User login

Deaths of children who are killed by their parents often make the news. Cases of maternal infanticide may be particularly shocking, since women are expected to be selfless nurturers. Yet when a child is murdered, the most common perpetrator is their parent, and mothers and fathers kill at similar rates.1

As psychiatrists, we may see these cases in the news and worry about the risks of our own patients killing their children. In approximately 500 cases annually, an American parent is arrested for the homicide of their child.2 This is not even the entire story, since a large percentage of such cases end in suicide—and no arrest. This article reviews the reasons parents kill their children, and considers common characteristics of these parents, dispelling some myths, before discussing the importance of prevention efforts.

Types of child murder by parents

Child murder by parents is termed filicide. Infanticide has various meanings but often refers to the murder of a child younger than age 1. Approximately 2 dozen nations (but not the United States) have Infanticide Acts that decrease the penalty for mothers who kill their young child.3 Neonaticide refers to murder of the infant at birth or in the first day of life.4

Epidemiology and common characteristics

Approximately 15%—or 1 in 7 murders with an arrest—is a filicide.2 The younger the child, the greater the risk, but older children are killed as well.2 Internationally, fathers and mothers are found to kill at similar rates. For other types of homicide, offenders are overwhelmingly male. This makes child murder by parents the singular type of murder in which women and men perpetrate in equal numbers. Fathers are more likely than mothers to also commit suicide after they kill their children.5 The “Cinderella effect” refers to the elevated risk of a stepchild being killed compared to the risk for a biological child.6

In the general international population, mothers who commit filicide tend to have multiple stressors and limited resources. They may be socially isolated and may be victims themselves as well as potentially experiencing substance abuse.1 Some mothers view the child they killed as abnormal.

Less research has been conducted about fathers who kill. Fathers are more likely to also commit partner homicide.5,7 They are more likely to complete filicide-suicide and use firearms or other violent means.5,7-9 Fathers may have a history of violence, substance abuse, and/or mental illness.7

Neonaticide

Mothers are the most common perpetrator of neonaticide.4 It is unusual for a father to be involved in a neonaticide, or for the father and mother to perpetrate the act together. Rates of neonaticide are considered underestimates because of the number of hidden pregnancies, hidden corpses, and the difficulty that forensic pathologists may have in determining whether a baby was born alive or dead.

Continue to: Perpetrators of neonaticide...

Perpetrators of neonaticide tend to be single, relatively young women acting alone. They often live with their parents and are fearful of the repercussions of being pregnant. Pregnancies are often hidden, with no prenatal care. This includes both denial and concealment of pregnancy.4 Perpetrators of neonaticide commonly lack a premorbid serious mental illness, though after the homicide they may develop anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or adjustment disorder.4 (Individuals who unwittingly find a murdered baby’s corpse may also be at risk of PTSD.)

Hidden pregnancies may be due to concealment or denial of pregnancy.10,11 Concealment of pregnancy involves a woman knowing she is pregnant, but purposely hiding from others. Concealment may occur after a period of denial of pregnancy. Denial of pregnancy has several subtypes: pervasive denial, affective denial, and psychotic denial. In cases of pervasive denial, the existence of the pregnancy and the pregnancy’s emotional significance is outside the woman’s awareness. Alternatively, in affective denial, she is intellectually aware that she is pregnant but makes little emotional or physical preparation. In the rarest form, psychotic denial, a woman with a psychotic disorder such as schizophrenia may intermittently deny her pregnancy. This may be correlated with a history of custody loss.10,11 Unlike denial of other medical conditions, in cases of denial of pregnancy, there will exist a very specific point in time (delivery) when the reality of the baby confronts the woman. Risks in cases of hidden pregnancies include those from lack of prenatal care and an assisted delivery as well as neonaticide. An FBI study12 of law enforcement files found most neonaticide offenders were single young women with no criminal or psychological history. A caveat is that in the rare cases in which a woman with psychotic illness commits neonaticide, she may have different characteristics from those generally reported.13

Motives

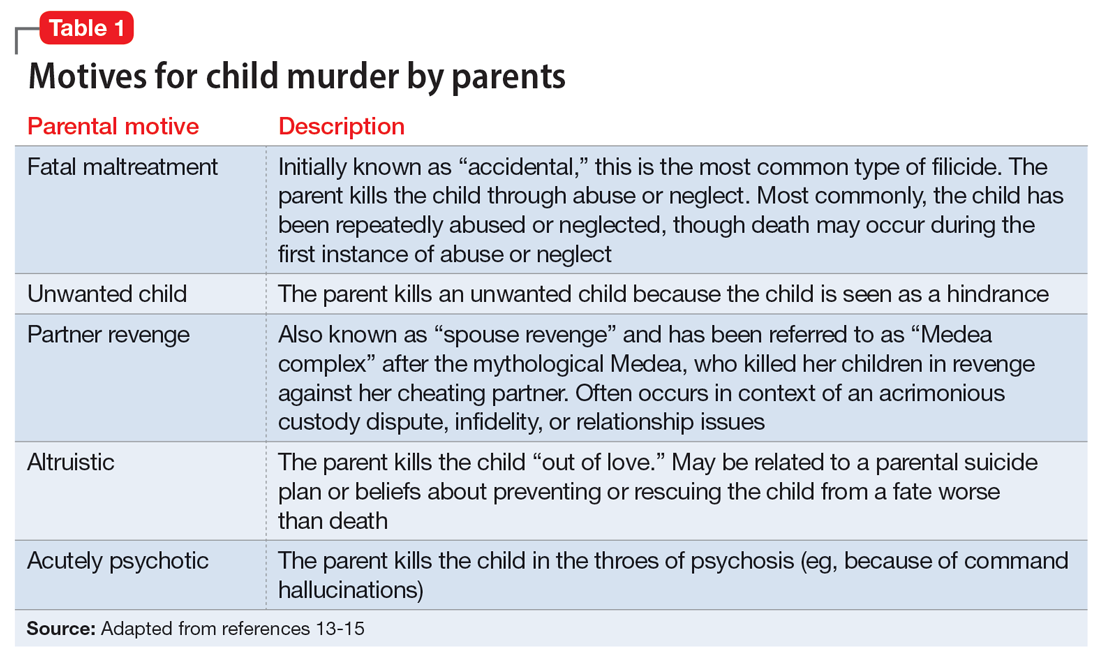

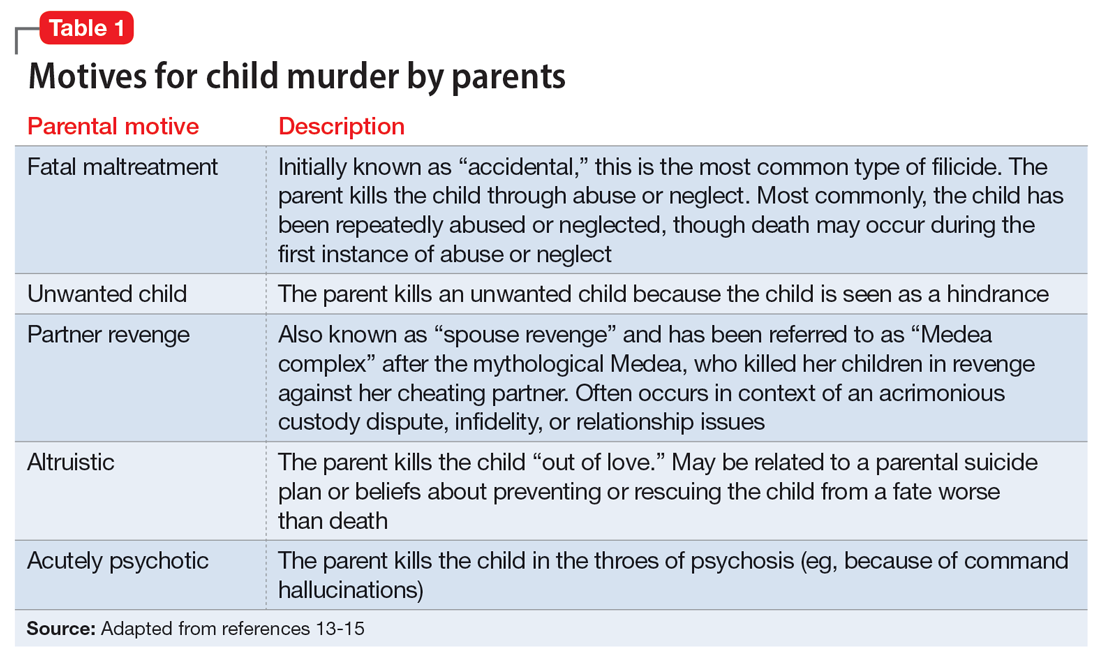

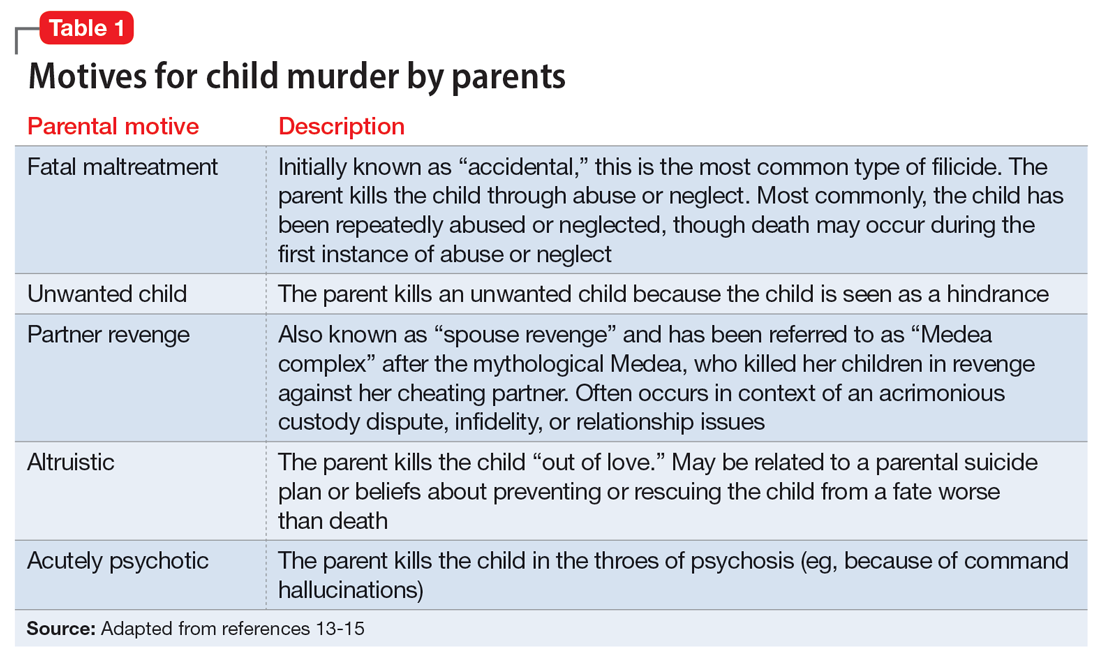

Fathers and mothers have a similar set of motives for killing their child (Table 113-15). Motives are critical to understand not only within forensics, but also for prevention. In performing assessments after a filicide, forensic psychiatrists must be mindful of gender bias.7,16 Resnick15 initially described 5 motives based on his 1969 review of the world literature. Our work5,17 has subsequently further explored these motives.

In child homicides from “fatal maltreatment,” the child has often been a chronic victim of abuse or neglect. National American data indicate that approximately 2 per 100,000 children are killed from child maltreatment annually. Of note in conceptualizing prevention, out of the same population of 100,000, there will be 471 referrals to Child Protective Services and 91 substantiated cases.18 However, only a minority of children who die from maltreatment had previous Child Protective Services involvement. While a child may be killed by fatal maltreatment at any age, one-half are younger than age 1, and three-quarters are younger than age 3.18 In rare cases, a parent who engages in medical child abuse (including factitious disorder imposed upon another) kills the child. Depending on the location and whether or not the death appeared to be intended, parents who kill because of fatal maltreatment might face charges of various levels of murder or manslaughter.

“Unwanted child” homicides occur when the parent has determined that they do not want to have the child, especially in comparison to another need or want. Unwanted child motive is the most common in neonaticide cases, occurring after a hidden pregnancy.4

Continue to: In "partner revenge" cases...

In “partner revenge” cases, parenting disputes, a custody battle, infidelity, or a difficult relationship breakup is often present. The parent wants to make the other parent suffer, and does so by killing their child. A parent may make statements such as “If I can’t have [the child], no one can,” and the child is used as a pawn.

In the final 2 motives—“altruistic” and “acutely psychotic”—mental illness is common. These are the populations we tend to find in samples of filicide-suicide cases where the parent has killed themselves and their child, and those found not guilty by reason of insanity.5,17 Altruistic filicide has been described as “murder out of love.” How can a parent kill their child out of love? Our research has shown several ways. First, the parent may be severely depressed and suicidal. They may be planning their own suicide, and as a parent who loves their child, they plan to take their child with them in death and not leave them alone in the “cruel world” that they themselves are departing. Or the parent may believe they are killing the child out of love to prevent or relieve the child’s suffering. The psychotic parent may believe that a terrible fate will befall their child, and they are killing them “gently.” For example, the parent may believe the child will be tortured or sex trafficked. Some parents may believe that their child has a devastating disease and think they would be better off dead. (Similar thinking of misguided altruism is seen in some cases of intimate partner homicide among older adults.19)

Alternatively, in rare cases of acutely psychotic filicide, parents with psychosis kill their child with no comprehensible motive. For example, they may be in a postictal state or may hear a command hallucination from God in the context of their psychosis.15

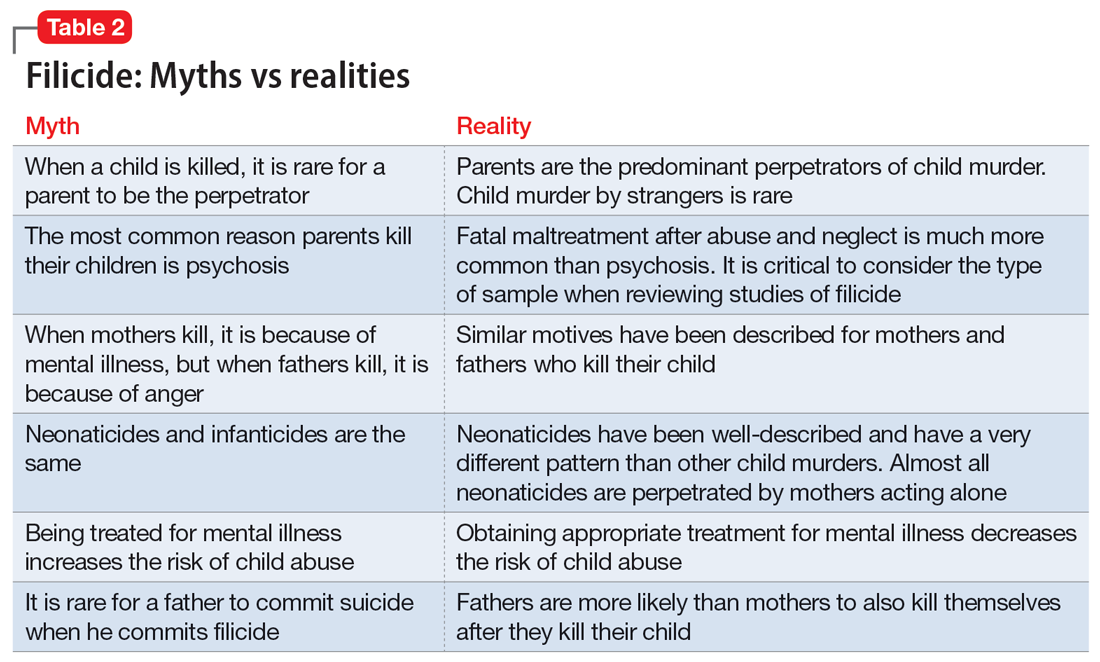

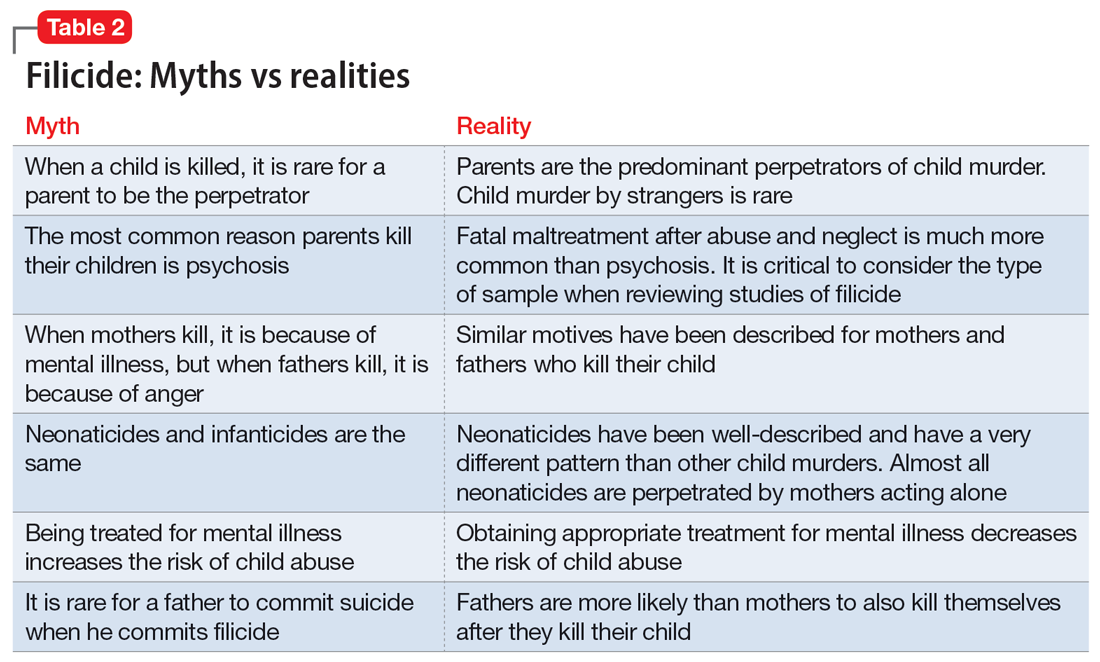

Myths vs realities of filicide

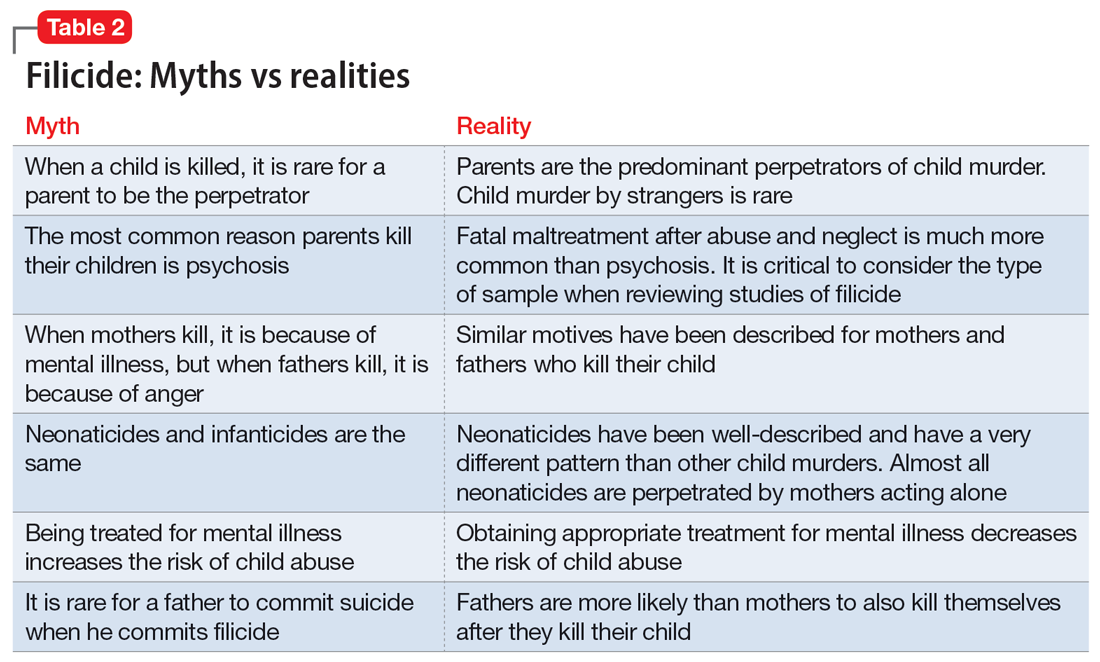

Common myths vs the realities of filicide are noted in Table 2. There are issues with believing these myths. For example, if we believe that most parents who kill their child have mental illness, this conflates mental illness and child homicide in our minds as well as the mind of the public. This can lead to further stigmatization of mental illness, and a lack of help-seeking behaviors because parents experiencing psychiatric symptoms may be afraid that if they report their symptoms, their child will be removed by Child Protective Services. However, treated mental illness decreases the risks of child abuse, similar to how treating mental illness decreases risks of other types of violence.20,21

Focusing on prevention

On a local level, we need to understand these tragedies to better understand prevention. To this end, across the United States, counties have Child Fatality Review teams.22 These teams are a partnership across sectors and disciplines, including professionals from health services, law enforcement, and social services—among others—working together to understand cases and consider preventive strategies and additional services needed within our communities.

Continue to: When conceptualizing prevention...

When conceptualizing prevention of child murder by parents, we can think of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention. This means we want to encourage healthy families and healthy relationships within the family, as well as screening for risk and targeting interventions for families that have experienced difficulties, as well as for parents who have mental illness or substance use disorders.

Understanding the motive behind an individual committing filicide is also critical so that we do not conflate filicide and mental illness. Conflating these concepts leads to increased stigmatization and less help-seeking behavior.

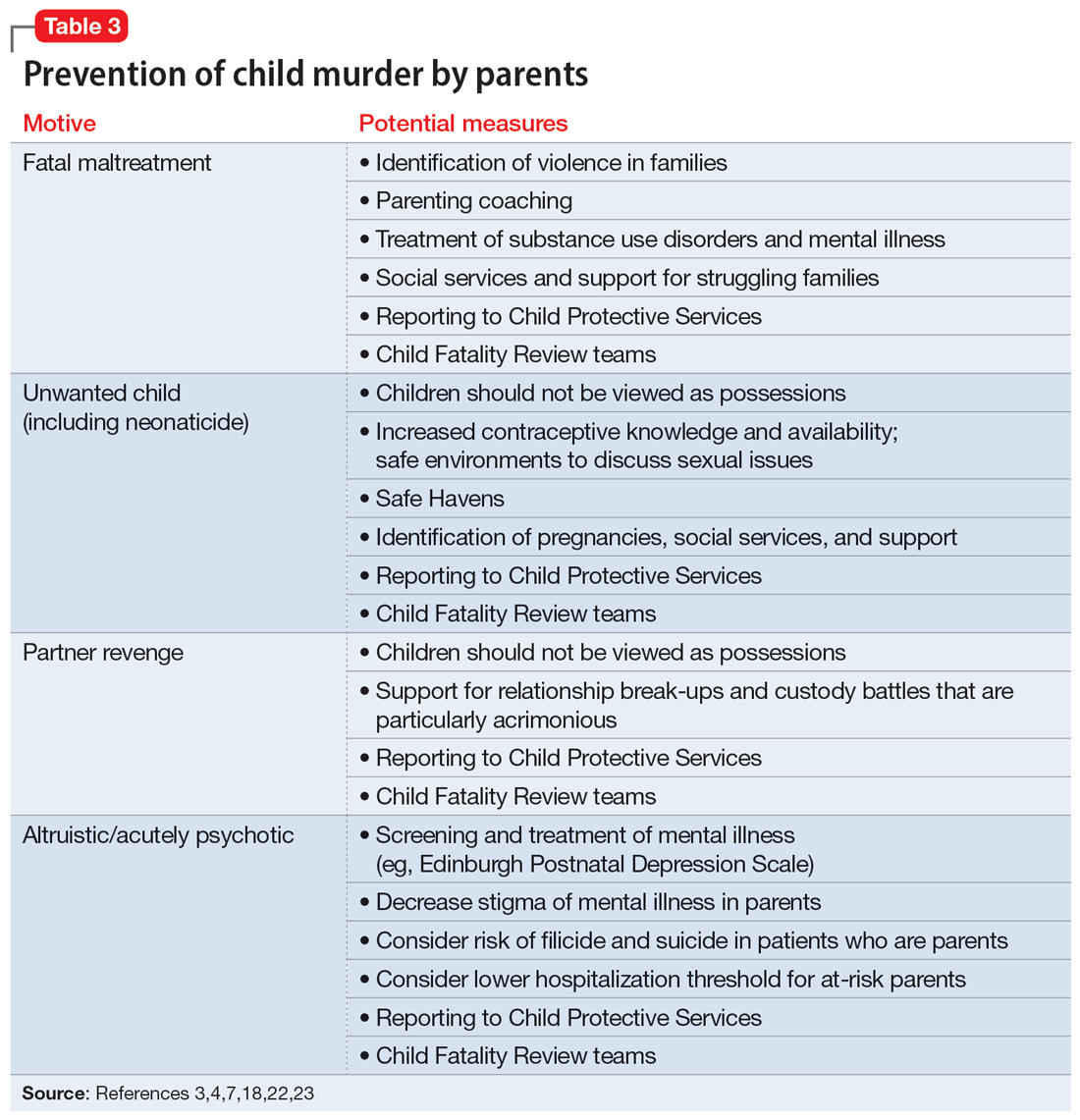

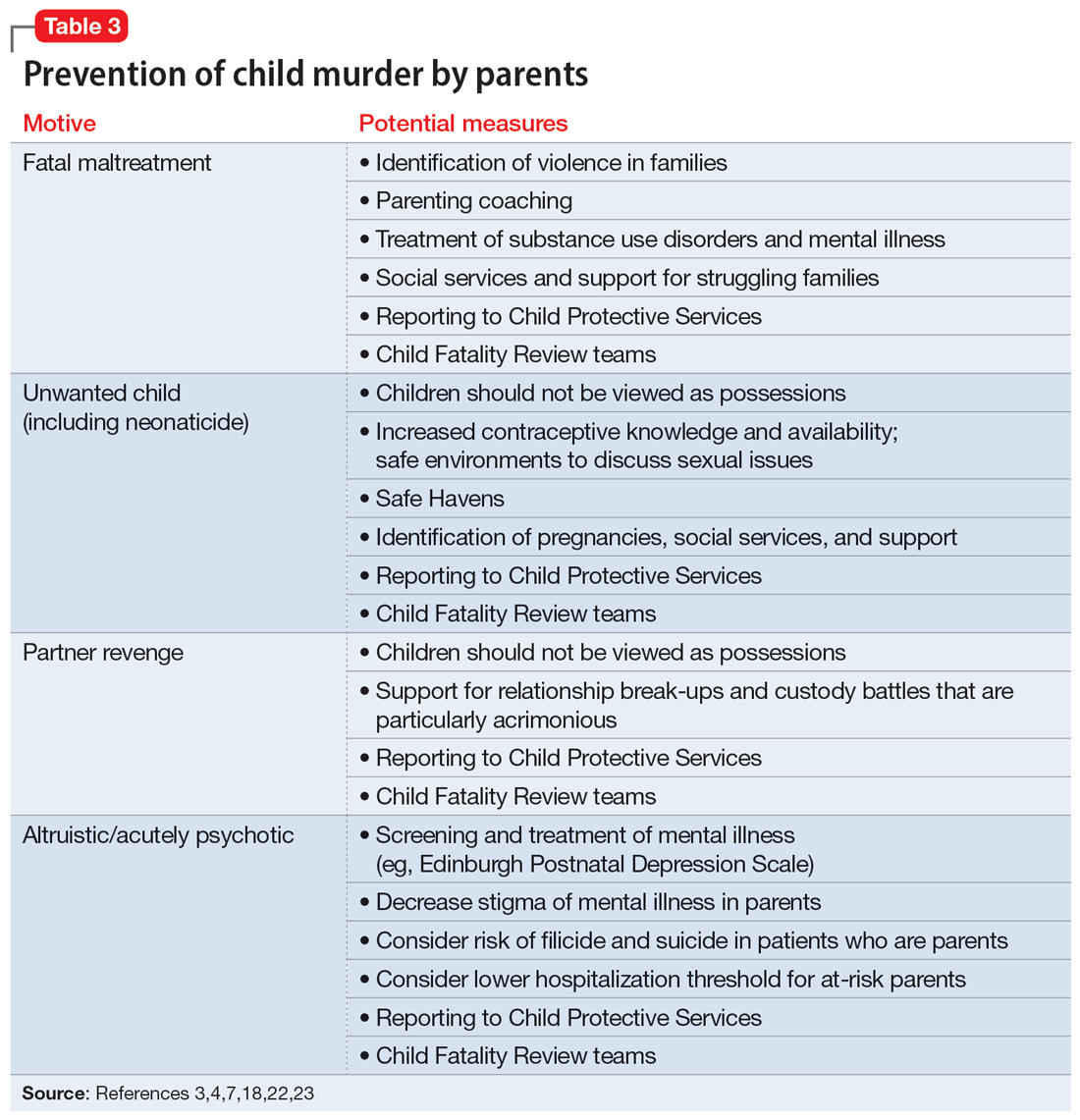

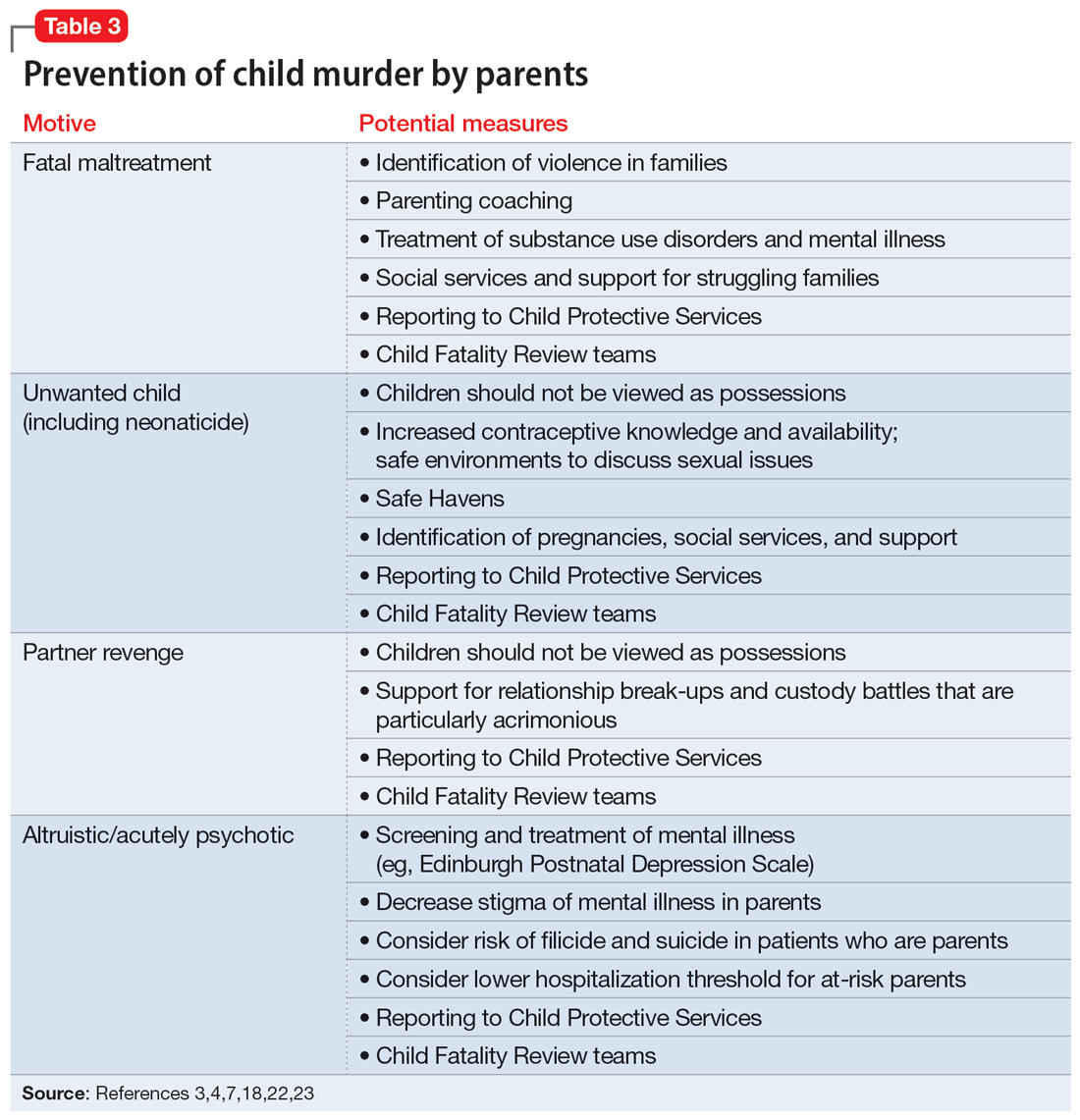

Table 33,4,7,18,22,23 describes the importance of understanding the motives for child murder by a parent in order to conceptualize appropriate prevention. Prevention efforts for 1 type of child murder will not necessarily help prevent murders that occur due to the other motives. Regarding prevention for fatal maltreatment cases, poor parenting skills, including inappropriate expressions of discipline, anger, and frustration, are common. In some cases, substance abuse is involved or the parent was acutely mentally unwell. Reporting to Child Protective Services can be helpful, but as previously noted, it is difficult to ascertain which cases will lead to a homicide. Recommendations from Child Fatality Review teams also are valuable.

Though many parents have frustrations with their children or thoughts of child harm, the act of filicide is rare, and individual cases may be difficult to predict. Regarding prediction, some mothers who committed filicide saw their psychiatrist within days to weeks before the murders.17 A small New Zealand study found that psychotic mothers reported no plans for killing their children in advance, whereas depressed mothers had contemplated the killing for days to weeks.24

Several studies have asked mothers about thoughts of harming their child. Among mothers with colicky infants, 70% reported “explicit aggressive thoughts and fantasies” while 26% had “infanticidal thoughts” during a colic episode.25 Another study26 found that among depressed mothers of infants and toddlers, 41% revealed thoughts of harming their child. Women with postpartum depression preferred not to share infanticidal thoughts with their doctor but were more likely to disclose that they were having suicidal thoughts in order to get needed help.27 Psychiatrists need to feel comfortable asking mothers about their coping skills, their suicidal thoughts, and their filicidal thoughts.14,23,28 Screening and treatment of mental illness is critical. Postpartum psychosis is well-known to pose an elevated risk of filicide and suicide.23 Obsessive-compulsive disorder may cause a parent to ruminate over ego-dystonic child harm but should be treated and the risk conceptualized very differently than in postpartum psychosis.23,29 Screening for postpartum depression and appropriate treatment of depression during pregnancy and the postpartum period decrease risk.30

Continue to: Regarding prevention of neonaticide...

Regarding prevention of neonaticide, Safe Haven laws, baby boxes, anonymous birth options, and increased contraceptive information and availability can help decrease the risk of this well-defined type of homicide.4 Safe Haven laws originated from Child Fatality Review teams.24 Though each state has its own variation, in general, parents can drop off an unharmed unwanted infant into Safe Havens in their state, which may include hospitals, police stations, or fire stations. In general, the mother remains anonymous and has immunity from prosecution for (safe) abandonment. There are drawbacks, such as lack of information regarding adoption and paternal rights. Safe Haven laws do not prevent all deaths and all unsafe abandonments. Baby boxes and baby hatches are used in various nations, including in Europe, and in some places have been used for centuries. In anonymous birth options, such as in France, a mother is not identified but is able to give birth at a hospital. This can decrease the risk from unattended delivery, but many women with denial of pregnancy report that they did not realize when they were about to give birth.4

Bottom Line

Knowledge about the intersection of mental illness and filicide can help in prevention. Parents who experience mental health concerns should be encouraged to obtain needed treatment, which aids prevention. However, many other factors elevate the risk of child murder by parents.

Related Resources

- National Center for Fatality Review and Prevention. https://ncfrp.org/

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/preventing/overview/federal-agencies/

1. Friedman SH, Horwitz SM, Resnick PJ. Child murder by mothers: a critical analysis of the current state of knowledge and a research agenda. Am J Psych. 2005;162(9):1578-1587.

2. Mariano TY, Chan HC, Myers WC. Toward a more holistic understanding of filicide: a multidisciplinary analysis of 32 years of US arrest data [published corrections appears in Forensic Sci Int. 2014;245:92-94]. Forensic Sci Int. 2014;236:46-53.

3. Hatters Friedman S, Resnick PJ. Child murder by mothers: patterns and prevention. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):137-141.

4. Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Neonaticide: phenomenology and considerations for prevention. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2009;32(1):43-47.

5. Hatters Friedman S, Hrouda DR, Holden CE, et al. Filicide-suicide: common factors in parents who kill their children and themselves. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2005;33(4):496-504.

6. Daly M, Wilson M. Is the “Cinderella effect” controversial? A case study of evolution-minded research and critiques thereof. In: Crawford C, Krebs D, eds. Foundations of Evolutionary Psychology. Taylor & Francis Group/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008:383-400.

7. Friedman SH. Fathers and filicide: Mental illness and outcomes. In: Wong G, Parnham G, eds. Infanticide and Filicide: Foundations in Maternal Mental Health Forensics. 1st ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020:85-107.

8. West SG, Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Fathers who kill their children: an analysis of the literature. J Forensic Sci. 2009;54(2):463-468.

9. Putkonen H, Amon S, Eronen M, et al. Gender differences in filicide offense characteristics--a comprehensive register-based study of child murder in two European countries. Child Abuse Neglect. 2011;35(5):319-328.

10. Miller LJ. Denial of pregnancy. In: Spinelli MG, ed. Infanticide: Psychosocial and Legal Perspectives on Mothers Who Kill. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2003:81-104.

11. Friedman SH, Heneghan A, Rosenthal M. Characteristics of women who deny or conceal pregnancy. Psychosomatics. 2007;48(2):117-122.

12. Beyer K, Mack SM, Shelton JL. Investigative analysis of neonaticide: an exploratory study. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2008;35(4):522-535.

13. Putkonen H, Weizmann-Henelius G, Collander J, et al. Neonaticides may be more preventable and heterogeneous than previously thought--neonaticides in Finland 1980-2000. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10(1):15-23.

14. Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Child murder and mental illness in parents: implications for psychiatrists. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(5):587-588.

15. Resnick PJ. Child murder by parents: a psychiatric review of filicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1969;126(3):325-334.

16. Friedman SH. Searching for the whole truth: considering culture and gender in forensic psychiatric practice. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2023;51(1):23-34.

17. Friedman SH, Hrouda DR, Holden CE, et al. Child murder committed by severely mentally ill mothers: an examination of mothers found not guilty by reason of insanity. J Forensic Sci. 2005;50(6):1466-1471.

18. Ash P. Fatal maltreatment and child abuse turned to murder. In: Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. Group for the Advancement Psychiatry; 2018.

19. Friedman SH, Appel JM. Murder in the family: intimate partner homicide in the elderly. Psychiatric News. 2018. Accessed April 8, 2023. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2018.12a21

20. Friedman SH, McEwan MV. Treated mental illness and the risk of child abuse perpetration. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(2):211-216.

21. McEwan M, Friedman SH. Violence by parents against their children: reporting of maltreatment suspicions, child protection, and risk in mental illness. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(4):691-700.

22. Hatters Friedman S, Beaman JW, Friedman JB. Fatality review and the role of the forensic psychiatrist. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2021;49(3):396-405.

23. Friedman SH, Prakash C, Nagle-Yang S. Postpartum psychosis: protecting mother and infant. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(4):12-21.

24. Stanton J, Simpson AI, Wouldes T. A qualitative study of filicide by mentally ill mothers. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24(11):1451-1460.

25. Levitzky S, Cooper R. Infant colic syndrome—maternal fantasies of aggression and infanticide. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2000;39(7):395-400.

26. Jennings KD, Ross S, Popper S, et al. Thoughts of harming infants in depressed and nondepressed mothers. J Affect Disord. 1999;54(1-2):21-28.

27. Barr JA, Beck CT. Infanticide secrets: qualitative study on postpartum depression. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(12):1716-1717.e5.

28. Friedman SH, Sorrentino RM, Stankowski JE, et al. Psychiatrists’ knowledge about maternal filicidal thoughts. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49(1):106-110.

29. Booth BD, Friedman SH, Curry S, et al. Obsessions of child murder: underrecognized manifestations of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2014;42(1):66-74.

30. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Avoiding malpractice while treating depression in pregnant women. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):30-36.

Deaths of children who are killed by their parents often make the news. Cases of maternal infanticide may be particularly shocking, since women are expected to be selfless nurturers. Yet when a child is murdered, the most common perpetrator is their parent, and mothers and fathers kill at similar rates.1

As psychiatrists, we may see these cases in the news and worry about the risks of our own patients killing their children. In approximately 500 cases annually, an American parent is arrested for the homicide of their child.2 This is not even the entire story, since a large percentage of such cases end in suicide—and no arrest. This article reviews the reasons parents kill their children, and considers common characteristics of these parents, dispelling some myths, before discussing the importance of prevention efforts.

Types of child murder by parents

Child murder by parents is termed filicide. Infanticide has various meanings but often refers to the murder of a child younger than age 1. Approximately 2 dozen nations (but not the United States) have Infanticide Acts that decrease the penalty for mothers who kill their young child.3 Neonaticide refers to murder of the infant at birth or in the first day of life.4

Epidemiology and common characteristics

Approximately 15%—or 1 in 7 murders with an arrest—is a filicide.2 The younger the child, the greater the risk, but older children are killed as well.2 Internationally, fathers and mothers are found to kill at similar rates. For other types of homicide, offenders are overwhelmingly male. This makes child murder by parents the singular type of murder in which women and men perpetrate in equal numbers. Fathers are more likely than mothers to also commit suicide after they kill their children.5 The “Cinderella effect” refers to the elevated risk of a stepchild being killed compared to the risk for a biological child.6

In the general international population, mothers who commit filicide tend to have multiple stressors and limited resources. They may be socially isolated and may be victims themselves as well as potentially experiencing substance abuse.1 Some mothers view the child they killed as abnormal.

Less research has been conducted about fathers who kill. Fathers are more likely to also commit partner homicide.5,7 They are more likely to complete filicide-suicide and use firearms or other violent means.5,7-9 Fathers may have a history of violence, substance abuse, and/or mental illness.7

Neonaticide

Mothers are the most common perpetrator of neonaticide.4 It is unusual for a father to be involved in a neonaticide, or for the father and mother to perpetrate the act together. Rates of neonaticide are considered underestimates because of the number of hidden pregnancies, hidden corpses, and the difficulty that forensic pathologists may have in determining whether a baby was born alive or dead.

Continue to: Perpetrators of neonaticide...

Perpetrators of neonaticide tend to be single, relatively young women acting alone. They often live with their parents and are fearful of the repercussions of being pregnant. Pregnancies are often hidden, with no prenatal care. This includes both denial and concealment of pregnancy.4 Perpetrators of neonaticide commonly lack a premorbid serious mental illness, though after the homicide they may develop anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or adjustment disorder.4 (Individuals who unwittingly find a murdered baby’s corpse may also be at risk of PTSD.)

Hidden pregnancies may be due to concealment or denial of pregnancy.10,11 Concealment of pregnancy involves a woman knowing she is pregnant, but purposely hiding from others. Concealment may occur after a period of denial of pregnancy. Denial of pregnancy has several subtypes: pervasive denial, affective denial, and psychotic denial. In cases of pervasive denial, the existence of the pregnancy and the pregnancy’s emotional significance is outside the woman’s awareness. Alternatively, in affective denial, she is intellectually aware that she is pregnant but makes little emotional or physical preparation. In the rarest form, psychotic denial, a woman with a psychotic disorder such as schizophrenia may intermittently deny her pregnancy. This may be correlated with a history of custody loss.10,11 Unlike denial of other medical conditions, in cases of denial of pregnancy, there will exist a very specific point in time (delivery) when the reality of the baby confronts the woman. Risks in cases of hidden pregnancies include those from lack of prenatal care and an assisted delivery as well as neonaticide. An FBI study12 of law enforcement files found most neonaticide offenders were single young women with no criminal or psychological history. A caveat is that in the rare cases in which a woman with psychotic illness commits neonaticide, she may have different characteristics from those generally reported.13

Motives

Fathers and mothers have a similar set of motives for killing their child (Table 113-15). Motives are critical to understand not only within forensics, but also for prevention. In performing assessments after a filicide, forensic psychiatrists must be mindful of gender bias.7,16 Resnick15 initially described 5 motives based on his 1969 review of the world literature. Our work5,17 has subsequently further explored these motives.

In child homicides from “fatal maltreatment,” the child has often been a chronic victim of abuse or neglect. National American data indicate that approximately 2 per 100,000 children are killed from child maltreatment annually. Of note in conceptualizing prevention, out of the same population of 100,000, there will be 471 referrals to Child Protective Services and 91 substantiated cases.18 However, only a minority of children who die from maltreatment had previous Child Protective Services involvement. While a child may be killed by fatal maltreatment at any age, one-half are younger than age 1, and three-quarters are younger than age 3.18 In rare cases, a parent who engages in medical child abuse (including factitious disorder imposed upon another) kills the child. Depending on the location and whether or not the death appeared to be intended, parents who kill because of fatal maltreatment might face charges of various levels of murder or manslaughter.

“Unwanted child” homicides occur when the parent has determined that they do not want to have the child, especially in comparison to another need or want. Unwanted child motive is the most common in neonaticide cases, occurring after a hidden pregnancy.4

Continue to: In "partner revenge" cases...

In “partner revenge” cases, parenting disputes, a custody battle, infidelity, or a difficult relationship breakup is often present. The parent wants to make the other parent suffer, and does so by killing their child. A parent may make statements such as “If I can’t have [the child], no one can,” and the child is used as a pawn.

In the final 2 motives—“altruistic” and “acutely psychotic”—mental illness is common. These are the populations we tend to find in samples of filicide-suicide cases where the parent has killed themselves and their child, and those found not guilty by reason of insanity.5,17 Altruistic filicide has been described as “murder out of love.” How can a parent kill their child out of love? Our research has shown several ways. First, the parent may be severely depressed and suicidal. They may be planning their own suicide, and as a parent who loves their child, they plan to take their child with them in death and not leave them alone in the “cruel world” that they themselves are departing. Or the parent may believe they are killing the child out of love to prevent or relieve the child’s suffering. The psychotic parent may believe that a terrible fate will befall their child, and they are killing them “gently.” For example, the parent may believe the child will be tortured or sex trafficked. Some parents may believe that their child has a devastating disease and think they would be better off dead. (Similar thinking of misguided altruism is seen in some cases of intimate partner homicide among older adults.19)

Alternatively, in rare cases of acutely psychotic filicide, parents with psychosis kill their child with no comprehensible motive. For example, they may be in a postictal state or may hear a command hallucination from God in the context of their psychosis.15

Myths vs realities of filicide

Common myths vs the realities of filicide are noted in Table 2. There are issues with believing these myths. For example, if we believe that most parents who kill their child have mental illness, this conflates mental illness and child homicide in our minds as well as the mind of the public. This can lead to further stigmatization of mental illness, and a lack of help-seeking behaviors because parents experiencing psychiatric symptoms may be afraid that if they report their symptoms, their child will be removed by Child Protective Services. However, treated mental illness decreases the risks of child abuse, similar to how treating mental illness decreases risks of other types of violence.20,21

Focusing on prevention

On a local level, we need to understand these tragedies to better understand prevention. To this end, across the United States, counties have Child Fatality Review teams.22 These teams are a partnership across sectors and disciplines, including professionals from health services, law enforcement, and social services—among others—working together to understand cases and consider preventive strategies and additional services needed within our communities.

Continue to: When conceptualizing prevention...

When conceptualizing prevention of child murder by parents, we can think of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention. This means we want to encourage healthy families and healthy relationships within the family, as well as screening for risk and targeting interventions for families that have experienced difficulties, as well as for parents who have mental illness or substance use disorders.

Understanding the motive behind an individual committing filicide is also critical so that we do not conflate filicide and mental illness. Conflating these concepts leads to increased stigmatization and less help-seeking behavior.

Table 33,4,7,18,22,23 describes the importance of understanding the motives for child murder by a parent in order to conceptualize appropriate prevention. Prevention efforts for 1 type of child murder will not necessarily help prevent murders that occur due to the other motives. Regarding prevention for fatal maltreatment cases, poor parenting skills, including inappropriate expressions of discipline, anger, and frustration, are common. In some cases, substance abuse is involved or the parent was acutely mentally unwell. Reporting to Child Protective Services can be helpful, but as previously noted, it is difficult to ascertain which cases will lead to a homicide. Recommendations from Child Fatality Review teams also are valuable.

Though many parents have frustrations with their children or thoughts of child harm, the act of filicide is rare, and individual cases may be difficult to predict. Regarding prediction, some mothers who committed filicide saw their psychiatrist within days to weeks before the murders.17 A small New Zealand study found that psychotic mothers reported no plans for killing their children in advance, whereas depressed mothers had contemplated the killing for days to weeks.24

Several studies have asked mothers about thoughts of harming their child. Among mothers with colicky infants, 70% reported “explicit aggressive thoughts and fantasies” while 26% had “infanticidal thoughts” during a colic episode.25 Another study26 found that among depressed mothers of infants and toddlers, 41% revealed thoughts of harming their child. Women with postpartum depression preferred not to share infanticidal thoughts with their doctor but were more likely to disclose that they were having suicidal thoughts in order to get needed help.27 Psychiatrists need to feel comfortable asking mothers about their coping skills, their suicidal thoughts, and their filicidal thoughts.14,23,28 Screening and treatment of mental illness is critical. Postpartum psychosis is well-known to pose an elevated risk of filicide and suicide.23 Obsessive-compulsive disorder may cause a parent to ruminate over ego-dystonic child harm but should be treated and the risk conceptualized very differently than in postpartum psychosis.23,29 Screening for postpartum depression and appropriate treatment of depression during pregnancy and the postpartum period decrease risk.30

Continue to: Regarding prevention of neonaticide...

Regarding prevention of neonaticide, Safe Haven laws, baby boxes, anonymous birth options, and increased contraceptive information and availability can help decrease the risk of this well-defined type of homicide.4 Safe Haven laws originated from Child Fatality Review teams.24 Though each state has its own variation, in general, parents can drop off an unharmed unwanted infant into Safe Havens in their state, which may include hospitals, police stations, or fire stations. In general, the mother remains anonymous and has immunity from prosecution for (safe) abandonment. There are drawbacks, such as lack of information regarding adoption and paternal rights. Safe Haven laws do not prevent all deaths and all unsafe abandonments. Baby boxes and baby hatches are used in various nations, including in Europe, and in some places have been used for centuries. In anonymous birth options, such as in France, a mother is not identified but is able to give birth at a hospital. This can decrease the risk from unattended delivery, but many women with denial of pregnancy report that they did not realize when they were about to give birth.4

Bottom Line

Knowledge about the intersection of mental illness and filicide can help in prevention. Parents who experience mental health concerns should be encouraged to obtain needed treatment, which aids prevention. However, many other factors elevate the risk of child murder by parents.

Related Resources

- National Center for Fatality Review and Prevention. https://ncfrp.org/

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/preventing/overview/federal-agencies/

Deaths of children who are killed by their parents often make the news. Cases of maternal infanticide may be particularly shocking, since women are expected to be selfless nurturers. Yet when a child is murdered, the most common perpetrator is their parent, and mothers and fathers kill at similar rates.1

As psychiatrists, we may see these cases in the news and worry about the risks of our own patients killing their children. In approximately 500 cases annually, an American parent is arrested for the homicide of their child.2 This is not even the entire story, since a large percentage of such cases end in suicide—and no arrest. This article reviews the reasons parents kill their children, and considers common characteristics of these parents, dispelling some myths, before discussing the importance of prevention efforts.

Types of child murder by parents

Child murder by parents is termed filicide. Infanticide has various meanings but often refers to the murder of a child younger than age 1. Approximately 2 dozen nations (but not the United States) have Infanticide Acts that decrease the penalty for mothers who kill their young child.3 Neonaticide refers to murder of the infant at birth or in the first day of life.4

Epidemiology and common characteristics

Approximately 15%—or 1 in 7 murders with an arrest—is a filicide.2 The younger the child, the greater the risk, but older children are killed as well.2 Internationally, fathers and mothers are found to kill at similar rates. For other types of homicide, offenders are overwhelmingly male. This makes child murder by parents the singular type of murder in which women and men perpetrate in equal numbers. Fathers are more likely than mothers to also commit suicide after they kill their children.5 The “Cinderella effect” refers to the elevated risk of a stepchild being killed compared to the risk for a biological child.6

In the general international population, mothers who commit filicide tend to have multiple stressors and limited resources. They may be socially isolated and may be victims themselves as well as potentially experiencing substance abuse.1 Some mothers view the child they killed as abnormal.

Less research has been conducted about fathers who kill. Fathers are more likely to also commit partner homicide.5,7 They are more likely to complete filicide-suicide and use firearms or other violent means.5,7-9 Fathers may have a history of violence, substance abuse, and/or mental illness.7

Neonaticide

Mothers are the most common perpetrator of neonaticide.4 It is unusual for a father to be involved in a neonaticide, or for the father and mother to perpetrate the act together. Rates of neonaticide are considered underestimates because of the number of hidden pregnancies, hidden corpses, and the difficulty that forensic pathologists may have in determining whether a baby was born alive or dead.

Continue to: Perpetrators of neonaticide...

Perpetrators of neonaticide tend to be single, relatively young women acting alone. They often live with their parents and are fearful of the repercussions of being pregnant. Pregnancies are often hidden, with no prenatal care. This includes both denial and concealment of pregnancy.4 Perpetrators of neonaticide commonly lack a premorbid serious mental illness, though after the homicide they may develop anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), or adjustment disorder.4 (Individuals who unwittingly find a murdered baby’s corpse may also be at risk of PTSD.)

Hidden pregnancies may be due to concealment or denial of pregnancy.10,11 Concealment of pregnancy involves a woman knowing she is pregnant, but purposely hiding from others. Concealment may occur after a period of denial of pregnancy. Denial of pregnancy has several subtypes: pervasive denial, affective denial, and psychotic denial. In cases of pervasive denial, the existence of the pregnancy and the pregnancy’s emotional significance is outside the woman’s awareness. Alternatively, in affective denial, she is intellectually aware that she is pregnant but makes little emotional or physical preparation. In the rarest form, psychotic denial, a woman with a psychotic disorder such as schizophrenia may intermittently deny her pregnancy. This may be correlated with a history of custody loss.10,11 Unlike denial of other medical conditions, in cases of denial of pregnancy, there will exist a very specific point in time (delivery) when the reality of the baby confronts the woman. Risks in cases of hidden pregnancies include those from lack of prenatal care and an assisted delivery as well as neonaticide. An FBI study12 of law enforcement files found most neonaticide offenders were single young women with no criminal or psychological history. A caveat is that in the rare cases in which a woman with psychotic illness commits neonaticide, she may have different characteristics from those generally reported.13

Motives

Fathers and mothers have a similar set of motives for killing their child (Table 113-15). Motives are critical to understand not only within forensics, but also for prevention. In performing assessments after a filicide, forensic psychiatrists must be mindful of gender bias.7,16 Resnick15 initially described 5 motives based on his 1969 review of the world literature. Our work5,17 has subsequently further explored these motives.

In child homicides from “fatal maltreatment,” the child has often been a chronic victim of abuse or neglect. National American data indicate that approximately 2 per 100,000 children are killed from child maltreatment annually. Of note in conceptualizing prevention, out of the same population of 100,000, there will be 471 referrals to Child Protective Services and 91 substantiated cases.18 However, only a minority of children who die from maltreatment had previous Child Protective Services involvement. While a child may be killed by fatal maltreatment at any age, one-half are younger than age 1, and three-quarters are younger than age 3.18 In rare cases, a parent who engages in medical child abuse (including factitious disorder imposed upon another) kills the child. Depending on the location and whether or not the death appeared to be intended, parents who kill because of fatal maltreatment might face charges of various levels of murder or manslaughter.

“Unwanted child” homicides occur when the parent has determined that they do not want to have the child, especially in comparison to another need or want. Unwanted child motive is the most common in neonaticide cases, occurring after a hidden pregnancy.4

Continue to: In "partner revenge" cases...

In “partner revenge” cases, parenting disputes, a custody battle, infidelity, or a difficult relationship breakup is often present. The parent wants to make the other parent suffer, and does so by killing their child. A parent may make statements such as “If I can’t have [the child], no one can,” and the child is used as a pawn.

In the final 2 motives—“altruistic” and “acutely psychotic”—mental illness is common. These are the populations we tend to find in samples of filicide-suicide cases where the parent has killed themselves and their child, and those found not guilty by reason of insanity.5,17 Altruistic filicide has been described as “murder out of love.” How can a parent kill their child out of love? Our research has shown several ways. First, the parent may be severely depressed and suicidal. They may be planning their own suicide, and as a parent who loves their child, they plan to take their child with them in death and not leave them alone in the “cruel world” that they themselves are departing. Or the parent may believe they are killing the child out of love to prevent or relieve the child’s suffering. The psychotic parent may believe that a terrible fate will befall their child, and they are killing them “gently.” For example, the parent may believe the child will be tortured or sex trafficked. Some parents may believe that their child has a devastating disease and think they would be better off dead. (Similar thinking of misguided altruism is seen in some cases of intimate partner homicide among older adults.19)

Alternatively, in rare cases of acutely psychotic filicide, parents with psychosis kill their child with no comprehensible motive. For example, they may be in a postictal state or may hear a command hallucination from God in the context of their psychosis.15

Myths vs realities of filicide

Common myths vs the realities of filicide are noted in Table 2. There are issues with believing these myths. For example, if we believe that most parents who kill their child have mental illness, this conflates mental illness and child homicide in our minds as well as the mind of the public. This can lead to further stigmatization of mental illness, and a lack of help-seeking behaviors because parents experiencing psychiatric symptoms may be afraid that if they report their symptoms, their child will be removed by Child Protective Services. However, treated mental illness decreases the risks of child abuse, similar to how treating mental illness decreases risks of other types of violence.20,21

Focusing on prevention

On a local level, we need to understand these tragedies to better understand prevention. To this end, across the United States, counties have Child Fatality Review teams.22 These teams are a partnership across sectors and disciplines, including professionals from health services, law enforcement, and social services—among others—working together to understand cases and consider preventive strategies and additional services needed within our communities.

Continue to: When conceptualizing prevention...

When conceptualizing prevention of child murder by parents, we can think of primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention. This means we want to encourage healthy families and healthy relationships within the family, as well as screening for risk and targeting interventions for families that have experienced difficulties, as well as for parents who have mental illness or substance use disorders.

Understanding the motive behind an individual committing filicide is also critical so that we do not conflate filicide and mental illness. Conflating these concepts leads to increased stigmatization and less help-seeking behavior.

Table 33,4,7,18,22,23 describes the importance of understanding the motives for child murder by a parent in order to conceptualize appropriate prevention. Prevention efforts for 1 type of child murder will not necessarily help prevent murders that occur due to the other motives. Regarding prevention for fatal maltreatment cases, poor parenting skills, including inappropriate expressions of discipline, anger, and frustration, are common. In some cases, substance abuse is involved or the parent was acutely mentally unwell. Reporting to Child Protective Services can be helpful, but as previously noted, it is difficult to ascertain which cases will lead to a homicide. Recommendations from Child Fatality Review teams also are valuable.

Though many parents have frustrations with their children or thoughts of child harm, the act of filicide is rare, and individual cases may be difficult to predict. Regarding prediction, some mothers who committed filicide saw their psychiatrist within days to weeks before the murders.17 A small New Zealand study found that psychotic mothers reported no plans for killing their children in advance, whereas depressed mothers had contemplated the killing for days to weeks.24

Several studies have asked mothers about thoughts of harming their child. Among mothers with colicky infants, 70% reported “explicit aggressive thoughts and fantasies” while 26% had “infanticidal thoughts” during a colic episode.25 Another study26 found that among depressed mothers of infants and toddlers, 41% revealed thoughts of harming their child. Women with postpartum depression preferred not to share infanticidal thoughts with their doctor but were more likely to disclose that they were having suicidal thoughts in order to get needed help.27 Psychiatrists need to feel comfortable asking mothers about their coping skills, their suicidal thoughts, and their filicidal thoughts.14,23,28 Screening and treatment of mental illness is critical. Postpartum psychosis is well-known to pose an elevated risk of filicide and suicide.23 Obsessive-compulsive disorder may cause a parent to ruminate over ego-dystonic child harm but should be treated and the risk conceptualized very differently than in postpartum psychosis.23,29 Screening for postpartum depression and appropriate treatment of depression during pregnancy and the postpartum period decrease risk.30

Continue to: Regarding prevention of neonaticide...

Regarding prevention of neonaticide, Safe Haven laws, baby boxes, anonymous birth options, and increased contraceptive information and availability can help decrease the risk of this well-defined type of homicide.4 Safe Haven laws originated from Child Fatality Review teams.24 Though each state has its own variation, in general, parents can drop off an unharmed unwanted infant into Safe Havens in their state, which may include hospitals, police stations, or fire stations. In general, the mother remains anonymous and has immunity from prosecution for (safe) abandonment. There are drawbacks, such as lack of information regarding adoption and paternal rights. Safe Haven laws do not prevent all deaths and all unsafe abandonments. Baby boxes and baby hatches are used in various nations, including in Europe, and in some places have been used for centuries. In anonymous birth options, such as in France, a mother is not identified but is able to give birth at a hospital. This can decrease the risk from unattended delivery, but many women with denial of pregnancy report that they did not realize when they were about to give birth.4

Bottom Line

Knowledge about the intersection of mental illness and filicide can help in prevention. Parents who experience mental health concerns should be encouraged to obtain needed treatment, which aids prevention. However, many other factors elevate the risk of child murder by parents.

Related Resources

- National Center for Fatality Review and Prevention. https://ncfrp.org/

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. https://www.childwelfare.gov/topics/preventing/overview/federal-agencies/

1. Friedman SH, Horwitz SM, Resnick PJ. Child murder by mothers: a critical analysis of the current state of knowledge and a research agenda. Am J Psych. 2005;162(9):1578-1587.

2. Mariano TY, Chan HC, Myers WC. Toward a more holistic understanding of filicide: a multidisciplinary analysis of 32 years of US arrest data [published corrections appears in Forensic Sci Int. 2014;245:92-94]. Forensic Sci Int. 2014;236:46-53.

3. Hatters Friedman S, Resnick PJ. Child murder by mothers: patterns and prevention. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):137-141.

4. Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Neonaticide: phenomenology and considerations for prevention. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2009;32(1):43-47.

5. Hatters Friedman S, Hrouda DR, Holden CE, et al. Filicide-suicide: common factors in parents who kill their children and themselves. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2005;33(4):496-504.

6. Daly M, Wilson M. Is the “Cinderella effect” controversial? A case study of evolution-minded research and critiques thereof. In: Crawford C, Krebs D, eds. Foundations of Evolutionary Psychology. Taylor & Francis Group/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008:383-400.

7. Friedman SH. Fathers and filicide: Mental illness and outcomes. In: Wong G, Parnham G, eds. Infanticide and Filicide: Foundations in Maternal Mental Health Forensics. 1st ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020:85-107.

8. West SG, Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Fathers who kill their children: an analysis of the literature. J Forensic Sci. 2009;54(2):463-468.

9. Putkonen H, Amon S, Eronen M, et al. Gender differences in filicide offense characteristics--a comprehensive register-based study of child murder in two European countries. Child Abuse Neglect. 2011;35(5):319-328.

10. Miller LJ. Denial of pregnancy. In: Spinelli MG, ed. Infanticide: Psychosocial and Legal Perspectives on Mothers Who Kill. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2003:81-104.

11. Friedman SH, Heneghan A, Rosenthal M. Characteristics of women who deny or conceal pregnancy. Psychosomatics. 2007;48(2):117-122.

12. Beyer K, Mack SM, Shelton JL. Investigative analysis of neonaticide: an exploratory study. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2008;35(4):522-535.

13. Putkonen H, Weizmann-Henelius G, Collander J, et al. Neonaticides may be more preventable and heterogeneous than previously thought--neonaticides in Finland 1980-2000. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10(1):15-23.

14. Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Child murder and mental illness in parents: implications for psychiatrists. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(5):587-588.

15. Resnick PJ. Child murder by parents: a psychiatric review of filicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1969;126(3):325-334.

16. Friedman SH. Searching for the whole truth: considering culture and gender in forensic psychiatric practice. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2023;51(1):23-34.

17. Friedman SH, Hrouda DR, Holden CE, et al. Child murder committed by severely mentally ill mothers: an examination of mothers found not guilty by reason of insanity. J Forensic Sci. 2005;50(6):1466-1471.

18. Ash P. Fatal maltreatment and child abuse turned to murder. In: Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. Group for the Advancement Psychiatry; 2018.

19. Friedman SH, Appel JM. Murder in the family: intimate partner homicide in the elderly. Psychiatric News. 2018. Accessed April 8, 2023. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2018.12a21

20. Friedman SH, McEwan MV. Treated mental illness and the risk of child abuse perpetration. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(2):211-216.

21. McEwan M, Friedman SH. Violence by parents against their children: reporting of maltreatment suspicions, child protection, and risk in mental illness. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(4):691-700.

22. Hatters Friedman S, Beaman JW, Friedman JB. Fatality review and the role of the forensic psychiatrist. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2021;49(3):396-405.

23. Friedman SH, Prakash C, Nagle-Yang S. Postpartum psychosis: protecting mother and infant. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(4):12-21.

24. Stanton J, Simpson AI, Wouldes T. A qualitative study of filicide by mentally ill mothers. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24(11):1451-1460.

25. Levitzky S, Cooper R. Infant colic syndrome—maternal fantasies of aggression and infanticide. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2000;39(7):395-400.

26. Jennings KD, Ross S, Popper S, et al. Thoughts of harming infants in depressed and nondepressed mothers. J Affect Disord. 1999;54(1-2):21-28.

27. Barr JA, Beck CT. Infanticide secrets: qualitative study on postpartum depression. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(12):1716-1717.e5.

28. Friedman SH, Sorrentino RM, Stankowski JE, et al. Psychiatrists’ knowledge about maternal filicidal thoughts. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49(1):106-110.

29. Booth BD, Friedman SH, Curry S, et al. Obsessions of child murder: underrecognized manifestations of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2014;42(1):66-74.

30. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Avoiding malpractice while treating depression in pregnant women. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):30-36.

1. Friedman SH, Horwitz SM, Resnick PJ. Child murder by mothers: a critical analysis of the current state of knowledge and a research agenda. Am J Psych. 2005;162(9):1578-1587.

2. Mariano TY, Chan HC, Myers WC. Toward a more holistic understanding of filicide: a multidisciplinary analysis of 32 years of US arrest data [published corrections appears in Forensic Sci Int. 2014;245:92-94]. Forensic Sci Int. 2014;236:46-53.

3. Hatters Friedman S, Resnick PJ. Child murder by mothers: patterns and prevention. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):137-141.

4. Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Neonaticide: phenomenology and considerations for prevention. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2009;32(1):43-47.

5. Hatters Friedman S, Hrouda DR, Holden CE, et al. Filicide-suicide: common factors in parents who kill their children and themselves. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2005;33(4):496-504.

6. Daly M, Wilson M. Is the “Cinderella effect” controversial? A case study of evolution-minded research and critiques thereof. In: Crawford C, Krebs D, eds. Foundations of Evolutionary Psychology. Taylor & Francis Group/Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 2008:383-400.

7. Friedman SH. Fathers and filicide: Mental illness and outcomes. In: Wong G, Parnham G, eds. Infanticide and Filicide: Foundations in Maternal Mental Health Forensics. 1st ed. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2020:85-107.

8. West SG, Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Fathers who kill their children: an analysis of the literature. J Forensic Sci. 2009;54(2):463-468.

9. Putkonen H, Amon S, Eronen M, et al. Gender differences in filicide offense characteristics--a comprehensive register-based study of child murder in two European countries. Child Abuse Neglect. 2011;35(5):319-328.

10. Miller LJ. Denial of pregnancy. In: Spinelli MG, ed. Infanticide: Psychosocial and Legal Perspectives on Mothers Who Kill. American Psychiatric Association Publishing; 2003:81-104.

11. Friedman SH, Heneghan A, Rosenthal M. Characteristics of women who deny or conceal pregnancy. Psychosomatics. 2007;48(2):117-122.

12. Beyer K, Mack SM, Shelton JL. Investigative analysis of neonaticide: an exploratory study. Criminal Justice and Behavior. 2008;35(4):522-535.

13. Putkonen H, Weizmann-Henelius G, Collander J, et al. Neonaticides may be more preventable and heterogeneous than previously thought--neonaticides in Finland 1980-2000. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2007;10(1):15-23.

14. Friedman SH, Resnick PJ. Child murder and mental illness in parents: implications for psychiatrists. J Clin Psychiatry. 2011;72(5):587-588.

15. Resnick PJ. Child murder by parents: a psychiatric review of filicide. Am J Psychiatry. 1969;126(3):325-334.

16. Friedman SH. Searching for the whole truth: considering culture and gender in forensic psychiatric practice. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2023;51(1):23-34.

17. Friedman SH, Hrouda DR, Holden CE, et al. Child murder committed by severely mentally ill mothers: an examination of mothers found not guilty by reason of insanity. J Forensic Sci. 2005;50(6):1466-1471.

18. Ash P. Fatal maltreatment and child abuse turned to murder. In: Friedman SH, ed. Family Murder: Pathologies of Love and Hate. Group for the Advancement Psychiatry; 2018.

19. Friedman SH, Appel JM. Murder in the family: intimate partner homicide in the elderly. Psychiatric News. 2018. Accessed April 8, 2023. https://psychnews.psychiatryonline.org/doi/10.1176/appi.pn.2018.12a21

20. Friedman SH, McEwan MV. Treated mental illness and the risk of child abuse perpetration. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(2):211-216.

21. McEwan M, Friedman SH. Violence by parents against their children: reporting of maltreatment suspicions, child protection, and risk in mental illness. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2016;39(4):691-700.

22. Hatters Friedman S, Beaman JW, Friedman JB. Fatality review and the role of the forensic psychiatrist. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2021;49(3):396-405.

23. Friedman SH, Prakash C, Nagle-Yang S. Postpartum psychosis: protecting mother and infant. Current Psychiatry. 2019;18(4):12-21.

24. Stanton J, Simpson AI, Wouldes T. A qualitative study of filicide by mentally ill mothers. Child Abuse Negl. 2000;24(11):1451-1460.

25. Levitzky S, Cooper R. Infant colic syndrome—maternal fantasies of aggression and infanticide. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2000;39(7):395-400.

26. Jennings KD, Ross S, Popper S, et al. Thoughts of harming infants in depressed and nondepressed mothers. J Affect Disord. 1999;54(1-2):21-28.

27. Barr JA, Beck CT. Infanticide secrets: qualitative study on postpartum depression. Can Fam Physician. 2008;54(12):1716-1717.e5.

28. Friedman SH, Sorrentino RM, Stankowski JE, et al. Psychiatrists’ knowledge about maternal filicidal thoughts. Compr Psychiatry. 2008;49(1):106-110.

29. Booth BD, Friedman SH, Curry S, et al. Obsessions of child murder: underrecognized manifestations of obsessive-compulsive disorder. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2014;42(1):66-74.

30. Friedman SH, Hall RCW. Avoiding malpractice while treating depression in pregnant women. Current Psychiatry. 2021;20(8):30-36.