsy studies suggest CCMs may be present in 0.5% of the general population, with the incidence of clinically symptomatic disease being much lower.3,4 While sporadic cases are usually associated with the presence of a single CCM, hereditary cases generally display multiple CCMs5-7; studies indicate that most patients who present with symptomatic CCMs are in the second to fifth decades of life.3,8-10 The most common clinical manifestations of CCMs are headaches, seizures, and focal neurologic deficits due to cerebral hemorrhages.11

Three autosomal-dominant forms of familial CCMs are associated with several different heterozygous mutations in the CCM1 gene, which encodes Krev interaction trapped protein 1; the cerebral cavernous malformation 2 gene (CCM2), which encodes the protein malcavernin; and the programmed cell death 10 gene (PDCD10)(also known as CCM3), which encodes the PDCD10 protein.12-14 Although the precise pathophysiologic mechanisms linking these mutations with the resultant clinical phenotypes have yet to be fully elucidated, these genes are thought to play roles in angiogenesis as well as vascular maintenance and remodeling.11 Among non-Hispanic white kindreds with familial CCMs, 40% to 72% of kindreds were linked to mutations in CCM1, 20% were linked to mutations in CCM2, and 8% to 40% were linked to mutations in CCM3, depending on the series.13,15 The prevalence of symptomatic disease among gene carriers for kindreds linked to CCM1, CCM2, and CCM3 was 88%, 100%, and 63%, respectively.13 A specific founder mutation in CCM1 is thought to be responsible for virtually all cases of familial CCMs in Hispanic American individuals16 and up to 50% of this patient population are thought to have the familial form of the condition.5 As more is learned about the role of CCM gene mutations in the pathogenesis of CCMs, understanding how different mutations with different degrees of prevalence affect different patient populations will be important to help guide testing and perhaps treatment in the future.

Extracerebral manifestations of familial CCMs include retinal and cutaneous involvement. The incidence of retinal cavernomas has been estimated at 5% in familial CCM patients.17 The most commonly reported cutaneous finding (with an incidence of 3% to 5% reported in large case series) is hyperkeratotic cutaneous capillary-venous malformations (HCCVMs), which are composed of dilated capillaries and blood-filled, venouslike channels extending into the dermis and hypodermis with an overlying hyperkeratotic epidermis.7,18-20 Although the prevalence for CCM1-associated CCMs is reported to be higher than that for the HCCVMs in families affected by both cerebral and cutaneous lesions, all patients manifesting HCCVMs also have CCMs.18-20 Perhaps the cutaneous lesions may serve as markers of neurologic involvement in affected families. Other reports have shown an association between CCMs and cutaneous cavernous hemangiomas,21 capillary malformations,20 venous malformations,20,22 and cherry angiomas,21,23 although the relevance of cherry angiomas is unclear given their high prevalence in the general population.

There are few reports of patients with CCMs having angiokeratomas, including a 77-year-old Hispanic man with a solitary angiokeratoma, cutaneous venous malformations, multiple CCMs, and demonstration of the 2105C→T CCM1 founder mutation, which is commonly found in Hispanic patients24; a Chinese man with a CCM1 mutation and purple-black, raised, angiomalike skin lesions (similar to those seen in our patient) that which were not biopsied25; and a patient with multiple eruptive angiokeratomas who was found to have numerous CCMs before the availability of genetic testing.26 In our patient, the presentation of eruptive angiokeratomas prompted consideration of genetic testing and subsequent confirmation of a CCM1 mutation. Knowledge of the association between familial CCMs and cutaneous vascular lesions may be used to identify patients with clinically silent, undetected CCMs who may be at risk of developing future neurologic disorders or who may benefit from appropriate genetic counseling.

Conclusion

Familial CCMs are associated with extracerebral manifestations that include retinal cavernomas along with a variety of cutaneous manifestations. We present a case of a patient with adult-onset seizures, eruptive angiokeratomas, and cutaneous hemangiomas in the setting of numerous CCMs with confirmation of CCM1 mutation on genetic testing. We hope to raise awareness of the cutaneous findings associated with CCMs and the availability of genetic testing for CCM gene mutations so that patients with multiple cutaneous vascular lesions, including eruptive angiokeratomas, can be screened and tested for genetic mutations and neurologic involvement when appropriate.

1. Cavé-Riant F, Denier C, Labauge P, et al. Spectrum and expression analysis of KRIT1 mutations in 121 consecutive and unrelated patients with cerebral cavernous malformations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2002;10:733-740.

2. Simard JM, Garcia-Bengochea F, Ballinger WE Jr, et al. Cavernous angioma: a review of 126 collected and 12 new clinical cases. Neurosurgery. 1986;18:162-172.

3. Del Curling O Jr, Kelly DL Jr, Elster AD, et al. An analysis of the natural history of cavernous angiomas. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:702-708.

4. Otten P, Pizzolato GP, Rilliet B, et al. 131 cases of cavernous angioma (cavernomas) of the cns, discovered by retrospective analysis of 24,535 autopsies [article in French]. Neurochirurgie. 1989;35:82-83, 128-131.

5. Rigamonti D, Hadley MN, Drayer BP, et al. Cerebral cavernous malformations. incidence and familial occurrence. N Eng J Med. 1988;319:343-347.

6. Labauge P, Laberge S, Brunereau L, et al. Hereditary cerebral cavernous angiomas: clinical and genetic features in 57 French families. Société Française de Neurochirurgie. Lancet. 1998;352:1892-1897.

7. Denier C, Labauge P, Brunereau L, et al. Clinical features of cerebral cavernous malformations patients with KRIT1 mutations. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:213-220.

8. Moriarity JL, Wetzel M, Clatterbuck RE, et al. The natural history of cavernous malformations: a prospective study of 68 patients. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:1166-1171.

9. Robinson JR, Awad IA, Little JR. Natural history of the cavernous angioma. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:709-714.

10. Zabramski JM, Wascher TM, Spetzler RF, et al. The natural history of familial cavernous malformations: results of an ongoing study. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:422-432.

11. Cavalcanti DD, Kalani MY, Martirosyan NL, et al. Cerebral cavernous malformations: from genes to proteins to disease. J Neurosurg. 2012;116:122-132.

12. Sahoo T, Johnson EW, Thomas JW, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding KRIT1, a KREV-1/rap1a binding protein, cause cerebral cavernous malformations (CCM1). Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:2325-2333.

13. Craig HD, Gunel M, Cepeda O, et al. Multilocus linkage identifies two new loci for a mendelian form of stroke, cerebral cavernous malformation, at 7p15-13 and 3q25.2-27. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1851-1858.

14. Bergametti F, Denier C, Labauge P, et al; Société Française de Neurochirurgie. Mutations within the programmed cell death 10 gene cause cerebral cavernous malformations. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:42-51.

15. Denier C, Labauge P, Bergametti F, et al; Brain Vascular Malformation Consortium (BVMC) Study. Genotype-phenotype correlations in cerebral cavernous malformations patients. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:550-556.

16. Gunel M, Awad IA, Finberg K, et al. A founder mutation as a cause of cerebral cavernous malformation in Hispanic Americans. N Eng J Med. 1996;334:946-951.

17. Labauge P, Krivosic V, Denier C, et al. Frequency of retinal cavernomas in 60 patients with familial cerebral cavernomas: a clinical and genetic study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:885-886.

18. Eerola I, Plate KH, Spiegel R, et al. KRIT1 is mutated in hyperkeratotic cutaneous capillary-venous malformation associated with cerebral capillary malformation. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1351-1355.

19. Labauge P, Enjolras O, Bonerandi JJ, et al. An association between autosomal dominant cerebral cavernomas and a distinctive hyperkeratotic cutaneous vascular malformation in 4 families. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:250-254.

20. Sirvente J, Enjolras O, Wassef M, et al. Frequency and phenotypes of cutaneous vascular malformations in a consecutive series of 417 patients with familial cerebral cavernous malformations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1066-1072.

21. Filling-Katz MR, Levin SW, Patronas NJ, et al. Terminal transverse limb defects associated with familial cavernous angiomatosis. Am J Med Genet. 1992;42:346-351.

22. Toll A, Parera E, Giménez-Arnau AM, et al. Cutaneous venous malformations in familial cerebral cavernomatosis caused by KRIT1 gene mutations. Dermatology. 2009;218:307-313.

23. Clatterbuck RE, Rigamonti D. Cherry angiomas associated with familial cerebral cavernous malformations: case illustration. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:964.

24. Zlotoff BJ, Bang RH, Padilla RS, et al. Cutaneous angiokeratoma and venous malformations in a Hispanic-American patient with cerebral cavernous malformations. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:210-212.

25. Chen DH, Lipe HP, Qin Z, et al. Cerebral cavernous malformation: novel mutation in a Chinese family and evidence for heterogeneity. J Neurol Sci. 2002;196:91-96.

26. Ostlere L, Hart Y, Misch KJ. Cutaneous and cerebral haemangiomas associated with eruptive angiokeratomas. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:98-101.

1. Cavé-Riant F, Denier C, Labauge P, et al. Spectrum and expression analysis of KRIT1 mutations in 121 consecutive and unrelated patients with cerebral cavernous malformations. Eur J Hum Genet. 2002;10:733-740.

2. Simard JM, Garcia-Bengochea F, Ballinger WE Jr, et al. Cavernous angioma: a review of 126 collected and 12 new clinical cases. Neurosurgery. 1986;18:162-172.

3. Del Curling O Jr, Kelly DL Jr, Elster AD, et al. An analysis of the natural history of cavernous angiomas. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:702-708.

4. Otten P, Pizzolato GP, Rilliet B, et al. 131 cases of cavernous angioma (cavernomas) of the cns, discovered by retrospective analysis of 24,535 autopsies [article in French]. Neurochirurgie. 1989;35:82-83, 128-131.

5. Rigamonti D, Hadley MN, Drayer BP, et al. Cerebral cavernous malformations. incidence and familial occurrence. N Eng J Med. 1988;319:343-347.

6. Labauge P, Laberge S, Brunereau L, et al. Hereditary cerebral cavernous angiomas: clinical and genetic features in 57 French families. Société Française de Neurochirurgie. Lancet. 1998;352:1892-1897.

7. Denier C, Labauge P, Brunereau L, et al. Clinical features of cerebral cavernous malformations patients with KRIT1 mutations. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:213-220.

8. Moriarity JL, Wetzel M, Clatterbuck RE, et al. The natural history of cavernous malformations: a prospective study of 68 patients. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:1166-1171.

9. Robinson JR, Awad IA, Little JR. Natural history of the cavernous angioma. J Neurosurg. 1991;75:709-714.

10. Zabramski JM, Wascher TM, Spetzler RF, et al. The natural history of familial cavernous malformations: results of an ongoing study. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:422-432.

11. Cavalcanti DD, Kalani MY, Martirosyan NL, et al. Cerebral cavernous malformations: from genes to proteins to disease. J Neurosurg. 2012;116:122-132.

12. Sahoo T, Johnson EW, Thomas JW, et al. Mutations in the gene encoding KRIT1, a KREV-1/rap1a binding protein, cause cerebral cavernous malformations (CCM1). Hum Mol Genet. 1999;8:2325-2333.

13. Craig HD, Gunel M, Cepeda O, et al. Multilocus linkage identifies two new loci for a mendelian form of stroke, cerebral cavernous malformation, at 7p15-13 and 3q25.2-27. Hum Mol Genet. 1998;7:1851-1858.

14. Bergametti F, Denier C, Labauge P, et al; Société Française de Neurochirurgie. Mutations within the programmed cell death 10 gene cause cerebral cavernous malformations. Am J Hum Genet. 2005;76:42-51.

15. Denier C, Labauge P, Bergametti F, et al; Brain Vascular Malformation Consortium (BVMC) Study. Genotype-phenotype correlations in cerebral cavernous malformations patients. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:550-556.

16. Gunel M, Awad IA, Finberg K, et al. A founder mutation as a cause of cerebral cavernous malformation in Hispanic Americans. N Eng J Med. 1996;334:946-951.

17. Labauge P, Krivosic V, Denier C, et al. Frequency of retinal cavernomas in 60 patients with familial cerebral cavernomas: a clinical and genetic study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:885-886.

18. Eerola I, Plate KH, Spiegel R, et al. KRIT1 is mutated in hyperkeratotic cutaneous capillary-venous malformation associated with cerebral capillary malformation. Hum Mol Genet. 2000;9:1351-1355.

19. Labauge P, Enjolras O, Bonerandi JJ, et al. An association between autosomal dominant cerebral cavernomas and a distinctive hyperkeratotic cutaneous vascular malformation in 4 families. Ann Neurol. 1999;45:250-254.

20. Sirvente J, Enjolras O, Wassef M, et al. Frequency and phenotypes of cutaneous vascular malformations in a consecutive series of 417 patients with familial cerebral cavernous malformations. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2009;23:1066-1072.

21. Filling-Katz MR, Levin SW, Patronas NJ, et al. Terminal transverse limb defects associated with familial cavernous angiomatosis. Am J Med Genet. 1992;42:346-351.

22. Toll A, Parera E, Giménez-Arnau AM, et al. Cutaneous venous malformations in familial cerebral cavernomatosis caused by KRIT1 gene mutations. Dermatology. 2009;218:307-313.

23. Clatterbuck RE, Rigamonti D. Cherry angiomas associated with familial cerebral cavernous malformations: case illustration. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:964.

24. Zlotoff BJ, Bang RH, Padilla RS, et al. Cutaneous angiokeratoma and venous malformations in a Hispanic-American patient with cerebral cavernous malformations. Br J Dermatol. 2007;157:210-212.

25. Chen DH, Lipe HP, Qin Z, et al. Cerebral cavernous malformation: novel mutation in a Chinese family and evidence for heterogeneity. J Neurol Sci. 2002;196:91-96.

26. Ostlere L, Hart Y, Misch KJ. Cutaneous and cerebral haemangiomas associated with eruptive angiokeratomas. Br J Dermatol. 1996;135:98-101.

Practice Points

- Familial cerebral cavernous malformations (CCMs) are associated with extra-cerebral manifestations that include retinal cavernomas as well as a variety of cutaneous manifestations.

- Our patient presented with adult-onset eruptive angiokeratomas, cutaneous hemangiomas, and adult-onset seizures in the setting of numerous CCMs with confirmation of CCM1 mutation.

- Dermatologists should be aware of the availability of genetic testing for CCM gene mutations and neurologic screening in patients presenting with multiple cutaneous vascular lesions, including eruptive angiokeratomas.